Ohio History Journal

ANDREW BIRTLE

Governor George Hoadly's Use of the

Ohio National Guard in the Hocking

Valley Coal Strike of 1884

During the late nineteenth and early

twentieth centuries, the

United State experienced a large number

of labor strikes that in-

volved outbreaks of violence. While the

causes of this violence are

both numerous and varied, some students

of labor history cite the

intervention of police forces as a major

catalyst.1 Indeed, the list of

clashes between police and labor during

this period is long. In many

studies of strikes and industrial

violence, the police and military

forces called in to protect life and

property are depicted as partisan

forces which worked to aid industry

against labor. The extent to

which the police are viewed in this

manner varies from author to

author. Some, such as H. M. Gitelman and

John Fitch, argue that

while police forces often acted as

adversaries of labor, they were also

at times neutral and completely non

partisan. Others, such as

Samuel Yellen and Sidney Lens, tend to

view government and its

police forces as having been actively

allied with business against

labor. Lens goes so far as to make the

accusation that

In reality, however, the lawlessness was

usually created by the troops and

by the government's own denial of civil

liberties. The real purpose, thinly

disguised in phrases of

"impartiality," was to aid management in emascu-

lating unions.2

Andrew J. Birtle is a Ph.D. candidate in

American Military History at The Ohio

State University.

1. Philip Taft and Philip Ross,

"American Labor Violence: Its Causes, Character

and Outcome," The History of

Violence in America, ed. by Hugh Davis Graham and

Ted Robert Gurr, (New York, 1969), 281

(hereafter cited as Taft and Ross. "American

Labor Violence"); H. M. Gitelman,

"Perspectives in American Industrial Violence,"

Business History Review, 47 (Spring, 1973), 10, 17, 19, 20.

2. Sidney Lens, The Labor Wars, (Garden

City, N.J., 1973), 6; See also Samuel

Yellen, American Labor Struggles, ((New

York, 1936).

38 OHIO HISTORY

Even Fitch, who mentions in passing that

there were many cases

in which police forces remained neutral,

concentrates his study on

several cases in which the police acted

as a partisan force against

labor.3 That violence and

police/military intervention generally

weakened labor's position is fairly

evident. It is also true that gov-

ernors during the late nineteenth and

early twentieth centuries

sometimes called out the National Guard

in order to suppress

strikes rather than to maintain peace

and order.4 However, it is a

misconception to view the intervention

of state forces solely as an

act designed to subvert labor.

Unfortunately, those who write on the

history and causes of violent strikes in

America recount only those

instances in which the arrival of the

National Guard led to blood-

shed, while they ignore those cases

where the militia was employed

successfully as a nonpartisan force. The

Hocking Valley Coal Strike

of 1884 is one such example of a strike

in which the National Guard

was not merely a pawn of industry.

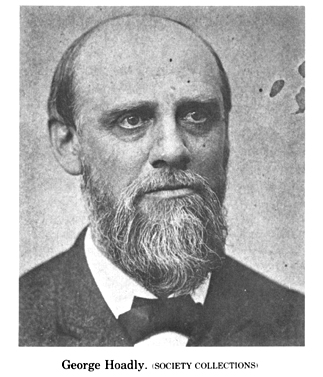

Ohio's coal fields in the Hocking Valley

region have long been the

site of violent confrontations between

labor and management. Dur-

ing the nineteenth century, poor working

conditions, low pay, and

exploitative company stores often

sparked violent strikes in the

Hocking Valley. One of the worst strikes

to hit the valley occurred

between June 23, 1884, and March 18,

1885, when miners refused to

accept a reduction in wages amounting to

ten cents for every ton of

coal mined. When violence erupted in

late August 1884, Governor

George Hoadly reluctantly decided to

send in the National Guard to

restore order and to protect life and

property. The Guard was quite

successful in achieving these goals.

Governor Hoadly's use of the

Ohio National Guard deserves to be

studied in order to counterba-

lance the all too prevalent view of the

National Guard as an instru-

ment to break strikes rather than to

preserve peace.5

The Hocking Valley is located

approximately sixty miles south-

east of Columbus and extends through

parts of Hocking, Athens,

and Perry counties. The central coal

mining area lies along a twen-

ty-mile long and fifteen-mile wide

stretch of the Hocking River.

During the early 1880s, a depressed

national economy reduced the

demand for coal, causing prices to

drop.6 This, in turn, led to signifi-

3. John A Fitch, The Causes of

Industrial Unrest, (New York, 1924), 243-44.

4. Taft and Ross, "American Labor

Violence," 297, 317, 382.

5. Frank R. Levstik, "The Hocking

Valley Miner's Strike, 1884-1885: A Search for

Order," The Old Northwest, 2 (March, 1976),

55, 61.

6. Delmer Trester, "Unionism Among

Ohio Miners in the Nineteenth Century"

(M.A. thesis, The Ohio State University,

1947), 18 (hereafter cited as Trester,

"Unionism Among Ohio Miners").

Hocking Valley Coal Strike 39

cant levels of unemployment in the

valley, and by 1884 most miners

worked only three days a week. In

addition to the overall depres-

sion, stores owned by the mine operators

persisted in charging min-

ers prices 10 to 20 percent higher than

those of local stores not

owned by the operators. These unfair

practices of the company

stores were a major cause of discontent

among miners.

Responding to the difficulties of the

early 1880s, both miners and

mine operators organized. In 1882 the

Ohio Miners' Amalgamated

Association was founded, with John

McBride as president. The fol-

lowing year several operators responded

by forming an association

whose goal was to eliminate costly price

wars and present a strong,

united front to the newly organized

miners. This organization, enti-

tled the Columbus and Hocking Coal and

Iron Company and often

referred to as the

"Syndicate," consisted of the owners of 18 mines, 5

furnaces, 570 houses (company-owned

housing for miners), and 12

company stores.8. The

Syndicate was further augmented by the crea-

tion of the Ohio Coal Exchange, a

marketing organization for inde-

pendent coal operators. Thus, by 1884

both miners and operators

were organized.

