Ohio History Journal

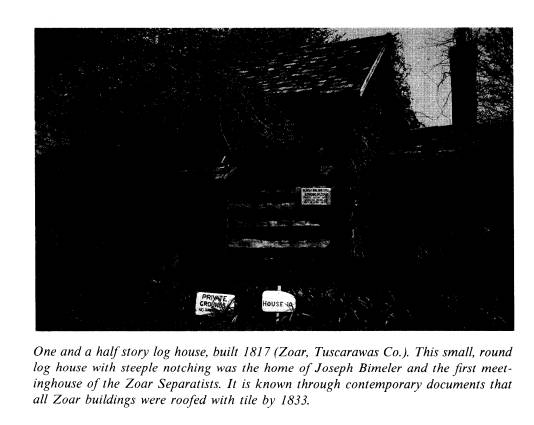

Log Architecture 173

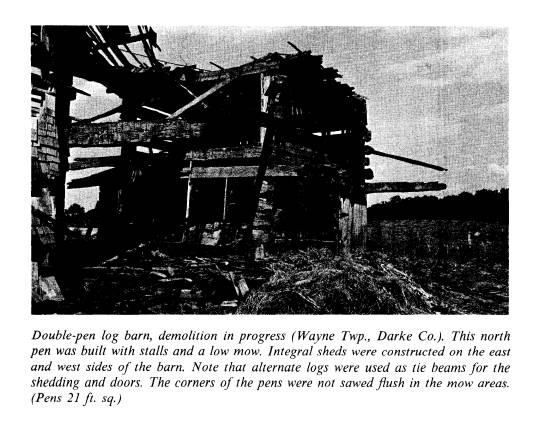

Author's Comments

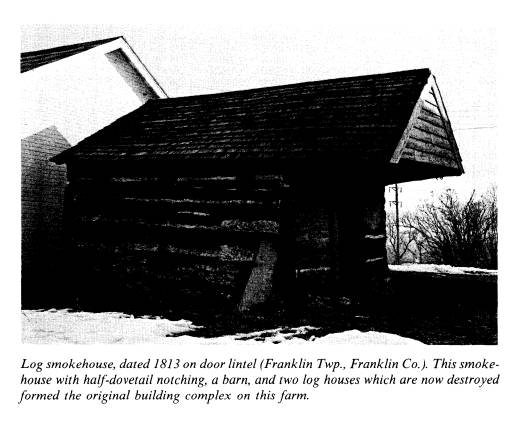

The material presented in this text is a

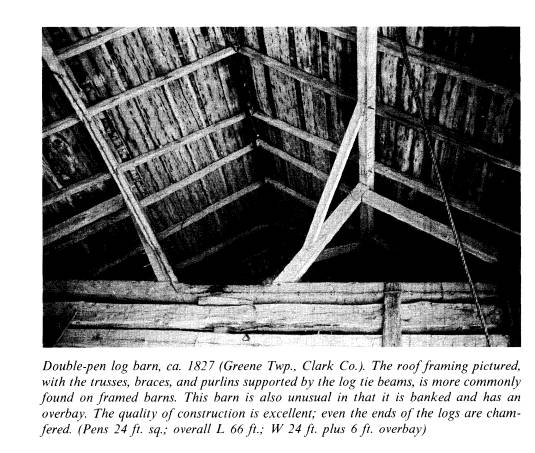

resume of six years of accumulating data

on log architecture in Ohio. It began as

a photographic study of extant structures

with no end in mind save the visual

recording of an almost extinct form of con-

struction. While working on various

research projects for The Ohio Historical So-

ciety, this writer filed for future

reference the numerous contemporary comments

on log construction which gradually came

to light. As the quantity of photographs

and notes grew, it became obvious that

enough data were available for a mono-

graph on Ohio log architecture. Perhaps

no typological, ethnological, nor archi-

tectural problems will be solved in the

succeeding pages, but the reader should

gain a firmer basis for judging the log

buildings that remain and should be able

to recognize that vast amounts of fiction

have been written and told about the

construction and use of such structures.

The author, as a student of historic

architecture, does not pretend to be capable

of recognizing specific details of

construction or design as indicative of certain cul-

tural or national typology. Also, time

simply was not available to measure, draw,

and analyze all the log buildings found

in Ohio. Except for the very early extant

buildings, however, it is doubtful that

any log house or barn remaining exhibits

unusual or significant features that an

architectural historian would be surprised

to see. If Ohio log architecture could

be viewed as an entity, an "Ohio" typology

might emerge. This could be proved only

by surveying log architecture and immi-

gration patterns in adjacent states. It

is likely that there is an "Ohio style," just as

there is probably an Indiana, Michigan,

or Kentucky typology. Only a minor amount

of such serious survey work has been

accomplished in the Midwest.

In order to relate Ohio log architecture

to log building throughout the world,

a background chapter on the history of

such construction is included here. Most

of this information came from C. A.

Weslager's excellent book, The Log Cabin in

America, which should be read by all persons interested in the

subject. That both

this monograph and Weslager's contain

some of the same references is due to the

fact that there are limited published

sources from which to draw. In this case the

common reference was the compendium of

eighteenth and nineteenth century

travel narratives entitled Early

Western Travels. Several of the narratives, particu-

larly of Indian captivity, to which

references are made are extremely rare and can

be found only in major libraries. The

library of The Ohio Historical Society has

an excellent collection of original

editions.

The county histories of Ohio contain

hundreds of references to log cabins and

houses. Unfortunately, many editors

copied the same sources, without giving credit,

when descriptions of a

"raising" were wanted. Such excerpts imply that the events

described took place within the given

county, which might be completely errone-

ous. For example, if the reader should

compare pages 212-14 of George F. Robin-

son's History of Greene County, Ohio (Chicago,

1902) with the chapter entitled

"The House Warming" in Joseph

Doddridge's book, Notes, on the Settlement and

Indian Wars, of the Western Parts of

Virginia & Pennsylvania from 1763 to 1783

(Wellsburgh, Virginia, 1824), he would

find that Robinson copied Doddridge's

account (probably from the 1876 edition)

word for word without giving credit.

This leaves a very unfortunate

impression, for Greene County, Ohio, in 1800 was

not necessarily like western

Pennsylvania some thirty-five years earlier. Also, Rob-

174 OHIO

HISTORY

inson misspells two critical words,

using "bunting poles" for "butting poles" and

"hard wood" for "heart

wood." Even without knowing the context a reader can

imagine the semantical difficulties such

changes pose.

Though county histories are of secondary

importance to the critical historian,

they nevertheless are one of the few

sources to record the oral traditions surround-

ing the ephemeral "frontier"

and the "cabin in the woods." Because commonplace

events make dull subject matter, any

unusual occurrence has tended to receive

more than its share of attention, which

in turn has colored the popular view of

Ohio history to such an extent that the

unusual event on the frontier has been

accepted as common to the life of each

settler. However, by the time of statehood

in 1803, the settlers, rather than

living under constant threat of danger from Indians

or animals, probably had an everyday

routine that was very monotonous.

Hopefully this monograph bridges the gap

between factual historic references

to log buildings and practical knowledge

on the construction and repair of such

structures. Authentic restoration of a

log house or barn is certainly possible. The

reader should be forewarned, however,

that the cost of materials alone can be

staggering. Ironically, the largest

expense is the logs. If logs had had such a value

150 years ago, the log building would

indeed be a rarity today!

The best approach for current

restoration, when a number of logs have to be

replaced, is to combine two or three

buildings. Split shakes can be obtained from

most lumberyards, at least on special

order; the "resawed" type is best. Sawmills

can supply board "off-falls"

for roof sheathing. The Tremont Nail Company of

Wareham, Massachusetts, still makes a

large variety of cut nails which are han-

dled by many firms; Horton Brasses of

Cromwell, Connecticut, is one supplier.

Good reproduction hardware is available

from a few sources; Ball and Ball of

Exton, Pennsylvania, is famous for its

line of reproductions. They can duplicate

hand-forged hardware on special order.

Several companies in Ohio are now making

"old pattern" bricks. Many

paint companies can supply stains and paints com-

parable to eighteenth and nineteenth

century colors: Bruning, Martin-Senour, and

Cabot, among others, offer a wide

selection. The McCloskey Varnish Company

makes a fine wood preservative and floor

stain. It is not the intention of the author

to endorse specific products or

companies. A wide selection of products suitable

for restoration work is available (with

the possible exception of hardware), and

often the only qualification governing a

choice lies in what is available in a given

locality.

Perhaps second only to obtaining the

logs is the difficulty in finding the correct

patterns of millwork for such items as

baseboards, chair and peg rails, door and

window trim, flooring, door and wall

paneling, mantels, and a seemingly endless

variety of other interior and exterior

trim. Good planing mills carry a full selection

of patterns, and the old bead and ogee

moldings are still available if the correct

shaper blades are used. Poplar and

walnut were the common finish woods of the

first half of the nineteenth century.

Today, unless a supply of walnut--or an un-

limited amount of funds--is on hand,

some substitute will have to be found. Strangely

enough, even common, inexpensive poplar

is difficult to obtain in Ohio. If the wood

is to be painted, as most interior trim

was, clear white pine is probably the best

choice on today's market. Even under

paint the grain in redwood can be undesir-

able, and the wood tends to sliver.

The problem of dating log buildings is

universal. The very few ca. 1800 build-

ings in Ohio do bear some

characteristics (such as eave beams and log gables) that

Log Architecture 175

would date them that early even if

literary evidence were not available, but the

majority of buildings are not

distinctive insofar as constructional details are con-

cerned. Adding to the difficulty of

dating is the fact that most of the extant houses

have been remodeled one or more times,

if not completely enclosed in later addi-

tions. Post-constructional work is

usually evident, unless it was done soon after the

original building was completed. It

requires time to evaluate all aspects, and, unless

the structure is disused and already

falling apart, it is often as difficult to find the

owner and obtain permission to

investigate building details as to actually do the

work. A small amount of hand

"demolition" is often necessary to get a glimpse

under the flooring or plaster. It is an

axiom in the "antiques" field that nothing is

valuable until an interest has been

expressed, and permission for an investigation

is often slow in coming--if at all.

A stylistic dating guide to log

buildings in Ohio could probably be established

if a county by county survey were

undertaken. Most of the effort would be literary,

for time is the only major factor in

measuring and drawing the extant structures

(not to mention finding them). The

actual dating of the buildings is dependent on

the county documents available. A date

and style correlation could be compiled

from the data. Whether there is any

value in such a study is academic since most

extant log houses and barns in Ohio can

be dated, de facto, 1815 to 1860 without

the necessity of close examination.

