Ohio History Journal

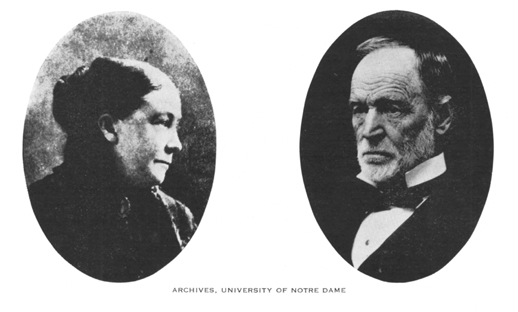

|

26 |

|

THE RELIGION OF WILLIAM TECUMSEH SHERMAN

by JACK J. DETZLER

Throughout his adult life William Tecumseh Sherman fought a battle with himself and his family that was far more personally intense and disturbing than any of his epic military campaigns: this conflict was, in a word, a battle for his soul.1 His religious faith and state of grace received frequent discussion within his family circle. An incessant dialogue went on between this God- fearing but nonsectarian husband and his dedicated Roman Catholic wife, Ellen. Through the years Sherman resisted the pressure for religious ortho- doxy, another sign -- if such were needed -- of the strength of character which made him an incomparable military leader during the Civil War. Sherman's attitude toward religion constituted one part of his general view of the way in which an individual should live. He assigned great im- portance to meeting all situations with honesty and truth, a belief he demonstrated in his business and army careers. As a banker he was clean-

NOTES ARE ON PAGES 68-70 |

THE RELIGION OF SHERMAN

27

handed even though he felt himself apart

from the times.2 Better, he con-

cluded, to lose his money, as he did,

than compromise his integrity. During

his army career he met in forthright

fashion all decisions requiring truth-

fulness -- as on the occasion he wrote

his wife from the camp before Corinth:

"I will not alter one syllable of

my official report."3 Sherman was confident

that the honesty of his actions would

stand out: in the long run, history

would expose the claims of his

opponents.4

Another of Sherman's beliefs was in the

duty man owed to his family and

associates. The personal duty appeared

in the Sherman family crisis which

erupted when his son Tom joined the

Jesuit order. The public duty appeared

in his support of the Union cause, when

much of his sympathy lay with

the southern people, among whom he had

lived and worked. The army always

had a sentimental call on his sense of

obligation.

Sherman believed that one met the

demands of life head-on, no matter

how unpleasant. He tackled life as he

found it: "I will do the best I can."

In his earliest recorded views he wrote,

if with no novelty of expression, of

the need to "grin and bear

it," to "stand up manfully, make the best of the

present."5 Sherman considered being

practical as part of facing life; and

practicality included an inventory of

assets, making judgments, proceeding

to action.6

He believed in taking the inevitable

with humor and was at ease with the

thought of death.7 But the grimness of

death and the inescapable problems

of daily living were never to obsure the

enjoyment of life, as Sherman fre-

quently lectured his wife. The darkness

which befalls every life must not

cloud the happiness of the hour. He

believed that the nature of human

existence was to challenge individuals

by every adversity and that the

balanced, tolerant man would survive.8

It seemed to him axiomatic that

"Time makes all things even"9

and unthinkable that anyone should hesitate

in stride. A man took his chances.

He believed that inexorable fate ruled

much of life.10 Perhaps this oft-

repeated principle served as the safety

valve for his personal, business, and

military problems. Throughout his life

he talked of the role of fate. Luck --

the happy face of fate -- he likewise

understood. In discouraging moments he

questioned struggling at all against

fate: "The antelope runs off as far as

possible but fate brings him back. Again

he dashes off in a new direction,

but curiosity or his Fate lures him

back, and again off he goes but the

hunter knows he will return and bides

his time. So have I made desperate

efforts to escape my doom."11

It is perhaps possible, therefore, to

say that Sherman's acceptance of

fate served as the link between his

philosophy of life and his sense of religion.

God knew the fate of all men.12 Fate,

defined as the will of God, was not

frightening because Sherman possessed

faith in the justice of his deity.

The deity Sherman honored held man

accountable to no formal doctrines

but governed by universal law of right

and justice which no man could alter.13

"I believe," he said,

"that God governs this world with all its life, animal,

vegetable, and human, by 'invariable

laws' resulting in the greatest good."

28 OHIO HISTORY

Near the close of his life he reiterated

his confidence: "I am sure that you

know that the God who created the minnow

and who has moulded the rose

and the carnation, given each its sweet

fragrance, will provide for those

mortal men, who strive to do right in

the world which he himself has stocked

with birds, animals, and men; -- at all

events I will trust Him with absolute

confidence."14

From uncertain youth, to manhood, to

elderly hero, he held his position.

Such was his religion and his

philosophy; but how could a Roman Catholic --

his wife, for example -- accept or even

tolerate it?

