Ohio History Journal

HELEN M. THURSTON

The 1802 Constitutional Convention

and Status of the Negro

What does the 1802 Ohio constitution

say regarding freedom, suffrage, and "citizen

rights" for negroes and mulattoes?1

How were decisions made at the constitutional

convention? Who were the

decision-makers?

Since even today confusion exists in

historical studies on these questions, it is

hoped that answers, in some degree, can

be obtained from a vote by vote study of

the eight major motions concerning the

negro that were taken up at the convention.2

Even though a detailed account of the

proceedings was not kept that would tell us

how decisions were made, it is possible

to determine from the official journal and

from biographical data that has not been

widely used by previous researchers what

decisions were made, who voted in what

way, and what outside factors were not

influencing the vote. This study then

consists of an analysis of the voting patterns

that led to the final wording of the

constitution relative to the status of negroes and

mulattoes. From these patterns certain

quantitative inferences are made that appear

to be valid. Since personal motivation

of the delegates concerning particular votes

is not known in most cases, qualitative

judgments are avoided.

One historian who has written in more

detail than most others on the voting at

the convention concludes from his

analysis that the delegates were "more controlled

by feeling than by reason."3 At

times the voting does seem to be contradictory and

1. The term "citizen rights"

is used within quotation marks to indicate that it is a coined

term used to refer to general civil

rights normally granted to white citizens in the early 1800's.

In the journal of the convention these

rights were not designated by a specific adjective but

were referred to only as "section

seven."

2. Some general studies of the Ohio

Constitutional Convention of 1802 are included in

the following works: Richard Frederick

O'Dell, "The Early Antislavery Movement in Ohio"

(unpublished Ph.D. dissertation,

University of Michigan, 1948), 96-128; William T. Utter, The

Frontier State, 1803-1925 (Carl Wittke, ed., The History of the State of Ohio,

II, Columbus,

1942), 3-31; Julia Perkins Cutler, Life

and Times of Ephraim Cutler: Prepared from His

Journals and Correspondences. . . (Cincinnati, 1890), 66-82; Frank U. Quillin, The

Color Line

in Ohio: A History of Race Prejudice

in a Typical Northern State (Ann

Arbor, 1913), 13-20;

Daniel J. Ryan, History of Ohio: The

Rise and Progress of an American State (Emilius O.

Randall and Daniel J. Ryan, History

of Ohio, III, New York, 1912), 111-141; Alfred Byron

Sears, Thomas Worthington: Father of

Ohio Statehood (Columbus, 1958), 94-112; Charles

B. Galbreath, History of Ohio (Chicago,

1925), II, 13-34. See also Ruhl Jacob Bartlett, "The

Struggle for Statehood in Ohio," Ohio

Archaeological and Historical Publications, XXXII

(1924), 494-505; John D. Barnhart,

"The Southern Influence in the Formation of Ohio,"

Journal of Southern History, III (1937), 28-42.

3. Quillin, Color Line in Ohio, 13-20.

Mrs. Thurston is the Managing Editor of Ohio

History.

|

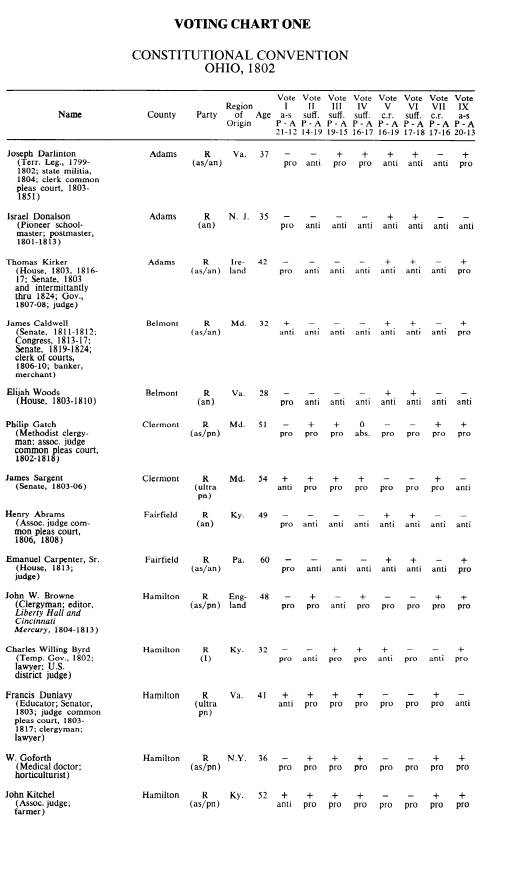

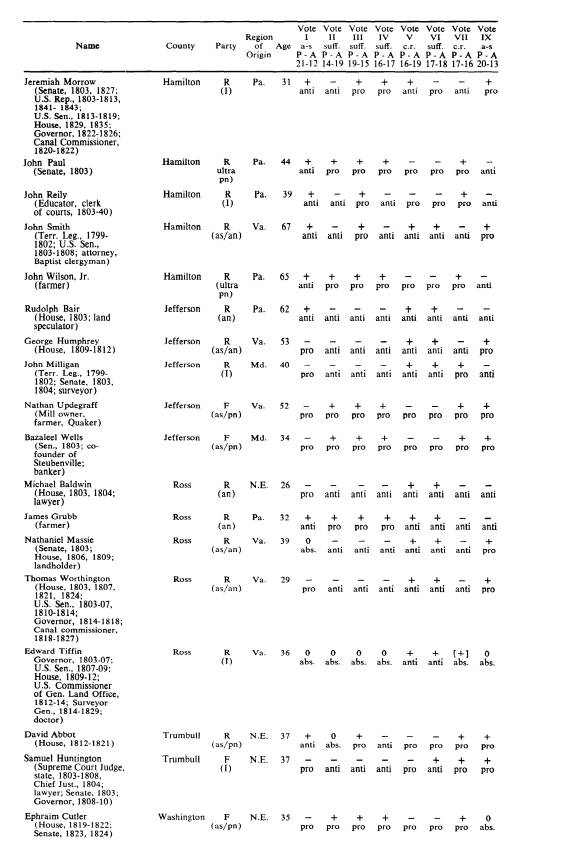

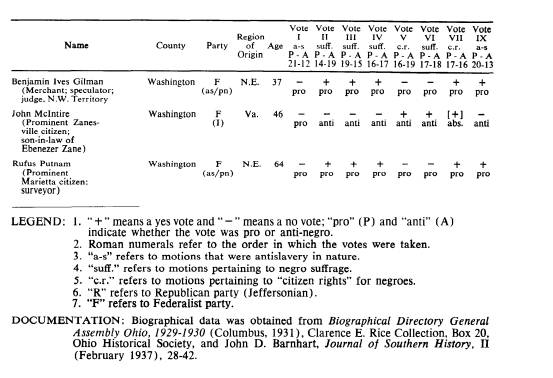

emotionally motivated, and this may be so because of the complexity of the problem. There were three separate issues being decided and each issue involved various shades of opinion. Votes were taken on (1) the bill of rights, especially as applied to freedom for negroes and mulattoes; (2) elector or voter qualification, and (3) "citizen rights," especially as applied to negroes and mulattoes. Motions were considered on these issues in a logical order. First the decision was made not to admit slavery in any form. If there were to be only free white and black men in Ohio, the next decision to be made was who should have suffrage? On that question, the convention decided that the blacks were not to be given the vote or be counted for electoral purposes. Finally, the decision was made concerning what rights and privileges accorded white citizens should be denied negroes. On this issue the constitution was allowed to remain silent.

