Ohio History Journal

JANET R. DALY BEDNAREK

False Beacon: Regional Planning and the

Location of Dayton's Municipal Airport

Introduction

At first glance, one might logically

conclude that the location of Dayton's

municipal airport represented a case of

deliberate regional planning.

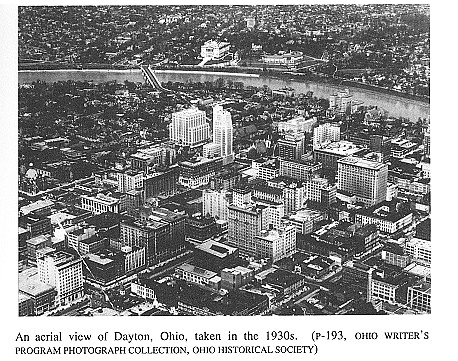

Approximately eleven miles north of the

city's central business district, its

placement near the city of Vandalia,

Ohio, suggests that those who chose that

location had an image or vision of the

city of Dayton which extended beyond

the city's limits. Closer examination,

however, reveals that neither a vision

of a Greater Dayton nor regional

planning had much to do with the location

of Dayton's airport. Rather, it had more

to do with, first, who owned the

property, and second, the technology of

aviation in 1928.

The people involved in building Dayton's

municipal airport included some

of the most powerful and influential

businessmen in the city. Several of

these men, including Edward Deeds, had

close ties to the infant airline indus-

try.1 Those men had the necessary local

clout to push through their plans for

a municipal airport, even in the face of

competition from other plans. When

the initial private venture failed,

those same business leaders mounted a drive

to purchase the airport from its

creditors and simply presented it to the city.

Further, they understood the new airline

industry, especially its technological

limitations.

Efforts to establish a municipal airport

began in earnest in 1926. One

might wonder why the home of the Wright

brothers took so long to establish

its own airport. Part of the reason lay

in the fact that up to 1926, the avia-

tion industry was an extremely risky

business. It remained risky after 1926,

but by that time the national government

had taken two actions which less-

ened the risk somewhat and offered

considerable incentives. On May 20,

1926, Congress passed the Air Commerce

Act. That act, pushed by Secretary

of Commerce Herbert Hoover, gave the

Department of Commerce powers to

Janet R. Daly Bednarek is Assistant

Professor of History at the University of Dayton.

1. Deeds' son, Charles, was a major

stockholder in and treasurer of Pratt & Whitney, an

aviation engine manufacturer. In 1928,

Pratt & Whitney became part of the United Aircraft &

Transportation Company which also

controlled United Airlines. See Henry Ladd Smith,

Airways: The History of Commercial

Aviation in the United States (Washington,

D.C., 1991),

124, 233-35.

126 OHIO HISTORY

both regulate and encourage commercial

aviation in the United States.

Combined with the first Airmail Act

(Kelly Law) passed in 1925, which dic-

tated that the Post Office's airmail

routes be turned over to private carriers,

government actions in the mid-1920s

provided a significant boost to commer-

cial aviation.2 By 1928, when

the group of Dayton businessmen had estab-

lished their airport (which would become

the city's municipal airport), com-

mercial aviation was on a growth track

that would continue even during the

Depression decade of the 1930s. The

promise of profit dictated when the air-

port would be established. And, although

the location of Dayton's airport

might suggest an effort at regional

planning, personalities and the limitations

of technology played the major roles in

determining where the city's munici-

pal airport would locate.

Background: Locating Dayton's

Municipal Airport

If an airport is defined as a place

designed for airplanes to take off and land,

then the Dayton area can probably lay

claim to being the home of the world's

first sustained airport. While some

might claim that the dunes near Kitty

Hawk, North Carolina, where Orville and

Wilbur Wright made their first four

successful flights, served as the first

airport, the brothers abandoned that loca-

tion shortly after December 17, 1903.

The following year, they established a

new airport, complete with hangar, for

the sustained testing of their new in-

vention. During 1904 and 1905, the

Wrights conducted test flights in an

open field east of the city, next to the

tracks of the Dayton and Springfield

Interurban, known as the Huffman

Prairie. There they developed the world's

first practical airplane, the Wright

Flyer III. From 1909 until 1915, the

Wright Airplane Company operated a

flying school on the Huffman Prairie.

Orville Wright then sold the company.

The flying school remained for an-

other year, but in 1917 local business

leaders purchased the Huffman land, and

adjoining acres, and leased it to the

government. The original airport, thus,

became part of Wilbur Wright Field, a

World War I training base.3

Once the Huffman Prairie became part of

a military base, civic leaders in

Dayton had a great deal of success in

attracting military air activity to the

area. In addition to Wilbur Wright

Field, located several miles from the city,

Dayton also provided a home for McCook

Field. Headquarters of the Air

Service's experimental station, McCook

Field stood on land along the Great

Miami River near to where that river and

the Mad River converge, about a

mile from the center of town. When threatened

with the closing of McCook

2. Smith, Airways, 94-102; John

D. Hicks, Republican Ascendancy, 1921-1933 (New York,

1960), 176-77.

3. See Lois Walker and Shelby E.

Wickham, From Huffman Prairie to the Moon: The

History of Wright-Patterson Air Force

Base (Washington, D.C., 1988), 1-2,

11-14, 25-30.

Dayton's Municipal Airport 127

Field in the early 1920s, civic leaders

banded together to buy additional land

near Wilbur Wright Field, which they

presented to the government for one

dollar in 1924. Originally known as

Wright Field, then later divided into

Wright Field and Patterson Field, that

land is now the location of Wright-

Patterson Air Force Base and it

continues as a center of aerospace activity.

However, in the mid- to late-1920s, many

people saw the profits from air

activity coming not from the military,

but from the civilian side of the econ-

omy. The money to be made in aviation

came from the carrying of the mail.

The post office experimented with

airmail as early as 1911. Regular airmail

service, initially flown by Air Service

pilots, began in 1918. By the early

1920s, however, private aircraft

operators started agitating for the post office

to turn the airmail service over to

private carriers. In 1925, Congress passed

the Airmail Act (or Kelly Act) which was

designed to "'encourage commercial

aviation and to authorize the postmaster

general to contract for the mail ser-

vice."' In turning the mail service

over to the fledgling commercial airlines,

Congress hoped to help build a strong

commercial aviation industry in the

United States. With the income from the

airmail, companies could build

routes and, it was hoped, eventually

develop a system of air routes across the

country. The airmail subsidy, as it came

to be called, created the opportunity

for airlines to operate at a profit.5

An airline which wished to survive needed

an airmail contract; a city which wished

to have airline service needed to have

an airport at which the airmail planes

could land.

