Ohio History Journal

|

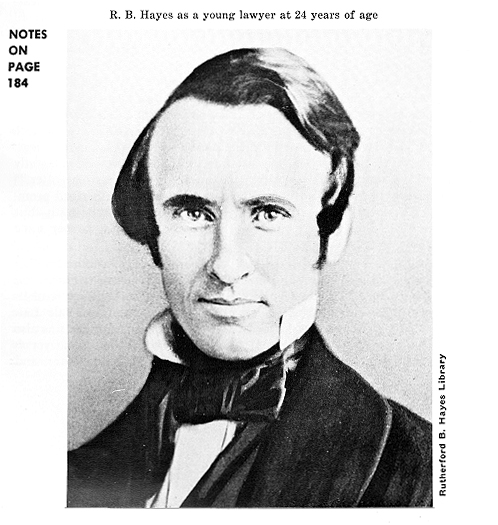

Rutherford B. Hayes Attorney at Law by WATT P. MARCHMAN Rutherford Birchard Hayes began life without a father, in Delaware, Ohio, on October 4, 1822, a sickly child whose health was of deep concern to his mother. His father, Rutherford Hayes, Jr., formerly of Dummerston, Vermont, who had been a merchant of the firm of Noyes, Mann and Hayes, and who had brought his family to settle in Ohio in 1817, died suddenly on July 20, 1822, before the birth of his son. He left his widow with an estate consisting of a brick town-house on William Street in Delaware, a farm on the Olentangy River about five miles north of Delaware, lands on the San- dusky Plains near Bucyrus, and interest in a distillery operated in partner- ship with Dr. Reuben Lamb of Delaware.1 When the future President was born, the family consisted of his mother, Sophia Birchard Hayes; her brother, Sardis Birchard, who was then twenty- two years of age and had lived with the Hayes family ever since the wed- ding of Sophia and Rutherford; Lorenzo Hayes, the older brother who drowned in January 1825 while skating on the Olentangy River; his moth- er's cousin, Arcena Smith; and his only sister, Fanny, who was to mature, |

6 OHIO HISTORY

marry, and later live with her family in

Columbus, Ohio.2 Sardis Birchard,

when twenty-seven years of age, left the

Hayes household to become a

pioneer settler, merchant, and later the

first banker of the small community

of Lower Sandusky in northern Ohio, near

Lake Erie.3

In the 1830's, a widow had

limited opportunities in Ohio to provide her

children a good education. The Hayes

children, Fanny and "Rud" (as he

would be called by intimate friends) ,

attended the schools available to them

at Delaware. They were eager students,

particularly attracted to the roman-

tic stories of Scott. Rud continued his

studies at Norwalk Academy, Nor-

walk, Ohio; and then, through the urging

of an influential family friend,

Judge Ebenezer Lane of Sandusky, Ohio,

was sent to the Isaac Webb Acad-

emy at Middletown, Connecticut, where

Judge Lane's son, William, was

attending.4 Although the

youthful Hayes was agreeable to being educated

in the East, he preferred Ohio; so when

his mother, who needed him nearer

home, thought of sending him to Kenyon

College after he had finished the

Academy, he encouraged her to decide

upon that Ohio college. He entered

the freshman class there in November 1838.5

Hayes's mother and sister were ambitious

for him--strongly so; but they

feared that by too much application to

his studies he would damage his

health. He had not been robust. They

balanced their appeals by words of

caution. As for Hayes, he preferred

hunting as much as he could; and when

he thought of the future, it was in

terms of being a farmer.6

Inevitably, though, the time arrived

when he felt the need to decide on a

future. This was in his second year at

Kenyon. "What shall I do after leav-

ing college?" he asked his mother.

"Now, I . . . have no fears that I shall

starve as long as I have 'teeth and toe

nails.' If I could have a good farm, I

would have to be a farmer; but if not, I

shall spend all the money I can

lay fingers on to get a good and complete

education, and when I am entirely

run out [of money], I will practice

law in some little dirty hole out

West."7

His mother answered him at once, for

both she and her brother Sardis

hoped he would choose law. "I do

not think you need to feel any anxiety

about what calling you will pursue after

you leave college. With good health

and a good education, with good

principles, you have nothing to fear.

Thousands of such young men are wanted

in every occupation. If you study

law, it will not unfit you for any more

favorable pursuit that may offer."8

Then she wrote her other brother,

Austin, in Vermont: "Rutherford prom-

ised his Uncle Sardis that he would

study law, and he intends doing it--but

says, if he don't like it better than he

expects, he will be a farmer some

time."9

Hayes had some ideas about the legal

profession, but he was not sure that

he would be equal to it. One of his

tutors at Delaware, Sherman Finch, was

a practicing attorney. His own father's

younger brother, William Ruther-

ford Hayes, of New Haven, Connecticut,

had graduated from Yale Law

School but had given up practice because

of ill health; and there was also

an uncle by marriage, Congressman John

Noyes who had been a lawyer as

well as a partner of his father in the

mercantile firm of Noyes, Mann and

RUTHERFORD B. HAYES, Attorney at

Law 7

Hayes, in Dummerston. In fact, his Uncle

John Noyes had been a tutor of

the great Daniel Webster at Dartmouth.

[In an appraisal made at this time,

Hayes said of himself]: I know I

have not the natural genius to force my

way to eminence, but if I

listen to the promptings of ambition . .

., since I cannot trust to inspira-

tion, I can only acquire it by

"midnight toil" and "holy emula-

tion". . . .10 [He thought about

remaining an additional year at Ken-

yon.] I wish to become master of logic

and rhetoric, and to obtain a

good knowledge of history . . . .11

If I would attain the eminence in my

profession to which I aspire, I

must exert myself with more constant

zeal and hearty good will than I

ever have before. The life of a truly

great lawyer must be one of se-

vere and intense application; he treads

no "primrose path"; every step

is one of toil and difficulty; it is not

by sudden, vigorous efforts that he

is to succeed, but by patient, enduring

energy, which never hesitates,

never falters, but pushes on to the

last. This is the life I have chosen.

I believe it is a happy one.12

Whenever he could find an opportunity,

Hayes attended court and lis-

tened to any proceedings which might be

in progress. One case which he

witnessed at Gambier involved a school

boy who attempted assault on the

mistress of the district school. She

sent for the superintendent who whipped

the boy "slightly"; the

superintendent was "taken up and tried." The trial

was honored by the presence of all

the students," Hayes said. He sketched

the principals involved and reported the

proceedings in detail to his sis-

ter. The lawyers, he said, were

"O'Neil, . . . easily enraged, irritated"; and

Columbus Delano, "a cool, witty,

first-rate man." The justice, "a good

farmer. . . . This trial pleased me so

much,"13 he confessed. As Hayes ma-

tured, interest in people grew strongly

in him, and it would be as a crim-

inal lawyer that he would excel.

While visiting at Columbus during the

Christmas holidays, he attended

the United States Circuit Court and

listened to arguments of some of the

ablest lawyers in the state. "I

never hear a speaker but that I am encour-

aged to renew my exertions," he

said.14

The thoughts he had about an extra year

at Kenyon did not materialize.

His hard study, though, made him

valedictorian of his class. Instead of stay-

ing at Kenyon, he went to Columbus to

live with his sister and her family

and to study law under any good lawyer

who would help him. Attorney

Thomas Sparrow was recommended. "I

went to Mr. S. and have been study-

ing in his office ever since,"

Hayes wrote his uncle. "I like the study and

am well satisfied with my teacher . . .

. He gives me more instruction than

law students usually receive, so that in

the minutia of legal practice I have

a better opportunity to learn than I

should have with an older and abler

man. . . . I am also studying

German," he added. "My legal tuition costs

me nothing; my German, twelve dollars

per quarter. The first I consider

cheap; the last, dear."15 The

study with Thomas Sparrow continued be-

tween October 17, 1842, and August 5,

1843, and then Hayes was given an

8 OHIO HISTORY

informal certificate certifying that he

had "with great dilligence [sic] regu-

larly prosecuted the study of the

Law" and that he was "a young man of

good moral character."16

Sardis Birchard in his multifarious

operations at Lower Sandusky would

have constant need for legal advice, but

he did not think his nephew was yet

adequately prepared for law practice.

