Ohio History Journal

|

URBAN RIVALRY AND INTERNAL IMPROVEMENTS IN THE OLD NORTHWEST 1820-1860 |

|

by HARRY N. SCHEIBER |

|

|

|

At the very beginning of settlement in the Old Northwest urban commu- nities developed in response to the commercial needs of the surrounding country.* And almost as soon as they appeared, there was "urban rivalry," that is, competition among them for advantages that would promote their growth and enhance their attractiveness to emigrants and investors.1 The earliest rivalries usually involved competition for advantages that govern- ment might bestow. Designation as the county seat or as the territorial or state capital marked the beginning of growth for many a rude village in the West, and the pursuit of these choice prizes was inevitably marked by keen political struggles. The presence of federal land offices, colleges and acad- emies, or government installations such as arsenals and prisons was for many towns the only factor that permitted them to outdistance less favored rivals with equivalent natural or geographic endowments.2 NOTES ARE ON PAGES 289-292 |

228 OHIO HISTORY

Sustained urban growth and economic

viability were in most cases depend-

ent upon more than initial advantages

that this sort of government patronage

could provide. Probably the most

important single requirement for urban

growth and commercial development was

adequate transportation. Without

reliable transport facilities connecting

a town with an expanding hinterland

and with outside markets, there were

oppressive limitations upon growth.

The struggle for internal improvements

therefore became the cause of the

most vigorous and persistent rivalries

among western urban communities--

rivalries marked by intense ambitions,

deeply rooted fear of failure, and

ingenious employment of the instruments

of political and economic leverage

at the disposal of urban leaders.3

The period of early urban growth in the

Old Northwest coincided with the

period of canal construction by the

states. How, then, did urban rivalries

influence state transport policy in the

canal era, 1820-45? How did con-

tinued rivalry affect the planning and

construction of western railroads when

private promotion supplanted state

enterprise, from the mid-forties to 1860?

Before dealing with these questions, it

must be noted that self-interested

urban activities and urban consciousness

cannot be strictly separated from

the more embracing force of which they

were manifestations, that is, from

"localism," a collective

consciousness and sense of common interests among

the people of a given locality. The

definition of common objectives and self-

interest might find expression at many

levels, and often urban aims and

objectives were merely an intense

reflection of regional aims.4 Towns fre-

quently spoke in state politics for the

trade areas with which they were asso-

ciated; yet within intrastate regions

(as within interstate sections) cities

might compete for hegemony. New

transport facilities and redirection of

trade--or even the prospect of such

change--might alter drastically the

regional identification of given urban

centers.

The interplay of regional and local

rivalries at the state level is illustrated

in the history of Ohio's improvements

policy. The movement for construction

of a canal between Lake Erie and the

Ohio River, which, it was hoped, would

open eastern markets to Ohio farmers and

merchants, began to gather strength

about 1820 in response to construction

of the Erie Canal in New York. In

1822 the Ohio legislature assigned to a

special commission the task of plan-

ning such a canal. The canal

commissioners soon recognized that their

problem was as much one of politics as

of engineering. As long as the

project remained a subject of discussion

in general terms, optimistic business

and political leaders throughout the

state gave it their support. But once the

project took precise form and the

commission recommended specific routes,

the virtue of vagueness was lost, and

the towns and regions that would be

230 OHIO HISTORY

bypassed united immediately in

opposition to the proposal. Spokesmen for

the disappointed communities evoked the

specter of oppressive taxation,

argued in principle against state

intervention in the economy, and denounced

the commissioners for alleged

corruption. Yet some of the same men had

earlier been among the most outspoken

advocates of a state canal project.5

In 1825 the Ohio canal commission

recommended, and the legislature

adopted, a canal program that

represented a fusion of several important

regional interests within the state. Two

canals were authorized, rather than

the single work originally contemplated.

