Ohio History Journal

|

|

|

(90) |

FLINT RIDGE.

BY WILLIAM C. MILLS.

INTRODUCTORY NOTE:

The explorations and studies recorded

in this paper

on Flint Ridge were undertaken for the

purpose of se-

curing for exhibition in the State

Museum a complete

collection of the various kinds of

flint found at Flint

Ridge as well as the implements used in

quarrying the

flint from its natural bed. A

preliminary examination

of Flint Ridge beginning at its western

edge in Hopewell

Township, Licking County, Ohio, extending

eastward

and ending in western Muskingum County,

a distance of

practically eight miles, made it

apparent that a more

extended and systematic study of the

quarrying, manu-

facture, and distribution of flint

objects was necessary

to enable one to cope with the many

complex problems

arising from a study of the art of

shaping the raw

material into artificial forms to meet

the varied needs of

a primitive people.

As the search for specimens of flint

and the imple-

ments used in quarrying progressed, it

was found neces-

sary to examine a number of so-called

pits, in search

of the evidence of quarrying flint and

to find the flint in

its original bed, partly quarried, and

this proved a very

difficult task in the region of the

suitable flint for making

knives, arrow, and spear points, for

this flint had prac-

tically all been removed from its

original bed, carried to

workshops and made into suitable forms

convenient for

transportation.

(91)

92

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

The examination soon developed the fact

that prim-

itive man may have developed quarrymen

who devoted

their time exclusively to producing the

raw material and

turning over such material to a second

industry, that of

roughing-out the blank forms. This,

however, may

have been accomplished by the same

individual but at

different times and places.

The third process comprised the art of

trimming,

making into special forms and finishing

blades or cores

ready for transportation.

Therefore, it seems that the three well

defined steps

would give rise to three separate

industries carried on

by the same individuals at different

times or places or

by different groups of experts trained

in their respec-

tive industry. The Flint Ridge quarries

for the most

part show that the first and second

steps were accom-

plished mainly at the quarries, because

primitive man

found it uneconomical to transport blocks

of material

of which nine-tenths would be thrown

away as useless;

and further, the promising blocked-out

piece might de-

velop seams or geodes of crystals that

would destroy its

usefulness in making the desired

implement. The work-

shop developed many such specimens,

showing the ad-

visability of working out the form of

the article to be

shaped in such a manner as to test the

material and its

capacity for specialization before

leaving the source of

supply. In other words, Flint Ridge

became a great

factory site, in which two principal

commodities were

manufactured and made ready to

transport by man-

power over the entire state of Ohio and

into other states

where the raw material was lacking. The

two commodi-

ties mentioned were the flint blades,

ranging in size from

Flint Ridge. 93

the small arrowhead to the blades for

making into

spears, and the flint core, from which

the flint knife was

made. The flint used for these purposes

was found in

the region of the cross-roads directly

north of Browns-

ville. The workshops in close proximity

to the quarries

contained many rejects, showing that

even with expert

selection many of the pieces were not

adapted for

making the desired flint knife with a

long, keen cutting

edge, so highly prized by primitive man.

As the examination of the quarries and

the region

surrounding them progressed, many

problems arose con-

cerning the probable prehistory Indians

who did the

extensive quarrying. All the

surrounding workshop

sites were examined but no implements

other than those

used in shaping the blades were found.

However, at the

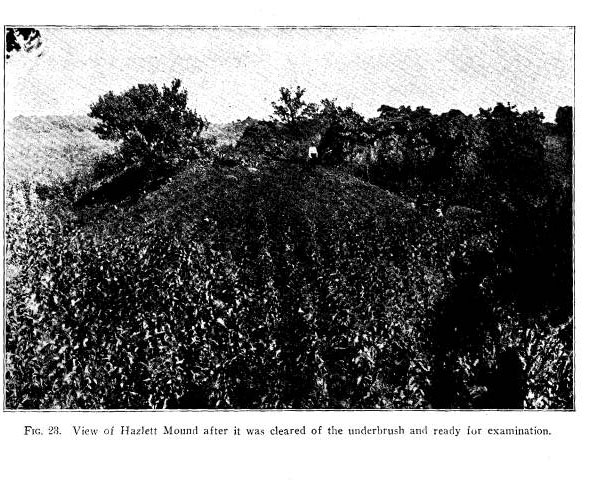

west end of the ridge was located a

large mound sur-

rounded by a circle made of blocks of

flint and earth.

This mound was examined and the culture

determined

to be the Hopewell, the highest in

point of advanced

prehistory civilization in Ohio,

showing that this culture

had established themselves at the site

of this wonderful

supply of the most desirable raw

material used in the

manufacture of artificial forms to meet

the varied needs

of the primitive inhabitants. A

detailed account of the

examination of this mound will be found

in the pages

following the account of the

examination of the quarry

sites.

I am greatly indebted to many

individuals for their

assistance in the examination of Flint

Ridge and espe-

cially to Mr. H. C. Shetrone, assistant

curator, who

carried forward the work on occasions

when other

duties connected with the Museum

compelled me to be

94 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

absent; to Dr. Clark Wissler of the

American Museum

of Natural History, New York, who spent

a short time

in July, 1918, and again in August,

1919, for his help

and counsel; to Professor J. Arthur

MacLean of the

Cleveland Museum of Art, for his

assistance in the ex-

ploration of the mound located at the

west end of the

"Ridge;" to Mr. Jay Clark, a

resident of the "Ridge"

for more than forty years, for help and

information

given and specimens presented to the

museum. To the

many residents of the "Ridge"

I wish to extend my

thanks for assistance in the laborious

excavations made

in various sections and for specimens

presented to the

museum.

THE FIELD OF INVESTIGATION.

Flint Ridge is a very irregular

plateau-capped line of rugged

hills, located in Licking and Muskingum

counties, about midway

between Newark, the county seat of

Licking, and Zanesville, the

county seat of Muskingum. The region is a part of the great

Allegheny Plateau which has an elevation

of approximately

1,200 feet at the western end of the ridge in Licking,

gradually

decreasing eastward, probably due to the

greater eroding agen-

cies.

The Licking River, located about five miles north of

Flint Ridge, runs approximately east and

parallel with Flint

Ridge and empties into the Muskingum

River. The small rib-

bon-like valley plains, with small

streams fed by springs from

the "Ridge", would furnish no

means of water transportation to

and from the source of supply;

consequently the only way to

reach the "Ridge" was by

trails through the deep tangled forest,

leading to the great manufacturing

industrial center of the pre-

historic Indian, in the region of

Clark's blacksmith-shop, located

at the road-crossing three miles

directly north of Brownsville.

It is striking to observe that the

varied phenomena studied are

assembled within a radius of one mile of

this place, and at the

extreme eastern end of the

"Ridge". The flint occurring outside

of these two places was of no practical

use to primitive man, be-

|

(95) |

96 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

cause of its unfitness for chipping into

form on account of im-

purities.

In the region of the cross-roads the

best examples of flint

may be found, as well as the largest

quarries located on the

"Ridge".

An examination of the quarries developed

the fact that

only a very small portion of the flint

deposit was of use to pre-

historic man in the manufacture of

artifacts, as much of the

flint was full of seams and cracks which

did not permit of the

manufacture of a desired artifact with

any degree of certainty,

as demonstrated by the many broken

blades found on the site

of the work shop.

Another feature of the flint in this

section was the presence

of countless geodes filled with quartz

crystals. The geodes

varied in size from that of a pea or

less to large geodes of from

twelve to fourteen inches in

diameter. The quartz crystals

found in the geodes were usually small,

but the large geodes

generally contained large crystals.

Apparently the crystals, un-

less very large, were not used in any

way and were thrown away

with the useless flint.

The flint found outside of the regions

where it was quarried

is very porous and fossiliferous, and

very frequently mixed with

calcareous or argillaceous material,

which rendered it useless

to primitive man as far as chipped

implements were concerned.

The flint at the west end of the

"Ridge", in Licking County,

was especially useless to primitive man,

but the early white

settler found it well adapted to the

making of buhr-stones, used

in grinding grain into flour. Near the western edge of the

outcrop of the flint, several partly

formed buhr-stones, each

weighing a ton or more, may be seen

where they were quarried,

upon the farm of Mr. William Hazlett,

near the only large

mound located upon the

"Ridge".

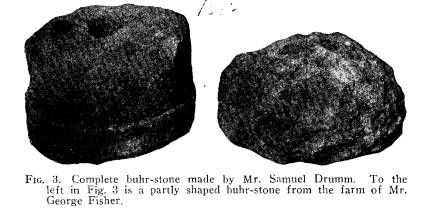

The flint at the eastern end of the

"Ridge" is likewise unfit

for implement making but well adapted

for buhr-stones. In the

early pioneer days of Ohio, Mr. Samuel

Drumm quarried the

flint in suitable blocks and fashioned

them into small hand buhr-

stones.

