Ohio History Journal

EARL IRVIN WEST

Early Cincinnati's

"Unprecedented

Spectacle"

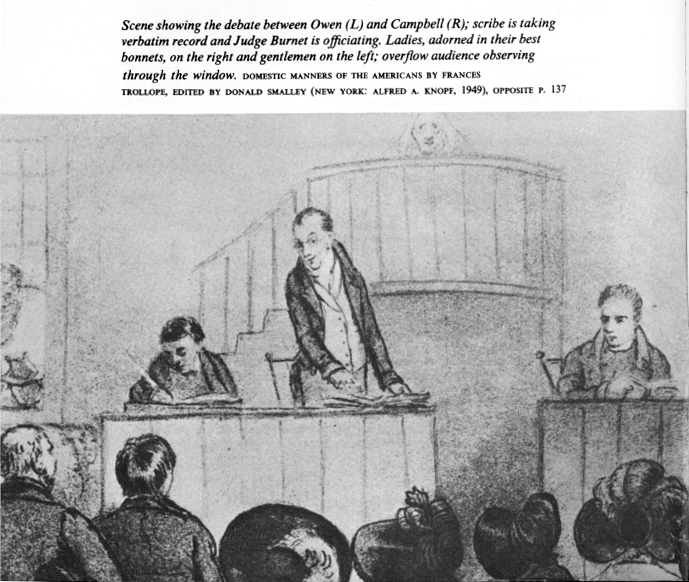

When Isaac G. Burnet, Cincinnati's newly

elected mayor, called a meeting of the

city's leading citizens for Tuesday

night, April 7, 1829, to make arrangements for

a debate between Robert Owen and

Alexander Campbell, this can be considered

an official sanction for the

extraordinary event that was being planned.1 Robert

Owen, social reformer, lecturer, and

founder of the then defunct communitarian

colony at New Harmony, Indiana, had

issued a general challenge a year earlier

from New Orleans to the Christian clergy

to defend religion in debate. The invi-

tation had been accepted by Alexander

Campbell of Bethany, (West) Virginia,

editor of the Christian Baptist, an

aggressive periodical, dedicated to non-sectarian

religion. After reading Owen's challenge

and Campbell's reply, the mayor requested

that notices be placed in all the city

papers and that interested citizens should

meet again to continue plans for the event.

Accordingly, a committee of ten was

appointed to select a site for the

debate with instructions to request the First Pres-

byterian Church for use of its

facilities. The pugnacious and independent Joshua

L. Wilson, minister of that church and

leader of Old School Presbyterians in the

western country, rejected this request.

The committee then turned to the Methodist

Church, "a capacious stone building

with brick wings" located on Fifth Street,

between Sycamore and Broadway and

capable of seating a thousand people.2

The debate, which Frances Trollope

called "a spectacle unprecedented, I believe,

in any age or country," began on

Monday, April 13th and ended on the following

Tuesday, April 21 after fifteen

sittings.3 Timothy Flint, ex-Congregational minister

and one of the moderators, was impressed

that the audience "received with invin-

cible forbearance, the most frank and

sarcastic remarks of Mr. Owen, in ridicule

of the most sacred articles of Christian

belief." Afterwards, a foreigner remarked

to Flint "that he had seen no

place, where he thought such a discussion could have

been conducted in so much order and

quietness."4

1. Cincinnati Daily Gazette, April

9, 1829. Debates on religious topics became commonplace in

later years.

2. Ibid., April 11, 1829.

3. Frances Trollope, Domestic Manners

of the Americans, edited by Donald Smalley (New York,

1949), 147-153.

4. Timothy Flint, "Public

challenged DISPUTE between ROBERT OWEN . . . and Rev. ALEX-

ANDER CAMPBELL . . . the former denying

the truth of all religions in general; and the latter

affirming the truth of the Christian

.religion on logical principles," Western Monthly Review, II

(April 1829), 646. Flint's article also

appears in Washington National Intelligencer, May 26, 1829.

Mr. West is professor of church history

at the Harding Graduate School of Religion, Memphis,

Tennessee.

6

OHIO HISTORY

An over-capacity attendance of twelve

hundred at each session attests to the

importance the public attached to the

discussion, although opinions varied greatly.

Writing in advance of the event, Robert

Dale Owen, son of Robert Owen, thought

the debate would have "claim

sufficient to attract the attention of every enlight-

ened man." He regarded the subject

to be discussed as "the most important . . .

