Ohio History Journal

164 OHIO HISTORY

A key maneuver in Hayes's attempt to

implement his Southern policy

was the appointment of Frederick

Douglass as Marshal of the District of

Columbia--a move which seems to have

reconciled both white and black

to the Hayes administration.82 Hayes

himself chose to look upon the ap-

pointment of Douglass as symbolic of an

intention to upgrade the Negro

in the eyes of the nation.83 Douglass

caused quite a stir after a bare month

in office when he made a speech in

Baltimore on the state of race relations

in the District of Columbia. He said

that Washington represented "a most

disgraceful and scandalous contradiction

to the march of civilization as

compared with many other parts of the

country." On May 18, 1877, the

New York Times said that Douglass

had spoken the truth and that such

truth had been spoken about the nation's

capital many times before, "but

never by a man whose skin was

dark-colored, and who had been appointed

to office in the District.84 There was an

immediate hue and cry for Doug-

lass' removal from office, but Hayes did

not bow to these demands.

In early September 1877, the President

took a nineteen day trip into the

middle South, presumably to obtain a

personal view of the results of his

racial policy. He visited Ohio,

Tennessee. Kentucky, Georgia, and Virginia.

In spite of much in his mailbag that

should have dampened his optimism,

he pronounced his policy a success and

was jubilant upon his return from

the tour. He had been heartily received,

if not in the deep South, and he

noted triumphantly in his Diary: "The

country is again one and united!

I am very happy to be able to feel that

the course taken has turned out

so well."85 Throughout the

tour his theme was that of reunion between

northern and southern whites, universal

adherence to the war amendments,

and racial harmony. To a northern

audience he called his Southern policy

"an experiment" which the

failure of the last six years demanded.86 But

when he was in former enemy territory

(Georgia), he swore that his policy

was not dictated "merely by

force of special circumstances," but that he

believed it right and just.87 He

tried to convince the people of the North

and the Negroes of the South that he had

not abandoned the freedmen

and that their rights could be protected

without federal interference. Turn-

ing to the Negroes in his Georgia

audience he said:

And now my colored friends, who have

thought, or who have been

told that I was turning my back upon the

men whom I fought for, now

listen. After thinking it over, I

believe your rights and interests would

be safer if this great mass of

intelligent white men were left alone by

the General Government.

This last phrase brought cheers from the

crowd, but whether by white

or black was not disclosed.88 Six

months after the commencement of his

policy Hayes was convinced that the

Negro was safer in the South without

the protection of the federal bayonets,

which he had withdrawn.89 He chose

to believe that "the white people

of the South have no desire to invade

the rights of the colored people."90

In his first annual message he defended

his removal of the troops from South

Carolina and Louisiana as a "much

HAYES and RACE 165

needed measure for the restoration of

local self-government and the pro-

motion of national harmony."91

The President's heart must surely have

leaped for joy when he received

a letter from Wade Hampton of South

Carolina, reassuring him of his in-

tentions to protect the Negro in his

rights and to coexist with Republi-

cans. But even here Hampton reported

that he was having trouble with

dissident members of his own party:

"My position here has been a very

difficult one, for besides the

opposition to me from political opponents, I

have had to meet & control that of

the extreme men of my own party."

If that were not enough to awaken Hayes

from his optimistic stupor, a

newspaper clipping which Hampton sent

him should have been sufficient.

The article called Hayes's attention to

the "Straight-Out Democrat" who

wanted nothing to do with Negroes or

Republicans, or southern whites

who fraternized with either.92

As soon as the midyear elections of 1878

drew near, the racial volcanoes

erupted again. According to a Negro

congressman from South Carolina,

the whites were again resorting to

violence and intimidation to prevent

Negro political participation. The

President could do nothing but lament

in his Diary that color was still

the hallmark of political division in South

Carolina: black Republicans and white

Democrats. He lamented, too, that

intelligence, property, and courage were

on the side of the whites while

the poor Negro was ignorant:93 "The

South is substantially solid against

us. Their vote is light ... A host of

people of both colors took no part . . .

the blacks, poor, ignorant, and timid

can't stand alone against the whites."

