Ohio History Journal

|

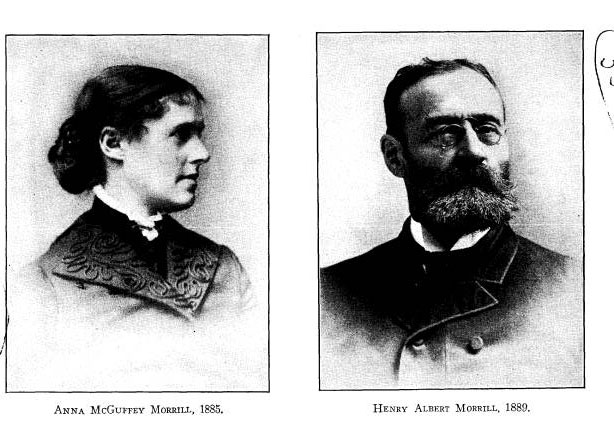

A DAUGHTER OF THE McGUFFEYS FRAGMENTS FROM THE EARLY LIFE OF ANNA MC GUFFEY MORRILL (1845-1924) EDITED BY HER DAUGHTER ALICE MORRILL RUGGLES |

|

|

|

Copyrighted, 1933 By ALICE MORRILL RUGGLES All rights reserved including the right to reproduce this monograph or portions thereof in any form. |

FOREWORD

In 1921, when my mother was living in

Cambridge,

Massachusetts, I suggested that she

write out her recol-

lections of early life in the Middle

West.

She demurred, "But I have never

written anything

in my life, except letters. . . ."

"Then write letters," I said.

She consented, and in her impulsive way

sat down

that very evening to see what she could

do. To her sur-

prise and delight, memories flowed from

her pen as fast

as she could make it go.

Night after night she wrote, and page

after page

was quickly filled with her graceful,

eager handwriting.

At the end of a week she gave me the

manuscript,

saying, "Here are the fragments

you asked for. Do

what you like with them."

I found my mother's literary style bore

the strong

imprint of her personality--artless,

vivid and direct.

For that alone her children treasure

these "fragments."

But other readers have urged their

publication, as foot-

notes to the social history of Southern

Ohio. To round

out the picture, I have added a few

extracts from a jour-

nal kept by my mother during her early

married life,

and a few from some later letters.

Undoubtedly the life of Anna McGuffey

was typical

of that of many other women of her

period. Inheriting

the rushing energy and conquering faith

of their pioneer

(246)

Foreword 247

fathers, they found their activities

narrowed and limited

to the conventional domestic pattern of

their day.

My mother sensed the dawn of a wider

life for

women. But of her own life, retired and

often bur-

dened with petty cares, she somehow

made a brave and

gay adventure; and always her spirit

seemed reaching

out beyond the daily round.

To those about her, to whom she gave of

herself

unsparingly, her best gift was an

impression of buoyant

living, fresh, upspringing, dauntless.

ALICE MCGUFFEY MORRILL RUGGLES.

Boston, 1933.

A DAUGHTER OF THE McGUFFEYS

I

CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS

1921

MY DEAR DAUGHTER:

At your earnest request I am writing

down these

fragments of my early life, and I will

begin by telling

you what you already know--that I was

born in Cincin-

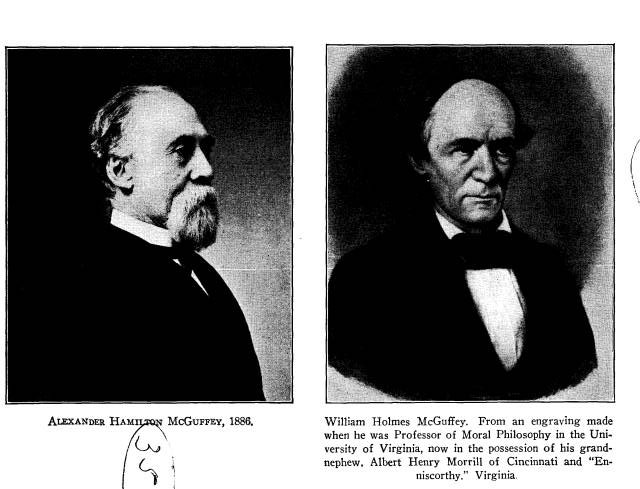

nati, Ohio, January 10, 1845, and my

father was Alex-

ander Hamilton McGuffey, of

"McGuffey Reader"

fame, and my mother, Elizabeth

Mansfield Drake,

daughter of Daniel Drake, M. D., who is

sometimes

called "The Father of Medicine in

the Mississippi Val-

ley."

Who wrote, or rather, who compiled the

McGuffey

Readers? ("Who killed Cock

Robin?") There has

arisen lately in our family a

discussion as to the true

answer to this question, and I would

like you to know

the facts as I learned them from my

father. He said he

was a young man of twenty-one, when his

brother, Wil-

liam Holmes McGuffey, who was sixteen

years his

senior, and a professor in the

Cincinnati College, re-

ceived an offer from the publishers,

Truman and Smith

to prepare a set of school-books, for

which the firm of-

fered to pay the sum of one thousand

dollars.

(249)

250

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

As Father was so young and not a busy

man, as yet

(he had just been admitted to the bar),

your great-uncle

William gave to him the burden of

preparation. But

Alexander did the work under the

supervision of his

brother, and he never claimed the

individual credit for

any of the first series, save the

spelling-book.

The Speller and the first four Readers

came out

about 1837. Two years later (1839, the

year my father

and mother were married), the publisher

wanted to add

a more advanced reader, and as William

McGuffey had

left Cincinnati, they asked your

grandfather to prepare

it. This was McGuffey's Rhetorical

Guide, which was

afterwards expanded into the Fifth and

Sixth Readers.

So there is glory enough (if glory it

be), for both

branches of the family. To William

belongs the initia-

tive, and the first four Readers; to

Alexander, the

Speller and the important Fifth and Sixth Readers.

I am astonished at the continued and

growing inter-

est in these old schoolbooks, and I am

sure my father

and Uncle William would be even more

amazed. They

must have builded better than they

knew. My father

always thought the original success of

the series was

owing more to the business acumen and

push of Win-

throp B. Smith, the publisher, than to

the inherent merits

of the books themselves. But posterity

will not agree to

this.

Mr. Smith and my father were close

friends and

dear, remaining so until Mr. Smith's

death. Of course

there was a great deal of money made

out of the

Readers, and in Uncle William's old age, the publishers

granted him a very tiny pension. Father

received five

hundred dollars for the Rhetorical

Guide.

|

(251) |

252

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

He always spoke of his part in the Readers

as a bit

of youthful hack work, and in the later

editions asked

to have his name removed from the

title-page. Of course

his interests were not primarily

educational, as were

Uncle William's. Uncle William's aim

was to have the

Readers instill moral lessons as well as correct English,

and two of his favorite themes were the

value of tem-

perance and the wasteful wickedness of

war.

Father became a busy and very

successful lawyer

and man of affairs. But he was a born

pedagogue just

the same, and his fondness for

instructing has been in-

herited by several of his children and

grandchildren, as

you know. Your own father, with his dry

Yankee

humor, used to say we McGuffeys wanted

to straighten

out all the crooked sticks in the

world.

I can never cease to be grateful to my

father for

instilling into his children a love of

reading and a

pleasure in words, their exact meaning

and proper pro-

nunciation. He constantly corrected our

enunciation and

intonations, and would no more tolerate

a slovenly

speech than a slouchy posture. He often inveighed

against the influence of the

newspapers, and the careless

English of the reporters, which he felt

was demoralizing

our mother tongue. What would he

say nowadays,

when the power of the press and the

cheap magazines

have increased a hundredfold? Though I

do think the

general standard of popular writing has

been greatly

raised.

