Ohio History Journal

|

The Nomination of Rutherford Hayes for the Presidency by KENNETH E. DAVISON |

96 OHIO HISTORY

The Nomination of

Rutherford Hayes

for the Presidency

For the first time since the Civil War

the Republican party faced the

possibility of defeat in 1876, so strong

was public sentiment against the cor-

ruption of Grant's administration. The

Republican candidate would have

the handicap of representing the

scandal-torn party in power; his Demo-

cratic opponent would possess the great

political advantage of being able

to attack the policies and personnel

associated with a poor President. Thus

the choice of a safe Republican

candidate acceptable to a majority of the

convention delegates but not intimately

connected with Grant or any part

of the new coalition was of the greatest

importance if the party wished to

stay in power. "The Great

Unknown" became the manner of describing

this leader in the weeks preceding the

Cincinnati Convention of June 1876.1

On the eye of the convention four major

contenders vied for support:

Representative James G. Blaine of Maine,

Senator Roscoe Conkling of New

York, Senator Oliver P. Morton of

Indiana, and Secretary of the Treasury

Benjamin H. Bristow of Kentucky. Three

other men were put forward as

favorite sons by their state

delegations: Postmaster General Marshall Jewell

of Connecticut, Governor Rutherford B.

Hayes of Ohio, and Governor John

Hartranft of Pennsylvania. Of these

three only Hayes was a serious con-

tender; the Jewell and Hartranft

candidacies were intended merely as hold-

ing operations until the balloting

narrowed down to two or three candi-

dates.

Blaine, the congressional candidate,

held a commanding lead in delegate

strength, yet lacked nearly 100 votes to

win the nomination on the first

ballot. He was the only national

candidate in the group having first ballot

supporters in 36 of the 49 states and

territories. Like Henry Clay before

him, he inspired great devotion among

his followers. Blaine compensated

for his lack of a military record by

using his great oratorical powers to

brand the South as tile region of

rebellion. Such tactics won both firm

friends and bitter enemies. Although he

became a member of the rules

committee and Speaker of the House, the

striking weakness of Blaine on

Capitol Hill appeared in the notable

lack of constructive legislation bear-

ing his name.

Senator Conkling, another brilliant

orator, disliked Blaine intensely from

the day Blaine mercilessly described his

"turkey gobbler strut." Conkling

who controlled the New York State

Republican organization, was more

closely identified with President Grant

than any other Republican and

hence was the acknowledged

administration candidate. With only token

support outside his own state, Conkling

could undoubtedly deliver the large

New York delegation as he willed. This

represented alone nearly one fifth

of the votes needed to nominate a

standard bearer.

NOTES ON PAGE 194

HAYES NOMINATION for the PRESIDENCY 97

Senator Morton, Indiana's brilliant war

governor and long a champion

of Negro rights, controlled the party

machinery in his pivotal state, and

held the confidence of the southern

carpetbag delegations. Morton, unlike

his major rivals, had a record of solid

executive and legislative accomplish-

ment, in addition to outstanding

oratorical skill. His great handicap was

physical; since 1865 he had suffered

from paralysis of the legs. Hayes ad-

mired Morton and knew him best of the

leading contenders.

Benjamin H. Bristow was the favorite of

the reformers because as Secre-

tary of the Treasury he had vigorously

prosecuted the Whiskey Ring con-

spirators. His backers included most of

the Liberal Republicans of 1872,

eastern conservatives, Cincinnati

newspaper editors and Chicago business

leaders. Although his delegate strength

was thin, it was widely distributed

over New England, the South, and Middle

West.

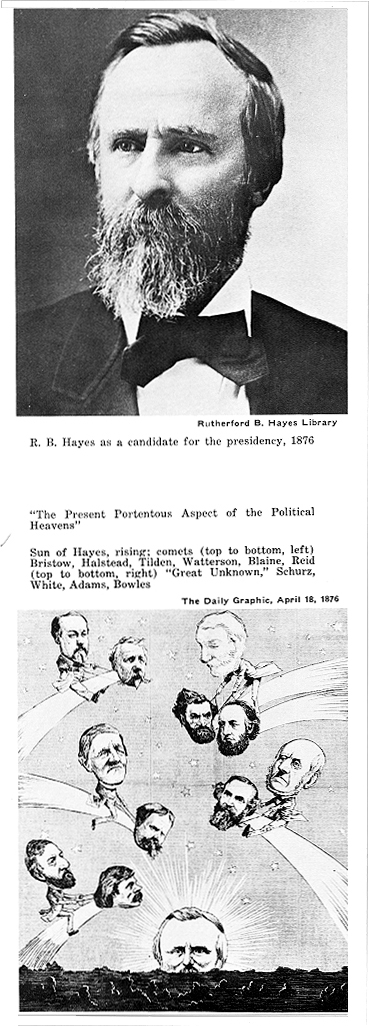

Hayes became a promising Republican

presidential possibility when he

won an unprecedented third term as

governor of Ohio on October 12, 1875.

Later that same month he stumped

Pennsylvania with Governor John Hart-

ranft, everywhere addressing large

crowds and receiving much attention as

a rising leader in the party. At

Harrisburg the politically powerful Cam-

eron family entertained him. His age,

war record, executive and legislative

experience, demonstrated vote-getting

ability, and the importance of Ohio

in national politics all combined to

make him an attractive candidate for

the party's highest honor.2

Ohio friends of Hayes began organizing

in January 1876. Senator John

Sherman, after consulting with Representative

Charles Foster, put his polit-

ical prestige behind the governor by

writing a letter to state senator A. M.

