Ohio History Journal

ROBERT A. BUERKI

Pharmaceutical Education in

Nineteenth-Century Ohio

The development of pharmacy as a

profession in America had its roots in

English customs and traditions, the

colonial practice of pharmacy differing

from that of its mother country only in

being more lax and unrestricted and

standing on a somewhat lower level. Only

a small minority of its practition-

ers was educated beyond an

apprenticeship that lacked both the system and

standards that strong English guilds had

once given it. Not until after the

Civil War was any school of pharmacy

founded as a regularly recognized in-

stitution or as a part of a more

comprehensive educational organization; in-

deed, formal academic study in pharmacy

as a prerequisite to licensure would

not be required in any state until 1905.

Early attempts at pharmaceutical

education in the United States met with

varying degrees of success. Until 1865,

all formal instruction for the practice

of pharmacy centered in one southern

medical collegel and, more importantly,

in five independent schools operated by

pharmacists through their local asso-

ciations, called "colleges of

pharmacy."2 These organized groups of pharma-

cists and druggists were determined that

their apprentices would be better edu-

cated than they themselves were. Less

altruistic, but no less important exter-

nal stimulation came from physicians who

saw pharmacy emerging as a sub-

sidiary branch of their own somewhat

more developed profession, from a drug

market infested by substandard and

adulterated drugs, and from publicity at-

tending the accidental poisonings

attributed to ignorant drug vendors.3 In

Robert A. Buerki is Associate Professor

of Pharmacy Practice and Administration at The

Ohio State University.

1. In 1838, a pharmacy course was

instituted by the Medical College of Louisiana, which

later became part of Tulane University.

Graduating only one or two pharmacy students a year

before 1861, the venture was never

influential on the development of university instruction in

pharmacy or on practice, but rather

served as an example for other medical colleges that en-

tered pharmaceutical education in the

1860s. See Glenn Allen Sonnedecker, "American

Pharmaceutical Education Before

1900," (unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, University of

Wisconsin, 1952), 59-60.

2. At this time in England,

"college" referred to corporations with scientific aims as well as

to educational institutions. The term

had a like meaning in France, where Parisian apothecaries

had established a College de

Pharmacie in 1777 with educational as

well as professional func-

tions.

3. Glenn Sonnedecker, "The College

of Pharmacy During 75 Years at Ohio State

University," unpublished address

before the Ohio Academy of Medical History, meeting in

Pharmaceutical Education

43

Philadelphia (1821), New York (1829),

and Baltimore (1841) and, later, in

Chicago (1859) and St. Louis (1865), the

organizers of these schools sought

not only to supplement the practical

information gathered by their apprentices

during their in-service training, but to

organize the scattered fragments into a

systematic whole.4

In these early schools, physicians and,

later, master pharmacists provided

instruction in the form of lectures two

or three evenings a week during the

winter months. There were no

requirements for admission, save possibly ap-

prenticeship with some preceptor;

apprentices would attend the same lectures

twice in successive winters or possibly

oftener; there was little laboratory in-

struction available.5 To

graduate, the apprentices had to pass an examination

given by the lecturers and an examining

committee of the college and show

proof of a satisfactory apprenticeship

of four years, which included "attendance

upon lectures."6

Since the practice of pharmacy at the

time was considered by most

American pharmacists and physicians as

an art that could be best learned by

compounding the remedies in common use,

the early schools enjoyed neither

custom nor prosperity, and in more than

one instance the training of appren-

tices had to be delayed a number of

years.7 The number of apprentices attend-

conjunction with the 75th annual meeting

of the Ohio Historical Society, Columbus, Ohio, April

30, 1960, 3, upon which much of this

paper is based. Also see Sonnedecker, "American

Pharmaceutical Education Before

1900," 54, 58, and 63. Comparable conditions in American

medicine also produced untimely

institutional deaths. See Allan Nevins, The Emergence of

Modern America, 1865-1878 (New York, 1927), 276-78.

4. Two other local associations were

organized during this period, in Boston (1823) and

Cincinnati (1850), but neither were able

to sustain a regular school of pharmacy until after the

Civil War.

5. Edward Kremers, "The Teaching of

Pharmacy During the Past Fifty Years," The

Druggists Circular, 51 (January, 1907), 72. Apprentices were expected to

receive their practi-

cal training in the drug store. In

Chicago, for example, students "were encouraged to read,

study and experiment, utilizing the

opportunities afforded in the shops....

The teachers pos-

sessed the equipment necessary for

demonstration of the lectures, but there were no laborato-

ries." W[illiam] B. Day, "The

School of Pharmacy," in The Alumni Record of the University of

Illinois, edited by Carl Stephens (Dixon and Chicago, 1921),

xxvi.

6. Kremers, loc. cit. Kremers compared

the schools of the colleges of pharmacy during this

period as Fortbildungsanstalten, "comparable

to the evening schools of the several trades in

our larger cities of to-day."

7. Thus, the "school of

undergraduates" of the College of Pharmacy of the City and County

of New York was "in a somnolent

condition" between 1857 and 1859. Curt P. Wimmer, The

College of Pharmacy of the City of

New York (New York, 1929), 20 and 50.

The school of the

Maryland College of Pharmacy was more or

less active until 1847, "but thereafter languished

until 1856, when . . . it was thoroughly

reorganized." [Frederick Stearns], "Report on the

Progress of Pharmacy: Education," Proceedings

of the American Pharmaceutical Association,

7 (1858), 87. The Chicago College of

Pharmacy suspended its courses of lectures upon the

outbreak of the Civil War and did not

reopen its school until 1870. Albert E. Ebert, "Historical

Sketch of the Chicago College of

Pharmacy," ([Chicago?], n.d.), 2, American Pharmaceutical

Association Archives, Washington, D.C.,

cited by Kremers, op. cit., 67. Even after 1865 at the

St. Louis College of Pharmacy there were

a few years when "no lectures were delivered be-

cause there were not a sufficient number

of students to form classes." W[illia]m C. Bohn,

44 OHIO

HISTORY

ing lectures in these colleges before

the Civil War was small, and the number

who graduated was still smaller.8 In

1854, a commission organized by the

newly organized American Pharmaceutical

Association complained that the

country had been

deluged with incompetent drug clerks,

whose claim to the important position they

hold or apply for is based on a year or

two's service in the shop, perhaps under cir-

cumstances illy calculated to increase

their knowledge. These clerks in turn be-

come principals, and have the direction

of others-alas! for the progeny that some

of them bring forth, as ignorance

multiplied by ignorance will produce neither

knowledge nor skill.9

Even the Association did not expect

apprentices to study at one of the phar-

macy schools. Rather, it admonished all

levels of pharmacy personnel to read

the pharmaceutical literature

"regularly and understandingly and assist [their]

reading by experiment and

observation." The graduates of schools of phar-

macy were urged to "act as examples

to their less favored brethren."10

The era of the pharmacy schools

sponsored by local pharmaceutical associa-

tions ended with the Civil War; from

that time on, pharmacy schools were

founded in one of four ways: privately

by groups of pharmacists organized

only for that purpose; as parts of

private or denominational universities and

colleges; as divisions of medical

colleges; or, most importantly, as parts of

state universities. The private or

"proprietary" schools, depending partly on

the approval of their

pharmacist-trustees and financial supporters and more on

the fees paid by their students, were

reluctant to offer much in the line of de-

manding training that might diminish the

student body. On the other hand,

the pharmacy courses sponsored by

medical colleges posed a territorial threat

to leaders within pharmacy.11 With

the establishment and growth of the state

"Our Alma Mater and We Her

Children," Silver Anniversary Report of the Alumni Association

of the St. Louis College of Pharmacy (St. Louis, 1901), 27, cited by Kremers, op. cit., 68.

8. Among the 31,443,321 people in the

United States in 1860 there were only 11,031 who

served as apothecaries or druggists; of

these, not more than 514 had graduated from a phar-

macy course in the United States. Henry

L. Taylor, "Schools and Colleges of Pharmacy," The

Pharmaceutical Era, 45 (May, 1912), 336; and Sonnedecker, "American

Pharmaceutical

Education Before 1900," 52, n. 17.

9. W[illiam] Procter, Jr., E[dward]

Parrish, D[avid] Stewart, and J[ohn) Meakim, "Address

to the Pharmaceutists of the United

States," Proceedings of the American Pharmaceutical

Association, 3 (1854), 14.