Beginning in 1926, several parties made

bids to become Dayton's official

municipal airport and, thereby, gain

airmail and other commercial traffic. The

Rinehart-Whelan Company, operators of

the Moraine Flying Field (see South

Field, below), went to the city with

their plan in April 1926. Rinehart-

Whelan offered the use of their airport,

five miles south of Dayton along the

Springboro Pike, as the municipal

airport without cost to the city. The city

accepted the following month, and for

the next year or so the Moraine Flying

Field served as Dayton's official

municipal airport. The first commercial ser-

vice to the city of Dayton arrived

approximately one year later when the

Embry-Riddle Company of Cincinnati,

Ohio, inaugurated regular service be-

tween Louisville, Kentucky, and

Cleveland, Ohio, with stops in Cincinnati,

Dayton, Columbus, and Akron, Ohio.6

4. Ibid., 89-90, 108-14.

5. See Smith, Airways, 50-117.

6. Letter, Clerk of the Commission to

Mr. F. O. Eichelberger (City Manager), April 16, 1926

in Dayton Airport Records, MS-59,

Archives and Special Collections, Paul Lawrence Dunbar

Library, Wright State University, Box 1,

File 1, hereafter Airport Records; Letter, City

Attorney to Mr. Eichelberger, May 11,

1926, Airport Records, Box 1, File 1; Letter, Wayne G.

Lee, Managing Director, Dayton Chamber

of Commerce, to City Manager and City

Commission, May 16, 1927, City Manager

Files, Archives and Special Collections, Paul

Lawrence Dunbar Library, Wright State

University, File 8-K 1927, hereafter City Manager

Files.

128 OHIO HISTORY

By the summer of 1927, however, plans

were underway to build a new mu-

nicipal airport. At first civic leaders

turned their attentions to McCook Field.

Its history was tied to the careers of

two of the most powerful civic leaders in

Dayton's history, Edward Deeds and

Charles Kettering. Deeds and Kettering

began their Dayton careers at the

National Cash Register Company (NCR).

In 1909, the two worked together on the

invention of an electric ignition sys-

tem

for automobiles. They then

incorporated the Dayton Engineering

Laboratories Company, or Delco, to

manufacture their invention. The fol-

lowing year, Kettering followed with his

automotive self-starter. They sold

Delco to United Motors (a forerunner to

General Motors) in 1916. The trans-

action made them millionaires and tied

much of their fortunes, and that of

Dayton, to General Motors.7

The story of how and why the Air Service

established McCook Field in

Dayton is a rather complex and tangled

one. In August 1917, Edward Deeds

accepted a commission as a colonel in

the Signal Corps Reserve and became

Chief, Equipment Division. When the

Signal Corps asked him where they

should locate an experimental station,

Deeds first recommended that they

build it on an airfield located on his

private estate south of Dayton. At the

time, the Dayton Wright Aircraft Company

(of which Deeds had been a

founder, but in which he had apparently

sold his ownership stake) was using

South Field (or the Moraine Flying

Field, operated by Rinehart-Whelan by

1926) as a test field. As an

alternative, Deeds suggested the Signal Corps use

North Field, located near downtown

Dayton, which Deeds and Kettering had

purchased in 1917. The Signal Corps

accepted the proposal. Deeds then sold

his half interest to Kettering, who then

sold the entire property to another

company he and Deeds founded, the Dayton

Metal Products Company. The

company leased the land to the Signal

Corps. The United States Government

abandoned the site in July 1927 upon

completion of the new facilities at

Wright Field.8

By the time the government abandoned

McCook Field, ownership of most

of the land, by some means or another,

had transferred to General Motors (of

which both Deeds and Kettering were

major stockholders and officers). Even

though GM placed a price of $600,000 on

the land, it apparently had no inter-

est in selling. A local newspaper

article speculated that General Motors

might be interested in building

airplanes on the site.9 Regardless, the price

7. Article, "Dayton Boasts of Sixth

Air Station," undated, Airport Clipping File, Dayton Main

Library; Stuart W. Leslie, Boss

Kettering (New York, 1983), 38-58.

8. Walker and Wickham, Huffman

Prairie to the Moon, 27, 88-90; Isaac F. Marcosson,

Colonel Deeds, Industrial Builder (New York, 1947), 218, 275-76; Diana Good Cornelisse,

Remarkable Journey: The Wright Field Heritage in Photographs (Air Force Systems

Command: History Office, Aeronautical

Systems Division, 1991), xxiii; Leslie, Boss Kettering,

71.

9. Article, "Dayton Lays Plans for

New Airport," undated, Airport Clipping File, Dayton

|

Dayton's Municipal Airport 129 |

|

|

|

tag was too high and many civic leaders interested in airport development ap- parently felt that the site was too small.10 In any event, by late 1927 the McCook Field site had been abandoned as a site for the proposed airport. In a letter to Mr. George Sudheimer, Commissioner, Department of Public Utilities, St. Paul, Minnesota, Dayton city manager Fred Eichelberger indi- cated that in 1926 the city had purchased 500 acres of land, approximately three miles from the center of town, for use as a sewage disposal site. Apparently, after abandoning the idea of using the McCook Field site, civic leaders developed tentative plans to use part of the sewage disposal site as the location of a municipally owned airport. Information on this plan is scarce. Aside from the reference in the City Manger files, a newspaper clippings col- lection at Dayton's main library contains an undated article outlining a pro-

Main Library; Article, "Dayton Boasts of Sixth Air Station," undated, Airport Clipping File, Dayton Main Library. 10. Letter, City Manager (Eichelberger) to Mr. George C. Sudheimer, Commissioner, Dept. of Public Utilities, St. Paul, Minn., August 25, 1927, Airport Records, Box 1, File 2. |

130 OHIO

HISTORY

posal to build a new airport on land

three miles south of the city. According

to that article, city manager

Eichelberger first suggested using part of the

property, originally purchased for

sewage disposal, as a landing field.

Following his suggestion, local civic

leaders including Charles H. Paul, a lo-

cal consulting engineer, and Frederick

H. Rike, president of Rike's

Department Store, studied the idea.11

In both the August letter to Mr.

Sudheimer and a September 1927 letter to

a reporter for the Memphis

Press-Scimitar, Eichelberger wrote that the plans

for the landing field on the sewage

disposal site were "immature." However,

he felt that the proposed municipal

landing field could be "occupied as such

within eighteen months."12 Once

again, though, plans changed. In late 1927

the city petitioned the government to

use Wright Field for airmail planes and,

in the meantime, civic leaders turned

their attention to a location approxi-

mately eleven miles north of the city,

near Vandalia, Ohio.

In November 1927, City Manager

Eichelberger received a letter from Air

Corps Brigadier General W. E. Gilmore

acknowledging that the city had made

application "to temporarily use

Wright Field for airmail planes to land on."

Gilmore endorsed the idea. In a

subsequent letter, he wrote Eichelberger that

the War Department needed assurance that

Dayton would use the facilities at

Wright Field only on a temporary basis.