The slipshod speech of the average

Middle Wes-

terner of eighty years ago must have

afflicted my father

and Uncle William grievously, and they

labored with a

A Daughter of the McGuffeys 253

missionary zeal to amend it. If you

will turn to an

early edition of the Readers, you

will find affixed to the

lessons curious little corrective

exercises like this:

"UTTER EACH WORD DISTINCTLY. DO

NOT

SAY OLE FOR OLD, HEERD FOR

HEARD, TUR-

RIBLE FOR TERRIBLE, NARRER FOR NAR-

ROW, CANIDY FOR CANADA, MUSKIT FOR

MUSKET, CUS FOR CURSE, AT FOR HAT,

BUSTS FOR BURSTS . . . ."

I must say my father spoke the purest

English I

have ever heard. He did not

"burr" his R's, as Western-

ers often do, neither did he slur them,

after the manner

of the New Englanders and the

Southerners. The

choice and pronunciation of words was

an art to him,

but he practiced it quite unaffectedly.

I suppose one reason for the recent

revival of in-

terest in the McGuffey Readers, is

the current vogue for

American "antiques." But

comparing them with other

readers of those early days, the

"McGuffeys" really are

superior. Ruling out certain

namby-pamby pieces of a

sentimental or "preachy" type

(characteristic of that

period), there remains so much of the

Bible, Shake-

speare and the classic English prose

writers and poets,

that I believe you might safely teach

your little Eleanor

out of Great-grandfather's Fifth and

Sixth Readers,

even in Boston, in the year 1921.

Certainly the selections show a wide

range of read-

ing and a cultivated taste for a youth

of twenty-three,

brought up in rural Ohio by parents who

were unedu-

cated pioneers. It always thrills me to

remember that

while my parents lived in the midst of

comfort and cul-

254

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

ture, their parents were self-made men

and women, who

as my Grandfather Drake expressed it,

"in one genera-

tion changed the caste of the

family."

Perhaps it is because I come so lately

from pioneer

stock, that I feel so much sympathy and

interest for

those whom Mr. Lincoln called "the

plain people." I

enjoy talking with them, and their

lives, no matter how

humble and obscure, seem to me teeming

with interest.

They have always seemed to come to me

freely with

their problems, and to let me share in

their joys and

sorrows.

I wish that my children and

grandchildren might

always keep something of the pioneer

spirit, that never

fears to press on and up. Remember the

motto that your

father and I chose at the beginning of

our fifty years

together--"ANIMO ET FIDE,"

"WITH COURAGE

AND FAITH."

II

My parents told me little about their

childhood. My

father was born in Trumbull County,

Ohio, and brought

up there till his brother took him to Miami.

Of the

McGuffeys back in Scotland, I know

nothing. My

father was quite indifferent to

genealogy. He said his

forbears seemed to have been decent,

honest and God-

fearing people, and that was all he

cared to know.

In this country we began with William

and Anna

(McKittrick) McGuffey, who came over

from Scotland

in 1774, and landed at Philadelphia. I

never heard of a

McGuffey figuring in Scottish history,

so I fancy we

were humble folk over there. Certainly

the name is the

homeliest one imaginable. But at least

it is uncommon

A Daughter of the McGuffeys 255

in this country, and I much prefer it

to Smith, Jones,

Brown or Robinson.

Our first American ancestors made a

home in York

County, south-east Pennsylvania, and

tradition has it

that General Washington often stopped

there during the

Revolution. These were my

great-grandparents. From

York they migrated to south-western

Pennsylvania,

Washington County--a rich valley land.

They had a son, Alexander McGuffey, who

was a

famous Indian scout. Scouting was very

dangerous

and exciting work, and I've no doubt

young Alexander

loved it. He was only twenty-two when

he volunteered

for this service, and he and his

friend, Duncan Mc-

Arthur, afterwards Governor of Ohio,

were selected

from among other candidates as the

fastest runners,

best marksmen and the most unafraid of

Indians.

You know the western frontier of

Pennsylvania and

Virginia was overrun with Indians from

the Ohio coun-

try at that time, and small parties of

scouts were em-

ployed to hide in the woods and swamps

to spy on the

savages and report back to the officers

of the regular

troops.

The early settlers (except William

Penn) saw noth-

ing inconsistent with their religion in

the killing of

Indians, in fact they considered it a

virtue to kill them

whenever and wherever they could. Their

wives and

children lived in constant dread of

these savages. Of

course the Scotch-Irish were fighters

by nature, and by

centuries of experience in their old

countries.

Alexander McGuffey was in several

fights with the

Indians, and when General St. Clair

made his unlucky

march from Cincinnati in 1792--(you've

read about

256

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

that in your American history)--it was

your great-

grandfather's party of scouts who went

ahead to recon-

noitre. They traveled only at night,

and hid during the

day. One night they travelled forty

miles. They were

able to get back in time to make their

report to General

St. Clair, but three days later he was

defeated, for the

number of Indians who had collected

against him was

overwhelming.

The next year Alexander and two of his

young

friends were sent out by General Wayne

to spy on the

Indians. One evening in the gloaming,

as they were

stealing along a trail, Alexander, who

was leading, saw

in the path the bright-colored

head-dress of an Indian.

Had he stooped to pick it up, he would

have been in-

stantly shot from ambush. Then there

would not have

been any you or I! Luckily he realized

the trick and

that the head-dress had been placed

there by Indians

who were watching from the bushes,

ready to shoot the

first white man who tried to pick it

up. Without stop-

ping in his march, he gave the

head-dress a kick and

shouted, "Indians!" Several

shots flew after him from

the bushes and one of them smashed his

powder-horn

and passed through his clothing; but he

and his com-

panions all got away and the Indians

did not follow

them. I wish that shattered horn had

been preserved

for your children to see. But probably

the incident did

not seem remarkable to our

ancestors--so full of perils

and hairbreadth escapes, their lives

were.

Alexander remained in the scout service

three years.

The wars with the Indians ended in that

region in 1794,

and then Alexander, I think they called

him "Sandy"

(fancy my stately father being

nicknamed Sandy--

A Daughter of the McGuffeys 257

never, never--though his father-in-law

did refer to him

as "Alick"), Sandy married

and became a settler. This

does not mean that he settled down to a

quiet life and

fixed abode. When his first child

(William Holmes,

who was to compile the

"Readers"), was two years old,

the parents set out with him for the

Ohio frontier.

They belonged to that reckless, eager

type of fron-

tier settlers, (as did my maternal

ancestors, the

Drakes) who were always pushing further

and further

west, in the hope of bettering their

condition. The Mc-

Guffeys built a log cabin and brought

many more chil-

dren into the world. The boys helped

the father clear

the land, and plough and plant, and

build roads and

fences and bridges. The girls helped

the mother; you

can imagine how endless their tasks

were.

The mother's name before she married

was Holmes,

Anna Holmes, so the name Anna was on

both sides of

the family. I always understood I was

named for my

father's mother, but I like to think

that I bear the name

--(though I don't think it a pretty

one)--of two pio-

neer mothers, Anna McKittrick, who came

over from

Scotland with her young husband and a

little son six

years old--(afterwards Sandy the

Scout)--and Anna

Holmes, who migrated with her young

husband and a

little son of two--(who grew up to

write the Readers)

-- to the rude Ohio country. My own

life-work has

been to bring up a family and help my

husband through

cares and struggles, that often seemed

to me overwhelm-

ing. I am thankful that I had the

strength to sur-

mount them, as my grandmother and

great-grandmother

had surmounted their far greater

difficulties before me.

My people seem to have been the kind

who did not

Vol. XLII--17

258

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

count hardships, if they could better

their condition

and win an education for their

children. In the early

nineteenth century there was no chance

for a child to be

educated in Trumbull County, Ohio, and

Alexander and

Anna were too poor to send their

children away. But

William, the eldest, had a fine mind,

and his mother was

determined he should have a chance.

You already know the story of how she

was praying

loud and fervently in the garden one

day, when Thomas

Hughes, who had started a school for

the higher edu-

cation of young men in Pennsylvania,

was riding by on

horseback, and overheard her asking the

Lord to open

some way for the education of her son.