10. Ibid., 391-92. The Association,

however, recognized the "vast importance ... of good

schools of pharmacy, where the sciences

pertaining to our art are regularly taught," and ex-

pressed its willingness to extend its

"countenance and encouragement to those already existing,

and to all new efforts."

11. Pharmacy historian Glenn Sonnedecker

notes that while these leaders were ready to

recognize a period of study at a medical

college as equivalent to study at a college of phar-

macy, "they could not sanction any

step that might surrender pharmaceutical education to

medical domination, and thus lead the

profession back to the situation from which it had

scarcely escaped." Glenn

Sonnedecker, Kremers and Urdang's History of Pharmacy (4th ed.,

Pharmaceutical Education

45

universities, however, the education of

pharmacists was placed on a different

plane, constituting, in the words of

pharmacy educator and historian Edward

Kremers, "the principal factor in

the onward development of pharmaceutical

education during this period."12

Pharmacy Training at State

Universities

A fervent, almost mystical belief that

education could free the common

man from domination and create a truly

classless society gripped many

Americans during the early years of the

Republic. This belief gave rise to,

and was fortified by, the lyceum

movement, public libraries, Chautauqua,

popular science lectures, public grammar

schools, and the tuition academies

that preceded the modem high schools.

Social pressure and a felt need for re-

spectability nurtured the growth of

schools in dentistry, in law, and in

medicine, the latter of which were

particularly sensitive to the importance-

and power--of credentialing.13

The founding of general institutions of

higher education likewise quickened

during this period, bolstered by

denominational efforts, although endowments

were usually small. Moreover, by 1860,

at least one state-controlled college

or university had been provided for by

almost all of the southern states and

many states west of the Alleghenies,

including Ohio's Miami University at

Oxford and Ohio University at Athens.14 For the most part, however, both

public and private institutions

continued to cling to the classical curriculum

that had served their upper-class

clientele so well since colonial times.15

The passage of the Morrill Land Grant

Act in 1862 jolted many leaders in

higher education. Three challenging

concepts developed from this signal leg-

islation: the belief that higher

education should be made available to broad

segments of the population, the feeling

that education in the applied sciences

should be given wide recognition and

significant status, and the conviction

that universities supported by public

funds should serve both the immediate

and long-range needs of society by

performing broad public services and by

rev.; Philadelphia, 1976), 231-32.

12. Kremers, op. cit., 76.

13. More than eighty medical schools had

been established in the United States before the

Civil War. See William Frederick

Norwood, Medical Education in the United States Before the

Civil War (Philadelphia, 1944), 431.

14. See Elwood P. Cubberley, Public Education

in the United States: A Study and

Interpretation of American

Educational History (Boston, 1934),

269; Charles F. Thwing, A

History of Higher Education in

America (New York, 1906), 328; and

Edwin Grant Dexter, A

History of Education in the United States

(New York, 1904), 279; all cited by

Sonnedecker,

"American Pharmaceutical Education

Before 1900," 67.

15. The notable exception in pharmacy,

the College of Pharmacy at Baldwin University at

Berea, Ohio (1865-76), is discussed

below in some detail.

46 OHIO

HISTORY

engaging in activities designed to serve

the people.16 The Morrill Act thus

wove the strands of public interest in

practical and applied science and public

faith in the power of the educational

process into the fabric of American

higher education and provided the

initial financial support to assure the suc-

cess of an entirely new type of

institution, the land-grant college. To the

struggling health professions in

mid-nineteenth-century America, the Act

brought the hope for stability and

increased public recognition; to the increas-

ingly cramped and limited system of

American pharmaceutical education, the

effect of the Morrill Act was no less

than profound.

The first state-supported institution to

produce graduates in pharmacy was

the Medical College of the State of

South Carolina. The first two students

were graduated in 1867 and a few more

during the 1870s, but by about 1885

the pharmacy department at Charleston

had died out, not to be reorganized un-

til 1894.17 The University of South

Carolina at Columbia likewise gave

some attention to pharmacy beginning

about 1866 as part of a "School of

Chemistry, Pharmacy, Mineralogy, and

Geology," but no students graduated

in pharmacy before the University

collapsed in 1877 for lack of legislative

support. In 1884, a reorganized South

Carolina College supported by a land

grant opened a School of Medicine and

Pharmacy; from it and from a fully re-

constituted university College of

Pharmacy (1888) emerged a thin trickle of

pharmacy graduates until the pharmacy

course again collapsed in 1891.18

These struggling early southern efforts,

reflecting the severe impact of the

Reconstruction period on the parent

institutions, could not strike the spark for

the revolution to come in pharmaceutical

education; this spark came from the

Midwest.

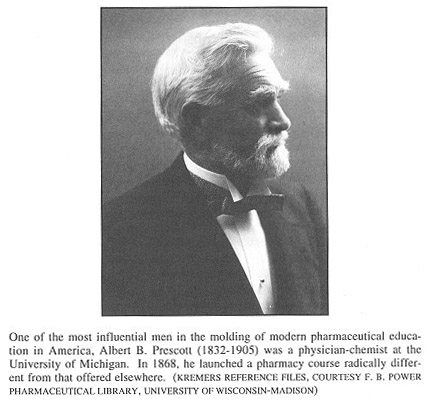

The revolution began in 1868 when the

University of Michigan initiated a

pharmacy curriculum that rejected

several assumptions common to the early

association-based schools of pharmacy.

In a bold innovation, physician-

chemist Albert B. Prescott introduced

extensive laboratory instruction coupled

with basic science, making the academic

study of pharmacy practically a full-

time occupation. Like its southern

predecessors, the Michigan school was

16. See Robert G. Mrtek,

"Pharmaceutical Education in These United States-An

Interpretive Historical Essay of the

Twentieth Century," American Journal of Pharmaceutical

Education, 40 (November, 1976), 363; and William A. Kinnison, Building

Sullivant's Pyramid:

An Administrative History of the Ohio

State University, 1870-1907 (Columbus,

1970), x-xi.

17. Sonnedecker, "American

Pharmaceutical Education Before 1900," 106. Like its prede-

cessor at the Medical College of

Louisiana, the South Carolina program offered no innovations

of instruction and graduated few

students. See Sonnedecker, "The College of Pharmacy

During 75 Years at Ohio State

University," 5.

18. Sonnedecker, "American

Pharmaceutical Education Before 1900," 105-06. Instruction

resumed in September, 1924, with the

establishment of a new School of Pharmacy. Details

concerning a "School of

Pharmacy" as part of a "Medical College of Alabama, University of

Alabama" (1866) remain shrouded in

mystery. Ibid., 82.

|

Pharmaceutical Education 47 |

|

|

|

the outgrowth of earlier educational efforts on behalf of medical students;19 unlike its predecessors, the new school had outstanding laboratory facilities available to its students, a strong administration noted for pioneering innova- tions, and a faculty committed to the German model of modern research and the new scholarship.20 Moreover, the University had embarked on a vigorous

19. In 1860, Silas H. Douglas introduced a laboratory course in pharmaceutical preparations for medical students to give them practice in the handling of medicines, but "it was quite as much intended as general practical training in applied science." Albert B. Prescott, "Silas H. Douglas as Professor of Chemistry and Pharmacy," Pharmaceutical Review, 21 (September, 1903), 362. Douglas is generally regarded as the first professor of chemistry to teach at a state university (1844-77). 20. Sonnedecker, "American Pharmaceutical Education Before 1900," 127-29. "Michigan was one of the first state universities to free itself from the hampering influences of state poli- tics on the one hand and sectarian influences on the other; to open its doors to women on the same terms as men (1870); to begin the development of instruction in history (1857); education (1879); and government (1881) with a view to serving the state; and to examine and accredit the high schools (1871)." Cubberly, op. cit., 651. Thwing used the University of Michigan as an illustration of the dominance of German ideas in American higher education. Charles Franklin Thwing, The American and the German University: One Hundred Years of History |

