Ohio History Journal

KENNETH E. DAVISON

President Hayes and the

Reform of

American Indian Policy

The closing of the frontier by the white

man's unbridled expansion into the trans-

Mississippi West during the post-Civil

War years created the most critical period of

Indian-white relations in American

history. No longer could the Indians simply re-

treat or be removed to lands farther

west beyond the pale of white culture. A ma-

jority of "Uncle Sam's 300,000

stepchildren" lived directly in the path of two ad-

vancing white settler lines from East

and West which steadily compressed the

Indian tribes into ever smaller

corridors of freedom. Alarmed and menaced by the

constant diminishing of their lands and

buffalo, the red men gamely resisted white

penetration of their reservations and

hunting grounds. Meanwhile the government

in Washington found itself compelled to

resolve two urgent questions: what to do

about the Indian, and what agency should

handle the coming crisis-the Depart-

ment of the Interior or the War

Department?'

For sixty years prior to the creation of

the Interior Department in 1849, Indian af-

fairs had been under the complete

jurisdiction of the War Department. Thereafter,

a confusing system of divided

responsibility evolved, caused by the transfer of the

Indian Bureau, along with various other

burdensome agencies from the Treasury,

War, and Navy departments, to the newly

created Department of the Interior. Un-

der the system of dual control, a

skeleton frontier Army shared authority over In-

dian affairs with a host of civilian

agents. In general, the Army sought to protect

frontier settlements and overland

routes, suppress warlike tribes, discipline reserva-

tion Indians, and safeguard the Indians

from the white men. The Interior Depart-

ment's Indian service, meanwhile,

attempted to fulfill treaty commitments, to pro-

vide for the Indians' welfare, and to

educate and Christianize the tribes. Although

the policy of neither department

operated by unanimous consent, the Army tended

to favor pacification by force, while

the Interior program promoted conciliation of

the tribes.

Mixed with government inertia,

inefficiency, and indifference, this system had

1. Important studies of the Indian

question that have helped in the preparation of this paper include

Loring B. Priest, Uncle Sam's

Step-Children: The Reformation of United States Indian Policy, 1865-1887

(New Brunswick, 1942); Henry E. Fritz, The

Movement for Indian Assimilation, 1860-1890 (Philadelphia,

1963); Henry G. Waltmann, "The

Interior Department, War Department and Indian Policy, 1865-1887"

(unpublished Ph.D. dissertation,

University of Nebraska, 1962). See also Donald J. D'Elia, "The

Argu-

ment Over Civilian or Military Indian

Control, 1865-1880," The Historian, XXIV (February 1962),

207-225.

Mr. Davison is chairman American Studies

Department, Heidelberg College.

205

206 OHIO HISTORY

many drawbacks and proved impossible to

administer with full justice to the In-

dians. Attempts to define authority more

carefully failed, and much confusion and

recrimination over failures of policy

resulted. The Army regularly agitated for the

return of the Indian Bureau to the War

Department, arguing that this would be a

more efficient, honest, and economical

way of handling the Indian problem. With

equal vigor, the Interior Department,

arguing that the Army's policy really meant

extermination of the Indian tribes,

stoutly resisted any transfer of Indian affairs

back to the War Department.

In practice both departments were open

to criticism. Reports of fraud and mis-

management had long plagued the Indian

Bureau, and recurrent Indian uprisings

seemed to disprove the validity of its

policy of conciliating the tribes. The Army,

on the other hand, had dealt harshly

with Indian prisoners and was responsible for a

number of unwarranted frontier

massacres.

Other conditions complicated the problem

of divided jurisdiction. The Interior

Department suffered under the burden of

the sheer breadth of its administrative re-

sponsibilities and a continual shortage

of funds. The undermanned Army could

scarcely wage a major Indian war if

required. Fortunately, only a few of the 943

engagements against the Indians from

1865 to 1898 necessitated masses of three or

four thousand men. Faced with an enemy

using hit-and-run tactics, the Army's di-

lemma was to balance adequate strength

with adequate mobility. To do that, it

broke up into several columns, but this

method posed the danger of defeat, as Cus-

ter's annihilation in June 1876 so

horribly demonstrated.2 To the lack of organic

unity in the administration of Indian

affairs must be added the constant turnover of

leadership in the Interior and War

Departments. Between 1865 and 1887, no fewer

than ten Secretaries of the Interior, twelve

Commissioners of Indian Affairs, thirteen

Secretaries of War (three ad

interim), and three generals-in-chief of the Army super-

vised Indian policy, making any kind of

continuity and improvement in the quality

of Indian life difficult to attain.