Citing poor economic conditions and low

coal prices, the operators

in the spring of 1884 asked the miners

to consider a wage reduction

from 70 cents to 60 cents for each ton

of coal mined. On April 30, the

Ohio Miners' Amalgamated Association

rejected the reduction. The

Syndicate and the Exchange responded by

unilaterally cutting

wages to 60 cents a ton on Friday, June

20. The following Monday

the miners went out of strike.9

The first month of the strike was

relatively quiet. The introduc-

tion by the operators in mid-July of 250

strikebreakers, many of

whom were foreign-born, and 100

Pinkertons raised tensions, but

not to an appreciable extent. The

striking miners peacefully per-

suaded many strikebreakers to leave,

while the local inhabitants

took pity on those strikebreakers who

were European immigrants

and whom they considered ignorant and

exploited.10 Confident that

the unskilled laborers brought in by the

operators would fail to run

7. John W. Lozier, "The Hocking

Valley Coal Miners' Strike, 1884-85" (M.A.

thesis, The Ohio State Univesity, 1963),

11, 19 (hereafter cited as Lozier, "Hocking

Valley Strike"); Ohio General

Assembly, 1885. Proceedings of the Hocking Valley

Investigation Committee (Columbus, 1885), 36-40 (hereafter cited as the Proceedings

of the Hocking Valley Investigation

Committee).

8. Lozier, "Hocking Valley

Strike," 36.

9. Ibid, 54.

10. Ibid., 61.

40 OHIO HISTORY

the mines efficiently, the miners were

content to sit back and bide

their time. The valley was so peaceful

that the operators even re-

duced the number of Pinkertons.11

As July faded into August, however, the

strikers' attitude began

to change. The number of strikebreakers

remaining in the mines

steadily increased, while the union's

strike fund steadily dimin-

ished. Consequently, the initial

sympathy for the exploited foreign

laborers soon changed to disgust towards

the "vagabonds" and "dis-

ease producing wretches."12 Further

inflaming the situation was the

fact that by September the operators had

hired 113 Pinkertons plus

an unknown number of local civilians to

act as guards.13 As early as

July, local authorities protested the

arrival of the Pinkertons to

Governor Hoadly. They charged that the

Pinkertons had "invaded"

the valley, disregarded civilian

authorities, and blocked public

roads where they crossed mine property.14

While Governor Hoadly

demanded that the roads be reopened, he

conceded that the Pinker-

tons were a legal organization and thus

could not be expelled as long

as they stayed within the law.15

The Columbus, Hocking Valley, the Toledo

Railroad (CHV&T)-

the major carrier of Hocking Valley

coal-hired its own guards

along with a private detective, John T.

Norris, to patrol and protect

railroad property in the valley.

Unfortunately, Norris was also dep-

utized by county authorites, and he soon

became the most notorious

and hated man in the valley. Without

regard for legal procedure,

Norris single-handedly arrested more

people during the strike than

anyone else. None of Norris's victims

were convicted, but he did

manage to arouse much ill will and anger

in the valley.16

As tensions increased, stray shots were

fired at guards and fights

occasionally broke out between miners

and strikebreakers. On Au-

gust 25 a mob of 400 miners almost

rioted at Buchtel following a

court ruling which allowed the eviction

of strikers from company-

11. George Cotkin, "Strikebreakers,

Evictions and Violence: Industrial Conflict in

the Hocking Valley,1884-85," Ohio

History, 87 (Spring, 1978), 143-44 (hereafter re-

ferred to as Cotkin,

"Strikebreakers, Evictions and Violence").

12. Hocking Sentinel, August 28,

1884.

13. Lozier, "Hocking Valley

Strike," 63.

14. See Henry Spurrier to Governor

Hoadly, July 14, 1884, and Elias Boudinot to

Hoadly, July 14, 1884, both in The

Papers of Governor George Hoadly, 1884-86, MS

Coll. #314, The Ohio Historical Society

(hereafter cited as Hoadly Papers); Lozier,

"Hocking Valley Strike," 64; New

York Times, July 16,1884.

15. Governor Hoadly to Elias Boudinot,

July 15, 1884, Hoadly Papers.

16. Lozier, "Hocking Valley

Strike," 66, 72; Proceedings of the Hocking Valley

Investigation Committe, 314.

|

Hocking Valley Coal Strike 41 |

|

|

|

owned housing, and the arrival of more strikebreakers. George Carr, superintendent of the CHV&T, took the opportunity to ask the governor to send in the National Guard. Governor Hoadly, however, did not feel the situation was serious enough to send in the militia.17 Realizing that violence would only aid the operators and turn the public against the miners, union president John McBride and the pro-labor Logan Hocking Sentinel urged miners to avoid violence.18 Unfortunately, these pleas for peace and order failed to stem rising passions, especially after another court decision on August 28 up- held the right of mine operators to evict striking miners and their families from company-owned housing. A flood of evictions followed this decision in late August and early September. It was this event, coupled with the growing number of strikebreakers, that proved to be the catalyst of violence in the Hocking Valley.19 On August 30, two days after the court approved the first eviction notices, the Republican and pro-business Ohio State Journal con- fidently predicted that the strike was almost broken and reassured its readers:

A number of detectives of the secret service are now at work in the valley, and any plots that may be made for violence will be known in time and the parties concocting them will be promptly arrested.20

17. Columbus Evening Dispatch, August 25, 1885; Lozier, "Hocking Valley Strike," 74. 18. Hocking Sentinel, August 28, 1884. 19. Cotkin, "Strikebreakers, Evictions and Violence," 147; Columbus Evening Dis- patch, August 28, 29, 1884. 20. Ohio State Journal, August 30, 1884. |

42 OHIO HISTORY

Whether or not this story was true, the Journal's

assertion that

"calmness now prevails among the

striking miners" was

premature.21 Late that

evening and during the early morning of

August 31, striking miners organized

several attacks on mine prop-

erty. The miners cut telephone and

telegraph lines at several places

in Hocking, Perry and Athens counties,

raided a camp of

strikebreakers at Murray City, destroyed

a coal hopper at Straits-

ville worth $4,000, and assaulted a mine

at Snake Hollow, near

Nelsonville.22 The attack on

Snake Hollow was the most violent

event. Twenty-two local citizens from

Logan guarded the mine.