Since Hayes had elected to enter

upon a career in law, Sardis decided to

send him to the leading law school

in the country--the Law School at

Harvard University--to study with the

eminent jurists and teachers, Simon

Greenleaf and Joseph Story. The chal-

lenge was one that Hayes was glad to

accept. He left for Cambridge and en-

tered the term at Harvard commencing on

August 28, 1843. "Whatever

resolution and ability I have," he

commented, "shall now be brought out."17

Reporting to his uncle within the month,

he wrote: "The advantages of

the law school are as great as I

expected, and the means of passing time

pleasantly, even greater. It is full as

well, perhaps better, that I studied in

an office before coming. I am occupied

but I am not pressed hard. . . . The

instructors I like very much. Our

recitations are so interesting that there

is no temptation to neglect them. We are

under no compulsion in anything,

except paying our bills."18 His

classroom was more than a recitation hall.

"The first men in the country have

been in, so I have a fine opportunity of

seeing the great ones; besides, we often

hear them, for Judge Story, being

the Circuit Judge of the United States

[as well as professor] is often called

upon to decide cases in his

jurisdiction. . . . Judge S. is a very pleasant man

-gets acquainted with the students very

quick and is very fond of cracking

jokes with them. In the recitation room

he indulges in a great deal of wit

and humor. . . . A more industrious man

I never knew. He does an amount

of labor that would startle a young man

. . . .

"In [our] Moot Court . . . Judge S.

always presides as if in a real court

and gives his decision in due form.

Those who are acquainted with our

manner of doing business frequently

send, when they have a knotty ques-

tion, to learn if it has been discussed

in Moot Court. . . . The Judge is fond

of Styling it the high-court of appeals

for the whole world."19

Hayes remained at the Harvard Law School

for three terms of twenty

weeks each, and received his Bachelor of

Laws diploma on August 27, 1845.

In addition to his law studies, he had

attended lectures and addresses given

by such eminent men as John Quincy

Adams, George Bancroft, Richard H.

Dana, Jr., Henry Wadsworth Longfellow,

Jared Sparks, and Daniel Web-

ster. For exercise, he had played ball,

which he liked especially.20

With his studies now completed, where

would he go to begin his law

career? Earlier, he had consulted his

professors and members of his family

on this point. His mother, at the time,

was living with his sister Fanny and

her family in Columbus. They wanted him

to come to the capital where

laws were made, live with them, and be

in the midst of legislative life. His

Uncle Sardis was in Lower Sandusky, a

small village where, from time to

time, he had need for a lawyer and

wanted him to come there. Professor

Greenleaf's advice had been that

"the young man who goes into a large

RUTHERFORD B. HAYES, Attorney at

Law 9

place, unless under circumstances

peculiarly favorable, commits an error.

If he settles in an obscure place where

he is sure of some business, he is

much more likely to reach the ultimate

object of his desires." Hayes had

thought so, too; it was what he wanted

to do; so he decided upon Lower

Sandusky. "If I do not like my

first choice, I can make another," he told

his sister.21

The return to Ohio was made early in

February 1845. About a month

later, on March 10, at Marietta, he

appeared before Justices Matthew

Birchard and Reuben Wood for his bar

examination. While preparing for

it, he "had a set-to with the

Revised Statutes of Ohio, which occupied my

leisure hours about two weeks. I then

hastily reviewed Blackstone, after

which I took up Swan's new book on

Practice, and read a few chapters upon

the same subjects with that portion of

Chitty which we read with [Simon]

Greenleaf."22 Charles

Backus Goddard, of Zanesville, father of a Harvard

classmate, Daniel Convers Goddard,

"puffed me [up] a little, got a com-

mittee appointed, who spent an hour or

two in asking questions, such as

anyone who has Bl[ackstone]

Com[mentaries] and a little practice ought to

be able to answer. The only

"dead" [mistake] I made was on some simple

matter in bailments; a title which you

know is a hobby at Cam[bridge]

and about which I know more than any

other. I became some acquainted

with Goddard and like him much. . . .

There were two men examined with

me--one (Akins) a pretty good lawyer

about fifty years old; and the other

(a Mr. Evans), a very stupid fellow

about thirty.23 Members of the Ohio

Supreme Court meeting in Marietta at

this time were Ebenezer Lane,

Chief Justice, and Justices Reuben Wood,

Matthew Birchard and Nathaniel

C. Read. Later, Matthew Birchard would

claim relationship.24

The new lawyer arrived at Lower Sandusky

about a month following his

admittance to the Ohio bar. In the

meantime, he had had a leisurely visit

at Kenyon College, and spent several

days in Columbus with his mother

and sister and her family. At Lower

Sandusky he settled down in an office,

"a very convenient little tenement

about 15 ft. sq.," on the west side of

the Sandusky River. "I know of no

person here who will be just the one

for a companion," he wrote his good

friend and fellow-lawyer, Will Lane,

at Sandusky. "It is said that two

of our lawyers [C. K.] Watson & [B. J.]

Bartlett intend leaving . . . . That

would leave but six lawyers in the place,

counting 'the undersigned' as only one."25

To his sister he said, "The law-

yers all treat me kindly and the only

ones I could ever think of dreading

are decidedly friendly."26

As Hayes's law career progressed, he would tend

to become more and more a "lawyer's

lawyer," in much demand as a con-

sultant and associate in complicated

cases.

As for living quarters at Lower

Sandusky, Hayes decided to share a room

with a cousin, John Rutherford Pease, a

son of his Aunt Linda Hayes

Pease, at Captain Samuel Thompson's

tavern on the turnpike, east of the

river, previously known as the

"Blue Bull Tavern." His Uncle Sardis had

for many years lived with his friends,

the James Vallettes, about two miles

southwest of the center of the village.

10 OHIO HISTORY

The dust had barely settled about him

before he was given a case. The

State of Ohio, for the use of Alvin

Coles, a former partner of his Uncle's,

now Commissioner of Insolvents for

Sandusky County, brought an action

against John Strohl, formerly county

sheriff, and his sureties, Barnhart

Kline, Hugh Bowland, John Bell, John M.

Smith and Isaac Swank, in a

plea of debt. Hayes conducted the suit

for the State of Ohio. The back-

ground was that Jacob Strohl, having

been elected sheriff of Sandusky

County for two years at the general

election in 1844, was bonded on No-

vember 26, 1844, and in the course of

his duties was required to execute a

judgment which Alvin Coles had obtained

against Edward Wyler for over

$200. He was commanded to levy against

Wyler's goods. Accordingly, in

February 1845, the sheriff attached

Wyler's property consisting of a number

of horse collars, saddles, bridles,

"stoger" boots, calf and deer skins, leather,

and "one chest of Hyson tea."

The goods were offered for sale on March 11,

but only a few of the horse collars and

bridles were sold, realizing a total

of only $16.18, because of lack of

bidders. Thereupon, Sheriff Strohl re-

signed his office on April 3, but failed

to deliver the money and property

to the coroner of the county, as

required by law. After which Alvin Coles,

in the name of the State, sued the

sheriff for $5,000 damages, and the bonds-

men for $15,000, the amount of their

bond.27

Hayes told his sister: "I assisted

in pettifogging [i.e., conducting unim-

portant law business] a case last week

and have hopes of becoming quite a

pettifogger in time. . . . My prospects

as to business are better than are

given to most young lawyers. The fact

that Lower Sandusky is what it is,

makes it just the place for me. . . .

Lower Sandusky is a town in which the

houses, fences &c (with one

exception) were built not merely without any

good taste, but with apparent disregard

of all taste and comfort." He had

found his "dirty little hole out

West."28

Before his first case was resolved, he

was asked to assist with a criminal

action which excited considerable

interest in the county, in which he, him-

self, was one of the victims. Arrest

proceedings had been brought against

Albert G. Clark, a young man who, with

his recent bride, was staying at the

Tompson Tavern. For the past year Clark

had been in the community

studying law with a view of being

admitted to the bar. He was indicted for

entering the room shared by John R.