When the Rutherford Hayes administration

took office in 1877, it inherited the

unsolved Indian question and all of its

ramifications. At first, conditions seemed

not to improve, but by 1879 a new era in

Indian policy began to emerge, and by the

time President Hayes and Secretary of

the Interior Carl Schurz left office in March

1881, a decided change in Indian-white

relations had occurred. Several factors con-

tributed to the new departure.

In the first place, the last of the

major Indian wars was fought.3 No longer would

there be any danger of a general Indian

uprising against the American Govern-

ment. The Sioux War of 1876-1877 was the

high water mark of Indian resistance

on the Great Plains, and Custer's

defeat, just a few days after Hayes was nominated

for President, proved to be the final

great Indian victory over the United States

Army in the West. Sitting Bull's

isolated band of Sioux escaped to Canada, but at

length, hungry and destitute, recrossed

the border and surrendered at Fort Buford,

North Dakota, in July 1881.

Meantime, one of the most remarkable

Indian leaders and a superb military strat-

egist, Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce

tribe, conducted a brilliant retreat of more than

2. Russell F. Weigley, History of the

United States Army (New York, 1967), 267-268.

3. An excellent brief resume of the

Indian wars may be found in U. S. National Park Service, Soldier

and Brave: Indian and Military

Affairs in the Trans-Mississippi West, Including a Guide to Historic Sites

and Landmarks (New York, 1963), Part I, 1-89. For details of Sitting

Bull's surrender, see Gary Penna-

nen, "Sitting Bull: Indian Without

a Country," The Canadian Historical Review, LI (June 1970),

123-140.

|

|

|

a thousand miles across Montana, Idaho, and Yellowstone Park between June and October 1877. He managed to elude a United States expedition under General 0. 0. Howard and to defeat elements of the Seventh Infantry under General John Gibbon at Big Hole, Montana, before he was compelled to surrender to Howard in the Bear Paw Mountains just thirty or forty miles away from Canadian sanctuary.4 Another problem began in the spring of 1878, when the Bannocks of Idaho left the Fort Hall Reservation and began plundering white settlements and ranches. General Howard eventually defeated them in July at Birch Creek, Oregon, and they returned to the reservation. The last Indian uprising, the Meeker Massacre by Utes at the White River Agency in northwestern Colorado, occurred during the Hayes presidency. Consid- ered one of "the most violent expressions of Indian resentment of the reservation system,"5 the nomadic Utes burned the agency buildings, killed agent N. C. Meeker and some of his employees, and took the white women captive. The revolt was sup- pressed in October, but only after cavalry troops sent south from Fort Fred Steele in Wyoming were ambushed and besieged at Mill Creek, Colorado, on September 29, 1879. On October 5, reinforcements arrived and lifted the siege. With the collapse of the revolt, several Ute leaders were sent to prison, and the tribe was relocated on a new reservation in Utah. With the ending of the Ute and Bannock troubles, last- ing peace prevailed on the northern and southern Plains and in the Northwest. Only the Apaches of the Southwest remained openly hostile, a problem solved by the surrender of Geronimo in 1886. A second major event of the Hayes presidency affecting the Government's Indian

4. Merrill D. Beal, "I Will Fight No More Forever": Chief Joseph and the Nez Perce War (Seattle, 1963), Mark H. Brown, The Flight of the Nez Perce (New York, 1967) are two recent accounts of this epi- sode. 5. Soldier and Brave, 63. 207 |

208

OHIO HISTORY

policy was the ultimate defeat of the

"transfer issue" in February 1879 after "one of

the most heated polemic arguments in the

history of Congress."6 Two major efforts

were conducted after the Civil War

(1867-1871 and 1876-1879) to transfer the In-

dian Bureau back to the War Department.