Armed with rifles, shot guns, and

revolvers, a force of approximate-

ly 100 miners attacked and routed the

Snake Hollow guards at

about 1:30 A.M. August 31, killing one guard and wounding several

others.23

Wild rumors of the assault spread

rapidly during the following

day.24 Governor Hoadly, who

was in Cincinnati, was informed of the

rioting by his secretary Daniel

McConville. Throughout the day of

August 31, the governor was in constant

communication with

McConville about the situation. Hoadly

issued instructions en-

couraging the sheriffs of Hocking,

Perry, and Athens counties to do

all they could to preserve the peace

before calling upon the state for

aid. In addition, he ordered Colonel

George Freeman, commander of

the National Guard's Fourteenth Regiment

in Columbus, to begin

quiet preparations for a movement into

the Hocking Valley.25

While the governor made preparations to

return to Columbus,

mine operators spent the day

telegraphing him for aid, recruiting

civilian guards, and buying weapons in

Columbus amid new rumors

of violence in the valley. Meanwhile, an

alleged participant in the

Snake Hollow raid was arrested and jailed

at Logan.26 An angry mob

seeking the prisoner's release

reportedly gathered around the jail,

and when Governor Hoadly arrived in

Columbus late in the evening

of August 31, he received a formal

request for state aid from Sheirff

T. F. McCarthy of Hocking County:

21. Ibid.

22. Lozier, "Hocking Valley

Strike," 74; Ohio, Adjutant General's Report, 1884

(Columbus, 1885), 73 (hereafter cited as

AG Report).

23. Ohio Eagle (Lancaster),

September 4, 1884; AG Report.

24. Athens Messenger, September

4, 1884; Ohio State Journal, September 1 and 3,

1884; Hocking Sentinel, September

4, 1884; Ohio Eagle, September 4, 1884; Co-

lumbus Evening Dispatch, September 1, 1884.

25. AG Report, 268; Governor

Hoadly to Daniel McConville, Hoadly Papers.

26. Columbus Evening Dispatch, September

1, 1884; Lozier, "Hocking Valley

Strike," 76; Hocking Sentinel, September 1,

1884.

Hocking Valley Coal Strike 43

All means in my power are entirely

exhausted to repress disorder and to

protect life and property. The strikers

are cutting the telegraph wires. I am

worn out; have been going day and night

for two months. Please send

militia immediately and stop further

bloodshed. Jail is threatened.27

Upon the receipt of this note, Hoadly

telegraphed back around

midnight that troops would be sent and

asked Sheriff McCarthy how

many men he thought he needed. McCarthy

responded that he

needed ten men immediately that night to

guard the jail and 350

men to secure the valley.28 To reinforce

McCarthy's appeal, mine

operators kept up their barrage of

appeals for troops, warning that

their hired guards were demoralized and

would desert unless mili-

tary aid was forthcoming.29

Having made the decision to send in the

Guard, Governor Hoadly

sounded the riot alarm in Columbus and

sent orders for National

Guard units stationed in Columbus to

assemble. But after having

aroused the city's populace in panic and

confusion, the governor

suddenly had second thoughts. To begin

with, Superintendent Carr

of the CHV&T telegraphed him that it

was unwise to move the

militia in at night when it could be

ambushed. Carr suggested that

if the governor would ask his officers,

they would verify this fact.30

More importantly, State Legislator Allen

0. Myers paid a late night

call upon the governor and purportedly

advised him of the political

costs of sending the Guard into the

valley. When the governor

emerged from this private meeting, he

announced that he would

personally go to the valley and inspect

the situation before deciding

whether to employ the militia. Hoadly's

decision to travel through

the strike region was wise. Since most

of his information came from

rumors or mine operators and railroad

men, he needed to form his

own opinion of the situation. Moreover,

his inspection tour might

help defuse the situation. Finally, the

trip might eliminate adverse

portrayals of him as a heartless,

pro-industry and anti-labor gov-

ernor.

27. AG Report, 269; Sheriff T. F.

McCarthy to Governor Hoadly, August 31,1884,

Hoadly Papers.

28. Governor Hoadly to T. F. McCarthy,

August 31, 1884, Hoadly Papers; McCar-

thy to Hoadly, September 1, 1884, AG Report, 271.

29. W. B. Brooks to Governor Hoadly,

September 1, 1884; M. M. Greene to Hoadly,

September 1, 1884; T. F. McCarthy to

Hoadly, September 1, 1884. All of the above

telegrams are in AG Report, 272.

30. George Carr to Governor Hoadly,

September 1, 1884, Hoadly Papers. The units

called to arms in Columbus were the Fourteenth

Regiment, the Governor's Guard,

and the Duffy Guard.

44 OHIO HISTORY

While this was a sensible policy,

Hoadly's vacillation did not go

without criticism in the press. The

politically independent Co-

lumbus Evening Dispatch commented:

People can not see the necessity of

calling the men out at that hour of the

night and throwing the whole city into a

state of confusion and excitement

by sounding the alarm if their services

in quelling the riot were not needed;

and if there was sufficient cause to

call them out why they were not sent to

the point of trouble instead of being

quartered in this city, a considerable

distance from the riotous district ...

Many members of the National Guard

expressed their indignation this

afternoon at being called out at midnight

and forced to remain in the Armory

during the day.31

Party politics, however, played an

important role in press apprais-

als of Governor Hoadly's actions,

especially since 1884 was a pres-

idential election year. The Republican

press criticized Governor

Hoadly, a Democrat, for his indecision

during the early stages of the

"reign of terror," feeling

that he should not have delayed at all in

sending the troops. The Cleveland

Herald opposed Hoadly's trip into

the valley and queried, "Who is

Governor of Ohio, George Hoadly or

Allen O. Myers? The impression gains

ground that Hoadly is Gov-

ernor de jure and Allen O. Myers de

facto."32

The Democratic and pro-labor press, on

the other hand, praised

Governor Hoadly for his compassion and

wise decision in personally

examining the valley before committing

the militia. The Democra-

tic press even launched its own

political offensive by claiming that

James G. Blaine, the Republican

candidate for President, was a

major investor in Hocking Valley mines.