that can be brought before a public

assembly." "Its influence extends," he said

presciently, "to the cabin of the

peasant as to the hall of kings."5 Flint himself

regarded it as a "combat,

unparalleled in the annals of disputation."6 On the other

hand, the editor of Washington's National

Intelligencer said, "Upon our word, we

think that the good people of Cincinnati

might be much more profitably employed

than in encouraging this bootless

wrangling."7 Cincinnati's caustic visitor, the Eng-

lishwoman Frances Trollope, reflected

later, "All this I think could only have hap-

pened in America. I am not quite sure

that it was very desirable it should have

happened anywhere."8

While the debate was not as epic-making

as Campbell's friends thought, the

united stand for Christianity on the

final day did indicate an interest by the con-

temporary westerner in religion beyond

the sheer novelty of the performance. Re-

ports had circulated in the eastern

religious press that infidelity was widespread

on the frontier, and Campbell's

biographer states that the clergyman did not hope

to convert Owen but went to fortify a

"wavering and unsettled public," which he

regarded as in danger of being carried

off by infidelity.9

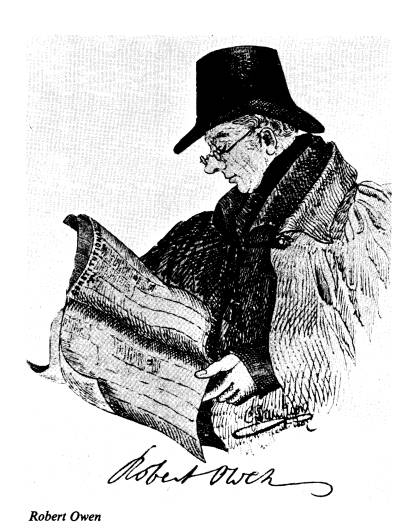

Another aspect of the attractiveness of

the debate was the presence of the color-

ful personality of the internationally

famous Robert Owen. Born in 1771 in New-

ton, Montgomeryshire, Wales, the son of

a saddler and ironmonger, the precocious

boy proved such a voracious reader that

he dropped out of school at the age of

nine, and, some said, gave up all

religious dogma by the age of ten. He borrowed

freely from private libraries and argued

religion sharply with three Methodist

ladies who had loaned him books. At the

age of ten he went to live briefly with

his brother in London, and from there he

went to Lincolnshire and later to Man-

chester. These were important years in

Owen's development for he continued his

study of the beliefs of various sects

and also attended both the Presbyterian and

Anglican churches where he heard

"conflicting doctrines." In abandoning all reli-

gious beliefs Owen concluded that

differences in religion were due to the influence

of social institutions. It was not until

1817, however, that Owen would publicly

attack religion.

The knowledge Owen gained at Manchester

while working in the cotton indus-

try, meanwhile, laid the foundation for

his later wealth and renown. Before he was

twenty he was managing one of the city's

largest mills. In the 1790's, his fortune

grew steadily. His business ability led

him, in January 1800, to become manager

of the New Lanark mills in Scotland with

a salary of one thousand pounds and a

5. New Harmony Gazette, August 6,

1828, p. 326.

6. Flint, "Dispute Between Owen and

Campbell," 641.

7. National Intelligencer, April 21, 1829.

8. Trollope, Domestic Manners, 153.

9. Robert Richardson, Memoirs of

Alexander Campbell (Cincinnati, 1872), II, 269. A Presbyterian

paper published a jeremiad on the rapid growth of

infidelity in Kentucky. See the Pittsburgh Recorder,

II (November 6, 1823). A report of the

American Home Missionary Society said of the West in 1841,

'Mormonism is there to delude them. Popery is there to

ensnare them. Infidelity is there to corrupt

and debase them. And Atheism is there

to take away their God as they go on to the grave, and to

blot out every ray of hope that may beam

on them from beyond.' Quoted in Robert E. Reigel,

Young America, 1830-1840 (Norman, Okla., 1949), 257.

Cincinnati Spectacle 7

ninth interest in the partnership that

owned both factory and village. His marriage

to the daughter of David Dale, the

original owner, satisfied a social expectancy,

but between husband and wife there was

little rapport. Her devout Scotch Presby-

terianism could never add substance to

the dream world in which Owen increas-

ingly resided. Driven on by the

irresistible force of a magnificent illusion, Owen

sought the limelight of European and

American political institutions, while his

wife walked silently in the lonely

shadows he cast behind.

New Lanark was an isolated mill town of

two thousand, of which more than

five hundred were children who had been

brought from poor homes in Glasgow

and Edinburgh. The situation was one of

child labor, immorality, crime, drunken-

ness, and laziness-all contributing to

the squalor and diminishing productivity.

The determined enthusiasm with which

Owen proceeded to improve these condi-

tions was motivated partly by the desire

for increased efficiency of operation and

partly for social reform. From Owen's

viewpoint the inhabitants were trapped in

a network of circumstances beyond their

control; consequently, they were not

responsible for either their vices or

virtues. He would often repeat in monotonous

staccatos: "Character is

universally formed for and not by the individual." It is

impossible to overstate Owen's fondness

for this expression, by which he meant

that if men were placed in the right

environment, they would develop the proper

moral ideas and order their lives in a

productive way. Unlike the French Physio-

crats, who conceived of the true role of

government to be the adjustment of the

social order to a basic natural order,

Owen sought to control the forces of nature

in the common interest.10

Owen worked sedulously to create a new

social order around New Lanark. He

instituted a compulsory education

system, one of the first in the world. For the

smaller children he began a

kindergarten. Not only did he provide better housing

for families, but he started a health

fund. His patriarchal instincts served him well;

and in time, through his vigorous

leadership, immorality diminished, crime was

cut sharply, and the whole complexion of

the village changed. New Lanark came

to be regarded as one of the most

efficient mills in Europe. Since England's Indus-

trial Revolution had created in many

areas the problems Owen saw upon his

arrival at New Lanark, his social

experiment invited closer inspection from phi-

lanthropists and businessmen everywhere.

