Ohio History Journal

JAMES E. HANEY

Blacks and the Republican

Nomination of 1908

Theodore Roosevelt's decision not to

seek the Republican presidential nomina-

tion in 1908 left the field open to

several Republican hopefuls, but his influence in

the party and control of its machinery

made it clear that the candidate he sup-

ported would win the nomination as well

as the national election that followed.

This was especially important when it is

remembered that national politics dur-

ing the first decade of the twentieth

century was dominated by the Republican

party. As a minority party, the

Democrats offered the American people only sec-

tional candidates with little or no

national appeal.

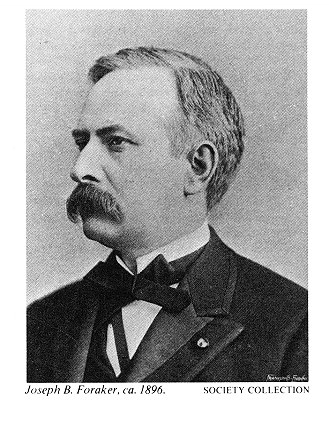

There were several Republicans whose

national reputations and positions on

the major issues of the day caused

Roosevelt to consider them as serious con-

tenders for the party's nomination in

1908. The leading contenders were Charles

E. Hughes, governor of New York, and two

members of the Cabinet, Secretary

of State Elihu Root and Secretary of War

William H. Taft. Hughes, Root, and

Taft were followed by Senator Joseph B.

Foraker of Ohio whose presidential

ambitions were on the rise with the

approach of the party's national convention in

June.

Hughes, one of the leading reform

governors of the nation, first gained na-

tional attention in 1905 as counsel for

the "Armstrong Committee," a legislative

committee of the New York State Senate

investigating insurance and related

frauds. Partly as a result of the diligent

work he performed as counsel, the As-

sembly passed a number of laws which

extended greater protection to insurance

policy holders, attempted to prohibit

corporations from making political contribu-

tions and influencing the outcome of

elections, and curtailed the activities of

lobbyists and special interest groups.

More important for the nomination in 1908,

however, was the fact that Hughes was

able to parlay his role in these investiga-

tions into a victory over the New York

Republican machine of Benjamin Odell

for the party's gubernatorial nomination

in 1906. As a candidate for governor,

Hughes had the support of the national

administration; President Roosevelt sent

Secretary Root to Utica to deliver an

address in Hughes' behalf which some his-

torians contend played an important role

in the outcome of the election.1

Although he had helped to elect Hughes

governor of New York in 1906, Roose-

velt felt he would not make a good

presidential candidate and could not compare

1. Harold Gosnell, Boss Platt and His New York Machine; A Study of the Political Leadership of

Thomas C. Platt, Theodore Roosevelt, and Others (New York, 1924), 277-284; Philip C. Jessup,

Elihu Root, 2 vols.

(New York, 1938),

118-123.

Dr. Haney is Assistant

Professor of History at Vanderbilt University.

|

208 OHIO HISTORY |

|

|

|

with Root or Taft "either morally, intellectually, or in knowledge of public poli- cies." Roosevelt believed that the best course to pursue in reference to Hughes' political ambitions was to help reelect him as governor in 1908. He might be de- feated by the Democrats, the President confided in a friend, "but whether he is beaten or not, his nomination will strengthen the national ticket, not only in New York, but in a good many other states as well."2 Roosevelt further believed that if the New York machine nominated someone else, a person not identified with reform, it would have a bad effect on the national ticket and might undermine his attempt to get progressive reform measures through Congress. It also appears Roosevelt wished to intervene in New York on Hughes' behalf more out of con- tempt for the "bosses" than out of respect for Hughes as a reformer. Roosevelt believed he would be helping to undermine the same gang of machine politicians who had opposed his own programs during his governorship of the state in 1899.3 Unlike Hughes, Senator Foraker numbered among the President's enemies. He was therefore considered a long shot for the nomination by the many blacks who supported him in appreciation of his defense of the 167 black soldiers of the

2. Theodore Roosevelt to "Athos" [Elihu Root], Washington, August 15, 1908, Jessup, Elihu Root, II, 128. 3. Hughes' reform candidacy was opposed by the New York Republican machine of Thomas C. Platt. While Roosevelt was governor, Platt opposed his efforts at civil service reform and reform of the state's penal code. Platt was also behind the move to have Roosevelt selected by the Republican party as McKinley's Vice-President in 1900 in the belief that he was helping to bury him politically as well as helping to diminish his influence in New York politics. For more on the various disagree- ments between Roosevelt and Platt, see Henry F. Pringle, Theodore Roosevelt: A Biography (New York, 1931), 53, 94, 105, 118, 145-146. |

Blacks and Republicans

209

25th Infantry whom Roosevelt had

dishonorably discharged in November 1906,

for their alleged involvement in a

disturbance in Brownsville, Texas. The en-

suing controversy between the two men

over what became known as the "Browns-

ville Affair" made it unlikely that

Roosevelt would endorse Foraker for the nomi-

nation. He believed Foraker had little

or no moral scruples and was simply play-

ing the Brownsville incident for its

sensationalism and the mileage he could get

out of it for the nomination in 1908.

