Ohio History Journal

|

|

|

Ohio Quakers and the Mississippi Freedmen -- "A Field to Labor" by Thomas H. Smith |

|

During the American Civil War the Ohio Yearly Meeting of the Society of Friends (Orthodox) was one of several religious sects that found use of warfare to maintain national unity repugnant. The Friends, however, were not callous to the many sacrifices their neighbors had made, and they did not remain idle during time of national crisis. Instead of responding to the nation's martial needs, this small group applied its energy and financial resources to the education and rehabilitation of free black Ameri- cans. Their objectives were to prepare the former slaves for freedom and, at the same time, to make them useful and independent citizens within white society. It was in the area of Freedmen education and welfare that the Ohio Yearly Meeting found "a field . . . opened in which we are loudly called to labor."1 That the Ohio Friends were interested in the condition of the American Negro during and after the war was only natural since they had been long identified with those forces in the North that were dedicated to the abolition of slavery. For example, Benjamin Lundy, as early as 1815, had organized Ohio's Union Humane Society in St. Clairsville, and two years later Charles Osborn founded the antislavery newspaper, The Philanthro- pist, at Mt. Pleasant. Many Ohio Quakers had been active in assisting fugi- tive slaves on their trek across the state to freedom in Canada. On several occasions between 1825 and the outbreak of the war in 1861, Quakers had received small groups of manumitted slaves from the South and had provided for their settlement near their own communities.2 For these NOTES ON PAGE 221 |

160 OHIO HISTORY

persons and others already living in

Ohio, the Friends assisted in the

management of farms, provided for

educational and religious instruction,

distributed Bibles, furnished meeting

houses, and provided for the Negroes'

general well being. In fact, by 1859,

the Ohio Yearly Meeting was so

involved with the Negro that it created

a committee on the Concerns

of the People of Color and made it part

of its permanent organization.

Thus, by the eve of the Civil War the

Ohio Quakers had clearly committed

themselves to the welfare of Freedmen,

and although reports about these

Negroes were not always encouraging, the

Quakers observed that the

former slaves were "as susceptible

to improvement as any other class."3

Until 1863 efforts of Ohio Quakers on

behalf of the Freedmen had been

confined within the state, but after the

announcement of the Emancipa-

tion Proclamation, the Ohio Yearly

Meeting addressed itself to conditions

of Freedmen outside the state. This

outpouring of concern for the welfare

of the black "refugees" in the

South was not unique to tile Ohio Quakers,

but was part of a general movement of

the various Quaker yearly meetings

throughout the North, Mindful of their

refusal to aid the military, the

Quakers were willing to assist their

country during a period of national

strife by means consistent with their

beliefs.

Between 1863 and 1865 there was an

almost frantic effort on the part

of Ohio ers to relieve the physical

needs of the southern Negro. In

1863 several of the quarterly meetings

within the Ohio Yearly Meeting

contributed about $6000 in addition to

new and used clothing "for the

benefit of tile refugees from

slavery"4 to the Western Freedmen's Aid Com-

mission founded by the Western Yearly

Meeting that same year. This

commission was one of several such

agencies formed by northern Quakers

to aid suffering Freedmen in the South.

