Ohio History Journal

TERRY A. BARNHART

In Search of the Mound Builders:

The State Archaeological Association

of Ohio, 1875-1885

If the State Archaeological Association

of Ohio is at all remembered today

it is as the forerunner of the Ohio

State Archaeological and Historical

Society. That organization emerged from

the wreckage of the earlier state ar-

chaeological association on March the

12th and 13th, 1885, and has been

known as the Ohio Historical Society

since 1954. The significance of Ohio's

first state archaeological association

is, however, far greater than its obscure

history might imply. The association mounted the award winning

"Antiquities of Ohio" exhibit

at the 1876 Centennial Exposition in

Philadelphia, sponsored the

establishment of the first and equally obscure

American Anthropological Association,

and conducted an investigation into

the authenticity and supposed meaning of

the Grave Creek stone that remains

a model of critical inquiry. Indeed, the

ardent and loosely-affiliated members

of the Ohio Association were directly

involved in the leading problems and

controversies that agitated the emerging

anthropological community of the

late nineteenth century. Although the

importance of amateur societies in the

history of American archaeology has been

noted,l the aims and activities of

the State Archaeological Association of

Ohio have been largely forgotten.

The Origin: Brinkerhoff and Peet

The idea of a state archaeological

association originated with Roeliff

Brinkerhoff of Mansfield and the

Reverend Steven Denison Peet of Ashtabula.

Brinkerhoff and Peet first met during a

state conference of Congregationalists

held at Mansfield in the summer of 1875,

where they discussed their mutual

interests in archaeology and the

unresolved questions concerning the origin

and identity of the Mound Builders.2

The task of surveying and exploring

Terry A. Barnhart is Associate Professor

of history at Eastern Illinois University.

1. See, for example, Marshall McKusick, The

Davenport Conspiracy Revisited (Ames,

Iowa, 1990) and The Davenport

Conspiracy (Iowa City, 1970), which examine the role played

by the Davenport Academy of Natural

Sciences in the controversy surrounding the authenticity

and meaning of the Davenport tablets.

2. Roeliff Brinkerhoff, Recollections

of a Lifetime (Cincinnati, 1900), 230-31.

126 OHIO HISTORY

Ohio's numerous mounds and earthworks

had earlier begun through the field-

work of Caleb Atwater, James McBride,

Charles Whittlesey, and the investi-

gations of Ephraim George Squier and

Edwin Hamilton Davis, but had re-

ceived only fragmentary attention since

the 1850s. Each year more sites were

lost to the farmer's plow and urban

growth, while the mindless diggings of

relic hunters destroyed much valuable

information that could be preserved

through systematic investigations.

Archaeological collections were also leav-

ing Ohio, either by purchase or through

the explorations of individuals and

organizations from outside the state.

Brinkerhoff's enthusiasm for archaeology

was cultivated amidst a public life

crowded with other interests. At various

times a lawyer, journalist, and

banker, he was politically one of the

most influential figures in the state.

Born at Owasco, New York, June 28, 1828,

he was educated in local district

schools and at the academies of Auburn

and Homer, New York. After early

experiences as a school teacher and

tutor in New York and Tennessee, he came

to Mansfield in 1850 to study law and

was admitted to the bar in December of

1851. His interest in archaeology

stemmed from his study of local history,

which he chronicled as editor and

proprietor of the Mansfield Herald from

1855 to 1859. He continued that

avocation as the founder and secretary of the

first Richland County Historical Society

in 1869, contributing additional his-

torical sketches to the Ohio Liberal in

1873.3 Brinkerhoff

recognized the

long-neglected need to systematically

survey and map Ohio's prehistoric

earthworks, and the advantages to be

derived from combining private archaeo-

logical collections into a state museum

at Columbus. Those interests and

connections with the press and the Ohio

legislature made Brinkerhoff an effec-

tive force in the movement to establish

a state archaeological association.

His partner in that enterprise came to

the study of archaeology along a

much different path. Peet was born in

Euclid, Ohio, December 2, 1831, and

spent most of his early life preparing

for the ministry. He graduated from

Beloit College in 1851, attended Yale

Divinity School from 1851 to 1853,

and graduated from the Andover

Theological Seminary in 1854. His interest

in American Indians and prehistoric

remains first arose as a child while ac-

companying his father on missionary

tours through Wisconsin, a state rich

with effigy mounds and home to a number

of American Indian communities.

But it was during Peet's theological

studies that his future interest in archae-

ology became more clearly defined. His

reading of ancient history and the

Bible instilled a life-long enthusiasm

for the study of Egyptian, Babylonian,

3.

Brinkerhoff, Recollections of a Lifetime, passim; Elbert Jay Benton, "Roeliff

Brinkerhoff," Dictionary of

American Biography vol. 3 (New York, 1929), 49-50; A. J.

Baughman, "General Roeliff

Brinkerhoff, History of Richland County[,] Ohio from 1808-1908

Volume 1 (Chicago, 1908), 487-91; A. A.

Graham, History of Richland County, Ohio

(Mansfield. 1880), [i- iii].

|

In Search of the Mound Builders 127 |

|

Grecian, and Roman antiquities. It was but a short step from the study of Biblical archaeology to the archaeological remains of Ohio and Wisconsin, states in which he was a frequent resident and traveler. After becoming pastor of the Congregationalist church at Ashtabula, Ohio, in 1873, he became a se- rious student of local archaeology.4 Brinkerhoff, the practical man of means and influence, and Peet, the Christian scholar and romantic antiquarian, were a seemingly unlikely but effective team.

4. Warren King Moorehead, "Stephen Denison Peet, Dictionary of American Biography vol. 14 (New York, 1934), 392-93; E. O. Randall, "Stephen D. Peet," Ohio Archaeological and Historical Publications, 26 (April, 1917), 299-301; Samuel Utley, "Stephen Denison Peet," Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society, 26 n.s., Part 1 (April, 1916), 16-17; Stephen D. Peet, "Reminiscences of Early Green Bay, Wisconsin," The Old Northwest Genealogical Quarterly, 7 (July, 1904), 160-64; and William W. Williams, History of Ashtabula County, [Ohio] (Philadelphia, 1878), 139. Regarding Peet's knowledge of local archaeology, see Rev. S. D. Peet, "The Mound-Builders," History of Astabula County, 16-20, and his "A Double- Walled Earthwork in Ashtabula County, Ohio," Smithsonian Annual Report, 1876 (Washington, D.C., 1877), 443-44. |

128 OHIO

HISTORY

With their plan of action agreed upon,

Brinkerhoff and Peet sought to re-

cruit all students of Ohio archaeology

to the cause. They first enlisted the as-

sistance of James Wharton of Mansfield

and Portsmouth, a newspaper man

and former resident of Wheeling, West

Virginia. Wharton had contracted the

antiquarian malady years before and

fully shared Brinkerhoff and Peet's interest

in bringing Ohio's prehistoric remains

under further study. Over the follow-

ing months, they recruited Norton

Strange Townsend of Columbus, Isaac

Smucker of Newark, and Manning Ferguson

Force and Joseph Cox of

Cincinnati. Newspaper notices and

printed circulars were issued calling for a

state archaeological convention at

Mansfield on September 1, 1875.5 Peet

reported that he was receiving

encouragement from all sides: "The only cold

water is that from Lake Erie at the

hands of Col. Whittlesey."6

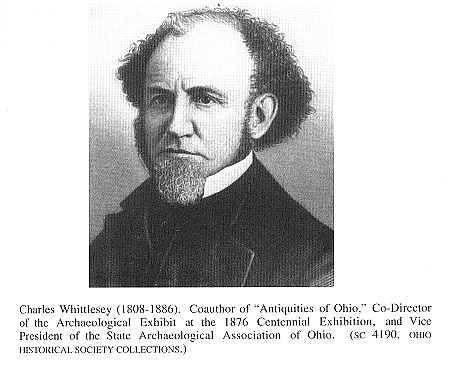

Charles Whittlesey of Cleveland, Ohio, an

officer of the Western Reserve

and Northern Ohio Historical Society,

began surveying prehistoric earthworks

as topographic engineer on the first

Ohio Geological Survey in 1837. He had

made "home archaeology" a

province of study since that time, having pub-

lished several accounts on the subject

as Tracts of the Western Reserve and

Northern Ohio Historical Society. His seeming coolness toward the idea of a

state archaeological society was not for

want of interest or passion, but re-

flected his own unsuccessful efforts at

interesting the Ohio legislature in fund-

ing an archaeological survey as part of

the state geological survey.