Pease and Hayes at the Tompson

Tavern, on the night of May 21, 1845,

and stealing Pease's wallet containing

over $100 in cash, three or four hundred

dollars in securities, his watch, and

also Hayes's watch (the "one-handed

one"). Clark pleaded innocent and

was defended by B. J. Bartlett.29

Lucius B. Otis was the prosecuting

attorney, and he was assisted by

Cooper K. Watson and R. B. Hayes in

gathering evidence against Clark.

"I have been at Sandusky City,

Milan and all about," Hayes wrote his sis-

ter, "hunting evidence to convict a

very clever, genteel knave, formerly one

of Herman A. Moore's stewards."30

During Clark's trial before Judge M. H.

Tilden in the Common Pleas Court, it was

brought out that Clark had

practiced a "series of impositions

upon the unsuspecting" in the commun-

RUTHERFORD B. HAYES, Attorney at

Law 11

ity and neighboring area, and had tried

to alibi that he was in Elyria the

night of the robbery. But witnesses

placed him in Clyde at 9 P.M. that night,

and the following morning, at an early

hour, "he was seen riding at a gal-

lop, about 7 miles from town, going

east." He had passed several bills at

different places after the robbery, but

on being arrested, nothing was found

on him but "a 10 cent or shilling

piece." He did not offer any evidence to

support his alibi but relied on the

insufficiency of the prosecutor's testi-

mony to convict him.31

The jury, hearing all the evidence,

deliberated only a few minutes and

brought in a verdict of guilty. Though it

was not brought out during the

trial, Clark had confessed his guilt to

his counsel shortly after he was ar-

rested, and had turned over to him the

money and watches, except some

money which he had spent, and told where

he had thrown the bundle of

notes. The judge sentenced him to serve

five years in confinement at Co-

lumbus,32 and Sheriff Daniel Burgner,

"a sort of client" of Hayes's, de-

livered the prisoner to the penitentiary

along with a personal letter Hayes

wrote to his sister about the case.33

"The thief," he said, "was a law-student,

a 'genteel good-looking Loco Foco

orator' who went about last summer

abusing [Henry] Clay for bad moral

character."34

The Supreme Court held a session in

Lower Sandusky the week of August

20-25, 1845. "One of my old friends

named [Stanley] Matthews, came from

Cincinnati to [be] examined for

admission to the bar. I was one of the com-

mittee to examine him. He graduated

[from Kenyon] about two years be-

fore I did and was beyond dispute a

better lawyer than any of the examin-

ing committee."35 Matthews,

since his graduation, had been practicing law

in Tennessee as well as editing the

Tennessee Democrat. A few years later

he and Hayes would serve in the same

regiment in the Civil War, and

Hayes while President would nominate him

a justice of the United States

Supreme Court.

At the end of his first year of

practice, Hayes summed up what he thought

about it. "I had often been told

when I was studying law that the Study

was very pleasant, but the practice dry

and tedious. I have thus far found

the contrary nearer true. The study the

first year was certainly the most

vexatious and tedious of anything I ever

attempted; the practice . . . is,

upon the whole, quite interesting. Much

more so than I ever anticipated.

. . . Judge Tilden and Judge E. Lane

both told me . . . that I deserve suc-

cess for the wisdom I had shown, in

spite of appearances, in selecting my

location."36

On April 1, 1846, at the onset of his

second year as a lawyer, Hayes

formed a partnership with Ralph P.

Buckland, whom he considered to be

the leading legal mind in the village.

Buckland was to have a distinguished

career as an officer in the Civil War,

and after the war both he and Hayes

would serve together in Congress. The

partnership came about in this way,

Hayes recalled:

On Tuesday or Wednesday, about the 7th

of February, 1846, a

crowded Stage, of the Concord pattern,

belonging to the line of Neil,

|

|

RUTHERFORD B. HAYES, Attorney at

Law 13

in that way may be of no benefit.

Birchard bought the tract at Sheriff's sale

in 1832 when it was sold under a decree

rendered in 1826 in favor of Thomas

L. Hawkins against Thos. E. Boswell and

others, all the defendants non-

residents of the State, for a large sum

of money, over $1,800. The grounds

upon which the claim is now raised are

not known, but it is supposed that

they think the Decree void for want of

jurisdiction over the parties--that

a money decree against persons, all

non-residents, is void. I send you a copy

of the proceedings upon the record. . .

. You know, I suppose, where the

tract lies; the south line crosses the

Pike a few feet west of Judge [James]

Justice's house at the foot of the

hill--Dr. [L. Q.] Rawson's house stands on

it. It is so valuable that Birchard

& Dickinson will not give it up without a

fight."40

And they did not. Since the litigation

was between citizens of different

states, the case went first to the

United States Circuit Court and thence to

the Supreme Court. As the case

progressed, Henry Stanberry was added to

Birchard's counsel, and he was sent to

Washington to present the case to

the Supreme Court. Thomas Ewing assisted

as opposing counsel.

During litigation, Rodolphus Dickinson

died, and the suit before the

Supreme Court was then entered in the

name of his heirs in December

Term, 1849, as Thomas E. Boswell's

Lessee, Plff., vs Lucius B. Otis, admin-

istrator, Margaret Dickinson, widow,

and Edward F., Julia S., Margaret 0.,

John B. B., Rodolphus, Martha, Jane,

and James A. Dickinson, minor chil-

dren of Rodolphus Dickinson, and

Their Guardian and Next Friend, by

L. Q. Rawson. The Supreme Court decision was delivered by Justice

John

McLean, an Ohioan, in favor of the

plaintiffs.41

The blow was a severe one to Sardis

Birchard who was working hard to

develop the town he adopted, loved, and

in which he had made his home.

"Watson was here a few days

ago," Hayes sent word to his uncle from

Cincinnati, "on his return

from a visit to Boswell [in Kentucky]. I saw him

by a mere accident. I think he was not

anxious to see me. He says you are

reported to have been a good deal excited

when you learned the result [of

the Supreme Court decision] and talked

about raising a little army and

making resistence! &c &c.

'Boswell,' said he, 'asked me the value of the

property. I told him I couldn't tell. It

would be in litigation for ten years,

see-sawing between the state and federal

courts, and no man in Ohio would

dare to buy it.'"42

Even though he had moved to Cincinnati

since the case began, Hayes

continued to be his uncle's chief legal

adviser on it. In May 1851, Hayes

sent word to Birchard, "I have

received a letter from Bartlett today. He

says he has full powers to sell or

settle Boswell's claim. Is anxious to do so.

That there is a project on to sell out

the claim, a part down and the balance

contingent on the result of the suit;

that he don't like the scheme; pre-

fers to settle with us; that we must

settle 'soon' if we expect to deal with

him; that the town is injured by the

controversy &c &c. and he wishes to

see it ended. In reply to this, I say to

him, by this mail, that I prefer settling

with him to anybody else, that I

anticipate difficulty by reason of your

14 OHIO HISTORY

pride in the matter, that I view it

merely as a dollar and cent affair to be

decided by pecuniary interest, that the

fight is likely to ruin the property

for all sides for a long while, that a

part now is better than the whole here-

after, and that I will come out and talk

the matter up with him about the

middle or 20th of June."43

This notation follows in Hayes's Diary:

"June 17, 1851--By Railroad to

Shelby and Sandusky; next day to

Fremont. There settled with Bartlett

Uncle's intermible lawsuit. Good."

There was another legal battle in which

Sardis Birchard became involved,

this time with the Junction Railroad

Company. Representing him were

Buckland & Hayes. He sought an

injunction against the company in order

to prevent them from building a bridge

over Sandusky Bay, as the company

planned to do in extending its lines in

northern Ohio. The case was quite

involved, but Sardis believed that a

bridge across the Bay would interfere

with ship traffic, making shipping rates

higher between Lower Sandusky

and the bridge. The case was of long

duration; was carried into the United

States Supreme Court; and Hayes was to

continue to work upon it after he

had moved to Cincinnati.44

On April 11, 1853, Hayes jotted in his Diary:

"Argued my first case in a

court of the United States last week. .

. . This was my first oral argument.

Mr. [George E.] Pugh and Thomas Ewing

were on the same [our] side.

Judge Lane, Mr. Beecher, and Judge

Andrews opposed. The case is one of

great importance, viz, application to

restrain the Junction Railroad Com-

pany from crossing Sandusky Bay on the

ground, first, that it violates their

charter, and second, that it would

obstruct the navigation of the bay."45

About a month later the injunction was

granted.