Sherman had been baptized a Catholic.15

His father was a Mason,16 and

his family was Presbyterian;17 but

young "Cump" grew to manhood, from

the age of nine onward, in the home of a

strict Roman Catholic foster

mother. All this had come about because,

when Sherman's father died in

1829, the father's good friend Senator

Thomas Ewing took Cump into his

own family and treated him as a son.18

Senator Ewing's sense of honor and

his tolerant religious views resulted in

insistence that the boy not have to take

a religious affiliation different from

that of his natural father. Young Sherman

observed but did not join the religious

rites of the household he called

home. He learned to view tolerantly the

religious attitudes of his foster

family during the seven years he lived

with them. Despite the Catholic

baptism, related above, he never

absorbed the devout Roman Catholicism of

Mrs. Ewing, his foster mother. Her

children reacted differently, with dedica-

tion to the Roman Church. Sherman's

attitude probably stemmed both from

his own family heritage and from

admiration for the Senator, who stood

aloof from the Catholicism of his

family. Years later Sherman saw Ewing

as "a great big man, an

intellectual giant," who "looked down on religion as

something domestic, something consoling

which ought to be encouraged,"

and to whom "it made little

difference whether the religion was Methodist,

Presbyterian, Baptist, or Catholic,

provided the acts were 'half as good' as

their professions."19

Sherman felt obligated to Ewing for his

youthful home, for his appoint-

ment to West Point, and even for the girl he married.

The Senator's daughter,

Ellen Ewing, was just four years

Sherman's junior and had been his child-

hood playmate. They were married in

1850, with the wedding in what is

now called Blair House in Washington --

that delightful old classic building

on Pennsylvania Avenue across from the

White House. Father James Ryder,

president of Georgetown University,

performed the ceremony.20

From the outset Ellen was disappointed.

Even though the marriage cere-

mony was impressive, with a dazzling

array of Washington politicians in

attendance, it was less than she had

wished for. Had she married a Catholic

boy, she could have had a "real

Catholic" wedding. She understood that

"Well educated Catholic young

gentlemen are scarce and Catholic girls

cannot all have an opportunity of

marrying suitably, in the church."21 To

marry a man such as Sherman, belonging

to no church, was a tolerable

alternative to Ellen, but she never

fully accepted it.

It was tolerable only after she

conducted long oral and written examina-

THE RELIGION OF SHERMAN 29

tions of Sherman's views toward

religion. As early as 1842 he tried to satisfy

her "curiosity," acknowledging

that after leaving home he had practiced no

special creed. He did believe

"firmly in the main doctrines of the Christian

religion, the purity of its morals, and

in the almost absolute necessity for its

existence and practice among all well

regulated communities to assure peace

and good will amongst all. "Yet, I

can not," he told her, "with due reflection,

attribute to minor points of doctrine or

from the importance usually attached

to them."22 He admitted

his ideas on religion were general, subject to time,

circumstance, and experience.

This latter observation provided the

wedge, the hope, with which the

dedicated Ellen sought to convert the

adamant Cump during the rest of

their long life together.

Ellen Sherman had developed her strong

religious views as a result of

her mother's training and from her

Catholic school education. She always

seemed happiest when in clerical

company. She held her children to a strict

Catholicism. Through the Church,

Catholic schooling, and her guidance the

children received the "religious faith

and fervor to prepare ... for the struggles

and temptations of the world."23

Ellen worked for Catholic charities, for

the Catholic poor, for struggling

Catholic authors, for the advancement of

Catholic chaplains, the protection of

Catholic reservation Indians -- for any

cause associated with the Church. Poor

Sherman considered her "absolutely

more Catholic than the Pope . . . far

more Catholic than any Roman ever

professed to be."24 Again

and again she went after her husband. Pressure

was constant -- subtle or obvious by

turn.

Her proselytizing fell into patterns. He

should, she argued, accept the

Catholic Church and faith for her sake,

for the sake of their family, for his

own sake, or for the sake of their

beloved deceased child Willy. Occasionally

she called attention to friends who had

become converts. At other times she

would censure him as a non-Christian.

She went after his soul with the

relentlessness of General Grant before

Richmond. She regularly told him of her

fervent prayers for his conversion.

Long before their marriage she had begun

to complain of Protestants torment-

ing and insulting her, and she

questioned Sherman as to how he could protect

and defend her from all ills when he was

classed among them. "How can

you be sincere in your defense unless

you . . . can prove the truth of that

which I claim to be true."25 Sherman's

unresponsiveness, she charged, denied

her the assistance she was entitled to

in raising their children, denied their

married life a close and perfect

communion both here and in heaven.26 "My

happiness depends on yours, my misery on

yours. If you die without uttering

a prayer for mercy I shall lose my

reason. It would kill me to see you die

without faith and prayer. Save me that

sorrow in this world and in the next."27

When the appeal of her own happiness

could not move him, Ellen Sherman

sought to have her husband accept

Catholicism for the sake of his family.