Systematic archaeological investigations

of the kind proposed by Brinkerhoff

and Wharton required "money"

above all else. Experience had taught him that

this was the first element of success.

The proposed society "can do much by

mere labor and enthusiasm, but a

thorough archaeological investigation re-

quires cash." He wrote not to

discourage the movement to establish a state

archaeological society, but to advise

that "raising a fund is the first object of

consideration." Annual memberships

and volunteerism alone would not en-

sure success.7 Notwithstanding

those sober-minded reservations, Whittlesey

joined the movement to establish a state

association and would become one

its most active if independent-minded

members.

5. Roeliff Brinkerhoff and James E.

Wharton, Printed Circular, Mansfield, Ohio, July 23,

1875, The Norton Strange Townsend

Papers, VFM 2168, Archives-Library Division, the Ohio

Historical Society. Hereafter, Townsend

Papers, OHS. Brinkerhoff and Wharton's telegraph

notices appeared in several papers. See,

for instance, "State Archaeological Society," Ohio

State Journal, July 15, 1875, [1], no pagination.

6. Peet to [Brinkerhoff], Ashtabula,

July 29, 1875, Townsend Papers, OHS. Brinkerhoff

also received encouragement from several

quarters of the state. See Brinkerhoff to Wharton,

Mansfield, Ohio, July 23, 1875; Joseph

Cox to Brinkerhoff and Wharton, Cincinnati, July 30,

1875; A. Haines, Sr., to Brinkerhoff,

Eaton, Ohio, August 12, 1875; and George Perkins to

Brinkerhoff, Chillicothe, August 30,

1875, Townsend Papers, OHS.

7. Charles Whittlesey to Brinkerhoff and

Wharton, Cleveland, Ohio, July 26, 1875,

Townsend Papers, OHS.

|

In Search of the Mound Builders 129 |

|

|

|

Brinkerhoff and Wharton described the work that was to be done by the pro- posed society, revealing some of the assumptions and motives behind their ef- forts. Ohio presented a rich field for archaeological investigations, providing a copious store of "the relics of a race anterior and more cultivated than that found here during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries." Almost every county in the state had one or more persons interested in the subject and who boasted cabinets or "museums" of local archaeology. But no systematic and combined effort had been made "to elicit the truth, and settle inquiring minds upon a well sustained theory of who they were[,] or when or how long they inhabited the country we now occupy." It was a matter of regret that while great patronage was being bestowed upon archaeological investigations in Europe, government and private support of such efforts in the United States paled by comparison. While Ohio did nothing, associations in other states were gathering fine archaeological cabinets "for the instruction of their peo- ple, and the admiration of those who come after us."8

8. Roeliff Brinkerhoff and James E. Wharton, Printed Circular, Mansfield, Ohio, July 23, 1875, Townsend Papers, OHS. |

130 OHIO

HISTORY

The call for action was well met, as

kindred spirits gathered themselves at

Mansfield into the Ohio State

Archaeological Convention. After two days of

deliberations, the reading of papers,

and the mandatory exhibition of "mound

relics," the forty-nine registered

delegates enthusiastically established the State

Archaeological Association of Ohio.9 Brinkerhoff was elected President,

Norton Strange Townsend General

Secretary, Martin Hensel of Columbus

Treasurer, and John Hancock Klippart of

Columbus the Librarian and

Depository. Vice Presidents included Charles Whittlesey of Cleveland,

Manning Ferguson Force of Cincinnati,

Giles Samuel Booth Hempstead of

Portsmouth, John Strong Newberry of

Cleveland, and Ebenezer Baldwin

Andrews of Lancaster. Peet was elected a

Trustee, as were Isaac Smucker of

Newark, Charles Candee Baldwin of

Cleveland, Thomas Waller Kinney of

Portsmouth, William B. Sloan of Port

Clinton, Edward Orton of Columbus,

and Matthew Canfield Read of Hudson.

The mission of the State Archaeological

Association of Ohio was a daunt-

ing one. Its founders sought to promote

archaeological knowledge through

systematic surveys, explorations, and a

permanent state museum at

Columbus. Norton Strange Townsend, as

General Secretary, solicited funds

for an annual publication of

transactions, and sought the cooperation of all in-

terested parties in obtaining the

donation of artifacts, sketches, surveys, and

photographs to the association's

Librarian and Depository at the Ohio

Statehouse. The library and museum were

to be permanently located at

Columbus, and donations to them were requested

throughout 1875 and 1876.

Somewhat naively it was hoped that

"This will make a nucleus [of a mu-

seum] until the association can select

its location and erect its own build-

ings."10 The

constitution of the Ohio Association provided that local scien-

tific and historical societies having

archaeological collections could become

auxiliaries. It was particularly

important that individuals and societies furnish

the association with accounts of the

circumstances surrounding the recovery

of archaeological materials in their

localities. "Our design is to form auxil-

iary societies in every county of the

state, or to have collections and corre-

9. D. H. Moore, et al., "Call

for the Convention," Mansfield, Ohio, August 5, 1875" in

Minutes of the Ohio State

Archaeological Convention Held in Mansfield, O., September 1st &

2nd, 1875 (Columbus, 1875), 3-4.

10. Norton Strange Townsend, Printed

Circular, Columbus, Ohio, September 4, 1875, Roeliff

Brinkerhoff Papers, MSS 31,

Archives-Library Division, Ohio Historical Society. Hereafter,

Brinkerhoff Papers, OHS; Minutes of

the Ohio State Archaeological Convention, 3-4, and

Roeliff Brinkerhoff and James E.

Wharton, Printed Circular, Mansfield, Ohio, July 23, 1875,

Townsend Papers, OHS. A copy of the

Brinkerhoff-Wharton Circular of July 23, 1875, is also

found in the Brinkerhoff Papers, OHS.

Article 2 of the Constitution of the State Archaeological

Association of Ohio states that

"The object of the Association shall be to promote investigation

of the mounds and earthworks of the

State, to collect facts, descriptions, relics, and other evi-

dences of the pre-historic races, and to

awaken an interest in the general subject of

Archaeology." Minutes of the Ohio

State Archaeological Convention, 32.

In Search of the Mound Builders 131

spondents in every county, so that

nothing shall be destroyed without our

knowledge of it; hundreds are

disappearing of which there is no record."1l

It is noteworthy that the State

Archaeological Association of Ohio and sim-

ilar societies in Indiana and Tennessee

were all established in 1875. Their ap-

pearance in that year can partly be

explained by the approach of the 1876

Centennial Exposition at Philadelphia,

but more practically by the recognized

need for the establishment of state

archaeological museums. The editors of

the American Naturalist hoped

that the establishment of those organizations

would foster careful research, and aid

in the preservation of earthworks in the

Midwest and the South.12 Those

objectives were as laudable as they were

unwieldy. The surveying of local works,

the documentation of excavations

and artifacts, and the classification of

archaeological materials and sites re-

quired concerted action, state and local

cooperation, and sources of funding on

a scale that had not yet been seen.

Nonetheless, the founders of the Ohio

Association were committed to seeing

those studies carried forward. Their

purpose, Brinkerhoff noted, was

"far nobler and higher than the mere gather-

ing of relics. Relics are only the

letters of the archaeologist's alphabet, but

nevertheless they are the indispensable

beginning of all archaeological knowl-

edge." It was urgent that the

"archaeological harvest" begin as soon as possi-

ble. "Let us gather the grain into

storehouses before it is utterly destroyed by

the tramping hoofs of modern

utilitarianism."13

The delegates at the Mansfield

convention left with "flattering prospects"

for the organization's future growth and

usefulness. Brinkerhoff hoped that

the number, location, and character of

Ohio's mounds and earthworks could

soon be determined with the assistance

of local representatives in various

counties.14 An unidentified observer in

the press, probably Brinkerhoff or

Peet, saw a bright future for the infant

science of archaeology in Ohio.