48 OHIO

HISTORY

program of instruction without either

the cooperation of the practitioners in

the state, who were opposed to the idea,

or the legitimizing influence of a

state pharmacy practice act.21

Prescott's two-year course of

instruction consisted of four terms of three

months each and included ample

laboratory work in pharmaceutical chemistry,

microscopic botany, and pharmacy, but

required no apprenticeship as a prereq-

uisite to graduation. Prescott's

rejection of the time-honored notion that aca-

demic instruction should be merely a

rounding off of a prolonged apprentice-

ship, coupled with the profession's fear

of encroaching "state control" of

pharmaceutical education, quickly made

him an unpopular figure in pharma-

ceutical circles. Prescott explained the

advantages of scientific pharmaceutical

education before the 1871 meeting of the

American Pharmaceutical

Association with brevity and clarity,22

but suffered a stinging rebuke: his

school was refused recognition as a

college of pharmacy within the "proper

meaning" of the constitution and

bylaws of the Association.23 Even the

Association's Secretary, John M. Maisch,

could argue that it was "wrong to

give a pharmaceutical degree before the

graduate has had pharmaceutical expe-

rience."24 While a

strictly constitutional rejection of Prescott's bold break

with tradition may readily be

understood, the Association's opposition to the

advancement of pharmaceutical education

through an agency of the state and

apprehension about the University's

refusal to accept responsibility for ap-

prenticeship seems scarcely

comprehensible unless we understand the almost

total commitment of its leaders to the

educational ideology of the association-

based schools and their insistence on

continuing to develop pharmaceutical

education independently from the medical

profession. Moreover, in 1871 few

(New York, 1928), 106-07.

21. Sonnedecker, Kremers and Urdang's

History of Pharmacy, 234. The Michigan State

Pharmaceutical Association was founded

in 1874; the Michigan State Pharmacy Practice Act

was adopted in 1885. Ibid., 379 and 381.

22. A[lbert] B. Prescott,

"Pharmaceutical Education," Proceedings of the American

Pharmaceutical Association, 19 (1871), 425-29.

23. The Michigan school was judged

"neither an organization controlled by pharmacists, nor

an institution of learning which, by its

rules and requirements, insures to its graduates the

proper practical training, to place them

on a par with the graduates of the several colleges of

pharmacy represented in this

Association." George F. H. Markoe et al., "Report of the

Committee on the Credentials of the

Delegate from the University of Michigan," Proceedings

of the American Pharmaceutical

Association, 19 (1871), 47. Kremers

points out that the dis-

cussion which followed "showed that

the animus was directed against the institution and that

most of the persons taking part . . .

cared little about the constitutional aspect of the situation."

Kremers, op. cit., 77.

24. "We grant that as much

knowledge in physical and chemical science, and natural history

generally, as a young man may possibly

acquire before he enters a drug store is extremely de-

sirable"; Maisch stated, "but

we believe that with all his knowledge ... he will not be a phar-

macist until he has gone through a

regular system of [practical] training." [John M. Maisch],

"Remarks on Pharmaceutical

Education," Proceedings of the American Pharmaceutical

Association, 19 (1871), 96.

Pharmaceutical Education

49

states had a pharmacy practice act or a

state board of pharmacy to which the

responsibility for apprenticeship could

be shifted.25

Twelve years passed before the second

state university school of pharmacy

was founded at the University of

Wisconsin (1883), yet it would be incorrect

to infer that the profession had been

inactive during this time. Indeed, quite

the opposite was true: between 1871 and

1883, pharmacy practitioners in

thirty-one states had formed state

pharmaceutical associations, including Ohio

(1879); these associations, in turn, had

stimulated the passage of fifteen new

state pharmacy practice acts to regulate

professional practice and control entry

into the profession.26 In the

arena of pharmaceutical education, activity was

no less intense, if ultimately less

successful: of the eleven private and practi-

tioner-controlled proprietary schools

founded during this period, only five, in-

cluding the Cincinnati College of

Pharmacy (1871), survived by later affiliat-

ing with a private or public university.27

In contrast to the school at Michigan,

the Department of Pharmacy at the

University of Wisconsin was established

by legislative act upon the request of

the pharmacists of the state assembled

at the third annual meeting of their

new state association, one year after

the enactment of a state pharmacy prac-

tice act. Unlike Prescott, the first

Director of the new Department, pharma-

cist-scientist Frederick B. Power, made

practical experience a requirement for a

diploma, although not a prerequisite for

admission to the course.28 Purdue

University opened its School of Pharmacy

the following year (1884) "in re-

sponse to an earnest and growing demand

for a through and practical training

in pharmacy and pharmaceutical

chemistry.... by Indiana pharmacists," par-

ticularly master apothecary John N.

Hurty of Indianapolis, who was influen-

25. See Sonnedecker, Kremers and

Urdang's History of Pharmacy, 232-33. In 1871, only

South Carolina, Georgia, New York,

Alabama, and Rhode Island had adopted legislation

defining the practice of pharmacy and

limiting that practice to qualified practitioners.

Moreover, only six other states-Maine,

California, New Jersey, West Virginia, Vermont, and

Mississippi-had formed statewide

associations of pharmacy practitioners by 1871. Ibid., 381

and 379.

26. Ibid. The causal relationship

between the founding of state pharmaceutical associations

and the passage of state pharmacy

practice acts is strikingly evident. Ibid., 215.

27. Besides the Cincinnati school, the

practitioner-controlled schools founded during this pe-

riod were the Louisville College of

Pharmacy (1871), the National College of Pharmacy

(1872), the Tennessee College of

Pharmacy (1873), the California College of Pharmacy

(1873), and the Pittsburgh College of

Pharmacy (1878). The private institutions were

Georgetown College (1871), Columbian

College (1871), Iowa Wesleyan University (1871),

Vanderbilt University (1879), and Union

University (1881). Sonnedecker, "American

Pharmaceutical Education Before

1900," 117-18. For details concerning the later affiliations,

see Sonnedecker, Kremers and Urdang's

History of Pharmacy, 383-84.

28. Ibid., 234-35. Power came from the

ranks of practical pharmacy and was a graduate of

the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy.

"He recognized the desire of community pharmacists

not to risk losing the identity of the

concept of 'pharmacy' with that of 'drugstore,' by award-

ing a pharmaceutical degree to persons

without practical experience," Sonnedecker stresses.

50 OHIO

HISTORY

tial in arousing the interest of

Purdue's President John H. Smart.29 Until at

least the turn of the century, one of

these patterns would dominate the devel-

opment of state university schools and

colleges of pharmacy: professional

pressure or-in the case of the state

universities of Michigan and Ohio--the

persistence of an individual professor

of chemistry. Moreover, the stability of

the state colleges and universities

proved their merit: of the eighteen state-

sponsored schools and colleges of

pharmacy founded between 1884 and 1900,

only three would fail;30 in

stark contrast, of the thirty-six private, proprietary,

association-based, or medical

school-based schools and colleges of pharmacy

founded during this same period, only

three survived intact, eight others hav-

ing merged or affiliated with public or

private universities.31

29. Smart, in turn, convinced Hurty to

serve as professor of pharmacy in the new School for

at least two years. Hurty came to

Lafayette twice each week and gave practical instruction in

pharmacy and in the art of dispensing

medicines and filling prescriptions, which culminated in

1889 with the development of the first

course in dispensing pharmacy taught in the United

States. George Spitzer, "History of

Purdue University School of Pharmacy," unpublished

manuscript, Lafayette, Indiana, [1929],

1-2, 5 and 7, Kremers Reference Files, F. B. Power

Pharmaceutical Library, University of

Wisconsin School of Pharmacy, Madison, Wisconsin

[hereinafter referred to as

"Kremers Reference Files"]. Also see [Robert W. Babcock], A

Brief Account of the First Fifty

Years of Pharmacy Education at Purdue, 1884-1934 (Lafayette,

1934), 6.

30. The state-supported schools and

colleges are Purdue University (1884), the University of

Iowa (1885), the University of Kansas

(1885), Ohio State University (1885), South Dakota

State University (1888), the University

of Minnesota (1892), the University of Oklahoma

(1893), the University of Texas (1893),

the University of Washington (1894), Auburn

University (1895), the University of

Illinois, incorporating the Chicago College of Pharmacy

(1896), Washington State University

(1896), the University of North Carolina (1897), Oregon

State University (1898), and the

University of Tennessee (1898). The three unsuccessful state-

supported schools and colleges were the

University of Colorado (1884?-85?), the University of

Virginia (1887?-98?), and the University

of Maine (1895-1919). Compiled from Sonnedecker,

Kremers and Urdang's History of

Pharmacy, 384-85; and Sonnedecker,

"American

Pharmaceutical Education Before

1900," 83, 93, 117, and 119.

