Ohio History Journal

MARIAN J. MORTON

Temperance, Benevolence, and the

City: The Cleveland Non-Partisan

Woman's Christian Temperance

Union, 1874-1900

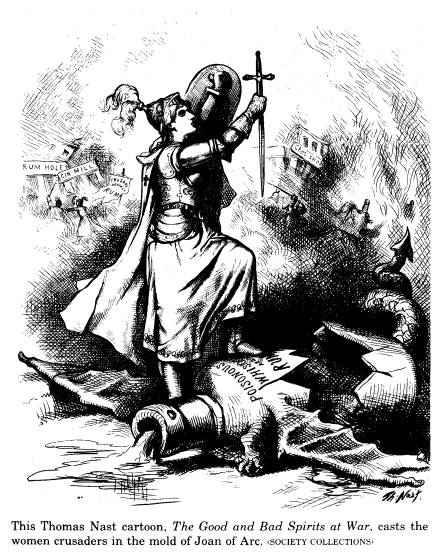

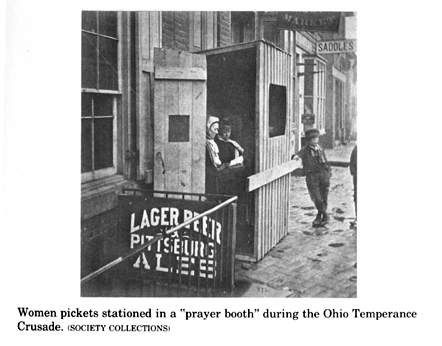

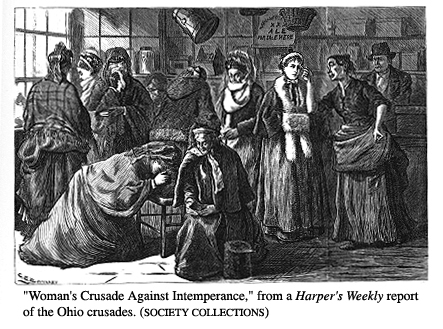

Here they come now, fifty redoubtable

and respectable women,

prayer books in one hand and umbrellas

in the others, for it looks

like rain on this March morning of 1874

in Cleveland, Ohio. They

are striding vigorously down Euclid

Avenue, headed for the several

saloons on Public Square, which they

intend to close down with

their hymns and fervent prayers. They

are the Woman's Temper-

ance League of Cleveland.1 By 1885 this

pious praying band will

have become the Non-Partisan Woman's

Christian Temperance Un-

ion. They will designate themselves

"Non-Partisan" to disassociate

themselves from the national Woman's

Christian Temperance Un-

ion's endorsement of the Prohibition

Party,2 but they will become

increasingly active in Cleveland

politics. These women will main-

tain three temperance "friendly

inns" with inexpensive lodgings

and reading rooms for men,

"mothers' meetings" for women, sewing

classes for little girls, hygiene talks

for boys, and gospel meetings

for all; they will conduct missionary

services and an employment

bureau at a refuge for homeless women

and unwed mothers; they

will visit jails and the city infirmary

and furnish food, clothing, and

sometimes funds for the needy. The

Cleveland Non-Partisan Union

Marian J. Morton is Professor of History

at John Carroll University.

1. This description is compiled from

first-hand accounts in Works Progress Admin-

istration of Ohio, Annals of

Cleveland, 1818-1935, Vol. LVII (1874) (Cleveland, 1937),

750-56, and from Mary Ingham, Women

of Cleveland and Their Work: Philanthropic,

Educational, Literary, Medical, and Artistic (Cleveland, 1893), 168-69.

2. Ruth Bordin, Woman and Temperance:

The Quest for Power and Liberty, 1873-

1900 (Philadelphia, 1981), 129, describes these Non-Partisan

WCTU's as insignifi-

cant in number and influence and

Republican in their political sympathies. The

Cleveland group was probably Republican

in sympathies but was by no means insig-

nificant on the local level.

|

Temperance, Benevolence, and the City 59 |

|

|

|

will become, in short, an example of the combination of benevolence and evangelism with which organized religion tried to meet the physical and spiritual needs of urban Americans in the nineteenth century. Later historians, products themselves of a more secular age, have written the story of the Woman's Christian Temperance Union as political history. They have, for example, discussed it as part of the |

60 OHIO

HISTORY

Prohibition movement, and using the

conservative-liberal criteria

with which political reformism is

judged, have declared the WCTU

conservative because it advocated

little substantial change in the

economic or politcal status quo,

suggested moral and individual

solutions to public problems, and

attempted to impose its own mid-

dle class and ethnic-derived values on

the immigrant working

class.3

More recently, historians of women have

evaluated the WCTU by

a different standard, as either

conservative or "feminist." Here too

most have described the group as

conservative because it simply

applied traditional domestic values and

techniques to the public

sphere; Mary Ryan, for example, calls

this kind of activity "social

housekeeping."4 Two

revisionists, however, have argued that the

WCTU was a "feminist" group

because it significantly expanded

women's autonomy and equality by allowing

them to escape the

domestic confines of kitchen and

nursery and by raising their ex-

pectations about public roles, as in

the support of suffrage.5

3. Andrew Sinclair, Prohibition: The

Age of Excess (Boston, 1960) and Joseph R.

