Ohio History Journal

|

|

|

NEGRO RIGHTS AND WHITE BACKLASH IN THE CAMPAIGN OF 1920

by RANDOLPH C. DOWNES

I believe in equality before the law. You can't give rights to the white man and deny them to the black man. But while I stand for that great, great principle, I do not mean that the white man and the black man must be forced to associate together in the acceptance of their rights. Harding address in Oklahoma City, October 9, 1920, as reported in The Daily Oklahoma, October 10, 1920. The greatest indignity suffered by Harding in his career was the allegation made during the campaign of 1920 that he had Negro forebears. This was

NOTES ARE ON PAGES 184-185 |

86 OHIO HISTORY

part of the white backlash reactions

that were aroused by the moderate

concessions made by Harding and the

Republicans to the rising Negro-rights

movement. To be attacked for racial

reasons was not a new experience for

either Harding or the Republicans. The

whites, especially Democratic ones,

had been backlashing ever since

anti-slavery days. The Hardings had been

punished with "nigger talk"

ever since they espoused anti-slavery sentiments

in a Democratic section of Ohio in

pre-Civil War times. It has been standard

treatment in certain sections of

society, especially in the Civil War and

Reconstruction periods, for Republicans

to be called "nigger worshippers"

because of their interest in civil

rights.

In the 1920 campaign Harding's talents

for political adjustment were given

an unusual test by the new dimensions of

the Negro situation. It was a

matter of simple statistics that the

potential Negro vote in the North from

1917 to 1920 had more than doubled. The

great increase came not only

from the enfranchisement of the Negro

women by the adoption of the

Nineteenth Amendment to the United

States Constitution, but from the

migration to the North during World War

I of many thousands of southern

Negroes to work in the production

stimulated by the conflict. Imigration

of cheap labor from Europe was cut off

during World War I; therefore,

the work force had to be largely

replaced by southern Negroes.1

Increased tension resulted not merely

from an increase in numbers of

Negroes in the North, but from an

increase in the Negroes' desire to remedy

their own grievances. The bars of racial

restriction were not as great in

the North as they were in the South; and

Negroes as a result were sure

to be more active in the direction of

securing more equality in political,

civil, and even social rights. Many who

had served in the armed forces during

the war returned home with new ideas and

hopes stirring in their minds

and spirits. Negro rights societies

increased in number and militancy. So

did Negro newspapers. In 1910 the

National Association for the Advance-

ment of Colored People was born with its

exhilarating idea that the Negroes

could not expect to attain more equal

rights unless they themselves actively

and intelligently sought to get them.

Increased lynching after World War I

drove the NAACP and other Negro

organizations to vigorous counter action

in the direction of federal

legislation.2

In 1919-20, as the signs of increased

Negro militancy became apparent

to whites, there arose the inevitable

backlash. Whites, who had never

indulged in the unthinkable thought of

Negro equality, were suddenly

confronted with it; and they did not

like it. The return of four hundred

thousand Negro soldiers to civilian life

had explosive possibilities. An upsurge

of lynchings followed. The "Red

Summer" of 1919 saw race riots in some

twenty-five American cities, north and

south.3 Therefore, as the Republican

party and Harding made adjustments to meet the

requirements of retain-

ing the loyalty of the traditionally

Republican, and now more numerous,

Negroes, the defenders of white supremacy,

especially Democratic ones,

made themselves heard. The race issue,

which by certain gentleman's code

NEGRO RIGHTS AND WHITE BACKLASH 87

of honor, was not supposed to be a part

of politics, became such in the

minds of many people. Candidate Warren G. Harding

became involved in

this new political issue.

Harding was his usual moderate and

careful self in meeting this new

Negro problem. In his 1920 campaign

conduct, he and his fellow Republican

leaders sought to appease the Negro

desire for equality in politics and

civil rights by two strategic maneuvers.

One was to make displays of

devotion to the general principle of

racial equality in rights and opportunities

without getting down to specifics. These

displays were made in such con-

trolled circumstances as the shaping of

the Republican platform, in Harding's

Acceptance Day address, and in the

well-managed and subsidized ceremonies

of Colored Voters Day at Marion on

September 10. Many strategems were

necessary in these affairs in order to

keep the militants quiet. The second

maneuver was to mount a protest movement

in behalf of the liberties of

the citizens of the Negro republic of

Haiti. These liberties seemingly were

being subverted by the American

occupation of the Caribbean island engi-

neered by the Democratic administration

starting in 1915. Wilson's Haiti

policy and its support by Democratic

vice-presidential candidate, Franklin

D. Roosevelt, gave Harding a golden

opportunity to play politics.

Even though Harding's efforts in the

direction of equal rights for Negroes

were moderate, he was the victim of a

savage backlash movement by

"lily-white" Democrats in the

North and in the border states. As the

campaign closed, some of the more

desperate Democrats launched two

attacks on Harding. One was a claim that

his equal-rights talk was a threat

to white supremacy. The other was the

attempt of certain Democrats to

represent Harding as a Negro.

The first Republican adjustment to the

Negro-rights demands took place

at the June, 1920 nominating convention

at Chicago with the insertion

of an anti-lynching plank in the party

platform. The Negroes wanted far

more than that -- at least the five

Negroes appointed to the platform

committee did. They presented a

resolution asking not only for an anti-

lynching plank, but for other planks

pledging the party to favor: (1) a

force act assuring the right to vote to

all Negroes in the South, and else-

where, as provided for in the Fourteenth

and Fifteenth Amendments to the

Constitution; (2) a civil rights act

assuring the abolition of segregation

and discrimination because of color; and

(3) a general commitment that

the United States should be made safe

for democracy at home before it

undertook to do so in foreign lands.

When the committee accepted only

the anti-lynching plank, the Negro

delegates tried to introduce the other

planks in the convention itself. They

were ruled out of order. They therefore

had to be content with a plank entitled

"Lynching" which read, "We urge

Congress to consider the most effective

means to end lynching in this

country which continues to be a terrible

blot on our American civilization."4

More adjustment to Negro demands was

necessary, and the man to

do it, of course, was the candidate.

