Ohio History Journal

ROBERT A. WHEELER

Land and Community in Rural

Nineteenth Century America:

Claridon Township, 1810-1870

In 1812 Horace Taylor of Hartland,

Connecticut, traveled to Ohio to

buy and settle lands in the Western

Reserve of Connecticut on the

Trans-Appalachian frontier. He chose a

relatively new township in the

heart of the Reserve later called

Claridon in Geauga County. There in

the western portion he located his

farm, helped found the Congrega-

tional church, and established one of

the backbone families of the

township. Ten years later Nathaniel

Mastick arrived from Vermont and

started a farm in Claridon's eastern

portion. His family also became

one of the backbone families of the

township.

In some ways these two settlers were

typical of the two major

migrant groups who peopled the northern

portion of the Trans-

Appalachian frontier. Initially, most

settlers came to northern Ohio

directly from their ancestral homes in

New England just as Taylor had

done, and for a number of years these

pioneers attracted other family

members and associates to their new

settlements. As this group

declined after 1820, a new group, part

of what Malcolm Rohrbough has

called the "first great

migration" of the Trans-Appalachian frontier,

increased the volume of pioneers.1 Many

of them had moved from old

New England after the Revolutionary War

and established new homes

in frontier areas of Vermont, New

Hampshire, and New York. Some,

like the Masticks who moved from Connecticut

to Vermont, became

disenchanted with these homesteads, saw

opportunity further west in

an area settled by New Englanders, and

moved again to Ohio. Both

groups mingled throughout northern

portions of Ohio, Indiana, and

Illinois. Both Taylor and Mastick were

also typical because they

Robert A. Wheeler is Associate Professor

of History at Cleveland State University.

1. See Malcolm J. Rohrbough, The

Trans-Appalachian Frontier: People, Societies,

and Institutions, 1775-1850 (New York, 1976), 157-91 (hereafter cited as Rohrbough,

Frontier).

102 OHIO HISTORY

brought with them a set of regional

values characterized by their

Yankee-Puritan heritage.2 The

township they settled was typical of the

northern frontier in superficial

demographic and economic ways, and

its gradual integration into regional

and national contexts can be

precisely traced. The picture painted by

these indicators implies that a

homogenous, cohesive New England-New

Connecticut society devel-

oped in Claridon township. But closer

analysis of land records, maps,

church records, and especially diaries,

reveals a hidden and significant

division in neighborhood patterns and

social networks. These layers

meant that the Taylors and the Masticks

and the groups they symbolize

became part of separate subcultures

within Claridon which rarely

mixed.3

In order to explain how these

developments took place, the demo-

graphic and economic context which

produced the smokescreen of

homogeneity needs to be explained. Also

necessary is a closer exam-

ination of the settlement patterns and

the evolution of local township

centers which begin to suggest the

emergence of subcultures. Finally,

an analysis of church affiliation,

residence, and social networks

confirms the virtual bifurcation of

Claridon by the 1860s.

I. Population

During the era of the Trans-Appalachian

frontier, from its opening at

the beginning of the Revolutionary War

to its closing seventy-five years

later, thousands of migrants flooded the

West. As they founded new

2. Rohrbough, Frontier, 66, 150,

152; Thomas J. Schlereth, "The New England

Presence on the Midwest Landscape,"

The Old Northwest, 9 (Spring, 1983), 128-42

(hereafter cited as Schlereth, "New

England Presence"); Kenneth V. Lottich, "Cultural

Transplantation in the Connecticut

Reserve," Historical and Philosophical Society of

Ohio Bulletin, 17 (July, 1959), 154-66 and "The Western Reserve

and the Frontier

Thesis," Ohio Historical

Quarterly, 70 January, 1961, 45-57; David French, "Puritan

conservatism and the Frontier: The

Elizur Wright Family on the Connecticut Western

Reserve," The Old Northwest, 1

(March, 1975), 85-95.

3. Two general histories of the township

published as essays in histories of Geauga

county have the most detailed

information: History of Geauga and Lake Counties, Ohio

with illustrations and biographical

sketches of its pioneers and most prominent men

(Philadelphia, 1878), 167-74 (hereafter

cited as History of Geauga) and Pioneer and

General History of Geauga County with

sketches of some of the pioneer and prominent

men (Historical Society of Geauga County, 1880, facsimile

reprint Evansville, Indiana,

1973), 376-415 (hereafter cited as Pioneer

History). I have used a complete set of local

records located in the Geauga County

library branch in Chardon, Ohio. Maps used in

tracing the history of land ownership

were located in the County Recorder's Office in

Chardon. Most helpful were the guides

and collections of Jeanette Grosvenor, a life-long

resident of Claridon and a genealogist.

She had indexed the federal censuses, local

Congregational records, and had many of

the diaries.

Land and Community 103

communities or joined ones already

started they participated in the

gradual maturation of the entire region.

Some of these settlers came to

that northeastern portion of Ohio known

as the Western Reserve. The

area had been granted to the state of

Connecticut by the United States

government and was subsequently sold to

a group of investors called

the Connecticut Land Company in 1795.4

Surveying parties finished dividing up

the area and settlers began to

trickle onto the land before the turn of

the nineteenth century.

Apparently Claridon township, which

consisted of twenty-five square

miles, was attractive, for four groups

of investors purchased it and

hired surveyors to divide it into

smaller tracts. Perhaps investors were

impressed with the fertile dense clay

soil, common to the area, or the

abundant water resources supplied by the

two branches of the Cuyahoga

River which, separated by a ridge of

well-drained land, pass through

Claridon.5 In any case, the

first settlers arrived in 1810 followed by an

increasing stream of newcomers who

totalled 402 by 1820.6 Like most

Reserve townships founded during this

time, Claridon rapidly gained

population until 1840 when 900 people

lived within its boundaries.7

Also typical was the fluctuation of

population over the next three

decades, as the inhabitants rose by over

100 in 1850 and then dropped

back to 910 in 1870.8 Correspondingly,

the number of households grew

rapidly from 63 in 1820 to 172 in 1840.

