Ohio History Journal

BRIAN HARTE

Land in the Old Northwest: A

Study of

Speculation, Sales, and Settlement on the

Connecticut Western Reserve

Settlers who came to the American West

from the Northeast carried with

them a vision of what their new lives

would involve. The act of moving

to the West required a leap of faith, a

presumption that they could convert

their vision into reality. Despite their

uncertainties, these pioneers were

aware of and depended on certain existing

parameters that would stabi-

lize their lives in the new land. For

instance, the Northwest Ordinance of

1787 assured settlers that their new

homes would be safely within the con-

fines of the United States and its

political order. Also, they carried their

New England culture with them, and that

culture included a set of assump-

tions about their place in society and

the location of their markets. The land

speculator also had a vision, and the

act of investment required no less a

leap of faith on his part. The

speculator assumed that the territory in which

he was investing would develop into a

viable and integral part of the

country, rise in value, and return a

profit to him. As one of the first large-

scale targets for both settlers and

investors, Ohio became the testing

grounds for both settlers' and

speculators' confidence in the future of

Western settlement and development.

Thus, the settlement of Ohio played a

pivotal role in the shaping of West-

ern attitudes and East-West relationships.

In the late eighteenth and early

nineteenth centuries, the state and

national governments of the United

States began to distribute their western

lands to settlers and speculators;

much of this land was located in the

Northwest Territory and, specifically,

the Ohio country. The United States

Government and the various private

groups of speculators viewed the land

market in the Northwest Territory

as an opportunity to turn a fast profit.

Although some people actually made

a significant sum of money, lands sales

were not the surest path to riches

for many investors. A large plot in

northeastern Ohio known as the Con-

necticut Western Reserve had inherent

disadvantages that turned its ini-

Brian Harte graduated from Yale University

in 1991, where he completed this thesis for

the History Department under the

guidance of his friend and mentor, Jay Gitlin.

|

Land in the Old Northwest 115 |

|

|

|

tial promise into a financial debacle for many of the members of the Con- necticut Land Company. Because of the area's isolation and the slow pace of settlement, conditions for settlers on the Reserve were extremely spartan, even when compared to the generally difficult life of other early nineteenth-century frontier settlers. Despite the incentives offered by the Connecticut Land Company, rapid and comprehensive settlement and development of northeastern Ohio did not occur until the second quarter of the nineteenth century, when the completion of the Erie and Ohio-Erie Canals provided the area with a practical commercial link to the rest of the country. The Western Reserve was a small part of the area that came to be called the Northwest Territory, which in turn was part of a larger inheritance that the United States came into by the terms of the Treaty of Paris and from the cessions of various states (including Connecticut, Massachusetts, New York, Virginia, North Carolina, and Georgia) in the late 1780s. Numer- ous Indian groups inhabited parts of this land and presented a significant obstacle to American settlement of this inheritance. Although the British

1. The Erie Canal was opened in 1825, and in 1827, two more events paved the way for rapid economic development of the Western Reserve: the opening of the Ohio-Erie Canal, and the clearing of the mouth of the Cuyahoga. See chapters 10 and 11 of Harlan Hatcher, The Western Reserve, (New York, 1949). |

116 OHIO HISTORY

had prohibited colonists from settling

west of the Appalachian Mountains

by the Proclamation Line of 1763,

squatters had been trickling into the

Ohio River valley since the middle of

the eighteenth century. Most of them

settled south of the river: James Harrod

founded Kentucky's first perma-

nent settlement in 1774, and largely

through the efforts of the Transylvania

Land Company, one hundred and fifty men

lived in Kentucky by 1775.2

A few squatters, mostly trappers and

adventurous pioneers, had ventured

into the forested land north of the

Ohio, but such settlement was very

sparse, in part because of the Indian

threat. The ever-present danger of such

formidable tribes as the Miami,

Delaware, and Shawnee ensured that a set-

tler's life in the Ohio wilderness would

be lonely and insecure. However,

in the 1780s, the number of settlers

daring to establish themselves in Ohio

increased gradually, and the young

Confederation government took action

to regulate the settlement of its new

lands. By the terms of the 1785 Treaty

of Fort McIntosh, the government was

required to remove American set-

tlers from Indian lands, but even small

military excursions were ineffec-

tive in stopping the slow flow of

settlers to Ohio.3

The new American government needed to

keep a strict watch on the set-

tlement pattern of the West for a number

of reasons. First, the Confeder-

ation (and the later federal government)

was submerged in postwar debt.

The public domain was one of its few

assets, and sales to settlers could

therefore be used to help finance the

government. Second, a compact and

well-ordered settlement pattern was essential

for the protection of the

American settlers from Indian attacks.

Third, the development of repub-

lican government in the new areas--and

hence the protection of the fragile

republic of the East--depended on a

closely supervised plan of settlement,

growth, and government. The plans of the

government and of private com-

panies reflected the desire to establish

towns and governmental structures

that would ease the integration of these

new settled areas into the young

republic.

With these goals in mind, the Congress

of the Confederation debated

over and finally passed the Land

Ordinance of 1785. The general plan

called for surveyors to divide the land

into vertical ranges and square town-

ships, each six miles square. The

townships were further divided into

smaller tracts. The land was to be sold

in large townships and smaller lots,

theoretically to accommodate both

wealthy and less wealthy purchasers.

2. Kentucky grew rapidly: by 1782 there

were already 8,000 inhabitants, and it became

the 14th state in 1792. Source: Malcolm

J. Rohrbaugh, The Trans-Appalachian Frontier (New

York, 1978), 24-25.

3. For the most part, early Ohio

settlers ignored the threats of the Confederation's mili-

tia units, and when the troops destroyed

their dwellings, the settlers simply rebuilt their homes

as soon as the units departed. See

Rohrbaugh, 64-65.

Land in the Old Northwest 117

However, the terms of sale under the

Land Ordinance were too strict and

too expensive for the "common

buyer"--Congress demanded at least a

dollar per acre plus the cost of the

survey, payable immediately at the time

of sale. No terms of credit were offered

at first, and the land was sold only

at a public auction in New York City,

further restricting sales. Not sur-

prisingly, the government sold less than

73,000 acres of land in 1787.4

Because initial sales in small tracts

were so slow, Congress promptly

violated its policy of trying to cater

to small buyers by selling giant chunks

of land to wealthy groups of

speculators. Shortly after passing the North-

west Ordinance in 1787, Congress sold

the Ohio Company one million

acres for less than ten cents per acre,

and further authorized the Treasury

to negotiate for the sale of huge--over

a million acres--tracts to other

interested parties, such as the Scioto

Company and the John Cleves

Symmes group, at equally low prices.5

Although the government raised

large sums quickly by these actions,

public land sales may have been hurt

in the long run by the competition that

these private speculators would soon

provide for the government's own land

agents.

As settlement proceeded, the Indian

problem became more and more

significant. A series of undeclared wars

began with the establishment of

the first settlements in the territory.

The Indians, armed and assisted by

the British in Detroit and Canada,

effectively utilized raiding tactics to

disrupt settlements in the Ohio country.

The federal government became

increasingly worried about these Indians,

in part because its inability to

establish order within its own

boundaries caused international embarrass-

ment at a time when the new country was

seeking recognition from Eu-

rope. The Indians routed two American

military expeditions, the first led

by General Josiah Harmar in 1790, and

the second led by Arthur St. Clair

in the following year. Finally, on

August 20, 1794, General Anthony

Wayne led carefully trained militia

units to Fallen Timbers, where he de-

feated a confederacy of Indian tribesmen.