Roosevelt's energies before the convention in

June were directed more at trying to

keep Foraker from receiving the nomination

than they were in having his own man

selected. Despite this, Foraker's candidacy

remained strong, especially among blacks

who regarded him as their agent in

repudiating Roosevelt's summary

dismissal of their soldiers.4

With Hughes and Foraker eliminated as

candidates he could possibly support

for the nomination, Roosevelt's choice

boiled down to Root or Taft. Root, he be-

lieved, would make the best President,

but Taft the best candidate.5 While Root

might have been his first choice for the

nomination, Roosevelt was convinced, as

was Root, that he would make a poor

candidate because of his image as a "Wall

Street Lawyer." His candidacy, the

President feared, would not be acceptable

to many Republicans in the West who were

injured in the general economic re-

cession of 1907.6 Taft, like Root,

supported Roosevelt's policies but was less than

enthusiastic about the prospects of

seeking the nomination. Contending that he

was not a politician in the traditional

sense of wishing to become President, he

said he wanted to avoid the rough and

tumble of convention politics and longed

to retire to "a contemplative

position," perhaps as a member of the Supreme

Court (a position he would later hold)

after his tenure in the War Department.7

Taft was unduly modest. It was generally

known after 1906 that President

Roosevelt was grooming him as his

successor, although he received no "absolute

commitments" from the President to

that effect until May of that year. This oc-

curred following a long conversation at

the White House on the party's prospects

in 1908. After his talk with Roosevelt

the secretary wrote his wife that during

their interview he had found Roosevelt

"full of the presidency and wanted to talk

about my chances." He went on to

delight her by noting Roosevelt thought he was

the one "to take his mantle"

and believed he could be nominated and elected

with few difficulties.8

After Roosevelt decided on Taft as his

successor, arrangements were made to

increase his support in the South. Both

men knew an important ingredient in win-

ning the nomination was the control of

the Southern delegations from the eleven

former Confederate states that attended

the national convention. These states

at times controlled as many as one-third

of the votes necessary for a victory in

the convention. Since the disputed

Hayes-Tilden election in 1876, when the Re-

publican party agreed to an official end

of Reconstruction in the South, almost all

Republican presidential hopefuls wrote

off the South as far as its support in the

national election was concerned,

conceding the entire section to what was de-

veloping into a "solid South"

where the Democrats controlled practically the

4. Cleveland

Gazette, December 8, 15, 29, 1906, January 19, 26, March 9, 16,

April 13, 20, 1907.

5. Jessup, Elihu Root, II, 123.

President Roosevelt was quoted as saying that if he "had the power

of a dictator he would appoint Elihu

Root President, and Secretary of War Taft as Chief Justice of

the Supreme Court." Herman H.

Kohlsatt, From McKinley to Harding: Personal Recollections of Our

Presidents (New York,

1923), 161-162.

6. Jessup, Elihu Root, 11,

123.

7. Henry F. Pringle, The Life and Times of William H.

Taft, 2 vols. (New

York, 1939), 1, 337, 342;

Kohlsatt, From McKinley to Harding, 161-162.

8. William H. Taft to Mrs. Taft,

Washington, May 4. 1906, Jessup, Elihu Root, 11, 123; Kohlsatt,

From McKinley to Harding, 161-162.

210 OHIO

HISTORY

entire Congressional delegations to

Washington by the turn of the century. Never-

theless, they all recognized that, while

they stood a chance of winning the na-

tional election without carrying a

single Southern state, they could not win the

Republican nomination without strong

support from the South in their national

convention.

It was the realization of this political

peculiarity that prompted Taft to write in

one of his letters after he admitted his

candidacy "that the South has been the

section of rotten boroughs in Republican

politics," and it would be a delight to

him "if no Southern state were

permitted to have a vote in the national conven-

tion except in proportion to its

Republican vote in national elections." But, he

quickly added, "when a man is

running for the Presidency...he cannot ignore the

tremendous influence, however undue,

that the Southern vote has and he must

take the best way he can honorably to

secure it."9 It was also the realization of

the "tremendous influence" the

South had in the national convention that

prompted Roosevelt to persuade Frank H.

Hitchcock, First Assistant Postmaster

General and specialist in the management

of Southern delegations, to resign his

position and work full time in the

interest of Taft's candidacy in the South.10

In the meantime, Taft was doing his best

to encourage his own candidacy in

the South. In August 1906, he made his

first public appeal for Southern support

when he went to North Carolina to

address a session of the state legislature at

Greensboro. The national press billed

the address as his "keynote" for the Re-

publican nomination. Although addressing

a Democratic legislature, he directed

most of his attention to the

"lilywhite" Republican sentiment that was rapidly

spreading throughout the Republican

party in the South. Lilywhite Republicans

were those Republicans who had

cooperated with blacks before the latter were

disfranchised in the various Southern

states, but after that event, were willing to

join hands with Southern Democrats who

sought to remove blacks from all po-

sitions of influence in Southern

politics. Such Republicans were frequently desig-

nated "lilywhites," especially

by black newspaper editors, to distinguish them

from "White Republicans" who

stood on the same platform of black political

rights as William Lloyd Garrison,

Abraham Lincoln, and Charles Sumner. The

lilywhites' influence grew stronger in North

Carolina following the constitutional

disfranchisement of more than ninety per

cent of the state's black voters in 1901.

Some lilywhite Republicans in North

Carolina, like those in several other

Southern states where the black voters

were constitutionally disfranchised by

1906 (Mississippi, South Carolina,

Louisiana, and Alabama) favored removing

the remaining small percentages of black

voters who still met the suffrage re-

quirements; but most were concerned only

with eliminating those influential

black political leaders scattered

throughout the state, many of whom had received

presidential appointments for their

active support of the party throughout the

North following the general

disfranchisement of their people. All who supported

the doctrine of "lilywhitism"

agreed that in order for the Republican party to at-

tract more white independent and

Democratic support, in the words of one, "the

Negro must go."11

In his address to the North Carolina

legislature, Taft took a position on black

suffrage and on the place of the race in

Southern politics that was designed to

9. Taft to W. R. Nelson, Washington,

January 18, 1908, Pringle, The Life and Times of William H.

Taft, 1, 347.

10. George H. Mayer, The Republican

Party, 1854-1964 (New York, 1964), 301; Pringle, The Life

and Times of William H. Taft, I, 347.

11. John R. Lynch, The Facts of

Reconstruction (New York, 1970), 239-323; Washington Bee,

July 4, 28, 1906; Cleveland Gazette, September

1, 1905; Adams to Roosevelt, July 12, 1906, Theodore

Roosevelt Manuscript Collection, Library

of Congress. Hereafter cited as Roosevelt Papers.

