Ohio History Journal

FRANK L. KLEMENT

Ohio and the Dedication of the

Soldiers' Cemetery at Gettysburg

Ohioans had more than a passing interest

in the dedication of the Soldiers' Ceme-

tery at Gettysburg on November 19, 1863.

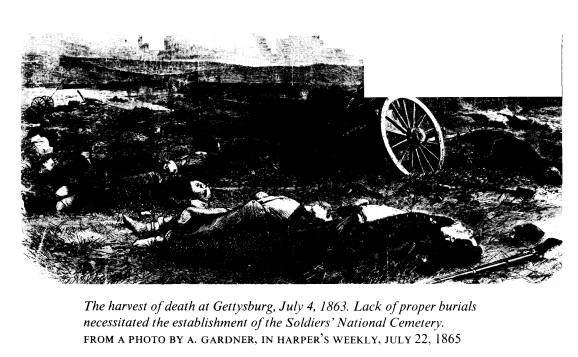

A decisive three-day battle, fought in

the surrounding countryside on July 1-3,

1863, had claimed the lives of many of

the state's soldiers, some of whom were

hurriedly buried in shallow graves or

merely covered with spadefuls of dirt

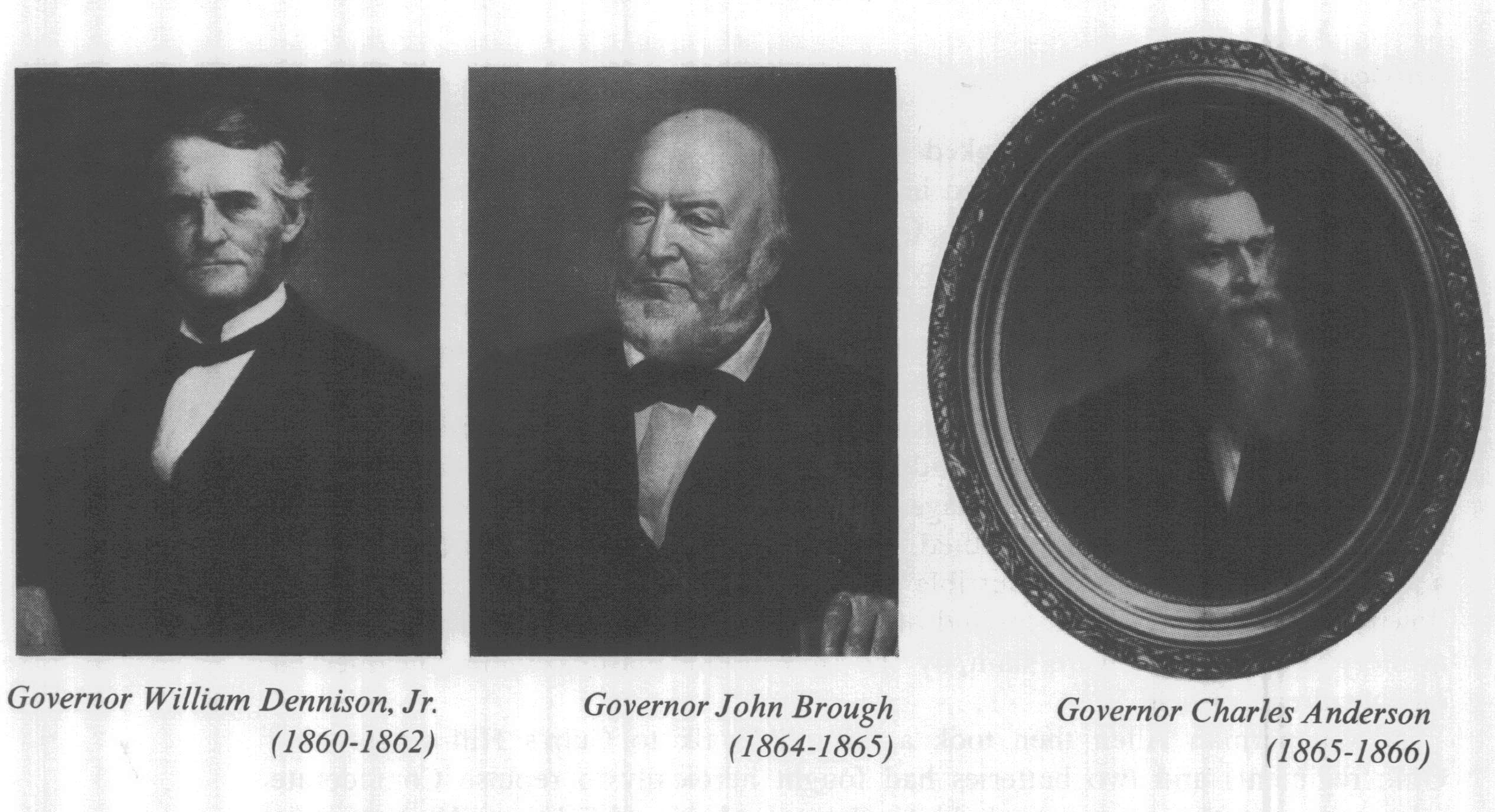

where they had fallen. No other governor,

not even Pennsylvania's Andrew Curtin,

did as much as Ohio's David Tod to

encourage officials and citizens of his

state to journey to Gettysburg to witness

the dedication ceremonies. No other

state had an ex-governor, a governor, and a

governor-elect present on the central

platform during the program. In fact, Ohio

had more citizens seated on the platform

than any other state. No other state,

not even Pennsylvania, had as many

newspapermen in attendance, one of whom

wrote far and away the most detailed

eyewitness account of the day's proceedings.

One of the three major generals who

marched in the procession and had a seat

of honor on the platform was an Ohioan.

Furthermore, the man who gave the

second formal oration of the day,

drawing more applause and presenting a more

appropriate message than the first

speaker, Edward Everett, claimed Ohio as his

home.

The story behind the dedication of the

Soldiers' Cemetery goes back to late

June 1863 when General Lee's forces,

with morale high and with Confederate

flags and regimental banners waving in

the summer breeze, crossed the Potomac

and moved up into Pennsylvania. Since

Ohio adjoins Pennsylvania, Lee's invasion

of that state gave rise to much

speculation and many rumors. Ohioans read the

telegraphic accounts of the invasion and

fighting at Gettysburg with interest and

apprehension during the first week of

July 1863. Pro-Lincoln groups feared that a

notable Confederate victory might

adversely affect the fall gubernatorial contest

in which the Unionist party candidate,

John Brough, opposed Clement L. Vallan-

digham, the Peace Democratic nominee

then in exile in Canada. Furthermore,

many Ohio soldiers belonged to the Army

of the Potomac and each military

encounter generated anxiety back home.

After the battle was over and Robert E.

Lee led his defeated army back across

the Potomac, Ohioans pieced together the

events of the bloody three days. They

learned that their soldiers had

performed heroically in various parts of the vast

battlefield. Five infantry regiments and

two of the four artillery batteries suffered

heavily during the first day's action

when the Confederates overpowered the

Eleventh Corps on the plain

north of Gettysburg. Three regiments and three

Mr. Klement is professor of history at

Marquette University, Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

|

|

|

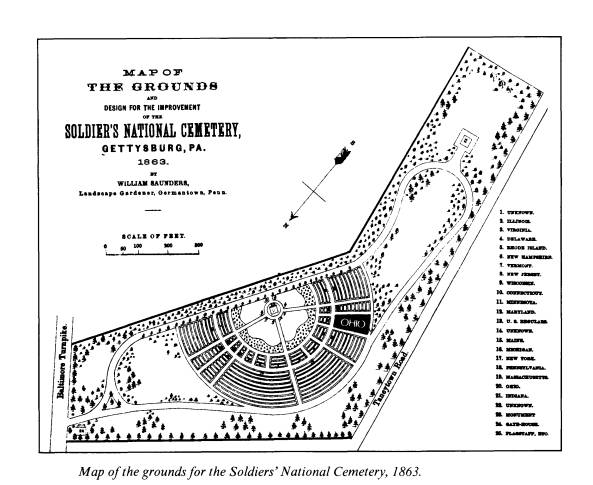

batteries, reinforced by six other Ohio units played a decisive part in the fierce hand-to-hand fighting for Culp's Hill late on the second day, completely destroying the famous Louisiana "Tigers" in General Harry Hays's brigade. On the third day Ohio soldiers and batteries defended the Union flanks from positions on Cemetery Hill and on Little Round Top during Pickett's gallant but futile assault against the center of General Meade's defenses built along Cemetery Ridge. Ohio units numbering 4327 men counted their losses: 171 killed, 754 wounded, and 346 missing, totaling 1271 casualties, or nearly one in three engaged.1 Many Ohioans, informed of the death of a son, brother, or husband, journeyed to Gettysburg to claim the bodies and brought them home to be buried in local cemeteries.2 Others only knew that their loved ones were among the missing or 1. The following Ohio organizations, totaling 4327 men, took part in the three-day Battle of Gettysburg: Companies A and C of the First Ohio Cavalry; ten companies of the Sixth Ohio Cavalry; Batteries H, I, K, and L of the First Ohio Light Artillery; and the Fourth, Fifth, Seventh, Eighth, Twenty-Fifth, Twenty-Ninth, Fifty-Fifth, Sixty-First, Sixty-Sixth, Seventy-Third, Seventy-Fifth, Eighty- Second, and One Hundred Seventh Infantry regiments. Only three states, New York, Pennsylvania, and Massachusetts, had more troops at Gettysburg than Ohio. The total number of Federal troops engaged was 88,289, with 23,049 casualties--a ratio considerably lower than Ohio's. Report of the Gettysburg Memorial Commission (Columbus, 1887), 63-68; Mark Mayo Boatner, III, Civil War Dictionary (New York, 1959), 339. |

Gettysburg Soldiers' Cemetery

79

were not even informed that they were

lying somewhere on the baneful battlefield.

