Ohio History Journal

THE CHARCOAL IRON INDUSTRY OF THE

HANGING ROCK IRON DISTRICT--ITS IN-

FLUENCE ON THE EARLY DEVELOP-

MENT OF THE OHIO VALLEY

BY WILBUR STOUT

INTRODUCTION

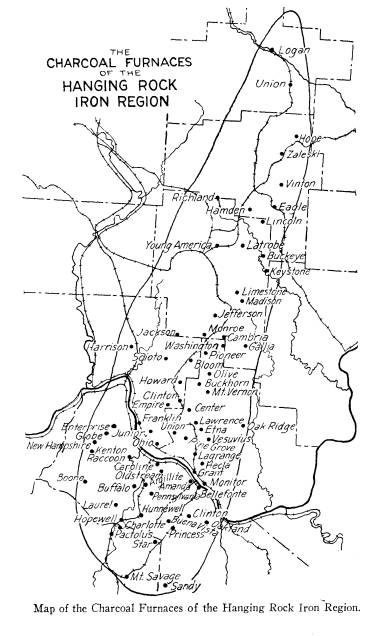

The Hanging Rock Iron District, as

defined by the

iron masters, embraced the furnaces and

furnace lands

and also the adjacent properties over

which iron ores,

limestones, and charcoal were gathered.

It included

parts of Carter, Boyd and Greenup

Counties, Kentucky,

and parts of Lawrence, Scioto, Gallia,

Jackson, Vinton

and Hocking Counties, Ohio.

The district has an elliptical shape, a

length of more

than 100 miles, a maximum width of 28

miles, and a

trend of 18 degrees east of north,

which is close to that

of the strike of the rock strata. The

area grew by ex-

pansion along the outcrop of the ore

beds as the lines of

transportation were pushed farther and

farther out

from the original means, the Ohio

River. Within this

field all the raw materials necessary

for the smelting of

charcoal iron were provided by nature

in abundant

quantity.

The area south of the Ohio River was

roughly 510

square miles and that north of this

stream 1,290 square

miles. The district, in 1875, included

69 charcoal

furnaces and 16 coal or coke furnaces,

the latter repre-

(72)

|

Influence on Early Development of Ohio Valley 73 |

|

|

74 Ohio

Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

senting a progressive step in the iron industry. Iron

smelting in the area was inaugurated by the building

of

Argillite furnace on the Kentucky side of the river

and

by that of Union on the Ohio side. The former was

erected in Greenup County, in 1818, by Richard Deering

and Trimble Brothers and had a capacity of one ton per

day. North of the Ohio River in the Hanging Rock

District, the pioneer furnace was Union, built a few

miles north of Hanging Rock in 1826 by James Rodgers

and Company. These furnaces were successful, supply-

ing a needed want for iron in the Ohio Valley. Their

prosperity led to the building of others until after

the

Civil War.

On the Ohio side the last charcoal furnace to be

placed in blast was Grant which was located on the

river

bank at Ironton and which began operations in 1869.

South of the river such construction was brought to a

close when Iron Hills or Charlotte furnace was erected

in 1873 at Riverton, Kentucky.

Distribution, Names, Locations, Etc.

The distribution of these furnaces was as follows:

State

County Furnaces Furnaces

Kentucky Charcoal

Coal or Coke

Greenup ............. 16

Boyd ................ 4

Carter ............... 4 2

Total .............. 24 2

Ohio

Lawrence ............

16 4

Scioto ............... 9

Gallia ............... 1

Jackson ..............

11 10

Vinton .............. 6

Influence on Early Development of Ohio Valley 75

State

County Furnaces Furnaces

Ohio Charcoal Coal or Coke

Hocking

............. 2

Total.............. 45 14

Total.............. 69 16

The names, locations, dates of erection, capacities,

and names of builders of the furnaces in the Hanging

Rock District to 1876 are listed below:

Charcoal Furnaces

Name When

Daily

of

County State Built Ca- Builders

Furnace pacity in

tons

Amanda

Boyd Ky. 1829

5 Lindsey Poague

and others

Argillite

Greenup Ky. 1818

1 Richard Deering &

Trimble Bros.

Bellefonte

Greenup Ky. 1826

14 A. Paull, Geo.

Poague & others

Bloom

Scioto Ohio 1832 15 John

Benner and

others

Boone

Carter Ky. 1856

12

Sebastian Eifort

and others

Buckeye

Jackson Ohio 1851

12 C. Newkirk and

others

Buckhorn

Lawrence Ohio 1833 15

James and Findley

Buena Vista Boyd Ky. 1848 15

Wm. Foster and

others

Buffalo

Greenup Ky. 1851

15 L. Hollister, Ross

and Co.

Cambria Jackson Ohio 1854 12 D. Lewis and Co.

Caroline Greenup Ky. 1833 3 Henry

Blake & Co.

Center Lawrence Ohio 1836 16 Wm.

Carpenter

and others

Cincinnati

Vinton Ohio 1853

13 McClanberg and

others

Clinton Boyd Ky. 1830 2 Poague Brothers

Clinton Scioto Ohio 1832 11 McCullum

& others

Eagle Vinton Ohio 1852 15 A. Bentley

& others

76 Ohio

Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

Charcoal Furnaces

Name When Daily

of

County State Built Ca- Builders

Furnace pacity in

tons

Empire Scioto Ohio 1846 7 Glidden

Brothers

Enterprise Greenup Ky. 1832 3 Clingman

& others

Etna Lawrence Ohio 1832 16 James

Rodgers and

others

Franklin

Scioto Ohio 1827

7 Daniel Young and

others

Gallia

Gallia Ohio 1847

15 John Campbell and

others

Globe

Greenup Ky. 1833

3 George Darlington

and others

Grant

Lawrence Ohio 1869

16 W. D. Kelley and

Sons

Hamden

Vinton Ohio 1854

16 L. C. Damarin and

others

Harrison

Scioto Ohio 1853

12

Eifort, Spellman

and Co.