31. The three surviving schools and

colleges are Ohio Northern University, formerly Ohio

Normal University (1884); Ferris State

College, formerly Ferris Institute (1893); and the

Medical College of Virginia (1897). The

eight surviving merged or affiliated schools and col-

leges are the Iowa College of Pharmacy

(1882), affiliated with Drake University in 1886; the

Kansas City College of Pharmacy (1885),

affiliated with Lincoln and Lee University in 1927

and, later, with the University of

Kansas City in 1943; the Buffalo College of Pharmacy (1886),

affiliated with the University of

Buffalo-now the State University of New York at Buffalo-

in 1923; the Illinois College of

Pharmacy of Northwestern University (1886), absorbed by the

University of Illinois in 1917; Scio

College (1887), amalgamated with the Pittsburgh College of

Pharmacy in 1908; the Brooklyn College

of Pharmacy (1891)-now the Arnold and Marie

Schwartz College of Pharmacy-affiliated

with Long Island University in 1929; the New

Jersey College of Pharmacy (1892),

amalgamated with Rutgers University in 1927; and the

University College of Medicine at

Richmond (1893), amalgamated with Virginia School of

Pharmacy at the Medical College of

Virginia in 1913. Compiled from Sonnedecker, Kremers

and Urdang's History of Pharmacy, 384-85; and Sonnedecker, "American Pharmaceutical

Education Before 1900," 87, 97-98,

108, and 110.

Pharmaceutical Education

51

Pharmaceutical Education in Ohio

Before 1884

Before the Civil War, the practice of

pharmacy in Ohio was by and large

unprofessionalized. There was no

statewide organization of practitioners be-

yond the nucleus created by the

Cincinnati College of Pharmacy in 1850, and

there was no state or local pharmacy

practice acts. Most importantly, there

was no formal instruction available in

pharmacy from either local associa-

tions or institutions of higher

learning. As in most parts of the country at

the time, the Ohio youth who wanted to

learn pharmacy would apprentice

himself to the operator of a drug shop

for as long as he thought necessary be-

fore going out on his own. A more

aspiring youth might make his way to

an urban center, such as Cincinnati or

Cleveland, where a handful of primarily

foreign-trained master apothecaries

could offer pharmacy apprenticeships at a

higher level. After the Civil War,

however, the pace of professionalization in

Ohio pharmacy increased as a steady

rate.

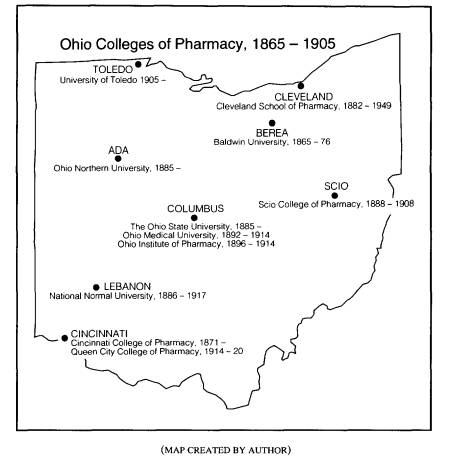

Baldwin University. The earliest instruction in pharmacy in the United

States under regular academic conditions32

emerged at Baldwin University in

Berea in 1865. The institution had

originated in 1844 as Baldwin Institute,

the gift of Berea grindstone

manufacturer John Baldwin to the Northern Ohio

Conference of the Methodist Episcopal

Church. In 1855, university powers

were granted.33 The 1865

catalog of the University described the course of

study in the new College of Pharmacy as

"regular recitation in Chemistry,

with lectures in the departments of

Professional Ethics, Botany, Materia

Medica and Practical Pharmacy, . . .

with experiments and practical illustra-

tions of the various pharmaceutical

processes of the laboratory." In addition,

instruction would also be given in

Practical and Analytical Chemistry and in

Photographic Chemistry, "embracing

the history of the Photographic process

and the manufacture of all

chemicals." The catalog spoke glowingly of

"numerous experiments in which the

students will take part ... to make the

instruction as particularly useful as

possible" and of "instruction in pharma-

ceutical operations and manipulations in

the manufacture of chemicals and

other preparations, in extemporaneous

pharmacy and in the dispensing of

32. The pharmacy curriculum established

in 1838 within the Medical College of Louisiana at

New Orleans and, after 1847, as part of

the University of Louisiana (now Tulane University)

claims historical priority in

instruction, but not as a separately constituted school or college of

pharmacy. The Louisiana course did not

flourish and probably was not well integrated with

either the Medical Department or the

parent University during most of the nineteenth century.

See John P. Dyer, Tulane: The

Biography of a University, 1834-1965 (New York, 1966), 21,

70n, and 134.

33. See W[illiam] O[xley] Thompson,

"Baldwin University and German Wallace College,

Berea, Cuyahoga County, Founded

1845," in James J. Burns, Educational History of Ohio

(Columbus, 1905), 343-44; and

"Baldwin University," in A History of Education in the State of

Ohio (Columbus, 1876), 234-35.

52 OHIO

HISTORY

medicine on prescription or

otherwise."34 Not the least interesting feature of

Baldwin's College of Pharmacy was its

practice of conferring the degree of

"Bachelor of Medicine,"

although those students not continuing for the M.D.

degree ordinarily entered the practice

of pharmacy.35 The University graduated

only thirty-three students over the next

ten years. There is no record of phar-

macy graduates or instructors after

1876, the University apparently having

closed its pioneering College because of

insufficient enrollment.36

Cincinnati College of Pharmacy. Meanwhile, the Cincinnati College of

Pharmacy had begun a regular systematic

course in pharmacy in 1871, culmi-

nating two decades of plans and dreams.

In 1851, for example, the members

of the College reported their intention

of "opening their School this session";

in 1858, the leadership made bold plans

for an "annual course of lectures for

Students in Pharmacy, in connection with

the lectures of the Ohio Medical

College." Neither plan came to

fruition.37 Sometime during the early

1860s, however, and perhaps before, the

College began to provide "personal

and indirect" monthly roundtable

discussions and home instruction in phar-

macy and materia medica by Edward S.

Wayne, in theoretical pharmacy by

William B. Chapman, and in theoretical

chemistry by Adolph Fennel. The

course covered three years, partly at the

small College room in Gordon's Hall

and partly at the homes of the

"faculty"; diplomas or certificates were not

given.38 This tentative

beginning was destroyed by the Civil War. The

College was revived as a professional

association in October, 1871, and regu-

lar instruction began that same

December, initially following the earlier in

34. Quoted by F[rederick] Roehm, Dean of

Baldwin-Wallace College in a letter to Edward

Kremers, December 24, 1931, Kremers

Reference Files. Adjusting the claims to probable

reality, we may tentatively interpret

them as meaning there were some demonstration experi-

ments. If there were regular laboratory

instruction, it would antedate the earliest teaching lab-

oratories known at the University of

Michigan (1868) and at the Philadelphia College of

Pharmacy (1870). See Sonnedecker,

"The College of Pharmacy During 75 Years at Ohio

State University," 9.

35. Mrs. Jon. Baldwin, Jr., ed., Alumni

Record of Baldwin University, 1846-1890 (Berea,

1890), 38-43, 46, 48-52, 55, and 57,

Kremers Reference Files.

36. Ibid., 14; and Crisfield Johnson,

comp., History of Cuyahoga County, Ohio (Philadelphia,

1879), 202.

37. [William Procter, Jr.],

"Editorial: Schools of Pharmacy," American Journal of

Pharmacy, 23 (October, 1851), 391; and Frederick Stearns,

"Report on the Progress of

Pharmacy: Education," Proceedings

of the American Pharmaceutical Association, 7 (1858),

88. "There is cause to fear that

our Cincinnati brethren have become lukewarm and lifeless as

regards the advancement of the College

of Pharmacy," Procter remarked the following year.

"The attempts hitherto made to get

up a school of pharmacy have proved unsuccessful."