A decade later it increased to 197

and then leveled off. Clearly Claridon's

population had made it part of

the settled rural hinterland.

Other demographic measures detail the same

gradual change. The

ratio of males to females favored males

in the initial stages of

settlement (there were 125 males per 100

females in 1820), as one would

expect. However, there were enough women

to suggest that, although

single adult males did migrate, young

families made up a large

proportion of Claridon's early settlers.

By 1850, just as the number of

people and households was leveling off,

virtually the same number of

4. See Harlan Hatcher, The Western

Reserve; The Story of New Connecticut in Ohio

(Indianapolis, 1948). See also Edmund

Chapman Cleveland: Village to Metropolis

(Cleveland, 1964), 1-8 (hereafter cited

as Chapman, Cleveland).

5. History of Geauga, 167-68: Pioneer History, 377-79.

6. The following analysis is based on

the federal census manuscripts for the years

1810 through 1870 located at the Western

Reserve Historical Society, Cleveland, Ohio.

7. Don R. Leet, "Population

Pressure and Human Fertility Response: Ohio,

1810-1860" (Ph.D. dissertation,

University of Pennsylvania, 1972), Table 2.3, 24-25

(hereafter cited as Leet,

"Population Pressure"); Robert A. Wheeler, "The Town in the

Western Reserve, 1800-1860," The

Western Reserve Magazine, 6 (May-June, 1979),

special insert (hereafter cited as

Wheeler, "The Town").

8. Leet, "Population

Pressure," 25; Wheeler, "The Town," passim.

104 OHIO

HISTORY

males and females lived in the township.

Two decades later there were

fewer males (93 per 100) than females, a

characteristic of older stable

areas.9

This gradual stabilization of population

was produced in part by a

change in the fertility of Claridon

women. As one would expect,

women in Claridon, like their

counterparts in the rest of early Ohio,

had high fertility in the first decade

of settlement. Most were of

childbearing age and they brought some

children with them and had

more soon after they arrived.10 In

the succeeding two decades their

fertility dropped dramatically-more

quickly than most observers have

found so that by 1840 it was 50 percent

lower.11 Not surprisingly, the

downward trend continued into the 1870s,

by which time it was a little

more than one-third of the 1820 rate. It

is likely that very early in the

history of the township, women, even

those newly-married, were

having fewer children. They were doing

so long before out-migration

and the declining proportion of males

forced declines in the fertility

ratio. The drop, as will be shown, was

caused by a decline in available

land, which local residents apparently

perceived as a loss of opportu-

nity.

Within this environment geographical

mobility and birthplace of

residents reflect the maturing local

society. While one might expect

9. The gradual shift of sex ratios from

male dominated to female dominated as an

area matures is generally accepted. For

one overview see Richard C. Easterlin, George

Alter, and Gretchen A. Condron,

"Farmers and Farm Families in Old and New Areas:

The Northern States in 1860" in

Tamara Hareven and Marus Vinouskas, eds., Family

and Population in Nineteenth-Century

America, (Princeton, 1978), 22-84

(hereafter cited

as Easterlin, "Farmers").

10. The fertility ratio is the number of

children from birth to 9 years old divided by the

number of women from the ages of 16 to

44. In the first decade of settlement it is 2260.

See Leet's discussion of the fertility

of Ohio women, particularly his comments on

Northeastern Ohio women in

"Population Pressure," 51; also Don R. Leet, "Human

Fertility and Agricultural Opportunities

in Ohio Counties: from frontier to maturity,

1810-1860" in David C. Klingaman

and Richard K. Vedder, eds., Essays in Nineteenth-

Century Economic History: The Old

Northwest, (Athens, Ohio, 1975), 145

(hereafter

cited as Leet, "Human

Fertility"). No similarly detailed study of fertility is intended

here, but the comparisons do suggest a

similar trend with some exceptions.

11. The figure is 1080. Leet argues that

those in the predominately New England

northeastern quadrant of Ohio had the

lowest fertility of any migrant group and

continued the trend after they became

Ohioans. Claridon fits this pattern, but Leet does

not account for this drop in fertility;

he simply notes it. See Leet, "Human Fertility,"

152-53. See also James Q. Graham, Jr.,

"Family and Fertility in Rural Ohio: Wood

County, Ohio in 1860," Journal

of Family History, 8 (Fall, 1983), 262-78 (hereafter cited

as Graham, "Family and

Fertility"). Graham uses more sophisticated techniques and a

different measure of fertility than

Leet, but for Claridon his technique, which requires

the detail of the census manuscripts

from 1850 onward, could not be used, and thus the

seemingly critical drop in the 1840s

would not be observed. Wood County in the western

portion of the state was settled much

later and would not have a similar problem.

Land and Community

105

migrants to remain in a newly-opened

area, especially if they were

household heads, the high rate of those

who stayed from decade to

decade over the entire time period is

nevertheless surprising.12 The

decennial persistence of household heads

was 54 percent for both 1830

and 1840. Even at mid-century the rate

dipped only slightly to 48

percent, and by 1870 it was still nearly

45 percent.13 In other words,

while some out-migration among young

adults and reduced fertility

among residents probably occurred, a

very high proportion of resident

household heads remained from decade to

decade, creating a stable

and potentially cohesive township.

Furthermore, more township residents,

particularly those who

stayed, were ethnically homogeneous

since Claridon, unlike the area's

cities, did not attract foreign

immigrants. In fact, Claridon's proportion

of foreign-born adults was generally

less than 5 percent.14 Predictably,

New Englanders predominated. In 1850,

when the federal census first

listed birthplace, the largest group of

migrants, 33 percent, came from

Connecticut. There were also large

contingents from Massachusetts,

10 percent, and the recently expanded

states of New York, 20 percent,

and Vermont, 9 percent. These migrations

came somewhat later than

the initial one from Connecticut.