All in all, some criticism of

Hoadly's vacillation seems justified.

However, as the New York

Times pointed out, Hoadly's ultimate decision was prudent

rather

than cowardly.33

At 2:00 A.M on September 1, Governor Hoadly left on a special

train for the Hocking Valley. He

travelled throughout the day and

stopped to address an assembly of

citizens at Nelsonville. He stated

that no person-miner or operator-had the

right to violate the law,

31. Allen O. Myers was a Franklin County

Democratic member of the Ohio House.

For both the meeting and criticism of

it, see Columbus Evening Dispatch, September

1,1884; Cleveland Herald, September

3,1884; Logan Republican Gazette, September

4,1884.

32. Ohio State Journal, September

2, 1884; Athens Messenger, September 4, 1884;

Cleveland Herald, September 2, 3, 1884; Logan Republican Gazette, September 4,

1884.

33. Hocking Sentinel, September

4, 1884; Columbus Evening Dispatch, September

1, 1884; New York Times, September

2, 1884.

Hocking Valley Coal Strike 45

and that he would rather rely upon the

good behavior of the citizens

themselves than to call in the militia.

When a member of the crowd

asked, "What's to become of the

people turned out of houses?" Hoad-

ly responded, "I will send them

tents." Tents were sent in early

September, although most of them were

returned as evictees had

taken shelter with friends and family.34

After viewing the strike situation,

however, Hoadly felt compel-

led to deploy three companies of

Guardsmen in the region. The units

employed were probably chosen for their

proximity to the valley and

had been notified on August 31 of

possible operations. They con-

sisted of companies from Lancaster,

Circleville, and New Lexington.

Sheriff McCarthy stationed these units

on September 1 at Logan,

Sand Run, and Longstreth,

respectively.35 On the following day the

Lancaster Company was moved from Logan

to Snake Hollow. Once

in place, all units established

defensive perimeters around the des-

ignated mines. The units had been

mobilized hastily, and conse-

quently some of the men had only two or

three rounds of ammuni-

tion each on the first night.36

The Guard's first night in the valley

was spent quietly. In fact, the

situation seemed secure enough that

Governor Hoadly dismissed

the troops being held in readiness in

Columbus the following day.

Throughout September 2, however, mine

operators kept up a bar-

rage of telegrams requesting more

troops.37 Even Captain James

Teal of the New Lexington unit at

Longstreth requested two to three

companies of reinforcements out of fear

that his small company of

thirty-three men might be surrounded. In

light of these appeals,

Governor Hoadly decided to send an

additional company to the

Hocking Valley. Since Adjutant General

Ebenezer Finley was ill,

34. On August 30, George Snowden, a

prominent local citizen, had requested that

Governor Hoadly send tents to

house-evicted miners at Buchtel. Several other

appeals followed on September 8 and 15.

See George Snowden to Governor Hoadly,

August 30, 1884; Hoadly to Snowden,

August 30, 1884; Snowden to Hoadly, Septem-

ber 8, 1884; Adjutant General Finley to

Snowden, September 15, 1884. All of the

above are in Hoadly Papers; also see Hocking

Sentinel, September 4, 1884; Trester,

"Unionism Among Ohio Miners,"

22; Ohio Eagle, September 4, 1884; Columbus

Evening Dispatch, September 1, 1884.

35. The companies involved were Company

E, Sixth Regiment, Company F, Sixth

Regiment, and Company A, Seventeenth

Regiment. See AG Report, 74.

36. Lieutenant L. O. Anderson to

Governor Hoadly, September 1, 1884, Hoadly

Papers.

37. The units in Columbus were the

Fourteenth Regiment and the Duffy and

Governor's Guards. Colonel Thomas T.

Dill to Colonel George Freeman, September 2,

1884. AG Report, 273; M. M. Green

to Governor Hoadly, September 2, 1884, and J. R.

Buchtel to Hoadly, September 2, 1884,

both in Hoadly Papers. Also see Ohio State

Journal, September 2, 1884; Columbus Evening Dispatch, September

2, 1884.

46 OHIO HISTORY

Colonel Thomas T. Dill, the assistant

adjutant general, was sent

with the company and was given command

of all Ohio Guard units

in the Hocking Valley.38

Governor Hoadly's instructions to

Colonel Dill clearly indicated

the moderate tone that would

characterize the Guard's occupation.

Dill's primary task was to protect life

and property, and he was to

act only under the direction of the

civil authorities and in close

consultation with the county sheriffs.

While the Colonel could re-

quest reinforcements whenever needed,

the governor impressed

upon him that the troops should be

withdrawn as soon as possible.39

The Guard was to be neither a long-term

garrison nor a private

police force for the operators, but

rather an intermediary through

which peace and order could be quickly

restored. To reinforce his

desire that the Guard act solely as a

nonpartisan peacekeeping

force, Hoadly expressly forbade the

Guard to fire weapons unless

fired upon first.40

Tension was high the first several days,

but rumors of violence

usually proved to be false. Railroad and

mine executives often re-

ported "information" on

impending riots in efforts to maintain the

National Guard's presence in the valley,

but these riots never

occurred.41 As early as

September 3, the Columbus Dispatch sum-

med up the situation with the headline

"No Work for Troops," while

Guard Captain Albert Getz described the

situation at Snake Hollow

as being "quiet as a

graveyard."42 Sporadic gunshots at night at or

near National Guard pickets were quite

common but posed no se-

rious threat. Such gunfire became so

commonplace that eventually

it was not even recorded in the daily

reports - in part so that those

at home would not be unnecessarily

anxious for the safety of their

friends and relatives in uniform.43

Despite the general calm, pressure from

the Syndicate and

CHV&T to maintain and increase

militia strength in the valley

38. The new unit was Company K,

Fourteenth Regiment. Captain James Teal to

Governor Hoadly, September 2, 1884, AG

Report, 274.