Gusfeld, Symbolic Crusade: Status

Politics and the Temperance Movement (Urbana,

Ill., 1963) are examples of this

approach. Both historians are much influenced by

Richard Hofstadter's thesis that

Progressive reformers, such as temperance advo-

cates, were motivated by status loss,

and that, therefore, instead of proposing solu-

tions to the "real" economic

problems of the day, operated in a kind of fantasy world

in which they played out their personal

and psychological needs. Joseph Timberlake,

Prohibition and the Progressive

Movement, 1900-1920 (Cambridge, Mass.,

1963) and

Norman Clark, Deliver Us From Evil:

An Interpretation of American Prohibition

(New York, 1976) describe intemperance

as a geniune social problem; they are more

sympathetic to the temperance movement

but describe it as an attempt to rescue or

restore middle class values. Jed

Dannenbaum, "Drink and Disorder: Temperance

Reform in Cincinnati, 1841-1874"

(Ph.D. dissertation, UCLA, 1978) summarizes

these views: "The prevalent view of

nineteenth century temperance reform has been

that it was conservative, elitist,

nativist, anti-democratic, and predominately rural,"

(6). Dannenbaum disagrees, but his

evaluation remains within the political

framework of the earlier historians.

4. Sheila Rothman, Woman's Proper

Place: A History of Changing Ideals and

Practice, 1870 to the Present (New York, 1978), 67ff; Mary Ryan, Womanhood in

America From Colonial Times to the

Present, 2nd ed. (New York, 1979),

135-50.

5. Barbara Leslie Epstein, The

Politics of Domesticity: Women, Evangelism and

Temperance in Nineteenth Century

America (Middletown, Conn., 1981)

describes the

WCTU as "proto-feminist" and

"feminist" because it stressed women's interests and

advocated woman suffrage as a means of

achieving them (1, 6, passim) although the

WCTU did not seriously challenge a

male-dominated society (132-33). Bordin,

Woman and Temperance, also describes the WCTU as "feminist" because

members

experienced "power and

liberty" as women in pursuit of their temperance goals.

Bordin notes that the use of the term

"feminist" is ahistorical since it had not yet

been coined but applies it anyway to

indicate that the WCTU advocated "legal and

social changes [to] establish political,

economic, and social equality of the sexes"

(179). Both Epstein and Bordin base

their cases for "feminism" primarily on Frances

Temperance, Benevolence, and the

City 61

To judge this group in political

terms-conservative, liberal, or

feminist-however, is beside the point

because it measures

nineteenth century women by twentieth

century standards; natur-

ally, the women of the WCTU appear

retrogressive and narrow. The

members of the Non-Partisan WCTU of

Cleveland were neither so-

cial critics nor innovators. They found

little in their society to com-

plain about, except the widespread use

of alcohol. Their middle class

and ethnic bias is occasionally

revealed, as in an early reference to

"the ignorant and vicious classes

in our great cities."6 And although

they did advocate public and political

solutions to intemperance,

they relied also on individual conversions

and private philanthropy.

Non-Partisan Union women did get out of

the house, but seeing how

the "other half'-particularly the

female half-lived in the Cleve-

land slums probably reaffirmed their

belief in the correctness of

their own conventional female roles and

lifestyles. They did not

even support woman suffrage, except for

school and temperance

elections. The Non-Partisan Union's

report in 1901 on the first

twenty five years of their Central

Friendly Inn indicates this gener-

al acceptance of nineteenth century

values and attitudes: The Inn

has given the gospel of God's love to

the throngs who in fair weather gather

on Sunday evenings at our doors; ... It

has given material relief in cases of

extreme need; it has given patient

prayerful helpfulness to the slaves of

appetite trying to break the chains; to

women ... it has presented higher

ideals of womanhood and motherhood ...

To boys and girls exposed to

fearful temptations it has given lessons

of purity, of self-control, of unself-

ishness and truthfulness.7

Willard's ideas and activities at the

national level, as these are described by Willard

herself in Glimpses of Fifty Years,

1839-1889: The Autobiography of an American

Woman (Chicago, Philadelphia, Kansas City, Oakland, 1889) and

by Mary Earhart

Dillon, Frances Willard: From Prayer

to Politics (Chicago, 1944), for whom Willard

was "the general of the whole

woman's movement, seeking the emancipation of her

sisters from all legal, traditional, and

economic bonds" (11). Bordin does note that

there was sometimes an ideological gap

between Willard and the WCTU rank and

file (106, 108).

