Ohio History Journal

|

|

|

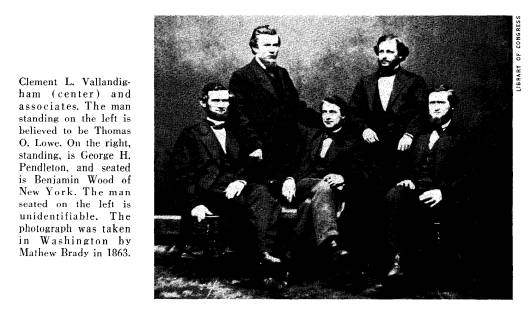

PICTURE OF A YOUNG COPPERHEAD by CARL M. BECKER As he pursued his contentious course during the Civil War, the great Copperhead, Clement Laird Vallandigham, drew around himself in Dayton, Ohio, a circle of political supporters and personal admirers. Local politicians and newspaper editors followed in his wake, and nameless men identified themselves as votaries of "Val." These supporters often embraced Copper- headism out of conviction, but no doubt the strength and firmness of their faith were tinctured by the magnetic appeal of Vallandigham. Among the youngest of these faithful was Thomas Owen Lowe, whose Copperhead beliefs, though owing nothing in their origin to Vallandigham, found their fruition in the Vallandigham light. Well-known among the Vallandigham coterie and one of its most persistent spokesmen in Dayton, Lowe has re- ceived little attention from scholars. Yet, in many respects, his words and deeds reveal in detail a Copperhead in a typically aggressive posture. Born in 1838 in Batavia, the county seat of Clermont County, Ohio, young Lowe on the eve of the Civil War had already felt in some degree the way of the world. His father, John William Lowe, had come to Batavia in 1833 from New Jersey.1 After studying law in the office of the eminent congressman Thomas Hamer, he opened his own office; his clients were few, though he could boast a relationship with one of the county's leading at- torneys, Owen T. Fishback,2 whose daughter, Manorah, Lowe married in NOTES ARE ON PAGES 76-78 |

4 OHIO HISTORY

1837. Shortly after the Mexican War

began, at the personal request of

Ulysses S. Grant, who was then a

lieutenant with the army at Matamoras

and whom Lowe had known well before his

appointment to West Point in

1839,3 the lawyer took a captain's

commission with the Second Ohio In-

fantry, left his family, and sailed for

Mexico. There his service was honor-

able but routine, and, on his return to

Batavia within a year after his

departure, he again took up his legal

practice.

Looking to the intellectual nourishment

of his son, he sent the lad to

Farmers' College near Cincinnati in

1851. Then in its heydey but only

ostensibly an agricultural college,

Farmers', through its emphasis on student

debates on all manner of moral and

political issues, formalized in the youth

the spirit of controversy he had first

acquired at home.4 Compensating for

a constant round of schoolboy pranks and

social activities with some intense

study of Livy and other ancients, the

lad achieved a good academic record

but left the college in 1854 without a

diploma because of his father's

financial stringency.5

In the meantime, his father had moved to

Dayton, where the son joined

him after a brief stay in Cincinnati,

but he soon hastened to Nashville,

Tennessee, to take employment as a clerk

with the W. B. Shepherd banking

firm. Remaining but a few months in

Nashville, he next went to Lebanon,

Tennessee, again accepting a position as

a bank clerk, this time with the

Bank of Middle Tennessee.6 The callow,

impulsive youth spent about two

years in Nashville and Lebanon, moving

all the while in a rough patrician

society, and when he returned to Dayton

in 1857 his social and political

notions had gravitated, not

surprisingly, to southern ideals: he admired

the stratified class structure he

discerned in Tennessee, believed that slavery

was socially and morally justified, and

asserted that the South was becoming

a political lackey of the North.7

In the years immediately following his

return to Dayton, Tom had little

occasion to reveal his southern complex.

He was employed as a cashier

with the banking firm of Harshman and

Winters and was preparing himself

for the legal profession, gaining

admission to the bar in 1859. In late

1857 he married Martha Harshman, a

daughter of Jonathan Harshman,

one of the proprietors of Harshman and

Winters. Not until the presidential

election of 1860 did he broach his

southern beliefs. In that election he

actively supported John Bell and Edward

Everett, the Constitutional Union

candidates. In a speech never delivered

but committed to his journal under

the title, "A Political Speech for

John Bell and Edward Everett," Tom re-

counted his hostility to the commercial

spirit of the North and its bondage

of the factory worker, justified slavery

by appeals to the Bible, rejected

|

A YOUNG COPPERHEAD 5 |

|

|

|

equalitarian doctrines of the Republicans, subscribed to popular sover- eignty, fulminated against politicians who would sacrifice chattel property of others for demagogic purposes, and inveighed generally against sin and temporization wherever they could be found.8 He argued that the only way to curb the dangerous sectional parties and protect the South, which was surrounded by a cordon of hostile states, was to elect Bell, who would command the respect of all sections and both bodies of congress. Then would secession and fanaticism melt away. The death of his father in September 1861 in the battle of Carnifex Ferry, where he commanded the Twelfth Ohio Volunteer Infantry, relieved Tom of a restraining hand. Prior to Carnifex Ferry, for Tom to have opposed the war or the Lincoln administration would have been to oppose his father. Now he openly clasped the principles of the Peace Democracy and became an impassioned follower of Vallandigham. A wing of the Democratic party, its adherents popularly known as "Copperheads," the Peace Democracy had as its primary objective the securing of peace between North and South.9 Vallandigham, for his part, usually expressed fairly moderate peace views. Briefly, he denied the con- stitutional right of the national government to force its will on the sovereign people of a state, said that compromise was possible if the Lincoln admin- |

6 OHIO HISTORY

istration should be rejected by the

voters, and feared that a northern mili-

tary success would mean the destruction

of states' rights and the beginning

of a military despotism.10

That Tom was gravitating toward

Vallandigham early in the war is evi-

denced by his correspondence with

"Johnnie" Wallace, a resident of Nash-

ville who had once lived in Dayton. In

the summer of 1861 Wallace wrote

to Tom requesting a vignette of

Vallandigham, and Tom readily responded.

Though there was much in Vallandigham

that he disliked, Tom wrote, he

admired him for his perseverance in his

course despite the daily persecu-

tion he faced in Dayton at the hands of

the fanatical Republicans.11 Though

one could hardly in safety speak a word

in his defense in Dayton, the

cowards there never molested

"Val" himself because of the power of his

brave soul, before which they melted

away. When Tom had asked him how

he could tolerate abuse, Vallandigham

answered that he could not help his

convictions and thus deserved no more

praise or blame for his political

beliefs than he did for living. As to

his political future, Vallandigham had

no qualms. If the Union was restored by

compromise, as he hoped it would

be, millions in the South would not

forget him; and if it was dissolved in

the wake of internecine strife, the

North would say that Vallandigham was

not far from wrong in arguing that

northern coercion was futile.12

In addition to delineating the

Vallandigham personality, Tom gave his

own thoughts on the coercive war to

preserve the Union and on the means

for ending hostilities. "I

am," he told Wallace, "in favor of preserving

the Union, if it can be done. If it

can't then I am in favor of the next best

thing, and in my opinion war is not the

second[,] third or thousandth best

thing."13 But his means

to peace were war-like: "If our folks can only

whip yours in the next great battle then

I will look for peace and a recogni-

tion of the Southern Confederacy. To

stop now, would fill your gasconading

fire-eaters so full of vanity and

contempt for Northern prowess, that an-

other war would begin in a very short

time to make them respect us suf-

ficiently to let us live along side them

in peace."14

To his younger brother Will, a

lieutenant with the Nineteenth United

States Infantry, a unit in Brigadier

General Lowell H. Rousseau's First

Brigade of the Army of the Ohio, Tom

also expressed the need for a battle-

field victory as a guarantee of peace:

"With all my hatred for Yankees and

Abolitionists, I can't say I would like

the war to end until Bull Run is

'wiped out.' We must whip the

Southerners now, or we won't be able to

live on the same continent with them

when we do conclude to make peace."15

He insisted that the only justifiable

object of coercion was the restoration

of the Union as it was before the war,

when North and South were united

A YOUNG COPPERHEAD

7

in hearts and hands; but such an object

could never be realized, argued

Tom, by force of arms. The means could

not be subordinate to the ends.

