Ohio History Journal

MARVIN FLETCHER

War in the Streets of Athens

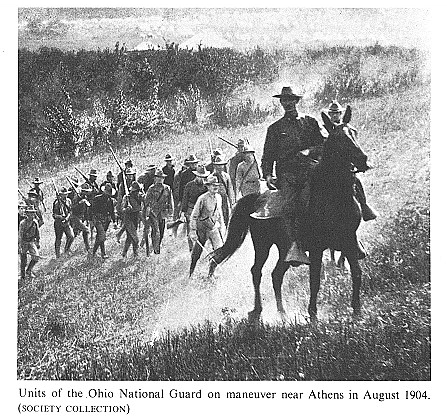

On an August evening in 1904 terror

struck the citizens of the small

southeastern Ohio town of Athens.

Thousands of Ohio National Guard

and regular army troops were on joint

maneuvers in the area. On the

evening of August 19 some of the

regulars marched into town with

the aim of freeing one of their comrades

who had been arrested by

some national guardsmen and locked in

the county jail. When the mil-

itary police tried to stop them, the

regulars fired their pistols. After

the smoke cleared, no regulars were

visible, but four bodies lay upon

the street. Beside them lay an army hat

with the red band of the field

artillery and the number fourteen on it.

For many soldiers mock war-

fare had become all too real.

This incident took place at a time of

transition and tension in the

relationship between the regular army

and the national guard. Influ-

enced by the ideas of Emory Upton, an

American military theorist

who sought to model the U.S. Army along

Prussian lines, most pro-

fessional officers of the regular army

considered the volunteer militia

units of the national guard poorly

trained and militarily useless. Sup-

porters of the guard, organized into the

politically influential National

Guard Association, held that the concept

of the citizen soldier was an

intrinsic part of American democracy.

Moreover they argued that

guard units had proved their military

efficiency almost equal to that of

the regular army during the recent

Spanish-American War.1

This debate was never fully resolved,

but a compromise of sorts

was worked out when army-guard relations

were reorganized in the

years immediately following the

Spanish-American War. One of the

strongest and most influential

supporters of the guard was Ohio

Congressman Charles W. Dick, himself a

major general in the state

Marvin Fletcher, Associate Professor of

History at Ohio University, wishes to thank

John Keifer, J.D., for help in unraveling

the legal complexities of the cases which

grew out of the Athens riot.

1. Russel F. Weigley, History of the

United States Army (New York, 1967), 275-78.

406 OHIO HISTORY

militia.2 Working closely

with Secretary of War Elihu Root, the Na-

tional Guard Association and the

congressional military committees,

Dick shaped a militia reform bill in

1903 which forced upon the

regular army greater recognition of

state guard units. Under the new

law, popularly known as the Dick Act,

the guard was to be considered

not merely a manpower reserve for the

regular army but a real second

line of defense. The federal government

issued arms and equipment to

the guard without charge, and in return

guard units had to hold at

least twenty-four drills or target

practice periods a year, plus a sum-

mer encampment of not less than five

days in the field. Additional

funds were specified for those state

troops that trained at regular

army camps. The Dick Act forced guard

and army to work together,

but this mandatory cooperation did not

lessen the historic antagonism

of the two groups.

Given the impetus of the 1903

legislation and the role of Major Gen-

eral Dick, the Ohio guard tried hard to

improve its skills. In 1904 the

governor asked the War Department to

allow the guard to join a regu-

lar army training camp, as a small group

had done the previous year

during maneuvers at West Point,

Kentucky. When his request was

denied, the national guard pursued an

alternate course. For the first

time the whole state guard went on

maneuvers and invited a few reg-

ular army troops to join them. In late

August field exercises were

held in the hills of southeastern Ohio

and the troops were housed in

three camps near Athens. Camp Armitage,

named after a nearby

railroad station, was located about

three miles from town and was

close to the Hocking River. The First

Brigade, which included the

First, Second, Third, and Sixth

regiments of the guard, as well as

the Ninth Battalion, a black unit, was

stationed there under the com-

mand of General William V. McMakin.