Harding went farther toward Negro

88 OHIO HISTORY

equality than the platform, but not as

far as many Negroes thought he

had. He went much farther, however, than

the lily whites and the back-

lashers could tolerate.

Strong pressure for racial equality came

from Cleveland Negroes who

were being courted by the local

Republican organization. Harding was

asked by the enthusiastic

editor-in-chief Omond A. Forte of the militant

Cleveland Advocate if he would

abolish color discrimination in the govern-

ment departments, if he would get rid of

the "Taft Southern Policy" of

appointing only lily-white Republicans

in the South, or if he would follow

the Fourteenth Amendment requiring a cut

of southern representation in

Congress if the Negroes were deprived of

the vote. Pressure for racial

equality was also brought by Cleveland

Republican leader Maurice Maschke,

who informed Harding that the Cleveland

Negroes were anxious to repair

"the damage" done by their

opposition to Harding in the primary campaign.

Harding dignifiedly rebuked Maschke for

encouraging the Negroes so much.5

Nevertheless, in his July 22 Acceptance

speech, Harding went a long

way in seeking Negro support. His words went

far beyond the anti-lynching

stage. In fact they were so

characteristically eloquent and expressive in

behalf of Negro equality that the

impressionable Negro could -- and did

-- think that they meant the coming of a

new day of Jubilee. "No majority,"

said Harding, "shall abridge the

rights of a minority ... I believe the Negro

citizens of America should be guaranteed

the enjoyment of all their rights,

that they have earned their full measure

of citizenship bestowed, that their

sacrifices in blood on the battlefields

of the republic have entitled them to

all of freedom and opportunity, all of

sympathy and aid that the American

spirit of fairness and justice

demands."6

By following up these promises of Negro

equality with the appointment

of Negro leaders to high places in

Republican councils the Republicans

could ensure the enthusiastic

propagation of the new doctrine of Negro

equality by the Negroes themselves --

always, of course, on the understand-

ing that they would not go "too

far," that is, agitate for integration. One

of these so favored was the Atlanta,

Georgia Negro attorney, Henry Lincoln

Johnson. The influential Johnson was

given two appointments, one as a

delegate to the National Convention and

the other as member from Georgia

of the powerful Republican National

Committee. Johnson became an ardent

exponent of Harding's type of Negro

rights promotion. He represented

the candidate's Acceptance remarks as

being on a par with Abraham Lincoln's

Emancipation Proclamation. To the Negro

Methodist pastor, Reverend

J. G. Robinson of Philadelphia, Johnson

wrote, "The Senator spoke to our

souls in matchless words in his letter

of acceptance and filled with joy

every downcast Negro heart with his

assurance of his remembrance of our

travails, and his purpose, so far as the

president's power lies, to allay them."7

The other felicitous Negro appointment

to the Republican hierarchy was

Mrs. Lethia C. Fleming, wife of

Cleveland city councilman Thomas W.

Fleming. As Johnson, she also was given

two positions high in the Republican

hierarchy. The first was to be one of

the five lady members of the Republican

NEGRO RIGHTS AND WHITE BACKLASH 89

National Executive Committee, and the

other was to be chairman of the

Colored Women's Bureau of the Republican

National Committee. We do

not have examples of her utterances in

behalf of Negro rights, but we do

have Harding's testimony as to her high

qualities as a Republican. In

recommending Mrs. Fleming to Maurice

Maschke for the appointments

Harding wrote, June 16, that her

"intelligence is equal to any woman. She

is tactful, prepossessing in appearance,

charming and acquainted with

politics."8

On the basis of the moderate Negro

rights statements of the Republican

platform and the Harding Acceptance

speech, the Republicans launched a

program of publicity designed to keep

things moderate and general and

to curb the militants who wanted more

specifics. This was done by three

well-managed enterprises: (1) the

sponsoring of Negro Republican clubs

throughout the North by Johnson's Negro

Voters Bureau; (2) the prepara-

tion and circulation of special party

pamphlets designed for Negro voters;

and (3) the staging of Colored Voters

Day at Marion on September 10.

Henry Lincoln Johnson's club work stressed

not only the creation and

enlargement of Negro Republican clubs,

but the sending to each of them

a mimeographed form letter on official

Republican National Committee

letterheads, urging them to pass

resolutions of endorsement of Harding

and Coolidge. The letter was simple and

graphic. It opened with a brief

statement saying that "everyone

admits that lynching and mob-violence

are the chief aggravations of the

colored man in the United States." Beneath

this were two columns. The right-hand

column was headed "What the

Republican Party Says," and

contained three well-spaced quotations of

the Republican platform on lynching,

Harding's Acceptance Day remarks,

and a statement by Calvin Coolidge on

Negro constitutional rights. The

left-hand column was headed "What

the Democratic Platform Says," and

was largely blank, except that opposite

"Democratic platform" was the

word "NOTHING," opposite "Governor

Cox" the words "ABSOLUTELY

NOTHING," and opposite

"Franklin Delano Roosevelt" the statement "NOT

ONE WORD."

Johnson was very proud of this form

letter. At the bottom of a copy

sent to Marion was the hand-written

note, "Kind Senator Harding: Just

for your information, every important

meeting of colored people in the

'voting states' is passing sweeping

endorsements of your candidacy in response

to requests indicated above." To

this, Harding's office replied that the Senator

was gratified that the colored people were so generally

endorsing his candi-

dacy with the aid of the "clear,

concise and convincing contrast of the

platforms and candidates relative to the

rights of colored people."9

Johnson's campaign pamphlets were

rousing publications. Harding was

represented as the successor of Abraham

Lincoln and William Lloyd Garri-

son. The Democratic Party was castigated

with a revival of bloody-shirt

talk and was represented as based on too

much southern white political

influence and the disfranchisement of

the Negro. The hypocrisy of the

Democrats was cited in their support of

world democracy abroad and

90 OHIO HISTORY

non-democracy in the South, in their

talk of enforcement of the Eighteenth

Amendment and the nullification of the

Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amend-

ments. Anti-Negro statements by southern

leaders were quoted. In a heavily

leaded-boxed paragraph was Senator Ben

Tillman's remark, "We stuffed

ballot boxes, we shot Negroes: we are

not ashamed of it." A Congressman

Taylor was similarly represented as saying,

"The Democratic Party is a

white man's party in the North, as well

as in the South." Discrimination

and jim crow treatment by the Democrats

in the army, in the offices at

Washington, and in the reception of

veterans were minutely detailed. There

was a special pamphlet written by Negro

Major John R. Lynch, United

States Army Retired, which went deeper.