Burns promoting Hayes as the favorite

son choice of the Ohio convention

delegation. Hayes received a unanimous

endorsement from the 750 member

state party convention on March 29,

1876.3

Hayes, inwardly calm and outwardly

indifferent, gave no public sign of

seeking his party's nomination.

Privately he kept in unbroken communica-

tion with his managers.4 Some

of them feared he might break his silence,

declare himself an avowed candidate, and

hurt his favorable position.

"Write no letters," said one.

"Let well enough alone." "For God's sake

avoid all entangling alliances with the

present administration," warned

another.5 Such advice was unnecessary.

The Governor understood his polit-

ical situation perfectly, read his

informant's dispatches diligently, and let

the nomination manage itself. At the

very least, nearly everyone conceded,

the vice-presidential nomination would

be his if he wished to accept it.6

Privately Hayes supported Bristow to

head the ticket knowing full well this

would be to his benefit if the

Kentuckian's chances faded.7

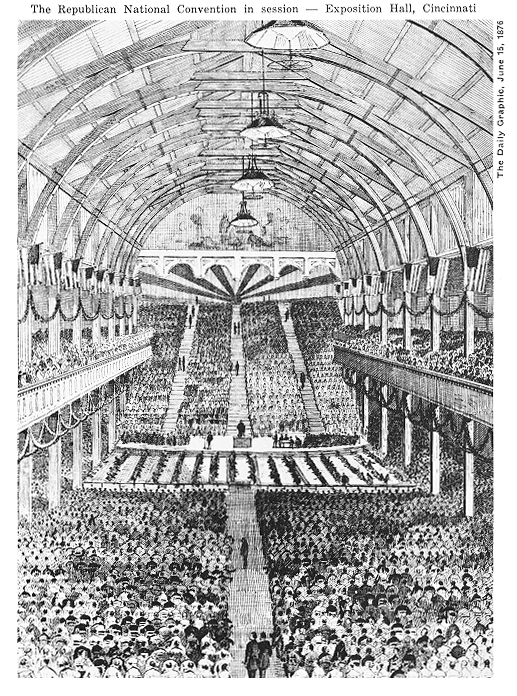

The choice of Cincinnati's Exposition

Hall as the convention site, orig-

inally expected to aid the Bristow and

Morton candidacies, ultimately

worked to aid the Hayes cause. Of all

the cities in America, Cincinnati alone

could consider Hayes as her very own,

for here he had begun his legal and

political career in earnest. Here he

joined the famed Literary Club, mingled

in polite society, and married Lucy

Webb. From here he went to war, to

Congress, and the State House.

98 OHIO HISTORY

A week of great excitement in Cincinnati

began on Friday, June 9 as

many of the delegates to the national

Republican convention, unofficial

supporters of the leading candidates,

and total strangers poured into the

city. The Reform Club of New York,

numbering about fifty or sixty men,

all for Bristow, arrived early Saturday

morning at the Gibson House. The

New York City Republican Club, composed

of 200 strong and accompanied

by a fine band, all in Conkling's

interest, put up at the Grand Hotel. Other

groups from Philadelphia and Pittsburgh

with two more splendid bands,

arrived on Monday and registered at the

Arlington and Burnet House. A

whole host came from Indianapolis in

Morton's behalf on Tuesday.8

The Bristow Club of Cincinnati,

numbering between 2000 and 3000, en-

gaged Pike's Opera House and Currier's

Band for the week of the conven-

tion. Flags were hung out all over the

city, and the hotels were draped in

the American colors, and at night

handsomely illuminated. The Grand

Hotel had a semi-circle of colored

lights over the main entrance, and just

under them a row of gas jets arranged so

as to spell the name of ROSCOE

CONKLING. The Burnet House had a similar

row of gas jets in front of

the building spelling the name of JAMES

G. BLAINE. The Bristow Club

hung a strip of muslin across Fourth

Street in front of Pike's Opera House

bearing the inscription BRISTOW and

REFORM. The Morton and Hayes

delegates were not quite so conspicuous

in their display, although they too

had their respective headquarters and

flags, and banners, with the names of

their favorites stitched on.

Excitement and enthusiasm grew feverish

long before the convention as-

sembled on Wednesday morning. Each

evening the hotels were brilliantly

illuminated and bands played in front of

their respective headquarters.

People milled about in great masses

choking traffic, and amid the din ora-

tors extolled the merits of the

Republican party or their favorite candidate

for the nomination. Other crowds surged

through the streets. Cheers and

fire works rent the air. Red and green

lights burned on nearly every corner.

Meanwhile political workers sounded the

sentiments of delegates and visi-

tors, attempting to win them over by argument,

entreaty, or promises. Odd-

ly there was no fighting, no drunkeness

to speak of, and little unseemly

conduct.

The supporters of Conkling were the

first on the scene and they worked

hard in his cause. However, theirs was

an up-hill struggle, and it was gen-

erally known before the convention

opened that the New Yorker stood no

real chance of being nominated. The

Morton men began with more votes

than Conkling, but they did not arrive

so early or work so hard for their

candidate. By evening on Wednesday, the

first day of the convention, they

conceded Morton could not be nominated

either.