One of the buhr-stones complete and one partly shaped

|

Vol. XXX-7 (97) |

|

98 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications. and found at the quarry where many more were in evidence are shown in Fig. 3. The farm upon which the quarry is located is owned by Mr. George Fisher, who kindly presented to the museum a fine sample of the partly shaped buhr-stone shown to the right in Fig. 3 as well as a buhr-stone sent from France and used as a sample stone. The manufacture of these small buhr-stones during the early settlement of the country was a very great convenience to the people, as water mills for grinding grain could only be con- structed where proper conditions prevailed, and often long dis- |

|

|

|

tances would be traveled to find such a mill; consequently the small hand mill made from Flint Ridge flint was very desirable, and the manufacture of the buhr-stones proved to be a very lucrative industry. The buhr-stones manufactured at the Drumm site were sent to a point on the Old National Road, three miles to the south, where they were transported by ox teams as far west as the Mississippi River and as far east as Pittsburgh. The preliminary examination of numerous quarries upon Flint Ridge made it apparent that the solution of the problem of quarrying the flint was unsolved and, to arrive at any definite conclusions, a systematic study of the entire area was necessary. |

Flint Ridge. 99

Consequently the field of investigation

was extended to every

part of the ridge where primitive man

attempted to quarry and

make use of the flint.

GEOLOGY OF FLINT RIDGE.

As a preliminary step to a study of the

evidence of human

industry on Flint Ridge, it is very

important that the geology

of the place be reviewed. Aboriginal flint quarries have long

been known at Flint Ridge, but prior to

1830 little was known

to the scientist concerning the geology

of this region. The first

writer referring to the aboriginal

quarries was Caleb Atwater in

his "Western Antiquities",

page 28, as follows:

"A few miles below Newark, on the

south side of the Lick-

ing, are some of the most extraordinary

holes, dug in the earth,

for number and depth, of any within my

knowledge, which be-

longed to the people we are treating

of. In popular language,

they are called 'wells' but were not dug

for the purpose of

procuring water, either fresh or salt.

"There are at least a thousand of

these 'wells'; many of

them are now more than twenty feet in

depth. A great deal

of curiosity has been excited, as to the

objects sought for by

the people who dug these holes. One

gentlemen nearly ruined

himself by digging in and about these

works, in quest of the

precious metals; but he found nothing

very precious. I have

been at the pains to obtain specimens of

all the minerals, in and

near these wells. They have not all of

them been put to proper

tests; but I can say, that rock

crystals, some of them very beauti-

ful, and horn stone, suitable for arrow

and spear heads, and a

little lead, sulphur, and iron, was all

that I could ascertain cor-

rectly to belong to the specimens in my

possession. Rock crys-

tals, and stone arrow and spear heads,

were in great repute

among them, if we are to judge from the

numbers of them

found in such of the mounds as were

common cemeteries. To

a rude people, nothing would stand a

better chance of being

esteemed, as an ornament, than such

articles.

"On the whole, I am of the opinion,

that these holes were

dug for the purpose of procuring the

articles above named;

and that it is highly probable a vast

population, once here, pro-

cured these, in their estimation, highly

ornamental and useful

articles. And it is possible that they

might have procured some

lead here, though by no means probable,

because we no where

find any lead which ever belonged to

them, and it will not very

soon, like iron, become an oxide, by

rusting."

100

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

In 1836 the first geological survey of

Ohio was published,

in which Dr. Hildreth calls attention to

the flint quarries in Ohio

and comments on their great extent,

beginning in Jackson County

and extending north to Muskingum County,

and calls the flint a

calcareo-silicious formation.

Mr. J. S. Newberry, Chief Geologist of

the Ohio Geological

Survey, in discussing the carboniferous

system in Ohio com-

ments at some length concerning the

famous Flint Ridge:*

"The origin of the silex in these

flinty limestones has never

been satisfactorily explained. It has

sometimes been attributed

to hot springs, of which the water contained much

silica, but

the general distribution of the flint

and the immense number of

fossils sometimes contained in it,

seemed to me insurmountable

objections to this view. It appears to me more probable that

the silica was derived from microscopic

organisms, such as the

diatoms. It is well known that at the present time very exten-

sive deposits of silicious earth

('infusorial earth') are being made

in our lakes and lagoons. These are frequently associated with

shell marl and sometimes bog iron

ore. In the Tertiary age,

even more extensive beds of diatomaceous

silica were formed

than any belonging to the present age

yet discovered, the polish-

ing slate of Bilin, ('tripoli'),

Monterey, and Nevada 'infusorial

earths,' etc. In the older formations no

such strata are found,

and yet it is hardly probable that the

low forms of life from

which these beds of silica are derived

are of modern date. From

some experiments recently made by Mr.

Henry Newton at my

request, we learn that the silicious

shields of diatoms are more

soluble than almost any other form of

silica known, and it seems

to me quite possible that in the older

diatomaceous earths the

individual forms have disappeared by

solution, and the mass

has been converted into compact

amorphous silica, such as we

find in our beds of chert. I would, therefore, suggest that in

many parts of the lagoons which, from

time to time, occupied

the coal area, the shields of diatoms

accumulated in beds

of considerable thickness, and these,

now blended and consoli-

dated by solution, form our Coal Measure

buhr-stones.

"In this view, the wide diffusion

of the silica and its blend-

ing with and shading into purer

limestone as though deposited

in the quieter nooks of the broad

lagoon, its association with

fossils and iron, are all harmonious and

confirmatory facts. If

hot springs had furnished the silica, we

should be pretty certain

*Geological Survey of Ohio, Vol. 2, page

142-143.

Flint Ridge. 101

to find it impregnating other strata

than the limestone, and

should probably find some masses or

accumulations heaped up

about the source of supply, but we have

discovered nothing of

the kind; and the careful observation of the facts in

the case

has convinced me that the silica, like

the lime, is indigenous and

not exotic, that is, that it accumulated

particle by particle as a

sediment at the bottom of water where it

was slowly drawn

from solution and fixed by some vital

agency."

In 1878, Mr. M. C. Read, Special

Assistant of the Geo-

logical Survey of Ohio, wrote the

Geology of Licking County,

(Geological Survey of Ohio, Vol. 3,) and

I quote from his re-

port as follows:

"The number of this series found on

the summit of most

of the hills in the south-east part of

the county is the flint, which

is ordinarily regarded as on the horizon

of Coal No. 6, the Great

Vein of Perry and Hocking counties, this

coal being represented

by the thin and worthless seam

underlying the flint. I am dis-

posed, however, to regard the flint as

the equivalent of the

'Black Marble,' so-called, of Coshocton

county-which has be-

neath it a thin seam of coal, and is

found in places only ten or

twelve feet below Coal No. 6-and the

representative of the

drab limestone of Columbiana county,

often found directly be-

neath No. 6. In Coshocton county this 'Black Marble' often

passes into a chert, as do all the

limestones of that county, but

none of them form so extensive and

continuous deposits as the

flint of Flint Ridge. Any one traversing this ridge for the

first time would be surprised to find

such a deposit on such a

geological horizon. It simulates very

accurately the broken-up

debris of a vertical dike, the fragments

often covered with per-

fect crystals of quartz, the rock itself

being highly crystalline

and often translucent. It is something of a puzzle to under-

stand how such a deposit is found in a

series of undisturbed

and unmodified sedimentary rocks. The adjacent surfaces of

two blocks of the chert are often found

covered with quartz

crystals of considerable size, as

thoroughly interlocking with

each other as if one were a cast, and

the other the matrix. I

cannot imagine conditions which would

spread such a deposit

over the floor of a sea or any other

body of water. A substitu-

tion of silicious matter deposited from

solution, in the place of

a soluble limestone previously

deposited, is the only plausible

explanation. This substitution has taken place over large areas

in this part of the State, and has left

these silicious deposits

only upon the horizons of the different

limestones."

102

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

Mr. Read inserts as a foot-note the

following:

"The question of the origin of the

silica, which so often

replaces the carbonate of lime in the

Coal Measure limestones,

is discussed at some length in Vol. 2 of

this report, and it is

there attributed to DIATOMS. These microscopic plants, as is

well known, bear silicious frustules,

which accumulate at the

bottom of some lakes and ponds till they

form beds many miles

in extent and several feet in thickness.