Eichelberger replied that the city an-

ticipated using the field for

approximately three years. At that

time,

December 1927, apparently the idea of

using the sewage disposal site had, for

one reason or another, fallen on

disfavor. He wrote General Gilmore that he

expected to ask voters to approve money

for the purchase of a landing field

site in November 1928 and estimated that

within two years of that date the

city would have the airport up and

running.13 On that assurance, Secretary of

War Dwight F. Davis granted a revocable

license for the use of a portion of

Wright Field to the city in March 1928.

Dayton then issued Continental Air

Lines a license to use the field

"in the carrying of the United States mails."14

11. Ibid.; Article, "Dayton Lays

Plans for New Airport, undated, Airport Clipping File,

Dayton Main Library.

12. Letter, City Manager (Eichelberger)

to Mr. George Sudheimer, Commissioner, Dept. of

Public Utilities, St. Paul, Minn.,

Airport Records, Box 1, File 2; Letter, City Manager

(Eichelberger) to Mr. D. L. Hogan,

Reporter, The Memphis Press-Scimitar, Editorial

Department, Memphis, Tenn., September 2,

1927, Airport Records, Box 1, File 2.

13. Letter, Brig. General W. E. Gilmore,

Air Corps to Mr. F. O. Eichelberger, City Manager,

Dayton, Ohio, November 10, 1927, Airport

Records, Box 1, File 2; Letter, Brig. General W. E.

Gilmore, Air Corps to Mr. F. O.

Eichelberger, City Manager, Dayton, Ohio, December 3, 1927,

Airport Records Box 1, File 2; Letter,

City Manger (Eichelberger) to Brigadier General W. E.

Gilmore Air Corps, Wright Field, Dayton,

Ohio, December 9, 1927, Airport Records, Box 1,

File 2.

14. Letter Brig. General W. E. Gilmore,

Air Corps, to Mr. F. O. Eichelberger, City Manger,

Dayton, Ohio, March 21, 1928, Airport

Records, Box 1, File 4; Letter City Manger

(Eichelberger) to Mr. R. P. Cunningham,

Pres., Continental Air Lines, Inc., March 22, 1928,

Airport Records, Box 1, File 4.

Dayton's Municipal Airport

131

It seems, however, that a number of

Dayton's business leaders were not

willing to wait three years for the city

to establish its own airport.

Consequently, within days of finalizing

the city's agreement with Wright

Field, a group of local (and not so

local) businessmen announced that they

had purchased land near the small town

of Vandalia. There they planned to

build a Dayton municipal airport. A

newspaper article at the time listed

many of the businessmen involved. They

included E. G. Beichler, president

of Frigidaire (a subsidiary of General

Motors), Frederick B. Patterson, presi-

dent of National Cash Register, Charles

F. Kettering, vice president of

General Motors and president of the

General Motors Research Corporation

(and by 1928 a resident primarily of

Detroit),15 Frank Hill Smith, construc-

tion engineer (Dayton and New York

City),16 and George Mead, paper manu-

facturer. Later records indicated that

Edward Deeds and Frederick Rike were

also involved.17

Those businessmen incorporated the

Dayton Airport Company in March

1928 and, by selling shares, raised

$300,000 to buy the property and establish

the airport.18 By August 1928 the group had transformed some of the land

into a working airport. In that month a

Captain B. D. Collyer from the

Fairchild Aircraft Manufacture Company

was scheduled to arrive at the new

airport. Charles H. Paul, General Manger

of the Dayton Airport, Inc., wrote

Eichelberger asking him to serve on a

committee planning a reception for the

captain. The group was anxious to

impress him because rumor had it that the

Fairchild Company was interested in

establishing a new propeller factory, and

Dayton Airport, Inc., hoped they would

locate it on their property.19

Even though the owners of the airport

near Vandalia called it the Dayton

Airport, apparently Dayton city

officials felt no special relationship to it. In

January 1929, Eichelberger wrote Mr.

Henry A. Jencks of International

Airports Corp., the following:

15. Kettering moved to Detroit in 1925

when the research division transferred there from

Dayton. He did move back and forth

between the two cities, but in the late 1920s he was

spending a great deal of his time in

Detroit. Leslie, Boss Kettering, 182-83.

16. This information comes from the

letterhead of a message sent from Frank Hill Smith to

the Dayton City Commission in 1933.

Airport Records, Box 1, File 5.

17. Article, "Dayton Airport Work

to Start in A Few Weeks," March 28, 1928, Airport

Clipping File, Dayton Main Library;

Article, Dayton Daily News, Wednesday, October 8, 1952,

James M. Cox Papers, MS-2, Box 6, File

9, hereafter the Cox Papers.

18. Ibid.

19. Letter, George W. Lane, Howard

Keyes, and Charles Paul, Dayton Airport Inc., to Mr.

Fred O. Eichelberger, City Manger,

Dayton, Ohio, August 20, 1928, Airport Records, Box 1,

File 3; Letter, Charles H. Paul, Dayton

Industrial Association, to Mr. F. 0. Eichelberger, August

21, 1928, Airport Records, Box 1, File

3. Dayton Airport, Inc., and the Dayton Industrial

Association shared a common address (922

Dayton Savings Building) and had overlapping

membership. Common to both were

Frederick B. Patterson, president of both, Frederick H.

Rike, vice president of both, John F.

Ahlers, secretary of both, and Charles H. Paul, general

manager of both.

132 OHIO

HISTORY

At the present time, there is nothing

definite relative to a Municipal Airport for

this City. We are fortunate in being

located in close proximity to Wright Field

and facilities have been afforded by the

government to us for the handling of air-

mail from that field. In addition there

are several other Airports already in exis-

tence here. None of which, however, are

municipally owned, so that the immedi-

ate need of a Municipal Airport is not

apparent. There had been some talk, how-

ever, of the City owning its own

Airport. Should this materialize to something

definite, you will be notified...20

From this letter it seems that the city

felt a closer relationship to Wright

Field than to the new "municipal

airport" near Vandalia, and it still had plans

to build its own airport.

The situation changed somewhat, however,

the following month. In

February 1929, the city received a

proposal from the Johnson Flying Service,

a local company, "for the use of

its airport near Dayton for receiving the

Dayton airmail."21 Dayton Airport, Inc., had leased the

airport to Johnson in

1928.22 The city accepted the offer and informed

General Gilmore that "all

the arrangements have been completed for

the transfer of the airmail from

Wright Field to the Vandalia field,

effective next Monday, February 25th."