These guardsmen were joined

by the regular army First Battalion,

Twenty-Seventh Infantry; Troop

L, Fourth Cavalry; and the Fourteenth

Battery, Field Artillery.

Nearby was Camp Herrick, the

headquarters of the guard during the

maneuvers. Governor Myron T. Herrick,

after whom the camp was

named, as well as General Dick, stayed

there during the war games.

Furthest away from Athens was Camp

Beaumont, where the Fourth,

2. Charles Dick was born in 1858 and

served in the Spanish-American War. He

was a member of the House of

Representatives from 1898 to 1904, when he was ap-

pointed to fill the vacancy caused by

the death of Senator Marcus Hanna. He re-

mained in the Senate until 1911.

3. Jim Dan Hill, The Minute Man in

Peace and War: A History of The National

Guard (Harrisburg, 1964), 184-89; Louis Cantor, "Elihu

Root and the National Guard:

Friend or Foe?" Military

Affairs, XXXIII (December 1969), 361-73; U.S., Congress,

Report of the Secretary of War, 1904,

58th Congress, 3rd session, 1904,

28-30.

Incident in Athens

407

Fifth, Seventh, and Eighth infantries

were posted. They were joined

by three regular army detachments of the

same size as those regulars

stationed at Camp Armitage. Camp

Beaumont was under the com-

mand of General John C. Speaks.

Altogether there were about 7,000

national guardsmen and regular army

troops encamped near Athens.4

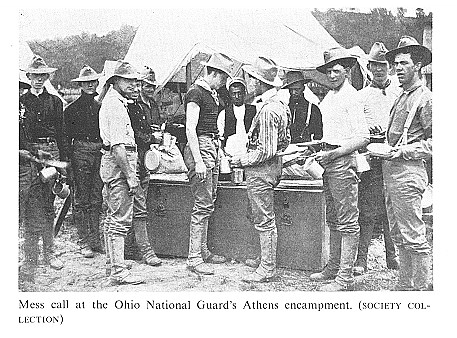

For many Athens area residents the

maneuvers were like a large

carnival. The Athens' railroads ran

excursion trains out to the camps

many times during the day. It cost ten

cents to ride to Camp Herrick

and fifteen cents to travel to Camp

Beaumont. Others used their car-

riages and rode out to view the soldiers

whose firing of blank ammu-

nition during the maneuvers gave them a

realistic flavor. A review

of all the troops on Sunday highlighted

the war games for civilian

onlookers.5

No one foresaw any problem controlling

the soldiers during their

off-duty time. General Dick felt that

because of the distance of the

camps from the city and the arduous

nature of the maneuvers, the

men would want to remain in their camps

in the evening. To be safe,

however, precautions were taken.

Officers searched the men and

confiscated any unauthorized weapons and

live ammunition. This

reduced the potential for shooting

incidents at the camps, but there

remained the problem of soldiers

disrupting nearby Athens. On Au-

gust 16 the national guard set up a

military police, or provost guard,

to patrol in the town. Passes were

issued "only in cases of absolute

and urgent necessity," and anyone

without one was arrested.6

Despite these precautions, some soldiers

did slip into town. These

visits to Athens led to fraternization

and friction between guardsmen

and regulars. The regulars felt

themselves militarily superior to the

Ohioans and resented orders given them

by the guardsmen, especially

those on provost guard duty. Friction

increased during the first few

days of the exercises, and small

incidents grew in significance. In one

incident a drunken regular lost his side

arms and accused the provost

guard of taking them. On another

occasion fifty regulars tried to run

the guard lines; it was not until the

provost guard fixed their bay-

onets that the regulars retreated. One

reporter commented that the

4. Ohio, Annual Report of the

Adjutant General to the Governor of the State of Ohio

for the Fiscal Year Ending November

15, 1903, 5; Ohio, Annual Report of

the Adju-

tant General to the Governor of the

State of Ohio for the Fiscal Year Ending November

15, 1904, 6-7, 25 (hereafter cited as 1904 Report); Athens

Messenger, August 18, 1904.