Perhaps more interesting would be a cultural

typology in which certain elements of

construction could be traced to European

precedents. As a case in point: Although

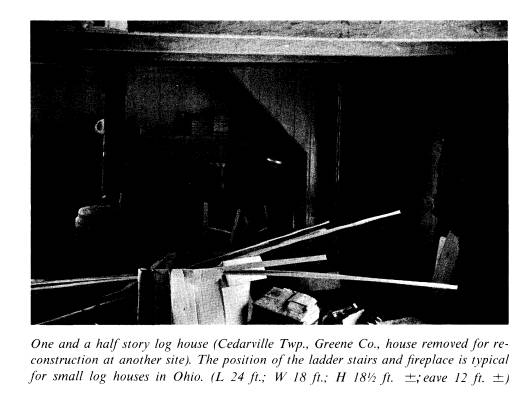

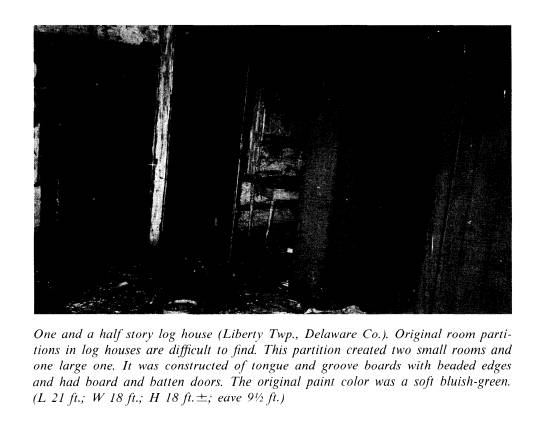

the majority of log houses in Ohio had

ladder stairs in a corner adjacent to

the fireplace, a few houses built.by Germans

in northwestern Ohio at mid-nineteenth

century used stoves, so that the chimney

was pulled away from the wall and the

ladder stairs were behind the chimney.

Was this a modification of an older

interior design found in Ohio, or was it an

innovation from Germany via recent

immigrants? Perhaps the stove was moved

towards the center of the room simply to

improve the heat distribution and had

nothing to do with Ohio or German

typology. Such details are often mundane,

but in future years they could help

solve complex ethnologic if not architectural

problems.

The author made every attempt to survey

log buildings on as wide a scale as

possible in the state, but distance and

time were unavoidable considerations. A

round trip of 250 miles to examine one

building can be tedious no matter how

excellent the structure might be. It was

soon apparent that the counties bordering

the Old National Road (U. S. Route 40)

and south to the Ohio River contained

the majority of extant specimens.

Consequently, the illustrations used in this mono-

graph are drawn largely from this half

of the state. Since many log buildings

exhibit the same or similar

characteristics, it was felt best to choose the photographs

of clearest detail, which meant that

some architecturally divergent examples might

be close geographically. (Weather

conditions and time of day were often critical

in obtaining good photographs.) The fact

that the majority of counties in Ohio are

not represented in this work should not

be taken to mean that log buildings are

rare or nonexistent in these counties.

Most of the photographs are by the

author; the exceptions are indicated. A log

building can be a particularly difficult

subject to photograph due to its monochro-

matic coloring, its lack of reflectance,

and the often harsh contrasts of light and

shade. An exterior view of a log

building surrounded by snow, or an interior view

of the dark chasm of a log barn, is a

photographic horror when a minimum of

176 OHIO

HISTORY

equipment and speed of execution are

desiderata.

Because some of the interior views were

made with an ultra-wide angle lens,

they are distorted in reference to

normal eye perspective. Due to the distortion,

spatial relationships are exaggerated

and the rooms appear larger than they really

are. The flat lighting characteristics

of a camera-mounted flash unit are not desir-

able, as some of the photographs attest,

but carrying and using such a unit was

much easier than making a time exposure

on a tripod. Often extraneous light was

not sufficient or at the correct angle

for a time exposure. Experience proved that

the old-fashioned flashbulb was much

preferable to a stroboscopic flash unit for

recording the dusty, drab interiors of

log buildings. The better reflectance of light

in the red band of the spectrum was no

doubt the reason. A variety of lenses and

several models of Leica cameras were

used for the photographs.

There is a method to date precisely the

year in which a log was cut, which prob-

ably could be used in Ohio. The science

of dendrochronology is based on the study

of growth rings of a single variety of

tree in a specific geographic location. The

rate of growth of a tree depends on many

factors, including the site, the amount

of rainfall, and seasonal temperature

variances. The amount of growth season to

season is shown by the width of the

annual rings. Trees of the same variety and

in essentially the same climatic and

site conditions show similar annular patterns.

If a chart of this growth pattern is

available, an unknown specimen can be com-

pared until its annular pattern agrees

with the appropriate section in the master

chronology. Since a chronology is

normally based on a living tree, the exact date

of the cutting can be established if the

last growth ring (the "bark ring") is present

on the specimen.

A tree ring chronology has been

established in the southwestern United States

for the Pinus aristata which

covers more than seven thousand years. A chronology

based on oak now spans one thousand

years in Germany, and there are hopes of

extending it to five thousand years.

Since two hundred years would be more than

ample to cover the history of log

building in Ohio, it is entirely possible that such

a chronology could be established for

each of the several woods most commonly

found in log buildings. Fortunately,

because most logs in buildings retain their

bark or waney edge, the necessary

qualification for precise dating is present. (Per-

sons interested in dendrochronological

dating should read chapters 7 and 8 in

Scientific Methods in Medieval

Archaeology; see bibliography under

Berger.)

Errors slip into every undertaking. A

better example cannot be cited than on

the heading of page 933 of The

American College Dictionary (New York, 1958),

where "pluviometry" is spelled

"pulviometry." No doubt the present author is

guilty of worse mistakes although every

effort has been made to make the text

accurate. The quotations have been

checked to their original publication whenever

possible. Positive statements and

conclusions were substantiated through literary

or physical evidence. A research topic

such as log architecture in Ohio is open-

ended, for buildings and relative

documents lurk in all corners of the state awaiting

discovery. There has to be a beginning,

however, and it is hoped that this mono-

graph will result in a more

comprehensive volume at a later date.

D. A. H.

DONALD A. HUTSLAR

The Log Architecture

of Ohio

1 The Antecedents of Log Construction

In order to simplify a complex subject,

log architecture has been divided here into

two facets: The historical background of

log buildings and the technical knowledge

necessary for their construction. Though

to a large extent history and technique

are mutually dependent, it does not

necessarily follow that a culture lacking the

knowledge of log building does not have

the tools and technical ability required

for such a construction method. Given

the proper impetus, such a culture could

quickly and easily change its mode of

building from, say, framed houses to log

houses. This, in fact, was the course of

events for most immigrants to the North

American colonies in the seventeenth and

eighteenth centuries--particularly for the

English and Scotch-Irish. Naturally, the

history of log building in Ohio falls at the

culmination of this structural epoch

rather than at its inception.

Though the literature on log building is

not extensive, several historians have

compiled sufficient evidence from

contemporary sources to prove that the practice

of building with logs, at least for

domestic and not military purposes, was brought

to the United States by immigrants of

Scandinavian origin who had a tradition of

log construction in their heavily

forested countries. Swedes and Finns apparently

introduced log construction in the area

known as New Sweden at the upper end

of Delaware Bay, about the middle of the

seventeenth century. From this small

settlement the log house spread up the

Delaware River into country now embraced

by the states of Pennsylvania and New

Jersey. Certain nationalistic traits distin-

guished the Swedish and Finnish

structures, although both cultures used some

variety in their corner notching and

methods of dressing the logs. They commonly

used both saddle-notched round and

full-dovetailed hewed logs for walls, including

log gables. The Scandinavian fireplace

was usually in a corner, with the chimney

often made of sticks and clay.

Throughout Central and Northern Europe, the full-

dovetailed corner notch was common.

Following closely on the heels of the

New Sweden immigrants were those from

the Germanic states who brought their

own cultural traditions of log construction.

This influx late in the seventeenth

century initially centered in the Delaware Valley

of Pennsylvania. The typology of log

building here was as diverse as the cultural

Mr. Hutslar is associate curator of

history at The Ohio Historical Society.

178 OHIO

HISTORY

groups from Germany. If any

characteristics can loosely be termed "Germanic,"

they are a gable end or central chimney

(and the consequent off-center entry door),

and either vertical or horizontal

clapboarding on the framed gables. Corner notch-

ing systems were similar in Scandinavia

and Germany. The shingled roof, however,

was in common use in Germany but rare in

Sweden and Finland. Immigrants from

the latter countries apparently did use

roof shingles out of necessity before the

Germans arrived, but their usual roofing

was long, vertically placed split timber.

By the end of the seventeenth century,

therefore, when the basic precepts of

log building on the European continent

had been transferred to North America,

it would have been possible in most

cases to identify the national origin of the

occupant of a log house by its method of

construction. The next group of immi-

grants was, in large part, responsible

for the diffusion of log building in the Colonies

and the subsequent loss of nationalistic

typology. These people were the Scotch-

Irish--Protestant Lowland Scots who had

largely resided in stone cottages in northern

Ireland for several generations before

emigrating to the Colonies in several waves

beginning early in the eighteenth

century. Although there were settlements of

Scotch-Irish scattered throughout the

Colonies, the majority landed in the Delaware

Bay area. Naturally the immigrants near

the Swedish-Finnish settlements learned

that style of log building, while those

in the Philadelphia area learned the Germanic

style.

Because of the great numbers of

Scotch-Irish, a migration wave began in the

Colonies, particularly to the west and

south into south-central Pennsylvania, Mary-

land, Virginia, the Carolinas, and

Georgia. Thus, by the third quarter of the eight-

eenth century, due to the availability

of plentiful forests and the movement of the

Scotch-Irish, and the Germans, log

building had become the common construc-

tional mode on the boundaries of

colonial settlement. As a consequence, the cultural

typology of log construction became

greatly diluted. The Scotch-Irish, who had no

tradition of log building, had no qualms

about borrowing elements of any style of

construction which they encountered. The

vast majority of log buildings found in

Ohio today are of this eclectic

"style."

Log building had not been confined to

the Delaware Bay area before the Scotch-

Irish arrived. However, most of the few

contemporary references to log buildings

in the New England area prior to 1700

are to buildings for defense, i.e., block-

houses or garrison houses. The Dutch

immigrants to New Netherland certainly

had no tradition of log building and

probably very little knowledge of wood con-

struction of any kind for Holland had no

large forests. The same was practically

true for the English immigrants because

the great forests of England were either

denuded or under the control of the

Crown by the end of the sixteenth century.

The development of England's great naval

power during the century had so de-

pleted the timber resources of the

island that wood became an important item of

trade between the Colonies and the

parent country in the seventeenth century.

Log buildings had been known in early

medieval England, but many generations

had passed and with them the knowledge

of log construction, before migration

began to the Colonies. The image of the

Pilgrims celebrating the first Thanksgiving

Day outside their log cabins is one of

fiction, unfortunately perpetuated through

popular art. In reality, they lived in

dug cellars at first, and when they built houses,

they cut timber to make clapboard

buildings. Perhaps if the Pilgrims had sought

refuge in some state east of Holland,

they might have gained knowledge of log

building for domestic purposes. For an

exhaustive discussion of this topic, two

180 OHIO

HISTORY

books are authoritative: The Log

Cabin Myth by Harold R. Shurtleff (Cambridge,

1939) and The Log Cabin in America by

Clinton A. Weslager (New Brunswick,

1969).

Log building was known in France, though

the horizontal notched log style was

less common than walls composed of

vertical logs set in the ground. This style,

termed "poteaux-en-terre,"

existed in France as late as the nineteenth century and

was used in French settlements in the

New World. The Russians built numerous

log structures in Alaska in the latter

eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries,

some of which still stand. However, the

Russian influence apparently did not extend

beyond the northwest coast of the

present United States.