The advocates of transfer tended to be

military leaders or westerners, while

the defenders of the status quo were largely In-

dian service employees or easterners.

Another generalization to note is that the

Democrats, who controlled the House of

Representatives, voted for transfer, and the

Republicans, who held a majority in the

Senate, opposed transfer. During the sec-

ond great debate, Generals W. T. Sherman

and George Crook, both friends of Pres-

ident Hayes, testified in favor of

transfer, while Senator William Windom of Min-

nesota, Secretary Schurz, and Indian

Commissioner Ezra Hayt led the forces

opposing it. The proposal finally was

rejected by Congress for a variety of reasons:

abatement of the Indian wars; effective

lobbying by friends of the Indians; and a

rather general feeling that the military

was unsuited to govern the Indian tribes.

The significance of the defeat of the

transfer movement is that for the first time the

Indian Bureau did not have to be

constantly on the defensive but could now turn its

attention to much-needed reform

activities.

A third event making the Hayes Indian

policy unusual was the appointment of

Carl Schurz, a well-known reformer of

independent proclivities, as Secretary of the

Interior.7 Schurz held the

post for four full years, the first Interior head to do so

since before the Civil War. He not only

provided greater continuity and stability

for the department but also worked

harder at the job than any of his six predeces-

sors appointed by Johnson or Grant.

Furthermore, Schurz, of all the Hayes Cabi-

net officers, most nearly conducted his

department in the spirit of the civil service re-

form crusade. He purified the Indian

service and led the critical fight to preserve

civilian control over Indian affairs.

Schurz, as Secretary of the Interior,

headed a department involving probably

more work and care than any other under

the government in 1877. In his charge

were the Indian service with its many

officers, over a quarter of a million Indians,

and millions of acres of reservations;

the public lands; hundreds of thousands of

government pensioners; the Patent

Bureau; all business dealings of the government

with the land-grant railroads; the

Bureau of the Census; the Geological and Geo-

graphical Surveys; the charitable

institutions of the capital; and many of the public

grounds and parks.

As a student of politics suddenly thrust

into high executive office, Schurz was not

expected to be a very practical

administrator let alone one up to the standards of his

immediate predecessor, Zachariah

Chandler, the Secretary of the Interior, consid-

ered the best official among the

practical politicians who had held the post up to

that time.8 But Schurz

confounded his critics. Whereas Chandler adhered to a

regular office schedule of ten in the

morning until four in the afternoon, Schurz,

even though he had a quicker and

better-trained mind, established a nine to six rou-

6. Waltmann, "The Interior

Department," 304.

7. A very good contemporary analysis of

Schurz as Secretary of Interior is Henry L. Nelson, "Schurz's

Administration of the Interior Department,"

International Review, X (April 1881), 380-396. Other de-

tails are provided by Claude Moore

Fuess, Carl Schurz, Reformer, 1829-1906 (Port Washington, New

York, 1963), chaps. 19 and 20.

8. Nelson, "Schurz's

Administration," 381. A recent appraisal of Secretary Chandler may be

found in

Sister Mary Karl George, R.S.M., Zachariah

Chandler: A Political Biography (East Lansing, 1969),

241-248.

