Ohio History Journal

RUTH BORDIN

"A Baptism of Power and Liberty"

The Women's Crusade of 1873-1874

Throughout the winter of 1873 and 1874

a grass roots women's tem-

perance crusade swept through Ohio, the

Midwest and parts of the

East. Thousands of women marched in the

streets, prayed in saloons

and organized their own temperance

societies in hundreds of towns

and cities of the American heartland.

The Crusade had an immense

impact on these women. Cut loose from

the quiescence and public

timidity that was their prescribed role,

the Crusade gave to many

American women a new sense of identity,

a taste of collective power

and an acquaintance with the larger

world of the public platform.

"We have had no wonderful crusade

in England" observed the promi-

nent British temperance worker Margaret

Parker to her American sis-

ters, a decade later, "no such

baptism of power and liberty." Parker

reported that unlike their American

sisters, English women still be-

lieved that "woman's voice should

only be heard within the four walls

of her own home."1

Parker correctly saw the Crusade as a

watershed in the participa-

tion of American women in the temperance

movement. Before the

Crusade of 1873-1874, American women

(much like their British

counterparts) played a relatively minor

and passive role, but for twen-

ty-five years afterwards, until the

growth of the Anti-Saloom League

at the turn of the century, women

provided the major and most crea-

tive leadership for the temperance

movement. Their organization,

the Woman's Christian Temperance Union

(WCTU), organized as a

Ruth Bordin is currently a lecturer in

the history department at Eastern Michigan Uni-

versity and previously served for ten

years as Curator of Manuscripts at the Michigan

Historical Collections, University of

Michigan. Another version of this paper was pre-

sented at the Conference on the History

of Women, St. Catherine's College, in October

1977.

1. Union Signal, December 20, 1883, 6. Temperance and Prohibition

Papers, Na-

tional Headquarters file, WCTU (joint

Ohio Historical Society-Michigan Historical Col-

lections-WCTU microfilm edition, Union

Signal series, roll 1) (hereafter cited as Union

Signal). Margaret Parker was a Scots woman who served as

president of the first inter-

national Woman's Christian Temperance

Union in 1876.

394 OHIO HISTORY

result of the Crusade, in turn provided

the single most effective outlet

for the growing women's movement.

The Crusade began almost accidentally.

On December 22, 1873, a

professional lecturer, Diocletian Lewis,

well into his fall tour, gave a

public address called "Our

Girls" at the Music Hall in Hillsboro, Ohio.

Educated at Harvard and trained in

homeopathic medicine, Lewis

was a leading advocate of physical

exercise and an active life for

women and an ardent temperance man. His

appearance in Hillsboro

was part of the regular winter course of

lectures sponsored by the

local lyceum association. Lewis had a

free day before he was to ap-

pear in a neighboring town, and someone

in his audience suggested that

he give a temperance lecture in

Hillsboro the next evening, Sunday

the twenty-third. Because the cause was

one in which he thoroughly

believed he willingly agreed. Lewis

called his temperance address,

"The Duty of Christian Women in the

Cause of Temperance."

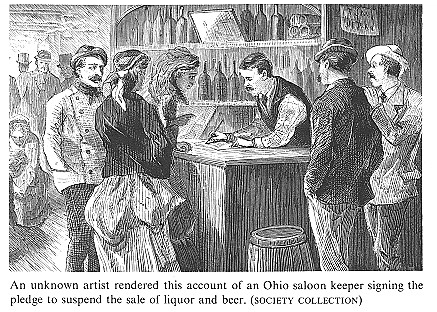

That evening Lewis told his customary

story about his own family.

Forty years ago his father had been a

drinking man, and his mother,

sorely distressed by his father's

regular patronage of a local saloon

in Saratoga, New York, had appealed in

desperation to the owner to

cease selling spirits, had prayed in the

saloon with several of her

friends, and had actually succeeded in

getting the saloon keeper to

close his business. Lewis suggested that

if his mother had been able

to do this many years ago, why could not

the women of Hillsboro do

the same in 1873.