As to the North American Indians of

pre-Columbian days, there is no evidence

that they ever used notched horizontal

logs though there is circumstantial evidence

that they knew the use of

vertically-placed logs for defense. It would have been an

incredibly difficult task to fell, hew,

and notch timber using only stone tools and

fire. Several sixteenth century

illustrations portray Indian towns fortified with pali-

sades. For example, Jacques le Moyne de

Morgues, a member of the French expe-

dition to Florida in 1564, did several

paintings showing palisaded villages. These

paintings were engraved by Theodore de

Bry and published in Europe in 1591;

engraving number 30, entitled "A

Fortified Village," shows a number of Indian

huts or wigwams surrounded by a vertical

log wall.1 An Englishman, John White,

did several watercolor sketches of

Indians while at the Roanoke Colony in Virginia

in 1585-86. Several of his watercolors

were engraved by De Bry and published in

1590. "The Town of Pomeiock"

(Hyde County, North Carolina) and "The Town

of Secota" (Beaufort County, North

Carolina) are shown with palisades.2

In James Smith's narrative of his

captivity by the Indians (see chapter 3 for

quotation), he describes a winter hut

built in Ohio near Lake Erie in the year

1755.3 The side walls were of logs laid

on top of each other and held in place by

two stakes at each end--a logical

solution to the difficulty of cutting and aligning

notches. The roof was made of bent

branches covered with animal skins. This rudi-

mentary log building could have had

Indian rather than European antecedents,

though it is unlikely it was entirely of

Indian origin because the eastern Indians

had been in contact with the white man

some 140 years by the time of Smith's

description. (John Heckewelder, a

Moravian missionary, describes a similar struc-

ture in his Narrative.4) Since

most Indian tribes were migratory by nature, perma-

nent housing did not have a place in

their cultures until the second half of the

eighteenth century.

The three Moravian missions built during

the 1770's in eastern Ohio--Schoen-

brunn, Gnaddenhuetten, and

Lichtenau--contained many log buildings, some quite

large. Undoubtedly the Delaware Indians

in these missions were influenced by the

methods used in these structures. On the

other hand, it would be difficult to assess

the influence of the English fur

traders' cabins built at Fort Pickawillany (near

Piqua) during the years 1749-52. It is

certain that the Indians contributed nothing

to western man's knowledge of log

building in the seventeenth century, and prob-

ably knew nothing of log structures

prior to this time with the possible exception

of using logs for stockade walls.

1. Stefan Lorant, ed., The New World (New

York, 1946), 95.

2. Ibid., 190-91.

3. James Smith, An Account of the

Remarkable Occurrences in the Life and Travels of Colonel James

Smith ... (Philadelphia, 1834), 37-38.

4. John Heckewelder, Narrative of the

Mission of the United Brethren Among the Delaware and

Mohegan Indians (Philadelphia, 1820), 298.

Log Architecture 181

2 Log Construction in Ohio

General History

Most early log buildings were erected as

temporary structures because they pro-

vided the best solution to the immediate

need for shelter in an area where proc-

essed building material could not be

obtained quickly. Other types of temporary

shelters--tents, wigwams, lean-tos,

caves, dug cellars--also were used throughout

the settlement period, which actually

spanned the seventeenth, eighteenth, and

nineteenth centuries, depending on

locality. The kind of shelter chosen varied with

the need of the resident, who, according

to early observers, fell into one of several

categories of distinctive types of

persons found on the frontier. Early writers who

perceived that a pattern of civilization

had early developed on the frontier included

Francis Baily, in his Journal of a

Tour in Unsettled Parts of North America, in 1796

& 1797 (London, 1856), and William Blane, in An Excursion

Through the United

States and Canada During the Years

1822-23 (London, 1824).

The first arrivals on the frontier, the

backwoodsmen, were sustained by living

from the land and trading with both

Indians and white men. They required only

the rudest shelters, perhaps wigwams or

lean-tos of branches. The squatters, who

were the first families, needed more

stable housing--rough-finished cabins. The

third group, the pioneers, wrested

homesteads from the wilderness but kept moving

as they followed the frontier. Appearing

in Ohio by the late 1780's, the pioneers

left a legacy of cleared land to their

successors, the settlers, who improved the land

and built permanent houses. For the

squatters, the pioneers, and the settlers, the

log cabin quickly and simply filled

their immediate need for a secure home.

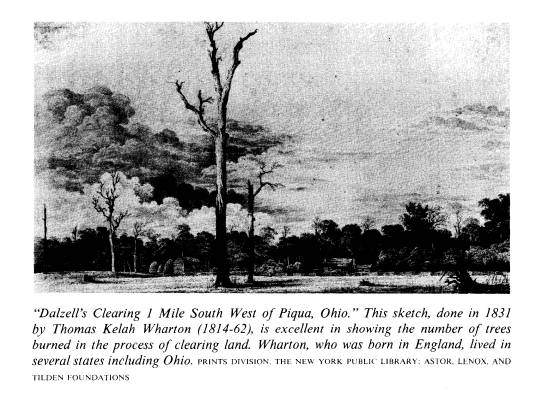

Since for the most part the

trans-Appalachian area, including the Ohio Country,

was heavily timbered, building material

was readily available for constructing a

house, barn, and outbuildings. On the

other hand, the forest was considered the

pioneers' greatest enemy for it

sheltered the Indian and predatory animal and pre-

vented sunlight from reaching

agricultural crops. The removal of as many trees as

possible was a necessity for the pioneer

farmer. Consequently, the oft heard phrase,

"the cabin in the clearing,"

which evoked a certain romanticism even by mid-

nineteenth century, was based on a less

poetic reality.

"Who built the first log structure

in Ohio?" is just one of the many unanswer-

able questions that face historians.

Perhaps it was the French fur traders who were

engaged with the "western"

Indians on the shores of Lake Erie early in the seven-

teenth century. According to The

Jesuit Relations,5 the network of Indian missions

had been extended to the territorial

boundaries of the Erie Nation, the

"Nation

of the Cat," by 1642. Also, the

missionaries had known something of the nation

previously through information provided

by French fur traders. The French began

to trade with the Miami Indians at their

main village, Teewightewee Town (the

same site as Fort Pickawillany, near

Piqua), about the year 1690. If the French

were not the first to build log

structures in Ohio, it was probably the English fur

traders at Fort Pickawillany, who

erected log huts between 1749 and 1752. It is

known through contemporary documents

that they built a vertical log stockade and

5. Jesuit Relations and Allied

Documents ... 1610-1791, Reuben Gold

Thwaites, ed. (Cleveland,

1898), XXI, 191 ff.

182 OHIO

HISTORY

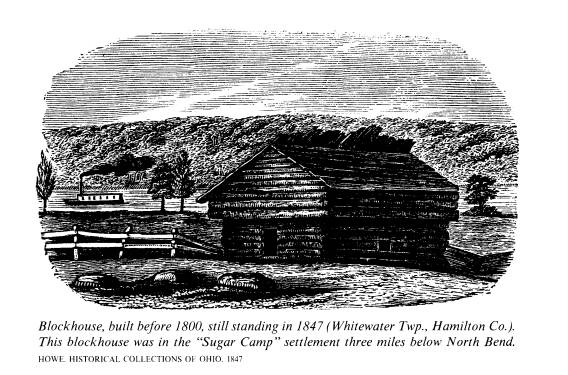

a blockhouse.6 This fur trade post was

attacked by Ottawa Indians, led by one

Langlade and a few fellow French fur

traders, in the spring of 1752. Captain Wil-

liam Trent described in his Journal the

smoke rising from the burning traders'

"houses."7 These

"houses" were probably very similar to structures erected by the

English traders at Fort Michilimackinac

(Michigan)--low cabins of small round logs

set over shallow cellars, in which the

furs and trade goods were stored. Perhaps

the earliest specific comment on a log

building in Ohio is from Smith's narrative

of his capture during the French and

Indian War, referred to earlier. As with the

traders' huts, the Indian wigwam which

he described in 1755 was atypical of the

log structures being erected in the

eastern Colonies.

The period between the French and Indian

War and the advent of the Moravian

missions is somewhat of a "dark

age" in contemporary literature relative to the

Ohio Country. There is no doubt that

squatters did settle within the present boun-

daries of Ohio during this period,

particularly in the major river valleys. An itinerant

preacher and gunsmith by name of Moses

Henry supposedly settled in Chillicaathee,

a Shawanese Indian village (now

Frankfort, Ross County), in 1769. It is possible

he built a log house; at least as an

easterner he should have had the knowledge

to do so. We know the Shawanee were

living in log huts in Chillicaathee by 1772.8

During the Revolutionary War meat

hunters for the Continental Army came

into present northeastern Ohio from

Pennsylvania and many squatters entered the

territory to escape the conflict. It is

unlikely that the hunters built permanent shel-

ters, but the squatters certainly did.

Their settling on Indian land disturbed the

natives so greatly that continental

troops were sent to dislodge the squatters by

burning their cabins and cultivated fields.

The first such expedition took place in

the fall of 1779, when sixty troops of

the Eighth Pennsylvania Regiment under

Captain John Clarke crossed the Ohio

River at Wheeling. Several expeditions fol-

lowed, without great success, prior to

the spring of 1785, when Ensign John Arm-

strong and twenty men toured part of

eastern Ohio expressly to warn off the squatters.

They encountered and were told of

hundreds of families, not only in the eastern

part of the territory but throughout

what is now Ohio. Not only was the popula-

tion greater than six years previously,

but it was so well settled that the squatters

had apparently organized their own

government in the spring of 1785; "governor

William Hogland, west of the Ohio"

is mentioned in the Pittsburgh Gazette, Sep-

tember 29, 1787.9

There are many references, particularly

in military correspondence, to squatters'

"huts," "cabins,"

and "houses." Undoubtedly among the great variety of types of

shelters was the log cabin, made of

either round or hewed logs. It is possible that

some of these structures still exist in

eastern Ohio, though proof would be hard

to find.

The oldest known, datable building in

Ohio (with the possible exception of the

Ohio Land Company office) was erected

shortly after part of present Ohio was

officially opened to settlement by the

Ordinance of 1787. This extant structure is

the Rufus Putnam house in Marietta,

which originally was a section of the fortifi-

cation known as Campus Martius, built by

the Ohio Company beginning in 1788.

6. William Trent, Journal of Captain

William Trent, Alfred T. Goodman, ed. (Cincinnati, 1871),

43-44, 91.

7. Ibid., 85.

8. David Jones, A Journal of Two

Visits Made to Some Nations of Indians (New York, 1865), 56.