Blacks and Republicans 211

please North Carolina lilywhite

Republicans. Perhaps he hoped to give encour-

agement to those in Georgia who were

working closely with the Democrats to

disfranchise black voters. While Taft

did not support black disfranchisement

through the various frauds perpetrated

by the disfranchisement constitutions-

he said that he favored a restricted

franchise where the educated and property

holding portion of the race would be

allowed to vote-he believed their suffrage

would have to be protected through

judicial action on the part of the Supreme

Court rather than through any

legislative action that might be initiated by Con-

gress.12 This position placed

him in opposition to such earlier efforts as the de-

feated Lodge Federal Election, or

"Force Bill," of 1890 where the Republican

party made its last serious attempt to

enforce black suffrage in the South through

the use of federal police to protect

those who were driven from the polls by fraud,

intimidation, or violence. In addition,

many believed the Secretary's position on

black suffrage in the South meant he

would not insist on enforcing section two

of the Fourteenth Amendment should he

become President. This section required

Congress to reduce the representation in

the House of those states that reduced

their voting rolls by disfranchising any

portion of their citizens.13

In addition to his views on black

suffrage and his attitude toward the enforce-

ment of the Fourteenth Amendment, Taft's

part in the Brownsville Affair also

enhanced his popularity among a large

number of Southern Republicans since

Roosevelt's dismissal order and the War

Department's issuance of the order

caused many to link their names when

they discussed the incident. In all fairness

to Taft, however, it must be noted that

he did not initially approve of the order

and had tried to get the President to

modify or withdraw it before it was made

public.14

But when Roosevelt insisted on removing

the soldiers from the army, Taft sup-

ported the decision through many of his

letters and public utterances on the sub-

ject, declaring on one occasion that he

believed the order "was fully sustained by

the facts."15 When

Foraker's Senate Investigating Committee on Brownsville

issued its Minority Report on the Affair

in April 1908, which criticized the lack of

concrete evidence used by the President

and the War Department in dismissing

the soldiers, it was Taft who suggested

that Roosevelt send a special team of pri-

vate investigators, at a cost of $1500,

to Brownsville to seek out "additional evi-

dence" that might be used to prove

a stronger link between the soldiers and the

Brownsville disturbance.16

If Taft's views on black suffrage, the

reduction of Southern representation in

the House, and the Brownsville Affair

made his candidacy popular among many

Southern Republicans, these same views

caused many black Republicans in the

North, especially those in Ohio,

Massachusetts, and New York, to oppose his

selection as the party's nominee. Black

opposition to his nomination was strong-

est among black newspapers such as the Cleveland

Gazette, the New York Age,

and the Boston Guardian, all of

which supported Foraker because of his Browns-

ville stand in defense of the 25th

Infantry. These newspapers and their editors

12. Cleveland Gazette, July 21,

1906, New York Age, July 12, 1906.

13. Washington Bee, July 4, 28,

1906; Cleveland Gazette, September 1, March 25. 1905, July 21.

1906.

14. Washington Bee, November

10, December 17, 1906, Cleveland Gazette, July 21, November

21, 1906, January 12, 19, March 9, 16,

30, 1907.

15. Taft to Roosevelt, Washington, July

7, 1907; Pringle, The Life and Times of

William H. Taft,

1, 327.

16. Joseph B. Foraker, Notes of a Busy Life, 2 vols.

(Cincinnati, 1917), II, 246; Everett Walters,

Joseph Benson Foraker: An

Uncompromising Republican (Columbus, 1948), 244; James A. Tinsley.

"Roosevelt, Foraker, and the

Brownsville Affray," Journal of Negro History, LV (1956), 43-44.

212 OHIO HISTORY

were joined in their opposition by a

number of black protest organizations, in-

cluding the Niagara Movement, the

Afro-American League, and the Boston Con-

stitutional League.

The earliest opposition to Taft came

from the Niagara Movement, a black pro-

test movement organized in 1905 by W. E.

B. DuBois, who, after the 1903 publi-

cation of his Souls of Black Folk, became

one of the most persistent critics among

black leaders of the Republican party's

attitude toward his race's constitutional

rights. DuBois was also critical of the

national leadership of Booker T. Washing-

ton whom he charged was willing to

compromise black civil and political rights

for the advancement of his own

ideological or personal position within the country

and party. Meeting in their third annual

session in Boston in September 1907,

DuBois and members of the Niagara

Movement addressed an appeal to the

"500,000 free black voters of the

North," giving them political directions in refer-

ence to the Republican nomination in

1908. They were told to work against Taft's

nomination or that of any other

"Brownsville Republican" who had supported

Roosevelt's dismissal of the soldiers.

Should one of these win the nomination, the

appeal continued, then blacks should

work against their candidacy during the

election, even if it meant a Democratic

victory. This position supported DuBois'

contention that an avowed enemy of the

race was better than a false friend.17

Several leaders of the Niagara Movement

continued their organization's oppo-

sition to Taft after their annual

session in Boston. The Reverend Reverdy Ran-

som of New York, editor of the A.M.E.

Church Review, denounced Roosevelt's

economic policies and warned his people

against Taft in an address in 1908.

Speaking before a large gathering in

Philadelphia, Ransom accused Roosevelt of

allowing blacks and poor people to

suffer during the economic recession of 1907,

stating that because of Roosevelt's

economic policies, "starvation stood in the

door of every man and conditions would

be no better if Taft were elected in his

place."18 This same

theme was echoed in Boston where William M. Trotter, edi-

tor of the Boston Guardian and

one of the founders of the Niagara Movement,

led the way in organizing the National

Negro American Political League to op-

pose Taft's nomination and election in 1908.19

Finally, in Taft's own home state of

Ohio black Republicans of Cleveland or-

ganized the Ohio branch of the

Afro-American Council. This organization best

summarized the race's opposition to Taft

as the party's nominee when it included

as one of the first items on its agenda

a petition to be circulated among the city's

black population and carried to the

convention in Chicago. The petition opposed

Taft because of his Greensboro address

dealing with black suffrage and the re-

duction of Southern representation and

because of some of his public statements

on Brownsville where he accused the

soldiers of being guilty before they were

tried in court. It called upon blacks in

Ohio and throughout the nation to join the

League in its efforts to defeat Taft or

any other Republican whom Roosevelt sup-

ported for the nomination.20

The opposition to Taft's selection by

black newspapers and protest organiza-

tions prompted President Roosevelt to

resort to a familiar Republican tactic of

giving a few black politicians a

presidential appointment in order to bring the

race back into its traditional alliance

with the Republican party. While there were

17. Chicago Broad Ax, September

7, 1907; Baltimore Afro-American, September 15, 1907; see also

Elliott M. Rudwick, W. E. B. DuBois:

Propagandist of the Negro Protest (New York, 1969), 102-103.