Hecla Lawrence Ohio 1833 10 Hamilton

& McCoy

Hope Vinton Ohio 1854 14 Col. Putnam and

others

Hopewell Greenup Ky. 1832

Howard Scioto Ohio 1853 15 John Campbell and

others

Hunnewell

Greenup Ky. 1844

16 Campbell, Peters,

Culbertson Co.

Iron Hills

Carter Ky. 1873

Iron Hills Furnace

& Mining Co.

Jackson

Jackson Ohio 1838

12 Hurd, Young and

others

Jefferson

Jackson Ohio 1854

14 Jefferson Furnace

Co.

Junior

Scioto Ohio 1832

7 Young Brothers

and others

Kenton

Greenup Ky. 1856

13 John Warring and

others

Lagrange Lawrence Ohio 1836 7 Hurd,

Gould & Co.

Latrobe Jackson Ohio 1854 12 McGhee, Austin

and others

Laurel Greenup Ky. 1848 12 Wurts Brothers

Lawrence Lawrence Ohio 1834 15 J. Riggs and Co.

Influence on Early Development of Ohio Valley 77

Charcoal Furnaces

Name When Daily

of

County State Built Ca- Builders

Furnace pacity in

tons

Limestone

Jackson Ohio 1855

12 Evans, Walter-

house & others

Lincoln Jackson Ohio 1853 12 S.

Baird and others

Logan Hocking Ohio 1853 15 Dumm Brothers

Madison Jackson Ohio 1854 14 Campbell, Terry

and others

Monitor

Lawrence Ohio 1868

13 John Peters and

others

Monroe

Jackson Ohio 1856

20

Campbell, Bolles

and others

Mt. Savage Carter Ky. 1848 14 Biggs and others

Mt. Vernon Lawrence Ohio 1833 16 Hamilton, Camp-

bell and Ellison

New Hamp-

shire

Greenup Ky. 1848

15 Seaton and Boyd

Brothers

Oak Ridge

Lawrence Ohio 1856

15 Mather and

Mitchell

Oakland Boyd Ky. 1834 7 Kouns Brothers

Ohio Scioto Ohio 1845 15 Sinton and Means

Olive Lawrence Ohio 1846 16 Campbell

and

Peters

Pactolus

Greenup Ky. 1824 3 McMurty & Ward

Pennsylvania Greenup Ky. 1848 12 Wurts

Brothers

Pine Grove Lawrence Ohio 1828 16 Hamilton

& Ellison

Pioneer Scioto Ohio 1856 12 Colvin, Tracy and

others

Raccoon

Greenup Ky. 1833

12 Trimble, Woodrow

and others

Sandy

Greenup Ky. 1847

Young, Gilruth

and others

Scioto Scioto Ohio 1828 12 Salters and others

Star Boyd Ky. 1847 McCullough

and

Lampton

Steam Greenup Ky. 1824 1 Shreeves Brothers

Union Lawrence Ohio 1826 1

James Rodgers

and Co.

Union

Hocking Ohio 1854

14 McManigal Bros.

78 Ohio

Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

Charcoal Furnaces

Name When Daily

of

County State Built Ca- Builders

Furnace pacity in

tons

Vesuvius

Lawrence Ohio 1833

10 Hurd, Gould and

others

Vinton Vinton Ohio

1853 20 Clarke, Culbertson

and others

Washington Lawrence Ohio 1853

17 Campbell, Peters

and others

Young

America

Jackson Ohio 1856

12

Powell, Oakes and

Co.

Zaleski

Vinton Ohio 1858

15 Zaleski Furnace

Co.

Coal or Coke Furnaces

Alice Lawrence Ohio 1875

60 Etna Iron Works

Ashland Boyd Ky. 1869 40 Lexington and Big

Sandy R. R. Co.

Belfont

Lawrence Ohio 1867 45

Belfont Iron

Works

Blanche Lawrence Ohio 1875

60 Etna Iron Works

Fulton Jackson Ohio 1865 12 Lewis Davis and

others

Globe Jackson Ohio 1872 20 Watts, Hoop & Co.

Huron Jackson Ohio 1874 12 Huron Iron Co.

Ironton Lawrence Ohio 1875

40 Iron and Steel Co.

Milton Jackson Ohio 1873 20 Milton Furnace

and Coal Co.

Norton

Boyd Ky. 1873 45

Norton Iron

Works

Ophir Jackson Ohio 1874 12 Bundy and others

Orange Jackson Ohio 1864 16 Watson and others

Star Jackson Ohio 1866 17 Brown and others

Tropic Jackson Ohio 1873 17 Tropic

Furnace

Co.

Wellston

Twins

Jackson Ohio 1875

15 Wellston Coal and

Iron Co.

PERIODS OF FURNACE BUILDING

Furnace building went somewhat by

spurts. The

first active period was for the three

years, 1832-1834,

when 15 stacks were placed in

operation. This was fol-

lowed by eleven years, 1835-1845, of

quietness, only five

firms entering the field. Industrial

activity again was

sufficient during 1846-1848 to cause

ten furnaces to be

erected, mainly in Kentucky. Owing to

the projection

of railroads into undeveloped areas in

Ohio, the most

energetic period of furnace building was

the four years,

1853-1856, when 21 stacks were

added. The total

reached in 1856 in the Hanging Rock

Iron District

was 65.

