Ohio History Journal

|

|

|

THE FUGITIVE SLAVE LAW in the Eastern Ohio Valley by LARRY GARA The fugitive slave law of 1850 was an essential part of the sectional compro- mise of that year.1 As such it had ramifications that went far beyond the mere question of returning runaway bondsmen to their southern claimants. At times the symbolic significance of the enactment overshadowed its real impact on the lives of those whom it touched. Nevertheless there were some Americans of the 1850's who viewed the law as concerned primarily with the return of fugitive slaves, and some later historians have also accepted that point of view. "This law," said the Pittsburgh Gazette in October of 1850, "was doubtless drawn up with only one specific object in view--that of recapturing and returning to his owner, in the most summary manner, the fugitive slave." Calling attention to the law's harsh nature, the editorial continued, "In the pursuit of this object the most sacred rights, and the simplest dictates of human wisdom, were overlooked and disregarded."2 NOTES ARE ON PAGES 170 171 |

THE FUGITIVE SLAVE LAW 117

Despite the frequent repetition of

similar sentiments, the fugitive slave

law, in the Ohio Valley as elsewhere,

became the focal point of an extra-

ordinarily complex issue, which held

widely different meanings for the

various groups and individuals living in

the region. Among those whose

vital interests the law affected were

the slaveholders and non-slaveholders

who lived south of the river, the free

Negroes and fugitive slaves in Ohio,

and other valley states of the North,

the officials of the United States govern-

ment who were pledged to enforce the

law, the abolitionists, and leaders

of the various political parties, who

had to bear the brunt of the pressures

from all the others involved. The law

meant many things to the Americans

of the Ohio Valley and its meaning was

largely determined by the vantage

point from which it was viewed.

Those who lived in the slave states

south of the Ohio River, like their

fellow countrymen in the North, failed

to agree about the nature of the

fugitive slave problem or the wisdom of

the law. The majority of runaway

slaves who fled north were from border

states, and, although there was no

real danger of a mass exodus of

bondsmen, slave owners from those states

did face a practical problem. The

proximity of the free states and the

presence of abolitionists appeared to

some Kentuckians, for example, to be

the cause of much of their difficulty.

"Our slaves, not only singly but in

droves," commented a group of

Kentucky slaveholders in 1850, "are pirated

and purloined from us, into other

States, and there protected by laws, by

mobs and violence, in violation of the

spirit and the letter of the Constitution

of the Union." Henry Clay agreed.

"Of all the States in the Union, unless

it be the State of Virginia, the State

of which I am a citizen suffers most by

the escape of slaves to adjoining

States."3 When South Carolina's Senator

Andrew P. Butler marshaled support for a

new fugitive slave law, he

alleged that slave property worth

$30,000 was "abstracted from Kentucky

annually, by persons who inveigle the

slaves from the borders of Kentucky."

Butler also alluded to the

constitutional implications of the question. "It is

an invasion of recognized constitutional

rights by those who ought to respect

them," he said.4

While there was considerable--though not

unanimous--agreement on the

latter point in the South, the exact

number of fugitive slaves and the role

of abolitionist encouragement to run

away were far from proved. A fugitive

slave, if determined in his flight, was

a poor risk and a bad example to

others even when he was recaptured. The

market value of those known to

be habitual runaways was very low, and

the expense of capturing a slave

was sometimes more than he was worth.

Sympathy for fugitive slaves was

118 OHIO HISTORY

not uncommon and some who were

slaveholders themselves did not consider

it their business to return other

people's Negroes.5 It was not the practical

problem of returning fugitive slaves

that made the issue so heated but rather

the raising of it to an abstract

principle. In the North the fugitive slave law

became a symbol of southern aggression

and flouting of civil liberties; in

the South, it became the measure of

northern willingness to assume the pro-

tection of that section's basic rights.

One southern writer maintained that

it was "as much for the sake of

having the right recognized, as of enforcing

it, that impelled the South to make the

fugitive slave law a sine qua non of

the Compromise measures."