This remarkable achievement, however,

was not the fruit of wholehearted

cooperation. Owen's partners, who were

understandably concerned more with

profits than with social reforms,

complained incessantly of the high costs of opera-

tions. Jeremy Bentham had invested ten

thousand pounds in Owen's mills and

became one of the reformer's most vocal

critics. "Owen," said Bentham, "begins

in vapour and ends in smoke. He is a

great braggadocio; his mind is an image of

confusion, and he avoids coming to

particulars. He is always the same, says the

same things over and over again; he

built some small houses, and people who had

no houses of their own went to live in

those houses, and he calls this success."

Owen, on the other hand, continued his

dreams of villages where 'the meanest

10. G. D. H. Cole, Life of Robert

Owen (London, 1930), 3, 10, 39. Cole observed that Owen was

"from first to last a deeply

religious person, not least when he was denouncing all the creeds, and

earning the reputation of an infidel and

a materialist." See also Arthur Eugene Bestor, Jr., Back-

woods Utopias; The Sectarian and

Owenite Phases of Communitarian Socialism in America: 1663-1829

(Philadelphia, 1950), 62-63.

8

OHIO HISTORY

and most miserable beings now in society

will . . . become the envy of the rich

and indolent . . .'11

The New Lanark reformer then pursued his

expanding vista with absolute dedi-

cation. In 1813 he published his A

New View of Society in which he declared that

character is formed in childhood

entirely by environment. It is pointless to perse-

cute people who commit crimes, he

pointed out, for they are not responsible. The

object of his new society would be to

prevent crime by proper training in early

life. In January 1815, in a bill

sponsored by Sir Robert Peel, Owen tried to get a

measure through the House of Commons

which would have limited children's

working hours. The bill failed, and the

Factory Act of 1819, a drastically altered

version, displeased Owen. He, however,

drove relentlessly forward.12

To sell churchmen and statesmen on his New

View became a principal feature

of his modus operandi. Owen

visited John Quincy Adams in London in 1817 while

the latter was serving as American

minister to England. Adams wrote in his diary

that the reformer was a

"speculative, scheming, mischievous man." When Owen

visited him in Washington in 1844, Adams

wrote that he appeared "as crafty

[and] crazy as ever."13 When

Owen visited Washington on his trip to New Har-

mony in 1824, the two discussed

religion. Adams never relented in his opposition

to Owen's social system after that, and

referred to Owen's state of mind as "ra-

tional insanity."14 Nor were some

other prominent Americans better impressed.

The turning point in Owen's career came

during an address which he delivered

at the City of London Tavern, August 21,

1817. When asked why his new views

had not been adopted earlier, Owen

replied it was because of the errors of reli-

gion, the crucial one being the

preaching of the doctrine of human responsibility.

In reality men were creatures of their

environment, but the churches taught that

men made their own character. They

sought through doctrines of rewards and

punishments to provide proper

motivation, "whereas the only sound way of mak-

ing men good was to give them a good

material and moral environment, . . . they

would become good automatically."

To Owen all theologies "proceeded from the

deluded imagination of ignorant

men." He considered the priesthood as the chief

of Satanic institutions, and concluded

that "man is a geographical animal, and the

religions of the world are so many

geographical insanities."15 As Owen expanded

his views, he denied that the Bible was

the revelation of "the mind and will of

God," that there was any truth to

the Calvinist doctrines of original sin and pre-

destination, or that the soul was

immortal. He stated flatly that matter was eternal,

and there was nothing but matter in the

universe, and that the bodies men now

have may continue in other forms and

animals.16

11. Arthur J. Booth, Robert Owen, The

Founder of Socialism in England (London, 1869), 27, 28;

quoted in Bestor, Backwoods Utopias, 73.

12. J. Bronowski and Bruce Mazlish, The

Western Intellectual Tradition, from Leonardo to Hegel

(New York, 1960), 456.

13. Charles Francis Adams, ed., Memoirs

of John Quincy Adams: Comprising Portions of his Diary

from 1795 to 1848 (Philadelphia, 1877), XII, 116, 117.

14. John Q. Adams to Rev. Bernard

Whitman, December 25, 1833. The Adams Family Papers,

Massachusetts Historical Society. (The

author used the microfilms of this collection in the Indiana

University library.)

15. Cole, Life of Robert Owen, 22,

192, 93; Booth, Robert Owen, 4; Marguerite Young, Angel in

the Forest: A Fairy Tale of Two

Utopias (New York, 1945), 268-269.

16. Timothy Flint, "A Tour," Western

Monthly Review, II (September 1828), 198-201; Christian

Messenger, II (January 1827), 44-46; Indianapolis Journal, February

21, 1826.

Cincinnati Spectacle 9

The religious press responded to Owen's

attacks with a sustained cataract of

malevolence. The Christian Observer, in

October 1817, linked Owen with Voltaire,

Condorcet and Paine, and denounced him

for saying that religious teaching fos-

tered false views of human nature and

perpetuated 'superstition, bigotry, hypoc-

risy, hatred, revenge, wars, and all

their evil consequences.17 But it was Owen's

rejection of the doctrines of human

depravity and original sin that touched a sore

point, because the liberals thought the

orthodox Calvinists were using these highly

incendiary issues as a stalking horse to

attack them. Nevertheless, Owen's "Decla-

ration of Mental Independence"

nearly united all religious forces against him.