The city did not agree to the transfer

because Johnson offered a good deal. In

fact, the terms were identical to those

that the city had with the government

for the use of Wright Field. In his

letter to General Gilmore, Eichelberger

stated that the city "consented to

this change for the reason that the new air-

port needs all the help we can give

it" and moving the mail service to the new

field would not adversely effect

operations at Wright Field.23 Though

that ac-

tion could have helped the fledgling

airport, it was far from an endorsement of

it as Dayton's municipal airport. Note

that the Eichelberger letter referred to

it as "the Vandalia field."

Regardless, Dayton's business community

held a dedication ceremony for

the new airport, called Dayton Airport,

on July 31 and August 1, 1929.24

Despite holding the airmail facilities

contract, within a few years the airport

was in trouble, the Johnson Flying

Service was looking to the city for some

help, and the airport had some new

competition.

In June 1932 E. A. Johnson, president of

the Johnson Flying Service,

wrote the city looking for relief. He

asserted that the mail service required

20. Letter, City Manager (Eichelberger)

to Mr. Henry A. Jencks, Vice-President,

International Airports Corps., January

11, 1929, Airport Records, Box 1, File 4.

21. Letter, City Manger (Eichelberger)

to Mr. Harshman (City Attorney), February 11, 1929,

Airport Records, Box 1, File 4.

22. Article, Dayton Daily News, Wednesday,

April 29, 1936, Cox Papers, Box 6, File 9.

23. Letter, City Manger (Eichelberger)

to Mr. Harshman (City Attorney), February 11, 1929,

Airport Records, Box 1, File 4; Letter

City Manager (Eichelberger) to Brigadier General W. E.

Gilmore, Air Corps, Wright Field,

February 21, 1929, Airport Records, Box 1, File 4.

24. List, Committees on Dedication of

Dayton Airport, July 31st and August 1st, 1929,

Airport Records, Box 1, File 4.

Dayton's Municipal Airport 133

that the airport maintain "a beacon

light all night, and boundary, obstruction,

flood, and other lights during landing

periods." These were required in order

for the city of Dayton to have airmail

service. Johnson also said that the

Dayton Airport was the "only one

among the larger cities where Airmail

Planes stop that is not municipally

owned and operated." Since the airmail

was "distinctly a Municipal project"

the city should reimburse his company

for those expenses, approximately sixty

dollars per month, "a small portion

of our entire operating expense."25 Johnson Flying Service paid Dayton

Airport, Inc., $9000 per year for the

rights to operate the airport. When

Johnson gave up his lease the following

year, he said he had lost $50,000 be-

tween 1928 and 1933.26

Appended to the bottom of Johnson's

letter was a brief note from Frank

Hill Smith, president, Dayton Airport,

Inc. In the note, Smith, indicating

that he had taken control of the airport

corporation, suggested another part of

the airport's problems. Smith held a

$45,000 mortgage on the airport prop-

erty, mostly in buildings. In addition,

Dayton Airport Inc., and Smith, also

owed money to the Winters National Bank

and Trust of Dayton. Even

though the Dayton Chamber of Commerce

called a special meeting of its

Aviation Committee to discuss the

financial problems of, significantly, "The

Vandalia Airport," and Eichelberger

wrote Johnson that the City Commission

would consider his request, the airport

apparently received no relief in 1932.27

In February 1933 Frank Hill Smith once

again appealed to the City

Commission. In his letter he suggested

another reason behind the airport's

financial problems (besides the

mortgages and the Depression). When the

city used Wright Field for delivery of

its airmail, it paid the government a

monthly fee. When the airmail service

transferred to the new airport, most

people involved, including the city

manager (who, as noted, wanted to help

the new enterprise), assumed that the

city would pay the same fee to the oper-

ators of the new airport. However,

legal problems apparently kept the city

from paying the fee. Even once new

legislation cleared the legal hurdle, the

city made no definite arrangements to

pay a fee.28

Hill then repeated the argument Johnson

had used the year before. He stated

that as a privately owned field, the

airport could not compete with munici-

pally owned airports. Further, he

asserted: "The entire Airport business is

25. Letter, E. A Johnson, Johnson Flying

Service, Inc., to F. 0. Eichelberger, Manager, City

of Dayton, June 7, 1932, Airport

Records, Box 1, File 5.

26. Article, Dayton Daily News, Wednesday,

April 29, 1936, Cox Papers, Box 6, File 9.

27. Letter, Wayne G. Ley, Managing

Director, Dayton Chamber of Commerce, to Mr.

Howard Smith, Chairman, et al, June 7,

1932, Airport Records, Box 1, File 5; Letter, City

Manager (Eichelberger), to Mr. E. A.

Johnson, Pres., Johnson Flying Service, Inc., June 8,

1932 (Airport Records, Box 1, File 5);

Article, Dayton Daily News, Wednesday, October 8,

1952, Cox Papers, Box 6, File 9.

28. Letter, Frank Hill Smith, President,

Dayton Airport, Inc., to Commission of the City of

Dayton, Ohio, February 21, 1933, Airport

Records, Box 1, File 5.

134 OHIO HISTORY

more of a public service, where no

direct charges can be made, than a com-

mercial business . . . . He

concluded that

.. .the City of Dayton has a moral

obligation to the community as a whole, to

furnish sufficient financial relief to keep the Airport

active during the present

times so that when business in general

does pick up again, the Dayton Municipal

Airport will be ready to serve the

public as any other public service department,

since there is no other field here

suitable.

By 1933, Smith believed that the best

answer was for the city to lease the

airport for $200 per month.29 Smith and Dayton Airport, Inc., though, had

a

little competition.

The records of the City Manager's Office

contain a proposal from J. H.

Hanauer, Manager, The East Dayton

Airport. In it, Hanauer proposed that the

city lease that field,

"approximately three and one-half miles from the Court

House, over paved roads, which is a

straight and direct route to the intersec-

tion of Third and Main Streets,

requiring eight minutes travel by automo-

bile," as the municipal airport. He

offered the airport to the city for one dol-

lar per year, plus "an annual

maintenance of $1000.00." The city would re-

ceive "all revenue derived from the

passenger and mail lines" while the other

revenues (i.e., from the sale of

gasoline and oil, training fees, etc.) would go

to the operator.30

The available records do not indicate

how much, if any, consideration the

city gave to Hanauer's proposal.

However, by the end of 1933, the city and

Dayton Airport, Inc., were in serious

negotiations over an airport lease.

Interestingly, a December 1933 letter

from Frank Hill Smith to the

Commission offered the Dayton Airport to

the city on much the same terms

offered by Hanauer-a dollar per year,

plus $1000 to cover "legal taxes, insur-

ance, heating and lighting."31

Those terms, however, probably were not in-

spired by the Hanauer proposal. Rather,

they grew out of the circumstances

created in 1933 with the inauguration of

Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal.