It assailed the Democrats for

the sin of instilling an inferiority

complex in Negroes so that they could

not understand the higher issues at

stake in the election. "He enters the

campaign handicapped for the

consideration of great issues," wrote Major

Lynch. Always the Democrats were scored

as the Negroes' "lifelong enemy."

Always they were depicted as citing only

the bitter past and present; noth-

ing was said of the Negro future. There

were no specific promises about the

full meaning of the equality that was to

come.l0

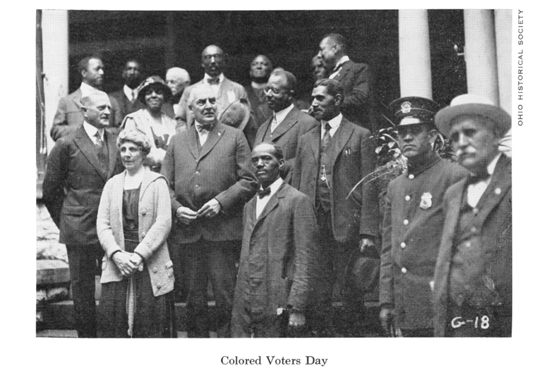

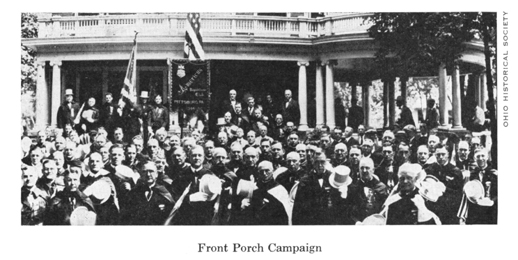

Grand climax of the Johnson campaign was

Colored Voters Day, Septem-

ber 10, 1920, at Marion. This affair was

a piece of "front porch" politicking

designed to win Negro votes. The program

was carefully managed, heavily

financed, and skillfully prepared so as

to discourage the militant Negroes

from coming and to encourage the

religiously minded to come in great

numbers.

There were many sources of Negro

militancy with whom the Johnson-

Harding moderates had to parry and

thrust in keeping Colored Voters

Day under control. One of these was the

Cleveland Negro radicals, who

were making real progress in getting

into the city government. The way

to handle them was to leave them alone.

When they saw the nature of

the Colored Voters Day preparation, they

lost interest and stayed out of

it. There was also the NAACP. Harding

was able to cope with this organiza-

tion by the Haiti maneuver, as will be

presently described. Finally there

was the most dangerous of all the

militant groups, the Equal Rights League

and its executive secretary, William

Monroe Trotter of Boston.

Henry Lincoln Johnson was fully aware of

the danger of Trotter and

the Equal Rights League. He made it

quite clear at the outset of the prepara-

tions for Colored Voters Day that there

should be no pilgrimage to Marion

of that organization. On August 9 he

explained his views to Harry M.

Daugherty, Harding's campaign manager.

What he wanted was a visit to

Marion of a few well selected moderate

Negroes who would not raise any

embarrassing questions. This kind of

people are "alright." "They are just

a part," Johnson wrote, "of

the great majority of the colored people of

the United States who want to see the

Senator only to assure him of their

enthusiastic and loyal support. When it comes to the

Equal Rights League,

it may be made up of Monroe Trotter of

Boston and some other wild-eyed

people like that. They may produce some

embarrassment. So before you

NEGRO RIGHTS AND WHITE BACKLASH 91

make any dates may I beg that you let me

advise with you so that no

mistakes whatever will be made? We do

not want any colored people to

come to see the Senator with question

marks. The platform declaration

and the unmatched declarations of

Senator Harding and Governor Coolidge

not only satisfies but enthuses the

colored Republican voters of the United

States and we do not want to be bothered

with any more delegations coming

up and asking how a man stands about

things."11

Johnson had his way. Trotter attended

the Colored Voters Day ceremonies,

but he was entirely surrounded and

contained by the moderate group of

Negroes whom Johnson managed to

assemble. This group consisted mostly

of the Negroes of two Baptist

conventions which happened to be meeting

in Indianapolis and Columbus on

September 10. Negroes who would have

to come from more remote parts of the

country were kept from coming by

the simple device of refusing to pay

their expenses. For example, the Reverend

J. G. Robinson of Philadelphia, head of

the Convocational Council of the

African Methodist Episcopal Church,

wanted to bring a big delegation of

Negro Methodists to Marion for the

September 10 demonstration. "Let me

know," he wrote Johnson on August

28, "if the National Committee will

assist me with my delegation -- R. R.

fare only?" Johnson very bluntly

set Reverend Robinson's mind at ease on

this proposition. "I should rather

advise," he wrote, "against

such a pilgrimage for two reasons: (a) the

terrible expense involved and the

absolute inability of the National Com-

mittee to finance such an excursion; (b)

the lack of need of such an

undertaking."12

The Negro Methodists may have been kept

away from Colored Voters

Day by the denial of railroad fare, but

that was emphatically not the case

of the Negro Baptists who were meeting

at Indianapolis and Columbus.

These places were near enough to Marion

to make the expense less onerous

on the Republican party financial

coffers. The Republican involvement is

clearly demonstrated by a letter of

August 23 from Harry Daugherty in

Columbus to Howard Mannington of Harding's

staff in Marion. This letter

shows that the Republicans not only paid

the railroad expenses of the two

sets of Negro Baptists but helped defray

the expenses of at least one of

the religious conventions. In his letter

Daugherty said, speaking of the

Columbus convention, "Am asking

Rev. J. F. Hughes, General Manager

of the National Negro Baptist

Association, to call on you tomorrow A. M.

This is the big association you know.