One, the Miami Canal, satisfied

Cincinnati's mercantile community and

southwest Ohio; it was to run sixty-

seven miles from the Queen City north

through the Miami Valley to Dayton,

with the understanding that it would

later be extended northward to the

Maumee Valley and Lake Erie. The second

canal, the Ohio Canal, followed

a wide-sweeping reverse-S-shaped route

from the Ohio River to the lake,

passing first up the heavily settled

Scioto Valley, then arching eastward to

the headwaters of the Muskingum, there

turning northward again to its

terminus on the lake shore at

Cleveland.6

This canal program gave new focus to

urban and regional ambitions,

which adjusted quickly to take account

of inter-regional connections and

new trade relationships that the canals

would create. In the first place,

within regions through which the canals

passed, there was an intensified

struggle for positions on the projected

works. Everywhere along the canal

routes there was speculation in new

town-sites. A Tuscarawas County pro-

moter expressed the thoughts of hundreds

like himself when he wrote to one

of the canal commissioners: "I

expect a new town will spring up [along the

canal], which, from the great trade

which must center there, from the coun-

try between us and the Ohio, must be a

flourishing one. But where the spot

is, I want you to tell me."7

Sensitive to the potential threat to their own

interests, established market towns in

the interior petitioned for construction

of feeder canals that would connect them

with the main works. In many

instances the townspeople offered to pay

a portion of the cost. Several towns

organized private canal companies to

build feeder lines, not in expectation

of direct profits, but rather to protect

their commercial position.8

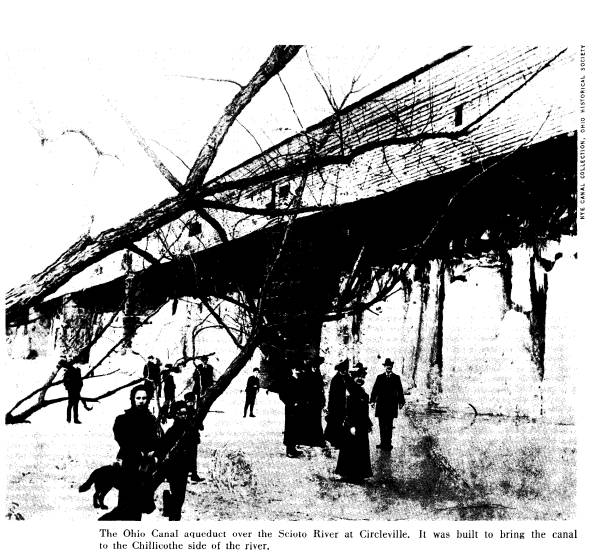

Events in the Scioto Valley, the

southern route of the Ohio Canal, indi-

cated the extremes to which localism

might run. Piketon and Chillicothe

had joined with other towns in the

valley to support the canal bill of 1825

in the legislature. But as soon as it

became necessary for the commission to

set the exact canal location, each town

advanced its own cause and all sense

of regional unity dissolved. The

Chillicothe interests were determined to

obtain a canal connection. They forced

through the legislature a resolution

|

|

|

ordering the canal commission to build the canal through Chillicothe, even if it was necessary to build a dam or aqueduct across the river in order to bring the canal through the town. The canal commission complied, crossing the river to place the route through Chillicothe. To avoid further expenditure the commission decided not to re-cross the Scioto below Chillicothe. Piketon and other communities on the opposite bank downriver opposed this action bitterly, since it would prevent them from achieving a canal connection, but they were unsuccessful in their protests.9 Ironically, the state's accommo- dation of Chillicothe quieted the clamor there for only a few months. Once actual construction had begun, neighborhoods within the town vied with one another in what may be termed "neighborhood rivalry," various factions demanding that a particular street or section of town be designated as the canal route. Passions ran high for several months, and the mayor finally had to hold a referendum on "the naked and abstract question" of the canal route.10 |

