Ohio History Journal

MICHAEL J. DEVINE

The Historical Paintings

of William Henry Powell

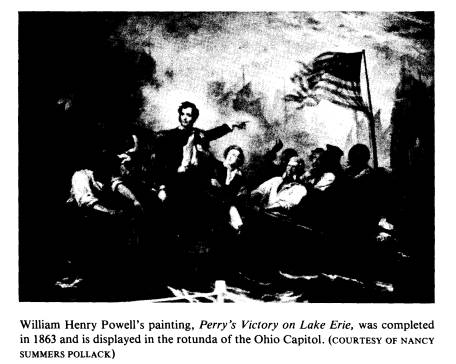

In 1865 the Ohio General Assembly

commissioned William Henry

Powell to paint a large historic picture

depicting the heroic naval victory

of Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry and his

men over the British in

the Battle of Lake Erie in 1813. A

former resident of Cincinnati, Powell

had won fame in the eastern urban

centers of the United States as well

as European capitals, and his majestic

"Perry's Victory" hung in

Ohio's capitol for over one hundred

years as one of the state's most

valuable art treasures.' However, from

its inception the painting was

a controversial item. Questions arose

concerning what seemed to be an

excessive payment for the work, critics

attacked the quality of the

painting and its historical accuracy,

and public confusion developed

when the artist painted an almost

identical version of "Perry's Victory"

for the United States Capitol. This

study of William Henry Powell

and his work seeks to detail Powell's

remarkable career as an artist

of historical scenes, examine the

politics surrounding the commissioning

of Powell by political leaders conscious

of the public's growing taste

for historical art, and assess Powell's

works and the public reactions

they generated.

Powell was the product of an unusual,

brilliant flowering of portrait

and landscape artists in frontier

Cincinnati which included such diverse

talents as Thomas Worthington

Whittridge, James H. Beard, Lilly

Martin Spencer, Abraham G. D. Tuthill,

and John P. Frankenstein.

Born in New York on February 14, 1823,

Powell moved to Cincinnati

with his family at the age of seven, and

he soon demonstrated a

Michael J. Devine is Executive Director

of the Greater Cincinnati Consortium of

Colleges and Universities.

1. "Perry's Victory" was

removed from the Capitol while the rotunda was being

painted in 1967 and placed in storage by

the Department of Public Works. Recently,

however, the Ohio Historical Society has

had the painting restored with funds provided

by the Ohio American Revolution

Bicentennial Advisory Commission and it is once

again on display in the Capitol. Two

companion paintings, "The Wright Brothers"

painted by Dwight Mutchler (1959) and

"Edison" by Howard Chandler Christy (1950),

have been locked in storage since 1967

in the care of the Ohio Historical Society.

Christy's "Greenville Treaty"

(1945) is still on public display in the statehouse. See

report of Charles Pratt to Ohio

Historical Society Board of Trustees, July 8, 1967,

Ohio Historical Society Records.

66 OHIO

HISTORY

remarkable talent for drawing. In 1835,

at a time when the city was

experiencing an awakening as a cultural

center, young Powell's portrait

of the legendary Scottish chieftain

Rodrich Dhru attracted the attention

of Nicholas Longworth, Cincinnati's

leading patron of the arts, who

provided Powell with financial

assistance and encouragement to seek

the best training available, which at

that time meant study in the cities

of America's eastern seaboard and the

cultural centers of Europe.

Longworth also provided Powell with the

appropriate letters of intro-

duction to allow him entry into the

eastern academies.2 Although

painting was by the 1840s becoming a

respected profession in midwestern

cities such as Cincinnati, for an

aspiring artist with Powell's talent

the major cities of the East and Europe

were the only places which

offered the training, recognition, and

financial rewards which would

allow a painter to devote his full time

to his profession. Thus Powell's

initial recogniton came in the usual

manner-as a portrait painter; how-

ever, he displayed more versatility

than his contemporaries in Ohio and

developed into a landscape and

historical painter, an increasingly

popular art form with an American

public demanding higher standards

from its artists.3

In 1837 Powell entered the New York

studio of Henry Inman, who

was to be his teacher and mentor for many

years. By the age of twenty-

five Powell was already a popular and

promising artist with a consid-

erable reputation. In 1844 he visited

Europe to further his studies in

Florence and Rome.4 Upon his

return to the United States Powell

secured, through the influence of his

friends and considerable good

fortune, a major commission from the

United States Congress which

had a dramatic effect upon his career.

