Ohio History Journal

ANDREW R. L. CAYTON

"A Quiet Independence":

The Western Vision of

the Ohio Company

Speculative schemes and idealistic

visions merged in post-

Revolutionary America to produce many

new towns in the rapidly

expanding Northwest Territory. A group

of New England veterans

of the American Revolution, organized as

the Ohio Company of

Associates, established the first such

community on April 7, 1788, at

the confluence of the Ohio and Muskingum

rivers, some 200 miles

downstream from Pittsburgh. They called

their town Marietta.

Within the next several years, many of

the 594 associates of the

Ohio Company cleared land, built homes,

settled their families, and

sought fortune and security in or near

this city. Above all, they

attempted to protect and stablize their

financial and ideological in-

vestment in what they called "the

western world" by providing

Marietta with a pervasive and enduring

form and character.1

Indeed, the construction of Marietta was

the culmination of a long

contemplated effort by a highly

organized elite to establish a com-

munity designed to secure individual

fortune within the context of

communal order. In a 1790 letter seeking

to obtain increased protec-

tion from Indians, to gain the opening

of the Mississippi River, and

to assuage eastern fears about

depopulation, Ohio Company Super-

intendent Rufus Putnam told Congressman

Fisher Ames that the

"Genus" and

"education" of no other people was "as favorable to a

Andrew R. L. Cayton is a Ph.D. candidate

in history at Brown University and an

Instructor in the history department at

Harvard University.

1. "A Contemporary Account of Some

Events," in James M. Varnum, An Oration

Delivered at Marietta, July 4, 1788 (Newport, 1788), in Samuel Prescott Hildreth,

Pioneer History: Being an Account of

the First Examination of the Ohio Valley and the

Early Settlement of the Northwest

Territory (Cincinnati, 1848), 515.

Hildreth is a

detailed account of the founding of

Marietta by an early resident. For a concise,

modern narrative, see Beverley W. Bond,

Jr., The Foundations of Ohio, Carl Wittke,

ed., The History of the State of Ohio

(5 vols., Columbus, 1941), I, 275-90.

6 OHIO HISTORY

republican Government" as that of

Massachusetts. But in the 1780s

Putnam and his colleagues had been less

sanguine about the "mor-

rals, relegion and policy" of the

East. Then, without the reassuring

presence of Putnam's friend and mentor

George Washington as

president under a strong federal Constitution, some

Americans

appeared to the founders of the Ohio

Company to be repudiating or

distorting the tenets of republican

government as they defined

them. Bitter frustration and disgust

with their perception of the

United States in the 1780s made the

development of Marietta cru-

cial to the associates. Far more than a

source of profit, the city was

to serve as "a wide model" for

the "regular" and "judicious" settle-

ment of the West.2

In the East, the veterans had sensed the

imminent disintegration

of their inseparable personal and public

worlds. Believing them-

selves poorly paid for military service

in the Revolution, outraged at

a perceived loss of status when they had

expected increased respect

and prestige, self-pitying but genuinely

frightened by post-

Revolutionary America, the associates of

the Ohio Company sought

to escape what they saw as the

contentious anarchy of the East and

to bring order and stability to their

lives in a prosperous but control-

led West. Mixing materialism and

idealism inextricably, the

Marietta founders' negative view of

their economic and social posi-

tions in the 1780s nurtured positive

hopes for a certain, harmonious

existence based on a regular city and

landed wealth.

Assuming that stability could be

produced by a relatively

egalitarian dispersal of land among the

virtuous and by the example

of an orderly city, this self-appointed

elite hoped to control the

evolution of western society. In this

task, they clearly failed. For the

boats carrying the people who would

settle and develop the West

generally passed by Marietta, their

passengers perhaps put off by its

very regularity and pretensions and

interested in individual fortune

without the elitist notions of

stability and harmony that guided the

Marietta founders. Yet, if the story of

early Marietta is ultimately

one of failure, it nonetheless provides

a crucial example of the mo-

tives of some early immigrants to the

Northwest Territory.

Historians have generally seen the Ohio

Company, which was

2. Rufus Putnam to Fisher Ames, 1790,

Rowena Buell, ed., The Memoirs of Rufus

Putnam and Certain Official Papers and Correspondence (Boston, 1903),

246; Man-

asseh Cutler, An Explanation of the

Map which delineated that part of the Federal

Lands, Comprehended between

Pennsylvania, the Rivers Ohio and Scioto, and Lake

Erie; confirmed to the United States by sundry Tribes

of Indians, in the Treaties of

1784 and 1786, and now ready for

Settlement (Salem, 1787), 14.

A Quiet Independence 7

organized as a joint stock corporation

by eleven veterans of the

American Revolution on March 1, 1786, in

Boston, as the climax of a

persistent but basically economic effort

by New England officers to

obtain payment for their wartime

service. Certainly, director Man-

asseh Cutler and secretary Winthrop

Sargent's handling of the

purchase of 1,500,000 acres from

Congress in 1787 and their close

association with speculators like

William Duer and speculations

like the Scioto Company tend to confirm

that judgment. No one can

doubt that the associates were

interested in getting land and money.

Many, like Alexander Hamilton, had no

immediate intention of set-

tling in the West. Because the company

seems so much like a spec-

ulative venture, its rhetoric, while not

without defenders, especially

among local historians, has often been

dismissed as propaganda

designed to gain favors from Congress or

to attract settlers to the

purchase. One of the five directors of

the company, Manasseh Cut-

ler, even found something redeeming

about Shays' Rebellion:

"These commotions," he told

Winthrop Sargent, "will tend to pro-

mote our plan and incline well-disposed

persons to become adven-

turers." But it was not merely the

force of their rhetoric that the

associates believed would convince other

people to join. "For," as

Cutler himself noted about Massachusetts

in 1786, "who would wish

to live under a Government subject to

such tumults and confusions."

Generally believing the assumptions and

fears that lay behind

much of their exaggerated public prose

and anxious private letters,

the associates expected many others to

be receptive to their charac-

terizations of eastern society and their

hopes for the West. They did

not reject American society so much as

they wanted to stabilize it.

Largely soldiers or their sons who were

gambling on building, or

rebuilding, a more predictable life, the

active participants in the

westward migration were indeed

speculators - in the future as well

as land. Like Captain Joseph Rogers, who

had "served honorably

through the Revolution" and then

resided some time with his

friends," these veterans believed

that they had "cast" their "Bread

upon the Waters of the Revolution"

in vain, and now, like "many an

Old Soldier," marched "toward

the setting sun in hopes to find it in

the West."3

3. Manasseh Cutler to Winthrop Sargent,

October 8, 1786, quoted in Sidney Ka-

plan, "Veteran Officers and

Politics in Massachusetts, 1783-1787," William and Mary

Quarterly, IX (1952), 43; Joseph Rogers is quoted in George J.

Blazier, ed., Joseph

Barker: Recollections of the First

Settlement of Ohio (Marietta, 1958),

11. The associ-

ates are portrayed as speculative

entrepreneurs in Sidney Kaplan, "Pay, Pension,

and Power: Economic Grievances of the

Massachusetts Officers of the Revolution,"

Boston Public Library Quarterly, III (1951), 15-34, 127-42, and Kaplan, "Veteran

8 OHIO

HISTORY

The earliest origins of Marietta lay in

the increasing material and

social distress felt by its founders.

Insistent upon describing them-

selves as "reputable, industrious,

well-informed" men with status in

society, the members of the Ohio Company

assured congressmen

that "many of the subscribers are

men of very considerable property

and respectable characters." If the

associates were certain that they

were "distinguished for wealth,

education, and virtue," events and

other people appeared to them to be

threatening that crucial self-

image. Long-standing discontents with

the evolution of New Eng-

land society came to a head in the 1780s

as the future Mariettans

saw ubiquitous challenges to their

security and social status.4

Generally sons of substantial farmers

and artisans, most of the

future emigrants came from towns in an

arc around Boston, in east-

ern Connecticut, and in Rhode Island

undergoing the pangs of com-

mercial growth and the disruption of

what seemed in retrospect, at

least, to have been a more personal,

communal world. Such pre-

dominantly agricultural towns as

Pomfret, Connecticut, and

Stoughton, Massachusetts, experienced

increasing population

accompanied by a growing number of

neighborhood disputes and

stronger connections with the more

commercial and cosmopolitan

worlds of Boston and Providence.