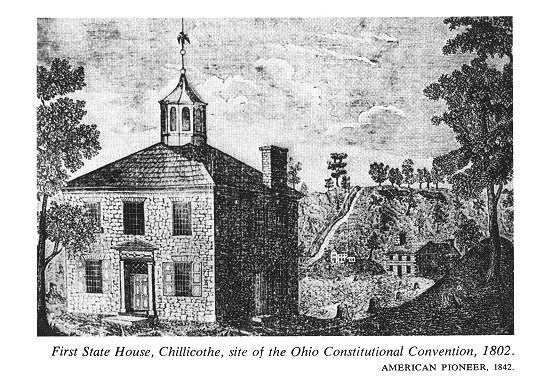

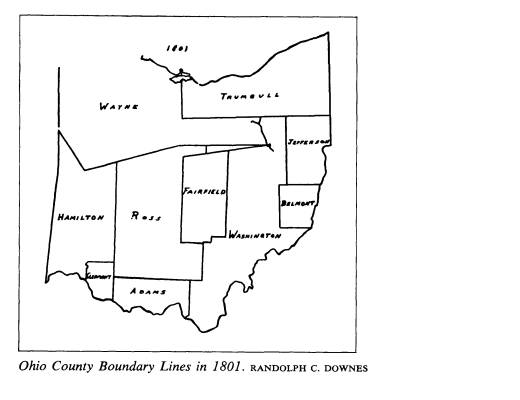

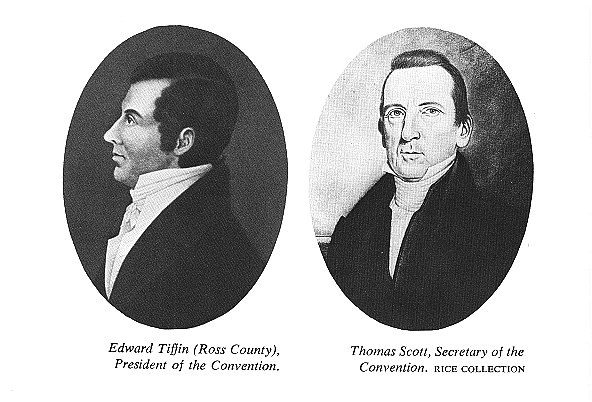

I In response to authorization given "the people of the eastern division of the territory of the northwest of the River Ohio," on April 30, 1802, thirty-five delegates were chosen from nine counties in the territory, representing more than 45,000 residents. The delegates met in Chillicothe on November 1, 1802, for the purpose of drawing up a constitution for the new state which they designated "Ohio."4 At the time of the convention the most populated regions of the territory were around the principal cities: Cincinnati (Hamilton County had ten delegates), Chilli- cothe (Ross County had five delegates), Steubenville (Jefferson County had five delegates), and Marietta (Washington County had four delegates). Northeastern and eastern areas were represented by two delegates from Trumbull County and by two

4. United States Statutes at Large, Vol. II, 173; Annals of Congress, 7 Cong., 1 Sess., 268, 275, 294, 295-97, 1252, 1349-51; Ryan, History of Ohio, 106. |

|

delegates from Belmont County. Southern regions were represented by two delegates from Clermont and by three from Adams County. Central Ohio was represented by two delegates from Fairfield County. No representatives were sent from Wayne County in the northwestern part of the territory because it had been excluded from the enabling act, since the greater part of it lay outside the geographical limits set for the state.5 About seven professions or combinations of one or more were repre- sented by this group of delegates: many were or became legislators, three educators, two doctors, seven lawyers, land developers, three clergymen, and two farmers. The youngest was a spirited lawyer Michael Baldwin at twenty-six and the oldest was the prominent Baptist John Smith at sixty-seven. (See Voting Chart One, p. 31.) In formulating the bill of rights article many of the general principles found in the United States Bill of Rights were repeated with slight rewording, but many of the specific provisions for choosing elective officials and the duties and responsibilities thereof were tailor-made in Chillicothe. Even though they were especially designed for Ohio's problems, they were kept within acceptable bounds established by the other states.6 At the time of the convention there were only a reported 337 negroes in the territory, and the bulk of these was claimed by one researcher to have been in Wayne County.7 The delegates were thus asked to decide upon principles governing the status of negroes before the lawmakers could know what intra and inter-state racial problems statehood would bring; indeed, even before a general consensus was found concerning what role the free black man should have in a nonslave-holding society. The thirty-five delegates who were given the charge to decide on the fundamental