Heretofore archaeology has been simply

an addendum to something else, and has

been crowded into a corner in some

philosophical, historical, or scientific associ-

ation. The archaeologists of Ohio have

concluded that this state of affairs should

not continue any longer. They believe

that archaeology is the highest department

of scientific inquiry, and that it

should lead and not follow; and hence they have

11. Peet to "Dear Madam,"

Ashtabula, n.d. [1875], Stephen Dension Peet Papers, Beloit

College Archives. Hereafter, Peet

Papers, BCA. Article 6 of the Constitution of the State

Archaeological Association of Ohio

provided that "All Associations within the state having an

archaeological department or collection,

may be auxiliaries of this [association]; provided they

furnish a list of their specimens, and a

copy of their publications." Minutes of the Ohio State

Archaeological Convention, 32.

12. "Notes," American

Naturalist, 9 (November, 1875),624.

13. Brinkerhoff, "Address of

Welcome," Minutes of Ohio State Archaeological Convention,

10-11.

14. Brinkerhoff to Townsend, Mansfield,

Ohio, September 21, 1875, Townsend Papers,

OHS, and Minutes of the Ohio State

Archaeological Convention, 42.

132 OHIO

HISTORY

established a State Association, which

is to be devoted solely to archaeological

investigations. The wisdom of this

movement was fully demonstrated by its aus-

picious beginnings.15

Expectations ran high during the heady

days following the Mansfield conven-

tion.

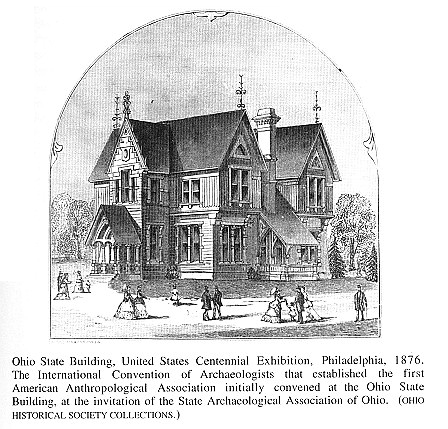

The United States Centennial

Exposition in Philadelphia

The first official task of the Ohio

Association was to arrange an archaeolog-

ical exhibit at the forthcoming United

States Centennial Exposition in

Philadelphia. Receiving an appropriation of $2,500 from the

Ohio

Centennial Commission for this purpose,

the Association appointed a

Centennial Committee chaired by Peet. It

was Charles Whittlesey, Matthew

Canfield Read, and William B. Sloan,

however, who undertook the tedious

work of obtaining loans or donations of

select artifacts from archaeological

collections throughout the state. Most

of that work fell to the able hands of

Read and Whittlesey, who canvassed the

contents of private cabinets and those

found in historical societies and

colleges. They solicited descriptions

of

stone, flint, and copper artifacts,

asking contributors to distinguish between

those found within mounds and those

found on the surface. Those belonging

to "the era of the mound

builders" were separated from "Indian Antiquities" of

a presumably later or indeterminate

date. After only two months of such

work, the committee forwarded some 5,316

artifacts to Philadelphia. The se-

lections represented forty-five private

collections, appreciatively styled as

"museums of American

antiquities."16 Brinkerhoff noted that the exhibit was

certain to confer recognition and status

on the new association at Philadelphia

and "give us character at home."17

15. "The Future of

Archaeology." Unidentified Press Clipping, [September, 1875], Peet

Papers, BCA. This statement was probably

written by Brinkerhoff, who made similar remarks

in an address at the 1876 Centennial

Exposition in Philadelphia. See

"Archaeological,"

Philadelphia Inquirer, September 5, 1876, 2.

16. R. M. Buckland to Norton Strange

Townsend, Fremont, Ohio, September 12, 1876,

Townsend Papers, OHS,

"Archaeological Exhibit," Final Report of the Ohio State Board of

Centennial Managers to the General

Assembly of the State of Ohio (Columbus,

1877), 15-16. A

list of exhibitors at Philadelphia is

found on pages 30-32. The complete report on the associa-

tion's exhibit at the 1876 Centennial

Exposition in Philadelphia is contained in M. C. Read and

Charles Whittlesey, "Antiquities of

Ohio: Report of the Committee of the State Archaeological

Society," Ibid., 81-141.

Whittlesey's leading role in organizing the archaeological exhibit is

documented in the Charles Whittlesey

Papers, MSS 2872, Container 3, Folder 5. Western

Reserve Historical Society, Cleveland,

Ohio.

17. Brinkerhoff to John Hancock

Klippart, Mansfield, Ohio, March 31, 1876, John Hancock

Klippart Papers, MSS 143,

Archives-Library Division, The Ohio Historical Society.

Brinkerhoff proposed that the Ohio

Association purchase some of the private collections ex-

hibited at Philadelphia as the nucleus

of its proposed state museum which, he believed, would

encourage the donation of others.

In Search of the Mound Builders 133

As illustrations of the arts and

industries of pre-Columbian America, the

archaeological exhibits at the 1876

Centennial Exposition were among its

most popular features.l8 Indeed,

that aspect of the Philadelphia Exposition

deserves more attention from historians

than it has received. Comprised of

collections from several states and the

Smithsonian Institution, the

Centennial Exposition was the largest

display of American antiquities that

had yet been presented to the public.

The assemblage offered an unique op-

portunity for the classification and

orderly comparison of collections from

throughout the United States. The 1876

Centennial anticipated the impetus

given to archaeological investigations

by the world expositions held later in

the nineteenth and early twentieth

centuries. Although known for its celebra-

tion of American industrial prowess and

ingenuity, the Philadelphia

Exposition provided curious visitors and

the American scientific community

an opportunity to reflect on the remote

recesses of the American past and how

imperfectly it was known. The archaeological exhibits by the Ohio

Association and the Smithsonian

Institution received particular attention.

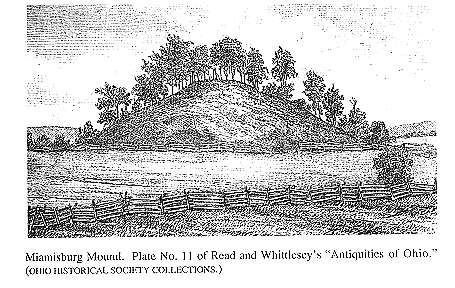

The "Antiquities of Ohio"

exhibit at Philadelphia was located in the

Mineral Annex of the Main Exhibition

Building, reflecting the developmental

relationship between geology and

archaeology in the nineteenth century. It

consisted of sixteen cases of artifacts,

charts illustrating Ohio earth and

stoneworks, facsimiles of petroglyphs,

and Charles Whittlesey's imposing

"Historical and Archaeological Map

of Ohio." The map located the state's

principal mounds and earthworks, sites

of historic Indian villages, and the

routes of early Euro-American

explorations and military expeditions.19 The

exhibit was greatly admired for the

variety and representativeness of the mate-

rials displayed. Ornaments and

implements of stone, flint, and copper were

grouped separately, as were articles of

bone, pottery, and sculptured stone

pipes. The exhibit, judged second in

quality only to that of the Smithsonian,

was described as a "labor of love,

guided by discriminative intelligence."20

The stone implements received the

particular notice of Charles Conrad

Abbott, whose studies of Paleolithic

implements found in the glacial drift of

18. M. C. Read, "Ohio

Archaeology," Tracts of the Western Reserve and Northern Ohio

Historical Society, no. 73 [1888], 8.

See also Emile Guimet, "The Stone Age at the

Philadelphia Exhibition," 30th

Paper, Congress international des Americanistes, compte-rendu

de la seconde session,

Luxembourg-1877 I(Luxembourg and

Paris, 1878).

19. Charles Whittlesey and Thomas

Mathew, "Historical and Archaeological Map of Ohio,"

Map 771, [1910], Geog. 1051,

Archives-Library Division, The Ohio Historical Society. This

mural map, painted on textile, was

compiled by Whittlesey and prepared at the Ohio

Agricultural and Mechanical College

(later The Ohio State University) by Mathew. The im-

posing map is based on Whittlesey's

earlier "Historical Map of the State of Ohio," published in

H. F. Walling and 0. W. Gray's New

Topographical Atlas of the State of Ohio (Cincinnati,

1872), 17.