Hayes's health usually had been fairly

good, but the year 1847 had been

severe on him physically. The first week

of the year was a wet, cold one.

"We have had a glorious flood

here," he wrote his sister. "The water be-

gan to rise New Year's day and by the

night of the 2nd, Pease and myself

could not get to our boarding house, dry

shod. I spent the whole forenoon

[next day] building a raft to get over

to this (the "Babylon") side to see

the fun. In the afternoon I and Pease

got over. We chartered the finest

boat in Lower [Sandusky] and in company

with Sarah Bell's husband [John

M. Smith] and went to getting out the

women, children, hogs, cows, and

cats. In this way we spent part of

Sunday and all of Monday, sailing all the

way to our meals -- over Pease's

garden fence and through the tops of apple

trees, beating Vermont snow drifts all

to death. It was royal sport. I've not

felt so much like a rowdy boy in a long

time. Of course, the damage was

something -- though trifling in

comparison to the losses of farmers &c

up about Tiffin . . . But this side of

the River did not suffer any; since the

wash many years ago, they have raised it

out of the reach of the River."46

That spring Hayes was to suffer from a

raw throat and could not shake

it off. He told his friend, Will Lane,

"at the time of our flood . . . (an era

in the Annals of Lower Sandusky), I took

a severe cold which clung to

me so long that a month or two ago it

really unfitted me for working or liv-

RUTHERFORD B. HAYES, Attorney at

Law 15

ing within doors. My friends at once

became unnecessarily alarmed and

determined that I should quit practice

and 'go to grass' for the space of a

year or more . . . I have been taking

Dr. Mussey's prescriptions about

three weeks, viz:. daily potations of

Snake Root, a sort of fish oil, and

Whiskey well shaken by exercise in the

open air. The result is I have re-

covered my usual strength, and color,

and though my cracked weasand

[throat] still bleeds occasionally, it

is rapidly healing."47

He was advised by his physician to leave

the office for a while, and he

thought of joining the army as a

volunteer for service in the Mexican War.

His landlord, Captain Samuel Thompson, a

veteran, was raising a company

for service. Hayes went down to

Cincinnati for a physical check-up, carry-

ing with him letters of introductions

from Judge Lane and others which

he hoped would help him in getting a

commission. Both Dr. Mussey and

Dr. Dresbeck who examined him, agreed

that he was not fit to go to Mexico,

and he was forced to change his plans.

His sister was elated; she had op-

posed the idea vigorously; so had his mother

and uncle, though they were

careful in stating their objections.

Instead, Hayes and his room mate, John

R. Pease, went off to New

England, to be gone from July 20 to

September 26, 1847. They went to

visit relatives, and Hayes wanted to see

a girl, a cousin of Will Lane's, whom

he had met when she was on a visit to

Sandusky. He thought a great deal

of her; thought of her, in fact, as a

wife. "She is a home body--she is pious

(very) after the Puritanical School

(N.B., suits mother); a little--perhaps

a good deal--aristocratic (N.B., suits

you)," he wrote his sister about Fanny

Griswold Perkins. "A mixed

disposition, half frolicksome--half poetical

(N.B., suits me) a decided taste for

reading and music, and I think per-

fectly sincere. Taking all together,

that's as good character as could be

desired."48

But it was not to be; her mother and

sister objected to Fanny's marrying

and living in the West, and Hayes would

not live in the East. He did not

press her; they parted friends, but

regretfully. ". . . So ends my first love

affair . . ."

Well, let it pass--there's other gals,

As beautiful as she;

And many a butcher's lovely child

Has cast sheep's eyes at me,

I wear no crape upon my hat,

'Cause I'm a packin' sent--

I only takes an extra horn,

Observin' LET HER WENT!49

The trip was beneficial to his health

even if he had been disappointed

in love. He returned to his office but

there was net much of interest to

do, only routine matters, minor

disputes, and collections. His social life

was not particularly stimulating,

either; occasionally there was a ball, an

oyster supper, sleigh rides in the

winter, and not much else. When court

was in session, there were short-lived

flurries of activity. But the routine

16 OHIO HISTORY

was beginning to bore him; he was not

making the progress he had hoped

for.

"As the period I had fixed for my

pilgrimage here is within a year or

two of its close," he wrote his

sister in July 1848, "it is about time to de-

termine what community shall be next

blessed with my presence . . . I'd

like to live in Cincinnati, if I could

get 'a fair start.'"50 He had been im-

pressed with the "Queen City"--the

largest city in the West, when he

went there to try to join the army for

the war with Mexico. "I want to

spend another fortnight in Cincinnati to

satisfy myself whether an attorney

of my years and calibre would be likely

to get business enough to pay

office rent in that growing

village."51

Sardis Birchard's health was especially

bad the winter of 1847-1848, but

by the following fall he was able to

enjoy stumping Sandusky County with

Hayes in support of Zachary Taylor.

After the election both men decided

to spend the winter away from Lower

Sandusky by exploring the new

state of Texas and visiting Hayes's

Kenyon classmate and lifelong friend,

Guy M. Bryan, of Brazoria. This southern

friend and his trip would have

a strong influence later upon Hayes's

views regarding the South and its

problems. They left Lower Sandusky on

November 21 for Columbus via

Mansfield and Mount Vernon, and arrived

in Cincinnati on Friday, De-

cember 8, to board a river boat, the Moro

Castle, for New Orleans, and

the ocean steamer Galveston for

Texas, arriving at Galveston December

26, 1848. The trip and visit were an

exciting adventure, invigorating,

healthy for both.52

Returning with his uncle to Lower

Sandusky late in April 1849, Hayes

resolved to "finally dissolve with

Buckland preparatory to bidding adieu

to Lower Sandusky." But he was

prevented by cholera in Cincinnati from

going there immediately. In the interval

he helped his uncle with some

land matters, "being about half

enough to occupy my time," did some law

reading, and attempted to put himself in

a frame of mind "so as to be

able to survive the two or three

briefless years which probably await me

at Cincinnati."53 His

mother understood some of his thoughts. "If you

have no business of importance the first

year or two, don't be discouraged;

I fear you have not been thrown quite

enough upon your own resources

in early life to launch your Barque

alone in so large a sea, without some

anxiety to yourself."54

Before departing Lower Sandusky, he

conducted one final bit of busi-

ness which would have a permanent effect

upon the little community. On

behalf of his uncle and other leading

business men, he selected a new name

for the village and presented the

petition to the Common Pleas Court for

the change. The name proposed was

"Fremont," in honor of the noted

western pioneer.55

Judge E. Lane, the family friend,

suggested that Hayes form a partner-

ship in Cincinnati with an established

lawyer there. He had in mind a

Swedish Frenchman, James Florant Meline.

But the proposed partnership

did not materialize, and Hayes decided

to go it alone, as he had expected

RUTHERFORD B. HAYES, Attorney at

Law 17

to do in the first place. In December

1849, just before Christmas, he made

the journey in company with Judge M. H.

Tilden, who was also trans-

ferring his business to Cincinnati. As

soon as he could after arriving, Hayes

rented for $10 a month the use of one

half of an office in the new Law

Building on Third Street in the very

heart of the city. He shared an of-

fice with John W. Herron, a young lawyer

from Chillicothe, who would

later become the father-in-law of a

future President, William Howard Taft.

There was another interest for him in

Cincinnati besides starting his

law career over again. In 1847, while

Hayes was visiting his mother in

Delaware, he had met at the sulphur

spring there a young girl, Lucy Ware

Webb, only sixteen, whom he could not

forget. His mother knew her,

and later she would urge his

consideration of her as a likely wife. In Cin-

cinnati she was a student at the

Wesleyan Female College, shortly to grad-

uate, and was living with her mother and

two brothers, who were studying

medicine.

