Ohio History Journal

|

|

|

WILLIAM SANDERS SCARBOROUGH |

|

EARLY LIFE AND YEARS AT WILBERFORCE by FRANCIS P. WEISENBURGER The most renowned Negroes in American history have generally been men of vigorous action who in various ways have given spirited leadership to their race and to their country. Such persons include Frederick Douglass, John M. Langston, Booker T. Washington, and William E. B. Du Bois. Other less aggressive individuals, such as Richard Theodore Greener,1 the first Negro graduate of Harvard University and a lawyer of note, and William Sanders Scarborough are not so well known, yet have played an important part in Negro contributions to American life.2 The latter, noted philologist and college president, is the subject of this article.3 He was born in Macon, Georgia, February 16, 1852.4 His father, Jeremiah, born near Augusta, Georgia, about 1822, had been freed by his master some years before the NOTES ARE ON PAGES 287-289 |

|

204 OHIO HISTORY son's birth.5 The father, said to have been the great-grandson of an African chief, had in his own makeup a strain of Anglo-Saxon blood. He was short of stature, of stocky build, with brown skin, rounded pleasant face, high forehead, kindly observant eyes, and dignified carriage. Scarborough's mother, Frances Gwynn, was a slave of mixed blood. One of her grandfathers was a Spaniard and the other a full-blooded Indian of Muskhogean stock, apparently of the Yamacraws, a tribe friendly to the whites and living along the lower Savannah River. The mother was born about 1829 in Savannah, Georgia, to Henry and Louisa Gwynn. Her Indian ancestry was apparent in her more than ordinary height, high cheek bones, reddish brown complexion, and determined will. Of a smiling disposition, she assisted in bringing up several children outside of her own immediate family. Both of these parents lived in Savannah in their early years, but the mother went to Macon when about twenty years of age, and there the young people were married. The young husband endeavored to secure his wife's freedom but was unsuccessful in the effort, hence the son took his mother's status, as the law required. Her servitude, however, was only nominal, for she was allowed to spend her time as she pleased and was even paid a small wage for her work. Accordingly, after her marriage she lived in her own home and was able to give careful attention to her family, which never felt the harsh, restrictive features of the slave system. Three children were born to the family, but the older boy, John Henry, died in his fourth year and a younger sister, Mary Louisa, in her second year. Both parents, even amidst the restrictions of antebellum days, were able to learn to read and write. In the lower area of Georgia some private schools and much clandestine teaching had provided for instruction which would have been suppressed in many other parts of the South. The father was able to proceed with his education beyond the elementary level. The mother and father thus spurred the son's educational interests. The mother's half-brother, John Hall, whose appearance indicated his Indian blood, also had a great This article is based in large part of Scarborough's incomplete, unpublished lie stor pre- pared by his widow, Mrs. Sarah C. B. Scarborough, Miss Bernice Sanders, and Mr. William F. Savoy. Their mannscrpt in turn is based in large part of Scarborough's own unpublised autobiography, and all references to it are to their excerpts from it. The notes are th wok of the author of this sketch, who has examined approximately 936 pieces in the Scarborug Papers at the Carnegie Library, Wilberforce University, Wilberforce, Ohio. For curtesies asso- ciated with the use of these materials, thanks are due to Professor Paul M. McStallworth of Central State College and to Wilberforce University. The author also wishes particularly to acknowledge the kindness of Mr. T. K. Gibson, Sr., chairman of the board of directors of the Supreme Life Insurance Company of America, Chicago, who made available to him the manuscript upon which this article is based and who encouraged the researches that were necessary to produce it. who made available to him the manuscript upon which this article is based and wh encouraged the researches that were necessary to produce it. |

|

|

WILLIAM SANDERS SCARBOROUGH 205

influence on young Scarborough, helping

him not only with his bookish

education, but, also as a master

carpenter, with training in that craft. To

aid in this endeavor, Hall purchased a

set of tools for the lad.

The father had early entered the employ

of the Central Railroad of Georgia

and came to have a responsible position,

instructing new employees--white

and Negro--in their duties, and often

serving as conductor of excursion

trains.6 He was of a retiring

disposition but enjoyed the companionship of

a few close friends. He had firm

religious and moral convictions from which

he refused to swerve. While he made

enemies, he was greatly revered by

his friends, and young people sought his

advice and aid. He had joined the

Methodist Episcopal Church in his early

years but later affiliated with the

African Methodist Episcopal Church when

a congregation was established in

Macon after the close of the Civil War.

A strict and loyal churchman, he

seemingly would rather have missed a

meal than a church service, and he

earnestly sought to keep the

congregation from difficulties of any kind. He

was rather indulgent toward the son,

while the mother insisted on obedience,

good behavior, and good manners. As an

only child the boy had to help with

household chores, even with the sweeping

and dishwashing. As this work

sometimes kept him from playing with his

friends, they often called him

"Miss Sallie."

The mother had been nominally the slave

of Colonel William de Graffen-

reid, an aristocratic gentleman, able

lawyer, and influential churchman, who

had most humane views regarding the

Negro and was thoroughly liked by

all people of color who knew him. He

enabled Scarborough's parents to

have (on Cotton Avenue, Macon) a home

for themselves in which they could

rear their children. Later he provided

all the books for young Scarborough's

college education.

Another helpful individual was J. C.

Thomas, an intense southerner, who

usually opposed any progress for the

Negro, but somehow took a remarkable

interest in Scarborough, building on the

parents' efforts by teaching him to

read and write.7 He gave

private lessons to the lad, in spite of the law which

provided fine and imprisonment for

giving such instruction.8 It would seem

that this tutelage was known to people

of both races, but De Graffenreid's

influence, the father's trusted position

with the railroad company, and the

boy's popularity appear to have

restrained criticism. Later some colored

friends gave him further instruction,

which was made easier by the fact

that the family had a home of their own.

Thus as a boy he was able to write

"permits" for Negro men to

visit their families, justifying the fraud on

basic humanitarian grounds.

Even as a boy of five he carried the

dinner pail to his father in the

206 OHIO HISTORY

railroad yards two miles away, and once

became temporarily lost because

of a storm. His father would sometimes

let him ride in the cab with him on

an excursion train.

Before the boy was eight he had mastered

"Webster's Blue-backed

Speller," and he studied

arithmetic, geography, and history under a free

Negro family in the neighborhood. He

loved to hunt, fish, swim, roam the

fields and woods, and, in general, take

care of himself.

Most of his playmates were Irish boys of

the neighborhood, some of

whom would defend him against larger

boys and annoying outsiders. Boyish

fights were mostly with whites of the

"cracker" class who resented any

advancement of Negro young people.