The Blaine backers also arrived early

and in great numbers. They had

among

the delegates nearly 200 who were instructed, or requested to vote

for him, and a large number among the

uninstructed delegates who made

no concealment of their preference for

him either at the time they were

elected or during the week of the

convention. With so many votes already

secured, it was easy for his managers to

persuade other uncommitted dele-

HAYES NOMINATION for the PRESIDENCY 99

gates to come over to Blaine. They

assured those who were tempted by pa-

tronage prospects that he was destined

to win and they might as well join

the bandwagon early and thus merit his

recognition and favor. Whenever

they found anyone with malice against

the South, they boasted how James

G. Blaine's oratory discomfited the

rebels in the House of Representatives.

They said if he were only elected President,

his would be the most brilliant

administration the world ever saw. They

spoke of his eloquence and power

as a speaker and claimed no one could

make a livelier canvass or such a

glorious success as he. They said

nothing about his using his position and

influence as Speaker of the House to

forward railroad schemes in which he

was interested; they said nothing about

his own letters which proved him

to be speculating in stocks, whose value

depended wholly on Congressional

legislation. In short, they said nothing

of all the disreputable and suspicious

circumstances surrounding his past life

and overshadowing the future of

their candidate.

Meanwhile, on Sunday, June 11, Blaine

suffered a sunstroke on the steps

of a church in Washington. For two days

he lay unconscious and the report

went out that he was dying. No one

wished to say hard things against a man

who was lying at death's door, no matter

how true they might be, and so

during the rest of Sunday, Monday and

Tuesday, the friends of Blaine

worked on the sympathies and feelings of

the crowd. Even Hayes, who felt

that Blaine's nomination would be fatal

to the cause, was nonetheless moved

to send a highly emotional message, a

rare response indeed for him:

I have just read with the deepest sorrow

of your illness. My eyes are

almost blinded with tears as I write.

All good men among your coun-

trymen will pray, as I do, for your

immediate and complete recovery.

This affects me as did the death of

Lincoln. God bless you and restore

you.9

On Tuesday Blaine's fever passed, and he

sent a message of convalescence

to Eugene Hale and William P. Frye, his

managers at Cincinnati. Reassur-

ing telegrams were sent nearly every

hour of the day thereafter to some one

or other of his friends to be posted in

the bar rooms of hotels and on the

bulletin boards in various newspaper

offices.

Thus Blaine's friends were jubilant and

confident of victory on Tuesday

night. They claimed more than 300 votes

on the first ballot, and that they

would gain enough on the second ballot,

from delegations who had to first

cast one complimentary vote for a

"favorite son," to nominate their man.

But their very confidence was their

undoing. From the fear and depression

created among other managers and

delegates arose a desperate spirit to

combine and defeat Blaine. He was so far

recovered that there was no longer

any fear for life. Speeches were made at

meetings of the Bristow Club, held

in Pike's Opera House, on Tuesday and

Wednesday nights, warning of the

great danger to the Republican party.

The Cincinnati papers, the Commer-

cial and the Gazette, entered the fray with a will

and said boldly that his

nomination would be the ruin of the

Republican party and that they could

not support him. The New York Times did

the same. Carl Schurz and

100 OHIO HISTORY

other Liberals and independents warned

that if Blaine were nominated

they would either support the Democratic

ticket, nominated at St. Louis,

or organize a third party movement. The

claims of Bristow as a reform

candidate were pushed with great

earnestness and too much zeal for his

own good. The Bristow men were

determined that Blaine should not be

nominated if it was possible to prevent

it, and they openly avowed their

intention to "kick" against

the nomination if he won it. This attitude auto-

matically made all of Blaine's backers

sworn enemies of Bristow. Supporters

of Morton and Conkling also were

prejudiced against Bristow since he had

been put forward as "more holy than

they." Further, the regular machine

politicians of the convention were

opposed to him because they said he and

all his supporters were

"kickers" and independents and dangerous fellows

and not true to the party. Others resented

the idea of having a candidate

forced upon them as they insisted

Bristow was, and said that when people

came to them and told them they must

nominate Bristow or perish, they

would rather perish than do it. Thus

Bristow's friends aroused a great deal

of opposition among the different

elements in the convention, and thereby

sacrificed their candidate. They were

loyal to a cause, and not to Bristow,

but in sacrificing him, they insured

Blaine's defeat too. Furthermore, as his

subsequent career suggests, Bristow

lacked presidential stature, and he failed

to effectively lead the reform forces.

The Hayes delegation led by former

Governor Edward F. Noyes, though

present in Cincinnati since the Friday

prior to the convention, kept quietly

in the background. They said nothing

against any of the other candidates

and manifested no preferences for one

over another. They did not even

make any fuss over Hayes, simply saying

they were instructed to vote for

him and should do so while there was any

chance of his success. They were

friendly with the supporters of every

other candidate in the field, were

careful to arouse no opposition, and

ultimately succeeded in making Hayes

the second choice of nearly every

delegate. Young Webb Hayes, in Cincin-

nati as his father's private observer,

wrote a summary of the situation on

Monday evening June 12: "Greatest

good feeling prevails toward you on

all sides...The Ohio men are jubilant

and willing to sleep with any other

of the delegates. All friends--no enemys"

[sic].10

At a meeting of the Ohio delegation held

a day or two before the con-

vention, the work of visitation and

conference with delegates from other

states was assigned to different

members. Among these was Clark Waggoner,

alternate-at-large and Hayes's Toledo

friend. Waggoner kept a small record

book of his activities and carefully

noted the situations of the delegations

visited by him.11 Meanwhile other Hayes

managers, William Henry Smith,

James M. Comly, Ralph P. Buckland, and

A. E. Lee, the Governor's secre-

tary, worked to promote Hayes's

nomination. Another valuable ally inside

the Bristow camp was Stanley Matthews,

intimate friend of Hayes since

Kenyon college days, and brother-in-law

of Dr. Joseph T. Webb, a brother

of Mrs. Hayes. Matthews could take

advantage of any change in Bristow's

fortunes to assist the Hayes cause,

especially since Hayes himself was gen-

erally reported to favor Bristow's candidacy.