By late 1933, the negotiations between

the city and Smith had gained a cer-

tain urgency. As part of his New Deal's

relief efforts, President Franklin

Roosevelt took money from the Public

Works Administration (PWA) and

created the Civil Works Administration

(CWA), designed to spend money

quickly for public works which would

create jobs during the winter of 1933-

1934. In the last months of 1933 both

the city and Dayton Airport, Inc.,

29. Ibid.

30. Proposal, "East Dayton

Airport," no date, Airport Records, Box 1, File 5. The proposal

included an aerial photograph of the

East Dayton Airport which indicated four runways.

Three sod runways fanned out from the

main hangar (two 1800 ft. and one 2300 ft) and the

fourth sod runway, 2300 ft., intersected

the other three.

31. Letter, Frank Hill Smith, President,

Dayton Airport, Inc., to Commission of the City of

Dayton, Dec. 26, 1933, Airport Records,

Box 1, File 5.

|

Dayton's Municipal Airport 135 |

|

were scrambling to establish a situation in which CWA funds could be used to improve the airport. In December 1933, Fred L. Smith, Director of Aeronautics for the State of Ohio, provided the answer. He wrote Eichelberger that CWA labor could be used on the airport property if the city took out a five-year lease. He sent a copy of a lease form which the state of Ohio had prepared for use by other municipalities interested in improving local, privately owned airports.32 Apparently Smith's ideas met with approval as Dayton Airport, Inc., offered to lease its property to the city for $1.00 per year (as recommended in Fred Smith's letter) for five years. This also included an option for the city to buy the property at anytime during the lease for $100,000.33 After some further negotiation, which included some haggling over who paid the taxes, the city and Dayton Airport, Inc., entered into an agreement in March 1934. Under this agreement the city paid "the cost of all insurance they desire to carry on

32. Letter, Fred L. Smith, Director of Aeronautics, State of Ohio, to Mr. F. O. Eichelberger, City Manager, Dayton, Ohio, December 4, 1933, Airport Records, Box 1, File 5. 33. Letter, Frank Hill Smith, President, Dayton Airport, Inc., to Commission of the City of Dayton, Ohio, Dec. 26, 1933, Airport Records, Box 1, File 5. |

136 OHIO HISTORY

the premises, all legal taxes and

assessments, and the sum of $250.00 per

month." The final agreement also

included an option to buy the airport prop-

erty for $85,000.34

After all these frantic efforts, though,

the CWA funding fell through.

However, the city did receive $45,000 in

Federal Emergency Relief

Administration moneys to grade the

field. In June 1935, the Chamber of

Commerce resolved to ask for an

additional $15,000 in FERA moneys to

complete the project. The resolution

also hinted that the Chamber would

seek even more FERA money in the future

in order to build 3,000 ft. run-

ways.35 By early 1936,

however, it became clear that any big money for air-

port improvement would come from the

Works Projects Administration

(WPA), and to get that money, Dayton

would have to own the airport.

Reflecting a general pattern in Dayton's

history, when it became necessary

for the city to purchase the airport,

local business leaders interested in avia-

tion (and not willing to leave such an

important matter to the city's relatively

weak city hall) grabbed the bull by the

horns and in short order handed the

city its new airport.36 The

leader of this particular effort was James M. Cox,

owner of the Dayton Daily News and

the man who headed the Democratic

ticket in 1920 when Franklin Roosevelt

made his bid for the vice-presidency.

In February 1936, Cox, along with Edward

Deeds and E. G. Beichler of

Frigidaire (the latter two among the

original incorporators of the now

bankrupt Dayton Airport, Inc.), called a

Saturday luncheon meeting at the

Biltmore Hotel in Dayton. Many of the

most important businessmen in the

Miami Valley attended this meeting.37

At the meeting, Cox declared he was

concerned that Dayton, the home of

the Wright Brothers, did not have an

airport capable of handling the new,

larger planes carrying transcontinental

passengers and parcels. Upon inquiry

he had found that the government would

not appropriate money for the im-

provement of privately owned airports,

but money was available for public air

fields. Cox then worked his connections

in Washington, among whom in-

cluded President Roosevelt, and received

assurances that if Dayton bought the

Vandalia airport as its municipal

airport it could receive anywhere from

$400,000 to $700,000 from the WPA for

airport improvements. Believing

34. Letter, Frank Hill Smith, President,

Dayton Airport, Inc., to Commission of the City of

Dayton, Ohio, Jan. 2, 1934, Airport

Records, Box 1, File 6; Copy of lease between Dayton

Airport Inc., Frank Hill Smith and the

City of Dayton, March 29, 1934, Airport Records, Box 1,

File 7.

35. Resolution Adopted by Aeronautical Committee

of the Dayton Chamber of Commerce -

June 11, 1935, Airport Records, Box 1,

File 7.

36. Previous to this effort, civic

leaders such as John Patterson, Edward Deeds, and Charles

Kettering had provided the city with a

flood control organization (the Miami Conservancy

District), Wright and McCook Fields,

parks, boulevards, and recreation areas.

37. Article, "Funds of WPA to be

Utilized in Vandalia Project," Sunday, February 16, 1936,

Airport Clipping File, Dayton Main

Library.

Dayton's Municipal Airport 137

the city could not act quickly enough to

meet the funding deadline, Cox called

together the most powerful men in the

Miami Valley and asked them to sub-

scribe to a fund to purchase the

airport. The businessmen would then present

the airport to the city as a gift.38

After speeches from Cox and Deeds

recounting the history of aviation activ-

ities and the role of great business

leaders in bringing aviation and other busi-

ness activities to the Dayton area, the

group at the Biltmore pledged $42,600

toward the needed $65,000. (Somehow they

had negotiated the option price

down from $85,000.) It was clear from

the start that this was not strictly a

Dayton project. Businessmen from

Middletown, Piqua and Troy pledged the

first money for the fund. Other pledges

came from Springfield, Cincinnati

and Miamisburg.39 Either Cox,

Deeds and Beichler had enough clout to at-

tract "outside money" for

their Dayton Airport project or these businessmen,

accustomed to operating beyond their

local level, at least to a certain extent

saw the airport as a regional asset

which they could support. Most probably,

it was the former.

Significantly, during the process under

which the city first leased and then

bought the Vandalia property, the

records included only a couple of messages

from businessmen, both Dayton-based,

opposed to the idea. In 1935, local

architect Harry L. Schenck wrote the

Chamber of Commerce that he had been

an original stockholder in the Dayton

Airport company, having invested

$500. He asserted that he had

reservations about the project from the start be-

cause he "did not consider the

Vandalia location a satisfactory one due to its

distance from Dayton." And he still

felt that any municipal airport should be

much closer to the city. The following

year, in response to the fund-raising

drive, E. G. McCauley, of the McCauley

Aviation Corporation, wrote the

city manager and indicated that he felt

much the same way as Schenck. He

believed that the location in Vandalia

"was a big mistake at the beginning,

and for the future has no advantages to the city as a whole in being so

far re-

mote from the city." McCauley

further stated that he favored the use of the

East Dayton Airport.40

Theirs, though, were lone voices of

dissent. The fund-raising drive suc-

ceeded in very short order, and on April

29, 1936, the group presented the city

with its new municipal airport. Beyond

the narrative of events, the question

remains as to why Dayton's municipal

airport ended up in Vandalia. Given

38. Ibid.; Attachment to Letter, Miriam

Rosenthal to Mayor Louis Lohrey, Dayton Ohio, July

22, 1952, Cox Papers, Box 6, File 9.