5. Ibid. 6. Ibid.; see also Barnhart, "Southern Influence in Ohio," 38-39, 42. 7. Quillin, Color Line in Ohio, 18. |

|

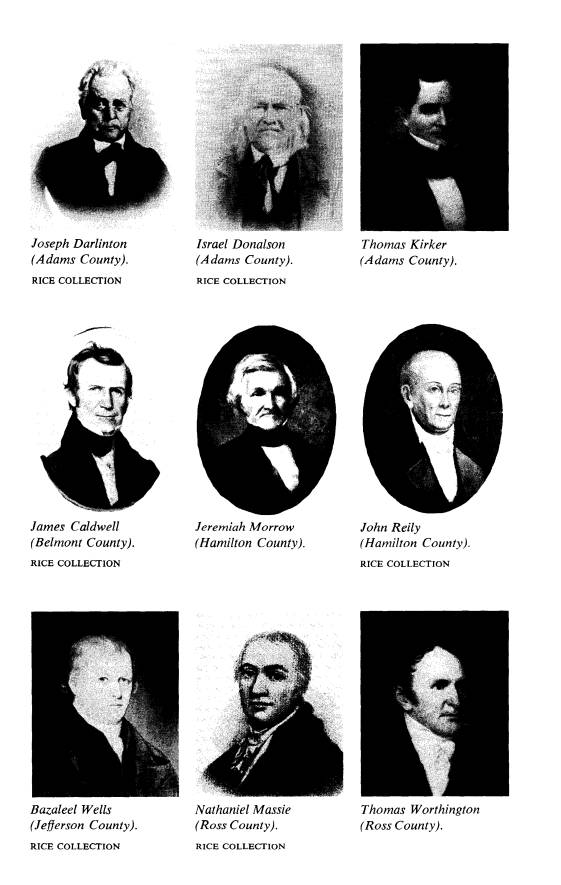

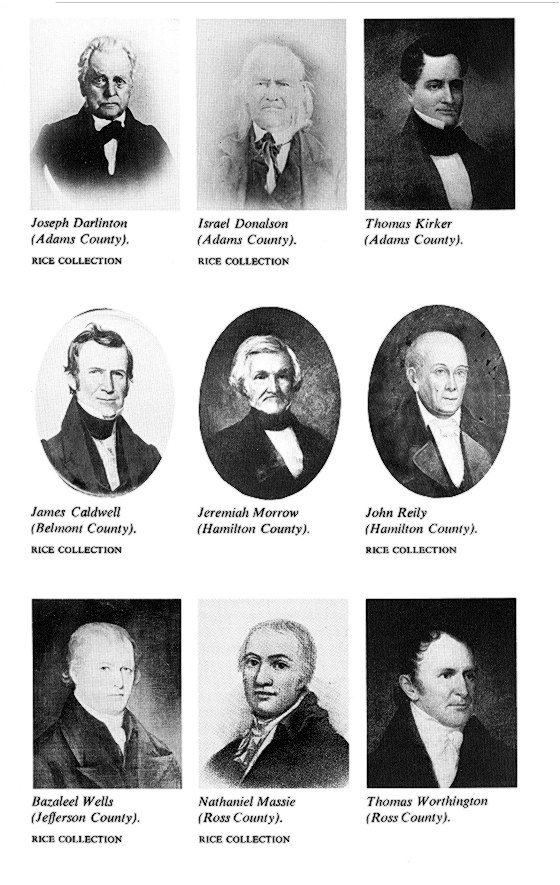

aspects of the Ohio constitution were as follows in alphabetical order by county: Adams: Joseph Darlinton, Israel Donalson, Thomas Kirker Belmont: James Caldwell and Elijah Woods Clermont: Rev. Philip Gatch and Joseph Sargent Fairfield: Henry Abrams and Emanuel Carpenter Hamilton: Rev. John W. Browne, Charles Willing Byrd, Francis Dunlavy, Dr. W. Goforth, John Kitchel, Jeremiah Morrow, John Paul, John Reily, Rev. John Smith, John Wilson Jefferson: Rudolph Bair, George Humphrey, John Milligan, Nathan Updegraff, Bazaleel Wells Ross: Michael Baldwin, James Grubb, Nathaniel Massie, Dr. Edward Tiffin (president of the convention), Thomas Worthington Trumbull: David Abbot, Samuel Huntington Washington: Ephraim Cutler, Benjamin Ives Gilman, John McIntire, Rufus Putnam As soon as the delegates convened, various committees were appointed to write specified portions of the constitution. Under the rules adopted each article and sec- tion, before it was deemed to be passed, was to be given three general readings before the convention as a whole, thereby allowing opportunity for change and/or compromise.8 On November 4 a committee of nine was appointed to prepare a bill of rights. Six of the nine counties were represented on this important committee:9 Hamilton County by Goforth (antislavery, pro-negro), Dunlavy (ultra pro-negro), and Browne (antislavery, pro-negro)

8. An easily accessible copy of the journal of the first constitutional convention is in Ohio Archaeological and Historical Publications (1897), V, 80-132. See also Journal of the Con- vention of the Territory of the United States North-West of the Ohio (Chillicothe, 1802). 9. Ohio Historical Publications, 90. |

|

Ross County by Baldwin (anti-negro) and Grubb (anti-negro) Belmont County by Woods (anti-negro) Jefferson County by Updegraff (antislavery, pro-negro) Washington County by Cutler (antislavery, pro-negro) Adams County by Donalson (anti-negro) The designations of voting characteristics are derived from the votes taken on the eight vote counts given in the journal of the proceedings of the convention. (See Voting Chart One for biographical data and voting record.) To be "antislavery, pro-negro" a delegate would have voted for the qualifications in the antislavery motions on votes I and IX as well as pro-negro on votes VI and VII, the suffrage and "citizen rights" motions. To be "ultra pro-negro" a delegate would have voted for the interest of the negro on the suffrage and "citizen rights" motions but against the qualifications in the antislavery section of the bill of rights article in votes I and IX. The general statement against slavery in section one of the article, in their estimation, apparently did not need special restrictions for either whites or negroes. To be "anti-negro" (but not necessarily pro-slavery) the delegate would have voted against the negro on suffrage vote VI, the "citizen rights" vote VII, and the antislavery |

Ohio Constitutional Convention 21

vote IX. Two categories, the

"anti-slavery, anti-negro" and "independent" groups

were not represented on the bill of

rights committee. To have the first designation

the delegate would have voted pro-negro

on the antislavery votes I and IX but against

him on the suffrage and "citizen

rights" votes VI and VII. On the basis of these

designations, it can be seen that the

bill of rights committee members were pro-negro

by a five to four margin but were

divided four to five on the anti-slavery votes, because

Dunlavy did not vote with the

antislavery delegates on votes I and IX.

On Saturday, November 20, 1802, the bill

of rights Article Eight was reconsidered

after a first reading on November 11.

Only one clause was challenged in section two

at this time. There was no debate on the

first part of the section that read, "There

shall be neither slavery nor involuntary

servitude in this State, . . ." but there was a

motion to strike out the qualifying

phrase following which read, "nor shall any male

person arrived at the age of twenty-one

years, or female person arrived at the age of

eighteen years, be held to serve any

person as a servant under pretense of indenture or

otherwise, unless such shall enter into

such indenture, while in a state of perfect

freedom, and on condition of a bona fide

consideration, received or to be received

for their service, except as before

excepted."

From the convention journal we do not

know who introduced the motion to strike

out the above clause or what arguments

were presented; we know only that the motion

was defeated twenty-one to twelve (vote

I).10 The motion is considered here to be

"anti-negro" because it was

resisted by such outspoken antislavery leaders as Rev.

Gatch, Dr. Goforth, Thomas Worthington,

Ephraim Cutler, and Rufus Putnam. The

intent of the section seems to be an

expansion on the general prohibition against

slavery to specifically include the

designated restrictions. The fear often expressed

during the pre-convention campaign was

that those who wished to have slavery would

use a disguised form of indenture for

this purpose. The specific wording of the

provision seems to be an extra safeguard

against this type of servitude.11

Those voting in the affirmative (for

removal) were: Abbot, Bair, Caldwell,

Dunlavy, Grubb, Kitchel, Morrow, Paul, Reily, Sargent, Smith, and

Wilson (12).

Those voting in the negative (against

removal) were: Abrams, Baldwin, Browne,

Byrd, Carpenter, Cutler, Darlinton,

Donalson, Gatch, Gilman, Goforth, Humphrey,

Huntington, Kirker, Mclntire, Milligan,

Putnam, Updegraff, Wells, Woods, and

Worthington (21). Tiffin abstained.

(Italics indicate bill of rights committee mem-

bers.)

After this vote was taken, other

portions of the twenty-six section bill of rights

article were debated, but adjournment

was called before work was completed. On the

following Monday, November 22, before

further consideration of Article Eight was

allowed, the decision had to be made on

the question of elector qualifications, as

defined in Article Four. Those delegates

on the committee designated to decide

on the qualification of electors were:

Morrow, chairman (independent), Paul

(ultra pro-negro), Kirker (antislavery,

anti-negro), Grubb (anti-negro), and Bair

(anti-negro) 12

10. Ibid, 95, 110-111.

11. See statements of the candidates from Ross County in Scioto

Gazette, August 28, Sep-

tember 4, 11, 18, 25, October 2, 1802,

for examples of pro and antislavery sentiment. For

Jefferson's ideas on race and his

possible influence on the Ohio delegates, see Winthrop D. Jor-

don, White over Black: American Attitudes

Toward the Negro, 1550-1812 (Chapel Hill, 1968),

429-481.

12. Ohio Historical Publications, 95.

22 OHIO HISTORY

Apparently the anti-negro majority on

the committee prevailed in the wording of

section one, which followed the

precendent established during the territorial period,

in stating: "In all elections, all

white male inhabitants above the age of twenty-one

years ... shall enjoy the right of an

elector." A motion was made to strike out the

word "white" after the word

"all," giving the vote to all male inhabitants who other-

wise were qualified. Those who wished

for all males to be given the right to vote

were defeated nineteen to fourteen (vote

II).13

Delegates voting in the affirmative (for

all males) were: Browne, Cutler, Dunlavy,

Gatch, Gilman, Goforth, Grubb, Kitchel,

Paul, Putnam, Sargent, Updegraff, Wells,

and Wilson (14).