By that December evening he had made his

appeal about the

power of women's prayers in the grog

shops approximately three

hundred times, and the plan he outlined

had already been tried in some

twenty instances before. As early as

1858, he inspired fifty women to

march praying into the saloons of Dixon,

Illinois. They continued

their non-violent assault for six days

until all the community's saloons

had closed. Two months later women tried

the scheme in Battle

Creek, Michigan. One of its more

successful applications occured in

Manchester, New Hampshire, in 1869.

Lewis had made the same

speech ten days before in Fredonia, New

York. Over two hundred

women followed his suggestion and

marched to the saloons the fol-

lowing day for prayer and song. The next

morning they organized a

temperance society, but they did not

continue their marches.2

Before Hillsboro the results of Lewis'

appeal had always been

2. Mary Eastman, Biography of Dio

Lewis (New York, 1891), 24-60; see also Fran-

cis M. Whitaker, "A History of the

Ohio Woman's Christian Temperance Union, 1874-

1920" (Ph.D. dissertation, The Ohio

State University, 1971), 128-32.

Women's Temperance Crusade 395

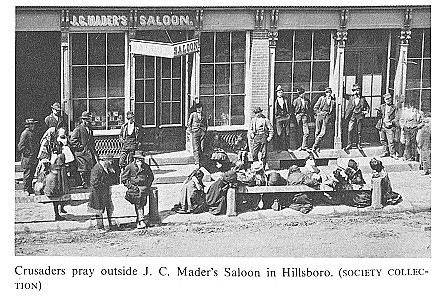

temporary and local, but this time his

appeal fell on fertile ground.

The women in the audience took up the

challenge with enthusiasm.

Early the next morning nearly two

hundred lined up outside the church

in a column of twos, the shortest

leading the way, and began to

march on several local saloons singing

"Give to the Winds Thy

Fears." Marching that Christmas Eve

day on the cold and sunless

streets of Hillsboro, these women

touched off a mass movement

which soon engulfed hundreds of towns

and cities in Ohio, the Mid-

west, and, to a lesser extent, in the

Northeast and West.3

The typical crusade began with a public

meeting in a church or

hall where an audience, composed chiefly

of women, prayed together

and listened to temperance speakers,

frequently female. Within a

day

or two they deployed throughout the community for "street

work," which could involve the

methodical circulation of temperance

petitions or, more spectacularly, the

march of a mass delegation to

confront one or more saloon keepers.

Almost never were they accom-

panied by sympathetic men, and in the

larger cities hostile crowds of-

ten harrassed the group. When crusaders

entered a saloon they usually

prayed together for a moment, then asked

the proprietor to pour out

his stock and close his business. Mark

Twin described such a con-

frontation. Accosting the saloon keeper,

the crusaders would:

offer up a special petition for him; he

has to stand meekly there behind his

bar, under the eyes of a great concourse

of ladies who are better than he is

and are aware of it, and hear all the

iniquities of his business divulged to the

angels above, accompanied by the sharp

sting of wishes for his regenera-

tion ... If he holds out bravely, the

crusaders hold out more bravely

still . . .4

Within three months of Hillsboro, such

campaigns had successfully,

if temporarily, closed thousands of

saloons and driven the liquor busi-

3. Among the many descriptions of the

crusade are: Annie Wittenmyer, History of

the Woman's Temperance Crusade (Philadelphia, 1878); Eliza Jane Thompson, Hills-

boro Crusade Sketches and Family

Records (Cincinnati, 1906); Matilda

Carpenter,

The Crusade: Its Origin and

Development at Washington Court House and its Results

(Columbus, 1893); and W. C. Steel, The

Woman's Temperance Movement, A Concise

History of the War on Alcohol (New York, 1874). Most of the issue of December 20,

1883, of the Union Signal, the

official organ of the Woman's Christian Temperance Union,

is devoted to reminiscences and

evaluations of the Crusade. T. A. H. Brown, reporter

for the Cincinnati Gazette, who

covered the Crusade for his paper, wrote a long, par-

tially eye-witness account called

"A Full Description of the Origin and Progress of the

New Plan of Labor by the Women Up to the

Present Time," which appeared in Jane

E. Stebbins, Fifty Years' History of

the Temperance Cause (Hartford, 1876). See also

Dio Lewis in his Prohibition A

Failure: The True Solution of the Temperance Question

(Boston, 1875), and Eastman's Dio

Lewis.