"They insist on the law," wrote a northern

Democrat, "because it is

constitutional, because in executing it we give them

assurance that we are willing and able

to abide by our constitutional engage-

ments, and are not disposed to abuse the

power of the federal government

now passing once for all, into our

hands."6

As incidents concerning alleged fugitive

slaves multiplied, many south-

erners saw in northern opposition to the

fugitive slave law clear proof that

their fears were well founded. The North

would no longer protect southern

property or southern rights. At times

the angry slaveholders called attention

to the value of southern business and

threatened economic retaliation if

things did not change. In 1857 a

Maysville newspaper commented: "The

constant intermeddling of free negroes

and some fanatical white persons

at Cincinnati, . . . with the slave

property of the South, is fast giving that

city a reputation that her enterprising

merchants will feel in the loss of much

valuable trade." The editor of the Cincinnati

Enquirer, too, was very much

aware that the city was "acquiring

an unenviable reputation as a depot for

the assemblage and collection of

fugitive slaves," a fact which would by no

means increase Cincinnati's popularity

with the states to the south. The

"pestiferous abolition agitators

and demagogues" damaged the best interests

of the city when they outraged "all

the laws of comity and good neighbor-

hood" and also violated a

"solemn constitutional compact." The editor was

confident that the majority of citizens

in Cincinnati did not approve the

"forays upon the property of their

neighbors in Kentucky," and deplored

the thought that they would have to

suffer for the acts of a few, which they

entirely disapproved. They would

cordially approve vigorous government

efforts to put down the

"Negro-Underground-Railroad thieving," he re-

marked, which was such a reproach to

their "good name as neighbors and

sister States in a common Union."7

Even in Kentucky, however, there existed

sentiments in opposition to the

fugitive slave law, or at least such

sentiments existed and were openly ex-

THE FUGITIVE SLAVE LAW 119

pressed in 1851. In the spring of that

year nine citizens of Lewis County,

representing the non-slaveholding class,

objected to a former governor's

statement that Kentuckians would be

unanimous in regarding a repeal of

the fugitive slave law as a dissolution

of the Union. These citizens denied

that the opinion of some of the state's

31,000 slaveholders could represent

the opinion of 600,000 non-slaveholders.

The group resolved that so far as

its members were informed,

"intelligent and influential non-slaveholders

regard the Fugitive Slave Bill as

unconstitutional and anti-Christian." The

admiration they felt for free

institutions convinced them that the North

would remain firm in its purpose to

repeal the bill in a legal manner, "and

that it will be as much opposed at the

South as at the North when the light

shines as abundantly here as it does

there."8

Although opinion north of the Ohio River

was also diverse, there was

little disagreement among the colored

residents, both fugitive slaves and

free Negroes. To them the law presented

a serious threat, and when it was

first passed some felt that they were in

imminent danger of enslavement.

The insecurity produced by the new

legislation created near panic among

the Negroes of the valley region. Many

considered flight to Canada, and

in the fall of 1850 there was a mass

exodus of Negroes from Pittsburgh.

A number of small groups left in September,

and the Pittsburgh Gazette

commented, "The passage of this law

will have the effect of banishing the

great majority of the escaped slaves to

the British Possessions, where, at

last, they can look on themselves as freemen,

and meet on equal terms those

who before held them in bondage."

By early October three hundred had

fled from Pittsburgh and Allegheny City,

but the migration gradually slowed

down.9 As it became apparent

that the fears of the Negroes were not well

founded, they began to use other methods

than flight to gain their ends.

One mass meeting of colored citizens

passed a resolution urging officials to

resign rather than enforce the fugitive

slave law. The Negroes hoped that

no qualified person in Pittsburgh could

be found "so far beneath the level

of a gentleman, . . . to act as Slave

Catching Commissioner for Southern

nabobs, who despise doing the miserably

mean dirty work for themselves."