They probably inhabited

portions of the shallow land-locked

basins where the limestones

were formed in such numbers as to supply

silica for concretions

or cherty layers, and sometimes to

replace the calcareous bed

entirely, just as we find the

diatomaceous earths locally replacing

shell-marl in the bottoms of our lakes

and marshes. The silica

which forms the frustules of the diatoms

has been proved by

experiment to be unusually soluble, and

in the flint beds, the in-

dividual forms have doubtless been

either so completely dissolved

or so enveloped in soluble silica as to

be lost. The quartz crys-

tals referred to by Mr. Read as coating

the blocks and filling

the crevices and cavities of the flint,

are evidently of modern

origin, and have been formed by a

deposit of silica, from solu-

tion, in whatever receptacles were open

to it."

Mr. Wilbur Stout in his Geology of

Muskingum County,

(Bulletin No. 21, Geological Survey of Ohio), assigns the Flint

Ridge flint to the horizon of the

ferriferous limestone. I quote

from Mr. Stout's report at length, as he

covers the geological

phenomena of Flint Ridge:

"In ascending order the important

rock stratum above the

Clarion coal is the Ferriferous or

Vanport limestone, which is

also often called Gray limestone owing to its color.

This mem-

ber is not persistent and is variable in character in

the western

part of Muskingum County where the bed

is above cover. How-

ever, the scattered deposits of this

member may be followed

with some certainty from Perry County on

the south into Coshoc-

ton County on the north. From Perry

County it may be traced

southward to the large and important

field in Vinton, Jackson,

Gallia, Scioto, and Lawrence counties,

where it has characteristic

development and excellent continuity.

Owing to many wants in

deposition and to rapid changes in

character the bed is followed

with more difficulty from Coshocton

County northeastward to

Mahoning and Columbiana counties where

it again has good

volume, and from where it has been directly traced into

Law-

rence and Beaver counties, Pennsylvania.

Flint Ridge. 103

"Two well-defined phases of the

Ferriferous member are

present in Muskingum County. In most of

the county the up-

per phase is a bed of rather pure flint

or limestone, in many

places several feet in thickness. The

flint is best represented by

the massive stratum that extends along

Flint Ridge from Poverty

Run in Hopewell Township, Muskingum

County, to the Porter

School in Franklin Township, Licking

County. Dr. Orton as-

signed this rock to the horizon of the

Ferriferous limestone.*

"Miss Clara Gould Mark also assigns

the flint to this horizon.

In 1916-17 the members of this Survey traced the stratum by

stringers of flint and impure limestone

to Bairds Furnace, Hock-

ing County, where the member is a true

limestone, definitely

known to be correlative with the more

massive and persistent

Ferriferous beds of southern Ohio. Further, in its extension

northward from Flint Ridge, Muskingum

County, the stratum

undergoes many changes, as it may be

represented by thin local

beds of flint, or by flint and

limestone, or by limestone alone.

Along the ridge known as the Highlands,

in Cass Township,

the horizon is marked locally by a thick

bed of gray limestone

very similar to that present in southern

Ohio. North of this,

along Graham Ridge, in Coshocton County,

thin beds of flint

again appear, and near Warsaw local

deposits of impure lime-

stone were observed. Similar conditions were noted in parts

of Tuscarawas County. Although local, variable, and scat-

tered, the deposits of this flinty phase

in Muskingum County

are sufficiently pronounced to be

followed with certainty, and

in the opinion of the writer they are

correlative with the Fer-

riferous limestone of eastern and

southern Ohio."

"The flint beds of the Ferriferous

member in Hopewell

and Franklin townships of Licking County

are the largest in

Ohio, and were extensively worked by the

aborigines, who dug

hundreds of pits along Flint Ridge in

the mining of this ma-

terial. The stratum was evidently worked

for a long period,

and the material, identified by its

characteristic fossils, is widely

distributed. Much of the flint chipped into arrows, knives,

scrapers, etc., and found in the burial

mounds and earthworks

of the mound builders, as well as that

similarly worked and

found on the surface in this and

adjoining states, is from Flint

Ridge. The field is of exceptional

interest both to the geologist

and archaeologist. The outcrop

measurements indicate that the

light-colored bed of flint is from 1 to

10 feet in thickness, and

that it averages about 5 or 6 feet. This stratum is directly

bedded on the shaly limestone, the

thickness of which, from sur-

face indications, is from 5 to 20 feet,

or even more. Owing to

*Geol. Survey Ohio, Vol. V. p. 870.

104 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society

Publications.

the

slumping of the flint and to the nature of the covering no

good sections

of the entire interval were obtained.

"Along

the ridge at the head of Berry Run, in Hopewell

Township, the

light flint is massive, and varies from 3 to 10 feet

in

thickness. The bed was mined by the

aborigines more ex-

tensively

in this locality than on either the western or eastern

part

of the ridge. A section taken in a

ravine east of the cross-

roads

follows:

Ft. In.

Flint, light

....................... ..... 5

Limestone,

thin to medium bedded. shaly. Ferriferous 7

Covered ................................... 32

Sandstone, parts

covered

................................. 32

S h

ale

.................................................... 1

Sandstone

........................ 23

Shale,

calcareous, with shaly limestone.

1

Limestone,

dark siliceous .............. .. 8

Shales,

calcareous, with shaly limestone. 5

Limestone,

hard ......................... Lower Mercer 3 6

S

hale

................................... 2

Limestone,

hard ........................ 1 8

"In

this locality the light-colored flint or upper phase of the

Ferriferous

member is bedded on the shaly limestone or lower

phase. No separation, except an irregular bedding

plane, is

evident,

thus suggesting that both rocks were laid down during

the

same general deposition period. In

the above section the

interval

between the Ferriferous member and the Lower Mercer

limestone

is about normal for the region."

ECONOMIC

VALUE OF THE FERRIFEROUS LIMESTONE AND FLINT.

"The

great value to the aborigines of the flint beds of the

Ferriferous

member in Muskingum County, and also in Licking

County,

is attested by the large quantities of earth and rocks

mined

in the excavation of the hundreds of pits scattered along

Flint

Ridge and along its spurs. This Flint was certainly held

in

high esteem by these ancient people, who used it in the manu-

facture

of implements for domestic purposes, for hunting, and

for

war. Arrows, knives, skinners,

scrapers, hoes, and drills

made

of flint from this locality, and recognized by the remains,

are

scattered over a wide area in the Ohio Valley and in the

Lake

Erie region. Their method of quarrying

the flint and of

shaping

the implements is a subject of interest, but it belongs

more

to the province of archaeology than to that of present-day

geology

and hence needs no further discussion here."

Flint

Ridge. 105

CHEMICAL

ANALYSIS OF THE FLINT.

"The

chemical as well as the physical properties of the

light-colored

flint on Flint Ridge are such that the material may

be

utilized for the manufacture of silica brick or for potter's

flint

of white ware bodies. The deposit along

the main ridge

for a

distance of more than 5 miles was sampled by taking pieces

thrown out of

the pits excavated by the aborigines. This sample

weighing

more than 100 pounds was properly crushed and pre-

pared

for analysis. The chemical work was done by Prof. D.

J. Demorest,

who reports the following results:

Silicia,

SiO2 ............................... 96.40

Alumina,A ....................................... 1.52

Ferric oxide, FeO

................................... .48

Lim e, CaO

........................................... .30

Magnesia,

MgO .......................................04

W

ater, comb., H20................................... 1.20

99.94

CHARACTER

AND ORIGIN OF THE FLINT.

I have

given the view of Newberry as to the origin of the

flint

at Flint Ridge, which he attributes to diatomaceous plants,

a view

acquiesced in by Mr. Read, who wrote the Geology of

Licking

County, 1878. Mr. Stout gives three

views as to the

possible

origin of the flint at Flint Ridge, and I quote from his

report:

"The

flint in the black layers is very solid and dense except

for

small cavities, which are irregularly spaced and frequently

lined

with transparent quartz crystals. The

gray flint is also

solid,

and has a banded and somewhat mottled appearance, prob-

ably

due to original deposition, and the analysis shows it to be

anhydrous

or nearly so. The coal formation flints

seldom con-

tain

more than 2 per cent of water. Flint has a

hardness com-

parable

with that of quartz, and it breaks with a deep conchoidal

fracture,

the perfection of which depends on the texture of the

material. This characteristic fracture is much more

evident in

the

compact, vitreous varieties than in the more porous, grainy

types

which are mixtures of amorphous silica and quartz sand

or

calcareous or argillaceous material. It

varies from nearly

transparent

to coal-black, and from the strikingly mottled or

banded

types to those traversed by small veins of different

colored

material of later formation.

"Three

views are tenable as to the origin of the flints as-

sociated

with the limestones or stratified on the horizons of

these

rocks:

106 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society

Publications.