20. Final Report of the Ohio State

Board of Centennial Managers, 16; "Antiquities of Ohio,"

Unidentified Press Clipping [October

1876], Peet Papers, BCA; and Brinkerhoff, Recollections

of a Lifetime, 230.

134 OHIO

HISTORY

New Jersey were pushing back the

chronology of man in America. Abbott

commended the exhibit for the

convenience of its arrangement, which was

"highly creditable" to those

in charge. The lithic materials gave visitors "an

excellent idea of the proficiency in

flint-chipping attained by the aboriginal

peoples of the State." His only

criticism was to ask whether it would not

have been better to separate the

"Indian relics" found on the surface from ma-

terials referable to the Mound Builders.

It was in the series of stone pipes, a

particularly attractive feature of the

display, that the "commingling of Indian

and mound-builders' relics" was

most noticeable.21

The International Convention of

Archaeologists at Philadelphia

Equally successful was the Ohio

Association's role in convening an

International Convention of

Archaeologists at Philadelphia, and the estab-

lishment of the first American

Anthropological Association (not to be con-

fused with the present AAA established

in 1902). Among the most signifi-

cant acts of the Ohio State

Archaeological Convention at Mansfield had been

the adoption of Peet's resolution calling

for an international archaeological

convention during the centennial

observance at Philadelphia. The express

purpose of the convention would be the

formation of "an Archaeological

Congress of America."22

A committee consisting of Peet, Matthew Canfield

Read, William B. Sloan of Port Clinton,

Norton Strange Townsend of

Columbus, and Archibald Alexander Edward

Taylor, president of Wooster

College, issued a circular announcing

the Ohio Association's sponsorship of

an International Convention of

Archaeologists at Philadelphia.23

The "Ohio Committee" saw the

centennial observance as an appropriate

time to reflect upon the achievements of

America's prehistoric inhabitants,

and the need to preserve the fragile

traces of their existence. Not only should

the mounds and earthworks be preserved,

but steps should be taken so that ar-

tifacts were brought under proper study

through the establishment of state ar-

chaeological societies and museums.

There was further need for a journal that

21. Charles Conrad Abbott, "Stone

Implements from Ohio at the Philadelphia Exposition,"

American Naturalist, 10 (August, 1876), 495-96.

22. The idea of calling a national

convention of archaeologists at the 1876 Centennial

Exposition in Philadelphia and the

formation of an "Archaeological Congress of America" is

clearly stated in Peet's resolutions at

Mansfield. See Minutes of the Ohio State Archaeological

Convention, 36, and Peet to "Dear Madam," Ashtabula, n.d.

[1875] Peet Papers, BCA.

23. "Archaeological Convention,

1776-1876," Printed Circular, Brinkerhoff Papers, OHS;

"To the Ethnologists,

Archaeologists, and Philologists of America, Printed Circular," n.p., n.d.

[1876] Brinkerhoff Papers, OHS; and

"The Future of Archaeology," Unidentified Press

Clipping, [September 1875], Peet Papers,

BCA; "Scientific News," American Naturalist, 10

(August, 1876), 505-06. Arrangements

were made for members of the Subsection of

Anthropology in the American Association

for the Advancement of Science to attend the

Archaeological Convention at

Philadelphia.

|

In Search of the Mound Builders 135 |

|

|

|

would promote the study of American archaeology and ethnology through ex- changes of information and by disseminating the results of original investiga- tions.24 The call for the convention was supported by Frederic Ward Putnam, curator of archaeology at Harvard's Peabody Museum; Spencer Fullerton Baird and Charles Rau of the Smithsonian Institution; Charles Conrad Abbott of Trenton, New Jersey; Daniel Garrison Brinton of Philadelphia; Samuel Stedman Haldeman of Chickies, Pennsylvania; Charles Colcock Jones of New York; and the venerable Charles Whittlesey of Cleveland.25 Such en- dorsements were as impressive as they were effective.

24. Stephen D. Peet. William B. Sloan, N. S. Townsend, A. A. E. Taylor, and M. C. Read, Untitled Printed Circular, Ashtabula, Ohio, May 10, 1876, "Committee of the State Archaeological Association of Ohio," Peet Papers, BCA. 25. "Archaeological Convention, 1776-1876," Printed Circular, Brinkerhoff Papers, OHS. |

136 OHIO

HISTORY

The convention was called to order at

Philadelphia and chaired by

Brinkerhoff in the Ohio State Building

on September 4, 1876. The partici-

pants received communications of support

from the International Congress of

Americanists, the Geographical Society

of Portugal, and from supporters

throughout the United States and Canada.

Opening remarks were made by

Allessandro Castellani of Rome, a scholar

of Greek and Etruscan art, and by

Dr. Heinrich Frauberger of the Museum of

Industrial Art at Brunn, Austria.

Papers were read on "The Myths and

Myth Makers of the Far West" by John

Wesley Powell of the U.S. Geological

Survey, "Paleolithic Remains in New

Jersey" by Charles Conrad Abbott

and Frederic Ward Putnam, "Ancient

Earthworks of the Mississippi

Valley" by Dr. Montroville Wilson Dickeson,

"Antiquities of the Florida

Tribes" by Charles Colcock Jones, Jr., and Peet's

contributions on "The Archaeology of

America and Europe Compared" and

"Sources of Information Concerning

the PreHistoric Races of America."26

The American Anthropological

Association and the Permanent

Subsection of Anthropology of the

American Association for the

Advancement of Science

At the conclusion of the convention,

"a permanent organization" was estab-

lished named the American

Anthropological Association. Its object was to

bring together all who were interested

in the study of American archaeology

and ethnology. Charles Colcock Jones,

Jr., was elected president of the new

entity, Whittlesey and Brinkerhoff vice

presidents, Peet corresponding secre-

tary, and Read the assistant secretary.

The existence of this short-lived orga-

nization is little known.27 The

cause of its demise was competition with the

26. Stephen D. Peet, "American

Anthropological Association," Printed Circular, Ashtabula,

Ohio, October 1, 1876, Brinkerhoff

Papers, OHS. The same circular is present in the Peet

Papers, BCA. "American

Anthropological Association," Printed "Admission Ticket" to the

"Convention at [the] Ohio Building,

International Exhibition, Thursday, September 7th, at 8

O'Clock, P.M. Entrance at Gate 55,"

Peet Papers, BCA; Stephen D. Peet, Printed Circular,

"American Antiquities,"

Ashtabula, Ohio, November 2, 1876, Peet Papers, BCA; and Otis T.

Mason, "Anthropological News,"

American Naturalist, (December, 1876), 750. Peet's paper

on the "The Archaeology of America

and Europe Compared" was also given at the 25th an-

nual meeting of the American Association

for the Advancement of Science, held at Buffalo,

August 23-30, 1876. "Proceedings of Societies-The American

Association for the

Advancement of

Science-Anthropology," American Naturalist, 10 (October 1876), 639.

His

paper on "The Sources of

Information as to the Prehistoric Condition of America" was pub-

lished in the American Antiquarian, 2

(July-September, 1879), 33-48.

27.

See Franklin 0. Loveland, "Stephen Peet (1831-1914) and the First

American

Anthropological Association," a

paper presented before the American Anthropological

Association at Cincinnati, Ohio,

November 30, 1979. A copy of this paper is among the Peet

Papers, BCA. Previous notices of the

first AAA appear in Patricia Lyon, "Anthropological

Activity in the United States,

1865-1879," Kroeber Anthropoligical Society Papers, 40 (1969),

8-37, and George Stocking, "The

First American Anthropological Association," History of

Anthropology Newsletter, 3 (1976), 7-10.

In Search of the Mound Builders 137

newly-organized Permanent Subsection of

Anthropology within the American

Association for the Advancement of

Science. The Subsection of

Anthropology was organized by Lewis

Henry Morgan and Frederic Ward

Putnam at the Detroit meeting of the

AAAS in 1875, and first convened at

Buffalo, New York, August 23, 1876. The

committee charged with organiz-

ing the Subsection, chaired by Morgan,

sought to make the annual meetings

of the AAAS the forum for the

presentation of ethnological, archaeological,

and philological research.28 Putnam

shared the views of Otis Tufton Mason,

an anthropologist at Columbian College

in Washington, D.C., who saw the

annual meetings of the AAAS as the most

suitable venue for American an-

thropologists to gather and share

research. Those sessions should be held,

Mason noted, "not to the

disparagement of local and State societies, but as a

supplementary means of better acquaintance

among workers in all parts of the

country."29

That goal left little room for a rival

national organization, especially one

sponsored and led by a state

archaeological association. Even Peet was uncer-

tain as to how the American

Anthropological Association could be launched

in the face of competition with the

AAAS's Subsection of Anthropology.