18. New York Age, February 20,

1908.

19. Boston Guardian, April 11,

1908; Washington Bee, April 11, June 13, 1908; see also Stephen

R. Fox, The Guardian of Boston:

William M. Trotter (New York, 1971), 110-112.

20. Cleveland Gazette, April 18,

1908.

Blacks and Republicans 213

several instances of Roosevelt's use of

this tactic during his first administration,21

the best illustration in the controversy

surrounding Taft's nomination occurred

over the appointment of a black in Ohio,

the home state of both Foraker and Taft

where black opposition to the

Brownsville decision was perhaps the strongest.

In addition to using his power of

appointment to influence black public opinion in

Taft's favor, Roosevelt also attempted

to strike at Senator Foraker for his oppo-

sition to the dismissal of the 25th

Infantry.

Several days after he delivered his

message to Congress on the Brownsville

Affair--where he justified his

constitutional authority and defended his moral

position in dismissing the

soldiers--Roosevelt wrote Booker T. Washington, the

famous black educator of Tuskegee

Institute in Alabama. Washington had served

as one of his advisors on black

patronage since the controversial Washington-

Roosevelt White House Dinner in October,

1901.22 The President requested from

him "the names of two or three

first-class men in Ohio, men who were good Re-

publicans, in addition to men of the

highest character who would be up to the

standards of an Internal Revenue

Collector" in the state. He was explicit in ref-

erence to the location of the proposed

appointment, instructing Washington to

send him the name of "a first-class

colored man from Cincinnati,"23 the home

and political base of both Foraker and

Taft.

For the prospective appointment in

Cincinnati, Washington recommended

Ralph W. Tyler, a journalist from

Columbus who had more than twenty years

of work as a newspaper correspondent,

including some work on two of the white

dailies of Columbus, the Columbus

Dispatch and the Ohio State Journal. Wash-

ington arranged an interview at the

White House for Tyler that was attended by

Roosevelt and his Private Secretary,

William Loeb.24 During the interview the

President asked Tyler, as he had asked

Washington, for the names of two black

applicants besides himself whom he could

nominate and expect the Senate to

confirm as Collector of the Port of

Cincinnati. Tyler hesitated before answering,

insisting that the President should not

think of nominating any of the black poli-

ticians from Cincinnati for the position

since the loyalty of most of them toward

his administration could be questioned.

Most of them, he said, were closely con-

nected with Foraker and, for the most

part, had supported him on Brownsville.

Roosevelt next wanted to know whether

the two Senators from the state, For-

aker and Charles Dick of Akron, would

support Tyler's confirmation in the Sen-

ate if he were nominated as Collector of

Cincinnati. Realizing that one of the pur-

poses for appointing a black man in

Cincinnati was to undercut Foraker's grow-

ing appeal to many blacks in Ohio,25

Tyler replied that while he felt he could get

Senator Dick's endorsement for a

position in Cincinnati or Washington, he would

21. Roosevelt used his power of

appointment during his first administration to bring blacks around

to support the Republican party in

several states including Mississippi, Georgia, Louisiana, North

Carolina, and South Carolina. For

additional information see Booker T. Washington to Roosevelt,

November 6, 1901, Roosevelt Papers; J.

A. Smythe to George B. Cortelyou, November 10, 1902, E. J.

Scott to W. D. Crum, April 21, 1904,

Washington to Charles Anderson, December 23, 1904, Booker T.

Washington Manuscript Collection,

Library of Congress. Hereafter cited as Washington Papers.

Washington Bee, January 8, 1905; New York Age, March 9,

16, 30, 1905.

22. When Roosevelt became President

after McKinley's assassination in September 1901, he in-

vited Washington to the White House for

consultation on various social and political matters in the

South. During their meeting, lunch was

served and the President's detractors said that the visit and

lunch were part of an effort by

Roosevelt to encourage social equality between the races. Booker T.

Washington, My Larger Education:

Being Chapters From My Experiences (New York, 1911), 170-

171, 174-178: Roosevelt to Washington,

September 14, 1901, Roosevelt Papers.

23. Roosevelt to Washington, December

25, 1906, Roosevelt Papers.

24. Ralph W. Tyler to Washington,

February 4, 1907, Washington Papers.

25. Tyler to

Washington, February 4, 1907, Washington Papers.

214 OHIO

HISTORY

not seek Foraker's, although he was

certain that Foraker would be less likely to

oppose him for the position than any

other black man the President might nomi-

nate. Roosevelt was evidently impressed

with Tyler's answers for as the interview

drew to a close he turned to Loeb and

said, "Mr. Loeb, I believe we will try to put

it through with Mr. Tyler." But

first, he wanted to check with his son-in-law,

Representative Nicholas Longworth of

Cincinnati, before he acted on the nomi-

nation.26

Tyler left the White House and went

directly to the House of Representatives

to confer with Longworth on the expected

appointment. When he informed him

of the interview with Roosevelt and the

possibilities he would be made Collector

of the Port in Cincinnati, Longworth

expressed surprise, which later changed to

bitter disappointment, that Roosevelt

was thinking of naming a black man to one

of the most influential patronage

positions in his district, giving Tyler a fore-

warning that he would oppose his

selection.27

On his return to Columbus, Tyler wrote

to Washington at Tuskegee to bring

him up to date on his interview with

Roosevelt and Loeb as well as his talk with

Longworth. He told Washington the

President had been impressed with his an-

swers to a number of questions he had

asked and that he believed Roosevelt was

ready to make the announcement of his

appointment. But Tyler doubted that

Longworth would be willing to go along

with the President's choice, or the se-

lection of any black man for that

matter, without raising strong objections that

could jeopardize the nomination in the

Senate. Tyler felt that Longworth's pos-

sible objection could be overcome by

Washington's influence and friendship with

Roosevelt, and he requested the educator

"to make a simple phone call to the

President or Secretary Loeb,"

