Ohio History Journal

MILDRED COVEY FRY

Women on the Ohio Frontier:

The Marietta Area

It is difficult for the present-day

American woman living in a

modern suburb to comprehend the physical

rigors, the loneliness,

and the mental anguish suffered by those

pioneer women who left

comfortable New England homes, journeyed

eight hundred miles to

the wooded, "savage" Northwest

Territory, and then settled in crude

log cabins or houses. A better

understanding of that period in his-

tory can be gained by learning about

life styles of women on the

Ohio frontier during the last few years

of the eighteenth century.

Men may have the distinction of being

the first to step on Ohio

soil, but women were also adventuresome

and intrepid, and they

arrived shortly afterward. On April 7,

1788, a small group of forty-

seven men, led by Rufus Putnam, arrived

at the present site of

Marietta, Ohio. Many of these men were

veterans of the American

Revolution, ranging in age between 30

and 50 years, and they were

looking for adventure, as well as better

opportunities and land than

were available in New England.' In June

of that same year, Mary

Owen - the wife of James Owen of South

Kingston, Rhode Island -

and forty other settlers joined the

earlier arrivals. Mrs. Owen, who

served as a nurse for an invalid judge

on the westward journey, is

considered the first woman inhabitant of

this Northwest Territory

settlement.2 Some soldiers at

Fort Harmar, directly across the

Muskingum River, had their wives with

them, but these women

were considered "temporary

sojourners," and not permanent

settlers.3 More families arrived in

Marietta during August, and by

Mildred Covey Fry is Library Office

Manager of the Education/Psychology Library

at The Ohio State University. Her

article was the winner of the amateur-avocational

historian category of the Ohio

Historical Society's recent essay contest.

1. Samuel P. Hildreth, Pioneer

Settlers of Ohio (Cincinnati, 1854), 102, hereafter

referred to as Pioneer Settlers.

2. Mary Cone, ed., Life of Rufus

Putnam With Extracts From His Journal (Cleve-

land, 1886), 110, hereafter referred to

as Rufus Putnam.

3. History of Washington County,

Ohio, 1788-1881 (Cleveland, 1881), 52,

hereafter

referred to as Washington County,

Ohio.

56 OHIO HISTORY

the end of 1788 nineteen families were

living in the small wilder-

ness community. Women, then, were living

in Marietta within three

months after the arrival of the first

Ohio Company expedition. And

during the following months, more women

and children journeyed

over the eastern mountains and

subsequently participated in the

development of the first permanent

settlement in the Ohio Country.

The earliest pioneer families were from

Massachusetts, Connecti-

cut, Rhode Island, and New Hampshire.

Their journey from these

New England states to Marietta was

approximately 800 miles and

usually took eight to ten weeks for

small wagon parties to complete.

They left the Boston area and traveled

through Massachusetts, Con-

necticut, New York, New Jersey, and

Pennsylvania. The rough

Forbes Road (or Pennsylvania Road)

became the connecting link

between the northwestern states and the

new Ohio River

settlement.4

The small, narrow, covered wagons used

for such journeys meas-

ured approximately four by sixteen feet.

These narrow wagons had

to carry families, food, hunting gear,

furniture, and clothing. There-

fore, a family could transport only

household items essential for

frontier living, such as beds, wooden

eating utensils, a spinning

wheel, and iron pots for cooking. As a

matter of necessity, then,

women had to leave many cherished pieces

of handcrafted furniture

behind due to the lack of space in the

small wagons. Benjamin

Franklin Stone, who journeyed from

Rutland, Massachusetts, to

Marietta with Rufus Putnam and his

family in 1790, recorded the

following incident on one such wagon

trip:

It seemed a vast enterprise to go 800

miles into a savage country, as it

was then called. We were eight weeks on

the journey. Among other prepara-

tions for the journey, my mother and

sister Lydia had knit up a large

quantity of socks and stockings. They were

packed in a bag, and that bag

was used by the boys who lodged in the

wagon, for a bolster. By some means

the bag was lost out of the wagon or

stolen. The boys missed it, of course, the

first night. Next morning, Sardine went

back the whole distance of the

previous day's journey, inquired and

advertised it, but without success. I do

not remember how many pairs of stockings

were in it, but from the size of

the bag I judge there were at least one

hundred. One pair to each of the

family were saved, besides those we had

on our feet, being laid aside in

another place to be washed. It was a

severe loss. My mother had foreseen

that we should have no sheep for some

time in Ohio and had labored hard to

4. Rufus Putnam: A Massachusetts

Empire Builder (n. p., n. d.), 6,

located at the

Ohio Historical Society, Columbus, Ohio.

Women on the Ohio Frontier 57

provide this most necessary article of

clothing for her family. And so it was.