Some of the dead soldiers were buried

hurriedly or carelessly and, in some cases,

only shovelfuls of earth were tossed

over the lifeless bodies by weary survivors.

Heavy rains washed off some of the soil

which had covered the dead, exposing

portions of arms or legs, and a

sickening stench hovered over the areas where the

first day's fighting had been heaviest.

While Ohio residents were reclaiming

their dead and mourning the loss of

loved ones, David Wills, a community

leader in Gettysburg, took the initiative

in urging the governor of Pennsylvania

to purchase a portion of the battlefield,

"the ground on which the centre of

our line of battle rested July 2 and 3rd," for

a cemetery and to rebury the patriotic

soldiers who had fallen there. He stated

that hogs were desecrating some of the

graves and that "propriety and humanity"

dictated that Pennsylvania should

"take measures" to remedy the situation. Wills

added that he was sure "other

States which had lost sons at Gettysburg" would

be willing to share the expenses in

establishing a national cooperative cemetery

to be administered by "the States

interested."3

Governor Andrew G. Curtin, in turn,

authorized Wills to buy whatever acreage

he deemed necessary and to pursue the

idea of a cooperative cemetery further,

giving assurance of his own endorsement

as well as that of the Pennsylvania

legislature. Wills then sent a telegram

on August 1, 1863, to each of the seventeen

governors whose states had furnished the

various Union forces which had fought

with those from Pennsylvania on the

battlefield of Gettysburg. His three-sentence

telegram to Governor David Tod read:

By authority of Gov. Curtin, I am buying

ground on or near Cemetery Hill, in trust for

a cemetery for the burial of the

soldiers who fell here in defense of the Union.

Will Ohio co-operate in the project for

the removal of her dead from the field? Signify

your assent to Gov. Curtin or myself,

and details will be arranged afterwards.4

Governor Tod did not reply to Wills's

telegram and follow-up letters on the

question of Ohio's participation in the

cemetery venture until August 23. He

wanted to consult with members of his

party's hierarchy:

Your letter of the 12th instant, giving

plans, &c., for the place of rest of the gallant dead

who fell in the battle of Gettysburg, is

before me.

Heartily approving, as I do, of the

project, I can only now promise that I will commend

the same to the coming General Assembly.5

After state representatives from

Wisconsin and Connecticut had assured David

Wills that his project was a worthy one,

he purchased twelve acres atop Cemetery

Hill, secured the assistance of a

landscape gardener to design the burial grounds,

2. Daniel Brown to Tod, October 28,

1863, David Tod Papers, Ohio Historical Society. The letter

is printed in full in the Ohio State

Journal, November 2, 1863.

3. David Wills to Gov. Andrew Curtin,

July 24, 1863, in "Curtin Letterbooks," Executive Corre-

spondence, 1861-1865, Pennsylvania State

Archives, Harrisburg; "Report of David Wills," Revised

Report made to the Legislature of

Pennsylvania, Relative to the Soldiers' National Cemetery, at Gettys-

burg . . . (Harrisburg, 1867), 5-6. David Willis was a lawyer,

superintendent of schools, and the town's

leading Republican at age 32.

4. Telegram, David Wills to David Tod,

August 1, 1863. Documents Accompanying the Governor's

Message of January, 1864 (Columbus, 1864), 158.

5. Tod to Wills, August 23, 1863, ibid.,

160.

80

OHIO HISTORY

and composed some guidelines for the

cooperative cemetery, including them in a

circular letter he sent to each

governor. Wills's carefully drafted circular letter on

August 12 stated that he had purchased

"about twelve acres" of the battlefield

"to be devoted in perpetuity"

for a soldiers' cemetery, that the dead would be

buried in sections assigned to each

state, that "the grounds to be tastefully laid

out, and adorned with trees and

shrubbery," and that the "whole expense," not

to exceed $35,000, would be apportioned

among the cooperating states--each

"to be assessed according to its

population, as indicated by its number of repre-

sentatives in Congress." The letter

closed with the request that each governor

appoint "an agent" who would

assist in the carrying out of the reburial project.

Wills also sent a short personal note to

Governor Tod along with the printed

circular letter. He said, if Ohio

desired "a conveyance, in fee simple," for her

share of the "burial ground in this

cemetery," Pennsylvania would make a deed

for it--otherwise she "will hold

the title in trust for the purposes designated in

the circular." "It is

desirable," Wills noted, "to have as little delay as possible

in getting your reply, as the bodies of

our soldiers are, in many cases, so much

exposed as to require prompt attention,

and the ground should be speedily arranged

for their reception."6

The Ohio governor, however, was dilatory

in naming the state's agent expected

to go to Gettysburg to work with Wills

and other agents on the cemetery project.

Waiting until October 25, Tod finally

named Daniel W. Brown, a Republican

judge who had once served as warden of

the State Penitentiary, as the Ohio agent

and instructed him to remain in

Gettysburg as his representative until November

19, the day of the dedication

ceremonies.7

Wills, meanwhile, had taken other steps

to carry out the project. He purchased

several adjoining plots of ground to

bring the cemetery area to seventeen acres.

He worked with William Saunders, who was

a landscape gardener in the Depart-

ment of Agriculture and was from

Germantown, Pennsylvania, "to lay out the

ground in State lots, apportioned in

size according to the number of marked graves

each state had on this battle

field." He also invited bids for "disinterring, removing

and burying in the National Cemetery,

all the Union dead on the battle field."

Thirty-four bids were received, ranging

from the low of $1.59 to $8.00 per body;

the contract was awarded to Frederick W.

Biesecker, the lowest bidder. Wills, in

turn, hired Samuel Weaver to superintend

the exhuming of the bodies of Union

soldiers. His duties included

identifying the bodies in all the graves opened by

Biesecker's crew and keeping careful

record of all items found therein, and then

seeing that the bodies were carefully

placed in a coffin and reburied. In cases

where Confederate bodies were uncovered,

they were reburied where they were

found.8

6. Circular letter, signed by David

Wills as agent for Governor Andrew Curtin, dated August 12,

1863, ibid., 158-159; Willis to

Tod, August 12, 1863, ibid.

7. Tod to Brown, October 25, 1863, ibid.,

160.

8. In all Wills purchased five different

lots: two at $225 per acre, one at $200, one for $150, and

one for $135. The five lots, totaling

seventeen acres, cost $2,475.87. "Report of David Wills," 5-9.

Samuel Weaver reported that he made a

list of all items found with the bodies, putting them in

a vault before reinterring the bodies.

In his "List of Articles," Weaver recorded the following on four

of the thirteen Ohio soldiers examined:

"Lewis Davis, Company D, 75th Ohio Infantry Regiment,

Testament and letters; Asa O. Davis,

Company G, 4th Regiment, gun wrench, comb and ring; Thomas

Doman, Company K, 25th Regiment, $4 and

gold locket; and Serg. John Pierce, Company C, 25th

Regiment, pipe." "Report of

Samuel Weaver," Revised Report made to the Legislature of Pennsylvania,

Relative to the Soldiers' National

Cemetery, at Gettysburg . . . (Harrisburg,

1867), 161-164, 148.

Gettysburg Soldiers' Cemetery

81

By mid-August Wills again wrote to

Governor Curtin, outlining the progress

being made and suggesting that the

grounds be "consecrated by appropriate cere-

monies." The Pennsylvania governor

agreed with Wills's suggestion. "The proper

consecration of the grounds must claim

our early attention," Curtin replied, "and,

as soon as we can do so, our

fellow-purchasers should be invited to join with us

in the performance of suitable

ceremonies on the occasion." He then instructed

Wills to set the date for the event and

to plan the day's program.