6. The group was organized as the

Woman's Temperance League in 1874, became

the Woman's Christian Temperance League

in 1880, and then in 1885 the Non-

Partisan Woman's Christian Temperance

Union of Cleveland. I have used the last

name in the body of the paper since it

was retained until 1928 even though sometimes

I am referring to the group before 1885.

However, since the group's published annual

reports and unpublished records (MS

3247) are catalogued by the Western Reserve

Historical Society, under "Woman's

Christian Temperance Union, Cleveland," my

footnotes will use that designation, as

in this citation: Woman's Christian Temper-

ance Union, Cleveland, Ohio, Annual

Report 1878, 9, at the Western Reserve Histor-

ical Society, Cleveland, Ohio.

Hereinafter the references will be to the WCTU, Cleve-

land.

7. WCTU, Cleveland, Annual Report, 1901,

37.

62 OHIO HISTORY

It is more accurate-and fairer-to try to

see these women as they

saw themselves and as their

contemporaries saw them: pious

churchwomen going about their Father's

business, as they broadly

defined it, who created institutions

which looked not to the past but

to present problems.8 The

purpose here will be to discuss the Cleve-

land Non-Partisan WCTU as a religious

phenomenon, which

flourished at a time-the last quarter of

the nineteeth century-in

which much of established Protestantism

concerned itself in active

and vital ways with both the religious

and the secular, the spiritual

and the material aspects of human life.

This dual thrust had its

roots in the antebellum period, in

which, according to Timothy

Smith, evangelicalism encompassed the

desire to save both souls

and the society, particularly in the

cities.9 Churches, especially

through their missions, responded to

urban unemployment, poverty,

slums, and immigrants, first with

attempts to convert the unfortun-

ates and then with attempts to aid them

with social service institu-

tions such as reading rooms, industrial

training schools, employ-

ment bureaus, outdoor relief, children's

homes and refuges; these

would lay the groundwork for later

groups such as the WCTU. Car-

roll Smith-Rosenberg has concluded that,

in the absence of an active

welfare state, by the mid-nineteenth

century the churches "had be-

come the principal instrument for

dealing with the problems of the

city."10

Early Cleveland churches illustrated

this social concern. Cleve-

land is located in the Western Reserve,

which was not heavily set-

tled until the first quarter of the

nineteenth century. Into it came

men and women of stern Protestant

conscience, freshly scorched by

the fires of the Second Great Awakening.

Among the earliest in-

stitutions which these settlers

established were church-related

organizations with a benevolent purpose.

Examples abound, such as

the Martha Washington and Dorcas

Society, the Female Charitable

Society of Trinity Church, and the

Female Moral Reform Society,

whose activities on behalf of

Cleveland's poor went beyond their

spiritual salvation.11

8. Agnes Dubbs Hayes, Heritage of

Dedication: One Hundred Years of the National

Woman's Christian Temperance Union,

1874-1974 (Evanston, Ill., 1973)

describes

institutions for women still maintained

by the national WCTU, 101-06. In Cleveland,

Friendly Inn Settlement and Rainey

Institute, now a part of the Cleveland Music

School Settlement, survive as examples

of the Cleveland women's work.

9. Timothy L. Smith, Revivalism and

Social Reform: American Protestantism on

the Eve of the Civil War (New York, 1965), especially 8, 168-73.

10. Carroll Smith-Rosenberg, Religion

and the Rise of the American City; The New

York City Mission Movement, 1812-1870

(Ithaca and London, 1971), 2.

11. Ingham, Women of Cleveland,

passim.

Temperance, Benevolence, and the

City 63

In the post-Civil War period Protestant

churches expanded and

diversified these services and

interests. As thousands of zealous

missionaries spread the gospel around

the globe, confidently anti-

cipating "the evangelization of the

world in this generation,"12 the

home mission movement intensified its

work among the hundreds of

thousands of Catholic, Jewish, and

unchurched European immi-

grants and native-born Americans in

American cities. These people

became the targets of a wide variety of

Protestant evangelical and

benevolent activity, such as the YMCA,

the Woman's Christian

Association, the Salvation Army, the

city missions, the "institution-

al" churches-and the Woman's

Christian Temperance Union.13

Cleveland also illustrates this

expansion and diversification. By

1870 the once-sleepy village was on its

way to becoming a smoky,

industrial metropolis, with all the

economic and social dislocation

which accompanied rapid urban growth.14

Its population of almost

93,000 had doubled since 1860; more and

more of this population

was of foreign birth, the Germans and

Irish predominating.15 Im-

migrants from both Europe and the

American countryside were

attracted to Cleveland by its

flourishing industries, particularly oil,

iron, and steel. Great corporations grew

up (most notably Standard

Oil of Ohio), and great fortunes were

made (most notably by John D.