Some of the colored people went so far

as to arm and form militia com-

panies to protect themselves against the

dangers posed by the terrifying

law.10

A number of abolitionists believed the

hysteria unwarranted. Thomas

Garrett told William Lloyd Garrison that

he doubted very much if there

would be more arrested under the new law

than under the old, because of

an increase in the number of those who

were willing to give shelter and

120 OHIO HISTORY

protection to the fugitives. Another

Quaker abolitionist told a Friends

meeting he did not think the Negroes'

danger "was much increased" by

the new law and "advised Friends to

counsel them to quietness and for-

bearance." The abolitionists of

Salem, Ohio, also believed the panic was

unnecessary.11

Subsequent events tended to confirm the

correctness of those who pre-

dicted that the 1850 law would add very

little insecurity to the lives of

colored people in the North. Only a

small number of fugitive slaves were

arrested and returned to slavery under

the terms of the 1850 act. The total

for the United States was probably not

much more than two hundred, and

about eighteen of those were in the

eastern Ohio Valley.12 In addition, there

were several attempted arrests which

failed because of the interference of

outsiders and at least two cases in

which the alleged fugitives were found

to be free Negroes and released by the

authorities. The law, though favor-

able to the slave owner, nevertheless

operated on the side of justice on some

occasions where free Negroes were

falsely accused as fugitives.

The rendition of fugitive slaves aroused

considerable interest and varied

reactions among the citizens of the Ohio

Valley. When George Washington

McQuerry, who had lived in Ohio three or

four years and had married a

free Negro while there, was arrested as

a fugitive in Cincinnati in 1853,

both James G. Birney and John Jollife

contested the legality of the proceed-

ings. Justice John McLean heard the

legal arguments but declared the law

constitutional and ordered the fugitive

returned to his master in Kentucky.13

In 1856 the case of Margaret Garner

attracted nationwide attention. She

and seven other fugitives had fled from

Kentucky and were arrested by a

United States marshal's party in a house

near Cincinnati. The deputies fired

several shots and broke into the house.

Upon entering they discovered that

Margaret had killed her ten-year-old

daughter to prevent the child's return

to slavery. Because the woman was under

arrest as a fugitive slave and

also liable for prosecution for murder

by the state, a drawn-out jurisdic-

tional dispute followed. Local

abolitionists supported the move to have

Margaret placed under state rather than

federal custody, but a United States

judge upheld the doctrine of national

supremacy and ordered the fugitives

remanded to Kentucky. Later efforts to

have Margaret returned for trial in

Ohio failed, and the Cincinnati

Enquirer alleged that the move was really

a ruse to get her out of the South and

free her from bondage. Also futile

was a move to prosecute the United

States marshal for contempt of court

because he had failed to produce the

fugitives when requested by the state

court. The pro-Democratic Enquirer rejoiced

when a federal judge upheld

|

|

|

the marshal in his pursuit of duty. The decision, commented the Enquirer, "vindicates in becoming terms, and with legal ability and precision, the sovereignty of the United States from outrageous encroachment and viola- tion. With a strong arm it protects an officer of the General Government in the discharge of his duty, whom it was sought to prevent therefrom through the agency of fanaticism, demagogism and ignorance."14 The Garner rendition case was not the only one involving violence. In 1857 a pair of fugitives defended themselves against arrest in Cincinnati, and one of them was fatally wounded in the scuffle.15 An attempt to take three fugitives into custody in Iberia resulted in a riot. Several people were injured, and a mob tore most of the clothing from one of the deputies and threatened to lynch him before permitting him to depart.16 Some other fugitives proved much less difficult to the authorities. After two years in Ohio, Mason Barbour was arrested near Columbus and returned to slavery. According to a newspaper account, "the 'property' expressed himself perfectly satisfied with the arrangement. He said he had enjoyed two years of freedom, and had worked most of the time, and had not a single five cent piece to show for his services, and could not have any less |

122 OHIO HISTORY

if he worked a life-time for his

master." He was satisfied to return to his

old home "and he went, without a

murmur."17

Mason Barbour was an unusually docile

fugitive. The possibility of

violent resistance, rescues by groups of

free Negroes and abolitionists, and

hampering legal moves probably made

those who were hunting fugitive

slaves prefer taking them quickly, by

force if necessary, and without the

regular legal procedure. Twice as many

fugitives were remanded to slavery

by arbitrary action of slavecatchers or

kidnapping as by the regular legal

channels, and the threat from kidnappers

was greater than from the law.