Officers," 29-57. For discussions

of the congressional negotiations and land grant,

with emphasis on the speculative nature

of the Ohio Company, see Joseph S. Davis,

"William Duer, Entrepreneur,

1747-1799," Essays in the Early History of American

Corporations (2 vols., Cambridge, 1917), II, 131-45; Merrill Jensen,

The New Nation:

A History of the United States during the

Confederation, 1781-1789 (New York,

1950),

355-59; Richard H. Kohn, Eagle and

Sword: The Federalists and the Creation of the

Military Establishment in America,

1783-1802 (New York, 1975), 99-100;

Shaw

Livermore, Early American Land

Companies (New York, 1939), 136-46; and

Frederick Merk, History of the

Westward Movement (New York, 1978), 104-05. Not all

historians have seen the associates as

economic men, however. The most complete

and admiring study of the motives of the

associates is Archer Butler Hulbert's intro-

duction to The Records of the

Original Proceedings of the Ohio Company (2 vols.,

Marietta, 1917). Hulbert viewed the

Company as the democratic, "uniquely unselfish

and thoroughly American" (I, ciii)

carrier of New England idealism, piety, and pat-

riotism to the West. Other writers who

emphasize the communal nature and New

England origins of the company include:

Ray Allen Billington, Westward Expansion:

A History of the American Frontier, 3rd ed. (New York, 1967), 212-20, esp., 218;

Beverley W. Bond Jr., The

Civilization of the Old Northwest (New York, 1934), 9-12;

Daniel Boorstin, The Americans: The

National Experience (New York, 1965), 53-54;

Ralph Brown, Historical Geography of

the United States (New York, 1948), 215-19;

Thomas D. Clark, Frontier America:

The Story of the Westward Movement (New

York, 1959), 149-51; and Malcolm J.

Rohrbough, The Trans-Appalachian Frontier:

People, Societies, and Institutions,

1775-1850 (New York, 1978), 66-70.

4. Varnum, An Oration, 507;

Manasseh Cutler to Nathan Dane, March 16, 1787,

William Parker Cutler and Julia Perkins

Cutler, eds., Life, Journals, and Corres-

pondence of Rev. Manasseh Cutler (2 vols., Cincinnati, 1888), I, 507.

|

A Quiet Independence |

|

Certainly, economic difficulties haunted several future associates who came of age in the troubled 1760s. Manasseh Cutler's experi- ence as a young Yale graduate was not uncommon. A native of Killingly, Connecticut, a town beset with "wrangles and church feuds," Cutler unsuccessfully tried life as a merchant on Martha's Vineyard before hesitantly turning to the ministry in the late 1760s. Rufus Putnam and Benjamin Tupper, both the youngest of several sons, found their efforts at farming interrupted by service in the French and Indian War and by the necessity of supplementing their income through milling and tanning. Such insecurity com- bined with land scarcity to cause many future Ohioans to consider migration from New England in the early 1770s. Hoping to receive land as compensation for their military service, the cousins Israel and Rufus Putnam participated in a surveying expedition to the Mississippi River in 1773. They were intensely disappointed by the Crown's decision to refuse their petition.5

5. Ellen D. Larned, Historic Gleanings in Windham County, Connecticut (Provi- dence, 1899), 76; Cutlers, Manasseh Cutler, I, 73, 89. See also, Buell, Rufus Putnam, 7, 53; Samuel Prescott Hildreth, Biographical and Historical Memoirs of the Early Pioneer Settlers of Ohio (Cincinnati, 1852); and Julia Perkins Cutler, The Founders of Ohio (Cincinnati, 1888). The future Mariettans' problems and frustrations were part |

10 OHIO HISTORY

The American Revolution dramatically

raised the expectations of

such frustrated men. Among the first to

respond to Lexington and

Concord, the future emigrants with near

unanimity enthusiastical-

ly participated in the 1775 siege of

Boston. Not only did the war

provide the identifiable enemy and

social solidarity in the battle to

"restore peace, tranquility . . .

Union and liberty" to America, it

confirmed at a critical moment the

future pioneers' previously inse-

cure status as leaders in personal

communities. For the Ohio Com-

pany directors Rufus Putnam and Benjamin

Tupper of Mas-

sachusetts, James Varnum of Rhode

Island, and Samuel Holden

Parsons of Connecticut, arrived at

Boston as chief officers of local

and state militia, indisputable evidence

of their social standing and

the respect and confidence of their

neighbors. Further military ser-

vice, in the officers' minds at least,

only accorded them formal defer-

ence within the strictly hierarchical

society of the army.6

In the end, however, fighting for

American independence and re-

publican ideals seemed to make economic

and social disaster a dis-

tinct possibility for many of the future

emigrants. Sometimes enfee-

bled and rarely paid, many of those who

served their new country

spent family fortunes in mere survival.

The failure of Congress to

pay them, claimed Major-General Samuel

Holden Parsons, was in-

tensely frustrating to men who

"have expended their estates, have

of a larger pattern in New England

society resulting from an expanding population

and declining resources, especially

land. See, Richard Bushman, From Puritan to

Yankee: Character and the Social

Order in Connecticut, 1690-1765 (New

York, 1967);

Philip J. Greven, Jr., Four

Generations: Population, Land and Family in Colonial

Andover, Massachusetts (Cambridge, 1970); Robert A. Gross, The Minutemen

and

Their World (New York, 1976), 10-29, 66-108; James A. Henretta, The

Evolution of

American Society, 1700-1815: An

Interdisciplinary Analysis (Lexington,

1973), 5-39,

114-15; and Kenneth Lockridge,

"Land, Population and the Evolution of New Eng-

land Society, 1630-1790," Past

and Present, No. 39 (April, 1968), 62-80.

6. [James Mitchell Varnum],

"Ministerial Oppression, with The Battle of Bunker

Hill: A Tragedy," [1775], The

Harris Collection, The John Hay Library, Brown Uni-

versity, Providence, Rhode Island. The

future of Mariettans' revolutionary motives

seem to correspond with the patterns

outlined in Rowland Berthoff and John M.

Murrin, "Feudalism, Communalism,

and the Yeoman Freeholder: The American

Revolution Considered as a Social

Accident," Stephen G. Kurtz and James H. Hutson,

eds., Essays on the American

Revolution (Chapel Hill, 1973), 256-88; Richard L.

Bushman, "Massachusetts Farmers and

the Revolution," Richard M. Jellison, ed.,

Society, Freedom, and Conscience: The

American Revolution in Virginia, Mas-

sachusetts, and New York (New York, 1976), 77-124; Gross, The Minutemen, 30-66;

Kenneth Lockridge, "Social Change

and the Meaning of the American Revolution,"

Journal of Social History, 6 (Summer, 1973), 403-09; Stephen E. Patterson, Political

Parties in Revolutionary

Massachusetts (Madison, 1973); Gordon

S. Wood, The Crea-

tion of the American Republic,

1776-1787 (New York, 1969), 46-124;

and Michael

Zuckerman, Peaceable Kingdoms: New

England Towns in the Eighteenth Century

(New York, 1970), 220-58.

A Quiet Independence 11

hazarded their lives and health, and

sacrificed the just expectations

of their families for the salvation of

their country."7

Although their fears were often

exaggerated, the difficulties of

the future associates did seem to

escalate in the 1780s. More crucial

than what was actually happening to

these soldiers was their

perception of what was happening to

them. By their standards, post-

war America seemed unfamiliar and

unfair. A successful lawyer

and a member of the Connecticut

legislature before the war, Par-

sons, for example, believed himself

"nearly impoverished" and in

bad health at its end. Despite his

election to the Connecticut legisla-

ture in the 1780s, his fortune consisted

solely of the government

securities he received in lieu of pay

and his hopes of profiting from

"the future disposal of the

land" he surveyed in 1786 in a "subordin-

ate" position.