Rockefeller, later a substantial

benefactor of the Cleveland Non-

Partisan Union). At the same time,

however, there developed a

sizable poor, transient population,

unused to city ways and often

unable to care for themselves. Cleveland

philanthropy adapted

accordingly. For example, the Bethel

Union, originally simply a

Protestant mission and lodge for

destitute sailors, in1869 expanded

its services to provide shelter for

girls and women, an employment

office, and outdoor relief, as well as

gospel services; in 1884 the

Bethel Union was merged with the

Cleveland Charity Organization

Society to become Associated

Charities.16

12. Sydney W. Ahlstrom, A Religious

History of the American People, vol. 2 (New

York, 1975), 342-47, on Protestant world

missions; on women as missionaries, see R.

Pierce Beaver, American Protestant

Women in World Missions: A History of the First

Feminist Movement in North America, rev. ed. (Grand Rapids, 1980).

13. See Ahlstrom, A Religious

History, 191-201; Charles H. Hopkins, A History of

the YMCA in North America (New York, 1951); Robert D. Cross, ed., The Church

and

the City, 1865-1910 (Indianapolis, 1967), xiv, xxxix.

14. Edmund H. Chapman, Cleveland:

Village to Metropolis: A Case Study of Prob-

lems of Urban Development in

Nineteenth Century America (Cleveland,

1964), 97-150.

15. William Ganson Rose, Cleveland:

The Making of a City (Cleveland and New

York, 1950), 361.

16. Ibid., 122, 1347; Lucia

Johnson Bing, Social Work in Greater Cleveland: How

Public and Private Agencies Are

Serving Human Needs (Cleveland, 1938),

33.

64 OHIO HISTORY

The mother of the Non-Partisan WCTU of

Cleveland, the

Woman's Christian Association,

established in 1869, was itself a

response to the new needs of women in an

urban, industrial setting.

At its first annual meeting, the WCA

declared its object to be "the

spiritual, moral, mental, social, and

physical welfare of women in

our midst."17 To achieve

this, the WCA, which became the YWCA in

1893, moved beyond proselytizing and

eventually established four

residences for women, which provided

institutional models for the

Non-Partisan Union. Equally important in

shaping the Non-

Partisan Union was the WCA motto:

"Everything we do is

religious."18

In March 1874, "believing that God

called his hand-maidens into

a new and difficult field," and

inspired by reports of the "praying

bands" of women elsewhere in the

Midwest, Sarah Fitch, WCA pres-

ident, called a meeting of 600 Cleveland

women, who thereupon

organized their own bands and descended

upon the local saloons, as

we have seen.19 Despite some

hostility among the local citizenry and

indifference on the part of public

officials, the women claimed great

progress by May: 4315 citizens had taken

the pledge; 76 dealers, 200

property owners, and 450 saloons had

been visited.20 Their optimism

was premature, however, for it would be

many decades before all the

saloons would be closed and all

Americans would take the pledge.

In the meantime, however, the national

Woman's Christian

Temperance Union would be organized in

Cleveland in 1874, and

the Cleveland group would affiliate

briefly with it. More important-

ly, for the purposes of this paper, for

more than half a century this

Non-Partisan Union would energetically

engage itself with the spir-

itual and material welfare of

Clevelanders less fortunate than

themselves.

17. Mildred Esgar, "Women Involved

in the Real World: A History of the Young

Women's Christian Association of

Cleveland, Ohio, 1868-1968," (unpublished type-

script at the Western Reserve Historical

Society, Cleveland, Ohio), 41. The WCA's

patterned themselves after the YMCA, as

described in Hopkins, A History of the

YMCA.

18. Esgar, "Women Involved in the

Real World," 56. Smith-Rosenberg, Religion

and the Rise of the American City also stresses the pietist intentions of these urban

reformers; see especially 272-73.

19. Esgar, "Women Involved in the

Real World," 55; WCTU, Cleveland, "Records,"

June 27, 1874.

20. ("Mother") Eliza Stewart, Memories

of the Crusade: A Thrilling Account of the

Great Uprising of the Women of Ohio

in 1873, Against the Liquor Crime (Columbus,

1888) describes her trip to Cleveland as

a "sore trial" (8); the lack of police protection

for the "crusaders" led her to

conclude that "Cleveland is built on beer" (368). The

figures are from Works Progress

Administration of Ohio, Annals of Cleveland, Vol.