As he and his friends made youthful

excursions into the pine woods near

Macon, they would often sit among the

branches, talking by the hour. On one

occasion a lad told Scarborough that a

terrible war was on its way. The

latter rushed home, and his parents then

tried to explain the situation to him.

After the war began, Scarborough's

father decided that the lad, while

continuing his studies privately, should

learn another trade, that of shoe-

making, in addition to his training in

carpentry. So the boy was apprenticed

to a friend of his father, a Mr. Gibson,

a skilled workman. Each morning

the boy was supposed to clean up the

shop, get things in readiness for the

day's work, and then read the news

secretly to the workmen. During this

period, which lasted two years, he

learned to make his own shoes and do

work for others, and he sought to read

every book on which he could lay his

hands. Incentive was stimulated as hope

arose that successes of Union arms

would lead to a greatly improved

situation for the Negroes. Food of course

was high in price, and Negroes, unable

to secure sugar, tea, and coffee, used

roasted corn or sweet potatoes as a

substitute for coffee and used sugar cane

for sweetening. The Scarborough family

moved several times, going from the

east to the west side of the Ocmulgee

River in an effort to better their

condition. At last they moved back to

East Macon, where the father's ability

at carpentry enabled him to build a

home, where he lived the rest of his

life on land given him by Mr. Thomas.

During the war years Negro boys in the

Macon area were often threatened

by white ruffians or seized on the

streets and required to serve in the hospitals

where Confederate soldiers lay sick and

dying. Young Scarborough had

several narrow escapes from violence or

compulsion. His father, however,

not only went on the streets at will but

visited the nearby camp to see rifle-

men drill. His important service on the

railroad insured his exemption from

less crucial activity.9

As the war progressed, the family

experienced alternate depression and

WILLIAM SANDERS SCARBOROUGH 207

elation, and hoped that if the South

should win, a sum set aside by the

railroad for the father's welfare could

be used to enable him to go North,

and that friends might assist the mother

to accompany him.

In the summer of 1864 Sherman began the

siege of Atlanta.10 The

Scarboroughs in Macon could hear the

gunfire seventy-five miles away. The

father had to labor on the railroad to

help the cause which meant continued

subjection for his people, but it

insured him against being forced on numerous

occasions to perform more dangerous

duties. During the summer, Con-

federate soldiers, entrenched near the

Scarborough home, compelled people

in the neighborhood to bring them water.

On one occasion young Scar-

borough, without compunction, carried

water to them in a dirty pail. As the

situation became more serious for the

Confederates, those in Macon held

frantic prayer meetings on the town

"green." When a Union attack failed,

and General George Stoneman and some of

his cavalry staff passed the

Scarborough home as Confederate

prisoners, the lad could not restrain

his tears.

Long before, of course, word had come of

the Emancipation Proclamation

of January 1863. In September 1864, with

the fall of Atlanta to the Union,

hopes of the family rose in expectation,

but Lincoln's death in April 1865

was a cruel blow, followed by anxious

forebodings. A few days later Macon

again faced alarm as the Union

commander, General James H. Wilson,

once again approached the city.11 In

East Macon the family was living

directly in front of the Confederate

earthworks but did not move. Shells

were flying overhead, and everything was

in a state of turmoil. Finally,

Confederate soldiers rode agitatedly

into the city, giving the alarm that

Union forces were entering. As Union

forces did come, the family slept

little that night. Later, the

Scarboroughs learned that General Howell Cobb

had surrendered the city and that the

bridge over the river had been saved

from destruction only by the prompt

arrival of the vanguard of Union troops.

That the Union soldiers might not get

possession of all of the supplies

provided for Confederate troops, the

Macon authorities allowed the people

to take what they wished, and they

poured quantities of liquor into the

streets. As the Union forces broke into

the rest of the Confederate com-

missary stores, they permitted Negroes

to take what northern soldiers would

not use. The Scarboroughs availed

themselves of many needed articles, and

the lad obtained an abundant supply of

pen points, pencils, envelopes,

and paper.

Soon General Wilson detailed officers to

announce to the people the

effective emancipation of the former

slaves. At a packed meeting in the

Presbyterian church, young Scarborough

sat perched in an open window as

208 OHIO HISTORY

members of his race rejoiced with cries

and tears that their day of liberation

had come. The very next day in the Macon

neighborhood almost every Negro

family which had served a white master

moved out to seek a new life regard-

less of the trying adjustments.12

Macon, like some other southern towns,

experienced a business revival

in 1865-66.13 Soon the youth was hired

to work in a bookstore owned by

Mr. J. Burke, an ardent southerner, a

sturdy Methodist, and a man of

generous human qualities. He allowed the

lad to read widely and even

assisted teachers from the North who

were arriving to advance Negro edu-

cation. A short time later the store was

burned, but subsequently Burke

established another one.

The lad had earned his first greenback

by selling, along with other white

and Negro newsboys, the Macon

Telegraph, the city's chief paper. The boys

had permission to pass through the lines

to sell papers to the soldiers.

Earlier, Scarborough had sold

strawberries for a gardener at one hundred

dollars in Confederate script. Now it

had lost its value, and United States

money was insisted upon. The lad made

considerable profit through his

newspaper sales, the father carefully

keeping it for him in a fine walnut box

with lock and key that had been

fashioned by his carpenter uncle. Union

soldiers were very kind to the lad, as

they often questioned him as to his

life ambitions, which already had been

sharpened by knowledge of the

achievements of Frederick Douglass and

John M. Langston.14

In May, Jefferson Davis was brought as a

prisoner under special guard to

Macon.15 The boy, having

climbed a tree in front of a hotel on Mulberry

Street, was only a few feet away as the

former Confederate president was

taken into the establishment. Boyishly

he exulted because of the turn of

events, but he was disappointed at the

impression he received of the per-

sonality of the leader of the Lost

Cause.16

As military rule under Union authority

was established, young Scar-

borough witnessed the arrival of Negro

troops to take the place of white

contingents in Macon. He also saw the

resentment of southern people,

who nursed a poorly repressed feeling of

disdain. Many times he noticed

white people going into the street

gutters and mud, often to the detriment

of their attire, rather than walk under

the Union flags flying above the

sidewalks.17

Soon, the Freedman's Bureau began to

operate in Macon,18 and after a

time colored postmasters were appointed,

Henry McNeil Turner, becoming

city postmaster and John G. Mitchell,

assistant postmaster. Young Scar-

borough had first met Turner when the

latter came to attend the first con-

ference of the African Methodist

Episcopal Church in Macon.19 Mitchell,

WILLIAM SANDERS SCARBOROUGH 209

an early graduate of Oberlin College

(1858), was one with whom Scar-

borough was later to be associated very

closely in his work in the North

(at Wilberforce). Another prominent

Negro whom Scarborough met during

this period was the previously mentioned

John M. Langston, who had come

to Macon to address a public meeting.

