Ohio History Journal

|

|

|

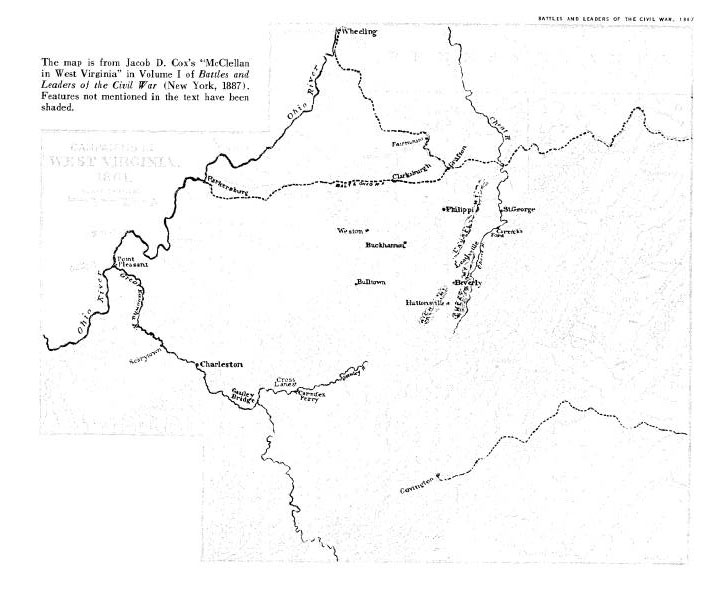

As the secession crisis in the Old Dominion approached its climax in May 1861, the Unionists of northwestern Virginia looked anxiously to the state of Ohio for "deliverance from tyranny." On May 26, 1861, only three days after Virginia formally seceded from the Union, Major General George B. McClellan, commander of the department of the Ohio, launched his invasion to preserve western Virginia for the Union. To his troops McClellan issued the first in a series of colorful, if exaggerated, manifestoes that helped to earn him the title, "The Young Napoleon of the West." NOTES ARE ON PAGES 193-194 |

84 OHIO HISTORY

"Soldiers!" he began,

You are ordered to cross the frontier,

and enter upon the soil of Virginia.

Your mission is to restore peace and

confidence, to protect the majesty of the

law, and to rescue our brethren from the

grasp of armed traitors. You are to

act in concert with [loyal] Virginia

troops, and to support their advance. ...

Preserve the strictest

discipline;--remember that each one of you holds in his

keeping, the honor of Ohio and the

Union. If you are called upon to overcome

armed opposition, I know that your

courage is equal to the task;--but remember,

that your only foes are the armed

traitors,--and show mercy even to them when

they are in your power, for many of them

are misguided. When, under your

protection, the loyal men of Western

Virginia have been enabled to organize

and arm, they can protect themselves,

and you can then return to your homes,

with the proud satisfaction of having

saved a gallant people from destruction.1

At 5 A.M. on the morning of May 27,

1861, the First (West) Virginia

Regiment accompanied by four companies

of the Second (West) Virginia

Volunteers proceeded southeast from Wheeling

along the line of the Balti-

more and Ohio Railroad toward a

Confederate encampment in the interior.

The Sixteenth Ohio, stationed at

Bellaire, across the river south of Wheeling,

was ordered to support the movement. To

the south, the Fourteenth and

Eighteenth Ohio regiments occupied

Parkersburg.2 Colonel Frederick W.

Lander, aide-de-camp to McClellan,

directed the invasion at Parkersburg,

while Colonel Benjamin F. Kelley,

commander of the First (West) Virginia

Volunteers, led the spearhead south from

Wheeling.3

On learning that Kelley had reached

Fairmont, some twenty miles from

his position at Grafton, Colonel George

A. Porterfield, the Confederate

commander, withdrew his troops to

Philippi, fifteen miles further south.4

Kelley continued his advance without

opposition.5 Meanwhile, the Fourteenth

Ohio moved east from Parkersburg. On

June 1 Lander joined the Fourteenth

near Clarksburg and ordered Colonel

James B. Steedman to prepare his

troops for a night march on June 2 against

Porterfield at Philippi. Lander,

accompanied by an advance guard, pushed

on to Grafton. There he found

Kelley, who had been joined by Indiana

troops under Brigadier General

Thomas A. Morris, planning an attack on

Porterfield also. A council of war

followed and the decision was made to

march on Philippi in two converging

columns--one wing directed by Kelley,

the other by Lander.6

At noon on June 2 Kelley's troops were

transported by rail to a point

eight miles east of Grafton and marched

south. Lander, reinforced by the

Eighteenth Ohio and the Sixth and Ninth

Indiana regiments, detrained at

Webster, a few miles west of Grafton. As

a result of a forced march on a

rainy, moonless night Kelley and Lander

arrived at Philippi almost simul-

taneously before dawn on the morning of

June 3.