Selecting July 4, 1826, the fiftieth

anniversary of the Declaration of Independ-

ence, as the auspicious moment for his

announcement, Owen stated his intention

of freeing the world of three evils: private

property, irrational systems of religion,

and marriage.

I now Declare, to you, and to the world,

that Man up to this hour, has been, in all parts

of the earth, a slave to a TRINITY of the most monstrous evils that could be

combined to

inflict mental and physical evil upon

his whole race.

I refer to Private, or Individual

Property--ABSURD AND IRRATIONAL SYSTEMS OF RELI-

GION--AND MARRIAGE, FOUNDED ON

INDIVIDUAL PROPERTY COMBINED WITH SOME ONE OF

THESE IRRATIONAL SYSTEMS OF RELIGION.18

It was a basic presupposition during

this period that the American nation was

built on the foundation of good morals

and that morality could be equated with

religion.19 A correspondent

from South Carolina wrote to the New Harmony

Gazette in October 1827 that "religion is in the

estimation of most thinking men

the only efficient sanction of moral

obligation."20 A cloud hung over the Indiana

colony in the minds of most Americans.

Because it lacked the cohesive element of

morality, predictions of its imminent collapse

increased.

The intellectual appeal Owen lacked was

compensated for in personal qualities.

Most Americans regarded him, as did

Timothy Flint, an "honest enthusiast, whose

real intentions were the good of

mankind."21 His sparkling conversation, air of

suavity, perfect self-command, and

constant good humor brought him wide public

esteem. He was always optimistic, for

the milennium was always just ahead, and

"he was running so fast towards it

that he had no time to notice the pitfalls in the

way."22 He was almost totally free

of anger and preferred to sum "pure and genu-

ine religion" into one word, "Charity."23 While Mrs.

S. H. Smith, that connoisseur

of minutiae in Washington society,

thought he was "ugly, awkward, and unpre-

possessing, in manner, appearance and

voice, she thought him very interesting in

17. Quoted in Bestor, Backwoods

Utopias, 124.

18. Timothy Flint, "New views of

society; or Essays on the formation of human character, etc.

Various addresses delivered by Mr. Owen,

dedicated to those, who have no private ends to accom-

plish, and who are honestly in search of

truth, etc.," Western Monthly Review, I (June 1827), 105-118;

Young, Angel in the Forest, 233,

quoted from the National Intelligencer, August 3, 1826.

19. Sidney Mead, The Lively

Experiment: The Shaping of American Christianity (New York, 1963),

53; Perry Miller, The Life of the

Mind in America: From the Revolution to the Civil War (New York,

1965), 67-69.

20. New Harmony Gazette, November

28, 1827.

21. Flint, "New Views," 118.

22. Cole, Life of Robert Owen, 34.

23. National Intelligencer, August

12, 1826.

10 OHIO

HISTORY

conversation." After her visit with

him, she was convinced that he was devoted to

the all-absorbing idea of promoting the

happiness of mankind. "He is extremely

mild," she wrote, "and instead

of being offended by opposition or difference of

opinion he is pleased with free

discussion and even bears being laughed at, with

great good nature."24 In

short, Owen was one of the most fascinating and unique

personalities ever to visit the country.

His trip to America to inaugurate the New

Harmony project was one continuous

triumphal march during which time he

addressed the nation's leaders.

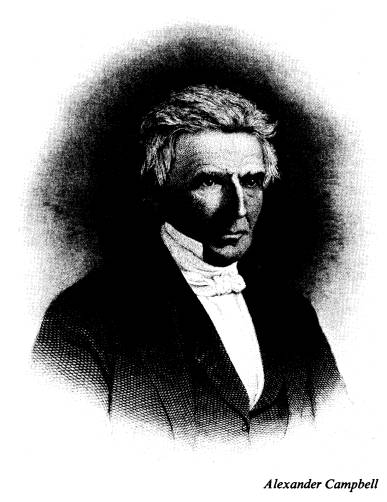

The path that led Alexander Campbell to

Cincinnati on that April day in 1829

was in sharp contrast to that of his

challenger. Born near Ballymena in County

Antrim, North Ireland, September 12,

1788, he was reared in the pious atmosphere

of a Scotch Presbyterian home. His

father, an Old Light Seceder Presbyterian, and

his mother, a descendant of a French

Huguenot family, guided their son toward

an academic career that was heavily

oriented toward theological studies. Under

his parents' guidance he memorized large

selections from the Bible and augmented

his studies by attendance at a local

academy. Although his father wanted him to

enter the ministry of the Seceder

Church, Alexander hesitated while he sought for

solutions to the problems raised by

variations in religious dogmas. While he searched

for answers, his father joined the

Scotch-Irish immigration to America in 1807,

and Alexander waited with the family in

Ireland for an appropriate time to follow.25

During the next three eventful years,

Alexander shifted his theological position

away from the Seceders toward

Independency. He spent a year at the University

of Glasgow where he came under the

influence of Greville Ewing, a well-known

Scotch Independent. His contact with the

teachings of James and Robert Haldane

and those of John Glass and Robert Sandemann

left a lasting impression on his

religious thought. In Ireland, Campbell

belonged to the Presbytery of Market Hill,

and in Scotland, to that of Glasgow,

keeping himself in good standing with the

Seceder Church. Upon his departure from

Scotland, however, he confessed that his

confidence in the Confession of Faith

was shaken. When he arrived in Washington,

Pennsylvania, in the fall of 1809, he

was "under the conviction that nothing that

was not as old as the New Testament

should be made an article of faith, a rule of

practice, or a term of communion amongst

christians."26

While completely dedicating himself to

religious service for the next decade,

Campbell at the same time established a

reputation for being an independent thinker.