Yesterday I told you to see if Hughes

thought he could arrange to have those

in Indianapolis to come also. This

will involve the expense of two special

trains. Whatever you, Carmi Thompson

and Senator New [of Chicago

headquarters] work out is alright with me.

I have done all I can about it.

Confidentially I have secured for Hughes

and paid him $1000 to help some of the

expenses of this convention."13

A danger that lurked in the background

of the preparations for Colored

Voters Day was the jim-crow status of

Marion's hotel and restaurant

facilities. Harding was amply warned on

this in a friendly way by former

Senator Theodore E. Burton and, in a

challenging way, by Ralph W. Tyler

92 OHIO HISTORY

of the Cleveland Advocate. Burton

said that a leading Cleveland colored

Methodist minister, who had recently

visited Marion, was denied access

to any drug store or restaurant in the

city and that in consequence there

could be no Negro endorsement of Harding

in Cleveland. Tyler wrote

Christian along the same lines,

acknowledged that it was not Harding's

fault, but insisted that it would hurt

Harding's candidacy for his home town

to engage in practices

"diametrically opposite to the Senator's pronounce-

ment for justice for the race as

American citizens." Tyler proposed that

the secretary try to get the Marion

"civic associations" to agree to suspend

jim crowism for the duration of the

campaign. Harding, in his reply to

Burton, said that this was the first

time he had ever heard of any lack of

consideration and fair treatment of

anybody in Marion, but there was

nothing he could do about it. He felt sure

that the committee on arrange-

ments would provide for equal

opportunity "even though that involved some

phases of segregation. You know [he

added] racial prejudice is a thing

which can not be set at naught."

The result was that there were no

Cleveland Negro visitors to Marion on

Colored Voters Day.l4

The result also was a smoothly arranged

segregated affair. It was punc-

tuated with religious fervor, but

dominated by Hardingesque moderation.

No episode took place to reveal to the

public eye the fact of the prevalence

of jim crowism on Colored Voters Day.

"We have made arrangements,"

wrote Mannington to Johnson, "with

a local colored church to feed these

people and they will erect a big tent,

where all visitors can be properly

and adequately fed." He hoped that

there would be a "goodly crowd,"

perhaps a thousand people, so that the

church would not lose money on

the venture. It is doubtful that there

were that many present, but, what-

ever the number, there were three things

apparent from the arrangements

program prepared by Mannington and given

to the master of ceremonies,

D. R. Crissinger. One was that the

assemblage was overwhelmingly religious.

Another was that they visited Harding in

four separate groups: the Baptists

from Columbus who arrived at Harding's

home at 8:15 A.M. and returned

to Columbus by the 10:00 A.M. train; the

Baptists from Indianapolis who

saw Harding at 1:00 P.M.; a Methodist

group which called late in the

afternoon; and a delegation from the

"National Race Congress" which saw

the candidate at 11:00 A.M. The third

point of interest was the complete

segregation of the Negroes as per Item

No. 5 in Mannington's mimeographed

instructions: "All delegations must

be told where they can be subsisted,

that is, by the A. M. E. Church of

Marion, wherever they will serve dinner

and supper, and all should be especially

directed to go there." A copy of

these instructions was given to J. W.

Thompson, Marion chief of police.15

The main ceremony took place at the

front porch at two o'clock. It was

marked by climax and anti-climax.

According to the New York Times

report, the affair "had all the

fervency of a camp meeting." A colored band

from Columbus escorted the visitors to

the porch playing "Harding Will

Shine Tonight." At the porch, Henry

Lincoln Johnson took charge and

told the candidate that they were not

present to ask him questions because

|

NEGRO RIGHTS AND WHITE BACKLASH 93 |

|

they knew what he thought. To make the formal presentation of the Baptist brethren Johnson called on William H. Lewis, former assistant attorney general under Taft. Lewis likewise said there would be no questions, "We seek no pledges. Your life, your high character, your public services are pledge enough. Your splendid pronouncement in your speech of acceptance that the colored citizens should be guaranteed the enjoyment of all their rights and entitled to freedom and opportunity, because they had measured up to the requirements of citizenship by their sacrifices on the battlefields of the republic, gives courage and inspiration." Lewis's remarks were punc- tuated with exclamations from the audience of "Hallelujah," "Amen," and "You tell it." Then with awesome effect there appeared before them General John J. Pershing, who happened to be Harding's guest. He was introduced to the thunderstruck assemblage and gave his inspirational blessings, praising the Negroes for their service to their country during the war. Mrs. Fleming was also introduced. With excellent poise she was spokesman for the Negro women, praising Harding for his part in bringing them the vote.16 And then, at the grand climax, came forth the candidate. In words of friendly dignity he spoke, not as an evangel of liberty, but in a tone of fatherly moderation. He did not stir them up -- he calmed them down. His central theme was the great progress the Negroes had made since the days of slavery, the noble part they had played in America's progress and |

94 OHIO HISTORY

America's wars. He knew of their trials,

the disgraceful lynchings, the irksome

discriminations. He knew also of their

restraint under great provocation.

He praised them for this, but he also

reminded them that continued progress

was possible only in a land of ordered

freedom and opportunity, such as

was America. He reminded them that such

progress was not possible in

the land of the new slavery under the Bolshevik

dictatorship of violent

Russia. He enjoined them to work hard,

obey the law, and avoid violence.

He knew they would understand the basic

truth behind his counsels of

moderation. "The American Negro has

the good sense to know this truth,

has the good sense, clear head, and

brave heart to live it; and I proclaim it

to all the world that he has met the

test and did not and will not fail

America."17

Harding's references to violence in his

Colored Voters Day address need

to be understood in the context of the

public feeling in the Red-scare days

of 1920. He was not warning so much

about the violence of lynching as

he was about the violence of the race

riots of 1919. His words were: "Brutal

and unlawful violence whether it proceeds

from those who break the law

or from those who take the law into

their own hands, can only be dealt

with in one way by true Americans,

whether they be of your blood or of

mine." This was small comfort to

the militants who saw in it the inference

that the blame for the riots was as much

the Negroes' as the whites'. It

was great comfort to the whites who saw

the law supporting the status

quo which was so favorable to them.