Of course,

(like one of the moral tales in the

McGuffey Readers),

he was so struck with her plea that he

dismounted, made

her acquaintance and invited her son

William to enter

his "Old Stone Academy." The

tuition at this school

was three dollars a year, and the board

was seventy-five

cents a week. But I never heard how

even that pit-

tance was procured. William used to

attend school for

a while and then come back to work on

the farm. So

he was twenty-six before he graduated

from college, but

he took highest honors. He was ordained

as a Pres-

byterian minister, but became a

professor of mental

philosophy--whatever that was--I

suppose the equiva-

lent of what the colleges now offer in

two subjects,

philosophy and psychology. Uncle William

was first

at Miami University, later at

Cincinnati College and

Ohio University. Finally he was called

to the Univers-

ity of Virginia, where he remained for

twenty-eight

years. At Miami and in Virginia his

memory is still

cherished and his work honored.

A Daughter of the McGuffeys 259

My uncle William was born in 1800, and

lived till

1873, when I was twenty-eight years

old. But I did

not see much of him after I was grown.

He became

quite Southern in his sympathies after

living through

the Civil War in Charlottesville,

Virginia, and of course

my parents were ardent Unionists. Not Abolition-

ists, however. You must remember that

Abolitionists

were regarded by polite society much as

Bolshevists are

now.

My maternal grandfather, Daniel Drake,

had writ-

ten a series of articles for the

newspapers, showing the

folly of Abolition as illegal and

revolutionary. He was

in favor of the limitation of slavery,

and gradual eman-

cipation by purchase. These articles of

Grandfather's

were afterwards published in book form.

I used to have

a copy, but it has disappeared. You

children would

have found his attitude curious in the

light of later his-

tory.

But Grandfather Drake abhorred slavery,

as did his

father and mother before him. You may

read in his

Pioneer Life, his description of the hideous cruelty to

slaves he had seen in his childhood in

the backwoods of

Kentucky. At the date he was writing,

(1847), their

lot had been vastly ameliorated. Public sentiment

would no longer tolerate, at least in

the cities, such

brutality as he had witnessed in the

backwoods at the

end of the eighteenth century:

One of my great-grandfather's cabins

was rented

to a man named Hickman, who although

very poor,

owned two slaves, one a negro man in

middle life, the

other a woman at least twice the age of

her master. He

used to abuse them both most horribly.

Although the

woman had been his nurse in infancy, he

would tie her

|

(260) |

A Daughter of the McGuffeys 261

up, strip her back naked, and whip her

with a cowhide

till the blood flowed to her feet, and

her screams reached

the ears of my grandfather's family at

a distance of

more than three hundred yards.

Great-grandfather's

blood used to boil but he had no

redress except angry

remonstrance and the whole neighborhood

were de-

lighted when Hickman moved away. All

the masters

were not as cruel as this man, but the

treatment gener-

ally of the negroes at that time was

severe, "barbarous,"

Grandfather calls it as compared with

that in 1847,

when he wrote. No wonder such

iniquities had to be

wiped out in blood.

Of all the Jersey immigrants in

Kentucky (my moth-

er's people came from New Jersey), my

great-grand-

father was the only one who did not

become a slave-

holder. And my grandfather Daniel Drake

purchased

only two negro children, a brother and

sister, Carlos

and Hannah, eleven and nine years of

age, in order to

emancipate them. He brought them to

Cincinnati in

1818 and had them bound over to the

overseers of the

poor, till they should come of age.

Hannah was then

taken into his household as the nurse

of my mother,

Elizabeth Drake (McGuffey), and her

sister, my Aunt

"Echo."

To go back to Uncle William McGuffey, I

do not

think that his Southern sympathies led

to any estrange-

ment in the family, but I do know that

my father told

him when he came north directly after

the Civil War,

that he must be very careful what he

said. Feeling ran

very high during that Reconstruction

Period. Uncle

William was sent by the publishers of

the Readers to

make a tour all through the South and

report on condi-

|

262 |

A Daughter of the McGuffeys 263

tions. When he returned he had a

shocking story to

tell of the "Carpet Baggers,"

but no Northern paper

would print it.

Uncle William was, in build, shorter

and more com-

pact than my father. He had sandy hair

and large, ir-

regular features. He showed all his

large teeth in his

warm smile. He had the same, keen,

kind, twinkling

eyes that my father had, but in repose

both the brothers'

faces wore an expression so serious that

you children

would have found it stern. I think

Uncle William, in

his genial moods, looked a little like

Hans Christian An-

dersen. He was like him, too, in his

love of children

and in his simplicity and

unpretentiousness. He had

not at all the "grand manner"

of my father; was more

approachable; in other words, more

democratic. Wil-

liam was noted for his love of

argument, whereas Alex-

ander never argued, and hated to be

questioned or con-

tradicted.

My father laid down the law, and that

was the end

of it. Once when he had given his

opinion on some

point in pronunciation, one of his

children ventured to

tell him that the dictionary held

otherwise. "Then the

dictionary is wrong!" he flared

back, and no one ar-

gued it any further. But we saw the

humor of it, and

among ourselves, when any of us was

loth to yield a

point, some one else would cry,

"Of course the dictionary

is wrong!"

Uncle William's theories on education

were radical

for those days. (It amuses me now to

hear many of his

ideas put forth by progressive

educators as new.) He

detested teaching by rote. When he was

asked to pre-

pare the Readers, he gathered a

group of children into

264

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

his house at Miami University, and

worked out the read-

ing lessons, by careful, personal

experiment. In his

college class room, after questioning

the pupils, he would

turn the class over to them and let

them quiz him. This

may not seem very radical to you today,

but seventy

years ago, it was an original system

for an American

teacher to adopt. Uncle William wanted

the students

to learn to think for themselves, and

nothing provoked

him so much as to have his own words,

or those of the

text-book repeated back to him. From

what my grand-

children tell me, I believe that even

now there is too much

of that rote teaching and learning.

Uncle William was more than once in

straits for

money, through no fault of his own, but

owing to the

financial difficulties of the

struggling colleges with which

he was connected. I know that my

father, who was

prospering at the law, was glad to help

his elder brother,

to whom he owed so much.

The two were always devoted and

congenial, in spite

of the great difference in age--sixteen

years. When

Uncle William was in Cincinnati, the

brothers had long

walks and talks together. In those

days, people still

walked for health and pleasure, and our

southern Ohio

country is so varied and beautiful for

rambles.

When my father's turn had come to be

educated,

William had been able and willing to

help him. So little

Alexander had an easy road compared to

his eldest

brother. When he was only ten, he was

placed in his

brother's charge at Miami (Oxford,

Ohio), and he

learned Hebrew grammar before he did

English. Uncle

William tried out all his theories on

his small brother

and let him advance as fast as he could

and would. The

A Daughter of the McGuffeys 265

result was that Alexander, who was a

brilliant student,

was graduated from college at sixteen.

Of course the college courses of those

days did not

compare with the modern standards. But

Alexander

was considered a highly educated lad

for his age, and

soon after graduation, he was appointed

professor of

belles lettres, at Woodward College,

Cincinnati (later

Woodward High School). He loved

literature, but de-

cided to become a lawyer, reserving the

classics for his

leisure hours.

He studied law while he was teaching,

and was ad-

mitted to the bar when he was

twenty-one. He prac-

ticed law for over fifty years, chiefly

as a counsellor. He

was too nervous to stand the strain of

court work. My

father's personality was a great asset

in his profession.

His courtly, commanding manner inspired

confidence in

his clients. Even if his business

judgment was not al-

ways good, they thought it was.

As a young man my father must have been

a dis-

tinguished figure anywhere, though not

strictly hand-

some. He was tall and straight, had

large features, blue

eyes and abundant brown hair and beard.