Those voting in the negative (against

the negro)were: Abrams, Baldwin, Bair,

Byrd, Caldwell, Carpenter, Darlinton,

Donalson, Humphrey, Huntington, Kirker,

Mclntire, Massie, Milligan, Morrow, Reily,

Smith, Woods, and Worthington (19).

Tiffin abstained. (Italics indicate

elector qualification committee members.)

Those favoring giving the vote to the

negro tried again a short time later the same

day and introduced a proviso to be

included at the end of Article Four that would

read: "Provided that all male

negroes and mulattoes now residing in the territory

shall be entitled to the right of

suffrage, if they shall within ____ months make a

record of their citizenship."

Surprisingly, this proviso passed by a nineteen to fifteen

margin (vote III).14

Affirmative ballots were cast by: Abbot,

Byrd, Cutler, Darlinton, Dunlavy, Gatch,

Gilman, Goforth, Grubb, Kitchel, Morrow,

Paul, Putnam, Reily, Sargent, Smith,

Updegraff, Wells, and Wilson (19).

Voting negatively were: Abrams, Baldwin,

Bair, Browne, Caldwell, Carpenter,

Donalson, Humphrey, Huntington, Kirker,

McIntire, Massie, Milligan, Woods, and

Worthington (15). Tiffin abstained.

Having won this concession for negro

voting rights, a further motion was imme-

diately introduced for the proviso to

read: "And provided also, That the male

descendants of such negroes and

mulattoes as shall be recorded, shall be entitled to

the same [voting] privilege." This

time the pro-negro forces were defeated by a

seventeen to sixteen majority (vote

IV).15

Those voting yea (for the proviso) were:

Browne, Byrd, Cutler, Darlinton, Dun-

lavy, Gilman, Goforth, Grubb, Kitchel,

Morrow, Paul, Putnam, Sargent, Updegraff,

Wells, and Wilson (16).

Those voting nay (against the proviso)

were: Abbot, Abrams, Baldwin, Bair,

Caldwell, Carpenter, Donalson, Humphrey,

Huntington, Kirker, Mclntire, Massie,

Milligan, Reily, Smith, Woods, and

Worthington (17). Gatch and Tiffin did not

vote on this motion but they did vote on

the final motion in this series, vote VI.

Shortly after this vote was taken, a

motion was entered to amend the Seventh

Article, comprehending the general

regulations and provisions of the constitution, by

adding a new section to be section

seven. It read as follows: "Section 7. No negro

or mulatto shall ever be eligible to any

office, civil or military, or give their oath in

any court of justice against a white

person, be subject to do military duty, or pay a

poll-tax in this State; provided always,

and it is fully understood and declared, that

all negroes and mulattoes now in, or who

may hereafter reside in, this State, not

13. Ibid., 113.

14. Ibid., 114.

15. Ibid.

Ohio Constitutional Convention 23

excepted by this constitution."16

This anti-negro motion limiting

"citizen rights" passed nineteen to sixteen (vote

V).17 Those voting yes (for

the new section) were: Abrams, Baldwin, Bair, Byrd,

Caldwell, Carpenter, Darlinton,

Donalson, Grubb, Humphrey, Kirker, McIntire,

Massie, Milligan, Morrow, Smith, Tiffin,

Woods, and Worthington (19).

Those voting no (against the new section)

were: Abbot, Browne, Cutler, Dunlavy,

Gatch, Gilman, Goforth, Huntington,

Kitchel, Paul, Putnam, Reily, Sargent,

Updegraff, Wells, and Wilson (16).

By the end of the day of Monday,

November 22, the constitution contained a

section permitting resident negroes and

mulattoes to vote, but another severely

restricted their rights as freemen. This

apparent contradiction was not considered

again until Friday, November 26, three

days before adjournment of the convention.

That day a motion was made to reconsider

Article Four in regard to the qualification

of electors. The motion asked to have

the proviso removed giving resident negroes

and mulattoes the vote that had passed

by a nineteen to fifteen margin on November

22. This time the vote was a seventeen

to seventeen tie. The president of the con-

vention, Edward Tiffin, then cast his

vote for removal of the proviso (vote VI).18

According to historian Daniel Ryan,

Tiffin's reason for vetoing the motion was that

"the close proximity of two

slave-holding states--Kentucky and Virginia--made

it undesirable to offer such an

inducement for the emigration of negroes and

mulattoes."19

Those voting yes (for removal) were:

Abrams, Baldwin, Bair, Caldwell, Carpenter,

Darlinton, Donalson, Grubb, Humphrey,

Huntington, Kirker, McIntire, Massie,

Milligan, Smith, Tiffin, Woods, and

Worthington (18).

Those voting no (against removal) were:

Abbot, Browne, Byrd, Cutler, Dunlavy,

Gatch, Gilman, Goforth, Kitchel, Morrow,

Paul, Putnam, Reily, Sargent, Updegraff,

Wells, and Wilson (17).

In regard to the four motions dealing

with the question of negro suffrage, we find

that eleven delegates voted consistently

pro-negro (Sargent, Dunlavy, Goforth,

Kitchel, Paul, Wilson, Updegraff, Wells,

Cutler, Gilman, and Putnam, representing

Clermont, Hamilton, Jefferson, and

Washington counties); that fifteen voted con-

sistently anti-negro (Donalson, Kirker,

Caldwell, Woods, Abrams, Carpenter, Bair,

Humphrey, Milligan, Baldwin, Massie,

Worthington, Tiffin, Huntington, Mclntire,

representing Adams, Belmont, Fairfield,

Jefferson, Ross, Trumbull, and Washington

counties); and that nine voted

differently, depending upon the specific issue

(Darlinton, Gatch, Browne, Byrd, Morrow,

Reily, Smith, Grubb, and Abbot, repre-

senting Adams, Clermont, Hamilton, Ross,

and Trumbull counties). It is difficult

to make clear-cut geographic

generalizations concerning the attitudes in the different

counties in regard to the question of

negro suffrage because of the lack of unanimity

within a particular county delegation.

All that can be said is that anti-negro sentiment

was more widespread throughout the

territory than was support for negro suffrage,

which was strongest in Hamilton and

Washington counties.

The voting of the nine delegates who

voted inconsistently is significant not only

because the final wording of the

constitution was determined by them, but also

16. Ibid., 115.

17. Ibid., 116.

18. Ibid., 122.

19. Ryan, History of Ohio, 118.

24 OHIO HISTORY

because they illustrate the wide

spectrum of opinion concerning the suffrage issue

prevalent at the time. Darlinton's anti,

pro, pro, anti vote appears to mean that he

at first supported the limited vote for

resident negroes but not general suffrage and

then later withdrew his support

altogether, perhaps under pressure from his other

colleagues from Adams County. Gatch's

pro, pro, absent, pro vote is strongly

pro-negro but is uncertain on vote IV.

It is difficult to say why this vote would have

been harder for him to support than vote

II, which would have also given suffrage

to the negro.