9. Randolph C. Downes, "Ohio's

Squatter Governor: William Hogland of Hoglandstown," Ohio

Archaeological and Historical

Quarterly, XLIII (1934), 273.

|

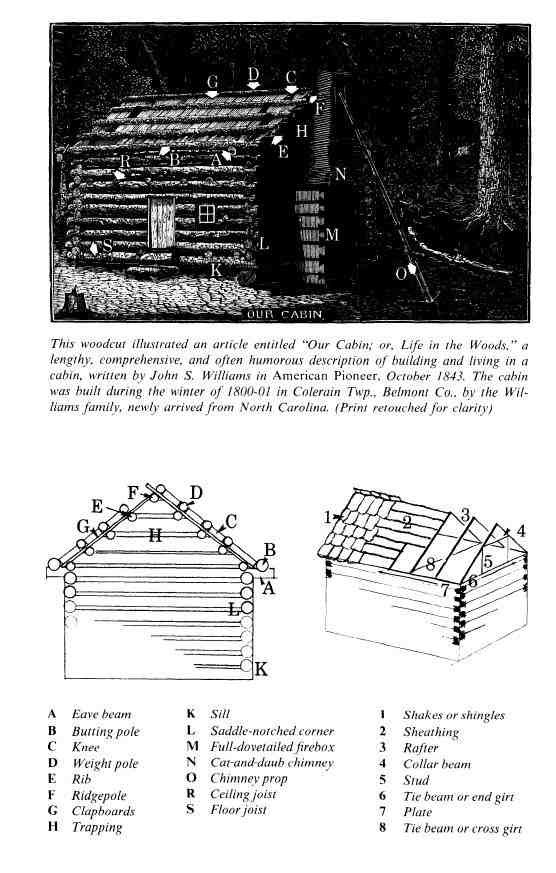

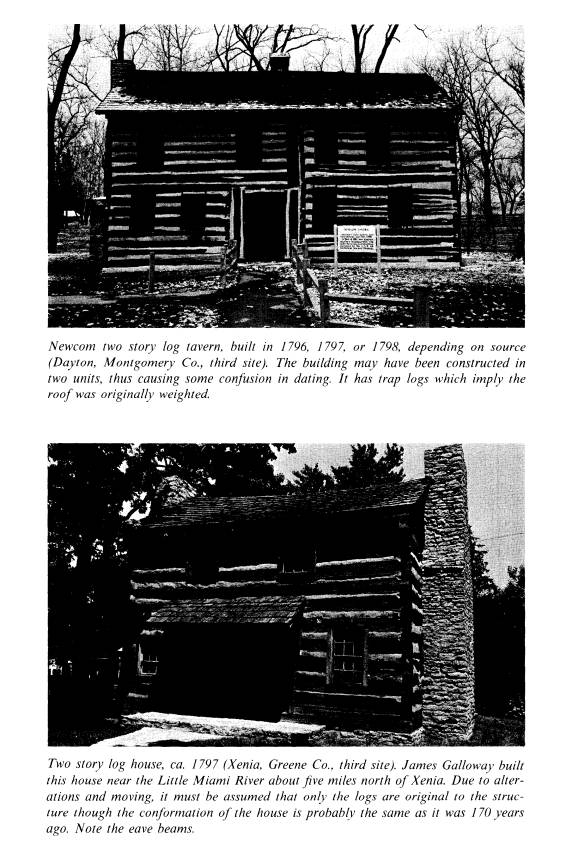

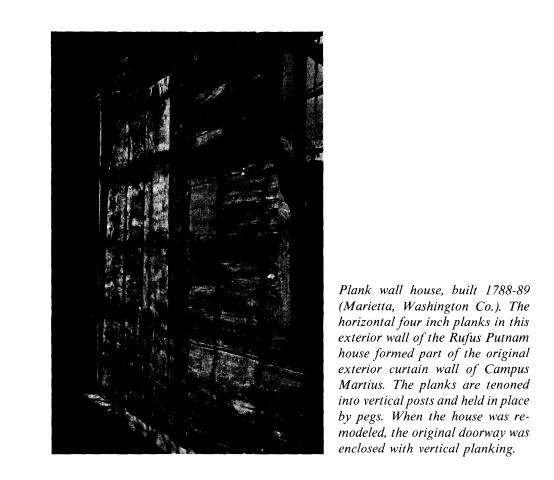

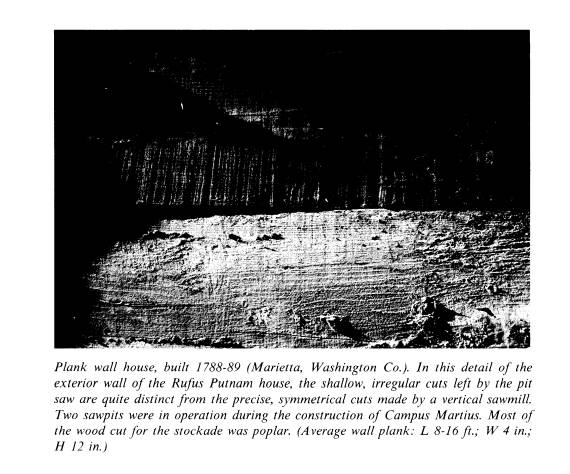

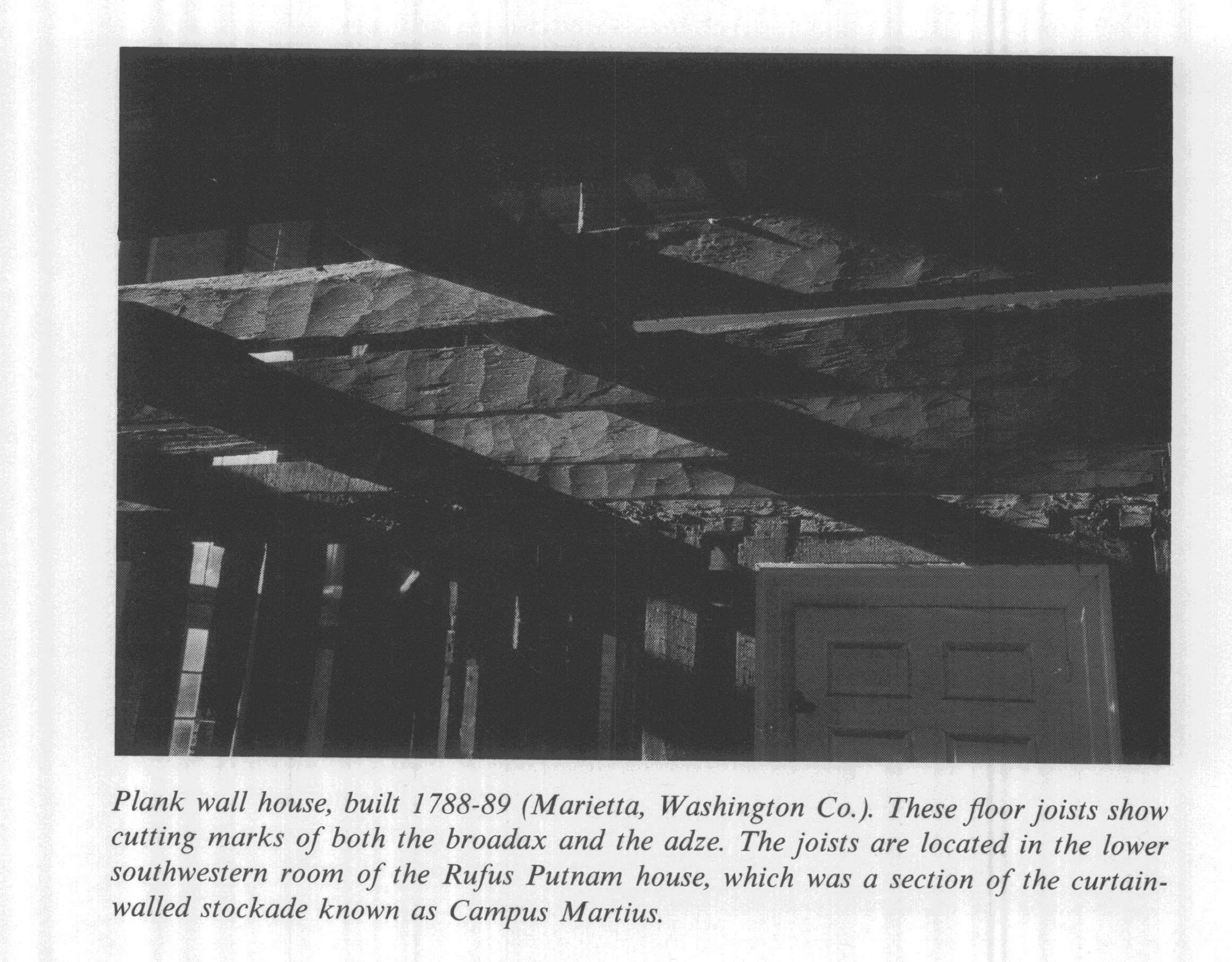

Campus Martius was not a military establishment though it was designed as a fortification and administered in a similar fashion (most Ohio Company members had served in the Revolutionary War). Though commonly referred to as "log," Campus Martius was more specifically "plank wall" in constructional technique: Four inch poplar planks were mortised and pinned into vertical posts placed at varying intervals. Most of the planks were pit-sawed rather than hewed to dimension. Plank construction was used in many late eighteenth century military forts in Ohio and elsewhere, and also in some domestic building--especially in New England, the former home of many members of the Ohio Company. The Putnam house contains the only documented examples of pit-sawed timber in Ohio of which this writer has knowledge. Campus Martius was a 180 foot square, double-walled stockade, where members of the Ohio Company and their families lived in apartments between the plank curtain walls. Rufus Putnam occupied a section approximately 36 feet long and 18 feet wide which was two stories high. He had a cellar and a finished garret by late 1790. When the company sold Campus Martius, section by section, beginning in the winter of 1795-96, Putnam bought the blockhouse adjacent to his section and used that timber to almost double the size of his house. The building is now en- closed in a wing of the Campus Martius Museum in Marietta. Soon after numerous outposts had been established in and around Marietta, another large settlement, Gallipolis, was begun about 110 miles down the Ohio River by the Scioto Company to house about five hundred French immigrants of |

|

urban background. Before their arrival in 1790, more than sixty log houses were erected, under contract between the Scioto Company and Rufus Putnam, who hired Major John Burnham of Essex, Massachusetts, to do the actual construction. Soon after Burnham and about forty men arrived in Marietta, Putnam gave Burnham a letter of instruction, dated June 4, 1790, which offers some interesting details of log construction: The object is to erect four block [houses] and a number of low huts, agreeably to the plan which you will have with you, and clear the lands. Your own knowledge of hut building, the block house of round logs which you will have an opportunity to observe at Belleprie, together with the plan so clearly explained, renders it unnecessary to be very particular; however, you will remember that I don't expect you will lay any floors except for your own convenience, nor put in any sleeper or joyce [sic] for the lower floors; plank for the doors must be split and hewed and the doors hung with wooden hinges; as I don't expect you will obtain any stone for the backs of your chimneys, they must be made of clay first, moulded into tile and dried in manner you will be shown an example at Belleprie.10 Putnam obviously was using the term "blockhouse" in a military sense. His "huts" were very primitive log cabins without wooden floors. Apparently the firebox was wood faced with thin clay tiles, since Putnam surely would not have used the term "tile" for "brick." 10. E. C. Dawes, "Major John Burnham and his Company," Ohio Archaeological and Historical Quarterly, III (1891), 43. |

Log Architecture

185

The French botanist Andre Michaux, who

visited Gallipolis in 1793, later wrote

that "The houses are all built of

squared logs merely notched at the ends instead

of being Mortised."11 This is an interesting statement for it

shows that Michaux

was familiar with a mortised style of

building--probably not unlike that used at

Campus Martius--and, in fact, he may

previously have visited Campus Martius.