The "better elements of the South,"

in whom Hayes had placed so much

faith, were not organized. Only a party

division of the whites would im-

prove the situation but Hayes had no

definite plan to effect the change

and seemed reconciled to let nature take

its course.94 He had further cause

for dejection when he received a

thirty-signature petition from some Ne-

groes in Mississippi who wanted

financial assistance to emigrate to Kansas

to escape oppression.95 The

President could do nothing but report the un-

fortunate situation in the South to his Diary.96

Is it possible to render a final

judgment on the President's Southern

policy? The subject is a very

controversial one. Although he was aware

of its shortcomings, even after he left

the White House, Hayes never

doubted the underlying wisdom of his

Southern policy and that by it he

had allayed sectional and racial

bitterness in the face of strenuous opposi-

tion from both political parties.97

Contemporaries were more doubtful of

its success. A leading Radical

Republican, W. E. Chandler, felt that Hayes

had abandoned the white southern

Republican politician and the Negro

to the mercy of the

"redeemers."98 Frederick Douglass was grateful to the

man who had given him the highest office

held by a Negro in the federal

government up to that time, but later

accused Hayes of making a virtue

out of necessity.99 Others

reflecting on the past, pronounced the Hayes

policy a failure.100

166 OHIO HISTORY

Historians also have had their views on

the Hayes policy. John W. Bur-

gess said that Hayes's biggest struggle

with himself concerned the question

of whether he was deserting the black

man with his Southern policy.101

Charles Beard contended that

"President Hayes could not strike out boldly

had he desired to do so," because

he had to deal with a Democratic House

for four years and a Democratic Senate

for two years.102 On the other hand

there is no evidence to suggest that

Hayes showed any inclination to en-

force the laws already passed with

anything other than oral vigor.

Rayford Logan has judged President Hayes

rather harshly, accusing him

of abandoning the Negro, of complacency

in the face of the failure of the

South to live up to its part of the

alleged "bargain" in the compromise of

1877, and of aiding and abetting the

liquidation of the Negro from poli-

tics by suggesting qualified suffrage

based on education.103 Yet, all but

three of the southern states had fallen

to the "redeemers" before Hayes

took office. While the net result of the

Hayes policy was disfranchisement

of the Negro, it was fully ten years

after Hayes left office that the "redeem-

ers" felt sufficiently strong

enough to consummate their victory. The fail-

ure of Hayes to enforce the laws in

regard to civil rights should not be

construed as complacency or apathy on

his part. He certainly was concerned

about national impotence in this area.

However helpless to correct the

situation he may have felt, he by no

means viewed Negro disfranchisement

with indifference and approval. Logan

interpreted the President's sincere

concern for honest and efficient

government in the South as an indication

of his "approval of the curtailment

of the rights of Negroes by the resur-

gent South." Hayes did not suggest

education as a means of keeping the

Negro out of politics but as a vehicle

by which the Negro could ultimately

attain full citizenship.

Like most Presidents of this post-war

period, Hayes was either afraid or

unwilling to enforce the laws in regard

to the civil rights of Negroes. His

desire for white reconciliation and his

virtuous penchant for reform made

him unduly optimistic about the

likelihood of the southern whites protect-

ing Negro rights. What Professor Rubin

found to be true of the former

President Hayes during his tenure with

the Slater Fund [1881-1887] might

well apply to his presidency with

special reference to the Southern policy:

He was unduly optimistic in the face of

the repeated onslaughts of south-

ern white supremacy which sought

relentlessly during this period to push

the Negro into political oblivion.104

What final observations can be made

about Hayes? He saw Negroes as

members of a "weaker" though

not necessarily inferior race. He was defi-

nitely conscious of race difference. But

still he looked to the eventual inte-

gration of Negroes into American life.