What the militant Negroes thought of

this as the subdued assemblage

dispersed at the end of the day, is not

recorded, at least it has not been

discovered. The militant Trotter of the

Equal Rights League was present.

But he had no part in the public

speech-making. He had his say, but it

was behind closed doors. There are at

least two versions of what was

said about the Equal Rights League's

special emphasis on segregation. One

was by the Associated Press

correspondent who reported: "One of those

who conferred with the Senator was

William Monroe Trotter of Boston,

Executive Secretary of the National

Equal Rights League, who asked that

segregation of Negro employees of the

Federal Government be abolished.

He declared afterward that the Senator

had given the request appreciative

consideration." The other version

of what happened is taken from The

Union, a Cincinnati Negro newspaper. It stated that the

conference was

attended by Trotter and the president

and vice-president of the Equal

Rights League, N. S. Taylor and M. A. N.

Shaw. They asked for federal

action against lynching, denial of the

vote, segregated travel, and segregation

in the executive department of the

national government. "Senator Harding

promised a careful study of the

Congressional measures to the end of

correction of the abuses. He declared

emphatically against federal segregation

and said, 'If the United States cannot

prevent segregation in its own

service we are not in any sense a

democracy.' The League officers expressed

to him satisfaction with the candidate's

acceptance speech statement. Taylor,

Shaw and Trotter said league officers

would support Harding vigorously."18

NEGRO RIGHTS AND WHITE BACKLASH 95

If any of the militant Negroes still

thought that Harding's Negro-equality

talk was what he wanted it to be, his

hopes were frustrated by the final

campaign utterance, which occurred in

Oklahoma City on October 9. There

were other more important subjects on

Harding's mind at this time as,

for instance, the League of Nations, on

which he had expanded with such

unusual effect at Des Moines on October

7. But some party managers

were saying that there was a chance to

swing Oklahoma over into the

Republican column. A speech was

therefore scheduled for the capital of

the Sooner State. It was obviously

necessary to reassure the race-minded

voter of this commonwealth of the

essential moderation of his Negro rights

ideas.

Harding's Oklahoma stand on race

relations included two points: (1) an

assertion in favor of the separate but

equal doctrine; and (2) a repudiation

of the idea of the use of the force of

the federal government in enabling

the Negroes to vote.

Harding was forewarned and prepared on

the subject. The morning issue

of the October 9 Daily Oklahoman had

asked him three sets of questions

two of which dealt with race relations.19

One set was, "Do you or do you

not favor race segregation? Do you or do

you not favor separate cars for

the white and black race; separate

schools, restaurants, amusement places,

etc.?" Harding's answer was a general

assertion of "race equality before

the law," but a specific

endorsement of segregation. He said, "I can't come

here and answer that for you. It is too

serious a problem for some of us

who don't know it as you do in your

daily lives. But I wouldn't be fit to be

president of the United States if I

didn't tell you the same things here in

the south that I tell in the north. I

believe in race equality before the law.

You can't give one right to a white man

and deny it to a black man. But

I want you to know that I do not mean

that white people and black people

shall be forced to associate together in

accepting their equal rights at the

hands of the nation."

On the subject of Negro voting, The

Daily Oklahoman wanted to know

whether or not he favored a revival of

the attempt to pass the Lodge Force

Bill of 1890 authorizing "the use

of federal force if necessary to supervise

elections in southern states, thereby

guaranteeing the full vote of the great

negro population of the south,"

Harding's answer was a ringing, No! "Let me

tell you," he declared, "the

Force Bill has been dead for a quarter of a

century. I'm only a normal American

citizen, and a normal man couldn't

resurrect the dead if he wanted

to."

Such talk pleased southerners, but not

the militant Negroes of the North.

The latter made known their displeasure.

On October 20, Trotter telegraphed

from Westfield, Indiana that the Equal

Rights League was disturbed. He

requested to know whether Harding's

Oklahoma speech "alters your state-

ments to the League at Marion or

interprets their meaning." H. M. Harris of

Washington, D. C., telegraphed in behalf

of thirteen Negro-rights advocates

that Negro "disappointment is

general." Harris demanded to know "if you

are president whether you will stand on

your pronouncement in Marion or

96 OHIO HISTORY

in Oklahoma." To Trotter and

Harris, Christian answered blandly that there

was no conflict in Harding's various

speeches and no change in his position.20

Evidently there was widespread knowledge

among Negroes of Harding's

segregationist stand in Oklahoma. At

least the Republican organization said

there was, and they took steps to stop

its spread. The candidate was asked

to say nothing more about it. On October

11 Senator New, head of the

Chicago Republican publicity bureau,

telegraphed Christian, "Please say to

chief much excitement today among

colored element over Oklahoma City

answer. Avoid any further reference of

any kind if possible."21

Seemingly, there was little or no

knowledge of Harding's Oklahoma race

remarks among northern whites. The press

had much talk about Harding's

desire to carry Democratic Oklahoma for

the Republicans, but that was as

far as it went. For example, the October

9 speech was represented in the

New York Times of the next day as

having dealt with oil and the League

of Nations. No reference was made to the

Negro aspect of his speech.

Not all Negro opinion was offended by

the Oklahoma address. One Negro

publisher was actually exhilarated by

it. This was R. B. Montgomery of

Minneapolis, editor and publisher of the

National Advocate, "the leading

Negro journal of the North West."

"We have never heard such language,"

wrote Montgomery, "from a Christian

gentleman like yourself since the days

of Abraham Lincoln, who was a friend to

all the people. Thousands of

Negro papers throughout the United

States are supporting you and your

colleague for the next President of the

United States."22

Actually, there were many Negroes who

could not see any difference

between Harding and Trotter on the race

question. This came from that

ancient tradition that the Republican

party was the Negroes' saviour. It

did not occur to many Negroes to analyze

men's speeches. Even if the time

came, as it always did, when the Negroes

could not get all they expected,

they would tend to reason quite

naturally that all race progress came from

the Republicans and that there was no

hope from the Democrats because of

their southern background. Typical of

this kind of thinking was that of

W. P. Dabney, editor of the Cincinnati

Negro weekly, The Union. Dabney

at all times boomed and boosted equality

for Harding and Trotter. Dabney's

headlines for Harding were expansive. "Harding's

Creed for Humanity!"