In 1847 Powell won out over sixty

competitors, including Samuel

F. B. Morse, and received a commission

to paint a historical scene

for the remaining vacant panel in the

Rotunda of the United States

Capitol. This was a major coup for a

relatively young and unknown

artist. Powell's selection raised

questions in art circles, as he had no

claim to the job in terms of rank or

age. Apparently, consideration

of his early residence in the populous

state of Ohio was an important

2. Art Journal, (1879), 351; New

York Tribune, October 7,1879; Henry B.

Tuckerman, Book of Artists (New

York, 1867), 458-59. Emma J. Hollingsworth,

ed. Capitol Guide Catalogue of the

Paintings and Portraits of the Governors of Ohio

(Columbus, 1910).

3. Donald MacKenzie, "Early Ohio

Painters: Cincinnati, 1830-1850," Ohio History,

73 (Spring, 1964), 111-18, 131-32;

Eugene Roseboom, The History of the State of

Ohio, IV, The Civil War Years, 1850-1873 (Columbus,

1944), 165.

4. Art Journal, (1879), 351; Fredrick A. Gutheim, The Federal City (Washington,

D.C., 1976), 125.

William Henry Powell

67

political factor in the selection

process, but Powell also had the backing

of influential friends in New York.5

Among those supporting Powell's

selection were prominent literary

figures, including the author Wash-

ington Irving, whose biography of

Christopher Columbus had inspired

an earlier painting by Powell depicting

Columbus before the Council

of Ecclesiastics at Salamanca. In a

letter to the library committee of

Congress, Irving wrote that Powell

"possesses genius and talent of

superior order and ... he is destined to

win great triumphs for

American art."6

Choosing for his theme "The

Discovery of the Mississippi by

DeSoto," Powell used his generous

commission of twelve thousand

dollars to return to Europe where he

worked on his assignment and

furthered his studies in Paris under

European masters, as was the

practice for American artists at this

time. While in Europe, Powell

became popular at the court of Napolean

III and befriended leading

French intellectuals such as Alexander

Dumas, Lamartine, and the

Duke de Morny. The emperor Napoleon III

approved of Powell's

work, as did most French critics, and

allowed the American painter

to use the horses in his stable as

models. After almost seven years in

France, Powell returned to the United

States with his painting which he

displayed in New York, Philadelphia, and

Baltimore on his way to the

capital, causing one Washington newspaper

to observe that the painting

would be "second hand" by the

time it arrived.7 However, once

unveiled before a large crowd in the

Rotunda of the United States

Capitol, the huge melodramatic painting

received a generally enthusiastic

reception. One witness observed,

"nobody could deny the fact that it

was a great success. ... we can already

pronounce that the composition

is one of the most eloquent pages of

descriptive history we possess."8

5. Henry Inman, Powell's teacher, seemed

at one time certain to receive the

coveted commission, however his ill

health and eventual death prevented him from doing

the final panel. Charles E. Fairman, Art

and Articles of the Capitol of the United

States of America. U.S. Congress, Senate Document No. 95, 69th Congress,

1st Session

(1927), 78, 105-07, 126-27, 158-59. E.

P. Richardson, Painting in America: The

Story of 450 Years, (New York, 1956), 201-02; also see Tuckerman, 458. The

story of

congressional interest in providing art

for the Capitol, which began in 1836, is detailed

in George R. Nielson, "Painting and

Politics in Jacksonian America," Capitol Studies

(Spring, 1972), 87-92.

6. Irving to Library Committee of

Congress, January 7, 1847; Henry Brevoort to

Gentlemen, January 7, 1847, Architect of

the U.S. Capitol, Records, Washington, D.C.

Hereinafter referred to as U.S. Capitol

Architect, Records. Washington Daily Intelligence,

January 20, 1847.

7. Washington Sentinel, February

1, 1855.