Consequently, by 1870 only 16

percent of township adults were

Connecticut-born, whereas over

one-fourth, or 27 percent, of the adults

were born in the other three

states. By 1870 the first Ohio-born

generation had matured and

comprised half of all adults and nearly

two-thirds of those under fifty.

This gradual change gave Claridon a

decidedly native character.15

12. In the following discussion the

proportion of those who stayed is understated

because no accurate way of determining

which residents died during the period is

available and, therefore, all residents

who did not remain were judged to have left the

area. For a discussion of geographical

mobility among a very mobile population, see

Rebecca A. Shepherd, "Restless

Americans: The Geographic Mobility of Farm Labor-

ers in the Old Midwest, 1850-1870,"

Ohio History, 89 (Winter, 1980), 25-45. Her finding

that 21 percent of farm laborers stayed

each decade suggests that even this segment was

more stable, even though her analysis is

not specific to the Western Reserve. The

findings of Jack Blocker, who argued

that agricultural specialization can increase the

need for farm laborers while not

increasing the need for more farms, probably account

for these data. See his article,

"Market Integration, Urban Growth and Economic

Change in an Ohio County,

1850-1880," Ohio History, 90 (Autumn, 1981), 298-316.

13. Household members are not listed

separately on the federal census until 1850.

14. The key indicator of the shift from

immigrant to native is when the proportion of

adult residents become native. For this

reason only those over 21 years of age are

included. In the 1830s and 1840s most

native Ohioans were still children.

15. Much of the preceding discussion of

the evolution of Claridon fits into the patterns

discussed by Richard Easterlin, et al.,

for a much wider area in 1860. See Easterlin,

"Farmers," 22-84.

106 OHIO HISTORY

II. Economy

Part of the reason for the consistency

of most demographic indica-

tors was the economic evolution which

transformed Claridon and most

of the Reserve from an isolated frontier

area to a countryside dotted

with prosperous specialized dairy farms.16

Using Edward Muller's

construct, up to 1830 Claridon was part

of the "Pioneer Periphery,"

the first stage in an area's search for

economic viability, when its

residents established permanent

settlement, cleared land for agricul-

tural production, and searched for

exportable crops.17 Gradually,

during these two decades, residents

purchased tracts so that by 1820

they owned five thousand acres and ten

years later they owned the

entire fourteen-thousand acre township.

The average farmer owned

145 acres of land on which he grazed

five cows.18

After 1830 the area became part of the

"Specialized Periphery," a

second stage marked by demand for the

area's products on a regional

or even national level. During this

period settlement intensified and

interregional connections and

specialized staple production developed.

In Claridon, since all land was already

owned, this intensification

meant that the number of owners

increased by two-thirds, which

reduced the average holding to

eighty-eight acres by 1840, a drop of 40

percent. Significantly, this reduction

caused residents to respond to the

declining availability of land by

dramatically reducing their fertility by

one-third.19 The trend

continued to mid-century when another one-

fourth increase in owners further

reduced the average size of a farm to

seventy-three acres and caused fertility

to drop even further. These

16. For a general introduction see R.

Douglas Hurt, "Dairying in Nineteenth-century

Ohio," The Old Northwest, 5

(Winter, 1979-80), 387-99. See also Robert A. Wheeler,

"Agriculture in the Western

Reserve, 1800-1860," The Western Reserve Magazine, 5

(January-February, 1978), special

insert.

17. Edward K. Muller, "Selective

Urban Growth in the Middle Ohio Valley,

1800-1860," Geographical Review,

66 (April, 1976), 178-204.

18. In 1820, 100 percent of the farm

owners owned cattle and 95 percent did so in

1830. The two-thirds who owned any

horses owned one each in both years. County tax

records called Tax Duplicates were used

for land ownership, and personal property lists,

also part of the county taxation system,

were used to determine the number of animals

for the appropriate years. All are

located in the Geauga County Library, Chardon, Ohio.

19. The ratio fell from 1500 in 1830 to

1080 in 1840. There is extensive literature on the

relationship between available land and

the declining fertility of American women in the

nineteenth century. It basically argues

that, as resources measured in available land were

progressively more difficult to obtain,

family size dropped, especially in frontier areas.

This study of Claridon suggests that it

was not a generational phenomenon but happened

virtually as soon as the land pressure

first appeared to local residents. See Leet, "Human

Fertility," 145, 156-57, who

suggests that for the whole state the transitions came later

and Graham, "Family and

Fertility," 271-73, for a brief discussion of the literature.

|

Land and Community 107 |

|

|

|

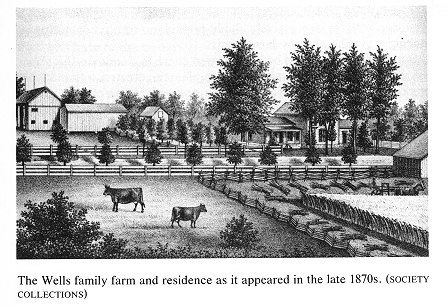

progressively smaller tracts accommodated a new specialized form of farming, dairying. By mid-century three-fifths of township real estate was meadowland while only 10 percent was plowland.20 Virtually all local farmers participated in dairying by increasing their herds four- fold-from five in 1830 to an average of twenty by 1860. The milk produced supplied several local cheese factories.21 The extent to which farm economy dominated Claridon is obvious from the occupations of residents. In 1850 fully 70 percent of those employed were farmers or farm laborers, and most of the remainder supported the rural economy as blacksmiths, wagonmakers, or carpen- ters. Twenty years later much the same situation existed except for the addition of several owners of cheese factories, an engineer, a machin-

20. The remainder was categorized as woodland. The 1853 and 1870 duplicates indicate the precise number of acres in each of the three categories. 21. Claridon farmers also joined the era of mechanized farming as they increased their commitment to farm machinery from sixty-three to two hundred thirty dollars over the decade ending in 1860. A further refinement in the local economy came when the dairy industry converted from cheese to butter production in the early 1870s. In 1850 and 1860 federal agricultural censuses were taken which detailed this local economy. Copies of the censuses are located at the Ohio Historical Society library in Columbus, Ohio. The federal population schedule shows one cheese factory in 1850 and several later. See also History ofGeauga, 170 and Pioneer History, 410. |

108 OHIO HISTORY

ist, and more shopkeepers.22 Thus

Claridon had evolved into a

township with an impressively stable

population firmly committed to

making a livelihood from dairy farms.