William Procter, Jr., "Report on

the Progress of Pharmacy: Pharmaceutical Associations and

Education," Proceedings of the

American Pharmaceutical Association, 8 (1859), 104. Cited by

Sonnedecker, "American

Pharmaceutical Education Before 1900," 65 and 99.

38. Cha[rle]s T. P. Fennel,

"Cincinnati College of Pharmacy," in The Graduate [for] 1925,

edited by David Uhlfelder (Cincinnati,

1925), 19.

|

Pharmaceutical Education 53 |

|

formal roundtable format that had proved so popular.39 The first faculty in- cluded Wayne, Fennel, J. H. Judge, M.D., who taught chemistry, and F. H. Renz, who taught botany. "Whatever appealed as serviceable to a young man, ethically or professionally, was taught by these masters of pharmacy, all of whom were expert, practical apothecaries," the redoubtable John Uri Lloyd recalled with affection over half a century later. "The entire gauntlet in both operative and theoretical pharmacy was the field of these self-sacrificing servants."40 The College granted its first degree of "Graduate of Pharmacy" in

39. Harold C. Freking, "Gleanings from the Early History of the Cincinnati College of Pharmacy," American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 12 (July, 1948), 414. 40. John Uri Lloyd, "The College: Some Recollections and Notes," in The Graduate [for] 1925, 25. As students increased in numbers, the roundtable format was abandoned and "more |

54 OHIO

HISTORY

1873. In 1877, the College obtained the

first affiliation of its school with

the University of Cincinnati; in 1886,

the school became a "department" of

the University in the sense that its

students could draw upon its course offer-

ings without paying extra fees. This

affiliation was a loose one, however;

the character and administrative control

of the school remained fundamentally

the same until a formal affiliation

agreement was approved in 1945.41

Cleveland School of Pharmacy. The demise of pharmacy instruction at

Baldwin University probably paved the

way for the enthusiastic launching of

an independent Cleveland School of

Pharmacy by the Cleveland

Pharmaceutical Association in 1882.

Instruction began with a modest series

of twenty weekly lectures on

pharmaceutical chemistry by Nathan

Rosenwasser, a chemist with Strong, Cobb

& Company, but developed

rapidly. By 1885, the curriculum had

expanded to a program of 110 graded

lectures extended over a period of two

years, chemistry now being taught by

C. W. Kolbe, M.D., Ph.D., and pharmacy

being taught by Henry W.

Stecher, Ph.C.42 Curiously,

the School conferred no degree, Ohio law pro-

viding that no school might do so that

did not possess property amounting to

at least $5,000. In fact, at the time,

the School had no such ambition, being

content to prepare students for a final

year at either the Cincinnati College of

Pharmacy or the Buffalo College of

Pharmacy, both of which institutions

permitted the School's graduates to

enter their senior classes without further

examination. "The Cleveland School

is, and desires to be regarded as, only a

Preparatory School," its 1889 catalog declared, describing the School rather

whimsically as "a 'Jolly boat' in

the wake of the 'Big steamers."'43 In 1895,

however, the School added laboratory

instruction, and two years later finally

conferred the degree of

"Pharmaceutical Chemist" upon graduates of its new

formal though not more serviceable

processes were instituted."

41. Freking, op. cit., 416 and 418; and

"Pharmaceutical Colleges and Associations: The

Cincinnati College of Pharmacy," American

Journal of Pharmacy, 58 (October, 1886), 526-27.

Cited by Sonnedecker, "American

Pharmaceutical Education Before 1900," 100. Also see

"Cincinnati College of Pharmacy

Affiliates With University," American Druggist, 112

(December, 1945), 142. Up to 1905, the

College had graduated 696 students. "List of Alumni

of the Cincinnati College of

Pharmacy," in The Graduate [for] 1925, 139-56.

42. Carl Winter, "The Cleveland

School of Pharmacy: An Historical Sketch," Midland

Druggist and Pharmaceutical Review, 45 (January, 1911), 18-19. The Cleveland

Pharmaceutical Association had been

organized only two years earlier, in 1880. E. A.

Schellentrager, Association president at

the time, later recalled wondering "whether the young

men then engaged in our city pharmacies

. . . would be able to successfully cope with the re-

quirements of the proposed [Ohio]

pharmacy law." He urged the Association to establish the

School to aid those "who felt the

need of systematic training but were loath to give up their sit-

uations in order to seek pharmaceutical

education elsewhere." E. A. Schellentrager, "The

Cleveland School of Pharmacy," Merck's

Market Report, 1 (July, 1892), 13.

43. Seventh Annual Announcement of

the Cleveland School of Pharmacy, for the Session of

1888-89 (Cleveland, 1888), 17, Kremers Reference Files.

Pharmaceutical Education

55

three-year graded course.44 In

1908, the School became affiliated with

Western Reserve University and, in 1918,

a formal School of Pharmacy of

the University until the School itself

was discontinued in 1949.45

In 1884, therefore, Ohio's drug clerks

and apprentices could choose between

but two formal courses in pharmacy, both

of which were under the control of

the local pharmaceutical associations in

the state's largest metropolitan cen-

ters: the two-year graded curriculum

offered by the Cincinnati College of

Pharmacy in loose affiliation with the

University of Cincinnati and the initial

course of twenty lectures offered by the

Cleveland College of Pharmacy.

While these courses seemed more

representative of earlier educational efforts

by other local associations of

practitioners in other states than the bold and

innovative pharmacy curricula then being

offered by state universities in

Michigan, Wisconsin, and Indiana, they

do underscore the extreme importance

of the presence of a state pharmacy

practice act in encouraging the develop-

ment of pharmaceutical education: in the

two decades following the passage

of a state-wide pharmacy practice act in

Ohio, no less than six college- and

university-based pharmacy curricula

would be introduced within the state.

The 1884 Pharmacy Practice Act and an

Educational Response

As noted above, outside of an unpopular

1852 act regulating the sale of

poisons in Ohio,46 there was

no legislation regulating the practice of phar-

44. Winter, op. cit., 19-20. Between

1884 and 1904, the Cleveland school graduated a total

of 281 students, including 76 from the

"Junior Course," discontinued in 1890-91, 125 from the

"Senior Course," discontinued

in 1895-96, 75 with the degree of "Pharmaceutical Chemistry,"

and one 1904 graduate with the degree of

"Doctor of Pharmacy." 16th Annual Announcement,

Cleveland School of Pharmacy, Session

of 1897-98 (Cleveland, 1897), 19-22;

and 23rd Annual

Announcement, Cleveland School of

Pharmacy, Session of 1904-1905 (Cleveland,

1904), 15-

16, Kremers Reference Files.

45. "Western Reserve University,

The School of Pharmacy," [May, 1928], 3-4, Kremers

Reference Files. Between 1908 and 1918,

the business management of the School remained

under the control of a board of trustees

elected by the Cleveland Retail Druggists' Association.

Also see [Rufus A. Lyman],

"Miscellaneous Items of Interest: President W. G. Leutner of

Western Reserve University .. .," American

Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 13 (April,

1949), 408. The University's

administrative officers were unwilling to continue the School in

the face of the "critical financial

problems" it faced, "for to do so must mean the lowering of

standards that would inevitably be to

the discredit of both the university and the profession,"

Lyman reported sympathetically.

46. "An Act Regulating the Sale of

Poisons," Acts of a General Nature Passed by the Fiftieth

General Assembly of the State of

Ohio, L (Columbus, 1852), 167-68.

Apothecaries, druggists,

and others were required to maintain a

detailed register of poison sales to adults and could not

sell arsenic in pure form. The first

report of the Ohio State Pharmaceutical Association's

Committee on Pharmacy Law recommended

the amendment or abolishment of the law which it

considered "very illy adapted to

the purposes for which it was designed, and . . . a real source

of annoyance and discomfort to both

customers and to ourselves." Lewis C. Hopp, "Second

Annual Meeting of the Ohio State

Pharmaceutical Association," Proceedings of the Ohio State

Pharmaceutical Association, 2 (1880), 12.

56 OHIO

HISTORY

macy until 1873. On May 5 of that year,

the Ohio General Assembly passed

an act "to regulate the practice of

Pharmacy in certain cities of the first class"

having a population exceeding 175,000.