8. Washington Sentinel, February

17, 1855. The elaborate paintings in the Capital

Rotunda provided art critics with ample

opportunities for ridicule, and it became almost

a tradition for sophisticated observers

to criticize the Capitol's art work. One critic noted

an "over-crowded canvas" in

Powell's "DeSoto" and observed that the horses were

68 OHIO HISTORY

The prestige of having his work

displayed alongside such famous

American paintings as John Trumble's

"Declaration of Independence"

and "Surrender of Lord

Cornwallis," Robert Weir's "Embarkation of

the Pilgrims," and John Vanderlyn's

"Landing of Columbus" made

Powell a leader among his contemporaries

in the field of historical

painting. It was therefore not

surprising that his home state of Ohio

would seek to enlist his talents to help

decorate the newly completed

State Capitol in Columbus.

The year following the exhibition of

"DeSoto Discovering the Mis-

sissippi," Powell received a

commission from the Ohio General Assem-

bly to render a painting of Commodore

Oliver Hazard Perry's decisive

victory over the British on Lake Erie.

The commission specified that

the painting, to be placed in the

Rotunda of the Capitol, should be

a minimum of twelve feet by sixteen feet

in size and "sufficiently

elaborate to convey full and truthful

history of that great battle."

The commission also specified that the

work was to be completed

within five years at a cost of "not

more than five thousand dollars"-

a rather modest fee, considering Powell

received twelve thousand

dollars for "DeSoto."9

To complete the painting, which would be

entitled "Perry's Victory,"

Powell worked in his studio in New York

City, and at the Brooklyn

Navy Yard. He also traveled to Rhode

Island, Perry's home state, to.

study naval vessels of the type used on

the Great Lakes during the

War of 1812. The meticulous research and

careful painting took longer

than Powell had anticipated. Meanwhile,

he supplemented his income

by doing portraits, including that of

Washington Irving which was

unveiled in April 1860 at the New York

Academy of Music amidst

great applause. This portrait,

commissioned by the New York Historical

Society to commemorate the 75th

anniversary of the author's birth,

was perhaps Powell's most successful

portrait. 10

Finally, in January 1865, almost nine

years after his original com-

mission, Powell was prepared to deliver

his finished painting to Ohio.

However, after temporarily exhibiting

the painting in Rhode Island,

Powell brought his completed painting

not to Columbus, but to

Washington, where, with the assistance

of the architect of the United

States Capitol, he temporarily exhibited

"Perry's Victory" in the

"too small and badly drawn."

George A. Townsend, Washington, Outside and Inside

(Cincinnati, 1873), 750. Also see

Richardson, Painting in America, 133; Joseph R.

Frese, Federal Patronage of Painting to

1860, Capitol Studies (Winter, 1974), 71-76.

9. Ohio General Assembly, House Joint

Resolution (April 17, 1857); Leslie's

Illustrated Newspaper, May 9, 1857, 351.

10. Art Journal(1879), 351.

William Henry Powell

69

Rotunda.11 Powell had two reasons for

taking this action: first, he was

anxious to secure another commission

from the United States Congress

and hoped that the exhibition of

"Perry's Victory" would inspire the

legislators to offer him further

employment; and second, Powell was

in the process of renegotiating his fee

with the Ohio General Assembly

and apparently wanted the Ohioans to

believe that he would sell his

painting to the United States Congress

or another buyer unless the

original commission of five thousand

dollars was increased.

In March 1865, while "Perry's

Victory" was being displayed in the

United States Capitol, Powell wrote to

the Ohio General Assembly and

claimed to have done a more elaborate

painting than was originally

requested. The artist noted that he was

faced with cost increases and

appealed for "generosity and

justice" in asking for a payment of fifteen

thousand dollars-three times the amount

originally appropriated!12

A Select Committee of members of the

Ohio General Assembly

appointed to examine the painting's

quality journeyed to Washington

to view the work and evaluate its

artistic merits. Whether the members

of the Select Committee were chosen for

their politics or aesthetic

judgment, they nevertheless reported

unanimously that they found "the

design and execution of the work

tendered to the State to be superior

to that contemplated when the picture was

ordered. . ." The committee's

report also noted that the artist was

"a distinguished citizen of Ohio"