5. Athens Journal, August 18, 1904; Messenger, August 18, 1904.

6. Orders, Ohio National Guard, August

15, August 16, 1904, contained in Records

of the Adjutant General's Office, Record Group 94, National Archives (hereafter cited

as AGO).

408 OHIO HISTORY

feeling between the regulars and the

guardsmen "can hardly be classed

as cordial."7 In this

situation, it took only a small spark to set offa major

conflagration.

That spark was supplied with the arrest

of a member of the Four-

teenth Battery, Field Artillery, Private

Charles Kelly, on the afternoon

of August 19. Kelly resisted arrest,

firing his pistol at the provost

guard. The fact that Kelly had some

illegal ammunition, despite the

many searches, should have alerted the

officers that trouble was pos-

sible. The provost guard bound him hand

and foot and put him in the

county jail. Quickly the rumor reached

Kelly's regular army com-

rades at Camp Armitage that the guard

had clubbed him into insensi-

bility.8 That afternoon he

was visited by one of his comrades, Edward

Plumb. About eight o'clock that evening

a group of eighty to one hun-

dred soldiers crossed the Hocking River

on the railroad bridge,

brushing aside the small guard there.

They marched into the city,

down Court Street and turned right onto

Washington Street.

Near the jail the mob of regulars came

face to face with the eight

national guardsmen who constituted that

evening's provost guard.

The military policemen, all from the

Fifth Infantry, blocked the street.

After hesitating an instant, the

regulars began firing. Their shots

killed one man and wounded three others.

Charles Clark, a twenty-

four-year-old guardsman from Warren,

Ohio, due to be married in

two weeks, was killed by one bullet,

which went through both lungs

and cut the artery above the heart. The

rioters wounded Watson Ohls,

a salesman in civilian life, William

Blessing, a plumber, and Albert

Heald, a drayman.9 The only

visible piece of evidence was the hat of a

field artilleryman found on Washington

Street after the riot. 10 The in-

cident revealed that old enmities had

not been dissipated by the Dick

Act. Whether the culprits could, or

would, be brought to justice now

became the pressing issue.

Immediately after the shootings, Athens

Sheriff Andrew Murphy

telephoned the news to General Dick's

headquarters. Fearing more

trouble, he ordered the provost guard

reinforced with part of the First

Infantry. The provost guard worked with

the sheriff to clear the streets

and to close the saloons."

7. Journal, August 25, 1904; Cleveland Plain Dealer, August

18, 1904.

8. Messenger, August 25, 1904.

9. Ibid.; Certificate of Post-mortem Examination on Charles

Clark, August 25,

1904, Document File #914805, Records

of the Adjutant General's Office, Record Group

94, National Archives (all the legal

documents about this incident are in this file;

hereafter cited as AGO, Legal).

10. 1904 Report, 138.

11. Messenger, August 25, 1904; Plain

Dealer, August 21, 1904.

|

Incident in Athens 409 |

|

|

|

An investigation to find the guilty parties began immediately. Gen- eral Dick ordered each unit to conduct a roll call to see who was miss- ing. A guard line was placed around the camps to check returning soldiers for arms and ammunition and examine their hands and faces for the presence of powder stains. Those men from Camp Beaumont picked up in this way were not implicated in the riot, for the officers believed that the camp was too far from Athens for the men to have participated in the fracus. However, those caught by the dragnet at Camp Armitage, closer to town, were prime suspects. These soldiers, both national guardsmen and regulars, were the center of the subse- quent civilian investigation.12 The riot placed the War Department in a great dilemma because