232 OHIO HISTORY

State officials systematically

exploited such local rivalries. Where the

canal might be located on either side

of a river, the Ohio commissioners

solicited donations of land or cash

from townspeople and landowners on

opposite sides of the stream,

indicating that the more generous communities

would be favored when the canal was

located. This practice often stimulated

unreasonable expectations and resulted

in bitter disillusionment.1

Once the initial canal undertaking was

approved, the "disappointed" com-

munities--those entirely outside the

region of the canals--did not give up

their quest for improved

transportation. On the contrary, they proposed a

multitude of new projects, many of them

reflecting an effort by ambitious

towns to overcome the lead of

commercial rivals that had obtained places

on the canals. "Shall narrow views

and sectional feelings withhold our

assistance from a work of such evident

public utility?" the promoters of

one new project asked the general

assembly. "Shall we, palsied by untimely

fears, stop mid-way in the career of

public improvement, to calculate the

cost, before our fellow citizens in

other parts of the State participate in their

advantages?"12

Such new improvements schemes disrupted

older regional alliances and

introduced new forces into state

politics. Sandusky's railroad project is a

case in point. Only a few years after

their town had lost to Cleveland in the

struggle for designation as the

lake-shore terminus of the Ohio Canal, a

group of Sandusky promoters requested

state aid for the Mad River and

Lake Erie Railroad. The Mad River

Railroad was planned in 1831 to run

from Sandusky southwest to Dayton,

which was then head of navigation on

the Miami Canal, and ultimately to

Cincinnati. When the first canal pro-

gram had been debated in the

legislature, six years earlier, the Miami Canal

proposal had been supported by the

western counties located north of Dayton

--but only because of the understanding

that the canal would be extended

northward as soon as finances

permitted. Having enjoyed the benefits of its

position as head of navigation on the

Miami Canal, Dayton now shifted its

allegiance, and the town's

representatives decided to support state aid for

the Mad River Railroad instead of for

extension of the canal."13 This move

threatened to strand the area to the

north, and the towns in that region (espe-

cially Piqua) resented what they

regarded as Dayton's treachery. "The Canal

must be extended," Piqua's newspaper editor declared,

despite "the selfish

policy of those, who at a former period

made such professions of friendship

to us; but who, since their views

have been accomplished, forget their

obligations."14

The projects that blossomed forth in

every part of the state also came into

conflict with one another in the effort

to secure the patronage of the legis-

URBAN RIVALRY 233

lature, which at this time commanded

only limited funds. If logrolling was

an important feature of the legislative

process, so too was the log jam. The

Ohio General Assembly was virtually

stalemated for several years in the

early 1830's because of conflicting

demands for internal improvements.15

The jam began to break when extension of

the Miami Canal and construction

of the Wabash and Erie Canal were authorized--but

only because the federal

government had provided land-grant aid

for these projects. Finally, the

pressure of local ambitions became too

great to resist further. In 1836-37

the legislature approved a comprehensive

system of new canals and state

aid to railroad and turnpike companies,

a program that within five years

would bring Ohio to the verge of default

on its enlarged debt. Every region

had to be satisfied, it seemed; every

little community able to advance half

the cost was to receive state assistance

in the construction of turnpikes or

railways.16

With adoption of the enlarged

improvements program, urban and regional

ambitions adjusted rapidly to the new

transportation developments. Many of

the patterns of localism and rivalries

witnessed a decade earlier now reap-

peared. In the Muskingum Valley, where a

project to improve the river for

steamboat traffic was undertaken,

Zanesville and Dresden fought over which

town should be the head of navigation,

just as Dayton and Piqua had strug-

gled for headship on the Miami Canal.

Meanwhile, Marietta, situated at

the mouth of the Muskingum, protested

that the size of the locks was too

limited. The vision of every town in the

valley appeared to be one of infinite

optimism and boundless growth. "We

look forward," a petition of Marietta

merchants declared glowingly,

and [we] see our situation placed on the

thoroughfare, between the Atlantic & the

Medeterranean [sic] of the North,

the Mississippi & the St. Lawrence. We look

forward to the arrival of the Ohio &

Chesapeake Canal and the Baltimore &

Ohio Rail Road. . . . We look &

expect to see the Ohio made slackwater by Locks

& dams, from Marietta to Pittsburgh

. . . & Lastly we expect to see the Locks,

on the Muskingum Improvement, increased.