By 8 P. M. on Monday evening

HAYES NOMINATION for the PRESIDENCY 101

Smith wired the Governor: "At this

hour I think I can safely predict that

Ohio will win."12

The national convention opened on

Wednesday June 14 at noon, but

before they met, Murat Halstead and

Richard Smith, both Bristow backers,

used their Cincinnati papers, the Commercial

and Gazette, to print solid

columns of protest against the

nomination of Blaine, and issued sheets con-

taining damaging correspondence [the

Mulligan letters] of Blaine, arranged

in the order of their dates, with a

running commentary on the inferences

to be drawn from them.

If the convention would have proceeded

to ballot for president and vice-

president at once, the Blaine men felt

they could have won, but the ballot-

ing was delayed by the tactics of

Bristow's supporters who were endeavoring

to postpone action upon the nominations

as long as possible. They sought

to stall for time so that sober second

thoughts, which they expected would

come to many of the delegates, would

save the party from making a blunder.

The first day was consumed in effecting

a permanent organization,

speechmaking, and appointment of

standing committees.13 Repeated ef-

forts to adjourn failed. That evening

the speechmaking continued giving

time for more earnest talk with the

delegates against the nomination of

Blaine. Thursday morning the papers

renewed their attack on him. Still,

his support was so large that the Blaine

forces had their way in regard to

every decision not directly connected

with his actual nomination. Thus

when a motion was made to exclude the

territories, since they had no elec-

toral votes, from voting for nominees,

the Blaine contingent succeeded in

voting it down and thereby secured for

their candidate twelve to fourteen

additional convention votes. In debating

the report of the rules committee

the proposal to recess after each ballot

was also defeated. Again, when a

vote was taken on the report of the

committee on credentials in favor of

admitting the Jeremiah Haralson

delegation from Alabama, instead of a

rival one headed by Senator George

Spencer which was favorable to Morton

and Conkling, the Blaine men won again

by a vote of 375 to 354. This

maneuver gained another sixteen votes

for their column. On this ballot

the Kentucky delegation voted against

seating the Spencer group, and this

action so antagonized the Indiana

delegation that it probably prevented

Bristow from getting more than five

votes from Indiana when Morton's

name was ultimately withdrawn on the

fifth ballot.

Blaine's group, however, was defeated in

all its attempts to force a vote

for president and vice-president. The

delay, so precious to the candidate's

opponents and so dangerous to him, could

not be overcome by his man-

agers. They had tried on Thursday

morning to have a ballot taken before

the committee on resolutions was ready

to report the platform. In this they

were frustrated. Again, after all the

committees had reported and the plat-

form had been adopted, which happened

during the afternoon of Thurs-

day, June 15, they tried to force the

convention to a nomination. At 2:50

P. M. the same day, the roll of

states was finally called and any with a candi-

date to present was allowed ten minutes

for a speech in his favor. Ex-

Governor Stephen W. Kellogg of

Connecticut nominated Postmaster Gen-

102 OHIO HISTORY

eral Marshall Jewell. This endorsement

was understood to be complimen-

tary, perhaps it would put Jewell in a

favorable position for the vice-presi-

dential nomination. Colonel Richard W.

Thompson of Indiana, an orator

of the old school, nominated Senator

Morton in a fine speech, evoking con-

siderable applause, and the nomination

was seconded by a mulatto, ex-

Governor P. B. S. Pinchback of

Louisiana. Then General John M. Harlan

arose to nominate Bristow. He made a

telling speech, more loudly ap-

plauded by the people in the galleries

than by the delegates, and the nom-

ination was seconded by Luke Poland of

Vermont, George William Curtis,

editor of Harper's Weekly, and

Richard H. Dana of Massachusetts. Curtis

made a fine speech, Poland a dull one,

while Dana unwisely intimated that

Massachusetts would vote Democratic in

November if the convention failed

to nominate Bristow.

Following Dana, Blaine was nominated by

Robert J. Ingersoll of Illinois,

who made the most effective speech of

the day which is still considered to be

one of the great masterpieces of

nominating oratory. He began by turning

on the preceding speaker and saying,

"Gentlemen of the Convention:

Massachusetts may be satisfied with the

loyalty of Benjamin H. Bristow. So

am I. But if any man nominated by tile

convention can not carry the State

of Massachusetts, I am not satisfied

with the loyalty of Massachusetts."14

This was said with tremendous force and

emphasis and brought out an over-

whelming round of applause from the

Blaine delegates. It was a wonderful

turn heaping contempt upon Bristow's

supporters. Then Ingersoll went on

to laud and praise his hero, James G.

Blaine, who "like an armed warrior,

like a plumed knight, marched down the

halls of the American congress

and threw his shining lance full and

fair against the brazen forehead of

every traitor to his country and every

maligner of his fair reputation."15

So many in the convention hall rose and

cheered until it seemed as

though Blaine must be nominated without

a shadow of doubt or wavering.