Wills first set October 22 as the day

for the dedication of the burial grounds

as "sacred soil," and wrote to

all the governors asking them to attend the cere-

monies and help consecrate the grounds.

He also invited the Honorable Edward

Everett, the scholar-statesman who

recently had changed from condoning seces-

sion to all-out support of the Union

cause, to be the orator for the occasion.

Everett accepted the honor but begged

for a later date-his commitments would

prevent him from being ready before

November 19. Since Wills had his heart

set on getting Everett, he had to change

the dedication date from October 22 to

November 19.

The change in dates necessitated another

round of letters to the governors,

Wills's letter to Tod being dated

October 13. The Ohio governor, dilatory once

more, delaying his answer for twelve

days, promised that he and "a large number

of our State officials" would be in

Gettysburg for the dedication ceremonies. He

also informed Wills that Daniel W. Brown

had been named as the state agent

"to look especially after the

removal of the dead of our State . . . . He is a worthy

gentleman, and I beg you to receive and

treat him kindly."9

Tod's agent, with a letter of

introduction and a draft for $100 in his pocket,

left for Gettysburg on October 26. After

a three-hour delay in Harrisburg and

four at Hanover Junction, agent Brown

arrived in Gettysburg. He walked directly

to Wills's house, but the busy promoter

had gone to a flag raising on Round Top,

about three miles south of the small

town. Brown decided to walk over to witness

the ceremonies. When he introduced

himself to Wills, he received "a kind recep-

tion" and was then conducted on a

tour of Cemetery Ridge before returning to

Gettysburg. In the evening Wills held an

informal reception for Brown and three

other state agents, briefing them on

action already taken and explaining plans for

the cemetery and its dedication. All of

those already buried in the new cemetery

were the unknowns killed north and west

of town in the first day's fighting. These

were not identifiable because they had

lain out in the hot sun until the rebels

retreated, so they could not be

recognized and their shallow graves were unmarked.10

The next morning agent Brown accompanied

David Wills on a tour of the

fields where the rival armies had

clashed in the first day's fighting. They visited

the spot where Major General John F.

Reynolds, General Meade's most trusted

subordinate, had fallen and other points

of interest, presumably the battle-scarred

woods around McPherson's Ridge, the

railroad cut, and the Middleton Road north

of town where several Ohio regiments had

suffered heavy losses. They also visited

the new cemetery grounds to

witness "the work going on there." In the afternoon

9. Wills to Curtin, August 17, 1863;

Curtin to Wills, August 31, 1863; Wills to Edward Everett,

September 23, 1863; Everett to Wills,

September 26, 1863, ibid, 181-184; Wills's letter to Tod, Septem-

ber 15, 1863, is noted in the letter of

Tod to Wills, September 18, 1863; Tod to Wills, October 25,

1863, Documents Accompanying the

Governor's Message, 160, 161.

10. Tod to Daniel Brown, October 25,

1863, ibid., 160; Brown to Tod, October 28, 1863, David

Tod Papers. The other three agents were

John F. Seymour (brother of Governor Horatio Seymour) of

New York, Colonel W. George Geary of

Vermont, and Levi Scobey of New Jersey.

82

OHIO HISTORY

Brown went to the "Hospital"

to attend the funeral services for Enoch M. Detty,

Company G, Seventy-Third Ohio Volunteer

Infantry Regiment--the first known

Union soldier reburied in the new

cemetery. The funeral was conducted with mili-

tary honors, and the ceremonies,

symbolism, and scenery deeply impressed the

Ohio agent. In reporting to his

governor, Brown described the cemetery site as

"one of the most beautiful as well

as most appropriate places that could have

been selected."11

Governor David Tod, meanwhile, composed

a circular letter inviting "the officers

of the State," which in terms of

the invitation included state officials, members

and members-elect of the state

legislature, several newspaper editors, and a handful

of military officials, to join him in

witnessing the dedication of the Soldiers' Ceme-

tery in Gettysburg on November 19. He

wrote that the state would pick up the

tab for the excursion to Gettysburg.

"Upon being advised of your willingness and

ability to participate in the

ceremonies," the closing sentence of the letter read,

"I will send you transportation at

the expense of the State."12

The favorable response to Tod's

invitation was overwhelming. About one hun-

dred thirty wrote letters of acceptance,

even though not that many actually attended.

The list included such notables as

Governor-elect John Brough, Colonel Edward

A. Parrott, State Treasurer G. Volney

Dorsey, and many others. It also included

a surprising number of state

legislators--nearly all Republicans.13

Two groups sent regrets. The first

included those Ohio notables, like Major

General William S. Rosecrans and United

States Senator John Sherman who had

already accepted an invitation to attend

the opening of the Cleveland-Meadville

(Pennsylvania) branch of the Atlantic

and Great Western Railroad. This rival

event of November 18 featured a free

ride from Cleveland to Meadville, "a

splendid lunch" there, the return

trip to Cleveland, "a magnificent supper" at the

Angier House, and an evening of

entertainment and oratory.14

The second set of regrets came from

Democrats, some of whom tried to make

political capital out of Governor Tod's

promise to provide free transportation to

Gettysburg. George L. Converse,

Democratic spokesman in the lower house of

the state legislature the previous

session, wrote a scurrilous letter declining Tod's

invitation and circulated it in his

party's newspapers. Converse said he did not

want to accept any favor from a bitter

political opponent who had been guilty of

spreading "falsehoods and misrepresentations of me personally" during

the recent

11. Ibid.

12. Circular letter, dated October 25,

1863, signed by Governor Tod, Documents Accompanying

the Governor's Message, 160.

13. "Names of Persons Accepting

Governor's Invitation to Visit Gettysburg," dated November 19,

1863, in David Tod Papers. The list also

included such notables as S. G. Harbaugh (Librarian, State

Library), Hon. Levi Sargent (Board of

Public Works), Earl Bill (U. S. Marshal), Oviath Cole (State

Auditor), John H. Klippart

(Corresponding Secretary, State Board of Agriculture), and David Taylor

(Treasurer, State Board of Agriculture).

Ex-Governor William Dennison attended the ceremonies, but

apparently not at state expense. Most of

the newspapermen who accepted the free ride were Republi-

cans. They included Martin D. Potter,

Cincinnati Commercial; L. A. Hine, Cincinnati Gazette; W. B.

Thrall, Columbus Express; Isaac

Jackson Allen, Ohio State Journal (Columbus); John G. Shryock,

Zanesville Courier; William D.

Bickham, Dayton Journal; and George A. Benedict, Cleveland Herald.

However, John S. Stephenson, editor of

the Democratic Cleveland Plain Dealer, also accepted.

14. Cleveland Herald, November

19, 1863; Columbus Daily Express, November 20, 1863; T. W.

Kennard to Tod, November 5, 1863, David

Tod Papers. Tod's promise to attend the Gettysburg Cere-

monies meant he had to forego the

"Cleveland Celebration." Congressman-elect James A. Garfield,

however, apparently did not attend

either event. His correspondence of the period indicates that he

as detained at home "for the saddest of

reasons"--the illness and death of his four-year-old daughter.

Corydon E. Fuller, Reminiscences of

James A. Garfield (Cincinnati, 1887), 344.

Gettysburg Soldiers' Cemetery 83

hotly contested Brough-Vallandigham

campaign. He also did not want to be "a

party to the fraud and larceny of taking

money from the Public Treasury to pay"

for his trip to Gettysburg. The incensed

Democratic critic asked a series of pointed

and insulting questions:

Will you allow me to inquire of your

Excellency why it is that this "transportation at the

expense of the State" is furnished

to men who are generally able to pay their own expenses?

Would it not be more prudent as well as

more patriotic to furnish it to the poor widows

and orphans, and childless mothers who

have been made such by the great battle in July,

that they might visit at the expense of

the State the graves of their husbands, fathers and

sons, and moisten the dry earth that

covers the gallant dead, with the copious tears of

affliction and affection that are now

falling in silence and seclusion all over the land.

Converse asked other questions too.

Could not the money, spent on an excur-

sion to Gettysburg, be better spent by

"purchasing clothing, fuel, and food for the

suffering poor who have been made such

by that great battle?" Was it proper for

Tod to "unceremoniously thrust your

[his] arm into the state treasury?" or "Was

this a raid upon the treasury for the

benefit of the Rail Roads?"15

Nearly every Democratic editor in Ohio

published Converse's critique, some

with and some without editorial comment.

It appeared first in the Crisis in Colum-

bus on November 4, 1863, along with

editor Samuel Medary's comment to the

effect that "it is gratifying to

know that there is one man left bold enough to cry

out against a system of the wildest

extravagance which ever cursed any people."