He preferred to leave social equality, a

necessary condition for legal race

mixing, to time and natural

inclinations. Hayes said that it was better left

alone until both races learned to live

by the Golden Rule. Nevertheless, in

a rare reference or two, he intimated a

disinclination toward forced inte-

gration and also gave the impression

that biologically he preferred to leave

HAYES and RACE 167

racially asunder what God and nature

obviously had not put together. Yet

there were times when he demonstrated in

his thoughts and actions that

democracy could transcend the color

line.

While Hayes was by no means immune to

political motivation, little

opportunism can be detected in his basic

outlook on race. On the other

hand, it is difficult to reconcile the

obvious change in his attitude toward

the South from the time he was a Radical

(on Negro rights) gubernatorial

candidate in Ohio in 1867 to the time

when his name was prominently

mentioned for the presidential

nomination. It may be that his changed at-

titude toward the South represented a

sincere disenchantment with Recon-

struction.

The idea that Hayes abandoned the Negro

for southern support cannot

be proved. His big error, if one wishes

to call it that, was that he trusted

the South to keep its promise to protect

Negro rights, in the absence of

federal interference. That there was an

explicit agreement to this effect

seems improbable, because Hayes had

already determined to make this

approach long before anyone could

possibly have known that the election

of 1876 would be disputed. He had become

disenchanted with Reconstruc-

tion as early as 1875. More than this, a

reading of the Hayes correspondence

disposes one to believe that at least

some of those southern Whigs were in

earnest when they made the proffer of

protection for the Negro. What

really happened, it appears, was that

the better class of whites, the so-called

"natural leaders" of the

South, made a promise which was not really with-

in their power to keep. As things turned

out, if seems that the promise was

made without the consultation or

approval of the "red-necked" and un-

washed constituency or its leaders.

Ironically it was the rise of southern

Democracy, its roots dug deep into the

bedrock of Negrophobia, that con-

stituted the high tide of white

supremacy which in the 1890's inundated

Whig, Bourbon, and Negro alike.

As President, the problem of race was

ever before Hayes. He had not

been long in the White House before

matters of race threatened to domin-

ate his thinking. His determination to

bring about a reunion between

northern and southern whites seemed to

immobilize his obligation to en-

force the laws in the face of an

ever-recalcitrant South. Hayes was more dis-

posed to use sweet persuasion than brute

force. It may be that the Presi-

dent was impressed by the advice of

those who told him that in any con-

test between the Negro and the

Anglo-Saxon, the black man was destined

to be defeated. The seeming futility of

the struggle for basic change of

attitude in the South may have deterred

him from trying to enforce the

law in a stubbornly unwilling section.

Had not President Grant already

tried as much, and failed?

THE AUTHOR: George Sinkler is As-

sociate Professor of History at Morgan

State College.

|

|

|

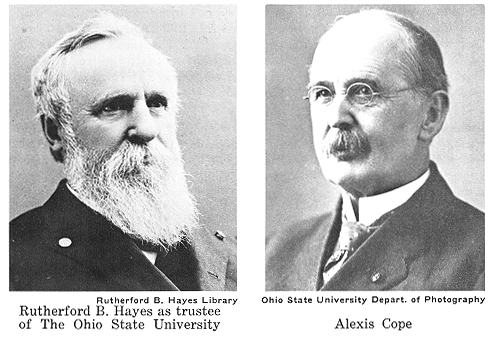

Rutherford B. Hayes and The Ohio State University by WALTER S. HAYES, JR. It was bitterly cold the day former President Hayes arrived in Cleveland in January 1893. He had come from Columbus and was in search of some- one to head the new manual training department for The Ohio State Uni- versity. Both as a member and as the president of the board of trustees he had been actively concerned with the establishment of a good manual training department for the institution. Snow fell and was blown by a wind that must have made the day seem even colder than the four to twelve degrees reported in the newspaper.1 Hayes did not let the weather keep him from his duties, but took a street- car and then proceeded by foot to University School where he had hoped to find the administrator the board was seeking. After staying overnight with his son Webb, he went to the train station Saturday afternoon, the fourteenth, for the return home to Fremont when he was suddenly stricken with a heart attack. Some stimulants were given to him in the waiting room, and against Webb's wishes he continued to Spiegel Grove where he died the following Tuesday.2 His long interest in the University had started when he became governor in 1868 and was still active at the time of his death. During the years he served as city solicitor, congressman, governor and president, Rutherford B. Hayes became familiar with many social prob- NOTES ON PAGE 206 |