The subsequent Treaty of

Greenville mandated that the Indians

vacate most of the land in present-

day Ohio, leaving most of the area open

to white settlement.6 The ensu-

ing movement of people into the

Territory forced Congress to reconsider

its sales and credit policies to

accommodate the new settlers.

Congress then formulated the Land Law of

1796, which offered more

latitude to the small purchaser and

settler. Although the price of land rose

4. Rohrbaugh, The Land Office

Business (New York, 1968), 10-11.

5. Because of this policy, the Land

Ordinance of 1785 was essentially disregarded: "the

first arrangements for the disposal of

the public domain stood discredited and unused. The

rectangular system of surveys was a

disappointment because of its slowness and expense."

Rohrbaugh, The Land Office

Business,11.

6. See Thomas D. Clark, "Fallen

Timbers, Battle of," and "Greenville, Treaty of," in The

Reader's Encyclopedia of the American

West, ed. Howard R. Lamar (New York,

1977).

118 OHIO HISTORY

to a minimum of two dollars per acre,

buyers were given a year to pay the

full price; cash purchasers received a

discount. The law also permitted land

sales to occur in towns in the

territory, such as Cincinnati. However, the

minimum purchase size was 640 acres,

still too large and expensive a pur-

chase for a small-time buyer. Thus,

although Congress had high expecta-

tions for the new land law, sales were

very slow--only 49,000 acres were

sold in 1796 7--because the government

was not offering terms of sale

that were competitive with the offers

that the private companies made.

Ironically, in order to raise money, the

government had earlier sold large

plots at fantastically low prices to

these same companies which were now

undercutting the federal land agents.

For example, the John C. Symmes

group could offer a smaller minimum

purchase at one dollar per acre with

better credit terms than the Land Law of

1796 permitted.8 For the most

part, then, settlement was limited to

the lands owned by the speculative

companies; westward immigrants generally

avoided the public lands. After

only three years under the new law,

Congress began once again to plan a

new land sales strategy, this time with

the help and guidance of a repre-

sentative from Ohio.

Under the terms of the Northwest

Ordinance of 1787, when the popu-

lation of a territory passed five

thousand free white males of voting age,

its general assembly was permitted to

elect a delegate to Congress. The

Northwest Territory's first legislature

convened in 1799 and chose William

Henry Harrison as its representative in

Washington. Advised by Harrison,

Congress passed a new land law in 1800

that was more advantageous to

small buyers than the previous

legislation. Most significantly, the law ex-

panded the credit terms on land

purchases to allow up to four years of an-

nual installment payments. It also

reduced the minimum purchase size to

320 acres.9

The law of 1800 also created four land

districts in Ohio to better facili-

tate the sales of land from outposts in

the Northwest Territory; the districts

were centered in Cincinnati,

Chillicothe, Marietta, and Steubenville. Al-

though people continued to complain that

the terms of sale were still too

difficult for many potential buyers to

meet, income from sales of public

land increased significantly, reaching

10 percent of the total national in-

come in 1814.10 As settlers filled up

the Ohio country, Congress opened

7. Rohrbaugh, The Land Office

Business, 18.

8. Ibid., 18-19.

9. The Land Law of 1800 was the last

major piece of land policy legislation until 1820,

when Congress further reduced the

minimum price and the minimum tract size. For details

on the Land Law of 1800, see Rohrbaugh, The

Land Office Business, 19-22.

10. In his article "Land Policy,

1780-1896," from the Reader's Encyclopedia of the Amer-

ican West, P. W. Gates reports that land sales as a percentage of

national income rose to this

level from only 4 percent in 1805, and

rose further to 13 percent by 1819.

Land in the Old Northwest 119

up new territories in Illinois and

Indiana, and Jefferson's Secretary of the

Treasury, Albert Gallatin, established

six new land office districts in the

Northwest Territory (two were located in

Ohio), and another in St. Louis.

Although United States land policy would

continue to evolve during the

course of the nineteenth century, the

law of 1800 was a landmark piece of

legislation that attempted to address

directly the problems that both

buyers and sellers had encountered in

trying to settle the American West.

Although most of the Northwest Territory

fell under the Federal gov-

ernment's jurisdiction, some parts were

never public domain lands. For

instance, Virginia and Connecticut

maintained claims to large tracts of

land in the Ohio country. Virginia used

its reserved lands between the Lit-

tle Miami and Scioto Rivers to

compensate Revolutionary War veterans,

and, for the most part, this area was

not the site of large-scale speculative

ventures. Referring to its original

colonial charter of 1662, Connecticut

claimed a strip of land that extended

from Pennsylvania to the Mississip-

pi River. Although the state ceded most

of its western claims to the Con-

federation in 1786, Connecticut

maintained its claim to a piece of land that

fronted Lake Erie, extending 120 miles

to the west of the Pennsylvania

border, as a means of raising revenue

for the new state government.

Against the larger backdrop of United

States public land policies, the sce-

nario of speculation and settlement that

occurred on the private lands of

the Connecticut Western Reserve provides

a striking example of mis-

management and unmet expectations.

In 1795, after several years of

bickering, the General Assembly of

Connecticut created a committee of eight

legislators to organize the sale

of the Western Reserve to any interested

persons or groups for at least one

million dollars. The money from the sale

was designated to initiate the

Connecticut School Fund, a still-extant

endowment for the support of pub-

lic schools in the state. In response to

the offer, a group of wealthy New

England men formed an association in

September of 1795, organizing

themselves as the Connecticut Land

Company. After a month of negoti-

ations, the Connecticut Land Company

purchased the state's holdings in

northeastern Ohio for $1,200,000, with

most of the money to be paid out

on a five-year credit plan.11

11. A history of the Connecticut Land

Company can be found in the 1915-1916 Annual

Report of the Western Reserve Historical

Society (Cleveland, 1916), also referred to as Tract

No. 96 of their collection. "The

Connecticut Land Company and Accompanying Papers,"

edited by Claude L. Shepard, contains a

detailed history of the company as well as a num-

ber of documents that pertain to its

history and to the history of the Western Reserve- char-

ters, committee reports, and much more.

For details on the purchase of the Western Reserve,

see the "Report of the Connecticut

Committee on the Sale of the Western Reserve, Septem-

ber, 1795," pages 125-44.

120 OHIO HISTORY

The fifty-eight members of the Company

associated themselves into

thirty-five shareholding

"purchasers," with a purchaser sometimes con-

sisting of two or three men. The largest

investor, Oliver Phelps, invested

over $200,000 in the company.12 Most

of the men were from Connecticut

and, like Rufus Putnam of the Ohio

Company and John C. Symmes, they

were interested in making a fast profit

by entering the Ohio land market

when it was in its infancy.

The board of directors of the company

formulated plans for extin-

guishing Indian claims, surveying the

land, and selling it. Their first order

of business was to survey and partition

the Company's holdings. Although

many legislators and Company members had

assumed that the Western Re-

serve tract consisted of over three

million acres, the Reserve was really

an unmeasured quantity. In fact, the

Company members received an un-

pleasant shock when the first surveying

parties, led by Moses Cleaveland

and Augustus Porter in 1796, discovered

that their property actually con-

tained just under three million acres.