. . . We wish to convince you, that

the discriminating principle, attending

the small locks, is derogatory to social

Commerce, & has been discarded by

all civilized nations. 17

In the Maumee Valley, then sparsely

settled, the people of several small

towns--Toledo, Maumee, Perrysburg, and

Manhattan--and the absentee

proprietors of the towns (including

several of the most prominent Ohio

political leaders), all had favored

construction of the Wabash and Erie

Canal, a project designed to continue

Indiana's Wabash and Erie Canal

from the state line through the Maumee

Valley to the lake. But once the Ohio

234 OHIO HISTORY

legislature had decided to undertake the

project, these villages competed

bitterly with one another for

designation as the terminus.18 Among the instru-

ments of rivalry employed were court

injunctions, petitions to the legisla-

ture and to congress, and pressure on

the United States General Land Office

to limit the extent of the federal land

grant by designating one of the com-

peting towns as head of lake navigation.

State officials finally decided to

satisfy all the major competing points

by extending the canal to the mouth of

the river, with terminal locks and

basins at Manhattan, Toledo, and Maumee.

To equalize the conditions of rivalry

the state agreed also to open all the

terminal locks simultaneously.19 Thus

even after a major improvement had

been authorized, the competition of

rival communities could serve to increase

the costs of construction.

Roughly the same patterns of localism

characterized the evolution of

public transport policy in the other

states of the Old Northwest. During the

early promotional phase of internal

improvements, when state officials or

private pressure groups were agitating

for projects in general terms, there

tended to be divisions between the

great trade regions of each state. In

Indiana, for example, the southern

river counties viewed with suspicion the

proposal for the Wabash and Erie Canal,

and they coalesced to press for

roads and railways from the interior to

the Ohio River.20 In Illinois, too,

the region tributary to the Mississippi

River and southern markets adamantly

opposed state aid exclusively for the

proposed canal to Chicago. The towns

on the eastern lake shore in Wisconsin

(still a territory) all sought canal

or railroad connections with the

interior; but they were prevented from

realizing their objectives because of

opposition in the northern region, which

demanded priority for the Fox and

Wisconsin river improvement project,

and in the western river towns.21

Once specific projects had been

formulated, broad regional divisions

gave way under pressure for more

localized objectives. "Most of the members

[of the legislature] vote for nothing

which does not pass through their own

county," the Indiana state

engineer complained in 1835. Indiana's Michigan

Road, supported in a general way by all

the Ohio River counties, became an

object of sharp urban rivalry when

designation of the southern terminus

had to be made. Similarly, the program

that the state's engineers submitted

to the legislature in 1835 was not

rendered acceptable until it had been

expanded elaborately, "to buy

votes," a year later.22 In Michigan all the

lake shore towns demanded connections

with the interior, yet no policy

could command adequate support until

one embracing the objectives of

every competing town had been

formulated. And so Indiana, Illinois, and

Michigan all adopted comprehensive

state programs that overextended their

URBAN RIVALRY 235

resources. In both Illinois and Indiana

the political strength of localism

was further manifested in provisions of

the law requiring simultaneous starts

on all projects; in addition, each of

the states' settled regions was granted

representation on the boards of public

works.23 Once construction had begun,

moreover, scores of proposals were put

forward in each state for branch

lines, feeder canals, and turnpike and

railroad connections designed to

satisfy the needs of towns outside the

immediate areas of the main im-

provements.4

Still another feature of urban and

regional rivalry as it affected state

policy concerned canal tolls. Toll

schedules were commonly established

by state authorities on a protectionist

basis. The states maintained two toll

lists--one for "domestic," or

in-state, manufactures and a higher schedule of

tolls for "foreign," or

out-of-state, commodities. In Ohio, for example,

manufacturers of glassware, iron, salt,

crockery, and other products were

the beneficiaries of protectionist

tolls.25 As long as canals remained the sole

means of cheap transport to the

interior, manufacturers located inland from

Lake Erie or the Ohio River enjoyed a

form of tariff protection from out-

of-state competition. Merchants at the

terminal cities on the lake and the

Ohio River condemned the protectionist

policy as one which imposed arti-

ficial restrictions upon the canal

commerce that was their economic lifeblood.