OUTSTANDING FEATURES

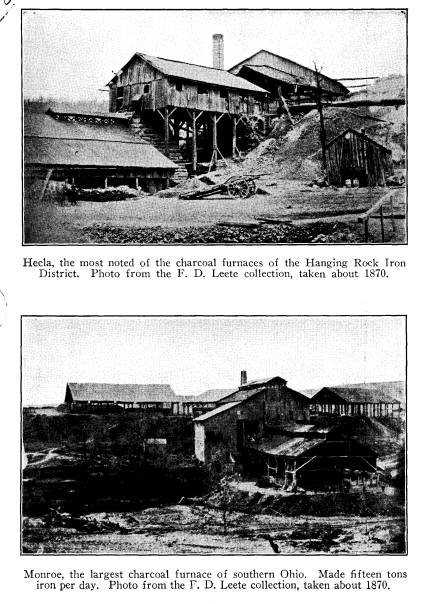

The outstanding furnace of the charcoal

group was

Hecla. Its fame, however, was due not

so much to the

superiority of the furnace as to its

great iron master,

John Campbell. Vesuvius furnace gained

prominence

among the iron-workers, because there

in 1836 was in-

troduced the use of hot blast instead

of cold air for the

smelting operation. Under the management

of Robert

Hamilton, in 1844, Pine Grove was the

first furnace to

suspend operations on Sunday. The

results were so

satisfactory that other furnaces

followed the practice.

Monroe, through its size and rich

limestone ore, was

noted for its capacity, making as much

as 20 tons per

day. Keystone, due to its location, to

the general clean-

liness of the ground, and to its

schools, churches, and

(79)

|

80 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications |

|

|

Influence on Early Development of

Ohio Valley 81

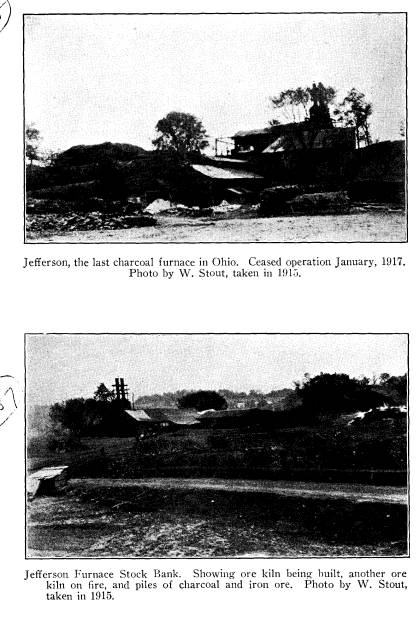

residences, was the model furnace of

the district. Jef-

ferson is outstanding not only for a

long and successful

campaign, but because it was the last

charcoal furnace

in Ohio to yield to the competition of

the coke furnaces.

It was placed in blast in 1854 and

suspended operations

in January, 1917. In fact, most of

these old charcoal

furnaces were interesting for some

phase, quality or

originality such as ore supply, furnace

location or equip-

ment, operating conditions, personnel

of management or

labor, social life, marketing

conditions, quality of

iron, etc.

DEVELOPMENT OF AREA

The charcoal furnaces caused a rapid,

early develop-

ment of the region which as previously

stated occupied

an area of approximately 1,800 square

miles. The en-

tire 69 charcoal stacks were built in a

span of 56 years,

1818-1873, inclusively. The addition

was thus over one

furnace per year. During the main period

of furnace

building, 1832-1856, this rate was more

than doubled,

for 55 furnaces were erected in 25

years. On account

of such development, both capital and

labor were at-

tracted to the area. Many of the

managers, foundry-

men, and colliers came from the iron

districts of Penn-

sylvania, Virginia, or New Jersey and a

few from even

England or Germany. This was also true

of the trades-

men. Through these men and their

influence much out-

side capital was brought into the

district and, what was

of most importance, it was put to work

either in the

iron industry directly, or in trade,

transportation, or

agriculture. The labor, in like manner,

was gathered

from a wide field. Many of the furnace

hands had

migrated westward with the industry

from the iron

Vol. XLII--6

82

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

regions east of the Appalachian

Mountains. Small num-

bers of raw immigrants especially those

of Irish, Welsh,

Scotch, English and German descent were

attracted to

the area on account of the labor

opportunities. They

found work mainly in the ore mines and

around the

charcoal pits. The wood choppers, as

would be expected,

were gathered largely from adjacent

areas of the

forested Alleghany Plateau. They were

at home in the

woods and were skilled axmen. The

teamsters were

recruited mainly from either the farms

or the sawmills

of the adjacent areas. Colored labor

did not appear at

the furnaces until after the Civil War

and then only in

small numbers and at only a few places.

DISTRIBUTION OF PEOPLE

Through the influence of the furnaces

the people

were well distributed over the entire

area instead of be-

ing concentrated at a few places.

However, through

better shipping facilities, more

furnaces were erected

within reach of the Ohio River than

were built farther

inland. In general, the furnaces were

rather uniformly

spaced from three to five miles apart

along the outcrops

of the Ferriferous and the Mercer ores.

The area

covered was over 100 miles in length

and from 10 to 25

miles in width. The distribution of the

furnaces in the

Hanging Rock District is shown in Map

1. The re-

quirements for the early furnaces or

those erected be-

fore 1840 were ordinarily placed at 100

men and 50

yokes of oxen. Those for the larger

furnaces built later

were considerably more, running even as

high as 200

laborers and 100 teams. Each furnace

thus constituted

a small settlement or village in

itself.

Influence on Early Development of

Ohio Valley 83

DIVERSITY OF LABOR

The charcoal furnaces provided a

diversity of labor,

as many tasks were required for the

production of iron.

The chief duties were erection and

repair of the furnace,

chopping and charring the wood, mining

ore and lime-

stone, hauling stock to the furnace,

smelting the ores,

hauling the iron to the market or to

the place of ship-

ment, dispensation of food for man and

beast through

the company store, and general management

of the en-

tire operation.