Unfortunately, in their overconfi-

dence, the Company had already sold the

rights to any Reserve lands in

excess of three million acres to the

Excess Company, which had then sold

the title to William Hull. Hull did not

lose all of his money immediately,

though--he was taken into the Company

and allowed to share in the prof-

its from land sales.13

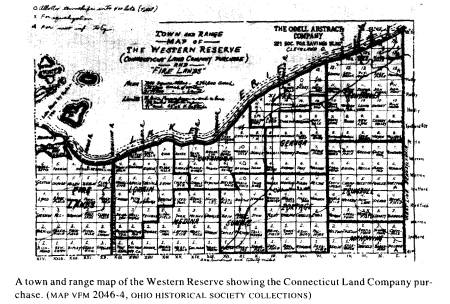

The Company's teams surveyed the Western

Reserve along the lines of

the method mandated by the Land

Ordinance of 1785. That is, the tract was

divided into vertical ranges that were

numbered from east to west, and the

townships, each a unit of land five

miles square, were numbered within

each range from south to north. The land

was divided among the members

of the Company in an elaborate lottery

designed to compensate the

choosers of "bad lots" with an

appropriate number of "good lots." The

Company's Articles of Association also

included clauses that would al-

low the directors to set aside parcels

of land containing salt springs, the

sales of which would directly profit the

Company. The Company took ad-

vantage of this provision in 1798,

reserving a two-thousand acre tract of

land containing a salt spring and

attempting to lease it to future settlers.14

This venture proved unprofitable,

possibly because none of the settlers had

the means to pay for salt in 1798; in

fact, there were hardly any settlers at

all in 1798.

12. WRHS Tract No. 96 also contains

documentation of the original membership of the Con-

necticut Land Company, along with each

person's investment and holdings (pages 131- 34).

13. The error was due to inaccurate maps

which misplaced the Lake Erie shore. Much of

the land that the surveyors expected to

find was actually located in Lake Erie. The story of

the discovery of the error and the fatl

of the Excess Company is related in Hatcher, 39-43.

14. WRHS Tract No. 96, 83.

Land in the Old Northwest 121

Unfortunately, the members of the

Connecticut Land Company mis-

calculated the value of their purchase

and the desirability of the land to

eastern settlers. The members hoped to

make their profits exclusively from

the sale of land to settlers, believing

that the Reserve was primed for the

rapid settlement that was beginning to

occur in the Ohio Valley. They were

mistaken. Sales would be painfully slow,

a condition that was exacerbat-

ed by the general ignorance among the

investors about what the Western

Reserve consisted of and how to best

manage it.

The primary reason that sales of Reserve

lands would prove initially dis-

appointing was that the area was

essentially detached from the markets and

resources of the Ohio Valley and the

East. The lands in the middle and the

south of the state were fertile and well

watered. Natural resources, in-

cluding coal and timber, were abundant

in the southeastern part of the terri-

tory, where the Appalachian foothills

cross through the Ohio Valley. Most

importantly, a system of rivers,

including the Miami, the Scioto, and the

Muskingum, connected much of the state

to the Ohio River. The Ohio was

the economic link between the settlers

in the Territory and the cities of

Pittsburgh, New Orleans, the Eastern

ports, and the rest of the world. Set-

tlers in the Ohio Valley utilized these

rivers to sell the products of their

labor--mostly corn, wheat, and

livestock--to buyers in the South and

East. The result was the development of

an "economic axis" extending

from Pittsburgh to New Orleans along the

Ohio and Mississippi rivers,

through which settlers could also obtain

materials and supplies not avail-

able in the Northwest.15

In contrast, the Western Reserve land,

while also good farming land, was

isolated from the American market

system. To the east, the Appalachian

mountains inhibited the establishment of

efficient overland trading routes

with Eastern cities. The Reserve was

also sufficiently far north to prevent

efficient and economical overland

transportation of goods from and to the

Ohio River network. The Reserve's

extensive river system flowed into

Lake Erie, but to the north the Niagara

Falls and often-frozen St. Lawrence

River prohibited traders from reliably

travelling along this system back

to the East; furthermore, this route cut

through British Canada, and the

Montreal traders were not likely to give

preferential or fair treatment to

American farmers.

Realizing the need to compete

effectively in the Western land market,

the directors of the company did try to

provide incentives for settlement.

In its Articles of Association, the

Company allowed the directors to make

special provisions to the first settlers

on the Reserve. These were pioneers

15. The development and effects of this

important trade network in the Mississippi basin

is thoroughly discussed in Rohrbaugh, The

Trans-Appalachian Frontier, 93-1 14.

122 OHIO HISTORY

who would have to build their homes and

farms, improve the land, and

make a living without the benefit of

neighbors or experience. To better

accommodate them, the directors

identified the first townships to be set-

tled and paid for the erection of

sawmills and gristmills there. When the

city of Cleveland was founded in July

1796 at the mouth of the Cuyahoga,

settlement of the Western Reserve was

officially opened.

However, settlement proceeded slowly,

and the Company quickly de-

cided that further steps were necessary

to promote settlement. In 1797 and

again in 1798, the Company moved to

appropriate funds for the con-

struction of roads and bridges to

facilitate both internal transportation

through the Reserve and roads into it

from the East.16 In 1801, the Com-

pany paid for the construction of a road

from Buffalo through western New

York and Pennsylvania to the Reserve, an

indication that immigration was

occurring too slowly for the Company's

liking.17 Roads were not the only

investments that the Company made to

promote settlement. In 1798, the

purchasers voted to authorize the

directors to give small parcels of land

in Cleveland to blacksmiths and

mechanics. The directors also occasion-

ally gave free land to early settlers to

pay them back for "risque and hard-

ships encountered," and even to one

James Kingsbury and family for hav-

ing the first child born on the Reserve.18

Despite these attempts to improve the

land, Samuel Huntington attested

to Moses Cleaveland in several letters

that settlement and economic

conditions on the Reserve remained very

poor. Huntington was a Yale grad-

uate who migrated to Ohio in 1800 and

participated extensively in Ohio

politics. In a series of letters to

Cleaveland, the general agent for the Con-

necticut Land Company, Huntington tried

to rally support for Company-

sponsored improvements to the Reserve.

In 1801, he informed Cleaveland

that the roads into the city of

Cleveland were poorly maintained, needing

occasional cutting and clearing because

of storms.19 Little seems to have

been accomplished on that front, because

even as late as 1819, a land agent

named Seth Tracy complained that roads

in the eastern part of the Reserve

were so "extremely bad" that

it was difficult to promote and sell land.20

16. Roads within the Reserve were

desperately needed because instead of arranging for

an orderly settlement pattern, the

Company distributed its land to its members all at once.

This was a vital error, because it

resulted in settlements that were widely scattered over the

land, instead of a slowly moving

"frontier" of concentrated settlement.

17. WRHS Tract No. 96, 81.

18. More instances of the Company's

incentives are detailed in WHRS Tract No. 96,

79-83.

19. WRHS, Tract No. 95, The Samuel

Huntington Correspondence 1800-1812, 68.

20. Seth Tracy to Pierpont Edwards, 11

January 1819, Pierpont Edwards Papers, Yale Uni-

versity Manuscripts and Archives, New

Haven.

Land in the Old Northwest 123

Other travellers to the Reserve also

mentioned the poor state of roads and

the economic hardships of early Reserve

residents.21

Huntington also claimed that the lack of

a harbor in the city was a ter-

rible burden on the settlers, because it

was impossible for them to obtain

cheap goods through the Great Lakes

system without a suitable port. A

sharp bend in the Cuyahoga River just before

its junction with Lake Erie

prevented commercial craft from entering

the river. The bend also hindered

the smooth flow of water out of the

Reserve, and as a result, the river was

a stagnant marsh near its mouth.