His eyes re-

mained keen, and his teeth perfect

until he died, at

eighty. His expression was somewhat

austere, until he

smiled. Then he was delightful; his

face lighted up, and

he became genial and humorous and

winning.

His nature was proud, sensitive and

independent. I

should say the most characteristic

trait of our family

is independence, and next to that,

extreme sensibility.

Apparently we get a strain of

sensibility from both the

McGuffeys and the Durakes, and what a

handicap it is!

My father, although the picture of

health, suffered from

266

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

a weak back all his life. He always had

a sofa in his

private office, where he could rest at

intervals. Un-

doubtedly his was a case of nerves,

before nerves were

understood.

He read Latin and Greek and Hebrew all

his life

for pleasure, and by the standards of

the Middle West

in those days, was a scholar. He was

interested in art,

especially painting and pottery, in a

day when such

things were regarded as frivolous

interests for a man of

his type, and he was a patron of the

Cincinnati Art Mu-

seum and the Rookwood Pottery at their

beginnings.

It must have been the aesthetic side of

the Episcopal

Church that influenced him to leave the

Presbyterian

Church in which he had been brought up.

Of course

he was influenced too, by his wife,

whose father, Daniel

Drake, had helped to start the first

Episcopal Church

in Cincinnati, my beloved Christ

Church. But the ritual

appealed to my father for its dignity and

formality,

though he had no use for High Church

practices. In

art and architecture his tastes were

unerringly simple

and sincere, and throughout the worst

period of Amer-

ican taste, he remained untouched by

the current fash-

ions for the ornate and elaborate. In fact he de-

nounced them as "hideous."

Whether he trained my taste, or whether

it was in-

nate in both of us, and part of our

Scotch love for the

plain and practical, I do not know, but

I shared my

father's dislike for

"gingerbread" architecture and

fussy Victorian furniture and

furnishings. During the

'seventies and 'eighties, when my

friends crammed their

houses with bric-a-brac on

"what-nots," and gilded rol-

ling-pins and cattails, mine was sparsely

furnished with

A Daughter of the McGuffeys 267

the few simple pieces of old furniture

I had inherited,

or had been able to buy in second-hand

shops. You

can't imagine how queer I was

considered because I

didn't have plush covers with tassels

on my parlor tables,

but left them bare! When I

purchased that old French

mahogany set now in my guest-room, from

a second-

hand dealer on Vine Street Hill, your

father, who was

more conventional in taste, said,

"Anna, people will

think that is some old junk that has

come out of the

family attic!" You see it was the

thing to have new

walnut bedroom sets with marble tops

and bunches of

carved fruit and flowers gummed on. I

had such a

set your father had bought me when we

went to house-

keeping, but although it was expensive

and fashionable

enough to delight the heart of an 1867

bride, I never

admired it.

Some years later your father's cousin,

Julia Morrill,

wrote from Vermont, asking if we would

care to have

the old grandfather's clock that had

stood in the kitchen

of the farm where she and your father

were brought up.

Your father remembered it as a plain

old pine clock, and

thought it would be most unsuitable in

our modern

house. But I persuaded him to have it

sent out to Cin-

cinnati. When it arrived and was set in

the hall and

wound up, and proceeded to strike the

hour, your father

was so happy; the clear silvery sound

brought back in a

rush all his boyhood life on his

grandmother's farm. He

could scarcely sleep that night for

listening to the old

clock's voice, and many a night in the

years to follow,

the loud, friendly ticking and silvery

striking cheered

him through sad and sleepless hours.

Those old clocks

have much individuality, and sounds,

like odors, have

268

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

a remarkable power of rousing old

memories. I must

admit that in those days, Grandfather

Morrill's clock

was cherished more for its associations

than for its looks.

Even I had not acquired a taste for

crude pine, and I

purchased a bamboo panel at the

Japanese store, cut it

in two and draped it over the shabby

top of the grand-

father clock's head, which could be

seen as one came

down the stairs.

I am losing the thread of my story, but

one thing

leads to another, and I must tell you

these little incidents

as they occur to me. My story will be

made up of little

things, as any woman's story must, who

has lived a

purely domestic life. The only big

things in my life

were inside me, my feelings. But I

think you and your

children will enjoy these simple little

things I tell, by

and by, when they have become a part of

"long ago."

You children remember your grandfather,

Alexander

McGuffey, as a stately old gentleman

with a snowy

beard, and as being very active and

sprightly. He would

run up the stairs to his office, just

to show the younger

men he could do it, and he hated to be

helped on with his

overcoat. He used to correct your p's

and q's, but de-

lighted your hearts by pressing gold

pieces into your

palms, on the sly, whispering,

"There, run along, and

don't tell anybody about it." He

never wanted to be

thanked for his favors, which he

dispensed with a free

and generous hand.

He had none of the proverbial Scotch

thriftiness;

indeed he detested economies. I was brought up to

think it ill-bred to speak of the price

of things. I recall

once when I went with Father to buy a

traveling-bag,

the clerk volunteered to mention the

price of one we

A Daughter of the McGuffeys 269

were examining. My father said in his

grand manner,

witheringly, "Young man, I have

not asked you the price.

The quality is all that

interests me."

His tastes were fastidious and lavish,

and I think

at heart his children shared them,

though some of us

have had to practice economy, whether

or no. George

Eliot says, somewhere, that there is a

pleasure in small

economies, if practiced as a fine art.

You children can

testify that your father and I practiced

that art for many

years, but there was nothing in my

early training to

help me. I believe I love to spend

money as freely as

my father did, but I had lived to see

the folly of it.

But although I have had to count the

cost of living

so carefully, I cannot bear the modern

fashion of es-

timating everything in terms of money.

You remember

when you children were growing up, I

would not allow

the cost of food to be mentioned at the

table, I said it

took away one's appetite. But nowadays

young people

consider their clothes, cars, gifts,

even their own abili-

ties from the standpoint of what they

are worth in

money.

Do you remember the quaint old offices

in the Cin-

cinnati College (or Mercantile Library)

Building, that

your father and grandfather occupied

for so many

years? One entered an enormous, murky

room, where the

younger partners and the clerks sat

with their desks

carefully arranged in the order of

their importance.

Your father's was next to the window,

then came

the smaller fry, tapering away into

insignificance and

almost total darkness. Your

grandfather, the senior

partner, was not visible to the vulgar

eye. In the far-

thest corner of the room was a glass

door, marked

270 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

ALEXANDER H. McGUFFEY . . . . PRIVATE

OFFICE. Those privileged to enter

found, in contrast

to the big, bare, musty outer office, a

bright, cosily fur-

nished room, where your grandfather

worked or rested.

In one of the drawers of his desk, he

kept a canvas bag

of bright pennies, into which his

grandchildren and other

youngsters were invited to dip their

hands and draw

out what they could. You were always

timid, and

would take a modest two or three. But

your little sister

Genevieve would plunge her hand in

boldly and draw

out an overflowing fist, with pennies

sticking between all

her tiny fingers. The first time she

did it, her grand-

father looked nonplussed, for she had

half emptied his

bag. I doubt whether any other child

had shown such

enterprise, but he only smiled

quizzically, instead of ut-

tering the reproof I had seen hovering

on his lips.

III

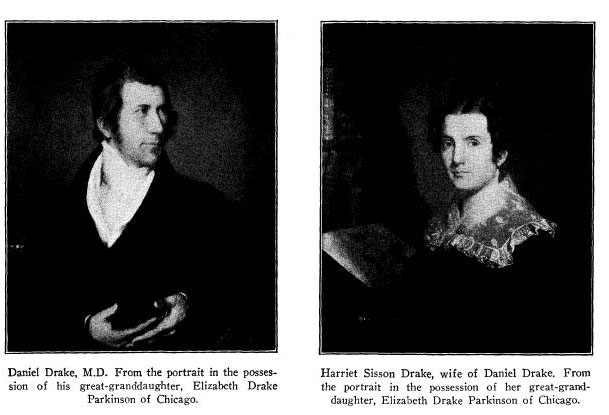

Now about my mother and her people. She

was

Elizabeth Mansfield Drake, daughter of

Daniel and

Harriet Sisson Drake of New Haven,

Connecticut. My

father married her soon after he was

admitted to the

bar. Her father was one of the most

distinguished men

in the Ohio Valley, and the connection

must have helped

young Alexander professionally and socially.