who had spent considerable sums of his

own funds, and therefore

recommend acceptance of the painting at

the figure requested by the

artist. (Two members of the committee

dissented from this recom-

mendation, considering the artist's

demands exorbitant while agreeing

that the painting was indeed of high

quality.)13 Ultimately, the Ohio

Senate voted to instruct the Governor

to purchase the painting for ten

thousand dollars and have it installed

in the Rotunda.14 Meanwhile,

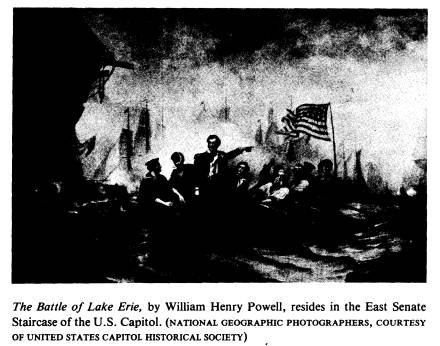

Powell received from Congress a

commission of twenty-five thousand

dollars to paint a second version of a

naval scene, to hang in the east

staircase of the Senate wing in the

United States Capitol.15

11. "Journal of B. (Benjamin) B.

(Blake) French," Library of Congress, Manuscripts

Division; New York Times, October

14, 1864. A note attached to Powell's petition

stated "The painting referred to we

have seen, and concur in the universal opinion of

its excellence." Among the signers

of this statement were Ohio's John Sherman,

Benjamin F. Wade, Salmon P. Chase and

William Dennison.

12. William Powell to Ohio General

Assembly, March 7, 1865, Ohio Historical

Society Archives, P.A., 236.

13. "Report of the Select

Committee," Ohio General Assembly. Senate Journal, 1865,

412.

14. Ohio Senate Journal, 56th

General Assembly, vol. LXI (1865), 507; Ohio State

Journal, April 12, 1865.

15. United States Senate, Document No.

60, 59th Congress, 1st Session, No. 3849,

vol. 2.

|

70 OHIO HISTORY |

|

|

|

Finally on March 30, 1865, the "Perry's Victory" was placed on display and Ohioans had a chance to judge the painting's merits for themselves. Already praised by members of the Select Committee, the painting was also praised by art critics from eastern cities who predicted that "Perry's Victory" would add to the artist's reputation. One observer remarked that the painting would make an admirable pendent to Emanuel Leutze's immensely popular "Washington Crossing the Delaware," while a newspaper in Perry's home state observed that "with a little selfishness that is natural, we would rather keep the picture in Rhode Island than let it go to either Ohio or Washington." 16 While there appeared to be general agreement that the work was of high quality and well worth the expense, criticism of both the painting's quality and its price quickly arose. Perhaps never in the state's history has a work of art generated such heated controversy. Among the comments printed in the Ohio State Journal soon after the painting was displayed in Columbus were the following: 16. Ohio State Journal, March 30 and 31, April 12, 1865; New York Times, October 14, 1864; New York Evening Post, August 30, 1864; Providence Journal, September 5, 1864. A typed summation of press opinion regarding "Perry's Victory" is found in Ohio Historical Society Archives, P.A., 236. |

|

William Henry Powell 71 |

|

|

|

We join ... in remarking that Mr. Powell, historical painter, etc., has had another streak of bad fortune.-Years ago, Congress let him paint a huge picture for the Rotunda of the Capitol, purporting to represent DeSoto's discovery of the Mississippi, which still remains an eyesore to all visitors who have a true appreciation of historical art. As if this was not enough, Congress has just passed a resolution to pay Mr. Powell $25,000 for another historical picture. Poor Mr. Powell! It was bad enough to have one utterly worthless picture in the national capitol, without adding another glaring evidence of his artistic incapacity. Mr. Powell, we are glad to see, had a few true friends in the Senate who endeavored to spare his reputation this additional burden... Mr. [Senator Charles] Sumner's opposition was overruled.... A very excellent proviso, also offered by Mr. Sumner, that the painting should not represent a victory over our fellow citizens was not adopted, it being understood, we suppose that Mr. Powell will elaborate into a large painting the sketch of "Perry's Victory" which was shown in Washington as evidence of his artistic ability. 17 Another Washington critic, anonymously calling himself "a careful observer," wrote: I ... was a great deal disturbed by the passage of the resolution to pay Mr. Powell $25,000, for a painting of some naval subject. We have for many years been laughed at, by cultivated minds, for purchasing of this same artist the 17. Ohio State Journal, April 12, 1865. |

72 OHIO HISTORY

so-called "Discovery of the

Mississippi by DeSoto." It is beneath criticism.