While the law provided protection for

the free Negro, kidnappers frequently

attempted to force such persons into

slavery. Occasionally kidnappers were

discovered and arrested. In 1860 in

Cincinnati a white man posing as a

steamboat captain tried to entice a

Negro stevedore into a ferryboat, pre-

sumably to take him south. When the

intended victim sensed the situation

and began to run, the pretended captain

pursued him and proclaimed him

a runaway slave. The free Negro was

saved by the intervention of a white

man who recognized him, gave the would-be

abductor a severe trouncing,

and had him arrested on a charge of

attempted kidnapping.l8

The widespread unpopularity of the

fugitive slave law in the North prob-

ably did as much as anything to make

federal law enforcing officers reluctant

to return slaves under its provisions.

The law seemed harsh and unjust,

and many citizens who had little or no

sympathy with the abolitionists

resented that part of it which tried to

elicit their cooperation in returning

fugitives to southern bondage. The fact

that it was a concession to the

South, and was demanded so emphatically

by that section, only added to

northern irritation. At least one

federal deputy marshal in Ohio resigned

rather than execute the odious law, and

even those who supported the law

in principle sometimes objected to

certain of its features or the way it was

being enforced.l9

The Democratic, pro-compromise Cincinnati

Enquirer admitted that the

statute was unjust and urged that some

of its worst features be eliminated.

The provision that testimony of one

witness could send a Negro into slavery

seemed unfair when the alleged fugitive

had no opportunity to prove that

he owed no service to his claimant.

"No man can stand up in the free States

and defend this provision of the

fugitive law," commented the Enquirer,

"and the sooner it is amended the

better." The Democratic paper further

complained that alleged fugitives were

given no time to procure witnesses

on their behalf. The Enquirer later

raised objections when a New York

commissioner, hearing a fugitive slave

case, decided that he had no power

THE FUGITIVE SLAVE LAW 123

to compel witnesses to attend a hearing

or to answer questions at the

hearing.20

Some of the extremist acts of the

federal government also caused mis-

givings among the northerners who had

supported the compromise of 1850

as an effort to keep a severely strained

Union together. When land and

naval forces were ordered to Boston to

assure a fugitive's return, the Enquirer

objected; such a show of force was

unnecessary, and the order would only

increase the excitement. After alleged

fugitives were forcibly rescued by

mobs and sent along their way in

Syracuse and in Christiana, Pennsylvania,

the government attempted to prosecute

some of the rescuers for treason.

The Enquirer regretted such

extreme action by the administration. "The

attempt to make treason out of a

resistance to the execution of a law of the

United States in time of peace, is

simply ridiculous," it commented, "and

must bring into contempt the authority

that makes it." 21

Very few northerners supported the

fugitive slave law without reserva-

tions, and the authorities were

extremely reluctant to act in such a way as

to create a large number of antislavery

martyrs. Fewer than fifteen incidents

involving rescues or attempted rescues

of fugitive slaves led to prosecutions

under the law in the entire nation,

though several of these involved a

number of defendants. Cincinnati was the

scene of four such prosecutions.