"If you die without faith you leave

us miserable the rest of our lives with a

weight of sorrow upon the heart which no

worldly influence can dissipate.28

And think what happiness it would confer

upon those all who are nearest

30 OHIO HISTORY

and dearest to you."29 She hoped

that when he died his children "may mourn

for you . . . not alone as one of

earth's heroes but as an humble and devout

believer in the divinity of our Saviour."30

Ellen then turned to self-interest. For

Sherman to die outside the Church

was a disaster for himself. Although the

family prayed for him, this was

not enough -- his own prayers were

essential. Conversion was a positive

benefit, he was told, for "peace

which surpasseth all human understanding.

Why do you not go to the Church since

you find no hope and no peace out

of it. It cannot do you any harm. It

must do you so much good."30 His

attacks of depression and melancholia,

she said, perhaps oblivious of her own

contributions to his moods, would

disappear in the glory of the great faith.

Sherman, who in the war was sacrificing

so much for others, need sacrifice

only his human pride to gain heaven for

himself.31

Ellen never gave up. The deceased son

Willy had been their idol: the

eldest son, a bright boy with a winning

personality. He died suddenly of

fever while visiting Sherman's camp on

the Mississippi in 1863. An inordinate

grief, continuing for the rest of their

lives, took hold of the parents. Ellen

well recognized her husband's attachment

and did not scruple to use it when

urging Sherman to join the Church.

Immediately after Willy's death she

told Sherman of the faith and hope the

child had held for his father's religious

future. Subtly she associated God's

goodness, in which Sherman believed,

with Willy's faith: Sherman could

"die in the faith that sanctified our holy

one."32 With Willy

praying for him in heaven and his other children praying

to Willy "to pray for Papa,"33

Ellen relentlessly pressed her husband to

become a Catholic during probably the

most emotional moment in his

life. If anything on earth could aid

Willy in heaven, he learned, it would be

knowledge that his father had said

prayers for his soul: "Ask Willy to

pray for you and God will give you

faith. Willy felt very badly about your

not having faith and it was a trial to

his loving heart to know that the father

he so idolized on earth never prayed to

God for blessings which are eternal.

Of course I never talked to him of

this," Ellen admitted, "but he made the

application of faith and religious

instruction and in his heart lamented what

he had too much love and respect for you

to criticize and he lamented it as

a misfortune, but little things several

times showed me his keen feelings on

the subject which he sought to

conceal."34

Through the years Sherman saw Ellen use

the name of every casual

acquaintance who joined the Catholic

Church as witness to the ease with

which sensible friends saw the path to

salvation. On occasion she struck out

viciously, charging that her husband was

not even a Christian. While she

always embedded this denunciation in

phrases complimenting Sherman's

kindness, gentleness, generosity, and

goodness, the indictment was never-

theless clear. She told him in 1862,

when he had many nonreligious concerns,

"You only want Christianity to make

you perfect. With all your natural

goodness, your honor and high toned

principle you are not the Christian that

I believe we will see you before you are

called to your long account."35

THE RELIGION OF SHERMAN

31

Sherman absorbed these pressures and

responded in various ways, demon-

strating always a devotion to his

philosophy of life. He held to his convic-

tions as to the role of religion in

life. His response varied from tolerance of

all religious discussion to full

annoyance with those practicing intolerance.

Throughout his experiences runs the

denominator of an open mind, ques-

tioning, indeed puzzling, about

religion. His views were consistent with broad

Christian doctrines but never in accord

with the principles of the Roman

Church.

Sherman's religious tolerance appeared

in his relations with his children

who were reared as Roman Catholics. When

in his care, they attended church

and he reported to his wife the daily

fulfillment of their religious obligations.

This habit continued even after his

quarrel with the Church, which is

characteristic of his sense of

responsibility. He could always point out that

he had never placed an obstacle to his

children's practice of their mother's

religion.36 He seemed to have

satisfaction knowing they would "grow up on

the safe side about the Great

Future" with a security he could not have.37

Except during the family crisis over his

son's decision to become a priest,

Sherman showed only friendliness toward

the Church. He preserved a gift

of a religious medal, and many times

referred sympathetically to colleagues

who were Church members.38 He seemed to

recognize the strength these

communicants drew from Catholicism. He

was sensitive to the dedicated

work of the Sisters of the Holy Cross

and responded to overtures of friend-

ship from the clergy of the University

of Notre Dame.39

In many instances Sherman's general

appreciation of the Church appeared

in his showing almost special favors to

the Catholic religious, often in

response to requests of his wife, but

willingly and wholeheartedly given.