XVII, 767.

|

Temperance, Benevolence, and the City 65 |

|

|

|

The "theology" of the Non-Partisan Union provided the intellec- tual underpinnings for these activities and connected the group with developments in late nineteenth century Protestant thought. The immediate goal was temperance, defined as total abstinence from alcohol. The ultimate goal was conversion to Christ. The means to both ends was the gospel; hence this was called "gospel temperance." Since the women believed that the use of alcohol was an impediment to finding Christ and salvation-"one of the great hindrances to the promise of true religion"-21 conversion to the temperance was logically construed as the first step to conversion to Protestant Christianity. (The tendency for temperance opponents to be Roman Catholic reinforced this thinking.) This emphasis on indi- vidual conversion links the WCTU with evangelism in general and with the theological "conservatism" of Dwight Moody and other re- vivalists of the period.22

21. WCTU, Cleveland, Annual Report, 1878, 9. 22. On this aspect of nineteenth century Protestantism, see the following: Martin E. Marty, Righteous Empire: The Protestant Experience in America (New York, 1970), especially 184-85; William G. McLoughlin, Modern Revivalism: Charles |

66 OHIO HISTORY

But intemperance was viewed also as a

social ill with practical

implications for life in this world,

especially for women and chil-

dren. Intemperance, therefore, could be

cured and prevented by

secular means such as social service

institutions and legislation.

This strain in WCTU thought links it

with the more "liberal" Social

Gospel. According to Sydney E. Ahlstrom,

the WCTU was "the most

significant route by which social

Christianity penetrated the con-

servative evangelical

consciousness."23

The Cleveland Non-Partisan Union

directed its attentions first at

men, saloon-keepers and then

saloon-goers. In 1874 the group estab-

lished Central Friendly Inn in the

"Haymarket" district, a neigh-

borhood of Italians, Slavs, Syrians and

other immigrants, adjoining

"Whiskey Hill," so-called

because it had the most saloons as well as

the highest birth and death rates in the

city.24 The Inn, patterned

after YMCA facilities and other

temperance inns, provided for men

a reading room of temperance material, a

cheap restaurant, and

lodgings. A contemporary temperance

reformer, the Reverend W. H.

Daniels spoke approvingly of the

"Woman's Church" organized

there, with its pastor, F. Janet Duty,

and her helpers, who had

created a parish of nearly 200 persons

by home visits and gospel

preaching "in true apostolic

fashion."25 This "Church" reflected the

Protestant ecumenicism and the more

relaxed standards of the

evangelism of the 1870s.26 Church

members were required only to

"give good evidence of conversion,

sign the temperance pledge, and

subscribe to articles of belief so

scriptural and undenominational

that they can be assented to by every one

of the Christian women

engaged in this work, notwithstanding

[they] represent ... five

different denominations."27

And yet these missionary efforts would

be for nothing if the poor

were left without food, shelter,

clothing, and employment, for they

would surely "lapse again into

wrong-doing," pointed out the Inn's

Grandison Finney to Billy Graham (New York, 1959), 160 ff; William G. McLoughlin,

Revivals, Awakenings, and Reform: An Essay on Religion

and Social Change in

America, 1607-1977 (Chicago, 1978), 141-45; Bernard W. Weisberger, They

Gathered

at the River: The Story of the Great

Revialists and Their Impact Upon Religion in

America (Chicago, 1958), 167 ff.

23. Charles H. Hopkins, The Rise of

the Social Gospel in American Protestantism,

1865-1915 (New Haven, 1940); Ahlstrom, A Religious History, 343.

24. Rose, Cleveland, 362.

25. W. H. Daniels, The Temperance

Reform and Its Great Reformers (Cincinnati,

Chicago, and St. Louis, 1878), 349-51.

26. Weisberger, They Gathered, 170-71;

McLoughlin, Modern Revivalism, 169.

27. Daniels, The Temperance Reform, 352.

Temperance, Benevolence, and the

City 67

founders.28 Hence, the women

made efforts to find jobs for their

converts. During these early years, the

Non-Partisan Union also

distributed food, clothing, and

sometimes money in good philanthro-

pic style, a custom which they continued

through the years, espe-

cially at Thanksgiving and Christmas and

during hard times such

as the depression of 1893.

Underlying these activities was the

belief that men were more

intemperate and therefore in greater

need of conversion than

women. Reports of the spiritual rescue

of males were particularly

self-congratulatory, as in the story of

the man who "reformed from

drink, converted to Christ, and returned

home to his wretched wife

and mother" in 1874; or, some

twenty years later, of a young blade

who was on his way to the theater but

instead attended a gospel

service at Central Friendly Inn

"and before he left . . . had accepted

Christ"; not only that but he

returned later with his brother, who

did the same.29 If their

interest in men dwindled, it was not because

the women came to believe man's nature

any better, but because

other agencies such as the YMCA and the

Salvation Army dupli-

cated the Non-Partisan Union's efforts.