From him the youth made his first

purchase of a significant book, one on

the life and service of Abraham

Lincoln. In the meantime, Scarborough

found employment at odd times

as a clerk in the Freedman's Bureau

office in Macon.

Now, education could be pursued in a way

which was freed from the

strain of the surreptitious, as the

youth entered a school for Negro children,

opened in an upper room of the

Triangular Block in Macon. A small tuition

fee was paid by each of about fifty

students. The work was basically

elementary, but Scarborough had opportunity

to refresh his knowledge of

the work previously done and to

strengthen the weak aspects of it. He did

not remain long in this school, for the

American Missionary Association

soon opened a school which first met in

any available quarters. One of the

youth's teachers, Mrs. Sarah Ball, a

schoolmistress from Townsend Harbor,

Massachusetts, later recalled how

classes had met in the old slave quarters

of her home place near Spring Garden; in

the old stable; in the old Methodist

church; in a former dwelling; in a

chapel; and finally, in a new building.20

She remembered Scarborough "as a

large schoolboy with book ever in

hand, studious, obedient, and

attentive." Scarborough developed enduring

admiration for those men and women who

had left "comfort and ease" to

endure "ostracism, insult and

calumny" from bitter southerners.21

The new building was Lewis High School,

built by the American Mission-

ary Association, aided by the Freedman's

Bureau. It was named for General

John R. Lewis, who, as a bureau officer,

actively promoted its interests.22

It was burned, as were the adjacent

chapel and teachers' home, in December

1876, in the midst of the bitterly

disputed Hayes-Tilden election. Apparently

the fire was of incendiary origin, for

the school had many enemies. Later

it was rebuilt and renamed Ballard

School. Among the teachers were John

R. Rockwell of Norwich, Connecticut, and

the lady whom he subsequently

married. Rockwell, a Yale man of

independent means, was forceful,

accurate, earnest, and a real gentleman,

beloved by his pupils. He estab-

lished regular military drill, and

Scarborough, before the end of his three

years of schooling there, had been made

an officer in the cadet corps. During

these years the youth was absent only

three times from classes, when he

was detained at home to help build the

house.

Among the subjects studied were Latin,

algebra, and geometry. Scar-

borough's advisor was a Dartmouth man,

Samuel G. Haley, a person of

|

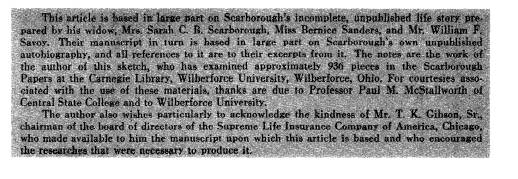

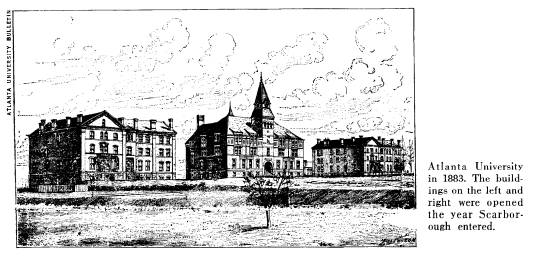

210 OHIO HISTORY excellent character who had graduated from college in 1860.23 During vacation periods Scarborough gave private lessons to grown men and women who were eager to learn. During one vacation he worked in a brickyard, and during another he won a prize in an essay contest, receiving considerable acclaim in southern newspapers. Influenced by a Yale man and by a religious tract, he considered prepara- tion for that college. The tract helped him crystallize his religious views. He joined his mother's church, the Presbyterian, but later affiliated with his father's denomination, the African Methodist Episcopal Church.24 The youth remained in Lewis High School until 1869, when both parents decided that he needed wider opportunities, and in the fall he entered Atlanta University, another American Missionary Association institution, where he spent two years. There he completed the study of nine books of Legendre's Geometry, two years of Latin, and one year of Greek, civil govern- ment, advanced arithmetic, history, and algebra, along with some English prose and drawing.25 In his later years he still preserved a record card (signed by President Edmund Asa Ware, whom he looked upon as his ideal), with a grade of 98 in Greek, as well as in Latin and in mathematics, and 100 in deportment.26 Here his chief mentor was Professor Thomas Chase, a Dartmouth graduate, under whom he continued Greek studies and from whom (as well as from President Ware) he secured a zest for achievement. Dormitory life there was permeated with essentially "the atmosphere of a Christian home," and students looked forward to the inspiration of the Sunday church services. On week days the youth spent two or more hours |

|

|

WILLIAM SANDERS SCARBOROUGH 211

of his spare time working with other

students in leveling the breastworks

and fortifications which remained on the

campus from the wartime activities

of the Confederates.27

While at Atlanta University he took

examinations with a state legislative

committee as visitors. He and others

showed such proficiency in various

branches that the committee frankly

admitted that the Negro could be trained

in such higher studies as Latin, Greek,

algebra, and geometry. During one

vacation period the young man taught at

Cuthbert, Georgia. The Franco-

Prussian War was in progress, and each

afternoon after school he would

go to a friend's grocery store to spend

an hour or more reading to those

who wanted to hear the latest war news.

He was the first graduate of

Atlanta University. At the time there

were no others and no graduation

exercises.28

At once he prepared to enter a northern

college. He had planned to enter

Yale to become a lawyer, but a turn of

events led him to Oberlin, and for

the first time in his life he left the

South. On the journey at Nashville

another Negro attempted to rob him.

At Oberlin he lived with the family of a

deceased professor, Henry E.

Peck, a leading figure in the activities

of the Underground Railroad and a

participant in the famous

Oberlin-Wellington rescue affair of 1859.29 Peck

had been diplomatic representative of

the United States in Haiti before his

death there in 1867.30 Peck had accumulated

a large library, to which the

young man had access. In this home of

generous sympathies Scarborough

resided for the four years of his

college training.31 The family entertained

noted visitors, including Dr. Richard

Storrs, pastor of the influential Church

of the Pilgrims (Congregational),

Brooklyn, New York; Dr. John Hall,

pastor of the Fifth Avenue Presbyterian

Church, New York City; and Dr.