During the war he cooperated with

sisters working in hospitals of his military

command and permitted them to use his

name, unusual for him, in their

money-raising programs. His reception of

the Rev. Joseph Carrier, C.S.C.,

as a chaplain at his camp on the

Mississippi in 1863 was noted in Catholic

circles for its openheartedness. Ellen

had secured the priest's assignment to

Sherman's army, but Sherman far extended

himself in welcome.40

Friendly interest in the Church is shown

by his visits to churches during

his travels. While every tourist

includes churches for sightseeing, Sherman's

detailed descriptions are unusual. At

first he did show an early naivete about

religion, but that disappeared in the

later travels. In 1846 he looked at the

surface scene and was shocked to see

communicants "more like squaws than

good Christians."41 His

efforts to appear worldly and experienced caused him

to generalize at what he observed in a

moment, and he concluded impulsively

in Rio de Janeiro that "the church

stamps a strong character upon all the

people."42 If the tone was

critical, the observations showed Sherman as anxious

to compare, contrast, learn, observe.

His spirit was of the inquisitive, inquiring

student.

A much more sophisticated Sherman toured

Europe in 1872 -- still describ-

ing church structures in long letters to

his wife. By this date his comments

32 OHIO HISTORY

set out the role of religion in European

politics and the lives of people. He

was amused that so many religions

throughout the centuries had claimed to

be the "true religion." He

regarded whimsically the Egyptian's evaluation

of Christians as an "inferior

race," but viewed with distress the magnificent

Spanish mosques which bore such a large

investment of human toil. These

structures he saw as devoid of reverential

feeling, unworthy of their symbolic

position.43 Only in Russia and

Switzerland did he find religious sincerity

and zeal.44 In Russia the religion

combined the Moslem and the Catholic

forms, which pleased him because it

reinforced his view that true religious

ideas are universal and form is

unimportant. The European travel resulted

in his thinking about religion in the

lives of people -- not as deity-centered --

but as a political instrument. In

France, Italy, Germany, and England he

observed with disdain the effects of

religious groups on politics; in private

correspondence he repeatedly praised the

American separation of Church

and State. He hoped that eventually

churches, priests, and preachers would

"confine themselves to their own

special sphere and leave politics alone."45

He long had felt that religion often

disregarded common sense, and his

experiences in Europe confirmed this

belief. He had always sought to under-

stand God through reading, thought, or

discussions with informed persons.46

None of these efforts led him to a

doctrinaire position. He never became

interested in abstract points of

doctrine, try as he might for the sake of his

wife. His position became one of defense

of his right to disagree, more than

aggressive attack on those who opposed

him.

This mood and this approach to religion

may have entered into Sherman's

decision to decline the Republican

nomination for the presidency in 1884.

His biographer has implied, although

without proof, that acceptance would

have involved him in a defense of his

family's religion.47 Defense of a particular

religion was not his way; just as he

would not have placed himself in a

position antagonistic to religion. Had

the religious question been of import-

ance in the decision about the

nomination, his philosophical views of duty

might have required him to accept the

nomination to defend his belief in

man's right to tolerance. He regarded

himself as truly catholic because he

"embraced all Creation, recognizing

the maker as its heart and all religions

past present and future as simple tools

in the great accomplishments yet to

be."48 This

all-encompassing religious feeling, first expressed in 1844, con-

stituted his perennial appraisal of God.

The "same God who made the

universe and afterwards permitted his

son to be massacred to display his

interest in the human family . . . will

enable us if we exercise properly our

judgments with due charity and sincerity

to attain a fair share of worldly

happiness."49

Politics was something Ellen did not

understand, and Sherman had to

be careful when her religious zeal

carried political ramifications. While he

was on the European vacation, Ellen

demanded that he visit Catholic ac-

quaintances. This annoyed him, for he feared

that crafty European politicians

would give the gesture a religious

interpretation and he would be labeled a

member of the Church. Sherman felt that

his wife lacked appreciation of

THE RELIGION OF SHERMAN 33

his position, and refused. "I can

hardly expect you," he wrote, "to feel as

I do about these things and deeply

regret that you always set your heart on

things that do not chime in with my

preferences or prejudices. I wish you

would tax me in some other ways."50

Sherman found his wife's intolerance of

Protestants obnoxious, but ac-

cepted the situation. More difficult to

bear was the intolerance shown by

his children.51 Even though

he knew that his wife's zeal absorbed the better

instincts of her nature, he warned her

that she should help the children

avoid bigotry. He wanted them to have

"every chance possible to conform

to ... religion and . . . whilst

enjoying the widest privilege not to question

the sincerity of others."52 His

wife was never obedient to this wish.