"Insolvent" despite his investment in the Ohio Com-

pany, Parsons died in 1789 bewailing

"the multiplied troubles

which have fallen to my lot."8

Unsuccessful "mercantile"

ventures were not infrequent, as the

former soldiers found it difficult to

adjust to a more complex econ-

omy. Colonel Ebenezer Spoat, a prewar

farmer of substantial

means, for example, tried his hand at

"mercantile affairs" in the

1780s. "Being entirely

unacquainted" with trade and having "no

taste for his new business ... in a

short time he failed; swallowing

up his wife's patrimony, as well as his

resources."9

While not all of the future associates

suffered financially in the

1780s, many complained bitterly of poor

opportunities and ineq-

uities. Solomon Drowne, a Rhode Island

veteran and future associ-

ate, spent several years preparing for a

medical career only to find

no demand for his services. Reduced to

running a pharmacy with his

sisters, the ambitious Drowne protested

being "superseded or sup-

planted in so many instances, or to

experience almost every species

of slight and neglect." "Rust

and obscurity" seemed his fate, he

lamented, "after devoting the best

years of my life to study, and

spending a pretty good estate to qualify

myself in the best possible

manner for the exercise of an important

position."10

7. Samuel Holden Parsons to Colonel

Root, August 29, 1779, Charles S. Hall, Life

and Letters of Samuel Holden Parsons:

Major-General in the Continental Army and

Chief Judge of the Northwestern

Territory, 1737-1789 (Binghamton,

1905), 266.

8. Hall, Samuel Holden Parsons, 581;

Parsons to his wife, October 18, 1788, Hall,

Parsons, 533.

9. Hildreth, Biographical and

Historical Memoirs, 235.

10. [William Drowne], "A Brief

Sketch of the Life of Solomon Drowne, M.D.," The

Drowne Papers, The Rhode Island

Historical Society, Providence, R.I.; Solomon

Drowne to Theodore Foster, July 25,

1790, William Drowne, "A Brief Sketch," 71. See

12 OHIO HISTORY

Not the lack of profit but the lack of

prestige that followed from

his relative poverty was what really

rankled Drowne. A graduate of

Brown University, a man who had studied

in Philadelphia and

Europe and dined with Thomas Jefferson,

Drowne fretted that his

economic failure was undoing his quest

for social prominence. Some

historians have criticized the

associates of the Ohio Company for

their seemingly crass pursuit of land,

their angry demands for pay

from Congress and the states, and their

careful attention to the

fluctuations in the price of the

securities they received in lieu of pay.

The associates were indeed frantic for

money, but their "grasping"

was essentially the pursuit of "a

quiet independence" that would

accord them a position consonant with

the standing they believed

they held, or should hold, in society.

To Commodore Abraham Whip-

ple, a future Mariettan, his approaching

"misery and ruin" were

incompatible with his election to the

Rhode Island legislature in the

1780s. A respected man hardly mortgaged

his farm "for a temporary

support," had it sued out of his

possession, and then faced the pros-

pect of being "turned out into the

world ... destitute of a house or a

home," even if he had lost much of

his money fighting for his coun-

try's independence. To Whipple, his land

was the foundation of his

personal independence, of his position

as a recognizable community

leader.11

In 1783, feeling neglected and slighted,

the officers of the Con-

tinental army organized the Society of

the Cincinnati, partly to

serve as a lobbying agency to get some

sort of payment from Con-

gress, but primarily to perpetuate the

formal status they had held as

army officers into a socially and

economically uncertain postwar

society. The medal given to each of its

members revealed their in-

tense longing for order, tranquility,

and respect. The decoration

also, Julia Perkins Cutler, Life and

Times of Ephraim Cutler (Cincinnati, 1890), 15;

and Rufus Putnam to George Washington,

April 5, 1784, Buell, Rufus Putnam,

224-25.

11. "Petition of settlers of

Belpre, Ohio to George Washington," March 14, 1793,

The Samuel Prescott Hildreth Papers, I,

The Dawes Memorial Library, Marietta

College, Marietta, Ohio; "Copy of

an Address from Abraham Whipple to Congress,"

The Whipple Papers, The Rhodes Island

Historical Society. Status anxiety was sug-

gested as a motive for the associates'

migration in Jacob Burnet, Notes on the Early

Settlement of the Northwestern

Territory (Cincinnati, 1847), 45. For

other examples of

the postwar difficulties of veterans,

see, Frederick S. Alvis, Jr., ed., Guide to the

Microfilm Edition of the Winthrop

Sargent Papers (Boston, 1965), 10;

Roger J. Cham-

pagne, Alexander McDougall and the

American Revolution in New York (Schnectady,

1975), 199-200, 216; Cutlers, Manasseh

Cutler, I, 155; and especially, George

Washington to the Secretary of War,

October 2, 1782, Louise B. Dunbar, A Study of

"Monarchical" Tendencies in

the United States from 1776 to 1801 (New

York, 1970),

47. Kohn, Eagle and Sword, contains

an unsympathetic analysis of the officers'

response to their problems; see Kohn,

9-39.

A Quiet Independence 13

featured Cincinnatus, the Roman hero, in

a field and "his wife

standing at the door of their cottage;

near it with a plough and

instruments of husbandry." Three

senators were offering Cincinna-

tus a sword, calling him back to the

defense of the Roman republic.

Around the edge of the whole ran the

inscription, "OMNIA RELI-

QUIT SERVARE REM PUBLICAM." On the

reverse was pictured

the sun rising over an "open

city" with "Fame crowning Cincinna-

tus" and the legends "VIRTUTIS

PRAEMIUM" and "ESTO

PERPETUA."12

The importance of Cincinnatus as an

ideal figure to the partici-

pants in the Ohio Company was immense.

Of the eleven men who

met in Boston in March 1786 to organize

the company, six were

members of the society, as were four of

the company's five directors

and its secretary. To the associates,

Cincinnatus was a model of

ideal behavior in an ideal world - for

Cincinnatus, living on the

land far away from the tumult and

corruption of cities and sacrific-

ing his happiness so that the republic

might survive the chaos of

war and enjoy the pleasure and

prosperity of peace, made a powerful

comparison with their own positions.

Cincinnatus was the embodi-

ment of the independent virtuous

republican. Firm fighters for the

American republic in war, the Cincinnati

envisioned themselves as

its staunchest farmer-citizens in peace.

They had had, claimed

Mariettan Joseph Barker, "a second

education in the Army of the

Revolution, where they heard the precept

of wisdom and saw the

example of Bravery and Fortitude. They

had been disciplined to

obey, and learned the Advantages of

subordination to Law and good

order in promoting the prosperity and happiness

of themselves and

the rest of Mankind." A

self-proclaimed elite in the defense of

harmonious republicanism, the Cincinnati

sternly warned that they

would expel any member "who, by

conduct inconsistent with a gen-

tleman and a man of honor, or by opposition

to the interests of the

community in general, or the society in

particular, may render him-

self unworthy to continue a

member."13

To their disgust, however, the officers

believed that the Revolu-

tion had not only threatened the

economic base on which their sta-

12. [C. M. Storey, ed.], Massachusetts

Society of the Cincinnati: Minutes of all

Meetings of the Society up to and

including the meeting of October 1, 1825 (Boston,

1964), xxviii.

13. Blazier, Joseph Barker, 50;

[Storey], Massachusetts Society, xxvi. On the rela-

tionship of the associates of the Ohio

Company and the Society of the Cincinnati see,

Mrs. L. A. Alderman, The

Identification of the Society of the Cincinnati with the First

Authorized Settlement of the

Northwest Territory at Marietta, Ohio, April 7, 1788

(Marietta, 1888), 24; and Hulbert, The

Records of the Original Proceedings, I, xl-xlii.

14 OHIO HISTORY

tus rested, it had released anarchic

and insubordinate elements.

Only symptomatic was the virulent scorn

directed at the Cincinnati,

as the pretensions and hereditary

characteristics of the society

raised a storm of protest throughout

New England. Mass meetings

and memorials condemned the

organization as anti-republican and

elitist. Shocked at such treatment,

Samuel Holden Parsons found

the veterans of Connecticut exposed to

"daily Insults" and "con-

temptuous malignant Neglect."