4. Union Signal, June 4, 1885, 5.

396 OHIO

HISTORY

ness out of more than 250 American

communities. Women crusaders

took to the streets in 130 Ohio towns

and cities, Michigan had thirty-

six crusades, Indiana thirty-four,

Pennsylvania twenty-six, New Jersey

seventeen. The movement spread to

twenty-three states in all.5

While the Crusade began in small towns

and cities in agricultural

areas, it soon spread to a number of

larger cities. Cleveland, Cincin-

nati, Chicago, Philadelphia and Brooklyn

are among the metropoli-

tan centers which experienced crusades.

Before summer was over,

750 breweries closed. The production of

malt liquor dropped over five

and one-half million gallons in 1874,

and federal excise taxes dropped

sharply in some districts.6 Although

most saloons were open again

by fall, and the results were

transitory, this was the first women's

mass movement in American history. Women

were taking to the

streets in significant numbers using

methods they had never before

used on such a scale.

Why did a women's temperance crusade

catch fire during the winter

of 1873-1874? Intimately linked to

revivalism and abolitionism, tem-

perance had become a national issue as

one of the great antebellum

reform movements that swept the North in

the Jacksonian era. By

the 1830s some temperance advocates had

turned from a perfectionist

concern with individual abstinence to an

advocacy of legal prohibi-

tion, and several states adopted

statutes prohibiting or regulating the

sale of alcohol in the years before the

Civil War. Temperance agita-

tion declined during the great conflict,

but quickly revived in the

reform

atmosphere that accompanied the early reconstruction years.7

Membership in the Ohio branch of the

Independent Order of Good

Templars, which accepted women on an

equal basis with men, rose

from 3,755 in 1865 to nearly 28,000 in

less than three years.8

5. Ibid., September 30, 1923, 4. The total number is probably an

underestimate.

Elizabeth Putnam Gordon, Women Torch

Bearers, The Story of the Woman's Chris-

tian Temperance Movement (Evanston, 1924), 7, puts the figure at 250. Actually

there

were more. Accounts of 255 individual

crusades appear in Wittenmyer's Crusade His-

tory and that record is incomplete.

6. Mary Earhart, Frances Willard:

From Prayers to Politics (Chicago, 1944), 141;

Norton Mezvinsky, "White Ribbon

Reform: 1874-1920" (Ph.D. dissertation, 1958),

54-60. The panic of 1873 may have been

responsible for some of this drop in produc-

tion, but some of it is certainly

traceable to the Crusade.

7. Alice Tyler, Freedom's Ferment:

Phases of American History to 1860 (Minnea-

polis, 1944), chapter 13, contains a

concise history of the early temperance movement.

John Allen Krout's The Origins of

Prohibition (New York, 1925) is the classic work on

the period. Norman Clark's Deliver Us

From Evil (New York, 1976) is the best inter-

pretative account and a major

contribution to the understanding of the temperance

movement as a whole.

8. Whitaker, "Ohio WCTU,"

111-12.

|

Women's Temperance Crusade 397 |

|

|

|

A more immediate impetus toward reform came with Ohio's 1873- 1874 constitutional convention that heatedly debated the liquor li- cense issue and the regulation of the liquor traffic in general. At this time the state did not license liquor dealers and forbad the selling of spirits in saloons, where only beer and wine could be vended. More- over, under the existing Ohio law, an individual could be refused per- mission to buy liquor or beer if a relative asked that he not be served. Liquor interests wanted the convention to license saloons to sell spirits, but Ohio's temperance forces furiously opposed such regu- lation on the grounds that state licensing of drink implied state ap- proval of intemperance and drunkenness. Divided over the issue, the constitutional convention shifted resolution of the licensing amend- ment to the voters. In the August 1874 election Ohioans defeated li- censing, but at the same time turned down the new constitution which would have enforced the decision. Although the end result was a frustrating stalemate, the public debate had kept the temperance question in the public mind all through 1873 and 1874.9 However, none of this directly explains why the temperance cru- sade was a women's movement of such immense proportions. Before