|

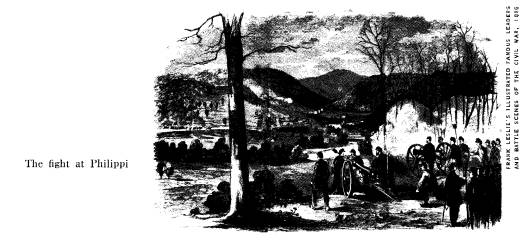

WESTERN VIRGINIA CAMPAIGN OF 1861 85 The attack was scheduled to begin at 4 A.M. Unfortunately, neither Lander nor Kelley was able to get into position on time. Moreover, Kelley took the wrong fork of a road leading into Philippi. As a consequence, both Union columns approached Porterfield's encampment on the same side of town. By 4:30 A.M. Lander's guns were in position; but he had not yet com- municated with Kelley. On observing the Rebels breaking camp, Lander's batteries opened fire and the Ninth Indiana moved forward. As fate would have it, Kelley's arrival on the scene coincided with the beginning of Lander's bombardment. As a result, the (West) Virginia volunteers led the attack. The Confederates fled in confusion. Within minutes the "Philippi Races," the first land battle of the Civil War, was over. Had the attack proceeded |

|

|

|

according to plan, Porterfield would not have escaped. As it was, his com- mand was shattered. The Confederates lost 750 stand of arms, and all of their ammunition, supplies, and equipment.7 Few casualties were suffered by either side; but federal troops took a number of prisoners, including Lieutenant Colonel William J. Willey.8 The encounter at Philippi, better described as a skirmish than a battle, nevertheless had profound implications so far as the future of western Virginia was concerned. On June 7 General Thomas S. Haymond, at Rich- mond, received an urgent telegram from the northwest. "Our troops at Philippi," it read, "have been attacked by a large force with artillery under McClelland [sic] and drew back to Beverly. We must have as large a number of troops as possible from Richmond without a moments [sic] delay or else abandon the Northwest."9 Shortly thereafter Brigadier General Robert S. Garnett took command |

86 OHIO

HISTORY

of Confederate troops in the northwest;

but never was Garnett in a position

to launch offensive operations against

the superior forces thrown into western

Virginia from Ohio. From his

headquarters at Laurel Hill, Garnett apprised

General Robert E. Lee, in command at

Richmond, of the difficulties he faced.

Arriving at Huttonsville on June 14,

Garnett reported:

I found there twenty-three companies of

infantry . . . in a miserable con-

dition as to arms, clothing, equipments,

instruction, and discipline. Twenty of

these companies were organized into two

regiments, the one under Lieutenant-

Colonel Jackson and the other under

Lieutenant-Colonel Heck. Though wholly

incapable, in my judgment, of rendering

anything like efficient service, I deemed

it of such importance to possess myself

of the two turnpike passes over the Rich

and Laurel Mountains, before they should

be seized by the enemy, that I left

Huttonsville on the evening of the 15th

with these two regiments and Captain

Rice's battery, and, by marching them a

greater portion of the night, reached

the two passes early in the afternoon of

the following day. . . .

I regard these two passes as the gates

to the northwestern country, and, had

they been occupied by the enemy, my

command would have been effectually

paralyzed or shut up in the Cheat River

Valley. I think it was a great mistake

on the part of the enemy not to have

remained here after driving Colonel

Porterfield's command over it. . . .