Both he and Brinkerhoff were determined

to keep the AAA independent of the

Subsection, yet needed its members to

attend and give papers at the meetings

of the AAA if it was truly to be a

national and an effective organization.

Predictably, Brinkerhoff's motion that

the first annual meeting of the AAA be

held at Newark, Ohio, in conjunction

with that of the Ohio Association, gave

rise to what the Philadelphia

Inquirer reported to be "an animated discus-

sion."30 Frederic Ward

Putnam wanted the meeting to be held at Nashville,

in association with the annual meeting

of the AAAS. Such arrangements

would better ensure the publication of

papers and addresses, which would be

"a dangerous burden on a new and

isolated society."31 Charles Whittlesey and

John Wesley Powell, also members of the

AAAS, concurred in that opinion.

Most members of the Ohio Association

rejected that suggestion. They

looked upon the AAA, understandably if

provincially, as their own creation

and sought to protect it from the

perceived encroachments of the enthroned an-

thropological establishment. Brinkerhoff

and William B. Sloan of Port

Clinton, Ohio, were joined by Samuel

Stedman Haldeman of Chickies,

28. Lewis Henry Morgan, et al. "To

the Ethnologists, Archaeologists, and Philologists of

America," Printed Circular, n.p.,

n.d. [1876], Brinkerhoff Papers, OHS. Whittlesey and

Townsend were among those whose names

appear on this circular. "Notes," American

Naturalist, 9 (June, 1875), 380; "Notes," Ibid., 9

(September, 1875): 525, and Otis T. Mason,

"Anthropology," American

Naturalist, 10 (November 1876), 694.

29. Otis T. Mason, "Anthropology,"

American Naturalist, 12 (October 1878), 696.

30. "American Anthropology," Philadelphia

Inquirer, September 8, 1876, 2.

31. "Centennial Prizes ... Adieu of

the Relic Hunters," Philadelphia Times, September 8,

1876, 1.

138 OHIO HISTORY

Pennsylvania (professor of comparative

philology at the University of

Pennsylvania), in arguing that "oil

and water could not be mixed." If

Putnam's proposal that the annual

meetings of the AAA and the AAAS be

combined were accepted it "would

kill the association [the AAA] and leave its

bones to bleach with those of similar

societies all over the land." The annual

meetings of the AAAS could offer

"only a slice of archaeology," whereas "the

whole of it was wanted." It was

better the new association "should stand on

its own merits or die at once on the

spot."32 A strong statement indeed. The

Smithsonian Institution and the American

Association for the Advancement

of Science had made invaluable

contributions to the field of archaeology, but

the interests and pursuits of those

organizations were much broader. The sub-

ject of American archaeology was too

important to be "merely the addenda of

something else."33

Brinkerhoff believed that much was to be

accomplished by bringing all in-

terested parties under the leadership of

a national organization devoted exclu-

sively to archaeology. Such cooperation

and coordination were necessary

since pride of locality would not permit

archaeological collections to be re-

moved permanently to a distant place for

study. It was better to work in har-

mony with local interests. With

pardonable pride of his own, Brinkerhoff

pointed to the work of the Ohio

Association as an example of what was to be

accomplished through cooperative

efforts. The association's archaeological

exhibit presented a collection comprised

entirely of private cabinets from

throughout Ohio. State archaeological

associations, on the model of those in

Ohio and Indiana, would have to be

established and recruited into the move-

ment. The scope of the work to be done

was so great, moreover, that both

the learned and the uninitiated should

be invited into the field.34 That asser-

tion is a clear expression of the

tension between professional and amateur ar-

chaeologists that has been a significant

part of American archaeology, past

and present.

The international archaeological

convention at Philadelphia adjourned with-

out determining the time and place of

the American Anthropological

Association's first annual meeting,

leaving that contentious matter to the

trustees. Peet doubted whether the AAA

could survive so long as it remained

in the shadow of the Subsection of

Anthropology. When the Ohio Historical

and Philosophical Society and the

Cincinnati Natural History Society invited

Peet to hold the annual meetings of the

State Archaeological Association of

Ohio and the American Anthropological

Association concurrently at

Cincinnati in 1877, he was eager to

accept. Peet was convinced that certain

members of the Subsection were

"disposed to kill our Assn if they can ....

32. Ibid.

33. "Archaeological," Philadelphia

Inquirer, September 5, 1876, 2.

34. Ibid.

In Search of the Mound Builders 139

If they get us to Nashville they'll

gobble us. All I want is one separate meet-

ing. If we can get a separate number of

men who are not members there[,]

they wont dare to oppose us or attempt

to absorb." He believed

William

Healey Dall, of the U.S. Coastal Survey

and Arctic exploring fame, was hos-

tile to the association's existence and

thought Putnam to be of the same

mind. He was uncertain about the opinion

of John Wesley Powell.35

Peet's separate meeting occurred at

Cincinnati, September 4 and 5, 1877.

The

Ohio State Archaeological Association and the

American

Anthropological Association shared the

same letterhead for the event, meeting

in the rooms of the Cincinnati Natural

History Society at Cincinnati College.

The meeting featured several important

papers, the mandatory exhibition of

local collections, and an excursion to

nearby Fort Ancient.36 It

was during

that excursion that Peet made "a

remarkable discovery." He saw the walls and

two mounds at the entrance of the Fort

Ancient enclosure as bearing a strik-

ing resemblance to two coiled serpents,

which were apparently engaged in

combat; the mounds at the entrance of

the enclosure formed their heads and

the exterior walls their rolling bodies.

Peet's interpretation of Fort Ancient

generated some interest at the time, but

opened him up to later criticism for

his pronounced theorizing tendencies.

Gerard Fowke, for instance, wryly

commented on Peet's imaginative

explanations of site features at Fort

Ancient that did not exist.37

In issuing the call for the first annual

meeting of the American

Anthropological Association, Peet

reported it to be in a "vigorous condi-

tion."38 It was clearly

otherwise given its competition with the anthropolo-

gists within the American Association

for the Advancement of Science. He

initially held out hope that those

attending the meeting of the AAAS at

Nashville would attend the Cincinnati

meeting, after the conclusion of the

35. Peet to Brinkerhoff, June 29,

[1877], Roeliff Brinkerhoff Papers, OHS.

36. "The Antiquaries. Who Built the

Mounds, and What Did They Build Them For?,"

Cincinnati Daily Gazette, September 6, 1877, 2; Archaeological. Meeting of the

Archaeological Society of Ohio, and the

American Anthropological Association," Ibid.,

September 7, 1877, 8;

"Anthropological. Visit to Fort Ancient," Ibid., September 7, 1877),

8;

"Archaeological Association of

Ohio," Cincinnati Commercial, September 5, 1877, 3; "Ohio

Archaeological Society," Ibid.,

September 6, 1877, 8; and "National Anthropological

Association," Ibid., September 6,

1877, 8.

37.

Stephen D. Peet, "Collections and Collectors in Ohio and Vicinity,"

American

Antiquarian, 1 (April 1878); 49-50; "The Serpent Symbol at Fort

Ancient," Ibid., 52-53;

Matthew Canfield Read to Peet, Hudson,

Ohio, n.d., as cited in Ibid., p. 53; and

"Anthropological. Visit to Fort

Ancient," Cincinnati Daily Gazette (September 7, 1877): 8.

Peet, like other observers before and

after him, thought the Portsmouth earthworks were also

representations of serpents. For Fowke's

criticism of Peet's general theory of parallel walls

among the earthen enclosures of Ohio and

his tendency to explain site features "which do not

exist" see Gerard Fowke, Archaeological

History of Ohio: Mound Builders and Later Indians

(Columbus, 1902), 158-59.

38. Stephen D. Peet, "First Annual

Meeting of the Anthropological Association," Printed

Circular, Ashtabula, Ohio, July 16,

1877, Brinkerhoff Papers, OHS. Same in Peet Papers, BCA.