9. Charles A. Isetts, "The Woman's Christian Temperance Crusade of Ohio" (M. A. thesis, Miami University, 1971), 49; also Whitaker, "Ohio WCTU," 124-25, 274. |

398 OHIO HISTORY

the early 1870s women's role in the

temperance agitation had always

been subordinate to that of men,

especially in the public or political

realm. This reflected the nineteenth

century's dominant sexual ideol-

ogy which assigned to men and women

sharply defined sexual

"spheres." Men functioned in

the world of politics and commence;

women presided over the spiritual and

physical maintenance of home

and family.10 Their role at

home or in society was to provide moral

suasion and good example. As long as

temperance agitation emphasized

individual redemption and personal

abstention, women worked easily,

if quietly, within the movement, but

they were not to participate in its

public phases. When they sought to play

a larger role, they were quickly

rebuffed. In 1852, for example, Susan B.

Anthony, denied the right to

speak at a convention of New York

temperance societies, organized the

first state society of women temperance

advocates.11

But the drink issue itself proved

subversive to the maintenance of

a hard division between the sexual

spheres. Once the temperance

movement had shifted its attention from

moral suasion to legislative

prohibition, reformers directed much of

their effort toward closing the

public saloon, whose numbers were

growing rapidly in the generally

prosperous era immediately after the

Civil War. By 1873 Ohio sup-

ported as many as one such establishment

for every 150 or 200 people.

If one excludes women, children and

teetotaling men, then each saloon

catered to an average of only thirty

adult men.12

Temperance advocates in general, and

women in particular, held the

saloon to be a mortal threat to home and

hearth. Only a minority of

families were actually undermined by the

poverty or debauchery of

drunken husbands, but almost all women

felt threatened by the ag-

gressively male atmosphere of the saloon

and tavern. It represented

an alternative nexus of sociability,

separate from and often counter-

posed to, the circle of family,

relatives and friends over which women

traditionally presided. In a society in

which women were still economi-

cally and socially dependent on men,

these drinking establishments

eroded the traditional ways of life that

lent some dignity and stability

10. The best recent analyses of

"women's sphere" are found in Barbara J. Berg,

The Remembered Gate: Origins of

American Feminism: The Woman and the City,

1800-1860 (New York, 1978), 67-74, and Nancy Cott, The Bonds

of Womanhood:

"Womans Sphere" in New England, 1780-1835 (New York, 1978), Jed Dannenbaum

analyzes this ideology in terms of the

temperance movement in his "Woman and Tem-

perance: The Years of Transition,

1850-1870," a paper delivered at the Conference on

the History of Women, St. Paul, October

1977.

11. Ida Husted Harper, The Life and

Work of Susan B. Anthony, I (Indianapolis,

1899), 64-66.

12. Whitaker, "Ohio WCTU,"

143.

Women's Temperance Crusade 399

to their social relationships.13 The

sudden panic of 1873, which left

rural areas and small towns in a

troubled condition, probably rein-

forced the sense of social disorder and

economic instability which

women already identified with the

growing saloon culture.

To many women, therefore, participation

in the post-Civil War

temperance movement took place on a

basis which did not funda-

mentally alter the ideology that held

women responsible for, and

confined to, home and family. Yet at the

same time, the activism

and larger public role that

characterized women's temperance work

in this era so broadened the narrow

definition of women's traditional

"sphere" as to make it, among

advanced women, an increasingly ana-

chronistic concept. Thus thirty women

were among the five hundred

men who attended the founding convention

of the National Prohibition

party in 1869. Women were accepted as

equal members of the Inde-

pendent Order of Good Templars, and

Martha Brown, later a founder

of the Woman's Christian Temperance

Union, became a member of

the Templar executive board in 1867 and

Grand Chief Templar of

Ohio in 1872.14

The women's crusade represented a new

stage in this expansion of

the legitimate sphere of female

activity. Women now joined the tem-

perance movement in numbers that

eclipsed their participation in

any previous reform. In Hillsboro 200

women marched in a town

whose total population was less than

2,000. The village of Franklin

had fifty marching against the liquor

traffic out of 2,500. In Adrian,

Michigan, approximately 1,000 women out

of the city's population of

8,000 participated in some way. Bands of

150 women were sent out

daily over a period of several months.