BUILDING OF THE FURNACE

With few exceptions the outer wall of

the stack and

the retaining wall for the stack yard

were built of sand-

stone from some convenient ledge

nearby. The stone

was quarried, blocked out in the rough,

and hauled to

the furnace site where the pieces were

then dressed to

the desired shape by the stonecutter

and laid in the wall

by the builder. The stone for the inner

lining was

selected with more care as the desired

material was a

fine grained, rather dense, clay-bonded

sandstone with

good refractory qualities. Usually this

was obtained

at no great distance as favored

quarries were located at

Junior, Hecla, Howard, Jefferson, and

Richland fur-

naces. The stone for the lining was

carefully dressed,

because it was required to fit the

circular battered wall

of the furnace. The masonry was laid in

a mortar com-

posed of sand and plastic clay. The

cast-house, engine-

house, head-house, and stock sheds were

constructed of

wood obtained from the furnace grounds.

The frame

was usually poles or hewn beams and the

siding and

sheeting just rough sawed lumber. The

chief roofing

|

84 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications |

|

|

Influence on Early Development of

Ohio Valley 85

material was oak shingles riven by

hand. Thus, with

the exception of some machinery and

equipment such as

engines, pumps, boilers, and rings for

the stoves, these

old charcoal furnaces were constructed

of materials

gathered nearby and were erected by men

from the

district.

CAPACITY OF FURNACES

The well equipped hot-blast charcoal

furnace made

approximately 3,000 tons of iron per

year. The con-

sumption of fuel was, on the average,

3.79 cords of wood

or 137 bushels of charcoal per ton of

pig iron. The

yearly requirement in terms of wood was

thus 11,370

cords. With the cold-blast charcoal

furnace the annual

tonnage was not far from 2,000 tons.

Under these con-

ditions of smelting, the fuel necessary

was considerably

greater, as 5.84 cords of wood or 215

bushels of char-

coal were necessary to make one ton of

iron. Such a

cold-blast furnace used 11,680 cords of

wood per year.

Thus, the mean requirement of the furnaces

of the area

was not far from 11,500 cords per

annum.

CHOPPING OF THE WOOD

Only the most skilled axman could cut

and then

rank three cords of wood per day. With

the average

workman two cords were considered a

fair day's work.

The cutting of wood usually extended

from the middle

of October to the middle of April or

for a period of

about six months. Deducting holidays,

stormy days,

etc., the average working time would

not exceed 20 days

per month or 120 days per season. On

this basis 48

men were required to produce the 11,500

cords of wood

necessary for the blast of the furnace.

86

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

Virgin timber produced approximately 40

cords of

wood per acre and average second-growth

not far from

20 cords. Hence, with a furnace in full

operation, the

area of timber land worked over each

year would vary

from 200 to 600 acres. The acreage

generally considered

sufficient by the furnace manager was

between 300 and

350 acres. As the period for renewal of

timber for wood

was 20 to 30 years, the furnace tracts

necessarily ranged

from 6,000 to 10,000 acres. Wood

chopping thus placed

a group of men with each operating

furnace, distributed

them over the timbered areas, and kept

them moving

somewhat from year to year.

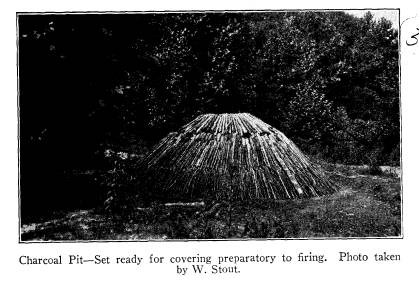

CHARCOAL MAKING

Charcoal making, one of the particular

and im-

portant operations in connection with

iron production,

was carried on by men, known as

colliers, who were

trained in the work and followed it

from year to year.

During the process of firing the pits

of wood, careful

attention had to be given day and night

in order to con-

trol the activity of the fires and

prevent loss either

through the complete consumption of the

wood to ashes

or through only partial charring

producing brands. The

colliers were a hardy lot, enduring

much from the heat

and dust of the pits and from the

adversities of the

elements.

A hearth upon which to burn the

charcoal was made

by leveling off a circular area 40 to

50 feet in diameter.

The location chosen was generally in

the valley along a

stream where water was available for

quenching the

freshly drawn charcoal. To this hearth

the wood was

hauled on sleds by oxen. The small wood

known as lap-

|

Influence on Early Development of Ohio Valley 87 wood was placed by the haulers in a ring around the edge of the hearth, except for a roadway across the center. The heavier or coarser wood was then set on end against this rick of lap-wood until all the interior space except the roadway was filled. A pit of average size contained from 35 to 45 cords of wood. The next step was the setting of the wood to form the pit which in its final shape was a mound-shaped mass 35 to 40 feet |

|

|

|

in diameter and 10 to 12 feet high. This required first the building of a chimney in the center by cribbing wood and filling the opening with chips and other kindling for starting the fire. Against this as a base wood was set on end, leaning inward at a slight angle, and packed as closely as possible. A second tier was placed on the first and the top rounded over with lap-wood. The entire mound of wood was then covered with leaves and this |

88

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

in turn with a few inches of earth or charcoal dust, well

compacted to prevent circulation of air

and erosion by

rains. The charring process was

commenced by start-

ing a fire in the opening in the center

of the pit. After

the kindling was well ignited the

cavity was filled with

wood and brands and then covered with

leaves and dirt,

the same as the rest of the covering of

the pit. Suf-

ficient air was admitted through small

vent-holes to

cause only a charring of the wood with

the loss of the

volatile components. The rate of

burning and the migra-

tion of the fire to the sides and to

the bottom of the pit

was controlled by the system of air

vents placed as the

collier saw fit. Through such means the

wood was con-

verted into charcoal for use in iron

smelting.

After the charring process had been

completed,

which required from 12 to 20 days, the

charcoal was

drawn from the pit, a small quantity at

a time, and

quenched with water. Care was taken to

keep that re-

maining in the pit so covered and

smothered as to pre-

vent undue oxidation. This charcoal was

then loaded

into the tall beds of the wagons and

transported to the

furnace by four yoke of oxen. The bed

of standard size

contained 200 bushels of charcoal. Such

a load weighed

close to two tons. A bushel of charcoal

contained 2,688

cubic inches and with average stock

weighed 20 pounds.