Thus, though he believed the South to

be constitutionally wrong in secession,

he was willing to end the war by

recognizing southern independence.16

His letters to Will, written regularly

throughout the war, were filled with

Copperhead ideas and activities. Though

seldom evoking his brother's

sympathy, Tom persisted in presenting

his point of view to him.

It was also not long before he turned

on the abolitionists. He found his

man in Dr. Thomas E. Thomas, the

minister of the First Presbyterian

Church, where Tom was an active member.

Thomas had a long record of

abolitionism and unceasingly had urged

his anti-slavery views on his con-

gregation. Incensed by his minister's

use of the pulpit, Tom sought his

removal on the ground that he prayed

that "this war may never cease until

this iniquity (slavery) is

destroyed."17 "Whenever you preach aboli-

tionism," he wrote Thomas,

"you give me the greatest pain."18

Since the

constitution did not forbid slavery,

the clergyman was in opposition to the

law of the land just as the

secessionist was, argued Tom, and hence his

religious labors could not be blessed

of God any longer. The deacons of

the church did not agree with Tom, and

Dr. Thomas continued his labors,

whether blessed or not.

But complaints against an abolitionist

minister and counsels for a soldier-

brother could hardly satisfy a young

man on the political make. The bank-

ing business being dull, Tom determined

on the career his father had wanted

for him.19 Declaring the

legal practice to be his predestined profession,

Tom rented an office, began to read his

Blackstone again, and waited for

clients to rush to him. Either because

his practice flourished or because it

languished, he now found time to enter

the political arena.

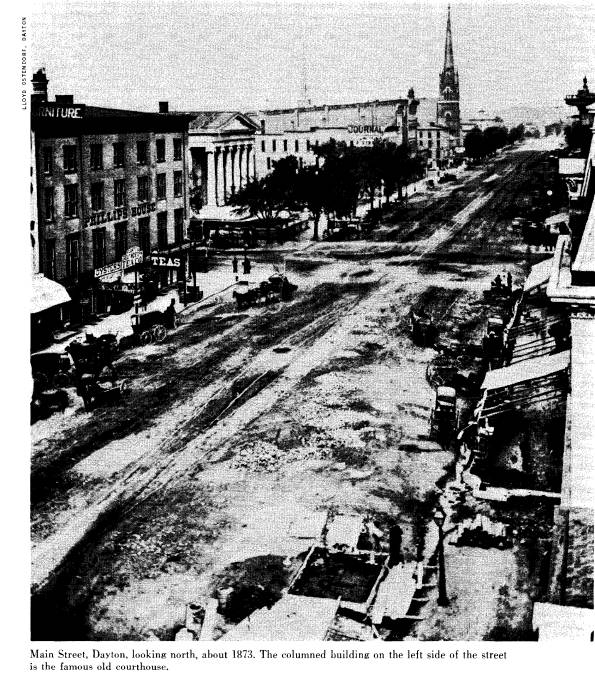

Dayton offered ample opportunities to

politicians to exhibit their abilities.

Throughout the war, relations there

between the Copperheads and the Union

party, a fusion of War Democrats and

Republicans, remained at fever

pitch.20 Generally, the

Copperheads controlled the local offices, but elections

were spirited and close, sometimes

degenerating into physical combat be-

tween rival partisans. The two major

newspapers, the Dayton Daily Empire,

a Copperhead organ, and the Dayton

Daily Journal, a Republican champion,

battled each other without respite,

each finding in trivial incidents evidence

of the perfidy of its opponent.

Officially entering the Democratic

party in June 1862, Tom addressed

the party's county convention the same

month, and that conclave then

elected him its secretary and a

delegate to the coming state convention.21

The Journal was not severely

critical of Tom's maiden speech, as was its

8 OHIO HISTORY

custom with Copperheads, noting that

his sophomoric style was "compli-

mented by his new political

friends."22 Not one to hide his light, Tom

agreed with the Journal, believing,

too, that the speech met with the ap-

proval of party leaders. In it he took

a position of never-ending warfare

against secessionists and

abolitionists, with the army's duty to put down

the former, the Copperheads' the

latter.23 It was the familiar Copperhead

cry, "Bullets for Secesh South,

ballots for abolitionists North." A few days

after the county session, he attended

the Democratic state convention, which

was dominated by Vallandigham and other

Copperheads. Its platform, a

copy of which Tom sent to Will,

denounced the abolitionists as a disruptive

force that hindered the war effort

through their defamation of Union gen-

erals and attacks on whatever

conservative policies Lincoln proposed: it at-

tacked the various congressional

projects for confiscation and emancipa-

tion of slaves as feeding the spirit of

rebellion in the South; and it gave

particular attention to alleged

violations of constitutional rights by the

administration, having in mind the

recent arrest and confinement without

trial of a number of Ohio citizens who

were charged with encouraging

resistance to the draft.24 With

these words at hand, Tom stood ready to lend

his oratorical aid in the fall campaign

in Ohio for state and congressional

offices. One candidate for Tom's third

congressional district was the in-

cumbent, Vallandigham; his opponent was

Brigadier General Robert C.

Schenck.

In the meantime, supported financially

by his father-in-law, Tom secured

a $20,000 government contract for

supplying horses to the army.25 "This

is one way," he wrote to Will,

"I have exhibited my patriotism." And his

political critics might have said the

only way. For he snapped up an offer

of one Henry Keller to enroll as his

substitute for the draft which was

threatened if Ohio did not meet its

quota of volunteers. He offered Will a

justification for his civilian status:

"So far . . . I am the only 'Democrat' . . .

to shirk from his duty to his country.

I hold any man excusable who has

given his Father and only brother and

has Mother, Sister, wife & child

depending on him as I have, but the

majority of these cowardly republican

skunks have no better pretext than that

their business will suffer if they

leave it."26 Yet a few weeks later he was seeking an appointment as

a

major or quartermaster with a new

regiment being raised in Dayton, finally

rejecting an offer of a

sergeant-major's stripes.27 It was quite important,

he remarked, that he remain in Dayton

to help maintain the Copperhead

party organization in order to curb the

excesses of the administration.

In August 1862 Tom began a flurry of

speeches on behalf of the

Peace Democracy and Vallandigham.

Coming under his lash as the

A YOUNG COPPERHEAD

9

wicked agitators who caused and

prolonged the war were, of course, the

abolitionists. Although the South was

guilty of rising against a just, bene-

ficent government, the abolitionists,

charged Tom, had prepared minds in

the North for a fanatical war against

slavery, an institution sanctioned by

the Bible, and had driven the southern

states from the Union for fear of

deprivation of their citizens' property

by a party, president, and reorganized

supreme court dominated by

abolitionists.28 After precipitating the war,

the abolitionists had divided the North

and strengthened the spirit of the

South by trying to use the struggle as a

crusade for the freedom of the

Negro rather than for the preservation

of the Union; indeed congress was

more concerned, lamented Tom, with bills

to confiscate and emancipate

than it was with tax measures to

prosecute the war. Even the purpose of

preservation was senseless, though, as a

union of hearts and hands could

not be achieved by coercion.29

Summoning the lessons of history, Tom

indicted the abolitionists as the

modern-day Jacobins in their suppression

of constitutional rights. The

Lincoln administration had arrested men

without warrants, imprisoned

them without examination, and suspended

the writ of habeas corpus on

the ground that military necessity knew

no law--a theory that would justify

the damnable acts of Charles I, Louis

XVI, and Philip II. It had become

a crime, he insisted, to remain

reasonable; all opposition was now curbed

by the latter-day Jacobins, whose

prototypes at least listed the acts for which

the people could be arrested.30 If

anyone doubted the validity of this esti-

mate, said Tom, let him simply write to

the nation's capital alleging that

Lowe had uttered treasonable sentiments;

then would Lowe be swept away

without trial to be punished only

because he was a Copperhead. Merely to

identify one's self as a Copperhead was

to risk "durance vile."