Leonard Bacon, pastor for a generation

of First Church (Congregational),

New Haven, Connecticut. The indomitable

Charles G. Finney, ex-president

of Oberlin College, was a frequent

caller in the home. Scarborough also

drew inspiration from members of the

Negro community in Oberlin. John

M. Langston, previously mentioned, who

had been arrested for his part in

the Oberlin-Wellington rescue of 1859,

lived opposite the Peck home, and

his son Arthur was an intimate college

friend. Among Scarborough's

college friends were Arthur Langston,

'77; Robert Bagby, '74, later a lawyer;

and Matthew Anderson, '74, who later

attended Princeton Seminary, took

up work at Yale, and subsequently

established a successful industrial school

in Philadelphia under Presbyterian

auspices. Scarborough later recalled

the beginnings of a lifelong friendship

with Mary Church, who later married

Judge Robert H. Terrell.32

212 OHIO HISTORY

The new environment presented a marked

change for him, but he was

admitted to the college without

conditions. Everywhere he met a helpful

spirit, and he was proud to wear the

freshman cap with a blue visor, bearing

the letters "O.C.," and with a

star in the center. He was surprised at the

small number of Negro students, for

expenses were so low that one could

pay all expenses, attend concerts, and

dress neatly on less than $300 a year.

Indeed, the college prospectus indicated

that rooms, completely furnished,

in Council Hall, were free, and that

total expenses ranged from $48 to $73.50

for a twelve-week term in 1874-75.33

His previous preparation had been such

that he was able to assist fellow

students in their difficulties with

Latin, Greek, and mathematics. He en-

deavored to continue at Oberlin his

previously developed systematic habits

of study. After the noonday meal he

spent an hour on the playground, and

somewhat later an hour in the reading

room. Study in his room or a little

manual work followed thereafter. At

night and again in the early morning

he would review his lesson preparations.

The college library was a great aid to

him and he read two or three books

a week. History and biography, including

Prescott's works; the writings of

Emerson and De Quincey; and Tom Brown

at Oxford all brought him

exhilaration and inspiration. There were

some Spanish students in residence,

and he made some progress in the

language with their assistance.

There were monthly

"Rhetoricals" and weekly Thursday "Literary"

gatherings, when all listened to

addresses by faculty members or prominent

visitors. Of the three Greek letter

societies, there being no fraternities or

secret organizations, Alpha Zeta was

that with which Scarborough was

affiliated. Here the students obtained

training in expression and debate, and

Scarborough afterwards recalled clashes

in forensic skill with Theodore

Burton, '72, later congressman and

senator from Ohio.34

He also developed a lasting friendship

with Ernest Ingersoll, who became

a noted naturalist. The Musical Union

helped to promote an interest, which

always remained with him, in vocal and

instrumental music.

He found that socially he was always so

generally accepted that he forgot

differences in color. The students

sometimes attended theaters and other

places of amusement in nearby cities.

Fun at Oberlin included a funeral

ceremony for Thucydides when the

students had concluded their study of

that author. His parents sent him money

regularly, but in his spare time

he added to his resources by sawing wood

for the Peck family.

During a long winter vacation he taught

for a time at Enterprise Academy,

Athens County, Ohio. There a Rev. Mr.

Boles gave leadership to a student

constituency comprised chiefly of

elementary students from West Virginia.

|

WILLIAM SANDERS SCARBOROUGH 213 |

|

|

|

Among those that Scarborough knew at the academy was Olivia Davidson, who became the second wife of Booker T. Washington.35 He also developed a friendship with E. C. Berry of Athens, Ohio, a young man of character and enterprise who opened a livery stable, then a restaurant, and finally a hotel that figured prominently in the life of the community. During his junior year Scarborough's winter vacation was spent in teaching in the country at Brook Place, near Bloomingburg, in the vicinity of Washington C.H., Ohio. What impressed the young man most about Oberlin was its strong religious spirit and the marked strength of character of various prominent personali- ties. Ex-President Charles G. Finney still served as professor of pastoral theology and loved to tell vividly of his early experiences. His sermons, sometimes three hours in length, and his endless prayers were not always appreciated by the student body. President James H. Fairchild was a noted scholar, whom Scarborough considered to be "another grand man who wore Mr. Finney's mantle as Elisha did that of Elijah." Students were welcome visitors in the home of the president and his wife. Among the professors who especially impressed the young man were Charles Henry Churchill, professor of mathematics and natural philosophy; Giles W. Shurtleff, professor of Latin language and literature;36 and the Rev. William H. Ryder, professor of Greek language and literature. Scarborough looked upon Mrs. Adelia A. Johnston, principal of the woman's department, as "a gifted woman who indelibly impressed herself on Oberlin life."37 |

214 OHIO HISTORY

This phase of the young man's life came

to completion with the college

commencement on August 5, 1875, at First

Church, Oberlin. There were

fifty-three who graduated this year,38

but these exercises were for the

thirty-six members of the classical

course, each of whom spoke, Scar-

borough discoursing on "The Sphere

and Influence of Genius."39

Now at twenty-three the young graduate

faced the problem as to how he

might best use his efforts and even his

life to advance the members of his

race. He decided that after four years

of separation from his family he

would first return home, going via New

York City and there taking a steamer

for Savannah. As he left Oberlin for

Cleveland he was approached by two

Roman Catholic priests, who tried to

interest him in going to Rome to

study for the priesthood. He had some

warm Catholic friends at home, and

he considered the proposal at some

length, but at last decided that his

Protestant background was too much a

part of his makeup for him to follow

such a course.

En route to New York he stopped at

Princeton to visit Matthew Anderson,

an Oberlin graduate. Two other Negro

youths, Francis J. Grimke (from

Lincoln University) and Daniel W. Culp

(from Biddle), were then enrolled

at Princeton Seminary.40 A

rumor got around that he planned to enroll at

Princeton University to take graduate

work, and this created some con-

sternation, for no Negro had ever been enrolled

in the college. In New York

friends offered to seek a scholarship

for him at Harvard Divinity School

so he could prepare himself for the

Unitarian ministry, and he wondered

why various people wished him to join

the ranks of the clergy.

In Macon there was a joyful reunion with

his parents. He brought

testimonials, including one from

President Fairchild commending his "high

character, good scholarship, and

successful experience as a teacher." De-

ciding to remain in Macon and engage in

teaching, he sought a position

at Atlanta University, but his old

friend, E. A. Ware, while deploring the

fact, indicated that the "time was

not ripe" as yet for a Negro teacher in

the university, for the trustees would

not agree to such an appointment. Some

friends in Macon called a meeting to

raise funds to compensate him for

teaching in a private school. Then after

a brief period the American

Missionary Association appointed him as

an assistant in Lewis High School.