At the close of a discourse on "The

Sermon on The Mount," which he delivered

to the Brush Run church near his home at

Bethany, near Wheeling, Virginia, in the

summer of 1810, he stated his

convictions of the independence of the church of

Christ from any denominational

connections and "the excellency and authority

of the scriptures." During that

year he delivered 106 sermons on sixty-one "pri-

mary topics of the Christian

religion" in the western part of Pennsylvania, Virginia,

and eastern Ohio. Meanwhile, his fame as

a preacher of unsurpassed talents and

boldness of thought grew.27

24. Margaret B. Smith, The First

Forty Years of Washington Society . . ., edited by Gaillard Hunt

(New York, 1906), 179, 222.

25. The standard biography of Alexander

Campbell is Richardson's Memoirs of Alexander Camp-

bell.

26. Alexander Campbell, "Address to

the Public," Christian Baptist, II (1824) in bound volume,

revised by D. S. Burnet (Cincinnati,

1835), 92.

27. Ibid.

Cincinnati Spectacle 11

When Campbell was immersed by Elder

Matthias Luse in 1812, his relations

with the Presbyterians were broken; at

the same time, he was drawn into the Red-

stone Baptist Association. His famous

"Sermon on The Law," which he delivered

before the Association in the summer of

1816, only accented how tenuous this

connection really was. By the time of

his debate with W. L. McCalla, a vitriolic

Old School Presbyterian, in 1823,

Campbell and his colleagues in the Baptist

ministry glowered at each other over a

chasm of distrust and suspicion.28

After a short fling with politics in

1829, the minister devoted his entire atten-

tion to what he called a religious

reformation. His teachings, a syncretistic system

that combined elements from many

religious dogmas, began with a fundamentalist's

view of the Bible as the inspired word

of God; as a result, only doctrines and

practices which he considered to be

founded on the Bible could be accepted. He

considered the "three great maxims

. . . which have been three cardinal points in

our theological compass" to be:

"The testimony of God believed constitutes Chris-

tian faith; The testimony of God understood

constitutes Christian knowledge;

and The testimony of God obeyed constitutes

Christian practice."29 E. D. Mansfield

heard Campbell several times in

Cincinnati between 1826 and 1829 and summarized

his doctrines to be: "The Bible

alone is the only creed . . . regeneration is coincident

with baptism." Campbell, he

concluded, "was a man of learning, keen intellect,

and an instructive speaker. He was

interesting in discussion and conversation."30

Although Campbell was much admired, his

unique system, his excessive self-

confidence, and strong derogations

invited vigorous opposition, particularly from

the Baptists. John Waller complained

that Campbell "seems to have imbibed the

impression that he was a chosen vessel

of the Almighty, appointed to set in order

the crazy concerns of Christendom which

had been in mournful confusion since the

age of the apostles."31 After admitting

that Campbell was "a polemic ajax in the

region where he began the propagation of

his tenets," another Baptist minister

recognized that Campbell was

"incisive in sarcasm and caricature, shrewd in repar-

tee, and possessed of an overwhelming

confidence in his ability."32 Campbell, in

fact, could scarcely be ignored.

Americans on the western frontier, as a

Louisville Unitarian minister said, "have

a taste for oratory," which partly

explains Campbell's popularity as a speaker. His

lofty diction which tended often to

become excessively sublime and verbose fol-

lowed the general pattern of Henry Clay.

Like the Kentucky orator, Campbell stood

erect and made few gestures. As his

deep-set eyes pierced the audience, his Scotch-

Irish brogue poured forth a stream of

eloquence. One listener said, "The great

excellence of Campbell's delivery,

consists in the feeling which it inspires, of his

manly independence, entire conviction of

the truth of what he says, and entire

understanding of his whole subject. He

is plain, forcible, and self-possessed; he is

28. Alexander Campbell, "Anecdotes,

Incidents, and Facts," Millennial Harbinger, V (June 1848),

344-349. For a discussion of New and Old

School Presbyterian division, see "Rankin Autobiography,"

fn. 19, in this issue.

29. Alexander Campbell, "Andrew

Broadus Against Himself," Millennial Harbinger, III (April

1832), 151.

30. E. D. Mansfield, Personal

Memories: . . . with Sketches of Many Noted People, 1803-1843 (Cin-

cinnati, 1879), 272.

31. John N. Waller, "Messrs.

Campbell and Rice on Influence of the Holy Spirit," Western Baptist

Review, I (September 1845), 23.