|

|

|

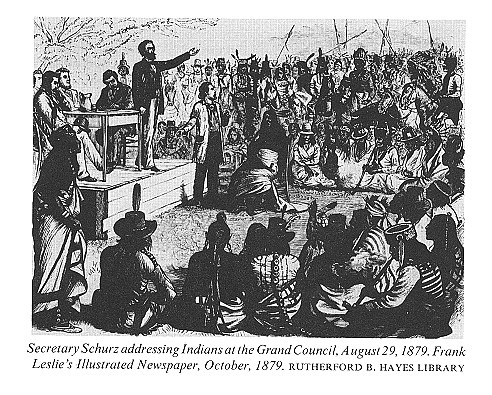

tine in order to acquaint himself better with the personnel and problems of his de- partment. Probably no executive officer since the close of John Quincy Adams' ad- ministration found so much time to devote to the real business of government as did Carl Schurz. Since the Indian Bureau, of all the agencies under his control, seemed most in need of attention, he began by appointing a three-man commission to investigate it. The commission, which gathered evidence from June 1877 to January 1878, unearthed many kinds of irregularities: poor supervision, inadequate accounting by Indian agents, improper inspection of agencies, concealment of vital documents from superiors, and, in particular, widespread cheating of Indians by unscrupulous agents and traders. Once he had the facts, Schurz moved swiftly to correct abuses. Some employees including, S. A. Galpin, the chief clerk of the Indian Bureau, and John Q. Smith, commissioner of Indian affairs, were dismissed.9 A code of regu- lations for the guidance of Indian agents appeared for the first time, and the system for keeping accounts was revised. Agents were now required to file regular reports and might be inspected at any time without forewarning. By licensing and bonding all Indian traders, Schurz also blocked the swindling of Indians. Further, to in- crease his knowledge of Indian affairs, the Secretary made an extended western trip during August and September 1879, in company with Webb Hayes, the President's son. Schurz thus became the first Secretary of the Interior to deal with the Indian problem in a systematic way. He visited Indians on the reservations, met them in Washington, listened sympathetically to their wrongs, and studied their character.

9. When Smith's successor, Ezra A. Hayt, Commissioner of Indian Affairs, 1877-1880, got in trouble over a shady transaction to acquire a silver mine near the San Carlos Agency, Schurz after due inquiry cashiered him also. 209 |

|

Instead of adopting toward the Indians the view of either the naive eastern philan- thropists or the vengeful frontiersmen, Schurz took a middle stance, treating the In- dians as he found them, a capable race in need of Government aid and assistance. He concluded that the rapid and irresistible spread of settlements in the interior of the continent, the building of Pacific railways, and the consequent disappearance of the buffalo and wild horse, with all the larger game, spelled the end of Indian sub- sistence by hunting. Indians, he felt, must be taught agriculture, herding, and freight hauling.10 He sought to give dignity to each Indian as an individual. The new book of regu- lations for the bureau specified that annuities and supplies should go directly to heads of families rather than to the tribal chieftains. An Indian police force be- came a reality, and tribal ownership of land began to give way to the principle of severalty, or individual ownership. The general application of business methods to government and the improvement in moral tone and efficiency of the Indian service won for Schurz the respect of Indian tribes and white reformers alike.11 A fourth development in the Hayes era contributing to a change in Indian rela- tions was a new system of Indian education associated with an Army officer, Cap- tain Richard Henry Pratt.12 Before Hayes' time, the native tribesmen were com-

10. See "A Century of Dishonor," The Nation, XXII (March 3, 1881), 152. 11. When Schurz paid an official visit to Hampton Institute at its commencement in 1880, he was greeted by the Indian pupils as their "wise and kind friend." Cited in Fuess, Carl Schurz, 264n. A good summary of Schurz' outlook on Indian affairs is contained in his article "Present Aspects of the Indian Problem," North American Review, CXXXIII (July 1881), 1-24. 12. The contributions of Pratt are detailed in Priest, Uncle Sam's Stepchildren, chap. 11; Elaine Good- ale Eastman, Pratt: The Red Man's Moses (Norman, 1935); Everett Arthur Gilcreast, "Richard Henry Pratt and American Indian Policy, 1877-1906: A Study of the Assimilation Movement" (unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Yale University, 1967); Daniel T. Chapman, "The Great White Father's Little Red Indian School," American Heritage, XXII (December 1970), 48-53, 102. 210 |

Hayes' Indian Policy 211

monly regarded as incapable of being

civilized. In April 1878, Pratt and General

Samuel Chapman Armstrong, head of

Hampton Institute, a Virginia school for

blacks, began an experiment at Hampton

in Indian education by overseeing the

training of seventeen Indian

ex-prisoners of war. Armstrong then got Schurz' con-

sent to train an additional fifty Indian

pupils. Meanwhile, Pratt, who preferred to

educate Indians separately from Negroes,

requested permission to open an Indian

school in the deserted Army barracks at

Carlisle, Pennsylvania, a proposal endorsed

by both Schurz and Secretary of War

George W. McCrary.13 Pratt opened the Car-

lisle Indian School in October 1879 with

eighty-two Sioux students. Enrollment

climbed steadily, until Congress, faced

with a successful experiment, formally au-

thorized the school and voted it

financial support in May 1882.