He undoubtedly would have been if a

ballot could have been taken just

then, or even that afternoon before

adjournment. But this was not to be.

A Negro delegate from Georgia, Henry M.

Turner, followed Ingersoll,

giving a poor speech which provoked the

laughter of the hall a half dozen

times. He did not stop until the

audience drowned him out with cries of

"time, time, you've said

enough," and the chairman told him he had better

make room for others. He yielded,

smiling and said "Lord bless you--I'se

got a dozen good points I could make

yet."16 General Frye of Maine fol-

lowed with a speech seconding the

nomination of Blaine. New York was

called. Stewart L. Woodford arose and

delivered a masterful speech nom-

inating Senator Conkling. He gave Blaine

a cruel stab by satirizing his re-

cent illness: ". . . that the God

of all life would spare James G. Blaine; and

today, with the most loving of his

friends, New York congratulates him that

his strength is renewed, and his health

so fully restored."17

Then Ohio was called, and Governor

Edward F. Noyes in his rich sono-

rous voice nominated Governor Hayes,

stressing his candidate's war record,

financial independence, political

experience, and especially three successive

gubernatorial victories over prominent

Ohio Democrats, each one consid-

|

ered an aspirant for the presidency. In a potent phrase designed to counter Ingersoll's reference to Blaine's "bloody shirt" oratory, Noyes char- acterized Hayes as "a man who, during dark and stormy days of the rebellion, when those who are invincible in peace and invisible in battle were ut- tering brave words to cheer their neighbors on, himself in the fore-front of battle, followed by his leaders and his flag until the authority of our gov- ernment was reestablished."18 Noyes made an effective speech which was generously applauded. The greatest acclaim of the day, however, had fol- lowed Ingersoll's speech nominating Blaine, and second to that the speech of Harlan nominating Bristow. Governor Hartranft was nominated by Representative Linn Bartholomew of Pennsylvania who made the amaz- ing declaration that the other nom- inees possessed great intellectual su- periority over his candidate, but that Hartranft knew "enough to know that he does not know everything, and is willing to take and to follow good, sound, wholesome advice"!19 Since there were no other candi- dates, the roll call of states ceased, and one of the Morton managers, Will Cumbach, made a motion to adjourn. This was yelled down by the Blaine faction. One of the Conkling men, Samuel S. Edick, then made a motion for an informal ballot (not binding upon the convention, but which would should the relative strength of the several candidates) to be followed by immediate adjournment until 10 A.M. Friday. Blaine supporters overpow- ered this motion too. William P. Frye of Maine, inquired if the hall could be lighted, and permanent chairman Edward McPherson replied: "I de- sire to say for the information of the |

|

|

|

104 OHIO HISTORY convention, that I am informed that the gas lights of this hall are in such condition that they cannot safely be lighted."20 The motion to adjourn until 10 o'clock Friday morning was renewed and carried by a small ma- jority at 5:15 P. M. The opposition to Blaine had gained another night in which to work, and the press got in a few more urgent protests against his nomination while the supporters of Morton, Conkling, Bristow, and Hayes had an op- portunity to adjust matters among themselves and settle on a plan of ac- tion. Between ten and eleven o'clock that evening Hayes received three telegrams. James M. Comly wired: Blaine opposed adjournment gave way to evident wishes of Conven- tion on pretext that Hall had no gas evening session Blaine prestige clouded other Candidates hopeful Ohio extremely confident Many over- tures some from Blaine delegation.21 The second dispatch from his son Webb read: "Governor Noyes instructs me to say that the Combinations are very favorable."22 A third message came from E. Croxsey of the New York Times: "Chances ten to one that Blaine is beaten and that you get the nomination everybody is ready now to beat Blaine and it can't be done on Conkling, Morton or Bristow."23 It was conceded then among the anti-Blaine forces during the night of June 15 that neither Morton, Conkling, Hartranft, nor Jewell could win; that the lot if not to Bristow must fall to Hayes or "the Great Unknown," possibly Secretary of State Hamilton Fish or Representative Elihu Wash- burne of Illinois. Jewell was to be withdrawn after the first complimentary ballot. Morton's supporters agreed to withdraw his name after two or three ballots, if it was demonstrated that their favorite could not win, and then, presumably, they would cast their solid vote for Bristow. The Conkling men preferred Hayes to Bristow, but would support either in preference to Blaine. It was expected that a large majority of the southern delegates would vote for Bristow as soon as Conkling and Morton were withdrawn. At the same time, it was believed that Blaine could not attain a majority until the weakness of the other leading candidates was demonstrated, and that then would be time enough to consider Hayes or someone else. The balloting proceeded toward the magic number of 379 as follows:24 |

HAYES NOMINATION for the PRESIDENCY 105

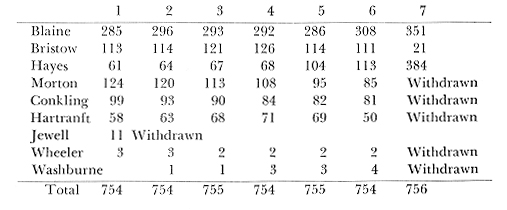

An analysis of the vote shows that the

support of Morton and Conkling

dwindled steadily from the very start.

Blaine gained fourteen and lost three

votes on the second ballot, for a net

gain of eleven or 296 total, and re-

mained relatively static on the third

and fourth ballots gaining six new

votes but losing ten for a net gain

through four ballots of only seven votes.