With no business for some weeks, Hayes

took every sound avenue to gain

new friends and to become known. He

attended lectures, spent one or two

evenings a week with the ladies,

attended the Episcopal Church, the gym-

nasium, and became a member of a

"delightful little club [the Literary

Club of Cincinnati], composed of

lawyers, artists, merchants and teachers,

which meets once a week--for debates,

conversations, etc." He also joined

the Odd Fellows in Cincinnati; he had

been a member of the order in

Fremont. And he attended the Sons of

Temperance meetings and frequent-

ly gave addresses there and elsewhere,

seeking opportunities to do so.56

It was during his second month in

Cincinnati that he was able to note in

his Diary: "Received my

first retainer in Cincinnati--five dollars from a

coal dealer to defend a suit in the

Commercial Court."57 In another month

he was able to say, "My busiest

week . . . I mean, real business, in addition

to the business of 'sparking.' I have

had ten new claims in Commercial

Court, one title to examine and make out

papers, etc."58 But this first

year in Cincinnati was, as he had

expected, a dull one in law practice. He

filled his time with social activities,

giving talks and circulating among old

and new friends.

The year 1852, when he was thirty, would

be a milestone in his life. At

the beginning of the year he would be

appointed by the court to handle a

criminal case, and at the year's end he

would have a wife. On January 17,

1852, Hayes recorded that he made

"in reality my maiden effort in the

Criminal Court." He had been named

defense attorney for Samuel Cun-

ningham, a young man of respectable

friends in Covington, Kentucky, who

was being tried in the criminal court

for grand larceny. Cunningham was

involved with Henry Clifford and Mary

Forsha who were charged with

stealing a large lot of dry goods in

Covington, Kentucky. Cunningham

had received the goods, knowing them to

have been stolen. "There was

really no defense to be made [for him].

. . . I endeavored to make a sen-

sible, energetic little speech in his

behalf. He was convicted, but the prose-

cuting attorney paid me some handsome

compliments as did also the

18 OHIO HISTORY

Court."59 Cunningham was

sentenced to serve three years in prison. The

other two, Henry Clifford and Mary

Forsha, received sentences of five

and three years respectively.60

At the close of his plea for Samuel

Cunningham, Judge Robert B. War-

den of the Common Pleas Court, appointed

Hayes to assist in the defense

of Nancy Farrer, a poisoner of two

families. Hayes recognized immediately

the magnitude of the opportunity being

offered to him. "It is the criminal

case of the term. Will attract more

notice than any other, and if I am well

prepared, will give me a better

opportunity to exert and exhibit whatever

pith there is in me than any case I ever

appeared in. The poor girl is

homely--very; probably from this

misfortune has grown her malignity. I

shall repeat some of my favorite notions

as to the effect of original consti-

tution, early training, and associations

in forming character--show how it

diminishes responsibility, etc. . . .

Study medical jurisprudence as to

poisons; also read some good speeches or

poetry to elevate my style, lang-

uage, thoughts, etc., etc. Here is the

tide, and I mean to take it at the flood--

if I can. So mote it be!"61

Not only was it the criminal case

of the term, as he said; it was to be

for him no doubt the most

important case of his law career.

Nancy Farrer62 was homely

indeed, almost repulsively so. She had been

born in Fannington, Lancashire, England,

on July 24, 1832. When she

was about ten years of age, her father

with another child, a son younger

than Nancy, emigrated to America, and

Nancy with her mother followed

about two years later. Some years prior

to leaving England, her mother

had become a Mormon and Nancy was said

also to have joined the church.

After his arrival in Cincinnati, her

father, too, joined the church, and the

family was said to have lived in Nauvoo

about two years. Nancy's mother

considered herself to be a prophetess,

imagining that she was the wife of

the Saviour and the mother of all living

things. The father was a shoe-

maker, and seemed to have possessed

ordinary intelligence, but he took

up drinking and became alcoholic. He tried

suicide twice, once by jump-

ing into the Ohio River and again by

cutting his throat. He finally died of

drunkenness in the Commercial Hospital

of Cincinnati in 1847.

Somehow Nancy had gone to school and had

learned to read a little.

She could enjoy reading her hymn book

and newspapers and other light

literature. However, she did not appear

to know how to write, for she

made a mark when asked to sign the

indictment charging her with murder.

In July 1851, Nancy began living with

Mrs. Mary Ann Green, who was

recovering from childbirth. Mrs. Green's

husband went off on a trip

shortly thereafter, leaving his wife in

possession of a considerable sum of

money. In a short time, a friend of the

family, John R. Marks, called upon

Mrs. Green; and thinking Nancy not

sufficiently intelligent to discharge

the duties of a nurse, he employed a

Mrs. Anna Bazley63 to assist her.

Soon, Mrs. Green was attacked with

severe vomiting. Ice water which had

been prescribed for the purpose of settling

her stomach, seemed rather to

irritate it. In October 1851, she died,

the baby having died earlier.

|

RUTHERFORD B. HAYES, Attorney at Law 19 A young woman living next door overheard the two nurses in conver- sation about the time that Mrs. Green became severely ill. One of them was heard to say, "It's under the bolster, you can easily take it." Later, Mrs. Bazley was heard to say, "Well, Nancy . . . you know more about it [the illness] than the doctors." The answer: "I expect I do." Soon after the death of Mrs. Green, Mrs. Bazley disappeared.64 About three weeks later, Miss Farrer went to live with Elisha Forrest and his family, who resided on High Street, near Collard. She had had no previous acquaintance with these people. The family included Mr. Forrest, his wife, Cassandra, who was an invalid, and three children, John Edward, Billy, and James Wesley. In the first meal prepared by Nancy for her, Mrs. Forrest was suddenly seized with a violent illness, supposed at the time to be cholera morbus. She died in the course of five or six hours. Soon after, |

|

|

|

Mr. Forrest's children were taken sick with a similar illness, and one, John E., about eight years old, died in less than an hour. On Wednesday, De- cember 1, 1851, the remaining members of the family were stricken with illness as on the two previous occasions, while taking dinner; and before night, James Wesley, about two years old, died. Physicians who were called inferred from the symptoms that death was due to poison. A postmortem examination was made on the body of the child and a quantity of arsenic was found in the stomach. Later, arsenic would be found to have caused the deaths of Mrs. Forrest and the older son, John, as well as Mrs. Green. Suspicion was then focused upon Nancy Farrer, who had suffered no illness at any time.65 On December 4, 1851, Elisha Forrest appeared at the mayor's office and made affidavit charging the girl with causing the death of his youngest |

20 OHIO HISTORY

child by means of arsenic.66 Nancy

was arraigned on December 8, 1851,

and tried in the Mayor's Court. Among

the witnesses examined were the

husband and father Elisha Forrest, Dr.

A. S. Dandridge, Drs. W. and T.

Salter of Salter's Drug Store, Dr.

William Carson, and Dr. Schurts. The

latter had attended Mrs. Green and Mr.

Forrest's children during their

sicknesses. Dr. Dandridge performed the

postmortem examination, and

an analysis of the stomach of the child

had been made by Dr. T. Salter,

apothecary.67

As the case was picked up by the

newspapers, much excitement was cre-

ated. In the preliminary trial before

the mayor, Nancy Farrer was repre-

sented by Messrs. John F. Hoy and Israel

Garrard; and Andrew J. Pruden,

Prosecuting Attorney for Hamilton

County, represented the State. "The

testimony . . . is unfavorable to the

accused," a correspondent for the Cin-

cinnati Enquirer noted. "There

is something very mysterious to the whole

matter."68 Nancy was

committed to jail to await trial in the Court of Com-

mon Pleas of Hamilton County.

On January 10, 1852, the grand jury

reported a bill of two indictments

against Nancy, and on January 15 she was

arraigned in the Common Pleas

Court on two additional indictments for

poisoning, charging her with the

murder by poisoning of four persons,

James Wesley Forrest, Mrs. Cas-

sandra Forrest, John Edward Forrest, and

Mrs. Mary A. Green. However,

she was to be tried in the Common Pleas

Court only for the murder of

James Wesley Forest, who died on

December 1, 1851.69

The Nancy Farrer case came before Judge

A. W. G. Carter on Wednes-

day, February 18, 1852, with Andrew J.

Pruden, Prosecuting Attorney for

the County, and P. McGroaty for the

State; and John F. Hoy and R. B.

Hayes, who had been appointed to assist

Hoy, for the defendant. Witnesses

in this trial were Elisha Forrest, for

the State, who related the circum-

stances leading up to the death of his wife

and two children; William

Salter, druggist, 60 Broadway; Edward

Seandlier, druggist, in Fulton; and

George W. Landrum, druggist, corner of

Congress and Butler, all swear-

ing that they had sold arsenic to Nancy;

and Dr. H. C. Bone and Dr. S. L.