The editor of the Hillsboro Weekly

Gazette added his own carping criticisms to

those of Converse:

We would like to know where Tod the

thief got his authority to issue "transportation" to

the amount of $15,000 to transport

"officials" to Gettysburg! He addressed communications

to Democrats offering to pay their

expenses if they wo'd condescend to honor the brave

dead at Gettysburg, by being present at

the dedication of the Soldiers' Cemetery. Several

refused, we notice, to have any

complicity in the high-handed robbery of the Treasury.

That's right. If any Democrat accepted

Tod's pilfering "transportation," we are in favor

of reading them out of the party.16

George W. Manypenny of the

Democratic-oriented Ohio Statesman (Columbus)

asked questions like Converse's:

"The tax-payers will have to foot the bills; but

what care these gentlemen [Tod &

Company] for that? Does the State also pay

for the Champaign [sic] and other

luxuries that accompanied the 'expedition'?"

James J. Faran of the Cincinnati Enquirer

told his readers that Tod was guilty of

violating the state constitution, citing

the section which read: 'No money shall be

drawn from the treasury, except in

pursuance of a specific appropriation made

by law.' Archibald McGregor of the Stark

County Democrat (Canton) published

Converse's letter in the same issue in

which he featured an editorial comparing

the "reign" of Lincoln to that

of Oliver Cromwell and criticizing both for their

use of force in an effort to gain the

"allegiance" of conquered peoples. Some other

Democratic state officials also felt the

same as Converse and declined Tod's invi-

tation "to accept a gratuitous

passage at the expense of the State."17

15. George L. Converse to Tod, October

31, 1863, David Tod Papers.

16. Crisis (Columbus), November

4, 1863; Hillsboro Weekly Gazette, November 26, 1863.

|

Many Unionists, on the other hand, assured Tod that posterity would express its thanks and rewards for his efforts to honor the fallen soldiers. "If the living do not," wrote one, "the dead will bless you, for your affectionate care of Ohio soldiers." Isaac Jackson Allen of the Ohio State Journal (Columbus) said in his letter of acceptance to Tod's invitation: "Permit me to add that posterity will surely award both praise and blessings to the men, who, with yourself, have been instru- mental in securing this solemn, appropriate, and honorable testimonial of an admiring Nation's gratitude to that 'noble Army of Martyrs' who fell at Gettysburg! --Geo. Convers' [sic] infinitessimal [sic] soul to the contrary notwithstanding!"18 While the partisan controversy over the use of state funds for "Tod's excur- sion" continued, the reburial of the dead from shallow battlefield graves to the semi-circular landscaped cemetery went on at a steady pace. Daniel W. Brown, Tod's agent in Gettysburg, however, expressed his concern about the many Ohio soldiers whose remains were being exhumed and shipped back to Ohio. "Hun- dreds [of bodies]," Brown wrote late in October, "have been removed and friends are here constantly removing." He believed that most of these bodies being shipped back would have been left at Gettysburg to be reburied into the new soldiers' cemetery if only their friends and relatives had known of "the arrangements" being carried out. "The time for removing has about passed by," the solicitous agent added, "and those who may come here for friends who are marked [in marked graves], may find them already deposited in the cemetery, after which it will be very difficult to remove them without disarranging the whole plan."19 Samuel Weaver, the superintendent of the reburial work, sought to remove many bodies before the fall weather gave way to winter's cold, for spades and 17. Daily Ohio Statesman (Columbus), November 20, 1863; Cincinnati Daily Enquirer, November 9, 1863; Stark County Democrat (Canton), November 18, 1863; no editorial comment appeared in the Circleville Democrat, the Ohio Eagle (Lancaster), or the Holmes County Farmer (Millersburg); Hon. J. H. Putnam to Tod, November 4, 1863, Otto Dressel to Tod, November 2, 1863, and Thomas Beer to Tod, November 10, 1863, David Tod Papers. 18. George P. Sentin to Tod, November 10, 1863, Martin Welker to Tod, November 7, 1863, Samuel Galloway to Tod, November 12, 1863, and Isaac Jackson Allen to Tod, November 4, 1863, ibid. 19. Brown to Tod, October 28, 1863, ibid. |

Gettysburg Soldiers' Cemetery

85

shovels were ineffective in frozen

ground. Most of the battlefield graves were

singles, but occasionally Weaver's men

found the dead buried in trenches or shal-

low ditches, in which the decaying

corpses laid side by side--in several instances

the numbers in a single trench

"amounted to sixty or seventy bodies." Weaver

explained why some bodies were in an

advanced stage of decomposition: "On

the battle field of the first day, the

rebels obtained possession before our men

were buried, and left most of them

unburied from Wednesday [July 1] until

Monday [July 6], following when our men

buried them. After this length of time

. . . heat, air, and rains causing rapid

decomposition of the body, they could not

be identified."20

When it became apparent that many of the

state's notables and citizens would

attend the dedication ceremonies at

Gettysburg, Governor Tod decided to arrange

for a special Ohio program to be held in

the late afternoon so that these gentle-

men could "hear an address from one

of their own number." After consulting

with his friends, Tod invited Colonel

Charles Anderson to give the oration. Ander-

son was an excellent choice--he was

lieutenant governor-elect and had an out-

standing reputation as a public speaker.

Both his speeches and pamphlets had

proved him "a good Union man."

Since he had supported the Bell-Everett ticket

in 1860, he was regarded as less a

partisan than most Unionists-the term used

for Republicans in Ohio during the Civil

War. Furthermore, he had won praise

for his bravery at Chickamauga, where he

had been wounded. He was the brother

of Major Robert Anderson, whose name had

become a household word after the

Fort Sumter attack of April 1861.

Colonel Anderson accepted Tod's invitation,

promising to do his best, and

immediately set to work writing and memorizing

an appropriate oration.21

Governor Tod, seeking to assure an

excellent turnout for the dedication cere-

monies and for the Ohio program,

instructed the state's agent in Washington,

D. C., to seek furloughs for Ohio

troops in the area so that they might attend the

Gettysburg affair on November 19.22

David Wills, meanwhile, expressed

satisfaction with the progress of reburying

soldiers and the transformation of a

portion of the battlefield into a cemetery and

with the cooperation he had received

from the governors. President Lincoln had

also helped by sending his bodyguard,

Ward H. Lamon, to Gettysburg to give

Wills whatever help he needed. In turn,

Wills named Lamon the marshal for the

dedication ceremonies. Wills and Lamon,

discussing the organization of the pro-

cession and the program of November 19,

decided to ask each of the cooperating

states to name "two suitable

persons" to help organize the procession and to

supervise the day's affairs.23 They

also exchanged views about musical organiza-

tions and names of those who might be

invited to give the benediction and

invocation.

Wills, consequently, wrote to several

musical organizations, inviting each to

take part. He asked the Reverend Thomas

H. Stockton, chaplain of the House of

Representatives, to give the invocation

and the Reverend Henry L. Baugher,

20. "Report of Samuel Weaver,"

162-163.

21. Tod to Charles Anderson, October 27,

1863, Documents Accompanying the Governor's Message,

161-162; Anderson to Tod, November 5,

1863, David Tod Papers.

22. Tod to Brown, November 6, 1863, Documents

Accompanying the Governor's Message, 161.

23. Ward H. Lamon, an old friend from

Lincoln's Springfield days and once a law partner, held

a patronage post in Washington, being

commissioned United States Marshal for the District of Colum-

bia. See form letter, Ward H.

Lamon to Tod, November 5, 1863, David Tod Papers.

86

OHIO HISTORY

president of Gettysburg Seminary, to

close the dedication program with a bene-

diction. Wills also invited President

Lincoln, Vice-President Hannibal Hamlin, all

Cabinet officials, heads of foreign

legations, and members of Congress to attend.

And after Wills received word from

Lincoln that he would attend, the promoter

had the foresight to ask the President

to "formally set apart these grounds to their

sacred use by a few appropriate

remarks."24

As the day to entrain for Gettysburg

approached, there was a flurry of activity

in Columbus and Washington. President

Lincoln, sensing the importance of the

occasion, "strongly urged" his

Cabinet members to attend "the ceremonials" at

Gettysburg. Nevertheless, the two

Ohioans in the Cabinet, Edwin M. Stanton,

Secretary of War, and Salmon P. Chase,

Secretary of the Treasury, found good

excuses to spend the day in Washington.

Both had earlier sent their regrets to

David Wills. Chase, in a letter of

November 16, asked to be excused because of

his "imperative public

duties." In reference to the fallen soldiers, he said, "It

consoles me to think what tears of

mingled grief and triumph will fall upon their

graves, and what benedictions of the

country, saved by their heroism, will make

their memories sacred among men."