This force I consider more than

sufficient to hold these two passes, but not

sufficient to hold the railroad, if I

should get an opportunity of seizing it at

any particular point; for I must have an

adequate force in each of the passes

to secure them for our use.10

Lee had urged Garnett to destroy the

Cheat River bridge on the Baltimore

and Ohio. Even though Garnett recognized

the importance of this objective,

he advised Lee, "My moving force

(say three thousand) . . . will not be

sufficient, I fear, for this

operation."11 At no time did Garnett's army exceed

4,500 (including a Georgia regiment

which did not arrive until June 24),

while McClellan was to have nearly

20,000 men at his disposal in the

northwest alone. Garnett himself had a

rendezvous with death at Carrick's

Ford on July 13. In retrospect, the

feeble efforts made by the authorities at

Richmond to hold the northwest were

doomed from the beginning.

Porterfield had been ordered to Grafton

on May 4 by Lee to "select a

position for the troops called into the

service of the State, for the protection

and defense of that part of the

country." Using Grafton as a base of oper-

ations, Porterfield was directed to

occupy Parkersburg and Wheeling and

prevent the Baltimore and Ohio

"from being used to the injury of the

State."12 Obviously, Lee

expected an invasion from Ohio. Yet, his orders

to Porterfield were totally unrealistic

and therefore impossible to implement.

By far the largest number of troops to

be used in these operations were to

WESTERN VIRGINIA CAMPAIGN OF 1861 87

be raised in the northwest itself. On

May 3 Governor John Letcher had

ordered the militia of nineteen

northwestern counties to rendezvous at Park-

ersburg and Grafton.13 The

major difficulty in this plan was the fact that

twelve of those nineteen counties were

Union strongholds. Few militiamen

answered a Confederate "call to

the colors" from these areas; and the seven

secessionist counties listed in

Letcher's proclamation did not contain the

manpower necessary for carrying out

Lee's instructions.

Furthermore, adequate provision was not

made for supplying Porterfield

with arms, ammunition, and equipment.

On May 4 Lee informed Porterfield

that two hundred muskets had been sent

to Colonel Thomas J. "Stonewall"

Jackson at Harpers Ferry and would be

forwarded to Grafton.14 Ten days

later Lee shipped Porterfield another

six hundred muskets.15 If these sup-

plies arrived, they were not nearly

enough. On May 29 Porterfield reported

that during his retreat from Grafton to

Philippi, he was met by an unarmed

company of volunteers from Upshur

County which he was compelled "to

send home, for want of arms to supply

them with." Earlier he had been

forced to dismiss two cavalry

companies--one each from Barbour and

Pocahontas counties for the same

reason.16 As a result, Porterfield, with

only a thousand poorly equipped and

untrained militiamen under his com-

mand, was in no position to occupy

Parkersburg and Wheeling; nor could

he systematically destroy the railroad

bridges along the line of the Baltimore

and Ohio Railroad after the invasion

began. Unable to oppose Kelley at

Grafton, he withdrew to Philippi.

"As soon as I can organize my com-

mand," he wrote, "which I

hope to do soon, I will return to some more

eligible point in the neighborhood of

Grafton, which will enable me to

command both railroads."17 Porterfield

was "whistling in the dark." The

major flaw in his strategy under the

conditions he had to face was the fact

that he did not retreat far enough fast

enough.

Although George B. McClellan won glory

and the command of the army

of the Potomac for his military

exploits in northwestern Virginia, Governor

William Dennison of Ohio must be given

a full measure of recognition for

making the invasion of northwestern

Virginia possible. His efforts have not

been fully appreciated.

As early as January 1861 Dennison

warned Governor Letcher that the

"entire power and resources of the

State of Ohio" were to be offered to the

president of the United States to

coerce and subjugate seceding states.

Naturally enough, Letcher considered

this letter an implied threat against

Virginia.18 And indeed it

was! When the Virginia Convention of 1861

passed an ordinance of secession on

April 17, Dennison launched a vigorous

program to defend Ohio against

invasion.

88 OHIO HISTORY

One of the first important decisions

made by Dennison was his choice of

McClellan to command the Ohio

volunteers. The appointment, on April 23,

was received with general approbation

throughout the North.19 In addition to

McClellan, the appointment of Jacob

Dolson Cox and William S. Rosecrans

as brigadier generals proved to be

salutary. If not brilliant commanders,

these two were competent officers. In a

day when politics often determined

the appointment of officers to high

command their selection was no mean

achievement in itself.

On April 26 the Ohio legislature passed

an act conferring war powers on

Dennison. The Ohio governor acted

swiftly. On May 1 he advised R. W.