Ellen believed parochial school training

essential and nagged Sherman into

enrolling the children in Catholic

schools, calling the public schools "schools

of corruption!" She was

"mortified and distressed" that her "children have

ever gone to them."53 She

beseeched Sherman to give the children a "Catholic

education" should she die. A major

family consideration in Sherman's accept-

ance of any position was always the availability of

Catholic schools.54 Sherman,

for his part, felt that Catholic schools

were not skilled in teaching sciences,

but accepted his wife's desire,

nevertheless. He was convinced the home,

not the school, controlled religion and

morals; any school could teach subject

matter. Learning "depends more on

you than the school master."55

Not until his son Tom joined the

priesthood did Sherman regret that his

children had received a Catholic

education. From that time on Sherman

was a harsh critic of the Catholic

educational system. Not only, he said,

did it separate children from parents,

but failed to accept modern knowledge.

In fact, he rejected parochial schools

as incompetent.56 He felt they had

unduly influenced his son, and he was

bitter for the remaining years of his

life. He presented his case to anyone who would listen.

A minor irritant was his wife's

financial contributions to the Church. She

protested that she used her own funds.57

The son's decision to enter the

priesthood occurred at the same time

Congress cut his salary. The family

finances tightened. Sherman complained

endlessly of the $20,000 he had spent on

his son's education -- an investment

from which he would receive no return.58

In worldly transactions, he said,

"this would be simply

swindling."

Sherman centered his outward protest of

his son's decision only around

this point. He saw that his plans were

"all wrecked," for Tom had been

the "keystone" in his plan for

family security and "his going away lets

down the whole structure with a

crash."59

Tom Sherman's decision to join the

Jesuits had come as a surprise, but

only because through the years the

father had closed his eyes to many clear

signs. Tom was seven when Ellen wrote

Sherman she had urged the boy

to "use his talents for the greater

honor of God . . . not for the acquisition

of worldly position or renown."60

When he was eight and "fairly well estab-

lished at school," Sherman wrote he

would "risk his being a priest." He

did not want him a priest and would

reject such a choice, but Tom was

34 OHIO HISTORY

"too young for even the thought of

it." When he was fifteen and a student

at Georgetown, Sherman saw the fervor of

Catholicism in him and urged

him to respect the religious views of

others.61 But the boy, like his mother,

rejected the father's pleas for

tolerance.

Then came the vocational decision. When

he heard of it, Sherman exploded.

He directed his anger toward the Church,

rather than toward his son. He

labeled the Church a public enemy whose

policies eventually would erupt

into violence. This selfish institution

had committed a crime in taking his

son away "from the legitimate work

cut out for him."62 He concluded that

Tom's alienation had begun in the

Catholic schools. He raged at the Church

which claimed the right to educate

children at their parents' expense and

then, "under inspiration called

'vocation,'" took the children for its use.

He challenged the idea of a calling to

the priesthood. His practical mind

said that such an idea denied reason;

its acceptance implied blind animal

reaction. God gave man reason, he

argued, and man's obligation was to use

it. The Church had led Tom to disregard

duty to the family, an obligation

no man had the right to throw off, even

to save his soul. Sherman said the

demands of religious life were vapors

compared with responsibilities of man

to his fellow man.63 Concern

over the next life was self-indulgence incom-

patible with obligations held, willingly

or unwillingly, in this world.

His views annoyed his family and his

Catholic friends. In turn, he resented

their lack of sympathy. He believed that

because of Tom's decision the

Church was using his name and position.

The Church was trying to capture

him and his office by indirection.

Should Catholic journals continue to

publish statements indicating he had

consented to Tom's decision or should

the Church become brazen over its

victory, he threatened a public pronounce-

ment of "eternal condemnation"

of the Roman institution.64

The family handled this anger with

patience and kindness.65 After the

shock he would become his tolerant self;

they knew his habits of fairness.

Time proved them largely correct, as he

accepted the inevitable in keeping

with his philosophy of life. Through the

efforts of his family a rapprochment

with the Church took place. He returned

to his mild acceptance, his gentle

skepticism, his pleasant tolerance.

The family prayed that Tom's decision

would bring a state of grace and

Church membership to Sherman.66

After his wife's death, the children

replaced her as the voice pleading for

his conversion; and in the last moments

of his life they exercised their

loving prerogative. Believing their

father would not have denied them the

comfort of knowing he died in their

faith, they obtained for him -- as he

lay unconscious, about to die -- the

last rites of the Church,67 the institution

of which he once said, "claims to

be God himself -- O.K. -- We will find out

in time."68

THE AUTHOR: Jack J. Detzler is As-

sistant Professor of History at the

Indian-

apolis Downtown Campus of Indiana

University.

68 OHIO

HISTORY

12. See Bernard Mayo, "Lexington:

Frontier Metropolis," in Eric F. Goldman, ed.,

Historiography and Urbanization (Baltimore, 1941), 21-42; and Niels H. Sonne, Liberal

Kentucky, 1780-1828 (New York, 1939), 160-242.