39. Article, "Funds of WPA,"

February 16, 1936, Airport Clipping File, Dayton Main

Library; Telegram, James M. Cox to Mr.

Charles J Bevan, February 17, 1936, Cox Papers, Box

6, File 9.

40. Letter, E. G. McCauley, McCauley

Aviation Corporation, to Fred 0. Eichelberger, City

Manager, Dayton, Ohio, Feb. 29, 1936,

Airport Records, Box 1, File 8.

138 OHIO HISTORY

the distance of the airport from the

city, one might ask whether or not it fit

into any regional planning activities in

Dayton and the Miami Valley.

The Airport, Annexation and City

Planning:

Lacking a Regional Vision

Examination of other civic initiatives

during the 1920s and early 1930s, in-

cluding annexation and city planning,

indicates civic leaders in Dayton and its

surrounding area did not envision any

expansion of the city's power or pres-

ence in the Miami Valley or have any

interest in coordinating projects and

improvements on a regional basis. The

Dayton Airport project was, in fact,

an isolated case of the area's

leadership acting on a what might be considered

regional basis, in that contributors to

the fund to purchase the airport for

Dayton came from cities within the Miami

Valley which would not necessar-

ily directly benefit from the project.

More typically, Dayton and Dayton area

business leaders showed very little

interest in either strengthening Dayton's

position within the region or in

implementing any forms of regional plan-

ning. When one looks at concurrent

efforts to expand the city by annexation

or to strengthen or expand planning

powers, the local civic leadership demon-

strated a remarkably consistent lack of

support or even interest.

Throughout the 1920s and into the very

early 1930s Dayton saw several

calls for the city to annex adjacent

areas, particularly the village of Oakwood,

home of many of the area's most

prominent citizens, located just south of

Dayton on land developed largely by John

Patterson, founder of NCR.

Patterson built his home in the Oakwood

hills and insisted that his executives

live in Oakwood. In 1907, Patterson

threatened to move NCR, the city's

largest employer, out of the city unless

Dayton met several demands.

Included was his insistence that Dayton

not annex the Oakwood area and, fur-

ther, allow it to incorporate as a

village. The city agreed.41 After Patterson's

death in 1922, however, several local

leaders came forward to suggest the an-

nexation of Oakwood.

One of the first vigorous campaigns to

convince Oakwood's citizens to ac-

cept annexation came in 1926. In

February, the city manager convened a

meeting of many of the most prominent

citizens of Oakwood and the City

Commission. Included among the attendees

was Frederick B. Patterson of

NCR (who two years later would be one of

the founding members of Dayton

Airport, Inc.). At that meeting,

Eichelberger delivered a speech in which he

strongly encouraged the leaders of

Oakwood to see the value in becoming part

41. Charlotte Reeve Conover, Builders

in New Fields (New York, 1939), 236, 245, 301-14;

Judith Sealander, Grand Plans:

Business Progressivism and Social Change in Ohio's Miami

Valley (Lexington, Kentucky, 1988), 91; Bruce W. Ronald and

Virginia Ronald, Oakwood:

The Far Hills (Dayton, Ohio, 1983), 54.

Dayton's Municipal Airport

139

of Dayton. He argued that by remaining

independent, they were retarding the

growth of Dayton. By accepting

annexation, they would be an example for

the people in other populated districts

who, at that time, were also opposing

annexation. He even laid out a scheme by

which the village of Oakwood

could maintain a separate school

district42. Eichelberger concluded by saying:

Unless all persons who work in Dayton

and really have the welfare of Dayton at

heart will, by becoming part of Dayton

politically, make it possible for them to

take part in the administration of

Dayton's public affairs so the "livable" facilities

may be provided, Dayton will suffer.43

The city manager's pleas fell on deaf or

hostile ears.

The effort did not stop, though. A 1928

letter to the city manager indicated

a Chamber of Commerce concern for

Dayton's showing in the upcoming

1930 census.44 As the time for that all-important head

count grew nearer,

Dayton's assistant City Attorney, Mason

Douglas, launched an aggressive

campaign to convince the leaders of

Oakwood to accept annexation. In April

1930, Douglas wrote the city manager and

requested that he convene another

meeting of Dayton city officials and Oakwood's leadership.

When

Eichelberger failed to respond, Douglas

wrote again, suggesting that the effort

had the support of the Chamber of

Commerce. Apparently, Eichelberger still

failed to respond. The next time Douglas

wrote, he invited the city manager

to a meeting at the Chamber of Commerce

office, scheduled for late May,

where that organization would take up

the topic in a highly confidential meet-

ing. With the Chamber's backing, Douglas

convinced the city manager and

the commission to invite prominent

Oakwood citizens to a confidential meet-

ing on June 20, 1930.45

42. Letter, City Manager (Eichelberger)

to Mr. Oscar Kressler, et al (the files contained

copies of a form letter Eichelberger

sent to 29 individuals; Kressler's letter is the first in the

series), February 9, 1926, City Manager

Records, 1-A-2 1926; List, Attendees at Meeting, no

date, City Manager Records, File l-A-2

1926; Speech, "Dayton's Welfare," no date, City

Manager Records, File l-A-2 1926;

Proposal, "How the Village of Oakwood May Maintain its

Separate School System Even if it is

Annexed to Dayton," no date, City Manager Records, File

l-A-2 1926.

43. Speech, " Dayton's

Welfare," no date, City Manager Records, File l-A-2 1926.

44. Letter, Wayne Ley, Managing

Director, Dayton Chamber of Commerce, to C. D.

Putnam, President, Dayton Plan Board,

February 1, 1928, City Manager Records, File l-A-2

1928.

45. Letter, Asst. City Attorney (Mason

Douglas) to City Manager (Eichelberger), April 14,

1930, City Manager Records, File 1-A-2

1930; Letter, Asst. City Attorney (Douglas) to City

Manager (Eichelberger), April 22, 1930,

City Manager Records, File l-A-2 1930; Letter, Asst.