The chief concern of the Non-Partisan

Union was other women,

who, with children, were correctly

perceived as victims of male

intemperance30 In 1896 the

Non-Partisan Union president forceful-

ly articulated this perception:

Twenty two years ago this Union began an

organized warfare on behalf of

the women of Cleveland and its homes

against the saloon. This conflict has

been carried on with earnest persistence

because there is seen on every

hand the devastation of homes and the

wreck of woman's hopes ... and it

will be continued so long as mothers'

hearts are broken, children's lives

blighted, wives tortured and even killed

outright by the fiends which the

saloon produces.31

The Non-Partisan Union began its work

for women with the

establishment of Mothers' Meetings in

1875, at which lessons in

temperance, the gospel, and the domestic

arts were provided for

women in the neighborhood of the Inns.

These women, often the

28. WCTU, Cleveland, Annual Report, 1877,

17.

29. WCTU, Cleveland,

"Records," August 1, 1874; WCTU, Cleveland, Annual Re-

port, 1893, 53.

30. Clark, Deliver Us, especially

13-34.

31. WCTU, Cleveland, Annual Report, 1896,

40.

68 OHIO HISTORY

"wives of inebriates" or

drunkards themselves, received "sisterly

sympathy" and advice on how to

"order their homes and help their

husbands on the way back to

respectability and competence."32 The

1879 Annual Report noted proudly

(and parochially) that five atten-

dants at these meetings "were

formerly Catholics, but now trust in

Christ for salvation."33

Like other Victorian women, Non-Partisan

Union members be-

lieved that women were victims also of

male lust so that much of

their effort was directed toward social

purity work, particularly the

establishment of homes and residences

for female sexual victims, or

potential victims.34 In 1878

the Non-Partisan Union founded "The

Open Door" for friendless and

homeless women, many of them un-

wed mothers. The annual reports kept

careful track of these unfor-

tunates, as in 1880 when were listed

"213 inmates; children, 27;

respectable working women, 89;

inebriate, vagrant, and disreput-

able women, 90."35 The

organization acted as an employment agency

for inmates, who stayed at The Open Door

only until work-pri-

marily domestic service-could be secured

for them. When work

could not be found, perhaps because

respectable Cleveland house-

wives were reluctant to employ

"fallen women," inmates were sent

to the Cleveland Infirmary or the City

Hospital. Some, alas, "re-

turned to the evil life."36 Urban

life presented very real dangers to

young, innocent women from the

countryside or Europe, and pathet-

ic tales of misfortune filled The Open

Door's annual reports. As, for

example, of a German woman whose family

turned her out because

she had an illegitimate child, and for

whom The Open Door provided

a job and shelter for herself and her

child, and a funeral for the child

when it died.37

In 1890 The Open Door was closed,

possibly because it could offer

so few services that its track record

for reclamation of souls and

bodies was pretty dismal. To remedy

this, the Non-Partisan Union

very soon opened a Training Home For

Friendless Girls, which was

to offer not just shelter but a

Christian home atmosphere and train-

ing for "honest" jobs to

prevent women from falling into prostitu-

32. Ibid., 1878, 13.

33. Ibid., 1879, 28.

34. David J. Pivar, The Purity

Crusade: Sexual Morality and Social Control, 1868-

1900 (Westport, Conn., 1973), 166. On the institutional

response of middle class

women to prostitution, see also Mark

Thomas Connelly, The Response to Prostitution

in the Progressive Era (Chapel Hill, 1981), especially 36 ff.

35. WCTU, Cleveland, Annual Report, 1880,

63.

36. Ibid., 1883, 29.

37. Ibid., 1888, 50-51.

Temperance, Benevolence, and the

City 69

tion. The "girls" were to be

either "respectable but homeless" or

"unrespectable" referrals from

police courts, prisons, and city hos-

pitals. The training again was primarily

in domestic service, but by

1899 so many of the girls wished to work

in offices and stores that it

became difficult to teach them

"household duties."38

The Training Home grew out of the

Non-Partisan Union's experi-

ence with The Open Door and with prison

visitation, an activity

which engaged members from the early

1880s until the turn of the

century.39 The Non-Partisan

Union women prayed with their erring

sisters that they might see the light

and lead better lives but also

visited former prisoners in their homes

and tried to help them in

practical ways, most notably the

Training Home itself.

The other area of chief concern was

children, for whom a wide

variety of classes and activities was

developed. The first classes for

little girls were organized in 1882;

these were sewing classes and

"kitchen gardens." The sewing

classes were justified as temperance

work because many of the girls came from

"homes ruined by drink,

perhaps where both father and mother are

habitual drunkards."40

Presumably the child would be taught

temperance principles along

with the use of a needle, go home, and

convert her parents. The

conversion aim is also seen in a special

sewing class for "Hebrew"

girls, in which there were open attempts

to proselytize.41 Sewing, of

course, was considered a practical

skill, useful for a woman's private

and work lives. The Kitchen Gardens had

the same practical goal: to

teach girls over six "womanly

ways" of making their own homes

attractive and also marketable skills

such as cooking and

laundering.42 The girls sang

hymns as they worked and also tunes

such as this one: "As quick as

you're able/ Set neatly the table./ And

first lay the table cloth square/ And

then on the table, bright and

clean table cloth/ Napkins arrange with

due care."43 These are cer-

tainly "conservative" domestic

activities, but they were also realis-

tic, given the job opportunities for

working class girls.