The following year the Ohioans

raised $6709.42 for tile relief of

Negroes and appointed a special committee

to coordinate its own efforts with those

of the Indiana, and Western and

Iowa yearly meetings.5 During

1864 and 1865 the Ohio special committee

spent much of its time collecting money

for direct relief work. It also

recommended to tile Yearly Meeting that

$10,000 should be raised through

voluntary subscriptions to aid "the sufferings of

these perishing people" and

suggested that twenty or more teachers

should be sent South to educate

the former slaves.6 In order to raise

this rather large sum of money, the

committee for the relief of Freedmen

sent circulars to each quarterly

and monthly meeting "encouraging

promptness and liberality in contribut-

ing to this benevolent cause."7

The argument was that,

The long oppressed and suffering

millions of tile South are loudly

calling on the friends of humanity for

help; . . . and upon the action

of the friends of justice and humanity

at this momentous period,

depends much of good or evil, not only

to this class, but to our country

and to the world. Then let us open

widely our hearts and purses, in

this dark hour of their trial; that in

the great day of final accounts, the

language may not be applied to us,

"Inasmuch as ye did not to one

of the least of these, ye did it not to

me."8

QUAKERS AND FREEDMEN

161

Apparently these appeals to the Quakers

were successful because most

of the $10,000 was collected. This

generous giving, however, marked the

high point for the Ohioan's direct

relief program. This type of relief

was understood to be a temporary

measure, and other more permanent

solutions were sought to improve the lot

of the southern blacks in the

post-Civil War years. The members were

told,

We wish to say for the encouragement to

those who contributed

to this benevolent cause, that, we

believe the experiment has fully

demonstrated that the quickest and

shortest way to relieve ourselves

of the burden of contributing to the

relief of this class, and the only

way to elevate them above the depressing

effects of the deeprooted

prejudice with which they are

surrounded, and enable them to enjoy

the full blessings of freedom is, after

relieving their pressing physical

wants, to educate.9

The Ohio Quakers were no doubt

influenced in their decision to turn

their energies toward the education of

the Negro during the winter of

1864-65 by the visit of their agent

Elder John Butler to various refugee

camps and Freedmen schools along the

Mississippi River. These facilities

had been established by the Indiana

Yearly Meeting under the leadership

of Levi Coffin. Since the Quakers

believed that the Federal Government

also had a definite responsibility for

caring for southern Freedmen, Butler

visited Washington to solicit Federal

aid. President Lincoln granted the

Ohioan an interview and expressed

"his thankfulness for what Friends

had done and were doing for the relief

of colored Freedmen."10 Butler

was successful in securing government

support for transportation for his

southern tour.

In November 1864, Butler and Elkanah

Beard, the agent for the Indiana

Yearly Meeting, together examined the

conditions and needs of Freedmen

in Mississippi. Beard, who was already

familiar with the situation in the

state suggested the Ohio Yearly Meeting

should establish a Freedmen's

school on Paw Paw Island, located near

Vicksburg, where there were ap-

proximately 550 destitute Negroes.

Perhaps because of the lateness of the

year or the unsettled political

condition in the state, the Ohio Quakers

were not interested in Mississippi at

that time but, instead, hired two

teachers to work in an Indiana Quaker

Freedmen's school in Nashville,

Tennessee.11

When Butler returned to Ohio on December

5, 1864, he was enthusiastic

about the Indiana Quakers' educational

activity among the southern blacks

and heartened by the progress of the

Negroes themselves. He reported to

the Ohio Yearly Meeting that the

Negroes' "desire to learn to read and

write is so great, and their whole mind

is so absorbed in it, that their

improvement in some instances has very

been [sic] remarkable."12 Butler

then suggested that "the moral and

intellectual mental culture and instruc-

tion in the general concerns of life,

would confer a more lasting benefit

upon these people, than merely relieving

their physical wants."13 Hence,

by the end of 1865, the Ohio Quakers

were convinced by both the apparent

162 OHIO HISTORY

success of the Indiana Yearly Meeting's

educational work in Tennessee

and Butler's report that they too should

become active in Freedmen educa-

tion, and they began looking for a

suitable location for a school.

Following their annual meeting in

September 1865, the Ohioans sent

their agent William Daniels to Tennessee

where Indiana Quakers already

had an interest. There, Daniels was

encouraged to begin work by the

Freedmen's Bureau which had been

established by the Federal Government

in March to care for former slaves.

However, due to such factors as com-

petition from other religious sects, a

widely scattered Negro population,

and hostilities of the whites toward any

kind of education for their former

slaves, Ohio's effort to found a

Freedmen's school in Tennessee was can-

celled. Still eager to be of service,

however, and with promise of aid from

the Freedmen's Bureau, the Ohio Quakers

hurried to Jackson, Mississippi,

in October when they heard of the need

for a school there. Reportedly,

there was "a good field for

Teachers and a disposition on the part of the

Freedmen to support the same themselves."14

The Friends at first encountered

resistance to their schools in Jackson

from

the local white population.15 It seems that, among other

things,

the southerners objected to the rather

large number of women included

in the group of immigrant teachers and

all sorts of fanciful stories were

circulated about Yankee schoolmarms. As

a matter of fact, of the five

Ohioans who opened the school in

Jackson, four were females. Just before

their arrival, a public meeting was held

to discuss the problem of female

teachers working with Negroes. It was

reported to the Freedmen's Bureau

that one speaker stated, "of 70

female teachers sent to Gen'l [Rufus]

Saxton's Dept., over 60 had illegitimate

colored children."16 It appears

that these accounts were mostly

fabrications, but, due to the suspicious

character of the local white population,

the Ohio teachers could not find

adequate housing, and the ladies were

forced to live together in one

room.