"HARDING, DAVIS, WILLIS and the

Entire Republican Ticket Must be

Elected, then there will be an end of

the segregation policies that have so

disgraced a land consecrated to

LIBERTY." For Trotter the Negro editor

was similarly expansive: "GAME AS A

LION. LITTERED AND REARED

IN THE JUNGLES OF DARKEST AFRICA."

After Trotter had visited

Cincinnati, Dabney recorded, "He is

anti-segregationist, anti-jim crowist,

and the volleys fired by him against

racial discrimination and its condonation

by some of our servile people will bear

good results."23

Strange to relate, the NAACP did not

give the cause of Negro rights the

vigorous support in 1920 which it has

become famous for in recent years.

Perhaps what caused this organization to

focus on the lynching problem and

the situation in Haiti was the atmosphere of white

resentment resulting from

NEGRO RIGHTS AND WHITE BACKLASH 97

the race riots of 1919. In 1920 its most

active leader, so far as the national

political campaign was concerned, was

field secretary James Weldon Johnson,

whose chief concerns were with lynching

and Haiti. On August 9, at the

request of the NAACP board of directors,

he and a few of his colleagues had

visited Harding in Marion and presented

him some questions involving

lynching, federal aid to education, the United

States occupation of Haiti,

the right to vote, and certain aspects

of segregation. According to Johnson,

Harding told his callers that he agreed

with them in principle about these

things, but that "from the point of

view of practical politics, he could not

make them the subject of specific and

detailed statements in a public

address." Subsequent nudging from

Johnson did not budge the Senator.24

Developments in the Caribbean soon

brought a meeting of minds between

Johnson and Harding on Haiti. It

happened that Haiti was one of the subjects

discussed at the August 9 conference,

and it was also true that Johnson was

an expert on the matter. Indeed, on

August 28, there appeared in The Nation

the first of his exposure articles

condemning the United States occupation

of that island and the alleged

mistreatment of its Negro inhabitants. Johnson

sent Harding a copy of the August 28

article and promised "to show up

exactly what the Washington Administration

had done in Haiti." Three more

articles followed weekly in The

Nation and Harding was supplied with

copies.25

Whether by design or by accident,

Harding soon injected himself into the

Haiti problem in such a way as to be

highly pleasing to Johnson and his

NAACP colleagues. The Senator did this

on September 17 in a speech

blaming the "rape of Haiti" on

Vice-Presidential candidate and Assistant

Secretary of the Navy Franklin D.

Roosevelt, who had publicly boasted that

he had written the constitution of

Haiti. Harding did not quote Johnson,

but the spirit of his criticism was as

sharp as Johnson's, and his few facts

cited were among the many cited by

Johnson. Harding's phrase was "thou-

sands of native Haitians have been

killed by American Marines and . . .

many of our own gallant men have been

sacrificed." Johnson's phrase was

"the slaughter of three thousand

and practically unarmed Haitians, with the

incidentally needless death of a score

of American boys."26

Whatever the connection was between

Harding and Johnson on the Haiti

question, the two of them certainly

started some fire-works. Secretary of

the Navy Daniels denied the charges,

Roosevelt called them the "merest

dribble," and Harding apologized in

regard to personal charges, but added,

"This does not in any way abate my

opinion as to the policy of your

Administration in dealing with Haiti and

Santo Domingo." Then came the

allegations by Navy and Army officers

concerning the specifics of alleged

American atrocities in Haiti. These were

from Rear Admiral Harry S. Knapp,

Marine commandant in Haiti, General John

A. Lejeune, and former Marine

commandant in Haiti, Brigadier General

George Barnett. Civilian commen-

tators also added their gory

contributions. The result was that on October 15

Secretary Daniels ordered an official

inquiry, and by October 19 a full board

of inquiry was holding sessions.27

98 OHIO HISTORY

Consequently, there was instant

rejoicing of the NAACP and congratula-

tions were sent to Harding. When Daniels

and Roosevelt started to squirm,

Johnson wrote on September 21, "I

see that you have finally gotten under

the skin of the Wilson administration.

You have smoked them out and got

them on the run and I hope that you will

keep them running." He added,

"You may depend upon the

reliability of the facts given in the information

which I sent you." Then, on October

14, when Daniels ordered his investiga-

tion, Mary White Ovington, chairman of

the board of the NAACP, exultingly

wired Harding, "The NAACP

congratulates you upon the result of inquiry

into the unconstitutional and brutal

invasion of Haiti." A few days later,

Negro attorney Samuel B. Hill of

Washington, D. C., recorded his feeling

of gratitude as he wrote Christian,

"May the God of our fathers preserve

and keep the Senator for the benefit of

America and her people without

harm."28

The Harding-Republican moderation on the

Negro rights issue was well

advised; it kept the lily-white backlash

down to size. If Harding had yielded

to the integrationists, he would have

damaged his appeal to race-minded

whites. The fact is that south of the

Mason-Dixon line, where the backlash

was greatest, there was a gain in the

Republican vote percentage in 1920

over the 1916 vote percentage from 41.5%

to 46.5%.29

Harding's moderation consisted of three

main factors: (1) concentrating

his courting of Negro voters on those in

the North; (2) favoring Negro

political and civil equality on a

segregated basis; (3) confining specifics to

such matters as opposition to lynching

and the alleged Democratic fiasco in

Haiti.

But there was a backlash movement

against Harding, nevertheless. As the

campaign waned and Democratic prospects

for success seemed to fade also,

some Democrats challenged their

opponents with two accusations. One was

to allege that Republicans were

endangering white supremacy, another was

to try to smear Harding with allegations

that he had Negro forebears.

Ohio became a minor storm center on the

integration issue. The Democrats

could not raise the question of Negro

equality in the nation at large because

Harding had repudiated such designs in

his Oklahoma address. But Buckeye

Democrats were thinking about their

opposition to possible Negro equality

in Ohio. In a circular letter sent out

on September 16 from Columbus,

Governor Charles H. Brough of Arkansas

told of his conference with W. W.