The President, however, continued to twist

Chase's arm. "I expected to see you

[Chase] here at [the] Cabinet meeting," Lincoln

wrote in his note of November 17,

"and to say something about going to Gettys-

burg. There will be a train to take and

return us,"25 but Chase still ignored the

President's request. Perhaps the fact

that Secretaries William H. Seward, John P.

Usher, and Montgomery Blair had decided

to go was enough of an excuse for

Chase to stay home--all were members of

the rival faction within the Cabinet.

So another of Ohio's most illustrious

sons was not present at the ceremonies of

November 19.

And still another, Stanton, offered the

same excuses as Chase. He said that the

duties of his office were too pressing

to admit his absence from Washington, but

he did make the transportation

arrangements for the President. Stanton first

arranged for a special train to leave

Washington early on the morning of the

dedication, arriving just in time for

the ceremonies, and then for the train to

return the same evening. Lincoln did not

like this plan. A slight accident or delay

would cause him to miss the program--it

seemed "a mere breathless running of

the gauntlet."26 The

Secretary of War then scheduled the President's party to leave

Washington at noon on November 18,

arriving at Gettysburg the evening before

the ceremonies.

While Lincoln was still urging members

of his Cabinet to accompany him to

Gettysburg, Governor Tod's large

entourage boarded the cars of the "Steubenville

Short Line" (the Pittsburgh,

Columbus & Cincinnati Railroad) on the morning

of November 16 and waved good-bye as

they headed for their destination via

Steubenville, Pittsburgh, Harrisburg,

and Hanover Junction. An accident about

two miles east of Coshocton, the result

of a collision of two freight trains, delayed

Tod's train for seven hours. The

impatient travelers spent the long hours playing

euchre or spinning yarns. After clean-up

crews removed the debris from the tracks

24. Wills to Lincoln, November 2, 1863,

Robert Todd Lincoln Papers, Library of Congress.

25. Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon

Welles, Secretary of the Navy under Lincoln and Johnson, intro-

duction by John T. Morse, Jr. (Boston,

1911), I, 480; Chase to Wills, November 16, 1863, in Cincin-

nati Commercial, November 23,

1863; Lincoln to Chase, November 17, 1863, Salmon P. Chase Papers,

Grosvenor Library, Buffalo, New York.

26. Lincoln to Stanton [November 17,

1863], in Roy P. Basler, ed., Collected Works of Abraham

Lincoln (New Brunswick, N. J., 1953), VII, 16.

Gettysburg Soldiers' Cemetery 87

and effected repairs, Tod's train

resumed its journey toward Steubenville, arriving

there an hour and a half past midnight.27

The train left Steubenville for

Pittsburg at six-thirty the next morning (Novem-

ber 17). When the Ohio delegation

arrived, they found that Pennsylvania's Gov-

ernor Curtin had placed "a

beautiful and most commodious car" at their dis-

posal. At Harrisburg a large number of

Ohioans, including Governor-elect and

Mrs. Brough and Colonel Charles

Anderson, joined Tod's party. There Tod met

Governor Andrew Curtin, his host, and

boarded "the Governor's Special." Tod

also met two other governors on this

train, Oliver P. Morton of Indiana and

Horatio Seymour of New York.

Bad luck seemed to dog Tod's delegation.

About fifteen miles out of Harris-

burg the locomotive "gave out"

and the travelers lost three more hours, much to

the embarrassment of Governor Curtin.

The delay threw the train way off schedule

and the overly cautious engineers

proceeded at what seemed like a snail's pace,

more anxious to get the passengers

safely rather than speedily to Gettysburg. It

was nearly midnight when the creaky

steam engine brought its train of special

cars into the station.28

Agent Brown met the special train and

escorted the dignitaries in the Ohio

delegation to hotels or houses where he

had reserved rooms. He had arranged

for "suitable accommodations,

although the town was crowded to excess by the

throng of visitors seeking rooms and

shelter." All Ohioans were not as fortunate

as the important members of Tod's

delegation. William T. Coggeshall of the

Springfield Republic, for

example, had to try to sleep "upon boards laid upon

trussels, in the kitchen of a

'hospitable' Gettysberger."29

While directing the Tod party to

quarters reserved for them, Brown reported

on the progress of the reburials and on

his own activities as the state's agent. The

work of exhuming the bodies of the Union

soldiers and reburying them in the new

cemetery had proceeded satisfactorily,

being about one-third completed by Novem-

ber 14. Twenty-four of the 1188 interred

had been identified as Ohioans and had

been reburied in that section reserved

for the state. In addition, some of the 582

who had been buried in the section

reserved for the "unknown" had belonged

to Ohio regiments, but no one could

hazard a guess as to how many. (The total

number buried between October 27, 1863,

and March 18, 1864, was 3564; Ohio's

known dead was 131.) Brown also reported

that Ward H. Lamon, chief marshal

for the ceremonies, had held a meeting

with the assistant marshals who were

present in the courthouse to give

instructions regarding the next day's procession

and plans. Since both of Ohio's

assistant marshals, Colonel Gordon Lofland of

Cambridge and Colonel George B. Senter

of Cleveland, had been aboard Tod's

train, they had missed Lamon's briefing

session, so Brown informed them that

the governors of the states and their

staffs had been placed in the front section

of the procession directly behind the

speaker of the day and the chaplain, but

that the Ohio delegation's place was at

the end--a mile away. Brown also said

that he had arranged for the use of a

large Presbyterian church for the special

Ohio program which would follow the

cemetery dedication ceremonies.30 Then,

27. Springfield Republic, November

20, 1863; Cleveland Herald, November 20, 1863.

28. Cincinnati Commercial, November

23, 1863; Cleveland Herald, November 24, 1863.

29. "The Ohio Delegation at

Gettysburg," Documents Accompanying the Governor's Message, 162-

163; Springfield Republic, November

27, 1863.

30. Ibid.; Cincinnati Commercial,

November 23, 1863; "Report of David Wills," 8.

88

OHIO HISTORY

since it was very late and everyone was

tired, members of Tod's large delegation

sought sleep and rest, knowing that

November 19 would be a strenuous day.

During the early hours of the morning of

the 19th, successive showers of rain

fell, but by eight o'clock the skies had

brightened and the sun shone in all its

autumnal splendor. The assistant

marshals, under Lamon's supervision, made the

rounds, instructing the states'

delegations as to their places in the procession,

scheduled to leave downtown Gettysburg

at ten o'clock. Colonels Lofland and

Senter, the assistant marshals

representing Ohio, were decked out in "sashes of

white and straw-colored ribbon, caught

at the shoulders by mourning rosettes,

Union rosettes upon their breasts, and

saddle-cloths of white cambric, bordered

with black."31

The presence of so many strangers and

the steady arrival of sightseers made

the task of the assistant marshals more

difficult and delayed the departure of the

procession for the new cemetery more

than an hour. Many of these persons, coming

on foot, horseback, carriage and train,

were fathers, mothers, brothers, or wives

of the dead who had come from distant

parts to weep over the remains of their

fallen kindred and to witness the

dedication of a portion of the battlefield as holy

ground.32

While Colonels Lofland and Senter tried

to round up Ohioans and direct them

toward the street corner designated as

the state's place in the procession, thousands

of visitors wandered around various

portions of the huge battlefield. Several mem-

bers of the Ohio press corps, including

Martin D. Potter of the Cincinnati Com-

mercial and Isaac Jackson Allen of the Ohio State Journal, joined

some of the

pilgrims on the country road leading to

Cemetery Hill, half a mile south of Gettys-

burg, where the ceremony was to be held.

When Potter reached the top of the

hill, he noticed that the new cemetery

(located adjacent to the old) was "laid out

in a semi-circular form, each State

being allotted ground in proportion to its

dead . . . . The lines dividing these

allotments are the radii of a common center,

where a flag-pole is now raised, but

where it is proposed to erect a national monu-

ment. The trenches follow the form of

the circle, and the head of each is walled

up in a substantial manner [to hold the

headstones to be erected later]. The bodies,

enclosed in neat coffins, are laid side

by side, where it is possible; the fallen of

each regiment by themselves, the heads

toward the center. Boards bearing the

name, regiment, and company are put up

temporarily."33

Newspaperman Isaac Jackson Allen, from

his position atop Cemetery Hill,

observed the panoramic view of the

countryside and was deeply stirred. "From

this point," he wrote with feeling,

"the landscape is beautiful . . . . and as the

undulating valley, rich with fertile

fields and dotted with glistening white farm-

houses, goes rolling on and on towards

the distant mountains, that stand like a

giant framework to this lovely picture

of peacefulness, and quietude, we could

scarce comprehend that all this had so

recently been the theater where was enacted

one of the great tragedies of

war."34

31. Washington Daily Morning

Chronicle, November 21, 1863; Cincinnati Commercial, November

21, 1863.