Its total want of a knowledge of the

subject, its wretched coloring and bad

drawing, illustrate historically the crude condition of

Congress, and makes a

beautiful painting to cut up; but I will

not waste time in useless comments.

Lately, however, Mr. Powell who admits

that DeSoto was bad business, has

hung up in the Rotunda of the Capitol a

painting he calls "Perry's Victory,"

and claims on this showing to have

improved. I am sorry to say that the claim

is not tenable. The artist has but one

point to make, and that was a

representation of Perry, as he passed in

an open boat from his disabled vessel

to a fresh one. He has failed here as he

failed with DeSoto . . the painting

is a mean, distasteful, and abominable

from its utter poverty.... The artist

unable to understand the simplicity of

true greatness, drops the work to take

up the theatrical. His Perry is the

Perry of the stage.... Nor has the Artist

improved in other respects. The water is

not water. If that is a correct

representation of the condition of Lake

Erie, Perry could have walked from

one vessel to another.

.... This painting belongs to Ohio. Poor

Ohio pays a thousand dollars for

it, Congress sees that and goes

twenty-four thousand better. Senator Sherman

[John Sherman of Ohio], to use a flash

phrase, 'didn't see it,' and used his

efforts to defeat the barbarous

resolution. 18

Not all the criticism focused on the

quality of the art. At least one

Ohio politician loudly voiced his

consternation that a figure of a black

man, depicted at Perry's side, would

enjoy a prominent place in the

statehouse. His remarks were overheard

and recorded by a reporter for

the conservative Ohio Statesman, which

then printed the politician's

crude comment. This incident lead to a

sharp rebuke by the Statesman's

chief competitor, the Journal, which

editorialized as follows:

$10,000 for a Nigger. A senator

yesterday furnished considerable merriment to

persons in the Rotunda, by passing a

remark he made touching the great

painting of Mr. Powell, representing

Commodore Perry's victory on Lake

Erie. In 1857, we believe, the

Legislature made an appropriation of $5,000 to pay

for this painting but in consideration

of the inflated prices at the time it was

painted, Mr. Powell feels compelled to

ask $15,000 for it. The Senator referred

to glanced at the picture, and described

a negro in the background, and

remarked, "Well ten thousand

dollars for a nigger." The crowd at once saw

the point, and enjoyed the joke

exceedingly.-Ohio Statesman.

The foregoing paragraph affords an

admirable illustration of the morals of

the Ohio Statesman. Its

negrophobia blinds it to good taste, common sense,

and historical truth. It exposes the

meanness of its spirit and the paucity of

its information. The historical fact is

that Hannibal, Perry's servant, was taken

into his master's boat at his own urgent

request. We do not hesitate to entertain

a very firm conviction that if the

Editor of the Statesman had been in the

Lake Erie fight, he would have been too

"conservative" to run the gauntlet

of the British fire. A "nigger in

the boat" would have furnished him an

18. Ibid.

William Henry Powell 73

excellent excuse. The Statesman's Senator-extemporized,

we presume-would

have been its editor's bosom friend in

that emergency.19

Much of the controversy about the

painting concerned its historical

accuracy, and despite Powell's careful

research in Rhode Island and the

Brooklyn Naval Yard many critics

disputed minor details in the compo-

sition. A sensitive artist, Powell heard

his critics and sought to have the

correctness of his paintings verified.

Therefore, he must have been

comforted to read a letter he received

from one survivor of the battle

who had viewed the painting while it was

displayed in Washington and

wrote:

I take pleasure in complying with your

request to add my testimony to the

correctness of your likeness of the late

Commodore 0. H. Perry, and portrayed

in your magnificent painting of that

battle. I have no hesitation Sir in

stating that in my opinion you have

given the most striking and life-like

representation of that hero that has

ever appeared on canvas and.... This

painting in all its details with one

exception gives a truthful and vivid

representation of the scene it

portrays.20

Undaunted by his critics, Powell began

work on his second version

of the famous naval engagement, to be

entitled "The Battle of Lake

Erie," and of greater

dimensions-twenty feet by thirty feet-than

"Perry's Victory." Although

the second version was to be considerably

larger than the first, Powell used the

same drawing as his earlier

painting and merely enlarged the

background scenery, a practice not

uncommon in Powell's day.21

In completing "The Battle of Lake

Erie," Powell encountered the

same financial problems and criticisms

he had experienced in painting

and exhibiting "Perry's

Victory." In November, 1871, six years after

having received his commission from

Congress, Powell wrote to

Senator Lot M. Morrill of Maine,

chairman of the Committee on the

Library of Congress, and expressed

concern that the legislator had

neglected Powell's earlier request for

payment. Informing Morrill that

the painting could not be completed for

an opening of the Congressional

session in December, Powell noted "your

disappointment cannot equal

mine, for all my material interests

would be benefitted could that

19. Ohio State Journal, April 1,

1865.

20. The writer did not indicate in this

communication what his "one exception"

was. Usher Parsons to Powell, October

20, 1863, Records, U.S. Capitol Architect.

Parsons had served with Perry as a

surgeon and was noted for giving talks to patriotic

and historical groups on the Battle of Lake Erie.

21. David Lynn, Architect of the

Capitol, to Miss Wenona Merlin, March 24, 1937,

Records, U.S. Capitol Architect.

74 OHIO

HISTORY

be accomplished... but it is not

possible." Claiming that he had

worked continuously for six to eight

hours a day, Powell stated that

"the work grew under my hands, and

I found that I carried out my

assurance to your committee, in which at

the time given I firmly

believed, I must do so by inferior work,

which neither be just to the

government which entrusted to my honor

the best evidence of my

artistic ability, nor to my own

reputation.... I have produced the

best work that I am able to do but at a

much greater cost of time

than I anticipated. That is my loss, and

a bitter loss it is." Stating

that the painting could not be ready

until the following March, Powell

announced that he would stop work

entirely on "The Battle of Lake

Erie" to accept portrait work,

"which will give me a means of

supporting my family." Powell

concluded his letter by writing: "I shall

not willingly deliver the work from my

hands with any of the details

lower in execution than the standard I

have adopted."22 The question

of payment was finally resolved, but it

was not until the spring of

1873 that Powell informed the architect

of the Capitol that "The Battle

of Lake Erie" was ready for framing

and exhibition.23

The second version of Perry's heroic

triumph, painted in the grand

romantic style popular in his time, was

perhaps Powell's best work-at

least the artist himself thought so.24

But once again critics found

imperfections. Henry C. Bispham, a noted

New York art critic, found

the "figure badly drawn and

painted, and in some respects not as

good as DeSoto ... they are too

woodeny." However, Bispham

conceded that the background was

"well painted, composed and

drawn."25 Once again the

art critics were less appreciative than the

general public and their elected

representatives, who found Powell's

historical paintings to their liking.

Powell's rendering of two nearly

identical paintings, while a fairly

common practice in his era, resulted in

great public confusion. Both

enormous paintings were permanently

displayed in public buildings

and for over a century were viewed by

millions of visitors. Also, both

22. Powell to Lot Morrill, November 25,

1871, National Archives, U.S. Library of

Congress, Manuscripts Div., Misc.

Manuscripts, No. 148.

23. Powell to Edward Clark, March 30,

1873, Records, U.S. Capitol Architect.

24. Art Journal(1879), 351.

25. Quoted in Townsend, Washington

Inside and Outside. 749-50. For an interesting

evaluation of Powell's naval scenes, see

Charles Lee Lewis, "Powell's Victory on Lake

Erie," The Capitol Dome (July,

1970), 2-6. Lewis, a naval historian, finds three faults

with the painting: first, Perry carried

over his shoulder his banner "Don't give up the

ship," not the Stars and Stripes,

when he transferred from the Lawrence to the Niagara;

second, Perry and his men appear to be

wearing uniforms of the Civil War period rather

than the War of 1812; and third, Perry's

small boat should have only five occupants

and his little brother Alexander should

not be among them.