13. See Cincinnati Daily Gazette, September

1, 1837.

14. J. D. B. DeBow, Statistical

Review of the United States (Washington, D. C., 1854),

192.

15. There are numerous sources detailing

Cincinnati's rapid economic and commercial

significance. Of special significance

are the three works of Charles Cist: Cincinnati in

1841 (Cincinnati, 1841); Cincinnati in 1851 (Cincinnati,

1851); Cincinnati in 1859 (Cin-

cinnati, 1859).

16. - - - Sherwood to sister, October 6,

1848. Cincinnati Historical Society.

17. Cist, Cincinnati 1859, p.

240.

18. John Quincy Adams to William Greene,

May 1, 1844. Greene Papers, Cincinnati

Historical Society.

19. Mildred Crew, "J. J. Ampere's

Journey Through Ohio: A Translation from His

Promenade en Amerique," Ohio

State Archaeological and Historical Quarterly, LX

(1951), 74.

20. Charles Beecher, ed., Autobiography

and Correspondence of Lyman Beecher,

(New York, 1865), II, 268.

21. Isaac Jewett to Joseph Willard, May

8, 1831. Jewett Letters, Cincinnati Historical

Society.

22. See, for example, The First Fifty

Years of the New England Society, a Historical

Sketch (Cincinnati, 1895). The Cincinnati Historical Society

has a collection of pamphlets

relating to this society; one was

written by Lyman Beecher.

23. Emmet F. Horine, Daniel Drake,

1785-1852, Pioneer Physician of the Midwest

(Philadelphia, 1961). See also, Edward

D. Mansfield, Memoirs of the Life and Services

of Daniel Drake (Cincinnati, 1855).

24. Edward D. Mansfield, Personal

Memories (Cincinnati, 1879), 167. Mansfield dis-

cusses Drake's "genius and

character" on pages 167-173.

25. Venable, Literary Culture in the

Ohio Valley, 304.

26. Longworth is sorely in need of

biographical attention. There is a sympathetic

personal portrait of him in Clara

Longworth de Chambrun, The Making of Nicholas

Longworth (New York, 1933), 27-54.

27. For example, Catherine Anderson

wrote to Hiram Powers on November 25, 1851

that Longworth had become a patron of

all the "young poetesses" in Cincinnati. Powers

Collection, Cincinnati Historical

Society.

28. Francis and Theresa Pulszky, White,

Red, Black, Sketches of American Society

(New York, 1853), I, 295.

29. Moncure D. Conway, Autobiography:

Memories and Experiences of Moncure

Daniel Conway (Boston, 1904), I, 255-256.

30. Ibid., I, 259.

31. Yeatman Anderson, III, "Early

Cincinnati Printing," Guidepost, publication of

Public Library of Cincinnati and

Hamilton County, XLI (January 1966). Mr. Anderson

is curator of rare books at the Public

Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County.

32. Cist, Cincinnati in 1841, pp.

262-263.

33. Sutton, Western Book Trade, 67.

34. Cist, Cincinnati in 1859, p.

322.

35. See Sutton, Western Book Trade, Chap.

8.

36. The Cincinnati Historical Society is

blessed with an excellent collection of travel

works.

37. Harriet Martineau, Retrospect of

Western Travels (London, 1838), II, 56.

38. The tourist was Alexander Zimmerman,

Russian industrialist. From "A Journey

in America," Russian Messenger

(Russkii Vestnik), XXIII (Moscow, 1859), 99-109.

39. Charles Fenno Hoffman, A Winter

in the West (New York, 1835), II, 132-133.

40. Gorham A. Worth, Reprint of

"Recollections of Cincinnati, From a Residence of

Five Years, 1817 to 1821," Quarterly

Publication of the Historical and Philosophical

Society of Ohio, XI (1916), 38.

THE RELIGION OF

WILLIAM TECUMSEH SHERMAN

1. The major source for this paper has

been the William Tecumseh Sherman family

letters and papers in the Archives of

the University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame,

Indiana. Included in the collection are: the personal

correspondence between Sherman

and his wife from 1842 to 1888; miscellaneous letters

between members of the family;

newspaper clippings; photographs; miscellaneous

materials; and copies of letters from

Sherman to Major Henry Turner of St.

Louis, John T. Doyle of Menlo Park, California,

NOTES

69

and Sherman's daughter, Minnie Sherman

Fitch. The place of deposit of the Turner

and Doyle letters is unknown; the

letters to Minnie are held by The Ohio Historical

Society. The collection was preserved

and given to Notre Dame by Sherman's

granddaughter, Eleanor Sherman Fitch,

daughter of Minnie. All the letters and other

manuscripts cited hereafter are from

this collection unless it is indicated otherwise. The

collection has been open previously only

in part and has never been used in evaluating

Sherman's religious views. Some of the

letters between Sherman and his wife were

heavily edited by M. A. DeWolfe Howe and

published under the title of Home Letters

of General Sherman (New York, 1909). Howe deleted most references to

religion.