Huntington wrote that because of the lack

of a proper port, "our salt iron,

potash & sugar kettles & such bulky arti-

cles cost us more to get from the falls,

than all the rest of the distance."

He encouraged the Company to invest a

significant amount of money into

the construction of a harbor at the

mouth of the Cuyahoga, boasting that

if Cleveland had a harbor, its people

"might supply the Ohio Country ...

cheaper than they can be supplied from

Pitt."22

Access to specie was another serious

problem that settlers everywhere

in the American West faced, and

Huntington confirmed that the Western

Reserve settlers seemed to have a

particular difficulty in obtaining cash.

A variety of currencies circulated in

Ohio: dollars, livres, pounds, notes

of the assorted state banks, and U.S.

Bank notes. In the late 1790s, furs,

services, and whiskey were acceptable

means of payment. Even in 1810,

land, cattle, and notes of credit served

as common transaction media in the

Reserve.23 Few settlers came

to Ohio with a significant amount of money,

and with a limited access to Eastern

markets, their ability to obtain money

was virtually nonexistent. Likewise,

they were unable to obtain the goods

and materials that they needed for a

comfortable life. Huntington wrote that

"[settlers] run to the merchants

with what money they can pick up, to buy

at an exorbitant price such articles as

they had been used to consume in the

old countries, without having any way of

exporting such commodities as

they might manufacture & send to

raise money."24 President Jefferson's

Embargo Act of 1807 exacerbated the

money problem by depressing the

New England commercial class and

stifling the little commerce and ex-

change that did exist between the East

and the Western Reserve.

The actions of the Connecticut Land

Company and the conditions on the

Western Reserve should be compared to

analogous proceedings on the

21. Among those who echoed Huntington's

complaints about the poor drainage of the riv-

er, the sorry condition of Reserve

roads, and the poor standard of living that existed on the

Reserve were the Rev. Joseph Badger (in

1800), John Melish (in 1811), and Dr. Zerah Haw-

ley (in 1820). See Hatcher, 76-88.

22. Huntington to Cleaveland, 15

November 1801, from WRHS Tract No. 95: Letters from

the Samuel Huntington Correspondence

1800-1812, 68.

23. Rohrbaugh, The Trans-Appalachian

Frontier, 104.

24. WRHS Tract No. 95, Huntington

Correspondence 1800-1812, 74.

124 OHIO HISTORY

other major private holdings in this

early American West. The Holland

Land Company's Purchase, a 3.3 million

acre tract in New York between

the western edge of that state and the

Genesee River, provides a conve-

nient comparison. Although the western

edge of the Holland Purchase was

about fifty miles east of the Ohio state

line, its size, features and early his-

tory were comparable to the Reserve. The

lands were purchased in 1792

by a group of Dutch investors. However,

in their organization and plan-

ning for land sales, the Dutch far

outmanaged their Connecticut rivals.

The clearest difference between the

policies of the two companies was

in their respective preparations for

sales. The Western Reserve was opened

for settlement less than a year after

its purchase, largely still unsurveyed

and unimproved. The Holland Tract was

set aside while developers

planned the establishment of

"frontier services" such as taverns, mills,

schools, churches, artisan shops, and

stores. They knew such services

would be attractive to and needed by

settlers. Before a single acre had been

sold, the owners had planned and

developed a network of villages and roads

to accommodate an effective market

system that was connected to Mon-

treal and New York City. They had also

rated the townships according to

a "quality index" that was

based on an analysis of the soil, vegetation,

drainage, and terrain in each area. The

indices helped them predict the pat-

tern of settlement and guided their

pricing and development policies. The

land was finally opened in 1800, after

eight years of such planning.25

Although the sales of land in upstate

New York were slow in the early

years, by 1803 land sales surged, and in

1810, more than fifteen thousand

people inhabited the Holland Tract. The

price of land rose from an aver-

age of slightly over two dollars per

acre in 1804 to as high as $4.50 per

acre in some areas in 1811.26 The

pricing policy of Joseph Ellicott, the res-

ident land agent, was fluid and

flexible. He was careful to coordinate his

pricing with local settlement patterns

and the quality of the land, instead

of simply mandating a minimum price for

all lands. The directors of the

Connecticut Land Company did not have

the foresight or the organization

to manage their tract so effectively.

For a number of years, the directors

also were unable to solve a prob-

lem concerning the questionable legal

status of the Company's claims; this

problem slowed settlement further. In

addition to the original sale of the

Western Reserve land area, the

Connecticut Land Company had also pur-

chased the rights to the

"juridicial and territorial right" to the tract, which

25. These surveys, land assessments, and

development plans are thoroughly discussed in

chapters 2-4 of William Wyckoff's

history of the Holland Land Company, The Developer's

Frontier (New Haven, 1988).

26. Wyckoff includes a number of charts

and maps; these data were extracted from in-

formation presented on pages 71 and 122.

Land in the Old Northwest 125

meant that the state of Connecticut had

forfeited to the Company its title

to the land and its right to govern it.

However, the validity of Connecti-

cut's initial title to the Reserve lands

was not at all certain because nu-

merous squatters and rival Pennsylvania

land-holders and speculators also

claimed land on the Reserve. Nor was the

method by which a new gov-

ernment should be established on the Reserve

certain because, to the cha-

grin of Governor Arthur St. Clair, the

area did not fall under the jurisdic-

tion of the Northwest Ordinance.

Settlers were unwilling to purchase and

settle land when the Company could

neither guarantee their titles nor pro-

vide a system of law to protect them.

In an attempt to solve this problem, the

Company urged the government

of Connecticut to accept authority over

the Reserve. The state refused to

do so, and in 1797 the Connecticut

Assembly tried to release jurisdiction

over the land to the United States

government.27 The following year, the

Connecticut Land Company also appealed

to Congress to accept juris-

diction, but both of these movements

were spurned by Congress. Finally,

in 1800, Congress appointed a committee

under John Marshall to consider

the cession of the Reserve into the

jurisdiction of the federal government.

Upon the committee's recommendations,

Congress passed the "Quieting

Act" in April, 1800. The law

authorized the President to deliver letters

patent to the governor of Connecticut

" ... whereby all the right, title, in-

terest, and estate to the soil of that

tract [the Western Reserve] ... shall be

released and conveyed ... to the said

governor ... for the purpose of quiet-

ing the grantees and purchasers ... and

confirming their titles to the soil

of the said tract of land." In

return, Connecticut was to "renounce forev-

er, for the use and benefit of the

United States, ... all territorial andjuris-

dictional claims [of the Western

Reserve]."28 The conditions for cession

were quickly met, and on July 10, 1800,

Ohio's Governor St. Clair an-

nounced the incorporation of the Western

Reserve into the Ohio Territo-

ry as Trumbull County.

However, these years of title

difficulties and sluggish sales had presented

a series of immense problems to the

Company members. In 1800, Marshall

reported that the Company had paid only

$100,000 of interest on the pur-

chase money to the state of Connecticut,

and that only about one thousand

people lived on the Reserve.29 In

May of that year and again in October,

the directors of the Company petitioned

the Connecticut Legislature to re-

27. The preceding information about the

Connecticut Land Company's difficulty with the

jurisdictional problem and the

accompanying problems of attracting settlers to this land can

be found in the more detailed history of

the same on pages 85-86 of WRHS Tract No. 96.

28. The "Accompanying

Documents" section of WRHS Tract No. 96 includes a transcript

of the Quieting Act (page 211).