saying that Tyler was the man for the job and

should be nominated without delay.28

Washington did not think it wise or ex-

pedient to make such a phone call. He

wrote Tyler that even if Longworth op-

posed his appointment, or the

appointment of any other black man in his district,

Roosevelt would still have to make a

black appointment from the state to show

the race he was not hostile to their

constitutional rights as some of the black news-

papers in Cleveland and other cities in

Ohio were charging. Tyler, Washington

believed, was in the best position to

receive such an appointment.29

Meanwhile, further complications

concerning the appointment developed when

the Cincinnati Enquirer, a

newspaper owned and printed by Taft's family, ran a

story which said Roosevelt had intimated

to a confidential source that Foraker

would soon give him the name of a black

man for an important presidential po-

sition in Ohio, without specifying the

Collector's office in Cincinnati. According

to the story, if Roosevelt and Foraker

compromised their differences on Browns-

ville, there was a strong possibility

that Tyler would not be given the Cincinnati

post since it was believed Foraker

favored another black man for the job. Tyler

sent a copy of the story to Washington,

but the attempt at a compromise between

Roosevelt and Foraker on Brownsville-if

there was ever a compromise in the

making-never matured. Roosevelt put a

damper on the story several days after

it appeared by informing Washington he

"meant to stand by Tyler" for the Col-

lectorship, but said he was having

difficulties and might be forced "to stand by

somebody in Toledo for geographical

reasons." It did indeed appear that the

President intended to "stand by

Tyler" for he wrote Washington the following

26. Tyler to Washington, February 4,

1907, Washington Papers.

27. Washington to Anderson, January 14,

1907, Washington Papers.

28. Tyler to Washington, February 4,

1907, Washington Papers.

29. Washington to Anderson, January 14,

1907, Washington Papers.

Blacks and Republicans 215

week that he would send Tyler's name to

the Senate as Collector of the Port of

Cincinnati as soon as the term of the

white incumbent expired.30

While Roosevelt believed Tyler's

appointment as Collector was one way to in-

fluence black Republicans in Ohio and

bring them back into their traditional

alliance with the party, he also

believed this nomination, or the nomination of

any black man to such an important

patronage position, could stir up strong anti-

black sentiment throughout the state,

especially if white Republicans in Cincin-

nati opposed the appointment. As a

matter of fact, Roosevelt remembered that

one of the greatest controversies on the

race issue during his administration con-

cerned the nomination of a black man,

Dr. William D. Crum, as Collector of the

Port of Charleston. White Republicans in

the state were able to block Senate

confirmation of Crum's nomination for

more than three years.31 With this in mind

Roosevelt let the story out of the White

House that he was considering Tyler for

the Collectorship as a feeler to see how

white Republicans of Cincinnati would

react.32

The President was correct in his belief

that many white Republicans in Cin-

cinnati would react violently to the

nomination of a black man to the Collector-

ship. When they heard he was thinking of

making Tyler Collector, many reacted

not unlike those in Charleston who had

opposed Crum's confirmation in 1902.

In addition to being bitter over the

fact that a black man was to be given a post

envied by many politicians in the city,

some also complained that Roosevelt was

playing politics with the Collector's office;

that Tyler was not from Cincinnati and

would not be familiar with the people

with whom he would have to work as Col-

lector. A small group went so far as to

vow that if the President nominated Tyler

or any other black man for the

Collectorship they would not support Longworth

when he sought reelection to the House

in 1908.33

By this time Foraker was aware of

Roosevelt's plans in his home town, and he

attempted to counter them before the

President could send Tyler's name to the

Senate for confirmation. Working through

one of his black lieutenants in Cin-

cinnati, Robert J. Harlan, he encouraged

several other blacks in the city to file

for the position, "thereby bringing

discomfiture to the President and forcing him

to abandon Tyler," as one of

Washington's informers told him.34 Thus, after more

than seven months of trying to create

the proper conditions to appoint a black

man in Cincinnati, white opposition and

Foraker's maneuvering forced Roosevelt

to abandon Tyler and reappoint the white

incumbent when his term expired. After

considerable indecision he finally named

Tyler as the Fourth Auditor of the Navy

Department in Washington where he was

confirmed by the Senate in early 1907.35

Instead of regaining the support of Ohio

blacks for the party and Taft's nomi-

nation as Roosevelt had anticipated,

Tyler's appointment, even as Fourth Auditor

30. Washington to Tyler,

January 14, 28, 1907, Tyler to Washington, January 25, 1907,

Scott to

Tyler, January

29, 1907, Washington Papers.

31. James F. Rhodes to Roosevelt,

December 23, 1904, Roosevelt to Owen Wister, April 27, 1906,

Roosevelt Papers:

William D. Crum to Whitfield McKinlay, October 31, November 3,

1902. Carter

G. Woodson Collection, Library of Congress; August Meier, Negro Thought in America, 1880-1915;

Racial Ideologies in the Age of

Booker T. Washington (Ann Arbor, 1963), 164, 242.

32. New York Age, March 7,

1907.

33. Newspaper clippings in Washington's

Manuscript Collection from the Cleveland Plain Dealer

sent to Washington by Tyler,

February 9, 12, 16, 1907; see also Washington Bee, February

9, 16,

1907; New York Age, February 7,

1907.

34. Anderson to Washington,

February 4, 1907, Iyler to Washington, February 22, 1907, Washing-

ton Papers.