As for securing peace, it was both

necessary and possible. Internecine war

could not restore the blessed union of

hearts and hands, and it would be

better to recognize the independence of

the South than to hold her by bayo-

nets. War for the purpose of

emancipation was palpably contrary to all

law. It was ridiculous, too, considering

the strength of the North, for the

North to fear future aggression by an

unpunished and unrepentant South.

Thus, since there was no justifiable object

for which the war was being

fought, the Copperheads could not

cooperate with the Lincoln administration.

What kind of peace program could the

Copperheads offer? In one speech.

"Peace," Tom proposed an

immediate cessation of hostilities followed by

a negotiated peace.31 In another, he

said the war must be continued but not

hopelessly and only to the point where

the South would see the impossibility

of winning independence and the

desirability of union.32 Once a cessation

10 OHIO HISTORY

of hostilities was effected, congress

should call a national convention, where

the peace men of North and South might

come to an agreement similar to the

Crittenden compromise.33 Restoration

of the Union as a first condition for

settlement of North-South differences

had no place in his plan. If the peace

men used Crittenden's proposals as a

guide in their deliberations, the South

would be reconciled, the Union would be

preserved as the founding fathers

fashioned it, and the constitution would

become, once again, the law of the

land. These counsels of perfection could

be realized, so Tom believed, only

through the election of Copperheads to

congress, and they had no more

valiant man than Vallandigham. Through

the ballot the peace elements in

both sections could unite to suppress

abolitionists and fire-eaters wherever

they might be!

In addition to making political speeches

in the campaign of 1862, Tom

engaged in a public controversy

involving the Empire, the Clermont Sun, and

the Clermont Courier. Angered by

an uncle--perhaps either John or William

Fishback, sons of Owen Fishback--who had

evidently questioned the sin-

cerity of his political views in some

public way, Tom retaliated with a

communication to the Empire entitled

"An Apostate's Vindication" and

signed "Nephew."34 Denying

his ability to change his convictions, Tom

reiterated his contention that slavery

was not an evil warranting suppressive

legislative measures and that war could

not achieve substantive restoration

of the Union. In response to the uncle's

implication that he was willing to

see the nation rent in two, Tom could

argue that the government had the

right to meet secession with arms. Did

he not have as much interest in

preserving the Union as did his uncle?

After all, he had lost one near and

dear in its defense. The Clermont

Sun, a Democratic organ in Batavia, re-

printed the article,35 and the

opposition newspaper, the Clermont Courier,

rebutted Tom's arguments and barbed him

with the accusation of having

thrust private griefs on the community.36

In his retort to the Courier, Tom

denied this imputation, asserting that

his original letter to the Empire was

published anonymously, thus making the

private grief criticism unjust.37

Tom also labored throughout the

controversy to demonstrate his independ-

ence of Vallandigham. Vallandigham's

opinions on the ethical aspects of

slavery were unknown to him, he

insisted, as he cited his inbred slavery

views.

Even Tom's brothers in religion became

disturbed by his activities,

particularly because he openly played

host to the former pastor of the First

Presbyterian Church in Dayton, James

Brooks of St. Louis. Some suspected

his association with this pro-southerner

was evidence of a conspiracy to

furnish information to the Confederacy.

One member, "Old Charlie Pat-

A YOUNG COPPERHEAD

11

terson," he wrote Will,

"grieved over me . . . and he said he 'could not

understand how a man could be a Democrat

and pray!' Bless his fanatical

old soul!"38

Despite Tom's efforts for Vallandigham

from the stump and in the news-

papers and despite Democratic successes

on the state ticket and in fourteen

of nineteen congressional districts,

Vallandigham lost his seat to Schenck, a

Republican-contrived gerrymander

contributing largely to his defeat.

With the fall elections of 1862 over,

the spirit of bitter political con-

troversy between Republicans and

Copperheads in Dayton did not subside.

Shortly after the election, J. F.

Bollmeyer, co-editor of the Empire, was

shot down by one Henry Brown, a

Republican. The Journal regarded the

murder as simply a personal affair,39

while Tom expressed the Empire's

view with the accusation that the

Republicans had contributed to the act by

constantly labeling Bollmeyer a traitor

whose existence in the community

could not be tolerated.40 For

Tom, this barbarous killing was the "first

dropping of a coming storm which will

destroy every vestige of our

freedom."

Tom's fears did not deter him in his

support of Vallandigham and the

Peace Democracy. Representing a group of

young ladies at a "Butternut"

party in late November 1862, he

presented Vallandigham with a gold-headed

cane. At the ceremony Tom praised the

great man as a model for men who

wished to find an honorable way to end

the war and as a statesman whose

principles time would surely vindicate.41

Political animosities spilled into

social intercourse and into the public

schools. According to Tom, the

Republicans had adopted a ridiculous atti-

tude of social proscription against

Copperheads in their "you shan't slide

on our cellar door anymore"

posture.42 Rows broke out in the high school

among young bucks wearing the badge of

the Union League and those wear-

ing butternut charms. Finally, to

restore peace, the display of all badges

in the high school was forbidden.43

All the while, Tom continued to justify

his position to his brother Will

and to communicate Copperhead views to

the local newspapers. Obviously

under less restraint in his

correspondence with Will than in his political

speeches, Tom urged him to resign from

the objectless slaughter.44 He por-

trayed the administration as an engine

of persecution dedicated to the extir-

pation of political opposition in the

North, citing as evidence the arrest and

confinement of Copperheads without trial

and the suspension of the habeas

corpus privilege by the administration.

Civil insurrection eventually had to

result from such suppression, predicted

Tom. Even now, Dayton, reflecting

the spirit of persecution, had become a

"Natchez under the hill," full of

12 OHIO HISTORY

murder, contemptuous of the law, and

oblivious to the rights of the majority

party there, the Copperheads.45 The

destruction of Samuel Medary's news-

paper in Columbus by a mob of

Republicans was a portent of things to come

in Dayton. But Republican outrages in

Dayton would be met, Tom warned,

by an uprising of Copperheads in

defense of their constitutional rights. If

he believed that the rulers in Washington

wished to establish a monarchy

with the help of the army, as some

said, he would urge the people to "rise

now, while they are busy with the

rebels."46 The army, he

admonished his

brother, must obey only lawful orders

of the president; otherwise it would

be as much an enemy of the constitution

as Jefferson Davis.

If Tom doubted the truth of his own

observations, association with leading

Copperheads convinced him that the

beginning of a ruthless despotism was

imminent. At a meeting of the Peace

Democracy in Hamilton, attended by

Vallandigham, Daniel W. Voorhees, and

George H. Pendleton, among

others, he heard fears expressed about

the loss of free speech and the ballot

box to critics of the administration.47

The offenses of the Republicans were so

heinous, feared Tom, that they

could not permit the Copperheads to

control the national administration lest

the Copperheads would then try the

Republicans in the courts for their un-

constitutional actions. "I expect

them therefore to say this fall as their

political associations are saying now .

. . that no man who is not an

unconditional supporter of the

Administration will be permitted to be a

candidate anywhere in the North."