Durbin, chairman of the Ohio Democratic

State Executive Committee, in

which the latter had told him the Toledo

Pioneer was "urging race equality

and urging the Negroes to unite at the

polls." This led Brough to include

Harding in his animadversions. "It

is current knowledge here in the Middle

West," wrote the Arkansas governor,

"if Senator Harding and the Repub-

licans triumph, an effort will be made

to pass a Force Bill, which will mean

Federal bayonets to supervise Southern

elections." The governor also said

that Harding's Colored Voters Day speech

of September 10 led Trotter to

speak to the Columbus Negro Baptist

convention in favor of equal rights in

hotels, restaurants and elevators and to

assert "the oneness of the white

and black races."30

NEGRO RIGHTS AND WHITE BACKLASH 99

In mid-October Durbin and the Ohio

Democrats came out boldly with the

release by the State Executive Committee

of a circular entitled, "A Timely

Warning to the White Men and Women of

Ohio." The circular claimed that

the recent great influx into Ohio of

southern Negroes, plus the enfranchise-

ment of women, threatened to give

Negroes the balance of power in Ohio

politics. Central to their concern was

their fear of the Republican candidate

for governor, Harry L. Davis. As mayor

of Cleveland, Davis had appointed

twenty-seven Negroes to the city police

force and had placed other Negroes

in lucrative positions, the aggregate

annual salaries of which exceeded

$350,000. It was claimed that in some

cities the crowding of Negroes had

brought about serious consequences by

their moving into residential districts

and depressing the value of the

properties therein. Referring to certain Negro

newspapers, the circular declared,

"We find them openly predicting that full

social equality will be ensured them by

the election of Republican candidates."

One of these, the Toledo Pioneer of

September 11, had editorially urged its

readers to vote for Davis and other

Republican candidates for the legislature

so that a law would be passed

"making it a felony to discriminate against a

negro on account of his race."31

The Durbin circular gave Harding his

share of the blame for this increase

in integrationist agitation. Citing his

Acceptance speech and his Oklahoma

address, it claimed that the Toledo Pioneer

and the Cleveland Advocate

informed their readers "the

Republican nominee for President, if elected would

make himself a champion of that

cause." Further details emphasized that

these illiterate and ill-paid newcomers

were "haunted by aspirations for social

equality." The encouragement given

by the Republicans "of such ambitions

can only result in greatly magnifying

the evils we are facing."32

Reference to the pages of the Cleveland Advocate

for 1920 does not confirm

the Democratic allegations of specifics

by Harding on Negro integration. The

talk was in that direction, but it was

toned down in the face of overwhelming

opposition. It did so in respect to

Harding's segregation speech in Oklahoma.

In April, the Advocate, in

supporting Wood against Harding in the primaries,

editorially had condemned Harding,

saying that his association with lily-

white Republicans in the South

"stamps him as a man opposed to EQUAL

JUSTICE for the race." Yet when

Harding, as nominee, made his segregation

remarks at Oklahoma City in October, the

Advocate ardently supported

Harding, and was willing to let people

make their own interpretations. "There

are many," said the editor,

"who feel that the statement is upstanding while

there seems to be equally as many who

regard it as unfortunate. Some are

saying that the remarks inject a

quasi-social issue, which has nothing to do

with political matters, while others

declare that it means the Senator favors

'jim-crow' cars. Sober thinkers seem to

be willing to give it the benefit of

the doubt, and accept the many other

upstanding utterances as demonstrat-

ing the attitude of the candidate if he

is elected President." Advocate writer

Tyler expressed this feeling of

resignation in another issue of the paper.

"It is quite likely," he

wrote, September 25, "that Senator Harding's advocacy

of patience, and desistence from forcing

what the race conceives its just due,

will meet the approbation of those who are always

optimistic even in the face

100 OHIO HISTORY

of the most disheartening

discrimination, preaching patience rather than

radicalism, at all times."33

A most interesting phase of the white

supremacy backlash against Harding

developed when certain lily whites

discovered a leaflet originally published in

Cleveland in support of Harding. This

leaflet contained a montage of nine

pictures -- three were of Harding, Frank

R. Willis (candidate for Ohio

United States senator), and Harry L.

Davis (candidate for Ohio governor).

These were flanked by photos of six

Republican Negro candidates for the

Ohio legislature. The leaflet was

entitled, "EQUALITY FOR ALL," and

contained at the bottom a quotation from

Harding's Oklahoma City speech

stating, "I want you to know that I

believe in equality before the law.

That is one of the guarantees of the

American Constitution. You can not

give one right to a white man and deny

the same right to a black man."

The sentences stating that these

rights should be enjoyed in a segregated

manner were omitted. The leaflet was issued by Walter L. Brown of Cleve-

land, and contained the union label.34

Democratic segregationists north and

south seized upon this leaflet, re-

published it, and gave it wide

circulation to prove that Harding was an

integrationist. It was referred to

critically in a Cincinnati Times-Star editorial

on October 29. The writer said,

"For a week or more local Democrats have

been circulating a card on which are

portraits of the Republican candidates

for President, Governor and Senator. Grouped around

them are pictures of

the Negro Republican candidates for the

Legislature." One horrified lady,

Mrs. E. Taylor, of Mt. Victory, Ohio,

wrote Harding imploring him to say

that it was not true. She enclosed a

copy of the leaflet on which she wrote,

"is it true Mr. Harding is it oh i

can not believe it." On October 26 another

much disturbed gentleman, Frank E. Linny

of Greensboro, North Carolina,

chairman of the state Republican

committee, telegraphed in consternation

that the Democrats were about to

circulate that leaflet. Linny's letter con-

cluded, "Answer giving facts."