His managers succeeded in offsetting a

loss of six votes to Bristow and

three to Hayes by picking up eleven of

Morton's original votes. Conkling's

net loss of fifteen votes over the first

four ballots accrued principally to

Hartranft although he lost a few each to

Blaine, Bristow, and Morton. Only

Hartranft, Hayes, and Bristow gained

steadily through the first four bal-

lots, and Bristow actually stood higher

at the end of the fourth ballot than

any other candidate except Blaine. On

this ballot Michigan cast eleven

votes for Bristow while Morton lost

sixteen votes and it was evident his

delegate strength was slipping away. On

the fifth ballot Indiana ought

properly to have withdrawn Morton and

cast her entire thirty votes for

Bristow; Michigan might then have cast

her twenty-two votes for him. His

support then would have increased so

rapidly that he undoubtedly would

have combined all straggling votes and

won the nomination on the sixth

ballot. But the Morton men, acting under

advice from Washington, still

clung to their candidate. As Bristow

gained nothing from any other source,

Michigan decided to switch to Hayes on

the fifth ballot. The chairman an-

nounced: "There is a man in this

section of the country who has beaten

in succession three Democratic

candidates for President in his own state,

and we want to give him a chance to beat

another Democratic candidate for

the Presidency in the broader field of

the United States. Michigan there-

fore casts her twenty-two votes for

Rutherford B. Hayes of Ohio!"25 It

had the effect to send Hayes stock up at

once. North Carolina gave him

eleven votes more, and he gained

scattered support from other states, enough

to boost his strength above 100. Nine of

the North Carolina votes were

transferred directly from Blaine to Hayes.

This depressed Blaine stock and

left him but 286 votes, the lowest

number since the first ballot.

A few days after the convention General

Harlan, leader of the Kentucky

delegation, in a letter to Bristow,

wrote his explanation of the turning

point:

The action of the Michigan delegation in

consolidating its vote for

Hayes on the fifth ballot caused a

stampede in our ranks. . . The union

of that delegation on Hayes was a

surprise to us, and as soon as it was

done I felt that our cause was hopeless.

The failure of the Indiana dele-

gation to change to you on the fifth

ballot induced the Michigan folks

to make the break to Hayes.26

William A. Howard, chairman of the

Michigan delegation, in turn, wrote

to Hayes, explaining why his state voted

for Hayes on the fifth ballot in-

stead of Bristow:

On the 4th ballot 10 had voted for

Bristow 5 for Hayes and 7 for

Blaine. All were admirers of Blaine but

believing his nomination

would force upon the party a defensive

campaign & perhaps defeat we

106 OHIO HISTORY

felt bound to prevent his nomination.

The 5th ballot commenced and

13 win [went] for Bristow 5 for Hayes

& 4 for Blaine. It was certain

that Conklin & Morton must soon be

withdrawn & if the Bristow &

Hayes strength could be united &

draw to itself the greater part of the

Conklin & Morton vote it would

defeat Blaine. So I told the delega-

tion if they would unite & throw the

vote solid & adhere firmly we

could make a nomination & perhaps

save the party from defeat. The

Bristow men said unite on him, the

minority ought to yield to ma-

jority &C. In the absence of facts

we were obliged to rely on the sup-

posed logic of the situation. I thought

the two N.Y. delegates must have

exasperated the other 68 by the

persistency with which they had ad-

vocated the nomination of Bristow even

refusing to join in a harmless

complimentary vote for Conklin. I said

if we strike for Bristow we

shall fail for want of New York votes.

It is not in human nature while

exasperated & heated that they, the

68 should take the candidate of

the two. If we strike for Hayes we shall

win. They reluctantly yielded

--the last man after I was on my

crutches to announce the vote.27

People in the galleries and the

supporters of other prominent candidates

now began to count Blaine out of the

race, supposing he had reached his

greatest strength and therefore there

was no serious effort to continue sup-

porting an opposition candidate in the

sixth ballot. Hayes gained a few

more votes from Illinois, Iowa, Texas,

Tennessee, Virginia, and West Vir-

ginia, some of them being transferred

from Bristow, and came out two

ahead of Bristow on this ballot.

Meanwhile, North Carolina, not satisfied

with the slow progress Hayes

was making and believing after all that

Blaine was destined to win, took

twelve votes from Hayes and cast them

for Blaine. This produced great

cheering made louder when Pennsylvania

cast fourteen votes for Blaine.

South Carolina then increased her votes

for Blaine from five to ten. With

308 votes on this ballot, it was

apparent from the way the Blaine people be-

gan to move about among the southern

delegates plus the confusion among

the Pennsylvania delegation, that a big

push would be made on the next

ballot to nominate Blaine, and that the

opposition must combine now or

never.

The Indiana and Kentucky delegates

consulted earnestly together; Massa-

chusetts and New York retired for

consultation. When the seventh ballot

started, everyone knew the end was near.

Blaine gained one vote from Ala-

bama and eleven votes from Arkansas.

California gave him sixteen, whereas

she had given him only six before. And

so he kept gaining from every

state, until it seemed as though nothing

could stop him. Every new gain

was cheered wildly by his supporters.