Even though the Friends encountered

opposition, some progress in their

work was reported. While the Quakers

waited for three small school build-

ings to be constructed on public land

provided by the Freedmen's Bureau,

the teachers conducted classes in a

nearby Negro church because no other

space was made available to them.

Elizabeth Bond, a teacher sent to assist

the Ohioans from the Indiana Yearly

Meeting, complained in a letter

that "nothing would induce them

[the southern whites] to give a room

which would be used for the Freedmen in

any way; so three of us are

teaching in the same room."17 Miss

Bond's letter indicated to the editor

of the Freedmen's Record that the

white people were determined "the

negro shall not be educated to work for

himself, but must at all events

be kept a degraded being, ready when the

time comes to be again converted

into a chattel. It is very

evident," the editor continued, "that they have

no idea of giving up slavery there, and

are only waiting for the Freedmen's

Bureau to be withdrawn, to openly

ensalve the negro population." But

Miss Bond reported that through the

efforts of the Quakers "the colored

QUAKERS AND FREEDMEN

163

people have raised money and bought

lumber to put up school houses"

for themselves.18 Also, John

H. Douglas, an agent for the Indiana Quakers

who toured Mississippi during the latter

part of 1865, stated that the

Ohio Quakers were "persevering

through obloquy and insult, but the

schools are in a flourishing

condition."19

That the southern Negro would be

educated eventually was one of the

consequences of the war; yet immediately

following the conflict, most

southern state legislatures had made no

provision for the education for

their former slaves, and this

responsibility thus fell upon northern philan-

thropy and the Negroes themselves. On

October 24, 1864, the Vicksburg

Herald explained to all northern teachers in the state,

whether they were

Congregationalists, Methodists,

Presbyterians, Baptists, or Quakers, the

former Confederate state was much too

poor to offer any aid.

It is well to speak plain--in the

present impoverished condition of

the country, the education of their own

children will doubtless draw

heavily on the resources of the

citizens. If any radical was ever black

enough in his views, to suppose the

people of Mississippi would endow

"negro schools," for their ilk

to teach the rising ebo-skin hatred of

his former master, but best friend; then

such chaps had better take

to marching on with John Brown's

soul--they will hardly reach the

object of their desires short of the

locality where John is kicking and

wailing. The State has not opened them,

nor has she the slightest idea

of doing anything of the kind. While the

adult blacks are leading

their present idle and unprofitable

life, shirking all regular employ-

ment, foraging on the outskirts of our

towns and cities, paying no taxes,

refusing to labor, in many instances,

for fair wages, to expect that the

whites should educate their children is

very cool and refreshing. The

sooner the free negro is taught that he

is to support himself and his

family, precisely as the white man does,

the better it will be for him

and his descendants. The white man will

not support him in idleness,

nor tax themselves for his benefit.20

Although it is certain that the white

citizens of Jackson distrusted what

they considered the radicalism of

northern teachers, the Friends were not

radical either in their approach or

objectives. The Quakers were con-

cerned with the conditions of the

southern Negroes to be sure, but theirs

was a Christian, not a political

concern. Because they were fellow human

beings, the Friends wanted to see the

lot of the Negroes improved, and

they believed that education would help

obtain this objective. Their ap-

proach was simplistic and closely

associated with their beliefs. Primarily,

education of the Freedmen was not to be

a burden on white society.