Even now, Tom reported, the Republicans

were inciting mob violence against

Jeffersonian newspapers in Dayton and

throughout the nation in order to

induce the army to put down men whose

only crime was the refusal to submit to

enslavement. Raging at a state of

affairs in which the minority party of

1862 denounced the majority party

of 1862 as traitors, Tom insisted on

the right of Copperheads to stand on

their constitutional guarantees. If in

order to suppress a rebellion, the ad-

ministration had to destroy human

freedoms, wrote Tom to the Empire, then

let that rebellion succeed before

another one erupted. Was the southern

rebellion so easily quelled that the

Republicans desired a civil cataclysm in

New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania,

Ohio, Indiana, Wisconsin, Kentucky,

and Maryland?48

The month of May saw Tom's fears of

suppression of the Copperheads

and attendant civil revolt nearly

realized in Dayton. There, on May 5, in

the wake of Burnside's celebrated

dead-of-night arrest of Vallandigham, a

wave of mob rioting erupted, in which

Vallandigham supporters put the

Journal building to the torch. Vallandigham felt the military

hand because

he had in a speech delivered at Mt.

Vernon a few days earlier flouted Burn-

|

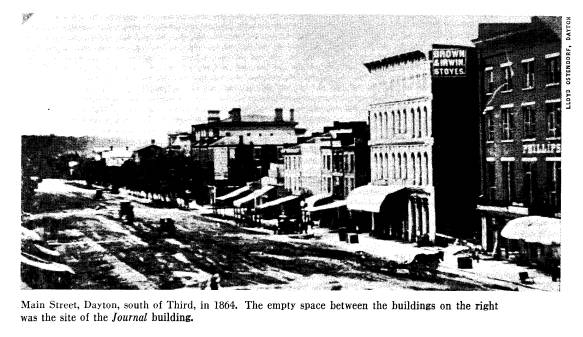

A YOUNG COPPERHEAD 13 side's gag order--General Order No. 38.49 Because of its incendiary com- ment on Vallandigham's arrest and its exhortation to its readers to save their "endangered liberties" through blood and carnage, the Empire bore a heavy responsibility for inciting the populace to violence.50 At least the Journal so believed in accusing the Empire with a cool and deliberate attempt to agitate hot-headed men.51 Tom personally witnessed much of the disorder day and night, and not without some fear of the rebellion he had been espousing. As he described it, crowds of excited men gathered all day after the arrest of Vallandigham. Fearing that his presence might give countenance to acts of violence, he avoided the crowds by remaining in his office all day.52 He slipped home via a back way in the evening, still not sure of the mob's purpose. About 8:00 P.M. the mob began firing guns at the Journal office from in front of the Empire office. Then Tom's disenchantment with rebellion began. As the mob fired on the Journal office, someone threw a turpentine ball on the roof of Tom's house, the flames of the ball igniting the roof and quickly burning through. He could not believe the rage of a mob could be so great that its creatures would destroy friend and foe alike! "Tom Lowe, Tom Lowe, your house is afire," cried the vehement voices. With the help of neighbors he extinguished the fire and removed his family. The mob controlled the city until about 11:00 P.M., when the One Hundred and Seventeenth Ohio Volun- teer Infantry arrived to disperse it after the city police failed to do so. The |

|

|

14 OHIO HISTORY

next day, martial law having been

declared, a number of rioters and the

editor of the Empire were

arrested by the army. Tom found himself in

danger of arrest, too, but was not

alarmed because, so he assured Will, he

had done nothing wrong. He did admit

that the Republicans were denounc-

ing him as an instigator of the rioters;

but he believed they singled him out

for attack because of the absence of

other party leaders, who had gone to

see Vallandigham in Cincinnati, where he

lay in jail.

Perhaps there was more truth than

imagination and puffing in Tom's

belief that he was of sufficient

prominence in his party to merit Republican

strictures. For he was the only

Copperhead to explain publicly and promptly

his personal and his party's views on

the rioting. On May 7 the Journal

published a communication by Tom

entitled "Democracy, not Mobocracy."53

Avowing his party preference and

insisting on the need for political parties

in both peacetime and wartime, he stated

his beliefs about civil uprisings:

When the people are crushed by despotism

and have no other means by

which to secure their just rights, they

have a right--nay, a duty--to revolt;

but the present circumstances did not

justify revolution, although many cruel

and arbitrary acts had been perpetrated

by the administration against its

opposition. The great remedy of the

ballot box remained, said Tom, and as

long as that protection against

enslavement existed, an appeal to arms was

a crime against God and humanity. He

further told his fellow Copperheads

that mobs meant military despotism, as

he eschewed any personal or party

approval of the recent mob action. W. D.

Bickham, the caustic editor of the

Journal, had permitted the use of his columns by Tom only

because publi-

cation of the Empire had been

suspended by the military authorities. Now

he curtly dismissed his article as an

"eleventh hour" repentance which did

not renounce his connection with a party

that was hostile to the government.

Why denounce mob rule when it is a

logical consequence of the teaching of

resistance? asked Bickham.54

Tom wrote the article at the behest of

Colonel Charles Anderson,55 who

said it would demonstrate to the

Republicans that the sober men of the

Peace Democracy disapproved of civil

riot and would show Copperheads

who wanted further incendiary action

that party leaders could not sanction

it. But the Republicans still charged

Tom with inciting the mob. And some

Copperheads now criticized him for

denouncing mobs but for whose presence

all prominent Democrats in Dayton would

have been arrested, while others

said he deserved his present

embarrassment for having communicated with

the hated Journal.56 Perhaps Tom

agreed that the article was a political error

on his part, for one may see in his

scrapbook above a copy of the article a

penciled notation in his handwriting

saying, "great blunder."

A YOUNG COPPERHEAD

15

The next day one contributor to the Journal

accused Tom of justifying

southern secession and countenancing and

perhaps instigating the Dayton

eruption. This attack had to elicit

another contribution from Tom to the

Journal.57 Denying

the right of secession to the South, he went on to record

his activities on the day of violence.

He said that he had been with his sick

wife during the afternoon and evening of

that day. Far from giving his

approbation to the rioters, he would

have appealed to them for forbearance

had he known their purpose. In his

letter to Will describing his movements,

Tom did not mention his wife's sickness

calling him home from the office;

rather he suggested that he was

ensconced in his office during much of the

day. His declarations did not satisfy Journal

readers. One of its contribu-

tors, in an article entitled "Coal

on the Turtle's Back," ridiculed Tom's claim

that he did not know the intent of the

rioters, alleging that they had been at

Tom's door all day and had been supplied

with liquor from the house ad-

joining Tom's.58 A woman's

word was the last heard on the matter. Writing

to the Journal, an unidentified

woman saw no reason to question Tom's

actions and sincerity of opinion on

mobocracy and recommended no further

comment on the issue because she

believed it gave him the notoriety which

he desired.59

Not only was Tom under attack in Dayton.

Now his brother, who usually

did not question his political beliefs

but who was deeply disturbed by events

in Dayton, suggested to Tom that his

political opinions were formed in

prejudice and by association with

persuasive politicians. To this, Tom re-

plied with a virtual political credo.

His convictions, he assured Will, could

not be removed as easily as his hat or

coat, as Will implied in his advice to

him to "set up" as a

"loyal man."60 Never could his motto be ad captandum

vulgus. If he did arrange his opinions to suit the crowd, he

must "denounce

Vallandigham as a disunionist and a

traitor. He is neither, as I believe in

my heart." The test for a so-called

loyal man was repugnant to Tom. By it

he must hold the South wholly

accountable for starting the war, when actually

it was only partially responsible. He

must support the emancipation meas-

ures of the administration under the

assumption that failure to do so was a

contributing factor behind southern

military successes! He must help save

the Union by a quiet acquiescence in the

arbitrary arrests of men who were

devoted to the Union and constitutional

liberties. He must help muzzle a

party that would rebel rather than give

up its duty to the country. He could

not in good conscience meet any of the

requirements of this loyalty test.