Taylor, auditor of the state of Ohio,

that he planned "to call into active

service nine regiments of Infantry and a

proper proportion of artillery and

cavalry." He requested that funds

be made available immediately for

expenses incurred.20 Dennison

then dispatched purchasing agents to Illinois

and New York City to acquire arms and

made arrangements to buy addi-

tional quantities in Europe. He also

took steps to give the military top

priority in the use of rail and telegraph

lines. As the national government

had to rely on state governments almost

exclusively in the early stages of

the war for troops, arms, ammunition,

and supplies, governors such as

Morton of Indiana and Dennison exercised

great influence on Lincoln and

the war department.

On April 27 the Ohio governor wrote to

Lincoln recommending that

McClellan be placed in charge of all

military forces west of the Alleghenies.21

A week later McClellan was chosen to

command the newly created depart-

ment of the Ohio, composed of the states

of Ohio, Illinois, and Indiana.22

But Dennison was not satisfied. On May 7

he again contacted Washington,

urging that western Virginia be placed

under McClellan's jurisdiction also.

The next day this request was granted.23

Dennison's purpose was quite clear.

He immediately wrote McClellan at

Cincinnati, urging him to occupy Park-

ersburg.24 McClellan

hesitated. The information he received from the

"frontier" indicated

"that the moral effect of troops directly on the border

would not be very good--at least until

Western Virginia has decided for

herself what she will do."25 Dennison,

however, was not disposed to await

the outcome of the vote on the secession

ordinance on May 23. While he

did not attempt to interfere with

McClellan's conduct of military operations,

he continued to make strong suggestions.

On May 20 Dennison received word from

Wheeling informing him of

Confederate troop movements in the

vicinity of Grafton.26 Immediately the

Ohio governor wired Winfield Scott, the

federal general in chief, and Mc-

Clellan of these developments. Scott's

reply apparently was vague and

90 OHIO HISTORY

indecisive. Later that same day Dennison

sent a second dispatch to Mc-

Clellan and urged the immediate invasion

of western Virginia without

specific instructions from Washington.

It can never be said of Dennison

that he was not a man of action. In his

dispatch to McClellan he said:

Enclosed I send you [a] copy of my

telegram to Genl Scott and his reply

from which you will see he is not

disposed to share any of the responsibility

in taking care of Western Virginia. This

being so will it not be better for you

to take this part of your military

district under your immediate supervision

and provide whatever you may deem

necessary for its protection! Will not the

responsibility justify your asking for

an increase of the Ohio Contingent and

for all the arms and accompaniaments [sic]

that will be needed for its vigorous

discharge: It seems to me to so open the

way as to enable you to command all

the area and means necessary for the

prompt assured occupation of Western

Virginia and for carrying out your plan

of campaign in respect to that part

of the Union. Whatever aid I can render

is at your command.27

Scott's reasons for declining to issue

specific orders to McClellan re-

garding western Virginia are not clear.

Possibly he felt that direct action

before the ratification of the secession

ordinance by the Virginia electorate

would be premature. On April 27 Scott

had commented in a note to Lincoln

that "a march upon Richmond from

the Ohio would probably insure the

revolt of Western Virginia, which if

left alone will soon be five out of seven

for the Union."28 On the

other hand, Scott sent a strongly worded communi-

cation to McClellan on May 21 expressing

displeasure at McClellan's com-

plaint to the secretary of war that he

was without "instructions or authority."

Said Scott: "It is not conceived .

. . what instructions could have been needed

by you. Placed in command of a wide

Department . . . it surely was unnec-

essary to say that you were expected to

defend it against all enemies of the

U. States."29

If Scott's dispatch can be accepted at

face value, it might well be argued

that he expected McClellan to use his

own best judgment as to what action

was necessary within the boundaries of

his own department. Finally, on

May 24, four days after Dennison had

telegraphed Scott urging immediate

action, and only one day after the vote

on secession, Scott wired McClellan

in Cincinnati:

We have certain intelligence that at

least two companies of Virginia troops

have reached Grafton, evidently with the

purpose of overawing the friends of

the Union in Western Virginia. Can you

counteract the influence of that

detachment? Act promptly, and Major

Oakes, at Wheeling, may give you

valuable assistance.30

Certainly this telegram was not a

specific order instructing McClellan to

WESTERN VIRGINIA CAMPAIGN OF 1861 91

launch offensive operations in western

Virginia. But it is clear that Mc-

Clellan believed that Scott now expected

action. Following Philippi he wrote

Scott, "I trust, General, that my

action in the Grafton matter will show you

that I am not given to

procrastination."31

In the final analysis, it is plain that

McClellan's contention in later years

that he had acted entirely upon his own

authority and of his own volition,

"and without any advice, orders, or

instructions from Washington or else-

where," cannot be accepted at face

value.32 Such a view overlooked the

unqualified support McClellan received

from the influential Dennison.