Green testifying that they had seen

Nancy buying arsenic at two of the

drug stores.70

Dr. J. R. Buchanan, teacher of the

science of medicine, philosophy and

"particularly of the brain,"

testified as to Nancy's sanity--that "the general

tone and temperament of her brain would

favor imbecility. . . . She was

rather a subject for compassion than for

punishment."71

The testimony was concluded on Saturday,

February 28, 1852, and Judge

Carter gave his charge to the jury:

"The State claims that Nancy Farrer

did commit the crime as charged by the

Grand Jury, and is therefore guilty.

The defense claims that the facts

testified to in the case are of too uncer-

tain nature; that the evidence is but

circumstantial, and points with equal

or more force to some one else as the

perpetrator of the act, and that if

the facts should produce the conclusion

upon the minds of the jury that

the act was done by Nancy Farrer, even

then, says the defense, she is not

RUTHERFORD B. HAYES, Attorney at

Law 21

guilty as charged, because she was and

is not a responsible being--that she

did the act through imbecility--from

insanity."72

The jury retired to consider the case on

Saturday afternoon about 3:00

P.M. After being out two nights and all

of Sunday, they came into court the

following Monday at about ten o'clock

and sought further instructions

upon the question of imbecility. They then

retired, and remained in session

until about 6 o'clock, Tuesday

afternoon, March 2, bringing in a verdict

of guilty of murder in the first

degree.73

Before sentencing Nancy, Judge Carter

tried her accomplice, Mrs. Anna

Bazley, who had been found and indicted

with the girl for murder of Mrs.

Mary Ann Green by poisoning.74 Before

Mrs. Bazley's trial, Nancy had

been quite confidential with her young

counsel, Hayes. She had told him,

"I did not poison Mrs. Green; she

did it; she showed me how to do it.

She taught me." "Will you

swear to this, Nancy?" asked Hayes. "I will, for

it is God's truth." But on the

witness stand, when questioned, she com-

pletely exhonorated Mrs. Bazley of all

knowledge of the presence of arsenic

in the water drank by Mrs. Green. The

jury, without retiring from the box,

returned a verdict of not guilty. When

Hayes asked her after the trial

why she had lied to him, she said,

"Oh, well, one woman is enough to hang

for murder, and I didn't mean to hang

Mrs. Bazley."75

Hayes spent two days before the Court

arguing for a new trial for Nancy,

but his motion was overruled. Judge

Carter then proceeded to pronounce

the sentence of the Court: Nancy Farrer,

"to be conveyed from this place

to the jail of Hamilton County, thence

to be conveyed to the place of exe-

cution in the yard of said jail, and

then between the hours of eleven o'clock

in tle morning and one in the afternoon,

be hanged by the neck until

dead."76

Thereupon, Hayes appealed to the

District Court, which met on April

21, 1852, for a new trial, basing his

appeal upon a writ of error, enumerat-

ing six points of error. He applied,

too, to the Court to have the sentence

suspended until after the meeting of the

Supreme Court of Ohio at Colum-

bus, so that an appeal might be made to

that body upon a writ of error.

This motion was granted.77

On learning of Nancy Farrer's sentence,

Hayes's mother sent word to

him: "If the Governor pardons her

it will be because she is a woman. Is

not that degrading to the female sex? .

. . I should like to know a good

reason why a woman should be acquitted

when the same crime would con-

demn a man. They are as capable of

knowing right and wrong as any man.

They have no more temptation to sin than

men, and they should be as

severely punished, for an example to

others. Women ought to be better

than men; they have too powerful an

influence over mankind to be allowed

to be worse."78

At the December 1853 term, the Ohio

Supreme Court heard Hayes's

argument for a new trial for Miss

Farrer. Opposing argument was pre-

sented by George E. Pugh, Attorney

General. After reviewing the case in

its entirety, three of the justices

ruled for a new trial--Justices John A.

22 OHIO HISTORY

Corwin, Allen G. Thurman, and Rufus P.

Ranny; but Chief Justice

Thomas W. Bartley did not concur. The

judgment of the Common Pleas

Court was reversed, and a new trial

ordered.79

The next step for Hayes was to argue the

case before Judge John B.

Warren in the Probate Court on an

inquest of lunacy, in December 1854.

Hearing the case as jurors were John M.

Miller, W. F. Brackett, Richard

P. Spader, Noble Veazy, Samuel Johnston,

Benjamin Urmston, John T.

Snodgrass, David Lemmon, Edward Boyle,

Jared Cloud, John Huff, and

Ara Banning, three of whom resided in

the city. The jury deliberated over

night, arriving at a verdict the next

morning at 10:30. They found Nancy

Farrer of unsound mind.80

"I succeeded in finally getting an

acquittal of my first life case which

has been a pet case so long and to which

I owe so much," Hayes sent word

to his Kenyon classmate, Guy M. Bryan,

of Texas.81

The trial verdict in the Probate Court

was referred to Judge James

Parker of the Common Pleas Court, who

issued an order for the sheriff

to "deliver Nancy Farrer into the

custody of such officer as may be required

by the order of the said Probate

Court." Nancy was taken to the Lick Run

Asylum and afterwards was transferred to

Longview.82

Later, Judge Carter recalled having seen

Nancy in the neighborhood of

Lick Run Asylum and he stopped to talk

with her:

"Hello, Judge, how are you? I'm

glad to see you. Well, you didn't

hang me after all?"

He could not help smiling at the

salutation and nonchalant manner

of Nancy. "Oh, no, Nancy, I should

hate terribly to be the means of

hanging a woman, no matter how much she

deserved it. But what are

you doing here? . . ."

"Well, I'm one of the keepers at

the Asylum; I takes out the patients

and airs them. See, yonder, my

pets," [and she pointed to a group of

poor imbeciles in the woods adjoining,

some of whom were singing

songs, some culling flowers, some lying

down on the green grass, and

others suspiciously walking about.] . .

.

"Yes," said Nancy, "these

are my pets; I take care of 'em."

One day Nancy went out and her memory

failed her; that is, she

forgot to return, and . . . to this day

no one knows where she went.83

In summing up what he had earned with

his work on the Nancy Farrer

case, Hayes found that he had won

acclaim and recognition as a capable

lawyer; seventy-five dollars from the

Common Pleas Court as fee; and a

box, delivered to his office one morning

in July 1852, containing "two very

nice neck chokers [ties], blue as the

sky, and around them a nest of Mor-

mon prose and poetry . . . independent

of every connexion except paste,"

sent by Nancy's mother.84

In September 1852, there were three

prisoners in the Hamilton County

jail under sentence of death--Nancy

Farrer, James Summons and Henry

Lecount-and the defense attorney for all

three was young Rutherford B.

Hayes who, the previous year, was hardly

known at all in Cincinnati. He

had suddenly emerged into the limelight

of publicity.85

RUTHERFORD B. HAYES, Attorney at

Law 23

The Court asked Hayes to assist Colonel

F. T. Chambers in the defense

of James Summons in the District Court

before Presiding Judge Allen G.

Thurman and Judges Stanley Matthews and

Donn Piatt. The case was a

notorious one, having been tried several

times and would be tried several

times more. In July 1849, James Summons

had been arraigned upon two

indictments of murder in the first

degree, poisoning by arsenic the tea

which his parents--his father was a

river captain--and other relatives drank

at supper, killing two of them: Mrs.

Electa Reeves and Henry Armstrong.

His parents survived. At the time, the

captain's family consisted of him-

self, his wife, their two sons, William

and James; a daughter and son-in-

law, Henry Armstrong; a grandson, Paul

Huston; Mrs. Electa Reeves;

and a servant girl, Mary Clinch. At his

trial, the chief witness against him

was the servant girl; it was conceded

that without her testimony, no con-

viction could have been had.86

The prisoner's trial in the Supreme

Court of Hamilton County in May

1850, which extended through seven days,

resulted in a mistrial--the jury

could not agree on a verdict. Summons

was tried a second time late in May

1850, before another jury in the same

court, and on June 1, 1850, after

ten days of examination, the jury again

failed to agree. The servant girl,

Mary Clinch, again appeared and

testified against him. A third trial was

held about a year later. In the

meantime, on August 11, 1850, the prose-

cution witness, Mary Clinch, had died.