We had no sheep till six years after

that time.5

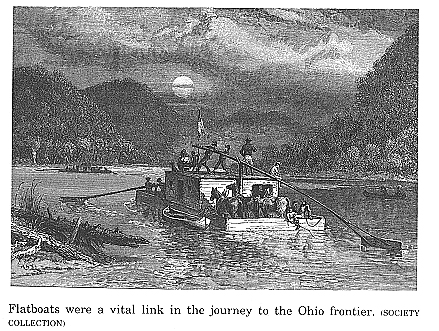

After trekking through the expanse of

five states, these New Eng-

land pioneers placed their belongings on

boats at Simrell's Ferry

near Pittsburgh in western Pennsylvania

and then made their way

to the Ohio River for the last leg of

the long arduous journey. In

September 1791, Eleazer Curtis, his wife

Eunice, and their six chil-

dren, left Litchfield County,

Connecticut, with two wagons, two

horses, and four oxen destined for

Marietta. Walter Curtis, a child

in this small party, later recorded his

recollections of one such trip

down the river:

At Simrell's Ferry we sold the horses

and one yoke of oxen with one

wagon. We purchased a flatboat about

fifty feet long, half covered, in the

bow of which we placed one yoke of oxen

and some hogs. Aft, under cover,

were the families and furniture. We

drifted in too close to the Virginia shore

when a tree hanging over the bank caught

one of the projecting studs and

tore a plank off and the water rushed

in. My Father caught up a feather bed

and stuffed it into the hole. The women

and children were put through a

hole made in the side of the boat for

dipping up water and placed in a canoe.

A young man by the name of Tollman,

becoming frightened, jumped upon

the tree and being heavily clothed, fell

into the river and drowned.6

The entire journey was exhausting for

all of the travelers. Men,

women, and children often walked beside

their wagons on the long,

rough road to the Ohio country. Men had

to provide for and protect

the families, as well as drive the team

of oxen. The women's tasks

were equally arduous, for they had to

care for their children; espe-

cially the infants; prepare family meals

over open fires; nurse illnes-

ses and injuries; and tend to the

clothing, bedding, and other house-

hold needs.

Families, especially the women, left

their New England homes

with mixed emotions. Rich land and

exciting opportunities were

available in the Northwest Territory,

but leaving behind family

members and long-established friendships

for the unknown was dif-

ficult for both adults and children.

Most New England women had

grown and lived, never venturing away,

in the same localities where

they were born. They had not traveled

extensively like their hus-

5. Benjamin Franklin Stone, "From

Rutland To Marietta," New England Maga-

zine, New

Series XVI (April, 1897), 215.

6. Walter Curtis, "Recollections of

Pioneer Life," 1870, Vertical File, Manuscript

1241, Ohio Historical Society.

58 OHIO HISTORY

bands, many of whom had served in the

Colonial army during the

American Revolution, and thus were

apprehensive about the condi-

tions they would encounter upon their

arrival in the strange unset-

tled land beyond the mountains.

Two young women recorded their

impressions after they settled in

Marietta - "a savage country."

One was Minerva Tupper Nye, the

daughter of General Benjamin Tupper and

the young bride of Icha-

bod Nye. She wrote to a friend back in

Massachusetts on September

19, 1788, one month after her arrival at

Campus Martius, the fort

which served as shelter and home for the

early pioneers. She penned

these thoughts:

We now live in the city of Marietta

where we expect to end our days. We

find the country much more delightful

than we had any idea of: we have

formed some acquaintance that are very

agreeable. I supposed by this time

you have heard we are all killed by the

Indians, but kind providence hath

preserved us from their savage hands.7

Two months later, Rowena Tupper,

Minerva's older sister who

later married Winthrop Sargent, the

secretary of the Northwest

Territory, also wrote to the same family

friend:

I cannot think it will be disagreeable

to hear, of the health and welfare of

a friend or friends: in particular

those, whose lot is [sic] cast them hundreds

of miles distance from you, in a savage

land, which might greatly raise your

curiosity. You doubtless have had

various conjectures concerning our situa-

tion. I wish, my Dear, it was possible

to give you an exact idea of it. This I

am persuaded, that we are much happier

than you concive [sic] of. The

country has been so spoken of, that it

is needless for me to say more than

that, it answers every expectation. The

society far exceeds whatever my

ideas had formed, and I think should

Heaven but spare my life, I shall spend

a very sociable Winter. The inhabitants

increase very fast. Our buildings

are decent and comfortable. The Indians

appear to be perfectly friendly,

their encampments are in sight of our

buildings, but not withstanding their

professed friendship, we are not

unguarded. There is a guard placed every

night.8

Despite whatever previous misgivings

they had, women adjusted

quickly to their new wilderness

surroundings. Most families in

general stayed in Ohio and established

new lives, although some

7. Minerva Tupper Nye to Mrs. Stone, 19

September 1788, Manuscript Collection

210, Ohio Historical Society.

8. Rowena Tupper to Mrs. Stone, 18

November 1788, Manuscript Collection 210,

Ohio Historical Society.

|

Women on the Ohio Frontier 59 |

|

|

|

settlers simply could not adjust to Ohio's early primitive frontier conditions and thus returned to New England. Because these pioneers had left behind relatives and friends in the East, receiving any news from them was a most important, anticipated event. Many men had delayed bringing their families from New England until they could build cabins and plant corn, and thus longed for news from their loved ones. Women, who had left behind parents, sisters, brothers, older married children, and old friends, always waited anxiously to receive any word from home, and young people, hoping to hear from close friends back East, watched for the arrival of the mailboat in Marietta. Rowena Tupper arrived in Marietta with the first company of families on August 19, 1788. By November of that year, she was anxious to receive any news from friends, and she expressed her feelings in a letter, dated November 18, 1788, to one such friend in Chesterfield, Massachusetts:

But hark! What do I hear? Below some voice saying, Col. Oliver is now landing, is it possible! With what alacrity will I fly to meet them, that I may hear from my worthy friends in New England. You surely have written to me. With what eagerness will I grasp at your letter. Have you not written everything you know? but I must away. I have now returned to close my |

60 OHIO HISTORY

letter, but with a heavy dejected heart.