39. AG Report, 274, 275; Governor

Hoadly to Colonel Thomas Dill, Hoadly Papers.

40. Ohio. Records of the Ohio Adjutant

General's Office, Hocking Valley Coal

Strike, 1884, Vol. 154, Ohio Historical

Society (hereafter cited as Records of AG).

41. AG Report, 75; George Carr to

Colonel Thomas Dill, September 3 and 4, 1884,

in AG Report, 276.

42. Captain Albert Getz to Colonel

Thomas Dill, September 6, 1884, Records of

AG; Columbus Evening Dispatch, September

3, 1884.

43. Captain Charles Brown to Colonel

Thomas Dill, September 3, 1884, 275; Dill to

Governor Hoadly, September 4, 1884, 276,

and September 7,1884, 277, all in AG

Report; Lieutenant

L. O. Anderson's Report, September 5,1884, Records of AG; Co-

lumbus Evening Dispatch, September 9, 15, 17, 19, 1884.

Hocking Valley Coal Strike 47

continued throughout September.44

Stevenson Burke, vice president

of the CHV&T, sent repeated letters

to Governor Hoadly warning

that Ohio's reputation for

"lawlessness" would drive business out,

including the CHV&T. Burke

criticized Hoadly's "dallying" and

"armed neutrality" and called

for an end to mob rule in Ohio.45

Republican papers picked up on this

theme. The Ohio State Journal

reported that the miners cursed the

military and would rejoice as

soon as it was withdrawn, while the Athens

Messenger warned that

violence was still possible "in the

absence of a sufficient military

force." Interestingly, the Messenger

was not above performing an

about-face in the interest of scoring

some political points, for it

reminded miners that it had always been

Democratic governors who

had called in troops against strikers.46

The local civil authorities were also

apprehensive. Sheriff McCar-

thy and his deputies were easily

frightened and constantly feared a

renewed outbreak of violence. Governor

Hoadly soon began to dis-

trust McCarthy's judgment. Upon

receiving reports from McCarthy

that many railroad bridges in the area

were threatened, Hoadly

asked Colonel Dill to give his own

assessment of the situation, bear-

ing in mind that "I do not desire

troops to remain longer than it is

necessary to preserve order and sustain

civil authorities." In reply,

Dill reported that the bridges were not

in danger and that the pre-

sent number of troops was adequate.47

However, according to Co-

lumbus newspapers, even Colonel Dill

believed that while things

currently remained calm, the miners

would quickly drive off the

strikebreakers as soon as the troops were

removed.48 Nevertheless,

Governor Hoadly was anxious to remove

the Guard as soon as possi-

ble. As early as September 3 he

indicated his desire to withdraw the

company at New Lexington. He left the

decision up to Colonel Dill's

judgment, and on September 9 the unit

was pulled out.49

44. President of the Pittsburgh,

Cincinnati, and St. Louis Railroad to Governor

Hoadly, September 6, 1884, Hoadly

Papers.

45. Stevenson Burke to Governor Hoadly,

September 7 and 8, 1884, Hoadly Pa-

pers.

46. Ohio State Journal, September

3 and 4, 1884; Athens Messneger, September 1

and October 9, 1884.

47. Governor Hoadly to Colonel Dill, and

Dill back to Hoadly, September 3, 1884,

AG Report, 275;

Dill to Hoadly, September 9, 1884, Hoadly Papers.

48. Deputy Sheriff W. E. Hamblin to

Sheriff T. F. McCarthy, September 19, 1884,

Hoadly Papers; McCarthy to General

Ebenezer Finley, September 11, 1884, Records

of AG.

49. Governor Hoadly to Colonel Thomas

Dill, AG Report, 276; Hoadly to Dill,

September 7, 1884, Records of AG; Dill

to Hoadly, September 9, 1884, Hoadly Papers;

Columbus Evening Dispatch, September 8, 1884.

|

48 OHIO HISTORY |

|

|

|

By the second week in September company commanders reported that the troops, growing weary of their arduous duties, were re- questing relief.50 Fearing that the militia might be completely with- drawn, Sheriff McCarthy warned General Finley that he could not assume responsibility for peacekeeping in such an eventuality.51 In a report on September 11, Colonel Dill expressed fear of renewed conflict once the troops were pulled out and agreed with Sheriff McCarthy that the valley was not yet ready for the removal of the Guard. While acknowledging that a large force of civilian guards could protect life and property equally well, Dill felt that replacing the troops with civilian guards would result in greater antagonisms and renewed violence, and thus, in the light of already-present ten- sions, such a move was not advisable.52 Finley, who had recovered from his illness and was now in the Hocking Valley, concurred with Dill's assessment of the situation. Finley reported, "it is not the

50. Captain Albert Getz to Colonel Thomas Dill, September 9, 1884, Records of AG; Dill to General Finley, September 11,1884, AG Report, 278. 51. Sheriff McCarthy to General Finley, September 11, 1884, Records of AG. 52. Indeed, many of the disturbances after the arrival of the National Guard were due to unruly Pinkertons or trigger-happy civilian guards who nervously discharged their guns on the slightest pretense. One striker even claimed that he welcomed the militia since it protected the people from the provocations of the operator's hired guns. See George Snowden to Governor Hoadly, September 8, 1884; W. Dalrymple to Hoadly, September 9, 1884; and Andrew [?] to Hoadly, September 18, 1884, all in Hoadly Papers; Report of Colonel Dill to General E. Finley, September 11, 1884, Records of AG; Hocking Sentinel, September 11 and 18, 1884; Columbus Evening Dispatch, September 8, 1884. |

Hocking Valley Coal Strike 49

number but the moral effects of the

soldiers in the valley is what

preserves the peace."53

As a result of these recommendations,

Governor Hoadly decided

to keep a force in the valley by

withdrawing the three companies

presently there and replacing them with

three other companies. On

September 12, companies from Upper

Sandusky, Bucyrus, and Co-

lumbus replaced the garrisons at Snake

Hollow, Longstreth, and

Sand Run, respectively.54 The

rotation of troops went smoothly, and

the new units settled down to the

monotonous routine of guard duty.