City Attorney (Douglas) to City Manager

(Eichelberger), May 22, 1930, City Manager

Records, File l-A-2 1930; Letter, City

Manager (Eichelberger) to F. H. Rike, et al (again, this

letter began a series of copies of form

letters sent to at least nine Oakwood leaders, including

F.B. Patterson; a list for the meeting

included 23 names), June 14, 1930, City Manager Records,

File l-A-2 1930.

|

140 OHIO HISTORY |

|

|

|

Extensive lists were drawn up to ensure that all interested parties would be present and invitations sent out. Dozens of local leaders from Dayton and Oakwood attended the June meeting. There Mason Douglas offered an exten- sive statement on the benefits of annexation. He concluded with the follow- ing:

Annexation had effected a united community except for Oakwood. Oakwood can- not indefinitely postpone its community obligation and refuse to become a part of the City of Dayton. It stands before a new community with over 35,000 new citi- zens, and it must waken to the fact that moral responsibility alone points clearly to consolidation. We wish the people of the community and Oakwood to under- stand that we now propose to turn to the problems of consolidating Oakwood and Dayton with absolute confidence that it is inevitable and that intelligent sound thinking will unavoidably lead the citizens of Oakwood to one consideration, that is, that Oakwood cannot exist without Dayton and that there is no justifiable divi- sion existing between the people of Oakwood and the people of Dayton. We see one government, one City, and one purpose in this community and Oakwood is inseparably a part of the community.46

Some of the same people who could think enough in regional terms to site Dayton's airport in Vandalia, including Frederick B. Patterson and Frederick Rike, did not think regionally when it came to their residential enclave. Had the major Oakwood leaders supported annexation, it probably would have

46. Statement by Mason Douglas, no date, City Manager Records, File 1-A-2 1930. |

Dayton's Municipal Airport

141

happened. Clearly, however, they did

not. Following that meeting, twice

Dayton's city manager attempted to set

up a meeting with Oakwood's mayor

and council and twice he was rebuffed.47 The idea of annexing Oakwood faded

from view.

It was much the same story when it came

to city planning. Dayton entered

the 1920s with the reputation of being

one of the nation's most progressive

cities. It had gained that reputation

after becoming the largest US city to

adopt the commission-manager form of

government in 1913. By the early

1920s, however, any progressive impulse

had faded. A late 1930s study of

Dayton's government indicated that after

World War I a sense of "indifferent

complacency" had set in. The

government was competent enough, but took

few initiatives. And Dayton's civic

leaders, most of whom had moved out-

side of the city's limits to Oakwood and

beyond, seemed to have little interest

in local government affairs.48 City

planning efforts received little or no sup-

port from Dayton's most prominent

leaders.

In 1921, Eichelberger replied to a

letter from the Knoxville Board of

Commerce asking for information about

Dayton's city planning efforts. He

wrote:

Very little has been done here in Dayton

along city planning lines. Back in 1918

the City Planning Board was appointed

with a prominent local architect acting as

Secretary. However, owing to lack of

funds, very little was done by this Board.

They did, I believe, draw up some sort of comprehensive

City plan but that is as far

as it went. At the present time this

Board is not functioning so that we really have

nothing of value to show in this work.49

Eichelberger sent out other, similar

letters in 1922 and 1923. Generally they

informed the inquirer that Dayton had no

city planning board and no funds

with which to conduct city planning

activities.

47. Letter, City Manager (Eichelberger)

to Lowell P. Rieger, Mayor, Oakwood, August 11,

1930, City Manager Records, File 1-A-2

1930; Letter, Lowell P. Rieger, Mayor of Oakwood, to

F. O. Eichelberger, City Manager,

Dayton, Ohio, August 19, 1930, City Manager Records, File

l-A-2 1930; Typewritten Statement,

untitled, August 22, 1930, City Manager Records, 1-A-2

1930.

48. Landrum R. Bolling, "City

Manager Government in Dayton," in Mosher, et al, City

Manager Government in Seven Cities (Chicago, 1940), 296, 322.

49. Letter, City Manager (Eichelberger)

to Mr. J. T. Badgley, Knoxville Board of

Commerce, November 8, 1921, City Manager

Records, File 8-F 1921.

50. See Letter, City Manager

(Eichelberger) to Mr. W. H. Reid, City Manager, Bay City,

Michigan, February 4, 1922, City Manager

Records, File 8-F 1922; Letter, City Manager

(Eichelberger) to Mr. Campbell Scott,

President, Technical Advisory Corporation, February 27,

1922, City Manager Records, File 8-F

1922; Letter, City Manager (Eichelberger) to Mr. C. E.

Rightor, Detroit Bureau of Governmental

Research, January 29, 1923, City Manager Records,

8-F 1923; Letter, City Manager

(Eichelberger) to Mr. William W. Trench, Acting Secretary,

City Planning Commission, Schenectady,

New York, July 23, 1923, City Manager Records, File

8-F 1923; Letter, City Manager

(Eichelberger) to Miss Anne Robertson, Secretary, City

Planning and Zoning Commission, New

Orleans, Louisiana, September 26, 1923, City Manager

142 OHIO HISTORY

The City Commission did appoint a new

City Plan Board in 1924. The

following year the board contracted with

the Technical Advisory Corporation

of New York to develop a zoning

ordinance for the city, which the city

adopted on May 9, 1926. This proved one

of its few accomplishments. In

late 1926, it also accepted four

chapters of a comprehensive city plan from the

Technical Advisory Corporation, but the

records do not indicate that the pro-

posed plan prompted much action. Then in

1928, as a small group of civic

leaders were establishing a municipal

airport far beyond the city boundaries,

the City Plan Board did issue a call for

regional planning. But that was as far

as it ever went.51 Apparently

when it came to annexation or city planning,

Dayton's business leadership showed

scant support and virtually no interest.

Finally, even proponents of making

airports part of a regional planning

scheme would not necessarily have

supported the placement of Dayton's air-

port so far from the center of the city.

In the late 1920s, Henry Hubbard,

Miller McClintock and Frank B. Williams

from the Harvard University

School of City Planning, made a study of

the nation's airports. In it they de-

clared that "the location of the

airport should be considered in relation to a

consistent city and regional plan."

While speaking of the placement of the

airport, they concluded that the

"airport should be as near the center of the

town as possible. A greater

transportation time than fifteen minutes from the

center of the city to the airport would

in all probability be a serious detri-

ment."52 Those opposed to the Vandalia Airport indicated that it took

longer

than fifteen minutes to reach the

airport and that the location was too remote.

Echoing the Hubbard study, they, too,

believed a municipal airport should be

less than fifteen minutes travel time

from the center of town.53

Thus, the siting of Dayton's airport did

not reflect a case of regional plan-

ning. Although its location suggested it

served Dayton's region, more so

perhaps than the city, and in 1936 it

drew its financial supporters from across

the Miami Valley, the airport stood as a

false beacon of regional planning be-

cause no real concern for using the

airport to develop Dayton and its region

underlay its establishment. So, if what

became Dayton's municipal airport

Records, File 8-F 1923.