Browne's pro, anti, pro, pro vote is

strongly pro-negro, and his anti vote on III

tends to strengthen rather than weaken

his position if he was insisting on full equality

for the negro.20 Byrd's anti,

pro, pro, pro vote indicates a change from anti-negro

to full support for equal voting rights,

as does Morrow's similar record, but their

wills did not change enough votes to

their side to be successful. Reily's anti, pro, anti,

pro vote shows him consistently

supporting the limited franchise and against full

equality. Smith's anti, pro, anti, anti

vote shows him to be against full equality and

only half-heartedly supporting the

limited franchise. Grubb's pro, pro, pro, anti vote

shows him to have changed his vote,

possibly to be in accord with the prevailing

anti-negro sentiment of his Ross County

delegation.21 Abbot's absent, pro, anti, pro

vote, on the other hand, could indicate

that he was struggling to resist the anti-suffrage

voting of his powerful colleague

Huntington.

Since the anti-negro forces needed three

votes to have a majority, how did they

succeed in winning on vote VI? By breaking

down the nine vascillating votes into

specific categories, the answer can be

readily found. The three divisions into which

the nine delegates fall are: (1) yield

to anti-negro pressure, (2) yield to pro-negro

pressure, and (3) move without changing

the result. We find two delegates (Darlinton

and Grubb) yielding to anti-negro

pressure, two (Morrow and Byrd) yielding to

pro-negro pressure, and five voting both

pro and anti but ending in the same position

as they started (Smith anti, and Gatch,

Browne, Reily, and Abbot pro). The final

count is as follows: pro-negro (11 + 2 +

4) 17 and anti-negro (15 + 2 + 1) 18.

Therefore we see that the convention on

the suffrage issue was actually divided

fifteen pro-negro, sixteen anti-negro,

with four undecided votes, two finally going

to the pro-negro side and two to the

anti-negro--which it turned out were all they

really needed.

The fact that the anti-negro forces

needed four motions before they could maintain

a bare majority of eighteen indicates

the degree of persistence the pro-negro delegates

exerted in their efforts to give equal

voting rights to all qualified males in the state. In

the end, however, the resident negro and

mulatto were denied the vote, as well as their

20. Ephraim Cutler made the claim that

Browne tried to introduce slavery by using the in-

denture ruse. Cutler, Cutler, 74-76.

Browne's voting record, however, seems to contradict this

claim, as does his antislavery statement

made in 1806: "[Slavery] will have a most pernicious

effect upon the manners, the habits, and

the morals of the inhabitants of the territories.... The

effect, therefore, will be, to make the

whites indolent, and as their ultimate prosperity must

depend upon themselves, to destroy those

habits of industry on which alone that prosperity can

rest." Liberty Hall and

Cincinnati Mercury, March 31, 1806.

21. According to a letter written by

Duncan McArthur, a prominent Republican from Ross

County to Thomas Worthington on January

17, 1803, Darlinton lost his bid for the Ohio senate

by seven votes and James Grubb

"lost much credit" because of their "negro votes."

Apparently

their switches to an anti-negro position

came too late to satisfy their constituents. Microfilm of

letter in the Manuscript Division of the

Ohio Historical Society. Before the election of delegates

to the convention Grubb had run on the

following antislavery declaration: "I conceive it [slavery]

bad policy, and the principle cannot be

advocated by any person of humane or republican senti-

ments." Scioto Gazette, September

11, 1802.

Ohio Constitutional Convention 25

children. Thus a precedent was

established to set the black population apart from

white residents and to make special laws

that would apply exclusively to them. Also,

the importance of the "close

proximity of two slave-holding states" should not be

minimized. One of the first pieces of

business taken up by the second session of the

General Assembly in 1803 relating to

negroes was motivated by fear of possible

inter-state "trouble"

resulting from requests for the return of out-of-state slaves that

had fled into Indian lands (Wayne

County).22

After the question of negro suffrage had

been settled at the convention, reconsidera-

tion of section seven, Article Seven,

which had been added by a nineteen to sixteen

count on vote V, was shortly taken up. A

motion was made to strike it out. This

passed by a seventeen to sixteen margin

(vote VII). Another effort was made

immediately to add another section seven

that was worded simply: "No negro or

mulatto shall ever be eligible to any

office, civil or military, or be subject to.military

duty," omitting the prohibition

against giving "their oath in any court of justice

against a white person," or paying

"a poll-tax in this State .. ." When the president

asked, "Shall the main question be

now put?" the motion was denied consideration

by an unrecorded vote (vote VIII).23

Section seven of Article Seven was not added

to the constitution, giving the

pro-negro forces a victory, but one that was to be

short-lived, considering the restrictive

laws against negroes which were passed in

1803, 1804, and 1807 by some of the same

lawmakers who had drawn up the

constitution.

Those voting yes (for removal) were:

Abbot, Browne, Cutler, Dunlavy, Gatch,

Gilman, Goforth, Huntington, Kitchel,

Milligan, Paul, Putnam, Reily, Sargent,

Updegraff, Wells, and Wilson (17).

Those voting no (against removal) were:

Abrams, Baldwin, Bair, Byrd, Caldwell,

Carpenter, Darlinton, Donalson, Grubb,

Humphrey, Kirker, Massie, Morrow, Smith,

Woods, and Worthington (16). Tiffin and

Mclntire did not vote.

Those changing their votes on section

seven in Article Seven are Milligan (inde-

pendent), who voted for the restrictions

on vote V but against them on vote VII;

Tiffin (independent), who also voted for

the restrictions on vote V but abstained

on vote VII; and McIntire (independent),

who voted as Tiffin. Thus we see that in

a rather subtile way the change of one

anti to pro-negro vote and the absentions of

two delegates who at first had voted

anti-negro saved the constitution from being

more restrictive for negroes than it

finally became. It should be noted that even

though restrictions were not designated

in the constitution, specifications of "citizen

rights" for negroes and mulattoes

were likewise omitted, and the status of the negro

was thereby left vague.

The last major consideration of the

constitution itself was taken up on the same

day, Friday, November 26. It again

concerned Article Eight, the bill of rights sections.

A successful attempt was made to make

section two even more emphatically anti-

slavery that the bill of rights

committee had intended.

As has been stated, this section had

been written originally to categorically state

there shall be no slavery or involuntary

servitude in Ohio. This statement had passed

without question. The next clause

prohibiting any pretense of indenture was chal-

lenged but was retained intact (vote I).

Now a motion was made to change the

second sentence prohibiting

"any" indenture made "out of the State" to read any

indenture "of any negro or

mulatto," leaving the other terms "of one year of service"

22. Journal of the House of

Representatives, Ohio, Second Session, 1803-1804, II, 37-38.

23. Ohio Historical Publications, 124-25.

26 OHIO HISTORY

and "for the purpose of

apprenticeship" to stand. By specifying that negroes or

mulattoes could not be held by indenture

for more than one year, it can be argued

that the antislavery forces were further

reinforcing the general provision that "There

shall be neither slavery or involuntary

servitude" in Ohio.

Winthrop Jordan points out in his

historical study of slavery that since 1611 the

custom had been established that

indenture was not the same as slavery since

indenture was only for a specified time

period and that slavery meant servitude for

the lifetime of the individual.24 Therefore,

the time limitation of one year for negroes

and mulattoes could be considered the

important antislavery aspect of this restriction.