In this trial her testimony was sup-

plied by a witness, Thomas A. Logan, who

was a student and law clerk

of Judge Timothy A. Walker, counsel for

the State in the trial. Logan

undertook to give Mary Clinch's

testimony from memory, aided by notes

he had taken at the former trials.

Again, the jury disagreed and was dis-

charged--a mistrial. Hayes was present

at all the trials, and was impressed

by the prosecution's handling of the

case.87

The fourth trial started on April 22,

1852, and was conducted in the

District Court, before Judge Allen G.

Thurman, presiding, and Judges

Stanley Matthews and Donn Piatt. At this

point in the proceedings, Hayes

entered the case to assist the defense

counsel, F. T. Chambers, having "con-

ducted the Nancy Farrer case with

ability." He was appointed by the Court.

Summons' first defense counsel, Judge

Nathaniel Read, had carried a

bond appeal for him to the United States

Supreme Court, but had lost.88

Hayes was given a chance to address the

jury in Summons' defense, which

he did on April 27.89 The following day

the jury retired to consider the

case, and returned the next morning with

a verdict of guilty of murder in

the first degree of Mrs. Electa Reeves.90

The motion for a new trial was decided

on Friday afternoon, April 30,

and the Court denied the trial.91 Sentencing

took place on Saturday morn-

ing, May 1, before a large crowd. Judge

Thurman asked the prisoner if

he had anything to say. "I am not

guilty. I am satisfied that if all my wit-

nesses were here, I could have changed

the verdict of the Jury. I beg mercy

of the Court and ask a new trial."

He was then sentenced to be hanged

on the third day of February 1853,

between the hours of 9:00 A.M. and

4:00 P.M.92

|

24 OHIO HISTORY |

RUTHERFORD B. HAYES, Attorney at

Law 25

Dr. Joseph T. Webb of Cincinnati,

Hayes's brother-in-law, did not think

much of Summons' innocence, and gave

Hayes his unsolicited opinion: "I

do not wish you any harm but I certainly

do not wish you [to] clear Jim

Summons. If there is a wretch unhung on

this Earth, it is your client."93

It was now Hayes's lot to draw up a Bill

of Exceptions and argue for a

new trial. When he went to Columbus to make

the appeal, he was on his

honeymoon, and in a happy frame of mind.

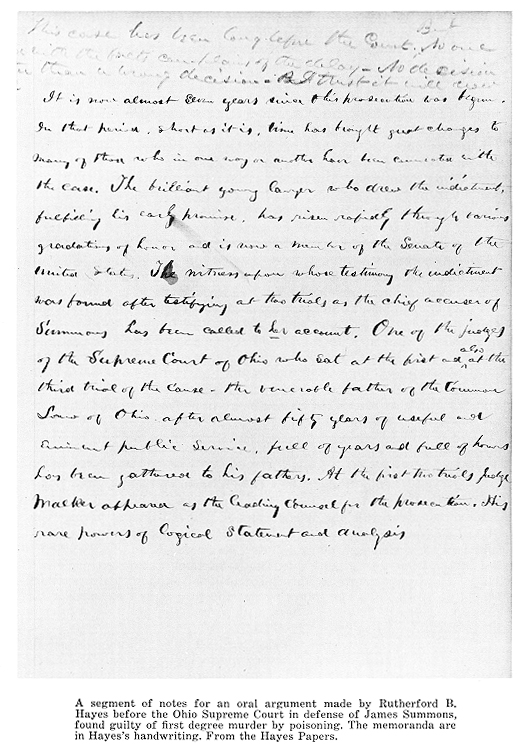

"The greatest triumph of my

professional life, viz, arguing my first

case orally in the Supreme Court of

the State--'State of Ohio v.

James Summons,' "94 he said. To his Uncle

Sardis at Fremont, he wrote: "Got

through with my argument in the Sum-

mons case in a very satisfactory style,

had a large audience of lawyers, was

congratulated by [Thomas] Ewing, Hunter,

[Henry] Stanbery, and 'sich-

like' lawyers."95

The Court was evenly divided in the

opinion, and Hayes argued the

case a second time before the Supreme

Court on a writ of error, in De-

cember 1856. The decision was in favor

of the State of Ohio; only one

justice dissented; and Summons was

scheduled to be executed on April 17,

1857.96

"You know my Summons case was

decided against me," Hayes wrote his

Uncle Sardis. "Judge [Ozias] Bowen

who dissented from the rest of the

Court says that after the argument a

majority was in our favor, but [Thomas

J.] Bartley's obstinancy finally

triumphed. The Governor will I think com-

mute the sentence to imprisonment for

life."97 Governor Salmon P. Chase

did so on March 10, 1857.98

The third murder case that Hayes handled

as defense attorney was that

of Henry Lecount, who fatally assaulted

one William Clinch on May 4,

1852, on the corner of Canal and Vine

Streets, Cincinnati. The attack grew

out of jealousy on the part of Lecount

which was caused by the acknowl-

edged intimacy of Clinch with his wife, and

some testimony given by

Clinch, said by Lecount to have been

false, which had sent the latter to

prison. Clinch was struck upon the head

with a dray pin, cutting a severe

gash from which he died on May 8.

Inquest was held by A. L. Patterson,

Coroner, on May 9,99 and two days later

Lecount had an examination be-

fore the mayor; and on June 7, his trial

began in the Criminal Court be-

fore Judge Jacob Flinn. Hayes and O.

Brown were appointed by the Court

to defend the prisoner who had no means;

and A. J. Pruden appeared for

the State.100

Hayes's pleadings in defense lasted only

two days, the jury returning a

verdict of guilty of murder in the first

degree. Lecount was immediately

sentenced to death by hanging, on

"Friday next, between the hours of

10:00 A.M. and 12 noon." There was

no basis for an appeal for Henry

Lecount. Witnesses had seen him strike

the fatal blow. Governor Reuben

Wood was appealed to for commutation of

the sentence, but he did not

act.101

At the appointed time, on Friday,

November 26, 1852, about 3:00 P.M.,

Henry Lecount was hanged, the first such

execution in Cincinnati in many

26 OHIO HISTORY

years. Hayes was present as a witness.

"I regarded it my duty to be present

at his execution," he noted on the

pass which the Court had given him.

"He seems hardly conscious of what

was passing. It was a shocking sight,

. . . no doubt legally right."102

These were the only murder cases handled

by Hayes as an attorney at

law, two of which he argued in the Ohio

Supreme Court. Later, he was to

argue other cases--civil cases--before

the Supreme Court, either independ-

ently or as a member of a law firm.

While enroute to Columbus to represent

one of his cases before the

Ohio Supreme Court, Hayes told his wife

about an incident which hap-

pened to him on the train:

Had an adventure and scene on the cars

in which I figured "some."

At the town before Charleston--Selma--a

constable came aboard with

a Warrant for our Conductor, Mr. Osgood,

for stealing a boy's hat. It

seems he had taken a boy's hat from his

head for not paying fare. Judge

[John A.] Corwin [on the train] referred

the conductor to me for legal

advice. I tried to induce the constable

to take security money, watches,

or what not, that Osgood would appear at

Charleston on Monday to

answer the charge; but the constable

"knew his duty," "must have the

body," &c., &c., and so

keep Mr. O. in the jug over Sunday. I then ex-

amined his warrant: found it was very

defective; accordingly advised

the conductor that he had a right to

resist the arrest. On reaching

Charleston, a large number of the

passengers crowded to each door

(officer Bruen at the head) and kept Mr.

Constable from taking Mr. 0.

out of the car. In the mean while a mob

of (a great crowd) rowdies

in waiting at Charleston, tried to break

into the cars and rescue their

man and capture ours, but they were

knocked and pushed off until

the whistle sounded and on we shoved

amid all sorts of imprecations

and threats. It was now our turn. I told

the conductor he had a right

to demand fare, and if refused to put

the Constable off between

stations.