In 1857 David Waite and James J. Puntney

of Adams County were arrested

and accused of helping eight slaves of a

Kentucky master to escape. Puntney

was released after a hearing before the

United States commissioner in

Cincinnati, and Waite was tried and

freed when the jury could not agree

as to his guilt. The alleged owner of

the slaves gave such contradictory

testimony that he was brought before the

commissioner on a charge of

perjury, though later acquitted.22

In 1857 an attempt to arrest a fugitive

slave named Addison in Champaign

County touched off an involved legal

dispute between United States and

Ohio officials. Addison himself escaped,

but when the United States

marshals tried to arrest four white men

who had allegedly assisted him,

there followed several armed clashes

between the marshals and a sheriff's

posse. Before the squabble ended the

federal authorities had arrested

some members of the sheriff's posse for

violating the fugitive slave law,

and Ohio had arrested the marshal and

his deputies for contempt of a state

court and assault. United States

District Judge Humphrey H. Leavitt

decided that the marshals were wholly

justified in ignoring state writs and

added that the fugitive slave law had to

be obeyed regardless of prejudice

against it. After a year of prolonged

wrangling the state dropped charges

|

|

|

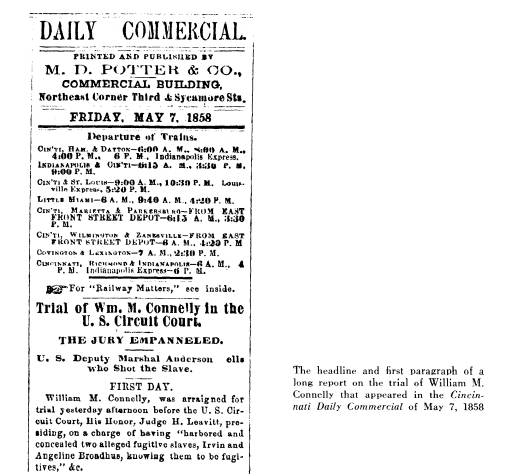

against the marshals when the federal government agreed to drop its charges against the sheriffs.23 The prosecution of William M. Connelly in 1858 attracted far more attention than any of the others tried in the Queen City. The previous year two fugitive slaves had been found in a room rented by Connelly, who was a member of the staff of the Cincinnati Commercial. The arrest of the fugi- tives involved a deadly struggle, in which several deputies were wounded and one of the slaves was seriously hurt. The slaves were remanded and Connelly avoided arrest by leaving the city. The following year he was arrested in New York and returned to Cincinnati for trial.24 From beginning to end the Connelly case provided dramatic material for newspaper copy. The courtroom was crowded and prosecutor Stanley Matthews had to contend with a defense team composed of ex-governor Thomas Corwin and ex-judge John B. Stallo. Rumors that the trial would "make very curious revelations with regard to the Underground Railroad" in Cincinnati heightened interest in the proceedings, though no such revela- tions were forthcoming. The trial lasted several days. Connelly was con- victed, fined, and sentenced to twenty days in jail.25 By the time he entered the jail Connelly was a famous antislavery martyr. |

THE FUGITIVE SLAVE LAW 125

Groups of visitors flocked to his cell,

including delegates from Methodist

and Unitarian conventions meeting in the

city. The prisoner was so popular

that his jailer finally decided to leave

his cell door unlocked in order to

facilitate the matter of ushering in

visitors. When Connelly's brief ordeal

ended, Cincinnati's turner society

arranged a mammoth celebration of his

release, complete with parade and a mass

meeting, at which the former

prisoner gave the major address.

Republican politicians and the abolitionists

made excellent propaganda use of

Connelly's imprisonment.26

To the abolitionists the fugitive slave

law gave new ammunition for

their propaganda war against the

peculiar institution of the South. With

the intensification of sectional

differences and the abolitionist appeal to the

cause of civil liberties they gained a

large audience previously unreceptive

to their message. Those abolitionists

who were providing tangible aid to

fugitives on their way to Canada

continued their work with little or no

interference. Levi Coffin, the organizer

of such activity in the Cincinnati

area, often kept fugitives in his house

"openly, . . . without any fear of

being molested." Wives of

abolitionists and other women who sympathized

with the cause volunteered for work in

sewing circles which provided clothing

for the destitute fugitives going

through the city.27

Far more abolitionists indicated a

willingness to aid the fleeing slaves

than actually rendered such assistance.