"Without honor," he said, they

could no longer live in New England and

were seeking homes in

New York or farther west. To these

veterans, it seemed clear that

something had gone wrong in the course

of revolution.14

Everywhere they looked in the

mid-1780s, the associates of the

Ohio Company found ingratitude and

growing anarchy in the East

making a prospective settlement in the

West alluring and idyllic. To

Samuel Holden Parsons, the West

represented "the Rewards of our

Toils" in the Revolution and

"a Safe Retreat from the Confusions

and Distress into which the Folly of

our Country may precipitate

us." The essential problem with

the East, according to Major

General James Varnum, was that too

rapid change and local pre-

judices were leading to disorder and

potential despotism. Indeed, the

prevalence of the former made the

latter almost necessary. Man-

asseh Cutler summarized the general

feeling when he wondered to

Winthrop Sargent, the company

secretary, in 1786 if "mankind are

in a State for enjoying all the natural

rights of humanity and are

possessed of virtue sufficient for the

support of a purely republican

government." "Dishonesty,

Villainy, and extreme ignorance" were

rampant. America, he complained,

"is the first nation" that could

make "a fair experiment of equal

liberty in a civil Community," but

it seemed to be failing in its

calling.15

Benjamin Tupper, who believed in 1787

that monarchy was "abso-

lutely necessary" to save the

United States from total chaos, saw, as

did many of the associates, a climax to

his personal and public

discontents in Shays' Rebellion in late

1786. Coming after the

actual formation of the Ohio Company,

the rebellion only confirmed

14. Samuel Holden Parsons to Alexander

McDougall, August 20, 1783, quoted in

E. James Ferguson, The Power of the

Purse: A History of American Public Finance,

1776-1790 (Chapel Hill, 1961), 156fn. On the public reaction to

the Society, see

Wallace E. Davies, "The Society of

the Cincinnati in New England, 1783-1800,"

William and Mary Quarterly, V (1948), 3-25.

15. Samuel Holden Parsons to Winthrop

Sargent, June 16, 1786, The Winthrop

Sargent Papers, The Massachusetts

Historical Society (microfilm); Manasseh Cutler

to Winthrop Sargent, November 6, 1786,

The Sargent Papers. See also, Wood, The

Creation of the American Republic, 391-467.

A Quiet Independence 15

the disillusionment and fears of the

associates. In such a crisis,

Tupper cried, "The old Society of

the Cincinnati must once more

consult and effect the salvation of a

distracted country." The Cincin-

nati did pledge their support of the

Massachusetts government,

partly because the uprising threatened

the value, even the exist-

ence, of the securities on which rested

the hopes of many to recoup or

build fortunes. But their personal

economic problems symbolized a

more general imperiling of the

republican experiment in freedom.

Not all of the Ohio Company associates

merely decried the rebellion.

Many, such as Rufus Putnam and Benjamin

Tupper, actively joined

General Benjamin Lincoln "against

the Insurgents." Others sold

their farms in utter disgust. Cutler was

right when he argued that

"these commotions will tend to

promote our plan and incline well

disposed persons to become adventurers

for who would wish to live

under a Government subject to such

tumults and confusions."16

In short, the veterans sought the

security of a well-ordered life.

Escaping the conflicts of an

increasingly unfamiliar and contentious

society, they would find "the

assaults of passion ... subdued by the

gentler sway of virtuous affection"

in the West. Solomon Drowne

hoped that "much-eyed Peace"

would "wave her Olive-branch over

the earth and at last compose the

dispositions of perverse mankind!"

Above all, "infatuated

mortals" would "learn that happiness is not

the offspring of contention, but of

mutual concession and accomoda-

tion." Marietta, Varnum argued,

would be "a safe, an honorable

asylum" where equal protection

under the law and "the labor of the

industrious will find the reward of

peace, plenty, and virtuous

contentment."17

Thus, unrewarded service, personal

economic insecurity, and a

frightening perspective on the events of

the 1780s led the associates

of the Ohio Company to forsake what they

perceived as an in-

creasingly perverse world. In the West

they would build anew along

the guidelines of eastern models, but

with control and stability

inherent in the structure of society. In

the 1790s, when the United

States seemed more secure under

Federalist rule and the associates

confronted new problems in the West,

they would find much more to

praise in the East. But on the eve of

their actual migration, disgust

and disillusionment prevailed. When

Winthrop Sargent met some

old war friends on a surveying trip in

the West, they determined, in

16. Benjamin Tupper to Henry Knox,

April, 1787, quoted in Kaplan, "Veteran

Officers," 55; Beull, Rufus

Putnam, 103; Manasseh Cutler to Winthrop Sargent,

October 6, 1786, quoted in Kaplan,

"Veteran Officers," 43.

17. Varnum, An Oration, 505, 508;

Solomon Drowne to Dr. Levi Wharton, January

21, 1792, William Drowne, "A Brief

Sketch," 80; Varnum An Oration, 506.

16 OHIO HISTORY

summarizing the feelings of the

associates, that the lands of the

Ohio would be a place "where the

veteran soldier and honest Man

should find a Retreat from

ingratitude" and vowed, once settled,

never again to visit the East "but

in their children and like Goths

and Vandals to deluge a people more

vicious and villainous than

even the Praetorian Band of Ancient

Rome."18

The pioneers, however, were well aware

that migration and rhet-

oric would not solve their problems, for

social and economic chaos

could travel west just as easily as

virtue. Reform must begin at the

foundations of society. As Samuel Holden

Parsons declared, "the

habits of an old world are in some

degree to be corrected in forming a

new one of the old materials. The

different local prejudices," he

added, "are to be done away and a

medium fallen upon which may

reconcile all." Thus, the

particular value of the Ohio Country for

erecting a more stable society was that

it was largely virgin land.

There, proclaimed Manasseh Cutler,

"in order to begin right ... will

be no wrong habits to combat, and

no inveterate systems to overturn

--there is no rubbish to remove, before

you can lay the foundation."

In Ohio, the associates planned to

create an orderly society based on

equality and security of property, and

on the institutions of the

school, church, and government, all

firmly entrenched in the purity

of a natural, regular setting.

Rhetorically, the founders of Marietta

articulated their version of hopes and

ideals that had echoed in New

England for a century and a half.19

There were to be no economic jealousies,

inequities, or insecur-

ities in the West. Near equality would

mark company holdings and

the virtue of all men would be firmly

grounded in the "quiet inde-

pendence" of landed property. The

price of an individual share was

set as $125 in gold or $1000 in

continentals, each share entitling the

owner to a city lot and farm acreage of

proportional size. The com-

pany further decreed that no person was

to own more than five

18. Winthrop Sargent, "Diary,"

July 19, 1786, The Sargent Papers. New England

society looked more appealing to the

associates in the 1790s, perhaps because it

seemed more stable. See, for example,

Gross, The Minutemen, 153-88; and Van Beck

Hall, Politics Without Parties;

Massachusetts, 1780-1791 (Pittsburgh, 1972), esp.

347-50.

19. Samuel Holden Parsons to William S.

Johnson, November 24, 1788, Hall,

Parsons, 534; Cutler, An Explanation . . ., 20. See also,

Henry Nash Smith, Virgin

Land: The American West as Symbol and

Myth (Cambridge, 1975). A harmonious,

orderly, corporate society had, of

course, long been a goal in New England society.

See, for example, Bushman, From

Puritan to Yankee, Kenneth Lockridge, A New

England Town: The First Hundred Years

(New York, 1970), and Zuckerman, Peace-

able Kingdoms.

A Quiet Independence 17

shares - within the ranks of the elite,

all were to be as economically

equal as possible. After the area had

been surveyed, plots and num-

bers were drawn and matched by lot;

again the design was to insure

a rough equality. Natural leaders would

be recognized on the basis

of merit rather than wealth and every

member of society would have

an independent stake in the perpetuation

of order. To a large extent,

the goal of equality of holdings was

achieved, at least on paper. In

1796, when the Ohio Company had

virtually ceased to exist, it in-

cluded 594 stockholders owning a total

of 496 shares. The average

share per person was .835 with a majority

of stockholders owning

one share; only forty men owned more

than three shares.20

Also of supreme importance was a

traditional New England

emphasis on education and religion.