12. W. T. Duggan to Adjutant General, Department of the Lakes, August 24, 1904, Document File #1135832, Records of the Adjutant General's Office, Record Group 94, National Archives (this file is the Brownsville Consolidation File; hereafter cited as AGO, Brownsville); 1904 Report, 130. |

410 OHIO

HISTORY

the incident threatened the fragile

working relationship between the

guard and the regular army. While

supporters of Emory Upton would

not have been sorry to see the new

relationship to the guard come to

an end, the incident was also

embarrassing because it was regular

army troops, not raw guardsmen, who were

apparently guilty of whole-

sale indiscipline. In this situation the

army temporized. They did not

launch their own investigation, but they

gave some help to that con-

ducted by the Athens

civilian-authorities. Adjutant General Fred C.

Ainsworth immediately telegraphed

Governor Herrick that the officers

at Athens were instructed "to cooperate

in fullest measure with civil

authorities."13

The shooting incident was not soon

forgotten. Though the man-

euvers resumed, the mimic war seemed to

take a back seat to the

real one. Several days after the fight,

some men from the First Infan-

try were bathing in the Hocking when

they found the body of a soldier

drifting in the water. The man was

identified as Corporal Malcolm

Nelson, a member of the Fourteenth

Battery, Field Artillery.14 The

time and place of Nelson's death seemed

to indicate that he was in-

volved in the disturbance in Athens. A

great deal more was revealed

at the coroners inquest. Frank Hendley,

a physician, testified that the

cause of death was "heart failure

produced by the cold water striking

him when heated" and County Coroner

J. J. Lane ruled that Nelson

died by drowning. The cartridges and

pistol found on the body were

the kind issued to artillerymen and it

was subsequently learned that

the hat found in town after the

shootings belonged to Nelson.15 The

evidence suggested strongly that Nelson

had been involved in the riot

and had died while trying to swim the

Hocking and get back to camp.

Leading the subsequent search for the

guilty soldiers was Israel

M. Foster, an ambitious, liberal-minded

young lawyer in his first term

as Prosecuting Attorney for Athens.l6

Foster and Lane went to both

Camp Armitage and Camp Beaumont the

Monday after the shooting.

Gathering evidence through a close

questioning of a number of men,

the investigators came to the conclusion

that soldiers from a number

13. Plain Dealer, August 21,

1904; Fred C. Ainsworth to Myron Herrick, August

22, 1904, AGO, Brownsville.

14. Messenger, August 25, 1904;

W. C. Mabry to Commanding Officer, Camp Armi-

tage, August 22, 1904, AGO, Legal.

15. Testimony Taken at

Coroner's Inquest Over the Remains of Corporal Nelson,

Deceased, Athens, Ohio, August 22,

1904, AGO, Legal; 1904 Report, 138.

16. Israel Foster was born in Athens in

1873. He received a bachelor's degree from

Ohio University in 1895 and a law degree

from Ohio State University in 1898. After

eight years as prosecuting attorney,

Foster served six years in Congress, from 1919 to

1925. He was a strong advocate of child

labor legislation.

Incident in Athens 411

of units, both national guard and

regular, were involved in the shoot-

ing. Since most soldiers denied any

knowledge of the affair, their prob-

lem became how to place any particular

soldier at the riot scene.l7 At

the coroner's inquest into the death of

Charles Clark, Foster got a

break. John Baydos, a member of the

Fourteenth Battery, admitted

going into town and taking part in the

riot. He named four others

from the Fourteenth Battery who were

present at the riot: John Lott,

Harvey Snyder (a sergeant), Fred Thuler,

and William H. Raymond. But

he refused to name any others he had

seen, saying "The others that

went down don't want to tell they were

there."18

When the inquest reconvened two days

later, some of the witnesses

changed their earlier testimony and now

admitted their presence at

the riot scene. As the result of the

urging of Lieutenant John W.