35. Washington to Roosevelt, April 11, 1907, Washington to Tyler, April 11, 1907, Tyler

to Wash-

ington, April 10, 1907, Washington

Papers.

216 OHIO

HISTORY

of the Navy in far-away Washington,

served only to intensify their opposition to

the administration, since most of them

believed with Harry Smith's Cleveland

Gazette that Tyler had been appointed "in an attempt to

off-set executive action

in the Brownsville Affair and to win

blacks for Taft in 1908."36 Smith's Gazette

was echoed by George Myers, the

influential black barber and political jobber of

the famous Hollander House in Cleveland.

When he heard President Roosevelt

had nominated Tyler as Auditor of the

Navy, Myers declared that "it would not

stop the onward march of the black

deluge against him and Taft in Ohio." Roose-

velt's actions in appointing Tyler,

Myers said, "were palatable plain to even the

most illiterate Hammite." Blacks in

Ohio and throughout the nation were for For-

aker, and there was little Roosevelt

could do to alter the fact. In Myers' opinion

Roosevelt had a difficult if not

impossible task before him if he wanted to convert

blacks from Foraker to Taft. Myers

further believed that Tyler would not be con-

firmed by the Senate, but if confirmed,

"would not help the administration against

Senator Foraker."37

Although events later proved Myers to be

mistaken about Tyler's cooperation

with the administration against

Foraker's nomination, Tyler had said as much

shortly after Washington arranged the

White House interview for him. In one of

his several letters to Myers on the

subject of federal patronage before he was

nominated as Auditor, and when it looked

as if he would not be named as Col-

lector, Tyler had rationalized his

position. He wrote Myers he was not enthusias-

tic about being appointed by Roosevelt

since he knew that if he were he would

"be expected to fight against

Senator Foraker." Under such circumstances, he

had written, "I will say to the

President that Senator Foraker is a friend...and I

was not appointed with any understanding

that I would fight against him."38

Later after Myers learned the Senate was

going to confirm him as Auditor he

wired Tyler and told him "not to

sell his birthright for a paltry political office"

and urged him to accept the Auditorship

only on condition that he would not

compromise his feelings for Senator

Foraker.39

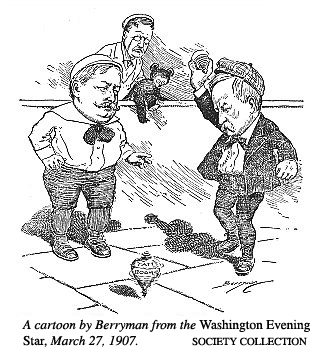

Meanwhile in March 1907, more than a

year before the national convention,

Foraker returned to Cincinnati where his

organization was waging a frenzied cam-

paign to capitalize on the growing

anti-Taft-Roosevelt-Brownsville sentiment that

was sweeping the state and threatening

to involve most Northern blacks. After

conferring with several of his more

influential supporters in Akron, Marion, and

Xenia,40 Foraker issued a

statement on his position in reference to the nomina-

tion. He said he would ask the Ohio

Republican Central Committee to meet in

Columbus within the immediate future to

issue a call for delegates for the na-

tional convention. The purpose was to

determine the state's choice for the nomi-

nation, himself or Secretary Taft.41

With Foraker's announcement of his candi-

dacy and calling for a session of the

state's Central Committee he was preparing

himself for a contest with Taft in their

home state to determine their respective

36. Cleveland Gazette, April 27,

June 8, 1907.

37. George A. Myers to Tyler, April 11,

12, 1907, George A. Myers Manuscript Collection, Ohio

Historical Society. Hereafter cited as

Myers Papers.

38. Tyler to Myers, April 13, 1907,

Myers Papers.

39. Myers to Tyler, April 12, 1907,

Myers Papers.

40. Among those consulted were Senator

Charles Dick of Akron, Chairman of the State Central

Committee, Warren G. Harding of Marion,

and L. C. Maxwell, a prominent black Republican in

Xenia; see also Anderson to Washington,

February 4, 1907, Tyler to Washington, February 4, 22,

1907, Washington Papers.

41. When the Committee assembled Taft

won the state's endorsement for the nomination by a vote

of fifteen to Foraker's six. William H.

Taft to Roosevelt, June 6, July 23, 1907, Arthur I. Vorys to Taft,

July 24, 1907, Roosevelt Papers.

|

Blacks and Republicans 217 |

|

|

|

strengths among Ohio Republicans in hopes of "bringing about a public con- frontation between the friends of the administration and its opponents."42 Foraker's declaration of his candidacy and the increased overtures his organi- zation was making to capitalize on the anti-Taft-Roosevelt-Brownsville senti- ment in Ohio, New York, and several other Northern states, not only helped to bring about a public confrontation "between the friends and supporters of the administration in Ohio," but it also created a great deal of concern among friends of the administration outside the state, especially Washington, Tyler, and their supporters.43 Since most of the support for Foraker's nomination and the oppo- sition to the administration on Brownsville came from black newspapers, which carried most of the news concerning the various protest meetings, Tyler's appoint- ment by the President and his newspaper experience fitted the administration's purpose of helping to influence black public opinion on Brownsville and Taft's nomination before the national convention in June. At about the same time he was confirmed as Fourth Auditor of the Navy by the Senate, Tyler was appointed by Washington as one of the editorial writers for the New York Age, a newspaper edited by Fred R. Moore. The Age has been the most influential black weekly in the country when it was edited by T. Thomas Fortune and before it was purchased by Washington in the fall of 1907. It had carried on an anti-Roosevelt-Brownsville campaign and supported Foraker for the nomination since shortly after the dismissal of the soldiers in November 1906. Before Washington purchased the controlling interest in the newspaper from Fortune, the President had complained on several occasions that Fortune's editorials were doing much harm in undermining the administration's position on

42. Anderson to Washington, February 4, 1907, Washington Papers. 43. Anderson to Washington, February 4, 1907, Tyler to Washington, March 14, April 10, 1907, Washington to Roosevelt, April 11 , 1907, Washington to Tyler, April 11, 1907, Washington Papers. |

218 OHIO

HISTORY

Brownsville as well as misrepresenting

his attitude toward the race.44 The pur-

pose of Tyler's appointment as one of

the editorial writers of the Age was to undo

the damage done by Fortune and to help

swing black public opinion around to

support the President on Brownsville and

Taft's nomination and election.