"(a) That the flint was formed by direct

precipitation of

the siliceous matter by

silica-secreting organisms.

"(b) That the flint was the resultant of chemical

action

of soluble silica and

other components in the sea water upon

the calcium carbonate

of newly formed limestone. In this case

the change took place

while the limestone was forming or while

it was yet under the

direct influence of the salt brines.

"(c) That circulating

ground waters, charged with sili-

ceous and organic

components which acted upon limestone de-

posited under normal

conditions and buried by later sediments,

slowly removed the

calcium carbonate and deposited silica in its

place. This action began as soon as the beds were

covered by

other material and is

still effective. Under this condition

the

flint is entirely of

secondary origin.

"In regard to the

first view, it is necessary to account for

large quantities of

soluble silica and a means of precipitating it.

The flint beds found

in the coal formations of Muskingum

County are directly

associated with limestones, or more often

occur on the horizons

of these rocks. Judging from fossil and

other evidence, these

limestones are of organic origin and were

laid down in shallow

basins of the sea. The natural

inference

is, therefore, that

the flint has a similar derivation.

Some of

the low forms of life,

such as radiolaria, sponges, and diatoms,

which inhabit both

fresh and salt water, secrete silica.

Such

material secreted by

an organism is hydrous and glassy and is

readily dissolved by

waters containing carbonates of the alkalis

or alkaline

earths. Carbon dioxide from a living or

a decaying

organism, however,

readily precipitates this silica. It is

also

thrown down by

hydrolysis in the presence of weak acids such

as may occur from

decaying organic matter. The rocks on

these flint horizons

show that a profusion of life existed in

these early seas, a

part of which was evidently silica-secreting,

and the presence, or

rather decay, of which would produce con-

ditions often

favorable for the direct deposition of silica.

"Some of the

flint deposits in the coal formations of Mus-

kingum, Perry, and

Coshocton counties suggest such an origin.

The material is very

free from calcium and magnesium carbon-

ates, has the mottling

characteristic of gelatinous precipitates,

and shows no distinct

nuclei attending concretionary growths.

Further, the relation

of flint beds to limestone strata in some

localities is also of

interest. As noted in some of the preceding

sections, a flint

layer may lie either directly above or directly

below a limestone

which is very free from flinty material. Later-

ally the rocks often

pass in a regular way from limestone or from

sandstone to flint in

about the same way as shale to sandstone

Flint Ridge. 107

or carbonaceous shale

to coal. Flint deposits are also nearly

as abundant in the Pottsville

and Allegheny formations of this

area as limestone

deposits. With varying conditions in

these

shallow seas where

both siliceous and calcareous matter are be-

ing secreted, flint

should result as one extreme and limestone as

the other.

"The second view

is closely related to the first, but it differs

in that soluble

silica replaces the calcium carbonate of newly

formed

sediments. As shown by several writers,

the replace-

ment of the calcium

carbonate of shells, corals, etc., by silica is

easily effected. The

most favorable conditions would be where

both silica and

calcium carbonate are being secreted contempo-

raneously by organic

life. Such silica is very soluble and

the

calcium carbonate is

in a state which can be readily attacked,

thus making

replacement easy. The

alkalinity and pressure of

the water also aid in

this work. The waters of

these ancient

seas contained a

profusion of both plant and animal life, secret-

ing either silica or

calcium carbonate; they were warm, owing to

the shallow depth and

to the prevailing climate, and were par-

tially saturated with

mineral and organic components which aid

in chemical action,

all of which conditions favored replacement

changes attending

deposition.

"Such an origin

appears plausible for some of the flint

strata in the coal

formations of this area. In a certain

bed,

as the Upper Mercer,

for instance, flint may be overlain by

limestone or

limestone by flint, or the two may occur in almost

any proportion. Substitutions are apparent, but it is

difficult

to determine whether

they took place during the early period of

formation or during a

later period by the action of circulating

waters. The deposits are intermediate stages between

a lime-

stone and a

flint. The limestones on these horizons

are every-

where fossiliferous

and, as would be expected, the flints con-

tain the same

fossils, although they are less abundant and less

delicatedly

preserved, with the possible exception of the FUSU-

LINA and other small

types. The state of the fossils indicates

alteration

changes. The flint in local areas has a

banded and

orbicular structure

which shows secondary arrangement of the

matter. Replacements in many of these beds are

evident, but

it is uncertain how

much is to be accredited to the early stages

of formation and how

much to the later.

"Taking the

third view next into consideration, the original

rock is a regularly

deposited limestone covered by later sedi-

ments. Circulating ground waters holding soluble

silica and

organic components in

solution attack the limestone, taking cal-

cium carbonate into

solution and depositing silica in its place.

108

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

The flints are thus of secondary

origin. The chemical action

involved is the same as it is in the

second case, except that it

is performed through the medium of

circulating ground waters

in place of salt brines. The change is

effected under less favor-

able conditions, but the force is

operative over a longer time in-

terval. The action began with the covering of the bed

by later

sediments and is still effective. The

question is whether the ac-

tion of ground waters is sufficient to

change thick beds of lime-

stone extending over wide areas to

strata of flint. On the

Boggs horizon the flint is from a few

inches to 1 foot 6 inches

thick, and is rather local; on the Upper

Mercer horizon the

volume varies from 1 foot to more than

10 feet, and it is very

persistent over a wide area, and on the

Ferriferous horizon it

varies from a few inches to 10 feet, and

is often continuous

for several miles. The variation in the

character of these mem-

bers is shown under the discussion of

their stratigraphy.

"The work of ground waters in

effecting the solution of

one component and the substitution of

another is well known,

and this action accounts for the nodules

of flint in many of the

massive limestone and chalk beds. It is a question, however, as

to whether this accounts for the origin

of the thick beds of

flint in the coal formations of this

area. Where the section was

measured on the Lee Moore farm in

Jefferson Township,

Coshocton County, the lower layer is

composed of irregular

masses of relatively pure flint and

limestone which are distinctly

separated, but with the flint

constituting the greater part. Re-

placement of calcium carbonate by silica

is strongly suggested.

Above this layer, there is 11 feet of

thin to medium-bedded shaly

limestone containing practically no

flint, and directly overlying

this shaly limestone there are two

layers of flint which are only

slightly calcareous at most, and which

contain no large irregular

masses of limestone. If these two beds were originally lime-

stone the transformation from limestone

to flint has been quite

complete. The series thus shows

limestone beds lying between

flint strata. If these flint beds were formed through the action

of circulating waters on limestone,

subsequent to the formation

of the entire deposit, then the

limestones occupying the middle of

the deposit should also show evidence of

the same influence,

which is not the case. The structure of

the deposit, therefore,

seems to show that these rocks were laid

down in about the same

condition as that in which they are now

found."

MEANS OF IDENTIFICATION OF FLINT.

Flint objects found upon the surface of

practically every

portion of Ohio are very often difficult

to identify as to source.

Flint Ridge. 109

The flint from Flint Ridge varies

greatly in different parts of

the deposit, but in the region of the

pits the flint is very com-

pact, almost free from impurities, and

possesses all the colors

and shades found in flint. Much of the

flint is blue or a grayish-

blue translucent chalcedony. In some places a glassy variety

is found in connection with the

grayish-blue variety and ranges

from almost perfect transparency to

complete opacity. In an-

other section jasper predominates, with

a wide range of color

from dark red through the various shades

of yellow; also a

banded, or ribbon variety, with

alternating stripes of light and

dark gray, brown and black.

In the central part of the great pit

region southeast of

Clark's blacksmith-shop the flint has

practically all been removed

from its bed, and here is found the most

beautiful of the various

colored chalcedony showing the tints of

blue, red, green, purple,

brown, yellow and white.

A careful examination of specimens of

flint collected from

the various quarrying sites and the

workshops is a necessary aid

in identifying the flint after it has

been made into objects by

primitive man and carried to remote

places.

In 1898 the writer undertook a

microscopical study of the

flint from Flint Ridge with a view of

determining the original

home of flint specimens found upon the

surface in practically

every part of the state, as well as

specimens taken from mounds

and village sites. More than 100 thin sections were made and

studied. The specimens from which the thin sections were cut

were secured from pits where the flint

was quarried and from

the workshops nearby. Thin sections of

flint from other known

quarries in the United States and Europe

were made for com-

parison. The microscopic thin sections from the Flint Ridge

flint proved of special interest and

value as a means of identifica-

tion, as many forms of siliceous

foraminifera as well as siliceous

sponges were in evidence, which would

readily identify the Flint

Ridge flint.