Also, this method of corner framing was

in use in French military construction,

with which he was no doubt familiar. It

is surprising that he had not seen more

examples of the notched corner; at least

he implies that such a method was unusual

to him. Assuming that Michaux's

"houses" were the same as Putnam's "huts," it

is puzzling to note that they were

constructed of hewed logs. Putnam's outline of

spartan finishing details indicates the

use of round logs. By 1802, when Michaux's

son visited Gallipolis, most of the

French settlers had moved away, leaving "about

sixty log-houses, most of which being

uninhabited, are falling into ruins."12

Even though the first half of the 1790's

was a period of Indian warfare in Ohio,

some settlers continued to enter the

territory. Many of these people were probably

drawn to the area because of the

conflict, knowing there was always a market for

goods and produce where military

operations were being conducted. Once the

Treaty of Greene Ville was concluded in

1795, the Great Miami River Valley was

settled with amazing speed. Many

soldiers and militia who had been with Clark

and Wayne in the campaigns stayed to

take up residence. Among the buildings

erected in Dayton at this period was Newcom's

Tavern (1796-1797-1798, depend-

ing on source), which may be the oldest

documented log structure in Ohio--assum-

ing that the Putnam house is atypical of

domestic log building. Though now

removed from its original location, the

tavern still stands in Dayton.

Earlier log buildings may exist in the

state, although documentation of such

structures is extremely difficult

because construction techniques changed little from

the eighteenth into the twentieth

centuries. There is a log house at the south edge

of Waynesville, Warren County, that

could predate the 1797 founding of the village,

though the evidence is circumstantial.

However, it is probably the oldest log house

still inhabited in Ohio. Another extant,

early documented log building is a tavern

built by John Treber on Zane's Trace,

Tiffin Township, Adams County, in 1798.

Treber was a gunsmith who, in a way, was

forced into the tavern business because

so many travelers stopped at his house.

The present structure is part log, part stone.

The Ohio Land Company office at Campus

Martius Museum in Marietta is a

plank wall structure that dates between

1788 and 1800, depending on the source.

The company records mention the

construction of an "office" in 1788, but it would

seem logical such an "office"

was not needed until Campus Martius was placed

on sale in 1795. Near Steubenville is a

log building which was a combination home

and federal land office built by David

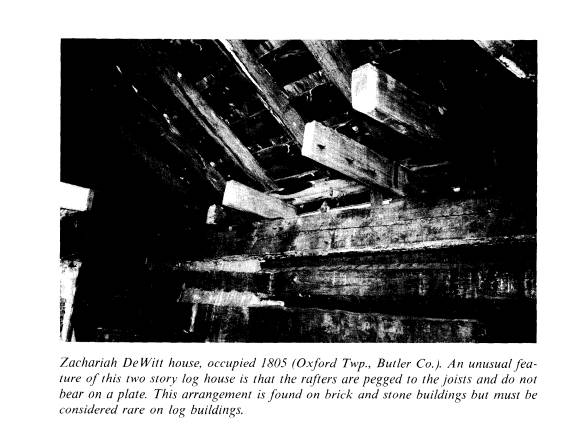

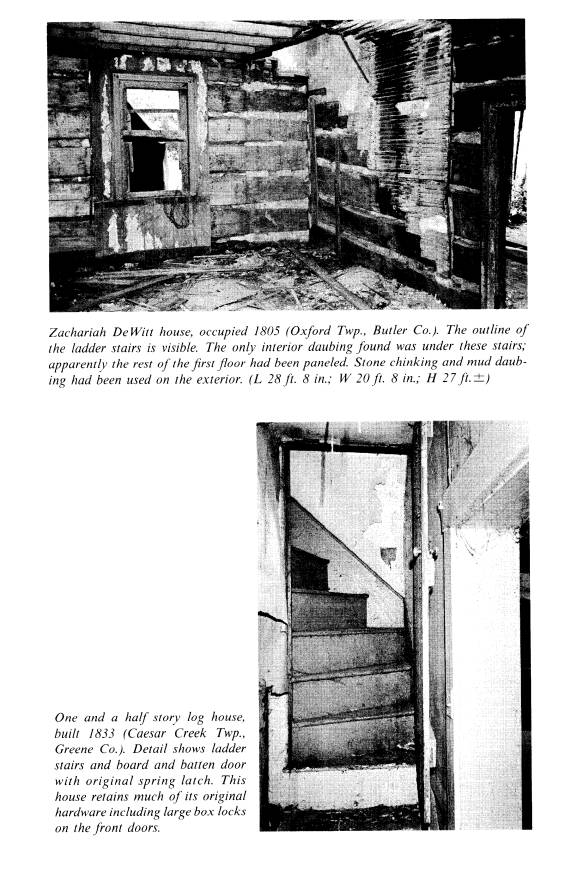

Hoge in 1801. Zachariah DeWitt settled just

east of Oxford, Butler County, in 1805.

His two story log house, probably built

that year, is still standing, an

exceptionally well-finished structure. John Johnston,

federal Indian agent, had a log house

and barn built on his land at Piqua, Miami

County, in 1807-08. The barn, now owned

by The Ohio Historical Society, is the

largest double-pen structure in Ohio

known to this writer. Each pen is approximately

thirty feet square. The hewed plate is

in two sections, one section being 15 inches

11. Andre Michaux, "Travels into

Kentucky, 1793-96," in Reuben Gold Thwaites, ed., Early

Western Travels (Cleveland, 1904), III, 34.

12. Francois Michaux, Travels to the

West of the Alleghany Mountains . . . (London, 1805), 100.

|

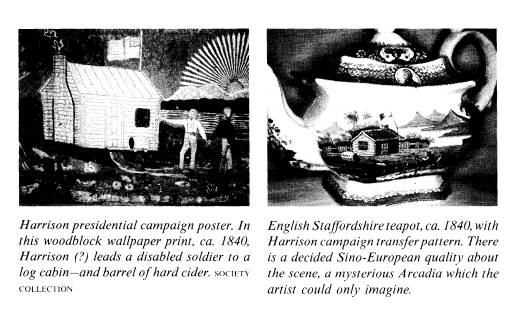

square by over 60 feet in length. The log buildings that have been briefly described are examples that can be documented in Ohio from between the time of formal settlement in 1788 and the War of 1812. No doubt others exist around the state. Except for the federal Indian reservations and state-owned land in northwest Ohio, all of Ohio was open for settlement following the War of 1812. Thousands of log houses, churches, schools, barns, and miscellaneous outbuildings were erected from 1815 until mid-century, though most of these buildings, other than houses and barns, have disappeared. Two log churches should be noted: One still occasionally used is Old St. Peter's Roman Catholic Church, Lawrence Township, Tuscarawas County, completed in 1840. The other, Detterman Evangelical Church, built in 1848, stands as a storage building on a farm in Adams Township, Seneca County. The Mystique and Tradition of "The Cabin in the Clearing" In a comparatively short span of time the log cabin in Ohio ceased to be regarded as a functional necessity and assumed a certain "romantic" aura, in the dictionary sense of "the imaginative or emotional appeal of the heroic, adventurous, remote, mysterious, or idealized," i.e., "having no basis in fact." A more cogent example of this romanticism could not be found than in the Harrison presidential campaign of 1840. General William Henry Harrison of North Bend, Hamilton County, Ohio, was almost sixty-seven years old, when, in 1839 as the Whig party presidential candi- date, he became identified with log cabins, even though he had been born in a James River, Virginia, mansion, and had never lived in a log building as such. On December 11, 1839, the Baltimore Republican, a newspaper opposed to the Whigs, printed a column by John de Ziska, who derisively said of Harrison the westerner: "Give him a barrel of hard cider, and settle a pension of $2000 a year on him, and our word for it, he will sit the remainder of his days in his log cabin by the side of the 'sea-coal fire' and study moral philosophy!"13 De Ziska knew not what he wrought; the "log cabin and hard cider" allusion 13. Clinton A. Weslager, The Log Cabin in America (New Brunswick, 1969), 262. |

Log Architecture

187

became the catchphrase that bound

together the most divergent political factions

in the western states and elected

Harrison to the presidency. In actuality, Harrison's

only connection with a log cabin was

that a one room log house had been incor-

porated at the eastern end of his North

Bend home when it was enlarged. Though

Harrison never claimed to have been born

in a log cabin, he did nothing to dispel

the image created in the campaign.

Not only did the 1840 campaign set a

pattern for several generations of politicians

--for to have been born in a log cabin

became tantamount to success in politics--

it began the mystique of the log cabin.

Real log cabins were placed on running

gear and paraded in many towns. An

amazing number of objects, from handker-

chiefs to Staffordshire tea services,

were decorated with a log cabin and a cider

barrel. The log cabin became a symbol of

"the good life," real or imaginary, to

tens of thousands of persons in the

United States of 1840. To aging pioneers it

represented their youth, hope, ambition.

To the young, it was a symbol of the

accomplishments of their parents and

grandparents, often made in the face of great

odds, and was a spur to their own

achievements.

It is appropriate to note that, at least

for the eastern half of the country, by 1840

the rigors of frontier life had been

overcome enough to allow such a romanticized

view of pioneering and log cabin life to

develop. The War of 1812 had denoted

the beginning of the end of the

"frontier" period in Ohio. After 1815 the rise of

urban centers, growth of industry, and

development of agriculture progressed at an

amazing speed. The traditional basis of

pioneering--agriculture--first felt the effects

of mechanization in the late 1830's and

ten years later, agricultural periodicals were

implying that a farmer was backward if

he was not making use of the various

machines available to him. Ceding of the

last Indian reservation in Ohio in 1842

really marked the end of the state's

frontier. No wonder, then, that the older gen-

eration felt a certain longing for the

less complex days of the "log cabin in the

clearing."

That the end of the frontier period in

Ohio did indeed arrive about 1840 is no

better evidenced than in the following

excerpt from the Western Courier and Piqua

Enquirer:

HUSKING PARTY . . . . We like to recur

occasionally to the customs and pastimes of our

ancestors. . . . We know that these may,

at first view, appear rude and forbidding--that the

sensibilities of the fashionables of the

present generation would be shocked at the bare

idea of a Quilting Frolic--an

Appleparing, or a Husking Party. . . .

This sounds much like current rhetoric,

but it was published November 18, 1837.

Though the original article may have

been reprinted from another newspaper, the

fact that the description could be

applied to western Ohio in 1837 reinforces the

conclusion that the end of an epoch had

been reached.