It can also be argued, however, that

"indenture" was a term commonly used for white

servile labor and that if negroes were

allowed to enter into this relationship for one

year in the capacity of an apprentice,

the inclusion might be construed to be too

pro-negro by some of those voting

against it. Or another way of considering this

provision could be that

"indenture" was only a cover-up for servitude, but for less

duration than lifetime slavery, and

would therefore be anti-negro and would be

opposed by the ultra pro-negro

delegates. But considering the context within which

the bill of rights was enacted, it can

be assumed that for a majority of the delegates

the inclusion of "negro or

mulatto" is a second statement emphasizing the prohibition

of slavery in any form, especially for

blacks. This provision passed by a twenty to

thirteen margin (vote IX).25

Those voting yes (for inclusion) were:

Abbot, Browne, Byrd, Caldwell, Carpenter,

Darlinton, Gatch, Gilman, Goforth,

Humphrey, Huntington, Kirker, Kitchel, Massie,

Morrow, Putnam, Smith, Updegraff, Wells,

and Worthington (21).

Those voting no (against inclusion)

were: Abrams, Baldwin, Bair, Donalson,

Dunlavy, Grubb, Mclntire, Milligan, Paul, Reily, Sargent, Wilson and Woods

(13).

Cutler and Tiffin abstained.

The votes of Dunlavy, Sargent, Paul, and

Wilson on the negative side in votes I

and IX are not considered in this

analysis to be anti-negro, but to be liberal in the

extreme (ultra pro-negro). Their votes

could indicate they believed "no slavery"

meant just that and the term itself was

all-inclusive, needing no clarification. The con-

sistent votes of these delegates for

suffrage and against restricting "citizen rights"

for negroes indicate they did not share

the feeling of the convention that negroes

needed to be dealt with separately from

whites. A biographer of Dunlavy describes

the Baptist educator as follows:

"Being a member of the first Constitutional Con-

vention of Ohio, he was one of those who

advocated the most liberal civil, religious

and political privileges for all

citizens, of whatever name, country, color or religion."26

11

On the basis of the vote count for the

various provisions of the constitution directly

affecting the negro, what can be

determined overall as to the relative strengths of the

pro-negro and anti-negro forces? Was the

convention divided on other issues in the

same ratio as on the suffrage vote VI?

What factors were influential in the decision-

making?

24. Jordan, White over Black, 62-63.

25. Ohio Historical Publications, 125-26.

26. A. H. Dunlevy, History of the

Miami Baptist Association . . . With Short Sketches of De-

ceased Pastors of this First

Association in Ohio (Cincinnati,

1869), 157. Italics added to indicate

there were more than just Dunlavy voting

for liberal issues at the convention.

|

Ohio Constitutional Convention 27

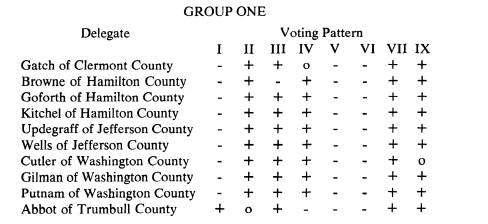

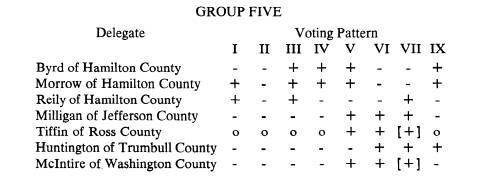

The relative strengths of the various points of view represented by the delegates can be determined by isolating the voting patterns that are alike or very nearly similar. As indicated previously, the delegates can be divided into five distinct groups depending upon how they voted on the antislavery, suffrage, and "citizen rights" issues: (1) antislavery, pro-negro; (2) ultra pro-negro; (3) antislavery, anti-negro; (4) anti-negro; and (5) independent. The following ten delegates representing five counties can be considered to be in antislavery, pro-negro group (1): |

|

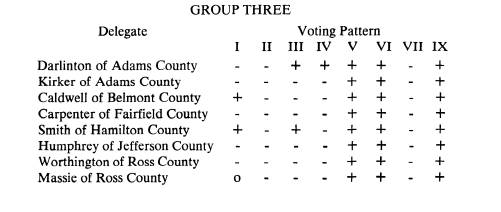

The important votes in the antislavery, pro-negro category are pro-negro votes for I, VI, VII, and IX. The only exceptions to this pattern are Cutler's abstention on vote IX and Abbot's vote on I. Since these two votes do not seem to change the pattern of the delegate's voting, they are not considered to be especially significant for classification purposes. On vote IV, if Gatch had voted pro-negro, the showdown would have come sooner on the suffrage issue, but the outcome probably would not have been different as far as Tiffin was concerned. The following four delegates representing two southern counties and having an identical voting pattern ( + + + + - - + - ) can be considered to be in ultra pro-negro group (2): Sargent from Clermont County and Dunlavy, Paul, and Wilson from Hamilton County. The following eight delegates representing six counties can be considered to be in antislavery, anti-negro group (3): |

|

28 OHIO HISTORY

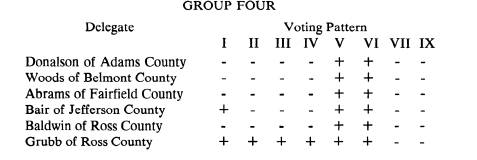

The important votes in the antislavery, anti-negro group are pro-negro ballots on I and IX and anti-negro votes on VI and VII. Exceptions to this pattern can be seen in I for Caldwell, Smith and Massie, but since their vote IX is within the target, the first vote is not considered significant for classification purposes. Group (4), the anti-negro category, contains six delegates representing five counties: |

|

|

|

The important votes in this category are the final consideration anti-negro votes VI, VII, and IX, with no other consistent pro-negro or antislavery votes that would put the delegate in the independent group. Donalson, Woods, Abrams, and Baldwin have pro-negro votes on I, but their other key votes are negative so it seems reasonable to assume vote I implies personal reasoning difficult to understand from the record alone. Grubb's voting pattern is interesting because of his three pro-negro votes on II, III, and IV. As has been suggested, he may have changed his final vote to support his colleagues on the suffrage issue. The most obvious characteristic of independent group (5) is the seemingly contra- dictory voting behavior displayed. On one issue the delegate may be pro-negro but on others will be anti-negro. There are seven delegates in this category, representing five counties. |

|

|

|

One observation that can be made from the voting patterns of the independent delegates is that even though they were not in total agreement with one another, they were not especially antagonistic either; they seem to be leaderless. Morrow, for example, appears inconsistent in his antislavery votes I and IX, is consistent in his limited suffrage support on III and VI, but is anti-negro on his "citizen rights" votes V and VII. Huntington's record shows him to be voting anti-negro on the suffrage motions, but is consistently pro-negro on antislavery and "citizen rights." An explana- tion for the latter vote could be that he did not wish the specific restrictive measures |

Ohio Constitutional Convention 29

to be included in the constitution for

legal reasons rather than for any reasons directly

connected with race.27

We see that only Milligan and Mclntire

have similar voting patterns, but this

could be merely coincidental. According

to Ephraim Cutler, he was personally

responsible for Milligan's change from

anti to pro-negro on vote VII. This was the

deciding vote that kept the restrictions

on the "citizen rights" for negroes out of the

constitution. Cutler's version of the

scene is as follows:

On one occasion, when it [Article Seven]

was before the committee of the whole con-

vention, a material change was

introduced.... I went to the convention and moved

to strike out the obnoxious matter

[section seven]. . . . Mr. Mclntire was absent that

day, so there would be a tie, unless we

could bring over one more. Mr. Milligan had, in

the territorial legislature, spoken

against slavery, but in the convention had voted with

the Virginia party. In the course of my

remarks, I happened to catch his eye, and the

very language he had used in debating

the question occurred to me. I put it home to him,

and when the vote was called Mr.