But even though Ohio-born dairymen came

to dominate the town-

ship, the associations which their

forefathers created left indelible

marks on the geography of the township

and on its sense of community.

As will be shown below, these

associations fixed local living patterns,

defined social networks, and

differentiated township neighborhoods.

III. Settlement Patterns: West-Center

vs. East

A careful inspection of land records

shows Claridon was settled in

two fairly distinct waves. These waves

produced a complex, divided

township in contrast to the surface

homogeneity suggested above.

Prior to 1820 most settlers took land in

the western third of the

township in the Holmes purchase along

the western branch of the

Cuyahoga river. As they spread they

followed the early surveys and

settled from north to south on what

would soon be called "west

street." More families followed,

probably encouraged by the positive

reports sent back home, especially to

Hartland and New Hartford,

Connecticut. At least five founding

families of the western portion of

the township-Taylors, Cowles, Spencers,

Kelloggs and Wells-came

from these two towns and had

representatives in Claridon before

1818.23 Many of them intermarried either

before they left Connecticut

or within several years after they

arrived. They so dominated Claridon

that when the first township officers

were chosen in 1817 seven of the

ten were from these families. Together

they comprised 20 percent of

the residents in 1820.24 Mary Taylor,

writing home to her sister in

Hartland in 1821, reported visiting

several Connecticut relatives in her

new home. She noted that even fashion

was transported to the Reserve

when she "saw as much silk and

crepe gowns as I would in Hartland"

at a church meeting in Burton several

miles from Claridon.25

During the early 1820s, settlers moved

into the second and third tier

of tracts along what was to become

"middle street" in the central

portion of Claridon. First they moved east

and south on a road which

22. See U.S. Census manuscripts for

Claridon in 1870.

23. Pioneer History, 378-89.

24. Chiles Blakeslee forword to the Record

Book of the Congregational Society,

Claridon Township, Geauga County dated

March 7, 1831, located in the church archives,

Claridon, Ohio (hereafter cited as Record

Book).

25. Mary Taylor to her sister, Claridon,

Ohio, June 28, 1821, in the Lester Taylor

folder, Geauga County Historical Society, Burton, Ohio.

Land and Community 109

led south to Burton. Then, in the

mid-1820s they bought land on the

north-south "center street"

which bisects the township. Rarely did

they purchase in the eastern tier.

These new immigrants began to create

local institutions. Mary

Taylor and her husband joined other

families in a Congregational

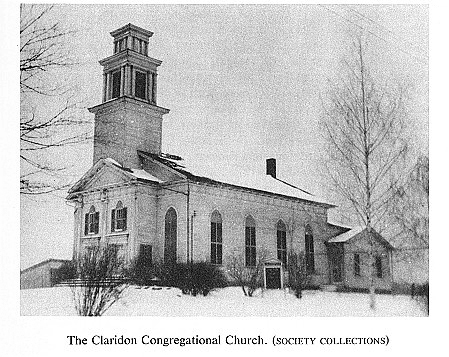

group. At first, members shared a

minister with nearby Burton. In 1827

they began the process of forming a

separate church when they created

the Claridon Congregational Society. Its

officers were selected over-

whelmingly from the founding families.26

Two years later a revival

swelled the number of society members.

In response, the group moved

its meetings from the houses along west

street to a larger building, a

schoolhouse built at the crossroads in

the center of the township.

Finally, in 1831 a church building was

constructed there.27

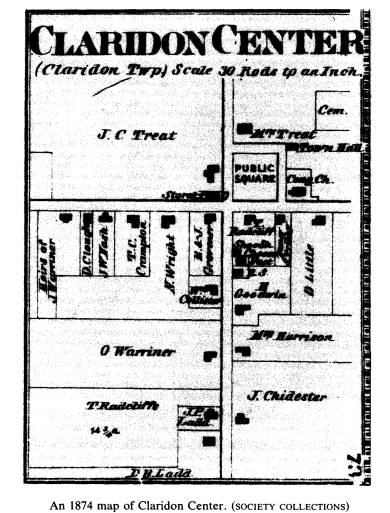

At the crossroads, on land donated by a

church member, a township

square took form modeled on New England

town squares of the late

colonial period.28 Slowly

other structures, including a meeting hall,

several shops, and another church, were

added. As early as the

mid-1830s, then, much of the township

was a developing community of

like inhabitants.

While that process was running its

course, another process was

beginning. From the mid-1820s onward

development moved away from

the center and western portions of the

township. A meager start was

made in 1816 when Lot Hathaway and

Holder Chace purchased land in

the eastern portion within the Erie

Company tract. Ten years later this

area began to prosper, in part because a

state road which ran from

Warren on the southeastern edge of the

Reserve north to Painesville on

the shores of Lake Erie cut through it

on a north-south axis.29

This eastern section was different from

the older portions of Claridon

in several important ways. Many of the

first settlers were not from

Hartland or New Hartford. Chace and

Hathaway, for example, were

from Freetown, Massachusetts, and

neither joined the Congregational

church.30 Nathaniel Mastick,

who arrived from Vermont, and other

26. Record Book, passim.

27. Pioneer History, 401-02.

28. D.W. Meinig, "Symbolic

Landscapes: Some Idealizations of American Commu-

nities" in D.W. Meinig, ed., The

Interpretation of Ordinary Landscapes: Geographical

Essays, (New York, 1979), 165-66 (hereafter cited as Meinig,

"Landscapes"). See also

Chapman, Cleveland, 1-35.