Corey, one of the Fourteenth Battery's

officer's, Fred C. Thuler and

William Caligan now asserted that they

too had been in town and

had seen a number of their fellow

artillerymen in the mob. With this

evidence, Foster arrested James Duffy,

William Raymond, and the

three admitted rioters, Gaydos, Thuler

and Caligan. Bond was set at

$2,500 and they remained in jail until

the preliminary hearing in mid-

September.19 Raymond and

Plumb were veteran soldiers, the rest more

recent enlistees.20

Foster continued to feel that there were

more involved than the

five he had arrested. Within the week he

had new evidence, but un-

fortunately it did not bring him any

closer to his goal. He received a

letter from the commander of the First

Infantry, Charles Hake, Jr.,

informing him that one of his soldiers

had heard Trumpeter Edward

Plumb encourage the men to leave camp:

"He (Plumb) addressed the

assembled men to force their way past

the guard at the bridge." Hake

also reported that a number of his men

told him that the mob leaders

said, "we are going to clean out

the officers of the guard."21

Foster now redoubled his efforts to get

more evidence out of his

soldier prisoners. He wrote General John

C. Bates, commander of

the army's Department of the Lakes, that

those in custody were

afraid to talk because they feared that

their comrades would murder

them. Foster asked for the cooperation

of the army in getting the

regulars to tell all they knew. He

suggested that maybe a promise of a

transfer out of the battery would induce

the soldiers to talk. Appar-

17. Foster to W. Duggan, August 23,

1904, AGO; Messenger, August 25, 1904.

18. Testimony Taken at the Coroner's Inquest over the Remains of Charles

Clark,

Deceased, Athens, Ohio, August 20,

22, 23, 1904. AGO, Legal.

19. Messenger, August 25, 1904.

20. Service Records, William Raymond,

Edward Plumb, AGO.

21. Charles Hake, Jr., to Israel Foster,

August 24, 1904, AGO, Legal.

|

412 0HI0 HISTORY |

|

ently General Bates felt that this request was justified, for he notified Foster that he had asked the War Department to transfer any of the soldiers who agreed to this idea. Foster showed this telegram to the soldiers and it was enough to convince Caligan, Thuler, and Gaydos to turn state's evidence.22 Gaydos said that about half the mob was from the field artillery, while the other half was from the Twenty- seventh Infantry. Caligan stated that he saw John Johnston first shoot in the air and then lower his pistol and aim it toward the provost guard. With this evidence in hand, Foster asked the army to turn over

22. Foster to W. Duggan, August 23, 1904; Foster to John C. Bates, August 26, 1904; Bates to Foster, August 28, 1904, AGO; Foster to Grosvenor, December 31, 1904; AGO, Brownsville. |

Incident in Athens 413

to him Lott, Snyder, Barnett, Johnston,

Plumb, Pearson, and George

Davison.23 Six of these men

had been named in the affidavits, men-

tioned in the evidence obtained from

Captain Hake, or testified about

at the Clark inquest. The army confined

these men at Fort Sheridan

but did not immediately send them on to

Athens for trial.

Foster also asked the help of the Ohio

National Guard in his at-

tempt to gather more evidence. Guard

officers were requested to for-

ward "any evidence that they may

have heard of in their various com-

mands concerning the trouble in

Athens,"24 and Foster began to

receive new information quickly. A

number of men in the Sixth Infan-

try made written statements about events

at the beginning of the riot.