|

HAYES and OSU 169 lems of the state and nation. After his presidential term he worked through private organizations to improve conditions in the United States in the fields of prison reform and education, especially Negro education and man- ual training.3 In the opinion of Governor Joseph B. Foraker this work made him an excellent choice for appointment to the board of trustees of The Ohio State University. Hayes had also been governor of Ohio, in 1870, at the time the original institution was founded under the name of the Ohio Agricultural and Mechanical College. At that time, he had appointed the first board of trustees, whose duty it was to locate the college, decide on the course of instruction, and choose the faculty. He is usually given little credit for his significant role in the founding of the University. The Morrill Act of July 2, 1862, provided the means for the various states to establish agricultural and mechanical colleges using the proceeds from the sale of public land. Each state was to receive 30,000 acres of land for each United States Senator and Representative, making Ohio's share 630,000 acres. Soon after passage of the act, interest was shown by the Ohio State Board of Agriculture, Governor David Tod, and others in taking advantage of the opportunity to start a college. Many times in the next seven and one half years, legislation supported by each new governor was formulated creating an agricultural and mechanical college. Each time efforts failed at some point. Western land did not sell well until the price was lowered in 1866. Also a number of cities and existing colleges wanted to share or totally acquire the funds and determine the location of the proposed college. By the end of the 1860's, however, most Ohioans agreed that the money should be used to establish one institution at a central location.4 |

170 OHIO HISTORY

In his first term, 1868-69, Governor R.

B. Hayes was as unsuccessful

as the previous governors in securing

legislation to establish the college.

The act of Congress of July 2, 1862,

specified that the states were required

to provide not less than one college

within five years in order to qualify

under the provisions of the bill. The

deadline had been extended five years

by Congress on July 23, 1866, but even

this time would expire soon.5

In his annual message of January 3,

1870, Hayes urged the Ohio General

Assembly to act quickly. He said that

Ohio had accepted the land grant

which had created the funds to establish

an agricultural and mechanical

college and warned that it must become a

reality on or before July 2, 1872.

He stated:

Much time and attention has been given

to the subject of the loca-

tion of the College. No doubt it will be

of great benefit to the county

in which it shall be established, but

the main object of desire with the

people of the State can be substantially

accomplished at any one of

the places which have been prominently

named as the site of the Col-

lege.6

This time the General Assembly responded

quickly. On January 12,

Representative Reuben P. Cannon of

Portage County introduced a bill

to establish and maintain an

agricultural and mechanical college in Ohio.7

The Morrill Act had specified:

The leading object shall be, without

excluding other scientific and

classical studies, and including

military tactics, to teach such branches

of learning as are related to

agriculture and the mechanic arts.

Hayes thought that the act should be

interpreted as broadly as it could and

that the best teaching facility possible

should result from it.8 The legis-

lature passed the Cannon bill on March

22, 1870, without limiting the

course of instruction. It left that

problem, along with those relating to the

location of the university and selection

of the faculty, to the trustees. The

act said that the governor should

appoint nineteen trustees, one from each

congressional district.

Hayes was interested in getting a board

of high quality and did not let

a man's views on politics or the ultimate

goals of the agricultural college

interfere with his appointments. Years

later, Thomas C. Mendenhall,

professor of chemistry at The Ohio State

University and editor of Alexis

Cope's History of The Ohio State

University, wrote, in the introduction

to the volume:

It was universally conceded at the time

that in the selection of the

members of the first Board of Trustees,

the men who were to deter-

mine the character and shape the policy

of the new institution, the

Governor (Rutherford B. Hayes) had shown

great wisdom, good judg-

ment and fairness to both sides of the

controversy (which had already

begun) as to whether it should be

"narrow" or broad and liberal in

its organization and sceme of

instruction .... Political affiliation had

been given little attention in making

the appointments and some of