The progress of Indians at Hampton and

Carlisle had three immediate effects: it

led to the establishment of a third

boarding school for Indians of the Pacific region

at Forest Grove, Oregon; by

demonstrating that Indian children were "as bright

and teachable as average white children

of the same ages," it helped to arouse a

strong interest in Indian assimilation

among benevolent people; and it produced the

most vituperative attack upon advocates

of Indian education that western sponsors

of the inferior-race concept could

deliver.14

The hostile view of the West toward

Indians had prevailed throughout the 1870's

because public opinion could not be

aroused in favor of an undefeated people.

However, the passing of the major Indian

wars, the decline of the transfer issue, and

the reforms instituted by Schurz and

Pratt brought about a new attitude by the end

of the decade. The time for healing the

wounds inflicted on the Indian by the na-

tion had arrived, and the new crusade

for Indian reform was sparked by two in-

fluential books published in 1879 and

1881. The first, Our Indian Wards written by

George W. Manypenny Commissioner of

Indian affairs under President Pierce,

called attention to the foolish

jurisdictional discord between the Department of the

Interior and the Army and arraigned the

latter for sharing the worst prejudices of

the frontier against the Indians.15

Far more powerful in its impact on

public opinion and the Congress was Helen

Hunt Jackson's A Century of Dishonor which

indicted the civil arm of the govern-

ment and, in particular, Secretary

Schurz for the wrongs and neglect of Indians.

The irony in this situation was strange

indeed. Schurz, the very epitome of sympa-

thetic reform, a man who devoted himself

to improving the lot of the helpless tribes,

became the target of a vicious and

unrelenting attack by an obscure lady magazine

writer who made literary warfare on

behalf of the Indians into a personal crusade.

Her book consisted of a series of

powerful vignettes documenting the relations of

twelve important tribes with the federal

and state governments. It showed clearly

how the Indian had been obviously

victimized by white civilization. Each member

of Congress received a copy as part of

the author's campaign to get the nation to

correct its record of Indian

mistreatment. In a period of four years prior to her

13. Both Secretary of War McCrary

(1877-1879) and his successor, Alexander Ramsey (1879-1881),

had prior experience with Indian

affairs. As a Congressman from Iowa, McCrary had served with the

House Committee on Indian Affairs and

Ramsey, as a former governor of both the Territory and State of

Minnesota, had firsthand knowledge of

red men on the warpath.

14. Fritz, Movement for Indian

Assimilation, 166.

15. A Democrat in politics and for many

years editor of an Ohio paper, Manypenny had retired from

active participation in public affairs

until he was invited by President Hayes to take the chairmanship of

the committee appointed under Act of

Congress to treat with the Sioux.

212 OHIO HISTORY

death in 1885, Mrs. Jackson aroused the

country to the Indian's plight through ex-

tensive travel, magazine articles, and a

highly sentimental second book called

Ramona (1884),

a tour deforce novel depicting the decline of California's Spanish

culture and its dependent Indian

society.l6

Another event that shook the Hayes

administration almost from start to finish

concerned removal of a minor tribe, the

Ponca Indians, from their reserve in south-

eastern Dakota to Indian Territory

(Oklahoma) during the spring and summer of

1877.17

Through her protest of the Government's

treatment of the Poncas Helen

Hunt Jackson first gained prominence as

a defender of Indian rights. Public furor

over the plight of the Poncas gradually

mounted and finally reached such a pitch

that President Hayes appointed a special

commission to deal with the problem.

Hayes and Schurz actually inherited the

Ponca question from the Grant adminis-

tration. A peaceful tribe of about eight

hundred farming people, the Poncas were

caught in a congressional blunder that

gave away their lands to the warlike Sioux.