The harder woods like oak, hickory, and

maple made a

heavier, harder charcoal than the

softer woods like pop-

lar, linden, and chestnut. The firm,

compact charcoal

was more desired by the foundryman than

the light,

spongy kind, because it crushed less

under the weight of

the stock and because it carried

farther down in the

furnace.

Influence on Early Development of

Ohio Valley 89

The labor involved in the production of

charcoal may

be included under the following

divisions:

a. Preparing the foundation or

hearth. If a new

hearth were built, it required the

labor of one

man for one to five days, depending

upon the nat-

ural advantages or disadvantages of the

surface

features. Re-use of an old hearth made

neces-

sary only the raking back of the dust

for covering

the pit. For this one day's labor was

amply suf-

ficient.

b. Setting the wood. It took one

man about two

days to set a pit of 35 cords of wood.

c. Leafing and blacking the pit. The

task of cover-

ing the pit with leaves, setting the

wood by

stamping, and then covering the whole

with dust

or earth was equivalent to about two

days' work

for one man.

d. Charring the wood. The time

of firing a pit

varied with the practice of the

individual collier,

with the size of the pit, with the

dryness of the

wood, with weather conditions, and with

other

incidental factors. The older practice

was to

hold the fire for about 20 days, but

the later cus-

tom was to push the firing more

rapidly, com-

pleting the pit in about 12 days.

e. Drawing the charcoal. Under

common practice

the labor equivalent of one man for

four or five

days was necessary to draw a pit of

charcoal.

The work could not be rushed. Only a

small

amount of charcoal was drawn at a time

and the

90 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

opening of the pit sealed rapidly as

the exposed

fuel soon began to ignite and burn.

Usually two

men worked at the task.

MINING ORE AND LIMESTONE

The mining of ore occupied much time

and labor at

the charcoal furnaces as the supply was

drawn, with

few exceptions, from the thin beds that

outcropped in

the coal formations. As the entire area

is hilly and

naturally dissected, with a relief of

250 to 350 feet, and

as the rocks dip eastward normally at a

rate of 25 feet

per mile, the conditions favoring

mining changed with

the position of the ore on the hills,

that is, whether it

lay near the summits of the ridges, on

the steep bluff

of the hills, or near the valley floor.

The strata furnishing most of the

supply of ore

varied normally from three inches to

one foot four

inches in thickness. Locally, however,

small pockets of

ore were found two, five, or even more

feet in thickness.

The three most prominent ores were the

Little Red Block

or Lower Mercer, the Big Red Block or

Upper Mercer,

and the Ferriferous or Limestone. The

Little Red Block

ore lies usually from five to ten feet

above the Lower

Mercer limestone and is a true block

ore in that it mines

in rectangular blocks. The thickness

varies from two

to six inches, but averages close to

four inches. The

quality, for a coal formation ore, is

everywhere good.

The Big Red Block ore, with few

exceptions, lies on or

close to the Upper Mercer limestone or

to that horizon.

In southern Ohio the ore commonly marks

the place of

the limestone, as the latter is usually

absent. The de-

posit may be made up of one, two, or

even three distinct

Influence on Early Development of

Ohio Valley 91

benches of ore. The usual thickness of

the bed is from

six to 14 inches and the mean

measurement not far from

eight inches. This ore is rich in iron

and was well liked,

especially where it had been weathered

down along the

outcrop to a soft limonite. The most

successful char-

coal furnaces were those located along

the outcrop of

the Ferriferous ore on account of the

wide distribution

and the continuity of the bed and of the

quantity and

quality of the ore. Its stratigraphic

position is just

above the Vanport or Ferriferous

limestone, but the ore

is often present with good development

in areas where

the limestone is absent. The horizon

yields ore in two

forms. The lower one is an irregular

sheet deposit lying

on the limestone or on that horizon and

constituted the

dependable supply. The second form is

large nodules

of ore which are irregularly

distributed in a few feet

of shale that lies directly above the

lower ore and that

was known as the "ore slates"

by the miners. The com-

bined thickness of ore on this horizon

was from six to

eighteen inches and the average

measurement at least

ten inches. In general, the Ferriferous

ore was richer

than the other coal formation ores and

smelted readily

in the short stacks of the charcoal

furnaces. Other ores

drawn upon for limited supplies in the

Hanging Rock

District were Harrison, Guinea Fowl,

Lincoln or Jack-

son, Sand Block, Boggs, Canary, Red

Kidney, Yellow

Kidney, Peterson, Hallelujah, and Oak

Ridge.

The ores varied considerably in

quality. Under deep

covering all were bluish gray siderite

or ferrous car-

bonate. On protracted weathering along

the outcrop or

under shallow covering, the mineral

siderite was changed

to limonite, the hydrated ferric oxide.

The color of the

92 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

weathered ore ranged from dark buff

through shades of

red to deep brown. The purity of the

ore depended pri-

marily on that of the parent rock. Most

of them were

argillaceous in character, others were

siliceous, some

were decidedly calcareous, and a few

moderately phos-

phatic. In the natural form the better

ores had an iron

content of 30 to 40 per cent. Such ores

on calcination

yielded from 45 to 55 per cent iron. In

general, the

furnace managers estimated 2.63 tons of

raw ore to one

ton of iron.

The mining of the ores was largely

confined to strip-

ping along the outcrop, as usually only

the weathered

limonite ore was desired. Along the

sides of the hills

the operations were confined to narrow

benches, but

often near the summits of some of the

ridges they were

much larger in area. The old rule in

stripping was that

one foot of overburden could be removed

for one inch

of ore. The thickness of the ore,

therefore, determined

the depth to which stripping was

practical. Usually the

depth was less than 12 feet. The

stripping was done

largely by pick and shovel and a

wheelbarrow. Along

the ridges and on the more gentle

slopes of the hills and

where the ore had good thickness, the

team and scraper

were successfully employed. Most of the

work was done

by men and boys, but such labor was

also shared by the

women and girls. Where the ore was

exceptionally thick

and was overlain by a few feet of shale

for entry, reg-

ular drift mining was practiced,

occasionally in a large

way. The most prominent areas for

drifting were those

around Ellisonville and Dean in

Lawrence County and

near Vinton Furnace in Vinton County.