But more

fortunate for him was the fact that he

had won a beau-

tiful and gentle wife. Because of her

gentleness, her

pet name in the family was

"Dove." You can see from

her portrait, by Thomas Buchanan Read,

(it hangs be-

fore me as I write), how well she

deserved the name.

The artist has caught her shining,

brooding expression

to perfection. Buchanan Read, who was a

poet as well

|

A Daughter of the McGuffeys 271 as an artist, was a friend of my parents, and often visited us. He painted my brother Charley and me, as well as Mother. When I was growing up, I heard far more about |

|

|

|

my mother's family than my father's. This, I suppose, was because the Drakes were one generation ahead of the McGuffeys in culture. But both families were pio- neers and their stories are alike in many respects. |

272 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

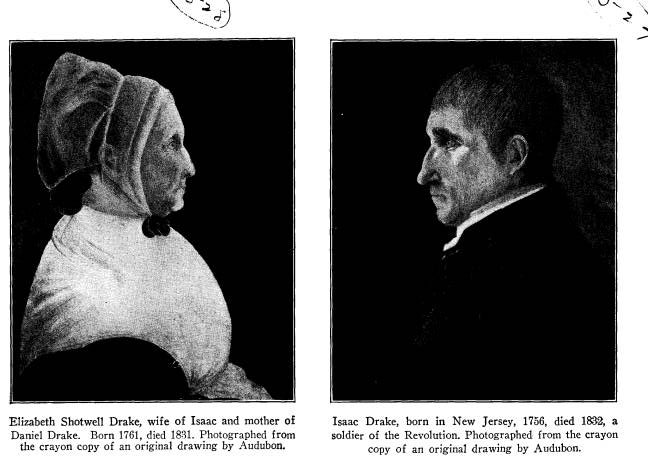

During those years that Sandy and Anna

Holmes

McGuffey were toiling to bring up their

family in a log

cabin in Pennsylvania, and praying for

the means to

educate them, another brave pair, (and

there were hun-

dreds and hundreds of others all over

the frontier),

Isaac and Elizabeth Shotwell Drake,

were going through

just such struggles in a cabin in

Kentucky. They had

emigrated in 1788 from the

"Jersey" country, and their

first home in the West was an abandoned

sheep-pen.

The Drakes came originally from

Devonshire, as

every child knows from Charles

Kingsley's Westward

Ho.1 Tradition says that the first Drake got his name

from "Drago," a dragon,

because of his fiery disposition,

traces of which are still cropping up

in my family, just

as the love of argument crops up from

the McGuffey

side. Our branch of Drakes in America

settled first in

New Jersey, and from there my

great-grandparents

"pioneered" to the "Dark

and Bloody Ground" of Ken-

tucky.

My great-grandfather, my

great-great-grandfather

and my great-great-uncle had all been

soldiers in the

Revolution. No doubt they were sick of

war and the

hard post-war conditions. Their hearts

turned to the

frontier, where they might find wider

opportunities for

peace and plenty, for their children,

if not for them-

selves.

You can read all about that journey in

Daniel

Drake's Pioneer Life in Kentucky, written

in 1847 and

published by the Ohio Valley Historical

Society in 1870.

This book has become rare nowadays, but

I daresay it

1 Tradition in the family made Sir

Francis Drake an ancestor of the

New Jersey Drakes, but the descent has

never been traced. Ed.

A Daughter of the McGuffeys 273

will be reprinted some time, for he

gives a vivid, first-

hand picture, and his style is simple

and readable, sur-

prisingly modern, in fact. Your

children can get the

feeling of frontier life from Grandfather's book more

truly than from a dozen histories.

There were five families who made that

journey of

four hundred miles across the

Alleghanies together, in

the spring of 1788. Isaac Drake was the

youngest, the

poorest and the most limited in

learning. Both he and

his wife could read and write and that

was all. The

Drake party consisted of Isaac and

Elizabeth, Eliza-

beth's sister, Lydia Shotwell, little

"Dannel," aged two

and a half and his baby sister Lizzy.

These five were

crowded with all their worldly goods

into one two-horse

Jersey wagon. (Lydia Shotwell preferred

to brave the

wilderness rather than be left behind

in the power of an

uncongenial stepmother. I'm glad to say

her courage was

rewarded, for she soon found a husband

in Kentucky

and had some happy years, though she

died later in child-

birth, poor thing, before the doctor

could be fetched from

Cincinnati.)

There were few taverns along the way,

and the

travelers were too poor to stop there,

so they slept in

the wagons and cooked their two meals

on the roadside,

at morning and night. They were in

constant danger

from Indians and when they embarked on

the Ohio

River in a flotilla of flatboats, one

of the crowded boats

upset, but no one was drowned. Small

Daniel had come

nearest to grief one day in the wagon,

when he clam-

bered over the front board and hung on

the outside by

his hands. He was discovered and yanked

in by his

Vol. XLII--18

274 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

harassed parents before he fell,

perhaps to be crushed

under the wheels.

They landed on the tenth of June near

what was

later Mayslick, Kentucky. My

great-grandfather had

sprained his ankle and had to be

carried out of the boat,

so "he could put but one foot on

the land of promise. He

was not very heavy to carry for he had

in his pockets

but one dollar and that was

asked for a bushel of corn!"

He found work as a wagoner, carrying

goods back

and forth to Lexington, dangerous work,

and he had

more than one narrow escape from the

Indians. Pres-

ently he bought land, thirty-eight

acres. He probably

paid for it with his horse and wagon.

The next task

was to build a house, and quite time,

too, for winter was

approaching. It was a log-cabin, one

story high, with-

out a window; with a door opening to

the south, a

wooden chimney and a roof on one side

only. Neither

chimney nor roof was finished before

the winter caught

the builder and stopped the work.

The floor was made of

"sleepers." Daniel's first rec-

ollection was of jumping happily from

one pole to an-

other, and making a sort of whooping,

guttural noise

for the amusement of his sister Lizzy.

The reason for

his remembering the scene was that his

father came in,

and ordered him sharply to "stop

that noise!" For all

their fortitude, the nerves of the

pioneers must have

been often on edge with all they had to

endure.

One warm day during that first summer,

while they

were still living in the sheep-pen, my

great-grandmother

Elizabeth made a call at a neighboring

cabin, where a

woman was churning. Elizabeth was tired

of a diet

of bread and meat, and fixed her heart

on a drink of

A Daughter of the McGuffeys 275

buttermilk, but said nothing. When the

butter was

ladled out and the churn set aside,

with the delicious

beverage, for which she was too proud

to ask (and

which the other perhaps did not think

of giving), she

hastily left the house, went home and

cried bitterly.

How I sympathize with her! She had gone

through

hardships almost intolerable without

complaint, but

missing that drink of buttermilk was

the last straw! But

how foolish she was not to ask for it.

In the following spring, the log-cabin

was finished,

with a clapboard roof above, a puncheon

floor below

and one small square window without

glass. On the

log wall over the fireplace hung

Isaac's rifle, and under

his bed at night he kept his axe and

scythe, ready to

hand in case of attack from the

Indians. In the morning

small Daniel's first duty was to ascend

the ladder to the

loft, and look through the cracks for

Indians who might

have planted themselves near the door,

ready to rush

in when the strong cross bar should be

removed.

Although the children in that region

were told when

put to bed "to lie still and go to

sleep, or the Shawnees

will catch you!" Daniel's own home

was never attacked.