Only a few of the microscopic thin

sections from Flint

Ridge show diatom fragments and a few

show nothing definite

in the way of fossils, but the general

appearance of the compact

110

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

crypto-crystalline mass of chalcedonic

silica as shown by the

microscope was a great aid in

determining the Flint Ridge flint

when compared with flint from other

sections.

QUARRYING

The primitive inhabitants of Ohio made

use of various kinds

of rocks found in the drift, where the

agents of nature-the

glacier and floods,- had with almost

human discrimination de-

posited the tough granites and

quartzites in convenient places

for man to select and reduce to

available size and form But

the flint, so highly prized for the

manufacture of arrow and

spear-heads, occurs only in well defined

areas, where the outcrop

was available and served as a guide to

the location of the great

deposit a few feet under the soil.

Quarrying the flint really begins with

the removal of a

fragment from the exposed mass or from

the ground where it

was partly buried. It is only a step further when the mass of

the flint is uncovered, and the flint

removed on a large scale.

EXTENT OF OPERATIONS.

The extent of quarry operations in the

region where the

valuable flint is found centers around

the Cross Roads, three

miles directly north of Brownsville and

known as Clark's Black-

smith Shop. A circle with a diameter of one mile with the

center at the cross-roads would enclose

about all the sections

quarried, and the extent of the quarried

area within this circle

would not exceed 100 acres. When we take into account that

practically all of the flint used by the

various cultures represent-

ing the prehistoric Indian in Ohio came

from the Flint Ridge

region, we can readily understand and

appreciate the importance

of territory quarried. All trails

leading in the direction of Flint

Ridge would end there, or in other

words, Flint Ridge was the

trailsend of the prehistoric Indian in

Ohio. The accompanying

map, Fig. 3A, indicates the general

distribution of the flint de-

posit as well as the location of the

quarries as indicated by

excavations over the entire area.

Flint Ridge. 111

THE FLINT STRATUM.

The flint stratum is very irregular in

thickness and at no

place examined did the flint exceed six

feet in thickness, al-

though other reports from various

sections give a thickness

varying from five to ten feet. Directly

north of the cross-roads

the stratum measures fully six feet,

while following the pitted

section due north to near the edge or

outcrop, the depth of the

flint measures only eighteen inches, and

the top and bottom of

the deposit become very irregular and

more or less nodular in

form.

The weathering out of small fossils and calcite crystals,

which appear in great abundance near the

margins, makes the

flint appear cellular or porous in

structure. This condition

prevails in the greater bulk of the

flint found on the ridge. Con-

sequently prehistoric man discovered

that the greater part of the

flint was of no value for the

manufacture of artifacts and ac-

cordingly concentrated his efforts upon

the material that would

best meet his requirements. This was limited to two sections;

namely, the region of the cross-roads,

three miles north of

Brownsville, Licking County, and the

region of the Flint Ridge

School, Hopewell Township, Muskingum

County. The terri-

tory quarried over in these two sections

would perhaps not ex-

ceed 100 acres in extent.

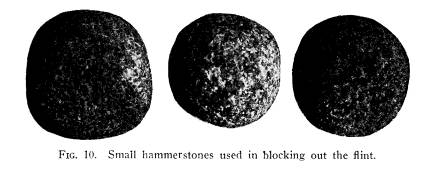

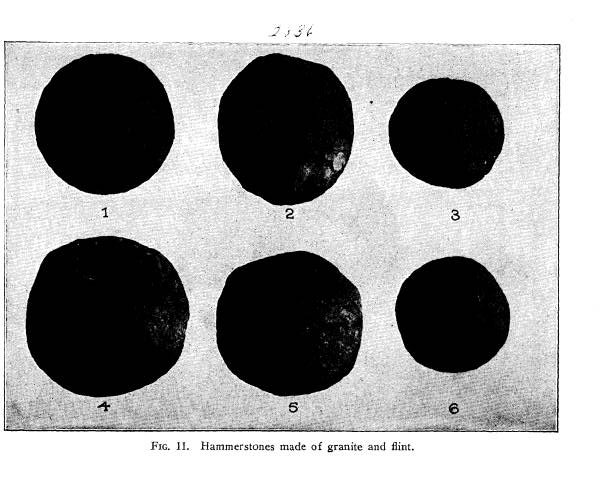

METHOD OF QUARRYING.

After our examination of many of the

quarries upon the

"Ridge" the most striking and

marvelous phenomenon is that

the aborigines ever accomplished the

removal of such a thick

stratum of flint over a so comparatively

large area. Only those

who have ventured to remove the flint

from its natural bed with

modern tools can appreciate the skill

and perseverance necessary

in wresting from nature the flint needed

in fashioning the many

artifacts, with such primitive

tools. These tools are found in

abundance over the entire site and in

many instances where the

ancient quarryman had left them.

Mr. Gerard Fowke, while in the employ of

the Bureau of

Ethnology, made a systematic study of

"Flint Ridge" and his

report appears in the annual report of

the Smithsonian Institu-

112

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

tion for 1884, and in his work entitled

the "Archaeological His-

tory of Ohio" published in 1902. Mr.

Fowke spent much time

in a personal examination of the entire

"Ridge" and his recorded

observations on the method of quarrying

the flint are of especial

interest and value. I quote from his report to the Bureau of

Ethnology, published in Smithsonian

Report, 1884, page 864:

"How these ancients knew where to

find the best flint for

their purposes, unless indeed these

sites were chosen at random,

cannot be told. It also remains a

question as to how the flint

was quarried after its location was

determined. No doubt a thor-

ough examination of some of these pits

will throw much light

upon the methods in use among them for

obtaining the raw

material."

Quoting further from the same report,

page 867:

"The aborigines (meaning thereby

Indians, Mound Builders,

or whatever other name may be assigned

to the people who did

this work) knew that by digging into the

unweathered bed-rock

a quality of flint could be obtained

better suited to their pur-

poses than that which could be procured

along the outcrop. The

dirt was cleared away, by being carried

out in baskets or skins,

until the flint was exposed. Cleaning

out a space sufficient for

working purposes, a fire was built on

top of the rock, and when

it was heated water was thrown on it.

This would cause the

rock to crumble, and on clearing out the

fragments a fresh sur-

face of flint would be exposed around

the hole thus made in it,

from which pieces could be broken-off

with the large boulders

found in the vicinity. A question presents itself here, 'If this

method was used, why did they not follow

the flint stratum, once

they had found it, throwing the dirt

behind them, instead of open-

ing so many fresh holes?' The only

answer to be given is that

they did not, except in a few instances,

and that is all we know

about it."

Later, Mr. Fowke in his book

"Archaeological History of

Ohio", page 622, goes into detail

concerning the quarrying of

the flint by the use of fire:

"The pit taken as an illustration

was at least forty yards

from the one nearest to it; it was

thirty-two feet in diameter

inside of the wall of earth surrounding

it, which wall is now

two feet higher than the general surface

around it, and from

twenty to thirty feet across at the

base. This form indicates

Flint Ridge. 113

considerable age; as does an oak tree

nearly ten feet in circum-

ference, growing on the top of the wall.

In clearing out this

pit we could appreciate the patience and industry of

the abo-

riginal excavators. The clay subsoil was as hard and

tough as

frozen ground; frequently half a dozen

blows with a pick were

required to break off a clod as large as

a man's hand. To re-

move it with primitive tools seems almost an

impossibility. The

central part of the pit was filled with

material that had washed

in from the sides. Several days of steady digging were re-

quired, by three men accustomed to such

work, to reach the

surface of the flint stratum, which was

found at a depth of

nine feet. A hole five by eight and one-half feet had been

worked through; clearing this out, we

found the layer to be forty

inches thick. It rested directly upon a solid bluish limestone.

Both the flint and the limestone showed

that they had been

subjected to an intense heat. The flint was very solid where

not burnt, translucent, and a beautiful

light-blue in color. On

its top, on a corner formed by two

seams, was a saucer-shaped

depression between three and four inches

deep, in the bottom

of which was a handful of very fine

chips; just such as would

result from repeated blows with a large

hammer-stone, several

of which were found scattered through

the entire depth cleared

out.

One of them weighed nearly or quite a hundred pounds.

"Careful observation of this

pit-and others as well-

enables us to follow the prehistoric

quarryman in his labors.

He selected a spot where he thought the

superincumbent earth

not heavy enough to render the task of

removing it too tedious,

but at the same time was of ample

thickness to prevent injury

to the stone from weathering. He then sunk a pit, as

large as

he wished, to the surface of the flint.

On this he made a fire;

and when the stone was hot he threw

water on it, causing it to

shatter. Throwing aside the fragments,

he repeated the process

until he penetrated the underlying

limestone to a depth which

allowed him sufficient room to work

conveniently. The top and

freshly made face of the flint was

thickly plastered with potter's

clay, after which fire and water were

again utilized for clearing

away the limestone until a cavity was

formed beneath the flint

layer.