The hot-blast

charcoal furnaces, making 3,000 tons of

iron per year,

Influence on Early Development of

Ohio Valley 93

thus required 7,890 tons of ore and the

cold-blast fur-

naces, capacity 2,000 tons per year,

thus demanded 5,260

tons of ore. For a bed of ore ten

inches in thickness,

the yield estimated by the furnace

manager was 2,800

tons per acre. The actual area thus

worked over each

year was two, three, or more acres. The

price paid the

miner for stripping and raising the ore

ready for the

hauler varied much throughout the long

period of char-

coal iron making. The common limits

were usually be-

tween 50 cents and $1.00 per ton and

the average not

far from 75 cents. Delivered to the

furnaces the price

ranged from $2.00 to $4.00 per ton,

depending on the

length of haul, the richness of ore,

and other factors.

Considering one and a half tons of ore

a fair day's

yield and 250 days a year for outside

labor, the men

required in the ore fields would vary

from 14 for the

smaller furnaces to 21 for the larger

stacks.

The mining and the hauling were not the

only labors

expended on the ore, for it was all

calcined to expel the

volatile components and then screened

to remove the

"fines" before it was charged

into the furnace. The

elimination of the volatile matter,

which was about 16

per cent in amount and which consisted

mainly of hydro-

scopic and combined water and carbon

dioxide, not only

saved heat in reduction, but increased

the capacity of

the furnace. Moreover, this processing

could be done

more cheaply outside than inside the

furnace. The cal-

cination of the ore ordinarily took

place at the furnace,

but occasionally this was done near the

center of im-

portant ore fields, notably near

Ellisonville and Dean in

Lawrence County and at Creola in

Vinton. At all the

early furnaces and at many of the more

modern char-

94

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

coal stacks, the ores were burned in

large ricks or piles.

These were made by first placing a

layer of logs on the

ground with air-ducts to the center of

the ricks. The

logs were covered with fine wood and

this with a layer

of ore. The ore was then covered with a

layer of char-

coal brands and fine charcoal and this,

in turn, by ore.

Layer after layer of ore and fuel were

added until a

pile six to 15 feet or more in height

was accumulated.

A fire was then started toward the

center and at the

base of the pile and the mass allowed

to burn until the

fuel was all consumed. The calcined ore

was screened

to remove the fine, dusty parts before

charging into the

furnace. At a few of the later

furnaces, up-draft kilns,

patterned somewhat after lime kilns,

were employed for

roasting the ore, as a more uniform

product was ob-

tained. Through calcination, about 16

per cent volatile

matter was eliminated, limonites and

siderites were

changed to hematites, and usually the

texture of the ore

was rendered more open and porous,

inducing ease of

reduction in the furnace. From two to

five men were

constantly employed in the work.

Throughout the Hanging Rock District

the Vanport

or "Gray" limestone furnished

nearly all of the flux for

iron smelting. The stone was of good

quality for such

work, was exposed conveniently for

quarrying, and out-

cropped along the main line of

furnaces. The quarrying

operations were crude, because the

quantity of stone

used was small. Hand labor was employed

in stripping

the stone, in drilling the holes for

shooting, and in break-

ing up the stone for hauling. While

many of the fur-

naces had limestone convenient, others

were not so for-

tunate and had to haul their flux from

five to 15 miles.

Influence

on Early Development of Ohio Valley 95

The

Maxville limestone near the head of the Dever

Valley

in southern Jackson County and near Maxville

in

southwestern Perry County were used to a small ex-

tent.

Keeping the furnace supplied with flux required

the

labors of one man for mining and one man and a

team

for hauling the limestone.

The

average burden or half charge as calculated

from

the practice at many furnaces was:

Ore,

roasted ................. 1000 pounds

Charcoal

.................... 28

bushels

Limestone

................... 62

pounds

The

ore requirement to make one ton of iron was:

2.63

tons (2240 lbs.) raw ore

to yield one ton (2268 lbs.) iron

2.21 tons (2240 lbs.)

calcined ore to yield one ton (2268 lbs.)

iron.

From

the above, the total materials necessary to make

one

ton iron were as follows:

Ore,

roasted .................. 4950 pounds

Charcoal

.................... 137 pounds

Limestone

................... 307

pounds

The

yearly requirement for the production of 3,000

tons

of iron was accordingly:

Ore,

raw 7,888 tons (2240 1bs. each)

Charcoal 411,000 bushels or 11,370 cord wood

Limestone 411 tons (2240 lbs. each)

FURNACE

OPERATION

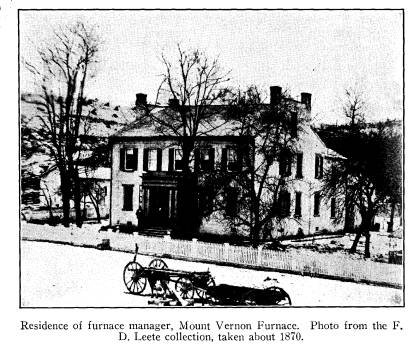

The

operation of the furnace alone required from

20

to 40 men. The one of most importance was the

general

manager who had charge not only of the fur-

nace,

but also of the timber and ore properties. He was

96

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

always respected and in many cases was

really a big

man in ability and in human interest.