What do you suppose my feelings

must have been when I was denied a

single line from my friends. Is it

possible that you have forgotten Rowena?

I cannot persuade myself to be-

lieve that . . . Present compliments to

all inquiries. I shall never more

trouble them until I have received some

in return.9

Minerva Tupper Nye expressed her desire

to be near enough to

converse with a friend named Betsey

Stone. She wrote in a letter

dated September 19, 1788:

O! Betsey, how do you do! How I would

like to see you. Happy should I be,

if I could make you a visit this

afternoon, but I must think no more of this.

If I could see you, I could tell you

more in one half hour, than I could write

in a day.10

Thus, although Ohio's early settlers

were well occupied with the

task of creating an orderly existence on

the frontier, they remem-

bered and longed for any news from their

former homeland. New

arrivals from the northeast who brought

information with them

were eagerly received, and Marietta

inhabitants anxiously awaited

the arrival of mailboats, hoping that

each one would bring word

from family and friends. During the

early years of settlement,

however, mail service to Marietta was

irregular, with letters often

remaining at Fort Pitt in western

Pennsylvania for weeks before a

traveler going down the Ohio River would

carry them the remaining

distance.11

Pioneer women had little time for

leisure and not enough time to

complete the work expected of them.

Among their responsibilities

were: milking the cows; cooking and

baking; preparing flax; spin-

ning, weaving, and making clothes for

large families; planting and

caring for small vegetable gardens;

making soap and candles;

washing and caring for clothes; cleaning

houses; and the rearing of

children. The frontier woman by

necessity assumed the roles of wife,

mother, and housekeeper; counselor,

educator, religious instructor,

and doctor; and craftsman, weaver, and

farmer, while leaving men

the responsibility for securing meat,

planting, harvesting and

grinding the grain, fighting Indians,

and building cabins and furni-

ture.

9. Ibid.

10. Nye to Mrs. Stone, 19 September

1788, Manuscript Collection 210, Ohio His-

torical Society.

11. Jerry B. DeVol, "Ohio's First

Post Office," The Tallow Light, II (November,

1967), 125.

Women on the Ohio Frontier 61

Women on the Northwest Territory

frontier married while still

young. While men could marry at

seventeen with parental consent,

young women could marry, again with

consent, at the age of four-

teen. Early marriages and large families

were generally the rule on

the frontier, for as soon as a boy could

do the work of a man on the

farm, he was considered capable of

supporting a family; and as soon

as a girl could bear children,

preferably sons, she was considered

capable of marrying and starting a new

family.12

The frontier woman was a rugged

individual, and childbirth was

not permitted to interfere with her

routine. Neighbors, or a midwife,

usually helped with the painful delivery

of children. Some people

thought of children as economic assets,

while others took seriously

the Bible's admonition to "be

fruitful and multiply." Still others

gave the matter little thought; they

just had annual "crops of chil-

dren." Generally babies did not

receive special attention - they

certainly were not rare. The concept of

"child care" was still far in

the future. Instead of a pacifier,

babies were given a piece of bacon

rind, and it was attached to a string so

it could be retrieved if

accidentally swallowed. Therefore, the

fittest survived, and the re-

mainder "the Lord seen fit to take

away."13

Hard work and frequency of childbirth

took their toll of women.

Many "lost their bloom of

youth" while still in their teens; they were

aged by thirty and old by forty - if

they were still alive, for many

women died while relatively young. In

1775 the life expectancy at

birth was thirty-four years for males

and thirty-six for females, and

by 1850, seventy-five years later, the

life expectancy for both males

and females had risen by only four

years.14

Life on the Ohio frontier, then, was

difficult for women. By ne-

cessity, they worked long, exhausting

hours, in addition to giving

birth to numerous children, usually

without the assistance of a

qualified physician. These brave, rugged

women played a vital sup-

portive role in the advancement of the

western frontier.

Although some early Ohio frontier women

were fortunate enough

to establish households in what for them

were luxurious dwellings

- many of Campus Martius' houses had

shingled roofs and brick

chimneys - many other women were forced

to set up house, at least

for a time, in structures that ranged

from the primitive to the barely

livable. For example, some settlers had

to survive in a temporary

12. Byron H. Walker, Frontier Ohio (Columbus,

1972), 100.

13. R. Carlyle Buley, The Old

Northwest: Pioneer Period 1815-1840, 2 Vols.

(Bloomington, Indiana, 1951), I, 309-10, hereafter

referred to as The Old Northwest.

14. Ibid., 309, and "76 Life

Ceaseless Laboring," The Advocate, 4 August 1976, 9.

62 OHIO HISTORY

shelter or a lean-to from several months

to a year while ground was

cleared and corn was planted. Buffalo

hides lined the interior of the

lean-to and also served as mattresses

and covers. A fire in front of

the open side of the structure provided

warmth in winter and protec-

tion from "wild critters."