29. WRHS Tract No. 96, 86.

126 OHIO HISTORY

lax the repayment terms of the Company's

original purchase. The direc-

tors complained that, due to the

title-issue embarrassment, the members

of the Company had been forced to sell

land at half its value, and were

"obliged to advance their other

property" in order to settle their debts with

the state.30 However, their

attempts to earn a credit reprieve were insuf-

ficient to relieve the Connecticut Land

Company's financial difficulties

or to save it. On January 5, 1809, the

Company was dissolved after less than

fourteen years of existence. At that

time, many of the original investors

who owed money to the state for the

purchase of the Reserve were unable

to make payments on their debts. The

managers of the Connecticut School

Fund, to which the proceeds of the

state's original sale of the Reserve were

allocated, issued a report that showed

that "a large amount of interest [on

the debts owed by the members of the

Company] was unpaid and that the

collateral securities of the original

debts were not safe."31

Just as Congress took years to formulate

a reasonable land policy be-

cause its members did not understand the

difficulties that settlers en-

countered on the frontier, the investors

in the Connecticut Land Compa-

ny never comprehended how difficult life

on the Reserve was: there was

no money, no supply of cheap goods, no

provisions for public education,

and no government--in short, no

convincing reasons to settle. The mem-

bers of the Company had hoped to profit

from the westward migration by

establishing a link between New England

and the Northwest Territory, but

during fourteen years of Company neglect

and mismanagement, most in-

vestors had never laid a foot on the

soil of their investment. Their igno-

rance of Reserve conditions contributed

greatly to the downfall of the

Company. Furthermore, the members of the

Connecticut Land Company

competed directly with each other for

settlers, a situation which reduced

their profits further, unlike the

members of the Holland Company who co-

ordinated their land sales within large

agencies.

The dissolution of the Company forced

the former members to inde-

pendently take on the duties that the

Company had assumed, including pro-

viding for publicity, incentives, and

improvements. However, their lack

of knowledge about their tracts often

prevented them from effectively im-

proving settlement. Pierpont Edwards was

one of the major investors in

the Connecticut Land Company. The

youngest son of the Reverend

Jonathan Edwards, he was a prominent

lawyer, politician, and judge in

New Haven and Bridgeport between his

first election to the state legisla-

ture in 1777 and his death in 1826. He

was a leader in the Democratic-

Republican party and a major liberal

voice in state politics. He was also

30. Ibid., 87.

31. Ibid., 91.

Land in the Old Northwest 127

a promiscuous land speculator, entering

into ventures in Vermont, South

Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Ohio. He

worked as an attorney for both the

South Carolina Yazoo Land Company and

the Connecticut Susquehanna

Company. Edwards invested sixty thousand

dollars in the Connecticut

Land Company, thereby laying claim to 5

percent of the Company hold-

ings on the Reserve.32 A

large piece of his land was located in present-day

Trumbull County, near the eastern edge

of Ohio; the agents that managed

his land there worked out of the town of

Mesopotamia, near the county seat

of Warren.

Pierpont Edwards was living proof that

speculators were not always

fully aware of the proceedings of their

land agents or of the conditions

under which settlers lived on the

Reserve. Although the Connecticut Land

Company was a failure, Edwards did not

learn from its mistakes and im-

prove his own managerial techniques.

Settlement upon his Reserve lands

remained erratic and slow after 1810.

Edwards' first agent in the Western

Reserve was his son John S. Edwards, who

died in 1813. The younger

Edwards, although a prominent Ohio

politician, was unsuccessful in sell-

ing his father's land, although his

father seems to have been completely

unaware of this fact. In a letter to the

man who became his next agent, Seth

Tracy, Pierpont Edwards confessed that

he "was utterly ignorant as to what

lands of mine in Mesopotamia have been

sold by my departed son. I have

had no account from him of a later state

than sometime early in the year

1807."33 The elder Edwards had not

only been out of touch with his son

and land agent for six years, but also

apparently had never been in the Re-

serve. Furthermore, he did not even

venture out there during Tracy's trou-

bled tenure as his land agent, which

lasted until 1819. Edwards had no idea

how much money his son had made for him,

what lands of his were reg-

istered at the land office, or how much

land his son had sold. The corre-

spondence to Edwards from Tracy during

the years of Tracy's tenure re-

veals what may have been commonplace

among speculators on the

Reserve: a great deal of mismanagement

and poor decision making on

Edwards' part. Tracy's difficulties in

dealing with the issues of money and

sales stand out in the letters, and his

problems in trying to communicate

these distinctly frontier complications

to his uncomprehending employ-

er in New England are evident, too.

Tracy clearly discloses Edwards'

frustrations with the slow pace of land

sales in his letters. Although the real

reason for the poor level of settle-

ment was the economic difficulty of

living on the Reserve, Tracy mentions

32. From listing of Connecticut Land

Company investors in WRHS Tract No. 96,

131-34, Source for Edwards' biographical

information: Dictionary of American Biogra-

phy, VI, 43-44.

33. Edwards to Tracy, 9 September 1813,

Edwards Papers.

128 OHIO HISTORY

other factors that contributed to the

situation. In 1814, he reported that the

ongoing War of 1812 had "much

retarded emigration from the East-

ward," and that fighting in the

Great Lakes area had discouraged settle-

ment of northern Ohio.34 Tracy

also reported that the war hampered his

efforts at collecting money from the

settlers, perhaps because Jefferson's

embargo of 1807 and the subsequent War

of 1812 interfered with com-

merce on the Great Lakes, too. In any

event, money was even less avail-

able than it normally was.

The limited availability of money and

the corresponding need for a gen-

erous credit policy created a number of

problems for Pierpont Edwards.

Foremost was the inability of settlers

to pay their installments when they

came due. Although Huntington had

reported to Cleveland about the

scarcity of currency back in 1801, Tracy

refers to it frequently as late as

1818. Shortly after assuming his duties

as Edwards' land agent, Tracy de-

duced that the settlers in the Trumbull

county area had been negligent in

making their payments, and that the sum

coming to Edwards in overdue

payments was "considerable."35

However, settlers typically did not even

have much money with them

when they arrived in the Reserve, and

they needed most of what they had

to establish themselves on their new

lands. According to Tracy, many of

the settlers who were unable to make

their payments followed one of two

paths: they either attempted to make a

partial settlement by paying part

of their debt or renegotiating their

contract, or they simply left their land

behind without paying or bothering to

void the contract.36 The latter group

of settlers presented an especially

difficult problem because, along with

the instances in which settlers died

with outstanding debts, each case had

to be dealt with on an individual basis.

The subsequent process of nego-

tiating each case required extensive

communication between the agent and

the owner, which was difficult because

of the great distance between them.

Other settlers arrived at a compromise

that helped them finance their

move to New Connecticut. Some used their

Connecticut property as a par-

tial payment for land in the Reserve.

Tracy described this system in a let-

ter in 1813: "land in the adjacent

town is for sale two and three dollars

per acre except in some cases where

exchanges have been made for farms

in the state of Connecticut which seems

to be the mode that many of the

land holders have adopted for several

years past to settle their lands."

Such a transaction benefited both buyer

and seller. The settler who en-

tered into such a deal was freed of the

difficulty of obtaining cash for the

34. Tracy to Edwards, 16 September 1814,

Edwards Papers.

35. Tracy to Edwards, 25 October 1813,

Edwards Papers.

36. Tracy to Edwards, 7 May 1814,

Edwards Papers.