Directly, the

operation of the furnace was in charge

of the foundry-

man or blower. His duty was to see that

the furnace

was properly charged with ore,

charcoal, and limestone;

that the slag was flushed and disposed

of; and that the

furnace was in good repair. Some of

these men were

very able in their work and eventually

moved up to simi-

lar positions in the more modern

furnaces. The duties

of the two engineers for day and night

turn were to

look after the engine and the boilers.

The charging of

stock took from five to nine men,

depending upon how

much screening of ore and charcoal and

breaking of

limestone was done at the furnace. A

keeper and a helper

on each turn opened the furnace for the

discharge of

iron and slag and regulated the

air-pressure. The labor

in the cast house required the work of

three to five men.

Here the iron was cast into pigs,

sanded while hot,

quenched with water, and then carried

to the cart or

tram-car. The pig beds and runner were

also made up

preparatory for the next cast. One man

with a horse

and cart was employed to remove the

slag from the cast

house. Usually from two to four men

were used on the

yard in piling iron, in loading wagons,

in supplying sand

and clay for the furnace, and in

cleaning up the yard.

At most of the furnaces, the company

maintained a store

which required from two to three clerks

and which car-

ried a stock of foods, hardware,

clothing, and feed. The

office force, from one to two men, kept

the books of the

furnace, paid off the workmen, and kept

the record of

the stock used at the furnace. Others

regularly em-

ployed were blacksmiths, carpenters and

a crib tender.

|

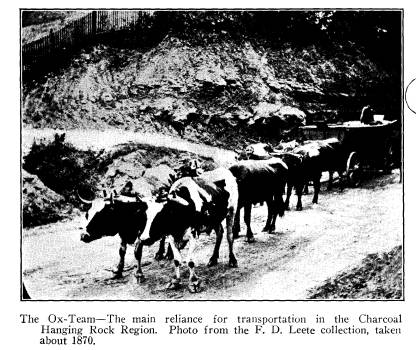

Influence on Early Development of Ohio Valley 97 MARKET FOR LOCAL SUPPLIES These charcoal furnaces provided a ready market for the food supplies for man and beast raised on the farms in the adjacent areas, as the furnace lands were gener- ally poor and were used chiefly for timber raising to provide charcoal. As previously stated, the usual re- |

|

|

|

quirement of a charcoal furnace was 100 men and 50 yoke of oxen. This meant a total of nearly 500 people in the community and these people had to be fed mainly by supplies obtained elsewhere than on the furnace lands. Along with the working cattle, there were cows, hogs, chickens, and dogs that increased the demand for suste- Vol. XLII--7 |

98

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

nance. To this end the farms supplied

grains, wheat,

and buckwheat for flour and corn for

meal; fruits, such

as apples, peaches, pears, and plums;

vegetables, such as

potatoes, tomatoes, turnips, cabbage,

and beans; meats,

both fresh and cured; and other

products; such as butter,

eggs, cheese, sorghum, and sauerkraut.

For the stock

the yield of the soil consisted largely

of corn, fats, hay,

and fodder.

Through such ready markets, with the

fair prices

maintained, considerable money was made

by the farm-

ers living within marketing range of

the furnaces in the

Hanging Rock District and located on

the better lands

of the Ohio, Big Sandy, Little Sandy,

Scioto, Little

Scioto, and Hocking Rivers and of Pine,

Symmes, Rac-

coon, and Salt Creeks. In fact, this

was the period of

real prosperity in these areas. Most of

the farmers

built comfortable homes and substantial

farm buildings,

kept the land well cultivated, and

accumulated modest

savings that eventually entered many

channels of educa-

tion, agriculture, industry, and trade.

SHIPMENT BY RIVER

All the iron made by the charcoal

furnaces of the

Hanging Rock Iron District from 1818 to

1856, except

small quantities used locally, was

shipped by way of the

Ohio River, because this was the only

artery for distri-

bution. The shipment included the

substantial outputs

of over 40 of the 69 furnaces. The

yearly tonnage of

these furnaces varied from 2,000 to

3,000 tons each with

a mean of not far from 2,500 tons. The

aggregate an-

nual shipment was thus around 100,000

tons. Charcoal

iron was marketed mainly in Cincinnati

and Pittsburgh,

Influence on Early Development of

Ohio Valley 99

but some of it went to the foundries

and rolling mills in

Portsmouth, Maysville, Louisville, St.

Louis, and New

Orleans. Not only was iron shipped out

of the district

by boat, but large quantities of

supplies for the furnaces

came in by water. This included much of

the food for

man and beast, and nearly all of the

clothing, hardware,

boots and shoes, and incidentals.

Cincinnati and Pitts-

burgh were the main supply points,

because the whole-

sale houses there were prepared to

handle such trade.

The iron was carried to the markets by

various means.

Small orders were shipped by

passenger-boats or by flat-

boats, and keel-boats, which simply

floated down the

river. In fact, these were the only

means of transporta-

tion at that time. Later when towboats

and barges

came in, all the large orders were

carried to their desti-

nations by the more efficient methods

of transportation.

Even after the advent of the railroad

into the area

(1856), the river carriers still

received a fair proportion

of the furnace trade. Thus, when fully

considered, the

charcoal furnaces in the Hanging Rock

Iron District

were an important factor in the establishment

of river

transportation and in its development

to a high efficiency.

Boating on the Ohio River during these

days was prof-

itable.

FURNACES AND RAILROADS

The first railroads in the Hanging Rock

Iron District

were planned for the transportation of

iron from the

furnaces to the Ohio River whence it

was taken by boats

to the markets. In Lawrence County on

the Ohio side

of the river, the Iron Railroad, only

13 miles long, was

built from Ironton to Center Furnace by

the owners of

charcoal furnaces along the route. It

began active oper-

100

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

ations in 1851 and served Olive,

Buckhorn, Mount Ver-

non, Center, Lawrence, Etna, Vesuvius,

and Lagrange

furnaces. In 1883 it was connected at

Center Station

with the Cincinnati, Hamilton and

Dayton from Wells-

ton which gathered iron from Latrobe,

Buckeye, Key-

stone, Limestone, Madison, and Gallia

furnaces. Later

the old Iron Railroad became a part of

the Detroit,

Toledo and Ironton. On the Kentucky

side a similar

railroad was built in 1867 from Grayson

to the Ohio

River at Greenup. It furnished

transportation for Pac-

tolus, Hunnewell, Laurel, Pennsylvania,

Argillite, and

Buffalo furnaces.