When time permitted, however, the

pioneer and his neighbors constructed a

log cabin; this was referred

to as a "cabin raising" and

was usually accomplished in one day.

Later, the owner sawed or chopped out

openings for doors and win-

dows. Heavy window shutters and doors

were hung for the safety of

the family, while skins or greased paper

served in place of window

glass. A wide opening was cut in one of

the walls, and a fireplace

was constructed. Although some cabins

had wooden floors, many

had earthen ones. Cabins, like lean-tos,

were considered temporary

structures.15

Some of these cabins were about as

primitive as the lean-tos.

During the late 1790s, Thomas Rogers was

returning to Chillicothe

from Kentucky when he and a companion

were delayed by a terrible

snowstorm. The two men came across a new

cabin on Paint Creek,

where they were given shelter for the

night. Rogers later penned

this description of that dwelling:

The cabin had a roof but no door shutter

and no chinking nor daubing.

There was a woman and two or three

children. Her husband was not at

home. He was out on a bear hunt. So we

cut and got in plenty of wood and

kept up a large fire all night, the snow

pouring in through the cracks of the

cabin. The woman and children took one

corner, laid down what bedding

they had and covered themselves with

deer and bear skins. Just at night

two other travelers came in also. So we

all lay on the floor the best we could.

We were glad to see day ... I believe it

was the coldest night I ever passed in

the woods.16

Improvements to a cabin, and the

eventual construction of a new

house, were made as the family grew and

money became available.

Hewn logs replaced round bark-covered

timbers, and puncheon

floors were laid. Lofts were sometimes

added, thus increasing the

capacity of the cabin, and often an

annex which served as a kitchen

was built. In many cases, the original

cabin became an annex when

a larger home was built. By 1800, many

log cabins had been re-

placed by larger, more comfortable farm

houses; glass was available

for windows, and small sheds were

replaced by larger barns. By

15. Washington County, Ohio, 51;

Buley, The Old Northwest, I, 142-43.

16. Thomas Rogers, "Reminiscences

of a Pioneer," Ohio Archaeological and His-

torical Publications, XIX (1910), 206.

Women on the Ohio Frontier 63

1803, houses in Marietta were vastly

improved. In that year Thad-

deus Mason Harris of Massachusetts

traveled through the area and

noted in a journal he kept that Marietta

had "ninety-one dwelling

houses, sixty-five of which are frame or

plank, eleven of brick, and

three of stone."17 As

time went on, then, Ohio's frontier women,

especially those in Marietta proper,

were provided with houses

which were more than simply shelters

against the weather.

The interior of the early Ohio cabins

was often as crude as the

exterior, and thus taxed the abilities

of even the most energetic

housekeeper. Many cabins were sparsely

furnished at first, with the

bulk of the furniture usually being

handmade and primitive. For

example, the Eleazer Curtis family

settled near Belpre. Their son,

Walter, described the interior of their

home:

The tables were made by splitting lumber

into slabs and dressing it into

boards and making these into the desired

shapes. The bedsteads were made

by placing low posts in the floor and

laying slats from these to a crack in the

side of the cabin. A board, placed upon

pins in the logs, was the receptacle

for the pewter dishes and wooden

trenchers. The gun was hung upon hooks

fastened to the wall. The floor was of

puncheon or boards and was destitute

of carpets.18

Anna Strong was a young bride on the

northern frontier in 1804.

Later, she "looked back" and

took inventory of her household

furnishings:

Well here we are with shakes over our

heads and puncheons under our

feet. Our chimny [sic] back of logs, our

hearth beaten clay, our chamber

floor slip rails, our window sash and -

were planks, our table planed boards

with cross legs, our chairs three legged

stools for the convenience of an

uneven floor, one bed and bedding with a

triangle bedstead, one trough to

salt our pork in, two cucumber pails, a

washtub made of salt barrel, a poker

for tongs and a shingle for a shovel, a

nice bread tray and some smaller

ones, a splinter broom, large chest and

a smaller one.19

Eating utensils at first consisted of

wooden bowls, trenchers and

noggins (a small mug or cup). Later,

pewter dishes, plates and

spoons were purchased, and large iron

pots, baking kettles, and iron

17. Buley, The Old Northwest, I,

144-45; "Rustic But Heartwarming," Columbus

Dispatch Sunday Magazine, 4 July 1976, 26; Thaddeus Mason Harris, The Journal

of

a Tour Into The Territory Northwest

of The Allegheny Mountains; Made In The

Spring of The Year 1803 (Boston, 1805), 122-23.

18. Curtis, "Recollections of

Pioneer Life."

19. Anna Gillett Strong, "A

Memorial to My Children," 1858, Vertical File, Manu-

script 55, Ohio Historical Society.

64 OHIO HISTORY

skillets were absolutely indispensable.