Larger cities too felt the pull: in

Chicago that spring 14,000 Crusaders

petitioned the city council for

Sunday closing of saloons.15

For the most part these crusaders came

out of the upper ranks of

their town and village society. Mark

Twin characterized them as

young girls and women who are "not

the inferior sorts, but the very

13. Clark, Deliver Us From Evil, 1-9;

also see for example Susan B. Anthony's

address to the National American Woman

Suffrage Association 2 1875, in which

she emphasized the extent to which women

suffered from drunkenness. As reprinted

in Aileen Kraditor, Up From the

Pedestal: Selected Writings in the History of Ameri-

can Feminism (Chicago, 1968), 159-61.

14. Whitaker, "Ohio WCTU,"

122-23; Frances Willard and Mary A. Livermore, eds.,

A Woman of the Century, Fourteen

Hundred Seventy Biographicsl Sketches of Lead-

ing American Women (Buffalo, 1893), 127-28.

15. Whitaker, "Ohio WCTU,"

140; Minutes, Ladies Temperance Union of Adrian,

in Michigan Historical Collections of

the Bentley Library; Frances Willard, Presidential

Address, Minutes, 1889, 99, WCTU

National Headquarters Historical Files (joint Ohio

Historical Society-Michigan Historical

Collections-WCTU microfilm edition, roll 3).

400 OHIO HISTORY

best in their villages

communities."16 In a study of ninety-five of the

original Hillsboro Crusaders who could

be identified, Charles A.

Isetts has shown that these women were

"socially and economically

the dominant force in Hillsboro at that

time." All were from house-

holds headed by men who were either

skilled craftsmen or in white

collar occupations. These families were

also the wealthiest in town,

and over 90 percent of the Crusader

households were native white

Americans of two generations standing or

more. They were the "upper

crust of their society."17

As a consequence of their high social

standing and their sense of

righteous womanhood, these crusaders,

like other reformers of the

era, felt a keen sense of the justice of

their cause and their own moral

superiority. Although few of the women

participating in the 1874 cru-

sades favored so radical a demand as

suffrage, they did believe their

work in the best interests of the entire

society; this explains the self-

confidence and tactical militance

displayed by these otherwise conser-

vative women. They marched in the

streets, formed picket lines to

prevent the delivery of liquor to

saloons, took down the names of the

patrons, and organized and addressed

mass temperance meetings. Even

though they saw this work as in defense

of a traditionally defined

women's sphere, the radical and public

methods they subscribed to

represented a real, if only partially

conscious, commitment to the idea

that women could legitimately function

in the public realm. Their work

was that of an effective pressure group,

and in many instances they

succeeded in forcing a male-dominated

society to yield to their demands.18

A minority of the crusade leaders had

already been active in public

life, especially in women's missionary

societies and in Civil War agen-

cies such as the Sanitary Commission and

the Freedmen's Bureau. Eliza

Stewart, who led the Springfield, Ohio,

crusade had acquired exten-

sive leadership skills while working

with the Sanitary Commission.

Putting this experience to new use,

Stewart brought praying bands into

court rooms, organized mass meetings,

and eventually became a

prominent temperance lecturer whose

skill on the podium was hailed

16. Union Signal, June 4, 1885,

5.

17. Charles A. Isetts, "A Social

Profile of the Woman's Temperance Crusade:

Hillsboro, Ohio," unpublished

manuscript.

18. See Aileen Kraditor, "Ideology

of the Suffrage Movement," in Barbara Welter,

ed., The Woman Question in American

History (Hinsdale, IL, 1971), 88-89; Kraditor,

Ideas of the Woman Suffrage Movement,

45-56; and Gerda Lerner, "New

Approaches

to the Study of Women in American

History," Journal of Social History, III (Fall,

1969), 53-62. Lerner argues that even

without the vote, women effectively used pres-

sure tactics to force political change.

Many of their methods were later adopted by

civil rights and other groups.