32. Ibid., November 23, 1863.

33. Ibid. Some have mistakenly

attributed the Gettysburg dispatches in the Commercial to Murat

Halstead rather than Martin D. Potter.

Halstead was with General Meade's army in November of

1863. Halstead earlier, when the war was

going badly, had called Lincoln a blockhead and Grant a

drunkard. The proprietor of the Commercial

used good judgment in sending Potter rather than Hal-

stead to Gettysburg. Ohio State

Journal, November 23, 1863.

34. Ibid.

Gettysburg Soldiers' Cemetery

89

As the sentimental scribe looked

northward, he saw the town of Gettysburg,

a beehive of activity, encompassed in

the morning's sunlight. Northward also lay

the rolling countryside where many Ohio

soldiers had given their lives in the first

day's fighting on July 1. West of

Gettysburg he could see the outline of McPherson's

Ridge near which Major General John F.

Reynolds had fallen, victim of a well-

aimed sharpshooter's bullet. When Allen

turned his eyes south, he saw the Union

line's earthworks before which Pickett's

Confederate division had made its fateful

assault in the face of murderous musket

and artillery fire on the third day's fight-

ing. Allen noticed that Cemetery Ridge,

even yet, was "grim and ghastly with the

mute memorials of strife and

carnage." He saw the "soiled fragments of uniforms,

in which heroes had fought and died,

remnants of haversacks and cartridge-boxes,

and other mementoes of that terrible

conflict, still lay strewn about . . . still lower

down the hill side, is seen a mound of

earth covering the decaying remains of the

artillery horses which were slain by the

side of the masters whom they served

on that dreadful field."35

Newspaperman Allen then took a leisurely

walk to Culp's Hill where nine

Ohio regiments and two batteries had

fought heroically to repulse Confederate

attempts to capture that stronghold on

the second day of fighting. While musing

on "the tragic scenes" which

had transpired there, he was joined by a soldier

who had stood behind those rude

breastworks and battled bravely in defending

the hill against the persistent rebel

attacks. He pointed out the places "where

heroes fought and fell," and the

trees "scarred and marred with ball and shell."36

After a brief visit to the small

farmhouse which had been General Meade's

headquarters, Allen hurried back to the

platform which had been erected near

the new cemetery especially for the

dedication ceremonies. The sound of martial

music greeted the ear, and when he

looked northward he could see the long pro-

cession moving along the road toward the

point he occupied. The military escort

consisting of one regiment of infantry,

one squadron of cavalry, and two batteries

of artillery moved toward the platform

to the blaring music of the Marine Band,

which held second spot in the long

procession. Allen noticed that "President

Lincoln had joined in the procession on

horseback . . . and is the observed of all

the observers."37 Riding

with the military escort was General Robert C. Schenck.

The Ohio officer had fought valiantly at

Second Bull Run until he was wounded

and sent to the rear to have his injury

bandaged. Even more important, perhaps,

he had bested Clement L. Vallandigham, a

pro-peace crusader and critic of the

Lincoln administration, in a hotly

contested congressional election the previous

fall. The general and his staff had

boarded the President's special train in Balti-

more, and, after his arrival in

Gettysburg, Ward H. Lamon gave him a prominent

place in the procession. Another Ohio

newspaperman, witnessing Schenck and

his steed, characterized the

congressman-elect as "the finest looking officer of

them all."38

Next came the "marshal's

division" commanded by Lamon. This group included

President Lincoln, three members of his

Cabinet, and two of his personal secre-

35. Ibid.

36. Ibid.

37. Ibid

38. Columbus Express, November

21, 1863. Democrats had a different view of Schenck. The

Stark County Democrat, October

28, 1863, stated: "Schenck, the tyrant of Baltimore, will leave the

army and take his seat in Congress at

the approaching session. A good 'riddance' for the army, but

what an infliction on Congress and the

decent men in it."

|

|

|

taries. On reaching the grounds, the President, dressed in black and wearing a crepe band around his stovepipe hat, dismounted, and marshal Lamon escorted him and his party to the platform. Dozens of persons, including ex-Governor William Dennison of Ohio, exchanged greetings or comments with Lincoln. While the President visited briefly with the many distinguished guests as he made slow headway toward his chair, the remainder of the long drawn-out procession moved toward the hilltop. When some members in the Ohio delegation, commanded by Colonel Lofland and last in the procession, realized that they would have little chance to see and hear the speakers, they "broke ranks and charged indiscriminately upon the crowd in front of the stand," creating consternation and confusion. A few secured good places near the platform, but the majority were so far from the speakers that they could see or hear little--"and soon wandered off to ramble over the battlefield."39 It required almost two hours to arrange the multitude around the platform. Both Governor Tod, "gruff" and disgruntled, and Governor-elect Brough, of "massive frame" and self-confident demeanor, took seats in the second row of chairs on the huge platform--right behind the place reserved for the President. Members of Ohio's press corps, designated by Tod as members of his staff, "pro tempore," had places on the stage, but mostly in the back rows. General Schenck and ex-Governor Dennison had seats on the north end and were not seated with Tod and Brough. Ohio had more honored guests than any other state, so the state's representatives had an excellent chance to hear every speaker.40 It was about 11:30 A.M. before the President, accompanied by Secretaries Seward, Blair, and Usher, was able to ascend the steps leading to the platform 39. The Cabinet members were Seward, Usher, and Blair. Lincoln's two personal secretaries, flanking him, were John Hay and John Nicolay. William T. Coggeshall, editor of the Springfield Republic, had a seat on the platform even though his name was not on the list of those "Accepting Governor's Invitation." Springfield Republic, November 30, 1863. 40. Cincinnati Commercial, November 21, 1863; John Russell Young, Men and Memories: Personal Reminiscences (New York, 1901), 59. Potter of the Commercial, after looking around him, concluded that the platform held a greater number of distinguished men than ever before assembled on one platform in the country. Eight governors, including Horatio Seymour and Tod, occupied seats in the first two rows. |

Gettysburg Soldiers' Cemetery

91

and make his way toward his chair, in

the front row and near the center of the

stage. Tod and Brough, who had already

been escorted to their seats by marshals

Earl Bill and George Senter, stood up,

obeying protocol. When Lincoln came

near, Tod, in hearty manner, said,

"Mr. President, I want you to shake hands

with me." Lincoln cordially

acquiesced. Then Tod introduced Governor Brough

to the President, who said, "Why, I

have just seen Governor Dennison of Ohio-

how many more Governors has Ohio?"

"She has only one more, sir," replied

Brough, "and he's across the

water."41

President Lincoln, in turn, introduced

Tod and Brough to Seward. Tod told

Seward that he had called on him earlier

in the morning but did not find him.

Seward replied that he and the President

had visited the battleground west of

Gettysburg early in the morning.

"Well, Governor," Seward added, "you seem

to have been to the State Department and

to the Interior, I will now go with you

to the Post Office Department."

Whereupon Seward turned to Montgomery Blair

and "introduced Governors Brough

and Tod to him."42

After all those on the platform were

seated, Birgfield's Band opened the formal

program with a grand funeral march.43

Next, Rev. Thomas H. Stockton, chaplain

of the House of Representatives, gave

the invocation--"a prayer which thought it

was an oration," by one account.

The Marine Band then played a number, during

which the dignitaries alternately

listened and visited.44

As the melodies of martial music drifted

over the nearby hills, the Honorable

Edward Everett arose to deliver his

scholarly oration, replete with copious his-

torical allusions. As he spoke into the

second hour, many in the audience grew

restless and "bits of the

crowd" broke off to wander over the battlefield.45 Those

seated on the platform stared off into

space or studied the expressions of the other

guests who were waiting for the rambling,

two-hour address to end. Martin D.

Potter of the Cincinnati Commercial registered

his observations for posterity. He

saw the President, with his

"thoughtful, kindly, care-worn face," listening intently.

He observed Seward, with "a wiry

face" and "bushy, beetling eyebrows," sitting

with arms tightly folded and his hat

"drawn down over his eyes." He noted the

"absolutely colorless" face of

Rev. Stockton with his "lips as white as the wasted

cheek, and the flowing hair, and tuft of

whiskers under the chin, as snowy white

as wool." Potter also looked at Tod

and Brough, fidgeting on their uncomfortable

chairs. He characterized the former as

"good-humored, florid, and plump" and

the latter as "the Aldermanic Governor-elect

of Ohio."

When Everett, exhausted ("the

two-hour oration telling on him"), finished,

applause was slight, "the audience

being solemnized too much by the associations

and influence of the spot to be more

demonstrative." Also, quite possibly, the

41. The conversation was reported in the

Washington Morning Chronicle, November 21, 1863.

Could the reference have been to Thomas

Corwin, onetime governor, then minister to Mexico?