When Indiana was reached, Blaine

had gained thirty-two votes. Amid

intense excitement, Indiana was called

and chairman Will Cumbach walked slowly

up to the platform. In a pa-

thetic and dignified speech, he withdrew

the name of Morton, thanked tile

convention for the noble support they

had given him, and announced In-

diana's vote as twenty-five for

Rutherford B. Hayes and five for Benjamin

H. Bristow. At this point the

anti-Blaine forces began shouting. The people

HAYES NOMINATION for the PRESIDENCY 107

in the galleries rose to their feet,

swung hats and handkerchiefs and gave

three long rounds of applause. Iowa

delivered her twenty-two votes for

Blaine as before. Kentucky was called.

General Harlan arose and walked

to the podium. He stood there, his lips

trembling with emotion, waiting for

the storm of applause to be hushed, and

then spoke grandly. He thanked

the convention for the support they had

given Colonel Bristow, and the

thanks of Kentucky were especially due

to those men of Massachusetts and

Vermont, who when it was whispered

throughout the length and breadth

of the land that Benjamin H. Bristow was

not to be president because he

was born and reared in the South, had

come forward and said they were

satisfied that a Kentuckian could be

loyal. Thereupon he withdrew Bris-

tow's name and cast Kentucky's entire

vote for Rutherford B. Hayes. Wild

and tumultuous applause broke loose.

Louisiana, which had given Blaine only

six votes, now cast fourteen for

him. This gave the Blaine forces another

chance to cheer; and so the con-

test wavered. When Massachusetts cast

twenty-one for Hayes, Michigan

twenty-two, and Mississippi sixteen, the

applause was deafening. When New

York was called, there was a lull of

anxious expectation. Governor Theo-

dore M. Pomeroy advanced to the platform

and amid perfect silence, said:

"To indicate that New York is in

favor of unity and victory, she casts sixty-

one votes for Rutherford B. Hayes,"

but the remainder of his sentence,

"and nine votes for James G.

Blaine," was drowned out.28 North Carolina

again swung over to Hayes and cast her

solid vote of twenty for him. Ohio

followed as usual with forty-four, but

now the vote seemed to count much

more, and the Exposition Hall rang with

the cheers of the united opposi-

tion.

When Pennsylvania was called, there was

another lull of expectation.

Blaine could still win with a bloc vote

here. Don Cameron, the young Sec-

retary of War, mounted a chair in front

of his delegation, withdrew the

name of Hartranft, and announced thirty

votes for Blaine and twenty-eight

for Hayes, which made both sides cheer

long and loud. South Carolina

divided evenly, Texas gave all but one vote

to Hayes. Tennessee added

eighteen more for Hayes, and Vermont her

entire ten. Before the terri-

tories were reached some of the

reporters who were quick at figures dis-

covered Hayes had a majority, jumped up

in their seats, swung their hats

and shouted "Hayes! Hayes!"

The territories were called amid great con-

fusion and the chairmen of all but

Montana and Wyoming doggedly cast

their votes for James G. Blaine though

they knew their man was beaten.

The tally showed Blaine 351; Bristow 21;

Hayes 384.

Cheering lasted about fifteen or twenty

minutes. The nomination of

Hayes was made unanimous, and the

convention proceeded to nominate a

vice-president. The names of William A.

Wheeler and Stewart L. Wood-

ford of New York, Joseph M. Hawley and

Marshall Jewell of Connecticut,

and Frederick T. Frelinghuysen of New

Jersey, were presented. Early in

the balloting it became evident that

Wheeler was the favorite. All the

Blaine men voted for him, and Woodford

withdrew his own name before

New York was reached. New York cast her

solid vote for Wheeler, Penn-

108

OHIO HISTORY

sylvania

voted for Frelinghuysen, Jewell was withdrawn, and before the

first ballot

was completed, a motion to make Wheeler's nomination un-

animous

carried by an overwhelming shout.

The outcome

of the convention did not surprise William Henry Smith,

general

agent for the Western Associated Press and the canniest of all the

Hayes

managers. Smith not only guided the Hayes movement forward but

had

confidently predicted the ticket of Hayes and Wheeler nearly five

months

before the national convention assembled in Cincinnati, certainly

one of the

more remarkable forecasts in American political history. Hayes

acknowledged

his mentor's role:

Your

sagacity in this matter, take it all in all, is beyond that of any

other friend

. . . And the way it was to come you told to a letter. Others

of much

sagacity have written, but nothing like yours. Not merely saga-

city

either--how much you did to fulfill the prediction I shall perhaps

never know,

but I know it was very potent.29

A state by

state re-examination of the seven ballots for the 1876 Repub-

lican

presidential nomination reveals even more clearly how narrow a vic-

tory Hayes

had won, and the remarkable race made by Blaine against the

field not

only as the front runner on six ballots but also burdened by the

doubts

raised before and during the convention concerning the Mulligan

letters and

his illness. Despite his handicaps Blaine might have been nom-

inated if

Hayes had not barely garnered enough votes on the seventh ballot.

Composite

vote figures for all seven ballots by candidates demonstrate

Blaine's

great appeal:

Composite

Vote Analysis

Maximum

support over Maximum support on a

seven

ballots single ballot

Blaine 398 351

Bristow 149 126

Hayes 388 384

Morton 137 124

Conkling 105 99

Hartranft 80 71

Jewel 11 11

Wheeler 3 3

Washburne 4 4

These

figures show that Blaine failed to hold forty-seven delegates who

had voted

for him on earlier ballots. The North Carolina delegation with

twenty votes

which he controlled on five of his first six ballots deserted him

on the

crucial seventh poll. A floor fight over the unit rule during the sec-

ond ballot

also boomeranged on Blaine's managers. When Pennsylvania was

called and

her vote given as fifty-eight for Hartranft, it was challenged by

HAYES NOMINATION for the PRESIDENCY 109

one of the delegates who stated that he

and another delegate wanted to

vote for Blaine. They subsequently were

joined by two others. McPherson,

the convention chairman and loyal to

Blaine, ruled that "it is the right of

any and of every member equally, to vote

his sentiments in this conven-

tion."30 An appeal to this decision

was put to the convention and the chair-

man's decision was declared sustained.