These cooking utensils were

literally the backbone of fireplace

cooking, as evidenced by one

humorous incident. Major Ezra Putnam

supplied his son with a

"large iron dinner pot" before

the young man moved to Big Bottom,

north of Marietta. After the January 2,

1791, Indian massacre

there, a messenger brought the news to

Marietta. Major Putnam

listened to the sad story and finally

broke in, "Did you see or hear

anything of my big pot?" General

Rufus Putnam, losing all patience,

turned his large eyes square upon the

elderly man and said, "Damn

your big pot!"20

Women worked hard to maintain clean and

neat homes for their

families, a most difficult task in the

early cabins. It was almost

impossible to dust such crude furniture,

and keeping clean a cabin

with an earthen floor was a prodigious

undertaking. Mrs. William

Moulton, the wife of one of the original

settlers in Marietta, provides

a good example of a woman concerned

about her reputation as a

"good housekeeper." In case of

an Indian alarm, the women and

children had been instructed to hurry to

one of the blockhouses.

During one such alarm, Mrs. Moulton

reacted in the following

manner:

The first admission to the central

blockhouse was Col. Sproat, with a box

of papers for safe keeping; then came

some young men with their arms; next

a woman with her bed and her children;

after her, old William Moulton,

with his leathern apron full of old

goldsmith's tools and tobacco. His daugh-

ter, Anna, brought the china tea-pot,

cups and saucers. Lydia brought the

great bible; but when all were in,

"mother" was missing. Where was

mother? She must have been killed by the

Indians. "No," says Lydia,

"mother said she would not leave

the house 'looking so': she would put

things a little to rights." After a

while, the old lady arrived, bringing the

looking-glass, knives and forks.21

The old adage that "woman's work is

never done" certainly applied

to these early Ohio frontier women who

labored from sunup to sun-

down to maintain comfortable homes for

their families. In the late

1700s and early 1800s, clothing was made

in the home. Although

women played a crucial role, the task of

providing clothing became a

family-centered project with each member

of the family having a

function to perform. Men were

responsible for hunting and skinning

the deer, then later, shearing the

sheep. Flax was planted by the

20. Stone, "From Rutland to

Marietta," 220.

21. Elizabeth F. Ellet, The Pioneer

Women of the West (Philadelphia, 1852), 183-

84.

Women on the Ohio Frontier 65

men, but boys were in charge of weeding

the flax fields. Spinning

and weaving were time-consuming, but

necessary, tasks for the

frontier woman. An essential household

item, the spinning wheel

accompanied the pioneer woman in her

move westward. Children,

especially girls, were taught by their

mothers to spin and weave at

an early age; looms were built for girls

as soon as they were big

enough to sit on a loom bench. Men, too,

sometimes worked the

looms. In short, all members of the

frontier family participated in

some manner in the making of clothing.22

The clothing of frontier women was

generally simple and func-

tional, and lacked "style."

Women wore simple, collarless dresses

made of linsey-woolsey. Skirts were long

and full, and an apron was

usually worn over them. A kerchief was

sometimes worn around the

neck or a shawl around the shoulders.

Pins or hooks served as

fasteners on "everyday

clothing"; buttons and collars appeared only

on better dresses. Underclothing was not

worn by most frontier

people before 1840, for it was too

expensive and considered unneces-

sary. Women usually wore moccasins

instead of shoes, since they

were easy to patch and thus more

practical. Women who were for-

tunate enough to own shoes kept them for

Sunday religious services;

they would carry the shoes and then put

them on as they approached

the "meeting house."23

Women served as tailors for their

husbands by making hunting

shirts, coats, pants, and moccasins from

deerskin. After the deerskin

had been prepared for use, the women cut

out articles of clothing

with a knife. An awl was used for a

needle, and sinew, instead of

thread, for sewing. Trousers or breeches

were often called "leather

organs" because of the noise they

made as a man walked. Men also

wore loose-fitting shirts made of

linsey-woolsey, belted at the waist

with deerskin thongs or a sash.24 Dr.

Samuel P. Hildreth arrived in

Marietta in 1806 at the age of

twenty-three with a new diploma

from the Medical Society of

Massachusetts. He described the

apparel of an early household of

pioneers who had moved to Ohio

from Virginia:

The dress of both men and women was

either of homespun linsey-woolsey,

or dressed deer skins. Their feet were

protected by moccasins and every man

22. Marion L. Channing, The Magic of

Spinning, 4th ed., (Marion, Massachusetts,

1971), 16.

23. Buley, The Old Northwest, I,

209-10.

24. Curtis, "Recollections of

Pioneer Life."

66 OHIO HISTORY

wore his hunting shirt, secured around

the loins by a leather belt, to which

was attached a large knife with a stout

buck horn handle. Caps made of the

skin of a raccoon or fox, with the tail

attached behind, covered their heads.25

As time passed and money and more

materials became available,

clothing styles began to change. People

could buy "stylish store-

bought" clothes in large cities

such as Cincinnati, as well as smaller

communities like Marietta, by the late

1830s, thus freeing women

from many of their spinning and weaving

chores. By 1840, a pioneer

was most conspicuous if he appeared in

public wearing a coonskin

cap, fringed pants held up by a drawstring,

and carrying a long deer

rifle.26

The early settlers on the Ohio frontier

existed on the area's fish,

game, berries, and vegetables, and it

was primarily the task of

women to prepare these foodstuffs.