After 1850 antislavery meetings

invariably passed anti-fugitive slave

law resolutions framed in strong and

uncompromising language. The Garrisonian

Western Anti-Slavery Society

meeting in Salem, Ohio, in the fall of

1850 resolved that the newly passed

law was "but a stronger

demonstration of the unjust, inhuman, God-denying

character of the American Constitution

and Union" and avowed their

"determination to treat it, and its

authors with deserved contempt, and the

government from which it emanated with

abhorrence and execration." In

obedience to the "higher and divine

law" they further resolved to "en-

courage the poor bondmen and bondwomen

to escape from their masters

by offering them shelter, protection,

concealment, or any other aid or

comfort in our power to afford

them." 28

A group meeting at Senecaville in

November 1850 passed similar resolu-

tions and declared "that we will

not obey the requirements of that law,

but will trample them with scorn,

contempt and indignity, beneath our feet."

They characterized the northern

congressmen who had voted for the law as

"traitors to God, liberty, and the

dearest rights of man" and "unfit to

make laws for any people or nation,

either christian or heathen." "Their

names," they said, "should be

handed down to posterity branded with

126 OHIO HISTORY

disgrace and eternal infamy." The Enquirer's

editor commented that he

"did not suppose that such crazy

people . . . existed in any part of Southern

Ohio." 29

The return of George Washington McQuerry

to slavery in 1853 inspired

even stronger comment. That summer the

Western Anti-Slavery Society

resolved: "That it is a mockery of

truth, and an insult to the commonest

understanding to call Ohio a free State,

while a husband and father, innocent

of crime, may be seized by foreign

ruffians in his own house, dragged from

his wife and helpless infants, . . .

incarcerated in our jails, and driven

heavily manacled through the streets of

our Queen City"--all "sanctioned

and confirmed by the supreme law of the

land.30

Besides rendering direct aid to fugitive

slaves and passing resolutions

against the hated law, abolitionists

used legal measures to attempt to free

slaves passing through Ohio with their

masters. Most such attempts failed,

but all of them attracted attention to

the problem of slaves in the free

states at a time when northerners began

to envision a slavocratic conspiracy

to open all American territory to

slavery. The most famous of such cases

was that of a sixteen-year-old slave,

Rosetta Armstead, who came into Ohio

with a friend of her master, who was

taking her from Louisville to Virginia.

While she was in Columbus a group of

abolitionists and Negroes informed

her that Ohio was a free state, and the

sheriff took her to court on a writ

of habeas corpus. When Rosetta told the

court she wished to be free, the

judge pronounced her free and appointed

a guardian for her. Rosetta was

later arrested under the fugitive slave

law, but after an involved legal tangle

she regained her freedom when the United

States commissioner decided

against her master.31

In 1855 the slave Celeste was freed on a

writ of habeas corpus in

Cincinnati. She had been brought there

by her master, who deserted her

without paying her steamboat passage

from New Orleans, and won her

freedom after she told the court her

master had taken her north for the

purpose of freeing her.32 Several

other slaves were denied freedom in the

state courts, and some of them openly

stated that they preferred to return

to slavery rather than remain in Ohio.33

In 1860 the abolitionists lost a

fight to free a twelve-year-old slave

whose master was taking him to Missouri

on a steamboat. The court ruled that the

stopping of boats at a landing

was incidental to the right of free

navigation, and Ohio law could not

apply in such a case. The court

remarked, as the Enquirer put it, "that, while

we should carefully maintain our own

rights, yet the Courts must also see

to it that the rights of our neighbors

were not infringed." 34

THE FUGITIVE SLAVE LAW 127

The abolitionists who spearheaded these

legal moves were a small minority

in the Ohio Valley. The Enquirer once

estimated that they totaled no more

than a thousand in Hamilton County, and

when a southern paper referred

to a state "as strongly tinctured

with Abolitionism as Ohio," the editor

accused his southern colleagues of

ignorance of the true state of affairs.

It was, he retorted, "a few

indefatigable ultras" making a "loud noise

and din," when "in truth, not

one man in one thousand has any sympathy

with them, much less connection or

agency." 35 While the indignant editor

was literally correct, the southern

paper had not wholly missed the mark.