29. The road appears on land maps as

early as 1830 and on the first atlas of 1857. For

the land maps see those located in the

County Recorder's Office in Chardon. For the

atlas see Map of Geauga and Lake

Counties from Surveys and County Records

(Philadelphia, 1857).

30. C.V. Chace, Genealogical Record

of the Chace and Hathaway Families from

1630 to 1900 (Ashtabula, Ohio, 1900), 9, 29.

110 OHIO HISTORY

new settlers constituted a second

migration. Many arrived in the late

1820s and early 1830s, more often from

New York and Vermont rather

than Connecticut. Quite possibly many of

these newcomers felt left out

of local society which was already

partially formed. In any case, few

joined the Congregational church. Some

probably became members of

the Methodist society formed in the mid

1820s. Its ranks increased

sufficiently enough by the late 1830s

that it built a church across the

square from the Congregational church.

The new migrants, many of

whom were or became members of this

church, also began to inter-

marry within the confines of the eastern

third of Claridon.

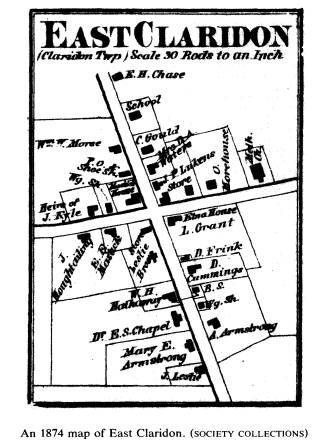

These emerging sections, or perhaps

neighborhoods, were further

differentiated in the 1840s and 1850s.

Beginning in 1840 a hamlet began

to develop in the eastern portion at the

intersection of the state road

and a smaller east-west road which

divided the township in half. Over

the next thirty years this concentration

of commercial and craft

enterprises became the hamlet of East

Claridon and gradually eclipsed

Claridon Center in terms of number of

stores and shops. It housed the

area's only hotel, first tavern, and

drygoods and hardware stores. East

Claridon differed significantly from the

square called Claridon Center.

Like most new nineteenth century towns,

it focused not on institutions

but on business and commerce.31 Its

people were different, too. A

study of the eighty-four inhabitants who

owned land in East Claridon

from 1840 to 1870 reveals that only

three were ever members of the

Congregational church.32 Claridon

Center, on the other hand, was

overwhelmingly peopled by

Congregationalists. Here is evidence of a

significant socio-geographical

differentiation in Claridon township.

Fortunately, it is possible to confirm

this separation in the late 1860s.

The Methodist church located in Claridon

Center since the late 1830s

decided to move. Not surprisingly, the

congregation and its building

moved to East Claridon in 1867.

Surviving sources attest to the virtual

bifurcation of Claridon which this

relocation confirmed. Of those who

owned land in the eastern third of the

township, fully three-quarters

were from the church. Moreover, no

Methodist lived in the middle or

western portion of the township.33 The

hamlet of East Claridon

likewise was virtually all Methodist.

31. See Schlereth, "New England

Presence," 134; Meinig, "Landscapes," 168-69.

32. Twenty tax duplicates were used to

trace land ownership patterns. Fortunately,

the original surveyor's lot designations

were kept throughout much of the period and

could be combined with maps of land

ownership which were redrawn for the conve-

nience of the county recorder at

approximately ten-year intervals. All located in Geauga

County Recorder's Office, Chardon, Ohio.

33. The original lists were graciously

lent to me by Mrs. Michael Pitorak, a member

of the Methodist Church of East

Claridon, Ohio. The lists were compared with maps, tax

|

Land and Community 111 |

|

|

|

It is no wonder then that, after thirty years of making the trip from their apparently homogeneous Methodist neighborhood to the town- ship center, the Methodists decided to break the superficial cohesive- ness of the town square. They literally brought their church and their community together. The church could have stayed in the town square, but church attendance was tied to neighborhood cohesiveness and a compatible social network. It was moved to join an existing community in East Claridon. Further confirmation of this separation comes from a Congregational church list of early 1867 which identified streets in the township for specific church leaders to canvas during a week of prayer. West, middle, and center streets, all north-south roads, had four persons each, and there were two for the east-west road; but no one was selected from the eastern third of the township along the state road in Methodist territory.34

duplicates, and lists of Congregational church members. 34. Records of the Congregational Church of Claridon, Ohio, 1866-1875, January 6, 1867 (hereafter cited as Records of the Congregational Church), located in the church archives, Claridon, Ohio. |

112 OHIO HISTORY

Furthermore, the nativity of Methodists

confirms a distinction

already suggested. They were newer

migrants (one-third were born in

New York) and were less likely to be

native Ohioans (29 percent) than

the township in general (49 percent).

Unlike Congregational church

members, 95 percent of whom were born

either in Ohio or Connecticut,

only 45 percent of Methodists were born

in either state.35 A compari-

son of occupations of the two groups

shows that fully half of the

Methodists were not employed as farmers

but made up much of the

skilled and service work force in the

area. Congregationalists, on the

other hand, were three-quarters farmers.

While still part of the rural

economy, many Methodists worked in East

Claridon where they were

more easily linked to the local and

regional business network. This

orientation continued when in the early

1870s a railroad was built along

the eastern side of the state road close

to East Claridon and the

Methodist church.36

Although Methodists were committed to

business, they were not as

wealthy as the Congregationalists. An

1853 tax assessment valued the

Methodist church building at $675, while

the Congregational building

was listed at $1200.37 The

disparity is also reflected in personal assets.