Other Sherman letters and papers are

scattered. The largest collection is in the Library

of Congress and covers his career in the

military, banking, law, and education. Most of

these papers, deposited by his son

Philemon T. Sherman and Eleanor Sherman Fitch,

are less personal.

The author wishes to thank Professor

Robert Ferrell of Indiana University and the

Rev. Thomas McAvoy, C.S.C., archivist

and professor of history at the University of

Notre Dame, for their suggestions and

assistance in the preparation of this paper.

2. Letter of Sherman to Ellen Sherman,

October 6, 1857.

3. Sherman to Ellen Sherman, May 3,

1862.

4. Sherman to Ellen Sherman, June 6,

1862, April 5, 1865.

5. Sherman to Ellen Sherman, May 18,

1872, February 3, 1848, November 1, 1850.

6. Sherman to Ellen Sherman, June 8,

1861; Sherman to his son Thomas Sherman,

September 13, 1874, January 24, 1878.

7. Sherman to Ellen Sherman, April 10,

1848, September 18, 1855.

8. Sherman to Ellen Sherman, March 1,

1877, September 10, 1881.

9. Sherman to Thomas Sherman, March 4,

1876.

10. For example, Sherman to Ellen

Sherman, April 15, 1859.

11. Sherman to Ellen Sherman, February

21, 1860.

12. For example, Sherman to Ellen Sherman,

October 6, 1861.

13. Sherman to Ellen Sherman, July 12,

1845.

14. Sherman to Major Henry Turner, July

7, 1878; Sherman to T. DeWitt Talmage,

December 12, 1886, in Edward W. Bok, The

Americanization of Edward Bok (New York,

1923), 215-218. Turner was a St. Louis

business acquaintance of Sherman's.

15. Ellen Ewing Sherman,

"Recollections for My Children," a manuscript, dated Octo-

ber 28, 1880. No official records exist

showing Sherman's baptism. His brother John

Sherman says he was baptized by a

Presbyterian minister. John Sherman, Recollections

of Forty Years in the House, Senate

and Cabinet (Chicago, 1895), I, 26.

Ellen disputes

this in her "Recollections,"

saying that a similar statement which had come to her atten-

tion was not true and that her mother,

Maria Boyle Ewing, confirmed that Sherman had

been baptized in the Ewing home by

Father Dominic Young. At the time of Sherman's

death in 1891 his sons stated that he

had been baptized as a child by a priest.

16. William Tecumseh Sherman, Memoirs

of General William Tecumseh Sherman

(New York, 1892), I, 13.

17. John Sherman, Recollections of

Forty Years, I, 26.

18. W. T. Sherman, Memoirs, I,

14.

19. Letter in Bok, Americanization of

Edward Bok, 216, cited above.

20. There is a description of the

wedding in Minnie Sherman Fitch, "Tribute to Ellen

Ewing Sherman," a manuscript. See

also Anna McAllister, Ellen Ewing, Wife of Gen-

eral Sherman (New York, 1936), 62-63; and Katherine Burton, Three

Generations (New

York, 1947), 75-77.

21. Ellen Sherman to her daughter Minnie

Sherman, May 2, 1871.

22. Sherman to Ellen Sherman, April 7,

1842.

23. Ellen Sherman to Sherman, October

21, 1863.

24. Sherman to John T. Doyle, April 26,

1881. Doyle, a prominent lawyer, was an

early California acquaintance of

Sherman's.

25. Ellen Sherman to Sherman, July 2,

1844.

26. Ellen Sherman to Sherman June 16,

1855, December 26, 1861.

27. Ellen Sherman to Sherman, February

22, February 21, 1862, January 4, 1865.

28. Ellen Sherman to Sherman, December

29, 1864.

29. Ellen Sherman to Sherman, August 6,

1862.

30. Ellen Sherman to Sherman, December

26, 1861.

31. Ellen Sherman to Sherman, January 8,

1862, January 4, 1865.

32. Ellen Sherman to Sherman, October

21, 1863.

33. Ellen Sherman to Sherman, November

9, 1863.

34. Ellen Sherman to Sherman, January

29, 1864; see also Ellen Sherman to Sherman,

November 15, 1863.

35. Ellen Sherman to Sherman, March 7,

1862, August 16, 1866; see also Ellen Sher-

man to Sherman, September 15, 1855, June

23, 1861.

36. Sherman to Ellen Sherman August 8,

1886; Sherman to Major Henry Turner,

May 27, 1878.

37. Sherman to Ellen Sherman, July 16,

1861.

70 OHIO

HISTORY

38. Sherman to Ellen Sherman, June 17,

1845, September 24, 1850.