For Will's edification and as proof that

his views on arbitrary rule were

not based on mere political association,

Tom called in the lessons of history,

citing De Tocqueville, Henry, and Lieber

as men who feared absolute power

16 OHIO HISTORY

wielded by any ruler during time of war.

He had learned much from his

studies: "Altho all history and

every writer on the Science of gov't tells me,

that a nation's liberties are always in

danger, especially in time of war, that

'eternal vigilance is the price of

liberty' still to be 'loyal,' I must disregard

all this & the portents of the times

and say it is nonsense and criminal folly

to talk so now." Among other

portents of the times, Tom dwelt, as was his

wont, on the belief that Lincoln

intended to use the army as an instrument

to secure personal despotic power. Using

the army, which did not under-

stand the popularity of Vallandigham

with the people because it read only

Republican literature, the

administration stood ready to suppress Vallandig-

ham and his supporters by force. If

Lincoln should decide, as he might, to

put down all Copperhead candidates in

the 1863 elections, the army would

quickly come at his call to perform his

evil work. The Copperheads could

submit even to this outrage without

resistance, if there was any reason to

believe that a republican government

could be erected on the ruins of war.

But the Republicans were consumed in

their vision of power, and if the Cop-

perheads threatened to win control of

the government by the ballot after the

war, Lincoln would send the army to

crush them, saying that they wished to

try the Republicans for high treason and

other constitutional violations;

the army, accepting without question the

abolitionist contention that the

Copperheads were enemies who would

destroy the army once in power,

would fly to obey.

Whatever his political beliefs, Tom

insisted that his was no intent to dis-

courage his brother's support of the

war. Will must help thrash the rebels

for their part in starting the war. If

the Copperheads should resist con-

scription by force, Will should shoot

them down, too. But if the people rose

in defense of liberty and the purity of

the ballot, he must not "draw . . .

[his] sword against them." For they

would have truth and God on their

side. Having bared his political soul,

Tom beseeched Will to defend his

memory should he fall in defense of civil

liberty.

The events of May gave rise to a new

adventure for Tom. His idol,

Vallandigham, was in exile in Dixie. His

party organ, the Empire, having

been suppressed, could no longer publish

his communications. His passion

for debate was curbed by martial law.

His own arbitrary arrest by the

administration seemed possible. And his

"mobocracy" letter had diminished

him in the eyes of fellow Copperheads. A

few days after the rioting, feeling

much insecurity and apprehension for the

future, he began to consider

sheltering his family and himself from

danger by removing the household

to Europe.61 By late May he

had nearly resolved to make the journey; the

idea of taking his wife and two

children, though, had been abandoned be-

A YOUNG COPPERHEAD

17

cause the children were too young for

the rigors of ocean travel.62 Now

Tom's brother-in-law, George Harshman, a

teen-aged boy who evidently was

an epileptic, was to accompany him.

George's health was the professed

reason for the journey; not unimportant,

Tom believed, were the bene-

fits a European tour would confer upon

both travelers. Martha consented to

the separation because it would remove

Tom from politics and would enable

him to escape the draft. She reconciled

herself to his departure with the

thought that he could not take part in

the approaching political campaign in

Ohio--not that she was opposed to his

politics, she said, but because he

would face personal danger if he took to

the stump.63

Tom must have felt compelling reasons

for the journey, for by it he re-

nounced an opportunity to run for the

state legislature in the fall.64 He

also missed one of the great political

campaigns of American history--the

gubernatorial race between Vallandigham

and John Brough. Convinced of

the rightness of Copperhead opposition

to administration restrictions of

freedom of speech and press, Tom left

Ohio certain that such opposition

would be vindicated by Vallandigham's

election in the fall, a grand triumph

to be secured by 100,000 Buckeyes ready

to escort him by force from

Canada to Columbus for his

inauguration.65 Vallandigham, campaigning

from Canada, polled an impressive vote

but lost by 100,000 votes to Brough,

whose victory prompted Lincoln to

telegraph, "Glory to God in the Highest.

Ohio has saved the Union."

Awaiting departure from Boston in

mid-June, Tom found proof there of

the grubbing commercial spirit of New

England Yankees. A tour of this

foul nest of abolitionism revealed the

disposal of nearly all of Bunker Hill

for building lots and a sign on a

clothing store near Faneuil Hall bearing the

inscription, "One country, one

flag, one price for clothing here."66 And how

these Yankees had perverted the spirit

of liberty by incarcerating at Fort

Warren men whose only crime was acting

as free men did in 1776.

Leaving Boston in June, Tom toured

England, Scotland, France, Germany,

Switzerland, and Italy. He kept the home

community apprised of his move-

ments by dispatching almost daily travel

accounts to the Empire, from which

he somehow was able to exclude the sound

of controversy. His letters to his

wife were less placid. After she wrote

to him of the impracticability of her

and the children's joining him in

Europe, Tom evidently proposed to remain

in Europe indefinitely. For in a letter

filled with whimsical pathos, Martha

assented to his request to

"stay" in Europe if he really felt it impossible

to live in the North because of his

bitter feelings against the Lincoln ad-

ministration.67 If he

returned to Dayton, she feared that he would be killed

in civil strife there, and if he

lingered in Europe, she feared that he might

18 OHIO HISTORY

be trapped there by a war between the

United States and France. She became

so confused and bewildered by his

request that she sat on her chair and cried

while her baby screamed and kicked in

her lap. Perhaps the European

atmosphere was more receptive to Tom's

conservative beliefs than the air

of Dayton; perhaps the Old World respect

for social station appealed to him.

At least in England he could hear his views

on the Civil War endorsed. Visit-

ing a Charlie Sherbon of Broughton, who

"had a delightful painting in his

water-closet," Tom listened to

attacks on the Lincoln administration on the

score that its war acts had lost the

respect gained abroad by Democratic ad-

ministrations.68

From Dayton, Tom received a steady

stream of reports that must have

stirred his vivid imagination: the rebel

Morgan exercising the Dayton citi-

zenry with a foray near Hamilton;

furloughed soldiers throwing stones at

women returning home from a Democratic

picnic; the unpopularity of him

and Martha in Dayton; and Martha's

finding "Val's" wife agitated because

she had not received a letter from her

husband.69 Then there were discus-

sions at home on Tom's political future--discussions

candidly reported to

him. Will, at home on furlough, believed

his brother's political career ended,

asserting that the Republicans would

never have anything to do with him

and that the Democrats would say that he

forsook them in their hour of trial,

for which Martha was glad.70 If

Tom felt that his duty was to adhere to the

Democrats in Dayton, he should have

remained with them, commented his

mother, who was certain, however, that

his disenchantment with them was

his reason for leaving Dayton. Martha

told her, "I thought not."

Although Tom expected to be in Europe

for six months and even spoke of

living there indefinitely, he returned

to Dayton in October, shortly after the

defeat of Vallandigham and the Peace

Democracy in Ohio. Avowing his

intent to be done with politics, he

proposed to live quietly and keep out of

the "clutches of Mr. Lincoln."71 He disliked

living at the pleasure of men,

rather than under the constitution, but

the people had decided to vote in

favor of war and the way in which it was

conducted. "The case went to the

jury," he admitted, "&

they have rendered their verdict and I am not dis-

posed to move for a new trial."72

Still he would be an Ishmael: "Until I can

leave the country with my wife and

children forever, I propose to padlock

my lips and submit."73

He did not leave the country again, but

he did manage for a few months

to bridle his political temper. In the

meantime, he contented himself with

instructing Will as to the manner in

which to use the family friendship with

Grant as a means of procuring a place on

his staff. By January 1864, how-

ever, he was again demonstrating his

ability to appear at storm center.