Thus a projecting ledge would be left, from which the

burnt parts were knocked off with heavy

stone hammers until

the unaltered flint was exposed; in the

same manner, blocks of

this were procured for converting into

implements. Where

the flint was well suited for the

purpose intended, or was easily

worked, the excavation was carried along

in the form of a trench,

the waste material being thrown to the

rear; under less favor-

able conditions the spot was

abandoned."

Vol. XXX -8.

114

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

Our examination of the quarries upon

Flint Ridge, made

with a view of ascertaining the method

of quarrying, does not

bear out and verify the findings of Mr.

Fowke concerning the

use of fire as an operating agent. On

the other hand, the evi-

dence found concerning the use of fire

as an agent in quarrying

the flint was purely negative, and I

doubt very much if fire was

used at all as an aid in removing the

flint from its natural bed.

I will go into detail concerning several

of the sites examined,

quoting from my field notes made at the

time of the excavations.

After a general examination of the

"Ridge" in company with

my assistant, Mr. Shetrone, we marked a

number of places for

examination, and this plan was

systematically carried out. The

first pit for examination was located in

the woods north and east

of the blacksmith-shop, about 300 feet

north from the road run-

ning east from the cross-roads. The property is owned by a

coal company with headquarters at

Newark, and is under the

direct supervision of Attorney R. E.

Jones, who aided us in

every way to make our work successful.

The pit was selected with a view of

finding the full vertical

ledge of flint exposed as the aboriginal

quarryman had left it.

In this we were partly successful, the

vertical ledge of flint

measuring three feet and seven inches,

while one foot and

eleven inches of flint had been removed

from the top surface

for a space of six feet by eight feet.

The flint on the top ap-

pears in nodular-like flat masses, from

two to three and one-

half feet in diameter, and the ancient

quarryman, taking ad-

vantage of the seams between the

nodules, was able to work

downward until the more desirable flint

was exposed. The top

of this quarry was covered with about

seven inches of soil,

accumulated during the more than a

century since the early

settler came to occupy the land. The top surface of the quarry

was more or less irregular, caused by

the early quarryman fol-

lowing the cracks or seams, or the lines

of least resistance in his

operations. Not the slightest indication was found in this

quarry to show that fire had been used

to supplement the ham-

merstones, several of which, varying in

size from about a pound

to one weighing upward of twenty-five

pounds, were found in

the pit. The hammerstones were made of

granite and quartzite.

Flint Ridge. 115

General indications shows that wedges,

perhaps made of wood

or horn, were used in dislodging the

desired pieces of flint.

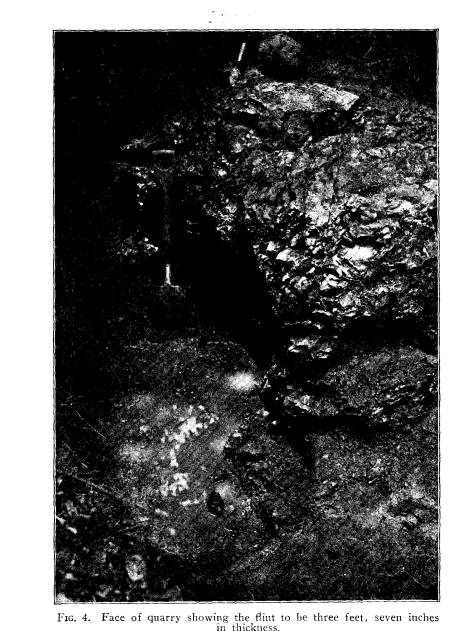

Fig. 4 shows the face of the quarry

where the flint is three

feet and seven inches in thickness. On

the top of the flint lies

a large hammerstone of granite,

weighing about twenty-five

pounds, which was found at the bottom of

the pit. A close

inspection of this cut will show the

cracks and seams found in

the flint, which we later quarried out

to ascertain why this part

of the stratum had not been

utilized. We followed the seams,

using iron wedges instead of wood and

iron hammers instead

of stone, and thus were able to effect

our purpose. The flint

was found to be practically worthless

for making into artifacts,

and the entire mass of three feet and

seven inches in vertical

height, two feet in thickness, and three

to four feet in length

would have been quarried out and cast

aside in order to carry

forward the quarrying operations, with a

vertical wall or nearly

so to work from. The ancient quarryman apparently did not

perform such arduous labor to secure the

coveted flint unless

absolutely necessary, as was found to be

true in many of the

quarries examined in the various

sections of "Flint Ridge".

We also quarried samples of the good

flint exposed on the

top of this quarry and found the

prevailing color to be a light

blue-gray, translucent in thin sections,

but frequently varying in

color from a dep red and yellow with

shades of lilac. In many

instances, seams of translucent

chalcedony extended into the

mass of the flint, sometimes only about

one-eighth of an inch

apart, giving the flint the appearance

of banded agate. How-

ever, this banded flint when struck with

a heavy hammer would

separate into needle-like forms which

made the flint worthless

as far as primitive man was

concerned. The lilac-colored flint

from this quarry was often filled with

very small geodes of

quartz crystals, which did not greatly

interfere with its use as

implement-making material.

Adjoining the lilac-colored flint was a

slightly yellow-colored

flint containing much chalcedony and

larger clusters of quartz

crystals. The ancient quarryman had

uncovered a cluster more

than six inches in diameter, the

crystals ranging in size up to

one-half inch in diameter, colored a

light amethyst, and very

|

|

|

(116) |

Flint Ridge. 117

beautiful. Another very interesting

deposit of flint, known as

the brecciated form, was found in the

highly colored red flint in

this quarry. These deposits are not much

larger than a man's

fist, are usually oblong in general

form, and are made up of

small angular fragments of flint which

seem to have been held

in suspension in clear or slightly

colored chalcedony.

After the work of examination of Pit No.

1 was com-

pleted, a good opportunity to try the

experiment of quarrying

by the use of fire presented itself, for

here was the bed of flint

uncovered and an abundance of dry wood

at hand. The fire

was kindled, and was kept burning for

two hours, producing an

intense heat on the underlying face of

the flint. The fire was

then removed and two buckets of cold

water were thrown upon

the surface. I fully expected the flint

to break in large pieces,

but it merely checked and cracked into

small pieces to the depth

of perhaps half an inch. After the conclusion of this experi-

ment it was apparent that fire as a

direct agent in the quarrying

of flint was perhaps not effective. In this connection I may

state that at no time during the

examination of more than

twenty-five of the pits and quarries in

this section was there

evidence of the use of fire in the

quarrying of flint. In several

instances small amounts of charcoal were

found in the pits, but

so sparingly as to indicate that fire

was in use around the

quarry but not as a direct agent in

quarrying the flint.

The next quarry of special interest was

No. 3. This quarry

is located not far from the outcrop

along the cleared field on the

Coal Company's property, perhaps a

little more than half a

mile directly north-east from the

blacksmith-shop. The pit was

seventeen feet long and fifteen feet

wide, and at no point in the

quarry had the bottom of the flint been

reached. Near the

center of the quarry, to the west, a

projection of flint extended

almost across the quarry. Examination showed that the deposit

was a very compact variety of yellow

flint, practically devoid of

seams, which baffled our own efforts at

quarrying with our

modern chisels and hammers. We were very

desirous of secur-

ing large samples of this highly-colored

flint, and preparing the

stone for a charge of dynamite, were

able to secure good speci-

mens of both yellows and reds. Many instances exist on the

|

(118) |

Flint Ridge. 119

"Ridge" where the ancient

quarryman was compelled to aban-

don the removal of fine flint, owing to

the absence of cracks or

other defects which would enable him to

work through to the

base of the deposit, and thus gain a

vantage point for further

procedure. Our blast removed the flint for about two feet

in depth and it apparently had the same

consistency throughout.

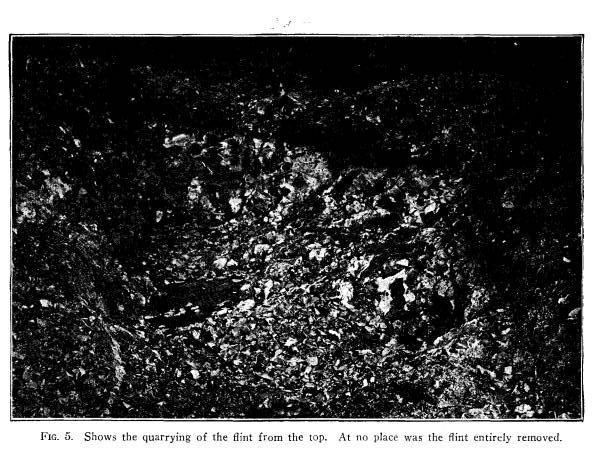

This quarry is shown in Fig. 5. The projection of flint

which the aborigines could not detach,

and that portion of the

quarry directly to the north, are shown.