The conflict between terminal cities and

inland towns was expressed in the

1840's in a debate over wheat and flour

tolls. The millers of the interior

demanded tolls on unprocessed grain that

were proportionally higher than

tolls on flour. This, they argued, would

encourage Ohio's milling industry

and reduce the flow of Ohio grain to New

York State mills. Merchants and

millers at terminal cities opposed such

action; they favored equivalent tolls

on grain and flour (or even

discrimination against flour) as a means of

fostering the milling industry of their

cities or the export of increasing quan-

tities of grain.26

Similarly, merchants at Cleveland, then

gateway for import of salt from

the East, fought discrimination in salt

tolls that protected Ohio producers in

the central portion of the state. Thus

within the state there was a conflict

between mercantile and manufacturing

interests, comparable to the division

in national politics over tariff policy.

The issue of canal tolls cut across

party lines, and special regional

alignments were fostered by this important

question. State officials were forced to

mediate such conflicts, with no reso-

lution possible that could fully satisfy

all contending interests.27

In the period of canal construction,

urban and regional ambitions were

directed largely toward manipulation and

control of state policy. The panic

of 1837 and the post-1839 depression

marked the end of the era of state

236 OHIO HISTORY

canals in the Old Northwest. As the

depression came to an end in the mid-

forties a new internal-improvements

movement gathered momentum, with a

new set of conditions shaping the

character of the movement. In the first

place, there had been a revulsion

against further large-scale construction

by state government, the result of

scandals in management of the public

works, intolerable indebtedness, and

default on their debt by several states

in the depression period.28 In

the second place, the advantages of the railroad

over the canal had been demonstrated.

Construction of railways to meet

local needs was a task that many

communities believed they could undertake

independently of state aid, particularly

if municipal, township, or county

governments extended assistance to

private companies.29 This enthusiasm for

railroads was heightened by another

force: the infusion of eastern capital

into western railroad construction and

reorganization after 1845-46. Foreign

investors, too (particularly the

English), showed renewed interest after 1852

in purchasing railroad bonds or

local-government securities issued for rail-

road aid.30 Moreover, in the canal

states the railroad promised to liberate

urban centers and regions that had

formerly been at the mercy of geographic

conditions. Limitations of terrain that

had characterized canal planning

were no longer relevant, a change that

urban leadership was quick to com-

prehend. The new railroad technology

reopened the critical question of which

city would dominate trade in each region

of the Old Northwest. As Chicago,

Milwaukee, and St. Louis battled for

control of the Mississippi Valley trade

in the most spectacular western urban

rivalry, so too in every area of the

West towns competed for positions on the

new railroads and for hegemony

in local trade areas.31

Most of the projected western railroads

were designed at first to serve

primarily local needs and objectives.

This fact explains the enthusiasm with

which communities, small and large,

supported private railroad companies

with public aid.32 Among the

arguments of railroad promoters seeking local

subscriptions and public assistance were

many that had become familiar in

the canal era. Multiple market outlets

were a major objective of many com-

munities, and numerous railroad schemes

were designed to free towns from

"monopoly" conditions, under

which they were tributary to a single market;