51. Letter, Clerk of the Commission to

City Plan Board, April 10, 1924, City Manager

Records, 8-F 1924; Letter, Clerk of the

Commission to City Manager (Eichelberger), January

28, 1925, City Manager Records, File 8-F

1925; Letter, City Manager (Eichelberger) to City

Commission, August 26, 1925, City

Manager Records, File 8-F 1925; Report, "Four Chapters of

Comprehensive City Plan Submitted by

Technical Advisory Corporation," December 28, 1926,

City Manager Records, File 8-F 1926;

Report, "Projects Which Need the Attention of the City

Plan Board During the Coming Year,"

no date, City Manager Records, File 10-B 1928.

52. Henry V. Hubbard, et al, Airports:

Their Location, Administration and Legal Basis

(Cambridge, Mass., 1930), 20.

53. Letter, E. G. McCauley, McCauley

Aviation Corporation, to City Manager Fred C.

Eichelberger, February 29, 1936, Dayton

Airport Records, Box 1, File 8.

Dayton's Municipal Airport 143

did not reflect a case of regional

planning, why did Dayton end up with a mu-

nicipal airport eleven miles outside of

the city?

Personalities and Technology:

Locating Dayton's Airport

As noted in the introduction, the

Vandalia airport site won the contest for

municipal ownership because it had the

most powerful backers and because its

proponents understood the aircraft

technology of the late 1920s, when the air-

port was first established. Indeed, the

airport's planners seemed more con-

cerned with meeting the needs of the

airlines and their pilots than of the city

of Dayton.

The Vandalia airport site backers

included some of the most powerful busi-

ness leaders in the Dayton area. These

men, especially Edward Deeds and

Frederick Patterson, were accustomed to

getting what they wanted from the

city. It was doubtful that any other

combination of businessmen within the

city could have matched the founding

members of Dayton Airport, Inc., in

power or prestige. And it was unlikely

that the city would refuse them once

they decided to establish a municipal

airport. In fact, in the end, the city had

little choice. The owners of the airport

first decided where it would be located

and then they and their powerful

associates, once the private venture had

clearly failed, decided that their

airport near Vandalia would be purchased and

presented to the city as its municipal

airport.

Also an important factor, aircraft

navigation equipment was still very much

in the developmental stage in the late

1920s. During the 1920s aircraft tech-

nology had advanced rapidly, but most

flying was still done under visual

flight conditions. In other words the

pilot needed to see the ground (and the

horizon) to keep the plane level, and

most navigation depended on sighting

visual landmarks. Instrumentation was

improving, but at the time of the ini-

tial establishment

of the Dayton Airport in 1928, full instrument flying was

still very much in the experimental

stage. Powerful beacons did allow for

night flying, but the pilot still had to

see the beacon. Flying was still a fair-

weather, visual enterprise in 1928.

Technology would improve, but radio

navigation aids were still several years

in the future.54

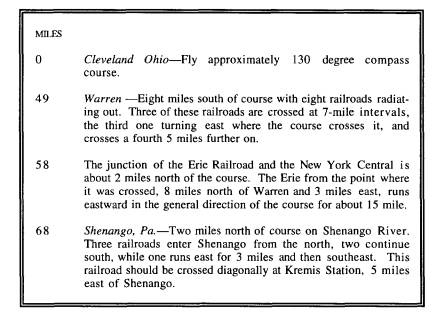

In 1921 the US Post Office printed a set

of directions for pilots flying the

new transcontinental airway. Dayton was

not on that airway, but a part of

the directions followed by pilots

between Cleveland, Ohio, and Bellefonte,

Pennsylvania, provides a glimpse into

the conditions under which pilots flew

54. General James H. "Jimmy"

Doolittle with Carroll V. Glines, I Could Never Be So Lucky

Again (New York, 1991), 129-53; Nick A. Komons, Bonfires

to Beacons: Federal Civil

Aviation Policy Under the Air

Commerce Act, 1926-1938 (Washington,

D.C., 1989), 125-47.

|

144 OHIO HISTORY |

|

|

|

their aircraft during the 1920s.55 Clearly landmarks, such as railroads, played an important role in moving the mail by air. The Vandalia location served the airlines' need for visual landmarks. As noted in a local newspaper article, the airport site was near the intersection of "two of the most famous highways in America-the National Road leading east and west and the Dixie Highway leading north and south."56 Aircraft fly- ing between Columbus and Indianapolis, for example, could follow the National Road and those flying between Cincinnati and northern Ohio could follow the Dixie Highway. In either case they would not have to divert from a relatively straight course in order to land at the Dayton Airport. Frank Hill Smith reiterated the value of this location in a 1933 letter to the City Commission. That location, in part, gave the Dayton Airport "a high rating for accessibility thruout [sic] the year."57 Two years before the drive to purchase the airport for the city, the continued dangers of night and weather flying were dramatically illustrated. In 1934, in response to a scandal within the Post Office over the methods by which air-

55. William M. Leary, Pilots' Directions: The Transcontinental Airway and its History (Iowa City, 1990), 53. 56. Article, "Dayton Boasts of Sixth Air Station," no date, Airport Clipping File, Dayton Main Library. 57. Letter, Frank Hill Smith, President, Dayton Airport Inc., to City Commission of Dayton, Ohio, February 21, 1933, Dayton Airport Records, Box 1, File 5. |

Dayton's Municipal Airport 145

mail contracts were awarded, President

Franklin Roosevelt canceled all the ex-

isting airmail contracts and turned over

responsibility for flying the mail to

the Army Air Corps in mid-February 1934.

Unlike the airlines, which flew

some of the most advanced equipment

available and relied on extensive train-

ing, the Air Corps took on the job in

the dead of winter flying badly out-of-

date 1920s vintage aircraft. The death

toll mounted rapidly. By mid-March,

the president ordered the Army to fly

only during the day. Crashes continued,

however, and shortly thereafter the

Roosevelt administration made arrange-

ments to return the airmail contracts to

private carriers.58 Thus, even as late

as the mid-1930s, night and weather

flying by instrument still, in many

ways, represented the cutting edge of

technology.

Conclusion

Dayton's business leaders provided the

city with an airport which by its lo-

cation served primarily the needs of the

airlines. The airport's location did

not reflect a regional planning

initiative, nor did it tend to spark interest in

any regional planning which might have

worked to draw the people of the

Miami Valley closer together.

Dayton's airport was located at

crossroads-a crossroads of technology and

a crossroads of two major highways. The

airport, now known as Dayton-Cox

International, still serves as the

municipal airport, but even today, while not a

failure, it has still not lived up to

any expectations, explicit or implied, of

greatly furthering the development of

Dayton and its region. In some ways it

is still a false beacon of the

possibilities of regional planning.

58. Smith, Airways, 249-58.