Marietta, Solomon Drowne said

in 1789, presented a "noble

opportunity for advancing knowledge of

every kind," and for training

"rising sons of science." Just as import-

ant, associate Thomas Wallcut declared,

religion was "the most

solid foundation" and "the

surest support of government and good

morals." Thus, one of the first

orders the company gave was for the

directors to pay close attention

immediately "to the Education of

Youth and the Promotion of Public

Worship." Even a university was

planned.21

As for government, Rufus Putnam extolled

it in his charge to the

first grand jury in Marietta,

"Government is absolutely necessary

for the well being of any people, and

the General Happiness of

Society", he said, "and I

believe it will be found true that all nation-

al prosperity in every age of the world

has generally, if not always,

been enjoyed in proportion to the

rectitude of their government and

the due administration of its

Laws." Hoping to dominate the West

ideologically and materially, the people

of Marietta futilely begged

Major General Arthur St. Clair, first

governor of the Northwest

Territory, to live in Marietta rather

than Cincinnati.22

Manasseh Cutler summarized the feelings

of the associates in a

sermon delivered during his short visit

to Marietta in August, 1788.

He spoke of the coming "bright

day" when "science, virtue, pure

20. Hulbert, The Records, I,

6-10, 23-39, II, 234-42.

21. Solomon Drown[e], An Oration,

Delivered at Marietta, April 7, 1789 in Com-

memoration of the Commencement of the

Settlement Formed by the OHIO COMPANY

(Worcestor, 1789), in Hildreth, Pioneer

History, 522; George Dexter, ed., "Journal of

Thomas Wallcut," Massachusetts

Historical Society, Proceedings, XVII (1879-1880),

191; Hulbert, The Records, I, 40.

22. Rufus Putnam, "Charge to the

Grand Jury at the September Term, 1788,"

quoted in Arthur L. Buell, "A

History of Public Address in the First Permanent

Settlement of the Northwest Territory

from 1788 to 1793," (doctoral dissertation,

Ohio University, 1965), 152.

18 OHIO HISTORY

religion, and free government shall

pervade the western hemis-

phere" and argued that the settlers

could not overlook the "cultiva-

tion of the principles of religion and

virtue" if they intended to

insure their "civil and social

happiness." Religion and education

provided "the greatest aid to civil

government" and "lay the founda-

tion for a well-regulated society."

Only with such cultivation would

people "conform to ... the

community's laws and regulations" out of

"principles of reason and

custom."23

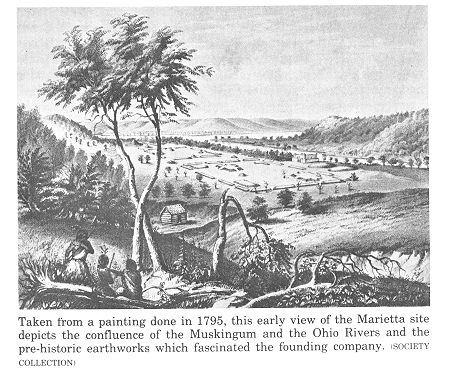

But the greatest advantage of the West

in building a more profit-

able, equitable, and thus stable,

society was its natural setting. Like

Cincinnatus, the associates hoped to

draw virtue and prosperity

primarily from the soil. In fact, these

New Englanders were ecstatic

about the advantages of an agricultural

regime both in attracting

settlers and in ordering society. In a

hyperbolic promotional pamph-

let, Manasseh Cutler praised "the

deep, rich soil" that would yield

riches for an industrious, agricultural

people and the natural water-

ways that would convey their productions

to markets. "The toils of

agriculture," he wrote, will in

Ohio "be rewarded with a greater

variety of productions than in any part

of America." The possibili-

ties of the land were often the most

significant thing settlers noted

upon arriving in the West. Associate and

merchant John May, for

example, journeying home to New England

for a visit, whiled away

the tedious trip by remembering that

"delightful country whose

swelling soil will doubly reward the

industrious planter."24

The land received its fullest tribute in

a speech by Solomon

Drowne on April 7, 1789 - the first

anniversary of the founding of

Marietta. Drowne's address was an

extended paean in praise of

agriculture. Indeed, he credited the

"virgin soil" with luring the

settlers "from your native

homes" with "charms substantial and

inestimable." The Ohio Country,

said Drowne breaking into verse,

was far from the chaos of the East:

The rage of nations and the crush of

states

Move not the man who from the world

escaped,

In still retreats and flowering

solitudes

To nature's voice attends from month to

month.

23. Manasseh Cutler, "Sermon at

Marietta," August 24, 1788, Cutlers, Manasseh

Cutler, I, 344.

24. Cutler, An Explanation ...,

14; John May, August 10, 1788, Dwight L. Smith,

ed., The Western Journals of John

May: Ohio Company Agent and Business Adven-

turer (Cincinnati, 1961), 73.

A Quiet Independence 19

Husbandry, Drowne continued, is

"the best occupation of mankind"

and "the country['s] . . . most

estimable" virtue was that it could be

practiced "under the auspices of

firmly established liberty, civil and

religious, and the mild government of

natural laws." Like Cutler,

Drowne noted that agriculture was a

"profitable" enterprise. But

more important, it was an

"honorable . . . art" that had been "the

delight of the greatest men."25

Agricultural isolation, however, was not

the goal of the early

Mariettans. As detailed in Cutler's

pamphlet, they envisioned a

wide-ranging commerce for their

settlement with the East, Florida,

and the West Indies. The bulk of their

exports down the Mississippi

or back across the mountains would be

agricultural products like

"corn, flour, beef, lumber,

etc." Yet Cutler noted the advantages of

small-scale manufacturing, as long as it

was guided by a landed

elite. "Instead of furnishing other

nations with raw materials," he

argued, "companies of manufacturers

from Europe could be intro-

duced and established in this inviting

situation, under the superin-

tendence of men of property." Far

from turning their backs on profit,

commerce, and industry, the associates

embraced its orderly and

regular development. As in all other

things, the early Mariettans

did not reject commercial development so

much as they wanted to

prevent its potentially disruptive and

perverting side effects. Their

effort was not to create an insulated

asylum, but to restructure the

world they had grown up in to make it

more stable, predictable, and

fair. And to achieve that goal, the

associates believed that society's

leading members had to ground their

lives, ideals, and fortunes

securely, if not exclusively, in the

land. For farming was the most

independent of pursuits and a clear

antidote to social contention and

economic upheaval. "To have a good

farm," Manasseh Cutler told his

Ohioan son in 1797, "to establish a

good landed interest in prefer-

ence to trade, or any other

object," was of supreme importance, "for

there is nothing in this country that

will render a man so completely

independent and secure against the

difficulties which arise from the

changes which the times, the state of

the country, and other contin-

gencies may occasion, and which are and

always will be taking place

in the world." "Freedom and

tranquility," concluded Solomon

Drowne, "may be enjoyed to

perfection, if a person be qualified with

virtue and a competence." The years

of uncertainty and contention

would end in the solid, predictable

rhythms of farming.26

25. Drowne, An Oration, 519, 523.

26. Cutler, An Explanation ..., 13.

20; Mannaseh Cutler to Ephraim Cutler, 1797,

Julia Cutler, Ephraim Cutler, 35fn;

Solomon Drowne, December 26, 1799, William

20 OHIO HISTORY

With the philosophy of republicans and

the institutions of educa-

tion, religion, and government firmly

founded on economic quality

and the practice of husbandry,

Mariettans seemed to have little to

do but build their model society along

the guidelines enunciated in

their rhetoric. While "rejoicing

nature all around us glows," they

would watch

. . . the spires of Marietta rise,

And domes and temples swell to the

skies;

Here, justice reigns, and foul

dissensions cease,

Her walks be pleasure and her paths be

peace ...