In the summer of 1876 he went north,

visiting the Centennial Exposition

in Philadelphia and friends in New York

City. The Rev. Mr. Pike, a secre-

tary of the American Missionary

Association, who was engaged in classifying

for publication records and papers

relating to the Mendi Mission in Africa,

endeavored to interest him in going to

Africa to devote himself to the study

WILLIAM SANDERS SCARBOROUGH 215

of the languages and dialects with a

view to the later translation of the

Bible into these tongues. Scarborough

recognized the need for such studies

but decided to return to his work in

Macon.

At the fall elections every effort was

made to intimidate Negroes at the

polls, and it was deemed advisable to

close the school on election day.

Ill feeling stirred up by the contested

Hayes-Tilden election stimulated

much hatred and animosity. Negro

schools, especially those taught by

northern teachers, became the target of

attack, and in December the Lewis

High School was destroyed by fire. Along

with political bitterness an

epidemic of yellow fever raged through

the South during the autumn. Now

the American Missionary Association sent

professors from Atlanta University

to confer with the teachers at Macon

with regard to rebuilding or abandoning

the work there. Rather cramped temporary

accommodations were secured

in the basement of the colored

Presbyterian church, with living quarters in

a room warmed by a stove with the stove

pipe projecting through an opening

made by removing a pane of glass. Two

white teachers from the North

lived in the home of Mrs. John Rockwell

across the street. After the close

of the school year the American

Missionary Association debated whether

to continue the work at Macon or

transfer the white teachers to Fisk Uni-

versity. The former was decided upon,

but privations and overwork made

it necessary for the teachers to remain

in the North for a period, and

Scarborough was forced to find

employment elsewhere.

A new opportunity for him was provided

by two leaders of the African

Methodist Episcopal Church, Bishop

Richard H. Cain, a vigorous Negro

minister in South Carolina, who had been

a member of congress and a

prominent leader during Reconstruction

days,41 and the Rev. J. M. Brown,

who later became a bishop. The

denomination had established a Negro

school known as Payne Institute at

Cokesbury, and Scarborough was put

in charge. Later it was moved to

Columbia, South Carolina, and eventually

became known as Allen University.

The period was one associated with the

political struggle between Wade

Hampton and Governor Daniel H.

Chamberlain and between the white

supremacists and the carpetbaggers for

control of the state. The air was

rife with conflict, so that it was

unsafe for any Negro to take a prominent

part in any aspect of public affairs.42

Following Hayes's inauguration, of

course, support was withdrawn from the

carpetbag governments in the South

and they collapsed. Now, according to

Scarborough, "many politicians who

had professed great love for the race

and had made use of the Negro for

their personal aggrandizement in riches

and power, turned against him."

A Negro, Richard T. Greener, a Harvard

graduate who had been instructing

|

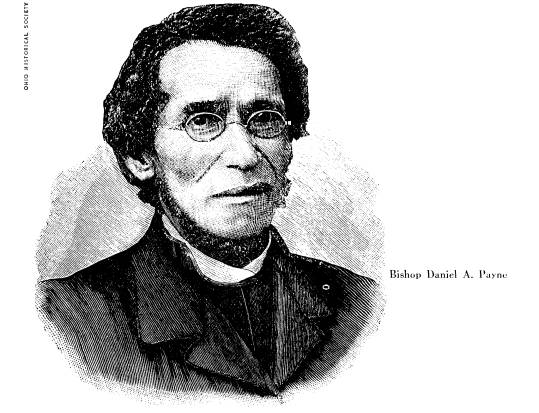

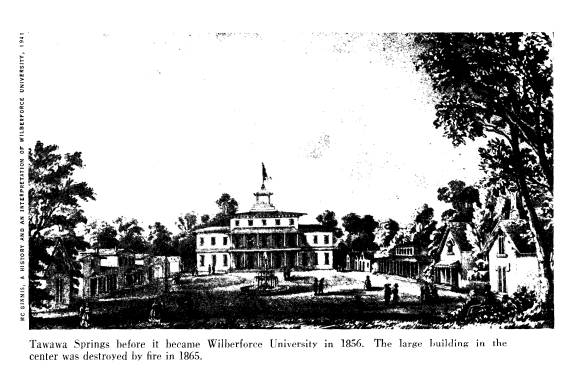

216 OHIO HISTORY both Negro and white students at the University of South Carolina, was forced to give up his professorship and return North.43 Amidst the un- certainty and rumors of growing Ku Klux Klan activities, Scarborough left for Oberlin Theological Seminary, where he began the study of Oriental languages, with an eye to the ministry. As he completed his work,44 a letter was forwarded to him from a school in Ohio, asking about his plans for the future. After sending an immediate reply, he awaited developments while visiting friends in Philadelphia. In the Quaker City Scarborough conferred with Bishop Daniel A. Payne of the African Methodist Episcopal Church. A slightly built man, Payne as a youth had been forced to leave Charleston, South Carolina, because of his progressive ideas regarding the colored people. Continuing his studies at Gettysburg Seminary in Pennsylvania, he had stirred up much interest among Negroes by a series of articles on Negro education. Indefatigable in his efforts for Negro advancement, he had been the leading founder and then the second president of Wilberforce University at Wilberforce, Ohio.45 His successor, Benjamin F. Lee, had written Scarborough, and now Payne informed the latter that he had been chosen professor of Latin and Greek |

|

|

WILLIAM SANDERS SCARBOROUGH 217

at that university. But with

disconcerting frankness Payne voiced his own

belief that Scarborough was too young

for the position. Scarborough later

asserted that he learned not to take

Payne's "plain speech too much to

heart, and to interpret the twinkling

eye and twitching lip that accompanied

his utterances." The young Oberlin

graduate at this time asserted that he

would do his best to fill the place and

would grow older with time. The

bishop, apparently reassured, abandoned

his objection, and thereafter proved

to be a staunch friend and supporter.

Possibly John Mitchell, an Oberlin

graduate and onetime Macon postmaster

who was living at Wilberforce, may

have suggested Scarborough's name.