The law plainly was meant to apply

only to Cincinnati, Ohio's largest city

whose population at the time exceeded

216,000.47 The law created a

Pharmaceutical Examining Board which regis-

tered proprietors currently engaged in

the "retail drug and apothecaries' busi-

ness" or those "who shall hold

the diploma of an incorporated college of

pharmacy" without an examination

for a one-time fee of five dollars and set

up a mechanism for examining others who

would later enter the business;

non-owners could become registered as

"qualified assistants" under similar

provisions.48 Despite a rapid

growth in Ohio's population over the next

decade, the law still applied only to

Cincinnati.49

On September 2, 1879, forty-five druggists

met in Columbus to form a

new state association, hoping to extend

the Cincinnati law's protection to

other parts of the state, and while the

lofty goals of the new association in-

cluded provisions "to elevate the

character of the Pharmaceutical Profession,

to unite the reputable Druggists of the

state, to foster the education of those

learning the art, to stimulate the

talent of those engaged in Pharmacy, and ul-

timately to restrict the sale of

Medicines to persons qualified for the Practice

of Pharmacy,"50 the

latter goal clearly took precedence. Practitioners in the

47. "An Act to Regulate the

Practice of Pharmacy in Certain Cities of the First Class, and for

Other Purposes," General and

Local Laws and Joint Resolutions Passed by the Sixtieth General

Assembly, LXX

(Columbus, 1873), 287-88. Cities of the first class had been defined by the

Ohio General Assembly in 1869 as having

a population of at least 20,000. Without the

175,000-population proviso, the 1873 act

would also have applied to Cleveland, Columbus,

Dayton, and Toledo. See "An Act to

Provide for the Organization and Government of

Municipal Corporations," Chapter I,

"Classification of Municipal Corporations," General and

Local Laws and Joint Resolutions

Passed by the Fifth-Eighth General Assembly, LXVI

(Columbus, 1869), 149-50; and

"Table XXVI.-Population of Places of 4,000 Inhabitants and

Over, by Nativity: 1880 and 1870,

Ohio," in U.S. Department of the Interior, Census Office,

Compendium of the Tenth Census (June

1, 1880), rev. ed., Part I

(Washington, D.C., 1885),

460-61.

48. "An Act to Regulate the

Practice of Pharmacy in Certain Cities of the First Class, and for

Other Purposes," loc. cit.

Qualified assistants were to have at least two years apprenticeship

experience and attended "one full

course of lectures in chemistry, materia medica, and phar-

macy." Ibid., Section 6, 288.

49. By 1880, Cincinnati would grow to

over 255,000, Cleveland to over 160,000, and

Columbus and Toledo to over 50,000 each.

"Table XXVI.--Population of Places of 4,000

Inhabitants and Over, by Nativity: 1880

and 1870, Ohio," 460. In 1875, the Ohio General

Assembly would amend their 1873 act

slightly, establishing a procedure for examining quali-

fied assistants and removing the

restriction to the city of Cincinnati, but retained the 175,000

population requirement. "An Act to

Amend an Act Entitled 'An Act to Regulate the Practice

of Pharmacy, in Certain Cities of the

First Class, and for Other Purposes,' Passed May 5, 1873,"

General and Local Laws and Joint

Resolutions Passed by the Sixty-First General Assembly of

the State of Ohio, LXXII (Columbus, 1875), 16.

50. "List of Members," Proceedings

of the Ohio State Pharmaceutical Association, 1 (1879),

10; and T[homas] J. Casper,

"Minutes of the Meeting," ibid., 12. The meeting had been called

by Cleveland druggist Lewis C. Hopp, who

would become the first Permanent Secretary of the

Pharmaceutical Education

57

neighboring states of West Virginia,

Michigan, Kentucky, and Pennsylvania

had already organized their own state

pharmaceutical associations, and the

Kentucky association had already

agitated for and obtained a state pharmacy

practice act. In forming the Ohio State

Pharmaceutical Association, Ohio's

druggists simply hoped "to check,

if possible, the influx of incompetent

druggists from other States, who

[regard] our fair State a 'Mecca' for their op-

erations."51

A Standing Committee on Pharmacy was

appointed at the 1879 meeting

and brought forth a simple

recommendation the following year "to have the

existing Pharmacy Act so amended as to

apply to all cities and towns of five

thousand inhabitants and over."

While the Association adopted the recom-

mendation, no concrete legislative

proposal was brought forth until 1882.

That year, Committee Chairman John A.

Nipgen of Chillicothe presented a

professionally drafted proposed law that

received the close scruitiny and, fi-

nally, the enthusiastic endorsement of

the Association. The proposal con-

tained an unusual provision which would

prevent "officers or teachers in any

school or college of pharmacy" from

serving on the Ohio Board of Pharmacy.

In the view of Association President

Isaac N. Reed, schools and colleges

should not be allowed to propose laws

that could curtail or hamstring the ef-

forts of state pharmaceutical

associations. "A proper apprenticeship, supple-

mented by a thorough college of pharmacy

course, is the true method for the

education of druggists," Reed

stated, "and the time is fast approaching [in]

which all schools of polytechnics will

be well patronized, without the aid of

cunning devices by their professors to

secure special legislation in their fa-

vor."52 As a further

slap at the Cincinnati college, absolutely no mention

was made of pharmaceutical education in

the proposed bill; any person over

eighteen years of age who had been

continuously engaged in compounding or

dispensing medicines on the

prescriptions of physicians in any retail drug

Association.

51. Sonnedecker, Kremers and Urdang's

History of Pharmacy, 379 and 381; and

Schellentrager, op. cit., 13. In 1882,

Association President Isaac N. Reed would declare that

"Ohio should no longer allow

herself to be made the caldron into which all pharmaceutical in-

competencies may be dumped."

I[saac] N. Reed, "President's Address," Proceedings of the

Ohio State Pharmaceutical

Association, 4 (1882), 14.

52. Hopp, op. cit., 12-13. The 1881

Committee on Pharmacy Laws was called upon, and not

having a report to present was

discharged. A new Committee was charged with preparing "a

draft of a Pharmacy Law" and having

it "printed and a copy sent to each member at the ex-

pense of the association." Lewis C.

Hopp, "Third Annual Meeting of the Ohio State

Pharmaceutical Association," Proceedings

of the Ohio State Pharmaceutical Association, 3

(1881), 28 and 30. Also see J[ohn] A.

Nipgen, "Report of Committee on Pharmacy Laws,"

Proceedings of the Ohio State

Pharmaceutical Association, 4 (1882),

41; and Reed, op. cit., 15-

16. "I do not wish to be understood

as attempting to proclaim that colleges of pharmacy are

unnecessary institutions," Reed

added. "On the contrary, they are vital to the interests and real

progress of pharmacy, and should have

the co-operation and support of all State Associations."

58 OHIO

HISTORY

store in the United States was eligible

for examination for licensure.53 A

heavily amended version of the bill was

defeated by the Ohio House of

Representatives, and upon

reconsideration, referred to the Committee on

Medical Colleges and Societies where it

languished.54

In 1883, Association President D. C.

Peters, a Zanesville physician, urged

his listeners not to be discouraged.

There was "good reason to hope" that

with an increased membership in the

Association "our state law-givers will be

prevailed upon to afford such measures

of protection as justice to both phar-

macists and the people demand." He

recommended that the now-experienced

Committee on Pharmacy Laws be continued

and empowered to make what-

ever amendments would be necessary to

secure passage of the bill during the

next session of the Ohio General

Assembly "without changing the general

character and purpose of the bill."

Finally, he cannily suggested that

Association members in every country in

the state be mobilized as auxiliary

members of the Committee to lobby their

local representatives.55 Victory fi-

nally came on March 20, 1884; Governor

George Hoadly promptly appointed

the first five-member Board of Pharmacy,

which included Committee

Chairman Nipgen, who was subsequently

elected its first president.56 The

new law contained language assuring

Ohio's physicians the right to dispense

medications, permitting any retail

dealer to make or sell patent or proprietary

medicines, and allowing proprietors of

country stores to sell an astonishingly

wide variety of chemicals, drugs, and

drug-related items properly labeled by ei-

ther a pharmacist or a wholesale

druggist. The restrictive language prohibit-

ing educators from serving on the Board

of Pharmacy had disappeared, but no

mention of educational qualifications

for the practice of pharmacy had been

53. Nipgen, op. cit., 45. At the time,

the Pharmaceutical Examining Board of Cincinnati also

required graduates of the Cincinnati

College of Pharmacy to take an examination before ad-

mitting them to practice, an unusual

local extension of the 1873 law. Freking, op. cit., 418.