Moreover, while Scott's telegram on May

24 may not have issued instructions

per se, it seems clear that McClellan

was expected to take such action as he

deemed necessary "to counteract the

influence of that detachment," located

one hundred miles from the Ohio River,

the exact size of which had not been

clearly determined. Conversely, Scott

appeared to be hedging throughout

as if he were attempting to avoid direct

responsibility if McClellan met

defeat or if an invasion proved to be

premature politically. Scott's fears

of possible political repercussions from

military intervention were as un-

founded as McClellan's later estimates

of Confederate military strength

were exaggerated.

McClellan arrived in Grafton on June 21

to take personal command of

operations against Garnett. He met with

unbridled enthusiasm all along his

route. Describing his reception, he

wrote to his wife:

At every station where we stopped crowds

had assembled to see the "young

general": gray-headed men and

women, mothers holding up their children to

take my hand, girls, boys, all sorts,

cheering and crying, God bless you! I

never went through such a scene in my

life.33

To his troops McClellan announced his

arrival in more dramatic style.

"Soldiers!" he wrote, "I

have heard that there was danger here. I have

come to place myself at your head and to

share it with you. I fear now but

one thing--that you will not find foemen

worthy of your steel."34 But Mc-

Clellan revealed a different attitude

when he wrote to Lieutenant Colonel

E. D. Townsend, the assistant adjutant

general, in Washington:

Assure the General [Winfield Scott] that

no prospect of a brilliant victory

shall induce me to depart from my

intention of gaining success by maneuvering

rather than by fighting. I will not

throw these raw men of mine into the teeth

of artillery and intrenchments if it is

possible to avoid it. Say to the General,

too, that I am trying to follow a lesson

long ago learned from him; i.e., not to

move until I know that everything is

ready, and then to move with the utmost

rapidity and energy.35

92 OHIO HISTORY

McClellan wrote this letter from

Buckhannon, "the important strategical

position in this region," from

which he would launch his attack against the

Confederate forces under Lieutenant

Colonel John Pegram at Rich Moun-

tain. Pegram had about 1,300 men, while

Garnett and the main body of

troops, composed of about 3,000 men, was

entrenched about twelve miles

north at Laurel Mountain. "I shall,

if possible," McClellan said to Town-

send, "turn the position to the

south, and thus occupy the Beverly road in

his [the enemy's] rear."36

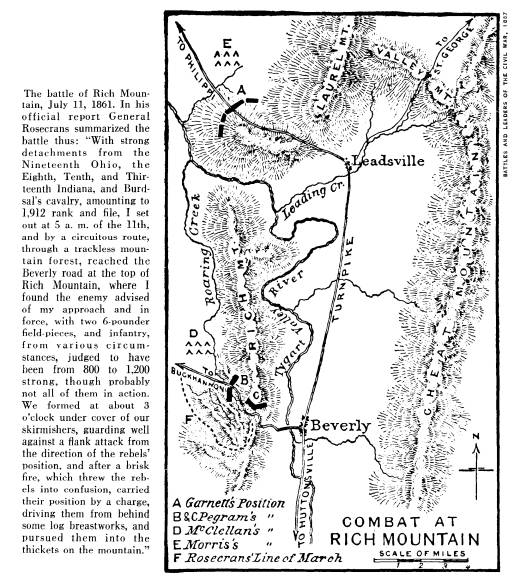

McClellan planned his strategy with

precision. While concentrating about

8,000 men at Buckhannon for the main

attack on Pegram, he left 4,000 men

at Philippi under Brigadier General

Morris, whose major function lay in

"amusing the enemy" on Laurel.37

Moreover, McClellan had a large number

of troops concentrated at several other

points--including Weston, Clarks-

burg, Bulltown, and Grafton--which could

be called upon as exigencies

demanded. In addition, he ordered

Brigadier General Jacob D. Cox to the

Kanawha Valley with four full regiments

to dislodge Brigadier General

Henry A. Wise, who arrived in Charleston

on July 6. Wise's "Legion,"