Wilberforce University had been a

landmark in Negro education. In

Ohio, when public schools were

established after 1821 and especially

beginning in 1825, Negroes were not

expected to attend, and a law of

1829 even forbade their enrollment.46

By a law of 1849 separate Negro

schools were provided in places where

there were twenty or more Negro

students. Where there were fewer colored

children of school age, the law

permitted them to attend the white

schools, if there was no objection.47

As the Negro population of Ohio

increased,48 the African Methodist

Episcopal Church sought to implement

Payne's concern for Negro educa-

tion. The four conferences of the

denomination took steps to establish a

school on the manual training plan which

would also prepare young men

for the ministry. The result was the

securing of land twelve miles from

Columbus, Ohio, and the chartering of a

school known at first as Union

Seminary. From 1847 until 1863 it

operated under two persons who later

attained eminence as Negro leaders, John

M. Brown, subsequently a bishop,

and Frances Ellen Watkins Harper,

destined to become a poet. In the

meantime, the Methodist Episcopal

Church, North, was also stirred to

action, and in 1853 took steps resulting

in the purchase of property known

as Tawawa ("Sweet Water")

Springs, near Xenia. In the midst of the old

Shawnee Indian country, it had been a

fashionable summer resort. The

school, incorporated as a university in

August 1856, was named for William

Wilberforce, the noted English

abolitionist. A white minister, Dr. Richard

Rust, served as president from 1858 to

1863. At first most of the students

were half-breed children of southern

white planters, but the fathers by

1863 could no longer give financial

support, and the school closed. Bishop

Payne, who had been associated with the

enterprise since its inception,

bought the property for $10,000 in

behalf of the African Methodist Episcopal

Church, although at the time he had no

resources for the project but "faith

in God and friends of the race."

Union Seminary was now merged with

the university. Rechartered, it became,

according to Scarborough, "the oldest

|

218 OHIO HISTORY |

|

|

|

Negro school in the country, as well as the first one organized as a race effort." Valiant endeavors led to the debt on the property being practically liquidated by 1865, when fire destroyed the building. A new one, however, was erected. Payne became president and was the guiding spirit until 1876, when he was succeeded by Bishop Benjamin F. Lee, a recent graduate of the theological department.49 Lee wrote to Scarborough expressing gratification at the latter's acceptance of a professorship and indicating that he would expect him to arrive on September 4. The young teacher spent the summer in Philadelphia and New York, improving his preparation for teaching the classics. Arriving on schedule at Wilberforce, he found the upper floor of the one large building of three stories and a basement as yet unfinished. The lone struc- ture served as chapel, recitation hall, dining room, and dormitory for teachers and students. Part of Scarborough's work was to oversee the boys living in the left wing of the building. On the campus, shaded by many old trees, was a row of cottages on each side stretching to a highway, which was reached by footpaths and two primitive stiles. In one cottage the president resided, the row already having been dubbed "Smoky Row" by the students. In the center of the campus |

WILLIAM SANDERS SCARBOROUGH 219

was a well of never-failing water and in

nearby ravines were the "Tawawa

Springs," which were said to have

medicinal qualities derived from iron

and sulfur.

The school was supposedly organized in

four departments. Of the faculty

members, four were Wilberforce

graduates, four were white teachers in

the law department, who lived in Xenia,

and two were white ladies living

at the school. Of the fewer than one

hundred students, some were well

advanced in age. During this period

teachers came from England and

Scotland and from Oberlin and Mount

Holyoke. From the latter came

Mrs. Alice Adams ("Mother

Adams"), whose son Myron later became

president of Atlanta University.

Having undertaken his responsibilities

at Wilberforce, Scarborough sought

to make his class work more effective by

designing cards for parsing and

for verb work in Latin grammar, and he

wrote a textbook, First Lessons in

Greek.50 The head of the firm which published the work was a

trustee of

Adelphi Academy, Brooklyn, New York,

which school led the way in the

adoption of the text.51

During this period Scarborough married a

white woman, Mrs. Sarah C.

Bierce, a graduate of Oswego Normal

School in New York State. The two

had been fellow high school teachers at

Macon, and she was teaching at

Wilberforce at the time of their

marriage. There she served as professor

of natural science (1877-84); professor

of French (1884-87); and principal

of the normal department (1887-1914).

Scarborough later testified, "There-

after I had a faithful, loyal and

untiring comrade, and our interests were

mutually shared."

In 1884 Benjamin F. Lee was made editor

of the African Methodist

denominational paper, the Christian

Recorder, and Wilberforce sought a

new head.52 The very able Dr. John G.

Mitchell was chosen to fill the post,

but circumstances prevented his

acceptance, and the position went to his

brother, Samuel T. Mitchell, then associated

with the Springfield, Ohio,

public school system. Scarborough

considered him to be a "man of ability

and energy." Mitchell was the first

layman elected to the presidency, hence

he was at once ordained to the ministry

to preserve "an inviolable tradition."

Scarborough now considered offers from

other places, but the new presi-

dent and many friends urged him to

remain. He had purchased a few acres

of land and a barn for a horse and

carriage, and he contemplated building

a home. He found his classes and his

student contacts stimulating. He,

moreover, had been promised the

opportunity for literary expression and

additional financial compensation in

helping prepare denominational litera-

ture. These prospects materialized, but

in 1891, after he had been at

220 OHIO HISTORY

Wilberforce for thirteen years of

earnest activity, serious trouble developed.

He later explained that it seemed that

he "had gone too far and too fast

to suit some people." The

difficulties were of long standing and were due

to a clash of personalities and of

educational ideals. Scarborough had

experienced frequent clashes in faculty

meetings with Joseph P. Shorter

of the class of 1871, vice president (1884-92),

and a member of the board

of trustees for over twenty years.

Shorter was brusque, sarcastic, and

somewhat erratic, and was aggressively

combative in faculty discussion.

Scarborough was interested in scholarly

progress, especially in the classics,

while Shorter taught mathematics and

sought to get the faculty to seek state

funds to establish a normal and

industrial department. As a fitting climax

to Shorter's efforts he was made head of

that department in 1892, serving

until his death in 1906.53

Scarborough also clashed with President

Samuel T. Mitchell, who had

been Wilberforce's president since 1884

(and was to serve until 1900),

and who on the whole had harmonious

relations with the faculty. Now, in

1892, the president had difficulty

(arising from personal jealousies) with

Scarborough. After both sides had

presented their case to the board of

trustees, a vote of confidence was given

to Mitchell. Scarborough lost his

position, Horace Talbert being named to

the professorship. The next day,

however, Scarborough was named to a

professorship in a newly established

theological department, separately

organized and governed by its own

board of trustees. It was named Payne

Seminary after Bishop D. A. Payne.54

During his first year in the seminary no

provision was made for regular

salaries, each faculty member being

expected to do what he could to raise

the necessary funds. Scarborough owed

money on his home and could not

collect his back salary from the

university. He later commented: "Had the

movement, taking me from college work,

been an attempt to cripple me at a

critical time, it came near

succeeding." But fortunately his wife's income

remained steady, for her position in the

normal department had come under

state authority.