Although log building continued

throughout the century in Ohio, the reasons

for its continuance were relative to

each specific site. By mid-nineteenth century

the log house had become confined to the

rapidly disappearing unsettled areas and

to the less economically successful

sections of the state. By then sawed timber could

be obtained throughout Ohio and the

frame house had become the standard, rea-

sonably priced housing. Before

settlement had become general throughout the

state, the easiest method of

constructing a log building had been to erect it in the

midst of a forest, so that the logs did

not have to be moved far to the building

site. However, once the overall forest

covering Ohio had been broken into small

|

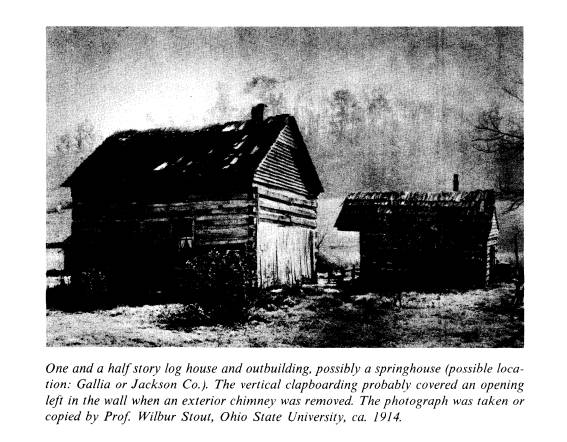

units by settlement, it was easier to saw the timber into usable sizes and transport it to the site. The greatest number of log houses built after 1850 were in the southeastern quar- ter of the state, where iron furnaces, charcoal and later coke, were well established by mid-century. Probably the greater portion of the housing supplied to or built by the furnace workers was of log. Many were photographed early in the twentieth century by Professor Wilbur Stout of Ohio State University. There are log houses still standing, and some still occupied, in the countryside surrounding the iron furnace region. Many were probably built by workers who wanted to oper- ate a small farm in addition to holding their jobs. The charcoal iron furnaces de- clined shortly after the Civil War primarily because of lack of wood for charcoal. A few of the furnaces which converted to coke managed to operate until recently. Perhaps the last vestiges of the primitive log cabin were the hunters' and trap- pers' cabins built during the latter nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Since professional hunters and trappers usually stayed on their grounds for several months during the winter season, their accommodations, while meagre, had to protect them from severe weather. E. N. Woodcock, a professional trapper, described a "hut" he and his partner built in Cameron County, Pennsylvania, in 1869: We rolled up the usual box log body, about 10 x 14 feet. We put up a bridge roof, putting up about four pairs of rafters and then using three or four small cross poles for roof boards. We then peeled hemlock bark, making the pieces about four feet long, which we used for shingles to cover the roof with. After the roof was completed, we felled a chestnut tree which we split into spaults [spalls] about four feet long. With these we chinked all the cracks between the logs, striking the axe into the logs, close to the edge of the chinking |

|

and then driving a small wedge in the slot made by the axe to hold the chinking in place. Next we gathered moss from old fallen trees and stuffed all the cracks, using a blunt wedge to press the moss good and tight. . . . We found a bank of clay that was rather free of stones and made a mortar by using water .... The chinking and mossing had been done from the inside, while we now filled the space between the logs good and full of mortar, or rather mud.... After the [stone] fireplace was completed, we hung a door, using hinges made of blocks of wood and boring auger holes through one end. Shaping the other end on two of these eyes to drive in two holes boring into the logs close to the door jams. The other two eyes were flattened off and made long enough for door cleats as well as to form a part of the door hinge. Now a rod was run through these eyes or holes in these pieces. This formed a good solid door hinge.14 This writer has heard that at least as late as 1937, a log house was built in the traditional style in southeastern Ohio. Log barns and farm outbuildings were built into the twentieth century because the log corncrib and tobacco shed were ideally suited to provide the drying conditions needed for those crops. A few statistics are available which give an indication of the number of log houses extant in Ohio in the twentieth century. In March 1939, the United States Department of Agriculture published the results of a farm-housing survey con- ducted in the winter of 1934.15 In the nine Ohio counties surveyed, there were 794 log houses being used as residences (4.3 percent of 18,464 houses surveyed). These counties were: Adams, Ashland, Ashtabula, Darke, Madison, Monroe, Muskingum, 14. E. N. Woodcock, Fifty Years a Hunter and Trapper (Columbus, 1913), 141-42. 15. U. S. Department of Agriculture, The Farm-Housing Survey. Miscellaneous Publication No. 323 (Washington, D.C., 1939). |

190 OHIO HISTORY

Paulding, and Sandusky. No log houses

were located in Ashtabula County, and

less than one percent of the houses were

log in each of the counties of Ashland,

Paulding, and Sandusky. In Monroe

County, 15.8 percent of 2,029 houses were

log; and in Adams County, 11.3 percent

of 2,269 houses were log.

It is tempting to take the average of

houses per county, roughly 88, times the

number of counties in Ohio, 88, to obtain

a vague idea of the number of log houses

in use in the state--7,744. This is

probably as good a generalization as any obtain-

able. What the total would be in 1972 is

even more vague, though obviously it

would be lower--and probably much lower

even if all log structures were counted.

However, a survey of Athens County in

progress in late 1971 turned up a sur-

prising total of 97 log buildings. As a

comparison, an 1810 census of Cincinnati

listed 232 frame houses, 55 log houses,

37 brick houses, and 14 stone houses; of the

total, approximately 13 percent were

log.16 This proportion was probably true for

most urban areas in early nineteenth

century Ohio. Of course, the presence of

sawmills and craftsmen in such areas

affected the type of housing erected.

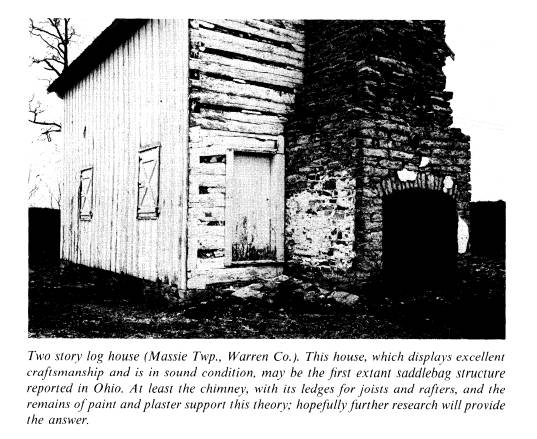

In 1972 the remaining log structures are

primarily in the southern half of the

state. The southeastern quarter probably

has more buildings than the southwestern

quarter, but older buildings are more

frequent in the latter area. Some very fine

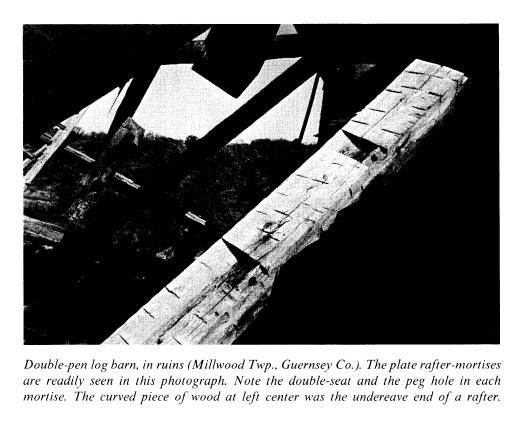

log barns are to be found in the

east-central region, in and around Guernsey

County. The principal routes of

migration into and through Ohio should indicate

where to look for early buildings--and

such, indeed, seems to be the case, for the

most consistent distribution of

buildings lies along the old routes, such as Zane's

Trace and the National Road, and in the

various river valleys which terminate at

the Ohio. Possibly many of the main

Indian trails, such as the Grand Council

Trail through central Ohio, would show a

similar pattern of settlement if the routes

could be accurately determined.

Dating Buildings

Dating log buildings is a most difficult

task, for if no private records exist, the

only public records that might give a

clue are the tax duplicates and they seldom

yield much information. One of the old

standard methods of dating a structure,

particularly of log, is to give the

building the same date as the original land grant

or purchase. This method gives

problematical results at best. (A scientific method

of dating is discussed in the author's

comments.)