In harmony and social virtue blend

Joy without measure, rapture without

end.

In sum, said the inhabitants of Marietta

to Governor St. Clair in the

summer of 1788, "May we here find a

peaceful and happy retreat

after the toils of a calamitous war! May

we enjoy the richest fruit of

a glorious revolution!"27

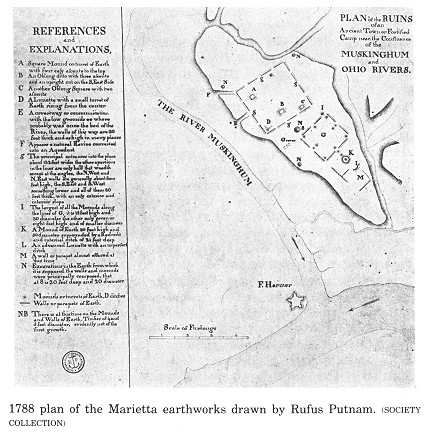

Nowhere was the nature of the society

the Ohio Company en-

visioned better reflected than in the

physical plan of Marietta. Be-

cause the city was to dominate and

epitomize the new world, on

nothing more than its structure did the

nature and future of the

associates' hopes depend. The plan of

Marietta was drawn in Boston

in the fall of 1787. If not radically

innovative, the design nonethe-

less reflected the associates' strong

emphasis on regularity and

order. The agents of the company

reserved 5,760 acres of the

1,500,000 they had purchased from

Congress at the confluence of

the Ohio and Muskingum rivers for a city

of sixty rectangular

blocks in the general form of ten blocks

wide and six deep. All the

streets were to be 100 feet wide except

for a main one of 150 feet. Of

the sixty blocks, the agents

appropriated four for public use, while

Drowne, "A Brief Sketch," 120.

See Ephraim Cutler's comments on the relationship

of land and character in Julia Cutler, Ephraim

Cutler, 89-90. On the nature of the

early American farms and the

relationship of commerce and virtue see, respectively,

James Henretta, "Families and Farms: Mentalite in

Pre-Industrial America," Wil-

liam and Mary Quarterly, 35 (1978), 3-32; and Drew R. McCoy, "Republicanism

and

American Foreign Policy: James Madison

and the Political Economy of Commercial

Discrimination, 1789-1794," William

and Mary Quarterly, 31 (1974), 633-46.

27. Return Jonathan Meigs,

"Fragment of a Speech on July 4, 1789," Buell, "A

History of Public Address," 149;

"Inhabitants on the Muskingum to Governor St.

Clair," July 16, 1788, Clarence E.

Carter, ed., The Territorial Papers of the United

States (26 vols., Washington, 1934), II, 133. On the early

government of Marietta, see

Rohrbough, The Trans-Appalachian

Frontier, 368-70; and on the early government of

the Northwest Territory, see Jack

Ericson Eblen, The First and Second United States

Empires: Governors and Territorial

Government, 1784-1912 (Pittsburgh,

1968).

A Quiet Independence 21

the other fifty-six were to be divided

into "house Lots" of 90 by 180

feet.28

In the Ohio Country, Rufus Putnam laid

out the basic gridiron

pattern specified by the agents, but in

so doing he took advantage of

"the situation of the Ground"

and put it to use as a virtuous founda-

tion for the orderly city. The most

striking feature of the land the

Ohio Company bought was a group of

ancient Indian mounds. The

huge piles of dirt, relics of the

civilization of the Adena group of

mound-builders and more than a thousand

years old, intrigued the

New Englanders. Winthrop Sargent, for

example, spent days

measuring and preparing descriptions of

the mounds. The first

thing Cutler went to see when he arrived

for his brief visit in the fall

of 1788 was the most curious of the

ancient monuments, a large

cone-shaped mound surrounded by a

ten-foot moat. The early

Mariettans were obsessed with

speculation about the origins of the

mounds. Solomon Drowne, interested in

attaching some classical

virtue to them, suggested that they were

not unlike the burial

mounds of the ancient Trojans, the

ancestors of the Roman republi-

cans. Certainly there had been an

elaborate civilization on the spot

of the Ohio Company settlement, and the

Mariettans felt a primi-

tive nobility exuding from its remnants.

What the agents resolved

about the future of the cone-shaped

mound applied for all of "the

ancient works." "Every prudent

measure," they decided, "ought to

be adopted to perpetuate the figure and

appearance of so majestic a

Monument of Antiquity." Eventually,

they made it the center of

their cemetery.29

More than merely preserving the mounds,

however, Putnam built

the town around them, superimposing the

regular plan of the com-

pany on the Indian ruins. The larger

mounds became the centers of

public squares. Naming these blocks

proved simple, for there was no

better way to secure the prominence of

virtue than to mark the

relics of primitive grandeur and

nobility with names from the Ro-

man republic. The agents named the land

around the burial mound

Conus, and reserved blocks called

Capitolium and Quadranou focus-

28. Hulbert, The Records, I, 15,

20. See also, John Reps, Town Planning in Fron-

tierAmerica (Princeton, 1969) 282-91. The comments of Manasseh

Cutler and Winth-

rop Sargent on contemporary cities

reveal an intense appreciation of"regularity" and

a dislike of the "haphazard"

in urban planning. See, for example, Cutler's 1787

observations in his diary in Cutlers, Manasseh

Cutler, I, 215, 248, 285, 306-07, 393,

429; Sargent, "Diary," July 4,

1786, The Sargent Papers; and G. Turner to Sargent,

November 6, 1787, The Sargent Papers.

29. Drowne, An Oration, 522;

Hulbert, The Records, II, 209. For travellers'

observations on Indian mounds, see John

A. Jakle, Images of the Ohio Valley: An

Historical Geography of Travel, 1740

to 1860 (New York, 1977), 68-71.

|

22 OHIO HISTORY |

|

|

|

ing on two rectangular mounds. Putnam and the agents established the final of the requisite four public squares at the confluence of the rivers and named it Cecilia. Completing the reminders of ancient Rome, the New Englanders christened their temporary stockade Campus Martius.30 The company did not rely altogether on what the land provided, however, to mark their city. They planned a large role, for example, for trees that they would plant. The agents in Boston had ordered rows of mulberry trees placed along both sides of the city streets. Placed ten or fifteen feet from the houses, the trees' duties, accord- ing to Cutler, were "to make an agreeable shade, increase the salubrity of the air, and add to the beauty of the streets." The rows of trees would also create natural sidewalks, leaving streets of the 30. Hulbert, The Records, I, 51. See also, Reps. Town Planning, 285. |

|

A Quiet Independence 23 |

|

|

|

spacious width of seventy feet. The importance of trees in adding to the beauty and regularity of the city was most clearly reflected in the strict rules for the temporary leasing of the public squares for clearing and other improvements until the danger of Indian attacks had passed. A "Mr. Woodbridge," for instance, was given a lease on the Capitolium in 1791 for eight years on the condition that he "surround the whole with Locust Trees, except at each corner there shall be an Ash - that the lines a, a, a, be Mulberrys and the lines b, b, Weeping willows, that the trees be set out within two years." The elevated mound on the Capitolium, moreover, "with the As- cents leading to the same," was to be "immediately put into Grass and hereafter occupied in no other way."31 The names of the city streets were chosen to reinforce the virtue of the residents of the regular city by perpetuating the fame of its founders and their contemporaries. While the associates gave the streets parallel to the Muskingum River numerical names, the names of modern Cincinnati marked the perpendicular avenues. 31. Manasseh Cutler to Ebenezer Hazard, September 18, 1787, Cutlers, Manasseh Cutler, I, 331; Hulbert, The Records, II, 80. |

24 OHIO HISTORY

Appropriately, the Mariettans called

their main street Washington.

Those streets to the south of it they

named Knox, Worcester, Scam-

mel, Tupper, Cutler, Putnam, Butler, and

Greene; to the north were

St. Clair, Warren, Montgomery, and

Marion. The only break in the

ranks was Sacra Via, which ran in two

parallel strips from Quadra-

nou west to the Muskingum River just

above Washington Street,

and preserved part of the noble Indian

works.