Milligan changed his vote, and we succeeded in placing

the section in its original form ... it

passed by a majority of one vote only.28

The voting record for Reily, yet another

independent, shows him to be in favor

of limited suffrage and "citizen

rights," as indicated by votes III, V, VI, and VII.

On the other hand, he is anti-negro on

the full suffrage and antislavery issues I, II,

IV, and IX.

With the five major voting categories in

mind, what can be said now about the

relative strengths of pro-negro,

anti-negro, antislavery, and independent groups?

It follows from the preceeding discussion that the minimum number of

pro-negro

votes can be determined to be 14 (10

as/pn + 4 pn); the anti-negro votes to be

14 (8 as/an + 6 an); the antislavery

votes to be 18 (8 + 10); and the independent

votes to be 7. It can be readily seen

why the antislavery provisions of the constitution

passed easily and why the suffrage and

"citizen rights" votes were hard fought.

Neither side on these issues had a

majority and therefore each needed to persuade

some of the independent delegates to its

side.

The inconsistencies on the part of the

independents seem to indicate the presence

of conflicting motivations. What factors

were influential in the decision-making of

these men, and for the delegates as a

whole, is a matter of some concern in a study

of the basic document of the state. It

would be helpful in our understanding of the

racial attitudes of the time if

significant relationships could be found between the way

a delegate voted and his political

party, region of origin, age, or position (leadership).

For the state scene Chart One indicates

that all the counties represented sent some

delegates that voted both pro-negro and

anti-negro depending upon the specific

issue. Therefore county of origin is not

a good indication of voting attitude.

Whether or not significant relations

existed between certain other designated factors

27. If Huntington's was a precautionary

measure aimed at making the Ohio constitution ac-

ceptable to Congress, it was apparently

successful. Worthington's report to Nathaniel Massie on

December 25, 1802, from Washington, D.

C., on the progress he was making toward getting the

constitution accepted was optimistic:

"Our friends appear highly pleased with the proceedings

in our quarter & so far appear

heartily disposed to render every attention to our affairs-Our

business is before a committee of

congress and I hope will very soon pass through.... Our friends

here are generally well pleased with our

constitution." David Meade Massie, Nathaniel Massie,

A Pioneer of Ohio: A Sketch of His

Life and Selections from His Correspondence (Cincinnati,

1896), 220.

28. Cutler, Cutler, 76-77.

Mclntire was absent on only the one vote that day. Had Tiffin chosen

to do so, a tie could have resulted with

his vote also.

30 OHIO

HISTORY

and the voting can be determined by

using additional records available. The

biographical information in the voting

charts is based on research done by Charles E.

Rice in the late 1800's on the vital

statistics of the members of the constitutional

convention. He compiled his data from

court records, obituaries, and accounts by

members of the immediate families and

thereby determined as accurately as can now

be done the age and origin of each

delegate. Since a person often moved from his

original home, his location of longest

domicile is used for this study. The work done

by John D. Barnhart is utilized in

instances of questionable location and political

party.29 (See Voting Chart

One for full details.)

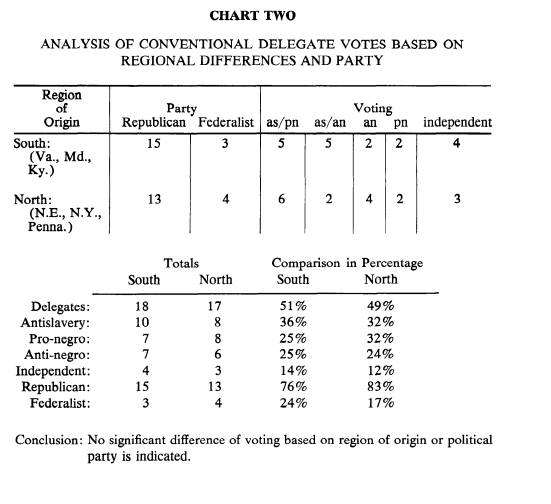

From Chart Two it can be seen that the

delegates were about evenly divided in

terms of the total numbers from the two

regions of the country (17-18) and that the

two political parties were about equally

represented in delegates from the North and

South; thus the voting shows no

significant difference based on region of origin or

political party.

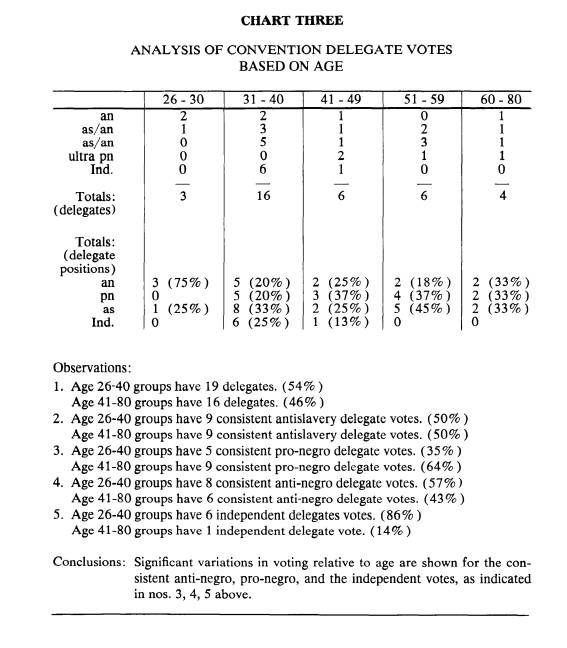

There does, however seem to be some

differences in the voting patterns relative

to the age of the delegate. From Chart

Three we see that all of those person below

age thirty are anti-negro; also, eight

of the fourteen anti-negro delegates, no ultra

pro-negro delegates, and only five of

the fourteen pro-negro votes are in the younger

group. Likewise significant is the fact

that six of the seven independent delegates

are between thirty-one and forty-one.

The most tolerant age is between fifty-one and

fifty-nine. These are the men who fought

for American independence from the

British; the least tolerant are the age

of their sons.

Before one jumps to the conclusion that

there was a "generation gap" at the

convention, one should look to see if

there were off-setting mavericks. Are there

young delegates voting liberal or old

voting conservative? A closer look at the

voting on suffrage vote VI shows that

seven in the forty-one to eighty age bracket

voted anti-negro with the eleven young

conservatives and that eight in the twenty-six

to forty-one group voted with the nine

older liberals. (See Voting Chart One.) Thus,

even though there were differences

related to age on some issues, these differences

were partly cancelled out on the

suffrage vote: voting was thirty-nine percent to

sixty-one percent older to younger

against suffrage; but those voting pro-negro for

suffrage were almost equally divided in

terms of age. Apparently for the younger

delegates who voted for suffrage, other

factors than age were exerting an undue

pro-negro influence on them.