Whether in Ohio or in the South, former

slaves were encouraged to assume

the financial responsibility for their

education and livelihood. Second, the

curriculum established was one that

would free the Negroes from reliance

upon their former masters. Elementary

subjects along with some simple

manual skills were taught in order to

make the Freedmen self-sufficient

and thrifty. Third, Ohio Friends

employed the Lancastrian or monotorial

system which allowed more capable, older

black students to instruct younger

164 OHIO HISTORY

ones. This method permitted Quakers to

train Negro teachers quickly

and economically. Eventually, it was

hoped, enough Negro teachers would

be available for the former slaves to

assume the main responsibility of

educating their own people. Fourth, in

order to ensure the Freedmen the

opportunity to learn, Quakers encouraged

the teaching of their own

"guarded religious, and literary

education." This meant that they wanted

to shield the student from harmful

influences of wrong teaching and

textbooks while providing him with an

environment in which he could

learn. Consequently, it was the opinion

of the Ohio Yearly Meeting that

the southern black could best be helped

toward useful citizenship through

"counsel and encouragement . . .

and assistance in obtaining an educa-

tion," but that they must "by

their own efforts, aid and elevate them-

selves, . . . [rather than depend upon]

direct pecuniary relief; however

desirable this may be at

times."21

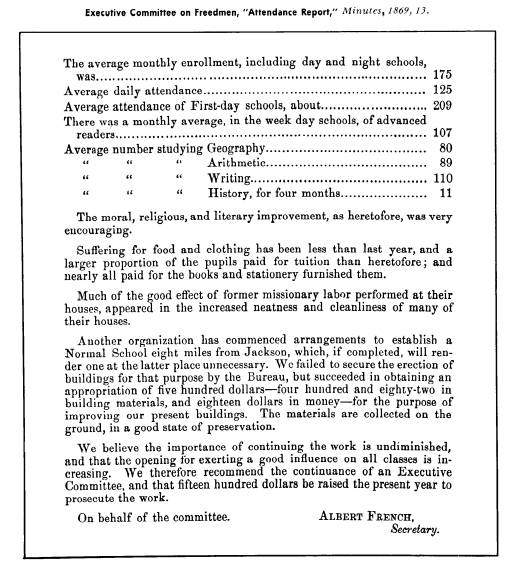

The school that was founded by the Ohio

Quakers in Jackson had both

a "School of Literary

Instruction" and an "Industrial School." Tile former

was concerned with teaching such

subjects as the alphabet, reading, geog-

raphy, arithmetic, and writing. The

report to the Educational Division

of the Freedmen's Bureau for November

1865 indicated that the literary

school had 134 students, of which forty

were pure African and the re-

mainder were of mixed blood. Also, of

the total, four were under six years

of age, eighty-eight between six and

sixteen, and forty-two over sixteen.22

The Negroes seemed responsive to

education,23 and, according to a report

sent to the 1866 Ohio Yearly Meeting,

"those who attend school seem

willing so far as able, to defray

expenses";24 that year the school collected

$629 for tuition and books from the

Freedmen.25

The industrial school taught women the

art of garment making, and

the sale of these clothing items helped

defray school expenses and provided

a small wage for the students. The

purpose of the wage was to give the

Negro practice in management of money as

well as to show whites that

former slaves could become financially responsible.

During 1866 the school

was open four months and enrolled an

average of forty-eight women daily.

These women worked approximately six

hours each day during the period

making 1267 garments and other articles.26

The industrial school, how-

ever, was short-lived. Apparently the

physical needs of the southern Freed-

men had lessened somewhat by 1867

because that year, after only thirty-

six days of operation, it was closed. At

about the same time, the Joint

Board of Relief, which had been formed

by the Ohio, Indiana, and

Western and Iowa yearly meetings in

1864, was dissolved because "the

circumstances [for its continuance were]

no longer existing."27 Thus, after

1867, the Ohio Friends concentrated more

of their energies on the

academic needs of Freedmen.