The flint was quarried

from the top and shows many places where

cracks were fol-

lowed and the flint removed. Fire was

not made use of, as no

charcoal or other indications of heat

were present. This quarry

was noted for its highly-colored flint,

both red and yellow, and

the number of hammers, large and small,

found on its floor.

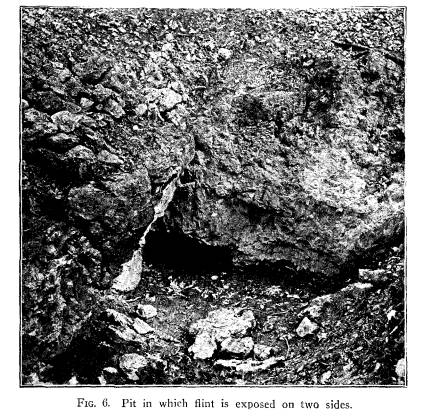

Pit No. 4, shown in Fig. 6, is of

special interest, as the

flint is exposed on two sides of the

pit, for a distance of almost

six feet. Cracks in the flint are quite noticeable. The crack

appearing at the angle of the two walls

is quite large and evi-

dently the face of the exposed wall

follows this crack. The

quarryman at this point worked from

beneath. He found

the lower stratum of flint could be

detached something like

limestone, as evidenced by the finding

of slabs of flint a few

inches thick and eighteen inches across,

while in another quarry

nearby slabs of flint that had been

quarried from the bed but

not removed, measured three feet in

diameter and two and

one-half inches thick. The flint

offering the least resistance

to detachment seemed to be at the bottom

of this quarry. This

flint was of practically no use to

primitive man but by its

removal he was able to reach the good

flint which, in this in-

stance, is practically in the center of

the ledge. Many large

single crystals of quartz, measuring

from three-fourth inch to

one inch in diameter were found in the

debris of the pit, and

some very large geodes of large-size

quartz crystals lay near

the bottom of the quarry. Large pieces of rock-crystal were

found in the workshops not far from this

region and we have

in the museum a single crystal three and

one-half inches in

diameter and five inches long, secured

and presented by Miss

Clara G. Mark. Miss Mark obtained the specimen, which

|

120 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications. was reported found on Flint Ridge, while making a study of the region. With the surface finds of large pieces of rock crystal, it would not be unreasonable to expect to find very large crystals or masses of rock crystal, in future quarrying of the flint. |

|

|

|

Pit No. 8 was an excellent example of quarrying from the top of the ledge. The pit is located about 200 yards from pit No. 4, further within the woods of Mrs. Loughman's farm. The pit was quarried from the east and extended into the solid flint eight feet with a width of seven feet. Here was a very good opportunity to clear out the quarry and take note of the |

Flint Ridge. 121

three exposed sides. It was soon discovered that the quarry-

man was guided by two cracks in the

flint running east and

west and about seven feet apart. On the north side the

crack was two and one-half inches wide

and on the south a

scant two inches wide. In the north-west

corner of the quarry

was a large piece of flint, measuring

three feet long and almost

two feet thick that had been broken

loose when the rents split

the rock. The break was caused by a large cavity in the flint

filled with beautifully colored crystals

of green, yellow and

red.

At this point a crack occurred north and south and was

perhaps one-half inch wide. The flint was six feet in thick-

ness and the cracks extended the entire

depth of the flint. The

flint, although very crystalline, was of

good quality for making

knives and arrows. The color was a light gray with blended

shades of red and yellow and often

certain sections would

shade into a leek-green, very likely due

to the presence of a

trace of iron silicate.

The flint had all been quarried and

removed from the pit

and at no point at the base of the flint

were there indications

of quarrying under the mass. However, on the top of the

west wall, the earth had been removed

and the top of the flint

quarried out in several places to the

depth of perhaps a foot,

showing that the quarrying was carried

on from on top. Many

broken and perfect hammer-stones of

granite were in evidence

in the quarry, but there was no

indication of the use of fire.

Pit No. 9 is located in the Mary

Loughman woods near

the north line of her property and about

200 yards

east of the

northwest corner of the tract. The

quarry was very much like

No. 3, as the quarrying was all carried

on from the top of the

deposit and at no place in this quarry

was the bottom of the

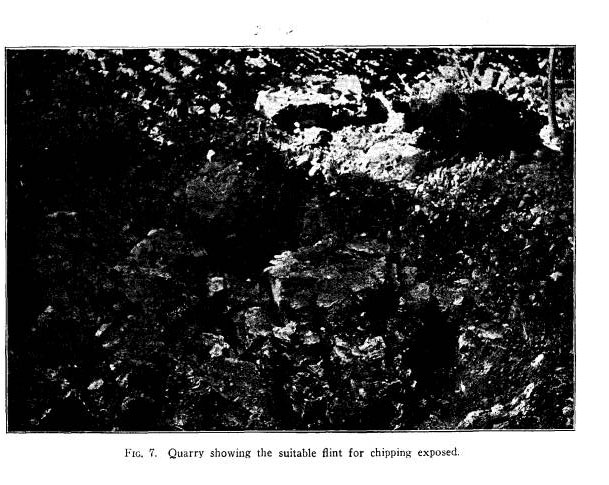

flint exposed. A good photograph of this quarry is shown in

Fig. 7.

The quarry is fifteen feet long and twelve feet wide

and the photo shows practically the

entire pit as the primitive

artisan had left it. The large mass of

flint suitable for the mak-

ing of artifacts is shown to the right

in the photograph. The

useless flint had been taken out from

three sides and the photo-

graph shows that the removal was under

way when the quarry

was abandoned. We removed the large block of flint, which

|

(122) |

Flint Ridge. 123

was of very good quality and practically

devoid of the small

drusy crystals so common in this quarry.

The color of the flint

is a light gray with a shading of

purple, red and yellow. The

block of flint shown to the left in Fig.

7 is a light drab in color

and the crystals shown on its top are

quite large, some of the

individual crystals found broken from

the clusters measuring

three-fourths of an inch in

diameter. Very little chalcedony

is found in the flint left in the

quarry, the flint which doubt-

less was of especial value because of

its quality and abundance.

The manner of quarrying is here best

shown of any of the

quarries uncovered.

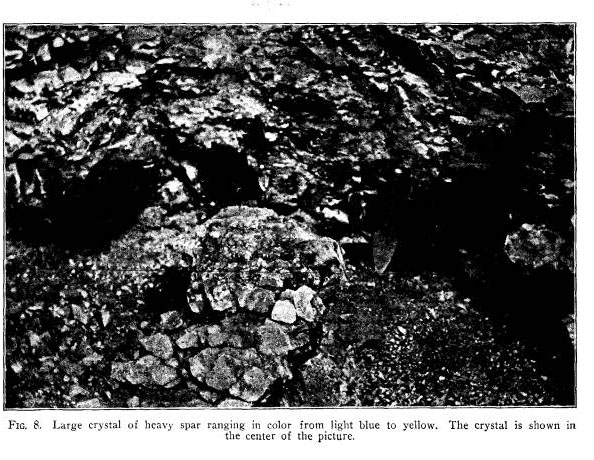

Pit No. 14 was of great interest. It is

situated in the east

end of the Mary Loughman woods. The

flint at this point is

covered with a very light covering of

earth. After the earth

was removed from the flint it had the

general appearance of

a large flattened nodule ten feet in

diameter. Primitive man

had quarried off about one-third of the

nodule, and found the

center contained a very large crystal of

heavy spar, light blue

to yellow in color. We quarried out the

crystal of heavy spar

and found it to measure more than four

feet in length, two feet

wide and about fifteen inches in

thickness. When first found

the spar was perhaps a solid mass, but

in time it became cracked,

as shown in the cut, Fig. 8, with the

exception of the center

which was removed intact. Heavy spar,

varying in color from

lemon yellow to light blue is found in

connection with work-

shops and apparently is associated with

the flint in many of the

quarries. Its use by primitive man is not apparent, as no arti-

facts made therefrom have been found in

Ohio. Perhaps its

extreme weight attracted the attention

of the primitive quarry-

man.

In all twenty-five different quarry

sites were examined in

the vicinity of the cross-roads and no

evidence was obtained

showing that fire had been used as an

agent in quarrying the

flint.