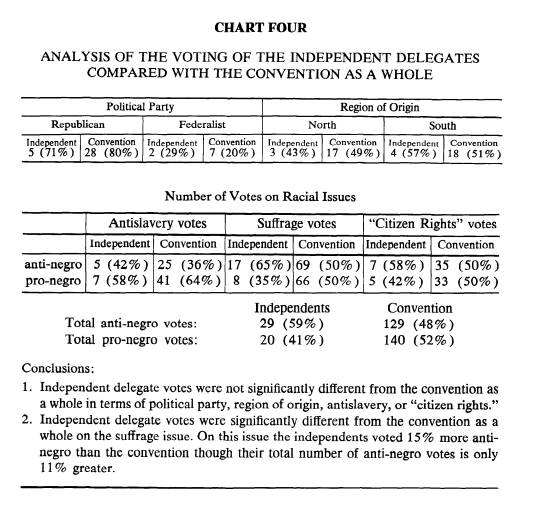

Whether or not the independents had a

decisive influence on the voting can be

determined from a study of their record.

A breakdown of the votes for the seven

independent delegates compared with

those of the convention as a whole gives a

clear picture of the distribution of the

pro-negro and anti-negro sentiment and whether

or not the independents were exerting

special leadership at the convention. One way

of determining their strength would be

to see if the vote of the whole convention

was the same or significantly different

from that of the independents. Or, if the

independents were divided into opposing

factions, then a weakening of their influence

as a group would be indicated.

From Chart Four it can be seen that

there were internal divisions within the

independent group, indicated by the

fluctuating percentage on the three issues, and

that in two respects their votes were

significantly different from those of the con-

(continued on page 34)

29. Clarence E. Rice Collection, Box 20,

Ohio Historical Society; Barnhart, "Southern In-

fluences in the Formation of Ohio,"

28-42.

|

vention as a whole. These areas are those on suffrage and on the totals for the anti-negro and pro-negro vote. These inconsistencies and the closeness of the final suffrage vote (vote VI, 17-18) seem to confirm the presence of a competing strong pro-negro leadership outside the independent group, Cutler and Putnam, for instance. Even so, neither this leadership nor the anti-negro faction within the independent group was strong enough to be dominant in critical situations. It thus became neces- sary to attract less prominent members of other factions at the last moment to cast deciding votes--Grubb and Darlinton in the case of the anti-negro vote on suffrage, and Milligan on the pro-negro vote on "citizen rights." The conclusion then, based on the voting analyses presented, is that there was no |

|

one clearly dominant leadership faction at the constitutional convention. There were, instead, off-setting extremes in points-of-view with an unorganized independent group (Byrd, Morrow, Tiffin, and Milligan) supplying crucial votes on close issues. It has been shown that there were at least four discernible voting patterns suggesting differing attitudes in response to the three race questions considered. The general lack of correlating factors and the instance showing both positive and negative relationship with age indicate that what prompted a particular delegate to take any given stand seems to have been an individual matter which was not necessarily related to political party, region of origin, age, or the consistent dominance of any one leader. Thus, determining the complexities involved in the motivations of the delegates demands more than isolating simple one to one relationships and would be most difficult to do at this late date.

III Since the constitution did not fully define the status of negroes and mulattoes, a further word should be said on this matter. In the first place, the military restrictions on the negro that were voted down in the convention were, in effect, enacted into law on December 5, 1803, by the second session of the General Assembly. The state |

36 OHIO HISTORY

law passed then was in accordance with

federal law of 1792 and used the same

wording: "each and every free,

ablebodied white male citizen of the state . . shall

be enrolled in the militia.. .."30 In the same session the legislature passed the

"Act

to regulate blacks and mulatto

persons." Initiated in the house, this bill was intro-

duced immediately after defeat of the

resolution, mentioned earlier, that called on

the President of the United States to

help Ohio return out-of-state slaves who had

fled into Indian lands. The 1804 bill,

as finally amended, passed nineteen to eight

in the house and nine to five in the

senate, Kirker and Massie voting for it and

Milligan and Sargent voting against. The

bill detailed how negroes coming into the

state would be regulated and enumerated

the penalties for those persons aiding

them without the required court seal on

their certificates of freedom. Penalties

ranged from ten to one thousand dollars,

one-half to be paid to the informer and

one-half to the state. The 1807 bill

increased the restrictions, including the require-

ment of a $500 surety bond, and

prohibited negroes and mulattoes from giving

testimony in court cases involving white

persons.31

The constitutional convention delegates

in the General Assembly in 1803 were

as follows; Kirker (as/an), Woods (an),

Sargent (ultra pn), Dunlavy (ultra pn),

Morrow (I, pn), Paul (ultra un), Smith

(as/pn), Bair (an), Milligan (I, an), Wells

(as/pn), Baldwin (an), Massie (as/an),

Worthington (as/an), Huntington (I, an),

and Tiffin, governor (I, an). Total

anti-negro assemblymen was eight and total

pro-negro was six. (Designation of

"an" for the independents is based on the largest

number of votes cast.) It should be

noted, however, that only the four senators

mentioned in connection with the

1803-1804 legislation and Governor Tiffin were in

the second session when the militia and

restrictive laws were passed. Those delegates

still serving in the legislature by 1807

were: Woods (an), Massie (as/an), Worth-

ington (as/an), Kirker (as/an), and

Tiffin still as governor, all rated as anti-negro.

One important difference between the

1804 and 1807 laws is that the latter

included the provision against testimony

in court that had been originally defeated

at the convention. It is also apparent

that only anti-negro delegates were carried in

the Assembly until the 1807 period,

possibly indicating that the Ohio population as

a whole was becoming more anti-negro as

the responsibilities of being a neighbor to

slave states increased.

In conclusion, it can be said from this

look at the constitutional convention of 1802

that the negro was to be free in Ohio

but was not able to vote even though he was

not otherwise restricted. This

relatively unhampered state did not last long, however.

By means of laws passed in 1803, 1804,

and 1807 the restrictions that were not

passed at the convention were legalized

and others added. Under these laws basic

freedom from slavery was not

jeopardized, but the laws seem to be one legalistic

method used by the leaders of the new

state to avoid border "trouble" on account

of conflicts between free and

slave-state ideologies. Consequently, or for other

reasons, resident negroes and mulattoes

were to be restricted in their civil, military,

and political rights with impunity. How

effective or repressive the laws actually were

would have to be determined by a study

of cases prosecuted and is beyond the scope

30. Salmon P. Chase, ed., The

Statutes of Ohio and of the Northwestern Territory, ... from

1788 to 1833 ... (Cincinnati, 1833), 378; Appendix to the Annals

of Congress, 2 Cong., 1 Sess.,

1392.

31. Journal of the House of

Representatives, Ohio, Second Session, 1803-1804, II, 43, 47;

Journal of the Senate, Ohio, Second

Session, II, 68; Chase, Statutes of

Ohio, 393-94, 555-56.

Ohio Constitutional Convention

37

of this paper.32 Whether or

not it was possible for the pro-negro forces at the con-

vention to have achieved more than they

did is debatable since the total number of

votes on the negro issues favored the

pro-negro side. But since the sentiment of the

convention was so evenly divided between

the opposing factions, nothing more was

attempted and further questions on the

status of the negro were left for the General

Assembly to decide.

32. It was argued by Representative

Poindexter of Mississippi in the debate over the accep-

tance of the proposed constitution of

Illinois in 1818 that the registration feature for negroes

and mulattoes that had been in force in

the territory and was included in the constitution was a

protection to the extent that "she

[Illinois] had provided for the security of the freedom of

negroes, mulattoes, etc., and to prevent

them from being kidnapped, by causing them to be

registered." Annals of Congress,

15 Cong., 2 Sess., 310.