Sufficient wildlife remained

available, although there were some food

shortages. Buffalo were

prize sources of meat. Joseph Gilman,

who was later appointed a

judge for the General Court of the

Northwest Territory, journeyed to

Marietta in 1789 with his wife and son.

Gilman claimed that buffalo

meat was "better than any beef he

had ever eaten." Moreover, in the

early 1790s deer and turkeys were

plentiful on the river bottom lands

in the area. During the winter of

1792-93, two men killed forty-five

deer while traveling to the nearby White

Oak settlement. Beef,

milk, and butter were scarce, however,

since there were so few cattle

in the area. The early settlers did own

a few hogs. The pioneer

housewife fried everything that could

possibly be fried, for it was the

easiest means of cooking and grease from

the pork was available.27

Frontier women also specialized in

makingjohnnycake, an especial-

ly popular article of food. This corn

bread was sometimes baked

upon a board called the

"johnnycake" board, a smooth board about

ten inches wide and two feet long.

Cornmeal was made into a thick

batter and molded into small cakes

called "dodgers," which were

placed on the board, set before the

fire, and baked into bread. Corn-

meal was the mainstay in the daily diet

of the frontier family be-

cause corn was easy to grow, and

therefore, plentiful.28

During the Indian wars of the early

1790s, the principal items of

25. Samuel P. Hildreth, "Manners

and Domestic Habits of the Frontier Inhabit-

ants, in the First Settlements of

Ohio," The Medical Counselor ( 12 January 1856), 34.

26. Buley, The Old Northwest, I,

210.

27. Joseph Barker, Recollections of

the First Settlement of Ohio (Marietta, 1958),

21-23, hereafter referred to as First

Settlement of Ohio; and R. E. Banta, The Ohio

Valley, Localized History Series (New York, 1966), 21.

28. Curtis, "Recollections of

Pioneer Life."

Women on the Ohio Frontier 67

food were Indian bread, pork, potatoes,

venison, bear meat, rac-

coons, opossums, squirrels and wild

turkeys. Fruits were popular,

when available; the settlers had to wait

on fruit such as apples and

peaches to grow from seed, so fruit was

scarce until the trees could

bear. In addition, great quantities of

pumpkins were dried and used

during the winter.29

Maintaining a sufficient food supply was

always a problem, and

thus frontier women were often hard

pressed to feed their families.

For example, unripe corn was gathered

and stored in the fall of

1789, but when eaten it caused sickness

and vomiting. To remedy

this situation, some corn was brought to

Marietta from western

Pennsylvania. But the Pennsylvania corn

was a mixed blessing, as

prices soared - corn quickly rose from

$.50 to $1.50 and $2.00 a

bushel. Because of the food shortage,

the year 1790 became known

as the "starving year." The

little children "cried for bread, and cried

in vain, for the hands of the sorrowing

mothers were empty, they

had nothing to satisfy the hunger of

those whose sufferings it was so

agonizing to see."30 There

were only a few cattle and hogs in the

entire community. Moreover, Indians had

killed or destroyed much

of the game and deer within twenty miles

of Marietta; and to make

matters worse, they often left the

carcasses of the animals in the

woods, thus attracting wolves. By

killing off game, the Indians

hoped to drive the settlers back east of

the Ohio River. They referred

to the prospect of "repossessing

their lands and recovering the good

hunting ground."31

The year 1790 was a real trial for these

pioneers. People shared

small quantities of milk with families

who had children, and only

the use of fish from the local streams

and rivers saved many poor

families from starving. The hungry

settlers gathered the shoots of

the pigeonberry and potato tops for

nourishment. Women resorted

to drinking sassafras or spice-bush tea

instead of young hyson (a

type of Chinese green tea) or fragrant

bohea (a high quality Chinese

black tea). They vowed that "if

they ever lived again to enjoy a

supply of wholesome food for their

children and selves, they would

never complain."32

The settlers struggled until 1791 when a

new harvest of beans,

corn, wheat, and potatoes alleviated

their plight. They had managed

to survive the hardships of the

"famine of 1790-the starving year,"

29. Stone, "From Rutland to

Marietta," 220.

30. Samuel P. Hildreth, Pioneer

History (Cincinnati, 1848), 265; and Cone. Rufus

Putnam, 113.

31. Barker, First Settlement of Ohio,

61.

32. Hildreth, Pioneer History, 265-66.

68 OHIO HISTORY

the most trying period on the Ohio

frontier, and women now looked

forward to the prospect of serving

better and more nourishing food

to their families.

Pioneers had to contend with a lack of

sanitation, few qualified

physicians, poor quality and

preservation of food, little medicine,

and a lack of knowledge concerning even

simple diseases. Early

newspapers usually did not report

illnesses or epidemics in their

own areas, fearing the bad news would

stifle promotions to sell land

and further settlement. Therefore, one

must rely on brief written

records for information concerning the

treatment of illnesses during

the early years in the Ohio-Muskingum

Valley. In 1809, Dr. Samuel

Hildreth, a leading physician and

historian, wrote a brief report

about various medical problems in

Marietta:

The diseases of this climate are

generally of the bilious class; asthmatic

cases are very rare, and those of the

spasmodic or nervous kinds, find a

quick relief in this country; rheumatism

is more common. Complaints of the

bowels are common, particularly to

strangers: of this class of diseases,

cholera infantum is the most common and

destructive.33

Although the doctors on the Ohio

frontier were males, women

often had to serve as physicians or

"dispensers of medicine and home

remedies" to their families. It was

their responsibility to care for

sick family members before a doctor

could be contacted. While

women accepted the responsibility of

many roles on the frontier,

certainly one of the most important was

that of "family healer."