140 OHIO HISTORY

sessions at Nashville. As he told Brinkerhoff, "Our

Anthropological

Association did not meet with the

kindest treatment after its separate session,

but I think we know who are its friends

and who its foes." When the

American Anthropological Association

held its second and last known meet-

ing on August 29, 1879, it was in

conjunction with the annual meeting of

the American Association for the Advancement

of Science at Saratoga, New

York. Peet, who did not attend the

meeting, informed Brinkerhoff that "It is

probable that it will be absorbed into

the A.A.A.S."39 That prediction appar-

ently came true. The American

Anthropological Association was either in-

corporated into the Subsection of

Anthropology at Saratoga or the Subsection

simply superseded it. Either way it

expired on the spot, a casualty of the di-

verging paths of professional and

amateur anthropologists.

The American Antiquarian: Religion

and Science

The founding of the first American

Anthropological Association did, how-

ever, result in one significant outcome.

Peet, as the corresponding secretary

of the AAA, established the

"Archaeological Exchange Club." The aim of

the club was to exchange fugitive papers

and to bring forward a journal of cor-

respondence and specialized studies in

archaeology and ethnology.40 The re-

sult of that initiative was the

appearance of the American Antiquarian in April

of 1878, edited by Peet. A quarterly

journal of archaeology, ethnology, and

history, the American Antiquarian was

the primary medium of publication

and correspondence for American

archaeology and ethnology prior to the ap-

pearance of the American

Anthropologist in 1888. Peet continued to edit the

American Antiquarian until 1911, and it remains an invaluable source of in-

formation about the concerns of the

American anthropological community in

the late nineteenth and early twentieth

centuries. Much of what we know

about the proceedings of the Ohio

Association and the first American

Anthropological Association, for

example, is found among its discursive

pages. Apparently Peet used some or all

of the membership dues of the Ohio

Association to launch the American

Antiquarian in 1878. He would later be

taken to task for that action by Matthew

Canfield Read, who accused Peet of

using the Ohio Association to advance

his own reputation.41

39. Peet to Brinkerhoff, Ashtabula,

January 1, 1878, and Peet to Brinkerhoff, Unionville,

Ohio, August 13, 1879, Brinkerhoff

Papers, OHS.

40. Stephen D. Peet,

"Archaeological Exchange Club," Printed Circular, Ashtabula, October

5, 1877, Brinkerhoff Papers, OHS, and

"The American Antiquarian," Printed Circular,

Ashtabula, Ohio, February 22, 1878, Peet

Papers, BCA. Published by "the Archaeological

Exchange Club." E. A. Barber,

"Anthropology, Archaeological Exchange Club," American

Naturalist, 11 (March, 1877), 180.

41. Read to Albert Adams Graham, Hudson,

Ohio, October 6 and October 8, 1887, Officer

and Administrative Offices Records,

Secretary-Editor Correspondence, Series 4005, Box 1254,

|

In Search of the Mound Builders 141 |

|

The establishment of the American Antiquarian was yet a further reflection of Peet's estrangement from the anthropologists within the American Association for the Advancement of Science. His differences with that group ran far deeper than squabbles over the venues of annual meetings for the American Anthropological Association, as important as they were. A con- flict between evolution and scripture also played a part. One of Peet's mo- tives for founding the American Antiquarian, though certainly not the only one, was to address such "conflicts of thought." The good reverend saw a need to create an anthropological journal that would cooperate with the secular scientific establishment, but could also speak independently of it. "Anthropology is the battleground for all the conflicts of thought now going on between Revelation and Nationalism, faith and skepticism-creation and evolution, etc." It would be necessary for his proposed journal to "open its

Folder 1. Archives-Library Division, the Ohio Historical Society. |

142 OHIO HISTORY

pages [to] the controversy."

Significantly, he asked: "Has the time come to

appeal to clergymen[,] theologians and

evangelical Christians etc. to join the

standard against the powerful Journals

which are now advocating so strongly

the skeptical views of the adored

thinkers of the scientific world?" 42

The American Anthropological

Association, Peet privately acknowledged,

was partly established as a means of giving

a voice to archaeologists and eth-

nologists with religious sentiments, as

a counterbalance to the "strong evolu-

tiona[ary] sentiments" he

attributed to members of the American Association

for the Advancement of Science. "We

may have to struggle to secure a

foothold and this Journal may need to

[take] a position as strictly

Archaeological-before the real contest

is begun."43 It is good for Peet's his-

torical reputation that he chose not to

incite an open contest between religion

and science in the American

Antiquarian. Owing to the immediate success of

the journal, he chose not to alienate

the leading lights of the anthropological

community who were frequent contributors

to its pages. Questions relating

to the origin, antiquity, geologic

position, and physical structure of prehis-

toric man were brought within the scope

of the journal, but he kept the

American Antiquarian primarily secular in tone and content. Had he done

otherwise, the goal of making the

publication the primary medium of research

and correspondence among American

archaeologists and ethnologists would

have greatly suffered.

The battle between religion and

anthropological science in the late nine-

teenth century is nowhere more evident

than in the thought of Stephen

Denison Peet. He was stuck on the horns

of a dilemma from which he could

not free himself. He sought to promote

anthropological science, a passionate

avocation, but to do so within the

framework of his own religious convic-

tions. Peet managed to harmonize his

archaeological and theological pur-

suits, at least to his own satisfaction,

across a long and productive career.

Yet he clearly turned his face against

those in the scientific community who,

as he believed, sought to banish God

from anthropology.

It is singular that the men of the Am.

Assn. have so much control and that so much

of the unbelieving sentiment prevails

and that that class has the power. I can see

the way before us very clearly as

indicating a rally of the Christian scholars of the

country .... Very quietly but surely we

can work together an association which

shall be a power in the country.44

That was the arena in which the battle

between religion and science was to be

fought.

42. Peet to unknown party, letter draft,

Ashtabula, Ohio, December 22, 1876, Peet Papers,

BCA.

43. Ibid.

44. Peet to Brinkerhoff, Ashtabula, July

15, 1877, Brinkerhoff Papers, OHS.

In Search of the Mound Builders 143

Peet's private struggle as a man of the

cloth and "Christian scholar" against

the "unbelieving sentiments"

he attributed to those who controlled the

American Association for the Advancement

of Science was never resolved.

Peet cooperated more times than not with

the scientific community from

which he often felt estranged, but

worked quietly behind the scenes to ensure

that he and other Christian scholars

would be heard. As he explained, "The

Naturalists of the AAAS are a very

scholarly set and they imagine that no

one outside of their circle of young

scientific skeptics can do anything." Yet

he was determined to give a voice to

scholars, "some of whom are religious,"

without regard to "the clique"

which sought to rule the AAAS.45 So far as

the history of American anthropology is

concerned, it was the secular-minded

scientists who carried the day. If

Christian scholars like Peet were unwilling

to go quietly into the night, they were

equally reluctant to discredit the sci-

ence of anthropology to which they were

irresistibly drawn.

Brinkerhoff addressed the struggle

between scripture and science at the open-

ing of the Ohio State Archaeological

Convention by asking a trilogy of ques-

tions: "What are we? Whence came

we? Whither are we tending?"

It is true we have a written revelation

which answers these questions, and many of

us. and perhaps all of us who are here

today, believe that it answers them rightly,

but still we all know and all admit that

there is another gospel, which, so far as its

revelations are extended, is more

conclusively true to most minds than the other.

The gospel of Nature is a thing of the

senses .. . and therefore if the gospel

of

Nature comes in conflict with the gospel

of Revelation, the latter must go to the

wall. It is inevitably so in the nature

of things.

Brinkerhoff confessed his belief in the

truthfulness of both gospels and their

essential harmony. "Nevertheless,

let us have the truth, wheresoever it may

lead." By studying human experience

archaeologists may discovery a glimpse

of human destiny besides.

"Archaeology, it is true, is but a single chapter in

the gospel of Nature, but it is so

associated and correlated that its interpreta-

tion demands mastery of all the

others." He was willing to let rationalism

lead where it would on the question of

the origin and antiquity of man.