For boys, the activities were more

varied. There was early estab-

38. WCTU, Cleveland,

"Records," December, 1899. Women prison reformers estab-

lished similar regimens in separate women's prisons;

see Estelle Freedman, Their

Sisters' Keepers: Women's Prison Reform in America,

1830-1930 (Ann Arbor, 1981),

54-55.

39. See Freedman, Their Sisters'

Keepers, on prison visitation as a stimulus for

prison reform also, 22 ff.

40. WCTU, Cleveland,

"Records," March 1882, 26.

41. WCTU, Cleveland, Annual Report, 1889,

43.

42. Ibid., 1882, 44-47.

43. Ibid., 1892, 47.

70 OHIO HISTORY

lished at Central Friendly Inn a reading

room for boys, as an

alternative to the saloon and the

street, by the Young Ladies

League for Temperance Education, an

auxiliary to the Non-

Partisan Union. Originally the room

contained only temperance

literature; eventually it also had

popular juvenile reading material

such as St. Nicholas magazine and

Harper's Young People44 The

Woodland Avenue Temperance Reading Room

had nightly meetings

with singing and prayer for boys, talks

on temperance and hygiene,

entertainments such as sleigh rides, and

classes in arithmetic and

geography.45 By 1900

Non-Partisan Union institutions provided a

full range of services for boys, much

like a settlement; but unlike a

settlement, the goal remained the

preparation of "our boys not only

to become sober, intelligent, and worthy

citizens, but also the lov-

ing, loyal disciples of Him who was once

the Boy of Nazareth."46

The religious/secular thrust of these

activities was often given

justification by the Non-Partisan

Union's public statements about

its purposes, statements which did not

change dramatically over the

quarter of a century discussed in this

paper. The second Annual

Report proudly announced: "Hundreds of families have been

visited;

drinking husbands plead with; suffering

wives encouraged; the sick

have been cared for; the dying led to

Christ; the hungry fed, the

ragged clothed; .. . Relief has been

afforded to the destitute."47 Every

March, for most of these years, at the

Non-Partisan Union's annual

meeting, the number of gospel meetings

and conversions were tal-

lied up next to the number of sewing

classes and gymnasiums, the

number saved side by side with the

number salvaged and served.48

The women of the Non-Partisan Union made

no practical distinc-

tions between the spritual and secular

in their day-to-day activities.

As for the Woman's Christian

Association, "everything was reli-

gious."

This dual thrust is reflected also in

the tactics used by the Non-

Partisan Union, individual reclamation

through moral suasion and

social and public change effected by

legislation. Mary Earhart Dil-

lon has described a shift "from

prayer to politics" by Frances Willard

44. Annual Report of the Young Ladies

League for Temperance Education, 1888-

1889, in Linda Thayer Guilford Papers,

MS 484, in the Western Reserve Historical

Society, Cleveland, Ohio.

45. WCTU, Cleveland, Annual Report, 1888,

39-40.

46. Ibid., 1900, 58.

47. Works Progress Administration of

Ohio, Annals of Cleveland, vol. XVIII

(1875), 8.

48. WCTU, Cleveland, Annual Report, 1877;

Annual Report, 1888, 89-90.

|

Temperance, Benevolence, and the City 71 |

|

|

|

and the national WCTU,49 and although there is a shift in emphasis in the direction of politics in Cleveland, the Non-Partisan Union applied both tactics throughout this period. As early as the summer of 1874 these women canvassed the city to urge men to vote for a temperance issue.50 In 1883 the group supported passage of two state temperance laws to end "the liquor traffic . . . which is the direct cause of nearly all the crimes committed."51 After 1893 the local Anti-Saloon League, an overtly political pressure group, shared the Non-Partisan Union's offices (and often did not pay their share of the rent). In 1895 the Non-Partisan Union cooperated with the Cleveland Civic Federation and the Good Citizenship League "for the promotion of better city government."52 In 1896 the President's address explained that the group supported a state prohibition amendment and Sunday closing laws because moral suasion alone had not been effective.53 The Non-Partisan Union also supported the temperance ballot

49. Dillon, From Prayer to Politics; Bordin, Woman and Temperance, 13 ff. 50. WCTU, Cleveland, "Records," August 1, 1874. 51. WCTU, Cleveland, Annual Report, 1883, 11. 52. Ibid., 1895, 44. 53. Ibid., 1896, 41. |

72 OHIO HISTORY

and the school ballot for women, but, as

noted, did not support the

general suffrage. This was apparently

because the membership was

divided, and the group preferred to

avoid the issue rather than split

over it.54 This stance may

have meant that the Cleveland group

could not be as overtly political as it

may have wanted, or as other

WCTU's could be, or it may have meant

that the Cleveland women

simply did not find politics the only

effective route to their goals.