A YOUNG COPPERHEAD

19

Evidently holding no resentment against

him for flying to Europe, the Peace

Democrats came to Tom asking permission

to put his name before the county

commissioners as a candidate for a

vacancy in the auditor's office created by

the death of the incumbent.74 That

the party might have had its eye on an

office that could be delivered by Tom's

father-in-law, Jonathan Harshman,

who was one of the commissioners, rather

than on Tom, seemed to escape

him. He received the appointment, and

immediately cries of nepotism arose

from the Journal. Besides the

flagrant nepotism it saw, the Journal lamented

that Tom was a disciple of Vallandigham

and a member in good standing of

the Copperhead peace party.75

Then the Empire took up Tom's cause in a

typically acid attack on the Journal.76 The

Journal in turn made a brutal

assault on Tom's character, enumerating

manifold examples of his corrupt

nature. His most execrable act--a brazen

affront to the community and his

father's memory--was that he had ridden

his father's horse through the

streets of Dayton but a few weeks after

the colonel's death.77 Tom should

resign, insisted the Journal, but

he refused and soon the row subsided.

In the next few months Tom devoted

himself largely to his newly acquired

office, though he continued interpreting

and justifying Copperhead policies

to his brother, who was still with the

army in the South. For Will he labored

over paragraph after paragraph to prove

that the Republicans used the

soldiers against the Copperheads. These

pandering Republicans were not

satisfied with spreading lies against

Copperheads to secure soldiers' votes:

they also plied furloughed soldiers with

whiskey to induce them to perpetrate

brutal outrages on peaceful Copperheads.

He cited as proof of his assertion

the assault on the Empire office

in March 1864 by drunken men of the

Forty-Fourth Ohio Infantry.78

Tom also presented a number of opinions

to Will on the policy the Demo-

cratic party should follow in the

presidential campaign of 1864. He still

believed in the inefficacy of a coercive

war for the preservation of the Union;

military success, such as the North was

now enjoying, would only make the

attainment of a union of hearts more

difficult. To attain that kind of union

Tom proposed several courses for the

Democrats to follow in the contest

for the presidency. First, Grant was the

man to achieve peace; he would

accept the Democratic presidential

nomination on a platform of opposition

to rebellion, but would, if elected,

reject predatory abolitionist programs.79

Next, Tom fixed his eye on McClellan as

the Democratic standard-bearer; he,

too, would prosecute the war, if

necessary, while checking abolitionism.

Though the Kentucky-Virginia

resolutionists within the Peace Democracy

would object to a man who might continue

the war--since they uncompro-

misingly argued that no human authority

could force the states to obey

20 OHIO HISTORY

unconstitutional laws--Tom thought the

time for compromise was at hand if

the Democrats wished to win the

election. McClellan as a Democratic presi-

dent could offer peace terms to the

South; and the South would readily return

to the Union if it could occupy a

position of equality in a confederacy and

retain its social institutions as

before.80

June saw Tom making predictions before

Democrats as to the role Val-

landigham would take in the national

convention. Supposedly in Cleveland

on business, he received an unexpected

invitation--so the Empire reported--

to address the Democratic district

convention in session there.81 The Cleve-

land Morning Herald, however, deriding Tom, suggested that he had come

particularly to speak for Vallandigham:

Dating conviction back to the beginning

of the war, we have believed

Vallandigham to be a traitor, but far

from a fool. Yet should he not withdraw

from the field his nuncio, Low, who

appeared before the Democratic District

Convention in this city and spoke for

his principal, we shall be forced to the

opinion that martyrdom has made

Vallandigham daft.82

According to the Herald, Tom

indicated that Vallandigham, desiring party

unity and resolved not to press his

personal views on the national convention,

would not object to a convention

resolution denouncing rebellion, but would

object to any pledge promising

continuation of the war after a Democratic

president came to power:

Mr. Low, . . . the ambassador from

Vallandigham, is a simple agent, for

whether he truly represents

Vallandigham, or draws upon his own invention, no

man having a thimble full of sagacity

would expose the silly game he divulged.

He said that Vallandigham was willing

that the Chicago Convention should

denounce the origin of the war as it saw

fit, only it must not pledge the party to

its continuance. That is the silent

trick Vallandigham would play off, and we

expect to see the McClellan Democrats

caught in just that trap, even after this fair

warning that it had been set for them.83

When the Empire learned of the Herald

report, it assured its readers that

Vallandigham did not speak through

ambassadors.84 It quoted Tom as saying

that his words at Cleveland represented

his own ideas, not Vallandigham's.

The Empire implied that he had

conceived independently of Vallandigham

a plan to call on the national

convention to draft a peace resolution. The

convention, when it met, did adopt a

peace resolution under the aegis of

Vallandigham; possibly the callow youth

had played a part in originating

the famous peace plank (or war-failure

plank) that handicapped and em-

barrassed McClellan and Democratic

speakers throughout the 1864 cam-

paign.

A YOUNG COPPERHEAD

21

His Cleveland mission signaled Tom's

return to the hustings, and as the

national convention and campaign took

their course, he arrayed himself in his

old political trappings. In mid-August

he attended a mass rally of Democrats

in Dayton, where Vallandigham and other

speakers protested against the

draft and denounced Lincoln's refusal to

consider peace negotiations.85 In

late August he attended the Democratic

national convention at Chicago; there

he expected Franklin Pierce, not

McClellan, to win the great accolade. Val-

landigham, he was certain, could win the

presidential nomination if he so

desired; but the magnanimous

"Val" would not forward his own candidacy

because he did not wish to disrupt the

party.86 Tom failed to note that even

then Vallandigham was thrusting the

divisive peace plank upon the conven-

tion. In September and October he took

to the stump in all his youthful vigor.

His high resolve to be done with

politics had been somewhat ephemeral.

Throughout the campaign Tom adverted as

usual to the issue of constitu-

tional liberties. And for the first time

in his campaigning he leveled personal

attacks on Lincoln, whom he portrayed as

a vulgar jester.87 He had always

assailed Lincoln for his curtailment of

civil rights but had never sunk to

personal raillery. Realizing that he

could no longer argue the impractica-

bility of subduing the South while the

North enjoyed some measure of

military success, he now resorted to a

vague claim that only the Democratic

party could supply the unifying force

needed by the American people.88 He

said nothing of the peace plank,

uttering indeed nothing radical.

As it became apparent that Lincoln would

win a smashing victory, Tom

felt in desperation the imminence of a

draft call. He asked Will to secure

for him a three year substitute in

Tennessee for $400 or less.89 Then on

reflecting that Lincoln might revoke the

substitute clause without notice, that

all flight to Canada might then be cut

off, and that Lincoln's election meant

an increased demand for substitutes, he

begged Will to seek out a veteran,

or an alien, or a Negro for $400, or

$500, or $600, or $700.90 Any price for

anyone! At Lincoln's election in

November, Tom lapsed into absurdity.

Predicting the loss of liberty for the

white man in the United States as a

result of Lincoln's success, he decided

to exile himself in some foreign land.

He would not fight under any

circumstances and would not remain to be

beggared by buying substitutes for ten

or twenty years. The war must last

many years unless the North recognized

southern independence. No longer

could he stand the intolerance and

bigotry of the North and those in Dayton

who had sinned flagrantly against him.91

In spite of his fears of an unceasing

civil war, a military despotism, the

destruction of civil liberties, and the

draft, Tom remained in Dayton. He

continued to be a leading Copperhead

spokesman. Appomattox elicited no

|

|

|

public comment from him, but Lincoln's assassination compelled him to ap- pear in print. As unspeakable as Lincoln's murder was, it was, he asserted, no worse than that of Bollmeyer in 1862; but Bollmeyer's had been excused simply because he was a Copperhead.92 Then as "Philopolites" he con- tributed a series of long political essays to the Empire in September 1865, in reply to an editorial in the Journal. The editorial had stirred his pen with an inciting pronouncement: "This State Sovereignty, with all its attendant wickedness and crime, has its advocates in the North."93 Using the testimony of Madison, Adams, and many other revered Americans, Tom upheld the |

A YOUNG COPPERHEAD

23

theoretical right of nullification and

secession by the sovereign states, deny-

ing that the Civil War had really

negated the right.94

At the same time, he was taking an

active part in local politics. As a

reward for clinging to his principles

through four trying years and for his

good part in preserving the party in

those years, Democratic party members

in 1865 nominated him as their candidate

for prosecuting attorney for

Montgomery County.95 To the

nominating convention Tom spoke glowingly

of the party's record in the Civil War.