For example, John Lang was one of the

three members of the provost

guard on the railroad bridge near Camp

Armitage on that Friday

night. He stated that about dusk a group

of fifty to sixty men ap-

proached the bridge. When challenged,

two of the men came forward

and asked the guards to let them

through. Refusing, the guards de-

manded to see their passes. The group

then advanced and pushed the

three men out of the way. Unfortunately

for Foster, Lang could not

identify any of the men he saw that

night. Sergeant Clyde Shively was

in town that Friday night and saw the

mob as it marched up Court

Street. Quartermaster Sergeant Charles

E. Huddleston, First Infantry,

was in a saloon on Court Street and

heard several men of the Four-

teenth Battery drinking and planning

trouble. One man was loading

his revolver, while another said,

"Let's go now." The third man re-

plied, "No, let's wait until the

other men come, they'll be here soon."25

While the national guard seemed to

cooperate with Foster, the

army was less accommodating. Reluctant

to send the seven suspects

to Athens, the army ordered Major

Blanton Winship, Judge Advocate,

to first interview the suspects who were

confined at Fort Sheridan

and then to proceed to Athens and

investigate the situation. Winship

reported that the three prisoners in

Athens had made statements

implicating the other seven. He also

noted that there was a great

deal of hostility against the soldier

prisoners and that they needed to

be represented by "good

counsel" when they came to trial.26

Winship's recommendations were promptly

carried out. The army

ordered him back to Athens to observe

the trial and defense of the

23. Affidavits of John Gaydos, Fred

Thuler, and William Caligan, August 30, 1904,

AGO, Legal.

24. Foster to Critchfield, August 26,

1904, AGO, Legal.

25. Statements of John Lang, Clyde

Shively, Calvin Snyder, Charles Huddleston,

AGO, Legal.

26. W. Duggan to Military Secretary,

September 1, 1904, AGO, Brownsville.

414 OHIO HISTORY

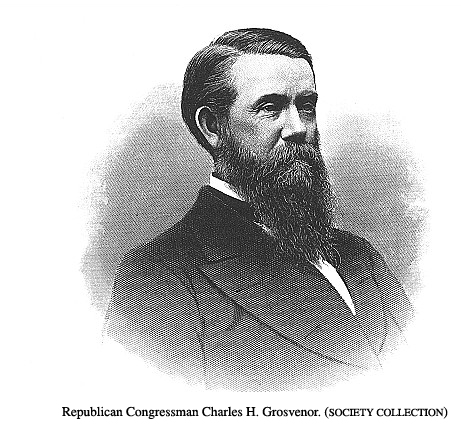

accused soldiers. This decision greatly

upset both Foster and Con-

gressman Charles H. Grosvenor, a

conservative Republican congress-

man and power in Athens politics.27

Foster thought that the army was

giving him "a great deal of

trouble," while Grosvenor claimed that

the appointment of Winship was part of a

government attempt to

"prevent an ascertainment of who

the murders were." He argued

that Winship had first come to Athens in

the guise of an observer and

had been shown all of the prosecution's

evidence. Now, claimed Gros-

venor, he was coming back as a defense

attorney, already armed with

the ammunition of the other side. In

defense of the action, Secretary

of War William Howard Taft later wrote

Grosvenor that "an enlisted

man is more or less a ward of the

Government, and if the Government

steps in merely to see that he is tried

according to law, it seems to me

that it is an exercise of a discretion

which the Government has."28

Despite the controversy, Winship was

present in Athens on Monday,

September 19, 1904, when Mayor Henry

Logan convened a prelim-

inary hearing in the case. Grosvenor

joined Foster in prosecuting the

soldiers while the defense was handled

by two local attorneys, James

P. Wood and Leonidas M. Jewett. Caligan,

who had turned state's evi-

dence, again described the riot and

named Plumb, Snyder, and John-

ston, Lott, Raymond, Barnett, Duffy, and

Davison as members of the

mob.29 Gaydos, another

prosecution witness, added Pearson's name to

the list of those members of the

Fourteenth Battery who were in the

mob. Thuler corroborated Caligan's

testimony. Mayor Logan, con-

vinced by the prosecution's case, ordered

the eight men held for the

November grand jury and set bond at

$3000 for each soldier.30

The November grand jury returned two

sets of indictments as the

result of the evidence presented. The

eight soldiers (Snyder, Lott,

Davison, Barnett, Johnston, Pearson,

Plumb, Raymond, and Duffy)

were charged with riot and conspiracy to

plan a riot. In addition, John

Lott was charged with assault with

intent to kill Warren Ohls. The

Athens Journal, upset that no one was indicted for killing Charles

Clark, reported "Life seems cheap

in Athens, when one man can be

27. Charles H. Grosvenor was a

conservative Republican and an ally of Joseph

Foraker who served in Congress almost

continuously from 1885 to 1907.