in the same way, the state canal

programs had been designed to open alter-

nate markets to western producers

formerly dependent upon the New Orleans

outlet. Established metropolitan

centers, such as Cleveland and Cincinnati,

extended municipal aid to railroads in

an effort to multiply and extend their

transport radii or to obtain all-rail

connections with the East. Some railroad

promoters even advertised their projects

as potential links in transcontinental

systems that would carry the trade of

Asia and the Far West through a par-

URBAN RIVALRY 237

ticular town or village. And by the

early fifties there had emerged the well-

known competition among major cities for

designation as the eastern termi-

nus of a land-grant transcontinental

railway.33 Less pretentious communities

sought places on the new railroad lines

merely to survive, or else to over-

come advantages enjoyed by rival towns

on canals or rivers.34

Indicative of the emphasis upon local

objectives in railroad promotion

was the ambivalent western attitude

toward eastern influence. The western

railroad promoter was usually quite

willing to accept financial assistance

from established railroad companies, and

he eagerly solicited eastern invest-

ment in bonds or stock. But he generally

had to rely in the first instance

upon local resources, public and

private; and the prospect that outsiders

might control the enterprise could

hinder seriously his efforts to raise funds

locally. One Ohio railroad organizer,

for example, argued with his fellow

promoters in 1851 that it was

inadvisable to employ an engineer from the

East to locate the line. Local people

would, he said, suspect "that this

Eastern man would come here with Eastern

habits, feelings, associations and

interests, the effect of which must be, to give everything an

Eastern aspect."35

In the same vein, the president of the

New Albany and Salem Railroad in

Indiana wrote in 1852 that because most

of the stockholders lived along the

route, the company was protected from

"the prejudice that exists in the

public mind in many places against

[railroads], where they are looked

upon as monopolies owned and managed by

persons having no interests or

sympathies in common with them."36

Yet two of the strongest arguments

employed by western railroad promoters

to secure local support were that

their roads might one day merge with

others to form a large integrated

system or that they might bring an

eastern main line to the sponsoring

communities.37

Western railroad entrepreneurs

skillfully induced and exploited local

rivalries, as state canal authorities

had once done, by soliciting subscriptions

or donations from communities on

alternative routes. One may trace the

routes of many early western railroads

by naming the towns and counties

(seldom on a straight line!) that

extended public aid. Similarly, the major

eastern trunk lines--notably the

Pennsylvania and the Baltimore and Ohio--

gave financial support to several

parallel-running western railroads, thereby

stimulating competition among rival

communities on all the routes thus

aided.38

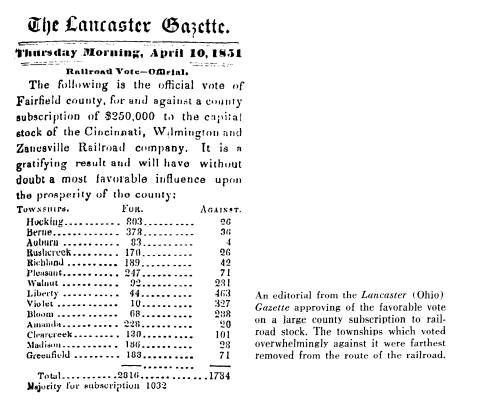

Private financing and public aid at the

local level were critical determi-

nants of the pace and character of

western railroad expansion. Urban rivalry

continued to find expression, however,

in the arena of the state legislatures.

Debate over charters often involved

bitter conflict over routes; and in some

|

238 OHIO HISTORY |

|

|

|

The Lancaster Gazette Thursday Morning, April 10, 1851 Railroad Vote-Omeint. The following is the official vote of Fairfield county, for and aginst a county subscription of $250,000 to the capital stock of the Cincinnati, Wilmington and Zanesville Railroad company. It is a gratifying result and will have without doubt a most favorable influence upon the prosperity of the county: Townships For. AGAINST Hocking ...... 803 ..... 26 Berne ...... 378 ..... 36 Auburn ...... 83 ..... 4 Rushcreek ...... 170 ..... 26 Richland ...... 189 ..... 42 Pleasant ...... 247 ..... 71 Walnut ...... 92 ..... 231 Liberty ...... 44 ..... 463 Violet ...... 10 ..... 327 Bloom ...... 68 ..... 288 Amanda ...... 228 ..... 20 Clearcreek ...... 130 ..... 101 Madison ...... 186 ..... 28 Greenfield ...... 188 ..... 71 Total ...... 2316 ..... 1784 Majority for subscription 1032 An editorial from the Lancaster (Ohio) Gazette approving of the favorable vote on a large county subscription to rail- road stock. The townships which voted overwhelmingly against it were farthest removed from the route of the railroad. cases railroad interests would block altogether the chartering of rival com- panies.39 Opposition to local aid was scattered, and not until 1851 in Ohio and long afterward in other western states was it effective. Urban leaders did occa- sionally divide over the question of priority in allocation of funds among several companies competing for a town's patronage. A few opponents of aid took an ideological position, condemning public assistance of any kind. There were also some instances of urban-rural conflict, with farming areas opposing county aid to railroads which, they averred, would merely enhance the wealth of already affluent market towns. The farm-mortgage railroad subscriptions notorious in Wisconsin-and to a lesser extent in Illinois- testify eloquently, however, to the fact that rural opposition to railroads was by no means universal. Finally, there were some instances of rivalry involv- ing towns within counties, with several vying for connections on the route of a railroad seeking county aid.40 The results of generous public and private support of western railroads were highly uneven. Whether or not their railroad stock paid dividends, |