The Quakers labored hard among the

Freedmen in Jackson, and their

approach to the education of Negroes

soon calmed many fears the southern

white community had had about their

coming. Even though the Ohioans

had suffered some harrassment from the

white population, the Quakers

|

QUAKERS AND FREEDMEN 165 |

|

166 OHIO HISTORY |

|

soon reported that "the citizens . . . seem to be more kindly disposed," than they were before. "The meekness, patience and forbearance of the teachers seems to have had a favorable effect." The report continued, "and as citizens of Jackson remarked, the instruction given to the Freedmen, instead of making them saucy and indolent, has had a beneficial effect upon them, having a tendency to make them kind and obedient."28 Thomas Smith, ex-chaplain of the Fifty-Third United States Colored Troops and an official of the Freedmen's Bureau, expressed his thanks to the Ohio Yearly Meeting in the spring of 1866 for its work "in forming the intel- lectual, moral and religious character of the Freedmen." Smith, who point- ed out that the Friends had pioneered Negro education in Jackson, also said the Ohio teachers were "peaceable, unobtrusive and indefatigable" and that the school had "accomplished an invaluable amount of good."29 Yet, the Quakers realized more than did government officials the obstacles that lay ahead for the improvement of the general conditions of the southern Negroes. They confessed that while their work was one of "Christian love and self-sacrifice," its success was "not the work of a day, or a year, but many years."30 During the summer of 1866 the Quakers had to remove their school buildings from the public lands upon which the Freedmen's Bureau had helped them to settle, but the Ohio Yearly Meeting was able to purchase six town lots for their school.31 To fulfill the philosophy that the Freedmen should support their own education, a contract was drawn up between |

|

QUAKERS AND FREEDMEN 167 the Quakers and the Negroes which stated that when the Freedmen paid for the lots and houses and showed "sufficient ability to conduct their own schools, they are to own and have possession of the buildings and the lots on which they stand."32 The Quakers were still optimistic about their work with the Freedmen and reported that educational progress of the Negroes in Jackson was equal to that of white students in the North and that they were "generally inclined to try to help themselves."33 Even though the Quakers were encouraged by the progress of their school and the receipts remained adequate, by 1869 extraneous forces were causing them to re-evaluate their commitment. In 1868 the Mississippi "Black and Tan" constitutional convention, in which former slave-holders |

168 OHIO HISTORY

were a minority, accepted the concept of

public education. Furthermore,

many of the conservative elements in the

state accepted Negro education

as one of the consequences of the war.

For instance, the Jackson Daily

Clarion on several occasions called for some form of Negro

education

as long as it was controlled and

conducted by southern whites.34 Thus,

facing incipient state competition and

knowing that black teachers would

be needed in the newly created black

schools, the Quakers requested the

Freedmen's Bureau to establish a normal

or teachers' training school in

Jackson using the Friends' facilities.

In May 1868, Henry R. Pease, Super-

intendent of Education in Mississippi

for the Freedmen's Bureau, wrote

to Oliver 0. Howard, director of the

Bureau, in support of the idea of

a centralized normal school. Pease

explained that the Ohio Yearly Meet-

ing was anxious for the government to

take over its school.35 By September,

however, Pease reversed his opinion and

said the state governments should

provide for the education of Negroes.36

Although neither the state nor

the Freedmen's Bureau relieved the Ohio

Quakers of their teaching burden,

tile Bureau did donate $482 in building

materials and $18 in cash to the

school.37

In addition to political problems,

either because of the establishment

of a state-wide public education system

which provided for Negro educa-

tion as of July 1870 or because some

Quakers lost interest, each year after

1869 it was harder for the Ohio Yearly

Meeting to raise money to maintain

the school and harder still to get a

teaching staff for its operation. In

1871, however, state assistance did come

from Mississippi after the aid

received from the Freedmen's Bureau was

withdrawn. Because there were

not enough teachers to fill the

vacancies in the state's Negro schools,

the Hinds County Superintendent of

schools paid the tuition of the black

students and the salaries of the

teachers in the Quaker school, while the

"regulation and government of the

schools" remained in the hands of the

Quakers.38 This was only a

temporary arrangement, and the next year

the Ohioans lacked funds to open their

school. The Committee on Freed-

men for the Ohio Yearly Meeting thought,

however, that "the work

should not be abandoned at present, and

have made arrangements for

sustaining three teachers there the coming autumn and

winter."39

Their work was not abandoned, and the

Quakers opened the school

again in 1873. This year the Ohioans

faced opposition from both the

state school authorities and the local

white population. The state school

system, which had been created by a

Republican-dominated legislature,

was now under the control of Thomas W.