28. Foster to Florence Vangorder,

September 8, 1904, AGO, Legal; Grosvenor to

Taft, September 30, 1904, AGO,

Brownsville; Moorfield Storey quoting Taft to

Grosvenor in "Athens and

Brownsville" (extract from a speech before the Second

National Negro Conference), The

Crisis, I(1910), 13.

29. Testimony Taken at the

Preliminary Hearing Before Mayor Logan in the Case

of the State of Ohio versus James

Duffy, et al., Athens, Ohio, September 19, 1904,

AGO, Legal.

30. Ibid., Journal, September 22,

1904.

|

Incident in Athens 415 |

|

shot down on our streets, and no charges be made against the perpe- trators of these crimes."31 In the weeks before the men came to trial, Grosvenor reiterated his view that the army sought to avoid bringing the guilty parties to justice. He placed much of the blame for the riot on army officers who allowed the mob of soldiers to leave Camp Armitage, and he com- plained that the United States government had prevented evidence from being discovered and this in turn had led to the suppression of any murder indictments. To Secretary of War Taft, Grosvenor wrote "the conspiracy to shield the murders has been successful."32 The formal trials of those indicted began at the end of December. John Lott was the first person tried. The prosecution introduced a number of witnesses who saw someone striking Watson Ohls, but no one who could conclusively identify that assailant. The key prosecu- tion witness was William Caligan, who claimed that he saw Lott use his gun to strike someone's head. The defense tried to show that Lott

31. Messenger, November 17, 1904; Journal, November 17, 1904. 32. Grosvenor to Taft, December 19, 1904; Blanton Winship to George Davis, October 10, 1904; Davis to Taft, December 30, 1904; Taft to Grosvenor, December 23, 1904, AGO, Brownsville. |

416 OHIO HISTORY

was in camp during the shooting and that

Corporal Nelson had clubbed

Ohls.33 The jury deliberated

for three hours on the case and decided

that Lott was guilty of assaulting Ohls

and "of deliberate and pre-

meditated malice to kill." He was

sentenced to one year of hard labor

in the state penitentiary and fined the

costs of the prosecution,

$1227.07.34

Foster and Wood reached an out-of-court agreement

before the

start of the next trial. The jury would

be dispensed with; the trial

would be held before a judge; the

charges against Pearson and Davi-

son would be dropped; the defense agreed

not to contest the charges

against the remaining defendants. As a

result of this agreement the

trial moved along rapidly, in spite of

the prosecution's difficulty in

proving a charge of conspiracy. Defense

Attorney Wood noted that

the main prosecution witnesses, Caligan

and Thuler, gave "so con-

fusing" testimony that they would

not really help the state or hurt the

defense case.35

The six defendants were convicted of

causing a riot, but acquitted

on the charge of conspiracy. They were

given the maximum sentence

for their crime-one month in jail and a

$500 fine. The jail terms were

served in the Columbus Work House in

January 1905.36 The convic-

tions did not have an adverse effect on

the military careers of the de-

fendants. Lott was honorably discharged

from the army before the

trial. The others returned to the army

after their one month sentence

was over and served varying periods in

the Fourteenth Field Artillery

and other units. Snyder became a

Regimental Quartermaster Ser-

geant in 1910 and during World War I was

promoted to captain in

the Quartermaster Corps. Thuler was

honorably discharged while in

jail waiting to testify. Finally, after

many months of discussion the

chief prosecution witnesses, Gaydos and

Caligan, were transferred

to another battery in the field

artillery.