But at Aunt Lydia's wedding, there was

an attack re-

ported up the road and all the men

guests, who had come

armed, mounted their horses and

galloped off in a style

so picturesque that the little boy

never forgot the pic-

ture.

At first Daniel's tasks were in the

cabin, helping

his mother. She had, beside the cooking

and cleaning,

brooms to make, also soap, butter,

cheese and sausages.

Daniel helped her with all these and

with her spinning,

carding, weaving and dyeing. As he grew

older, he

276 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

went out into the woods and fields with

his father,

cleared and ploughed the land, washed

and sheared the

sheep, killed and cured the hogs,

hunted and fished.

Through all Grandfather's account runs

an intense love

of this frontier life. He never tires

of describing the

trees and flowers and animals, and the

beauties of the

changing seasons. He never dwells on

the hardships,

only the delights of that outdoor life,

and the only re-

gret he expresses is that he was given

so little "book

learning." Aside from that, he

says no child could have

had a richer, happier life than his.

Now Dan Drake's parents, like that

other pair of

poor, backwoods settlers, Sandy and

Anna McGuffey,

were determined that at least one of

their children should

have an education. Little Daniel, the

eldest, was des-

tined, from the time he was five, to be

a doctor. He had

been promised as a student to a certain

Dr. Goforth,

who had been one of the party to cross

the Alleghanies

with the Drakes. He had attended them

in the fevers

and accidents that fell to their lot

during the first years

in Kentucky, and now he had settled in

Fort Washing-

ton (Cincinnati).

To study medicine was an unheard-of

ambition in

the backwoods of that day. But to

strike out new paths,

to begin things, was a passion

with Grandfather all his

life. The idea of being the first

student of medicine in

the Middle West attracted the lad by

its novelty and

difficulty. To "pioneer" in

the study of the diseases

peculiar to that new country became his

dream, which

he lived to realize in his monumental

work, Diseases of

the Mississippi Valley.

Daniel's family worked and saved, and

when the boy

A Daughter of the McGuffeys 277

was fifteen, (in 1800, the year William

Holmes Mc-

Guffey was born), they were able to

send him to Fort

Washington "to be made into a

doctor and a gentleman."

Fort Washington (Cincinnati, or Cin.,

as it was some-

times called then), was a village of

four hundred souls.

To the lad from the backwoods, it

seemed the centre of

learning and elegance. His mother had

fitted him out

grandly, with hand-knitted socks,

coarse India muslin

shirts (instead of the tow linen ones

he wore at home),

a couple of cotton

pocket-handkerchiefs, and as the

crowning glory, a boughten white

"roram" hat, which

to his great grief, was stolen less

than a month after he

reached Cincinnati.

In those days the doctor was

apothecary, too. Young

Drake slept under Dr. Goforth's

counter, swept out the

office, put up and distributed the

medicines. For the

patients' sake, let us hope the

prescriptions were simple.

Between times, the apprentice taught

himself enough

Latin to be able to understand the medical

text-books.

He had had no education beyond the

three R's of the dis-

trict school, and the reading of stray

books his good

father had picked up for him by hook or

by crook.

Among these Grandfather remembered Pilgrim's

Progress, Robinson Crusoe, Aesop's Fables, Franklin's

Life, Dickinson's Farmer's Letters, and the Letters

of

Lord Chesterfield. Not a bad

collection, but it is touch-

ing and amusing to me, to think of

Daniel's parents, poor

and ignorant and aspiring, counselling

their son to

model his manners on the maxims of

Chesterfield, as

Grandfather said they did. Truly

American.

After three and a half years of study,

Dan was taken

into partnership by Dr. Goforth, and

wrote to his father

278 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

that business was increasing rapidly,

and they charged

from three to six dollars a day, though

he doubted

whether one-fourth of it could ever be

collected!

The next year the lad decided to go to

Philadelphia

to study at the University of

Pennsylvania under the

famous Dr. Benjamin Rush. How he

managed it finan-

cially, I cannot imagine, but he had

saved something

and his father helped him a little. He

wrote home, "I

only sleep six hours in the

twenty-four, and when awake

try never to lose a single minute. I

had not money

enough to take a ticket at the Hospital

Library, and

therefore had to borrow books." He

saved on food to

buy candles for study at night, as many

another poor,

ambitious youth of that period had to

do.

In 1806 he returned to Cincinnati, and

having settled

down to practice medicine, he promptly

married. He

was twenty-two, and the bride, Harriet

Sisson, twenty,

and as poor as himself. To marry and to

marry young,

has been the custom of all my people.

This may not be

always wise from a worldly standpoint,

but the fact

remains that our homes, our mates and

our children are

the things we care about most.

Dan Drake and Harriet began the world,

as Grand-

father puts it, "in love and hope

and poverty." Harriet

was an orphan who had spent her

girlhood as a de-

pendant in an uncle's family.2 She was intellectual

rather than domestic. Her favorite

authors were Dr.

2 This

uncle was Colonel Jared Mansfield, professor of mathematics

at West Point, sent by Thomas Jefferson

to survey the Northwest Terri-

tory. Ed.

A Daughter of the McGuffeys 279

Johnson, Bacon, Milton, Homer and Ovid!

"To Virgil

she was not partial in any palpable

degree." (!)

She and her husband were inseparable.

Grand-

father travelled all over the West and

South for con-

sultations and for research, and his

wife always went

with him. When she died at the age of

thirty-eight,

they had travelled more than five

thousand miles by land

and sea, and often under the roughest

conditions. I

have sometimes wondered if the

hardships of those jour-

neys were not responsible for my

grandmother's com-

paratively early death. At any rate

that was better than

to be worn out by incessant

child-bearing, as my own

mother and so many thousands of women

were in those

days.

Daniel and Harriet had only three

children, and while

my grandmother was a good mother, it is

evident that

she put the claims of her brilliant and

temperamental

husband first. He himself wrote after

her death, "After

her husband, all her solicitude, her ambition

and her

vanity were for her children. She loved

them as can-

didates for excellence, hence her

affections were chas-

tened with severity."

My mother, Elizabeth Drake, though only

a tiny girl,

was away at boarding-school when her

mother died. (I

have seen the letter she wrote home to

her father at the

time. It begins, "I greatly regret

to learn of the death

of my dear mother." I have always

wondered whether

those formal words covered deep

feeling, or whether my

grandmother was not a warm-hearted

woman, and so

the little daughter away at school had

only "deep regret"

and not an aching heart.)

When Daniel Drake was not travelling,

his wife

|

(280) |

A Daughter of the McGuffeys 281

went with him on his professional

rounds, by day and

night, in all weathers. When asked

where she lived,

she would answer, "In the

gig." She often carried a

book, and read while her husband was in

the sick-room.

When he rejoined her, they would go on

to the next call,

admiring the scenery on their way, the

sunsets and the

stars, or discussing business, family

affairs, philosophy

and literature. It was indeed a

marriage of true minds,

and if the children took second place,

perhaps it was

none the worse for them.

After his wife's death, Daniel Drake

worshipped her

memory as that of a saint. He never

thought of re-

marrying, and always observed the

anniversary of Har-

riet's death, alone in his study,

fasting. Both of his par-

ents had had step-mothers and had been

unhappy with

them. Perhaps this influenced him

against re-marriage.

IV

At the time I first remember

Grandfather Drake, he

must have been about sixty-five years

old. He died at

the age of sixty-seven, when I was

seven. He had been

for many years the most eminent medical

man west of

the Alleghanies, and patients came from

all parts of the

western country to consult him. It was

to Dr. Drake

that the young Abraham Lincoln

travelled for advice

when he was sick in body and soul after

the death of

Ann Rutledge. But that I only learned a

few years ago

in reading an article about Mr.

Lincoln's early love-

affair. Grandfather died before Mr.

Lincoln became

famous, but I wonder if he did not feel

more than a pass-

ing professional interest in that

homely, melancholy,

young patient who had come all the way

from Illinois

282

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

for help. I hope he was able to help

him. Grandfather

had great charm and magnetism and a

genius for

diagnosis.