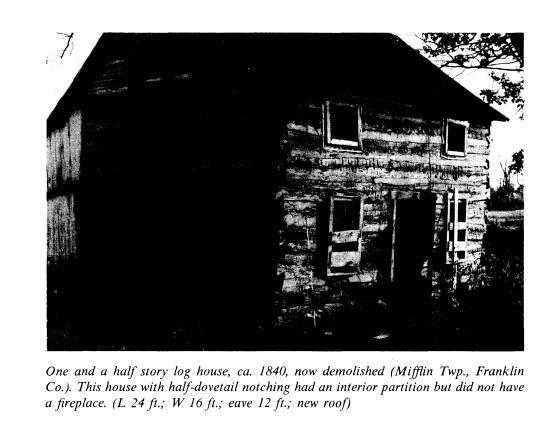

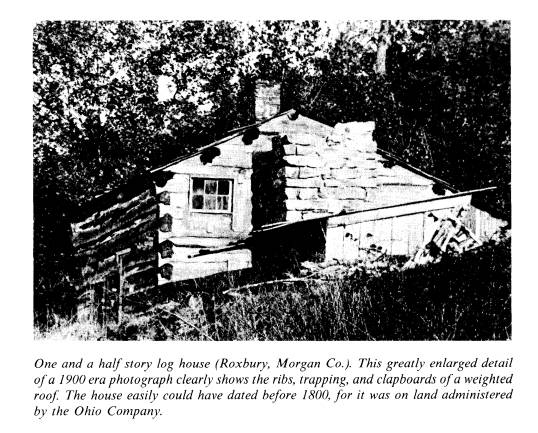

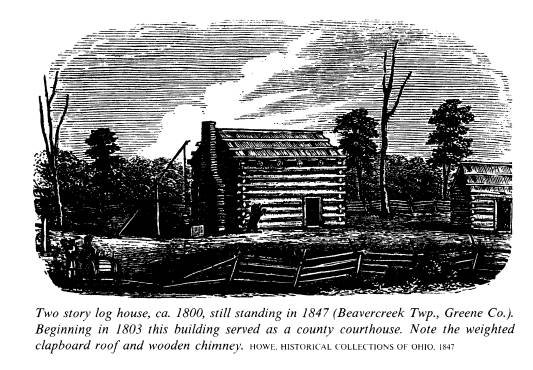

Most of the log structures seen today

date from between the War of 1812 and

the Civil War. A few changes which seem

to have taken place in log building in

Ohio during this time span are helpful

in giving approximate dates to an undocu-

mented structure. Even though a great

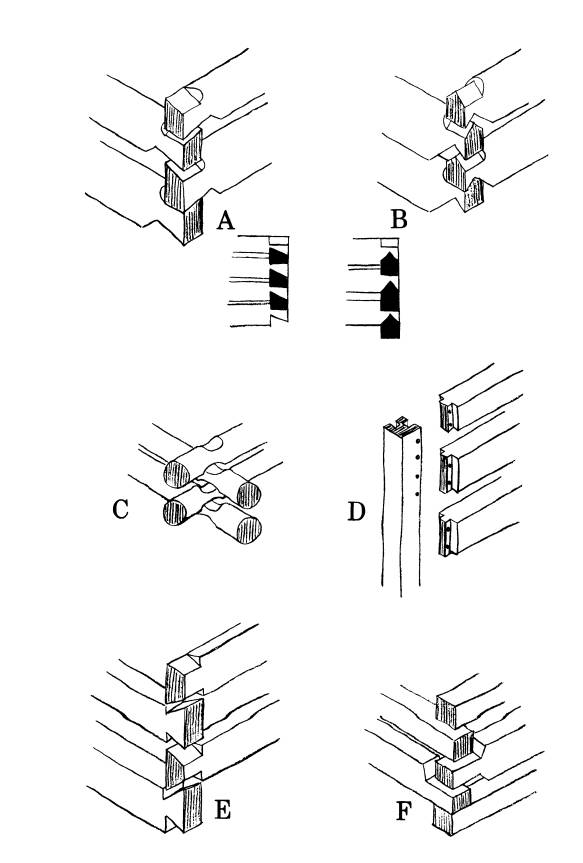

variety of corner notching systems were

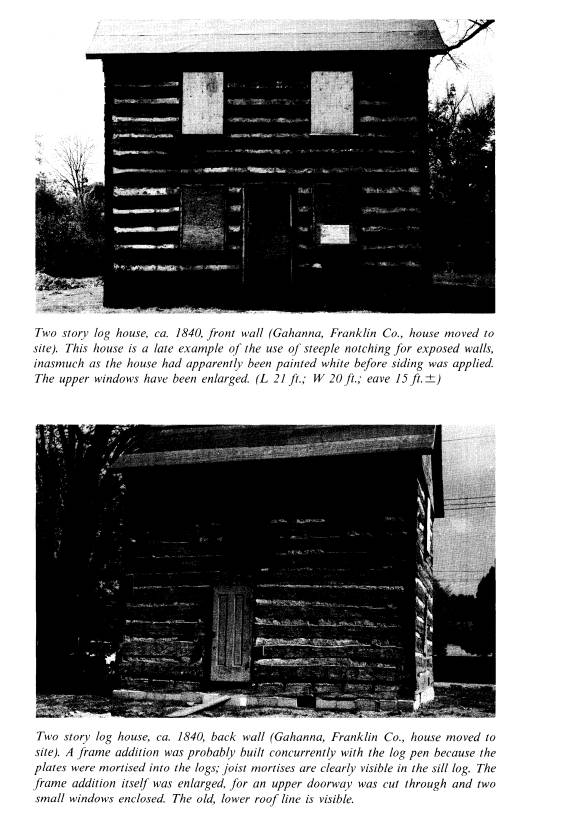

known, the two common styles in Ohio

were the "steeple" or "inverted V" notch

and the "half-dovetail" or

"freezeproof" notch. Until approximately 1825 (and it

must be understood that there is no

method of establishing a precise date), the

steeple notch was used almost

exclusively on all buildings regardless of function.

In structures from the second quarter of

the century, the steeple notch is rarely

found on a house--unless it was intended

that the house should have siding. Use

of the steeple notch did remain

predominant for barns and outbuildings through-

out the rest of the century. Beginning

about 1825 or slightly later, the half-dovetail

16. Liberty Hall (Cincinnati), November 13, 1810.

|

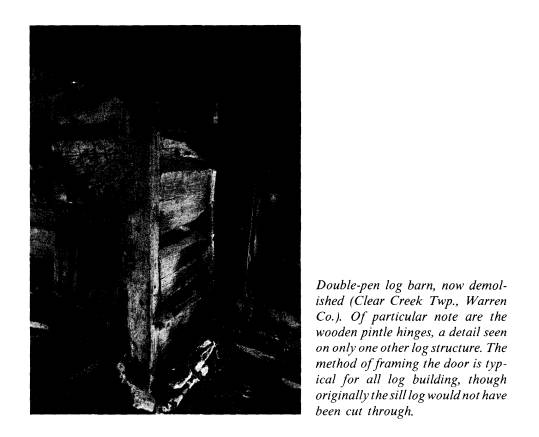

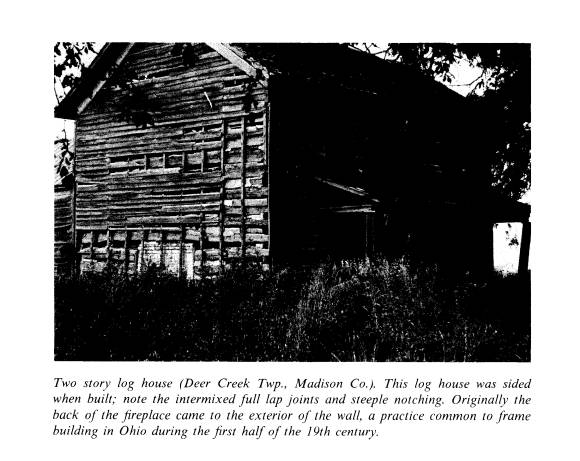

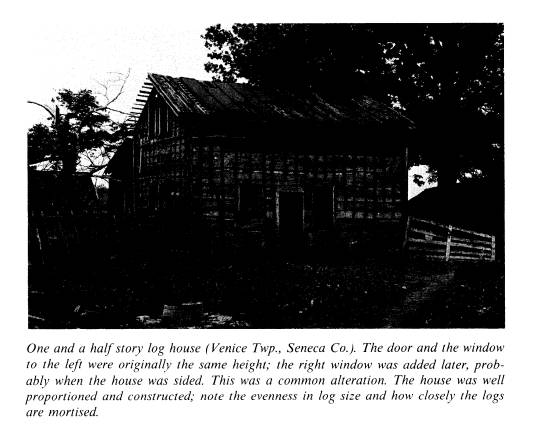

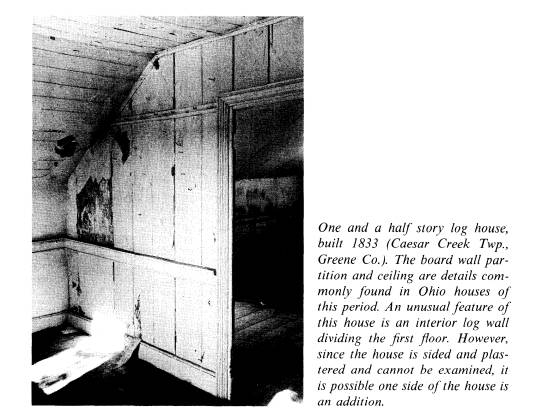

became the common notch for houses and remained so into the twentieth century. If the logs in a house are found to be lapped or half-lapped over one another, there is little doubt that the house was sided at the time it was built. A mixture of corner notching styles also indicates siding was present. Just because a house was built of logs does not mean that the builder or owner preferred logs for aes- thetic reasons and wanted to expose them to view. The logs formed the structural support of the building, just as wood studding, bricks, and concrete blocks do today. Few buildings are built with concrete block exposed on both inner and outer walls for purely aesthetic purposes. The log walls of 1800 and the concrete block walls of 1972 are identical in function, though different in visual and tactile qualities. Another good indication of building age, for at least the first third of the nine- teenth century, is the pitch of the roof. The most common pitch was 9 inches rise to 12 inches run, or approximately 37 degrees angle. The popularity of the various "revival" schools of architecture in Ohio ended the seemingly consistent use of the 12-9 roof. A more subtle age indicator lies in the proportions of the building's exterior. This may seem a moot point in relation to log building, since the builder was dependent to a certain degree on the size of trees available, but some guide to proportion seems to have been used. The usual lengths of measurement found on log structures are, in feet: 12, 15, 18, 24, 30, and 36. A three foot rule (or ax han- dle) could have been the basis for such measurements, though the common carpen- ter's rule in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries was normally one foot long. On a one story structure including a loft space (what would be called a story and a half today), the height to the eave line was commonly 8 to 10 feet, and the |

|

height of the ridge was almost always equal to the width of the house. Thus, a house 18 feet long by 15 feet wide would have a ridge height of 15 feet. Of course a two story log house did not follow this height ratio, but had two full floors plus a loft. Today such a house has a tall, narrow appearance. Actually all log, frame, brick, and stone houses of the early nineteenth century tended to follow the above proportions. Once the eye has become accustomed to recognizing the relationships between the length, width, height, and roof pitch of these early buildings, they are very easy to spot even while driving. One easily recognizable clue to an early house location is the presence of one or more large red cedar trees (Juniperus virginiana). Since the red cedar was a pop- ular early nineteenth century ornamental, these trees often reveal the site of a des- troyed and forgotten structure. |

194 OHIO

HISTORY

3 Contemporary Descriptions of Log Buildings in Ohio

Indian Housing of the Eighteenth

Century

There are several descriptions of Indian

housing in Ohio in the eighteenth cen-

tury, though references to log buildings

are rare. One of the earliest and best reports

is given by Colonel James Smith in his

small book, An Account of the Remarkable

Occurrences in the Life and Travels

of Colonel James Smith, During his Captivity

with the Indians in the Years 1755,

'56, '57, '58 & '59. The log

"cabin" which he

described was built west of Cleveland

near the mouth of Black River in the winter

of 1755-56. Smith lived in this

structure while he was held captive by a mixed group

of Indians, primarily Caughnewagas but

including Delawares and Wyandots.

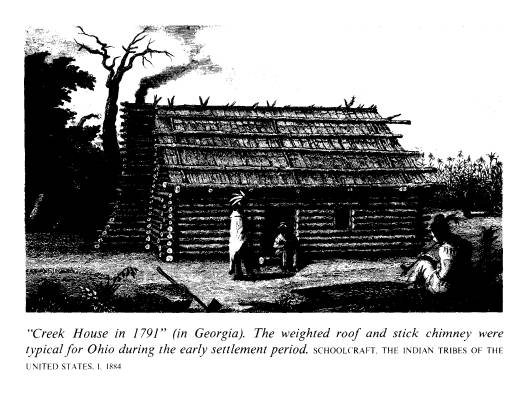

They made their winter cabin in the

following form: they cut logs about fifteen feet long,

and laid these logs upon each other, and

drove posts in the ground at each end to keep

them together; the posts they tied

together at the top with bark, and by this means raised

a wall fifteen feet long, and about four

feet high, and in the same manner they raised

another wall opposite to this, at about

twelve feet distance; then they drove forks in the

ground in the centre of each end, and

laid a strong pole from end to end on these forks;

and from these walls to the poles, they

set up poles instead of rafters, and on these they

tied small poles in place of laths; and

a cover was made of lynn bark, which will run even

in the winter season.

* * * * * * *

At the end of these walls they set up

split timber, so that they had timber all round, except-

ing a door at each end. At the top, in

place of a chimney, they left an open place, and for

bedding they laid down the aforesaid

kind of bark, on which they spread bear skins. From

end to end of this hut along the middle

there were fires, which the squaws made of dry

split wood, and the holes or open places

that appeared, the squaws stopped with moss,

which they collected from old logs; and

at the door they hung a bear skin, and notwith-

standing the winters are hard here, our

lodging was much better than what I expected.17

A very similar structure was erected by

the Delawares at Captives' Town (Antrim

Township, Wyandot County, Ohio) in

December 1781. David Zeisberger, the famous

Moravian missionary, described it as

"a structure of poles laid horizontally between

upright stakes, the crevices being

filled with moss."18 This structure, intended as a

church, was built "in less than a

fortnight." Since the details of the winter cabin

and the church are essentially the same,

it is possible that the cabin was the product

of the few Delawares among the

Caughnewagas. By conjecture, this style of log

building was probably a version of the

white man's log house constructed in a fash-

ion commensurate with the tools the

migratory Indians wished to carry. Smith

refers to the Indians using their

"tomahawks" to cut the logs and peel the bark.

These tomahawks were probably what are

referred to today as "squaw axes," smaller

versions of the poll-less European ax.

The upright stakes used to support the walls

could easily have been driven with a

large stone. Actually, there is nothing about

these structures that would require the

use of iron tools, but it is debatable whether

such cabins were known by Indians before

the onset of western civilization.

David Zeisberger wrote a history of the

North American Indians while he was

living at the Moravian missions in

present Tuscarawas County, Ohio, in 1779-80.