32. B. F. Riley, A History of the

Baptists in the Southern States East of the Mississippi (Philadel-

phia, 1898), 174.

12 OHIO HISTORY

not hurried away by his words or by his

thoughts, but has the command of both."33

Alexander Campbell's popularity on the

frontier, both as a unique religious leader

and eloquent speaker, lured Cincinnati's

citizens to this "unprecedented spectacle"

as much as the singular career of the

socialist reformer.

By the spring of 1827 it seemed evident

that the courses of the two men would

ultimately converge. Campbell had read

in the New Harmony Gazette Owen's

"Declaration of Mental

Independence." Since he desired to get better acquainted

with Owen before establishing his

opinions too securely, he formed only two

quick impressions: He agreed that

circumstances do influence character, but felt

that Owen had glorified this principle

excessively to the exclusion of other valu-

able considerations. "To make

everything in human character depend upon the

power of circumstances, is to me as

great an error as to making nothing depend

on it."34 Furthermore,

he agreed with most American religious leaders that it had

never been demonstrated that a social

system could be successful without religion.

On this basis, Campbell rejected Owen's

"Declaration of Mental Independence" as

contrary to the events of human history.

The principles on which New Harmony

had been established, he thought, were

"at war with reason, revelation, and a

permanent cooperation."35 In

a series of articles in the Christian Baptist through

the summer and fall of 1827 Campbell

defended religion as a necessary base for

any social system.

Campbell's hostility to the Owenite

communitarian system intensified during

the next year. A Dr. Underhill from an

Owenite community at Kendal in Stark

County, Ohio, popularized Owen's views

in the state. When a reader of the Chris-

tian Baptist requested Campbell in February 1828 to debate this man,

Campbell

refused, but, answering in April, said

if Robert Owen "will engage to debate the

whole system of his moral and religious

philosophy with me, if he will pledge

himself to prove any position

affirmative of his atheistical sentiments as they lie

scattered over the pages of the New

Harmony Gazette . . . I will engage to take

the negative and disprove all his

affirmative positions, in a public debate to be

holden any place equi-distant from him

and me."36

Owen was well aware that his New Harmony

experiment had failed when he

arrived in New Orleans from Liverpool in

early January 1828. Nevertheless his

dreams of another colony were rekindled

when he learned of the population growth

in Texas, and of the land grants given

to settlers by the Mexican Government.

Meanwhile, he saw it was necessary to

popularize his views as extensively as pos-

sible. In the next three weeks he told

New Orleans audiences that he had spent

more than $500,000 and devoted forty

years of his life to making his ideas a

reality. He invited "all

governments and enlightened people" to stop wars by fol-

lowing principles "which are in

strict accord to our natures." Then, in late January,

an advertisment appeared in the papers,

addressed "To the Clergy of New Orleans":

33. J. F. C., "Alexander Campbell

at Louisville," Western Messenger, I (June 1835), 57, 58.

34. Alexander Campbell, "Mr. Robert

Owen and the Social System, No. 1," Christian Baptist, IV

(1827), 327.

35. Alexander Campbell, "Deism and

the Social System, No. IV," Christian Baptist, V (1827), 364.

36. Alexander Campbell, open letter to

"Mr. A.," Christian Baptist, V (1828), 433-434. Apparently

Campbell did not yet know of Owen's

challenge that had been issued in January 1828. Richardson,

Memoirs of Alexander Campbell, II, 239-240.

Cincinnati Spectacle 13

Gentlemen-I have now finished a course

of lectures in this city, the principles of which

are in direct opposition to those which

you have been taught it your duty to preach. It is

of immense importance to the world that

truth upon these momentous subjects should be

now established upon a certain and sure

foundation. You and I, and all our fellow-men,

are deeply interested that there should

be no further delay. With this view, without one

hostile or unpleasant feeling on my

part, I propose a friendly public discussion, the most

open that the city of New Orleans will

afford, or if you prefer it, a more private meeting,

when half-a-dozen friends of each party

will be present, in addition to half-a-dozen gentle-

men whom you may associate with you in

the discussion. The time and place to be of your

appointment.

I propose to prove, as I have already attempted

to do in my lectures, that all the reli-

gions of the world have been founded on

the ignorance of mankind; that they are directly

opposed to the never changing laws of

our nature; that they have been and are the real

sources of vice, disunion and misery of

every description; that they are now the only real

bar to the formation of a society of

virtue, of intelligence, of charity in its most extended

sense, and of sincerity and kindness

among the whole human family; and that they can be

no longer maintained except through the

ignorance of the mass of the people, and the tyr-

anny of the few over that mass.

Owen concluded the challenge with a

postscript that if his proposition were declined,

he would then regard these as unanswered

truths.37

The reformer found it necessary in the

next few weeks to repeat his challenge

and to extend it to clergymen outside of

New Orleans. As he departed from the city

on a steamboat, he soliloquized that he

had discussed religion with the highest

dignitaries of the English and Irish

churches, with leaders of dissenting churches

and with a prominent Jew in London, so

he had expected the New Orleans clergy

to be willing to investigate the truth

"for the good the knowledge of it would do

mankind. They thought differently and

did not accept my proposal."38 What reasons

the New Orleans clergy had for ignoring

Owen are unknown, but his challenge

continued to arouse public interest.