Tyler began his assignment to influence

black public opinion in the interest of

the administration in an editorial which

appeared in the October 1907 issue of

the paper entitled "The Brownsville

Ghouls." By any account "The Brownsville

Ghouls" was a milestone in

scurrilous journalism--in a period when scurrilous

journalism was not unusual and was one

of the most controversial pieces of writ-

ings to come out of the entire

Brownsville incident. Its purpose was so obvious that

it was almost unbelievable to many of

the Age's readers, but moreso to its black

exchanges, which used it over and over

again to show the depths their competitor

would sink in its defense of Roosevelt

and Taft on Brownsville.

The editorial issued a blanket

indictment by condemning all those, black and

white, who had spoken out against the

President because of the Brownsville in-

cident as "human ghouls who preyed

upon the death and suffering of others for

their own financial or political

gains." It characterized the black supporters of

Senator Foraker as "buzzards,"

and attempted to convince blacks that color

prejudice had nothing to do with

Roosevelt's decision to dismiss the soldiers of

the 25th Infantry from the army without

honor. In Tyler's opinion the color ques-

tion in the Affair was a stone around

the race's neck. It had not been raised by

President Roosevelt, "whose many brave

and helpful acts have proved him to be

a real friend of the Negro"; or by

Secretary Taft, "another true friend of the race";

or by Senator Foraker, "who, after

all, simply raised a legal question in his de-

fense of the soldiers in the

Senate." Nor was the color issue raised by "the many

white friends of the race, in and out of

Congress." The color question in the

Brownsville Affair, said Tyler,

"was raised by black ghouls who were as much

enemies of Senator Foraker as they were

of President Roosevelt and Secretary of

War Taft and until the Satanic regions

open wide and swallow them we will

always have our human ghouls black and

white."45

From the printing of "The

Brownsville Ghouls" editorial in October 1907, until

Taft's convention victory in June 1908,

Tyler wrote and the Age printed similar

editorials in defense of Roosevelt on

Brownsville and in favor of Taft's nomina-

tion and election. Throughout this

period the Age played an important part in

helping to beat down all black newspaper

opposition to the administration, mak-

ing it the most outspoken supporter of

the administration among black news-

papers throughout the country.46

The initial reaction of many black

editors to the Age's campaign to influence

black public opinion was so intense and

hostile that Tyler suggested to Washing-

ton the establishment of what he called

a "Colored Press Bureau" under the di-

rections of R. W. Thompson. The bureau

would help control and influence these

editors in the interest of the

administration and generate greater support and

enthusiasm among those who were

non-commital or lukewarm to Taft's nomi-

nation. As envisioned by Tyler, the

bureau would gather favorable news items

of interest to blacks concerning the

administration's attitude toward the race and

dispatch them to most of the black

newspapers throughout the country. Tyler be-

lieved that by putting the relatively

obscure Thompson in charge of the bureau

44. New York Age, October 31,

1907, May 21, 1908; Cleveland Gazette, November 16, 30, 1907.

45. New York Age, October 17,

1907.

46. R. W. Thompson to Washington,

October 3, 1908, Anderson to Washington, September 10, 11,

1908, Scott to Tyler, March 26, 1908,

Washington Papers.

Blacks and Republicans

219

such news items could be

"incorporated judiciously" into opposition newspapers

without arousing the suspicion of many

of their editors. He said he would notify

the editors that he could cut their

expense by sending them weekly syndicated

letters from Washington covering all

news of interest to the race. Tyler realized

some of the editors might still be

suspicious of the project, and to encourage their

support he contemplated "mailing

them six or seven weeks of the letters free,"

believing this would at least temper

their criticism of the project until it could be

launched. Later a nominal fee of fifty

cents per newsletter would be charged

which would be used to cover Thompson's

salary as director of the Bureau.47

While Washington saw some advantages in

the project, he believed it was much

too risky. From his experiences with

many of the black editors, he wrote Tyler,

"some of those hostile to the

administration would find out about the project and

fire would come from them." While

Thompson was "a good and loyal friend,"

Washington feared he did not have

"the capabilities to handle such an extreme

and delicate matter." He was

"a bit enthusiastic and would therefore spoil

things."41

Nevertheless, three weeks after

Washington vetoed the project the office of

the New York Age was visited by

the New York member of the Republican Na-

tional Committee along with one of

Taft's campaign managers who had made the

trip from Washington with Tyler for the

purpose of consulting with Moore and the

editorial staff concerning additional

black newspaper support for Taft's nomi-

nation and election. Following this meeting

it was decided to organize a "Na-

tional News Bureau," looking toward

supplying black newspaper editors with the

same kind of news that Tyler had

outlined in his earlier letter to Washington.

Thompson was to be named director of the

bureau.

Washington's reactions to all of this

can only be guessed, but it is doubtful the

change of names from the "Colored

Press Bureau" to the "National News Bu-

reau" made the project any more

palatable to him. At any rate, Thompson was

given the additional responsibility of

making a canvas among black editors to

encourage their interest in the project

and after his survey reported to Washing-

ton that most of the editors contacted

"signified their desire for the services of-

fered by the bureau." But he feared

"the administration would not look good to

many of them until something was done

about Brownsville." He closed on an

optimistic note, however, feeling that

the situation was improving.49

If the Age's account of its own

campaign to influence black public opinion in

favor of Roosevelt and Taft can be

believed, the campaign has to be crowned one

of the most successful of its kind in

the annals of black journalism. Between the

establishment of the "National News

Bureau" and the party's national conven-

tion the newspaper ran a column entitled

"What the Negro Press Has to Say," in

which it reprinted comments and

observations from black editors throughout the

country concerning Taft's candidacy and

Roosevelt's Brownsville decision. Many

of these came from newspapers that had

been antagonistic or lukewarm toward

the administration because of the

Brownsville Affair. Many ran syndicated news

stories supplied by Thompson's bureau

and favorable to Roosevelt and Taft.50

47. Tyler to Washington, October 5,

1907, Washington Papers.