Both men and women suffered from tension

and stress during the

early years of the Marietta settlement.

Until the end of the Indian

wars in 1795, the pioneers lived within

or close to one of the forts so

they could utilize it quickly for

protection. The cultivated fields

were usually within sight of the fort.

Weapons were kept nearby,

and guards were posted while men worked

in the fields. Women

lived with the constant danger of an

Indian attack. During this

period of warfare, they did not know

whether their husbands would

return unharmed from the field or their

children from work or play.

The frontier woman displayed tremendous

courage when faced with

tension and stress brought on by danger

to her family. For example,

in 1791, Dr. Nathan McIntosh was

appointed surgeon's mate to Fort

Frye, located north of Marietta on the

Muskingum River. The resi-

33. Samuel P. Hildreth, "A Concise

Description of Marietta, in the State of Ohio;

With an Enumeration of Some Vegetable

and Mineral Productions In Its Neighbor-

hood," Medical Repository, VI

(February, March, and April, 1809), 359.

Women on the Ohio Frontier 69

dents of Clarksburg, Virginia, were in

need of a permanent doctor

and sent for McIntosh. There were no

roads or public houses be-

tween Marietta and Clarksburg, so

McIntosh, his young wife Rhoda,

and their six-week-old baby camped in

the open at night. In order to

keep the baby from crying and attracting

nearby Indians, Rhoda

used a handkerchief doused with

paregoric to muffle its cries.34

The forts on the frontier offered

protection from Indians, but very

little privacy. The log houses or cabins

were built close to one

another and were all enclosed within the

outside walls of the fort.

Undoubtedly many women, who did not

leave the fort as often as

men, suffered from "cabin

fever," especially during the long cold

winter months. Furthermore, the living

conditions and lack of

sanitation were not conducive to good

mental or physical health.

Consequently, illness was prevalent and

death was frequent among

the early Marietta settlers.

Education and religion, frequently the

responsibility of women,

were extremely important to the New

Englanders who settled in

Marietta. Educational classes, with

teachers paid by parents and

the Ohio Company, were held within a

year after the arrival of the

first pioneers. Religious services were

conducted almost immediate-

ly by members of the Ohio Company. In

1788, Bathsheba Rouse

declined a lucrative marriage proposal

and instead chose to accom-

pany her parents on their long journey

from New Bedford, Mas-

sachusetts, to the wilderness community

of Marietta. She was twen-

ty-one when she began teaching school at

Belpre, downriver from

Marietta, during the summer of 1790. She

continued teaching for

several years and had the distinction of

being the first female

teacher in the Ohio Territory.35

Usually, only the younger children

attended these first frontier

schools, for older children were needed

to assist with clearing land,

farming, household chores, and caring

for the younger children.

Most early schools were held in one-room

log structures. The mother

of Cyrus Sears taught in such a school,

and he remembered that

experience:

The school house was a low

clapboard-covering cabin of round logs; on one

side a door, hung on wooden hinges and

fitted for ample ventilation; about

the center of each of its other sides, a

hole about two feet square, chopped

34. Edmund Cone Brush, "The Pioneer

Physicians of the Muskingum Valley,"

Ohio Archaelogical and Historical

Publications, III (1891), 245,

hereafter referred to

as "Pioneer Physicians."

35. Samuel P. Hildreth, Original

Contributions to the American Pioneer (Cincin-

nati, 1844), 125.

70 OHIO HISTORY

out, with cross of slats in the center,

having arms extending and fastened on

top, bottom and sides to support the

substitute for glass - newspapers

greased with what Pennsylvania Dutchmen

called "hog's tallow." An old-

fashioned ten plate stove stood in the

center of the room; all furniture,

furnishings and decorations were very

solid and substantial, made by

fathers for their children, with axes,

hand saws, and augers. She received

$1.50 per week of six days, and no

holidays, and all time lost made up.36

Homes were also utilized for teaching.

Regardless of where they

taught, women were instrumental in

molding the minds and charac-

ter of frontier children.

Women were also active in the religious

life of Marietta. For

example, Mary Bird Lake, a native of

London, England, and her

family arrived in Marietta from New York

in 1789. She was then

forty-seven years old and the mother of

eight children. Although she

was quite busy caring for her family,

she soon began teaching Bible

lessons to about twenty children each

Sunday afternoon; she con-

tinued to conduct these sessions in

Campus Martius throughout the

early 1790s.37 Religion, like

education, had always been at the core

of the New Englander's life, and it

continued to be important when

that same New Englander was transplanted

to Marietta. Women

composed over 50 percent of the

congregation when the Congrega-

tional Church of Marietta was formed on

December 6, 1796; there

were seventeen female and fifteen male

parishioners.38 The women

of the community actively saw to it that

religion was not neglected

in the new frontier settlement.