Just a day before Schurz assumed office,

Congress attempted to rectify its error by

transferring the Poncas far to the

south. Even though the tribe protested moving to

Indian Territory, the Army forcibly

removed them in a pitiful two-month trek com-

plicated by storms, flooding, and

epidemic malaria; many died. Upon arrival, the

new reservation proved to have poor soil

and bad water. With their farm imple-

ments and most of their cattle gone, the

Poncas wanted to return to their Dakota

homes, which by then were in Sioux

hands. Schurz could not allow this, but he did

give them new and more fertile lands in

the Indian Territory, necessitating still an-

other costly removal attended by more

sickness and death. In the spring of 1879,

unable to bear the heat and dust of the

Oklahoma plains, some of the Poncas, led by

Chief Standing Bear, attempted to flee

to Dakota; but when they stopped for sup-

plies at the Omaha Reservation, soldiers

blocked their path and endeavored to

make them go back south. Standing Bear

resisted and was promptly cast into

prison.

A violent controversy led by Omaha

citizens ensued. Mrs. Jackson entered the

fray and raised a fund to defend

Standing Bear in the courts. On January 9, 1880,

she wrote to Schurz demanding that he

aid the Poncas by bringing suit to recover

their original reservation. Schurz

declined, saying the Supreme Court would not

permit an Indian tribe to sue in a

federal court anyway, and pointed out that the

Poncas had already built new homes and

planted their crops. He recommended

that the funds raised by Mrs. Jackson be

used instead to help the Indians get indi-

vidual titles to their new farms.

Mrs. Jackson refused to be placated,

however, and others rallied to her side.

Meantime, Standing-Bear and an Indian

girl, Bright Eyes, went on a lecture tour,

under the tutelage of a missionary named

Thomas H. Tibbles, to plead their case.

Large crowds come out to hear the pair

in Chicago, Philadelphia, New York, and

Boston where the orator Wendell Phillips

added his eloquence to the cause.

President Hayes quite frankly admitted a

grievous wrong had been inflicted upon

the Poncas but decided to make

restitution by better treatment rather than by re-

16. Allan Nevins, "Helen Hunt

Jackson, Sentimentalist vs. Realist," American Scholar, X (Summer

1941), 269-285.

17. Earl W. Hayter, "The Ponca

Removal," North Dakota Historical Quarterly, VI (July 1932),

262-275, is sympathetic to the Indians.

Stanley Clark, "Ponca Publicity," Mississippi Valley Historical

Review, XXIX (March 1943), 495-516, tends to belittle the evicted

Poncas.

Hayes' Indian Policy 213

moval of the Poncas for still a third

time.18 He appointed a presidential commission

in December 1880, composed of Brigadier

Generals George Crook and Nelson A.

Miles, William Stickney (a member of the

Board of Indian Commissioners) and

Walter Allen who represented a Boston

citizens' committee, to visit the Ponca tribe,

ascertain facts, and make

recommendations.19

As an aftermath, in a message to

Congress on February 1, 1881, Hayes reported

that the 521 Poncas living in the Indian

Territory were satisfied with their new

homes, were healthy, comfortable, and

contented, and did not wish to return to

Dakota. Another group of about 150

Poncas, still in Dakota and Nebraska, pre-

ferred to remain on their old

reservation. Given this situation, the President urged

that the wishes of both branches of the

tribe be recognized. He then outlined a

four-point Indian policy for the future

that would include a program of industrial

and general education for Indian boys

and girls to prepare them for citizenship.

Also, land allotments would be held in

severalty, inalienable for a certain period.

Insurance that there would be fair

compensation for Indian lands and that the In-

dian would receive citizenship were

other important aspects of the policy. These

proposals clearly foreshadowed events of

the 1880's, especially the Dawes Severalty

Act of 1887 which provided for the

dissolution of the Indian tribes as legal entities

and the division of tribal lands among

individual members. The Sioux were also to

be compensated for relinquishing land to

those Poncas who were not removed to In-

dian Territory.