The question may be fairly asked why

Owen was so set on a debate. He wrote

later to the London Times that

the object of the meeting was not to discuss the

truth or falsehood of the Christian

religion but to determine the errors in all reli-

gions and to select from each the kernel

of truth so as "to form from them collec-

tively a religion wholly true and

consistent, that it may become universal, and be

acted upon conscientiously by all."39

The editor of the Cincinnati Chronicle and

Literary Gazette explained Owen's challenge from the fact that his

social system

was falling into disrepute, and those

who had once been enchanted by his theories

were disgusted with their practical

application. Since New Harmony was becoming

"a living memorial of the

egregious folly of his Utopian schemes," the editor

thought Owen wanted the debate to

sustain his reputation as a reformer "and

gratify his ambition for

notoriety."40 Owen would hold other debates, but he was

no debater: "He was far too intent

on stating his own case, at inordinate length,

to pay any attention to his

opponents." Moreover, he regarded a public disputation

37. New Harmony Gazette, March

26, 1828, p.169.

38. Ibid., April 9, 1828, p.186.

39. Cincinnati Chronicle and Literary

Gazette, February 14, 1829.

40. Ibid., April 25, 1829.

|

|

|

as a means of providing a platform from which he could repeat his unvarying version of the truth!41 Be that as it may, Owen's attention was soon drawn to Campbell's invitation of April 1828. Owen's acceptance was published in the New Harmony Gazette in mid- May; and in early July, on his return to England, Owen spent a night in Campbell's home in Bethany. Later in a letter to his son, Robert Dale, from Wheeling on July 13, Owen said that he and Campbell had agreed on Cincinnati as the place, and the time to be the second Monday in April 1829.42 In selecting Cincinnati as the site, both disputants acknowledged the importance of this growing Ohio River city, now so familiarly known as the "Queen City of the West." Next to New Orleans, Cincinnati was the chief city of the western country. In three years its population had jumped from 16,000 to almost 25,000. Four hundred ninety-six houses were erected there in 1828, and the newspapers boasted of the "extraordinary prosperity" of the city and that "peace, plenty and 41. Cole, Life of Robert Owen, 299. 42. New Harmony Gazette, August 6, 1828, p.326; Alexander Campbell, "A Debate on the Evi- dences of Christianity," Christian Baptist, VI (1828), 470. |

|

|

|

prosperity have pervaded all classes of our inhabitants."43 Cincinnati had twelve newspapers and periodicals, thirty-four charitable organizations, twenty-three churches, twenty-eight religious societies, forty schools, two colleges and a medical school. Its theater was considered the finest outside of New York and Philadel- phia, and presented some of the nation's greatest stars. Many of its citizens were descendants of prominent New England families, among whom was Timothy Flint who described Cincinnati as 'a picture of beauty, wealth, progress and fresh ad- vance, as few landscapes in any country can surpass.'44 The delay until the next spring for the discussion was ostensibly to allow Owen time to return to England and look after business. In reality a plan for a new communitarian colony in Mexico was unfolding in the reformer's mind. In October 1828, Owen published in England, a Memorial of Robert Owen to the Mexican Republic, and to the Government of the State of Coahuila and Texas in which he requested from the Mexican Government a grant of land in Texas to be colonized 43. Chronicle and Literary Gazette, February 14, 1829. 44. Quoted in Russell A. Griffin, "Mrs. Trollope and the Queen City," Mississippi Valley Historical Review, XXXVII (September 1950), 294. |

16

OHIO HISTORY

with Owenite communities. Despite the

fact the Mexican minister in London

informed Owen that his plan was

fantastic, the reformer sailed for Mexico City in

November, carrying letters from

important men in England to the Mexican Govern-

ment. After spending only two short

weeks in the capitol, Owen departed; and

"the entire [Mexican] project

quietly vanished into the air."45

When Campbell left for Cincinnati on

April 7, he was satisfied that he had made

thorough preparation for the coming

encounter. For months he had involved

himself in the "skeptical

system" as he tried to imagine what it would be like to

be a doubter. More than ever he was

convinced that not one good reason could

be offered against the Christian faith,

and that sectarianism was the greatest

enemy of the Christian faith in the

world. He was resolved that he would not try to

defend what the creeds said, for

"it is the religion of the Bible, and that alone, I

am concerned to prove to be

divine." He departed with the satisfaction that he had

the prayers and good wishes "of

myriads of christians in all denominations."46

Both men were in the Queen City by

Friday anxiously awaiting Monday's open-

ing session.

More than a thousand people, some from

two and three hundred miles distant,

came to the Methodist Church on Sycamore

Street that bright spring morning.