There was never any open disagreement,

however, on the import-

ance of the gospel approach. The

Non-Partisan Union had its begin-

nings in "praying bands."

Every meeting, large or small, began and

ended with "devotions," a

hymn, some words from the Gospels. Pub-

lic meetings were always held in

churches, which, sometimes only

through their Sunday Schools or ladies'

auxilaries, made small

financial contributions to the

Non-Partisan Union. The women

thought of their temperance work as

divinely inspired and sus-

tained: ". . . we are called, in

the providence of God, to labor," they

proclaimed in their constitution.55

As the nineteenth century ended,

however, there were hints that

the religious goals were becoming

submerged by or confused with

the welfare or philanthropic orientation

of the Non-Partisan Un-

ion's work. The opening devotions of the

1889 annual meeting stres-

sed that this work must have "as

the foundation, in it all, Jesus

Christ, not simply as the perfect

Example, but as the atonement and

only sufficient sacrifice . . . our

human work resting on his divine,

finished, sacrificial work."56

In the same vein, in 1901, members

were enjoined to follow the example of

Christ, who employed "not

material but spiritual forces" in

His work of rescue, and to use "all

moral and spiritual forces at [their]

command, assured that He ...

will come when His rule is established

in individual hearts."57

But the handwriting was on the wall, and

the religious impulse

would wane in the next quarter of a

century, a casualty of the

growing secularization of society and

the professionalization of phi-

lanthropy in the twentieth century. In

1906 the Non-Partisan Un-

ion still tallied up 208 Gospel

meetings; it maintained two centers of

gospel and temperance work, Central

Friendly Inn and Wilson Ave-

nue Industrial Institute, and the

Training Home. But a new institu-

tion, the Eleanor B. Rainey Institute, a

center for clubs and classes

54. Ibid., 45.

55. Ibid., 1878, 4.

56. WCTU, Cleveland,

"Records," March 28, 1889.

57. WCTU, Cleveland, Annual Report, 1901,

29-30.

Temperance, Benevolence, and the

City 73

for young people, had little explicitly

religious activity.58 By 1911

Central Friendly Inn, long the most

evangelical of Non-Partisan

Union institutions, housed a Babies'

Dispensary, a kindergarten, a

branch of the Tuberculosis Dispensary,

and public baths; the only

religious services were Sunday vespers.59

In 1913 the Non-Partisan Union became a

member of the Cleve-

land Federation for Charity and

Philanthropy, and by 1918 only the

scientific temperance instruction and

the Sunday School commit-

tees testified to the earlier

religiousity. In 1924 Central Friendly

Inn, with its gymnasium, kindergarten,

lodgings, and playground,

moved into a larger building in a

neighborhood of blacks, Italians,

and other Eastern Europeans. "Our

aim," stated the Annual Report,

is "to help these people forget

class and racial prejudice and to work

and live together for their common

good."60 The Inn had become, in

effect, a settlement, as it is today.

In 1928 the Non-Partisan Woman's

Christian Union became the

Woman's Philanthropic Union, a small

group which simply admin-

istered the trust funds and investments

which partially sustained

the Inn, Rainey Institute, the Training

Home, and the Mary Ing-

ersoll Club, which housed working women.

Having lost the religious

impulse which gave it birth and which

made it unique, the Non-

Partisan Union died, and the secular

orientation took over.

Except for suffrage, this Cleveland

group, despite its disaffiliation

after 1885, supported the same kinds of

activities and values that

the national WCTU did. Yet one cannot

arrive at generalizations

about the national or about the great

mass of temperance advocates

on the strength of this one local

chapter. By the same token, this

group is a reminder that conclusions

should not be drawn about the

politics and ideology of all WCTU

members on the basis of national

records and the national leadership. One

Frances Willard does not a

temperance movement make.

The founders of the Woman's Temperance

League of Cleveland in

1874 saw themselves first as Protestant

crusaders, as the doers of

God's will, working as best they could

in His world to save both

bodies and souls. They are evidence of

the importance of religion in

the lives of nineteenth century women

and the importance of women

to nineteeth century religion. If the

prayer books of 1874 became the

checkbooks of 1928, this was an

unintended irony.

58. Ibid., 1906, 37-42; 45.

59. Ibid., 1911, 23.

60. Ibid., 1926, unpaged.