Land in the Old Northwest 129

land payment and able to use what

available cash he had to establish him-

self on his purchase. Tracy thus

encouraged Edwards to enter into these

land-exchange agreements because they

were attractive to settlers and

therefore "advanced the price of

lands." Furthermore, the speculators

could oversee the condition and sale of

Connecticut lands much more con-

veniently than their Reserve lands six

hundred miles away. A Connecti-

cut parcel would also have held a much

more certain and stable position

in the real estate market than the

speculator's Ohio holdings. However,

Tracy never indicates in subsequent

letters that Edwards showed any in-

terest in the bargain.37

In general, Edwards was very frustrated

by the credit and payment sys-

tem that prevailed in the Ohio country.

Yet, for several years, he appar-

ently did not outline a specific credit

policy for his agent to follow. Tracy

therefore usually took the initiative in

establishing flexible terms of

credit in order to encourage settlement.

In 1817, he reported that he had

drawn up a contract with two men who

"were unable to pay any money

down, but I thought it would be for your

interest to settle them as they were

from the Eastward and whose people will

be likely to follow their friends."

The price of the land was three dollars

per acre, a very low price for 1817

compared to other deals Tracy was

making, and he allowed the two men

four years to pay their debt. Not happy

with such terms, Edwards sharply

scolded Tracy in 1818, insisting that in

future contracts, he receive some

significant down payment and that credit

be limited to three or four years

of annual payments.38

Edwards' poor knowledge of the

conditions on his western lands was

evidenced in his continuing insistence

that the price of his land remain sub-

stantially above the market value of the

surrounding lands. One of Tracy's

first observations upon taking office

was that Edwards' son--the first

agent--had substantially overvalued his

land. The Reserve was a buyer's

market, and Edwards faced stiff

competition from his neighbors for a lim-

ited number of interested settlers. On a

number of occasions Tracy reported

to him that the price he was demanding

was well above the price for "wild

lands" in the immediate vicinity.

In 1815, Tracy complained that Edwards

was asking for at least four dollars per

acre on all lots, regardless of the

land's quality--a situation that made it

nearly impossible for him to sell

37. Tracy twice makes mention of this

land-exchanging procedure: he describes the past

use of it by settlers in a letter to

Edwards dated 25 October 1813, then repeats his request

for further instructions on the subject

in the letter of 7 May 1814, but thereafter never rais-

es the subject again.

38. This incident is related by Tracy in

a letter to Edwards dated 5 May 1817. Edwards

rebukes him and sets his own credit

standards in a response to Tracy dated 5 June 1818. See

Pierpont Edwards Papers.

130 OHIO HISTORY

land.39 Five months later, he

elaborated on the price of his neighbors'

lands, stating that "no sales of

land can be made to any great amount while

lands contiguous to this place are

offered for two dollars and fifty cents

and three dollars per acre."40

And again, two years later, Tracy, admon-

ished for selling lots at three dollars

per acre, informed Edwards that his

"neighbors ... selling land around

me hold their land at three and four dol-

lars per acre, chiefly at three, and

unless I sell at the market price, few or

none will purchase."41 By

1818, Edwards seems to have finally acquiesced

to his agent's advice, giving permission

to Tracy to sell for as low as four

dollars per acre, which by then was near

the market price (although he

still pressed him to try to sell as high

as five dollars). He also permitted

sales on credit, provided that the

installments and interest were paid

promptly.42

Tracy had plenty of trouble in trying to

collect any money at all, but

sometimes settlers made payments in

currency that was drawn on local

banks. Obtaining currency that was

acceptable to Eastern banks was an-

other significant problem for the land

agent. Often, Western banks could

not back their currency with specie,

therefore making such money unus-

able to Eastern business and financial

centers. Many Western banks were

poorly managed, and unauthorized banks, unsound

currency, and coun-

terfeiting abounded in the Ohio country.

Even many of the Western

banks, such as the Western Reserve Bank

in Warren, would not accept the

currency of their neighboring banks

because they could not "hold out the

least encouragement of its being paid

for in specie."43 Therefore, in

1817, Tracy explained to Edwards that he

was having trouble collecting

"such money as is current in your

country which is very scarce here."44

In February 1818, he further reported

that "it is with much difficulty ...

that current money on the Eastern banks

can be procured while money is

so scarce and land buyers so unable to

pay their installments when they

become due."45

39. Tracy to Edwards, 23 January 1815,

Edwards Papers.

40. Tracy to Edwards, 17 June 1815,

Edwards Papers.

41. Tracy to Edwards, 7 May 1817,

Edwards Papers. Note that Edwards was not the only

one who was trying to sell his land at a

high price. For instance, Moses Cleaveland origi-

nally asked for 50 dollars per acre,

reports Hatcher, but many prospective buyers "even balked

at $25." Hatcher, 67.

42. Tracy to Edwards, 5 June 1818,

Edwards Papers.

43. Simon Perkins to William Crawford, 8

January 1817, quoted in Carl Wittke, ed., The

History of the State of Ohio (Columbus, 1942), vol. 2, The Frontier State

1803-1825, by

William T. Utter, 279.

44. Tracy to Edwards, 26 December 1817,

Edwards Papers.

45. Tracy to Edwards, 2 February 1818,

Edwards Papers. Hatcher further discusses the

chaotic banking situation in the

Reserve, and Ohio's attempts to reform it in the 1840s, in

Chapter 11.

Land in the Old Northwest 131

Edwards also became increasingly

impatient with Tracy's inability to

transmit to him the money that he did

collect and hold for him. In a letter

to Tracy dated June 5, 1818, Edwards

wrote that his agent owed him about

one thousand dollars (although this

figure was too high because he failed

to subtract the tax payments that Tracy

made for him). Edwards claimed

that since he had hired Tracy, he had actually

received only five hundred

dollars from him, and this all came in a

single remittance. The method by

which Tracy planned to make remittances

was to entrust the cash to a trav-

eler returning to the East. Thus, in

early 1818, Tracy had sent the five hun-

dred dollars with a reputable man to his

wife's father for him to deposit

in Hartford, into an account subject to

Edwards' order.46 This route was

obviously inefficient, confusing, and

subject to the risks of finding a trust-

worthy courier, and then praying that he

did not die or fall victim to rob-

bery on the long road back to

Connecticut. It also entailed the expense of

paying the carrier, so it could only be

done economically with large sums

of money.

Edwards formulated another method which,

although promising, ulti-

mately proved unsuccessful because the

status of currency in the West was

so confused. In 1818, Edwards instructed

Tracy to deposit his remittances

in an account in the United States

Branch Bank at Pittsburgh under

Edwards' name. Tracy would then mail the

deposit certificate to Edwards,

who could then withdraw the money from

the United States Bank at Mid-

dletown, Connecticut47 (as

could easily be done today). Unfortunately,

Tracy claimed to have attempted this

method, only to be spurned by the

Pittsburgh bank, which would not accept

the bills that he wanted to de-

posit: "none of the western bills

except the old Pittsburgh Bank bills were

received at the branch bank in that

place," he wrote. Tracy further stated

that he had also tried to buy a

cashier's check from the same bank, but the

bank would accept only "premium

notes" of the branch banks for payment.

This was impossible, he said, because

those bills were simply not avail-

able in the Western Reserve.48

Another of Tracy's responsibilities was

to pay the land taxes on

Edwards' unsold holdings. He generally

paid the taxes out of the money

that he collected from the settlers'

installments, and he seldom reported

much difficulty with raising at least

this much money out of the these pay-

ments. He did report, however, that the

property tax rate rose quickly from

year to year, increasing the burden on

land agents, who had to collect more

46. Tracy to Edwards, 2 February 1818,

Edwards Papers.