Hayes avoided assessing blame among the

Executive branch, Congress, or the

public for the injustices done to the

Poncas. He simply asserted, "As the Chief Ex-

ecutive at the time when the wrong was

consummated, I am deeply sensible that

enough of the responsibility for that

wrong justly attaches to me to make it my par-

ticular duty and earnest desire to do

all I can to give to these injured people that

measure of redress which is required

alike by justice and humanity."20 In response

to his message, Congress quickly

appropriated $165,000 to indemnify the Poncas.

This action seemed wholly to satisfy

them.21 Later the President issued several

other decrees affecting Indian rights

which met with much less success than his

Ponca message. He was unable to prevent

a series of unlawful white invasions of

Indian Territory despite presidential

proclamations containing stern warnings and

the threat of imprisonment.22

What had been accomplished in the

improvement of Indian rights and status by

the Hayes administration, however, far

outweighed any failures of omission or com-

mission. As the 1880's opened, a new

approach to the Indian question was evident

in Government policy and public opinion.

The idea of Indians being "aliens" or

"wards" was passing. The

reservation system was yielding to the movement for

severalty legislation. The success of

Carlisle and other early schools discounted the

belief that the Indian was incapable of

civilization. It was also obvious that civil-

ians, and not the military, would shape

the future of the American Indian. Hayes

consistently advocated a new policy

which would encourage Indians to own land as

18. Hayes Diary, December 8, 1880; Hayes

to George F. Hoar, December 16, 1880. Hayes Papers,

Rutherford B. Hayes Library, Fremont,

Ohio.

19. Annual Report of the Secretary of

the Interiorfor the Year Ended June 30, 1881, II, 275.

20. James D. Richardson, A

Compilation of the Messages and Papers of the Presidents (New York,

1897), X, 4582-86.

21. Fuess, Carl Schurz, 263.

22. Richardson, Messages and Papers, IX,

4499-4500, X, 4550-51.

214 OHIO

HISTORY

individuals, educate Indian children at

government expense in the pursuits of agri-

culture, herding, and freighting, and

give the red men citizenship. He also success-

fully instituted on the reservations an

Indian police force manned by Indians.

By study of the Indian question, by

visits to Indian reservations and schools, by

discussion with Indian leaders in the

White House, and by presidential pro-

nouncements, Hayes demonstrated his deep

concern for the American Indian. His

personal library also contained many

books on Indian history and culture. In his

first Annual Message of December 3,

1877, Hayes proclaimed:

The Indians are certainly entitled to

our sympathy and to a conscientious respect on our part

for their claims upon our sense of

justice .... Many, if not most, of our Indian wars have

had their origin in broken promises and

acts of injustice upon our part.... We can not ex-

pect them to improve and to follow our

guidance unless we keep faith with them in respect-

ing the rights they possess, and unless,

instead of depriving them of their opportunities, we

lend them a helping hand .... The

faithful performance of our promises is the first condi-

tion of good understanding with the

Indians. I can not too urgently recommend to Congress

that prompt and liberal provision be

made for the conscientious fulfillment of all engage-

ments entered into by the Government

with the Indian tribes.23

In July 1878, while preparing some notes

for a speech commemorating the cen-

tennial of the Wyoming Valley massacre,

Hayes confided to his Diary that the mat-

ter of how the white man should deal

with the Indians was a problem which for

three centuries had remained almost

unsolved. Taking a cue from William Penn's

philosophy on the subject, he concluded:

"If by reason of the intrigues of the whites

or from any cause Indian wars come, then

let us correct the errors of the past. Al-

ways the numbers and prowess of the Indians

have been underrated."24

Near the end of his term, the President

enumerated the points in which he felt his

administration had been successful to a

marked degree. One of his proudest boasts

was "an Indian policy [of] justice

and fidelity to engagements, and placing the In-

dians on the footing of citizens. "25 It was a rightful claim to fame.

23. Fred L. Israel, ed., The State of

the Union Messages of the Presidents, 1790-1966 (New York, 1966),

II, 1350-51.

24. Hayes Diary, July 1, 1878.

25. Ibid., April 11, 1880.