The Scioto and Hocking Valley Railroad,

which

after several changes passed to the

control of the Balti-

more and Ohio system, began train

service between

Portsmouth and Jackson in October,

1853. It was

routed to accommodate Scioto, Jackson,

and Bloom fur-

naces and its building was a stimulus

for the rapid erec-

tion, 1853 to 1856, of Pioneer,

Washington, Monroe,

Cambria, Jefferson, Madison, and

Limestone furnaces.

The completion of the main line of the

Marietta and Cin-

cinnati Railroad, now the Baltimore and

Ohio, in 1856,

led directly to the erection, between 1853

and 1858, of

Hope, Zaleski, Vinton, Hamden, Eagle,

and Cincinnati

furnaces in central and southern Vinton

County. All

the railroads built in the area before

1860 were either

influenced directly by the charcoal

furnace trade or they

were responsible for the building of

other furnaces

where their lines passed through the

ore fields. Thus,

with the railroads and with the

charcoal iron industry

in the Hanging Rock Iron District, each

played a promi-

nent part in the development of the

other.

Influence on Early Development of

Ohio Valley 101

LOCATION OF ROADS

Through the charcoal furnaces, hauling

of some

product or other originated in all

parts of the Hanging

Rock Iron District. Charcoal, ore, and

limestone were

gathered from every part of the furnace

lands and also

from many adjacent properties. Nearly

all the pig iron

was transported by wagon either to the

Ohio River or

to the railroads for shipment to the

markets. Food sup-

plies were collected from various sources

over a wide

area. Most of this was hauled by wagon.

The region

was thus thoroughly traversed by roads,

varying in

character from the sled roads through

the coalings to

those highly worn by travel. Naturally

the ones used

extensively were those with the most

direct route, with

the least resistance as to hills, with

the most firm foun-

dations, and with the best

accommodations for the fur-

naces and the people. Main arteries of

travel were soon

established and today these, with few

exceptions, still

retain their importance as both

regional and local thor-

oughfares. The charcoal furnaces

definitely established

the road system of the area.

SOCIAL LIFE

In general, the life throughout the entire Hanging

Rock Iron District was very much the

same, as the

people were doing like things, that is

chopping wood,

burning charcoal, digging ore, making

iron, and driving

teams. To some extent, however, each

furnace became

a center of a particular social unit,

due to the kind of

people congregating there, to the

clustering of the people

near the furnace, to the main arteries

of travel centering

at that place, and to a certain loyalty

of the people for

|

102 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications their particular community. The people were quite ac- tive socially and had many gatherings of the types fol- lowed during the furnace days. The school, located near the furnace, was used not only for educational pur- poses, but for spelling bees, by travelling shows, and by music teachers. Often the schoolhouse was used as a |

|

|

|

voting booth. Each furnace center had at least one church with services by either a resident or an itinerant minister. Sunday school, prayer meeting, and socials were also held there. The favorite loafing place of eve- nings was the furnace store where all subjects from running the government to who had the best hound dog were regularly discussed. The country dance was then |

Influence on Early Development of

Ohio Valley 103

at its height. These usually took place

at some of the

favorite homes with an old-time fiddler

or two to fur-

nish the music. "Coon" and

fox hunting were common

sports of the day and occasioned much

rivalry for the

best dog. Often each furnace had a

"bully" who pro-

claimed himself champion of the region

and was willing

to fight for such glory. Each year the

large circuses vis-

ited the main towns in the district. A

circus was an

important event, necessitating a

complete suspension of

all operations at the furnaces. On the

whole, the social

life at the charcoal furnaces was

original in many ways

and of a wholesome nature.

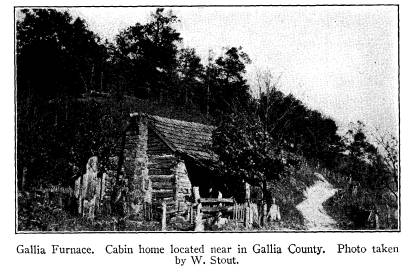

EFFECTS OF ABANDONMENT OF FURNACES

The closing down and abandonment of

these old

charcoal furnaces caused a marked

change in the entire

area. In only a few places were other

industries intro-

duced to take their places. The furnace

people were

thus forced to leave for other fields

of employment.

Many furnace tracts, formerly

supporting from 300 to

500 people, now have only an

impoverished remnant,

often not more than a few families. The

entire aspect

has changed; the furnace is now only a

crumbled ruin;

most of the dwellings are gone or in a

state of decay;

the church and school, even if

standing, show long neg-

lect, and the furnace lands are

deserted by the axman,

miner, collier, and teamster. The area

formerly supply-

ing an active industry of much value is

now devoted to

grazing land or to a timber or mineral

reserve. The

value of the property has thus changed

radically and its

ability to support people has decreased

tremendously.

These tracts are now on the tax

duplicate at low figures

|

104 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications and, therefore, produce little revenue to support the county. The progress is backward and not forward. The charcoal furnaces of the Hanging Rock Iron District thus had a marked influence on the region as a whole. They led to a rapid development of the area, to a rather thorough dissemination of the people over the entire field, to trade activities, both local and re- |

|

|

|

gional, to a hastening of efficient river transportation, to the introduction of railroads into the area, to the permanent location of major highways, and to a rather definite type of social life. The decline and abandon- ment of the furnaces has led to a decided retrogression, with a decline in population and in wealth and in the various activities which marked the prosperous days of the furnaces. |