Cardoza, a Negro. To combat

the criticisms and unrest against the

new system, Cardoza turned to stronger

centralized control and was not

sympathetic with the Quaker's independent

efforts to give the blacks some form of

elementary education. The white

citizens of Jackson, too, were critical

of the Freedmen's school. Although

by 1873 the activities of the Ku Klux

Klan and other similar groups

against Negro schools in Mississippi had

subsided, the Quakers reported

to the Ohio Yearly Meeting that they had

faced "considerable opposition

|

QUAKERS AND FREEDMEN 169 from the authorities, and, to a considerable extent, from the public senti- ment of the white people of Jackson, it being asserted that our schools were an injury to the public schools, the children leaving the latter to attend the former."40 Evidently the Yearly Meeting itself was divided over the future of the Jackson endeavor. Even though the executive committee on Freedmen recommended that the school property in Jackson be sold and the proceeds be applied "to the education of the Freedmen at some other point,"41 other Quakers, at the same time, applied to the George Peabody Fund, which was dedicated to the growth and development of education in the South, for financial aid.42 The Peabody Fund, however, did not assist the Quakers. Thus, after almost a decade of work with the southern Freedmen, the Ohio Yearly Meeting was faced with failing financial support |

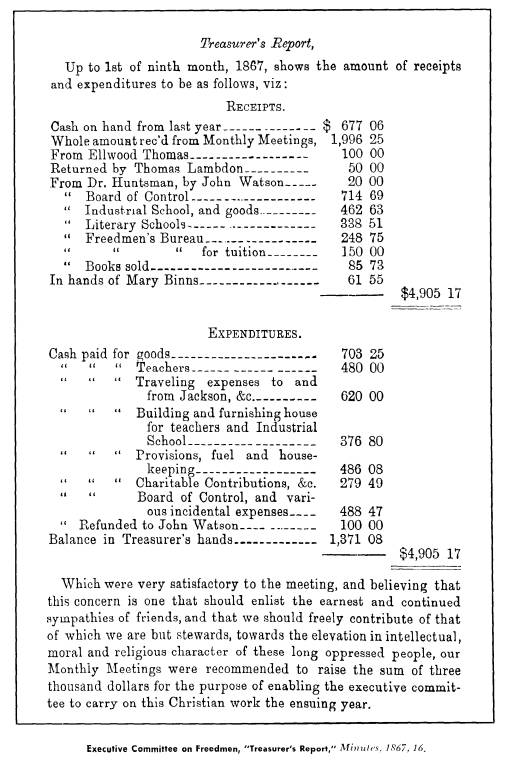

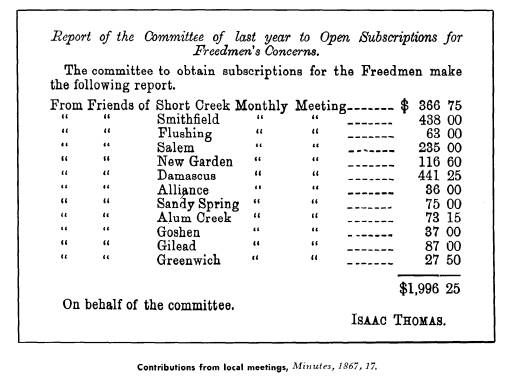

170 OHIO HISTORY

for the school and increasing local

white opposition. The future, indeed,

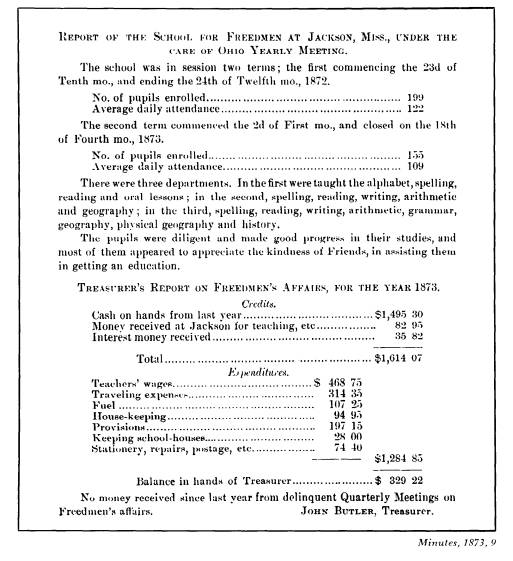

was not bright--the balance of funds on

hand at the end of 1873 being

only $329.22, down from an 1866-67

budget of $4905.17.43

The Quakers were able in some manner to

keep the school open for

two more drastically shortened terms

through 1874-75. As circumstances

grew worse, the Committee for the

Concerns of the People of Color in

its final report to the Ohio Yearly

Meeting explained that "in view of

the provisions made by the State of

Mississippi for the education of the

colored children, and the difficulty of

securing the funds necessary for

defraying the expenses of our school in

Jackson the Committee are united

in judgment that it is not best to

attempt to maintain a school there

the approaching winter."44 The

school never did open again under Quaker

jurisdiction, and in 1879 the

disposition of the property in Jackson, which

by that time was "considerably out

of repair," was committed to a small

committee headed by John Butler.

Butler's committee was to "sell, donate

or retain the property, as may best

accord with their judgment."45 It is

not clear what final disposition this

committee made of the Jackson

property since nothing was stated on the

subject in subsequent Yearly

Meeting reports. In any event, after

nearly ten years of work with the

Freedmen of Mississippi and expenditure

by 1875 of approximately

$27,557.60, the Ohio Quakers abandoned

their work in Jackson.46

Even though the Quakers' efforts with

the Freedmen were tapering

off, the Ohioans did not remain idle.