For Representative Grosvenor and other

Athenians, the outcome

of the trial proved immensely

frustrating. No one was brought to trial

for the murder of Charles Clark, while

those convicted of lesser

crimes served light sentences. Still

bitter about the affair two years

33. Testimony in the Case of the

State of Ohio vs. John L. Lott, AGO, Legal.

34. Ibid.

37. J. P. Wood to Taft, phone

conversation, December 14, 1906, AGO, Brownsville;

Journal, January 5, 1905; Testimony at Trial of Harvey M.

Snyder, et al., in the Court of

Common Pleas of Athens County, Ohio,

Indictedfor Riot, AGO, Legal.

36. Sentence in the Case of State of

Ohio vs. Harvey M. Snyder, et al., in the Court

of Common Pleas, Athens County, Ohio,

AGO, Legal.

Incident in Athens

417

later, Grosvenor commented that

"the whole encampment was filled

with factions and bitterness and

troubles of that character, growing

up almost necessarily between the

regular Army soldiers and the men

of the Ohio State Guard." He was

disillusioned because guardsmen

had been killed and the guilty parties

had not been found.37

The tensions involved in the guard-army

dispute virtually mandated

this unsatisfying outcome. The army's

inaction following the incident

is remarkable and can only be understood

in the context of the devel-

oping relationship with the national

guard. Interested parties here

were quite numerous. Old-line army

officers still felt it absurd to train

the guard to be like the regular army,

although others felt the Dick

Act had begun a process of integration

between the two which must

continue. In addition Congressman Dick

himself, a champion of the

guard, took a great deal of interest in

the case, as did Congressman

Grosvenor from an opposite point of

view. Given the complex situa-

tion, almost any positive action the

army took would antagonize

some group.

As a result the Army remained

essentially passive. Its officers did not

conduct any investigation into the facts

of the case. The War Depart-

ment merely turned the soldiers over to

the civilian prosecutor, sent

Major Winship to Athens as an observer,

and did little else. Upon

completion of their sentences, the

convicted soldiers returned to their

assignments. One of them eventually

became an officer. In the final

analysis, the army was cooperative but

certainly not helpful. A com-

parison between the army's reactions

here and those after the Browns-

ville Affair two years later is

instructive. There, with no National Guard

or Congressmen to worry about, the army

inspector general's office

launched an inquiry which lasted several

weeks and interviewed

more than one hundred soldiers in its

search for the black soldiers who

the local citizenry claimed had shot up

the town and killed a police-

man. Ultimately 159 soldiers were

dismissed from the army.38

Throughout the Athens disturbance, the

problem of improving re-

lations between the regular army and the

national guard provides the

key to understanding a puzzling affair.

The army's old hostility to-

ward the guard had made necessary the

Dick Act, which enforced coop-

37. U.S., Congress, House of Representatives,

Congressional Record, 59th Congress,

2nd session, January 9, 1907, 843-44.

38. Marvin E. Fletcher, The Black

Soldier and Officer in the United States Army,

1891-1917 (Columbia, MO, 1974), 123-26.

The N.A.A.C.P. later used the army's deci-

sion to defend the accused white

soldiers at Athens as evidence that racism motivated

the wholesale dismissal of the black

infantrymen at Brownsville. See The Crisis, I

(1910).

418 OHIO HISTORY

eration between the two, but the joint

maneuvers of 1904 were still

filled with tensions between the

parties. Regulars disdained guards-

men and would not tolerate having them

as military police. Trouble

was inevitable, though the shooting was

not. After the riot, the same

need to improve relations impelled both

sides to avoid a diligent

search for the guilty parties. Neither

branch of the military was eager

for a wide ranging, potentially

disruptive investigation. Despite Israel

Foster's best efforts, the origins and

solution to "the war in the streets

of Athens" lay far beyond the small

Ohio town.