The fugitive slave issue did enable the

abolitionists to influence the thinking

of many who had no overt connection or

sympathy with the antislavery

movement. It was their most effective

propaganda issue and they used it

constantly after 1850.

At the same time the abolitionists found

the fugitive issue so useful for

their purposes, politicians found it

irksome and explosive, especially after

the Republicans replaced the Whigs as

one of the nation's two leading

parties. Democratic and Whig leaders

recognized the importance of the

compromise of 1850 as a last desperate

measure to prevent the disruption

of the Union, though they also had to

take account of popular resentment

against the fugitive slave law in large

sections of the North. Eventually

the Democrats staked their cause on

preserving the compromise and the

newly organized Republicans on an appeal

to northern pride and interests.

In their early years the Republicans, as

a new party in opposition to the

Democratic national administration, placed

considerable emphasis on states'

rights. The Republican-dominated Ohio

legislature of 1855-56 not only

urged the repeal of the fugitive slave

law but also passed a habeas corpus

act to make its enforcement more

difficult. This was actually an attempt to

interfere with the execution of a

federal law in Ohio. Local Republican

spokesmen endorsed the states' rights

policy. In 1857 the Republican Xenia

News criticized the law and maintained that the people of

Champaign County

and the rest of Ohio would not permit

enforcement of the measure. "The

force of that law's infamous

provisions is about done in Ohio." the

paper

commented flatly. Such language brought

a sharp retort from the Democrats,

whose leading Cincinnati organ pointed

out "that the entire Black-Republican

party of Ohio," leaders and rank

and file, had labored to make the fugitive

slave law "obnoxious and infamous,

so that it will become inoperative and

virtually be repealed, without the

interference of Congress." Commenting

on the Republicans' personal liberty

laws, the Democratic editor asserted

that the Republicans were "the

enemies of the Constitution." He arrived at

128 OHIO HISTORY

that conclusion because the

constitution, which was the supreme law of the

land, imposed an obligation in relation

to fugitive slaves which the Republi-

cans disregarded and did all in their

power to render inoperative.36

Some aspirants for political offices

were directly affected by their views

on the fugitive slave law and its

enforcement in Ohio.37 In 1859 Chief

Justice Joseph R. Swan, who had a

radical anti-Nebraska record, lost the

nomination for reelection because he had

upheld the prosecution of the

rescuers in the Oberlin-Wellington

rescue cases when they came before the

state tribunal. With the support of a

strong antislavery delegation from the

Western Reserve, the Republican

convention snubbed Swan and nominated

William Y. Gholson of Cincinnati, whose

supporters assured the delegates

that he was sound on the fugitive

question. Later evidence published by the

Democrats seemed to prove Gholson far

from sympathetic with the abolition-

ists. Nevertheless, he defeated his

Democratic opponent in a campaign which

revolved largely around the fugitive

slave law issue.38 It is difficult to tell

just how the candidates' positions on

the fugitive slave law influenced the

election, but the explosive nature of

the question undoubtedly contributed

to the emotional emphasis in state and

national politics in the 1850's.

Little did those congressmen who voted

for the fugitive slave law of 1850

realize the many ramifications that law

would have. As an amendment to

one of the nation's first statutes and a

supplement to a clause of the consti-

tution it seemed only to provide slave

owners with additional protection for

their peculiar type of property. But in

the Ohio Valley and in other parts

of the nation the new measure

contributed greatly to the increase in mis-

understanding between the sections. Few

slaves were remanded from the

valley and even fewer abolitionists were

prosecuted for helping slaves

escape, yet the impact of the law proved

much greater than the numbers

involved. To the residents south of the

river, the Negroes, the officials, the

abolitionists, and the office seekers,

the law posed new problems or presented

new opportunities. It was one of a

number of factors which molded opinion

and convinced northern residents of the

valley that they and others living

on free soil had a way of life superior

to that of their southern neighbors,

and that if necessary they would prove

that superiority by force of arms.

THE AUTHOR: Larry Gara, an associate

professor of history at Wilmington

College, is

the author of The Liberty Line: The

Legend

of the Underground Railroad.