47. These instructions were detailed in

a letter from Edwards to Tracy, 5 June 1818, Ed-

wards Papers.

48. Tracy to Edwards, 8 October 1818,

Edwards Papers.

132 OHIO HISTORY

money from the settlers every year just

to pay the taxes. Consequently, the

agents, in turn, put more pressure on

the settlers to come up with the funds,

and the owner, Edwards in this case, had

to advance the money to the agent

if his payment collections came up

short. In 1814, Tracy reported that land

was taxed at one dollar per acre (almost

a third of the purchase price),

which amounted to an increase of about

50 percent over the previous year.

In those two years, Tracy collected one

hundred forty dollars from settlers,

which amounted to exactly six dollars

more than the total tax payments

for the same time period. Taxes

continued to increase in the next two years,

and for 1815, Tracy paid over one

hundred forty-six dollars. In the six years

from 1812 to 1817, he paid a total of

over six hundred dollars in taxes on

Edwards' land.49

Speculators and agents were not the only

ones inconvenienced by the

scarcity of money; it was a problem and

a fear for settlers, too. Tracy

pointed out the particular problems that

settlers encountered daily con-

cerning the circulation of money.

Settlers suffered from the difficulty of

obtaining Eastern currency, because

unlike Western paper, Eastern bills

were valid and redeemable at many banks

because they were backed by

specie. He commented on the

"confusion the banking system has produced

in this country. Our banks have issued

no paper for a long time on account

of the United States Banks and are

collecting in their dues which has almost

stopped the circulating medium."

Unfortunately, very few legitimate

bills existed in Ohio; many were drawn

upon one or another particular lo-

cal bank and not redeemable at any other

banks, including the United States

Bank. Tracy expressed the view of many

Western settlers when he said that

he hoped that "banks will be so

regulated that money will be put in cir-

culation in such a way as may be depended

on in future."50 Another prob-

lem that he reported to Pierpont Edwards

was counterfeiting. With so many

different kinds of currency in

circulation, it is not surprising that some in-

dividuals took advantage of the

situation to introduce bogus money and

"spurious bills" into the

system. Tracy recorded the case of a "bandilla of

counterfeiting, unprincipled men from

the older states of the union" per-

petrating their "nefarious

schemes," wreaking havoc with the state of

paper money in the Reserve.51

Settlers were obviously frustrated by

high prices, lack of currency, and

unavailable goods. For instance, Tracy

reported in 1815 that a number of

old settlers in Mesopotamia occasionally

ransacked some of Edwards' un-

49. The information about tax collection

and local tax rates from 1812 to 1817

is taken

from figures that Tracy submitted to

Edwards in letters (from the Edwards Papers) dated 7

May 1814, 16 September 1814, 26 February

1816, and 8 October 1818.

50. Quotations drawn from Tracy to

Edwards, 8 October 1818. Edwards Papers.

51. Tracy to Edwards, 24 November 1818,

Edwards Papers.

Land in the Old Northwest 133

sold lands for the timber and sugar

trees there.52 In that letter, he recounted

an incident where a prospective buyer

refused to buy a piece of land be-

cause two settlers had been drilling

one-inch holes in some two hundred

sugar trees, devaluing the land in the

process. Such incidents revealed that

in the absence of a police presence,

private property in the Reserve was

not always secure. Apparently, the

settlers also badly damaged the trees

because they could not even obtain

proper augers in the Reserve. In a fur-

ther testimony to the bleak isolation of

the Reserve, Tracy wrote in 1818

that "the scarcity of money has

roused the people to a more vigilant in-

dustry." The settlers were hardly

rewarded for their vigor, however, be-

cause at the end of a "very

productive season," a group of settlers were

unable to sell their vast numbers of

excess apples and, to avoid wasting

them, had to make about a hundred

barrels of cider.53

Speculators and agents tried to attract

a particular set of settlers to their

land, but they were often so desperate

to sell their land that they did not

have a choice about who came. Young

families were desirable in the West

because they could have children and

increase the population. Hard-

working, honest farmers would make the

settlement more appealing to fu-

ture buyers and raise the value and

profitability of the land for the sell-

ers. Skilled workers could provide

services for settlers. Emigrants from

New England might relay a positive

report on the area to friends back

home. Towns competed with each other to

attract such settlers. On the oth-

er hand, if an area had a reputation for

crime or settlers who lacked in-

tegrity, then settlement could be

retarded. Tracy was careful to note to

Edwards when skilled laborers or

professionals, such as physicians, set-

tled on the land. He also was sure to

tell his employer that the settlers he

had brought in were of high quality. He

described some as "young and in-

dustrious," pointed out where and

when families or groups of friends had

moved in, and commented on the prospects

of "more wealthy" people emi-

grating to Ohio.

Honest and wealthy people also carried

with them the obvious advan-

tage of being more likely and able to

pay their debts when they came due.

Tracy described many of the first

settlers as "unruly," a group that only

gradually gave way to the more

"desirable" settlers over time. He often

commented on their scandalous behavior.

Many were prone to trespass on

unsold lands; for instance, it was a

crowd of "old settlers" who mutilated

Edwards' sugar trees. These people may

have been the most poor, or they

52. Tracy to Edwards, 17 June 1815,

Edwards Papers. The perpetrators were arrested and

tried before the Supreme Court in Warren

in September, 1816, but Tracy neglects to disclose

their fates in subsequent letters.

53. Tracy to Edwards, 8 October 1818,

Edwards papers.

134 OHIO HISTORY

may have been the most hardened by the

difficult conditions. In cases

where purchasers were failing to pay

punctually, Edwards was clearly par-

tial to contractors who seemed

"industrious and honest," and "in a fair way

to do well;" he allowed such

settlers more freedom in making their pay-

ments. "I do not wish you to be

severe with the debtors, especially where

they appear to be industrious and are

making improvements," he told

Tracy's successor, George Swift.54 But

he was also quite willing to void

contracts when other settlers were

unable to make their payments on time;

he sometimes even instructed his agents

to initiate law suits to eject such

settlers from their land when they

became too delinquent.

Despite Seth Tracy's recital of the

difficulties he faced, Edwards was

unimpressed by his efforts and results

in selling land. He denounced him

for failing to sell a single lot during

the first two years of his tenure and

accused him of withholding remittances

from him. Moreover, he was dis-

pleased with the generous credit terms

and low prices that Tracy gave to

new settlers, frustrated by his poor

performance in collecting payments

when they came due, and accused him of

creating fraudulent contracts,

keeping poor records, and pretending to

have sent him letters outlining his

land sales progress in 1819--letters

which Tracy claimed were lost in the

mail. Consequently, Edwards revoked Tracy's

powers of attorney and fired

him in 1819.

In June of that year, Edwards sent

Robert Fairchild out to the Reserve

to settle his accounts with Tracy and

relieve him of his duties. "His ac-

counts were in perfect chaos,"

reported Fairchild. After spending three

days and three nights reorganizing

Tracy's records, he found that Tracy

owed Edwards over three thousand six

hundred dollars; Tracy had thought

that he owed less than one thousand.55

Tracy paid a thousand dollars im-

mediately, and was forced to mortgage

his 300-acre estate to finance the

remainder of his debt. But in 1822, a

Steubenville attorney named Collier,

acting for Edwards, took control of

Tracy's land and auctioned it for about

twenty-five hundred dollars.