The valley was now so quiet that

marksmanship competitions and

baseball games seem to have been the

Guard's main occupation.

Rumors and stories of impending riots

were the only things that

broke the monotony.55 The

tranquility of the valley, however, raised

the difficult question of when the

troops could be withdrawn. If the

region was once again stabilized, why

should the Guard remain? On

the other hand, a premature withdrawal

might precipitate renewed

violence and the embarrassment and

expense of having to return

troops to the area. Throughout

September, pro- and anti-labor forces

endeavored to pressure Governor Hoadly

into making a decision

favorable to their position.

On September 28 a large sympathy rally

was held for the miners

at the Columbus City Hall. The meeting

passed a resolution that

denounced the employment of militia in

the Hocking Valley as not only

without justification but a perversion

of our constitution and laws and

'calculated to subvert our free

institutions and hand our state over to the

keeping of a corporate oligarchy whose

only idea of right is its power to

compel obedience to its monstrous

demands'; and demands, in the name of

the laboring masses of Ohio, the

immediate withdrawal of the militia from

the valley . . .56

The Columbus Dispatch reported a

"deep disgust" among the

population in the valley towards the

needless presence of the militia

and wondered, considering the reported

cost of $400 per day, how

long the idle Guardsmen would be

employed, while the pro-labor

53. General E. Finley to Governor

Hoadly, September 11, 1884, Records of AG.

54. The units involved were Company B,

Second Regiment, Company A, Eighth

Regiment, and Company B, Fourteenth

Regiment; see AG Report, 75.

55. Columbus Evening Dispatch, September

18, 19, and 20, 1884; the Hocking

Sentinel made

fun of the army of "war correspondents" that had descended upon the

valley eager for action, but who were

now disappointed. See Hocking Sentinel,

September 11, 18, and 25, 1884.

56. Columbus Evening Dispatch, September

29, 1884.

50 OHIO HISTORY

Hocking Sentinel assured its readers that all would remain quiet if

the militia were withdrawn.57 Even

the Republican Ohio State Jour-

nal, which had strongly attacked Hoadly for his delay in

sending

troops, and then praised him for keeping

the troops in the valley,

now turned about once again to question

Hoadly's policy. On

September 24 the paper stated that men

of the Guard unit at Sand

Run felt that their presence was no

longer needed and that many of

them were losing valuable work days

while on duty. Three days

later the Journal reported that

while Syndicate representatives

were asking the governor for the

retention of troops in the valley,

many people were beginning to wonder if

the troops were still neces-

sary. Thus even one of the Syndicate's

strongest supporters was

beginning to question the value of

maintaining troops in the valley.

The Journal stopped short of

actually calling for a withdrawal, but

demanded that the governor soon make up

his mind so that those on

duty could return to their homes.

Meanwhile, the Republican New

Lexington Tribune went so far as to accuse the governor of main-

taining a standing army in the valley

"because of the fearful soul of

the Democratic Sheriff down there that

imagines that deviltry of

some kind or other will be perpetrated

unless he has an army at his

heels."58

On September 17 General Finley informed

Hoadly that he felt all

the troops could be withdrawn within the

next two days. The gener-

al wrote, "There must come a time

when we must leave, and in my

judgment a week or two weeks hence will

find affairs in the same

condition as they are now, if the soldiers

remain."59 Finley admitted

that violence might reemerge once the

soldiers left, but with no end

to the strike in sight, he questioned

how long the retention of troops

could be justified when there was no

longer any disorder. Rather

than the operators utilizing the state,

Finley felt that they should

pay for their own protection.60 Finally,

he recommended that all

three Guard companies be removed at the

same time-withdrawing

one unit at a time would tend to cause

dissatisfaction in the remain-

ing units, without offering any greater

security. Since the Guard's

four outposts-Murray City, Sand Run,

Snake Hollow, and Long-

57. Columbus Evening Dispatch, September

23,1884; Hocking Sentinel, September

25, 1884.

58. Ohio State Journal, September

2, 10, 14, 24, and 27, 1884; New Lexington

Tribune, September 25, 1884.

59. General Ebenezer Finley to Governor

Hoadly, September 17, 1884, Records of

AG.

60. Ibid.

Hocking Valley Coal Strike 51

streth-were not mutually supportive, the

withdrawal of one com-

pany would leave that particular area

exposed to attack. That

Snake Hollow had no Pinkertons, and Sand

Run only three, meant

that the removal of one company would

effectively undermine the

entire defense of the valley. Thus, if

withdrawal were to be the

policy, Finley recommended withdrawing

all of the units simul-

taneously.61

Governor Hoadly, whose policy had always

been to remove the

troops as soon as possible, did not

accept Finley's last suggestion.

Perhaps out of caution, or in

consideration of the appeals from the

mine operators, the governor chose to

withdraw the Guard in

piecemeal fashion. When the Guard

company from Bucyrus, after

fourteen days service, heard rumors that

it would be held in the

valley for an extra week, both the

Guardsmen and businessmen

from Bucyrus lodged a formal protest

with the governor. In re-

sponse, the governor immediately

replaced the Bucyrus company

with one from Chillicothe on September

23.62

The permanent withdrawal of units began

on September 27, when

General Finley returned the Guard

detachments at Murray City to

their respective companies and removed

the troops from Sand Run.

Two days later the garrison at Snake

Hollow was relieved. Finally,

on October 3 the last National Guard

unit, the Chillicothe unit

which had replaced the Bucyrus company

on Setember 23, was re-

moved from Longstreth.63 The

occupation of the valley had lasted

slightly over one month.