composed of 2,700 raw militia troops,

was ordered to hold the Kanawha

region.38 Yet, McClellan

believed, and rightly so, that Garnett would

attempt to use Wise's command as a

diversionary force. If Wise could

threaten McClellan's rear, Garnett

reasoned, "the enemy would have to draw

from his force in my front to meet

him."39 Wise was eliminated as a poten-

tial threat, however, by Cox's

appearance on July 10 and by the swiftness

of McClellan's movements against Pegram.

Lee was not able to send

Garnett's urgent request on to Wise

until July 11, the same day that

Confederate hopes of holding the

northwest were destroyed by Pegram's

crushing defeat at Rich Mountain.40

Clearly perceiving that he would suffer

heavy losses if he stormed the

heavily entrenched western slope of

Rich, McClellan dispatched Rosecrans'

brigade of four regiments on a flanking

maneuver.41 Rosecrans was in luck.

A young Virginian by the name of David

Hart led Rosecrans to the summit

of Rich on Pegram's left flank by way of

an unguarded mountain trail. A

small force of three hundred

Confederates delayed the verdict for three

hours; but Pegram's doom was sealed.

Gathering the remnants of his com-

mand, a group of bewildered and

terror-stricken men, Pegram tried to make

his way "over the mountains, where

there was not the sign of a path, toward

General Garnett's camp."42 Convinced

of the futility of flight on learning

the next day that Garnett had abandoned

Laurel Mountain, there was

nothing left for Pegram "but the

sad determination of surrendering ourselves

prisoners of war to the enemy at

Beverly."43

|

|

|

As McClellan had hoped, Garnett found his position at Laurel untenable. As soon as the issue at Rich had been decided, McClellan "advanced . . . on Beverly and occupied it with the least possible delay--thus cutting off Garnett's retreat toward Huttonsville and forcing him to take the Leadsville and St. George road."44 With Morris in close pursuit, McClellan then wired Brigadier General C. W. Hill at Grafton to cut off his retreat.45 Garnett's capture seemed inevitable. As one Union officer expressed it, "Between 2,500 and 3,000 of a defeated army, in a disorganized condition, were in a position where escape did not come within the chances of war."46 Garnett himself was killed in a rear guard action at Carrick's Ford; but incredibly, |

94 OHIO HISTORY

the main body of his army escaped. Even

though it was twenty-five miles

from Carrick's Ford to the nearest pass

through the Alleghenies at Red

House, Garnett's command arrived at this

place two hours ahead of Union

troops and made good its escape. Two

major factors were responsible: a

delay in the transmission of McClellan's

telegram to Hill, and Hill's lack

of knowledge of the mountainous terrain,

which led him to conclude that

Garnett's line of retreat would be north

instead of east.47 Even so, Mc-

Clellan's victory was total.

The scene of action in western Virginia

then shifted to the Kanawha

Valley. Cox arrived at Point Pleasant on

July 10 and immediately began an

advance on Charleston.48 On

the afternoon of July 17 his advance guard of

1,200 men encountered 800 Confederates

from Wise's Legion at Scary

Creek, fifteen miles west of Charleston.

Although Cox was repulsed, the

battle at Scary was little more than a

delaying action.49 In light of Garnett's

crushing defeat in the northwest, Lee

ordered Wise to abandon the Kanawha

and withdraw towards Covington to

protect the Virginia Central Railroad.50

On learning that Cox had been checked at

Scary, McClellan planned to

take personal command of military

operations in the Kanawha Valley.51

But on July 22, the day after the

federal disaster at First Manassas, the

"Young Napoleon" was ordered

to Washington. In western Virginia he

was succeeded by the hero of Rich

Mountain, William S. Rosecrans. Cox,

however, continued his advance. On July

25 he entered Charleston; and

on July 29 he occupied Gauley Bridge,

the gateway to the Kanawha Valley

from the east.52 For all

practical purposes, the campaign in western

Virginia, if not over, had been won

beyond recall. Yet the northwest was

too great a prize to surrender without

an attempt being made to recover it.