54. John A. Nipgen, "Report of the

Committee on Pharmacy Laws," Proceedings of the Ohio

State Pharmaceutical Association, 5 (1883), 36. "Your committee made every effort to

have

the bill again reported out of its

regular order, but without success," Nipgen reported.

"Considering all the disadvantages

they labored under, they see no cause for discouragement,

but urge the continuance of effort,

believing that success will surely follow."

55. D. C. Peters, "President's

Address," ibid., 12-13. Peters urged the Committee on

Pharmacy Laws to incorporate "a

provision exempting the regular graduates of accredited

colleges of pharmacy from the

contemplated examination by the State Board," but his recom-

mendation did not find favor among the

membership. See R. G. Williams, John Ruppert, and

M. D. Fulton, "Report of the

Committee on the President's Address," ibid., 40.

56. Philip H. Bruck, "Ohio Board of

Pharmacy," Proceedings of the Ohio State

Pharmaceutical Association, 6 (1884), 31. Nipgen's Committee on Pharmacy Law had

appar-

ently made peace with the Cincinnati

College of Pharmacy, which, "under the leadership of

Professor [John Uri] Lloyd, changed its

enmity into friendship, and its opposition into an earnest

and hearty support." John A. Nipgen, "Committee on Pharmacy

Laws," ibid., 29.

Significantly, the new Board also

included Edward S. Wayne, M.D., Professor at the Cincinnati

College and member of the Cincinnati

Pharmaceutical Examining Board. See Freking, op. cit.,

418-19.

Pharmaceutical Education

59

included.57 Nevertheless, it

was enough. "We have great reason to congratu-

late ourselves on the success of the

passage of our pharmacy bill," President

S. S. West enthused at the May, 1884,

meeting of the Association in

Cincinnati. "The law as it passed

may be considered to be as good, if not bet-

ter, than that of any of our sister

States, although it may not exactly suit the

fastidiousness of some of the druggists

of the State."58 By the following

May, 3,953 pharmacists and assistant

pharmacists had been registered by the

Ohio State Board of Pharmacy, 214 of

whom had passed an examination;

ironically, the new law had already

survived a "tincturing of dissatisfaction"

among "certain ones" who

sought to amend or repeal the legislation.59

Association President John Weyer

provided some carefully worded support for

pharmaceutical education, but never let

his listeners forget who was in charge

of deciding upon the educational

qualifications of Ohio's pharmacists. "By

legislation we can enforce education and

restrict the practice to persons prop-

erly qualified," Weyer stated.

"By education we can most permanently and ef-

fectually elevate the standard and

improve the science and art of Pharmacy. It

is, then, our plain duty to encourage

education, or to enforce it if we must."60

Ohio Northern University. The significance of the new pharmacy practice

act had not been lost on the teachers

and administrators at the North-Western

Ohio Normal School at Ada. Shortly after

the bill had been signed into law,

President Henry S. Lehr reasoned that if

pharmacy apprentices and drug clerks

were to be examined for their competency

as practitioners they would cer-

tainly seek schooling in certain topics.

He hurriedly made it known that a

"Department of Pharmacy" would

offer courses to those interested in prepar-

ing themselves for careers in pharmacy,

perhaps as early as the fall of 1884.

President Lehr counted on drawing upon a

preparatory medical course that had

57. "An Act to Amend Sections 4405,

4406, 4407, 4408, 4409, 4410, 4411, and 4412 of the

Revised Statues of Ohio," General

and Local Laws and Joint Resolutions Passed by the Sixty-

Sixth General Assembly, LXXXI (Columbus, 1884), 61-65.

58. S. S. West, "President's

Address," Proceedings of the Ohio State Pharmaceutical

Association, 6 (1884), 13. West later introduced G. P. Englehard,

editor of the Chicago-based

trade paper The Druggist, who had

been instrumental in securing the passage of the Illinois

pharmacy practice act in 1881. Englehard

considered the new Ohio law "one which has no

superior, and one which might be copied

by other States with profit." G. P. Englehard,

"Address," ibid., 41.

59. Philip H. Bruck, "Ohio Board of

Pharmacy Report," Proceedings of the Ohio State

Pharmaceutical Association, 7 (1885), 26. The number also included 178 pharmacists

and as-

sistant pharmacists who had been

previously registered by the Cincinnati Pharmaceutical

Examining Board. Also see Geo[rge] L.

Hechler et al., "Committee on Pharmacy Laws," ibid.,

23. The dissatisfaction "was caused

by selfishness," Hechler reported, and while the opposi-

tion at first seemed "quite

formidable," it finally "resolved itself into a minority of

insignificant

proportions, which was overcome by

watchfulness and perseverance on [the] part of your

committee."

60. John Weyer, "President's

Address," ibid., 11. Weyer saw education as "a most sure

means of success."

60 OHIO

HISTORY

been organized two years earlier.61

By the fall of 1885, the "increasing de-

mands of students wishing to engage in

the study of Pharmacy" led the fac-

ulty of the newly renamed Ohio Normal

University to offer a "distinct course"

of study in theoretical pharmacy,

theoretical and practical chemistry, botany,

materia medica, toxicology, and

pharmaceutical preparations, the course itself

being extended over three terms of ten

weeks each.62 The new Department

graduated its first class of six

students in 1887. By that fall, the "wonderful

success" of the students had

induced the three-man faculty to "enlarge and

greatly extend the course" to forty

weeks, "making it second to none."63 An

"original thesis on some subject

relative to the subject of Pharmacy" was

added to the requirements for graduation

in 1889, and by 1894, pharmacy stu-

dents attending the lectures,

laboratories, and recitations at Ada could choose

between the one-year, forty-week course

leading to the degree of

"Pharmaceutical Graduate"

(Ph.G.) or an extended two-year course leading to

the degree of "Pharmaceutical

Chemist" (Ph.C.). The second forty-week year

could be divided into two twenty-week terms,

much of the work consisting of

elective courses.64

61. Charles O. Lee, "Early Years of

the Ohio Northern College of Pharmacy," The Ampul,

12 (Fall, 1961), 2; and

"Medical," Annual Catalogue of the Teachers and Students of the

North-

Western Ohio Normal School, and

Business College, for the School Year 1882-83, and

Announcements for 1883-84 (Ada, 1883), 26, Rare Books-Archives Room, Heterick

Memorial

Library, Ohio Northern University, Ada,

Ohio [hereinafter referred to as "Ohio Northern

Archives"]. Students pursuing the

preparatory medical course were "furnished the very best

opportunities in the study of Botany

[and] Chemistry as well as Anatomy and Physiology and

have the additional advantages of

pursuing literary studies if they wish."

62. "School of Pharmacy," Sixteenth

Annual Catalogue of the Teachers and Students of the

Ohio Normal University and Commercial

College, for the School Year 1885-86, and

Announcements for 1886-87 (Columbus, 1886), 30-31, Ohio Northern Archives.

Students en-

tering the new School were

"expected to have a good general knowledge of the common

branches." The name change had

taken effect the previous year, "owing to the request and

urging of many of our students."

See "History," Fifteenth Annual Catalogue of the Teachers

and Students of the Ohio Normal

University and Commercial College, for the School Year 1884-

85, and Announcements for 1885-86 (Columbus, 1885), 32, Ohio Northern Archives.

63. "Graduates of 1887:

Pharmaceutical" and "Department of Pharmacy," Seventeenth

Annual Catalogue of the Teachers and

Students of the Ohio Normal University and Commercial

College, for the School Year 1886-87,

and Announcements for 1887-88

(Cincinnati, 1887), 43

and 31, Ohio Northern Archives. The

original faculty included M. J. Ewing, M.S., who taught

theoretical and practical chemistry,

Charles S. Ashbrook, Ph.G., who taught theoretical and

practical pharmacy and materia medica

and toxicology, and J. G. Park, A.M., who taught

botany and microscopy.