Methodists averaged $5,400 of personal

and real property in 1870 while

Congregationalists averaged over one

thousand dollars more.

Therefore, according to these records,

below the level of the

township a set of distinctions served to

differentiate Claridon. The

township contained two sections settled

at different times by people of

different religious commitments who had

different levels of wealth. In

fact, the distinctions were in some ways

the equivalent of a wall which

separated neighborhoods and perhaps even

communities. This thesis is

further supported by an impressionistic

study of the 325 marriages

recorded for the township from 1825-1869

which indicates that few

local couples included partners from

both sections.38

It would be a mistake to think that

these patterns created insur-

mountable obstacles to communication

and to all forms of institutional

interaction. Township officers by the

1830s included at least one or two

members from East Claridon, and the

sharing of political offices

35. A complete list of members compiled

in 1871 was used. See Records of the

Congregational Church.

36. Pioneer History, 410-15, and

town record books located in the Township Hall,

Claridon, Ohio.

37. See Tax Duplicate for 1853, Geauga

County Public Library, Chardon, Ohio.

38. A list of marriage license

applications from Claridon was used. The applications

are located in the Probate Court Records

in a separate volume at the Geauga County

Court, Chardon, Ohio.

Land and Community 113

continued into the 1870s.

Several farmers' clubs attracted members

from both areas as well. But other

social organizations formed in

Claridon reflected the differences. For

instance, there were separate

temperance organizations, and a chapter

of the Independent Order of

Odd Fellows formed in 1850 was

exclusively an East Claridon group.39

Consequently, while the two groups did

cooperate in some institutions,

the separation seems to be an important

dynamic in Claridon.

IV. Social Contact and Neighborhood

Context

The preceding analysis of geographical

and institutional separation is

somewhat limited because the records

which preserve these associa-

tions often list only membership,

ownership, or tax status and do not

reveal the daily activities of

residents. Fortunately, four detailed

personal diaries survive for Claridon

which help disclose the nature

and extent of local social networks and

reveal the degree of contact

which occurred within and between the

sections of Claridon.40 Also

fortunately, the diarists who are in

their 20s and 30s are socially active.

One, Clinton Goodwin, was a young

married farmer, and the other

three-Elnora Spencer, Lectrus Newell,

and Mary Taylor-were young

unmarried adults in their early

twenties. Their diaries help determine

the nature of Claridon society and

whether the differences noted above

merely happened on Sunday at church, at

meetings of some voluntary

organizations, or were an important part

of community social networks

as the previous discussion implies.

The diaries do have several limitations.

First, they are concentrated

in the period from 1855 to 1867 when

the community was well formed

and had reached its geographical and

population limits. Second,

unfortunately, all of the diarists live

in the central and western portions

of Claridon and were either members of

the Congregational church or

attended services there. Therefore, only

this viewpoint is available to

describe and analyze the social,

economic, and spatial context of

Claridon.

The diarists had very busy social lives.

Regardless of the time of

year, an extensive system of interaction

is evident. Nearly everyday

39. Pioneer History, 411-13; History

ofGeauga, 170-72. From 1839 until at least 1860

there was a Mother's Club in Claridon

which was made up of Congregationalists

exclusively. In the 1840s the club

included eighteen mothers and fifty-two children,

mostly from the Center area. See

hand-written history citing the original record book,

Claridon folder, Geauga County

Historical Society, Burton, Ohio.

40. Jeanette Grosvenor had copies of all

of these in her collections. I wish to thank

Mrs. Virginia Hyde and Mrs. Elnora Zepp

for allowing me to use these documents.

114 OHIO HISTORY

someone visited them or they visited

others. Typically, every other day

they left their farms. Seldom did they

visit East Claridon or "call" on

Methodists. Approximately one-fifth of

their trips took them beyond

the township.41 Chardon, the county seat

located several miles to the

northwest, attracted them because of its

official role as keeper of

county records, its political meetings,

and its businesses which were

more extensive than local ones.

Occasionally a special event attracted

their attention, such as the trial

Elnora Spencer and her friend and

neighbor, Maria Allen, attended in

Chardon on March 9, 1858. Spencer

noted, "we got a good seat in front

of the jury & heard Mr. Riddles plea

against Mr. Cole he sat most of the time

with his handkerchief over his

eyes."42

Relatives, friends, businesses, and

church activities drew them to

the neighboring townships of Huntsburg,

Hamden, Burton, Middlefield,

and Munson. Four young members of the

Taylor family journeyed to a

Musical Association probably attended by

Congregationalists in

Huntsburg on October 28, 1856.43

Mary Taylor, who was twenty-five,

acknowledged her difficulty fitting into

the social context because of

her age. She noted that some "young

people had gone to Burton this

eve. I do not feel so lonely & sad

... nevertheless it is not very pleasant

to think ones self has grown out of

society and is to be left alone Alas

I am so."44 Age was

only one reason for her feelings. Another was the

mobility of her contemporaries. While

she had remained in Claridon

with her parents, she found few

"out of the family that I care to visit

with. My School Mates are all

West."45

Elnora Spencer was much more positive

and active. She recorded a

trip to a nearby natural attraction,

Nelson's Ledge, with a group of ten

friends. Most of them were from center

street and four were Taylors,

but Emily Ensign, probably a school

friend, was part of the group. She

was unusual since she lived in East

Claridon. Of the individuals

mentioned and identifiable in these

ventures outside Claridon, fewer

than 5 percent were East Claridonites.46

41. An analysis of each diary indicates

that Clinton Goodwin took 21 percent of his

trips out of the township. The

percentages for the other diarists were Lectrus Newell 15

percent, Elnora Spencer 15 percent, and

Mary Taylor 10 percent.

42. Elnora Spencer, Diary, March

9, 1858.