To get material for his great work, Diseases

of the

Mississippi Valley,3 Grandfather travelled as far south

as New Orleans, and north to what is

now Michigan,

Wisconsin and Minnesota. He went all

over the Great

Lakes region to study diseases of the

Indians. Travel

was slow and difficult. The work of

collecting and ar-

ranging material could not be done by

skilled secretaries,

as now, and there were no reference

books to draw

from. Daniel Drake gathered his

material first-hand,

and wrote his books in the moments he

could snatch

from active medical practice. It seems

a pity that the

material he so laboriously collected

should be useless

now, but no science changes its

conclusions as quickly

as medicine. Happily many of the

diseases Grandfather

described have disappeared, and the custom

of bleeding,

which he employed, in common with other

doctors of the

day, was long ago given up.

Grandfather was working on this book

when I re-

member him, and he loved to have us

children run in and

out of his study while he wrote. Our

homes adjoined and

the communicating door was never

closed. Mother was

afraid we would disturb him, but

Grandfather said he

could work better to the sound of our

young voices. He

had learned concentration at an early

age in the crowded,

noisy, one-room school which he

attended in the wil-

derness.

Grandfather had the opposite of the

"single track

3 The exact title of this book is A

Systematic Treatise on the Principal

Diseases of the Interior Valley of

North America. Ed.

A Daughter of the McGuffeys 283

mind." His was rather a net-work

of tracks, with no

end of little side-tracks and

shuntings. He was always

writing, lecturing, travelling,

founding colleges and

"institutes" and

societies, some of which flourished and

some didn't, for his dreams always ran

beyond his

means. You can read all about his

activities in that un-

satisfactory life of him by his wife's

kinsman, Colonel

Edward Mansfield. But Daniel Drake's

biography has

never been properly written, and I'm

afraid never will

be now, for the people who knew him are

dead and

gone. My Uncle Edward's Life is

too eulogistic. Grand-

father's was a character rich in color,

and one would

need a brush that dashed and splashed

to paint him

truly.

An old resident of Cincinnati once told

your father

that he recalled seeing Dr. Drake

engage in a contro-

versy on the street, in which both

contestants came to

blows and blood trickled down their

faces. Whether

this be true I do not know. But I do

know that my

grandfather was wilful and

high-spirited, and was all

his life battling for some cause or

other. He never al-

lowed opposition to divert him from the

goal he set out

to reach, and while he was always calm

and self-con-

tained at home (as I remember him), I

can well believe

that if a hand was laid on him, he

would have struck

back. I doubt if he believed literally

in turning the

other cheek. And although well-bred

people were more

formal in their manners in those days,

they at times let

themselves "go" with a

freedom that would not be per-

mitted now. I am speaking of men in

their relations to

each other in politics and their

professions. Manners

have certainly improved there.

284

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

My mother kept house for her father

even after she

married, for he took all his meals with

us, though he

lived and worked in his own house,

adjoining. He was

very hospitable, and delighted to fill

the houses with in-

formal guests. Distinguished visitors

to Cincinnati al-

ways found their way to our doors, and

Grandfather had

a habit of rising early and going forth

to see whom he

could secure for breakfast guests.

Delightful for him,

but sometimes trying for my mother who

was his house-

keeper. When she would mildly

remonstrate, he would

reply, "Daughter, all we want is

coffee and a baked

apple." But it is not always

convenient to supply un-

expected guests with even coffee and

baked apples.

Audubon, the great naturalist, on his

journeyings

through the West, stopped for some

weeks at my grand-

father's house. (This was before my mother's mar-

riage.) He was a marvellously

interesting guest, and

he was so charmed with Dr. Drake's old

parents, who

were then living with him, that he drew

crayon portraits

of them both. These portraits of Isaac

and Elizabeth

Shotwell Drake are now in possession of

a remote branch

of the family, but excellent copies made

by Benjamin

Drake, Daniel's brother, are hanging in

my dining-

room. The frames of pine were carved by

hand by

Benjamin. I am very fond of these

portraits. Daniel

Drake said this crayon profile of his

mother was made

by Audubon when she was sixty years old,

and is correct

in its anatomy, but the expression is

too sad.

Cincinnati in those early days had a

very delightful

social atmosphere, and something of the

flavor reached

down even to little me. More knowledge

of it came to

me afterwards from my mother's tales.

The city, as I

A Daughter of the McGuffeys 285

remember it, in 1849-'50, was a

countrified small town,

with frame houses set behind shabby

picket fences, much

like those seen in parts of old

Cambridge, Massachu-

setts, where I am now living. Ashes and

garbage were

thrown into the streets, and pigs, yes,

droves of real,

live porkers roamed at will, rooting in

the refuse. I

well remember the day my mother came in

and an-

nounced to my father, in her emphatic

manner, "Alex-

ander, we are forbidden to throw

ashes or garbage into

the street. Now what shall we do

?"

My Grandfather Drake wrote a book

called The

Picture of Cincinnati. I have a copy of this quaint

little work, and there you can read

about the city in his

day. His brother Benjamin also wrote, Tales

of the

Queen City, but that book I have never seen. In 1837,

when my Uncle William McGuffey came to

Cincinnati,

it was the largest city in the West,

except New Orleans,

and had the best schools of any city

west of the Alle-

ghanies.

Mrs. Trollope published a very

unflattering descrip-

tion of Cincinnati about that time, and

I have heard my

parents say it was very ill-bred in

her, when she had

been most hospitably entertained there.

Much that she

said of our civilization was true, but

she failed to see

that beneath the crudities lay an

earnest love and aspira-

tion for the finer things of life.

My Grandfather's home was known as

"Buckeye

Hall," and he used to dispense a

mild punch from a

great bowl made of the smooth white

wood of the Ohio

Buckeye. It was from small bowls of

this same wood

that he and his brothers and sisters

had eaten their mush

and milk in the log cabin of their

childhood. The punch

286

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

must have been a temperance drink--at

least my par-

ents were strictly

"temperance."

More convenient for my mother than

Grandfather's

impromptu breakfast-parties were the

tea-parties at

which she and my father entertained

their friends.

These were not the kind of teas we

women have now-

adays. "Afternoon teas" were

unknown, and I was

amused when I went recently to the play

"Abraham

Lincoln," to see the English

author, Mr. Drinkwater,

making Mrs. Lincoln serve afternoon tea

in her Spring-

field home. Our teas resembled the

English "high teas,"

or our present day informal

supper-parties.

The guests were all seated at the

dining-room table,

which could be enlarged at short notice

for unexpected

arrivals. The food, though simple, was

abundant and

it caused no flurry when, at a whisper

from Mother, I

ran to Mary the waitress, or Anne the

cook, to say that

two, three or a larger number of extra guests

were to be

provided for. My mother had four maids,

who did the

work of six or seven modern servants. I

shall tell more

about them later. In my mother's

cook-book (Miss Les-

lie's Guide to Cookery), which I still have, but cannot

use, I am struck by the extravagant

quantities of eggs,

butter fruit and all ingredients that

the old recipes call

for.

The old gentlemen of my Grandfather

Drake's gen-

eration drank their tea from their

saucers. No tea-cups

then had handles, and it was good

manners to pour the

tea into the saucer and put the cup on

tiny plates pro-

vided. In my father's time, such a

custom was out-

lawed, but every once in a while an old

gentleman named

Mr. Symmes would come to our table and

pour out his

A Daughter of the McGuffeys 287

tea in the saucer. We young ones would

smile as if to

say, "How grotesque!" Mother

said to us once, "You

smile at Mr. Symmes because he carries

papers in his

high hat and pours his tea into his

saucer. Know well,

you youngsters, that when he was a

young man, these

habits you smile at were permitted, and

no one was

better-mannered for his time than Mr.