Scarborough later recalled: "My pen

was my sole dependence. It looked

dark, but friends and creditors gave a

helpful hand, as they realized the

situation with indignation. My wife and

I redoubled our literary efforts."

Magazine work came to them. Bishop

Payne, moreover, put in Mrs. Scar-

borough's hands the task of compiling

from his voluminous diaries and

letters materials for the first volume

of The History of the African Methodist

Episcopal Church and then for his Recollections. Scarborough's

seminary

colleagues were on the whole congenial

and cooperative. The new work,

however, called for the unpleasant task

of begging for money, with frequent

|

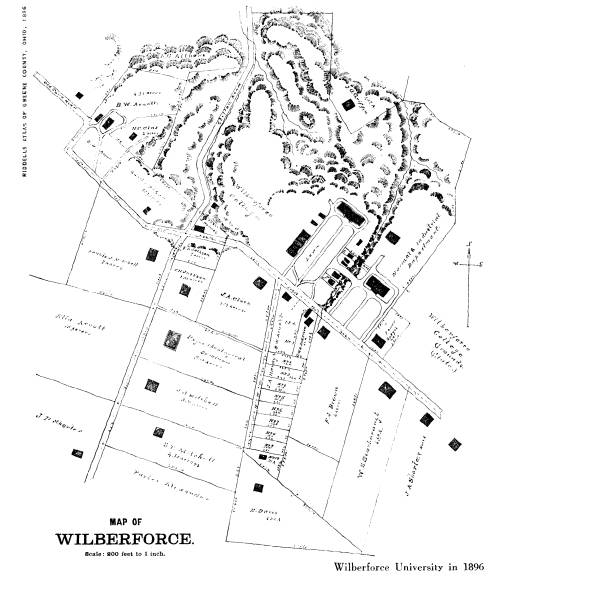

WILLIAM SANDERS SCARBOROUGH 221 absences from home and humiliating experiences when stranded without funds in embarrassing situations. He was deep in debt at the time and had to obtain loans which became a real burden over the years. In 1896 new legislative acts of the state of Ohio placed the state-supported work at Wilberforce under a reorganized board of trustees, with a newly created office of superintendent. The new arrangement was to lead to end- less friction. Scarborough refused to be considered for the superintendency, but gave advice as to appointments to the board and successfully urged the retaining of Mrs. Scarborough as principal of the normal department. |

|

|

222 OHIO HISTORY

In 1897 Scarborough's services at Payne

Seminary came to a close, as he

was appointed to his old professorship

at Wilberforce and was made vice

president of the institution. He later

said that he felt that his years at the

theological school had been years of

spiritual growth, for he had come to

see that, like the Israelites, his own

race had to go through trying experi-

ences. He had learned, he thought, the

wisdom of the philosophy of Samuel

C. Armstrong, founder of Hampton

Institute, that what one cannot change

he must endure.

The death of Bishop Benjamin Arnett, a

close friend, in October 1906

was a severe blow to Scarborough,

especially since plans were underway

for Wilberforce's golden jubilee in

1906-7. The observance, nevertheless,

took place, and during the festivities a

reception was given at the Scar-

borough home for Booker T. Washington.55

Soon a drastic change was to take place

in Scarborough's basic situation.

From 1900 to 1908 Joshua H. Jones had

served as president of Wilber-

force, but growing dissatisfaction with

the administration led to the appoint-

ment of Scarborough, who was to serve

from 1908 to 1920. Since the

financial condition of the university

was precarious, many friends advised

against his acceptance of the

appointment. The welfare of the school,

however, was at stake, and the large

amount of accumulated back pay (with

interest) owed to Scarborough would not

be forthcoming unless the institution

could be placed on a sound financial

basis. He accepted the position and

immediately saddled himself with

personal obligations to meet university

debts and make university repairs.

Quite the antithesis of President Joshua

Jones, Scarborough was "mild-

mannered, dignified, scholarly,

impractical and eccentric. Moreover he

was a layman."56 He

received warm congratulations from William Howard

Taft, Senator Joseph B. Foraker, and

others. Booker T. Washington, during

the previous year, in a national

magazine, had paid tribute to Scarborough,

his "beautiful and well-kept"

home, and his extensive library, associated

with the "refined, studious atmosphere

of a scholar."57

Wilberforce not only lacked funds for

adequate educational services and

necessary expenses but faced suits for

the payment of old debts. The

historian of Wilberforce tells us that

Scarborough lacked outstanding

executive qualities, but his reputation

as a scholar proved a valuable

asset. Scarborough was able to secure

the advice and endorsement of

influential Negro and white friends, and

he traveled extensively in the

East, meeting philanthropic individuals

and boards and delivering addresses.

Thus he became "the best public

relations officer that the school ever had."58

Beginning in 1909, moreover, there had

been a notable increase in financial

WILLIAM SANDERS SCARBOROUGH 223

support from the African Methodist

Episcopal Church conference. Reporting

to the university trustees in June 1911,

Scarborough stated: "The problems

this year have been much the same as

last. Many of the difficulties, however,

that we met in the past year have been

overcome, and I am glad to say

that the future is bright. Through our

efforts in the East many friends have

become interested in our institution and

have promised tentative help....

Our great drawback has been the lack of

advertisement."59

As early as 1908 Scarborough had been

able to interest Andrew Carnegie,

whom he had met at Tuskegee, in

providing help in erecting a badly needed

girls' dormitory. In March 1909 Carnegie

had agreed to give half the

cost if the other half would first be

raised elsewhere. Scarborough met

with major success in this effort. Miss

Hallie Q. Brown of Wilberforce

had gone to a missionary convention in

Scotland, and while in London

had conferred with a former Cincinnati

resident, Miss E. J. Emery, who

wrote for detailed information regarding

Wilberforce and later promised

to give a sum equal to the amount which

she had provided for a building

at Tuskegee Institute. Booker T.

Washington aided with his influence, and

the financial efforts were so successful

that it was decided to build a larger

structure than the $35,000 one

previously contemplated. Costing over

$50,000, the dormitory was named Kezia

Emery Hall after a member of

the family of Miss Emery.60

Presidential responsibilities involved

not only financial matters but efforts

to raise scholastic standards, duties in

connection with commencement

exercises, and activities in the

interest of alumni clubs. At the Wilber-

force commencement of 1909 Scarborough

had delivered the baccalaureate

address, taking a Biblical text as the

basis for his remarks. This had led

to considerable criticism by Wilberforce

trustees, who considered that only

ordained clergymen should preach.