U. S. Marshal Earl Bill apparently had

been added to the marshal corps when he arrived in

Gettysburg.

42. Ibid. Seward was Secretary of

State, Usher, Secretary of the Interior, and Blair, Postmaster-

General.

43. Cincinnati Commercial, November

21, 1863. The band, from Philadelphia, was sponsored by

the Union League. Its inclusion in the

program was a concession to John W. Forney, ex-Philadelphian

and editor of the Washington Chronicle.

44. John Hay, diary entry of November

20, 1863, in Tyler Dennett, ed., Lincoln and the Civil War

in the Letters and Diaries of John

Hay (New York, 1938), 119-120.

Coggeshall of the Springfield

Republic, November 30, 1863, characterized the opening prayer as

"eloquent."

45. Young, Men and Memories, 71.

92

OHIO HISTORY

abstract character of the speech was

inappropriate for the audience assembled.

President Lincoln and Secretary of State

Seward offered Everett their hands in

congratulations. The crowd shuffled

about restlessly; then twelve men of the Union

Musical Association of Maryland sang a

hymn written especially for the occasion

by Benjamin B. French. This was an

exceptional number, emotional and well

rendered--it spoke of "holy

ground," "Freedom's holy cause," and "mourn our

glorious dead."46

As applause diminished, Ward H. Lamon

introduced Lincoln. The President

arose, took a "thin slip of

paper" out of his pocket, and proceeded to the front

of the stage. There was a rustle of

expectation and a visible attempt of many to

get nearer the stand. Those on the outer

fringes, including some Ohioans, pushed

to get nearer the President, trying

"to make two corporeal substances occupy

the same space at the same time."47

After first adjusting his glasses, but

then discarding them and the paper because

he seemed unable to focus his eyes in

the bright sunlight, the President delivered

his address unaided by notes. Though

short, the Washington Chronicle said

it "glittered with gems, evincing

the gentleness and goodness of heart peculiar

to him, and will receive the attention

and command the admiration of all the

tens of thousands who will read

it." Isaac Jackson Allen of the Ohio State Journal

noted that Lincoln was interrupted by

applause five times. He also noticed that

when the President uttered the words,

"The world will little note, nor long remem-

ber what we say here, but it can

never forget what they did here," a stalwart

officer, wearing a captain's insignia

and with one empty sleeve, buried his face

in his handkerchief and "sobbed

aloud while his manly frame shook with no

unmanly emotion." After "a

stern struggle to master his emotions, he lifted his

still streaming eyes to heaven and in

low and solemn tones exclaimed, 'God

Almighty bless Abraham

Lincoln.'" Allen thought it was

evident that Lincoln's

appropriate remarks "had touched

the responsive cords [of] feeling, that Everett's

finished oratory had failed to

reach."

When the President finished his short

address, the audience gave him a "long

applause," followed with three

cheers for Lincoln and three more for the

governors.48

Next came a dirge, followed by the

benediction pronounced by the Reverend

Henry L. Baugher, president of the

Lutheran seminary located on the outskirts

of Gettysburg. Marshal Ward H. Lamon

then arose, stepped to the front of the

platform, and announced that the

Honorable Charles Anderson, Lieutenant Gov-

ernor-elect of Ohio, would deliver an

address at the Presbyterian church in Gettys-

burg at five o'clock. Lamon, speaking

for Governor Tod, invited the President and

members of his Cabinet, and all others,

to attend the "Ohio program." He then

proclaimed the assemblage dismissed.49

46. Cincinnati Commercial, November

23, 1863. The Union Musical Association of Maryland was

listed in some reports as the Baltimore

Glee Club.

47. A myriad of myths about Lincoln's

"Gettysburg Address" have developed. All interested in

the ceremonies should read Louis A.

Warren, Lincoln's Gettysburg Declaration: "A New Birth of

Freedom" (Fort Wayne, 1964) and Long Remembered: Facsimiles

of the Five Versions of the Gettysburg

Address in the Handwriting of Abraham

Lincoln, with Notes and Comments on

the Preparation of the

Address by David C. Mearns and Lloyd A.

Dunlap (Library of Congress, Washington, 1963). See also

John Y. Simon, ed., "Reminiscences

of Isaac Jackson Allen," Ohio History, LXXIII (Autumn 1964),

225-226.

48. Ibid.; Washington Morning

Chronicle, November 21, 1863; Ohio State Journal, November 23,

1863.

Gettysburg Soldiers' Cemetery

93

While the marshals reformed the

procession, a battery of the Fifth New York

Artillery fired a salvo of eight rounds.

William T. Coggeshall of the Springfield

Republic watched the reforming of the procession. He thought the

President "a

timorous, but respectable

horseman," and that Seward seemed "much more at

home with a pen in his hand than with a

bridle rein."50

After the procession reached Gettysburg

and dispersed, most of the notables,

including Dennison, Tod, and Brough,

assembled at David Wills's home for a

three o'clock dinner, followed by an

hour-long reception. During the reception

President Lincoln took his place in the

hall opening on York Street and greeted

guests as they entered. While the

reception was in progress, a side show took place

before the residence where Horatio

Seymour of New York was staying. The Fifth

New York Artillery Regiment marched in

review as Governor Seymour and Major

General Schenck stood on the front

porch. Seymour presented the unit with the

new silk regimental banner, a gift of

the merchants of New York City. He also

made a three-minute speech advocating a

vigorous prosecution of the war and

asking the artillerymen to bring added

honors to the banner. He then called upon

General Schenck for a few words. The

eminent Ohioan spoke briefly and eloquently,

thanking the regiment for past heroics

and challenging the proud soldiers to win

further honor and glory for themselves

and their state.51

Shortly before five o'clock a large

crowd assembled at the Presbyterian church

to hear Colonel Anderson's oration.

Ex-Governor Dennison presided over the meet-

ing while Isaac Jackson Allen served as

secretary. Dennison, as prearranged, called

on Tod to say a few words. Aware that

Ohio Democrats had abused him for dip-

ping into state funds to subsidize the

"junket" to Gettysburg, Tod defended his

actions in cooperating with the sponsors

of the new cemetery. He was happy to

know that "one and all" in the

Ohio delegation approved of his decisions relating

to the state's participation in the

day's proceedings. The respect paid to "the honored

dead would be gratefully remembered by

their kindred," giving cheer to the grief-

stricken mothers and friends of

"those who had fallen here." These bereaved would

be heartened to know that "the

virtuous and the good of their immediate neigh-

borhood" fully appreciated the

cause for which they had died.52

Dennison then invited General Schenck to

give a short impromptu, speech,

but he declined the honor in a few brief

words. Just then John Burns, "a grave

and venerable old man of seventy, clad

in the common costume of a country

farmer" in the company of President

Lincoln, Secretary Seward, and Secretary

Usher, entered the hall. Burns was there

as the President's "honored guest," and

the audience seemed more interested in

him than in the three important public

figures.53

49. Washington Morning Chronicle, November

21, 1863.

50. Springfield Republic, November

30, 1863.

51. Cincinnati Commercial, November

23, 1863; Columbus Express, November 21, 1863.

52. Cincinnati Commercial, November

23, 1863.

53. During the afternoon reception at

the Wills's house, Lincoln had expressed a desire to meet

John Bums, the seventy-year old local

constable-cobbler, veteran of the War of 1812, who, when hear-

ing that the rebels were outside of

Gettysburg, grabbed his musket and first joined the One Hundred

and Fiftieth Pennsylvania volunteers and

later fought with the Iron Brigade, trying futilely to hold the

line against the overwhelming attack of

the Confederate forces west of Gettysburg the first day of

battle. David Wills hunted up the

gray-haired fellow and introduced him to Lincoln, and the Presi-

dent then took him over to the

Presbyterian church to hear Anderson's oration. Bret Harte's ballad,

"John Burns of Gettysburg,"

helps perpetuate some of the myths about Burns. Ohio State Journal.

November 23, 1863; Battles and

Leaders of the Civil War (New York, 1884), 276.

94 OHIO

HISTORY

After order was restored, Dennison

introduced Colonel Anderson as not only

a well-known orator but also "as a

soldier who at the head of his regiment, in the

Battle of Stone [Stones] River, had shed

his blood in the cause of his country."54

The speaker began by acknowledging the

role of Ohio troops in the battles of Get-

tysburg, and, as Lincoln had earlier

done, paid tribute to the gallant soldiers

who had died for "the cause."