Similar sentiments were expressed in the

American Antiquarian by another

prominent member of the Ohio

Association, Matthew Canfield Read. Read,

an accomplished geologist and

archaeologist, saw "coincidences" of science

45. Peet to "Dear Bro." [John

Thomas Short], Unionville, Ohio, June 20[?], 1879, Townsend

Papers, OHS.

46. Brinkerhoff, "Address of

Welcome," Minutes of the Ohio State Archaeological

Convention, 11. His musings on the relationship between religion

and evolution clarify how he,

and presumably other members of the Ohio

Association, resolved their faith as Christians with

their faith in science. See Brinkerhoff,

Recollections of a Lifetime, 15, 19, 85, 87, 342, and 425.

His "philosophic convictions"

on the origin of life were given in an essay prepared for the

Mansfield Lyceum in May of 1886. See

"Law of Biogenesis in Its Application to Man," Ibid.,

342-48.

144 OHIO HISTORY

and scripture. There were no

irreconcilable differences between the evolution-

ist's natural laws and the theists

divine will, if the Biblical account of cre-

ation was accepted as allegory. Read

rationalized Genesis and the geologic

revolution of the nineteenth century as

a "theistic evolutionist," one who be-

lieved that the divine will which

animated life was none other than the natural

law of the evolutionist.47 Biblical cosmology and the symbolism

of the

Garden of Eden were meant to instruct,

he believed, and should not be consid-

ered a literal record of the origin and

descent of man.48 Read's position on

evolutionary science relative to literal

creationism is significant. It further

explains the views of Brinkerhoff, Peet,

and other members of the Ohio

Association who chose to have faith in

both science and scripture. It would

be unwarranted to assume that all

members shared that conception. But those

who provided intellectual leadership had

worked evolutionary principles into

their formulations of faith as Christian

scholars.

The Call for State Support and the

Inability to Coordinate

Fieldwork

The success of the Ohio Association's

archaeological exhibit at

Philadelphia and the leading role it

played in the founding of the first

American Archaeological Association

appeared to bode well for the future.

With such auspicious beginnings, the

Association's mission seemed well in

tow. The ultimate results of those early

accomplishments, however, fell far

short of early expectations. Whittlesey

and Read had originally intended to

make a complete report on Ohio's

antiquities, including both a descriptive and

illustrative catalog of the

association's archaeological exhibit and an expanded

version of Whittlesey's archaeological

map of Ohio. But due to the inade-

quacy of state funds, the project was

abandoned. The attenuated report they

submitted to the Ohio Board of

Centennial Managers did little more than tab-

ulate the number and class of artifacts

exhibited at Philadelphia. A further in-

adequacy was that the report identified

a meager 119 of the estimated 10,000

Ohio mounds and earthworks believed to

be in existence within the state of

Ohio. Such incompleteness satisfied few,

least of all the report's compilers,

Whittlesey and Read.

The mission of the Ohio Association

clearly went beyond the resources and

capabilities of individuals and amateur

associations. The creation of a state

museum and the completion of accurate

archaeological surveys required liberal

support from the state if it was to be

done at all. Whittlesey and Read force-

47. Matthew Canfield Read,

"Evolution," American Antiquarian, 3 (October, 1880), 35, 38.

48. Matthew Canfield Read, "The

Symbolism of the Garden of Eden," American

Antiquarian, 3 (January, 1881), 131.

In Search of the Mound Builders 145

fully made that point in their report to

the Ohio Centennial Managers. Ohio,

they noted, was once the homeland of a

skilled and long-departed people. It

was incumbent upon its inheritors to do

all that was possible to properly

study and preserve the mute records they

left behind.

It is of the first importance that all

these works should be carefully explored, sur-

veyed, and platted, and all information

that can be gathered be systematized and

preserved. Private explorers often

demolish important works, and preserve no

valuable information in regard to them.

Mere curiosity-hunters frequently destroy

these ancient mementos, thus doing

irreparable injury to the work of the scientific

archaeologist. It is confidently hoped

that in some way the Legislature of the

State will make some provision for this

work.49

That eloquent but unanswered call for

state support foreshadowed the ultimate

cause of the Association's demise.

Although long on enthusiasm and laud-

able objectives, it was ever short of

the ways and means to carry them out.

The failure of the State Archaeological

Association of Ohio to get state

support for its stated purposes was not

for want of trying. The officers and

trustees submitted a memorial to the

Senate and House of Representatives in

February of 1878, seeking the release of

the balance of the $32,000 appropria-

tion made by the Ohio General Assembly

to fund the state exhibits at the

1876 Centennial Exposition in

Philadelphia. That balance would be used to

fund a state archaeological survey and

the establishment of a "State Cabinet of

Archaeology" at Columbus. Governor

Richard A. Bishop was said to favor

the idea of a state cabinet and the

appropriation sought in the association's

memorial to the legislature.

Brinkerhoff, William B. Sloan of Port Clinton,

and Ebenezer Baldwin Andrews and Silas

H. Wright of Lancaster were ap-

pointed to the committee that drafted

and presented the association's memorial

to the legislature.

The memorial was introduced into the

Ohio Senate by Senator Henry C.

Lord of Hamilton County, a member of the

Senate Finance Committee and

the Committee on the Geological Survey.

Senate Bill Number 82 authorized

the archaeological association of Ohio

"to make accurate surveys and descrip-

tions of the pre-historic works of the

State, and to collect pre-historic relics

for a State Cabinet of archaeology, to

remain forever the property of the

State." The work was to be

conducted by the Ohio Association and paid for

with the $5,000 balance reported to be

in the centennial fund. The bill was

referred to the standing committee on

the state geological survey which rec-

ommended its passage. Peet reported that

among the association's officers

and trustees Charles Candee Baldwin,

Whittlesey, Andrews, and Isaac

Smucker all favored a separately-funded

archaeological survey, but it was bet-

49. M. C. Read and Charles Whittlesey, Final

Report of the Ohio State Board of Centennial

Managers, 82.

146 OHIO

HISTORY

ter that it be initiated as part of the

state geological survey than not at all.

Brinkerhoff favored that approach, while

Peet was unsure. The bill passed the

Senate by a simple majority, but failed

to met the required constitutional ma-

jority.50 The Ohio

Association came that close to obtaining state aid only to

come away empty handed.

The legislative setback on the state

archaeological survey and cabinet came

hard on the heels of another. The Ohio

Association also failed in its petition

for the release of 1,000 of the 15,000

copies of the Report of the Ohio

Centennial Commissioners, which included the association's report on the

"Antiquities of Ohio."

Incomplete as the report was, it could nonetheless be

used to promote interest in Ohio

archaeology and to keep the association's

name before the public. The

association's memorial to the state legislature

for the release of additional copies of

the report echoed Whittlesey and Read's

earlier plea for assistance.

We are doing all in our power to awaken

attention to the wonderful evidences of

the races which once existed here. They

are fast disappearing. Other States and

other countries are gathering our

relics. We have no cabinet. The wear of time and

advance of civilization are destroying

the earthworks; they have never been com-

pletely surveyed. May we not expect that

you will interest yourself in this?51

That appeal likewise went unanswered. It

would be the Association's last.

Whittlesey, who had long supported the

idea of a state supported archaeo-

logical survey, knew that nothing would

be done unless the Association or its

mouthpiece at Columbus would

"hound" the state legislature for funds.

Are there any members who will make it a

subject of personal effort? Is there any-

one ready to lobby the measure at

Columbus? No appropriation should be ex-

pected without both commitments. We know

of no one who will do the work[,]

certainly none of the officers of the

Archaeological Society at Columbus.52

Even Peet grew disheartened and

increasingly frustrated after the Association's

leadership failed to regroup and renew

its lobbying with the legislature. He

was convinced that the association could

yet be made a "protege of the state,"

50. Peet to Brinkerhoff, Ashtabula,

January 15, 1878 and January 23, [1878]; Whittlesey to

Brinkerhoff, Cleveland, January 18,

1878; and E. B. Andrews to Brinkerhoff, Lancaster, Ohio,

April 13, 1878, Brinkerhoff Papers, OHS.

"Archaeological Matters. Memorial

to the

Legislature-Bill Being Drawn,

Etc.," Columbus Dispatch, February 13, 1878), 4; The Journal

of the Senate of the State of Ohio

for the Session of the Sixty-Third General Assembly,

Commencing Monday, January 8, 1878 vol. 74 (Springfield, Ohio, 1878), 187, 982; and

"Senate Bill No. 82," Senate

Bills Reg. Session, 63rd Gen'l Assembly, 1878, 1-191 [Series

1217], bound volume, no pagination,

State Archives of Ohio, Archives-Library Division, Ohio

Historical Society.