The examination was extended to the

eastern end of the

"Ridge" in Muskingum County,

where evidence of quarrying

was found upon the farm of Mr. James

Boyer. Mr. Boyer,

like many of his neighbors, is a

progressive farmer and all were

|

(124) |

Flint Ridge. 125

anxious to assist our survey in granting

permission to examine

quarry- sites on their respective farms,

as well as by presenting

specimens of flint found in the region.

On Mr. Boyer's farm the

quarrying is more extensive than

anywhere in the vicinity. The

flint is a light gray in general color,

very often mottled with

subdued gray and brown shading to dark

brown.

A quarry-site located in Mr. Boyer's

orchard was selected

and a space fourteen feet long and six

feet wide was removed

to the depth of six and one-half feet,

where we found the origi-

nal bed of flint. Of this, about one

foot remained in the quarry,

except at the south side, where the

entire bed had been removed,

apparently by the same method of

quarrying as was employed

at the cross-roads in Licking County.

The general blocking out

was done at the quarry or along the

hillside less than fifty feet

away. At no point on the spur of the

hill where the orchard

is located is there an outcrop of the

flint. Apparently the flint

has all been quarried out and worked

over and the refuse left

at the quarry-site, as indicated by the

five hundred or more

cubic feet of broken pieces removed in

the examination of this

quarry. Practically no earth was mixed

with the flint after the

surface had been removed, insects of

various kinds being found

to the bottom of the quarry as well as

the short-tailed shrew

(Blarina brevicanda) which was found

very frequently during

our explorations. This small mole is truly insectivorous and

had its habitat in the region where food

was abundant.

In the woods north of the orchard on Mr.

Boyer's farm is

an outcrop of flint, the remains of an

ancient quarry. The

debris was cleared from this quarry,

disclosing that the flint

had been removed to the bottom. The

perpendicular wall shown

as an outcrop was one side of a large

crack in the flint, extend-

ing almost perpendicular through four

feet of the top of the

deposit, then deflecting under the

ledge. The flint had all been

removed to this break in the deposit,

and the work of removing

the soil on the top preparatory to

further quarrying was under

way when the quarry was abandoned.

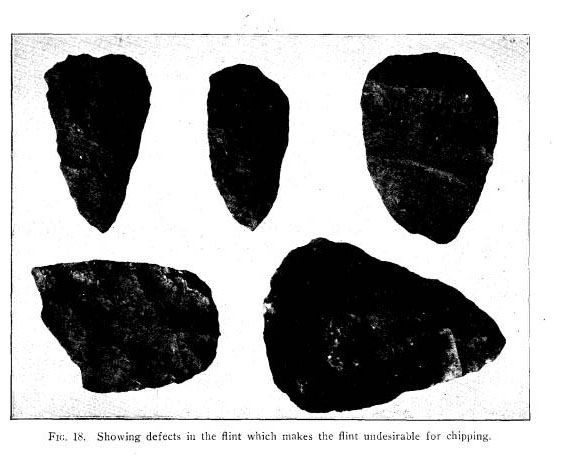

In all, thirty-three quarry sites were

examined by the sur-

vey, - twenty-five in the region of the

blacksmith shop located

at the cross-roads, Licking County, and

eight in the region of

126 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society

Publications.

Mr. Boyer's farm in

Muskingum County-and all showed the

same use of the hammers

and mauls in quarrying the flint. Per-

haps the hammers were

used in conjunction with wedges made

of wood and bone and

these latter in connection with large and

small wood pries or

levers. However, the use of wedges and

pries is only

conjecture, as no direct evidence in the thirty-three

quarry-sites was found

to substantiate this assumption. How-

ever, we feel the

primitive quarryman would use the simplest

tools that would

accomplish the desired results and that these

would be wedges of wood

and bone and pries both large and

small of wood.

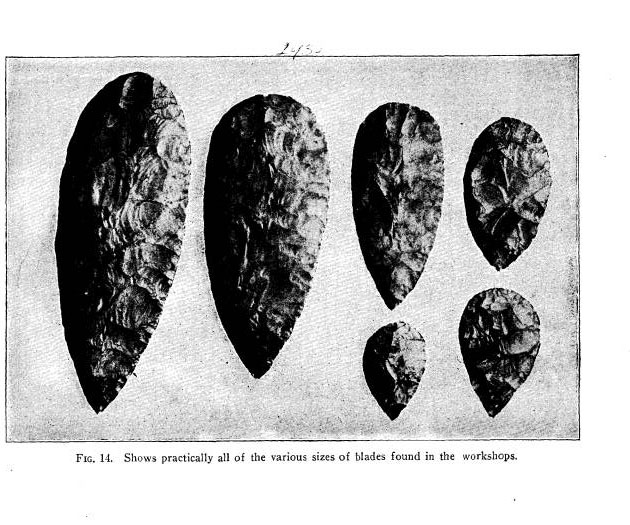

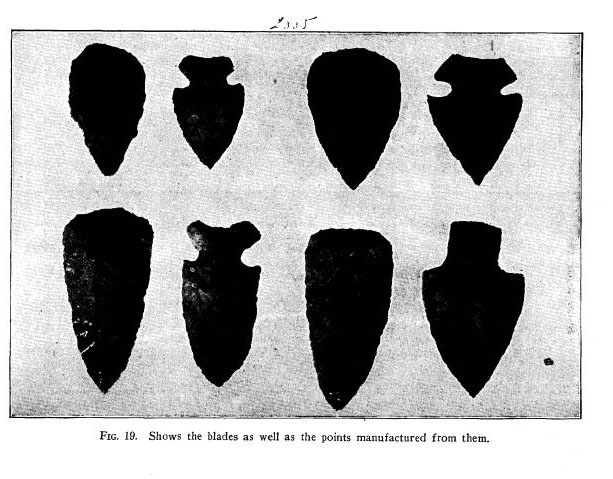

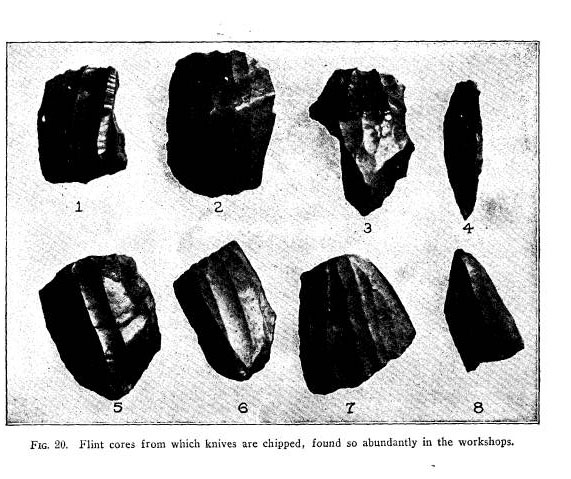

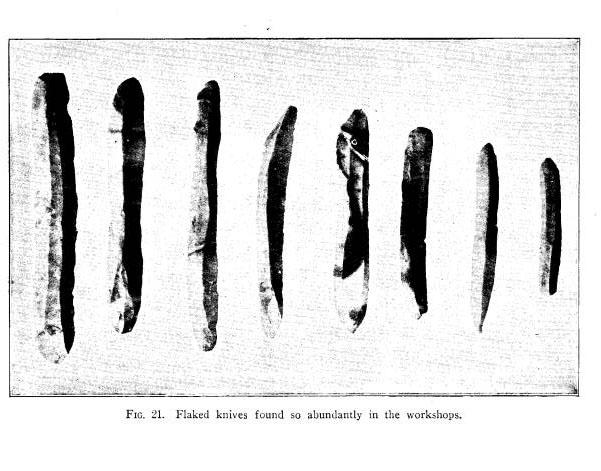

MANUFACTURE OF FLINT

ARTIFACTS.

The first step toward

the manufacture of flint artifacts is

securing the raw

material by quarrying and the first step in

shaping this raw

material, whether by breaking, flaking or chip-

ping, by percussion or

pressure, was the "roughing out" of

blades and cores into

convenient sizes. In this handy form they

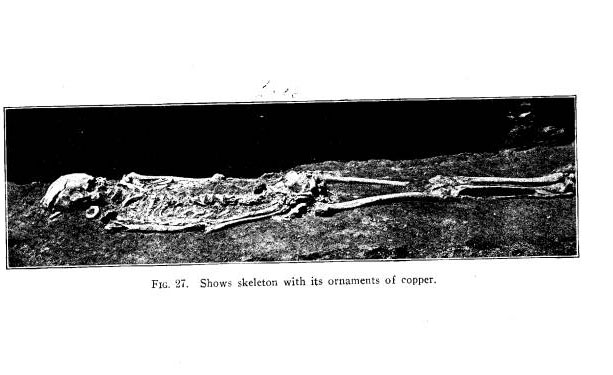

were transported to