Symmes." A

sharp reproof for our youthful

arrogance!

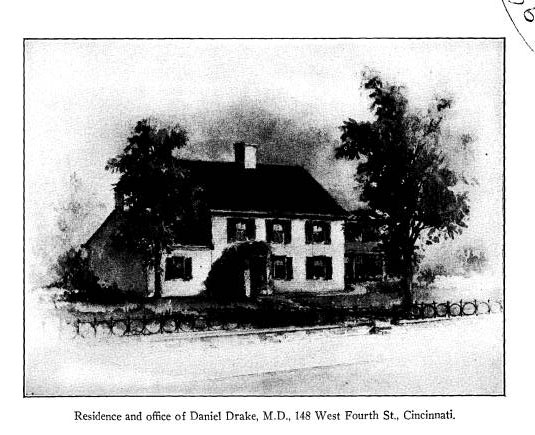

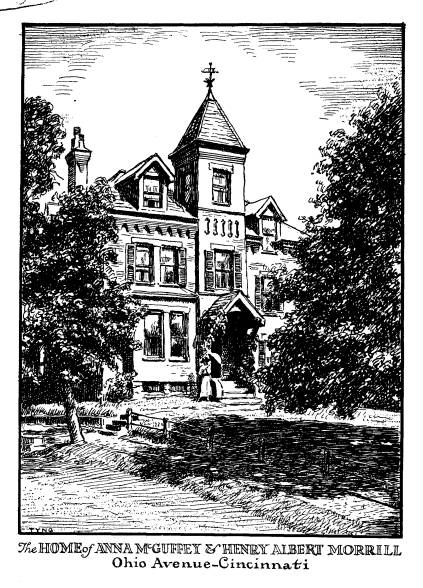

Our first home was on Fourth Street,

between Race

and Elm. This was when Grandfather was

living. This

property has become the most crowded

business section

of the city, and had my father held it,

it would have

been a valuable heritage. Later we

lived at Third and

Pike Street, in the "East

End," which had become the

fashionable residential section. I was married from

that house. Our summer home was

"Oakwood," at

Morrow, on the Little Miami river, and

our cousins the

Mansfields, had a place there, too,

called, "Yamoyden."

What glorious times we had on that hot,

dusty, Ohio

farm! I learned to swim in the muddy

river, which we

thought a delicious stream, as we had

never seen any

other.

V

And now, my dear daughter, I think it

is time that

I began to tell you of my own first

recollection for that

is what people always tell, when they

write the story of

their life. My first memories are

concerned with a very

sad time, when I was about three years

old and the terri-

ble cholera broke out in this country,

coming to Cincin-

nati by way of the Atlantic seaboard.

Nearly every family lost at least one

member. In

my father's family the one taken was my

little sister

288

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

Etta. She was about a year and a half

old and my

mother lifted me up to kiss her cold

little face as she

lay in her coffin. That kiss and that

baby face are the

first things I can remember.

There followed sorrowful days, when the

citizens, in

their ignorance, blundered in frantic

attempts to con-

trol the plague and to cure the

sufferers. Great coal

fires were kept burning in the streets

by day and by

night, to purify (?) the air. The

mistaken treatment

of the sick and dying was pitiable.

They cried for

water, water, and it was always

refused. All the medi-

cal men, including my grandfather, Dr.

Drake, were

agreed that no water should be given.

My mother, in

after years, said that no physician

should ever again

persuade her to refuse water to a sick

child, as it was

against her reason and common sense.

And happily when later (I think it must

have been

about 1866), we had a milder epidemic

of cholera, the

doctors changed their views; and my

younger brother

Edward who was thought to be dying of

cholera, was

allowed all the water he craved, and

was brought safely

to recovery by Dr. Dandridge, of

Cincinnati.

My parents had nine children, but

besides Etta, little

Daniel, the first-born, also died in

infancy. We who

grew up were seven. And except for my

darling sister

Alice, who died at the birth of her

baby, Agatha, we

have all lived to advanced age, and

have had wonderful

constitutions, like our father,

troubled only by our over-

sensitive nerves.

Charley, the eldest (named Charles

Drake, for my

mother's brother), was a dreamy,

romantic lad, preco-

cious at books, with a heart of gold,

and a mind full of

A Daughter of the McGuffeys 289

visions. He was quite unfitted to cope

with this practical

world. I think it was you, my daughter,

who called him

in later life a combination of Don

Quixote and Colonel

Newcome. He studied law and settled in

Chattanooga,

where his courtly manners and kind

heart made him a

favorite with the Southerners, except

for one thing. He

would insist on giving his seat in the

street-car to a

colored woman as readily as to a white

woman. In this

Brother Charley showed himself a true

Drake-Mc-

Guffey, for we always carry out our

convictions with

complete indifference to convention or

opposition.

Next after Charley, came myself, Anna.

I was un-

like my mother and my elder brother in

being naturally

practical, and I cannot remember the

time when I did not

help with the house and the children,

and enjoy doing it.

Then there were Edward Mansfield and

Fred, lively

mischievous boys; Alice, gentle and

lovely (like our

mother); Helen Byrd; and last, but not

least, dear little

William Holmes, your "Uncle

Billy." I was thirteen

years old when Helen was born and

fifteen when William

came. He has always been more like a

son than a

brother, and no one could have been

dearer to me as

either.

Helen grew up a perfectly beautiful

creature. She

was named for my mother's friend, Helen

Byrd, of the

famous Virginia family. Her future

husband, Robert

Parkinson, fell in love with her when

she was posing,

in a tableau vivant, as Hiram

Powers' statue of "Gala-

tea." William, of course, got his

name from Uncle

William of the Readers. My

mother told me before

their birth of their coming, and as is

usual in large fam-

ilies, we all were delighted at the

prospect of a new

Vol. XLII--19

290 Ohio Arch. and Hist.

Society Publications

baby. In those days babies were passed

freely from

hand to hand, and rocked and jounced in

cradles and

laps.

My little brother was born in January

into a cold

house, oh, so cold! No furnace, only

open grate fires

in one or two rooms. I watched the

nurse dress him.

First she put on a flannel band over

his tiny abdomen,

then a very fine cambric shirt; over

this went a long flan-

nel shirt, and then a fine muslin gown;

the gown and

petticoat reached down to the floor as

he lay on the

nurse's lap. All the undergarments,

even the diaper,

were fastened by pins--not safety pins,

they were un-

known--but long common pins! It was

quite an art

to weave these pins in and out, leaving

the points (sharp

and cruel), as far as possible from

Baby's skin. Hence

you see why even nowadays mere man will

suggest, when

a baby cries, "Perhaps a pin is

pricking."

Did I say that the baby's dress was

always short-

sleeved and low-necked, no matter what

the season,

though as a great concession to the

little one's age, a

woolen shawl was wrapped round him. But

the neck

and arms were so blue, I can see them

yet. The babies

nursed at the breast continually. When

I lay in my

trundle-bed in the night I would be

awakened by the

baby's wailing, and Mother would say,

"Never mind, go

to sleep! Baby has only lost the

nipple." Regularity in

feeding was quite unknown. No wonder babies had

colic. And how the poor little things

suffered in our hot

Cincinnati summers!

In the matter of clothing, it seems to

me our dress

was scarcely more hygienic as we grew

older. We girls

wore our frocks off our shoulders in

all weathers, until

A Daughter of the McGuffeys 291

we reached our teens, and I never saw a

knitted or

woven undergarment until I was a grown

woman. There

were no overshoes or rubbers. I never

even heard of

them until I was quite a big girl. My

father said one

day, "Elizabeth, I have heard that

one may buy a new

kind of shoe made of rubber. I think I

will bring home

a pair for you to try. They are too

expensive for the

children, and moreover, they may not be

what is claimed

for them, waterproof."

When evening came, my father appeared

with a

beautiful pair of over-shoes, made of

pure elastic rub-

ber. There was no fabric in them, they

were as soft and