Although Edwards rightfully did not

trust him, Tracy's efforts to pro-

mote the settlement of the Reserve and

to improve its habitability were

significant. For instance, upon Tracy's

initiative, Edwards paid for the

erection of a new saw mill in the center

of the town of Mesopotamia. To

further the settlement of the area,

Tracy signed contracts with young men

and families under extremely generous

terms, even though Edwards re-

buked him for doing so. And by his own

count in 1819, thirty-three fam-

ilies had settled in the town since

1816, yielding a population increase of

54. Edwards to George Swift, 14

September 1819, Edwards Papers.

55. Robert Fairchild to Edwards, 29 June

1819, Edwards papers.

Land in the Old Northwest 135

200 percent.56 Furthermore,

Pierpont Edwards' lack of knowledge about

his land persisted in spite of Tracy's

repeated attempts to convince him

to visit him in Ohio, a meeting which he

claimed would have been "of great

consequence to your business in this

place as there is [sic] many things

which are difficult to explain by letter

communications."57

After firing Tracy, Edwards hired George

Swift of New Haven to man-

age his land. Swift served until Edwards

died in 1826. After the Tracy de-

bacle, Edwards demanded a great deal

from Swift, and through him he

made a greater effort to assess the

state of his settlers and his land. In his

first instructions to Swift in 1819, he

directed him to "go to Mesopotamia

town, and for each person who owes me,

learn all you can of each man's

situation, his character as respects

sobriety and industry and the man-

agement of his farming and what

improvements he is making. Note down

at the time all you learn concerning

each man and furnish me with a copy

of all you think it will be useful for

me to know."58 Swift, following or-

ders, kept a careful account of all his

business proceedings and accounts

and relayed them regularly to Edwards.

Like Tracy, he mentioned that "the

difficulty of collecting debts and

procuring money that has for some time

past existed in this state still exists

in a considerable [condition]."59

However, in 1823, Swift reported that

agents and settlers had begun to uti-

lize a new plan that helped settlers

finance their purchase. "I have had fre-

quent applications from persons to

purchase," Swift wrote. "They wish to

have permission to go on to the land,

some for a year and some for two

years, and agree that at the expiration

of that time they will ... pay one

quarter of the price and the remainder

in three equal annual payments or

quit the land."60 Settlers

used the interim between settlement and payment

to establish their house and farm and

grow a year or two of crops to pay

for their land. He went on to report

that Edwards' neighbor and friend,

Simon Perkins, had sold a considerable

amount on land in this manner. Pre-

emption did not become a legal right on

surveyed public lands until 1841,

although settlers had argued for it at

least since the 1820s.61

56. Tracy to Edwards, 11 January 1819,

Edwards Papers. The population growth may have

had very little to do with Tracy's

efforts, because migration to the Reserve as a whole ac-

celerated after the end of the War of

1812 and the cold New England summer of 1816. See

Hatcher, 70-74.

57. Tracy to Edwards, 15 May 1815,

Edwards Papers.

58. Edwards to Swift, 14 September 1819,

Edwards Papers.

59. Swift to Edwards, 30 December 1821,

Edwards Papers.

60. Swift to Edwards, 2 January 1823,

Edwards Papers.

61. The struggle for the right of

preemption on all surveyed lands was long and sometimes

violent. Troops were occasionally called

out to evict people who settled on public land be-

fore it was auctioned, and settlers

organized claim associations to intimidate prospective

speculators. See P.W. Gates, "Land

Policy, 1780-1896," in The Reader's Encyclopedia of

the American West, 638-39.

136 OHIO HISTORY

Although Edwards was typical of many

Easterners who invested in land

in the West, other speculators seem to

have displayed more concern for

their affairs in Ohio. Shortly after

inheriting his father's New Connecti-

cut lands, Henry Leavitt Ellsworth

trekked out to the Reserve in 1811 to

investigate his agent's suspect

behavior. Ellsworth recorded his obser-

vations in a journal. His comments reveal

him to be more astute than Ed-

wards and more interested in his

investment. He noted the terrain of the

tract, and even favorably compared its

drainage and soil to that of the near-

by Holland Purchase. He also observed

that many areas of the Reserve

lacked roads, and travelers often had to

rely on marked trees and a com-

pass to find their way.62

Ellsworth's comments concerning the

inhabitants of the Reserve show

how much he learned about life on the

Reserve. He noted the haphazard

pattern of settlement--many of the towns

"were quite settled, though

there are yet many townships without a

single inhabitant." The destitution

of many of the settlers particularly

impressed him. On several occasions,

he sat for a meal or slept a night in a

settler's "small and scantily contrived"

shack. Once, he complained bitterly that

he had never seen "so much dirt

and filth in any human habitation"

as in the hut where he was spending the

night. Filthy and nearly inedible food,

cramped living conditions, and flea-

infested straw beds were constants among

the various log huts that

Ellsworth stayed in during his

month-long stay in the Western Reserve.

Pierpont Edwards' difficulties

epitomized a critical aspect of the set-

tlement of the American West: the fact

that the world he lived in was great-

ly different from the one that his

business was conducted in. Edwards was

an established Connecticut lawyer and

politician who could not compre-

hend the intricacies involved in typical

problems of settlement. He did not

understand the hardships of obtaining

legitimate currency, the difficulty

of clearing and improving land without

money, and the scarcity of com-

modities that drove people to steal

goods such as timber and sugar from

someone else's land. Every day, the

Westem settler faced an unstable, un-

certain future--a situation which

Edwards had no conception of.

But the position of the speculator was

in flux too. Historians have of-

ten judged the speculator for his

actions and how they affected trends in

Western settlement and development, as

if his activities and objectives

were a constant in the equation of

Western settlement. In the first half of

62. Henry Leavitt Ellsworth, A Tour

to New Connecticut in 1811, ed. Phillip R. Shriver

(Cleveland, 1985), 64. This journal

contains much more than a description of the Western

Reserve; the journal is an insightful

commentary on the people, the land, and the journey

through the Reserve and western New York

and Pennsylvania. The information here and the

following excerpts are taken from pages

56-74 of his journal, the major part that deals with

Ellsworth's inspection of the Reserve.

Land in the Old Northwest 137

the twentieth century, land historians

Benjamin H. Hibbard and Paul W.

Gates led an attack on the land

speculator. Gates criticized speculators for

driving up the price of land and

withholding the best lands from market,

claiming that their policies forced

settlement to proceed sporadically and

caused high rates of farm tenancy among

settlers (instead of outright own-

ership). However, since the 1940s,

revisionist historians have promoted

a different view, one more favorable to

the speculator. Roy M. Robbins

emphasized that speculators

"furnished capital necessary for building up

the new country. They actually

contributed heavily to settlement by

building up towns." Ray Allen

Billington recognized the role of the land

speculator as the middleman between the

settlers and the government. And

Bruno Fritzsche argued that "the

land speculator rather than the stereo-

typed pioneer may well be regarded as

the symbol of what is commonly

called 'Manifest Destiny.'"63 However,

these historians tended to neglect

the speculator's ideals and his ideas

and assumed that he was in control

of his situation, when, as Pierpont

Edwards proved, he often was not. Like

settlers, speculators shaped and were

shaped by the conditions in the West.

Edwards' obstinacy retarded settlement

on his land, but at the same time,

he was angry and frustrated that his

investment was not yielding a return;

his later policies reflected that

tension. Far from engrossing the best lands,

Edwards simply overvalued his land, and

in so doing, he hampered his

profit-making capacity.