The strike, however, dragged on. As many

had feared, the miners

renewed their campaign of violence two

weeks after the National

Guard withdrew. On October 12, strikers

set a mine at Shawnee

ablaze, and three days later six more

mines and a hopper were set on

fire. Then on November 5, three railroad

bridges were destroyed and

three hundred miners unsuccessfully

attacked mine property at

Murray City.64 Sheriff

McCarthy wired the governor and requested

the return of the militia. Governor

Hoadly, familiar now with

McCarthy's excitability, refused to

believe that the sheriff had done

all in his power to prevent disorder.

Instead, Hoadly made another

appeal to the local citizens to restrain

themselves and foresake vio-

61. Columbus Evening Dispatch, September

15, 1884; General Ebenezer Finley to

Governor Hoadly, September 17, 1884, Records of AG.

62. The new unit was Company A, Sixth

Regiment; See AG Report, 75.

63. Ibid., 76.

64. Lozier, "Hocking Valley

Strike," 79; AG Report, 79; Athens Messenger, Novem-

ber 13, 1884.

52 OHIO HISTORY

lence, threatening that if they did not,

the Guard would indeed

return.65

The last major acts of violence, which

included another attack by

strikers at Murray City, occurred in

December and January, result-

ing in the destruction of some mining

and railroad property. In

mid-December Sheriff John Boden of

Athens County requested two

militia companies in response to this

violence, but once again the

governor denied that the situation was

serious enough to warrant

the introduction of state troops.66

These attacks, by and large the last

desperate acts of a few trou-

blemakers, were aimed mostly at

property, and few injuries re-

sulted. Much more common were acts of

petty larceny committed by

miners who were now destitute after

months without work. While

there was some criticism of the

governor's refusal to send military

aid, most people clearly saw that the

situation was moving steadily

against the strikers.67 By

November, 1500 strikebreakers were at

work in the Hocking Valley, and by

January 1885 all the Syndicate

mines but four were back in operation.

By the second week of Febru-

ary the last Pinkerton left the valley,

and on March 18, 1885, the

miners' union officially accepted the 60

cents a ton rate. After nine

months, the strike was finally over.68

With the end of the strike in early 1885

the Ohio Assembly

launched an investigation to determine

both the causes of the strike

and the possible means of preventing

such a calamity in the future.

The committee conducting the

investigation also endeavored to give

both sides a chance to explain their

positions to the public. During

the investigation, union president John

McBride testified that he

believed that the operators hired

Pinkertons to provoke the mines

into a riot, hoping that this would lead

to state military interven-

tion. In McBride's opinion, the

operators desired the military's pre-

sence in order to demoralize the miners

and break the strike.69

Whether or not the operators sought to

provoke an incident that

would invite military action, there is

no doubt that they eagerly

sought large numbers of troops to

protect their mines and

strikebreakers. The operators and the

CHV&T lobbied for a forceful

reaction from Governor Hoadly after the

Snake Hollow assault, and

65. AG Report, 79.

66. Lozier, "Hocking Valley Strike,"

84; Athens Messenger, December 25, 1884.

67. H. B. Payne to Governor Hoadly,

November 6, 1884, Hoadly Papers.

68. Lozier, "Hocking Vslley

Strike," 61, 83, 87, and 89.

69. Proceedings of Hocking Valley

Investigation, 314.

|

Hocking Valley Coal Strike 53 |

|

|

|

the Republican press, led by the Ohio State Journal, queried, "Have we a Governor? Have we protection for life and property in Ohio?" when Governor Hoadly hesitated in sending troops into the Hocking Valley. The Journal added that state troops should have been pro- vided from the beginning of the strike, and that it was wrong for private citizens (ie., mine operators) to be forced to hire Pinkertons to do what the state had an obligation to do. This, claimed the Journal, was an "outrage."70 Claiming that the governor's delay in sending troops during an 1884 Cincinnati riot-a riot caused by a court's acquital of an ac- cused murderer-led to increased bloodshed and property destruc- tion, the Republican press attacked the governor: first, for delaying the introduction of troops into the valley, and second, for sending only 180 of the 350 men Sheriff McCarthy requested. Responsibility

70. Ohio State Journal, September 2 and 3, 1884; Cleveland Herald, September 3, 1884; Logan Republican Gazette, September 4, 1884. |

54 OHIO HISTORY

for any loss of life or property due to

inadequate troop strength,

warned the Athens Messenger, rested

solely with Governor Hoadly. 71

Except for Governor Hoadly's initial

indecision whether to send

the Guard and his premature mobilization

of the Guard at Co-

lumbus during the night of August 30-31,

he responded effectively

to the situation in the valley.72 The

manner in which he inter-

vened-both his trip to the valley and

his subsequent judicious use

of the Guard-demonstrated to the miners

that he was not a tool of

big business, but rather a man of

moderation whose primary goal

was to restore peace and order. The

governor's actions during the

strike, including his providing tents

for evicted families, indicate

that he was in fact sympathetic to the

plight of the miners.

Although the miners protested the

Guard's presence, they seemed

satisfied with the individual conduct of

the Guardsmen. Indeed, the

very absence of press coverage of the

Guard's activities during the

occupation indicates that the Guard

acted prudently. Not once did

the Guard openly clash with strikers,

nor did it injure any miners.

The Guard itself, however, suffered

three casualties during its

month-long occupation-one trooper died

of typhoid, a second was

accidentally shot and killed by another

Guardsman, and a third shot

himself in the leg.73

Commenting on the conduct of the Guard,

the pro-labor Hocking

Sentinel praised the departing Lancaster company on September

25:

They are friendly fellows and performed

not very agreeable work with

kindness. Though sympathizing with the

strikers, yet allegiance to their

State compelled them to erect

breastworks to protect life and property, and

the miners, realizing their situation,

treated them respectfully.74

Upon the withdrawal of the last troops

from the valley in October,

the Sentinel reiterated this

theme:

The soldiers acted as mild conservators

of the peace, protecting life and

property, respecting alike the rights of

miners and operators. They did no

harm. They imposed upon no one. They

insulted nobody ... they did their

duty in orderly, gentlemanly style,

leaving a kindly opinion upon the minds

of all with whom they came in contact.75

71. Ohio State Journal, September

2, 1884; Athens Messenger, September 4, 1884.