Idealistically, the associates

envisioned a diffusion of themselves

and the institutions of republican

virtue throughout the city. The

random drawings of house lots would

place the associates through-

out the city to watch over new arrivals

and to lead by example. A

church and a courthouse were planned and

built away from the

main street and the central mounds and

public square, unlike a

typical New England town where

everything focused on the central

green. The virtuous elite and

institutions were to be omnipresent so

that no sore could fester into

degeneracy and chaos.32

The final component of the Marietta plan

was the agricultural

one, for most of the pioneers intended

to become, or to reassume a

role as, Jefferson's virtuous laborers

"in the earth." While they

would live, or at least maintain a home,

in Marietta, the sharehold-

ers would farm their land for the

inseparable goals of profit and

independence. No matter how noble

farming was, however, it re-

quired markets to make it economically

secure. Many had moved to

Marietta explicitly "to live in a

Country where they can maintain

their families from the produce of their

lands better than where

they" had lived. For the first few

years Putnam and Cutler looked to

"the Constant coming in of new

settlers" to provide "a good market."

By 1800, Mariettans were building ships

and trying to develop an

ocean-going commerce. With a cargo of

flour and pork, Commodore

Abraham Whipple temporarily quit his

farm in 1800 to pilot "the

first rigged vessel ever built on the

Ohio River" to New Orleans,

Havana, and Philadelphia. By 1808,

approximately twenty ships of

150 to 450 tons had cleared from the

"port" of Marietta. By provid-

ing an outlet for agricultural products

and a means of securing other

items, this trade was designed to

reinforce both the viability and

pervasiveness of an essentially agrarian

life and the commercial

hegemony of Marietta.33

32. The church was built at Front and

Putnam Streets; the courthouse at Second

and Putnam. Quadranou was located at the

head of Sacra Via, and Capitolium at

Fifth and Washington Streets.

33. E. Haskell to Winthrop Sargent,

February 28, 1786, The Sargent Papers; Hil-

dreth, Biographical and Historical Memoirs, 160-61.

On the early commercial de-

A Quiet Independence 25

The Ohio Company greatly emphasized the

equality of the quanti-

ty of the land each associate received.

The agents divided the land

grants into several plots rather than

one large farm in order to

make their settlement in "the most

compact manner," and to equal-

ize land grants in terms of both actual

size and distance to Marietta.

The associates were very sensitive about

reassuring that their goal

of equality was realized. When Rufus

Putnam and some of the first

group of settlers argued that "the

first actual Settlers should take

their choice" of sixty-four acres

"of the best land on the Ohio and

other navigable streams," they were

abruptly overruled. Later, af-

ter the agents had been in Ohio for a

while and seen the contours of

the land with which they were dealing,

they resolved that they

should have the power to divide the land

"as equal[ly] as may be, by

dividing greater Quantities of Land to

some Lots, and less to other

Lots, to do more equal Justice."

But they later rescinded this resolu-

tion on the ground that equalizing

quality would require arbitrary

decisions and might lead to favoritism

and corruption. Eventually,

most felt, the company would build

"10 or 12 Towns" up the Musk-

ingum "which will give handsome

farms to every right in the

Propriety." Return Jonathan Meigs

told fellow associate Thomas

Wallcut that "the plan" was

"to proceed regularly down the Ohio

and up the Muskingum" in expanding

the hegemony of the com-

pany. The point, as always with the Ohio

Company, was that a

rough egalitarianism was to be preserved

at all times among the

associates. The "perfect

harmony" of the Jeffersonian idea was to be

maintained by a democracy of independent

farmers guided by the

example of an elite and the order and

beauty of the town.34

Indeed, Marietta fulfilled all the

requirements necessary for the

"perfect harmony" enunciated

in the rhetoric of its builders. The

gridiron pattern of the city gave it

regularity, order, and predictabil-

ity. These same values, as well as the

ideal of controlled egalitarian-

ism, were reinforced by the uniformity

of the house lots and the land

grants. Only the preservation of the

mounds broke up Marietta's

regularity, but even they were made to

serve the same functions.

velopment of the Ohio Valley, see,

Randolph C. Downes, "Trade in Frontier Ohio,"

The Mississippi Valley Historical

Review, XVI (1930), 467-94; Archer

Hulbert, "West-

ern Ship-building," American Historical Review,

XXI (1915-1916), 720-33; Rohr-

bough, The Trans-Appalachian

Frontier, 93-114; and William T. Utter, The Frontier

State, 1803-1825, Carl Wittke, ed., The History of the State of Ohio (5

vols., Columbus,

1942), II, 146-82, 229-62.

34. Buell, Rufus Putnam, 106;

Hulbert, The Records, I, 83; Samuel Holden Par-

sons to Manasseh Cutler, August 24,

1787, The Sargent Papers; Return Jonathan

Meigs to Thomas Wallcut, February 26, 1790,

Dexter, "Journal of Thomas Wallcut,"

190.

26 OHIO HISTORY

Unlike other western and New England

cities, Marietta focused on

the natural setting for ideological

reasons as well as convenience.

Not only did this put tangible virtue on

display, it also gave no

particular part of the city exclusive

status. Certainly Washington

Street was the "main" one, but

why live there when one could live

facing the public squares or along the

rivers? The institutions of

republican virtue were spread throughout

the city. Marietta had no

"center," in a New England

sense.

Above all, the Ohio Company's city had

space and an intended

simple elegance. The broad avenues,

lined with trees, many of them

named after modern Cincinnati, and the

several open, naturally

ornamented squares emphasized the

natural setting and the beauty

of the area, uniting classical virtue

and primitive nature. A con-

scious effort was made to hide vice and

unlovely things like stables

in alleys. Finally, the inhabitants of

the city were to perform agri-

cultural functions and own their own

land to maintain a secure

independence. Not a radical innovation

in urban planning, Marietta

represented a readjustment of the

virtues and flaws of contemporary

cities fitted to a powerful natural

setting in an attempt to preclude

anarchy and institutionalize order in

the physical structure of

society.

More was necessary to make the

Mariettans' world complete,

however, for they saw themselves as the

progenitors of a stable

society. Their efforts would be

successful only if they converted

everyone coming west to the philosophy

of order and agrarian inde-

pendence. Regular Marietta, with its

mounds, avenues, and com-

mercial hegemony was to serve that role.

In this spirit, James Varn-

um reminded Mariettans in the summer of

1788 that their "bright

example" must "add to the

felicity of others" who "having formed

their manners upon the elegance of the

simplicity, and the refine-

ments of virtue, will be happy in living

with you in the bosom of

friendship."35

The confederation government heartily

approved of the notion

that Marietta should "serve as a

wide model for the future settle-

ment of all the federal lands."

Congress had long been concerned

about people crossing illegally into the

Ohio Country from Pennsyl-

vania and Virginia without paying for

the government-owned lands

of the Northwest Territory. Wanting the

money from land sales to

help pay off the war debt, the

government as early as 1785

35. Varnum, An Oration, 507.

A Quiet Independence 27

dispatched Ensign John Armstrong and a

troop of soldiers to drive

such "squatters," "a

banditti whose actions are a disgrace to human

nature," back across the Ohio

River. Later, forts were erected along

the Ohio, including Fort Harmar at the

mouth of the Muskingum

River, to prevent further intrusions.36

On a 1786 surveying trip to the Ohio

Country, Winthrop Sargent

feared that this "powerful and

dangerous" "lawless Banditti" would

steal "the most eligible situations

and valuable Tracts of land on the

Ohio." Without the army, the land

would have no "Security" what-

soever. Fearful of anarchy and disorder

pursuing them to the West,

the associates discovered that these

supposed evils were beating

them there. Cutler hoped that settling

so near Pennsylvania would

leave "no vacant lands exposed to

be seized by such lawless bandit-

ti." In general, the Mariettans

could only have faith, as Thomas

Wallcut put it, that "our people

will be the means of introducing

more ambition and better taste,"

and that their prosperous and

regular settlement would still make the

Ohio Country, in Cutler's

words, "the garden of the world,

the seat of wealth, and the centre of

a great Empire." As such, Marietta

would epitomize "the ideas of

order, citizenship, and the useful

sciences." To preserve their status

and exercise the leadership reserved for

society's elite, precluding

the growth of anarchy in the West was

both a duty and a necessity.37

But the prolongation of the Indian wars

to 1795 kept the associ-

ates from executing their plans as

quickly as they would have liked.