URBAN RIVALRY 239

many communities were amply rewarded by

commercial advantages con-

ferred by the new transport lines.41

But precisely because the objectives

of western railway promotion had been

defined within a context of local am-

bitions, the reaction was severe when

these ambitions were frustrated.

Throughout the Old Northwest the people

resisted payment on bonds and

subscriptions that aided railroads never

built or which once built had fallen

victim to bankrupt reorganization.

Sometimes there was violence, as in

Athens, Ohio, where townspeople tore up

the tracks of the Marietta and

Cincinnati Railroad, which had bypassed

the town even though its citizens

had voted for county aid to the company.42 In the

1850's there appeared

anti-railroad sentiment that presaged

the Granger movement, a sentiment

stimulated by resentment against

emergent eastern dominance over railroads

built initially with local aid; the outsiders

often imposed rates unfavorable

to the western communities that had

helped build the roads.43

Whether or not the objectives of

westerners who supported early railroads

were later frustrated, the debates over

transportation heightened urban

community consciousness and sharpened

local pride in many western towns.

The issues concerning internal

improvements that dominated town politics

over many years constantly forced

farmers and urban residents alike to re-

examine their local interests, needs,

and hopes in a period of rapid change

in the West.

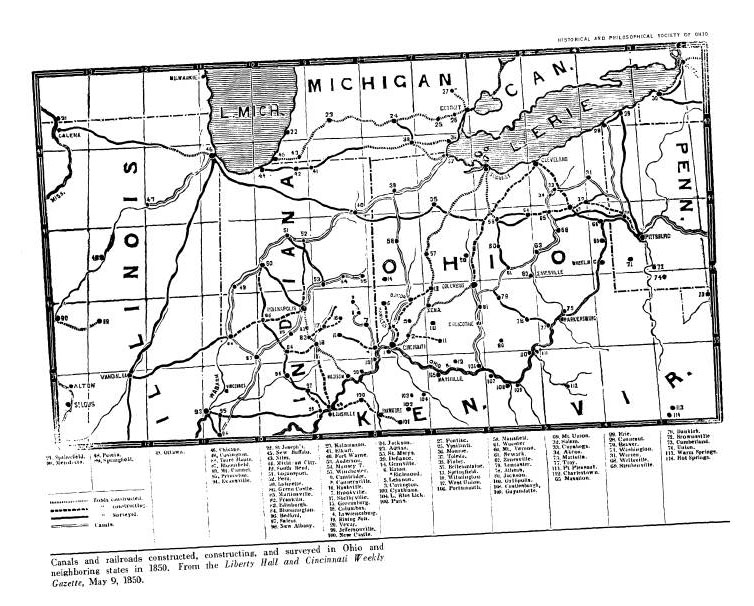

What occurred in the Old Northwest in

the period 1820-60 also charac-

terized development of the national

transportation system in the pre-Civil

War years: localism and regionalism were

so strong that they rendered

impossible any comprehensive, rational

planning of a system of internal

improvements.44 A glance at

the transport map of the West in 1860 reveals

the gross absurdities of parallel lines

and over-dense construction in many

areas. The highly rational response of

western leaders to their communities'

transport needs had led to a highly

irrational result. But the western

transport network included many lines of

communication, built mainly

with the resources of state and local government,

that were vital in the

development of a national economy. And

the growth of this transport net-

work had been influenced significantly

by the effects of urban and regional

rivalry.

THE AUTHOR: Harry N. Scheiber is an

assistant professor of history at

Dartmouth Col-

lege. He is now completing a book-length

study

of internal improvements and economic

change

in Ohio during the period covered in

this

article.