43. No entry in any diary which mentions

those present at the various extra-township

activities lists Methodists. It could be

that they were simply not in the sphere of friends

of the diarists, but this seems

unlikely.

44. Mary Taylor, Diary, December

12, 1855.

45. Mary Taylor, Diary, October

2, 1856.

46. Elnora Spencer, Diary, August

25, 1858.

|

Land and Community 115 |

|

|

|

About 80 percent of the time the diarists moved within Claridon, "the land of steady habits," as Lec Newell described it when he returned home from a trip to Rochester, New York.47 Here they participated in vital but limited spheres of activities. Newell lamented his lack of companionship one rare evening by noting "no one been here ... Oh, how lonesome. Neither have I been away to enjoy what I often do."48 Typically, he saw friends daily but rarely those from East Claridon. Several social conventions resulted in visits to and from family and friends. Teas, a regular activity in these households, created a social atmosphere for local residents and for people passing through. Some-

47. Lectrus Newell, Diary, October 20, 1856. 48. Lectrus Newell, Diary, January 24, 1858. |

116 OHIO HISTORY

times young people visited each other in

groups, as Lec Newell did

with four friends in January, 1858.49 A

month later Elnora Spencer

recorded an exceptionally large

gathering in the afternoon at which her

family entertained "a party of

relatives twenty-four to tea."50 Of the

several hundred teas listed in the

diaries, only two included Method-

ists. Dinner or overnight guests also

appeared at least once a week. A

busy but typical round of visits to the

Spencers on June 21, 1861,

included a dinner stopover by six

couples who lived either along center

street or on west street in the southern

portion. Another diarist,

Clinton Goodwin, said he "took

supper at [Laroyal Taylor's] with the

rest of the Taylor family" on

December 25, 1867.51 Typically, family

and close friends made up the bulk of

these exchanges.

Parents and children often had different

activities on the same

evening, such as when Newell's parents

went to "Deacon Treat's to

party while I was at N. Treat's spending

the PM in singing and chatting

etc."52 The nature of

local neighborhoods is suggested by Elnora's

comments that her brother went "to

the meeting at the center. Parents

gone up street" on the evening of

March 26, 1858.53

The social life of adults in Claridon

can be suggested by Clinton

Goodwin's activities during the third

week of October, 1867. All week

he spent his days harvesting corn and

potatoes, but his evenings were

filled with relatives and neighbors. On

Sunday his young brother-in-law

came to visit him after much of the day

was spent at church. On

Wednesday he went to his father-in-law's

to eat peaches, and the next

day his father and mother visited him at

his farm. Friday "Mrs. Andrus

and 4 neighbors [were] visiting,"

and on Saturday a friend of his who

lived near the Center came to his farm.54

Apparently, adults often went

visiting in groups. Goodwin went with

his uncles and their wives to

visit on "street south of

Wells" where they stopped at two places.55

There is no indication that any of

Goodwin's rounds ever included East

Claridon residents.

Elnora and Lectrus did, on occasion,

interact socially with East

Claridon people, however. On July 13,

1861, Elnora Spencer went to

the Claridon Center with her father, but

later she continued east on the

49. Lectrus Newell, Diary, January

21, 1858.

50. Elnora Spencer, Diary, February

22, 1858.

51. Elnora Spencer, Diary, June

21, 1861; Clinton Goodwin, Diary, December 25,

1867.

52. Lectrus Newell, Diary, January

29, 1858.

53. Elnora Spencer, Diary, March

26, 1858.

54. Clinton Goodwin, Diary, October 14-October 20, 1867.

55. Clinton Goodwin, Diary, January

10, 1867.

|

Land and Community 117 |

|

|

|

center road to East Claridon where she uncharacteristically "called" on two Methodist families, the Lukens and the Armstrongs. We can only speculate on the reason for these visits because while they are unusual they are not explained.56 Further indications of a more complicated social picture were the visits that Lec Newell made to his uncle, a Methodist resident of East

56. Elnora Spencer, Diary, July 13, 1861. |

118 OHIO HISTORY

Claridon. Probably because of this

family connection, he attended a

gathering at Wilmot's (a

Congregationalist) on center street on March

7, 1858, with J.C. Hathaway (a

Methodist).57 Apparently, these

"mixed" social gatherings

happened occasionally in Claridon, but the

other diarists do not record similar

gatherings, and Newell moved

between the groups more easily than

others because of his family

connections with both Methodists and Congregationalists.

All diarists were consistently drawn to

Claridon Center but rarely to

East Claridon. At the Center the

Congregational church and, in the

mid-1850s, an agricultural hall were

sites for Sunday services and for

numerous meetings and "select"

schools. Clinton Goodwin, who was

a deacon during 1867 and 1868, missed

only four Sunday services

during the two years. His younger

counterparts were nearly as diligent,

although they were occasionally

dissuaded by the weather or sickness.

Mary Taylor attended three times a month

during 1855 and 1856, for

instance. She also went to the hall at

the Center to donation parties for

the minister and to a musical concert.

Lectrus and Elnora attended

singing school, which often attracted

Congregationalists from sur-

rounding townships. Perhaps Methodists

also attended, but none are

specifically mentioned.

Elnora recorded another social and

religious separation in her diary.

She noted on May 19, 1858, that she

heard the bell in the Congrega-

tional church toll because two people

died.58 She attended the funeral

of the deceased Congregationalist but

not of the Methodist, a Hathaway

from East Claridon.

Socially, then, the diarists tended to

stay among family, friends and

neighbors within Claridon. Economically,

they were attracted to East

Claridon for its mills, stores, and

meeting rooms. Goodwin "went to E

Claridon and got flour etc for which I

owe Mastick 4 and Lukens 2" on

July 12, 1867. A year later he went for

a hog.59 While he rarely visited

in East Claridon, he did trade there. On

the other hand, he went to

Chardon to take hides for tanning and he

also went farther afield for

more specialized items such as a carpet

or a stove which he found in

Painesville.60 Lec Newell

went to East Claridon fairly often because

his uncle, T.W. Ensign, was a hotel

keeper there. In fact, J.P. Luken,

a Methodist store owner in East

Claridon, asked him to "live in the

57. Lectrus Newell, Diary, March

7, 1858.