72. Ohio Eagle, September 11, 18,

1884; New Lexington Herald, September 11,

1884.

73. AG Report, 76.

74. Hocking Sentinel, September

25, 1884.

75. Hocking Sentinel, October 9,

1884.

Hocking Valley Coal Strike 55

The Guardsmen, many of whom were common

workers, artisans,

and farmers, generally sympathized with

the plight of the strikers.

In fact, there were some fears that the

troops would perhaps be too

sympathetic. On September 1,

Superintendent Carr informed Gov-

ernor Hoadly that deputy Sheriff W. E.

Hamblin of Hocking County

desired two companies of reinforcements

from Columbus because

the troops the governor had sent were

largely from coal mining

regions, the implication being that they

would not be reliable. Carr

remarked, "I would add that

ex-Governor Young had bad results

during the RR Riots in 1877 with

companies from large RR

centers."76 On the same

day, a group of New Lexington citizens

telegraphed Governor Hoadly, suggesting

that the New Lexington

company be excused from service because

many of its members were

coal miners, including its commanding

officer, Captain James

Teal.77 Governor Hoadly

disregarded these warnings and decided to

employ the New Lexington company.

In fact, an examination of the available

Ohio National Guard

rosters for the years before or during

the strike shows that the New

Lexington company was actually the only

company out of the eight

that saw service in the valley that had

any miners at all. Even the

roster of the New Lexington company

listed only four miners, be-

sides Captain Teal.78 Eight other men

were listed as "laborers," a

title that could possibly include men

who worked at mines. Since the

company reported a strength of

thirty-three officers and men on

September 1, this would mean that miners

and mine workers could

have comprised, at most, 40 percent of

the company.79 Thus the fears

seem groundless. However, for some

unknown reason Governor

Hoadly was anxious to remove the New

Lexington company from

service as soon as possible. Despite its

excellent performance, the

company was relieved several days before

the withdrawal of any

other troops from the initial

contingent. Whether the governor

selected the New Lexington company for

early withdrawal because

of pressure from operators concerned

with its composition, or merely

by random choice in his urge to bring

the troops home as soon as

possible, is not known.80

76. George Carr to Governor Hoadly,

September 1, 1884, Hoadly Papers.

77. John W. Free, JF. McMahon, [?]

Thacker, [?] Hoffman to Governor Hoadly,

September 1, 1884, Records of AG.

78. Ohio. Records of the Ohio Adjutant

General's Office. Roster, 17th Ohio Nation-

al Guard Regiment, 1870-1904, Vol. 162,

Ohio Historical Society.

79. Morning Report, Company A,

Seventeenth Regiment, September 1, 1884. Re-

cords of AG.

80. Colonel Dill to Governor Hoadly,

September 4, 5, and 6, 1884, AG Report,

56 OHIO HISTORY

Perhaps the most difficult aspect of the

Guard's intervention was

the decision concerning its withdrawal.

The longer the troops re-

mained, the greater their financial cost

to the state. On the other

hand, a premature withdrawal might lead

to renewed violence and

the necessity of once again committing

troops, with the risk of yet

another confrontation and perhaps even

greater expense. By the

time the Guard departed in early

October, the occupation had

already cost the state $14,575.78.81 In

addition, the Guardsmen, who

traditionally never enjoyed strike duty,

wearied quickly of service

and lamented lost wages they would have

earned on their civilian

jobs. Many of them began to petition for

relief after about two weeks

service. Since the Guardsmen received

full pay only during the first

seven days of service, after which they

received only half pay, they

naturally desired to return home to job

and families as soon as

possible.82 According to the Ohio

State Journal, the state, on the

other hand, preferred to maintain

individual units in the valley as

long as possible rather than rotate them

more frequently; because

fresh units would have to be given full

pay for their first seven days

of service, it was less expensive for

the state to retain an already

emplaced unit on service for more than

seven days.

Whether to remove the troops was not an

easy choice. The valley

was quiet and union officials promised

that it would remain so.

Military and police officials, on the

other hand, believed that vio-

lence might occur anew after the removal

of the militia, and the

events of the following months verified

their judgment. But as

General Finley had queried, how long

could the Guard remain in

the peaceful area? By mid-September,

newspapers of both political

parties were beginning to report the

cost the state had to bear in

order to keep idle soldiers in the

Hocking Valley.

Governor Hoadly, who had repeatedly

informed civilians and sol-

diers alike of his desire to make the

Guard's intervention as brief as

possible, decided to pull out the Guard

gradually in late September

and early October. This was probably the

wisest decision. The vio-

lence and destruction of property that

occurred from October 1884

through January 1885 was sporadic and

largely at a level that could

be controlled by local officials.

Considering the desperation of the

miners and their hostility towards the

operators, as well as the large

276-77; See also Hoadly to Dill,

September 3, 1884, Records of AG.

81. Ohio, Adjutant General's Report, 1885,

(Columbus, 1886), 55.

82. Colonel John C. Entreken to General

Ebenezer Finley, October 1, 1884, Re-

cords of AG.

Hocking Valley Coal Strike 57

number of potential targets, only a

long military occupation could

have prevented such attacks, an option

neither politically nor

economically feasible.

The proper function of the National

Guard in strike situations is

to restore peace, order, and civil

authority. Under the leadership of

Governor Hoadly, the Ohio National

Guard accomplished this quite

effectively. The Guard's intervention

resulted in the immediate res-

toration of peace and order and

succeeded in keeping violence and

property damage to a minimum. After an

uncertain start, Governor

Hoadly managed the Guard efficiently;

under his direction, its in-

volvement was brief and its

peacekeeping efforts moderate. Unlike

many publicized instances in which

civil authorities blatantly used

state forces to crush strikes, Ohio's

Governor Hoadly did an admir-

able job of utilizing the Ohio National

Guard in an impartial man-

ner in the Hocking Valley strike of

1884.