39. Sherman to Ellen Sherman, October

10, 1863; Sherman to Minnie Sherman,

March 15, 1863, January 28, 1864;

Sherman to the Rev. Edward Sorin, C.S.C., March 1,

1867, May 5, 1870. Father Sorin was

president of the University of Notre Dame.

40. Sherman to Ellen Sherman, June 6,

1862, April 30, 1878; Sherman to Minnie

Sherman, October 4, 1862; David P.

Conyngham, "Soldiers of the Cross" (manuscript,

University of Notre Dame), Chap. IV;

Ellen Sherman to Sherman, June 23, 1861. Indi-

cations, but no proof, exist that Ellen

Sherman had the Rev. Joseph Carrier, C.S.C., sent

to Sherman's camp to check on reports

that her husband was mentally disturbed.

41. Sherman to Ellen Sherman, September

16, 1846.

42. Sherman to Ellen Sherman, September

18, 1846.

43. Sherman to Ellen Sherman, January 6,

March 24, 1872. An example of his detailed

church descriptions is in the letter of

January 6.

44. Sherman to Ellen Sherman, May 26,

July 24, 1872.

45. Sherman to Ellen Sherman, July 26,

1872. See also Sherman to Thomas Sherman,

March 1, 1872.

46. Sherman to Ellen Sherman, October

29, 1859, September 17, 1844.

47. Lloyd Lewis, Sherman, Fighting

Prophet (New York, 1932), 628-631.

48. Sherman to Ellen Sherman, July 14,

1855.

49. Sherman to Ellen Sherman, June 14,

1844.

50. Sherman to Ellen Sherman, July 26,

1872. See also Sherman to Ellen Sherman,

July 7, 1872.

51. For examples of the children's

intolerance, see Minnie Sherman to Ellen Sherman,

May 29, 1878, and Thomas Sherman to his

brother Philemon Sherman, February 24, 1890.

52. Sherman to Ellen Sherman, August 25,

1872.

53. Ellen Sherman to Sherman, November

21, 1860. This is a copy of the original

letter, which was destroyed by Philemon

Sherman.

54. Ellen Sherman to Sherman, April 29,

1855, December 1, 1859.

55. Sherman to Thomas Sherman, November

10, 1864; Sherman to Ellen Sherman,

November 29, 1860; Sherman to Thomas

Sherman, March 29, 1872.

56. Sherman to Minnie Sherman, April 20,

1888, January 2, 1890.

57. Ellen Sherman to Sherman, January

29, 1861, August 1879, April 4, August 23,

1887.

58. Sherman to John T. Doyle, June 16,

1878.

59. Sherman to Major Henry Turner, June

28, June 5, July 24, 1878.

60. Ellen Sherman to Sherman, April 15,

1864.

61. Sherman to Ellen Sherman, January

15, 1865; Sherman to Thomas Sherman,

March 29, 1872.

62. Sherman to Ellen Sherman, September

16, 1883. See also Sherman to Mrs. Alex-

ander Thackara (Eleanor Sherman), May

24, 1881; Sherman to Minnie Sherman, June

16, 1878; and Sherman to John T. Doyle,

July 28, 1878.

63. The quotation is from Sherman to

Major Henry Turner, July 13, 1878. See also

Sherman to Major Turner, May 27, July 7,

1878.

64. Sherman to Major Henry Turner, May

27, 1878. See also Sherman to Minnie

Sherman, June 16, 1878, and Sherman to

John T. Doyle, July 28, 1878.

65. Thomas Sherman's relationship with

his father is reflected in Thomas Sherman

to Sherman, May 25, 1878, July 14,

September 1, 1880. The gradual softening of Sher-

man's attitude is seen in Sherman to

Ellen Sherman, August 24, 1880 (postscript written

by Rachel Sherman), and Sherman to Mrs.

Alexander Thackara, December 30, 1880.

66. Ellen Sherman to Minnie Sherman. May

31, 1878.

67. Letter of John Sherman, dated

February 13, 1891, in New York Sun, February 19,

1891. See also John Sherman, Recollections

of Forty Years, II, 1102-1103.

68. Sherman to Mrs. Alexander Thackara,

May 24, 1881.

NOTES ON THE

ANTE-BELLUM CATTLE INDUSTRY FROM

THE McNEILL FAMILY

PAPERS

The author gratefully acknowledges the

patient encouragement, guidance, and criticism

of Dr. William D. Barns in a seminar in

American Agricultural History at West Virginia

University.

1. James Westfall Thompson, History

of Livestock Raising in the United States,

1607-1860, United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural

History Series, No. 5

(November 1942); Charles Townsend

Leavitt, "The Meat and Dairy Livestock Industry,

1819-1860" (unpublished doctoral

dissertation, University of Chicago, 1931).