Thereupon a motion to reconsider

the motion upholding the decision of the

chair carried 381 to 359. On the

roll call, the decision of the

convention chairman was again sustained 395

to 353. At the time, the vote was hailed

as a victory for Blaine. However,

on the seventh ballot, when Pennsylvania

divided thirty for Blaine and

twenty-eight for Hayes, it was a major

factor in defeating him. As J. C. Lee

explained later to Hayes: "Had not

McPherson ruled as he did on the Pa.

question, or had the Convention reversed

his decision, the 28 votes for you

in Pa. would have been carried by the 30

Blaine votes to Blaine, and that

would have given Blaine 379, just enough

to nominate him & more to

spare."31 In raising the

unit rule question the Blaine faction won a minor

victory that paved the way to ultimate

defeat.

Hayes, on the other hand, won the

nomination because his managers

were shrewd enough to let Bristow's

supporters make the fight against

Blaine, and after it was over, they gathered

in the victory. Furthermore, by

concentrating on second choice support

for Hayes, he became the only

candidate to gain strength on every

ballot and take votes away from each

of his rivals. Hayes in the end received

most of the Bristow and Conkling

support, about one-half of the Morton

and Hartranft votes, and even took

votes away from Blaine. Over all seven

ballots Hayes lost only four delegates

who had on some ballot voted for him,

but even with this remarkable

holding power he had only five votes to

spare. In retrospect, the shift of

Michigan away from Blaine and Bristow to

Hayes may be considered the

decisive turning point in the balloting.

A. B. Watson, a member of the

Michigan delegation, later revealed how

when Hayes was nominated "the

Ohio delegation rushed forward, and

embracing the veteran chairman of

the Michigan delegation, exclaimed 'You

have nominated the next Presi-

dent.' "32 John C. Lee of

Ohio conceded: "I must not forget to say that in

Gov. Bagley and Wm. A. Howard of

Michigan we formed original and most

effective friends. They had taken in the

situation much more completely

than many, yes, 9/10 of our own

delegates."33

William Henry Smith praised the

leadership of Noyes as:

The one who above all others deserves

praise. It was something to

have noble men in the Ohio delegation:

and to have such long-time

friends and new friends as Stephenson,

Comly, Gano, Thrall, Morrill,

McLaughlin, King, Bickham, Wykoff, Foos,

Mitchell, Buckland, Kess-

ler, Nash, etc. of the old Literary Club

and later associations, to whom

delegates from abroad could go for

personal information. But it was of

first importance to have a leader as

Edward F. Noyes. Better manage-

ment I never saw. It was able,

judicious, untiring, unselfish, inspiring,

adroit. If there was a mistake made I

did not discover it. The disloyalty

that attempted on the part of one or two

well-known Ohioans in the

110 OHIO HISTORY

interest of Blaine, was anticipated and

cleverly disarmed. The General

seemingly never slept. His eyes were

everywhere and discipline was

preserved with as much vigor as on the

field of battle. He compre-

hended fully the situation and inspired

the confidence of the men of

New England, New York, Kentucky, and

Indiana. His personal friend-

ship for Gens. Bristow and Harlan did

not as some mischief makers

asserted would be the case, lessen his

loyalty to you, but served an im-

portant purpose at a critical

moment."34

As for Bristow, if, in a square fight

with Blaine, on the seventh ballot

the attempt had been made to nominate

him it would undoubtedly have

failed, as the Ohio delegation would

either have held firm for Hayes, or

broken up so as to give Blaine sixteen

votes. Blaine also would have picked

up ten more in Pennsylvania, some in New

York, and some scalawags in

southern delegations. Harlan also later

confessed to W. Q. Gresham that

he had made a deal with the Hayes men.

Hayes carried out his part of the

bargain by placing Harlan on the Supreme

Court in 1877. Bristow, piqued

over failure to receive the justiceship

for himself, and feeling that Harlan

had betrayed him, never spoke to Harlan

after the latter's appointment.35

Two weeks after the Republican

convention the Democrats met in St.

Louis and chose Governor Samuel J.

Tilden of New York as their standard

bearer. Tilden, a bachelor and

multimillionaire, helped expose and prose-

cute the notorious Tweed Ring of New

York City. This activity aided in

his election to the governorship in 1874

where he further enhanced his

reputation as a reformer. Aloof and shy,

constantly brooding over his rather

poor health, Tilden devoted many hours

to his fine library. His will later

provided funds to establish the now

famous New York Public Library.

Thomas A. Hendricks of Indiana, second

in the balloting to Tilden at St.

Louis, received the vice-presidential

nomination by acclamation. They made

a strange pair with Tilden supporting

the hard money views of the eastern

wing of the party, and Hendricks

advocating the greenback position of the

western Democrats.

The stage was set for the most

extraordinary presidential election in

American history.

THE AUTHOR: Kenneth E. Davison is

Professor of History and chairman of the

American Studies program at Heidelberg

College.