|

William Henry Powell 75 |

|

|

|

paintings were frequently copied and reproduced. Confusion was compounded by misinformed guards in the Nation's Capitol and untrained guards in Columbus, who, lacking factual information, often fabricated their own historical narratives. A principal perpetrator of misinformation was Captain Howard F. Kennedy, who for over four decades served as the chief of the Nation's Capitol guides. Kennedy knew Powell personally at the time the painter was working on both "Perry's Victory" and "The Battle of Lake Erie" and the two were frequent companions at taverns in Washington and New York. Kennedy apparently never paid careful attention to factual details, and over time his memory became clouded. A typed transcript of Kennedy's reminiscences of Powell produced in 1911 provided the office of the Capitol Architect with its basic history of the two paintings. Unfortunately, Kennedy incorrectly identified Powell as a native of Oregon and mistakenly believed that "Perry's Victory" was removed from the Capitol in 1865 because the Capitol Architect was dissatisfied with its size and sold it to Ohio only after Powell agreed to paint a larger version.26 Kennedy's erroneous statements were repeated by dozens of Capitol guides to thousands of tourists and by the Office

26. Kennedy to Elliot Woods, Superintendent of U.S. Capitol Building, January 11, 1911, Records, Architect of the U.S. Capitol. |

76 OHIO

HISTORY

of the Architect to publishers and radio

broadcasters. Meanwhile,

groups of Ohio school children were told

by guards that the version

in Ohio, "Perry's Victory,"

had originally been intended for the United

States Capitol, but was rejected because

a black man was depicted in

the same boat with the commodore.27

During the final years of his life

Powell painted nothing to equal

the majestic historical works which hung

in the capitols in Washington

and Columbus. He continued his portrait

painting and maintained an

elegant and expensive social life in New

York, where his parties were

ranked among the most fashionable in

that city. His wife was a woman

of considerable social standing and

frequent visitors to their home

included the wife of Judge Theodore

Roosevelt-the mother of the

future president-,Mrs. John Charles

Fremont, and Mrs. Charles

O'Connor, the estranged wife of the

famous attorney who defended

Jefferson Davis in his trial for

treason. Powell delighted in the opera

and had a considerable reputation as a

music critic. His French and

Italian were flawless and he was often

mistaken as a French citizen

when traveling in Europe. In his final

years his fortune disappeared

and he was weakened by poor health;

however, he continued to work

in his studio until his death in 1879.28

Although the mid-nineteenth century

produced many talented artists

who polished their skills in European

art centers, the art of the period

lacked real greatness. Like their

contemporaries in European academies

with whom they studied, popular American

painters of this era

produced historical scenes featuring

melodramatic, cluttered canvases

of minute portraits. They tended to be

exceptionally sentimental in

portraying their historical subjects and

seemed to appeal to their

young nation's need for psychological

reassurance of American

greatness. Producing romantic works of

unreal beauty, most art-

ists of Powell's day, with the

remarkable exception of Winslow

Homer, tended to ignore the period's

relevant burning issues-the

slavery controversy, Civil War, and

industrial revolution. While the

giant historical paintings of Powell and

his contemporaries were not

highly esteemed by art historians and

critics, they were much appreciated

by a public anxious to view dramatic and

inspiring art in their public

buildings.29

27. David Lynn to Bruce Chapman, Mutual

Broadcasting System, "The Answer

Man Program," October 8, 1942;

Charles E. Fairman, Art Curator, U.S. Capitol,

to Henry Ishman, June 15, 1934;

Memorandum, Judge Earl Hoover of Cleveland,

August 22, 1966, Records, Architect of

the U.S. Capitol.

28. Art Journal(1879), 351.

29. Wendell D. Garrett, "A Century

of Aspiration" in W. Garrett and others, ed.,

The Arts in America: The Nineteenth

Century (New York, 1969), 21, 24-25.

William Henry Powell 77

While not among the great figures in the

history of American art,

Powell is nevertheless significant as an

early example of a highly

successful portrait artist who expanded

his basic skills and produced

more complex and elaborate historical

paintings. The first artist from

Ohio to gain a national reputation and

receive major commissions

from the United States Congress and the

Ohio General Assembly, he

is best remembered for his historical

paintings, particularly his two

massive and dramatic depictions of the

American naval triumph on

Lake Erie. His career is representative

of those nineteenth century

artists who, after gaining local success

as portrait painters, journeyed

to the east coast and Europe to sharpen

their skills for an American

public becoming more sophisticated in

its tastes and beginning to

demand higher standards from its

artists.