All the advantages gained by the

struggle could have been secured, he

said, by the use of the conciliatory

program advanced by the Peace Democracy;

so there was no reason for

Democrats to deal in recriminations if

called traitors now; in fact, believing

as they did, they would have been

traitors to themselves not to oppose the

war.96 The Journal stated that

Tom had brazenly justified Copperhead re-

sistance to the draft, Copperhead

opposition to soldiers' voting, and a multi-

tude of other Copperhead transgressions.

His hearty approval of the party's

extreme positions confirmed the report

that he was boasting of his ambition

and ability to supplant Vallandigham as

leader of the Dayton Democrats, the

Journal said.97 Whatever his political goals were,

they were temporarily

set back when he lost his election bid

by thirty-three votes in returns giving

victories to about half of the

Democratic ticket.98

Thenceforth, Tom's political course was

less frenetic and more conven-

tional. He did become embroiled in a

minor way with the Journal in 1866

over his support of the Copperheads

during the war; he still insisted that

their view of the war was nothing to be

ashamed of and that he would never

repudiate his support of them.99 In

1870 he was elected to the judgeship of

the Montgomery County Superior Court,

after filling an unexpired term,

but he failed to receive the party's

endorsement for renomination in 1875.

Returning to his law practice, Tom

prepared himself for the ministry

and became an ordained minister in the

Presbyterian Church in 1880. The

years finally wrought a change too in

his beliefs about the Civil War. Ad-

dressing a Grand Army of the Republic

post in 1885 at Mt. Vernon, Ohio,

fittingly enough the scene of

Vallandigham's challenge of General Order No.

38, Pastor Tom Lowe praised graying

veterans with godly fervor: "You

fought once to preserve from destruction

a beneficent government and to

destroy human slavery. You were on the

right side then; on God's side."100

THE AUTHOR: Carl M. Becker is an assistant

professor of history at Sinclair

College, Dayton.

His account of the early years of the

subject of this

study was published in the Bulletin of

the Histori-

cal and Philosophical Society of Ohio

for October

1961.

NOTES

PICTURE OF A YOUNG

COPPERHEAD

1 Biographical notes on John W. Lowe by

Thomas O. Lowe, in Lowe Manuscripts Collection,

Dayton Public Library. All Lowe

manuscripts cited hereafter are in this collection. For an account

of John W. Lowe's life, see also the Xenia

Torchlight, September 18, 1861.

2 J. L. Rockey, History of Clermont

County, Ohio (Philadelphia, 1880), 137. Fishback had some

illustrious sons: George was an editor

of the St. Louis Democrat, and William was a law partner

of Benjamin Harrison in Indianapolis.

3 U. S. Grant to John W. Lowe, June 26,

1846. The original letter is not in the Lowe Collection,

but the copy in that collection,

according to the penciled notes of Thomas Lowe, was made from

the original in the possession of his

brother William. The copy is identical with the copy pub-

lished by Hamlin Garland in "Grant

in the Mexican War," McClure's Magazine, VIII (1897),

366-380. In his biography of Grant, Captain

Sam Grant (Boston, 1950), Lloyd Lewis calls attention

to the friendship between Lowe and Grant

while they were living in and around Batavia.

4 Letters to his father of November 20,

1853, and March 12, 1854, contain vivid accounts of

these debates.

5 Freeman Cary to John W. Lowe, June 23,

1853; Thomas O. Lowe to John W. Lowe, March

12, 1854.

6 Thomas O. Lowe to John W. Lowe,

December 30, 1855.

7 Thomas O. Lowe to John W. Lowe, August

24, September 7, 1856. A fuller account of Tom

Lowe's youth may be found in Carl M.

Becker, "The Genesis of a Copperhead," Historical and

Philosophical Society of Ohio, Bulletin,

XIX (1961), 235-253.

8 Journal of Thomas O. Lowe.

9 An excellent definition of the factions in the wartime Democratic party

may be found in

William F. Zornow's "Clement L.

Vallandigham and the Democratic Party in 1864," Historical and

Philosophical Society of Ohio, Bulletin,

XIX (1961), 23.

10 Eugene H. Roseboom and Francis P.

Weisenburger, A History of Ohio (Columbus, 1956),

189; Wood Gray, The Hidden Civil War (New

York, 1942), 43, 74.

11 Thomas O. Lowe to John Wallace,

August 14, 1861.

12 Thomas

O. Lowe to John Wallace, August 24, 1861.

13 Ibid.

14 Ibid.

15 Thomas O. Lowe to William R. Lowe,

January 20, 1862.

16 Thomas O. Lowe to William R. Lowe,

January 8, May 16, 1862.

17 Thomas O. Lowe to Members of the

Session of the Deacons of the First Presbyterian Church,

October 7, 1861.

18 Thomas O. Lowe to Dr. Thomas E.

Thomas, October 22, 1861, in Alfred A. Thomas, ed.,

Correspondence of Thomas E. Thomas ([Dayton?], 1909), 119-120.

19 Thomas O. Lowe to William R. Lowe,

April 27, 1862.

20 The story of political life in Dayton

during the war is described in Irving Schwartz, "Dayton,

Ohio, During the Civil War"

(unpublished master's thesis, Miami University, 1949).

21 Dayton Daily Journal, June 23, 1862; Dayton Weekly Empire, June 28,

1862.

22 Dayton Daily Journal, June 23, 1862.

23 Thomas O. Lowe to William R. Lowe,

June 28, 1862.

24 George H. Porter, Ohio Politics

During the Civil War Period (New York, 1911), 107, 139-140.

25 Thomas O. Lowe to William R. Lowe,

July 12, 21, 1862.

26 Thomas O. Lowe to William R. Lowe,

July 12, 1862.

27 Thomas O. Lowe to William R. Lowe,

August 9, 23, 1862.

28 Speech delivered at Pyrmont,

Centerville, Harshmanville, Alexandersville, Miamisburg, and

Dayton. Journal of Thomas O. Lowe. A

summary also appeared in the Dayton Daily Empire,

September 26, 1862.

29 "Peace," a speech delivered

sometime in October at Hamilton, Germantown, and New

Lebanon. Journal of Thomas O. Lowe.

30 Speech delivered in Dayton, August 2,

1862. Journal of Thomas O. Lowe. See also "Jacobins,"

in the Lowe journal.

31 See footnote 29 above.

NOTES

77

32 See footnote 28 above.

33 The main points of Crittenden's plan

were these: slavery should be prohibited in national

territory north of the line 36?? 30' but

given federal protection south of that line; future states,

north or south of that line, might come

into the Union with or without slavery as they wished.

34 Dayton Daily Empire, August 7,

1862.

35 Clermont Sun (Batavia), August

20, 1862. Clipping in Thomas O. Lowe's Political Scrapbook.

36 Clermont Courier (Batavia),

August 27, 1862. Clipping in Thomas O. Lowe's Political

Scrapbook.

37 Clermont Courier, August 29, 1862.

38 Thomas O. Lowe to William R. Lowe,

August 2, 1862.

39 Dayton Daily Journal, November

3, 1862.