The company gave land to settlers

willing to protect its purchase

from both Indians and squatters.

Sometimes, the Mariettans acted

more forcefully. When, in 1797, an

unauthorized group of people

settled near present-day Athens, Ohio,

some fifty miles to the north-

west of Marietta, Rufus Putnam

immediately dispatched a contin-

gent of "men possessing firmness of

character, courage, and sound

discretion" to prevent the land

from being "overrun" and "to estab-

lish a peaceable and respectable

settlement." Not the least of the

Mariettans' worries was that they had

long ago set aside the Athens'

township for a university that

"promised most important results."

The "substantial men" Putnam

sent pushed out a "large portion of

36. Cutler, An Explanation . . .,

14; Ensign John Armstrong to Colonel Josiah

Harmar, in Harmar to President of

Congress, May 1, 1785, William H. Smith, The

Life and Public Services of Arthur

St. Clair (Cincinnati, 1882), II, 4fn.

37. Winthrop Sargent, "Diary,"

September 7, 1786, The Sargent Papers; Cutler,

An Explanation . . . , 14; Thomas Wallcut to George Minot, [draft], October 31,

November 3, 1789, Dexter, "Journal

of Thomas Wallcut," 175. On the general rela-

tionship of squatters, government, and

land companies, as well as the early settle-

ment of the Ohio Country, see John D.

Barnhart, Valley of Democracy: The Frontier

versus the Plantation in the Ohio

Valley, 1775-1818 (Lincoln, 1970),

121-47.

28 OHIO HISTORY

the disorderly population," and

established Athens' "character as an

orderly and respectable community."

They introduced, in sum, "a

mild and refined state of manners and

feelings," and gave order to

an area that was being developed with no

other principle than that

"might makes right."38

Marietta, however, was not itself always

a paragon of virtue.

Squabbles over land and personal grievances

had split the company

directors until the deaths of Varnum and

Parsons in 1788 and 1789.

More crucial was unanticipated trouble

within the new city. The

members of the Ohio Company had settled

on their arrival in 1788

in a stockade about a mile up the

Muskingum River from the Ohio

to avoid floods, but a group of

buildings soon grew up at the conflu-

ence of the rivers, built by a mixture

of discontented associates and

itinerants who were allowed temporary

housing. These people

erected walls and named the cluster the

Picketed Point. Attuned to

river traffic, the Point became

blatantly commercially oriented,

sporting a store and a tavern.

To the associates lodged up the

Muskingum in Campus Martius,

the Point seemed reminiscent of the East

they had fled in disgust. In

February, 1790, a Marietta grand jury

debated four grievances

arising from events at the Point. The

jury resisted a demand for the

abolition of duelling on the ground that

the practice "would discour-

age cowards, and we want brave

men." But a second demand, for the

incorporation of the city to provide for

"the poor and sick strangers,"

passed, as did a request for a law

"licensing and regulating taverns."

The jury also condemned the practice of

slavery. In the same year,

Thomas Wallcut felt outraged enough by

behavior at the point to

write to Governor St. Clair complaining

about a particular tavern

keeper. Wallcut wanted "the

inordinate passions of oppressive,

cruel, and avaricious men"

restrained. The "disorderly, riotous, and

ill-governed house"of Isaac Mixer,

Wallcut concluded, was "destruc-

tive of peace, good order, and exemplary

morals upon which not only

the well-being but the very existence of

society so much depends." It

was not the pursuit of profit that

annoyed the associates, but the

lack of control and regularity that

characterized the point in their

eyes. Thus, what Wallcut requested from

St. Clair was simply a law

"licensing and regulating taverns."39

38. Ephraim Cutler, "The First

Settlement of Athens County," Hildreth, Biog-

raphical and Historical Memoirs, 410, 408, and 413.

39. Thomas Wallcut, February 2, 1790,

Dexter, "Journal of Thomas Wallcut," 181;

Wallcut to Arthur St. Clair, [draft],

1790, Dexter, 182fn. Picketed Point is described

in Hildreth, Pioneer History, 325.

|

A Quiet Independence 29 |

|

|

|

Despite several efforts, the company did not gain control over the point until the conclusion of the Indian wars in 1795 and the begin- ning of serious building. The hegemony of the virtuous elite within orderly Marietta was then relatively secure. They brought their plan to fruition and suppressed "the lawless Banditti" in or near their settlement. According to Samuel Prescott Hildreth, an early Marietta physician and historian, with the end of the Indian wars "few events of interesting character transpired .... Each man took possession of his lands, and commenced clearing and cultivating his farm."40

To an extent, then, the Ohio Company succeeded in obtain- ing financial independence for many of its associates and in build- ing a harmonious city. But physical structure could not insure that the example of Marietta would lead the entire West to a consis- tently ordered existence. The second goal was as crucial to the associates as the first. If Marietta failed to set the "tone" of the West, it would remain a utopian oasis, and a fragile one at best. Yet, the "banditti" were not easily controlled outside the confines of the

40. Hildreth, Pioneer History, 345. |

30 OHIO HISTORY

Ohio Company purchase. Organic growth,

controlled by a self-

proclaimed elite, was simply out of

place in the West, as the develop-

ment of the ironically named Cincinnati

- the second permanent,

American settlement in the Ohio Country

- testifies.

Founded in 1788, Cincinnati grew rapidly

because of its position

as the center of government and military

operations against the

Indians. The development of the city

quickly became uncontrolled

and haphazard. Commercially-oriented

Cincinnati grew along the

river with waterfront land at a premium.

Like Marietta and other

western cities being built in this era,

Cincinnati had a gridiron

pattern. But neither it nor any other

community could match the

Mariettans' obsession with virtue and

regularity. The preservation

of the Indian mounds and their

incorporation in the Marietta plan,

for example, were almost unique in

American town planning.

The speculators and profit-oriented

merchants who began to

dominate Cincinnati seemed to the

Mariettans to lack the requisite

intense commitment to the secure

independence of landed property

and controlled, organic growth.

Consequently, Winthrop Sargent,

moving to Cincinnati in 1791 to assume

the position of secretary of

the Northwest Territory, found the

situation not unlike the East in

the 1780s. He despaired that the people

of Cincinnati and Marietta

"seem never to have been intended

to live under the same govern-

ment - the latter are very like our

Forefathers and the former

(generally) very licentious and too

great a portion indolent and ex-

tremely debauched." To protect

himself, Sargent found it necessary

to surround his Cincinnati home with, of

course, a garden. John

Reps, the historian of American town

planning, concludes that an

1815 "plan of Cincinnati . . .

reveals nothing very remarkable. In-

deed, it shows every indication of being

laid out... as a speculative

enterprise and little more."

"What is more," says Reps, "in its de-

sign," Cincinnati "resembled

hundreds of similar towns that were

soon to spring up throughout southern

and central Ohio as the re-

gion began to attract land hungry

settlers from the east." Commer-

cial and haphazard Cincinnati, not

agrarian and regular Marietta,

became the model for western

development.41

People going to cash in on the

prosperity of booming towns like

Cincinnati and Louisville passed

Marietta in growing numbers in

the 1790s. The soldiers at Fort Harmar,

across the Muskingum from

Marietta, counted the passing flatboats

into the thousands. Cincin-

41. Winthrop Sargent to Timothy

Pickering, September 30, 1796, quoted in Ben-

jamin Pershing, "Winthrop Sargent: A Builder of

the Old Northwest," (doctoral dis-

A Quiet Independence 31

nati, and not Marietta, became the

center of the Ohio Valley, large-

ly for geographic and economic reasons.

Moreover, the controlled

and systematic development of Marietta

to secure an elite's notion

of virtue and stability was

anachronistic, and no doubt contributed

to its failure to dominate the West.

Even by the early nineteenth