64. "Department of Pharmacy:

Requirements for Graduation," Twentieth Annual Catalogue

of the Teachers and Students of the

Ohio Normal University and Commercial College, for the

School Year 1889-90 and Announcements

for 1890-91 (Columbus, 1890), 37, Ohio

Northern

Archives. The Department eliminated

"everything we do not consider absolutely necessary to

a complete and comprehensive knowledge

of practical, every-day pharmacy," thus saving its

students "at least one year's time

and expense." Ibid., 35. A provision exempting students who

passed the State Board of Pharmacy

examination from their final examinations in the

Department was reversed the following

year. See "Department of Pharmacy: Requirements

for Graduation in This Department,"

Twenty-first Annual Catalogue of the Teachers and

Pharmaceutical Education 61

The University itself, which had started

out as a proprietary venture in

1871, became affiliated with the

Methodist Episcopal Church in 1898.

Believing that "there can be no

true education where the moral and religious

natures of the students are

neglected," daily attendance at chapel was expected

and students were strongly encouraged to

seek room and board with the citi-

zens of Ada, dormitory living being

considered "not conducive to good man-

ners, health, or morality." The

University assumed its present name, Ohio

Northern University, in 1904.65 Although

the University itself became ex-

tremely conservative under its new

administration, the Department of

Pharmacy continued to pursue a

remarkably vigorous program, graduating

over 1,044 students during the first

twenty years of its existence, adding an

optional "Pharmaceutical

Doctor" (Pharm.D.) degree in 1906 for graduates of

its two-year program. The new program

required an additional twenty weeks

of work "specializing on formulae

and assaying of crude drugs," but there is

no record of the degree ever being

conferred.66

Students of the Ohio Normal

University and Commercial College, for the School Year 1890-91,

and Announcements for 1891-92 (Akron, 1891), 42. Also see "Department of

Pharmacy:

Special Course: Degree of Pharmaceutical

Chemist," Twenty-fifth Annual Catalogue of the

Teachers and Students of the Ohio

Normal University and Commercial College, for the School

Year 1894-95, and Announcements for

1895-96 (Ada, 1895), 49-50, Ohio

Northern Archives.

The Catalogue stressed that the

Department's diploma was "accepted in lieu of the first year's

lectures by the leading medical

colleges." "Department of Pharmacy: Advantages," Twenty-

fourth Annual Catalogue of the

Teachers and Students of the Ohio Normal University and

Commercial College, for the School

Year 1893-94, and Announcements for 1894-95 (Akron,

1894), 47, Ohio Northern Archives.

65. W[illiam] O[xley] Thompson,

"Ohio Northern University, Ada, Hardin County, Founded

1871," in Burns, op. cit., 353.

Lehr "sought to make the school an open opportunity to all

classes at all times," Thompson

noted. "The result was that many hundreds found the Ohio

Normal University an open door when

other schools were closed to them." Also see "Home

Care and Comfort," Twenty-Ninth

Annual Catalogue of the Trustees, Teachers and Students of

the Ohio Normal University .. . for the School Year, 1898-99 and Announcements for

1899-

1900 (Ada, 1899), 8; and "Moral and Religious

Culture," Thirty-fourth Annual Catalogue of the

Teachers and Students of the Ohio

Normal University and Commercial College, for the School

Year 1903-04 and Announcements for

1904-05 (Ada, 1905), 6, Ohio Northern

Archives. The

extreme conservatism of the University

was reflected in the attitudes of its students even be-

fore the institution became

denominational. In 1890, a lay magazine reported the sight-unseen

purchase and subsequent unveiling of a

nude statue of Apollo, which caused "wild screams

and a precipitate scattering of the

students who fled in all directions, leaving the god master of

the situation." The students

responded by sewing a pair of fine velvet knee breeches to clothe

the offending statue. Quoted by Mary

Cable in American Manners and Morals (New York,

1969), 271.

66. "College of Pharmacy: Special

Courses," Thirty-sixth Annual Catalogue, Ohio Northern

University: The Trustees, Teachers

and Students for the School Year 1906-07, with the

Announcements for 1907-1908 (Ada, 1906), 5-6, Ohio Northern Archives. Candidates for

the

degree were required to be twenty-one

years of age, a high school graduate, and a graduate of

Ohio Northern's College of Pharmacy, as

well as having completed "four years of practical

experience in a store where

prescriptions are filled." Also see Lewis C. Benton and Charles

O. Lee, "The Early Years of the

Ohio Northern University College of Pharmacy-II," The

Ampul, 14 (Spring, 1964), 14; and Charles O. Lee, "The

Early Years of the Ohio Northern

University College of

Pharmacy-III," The Ampul, 15 (Fall, 1964), 6.

62 OHIO

HISTORY

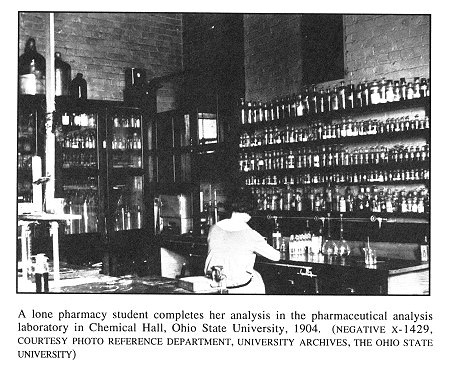

This rejection of an early attempt to

proffer a professional doctorate in

pharmacy may be seen as a realistic

assessment of the pharmaceutical tenor of

the times. The Ohio State Board of

Pharmacy did not require one year of high

school as a prerequisite to a required,

two-year graded course of instruction of

not less than twenty-six weeks per year

until 1905; given this perspective and

the self-assured, even antischolastic,

attitude of the Ohio State Pharmaceutical

Association, the decision by the Ohio

State University in 1886 to launch a

demanding and pioneering three-year

course leading to the Ph.G. degree must

have been seen by practitioners as

daring, if not foolhardy.

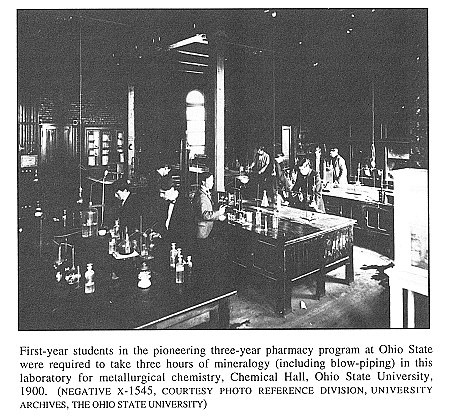

Ohio State University. While the founding of formal instruction in phar-

macy at Ohio State University in 1885

was also related to the passage of the

Ohio pharmacy practice act, the impetus

for pharmacy instruction at Ohio

State came from within the faculty of

the University. One faculty member in

particular laid the groundwork for the

College of Pharmacy at Ohio State:

Professor Sidney A. Norton, M.D., Ph.D.

Norton was serving as acting professor

of physics at Union College in New

York when he was one of seven men called

to constitute the first faculty of

the Ohio Agricultural and Mechanical

College in 1873. As Professor of

General and Applied Chemistry, Norton

was a physician-chemist of unusually

wide interests who had studied chemistry

in Bonn, Leipsic, and Heidelberg,

and would have been aware of the

European tradition that closely linked

pharmacy and chemistry in practice and

in the universities.67 At Ohio State,

this linkage was explicit from the very

first days of instruction.

For the first two years, all students

were required to take a prescribed course

of study that included a full year of

general chemistry, taught mainly by lec-

tures and recitations, and covering

inorganic chemistry, organic chemistry,

and "applications of Chemistry to

the Arts." A "special course" in chemistry

extended through two additional years,

and covered qualitative and quantitative

analysis, the latter of which included

"special studies in Chemistry applied to

Pharmacy, to Agriculture, to Manufactures,

and to the Arts."68

Norton himself was a stern but dedicated

teacher who demanded the best

67. Alexis Cope, History of the Ohio

State University, Vol. I, 1870-1910, edited by Thomas

C. Mendenhall (Columbus, 1920), 66-67.

Norton received his A.B. and A.M. degrees from

Union College in 1856 and 1859, his M.D.

from Miami Medical College in 1869, his Ph.D. from

Kenyon College in 1878, and his LL.D.

from Wooster University in 1881. Norton had served

as an instructor in natural science in

the Cleveland High Schools (1857-66), teacher of natural

science at Mt. Auburn College (1866-72),

and professor of chemistry at Miami Medical

College (1867-72) before returning to

Union College in 1872 as acting professor of physics.