One of the favorite activities of both

women and men in Marietta

was the community supper. After long

days of work, they looked

forward to the prospect of a feast, good

conversation, and the shar-

ing of news from the East. The small group of settlers celebrated

July 4, 1788, with a large dinner and

the firing of cannons. In

August of that same year, the Ohio

Company had a supper in honor

of Governor Arthur St. Clair and the

officers of Fort Harmar, which

was located directly across the

Muskingum River from Marietta. Dr.

Manasseh Cutler, a participant in the

organization of the Ohio Com-

pany, attended and wrote that "we

had a handsome dinner with

much punch and wine. The governor and

the ladies from the garri-

son were very sociable."39

36. Sears, "Pioneer-Indian Days in

Ohio," 363.

37. Hildreth, Pioneer Settlers, 323-24.

38. Washington County, Ohio, 381.

39. Manasseh Cutler, "Extracts From

Journal," 19 August 1788, Manuscript Col-

lection 210, Ohio Historical Society.

|

Women on the Ohio Frontier 71 |

|

|

|

As time passed and some families became affluent, large parties and balls were held, social events especially pleasurable to the ladies. Dr. Increase Mathers, Rufus Putnam's nephew from New Braintree, Massachusetts, visited Marietta in 1798 and was invited to a ball at the home of Colonel Israel Putnam in Belpre. Mathers enjoyed the affair and recorded the following entry in his diary on August 31: "We had a large collection of ladies, some from Marietta, and the Island, who made a brilliant appearance. Spent the evening very agreeably."40 Everything considered, Mather's enjoyment was probably exceeded by that of the ladies.

40. Brush, "Pioneer Physicians," 252. |

72 OHIO HISTORY

Weddings, always occasions of feasting

and pleasure, also pro-

vided women with a welcomed relief from

the daily hardships of

frontier life. Generally, neighbors for

miles around were invited to

the festivities. General Rufus Putnam,

Judge of the Court of Com-

mon Pleas of Washington County,

performed the first wedding cere-

mony in Marietta on February 6, 1789,

marrying Rowena Tupper to

Winthrop Sargent, the secretary of the

territory. A wedding cere-

mony was usually followed by an

elaborate meal of venison, roast

turkey or bear meat. Afterwards, young

people danced throughout

the night. The feasting, drinking, and

dancing sometimes continued

for several days.41

The people in these small Ohio frontier

communities often com-

bined work and pleasure. Corn-huskings

and "apple-cuttings" were

always quite popular with both women and

men. In corn-husking,

corn (with husks still on) were heaped

in two large piles before the

arrival of neighbors. Captains and teams

of men were chosen, and

the team which finished husking its pile

of corn first was the win-

ner. Dr. Daniel Drake described one of

these huskings, saying, "I

have never seen a more anxious rivalry,

nor a fiercer struggle."

Whiskey was plentiful and the women

always served a supper after

the work and fun were over. At

"apple-cuttings" or "apple-parings,"

the settlers assembled to peel large

quantities of apples for drying or

for making apple butter. After the

apples were peeled, everyone

danced and "frolicked." The

"Virginia Reel" was a favorite dance of

both young and old at such gatherings.42

The quilting bee was both a source of

enjoyment and local in-

formation for women on the Ohio

frontier. Quilting parties usually

met in homes, churches, or town halls,

where the women of a com-

munity created a beautiful bed covering

and also exchanged neigh-

borhood news or gossip.

Although girls and young women were

generally kept busy assist-

ing their mothers with domestic tasks,

one young lady, Louisa St.

Clair, the daughter of the governor of

the Northwest Territory, was

reknown for her athletic abilities. A

fine equestrian, Miss St. Clair

was often seen riding in the fields

around Campus Martius. She was

usually triumphant in walking or running

races. Furthermore, she

was an expert ice skater and could shoot

a rifle with the accuracy of

a skilled woodsman. Louisa deservedly

was remembered as one of

41. Washington County, Ohio, 358.

42. William Henry Venable, Footprints

of the Pioneers In The Ohio Valley (Cincin-

nati, 1888), 118-21.

Women on the Ohio Frontier 73

the most distinguished and athletic

young women on the early Ohio

frontier.43

As previously noted, pioneer women did

not have time to ponder

over "the role of the female on the

Ohio frontier." There was so little

time and so much work. To a great

extent, the adult life of these

women consisted of marriage, maternity,

and mortality. Women

often married while still quite young,

sometimes as early as four-

teen, and were expected to help their

husbands build a new life in

this untamed land. Moreover, childbirth

hardly interrupted their

work routine, and the frequency of

childbirth and difficult deliveries

exacted a dreadful toll: women aged

rapidly by the time they turned

thirty, and were old by forty, if still

alive. Women, by necessity,

accepted the roles of wife, mother,

housekeeper, artisan, counselor,

educator, religious instructor, weaver

and tailor, and physician.

Among other duties, they were

responsible for cooking and baking,

preparing flax, spinning and weaving,

making clothes, planting and

caring for small kitchen gardens, making

soap and candles, washing

and caring for clothing and bedding,

cleaning the houses, and rear-

ing large families. The frontier women,

as exemplified by those at

early Marietta, played a major role in

the advancement of the Ohio

frontier.

43. Ellet, The Pioneer Women of the West, 178-79.