58. Elnora Spencer, Diary, May

19, 1858.

59. Clinton Goodwin, Diary, June

22, 1868, July 12, 1868, November 23, 1868.

60. Clinton Goodwin, Diary, December

17, 1867, November 1, 1867.

Land and Community 119

store for a year or two." Lec

recorded, he "did not give him a definite

reply."61 Presumably,

this job offer shows that the lines between the

two segments of the township were not

impenetrable.

Claridon Center also attracted visits

for business and craft. Both

Goodwin and Newell went to the center to

have wooden items

repaired.62 The blacksmiths,

milliners, and the social function of the

post office undoubtedly provided time

for economic and social trans-

fers. Diarists who often say that they

"went to the center" probably

mean they went to pick up mail,

"trade," and socialize. They never

report they "went to East

Claridon."

The reasons for this are clear. With few

exceptions the diarists

remained among family, intimate

neighbors, and friends within the

north-south streets of Claridon. They

often stayed within their neigh-

borhood. Plotting the distance traveled

by the diarists suggests that

most of the time they were in Claridon

they stayed within two miles of

their farms. Clinton Goodwin was

typical. Goodwin lived north of the

Center on "center street," and

was within two miles of both the Center

and East Claridon. He traveled north and

south on the center road

almost exclusively when visiting or

doing business within the town-

ship, and he sometimes worked for or

with neighbors or with his family

who lived within one mile of his farm.

When he ventured beyond these

bounds, it was generally to visit

family, specifically his father-in-law.

He went weekly to the center to the

Congregational church and

biweekly for business. In contrast, he

went to East Claridon rarely, and

then to the stores or meeting rooms

there rather than to visit.63

Goodwin, then, rarely interacted with

Methodists or with anyone along

the state road. He stayed within his

neighborhood and within his

religious group almost exclusively. On

February 12, 1868, he acknowl-

edged that he was going to another

neighborhood when he recorded he

had attended a "meeting on Spencer

Street for Young folks." "Spencer

Street" was a Congregationalist

neighborhood along the west road

where many members of the Spencer

family, including Elnora's family,

lived.64

The spatial relationships of the younger

diarists confirm these

definitions. Elnora Spencer limited most

of her contact to her street,

61. Lectrus Newell, Diary, January

25, 1858.

62. See Clinton Goodwin, Diary, February

11, 1868, and March 3, 1868.

63. Clinton Goodwin, Diary, July

12, 1868, and November 23, 1868.

64. The preceding analysis is the result

of mapping all the known individuals and

locations given in the diary, which was

possible for approximately 80 percent of the

entries. Similar procedures were

followed to determine the spatial relationships of each

of the other diarists.

120 OHIO HISTORY

the Center and the road extending north

of it. While she did venture

south in the western portion and

occasionally a little east, her contacts

within the township were limited. She

often left her house in the

company of her suitor, Lec Newell, who

lived north of Claridon

Center. She had very little contact with

East Claridon even though she

appeared to know residents there. Lec

Newell lived on his father's

farm which was just north of Claridon

Center and, like Goodwin, had

most of his contacts on the center road.

Newell rarely ventured west

unless it was to Elnora's. He often

worked with neighbors and relatives

who lived on adjacent farms. He did visit

his relatives in East Claridon,

but most of his social life revolved

around singing activities and a series

of parties held for his Congregational

peers.65 The third young adult,

Mary Taylor, had very limited spatial

and social contacts. She lived on

Middle street just west of the Center

where most of her spatial and

social interaction took place. While she

constantly noted that her

parents and siblings visited others, she

was reclusive; although she

enjoyed visits by others, she rarely

went out herself. During 1856 she

made only fifteen visits, many of which

were to family or events

connected with church.66 Typical

of all diarists, she mentioned only

two interactions with East Claridon

residents and did not go to the

hamlet itself.

Therefore, socially, economically, and

spatially the four diaries

demonstrate that the division within

Claridon township was a vital part

of daily life. They also reveal several

overlapping spheres of interac-

tion. The first and smallest sphere

includes the farm, intimate family,

and neighborhood which take up much of

the daily activities. Second,

a larger sphere used less often was

defined by church-related activities

and more extensive family contacts which

drew residents farther from

their farms and sometimes into contact

with those beyond the town-

ship. An even larger sphere of economic,

political and social ties

occasionally involved them with

residents from other groups, including

Methodists. One can safely speculate

that diaries written by Method-

ists in East Claridon would include

these same spheres and include few

contacts with Congregationalists.

V. Conclusion

This analysis of Claridon township has

shown that the nature and

parameters of social change as measured

by social statistics do not

65. Lectrus Newell, Diary, January

29, 1858, February 26, 1858.

66. She provided the summary information

in the diary. See Mary Taylor, Diary,

December 30, 1856.

Land and Community 121

always suggest the complexity of social

life itself. Despite data which

indicate that a homogeneous, stable

community had emerged in

Claridon by the mid-nineteenth century,

migratory patterns created

differences in settlement areas and

social contacts which in some real

ways divided the township physically

and socially. As early as 1840

two groups appeared, and later

developments mirrored in the physical

evolution of Claridon Center and East

Claridon kept them separate in

some ways. By the 1850s and 1860s,

spatial and social interaction

continued to preserve the distinction

and even perpetuate it within the

limited spheres of Claridon social life.

The evolution of social contacts and

social life on the Trans-

Appalachian frontier suggests that the

Yankee heritage, while still

firmly rooted in Protestant

Christianity, created separate social and

religious contexts which in part

determined the social life of commu-

nities as they matured.