48. Washington to Tyler, October 7,

1907. Washington Papers.

49. Thompson to Scott, October 25,

November 3, 1907, Thompson to Washington, October 25,

1907. Washington Papers.

50. Washington to Frank Hitchcock, March

1, 3, February 1, 27, 1908, Hitchcock to Washington

February 27, 1908, Washington Papers.

Some of these newspapers included the Atlanta Independent,

the Savannah Tribune, the Topeka

Plain Dealer, the Birmingham Reporter, the Richmond Planet,

the Chicago Conservator,

and Augusta Baptist (Georgia), the

Charleston Southern Reporter, and the

Cleveland Journal.

220 OHIO HISTORY

Others, such as T. Thomas Fortune's Fortune

Freeman and W. Calvin Chase's

Washington Bee, also switched their support from Foraker to Taft, but

more out

of what appeared to be the hopelessness

of Foraker's chances of winning the

nomination than because of anything

Washington, Tyler, or the National News

Bureau said or did. Indeed, the attitude

of these editors best summarized the pre-

dicament that many of the black editors

found themselves in. Fortune had drifted

back into the newspaper business shortly

after he sold his interest in the New

York Age to Washington and by the beginning of 1908 edited a

struggling paper

out of Red Bank, New Jersey, called Fortune's

Freeman. He wrote in the Free-

man that "after mature reflection on President

Roosevelt and the Brownsville

decision," he had come to the

conclusion that his earlier attitude toward Taft's

part in the Affair had been harsh. He

now felt Taft had no alternative save to

follow Roosevelt's order to dismiss the

soldiers or resign from his Cabinet. Had he

chosen to resign (as Fortune had

suggested as editor of the Age shortly after the

War Department made the dismissal order

public) he would have "deprived the

country of his services" over a

matter in which he had little or no control.

From a political point of view, Fortune

continued, Taft stood an excellent

chance of winning the nomination, and

like Senator Foraker, "his friendship

toward blacks could not be

doubted." Thus he concluded, "Taft's record was

good, and if he win the

nomination," as it appeared he would, "the Freeman is

going to support him." W. Calvin

Chase's Washington Bee also saw the political

side of the issue, adding that all signs

pointed to Taft's victory at the convention

and if blacks shared in his success by

supporting him they would be rewarded. If

they should withhold their support and

Taft were nominated and elected with

the race arrayed against him, then they

could not expect any consideration dur-

ing his administration.51

By the time of the national convention

most black Republicans had drifted

back to support the party and Taft's

nomination, if for no other reasons than those

outlined by Chase and Fortune. The

Foraker movement was proportionately

weakened as they came back to the

administration and collapsed when most of

the thirty odd black delegates who

attended the Chicago convention climbed

aboard Taft's band wagon.52 When

the balloting was over Taft had received 702

of the 980 votes to Foraker's 16, 11 of

which came from Northern black delegates

in appreciation of his stand in defense

of the Brownsville soldiers. The convention

not only decisively nominated the

secretary of war as Roosevelt's successor, but

it also adopted a platform committing

him to the President's policies.53

Among later significant developments,

however, was the fact that in his con-

tinued eagerness to remove Brownsville

from any serious consideration on Taft's

candidacy among blacks during the

election, President Roosevelt accepted full

responsibility for the dismissal order

and ordered the War Department to release

all pertinent information on the

incident which showed that Taft had tried to have

him withdraw the order.54 In

addition, in a special message to Congress after the

election in December 1908, he made a

suggestion that many interpreted as a

tacit admission that he had been wrong

in dismissing the soldiers, the closest he

was ever to come to admitting that some

of the soldiers might not have known

anything about the disturbance at

Brownsville, and were consequently not guilty

51. New York Age, March 12, April

2, 9, 23, 30, May 28, June 4, 18, 1908; Boston Guardian, Jan-

uary 25, 1908.

52. Anderson to Washington, March 24,

April 1, 1908, Washington to Taft, June 7, 1908, Washing-

ton to Anderson, March 26, 1908, Scott

to Anderson, April 1, 1908, Washington Papers.

53. Henry C. Lodge to Roosevelt, June

22, 1908, Roosevelt Papers.

54. New York Age, March 12, 1908.

Blacks and Republicans

221

of a "conspiracy of silence."

He suggested that Congress pass legislation that

would allow the soldiers to reenlist in

the army "if they produced satisfactory evi-

dence that they were not involved in the

Brownsville raid."55 As a final note, the

majority of the 167 men dismissed

because of the disturbance were never rein-

stated. The Board of Inquiry that was

eventually appointed by the War Depart-

ment found only fourteen of the men

eligible for reinstatement but gave no rea-

sons why the others who applied were

found "unqualified."56

Thus despite more than two years of

black opposition to the President's Browns-

ville decision and the Taft nomination,

the secretary of war was eventually nomi-

nated and elected to the presidency. The

efforts of the Washingtonians to control

the dissemination of unpopular views

toward the administration were successful

to the extent that it was through their

activities that many blacks were convinced

they had little alternative save to

support Taft and the Republican party. Even

though Taft won the election against

William Jennings Bryan and the Democrats,

with the support of most black voters in

the North, the Brownsville Affair would

return eventually to haunt both him and

Roosevelt when they opposed each other

for the nomination in 1912. It helped to

fuel the conflict between the two men and

to aggravate a split in the Republican

party which finally led to the election of

the first Democratic presidential

candidate in twenty years.

55. New York Age,

March 12, 1908.

56. Walters, Joseph Benson Foraker, 246.