In mid-August General Robert E. Lee,

accompanied by a force of 15,000

troops, arrived in the valley of

Virginia. Lee's first objective was to regain

the passes through the Alleghenies at

Laurel, Cheat, and Rich mountains.

Offensive operations in the northwest

would then be possible. On September

12 Lee launched an attack against the

federal troops at Cheat Mountain

near Huttonsville. But a combination of

factors, including mud, rain, sick-

ness, and bungling on the part of his

subordinates, conspired to make Lee's

debut as a field general a failure.53

The Confederates also made an

unsuccessful attempt to reconquer the

Kanawha Valley. Brigadier General John

Floyd, secretary of war under

Buchanan and an ex-governor of Virginia,

had raised a force of about 1,200

men in the southwest to protect the

Virginia and Tennessee Railroad.

Soon after Wise evacuated the Kanawha

region, Floyd was elevated to the

command of the army of the Kanawha. Wise

and his legion were ordered

WESTERN VIRGINIA CAMPAIGN OF 1861 95

to support Floyd. If any degree of

success were to be achieved, close coop-

eration between these two political

generals was imperative. Their personal

relations, however, were marked by

extreme bitterness. Henry Mason

Mathews, a representative in the

legislature from the region, wrote to Jeffer-

son Davis urging him to intervene.

"They are as inimical to each other as

men can be," he said, "and

from their course and actions I am fully satis-

fied that each of them would be highly

gratified to see the other annihi-

lated."54 Finally, on

September 21, a dispatch was sent to Wise relieving

him of command and ordering him back to

Richmond.55

Floyd did manage to win a skirmish at

Cross Lanes on August 26.56 And

he repulsed Rosecrans at the battle of

Carnifex Ferry on September 10. Yet,

in all probability, Floyd's army would

have been destroyed if Rosecrans

had pressed the issue.57 In

any event, neither Lee nor Floyd was in a

position to challenge federal supremacy

in northwestern Virginia. With the

exception of the brief reoccupation of

the Kanawha region by Major

General William W. Loring in September

of 1862, Union supremacy was

not challenged.58 Even

Loring's brief success came by default. Most federal

troops were withdrawn from western

Virginia when Lee moved north.

Union soldiers returned in force,

however, after the battles of South Moun-

tain and Antietam.59

The most obvious result of McClellan's

conquest of northwestern Virginia

was that it propelled the "Young

Napoleon" into the national limelight and

the command of the army of the Potomac.

Moreover, his mountain campaign

provided a psychological cushion for a

nation and an army that were shaken

by defeat at the first encounter at

Manassas. The strategic importance

of northwestern Virginia to the Union

cause, however, has not been appreci-

ated by most students of the Civil War.60

Northwestern Virginia served first of

all as a buffer zone for the states

of Ohio and Pennsylvania, a protective

covering for Pittsburgh and the

Ohio Valley. It also covered the western

flank of any Union army operating

in the Shenandoah Valley. In addition,

the line of the Baltimore and Ohio

ran through northwestern Virginia--a

railroad of great strategic importance

which provided the only connecting link

by rail between Washington and

the Middle West. The seizure of the

Baltimore and Ohio virtually intact

largely accounts for the rapidity with

which the northwest was conquered in

the first place. Finally, whether or not

Union occupation of northwestern

Virginia was a prime factor in

preserving Kentucky for the Union, the im-

portance of federal supremacy in both

areas in paving the way for the

occupation of eastern Tennessee can

hardly be exaggerated.61

It should be stressed also that

McClellan's invasion of northwestern Vir-

96 OHIO

HISTORY

ginia established the authority of the

Reorganized Government of Virginia

under Francis H. Pierpont, Union war

governor of the Old Dominion; and

it made a separate-state movement in

(West) Virginia possible. After

Garnett's defeat at Rich Mountain and

Wise's withdrawal from the Kanawha

Valley, northwestern Virginia no longer

was in danger of falling under the

control of a Confederate army of occupation.

But in view of the divided

loyalties of the inhabitants of western

Virginia and the persistence of

guerilla warfare in this region until

1865, it is clear that a liberal dose of

force was one of the prime ingredients

used by northwestern Unionists in

their magic formula for state-making.

In truth, West Virginia was a war-

born state.

THE AUTHOR: Richard O. Curry is a

visiting assistant professor of history

at the

University of Pittsburgh. His doctoral

dis-

sertation was a study of statehood

politics in

West Virginia.