He commented on Indian housing:

17. Smith, loc. cit.

18. Edmund de Schweinitz, The Life

and Times of David Zeisberger (Philadelphia, 1870), 529.

|

Houses of the Indians were formerly only huts and for the most part remain such humble structures, particularly in regions far removed from the habitation of whites. These huts are built either of bast (tree-bark peeled off in the summer) or the walls are made of boards covered with bast. They are low structures. Fire is made in the middle of the hut under an opening whence the smoke escapes. Among the Mingoes and the Six Nations [western Iroquois and New York State Iroquois] one rarely sees houses other than such huts built entirely of bast, which, however, are frequently very long, having at least from two to four fire-places; . . . Among the Delawares each family prefers to have its own house, hence they are small. The Mingoes make a rounded, arched roof, the Delawares on the contrary, a high pitched, peaked roof. The latter, coming much in contact with the whites, as they do not live more than a hundred miles from Pittsburg, have learned to build block houses or have hired whites to build them. Christian Indians generally build proper and comfortable houses and the savages who seek to follow their example in work and household arrange- ment learn much from them.19 What Zeisberger meant by "the walls are made of boards" is hard to fathom, though they may have been split saplings. The Shawanese houses at Little Chilli- cothe (now Oldtown, Greene County) in 1779 were also made of "board."20 The term "blockhouse" was in use in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries to differentiate between a hewed log and a round log structure; the hewed log house was termed a "blockhouse." Of course, blockhouse was also a military term having a different connotation. Since a squared log house generally had smaller gaps between the logs, it was safer to defend than a round log cabin. Thus the term "blockhouse" was applied to a very strong military fortification, a soundly con- structed house for personal defense, or a house built of hewed logs rather than round logs. The semantics of "blockhouse" has caused a great deal of confusion 19. David Zeisberger, "David Zeisberger's History of the Northern American Indians," Ohio Archaeological and Historical Quarterly, XIX (1910), 17-18. 20. "Bowman's Expedition Against Chillicothe, May-June, 1779," Ohio Archaeological and Histor- ical Quarterly, XIX (1910), 454. |

196 OHIO

HISTORY

among historians, amateur and

professional, and has led to much misinterpretation.

Unfortunately, it is often impossible

when reading old documents to decide which

meaning was intended.

If any Indian nation was in a position

to use and spread log building, it was

the Delaware. They were descendants of

the Lenape Nation, western Indians who

had moved to the Susquehanna and

Delaware rivers and the Delaware Bay area

well before the white man arrived in

North America. The Delawares on the Schuyl-

kill River moved to the Susquehanna in

1709 because of pressure from the Five

Nations to join in warfare, first

against the French, then against the English. (Thomas

Dungan, former governor of New York, had

sold the lands of the Susquehanna

River Valley to William Penn in January

1696.) By 1728 the Delawares were com-

plaining about a colony of Palatine

Mennonites settling on Indian land in Mont-

gomery County, Pennsylvania. These early

movements of the Delawares can be

traced in H. F. Eshleman's book, Lancaster

County Indians (Lancaster, 1909), which

is a compilation of various colonial

documents. The Delawares subsequently moved

slowly to the west, many in close

alliance with the Moravian missions in Pennsyl-

vania and then in Ohio in the 1770's and

1780's. Some of the Ohio Delawares

went on to Canada, where their

descendants are still living. Throughout these moves,

the Delawares were in the precise

geographic locations to learn log building tech-

niques from the Swedes and Finns in the

seventeenth century and from the Germans

in the eighteenth century. Most of the

nation, but not all tribes, were known to be

"peacemakers," who seemingly

stayed near the European settlements. Consequently,

their nomadic habits and Indian customs

were subjected to enormous pressures of

change.

The comments by Smith on Indian log

building in Ohio could refer to the Del-

awares; certainly the group at Captives'

Town were Delawares. At Easton, Pennsyl-

vania, in July of 1757, Delaware Chief

Teedyuscung made the following request

of the governor of Pennsylvania:

And as we intend to make a Settlement at

Wyomen, and to build different Houses from

what we have done heretofore, such as

may last not only for a little Time, but for our

Children after us; we desire you will

assist us in making our Settlements, and send us

Persons to instruct us in building

Houses....21

The village of Wyomen was near present

Wilkes-Barre. The request was granted;

ten cabins, 10 by 14 feet, and one

cabin, 16 by 24 feet, were built. These "cabins"

were constructed of hewed, dovetailed

logs. In September 1768, according to Zeis-

berger, the village of "Garochati

on the Pemidhannek" [river] in western Pennsyl-

vania had "houses built in various

styles...." The account continues:

Some are weather boarded block-houses

and have chimneys. Some are two story houses,

having a staircase on the outside. These

houses have a tower-like appearance, because they

are not more than fourteen feet in

length and in breadth. All the work on them was done

by Indians and, considering that they

have very crude tools, the structures are very credit-

able to the builders.22

The previous year, September 1767,

Zeisberger had visited Friedenshuetten,

Pennsylvania:

21. [Charles Thomson], An Enquiry

into the Causes of the Alienation of the Delaware and Shawanese

Indians from the British Interest (London, 1759), 115-16.

22. Archer Butler Hulbert and William N.

Schwarze, eds., "The Moravian Records, Volume Two,

The Diaries of Zeisberger Relating to

the First Missions in the Ohio Basin," Ohio Archaeological and

Historical Quarterly, XXI (1912), 82.

|

From the 26th to the 29th I found much pleasure in visiting the Indians in their dwellings. Many were engaged in building log houses. They build very neat houses of hewn timber, with chimneys and glass windows, and fit them up very tastefully.23 Friedenshuetten was indeed an elaborate Indian mission. John Heckewelder also visited the village in 1767; in his Narrative he comments: Their meeting-house was much too small to contain their number--wherefore they built a large and spacious church, of squared white pine timber, shingle roofed, with a neat cupola and bell on the top.... They did all their work in the best manner possible, both in build- ing and fencing, so that at this time there were forty well built houses of squared timber, and shingle roofed, in the village; and the gardens back of them were all in good clap- board fence.24 The three Moravian missions in Ohio--Schoenbrunn, Gnaddenhuetten, and Lich- tenau--located along the Tuscarawas River in Tuscarawas County, were begun some five years later than Friedenshuetten. (The Ohio Historical Society at present main- tains a reconstructed village on the site of Schoenbrunn.) The layout of these vil- lages, which were devoted primarily to the Delawares, was very similar to that of the missions in Pennsylvania. The Ohio missions, established just before the Revo- lutionary War, lasted only a short time because the Christian Delawares were sub- jected to much harassment by Indian allies of the British. Nicholas Cresswell, the redoubtable English diarist, visited Schoenbrunn, arriving at the village on Sunday afternoon, August 27, 1775. He wrote: It is a pretty town consisting of about sixty houses, and is built of logs and covered with Clapboards. It is regularly laid out in three spacious streets which meet in the centre, where there is a large meeting house built of logs sixty foot square covered with Shingles, Glass 23. Ibid., 9. 24. Heckewelder, op. cit., 97. |

198 OHIO

HISTORY

in the windows and a Bell, a good plank

floor with two rows of forms. Adorned with some

few pieces of Scripture painting, but

very indifferently executed. All about the meeting

house is kept very clean.25

Both Zeisberger and John Ettwein

described the house of Chief Netawatwes at

Gekelemukpechunk (present Newcomerstown,

Tuscarawas County), the capital of

the Delawares. Zeisberger states that,

in 1770, Gekelemukpechunk "was a large and

flourishing town of about one hundred

houses, mostly built of logs."26 He was the

guest of Netawatwes, whose house had a

shingle roof, board floors, a staircase, and

a stone chimney. When Ettwein was at the

village in 1772, Netawatwes still had his

"well built house of nicely squared

logs, with a shingle roof."27

By the third quarter of the eighteenth

century, Indians other than the Delawares

were building log structures in Ohio.

The Shawanese village of Little Chillicothe

(present Oldtown, Greene County) was

attacked by a company of militia under

Colonel John Bowman in May 1779. A white

prisoner of the Shawanee described

the village at the time of the attack:

Northeast of the center of the town

stood the council house-a large building, said to have

been sixty feet square, built of round

hickory logs, one story high, with gable ends open

and upright posts supporting the

roof.... There were several board houses or huts in the

south part of the village--some ten or

twelve.

?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ??

[During the attack] the men reached the

board shanties on the south; and at once began

the work of plundering, giving the

savages ample time to fortify themselves by fastening

securely the door of the huge building

they had congregated in.28

Since Bowman did not risk an attack on

the council house, one must assume that

it was well constructed and easily

defended. The remains of this building supposedly

were still visible in 1840.

In 1772, the Reverend David Jones

described the Indian village of Chillicaathee,

which stood on the present site of

Frankfort, Ross County. In this Shawanese vil-

lage the houses were made of logs, but

apparently in a haphazard fashion: "Nor

is there any more regularity observed in

this particular than in their morals, for

any man erects his house as fancy

directs."29 In the Reverend Oliver M. Spencer's

narrative, Indian Captivity, there

is a description of the English fur traders' village

known as "The Glaize," which

stood at the junction of the Auglaize and Maumee

rivers at the present site of the city

of Defiance, Defiance County. In 1792 this post

consisted of "five or six cabins

and log houses." The residence of one George Iron-

side was "a large hewed log house,

divided below into three apartments."30 These

"apartments" were used,

respectively, as a warehouse, store, and dwelling. There

was also a small stockade enclosing two

log houses--one a storehouse and the

other a residence.

Spencer provides an excellent

description of an Indian bark cabin belonging to

an Iroquois "priestess,"

Cooh-coo-cheeh, living with the Shawanee in northern Ohio:

Covering an area of fourteen by

twenty-eight feet, its frame was constructed of small poles,

25. Nicholas Cresswell, The Journal

of Nicholas Cresswell, 1774-1777 (New York, 1924), 106.

26. De Schweinitz, op. cit., 366.

27. Kenneth G. Hamilton, John Ettwein

and the Moravian Church . . . (Bethlehem, Pa., 1940),

261-62.

28. "Bowman's Expedition . . .

," op. cit., 454-55.

29. Jones, loc. cit.

30. Oliver M. Spencer, Indian

Captivity (New York, 1834), 90-91.

Log Architecture 199

of which some, planted upright in the

ground, served as posts and studs, supporting the

ridge poles and eve [sic] bearers,

while others, firmly tied to these by thongs of hickory

bark, formed girders, braces, laths, and

rafters. This frame was covered with large pieces of

elm bark, seven or eight feet long, and

three or four feet wide; which being pressed flat,

and well dried to prevent their curling,

fastened to the poles by thongs of bark, formed

the weather boarding, and roof of the

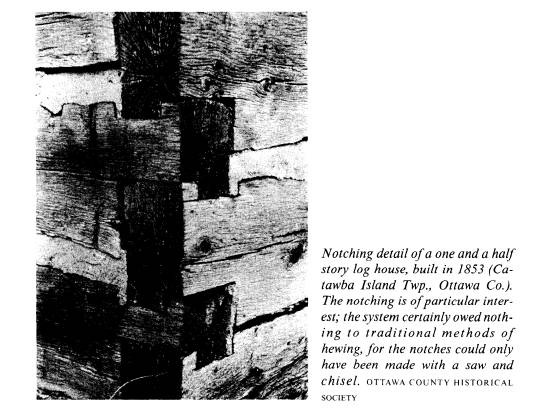

cabin. At its western end was a narrow doorway,