Women's Temperance Crusade 401

in Great Britain as well as in the

United States.19

But most of the leadership of the

Crusade had had no previous ex-

perience in the public realm outside the

home. Of the thirty late nine-

teenth-century temperance leaders

singled out for formal portraits in

Frances Willard's Women and

Temperance (twenty of whom had

participated in the crusade) over

half-eighteen in all-had had no pre-

vious experience outside the domestic

sphere. In a score of states

women who had previously led quiet

lives, who had always appeared

shy and subservient to their husbands,

were suddenly organizing, taking

to the streets, getting locked into

airless, smelly saloons, risking arrest

and generally behaving as if nothing in

their lives counted except their

dedication to the temperance movement.20

For example, Mary Wood-

bridge, mother of three by the time she

was twenty, had previously

devoted herself exclusively to her

family. When the Crusade came to

Ravenna, Ohio, she became overnight a

talented, moving speaker in the

evangelistic style. Within months

Woodbridge was in constant demand

as a platform lecturer, and in 1879 she

became president of the Ohio

WCTU.21

Eliza Thompson, who led the Hillsboro

Crusade, was the daugh-

ter of a governor, wife of a judge, and

a conservatively inclined house-

wife and mother. She reported that as

she first rose to speak "my

limbs refused to bear me," but when

the men who were present

left the room her strength returned.22 Although she long retained a

sense of public reticence, Thompson

nevertheless plunged into cru-

sade work in Ohio. In later years she

addressed audiences of hun-

dreds from public platforms as a WCTU

speaker. Another crusader

who moved quickly into public life was

Amy Fisher Leavitt, wife of a

Baptist minister, who joined the

movement when it was organized in

Cincinnati. There the police arrested

her briefly while she prayed on

the sidewalk in front of a saloon. As

the wife of a minister Leavitt

may have had previous experience in

leading prayer meetings, but she

had never before run afoul of the law.

However, she took incarcera-

tion in stride and later continued her

prayers and hymns for the bene-

fit of the inmates of the jail.23

19. Frances Willard, ed., Women and

Temperance (Hartford, 1883), 83-85.

20. Ibid. Of the ten temperance

leaders who did not participate in the crusade,

three were not Americans, three happened

to be abroad when the crusade took place,

and four were from areas of the

country-New England and the South-where few crusades

took places.

21. Ibid., 103-06. Also see

Scrapbook number 7, WCTU microfilm series, roll 30,

frame 405.

22. Thompson, Crusade Sketches, 61.

23. Willard, Women and Temperance, 28.

|

402 OHIO HISTORY |

|

|

|

The first-hand accounts of the Crusade cannot be read without feel- ing the excitement experienced by these women and their growing conviction that anything was now possible. The women themselves saw the Crusade as a watershed, an experience that changed their self-conception. They articulated these feelings at Woman's Christian Temperance Union conventions and whenever and wherever they gathered for the rest of their lives. An editorial in the Union Signal in 1889 asserted that the Crusade "meant a revolution in women's work and in thousands of women's lives." Eliza Stewart, writing in the same issue of the Signal, said as a result of the Crusade, women "who had not dreamed they held such rich gifts in their keeping, were found on pulpits and rostrums with burning words swaying great audiences." Mary Burt, later president of the New York State WCTU described how she made her first public expression in the form of a note to a Crusade leader, during the marches in Auburn, New York. She was soon giv- ing a public lecture.24 The Crusade had an emotional impact upon women participants equivalent to a conversion experience. It moved them toward feminist principles, even if they did not recognize them as such. Aileen Kradi- tor has suggested that the aims of the feminists, while they varied widely in terms of specific demands, in the last analysis can be sum-

24. Union Signal, December 2, 1889, 5-9. |

Women's Temperance Crusade 403

marized as the demand for autonomy.25

Certainly these crusaders

shared this perception. They saw their

movement as trying to change

an aspect of society which directly

affected them as women, and they

felt they had a right to work publicly

in the cause.