The official melted rapidly into an

ordinary human being. "Didn't

wish to make trouble"; "Would

have offended all his neighbors if

he hadn't attempted to serve the

warrant," &c, &c. Finis. [We] let him

off at London and promised that Osgood

would stop over on Mon-

day.103

On the day after Christmas 1853, Hayes

and his Kenyon College class-

mate and friend, William K. Rogers,

joined the firm of Corwine, Smith

and Holt, succeeding Caleb B. Smith and

R. S. Holt in that firm, to be-

come the firm of Corwine, Hayes &

Rogers. Originally the firm was Spen-

cer, Smith & Corwine; then Smith

& Corwine & Holt. "The new firm,"

Hayes wrote his Uncle Sardis, "is

in this wise: Caleb B. Smith and Mr.

Holt, both fine lawyers, go out of the

practice, and Billy Rogers and my-

self take their places. Smith has done

little or nothing for ten months past,

being President of two R.R. Co's, and

now gives his whole time to that

business. Mr. Holt goes South. Rogers

and myself pay $1,200 to Holt and

Smith for one half of all the business

pending in the office. . . . The pend-

RUTHERFORD B. HAYES, Attorney at

Law 27

ing business . . . is probably, as near

as we can guess it, worth or will pay

us for our share eventually as much as

$1,800. We pay $600 down and the

balance when we can. The profits of the

new business the first year go, 1/2

to Corwine, 1/3 to me, and 1/6 to

Rogers. . . . The work is to be done

chiefly by myself, Rogers, and an

English attorney's clerk [John A. Lynch].

The office has always had good lawyers

in it, and we shall try to keep its

business and standing."104

The next two years found Hayes quite

busy with his firm's affairs, and

with several personal interests,

including the purchase and remodeling of

a home for his family at No. 383 Sixth

Street. He was pleased with the firm.

"The business is large and very

varied. I attend to the litigated business

exclusively," he told his uncle.105

His mother, on a visit at the new home,

wrote a cousin: "I went to

Cincinnati in November, 1854, spent ten weeks

very pleasantly with my son's family.

Week days I saw him only at his

meals; he was busy at the court house or

his Office all the time."l06 To

her brother, she said "We only see

him at his meals; he is constantly busy;

has no time for letter writing. . . .

Rutherford has not time to provide

any thing but money for his family. It

is a good thing that Lucy has broth-

ers to pay some attention to her and her

friends; her husband is so much

engaged."107

In March 1855, Hayes was associated with

Salmon P. Chase and Timothy

Walker in a case being tried under the

Fugitive Slave law. A slave girl

named Rosetta Armstrong had been

entrusted by her master, Rev. Henry

M. Dennison of Louisville, Kentucky, to

a friend to be taken to Richmond,

Virginia. On the way, the friend went by

way of Ohio through Columbus,

where he and Rosetta were detained. In

Columbus, Rosetta was brought

before the Probate Court on a writ of habeas

corpus and was adjudged to

be free. The Court appointed Lewis G.

Van Slyke as her guardian. Mean-

while, Mr. Dennison appeared and had a

talk with Rosetta. He gave her

a choice of returning with him, or being

set free. She chose the latter.

Whereupon, Dennison obtained a warrant

for her arrest from United

States Commissioner John L. Pendery of

Cincinnati, where she was brought

by the marshal. Her guardian obtained a

writ of habeas corpus from Judge

James Parker of the Court of Common

Pleas of Hamilton County, and af-

ter arguments by Messrs. Chase, Walker,

and Hayes for Rosetta, and Messrs.

Pugh and Flinn for Mr. Dennison, she was

set free. Thereafter, she was

immediately re-arrested on the warrant

issued by Commissioner Pendery,

who now heard argument on the whole

question. Popular sentiment ran

high and the courtroom was filled. In

this instance, the chief legal argu-

ment was made by Hayes, who Mr. Chase

said, "acquitted himself with

great distinction."108

A correspondent of the Columbus Columbian

commented on the case:

Mr. Van Slyke speaks in enthusiastic

terms of the masterly effort

of R. B. Hayes, Esq., the chief counsel

for Rosetta before the Commis-

sioner. Mr. Hayes is a young man, and

was formerly a resident of our

city, where he has relatives residing.

He was recommended to Mr. Van

28 OHIO HISTORY

Slyke by a friend who appreciated his

clear head and good heart, hid,

in a measure, from public observation,

by retiring manners and modest

demeanor. Mr. V. found at once that

"his heart was in the right place,"

and had good reason to rejoice that he

had fallen in his way. To his

eloquent and masterly closing speech

before the Commissioner, he

thinks it very likely Rosetta is

indebted, mainly, for the allowance of

her freedom under U. S. Law. The

appreciation of it by the great aud-

ience in attendance, was manifest from

their breathless silence during

its delivery, their unrestrainable

applause at its close, and the congrat-

ulations which the young orator received

from a large number of his

brethren of the bar, at the close of his

effort.109

It would follow that Hayes would be

active with fugitive slave matters,

and, recalling later, "My services

were always freely given to the slave and

his friends, in all cases arising under

the Fugitive Slave Law from the time

of its passage." Such in fact was

true.110

William K. Rogers' health was poor, and

in 1856 he left the law firm

for Minnesota. Thinking to be away only

a few months, he failed to re-

turn at all. For a while his partners

retained his name and kept him in-

tormed of cases handled, but finally he

was dropped and the firm con-

tinued as Corwine & Hayes.

The senior partner, Richard M. Corwine,

had been active with outside

interests including railroads, politics

and others; and more and more, Hayes

found himself also drawn into political

activities. By 1856 he was actively

involved and campaigned enthusiastically

for John C. Fremont, and in

1858 was strongly identified with the

activities of the Republicans. His ef-

forts in politics caused him to consider

becoming a practicing politician

himself. The opportunity was presented

when the City Solicitor of Cncin-

nati, Samuel Hart, died. The city

council met on December 9, 1858, at

7:00 P.M. to elect a successor after

conducting the regular business of the

evening.111 Considerable interest in the

vacancy was evident, and the

strongest candidate was Caleb B. Smith,

who was later to be in President

Abraham Lincoln's Cabinet.

There were seventeen wards in the city,

each ward being represented by

two councilmen. Number of votes required

to elect was a simple major-

ity, or eighteen votes. The councilmen

present that evening were Messrs.

Baum, Bates, Benjamin Eggleston, F.

Hassaurek, G. W. Hollister, Pearce,

William Perry, A. Tafel, Thomas H.

Weasner, and Wisnewski, Republi-

cans; Messrs. Davis, Theophilus Gaines,

Hambleton, Higbee, Joseph S.

Ross, Runyan, R. M. Bishop and Theodore

Marsh, Americans [Know-

Nothings]; Messrs. T. M. Bodley, J. H.

F. Groene, Daniel Hannon, John

Hawkins, Samuel Hirst, F. Maurer, G. L.

Myers, J. M. Noble, Henry Put-

hoff, Charles Rule, Schaeffer, and

Dennis J. Toohey, Democrats; and

Messrs. John F. Torrence and Hezekiah

Keirsted, Independents. Absent

were: Skaats, Republican, and Green,

American.

The Council did not get around to

balloting until 9:30 P.M. The aud-

ience was rather large and interested.

The first ballot showed the initial

strength of the candidates, with this

result:

RUTHERFORD B.

HAYES, Attorney at Law 29

Caleb B.

Smith

..............................13

William Disney ...................................12

R. B.

Hayes

.................................3

Thomas C.

Ware

...............................1

Washington

Van Hamm

...............................1

Little or no

change occurred on the second balloting. The third ballot

showed Disney

losing ground, Smith holding steady.

Caleb B.

Smith ...............................

13

----- Forrest ..................................8

William

Disney ..................................4

R. B. Hayes ..................................4

Thomas C.

Ware ..................................2

Blank

........................................1

On the fourth

ballot there was a decided shift which continued to hold

through the

sixth ballot:

R. B.

Hayes

...............................14

Thomas C.

Ware ...............................11

Caleb B.

Smith .................................4

William

Disney ...................................2

The seventh

balloting brought fourth the following results:

R. B.

Hayes

...............................17

Thomas C.

Ware ...............................12

William Disney ..................................3

An analysis

of the balloting on this ballot showed that Hayes received

the following

votes--Republicans (10): Messrs. Baum, Bates, Eggleston,

Hassaurek,