"All ages, sexes and conditions

were there," said Flint. The chapel was equally

divided with one side for the ladies and

the other for the men with a separate

door of entrance for each. The city's

leading citizens were there. A seven-man

board of moderators, headed by Judge

Jacob Burnet, Senator-elect from Ohio, sat

on an elevated platform. Alexander

Campbell brought with him his father, Thomas,

and two younger brothers, while Owen was

attended only by a young German

friend. The contestants sat side by side

waiting for the debate to begin.47

Owen, dressed in a fine suit of black

broadcloth, with manuscript in hand,

spoke slowly and deliberately in chaste

English.48 Mrs. Trollope noted that his voice

was soft and gentle with nothing harsh

in his expressions. As a matter of fact,

"his whole manner, disarmed zeal,

and produced a degree of tolerance that those

who did not hear him would hardly

believe possible."49 After asserting that the

whole history of Christianity was a

fraud, Owen entrenched himself behind his

famous "Twelve Laws," each of

which merely described one or another aspect of

the vast power of circumstances as

determinants of all human development. For

the remainder of the debate, Owen

refused to do more than repeat them. This

happened so often that Flint surmised

that the reformer's sole purpose in the

debate was to fly his reputation like

"a kite, to take up his social system into the

full view of the community, and by

constant repetition to imprint a few of his

leading axioms on the memory of the

multitude."50 At one point, Owen reiterated

45. Bestor, Backwoods Utopias, 216-217.

46. Alexander Campbell, "Desultory

Remarks," Christian Baptist, VI (1829), 552.

47. Flint, "Dispute Between Owen

and Campbell," 640-641.

48. Nathan J. Mitchell, Reminiscences

and Incidents in the Life and Travels of a Pioneer Preacher

(Cincinnati, 1877), 65.

49. For a general discussion of the

debate see Trollope, Domestic Manners, 147-153; The Evidences

of Christianity, A Debate Between

Robert Owen, of New Lanark, Scotland and Alexander Campbell,

President of Bethany College, Va.

Containing an Examination of the "Social System," (Nashville, Tenn.,

1912); for Owen's remarks, see Robert

Owen, Robert Owen's Opening Speech and His Reply to the

Rev. Alex. Campbell in the Recent

Public Discussion in Cincinnati to Prove That the Principles of all

Religions are Erroneous, and

Injurious to the Human Race (Cincinnati,

1829). (This is a rare volume,

but there is a copy in the Covington

Collection of Miami University's Alumni Library.)

50. Flint, "Dispute Between Owen

and Campbell," 642.

Cincinnati Spectacle

17

his contention that the particles of the

body were eternal, without beginning and

end, and that his body, when decomposed,

would later reappear in "new forms of

life and enjoyment." On hearing

this statement, says Flint, a revulsion of horror

swept over the audience, and he felt the

"coals of eloquence burning in his bosom"

so strongly that he himself wanted to

answer.51

Campbell's perfect self-possession left

no doubt that he was in thorough com-

mand. Now, slightly over forty with the

first sprinkling of white in his hair and

possessing a finely arched forehead and

a sparkling bright and cheerful countenance,

the clergyman "wore an aspect, as

one who had words both ready and inexhaust-

ible." So sure was he of his ground

that he left the impression "that he would not

retreat an inch in the way of

concession, to escape the crack and pudder of a

dissolving world." Campbell tried,

with withering satire, to shake the perfect com-

posure of his antagonist. Undaunted,

however, Owen retorted, making the audience

roar with laughter, and the debate moved

along in good humor.52

Campbell's thorough acquaintance with

sixteenth and seventeenth century Chris-

tian Apologists provided him with the

opportunity to fortify his audience's faith

in the Christian religion. Late in the

evening of the eighth day of debate, Camp-

bell asked the audience to be seated.

Then, in a moment of drama, he asked all

who prize the Christian religion to

please rise. "Instantly, as by one electric move-

ment, almost every person in the

assembly sprang erect." When he asked those who

were "friendly to Mr. Owen's

system" to rise, only three or four admitted to "this

unenviable notoriety." For a moment

there followed a pause and then "a loud and

instant clapping and stamping raised a

suffocating dust to the roof of the church."

The victory for Campbell seemed apparent

to most of the audience for few were

convinced that Owen's Twelve Laws had

disproved the Christian religion. While the

viewers were disappointed that the two

men had not come to close grips on the

question of the validity of

Christianity, they departed in admiration of Campbell's

superb powers. "Mr. Campbell left

on the far greater portion of the audience,"

wrote Flint, "an impression of him,

of his talents and powers, and his victory over

his antagonist, almost as favorable, as

he could have desired."53 In the long run the

editor of the Cincinnati Chronicle was

probably right when he observed that if

Owen had anticipated that his challenge

would have been accepted by one as cap-

able as Alexander Campbell, he would not

have issued it; and on the other hand,

if Campbell had known all Owen had in

mind, he might not have accepted it.54

While the debate was not cataclysmic, it

came at a time when religion was

reasserting its dominion over men's

minds following the period of inactivity after

the close of the Revolution. On the

American frontier a spirit of inquiry was in the

air and a vigorous individuality

concomitant with the dawn of the Jacksonian era

drove men to seek for solutions to their

doubts. The Calvinism that ruled so sedately

in Colonial America was now being put to

rest and the frontier was seeking for new

grounds of faith somewhere between

atheism and dogmatic sectarianism. The crowds

that came for miles to hear the debate

were driven by numerous complex impulses,

not the least of which was the search

for new religious foundations in an age of

dynamic transitions.

51. Ibid., 643-644.

52. Ibid., 641, 644.

53. Ibid., 646-647.

54. Chronicle and Literary Gazette, April

25, 1829.