40 Dayton Daily Empire, November 3, 1862.

41 Ibid., November 21, 1862.

42 "Social Proscription,"

April 3, 1863. Journal of Thomas O. Lowe.

43 Thomas O. Lowe to William R. Lowe,

March 28, 1863.

44 Thomas O. Lowe to William R. Lowe,

January 23, 1863.

45 Thomas O. Lowe to William R. Lowe,

February 21, 1863.

46 Thomas O. Lowe to William R. Lowe,

March 7, 1863.

47 Thomas

O. Lowe to William R. Lowe, March 23, 1863.

48 Dayton Weekly Empire, February

7, 1863. Tom signed this article as "Hampden."

49 Besides

prohibiting the giving of aid and comfort to the enemy, General Order No. 38

announced that "the habit of

declaring sympathy for the enemy will not be allowed in this depart-

ment." The order suggested that the

department would take a loose construction in judging

whether words were spoken in sympathy

with the enemy.

50 See Dayton Daily Empire, May

5, 1863.

51 Dayton Daily Journal, May 6,

1863.

52 This account is based primarily on

Tom's letter of May 11 to Will. The letter presents a vivid

description of the violence of the day.

53 Dayton Daily Journal, May 7,

1863.

54 Ibid.

55 Anderson, a resident of Dayton, was

the Union party's candidate for lieutenant governor

in 1863.

56 Thomas O. Lowe to William R. Lowe,

May 14, 1863.

57 Dayton Daily Journal, May 8,

1863.

58 Ibid., May 12, 1863.

59 Ibid., May 14, 1863.

60 Thomas O. Lowe to William R. Lowe,

May 27, 1863.

61 Thomas O. Lowe to William R. Lowe,

May 14, 1863.

62 Thomas O. Lowe to William R. Lowe,

May 30, 1863.

63 Martha Lowe to William R. Lowe, June

24, 1863.

64 Thomas O. Lowe to William R. Lowe,

February 7, 1863. At this time Tom fully expected to

receive a nomination from his fellow

Peace Democrats.

65 Thomas O. Lowe to William R. Lowe, June 14, 1863.

66 Thomas

O. Lowe to Martha Lowe, June 23, 1863.

67 Martha Lowe to Thomas O. Lowe, August

28, September 8, 1863.

68 Thomas O. Lowe to Martha Lowe, August

3, 1863.

69 Martha Lowe to Thomas O. Lowe, July

14, August 1, 1863.

70 Martha

Lowe to Thomas O. Lowe, August 17, 1863.

71 Thomas O. Lowe to William R. Lowe,

October 25, 1863.

72 Thomas O. Lowe to William R. Lowe,

November 8, 1863.

73 Thomas O. Lowe to William R. Lowe,

October 26, 1863.

74 Thomas O. Lowe to William R. Lowe,

January 3, 1864.

75 Dayton Daily Journal, January 5, 1864.

76 Dayton Daily Empire, January

6, 1864.

77 Dayton Daily Journal, January

9, 1864.

78 Thomas O. Lowe to William R. Lowe,

March 6, 1864. See Dayton Daily Journal, March 4,

1864.

79 Thomas O. Lowe to William R. Lowe,

February 6, 1864.

80 Thomas O. Lowe to William R. Lowe,

April 2, 1864.

81 Dayton Weekly Empire, July 2, 1864.

82 Cleveland Morning Herald, June

25, 1864.

78

OHIO HISTORY

83 Ibid.

84 Dayton Weekly Empire, July 2,

1864.

85 Thomas O. Lowe to William R. Lowe,

August 14, 1864.

86 Thomas

O. Lowe to William R. Lowe, August 25, 1864.

87 Speech

delivered in Miamisburg and Wayne School House. Journal of Thomas O. Lowe.

88 Thomas O. Lowe to William R. Lowe,

October 2, 8, 1864.

89 Thomas O. Lowe to William R. Lowe,

October 16, 1864.

90 Thomas O. Lowe to William R. Lowe,

October 29, 1864.

91 Thomas O. Lowe to William R. Lowe,

November 11, 1864.

92 Dayton Daily Empire, May 13,

1865.

93 Dayton Daily Journal, September

2, 1865.

94 See Dayton Weekly Empire, September

2, 9, 16, 1865, and Dayton Daily Empire, September

4, 9, 1865.

95 Dayton Daily Empire, September 11, 1865.

96 Ibid., September 12, 1865.

97 Dayton Daily Journal, September 22, 1865.

98 Dayton Daily Journal, November 11, 1865.

99 Dayton Daily Journal, September 27, 1866.

100 Address by Reverend Thomas Lowe,

"The Eternal Warfare," given at the Presbyterian Church

of Mt. Vernon, Ohio, May 24, 1885,

before the Joe Hooker G.A.R. Post.

JOHN BROWN AND THE

MASONIC ORDER

1 Charles C. Cole, Jr.,

"Finney's Fight Against the Masons," Ohio State Archaeological and

and Historical Quarterly, LIX (1950), 270-286.

2 Ernest C. Miller, John Brown: Pennsylvania Citizen (Warren, Pa.,

1952), 10.

3 Kansas City Journal, April 8, 1881.

4 Manuscript note by George B. Gill in

the Richard J. Hinton Papers, Kansas State Historical

Society, Topeka.

5 Masonic Beacon (Akron, Ohio), October 7, 1946.

6 Miller, John Brown, 10.

7 Henry L. Kellogg, "How John Brown

Left the Lodge," in Christian Cynosure (Chicago),

March 31, 1887. The article is based on

an interview with Owen Brown.

8 A good short account of the

anti-Masonic crusade is found in Alice F. Tyler, Freedom's Ferment

(Minneapolis, 1944), 351-358.

9 Edward Conrad Smith, Dictionary of

American Politics (New York, 1924), 15-16.

10 Milton W. Hamilton,

"Anti-Masonic Movements," in James Truslow Adams, ed., Dictionary

of American History (New York, 1940), I, 82.

11 One Hundredth Anniversary of

Crawford Lodge No. 234, F&AM (Meadville, Pa., 1948), 4-5.

12 "His Soul Goes Marching

On," in Cleveland Press, May 3, 1895, quoted in Oswald Garrison

Villard, John Brown, 1800-1859: A

Biography Fifty Years After (Boston, 1910), 26.

13 Kellogg, "How John Brown Left

the Lodge."

14 Interview by Katherine Mayo with

Sarah Brown, September 16-20, 1908. Villard Papers,

Columbia University Library.

15 Interview by Katherine Mayo with

Henry Thompson, September 1, 1908. Villard Papers.

16 Interview by Katherine Mayo with

George B. Gill, November 12, 1908. Villard Papers.

17 John Brown to Owen Brown, June 12,

1830. Original letter owned by Dr. Clarence S. Gee,

Lockport, New York.

18 The Crawford Messenger of

April 29 and May 20, 1830, reprinted the entire Anderton

pamphlet, titled Masonry the Same All

Over the World: Another Masonic Murder. Articles in

subsequent numbers discussed the

statement and branded Anderton as a fraud. Several articles in

Volumes I (1830) and II (1831) of the Boston

Masonic Mirror offer proof that Anderton was an

impostor and that the incident described

could not have occurred.

19 The quotation is taken from the

original Brown manuscript as reprinted in the Appendix to

Villard, John Brown, 659-660.

20 Interview by Katherine Mayo with

George B. Gill.

21 Salmon Brown to Frank B. Sanborn,

November 17, 1911; Salmon Brown to William E. Con-

nelley, May 28, November 16, 1913. These

letters are in the author's own collection. See also

Salmon Brown, "John Brown and Sons

in Kansas Territory," in Louis Ruchames, John Brown

Reader (London, 1959), 189-197, reprinted from Indiana

Magazine of History, XXXI (1935),

142-150.