51. Stephen D. Peet, Ashtabula, January

14, 1878, [Untitled, Printed Circular], Brinkerhoff

Papers, OHS. Same in Peet Papers, BCA.

52. Whittlesey to Brinkerhoff,

Cleveland, January 18, 1878, Brinkerhoff Papers, OHS.

|

In Search of the Mound Builders 147 |

|

|

|

if its officers and friends at Columbus would only "push." He repeatedly complained that he could not recoup the money due him for the printing of circulars and for postage issued on the Association's behalf. Despairingly, he reminded Brinkerhoff that "It costs something to run such a society and I am not a man of ease and fortune to work for nothing and pay the expense."53 Another measure of the association's ineffectiveness was its inability to coordinate or direct archaeological fieldwork in Ohio. There was an explosion of activity in the state during the late 1870s and early '80s, throughout which the Ohio Association largely remained a passive spectator. It could do little more than encourage local organizations to take the field and report on the progress of their investigations at its own annual meetings. As Peet noted in the American Antiquarian, amateur associations and exploring parties were the order of the day. The Central Ohio Scientific Association at Urbana investi- gated archaeological remains in the Mad River Valley, where Thomas F. Moses opened mounds in 1876 and 1877, and J.E. Werren surveyed the earthworks near Osborn, Ohio. Even more noteworthy were the explorations of the Literary and Scientific Society of Madisonville in the Little Miami Valley. Those much-publicized investigations were funded by the Cincinnati Society of Natural History, which became the repository of the human crania recovered from the Madisonville site. The reports of Charles F. Low, Charles

53. Peet to Brinkerhoff, Ashtabula, June 24, [1877], August 4, [1877], January 1, 1878, January 15, 1878, January 23, [1878], and May 12, [1878], and Peet to Brinkerhoff, Unionville, Ohio, August 13, 1879, Brinkerhoff Papers, OHS. |

148 OHIO

HISTORY

L. Metz, and Frank W. Langdon on the

Madisonville excavations were mod-

els of archaeological reporting.54 The

vitality exhibited by these local associ-

ations rendered the state association

all the more ineffectual by comparison.

Equally symptomatic of the association's

troubles was its position relative

to the activities of Harvard's Peabody

Museum in Ohio. The curator of the

Peabody, Frederic Ward Putnam, sought an

annual fund at the museum of

$3,000 to promote archaeological

investigations in Ohio, "before it is too

late." The time had passed, he

noted, when haphazard explorations and

"chance gatherings" of

materials were considered the chief aims of archaeol-

ogy. This was the great era of mound

exploration and museum building at

the Peabody, when prehistoric materials

were leaving Ohio literally by the

barrel. Putnam was well on the way to

making the museum the central de-

pository of American antiquities, even

as the Ohio Association struggled for

its very existence. The Peabody had the

funds to support systematic field-

work in Ohio, and there were many able

hands in the state willing to offer

their services as field agents. That

situation represented a decided predicament

for the Ohio Association, since some its

own officers and trustees were work-

ing for Putnam too. Ebenezer Baldwin

Andrews of Lancaster explored Ash

Cave in Hocking County and mounds in

southeastern Ohio, John Thomas

Short of Columbus opened three mounds in

Delaware County in 1879, and

Matthew Canfield Read sent Putnam

pottery fragments and stone chips from a

rock shelter at Hudson in June of

1878.55 It was better for the more active

members of the Ohio Association to cooperate

with the Peabody than do

nothing at all.

Peet's position relative to mound

explorations in Ohio leaves little to the

imagination. The Ohio Association had

been partly established to control the

conditions under which explorations

occurred, how they were conducted, and

by whom. It had failed miserably in that

endeavor, but Peet thought it better

to encourage those who were capable of

scientific exploration and reporting

than to abandon the field entirely to

"relicologists." He praised the fieldwork

54. Stephen Denison Peet, "Recent

Explorations of Mounds, and Their Lessons," American

Antiquarian, 1 (July, 1878), 101-09; Charles L. Metz, "The

Prehistoric Monuments of the Little

Miami Valley, Journal of the

Cincinnati Society of Natural History, 1 (1878-1879), 119-28;

Thomas F. Moses,."Report on the

Antiquities of the Mad River Valley," Proceedings of the

Central Ohio Scientific Association 1, Part. 1 (1878), 23-49; and J. E. Werren, "Report

on the

Survey of Ancient Works near Osborn,

0.," Ibid., 52-61. The Central Ohio Scientific

Association was established at Urbana in

November of 1874. Thomas F. Moses, a physician,

was corresponding secretary and curator.

"Notes," American Naturalist, 9 (April, 1875), 225.

55. E .B.Andrews, "Report on

Exploration of Ash Cave in Benton Township, Hocking

County, Ohio," Tenth Annual

Report of the Trustees of the Peabody Museum of American

Archaeology and Ethnology, 2 (1880), 48-50, and "Report on Explorations of

Mounds in

Southeastern, Ohio," Ibid., 51-74.

F. W. Putnam, "Report of the Curator," Thirteenth Annual

Report of the Trustees of the Peabody

Museum, 1880 in Reports of the

Peabody Museum of

American Archaeology and Ethnology, 2(1876-1879), 721 and "Additions to the Museum and

Library for the Year 1879," Ibid.,

743.

In Search of the Mound Builders 149

of Harvard's Peabody Museum of American

Archaeology and Ethnology, and

the care taken by Putnam and his Ohio

associates in conducting those explo-

rations. The skill they manifested stood

in bold relief to the "superficial" and

"haphazard" digs of relic

hunters.56 He was less

complimentary of the

Smithsonian Institution's Bureau of

American Ethnology, charging it with

the wanton destruction of mounds in an

effort to enlarge the collections of the

National Museum.57

Peet railed against the rage for relic

collecting and museum building,

which, he charged, often destroyed

mounds before they had been properly sur-

veyed. He regretted that some in Ohio considered

relic hunting a proper line

of research, which somehow promoted the

cause of archaeological science.

"The collector who hoards relics

and digs into the mounds for the sake of col-

lecting, imagines himself to be a

contributor to science." That misplaced be-

lief was no longer to be tolerated, nor

were the "positive evils" to which it

gave rise.58 Particularly

vexing were those persons, known in their localities

as "Eminent Scientists," who

boasted of exploring hundreds of mounds, but

whose accounts of their destructive

deeds contained nothing of archaeological

importance.59 There is a hint

of frustration, disappointment, and perhaps

anger in Peet's fulminations.

He and his compatriots in the Ohio

Association never realized the goal of

establishing a state archaeological sur-

vey and museum, nor of controlling the

activities of others within the state.

The Mound Builders: A Divergence of

Views

Any assessment of the State

Archaeological Association of Ohio must take

into account the divergent views of its

members on the origin and identity of

the venerable Mound Builders. The

question of who were the ancestors and

who the descendants of the Mound

Builders led to animated discussions at an-

nual meetings, and sometimes pitted

members against each other in a war of

56. Stephen Denison Peet, "The

Peabody in the Field," American Antiquarian, 6 (July, 1884),

277.

57. Stephen Denison Peet,

"Explorations of Mounds,"American Antiquarian, 5 (October,

1883), 333. Peet's editorializing on

mound explorations led Cyrus Thomas, director of ar-

chaeological fieldwork at the Bureau of

American Ethnology, to defend its methods. See

Cyrus Thomas, "The Destruction of

Mounds," American Antiquarian, 6 (January,1884), 41,

and "Manner of Preserving Mound

Builders' Relics," Ibid. 6 (March, 1884), 103-06. Peet

eventually made peace with the Bureau of

American Ethnology. He briefly became a field

agent in Wisconsin, making corrections

and additions to Thomas's list of prehistoric sites.

Cyrus Thomas, "Catalogue of

Prehistoric Earthworks East of the Rocky Mountains," United

States Bureau of Ethnology, Bulletin

12 (Washington, D.C., 1891), 7.

58. Stephen Denison Peet, "Relic