Later the crusaders interpreted their

participation as part of a pro-

cess that helped them realize their true

potential as women for the

first time. On its tenth anniversary in

1883, the WCTU commemo-

rated the Crusade at length. WCTU

suffragist Mary Livermore, argued

that the advancement the Crusade gave to

temperance was far less

important than the movement's effect in

unifying women, giving them

moral courage and teaching them the

power of association. WCTU

president Frances Willard thought the

Crusade "taught women their

power to transact business, to mold

public opinion by public utter-

ance, and opened the eyes of scores and

hundreds of women to the

need of the Republic for the suffrage of

women and made them willing

to take up for their homes and country's

sake the burdens of that citi-

zenship they would never have sought for

their own."26

In response to the Union Signal's query,

"What has the Crusade

done for you?" anonymous

rank-and-file crusaders adopted much

the same perspective as leaders

Livermore and Willard. They expressed

the crusade's meaning to them in terms

of personal growth and develop-

ment. It "started me into an active

thinking life"; it gave me "broader

views of woman's sphere and

responsibility" reported two participants.

One said that because of the crusade she

"developed a new and grander

purpose." Another recalled that the

crusade "opened doors of opportu-

nity and tender-hearted

fellowship." Still another wrote to the paper that

the Crusade "brought me from the

retirement of my home into public

work." Finally, reported one

participant, "the Crusade taught women

to do noble deeds, not dream them."27

In effect, answered these middle-

class, church-going women, ten years

after the event, the Woman's

Temperance Crusade of 1874 had raised

their consciousness.

As the country's largest and most

influential nineteenth-century

women's organization, the WCTU reflected

the new level at which

women now sought to participate in

public life. Founded in 1874 as

the institutional expression of the

energies unleashed by the Crusade,

the WCTU grew to more than 150,000 dues

paying members by 1893.

Its strength remained substantial in the

Midwest, but the WCTU

25. Kraditor, Up From the Pedestal,

7-9.

26. Union Signal, December 20,

1883, 3; Mary Earhart, Frances Willard, From

Prayer to Politics (Chicago, 1944), 143; see also Frances Willard's

introduction to

Wittenmeyer's Crusade History, 15-21.

27. Union Signal, December 20,

1883, 12.

404 OHIO

HISTORY

had chapters in every state and major

city in the nation. Like the

temperance crusaders of 1873 and 1874,

the WCTU's staunch defense

of home and family appealed to the

conservative instincts of middle-

class women, but the Union so

dramatically broadened the arena in

which to carry out this program as to

virtually shatter for thousands

the traditional bonds of womenhood.

Under Frances Willard's apt

slogan "Do Everything," the

WCTU endorsed women's suffrage by

1883 and came out for a staggering array

of other reforms. In addition

to prohibition, the WCTU supported

research into the causes of alco-

holism, established kindergartens, paid

the salary of municipal police

matrons and aligned itself with the

farmer and labor insurgencies of

the 1880s and 1890s.28

More than any other single event in

nineteenth-century American

history, the Woman's Temperance Crusade

touched the lives of tens

of thousands of women and legitimized

for them a new and expanded

role in civil life. It took women out of

the home, taught them to con-

front social problems directly, and

showed them there were ways to

make an impact on society even without

the vote. In practice, if not

always in terms of formal ideology, the

Crusade helped subvert the

nineteenth-century idea that women

function in a sphere separate

from that of men and narrowly confined

to home, family and religion.

As Mary Livermore later put it:

"That phenomenal and exceptional

rising of women in Southern Ohio ten

years ago floated them to a

higher level of womenhood. It lifted

them out of a subject condi-

tion . . . to a plateau where they saw

that endurance had ceased

to be a virtue."29 They

had experienced their baptism of power and

liberty.

28. Joseph R. Gusfield, Symbolic

Crusade: Status Politics and the American Tem-

perance Movement (Urbana, 1963), 76-79; for a description of the way in

which the

WCTU's home-based ideology introduced

heretofore conservative women to extra-

domestic, even feminist, concerns, see

Anne Firor Scott, The Southern Lady: From

Pedestal to Politics, 1830-1930 (Chicago, 1970), chapter 6; Ellen DuBois provides an

excellent analysis of the relationship

between the suffrage movement and the WCTU

in "The Radicalism of the Woman

Suffrage Movement: Notes toward the Recon-

struction of Nineteenth-Century

Feminism," Feminist Studies, I (1975), 63-71.

29. Union Signal, June 4, 1885, 5.