In stimulating alumni interest he

arranged in 1910 for the Wilberforce

University Club of Washington, D.C., to

join in a large meeting in the

capital attended by President Taft and

other notables, an occasion which

brought widespread attention to the

concerns of the university. In May

1912 he attended a reception in his

honor given by the Wilberforce alumni

of Kansas City. These are illustrations

of Scarborough's efforts to develop

an effective alumni association, but the

years of his presidency did not

meet with success in this respect.61

During Scarborough's administration the

Ohio flood of 1913, which was

especially disastrous in Dayton, cut off

the Wilberforce community from

telephone, telegraph, and railroad

connections with the surrounding country

for ten days. Pecuniary losses caused

some parents to withdraw their

224 OHIO HISTORY

children from the university, and

financial aid to the school was impaired

by the catastrophe.

At the Wilberforce commencement in June

1915 Scarborough had as

his house guest and commencement speaker

his Oberlin classmate Dr.

Hastings H. Hart, a brother of Professor

Albert Bushnell Hart of Harvard

and a leader in the work of prison

reform.62 During the early part of the

same year he had spent some time in

Florida, recuperating from an accident,

and in the summer had made a trip to

California. Returning from the

West he had met with Wilberforce alumni,

reaching home in time to speak

on "The Educational Value of

Environment" at the opening convocation

of the university. Scarborough's absence

from a meeting of the bishops

of the church, an absence due to his

convalescence in Florida, had pre-

vented him from meeting some criticisms

which they had made of the

operation of the school. Now he found it

necessary to reply with considerable

vehemence to the attacks upon his

administration.

Since 1914 Europe had been involved in

the First World War, with all

of its devastating fury, and in April

1917 the United States entered the

fray. With America's entry into the

struggle, Scarborough became much

involved in affairs relating to it.

Wilberforce students had received military

training since 1894. Indeed, it was the

only Negro college in the country

with a military department supported by

the national government and

with a regular military officer detailed

as instructor. Now Wilberforce

became a center for the examination of

applicants for the officers' training

camp at Des Moines, Iowa, and after

examination thirty young men were

sent there for training. Many

Wilberforce male students left school to

assist in food production. The

university of course joined in various

wartime activities. Scarborough became a

member of the Ohio Council

of National Defense, in reality the

governor's war cabinet. He also served

as one of the staff of Frederick C.

Croxton, federal food administrator for

Ohio; as one of three labor advisors in

Ohio to represent Negro labor in

the interests of food conservation; and

as a member of a special "Committee

of One Hundred" to assist in

mobilizing public opinion in enthusiastic

support of the war aims of the nation.

During the summer of 1917 about 180

Negro soldiers were trained in

the Wilberforce University training

detachment of the United States Army.

Scarborough also secured the

establishment of a unit of the Student Army

Training Corps, which began its

activities in September 1918. In general

the war department did not locate Negro

and white trainees in the same

barracks, so Ohio Negroes who entered

the corps were generally advised to

go to Wilberforce.

WILLIAM SANDERS SCARBOROUGH 225

Professors and students from Wilberforce

also went to a training camp

at Howard University to take intensive

preparation for service as clerks in

France. Scarborough, interested in those

from Wilberforce who went to

the officers' training camps, visited

such centers and was always well re-

ceived.63

After the signing of the armistice in

November 1918, the S.A.T.C. was

soon demobilized, and a reserve

officers' training unit was provided in its

place. For a time such training was

unpopular, as the war spirit had defi-

nitely waned. Now Wilberforce also

became a rehabilitation center for the

instruction of disabled soldiers in

various lines of vocational work.64

By this time the financial status of

Wilberforce had improved. Not only

gifts from alumni and other Negro donors

but also a gift of about $28,000

in assets from the closing of the Avery

Institute in Pittsburgh had been

extremely helpful. At the same time at

Wilberforce, local rivalries and

differing ideas of educational

objectives found expression in attacks on the

college department, and even a few

alumni were persuaded that it was their

duty to keep alive dissension between

the church-supported department and

that which received state aid.

Scarborough and his friends, however, were

able to prevent the passage of proposed

state legislation which would have

cut the $5,000 annual appropriation to

the university; to prevent the reduc-

tion of the number of Wilberforce

trustees so that the college itself would

have had but two of seven members of the

board, this proposal being vetoed

by the governor; and to defeat a measure

which would have made the normal

and industrial department an independent

institution with a head of its own.

This last proposal had resulted in a

legislative committee being created that

spent two days at Wilberforce looking

into the situation, but the legislature

took no further action and the status of

the institution at this time remained

as before.

The strain of the war and of contentions

on the campus had drawn heavily

on Scarborough's strength. During the

war the influenza had broken out

among those in the student training

corps, and every available hall had been

turned into a hospital. Scarborough had

taken two preventative serum injec-

tions, and for some reason these had

induced convulsions.

In March 1919 the death of Bishop

Cornelius Shaffer, who presided over

the affairs of the African Methodist

Episcopal Church in the Wilberforce

area, was a severe blow to Scarborough,

who had found in Shaffer a trusted

friend. The way was now paved for

attacks on Scarborough by those wishing

to advance the interests of others.

By this time the condition of the

university made the presidency a desir-

able one, and interested parties groomed

their candidates for the place.

226 OHIO HISTORY

Having served twelve years as a

conscientious president, Scarborough could

give a favorable report of his services

at the board meeting of the general

conference of the church. A modern

system of accounting had been insti-

tuted; bank credit had been restored;

considerable alumni interest had been

aroused; Founders' Day had been

developed as a contribution to financial

success; and the curriculum had been

revised, standards raised, and courses

enlarged and increased in numbers. Debts

had been reduced to $25,000;

the endowment fund had been increased;

state appropriations for the univer-

sity had been increased from $3,500

annually to $5,000; and Emery Hall

had been built and furnished.

Yet there was opposition to Scarborough.

A long feud had existed be-

tween Joshua H. Jones, president of the

board of trustees, and Scarborough.

Many believed that Jones now forced

Scarborough's retirement in an effort

to secure the place for his son, Gilbert

H. Jones. After two days of wrangling

among the board members, however, the

post went to John Andrew Gregg,

then president of Edward Waters College,

Jacksonville, Florida. Thus Scar-

borough's long official relations with

Wilberforce had come to an end.

[To be concluded in the next issue]

THE AUTHOR: Francis P. Weisenburger

is a professor of history at Ohio State

Uni-

versity. His latest book, Triumph of

Faith:

Contributions of the Church to

American Life,

1865-1900, was published earlier this year.