Coincidental with the later years

of the Freedmen's project, a great

outpouring of Quaker energy was directed

toward the cause of international peace,

national temperance, the advance-

ment of the Kickapoo and Pottawatomie

Indian tribes in Kansas, and to-

ward other home missionary activities.

The Ohio Yearly Meeting's work in

belalf of the Peace Association of

Friends in America, formed in 1867,

occupied the interests of Quakers for

nearly twenty years following the

Civil War. Their major emphasis was to argue

against the use of warfare

between Christian nations because the

resort to force to settle international

disputes was thought to be contrary to

the word of God. Ohioans were

asked to contribute $1000 to the

national association's first annual budget.47

In 1869, 618,337 pages of printed matter

concerning peace were distributed

from the association's printing office

in New Vienna, Ohio.48 Beginning in

1871 Ohio Quakers also tried to convince

their neighbors of the righteous-

ness of their own views on temperance

and circulated 80,000 pages of tem-

perance tracts, directed 95 temperance

meetings, established 22 juvenile

temperance societies in schools, and

conducted prayer meetings in 420 sa-

loons.49 Three years later

the Quakers intensified their temperance activity

and visited 526 families, saloons, and

individuals to convince those present

that the use of alcohol was ungodly.

They also disseminated 248,400 pages

of temperance literature.50 Interest in

the movement by the Ohio Yearly

Meeting continued throughout the remainder of

the nineteenth century.

Thus, by the last quarter of the

nineteenth century the Ohio Quakers

had put aside their concern for the

southern blacks and were looking

QUAKERS AND FREEDMEN

171

toward other fields in which to perform

their good works. As a pacifist

group the Quakers did not turn their

backs on their country during its

time of peril but addressed themselves

to problems that could be dealt

with in non-violent ways. Their labor

with the Freedmen in Jackson after

the war was a natural continuation of

their concern for the Negro which

they had witnessed long before the sectional

conflict. As a group, their

goals for the former slaves both in Ohio

and Mississippi were conservative.

They rarely spoke of social or civil

equality for the blacks but, consistent

with the consensus of northern educators

at that time and later popularized

by Booker T. Washington, the Quakers

wanted to make the Negroes

economically independent of white

society through academic and vocational

education. As the Friends themselves

explained:

Consistent members of our Society could

not conscientiously bear

"carnal weapons" even for the suppression of the Great Rebellion.

They dared not to imbrue their hands in

human blood. But let it

never be said that, in the contest with

the Slave Power, and in the need-

ful care of the suffering millions, who

were suddenly thrown as a

burden upon the government in the hour

of victory, they have not

nobly done their part.51

THE AUTHOR: Thomas H. Smith is

an assistant professor of history at

Ohio

University.