He characterized the Confederate invaders turned

back at Gettysburg as "the army of

treason and despotism." "That host of rebels,"

Anderson asserted, "deluded and

sent hither by conspirators and traitors, was

vanquished, and fled cowering in dismay

from this land of Penn and Franklin,

of Peace and Freedom, across the

Potomac, into the domain of Calhoun and Davis,

of oligarchic rule and despotic

oppressions." A rebel victory would have turned

back civilization and set back the

ideals of freedom and democracy. Then, turn-

ing his face upward, he spoke as if he

heard the voices of the dead Union soldiers,

their mute lips conveying the message:

We have died that you might live. We

have toiled and fought--have been wounded and

suffered in keenest agonies, even unto

death, that you might live--in quietude, prosperity,

and in freedom. Oh! let not such

suffering and death be endured in vain! Oh! let not such

lives and privileges be enjoyed in

ungrateful apathy toward their benefactors! Remember

us in our fresh and bloody graves, as

you are standing upon them. And let your posterity

learn the value in the issues of that

battle-field, and the cost of the sacrifice beneath its

sod.55

Along with other topics Anderson

discussed the factors and forces which had

brought a new nation into being and

lauded the ideals of this nation, "God's best

hope on earth." Dwelling upon the

consequences of disunion, he scolded the Peace

Democrats, couching his criticism in

rhetoric and metaphors. He borrowed from

the abolitionists when denouncing

slavery as an evil and the slave-catchers as

devils incarnate. After defending

Lincoln's emancipation policy, Anderson tried to

convince northern workingmen that the

freed blacks would not compete with

them for jobs nor create social problems

in the northern cities because "climate,

custom, and society with their likes and

equals will conspire to withhold the absent

and withdraw from us those who are now

here."

Anderson closed his discourse with an

oratorical flourish. Yes, he wanted these

honored dead remembered for all time.

They, like the founding fathers of the

nation, had striven to enthrone and

enshrine American liberty. These soldiers had

not died in vain; they were martyers to

a cause and their blood sanctified the

country's ideals. The orator took his

seat amidst resounding applause. The Ohio

State Journal reported that "Both the President and Mr. Seward

expressed great

satisfaction with Col. Anderson's

effort, and complimented the Ohio delegation

upon the spirit and energy displayed by

the earnest manner in which they had

joined in the work of securing and

dedicating the National Cemetery." The speaker

gloried in the compliments and praise

heaped upon him. Actually, he had made

a more effective speech in forty minutes

than Edward Everett had in two hours.

After Anderson's speech, Isaac Jackson

Allen introduced three resolutions:

Resolved, That the thanks of the Ohio delegation be tendered to

the citizens of Gettysburg

for the generous hospitality extended to

us on the occasion of our present visit.

54. Cincinnati Commercial, November

23, 1863.

55. The speech was given in full in ibid.;

see also Earl W. Wiley, "Colonel Charles Anderson's

Gettysburg Address," Lincoln

Herald, LIV (Fall 1952), 14-21.

Gettysburg Soldiers' Cemetery

95

Resolved, That the thanks of the delegation be tendered to Col.

Anderson for his able and

eloquent Address, and that he be

requested to publish the same.

Resolved, That the thanks of the delegation be extended to the

officers of the Presbyterian

Church for the favor conferred by the

use of their church building on this occasion.56

After the Ohio program ended, many of

the visitors headed for the railroad

station to await their respective

trains. The President's train, with Colonel Anderson,

Governor-elect Brough, and General

Schenck aboard, left for Hanover Junction at

eight o'clock. The "Governors'

Special," carrying Tod and most of the members

of the Ohio delegation, moved off an

hour later. At the Junction, while awaiting

the arrival of the east and westbound

trains, the passengers spent time in "easy

conversation" as the governors and

members of the Ohio delegation gathered around

Mr. Lincoln. Writing later, Allen of the

Ohio State Journal said he had a seat very

near and could see that the President

"was suffering from a grievous headache.

from sitting with his head bared in the

hot sun during the exercises of the day.

Resting his elbow on the arm of his

chair, he leaned his head on his hand, listened

and smiled at the quaint sayings of

those around him, but joined sparingly in

their conversation."57)

The President's train came to the

Junction about midnight, bringing the story-

telling session to an end. Brough,

Anderson, and Schenck climbed aboard the

Washington-bound train--Brough for

meetings with the President and Secretary

of War Edwin M. Stanton next day, and

Schenck to return to Baltimore and the

command of the Middle Department. Tod

and members of the Ohio delegation

had to wait for their train until eight

o'clock the next morning, taking part in

some "tall cussing" during the

interim. "The amount of blasphemy manufactured

at the little hotel [in Hanover

Junction] was considerable," wrote an interested

observer, "and contrasted very

harshly with the solemn events of the day" "A

good deal of indignation is manifested

by people at the poor railroad accommoda-

tions," wrote Martin D. Potter of

the Cincinnati Commercial, "and the Northern

Central is in worse repute than

ever."58

Every Ohioan, however, did not leave

Gettysburg on the evening of the nine-

teenth. Several reporters, some soldiers

on furlough, and parents or brothers of the

reburied dead, stayed over to tour the

battlefield and dream of other days. Editor

John S. Stephenson of the Cleveland Plain

Dealer--he was one of the few Demo-

cratic (with Unionist tendencies)

editors who had made the pilgrimage to Gettys-

burg at the state's expense--spent two

days visiting the various areas where war

god Mars had reaped the heaviest

harvest. On the twentieth he and two Cleve-

land soldiers, recuperating from wounds

received during the battle, as guides,

and the many sightseers visited those

sectors where the Ohio regiments had fought

so well. Stephenson collected some

relics or mementoes: a bloody handkerchief,

56. Cincinnati Commercial, November

23, 1863; Ohio State Journal, November 23, 1863; "The

Ohio Delegation at Gettysburg,"

162. Anderson borrowed heavily from a speech which he had delivered

in Xenia on May 2, 1863, and which had

subsequently been published as a propaganda document and

broadcast over Ohio during the bitter

Brough-Vallandigham gubernatorial campaign. Anyone interested

in Civil War dissent in general or

Vallandigham, see Frank L. Klement, The Limits of Dissent: Clement

L. Vallandigham and the Civil War (Lexington, 1970).

57. Cincinnati Commercial, November

23, 1863; Simon, "Reminiscences of Isaac Jackson Allen," 226.

58. Harrisburg Weekly Press and

Union, November 21, 1863; Cincinnati Commercial, November

21, 1863. In the official report, the

delay was described as "a little railroad detention." "The Ohio

Delegation at Gettysburg," 163.

|

a soldier's cap pierced by a ball, a handful of round and conical bullets, and a skull bleached by the sun.59 "A great many citizens of Gettysburg," also noted Potter of the Cincinnati Commercial, "are in the relic business, and sold immense numbers of shot and unexploded shell, during the day, at stiff prices." Editor Stephenson, a man of con- siderable foresight, predicted that the battlefield would become "an American mecca," to which "thousands of sorrowing parents and others" would make "annual pilgrimages, to visit the last resting places of the loved ones." More than that, future generations would visit the grounds in great numbers, out of curiosity and respect, paying tribute to the brave "who gave their lives that the nation might live."60 The story of the dedication ceremonies did not end with Lincoln's return to Washington and Tod's to Columbus. Most Unionist newspapers published Lincoln's brief address and Everett's long oration in full. The editors of these papers, still concerned about the Converse letter, went out of their way to praise Tod for his role in honoring Ohio's and the nation's dead. W. H. Foster of the Columbus Express, for example, saw the furthering of the democratic ideal in the Gettys- burg ceremonies which witnessed the gathering of the great and the lowly, the 59. Cleveland Plain Dealer, November 23, 1863. 60. Cincinnati Commercial, November 21, 1863; Cleveland Plain Dealer, November 23, 1863. |

Gettysburg Soldiers' Cemetery

97

chief of state and yeomen farmers,

famous generals and unknown privates, resi-

dents of the nearby towns and the

"scholars, poets and artists of New England."

"It was good to be there," he

added, "and to be rebaptised in the spirit of patrio-

tism, and devotion to human

liberty."61

Most Democratic newspapers, on the other

hand, either played down the events

of November 19 and did not publish the

text of the speeches, or openly criticized

the speeches and belittled the

Republicans' efforts. The Crisis (Columbus) and the

Circleville Democrat, for

example, published in full the speech which Clement L.

Vallandigham, in Windsor (Canada West)

as an exile, gave to a visiting delegation

of students from the University of

Michigan. The Crisis, in a discussion of the

general topic of states' rights,

criticized Lincoln's Gettysburg speech in regard

to his division of power: 'of the

people, by the people, and for the people,' but

said no more about the ceremony; and the

Circleville Democrat described the

ceremony in only one paragraph.62 James

A. Estill of the Holmes County Farmer

(Millersburg) regretted the "bitter

partizanship" which "was evinced by the aboli-

tionists," especially before and

after the dedication ceremonies. "The abolition

leaders," Estill added, "acted