Two Oklahoma Republicans sent copies of

the leaflet to Harding, one commenting that

it was an example of "the dirty

gutter politics" of Democrats. But

there seem to be no replies to these letters

in the Harding Papers.35

Charges of the Harding family's alleged

Negro ancestry had been circulat-

ing for almost one hundred years. On

October 22, 1920, George Christian,

writing to Samuel C. McClure, publisher

of the Youngstown Telegram in

reply to inquiries, said that the Negro

ancestry charge was an "ancient lie

which has been revived by the

opposition." Christian said that it went

back to a chance and malicious remark

during an abolition-slavery campaign

nearly a hundred years ago. He added, of

course, that it had no basis in fact

and that Harding had "always

refused to dignify it by denial and attention."36

It is apparent that Harding was the

object of such allegations, made with

slanderous intent, throughout his life.

The first reference to the Negro

ancestry charges that has been uncovered

is found in the Marion Independent

of May 20, 1887. The Independent was

Marion's first Republican newspaper.

|

NEGRO RIGHTS AND WHITE BACKLASH 101 |

|

The development of the rival Republican Marion Star under Warren Hard- ing's editorship produced a wordy war between the two papers. The Inde- pendent's editor, George Crawford, was jealous of Harding and feared the Star's rivalry in the contest for official spokesmanship for the Republican party. As was the custom in those days, Crawford and Harding engaged in the exchange of mud-slinging epithets. On May 20 the Independent called the Star a "smut machine" and its editor a "kink-haired youth." The next day the enraged Harding fired back and notified the "retailer of Harding's genealogy" that he was a "lying dog" and "a miserable coward." On May 24th the Independent brought the exchange to an end by making a half- hearted apology. In the process, the Democratic Mirror of May 23 printed all the charges and counter charges and mocked the Independent's apology as a "beautiful . . . specimen of crawfishing." In none of his political campaigns was Harding exempt from these mixed- blood attacks. At least that is what the editor of the Philadelphia Public Ledger said in the midst of the October, 1920 campaign muckfest. "Such an effort to slay Senator Harding," said the editor, "has been in progress ever since his nomination. In fact, it has been tried repeatedly in his previous campaigns in Ohio. We have long known of the facts in this office, but have felt that there was no public good to be accomplished by open comment."37 The Republican National Committee became officially aware of the situa- tion in August and was ready with authentic genealogical data if and when needed. On August 20 West Virginia Senator Howard Sutherland wrote Chairman Hays that Democratic candidate Cox had told the game warden of that state, "either the grandmother or great grandmother of Senator Harding was a Negress." After some exchange of correspondence Hays promised Sutherland that he would follow the matter up and "take the vigorous steps you mentioned if necessary."38 What these steps were was |

102

OHIO HISTORY

not

mentioned in the Hays Papers, but it is evident from the Harding Papers

that one

step was to get the facts on Harding's ancestry from the accepted

family

genealogist. This authority on Harding ancestry was John C. Harding

of Chicago

who wrote to his Senatorial relative on October 16 that he was

loaning

"a book containing the Harding genealogy" to the Republican Na-

tional

Committee "who were seeking authentic information to overcome

certain

propaganda ... used to some extent by your opponent." In his reply

Harding made

one of the few references to the Negro slander so far dis-

covered.

"It was fortunate," the Senator said, "that you were able to

furnish

the data

requested, although I do not as yet know what use will be made

of it. I

have always been averse to dignifying this talk with attention or

denial, but

if finally deemed necessary, we will stamp it as the unmitigated

lie it

is."39

For a while,

the anti-Harding mixed-blood gossip circulated via under-

ground

methods. For example there was a one-page mimeographed sheet

entitled

"Genealogy of Warren G. Harding of Marion Ohio" and authorized

by

"Prof. William E. Chancellor of Wooster University, Wooster, Ohio."

This came to

be called the "Harding Family Tree" and read as follows:

Geo. Tryon

Harding Ann Roberts

Great

Grandfather Great

Grandmother

(BLACK) (BLACK)

Charles A.

Harding Mary Ann Crawford

Grandfather Grandmother

(BLACK) (WHITE)

George Tryon

Harding, 2nd Phoebe

Dickerson

Father Mother

(MULATTO) (WHITE)

Warren G.

Harding

Son

No children

have been born to Harding.

One of the

senders of this sheet, A. A. Graham of Kansas, said it had appeared

"on the

lines of the Rock Island railroad in southwestern Kansas."40

There were

others. Mrs. S. B. Williams of Columbus wrote with indignation

telling of

having attended a political meeting at Memorial Hall. "I saw a

man,"

she said, "with a copy of something reading it to a younger man. So

womanlike I

listened, and here he was reading what he said was a copy of

the Court

Records of Marion, trying to prove to the younger man that you

had negro

blood."41 George Clark of the Ohio Republican Advisory Com-

mittee

called this "moonlighting." He told of "paid emissaries . . .

going

from house

to house spreading vile slanders. . . . From vest pockets are

drawn

statements which dare not be printed in the open."42 The

Youngstown

Telegram of November 1 carried a story telling how, for weeks, a

whispering

campaign had

been going on in the border states supported by handbills

and

anonymous circulars that "appeared mysteriously between night and

morning....

Women who answered rings of the doorbell late at night were

told hastily

and emphatically by persons who seemed respectable enough

NEGRO RIGHTS AND WHITE BACKLASH 103

that Senator Harding's blood was not

pure white." Particularly vicious was

a paper strip attached to a picture of

Harding's father, seemingly of dark com-

plexion; the strip reading, "KEEP

WHITE [picture of a house] WHITE

VOTE FOR [picture of a rooster]."43

Many showed deep concern about the

effect of the mixed-blood taunts.

Traveling man Don Cox of Coshocton wrote

with much agitation that people

were telling him "no matter how

anxious they might be to vote for you they

positively would not do so

BECAUSE YOU HAVE NIGGER

BLOOD IN YOU"

"For God's Sake," he implored,

"get busy stamping it out." H. H. Abee of

Hickory, North Carolina told of people

circulating these stories and wanted

to know if such persons should be

arrested. "Rush answers," wrote Abee.

Franklin Williams of Cambridge, Ohio

reported that there were many voters

who say that they "will not vote

for a nigger President." S. A. Ringer of

Ada, Ohio, said that the Pathfinder magazine

printed that "you are one-

fourth negro.... As a result [added

Ringer] thousands of voters, especially,

the women voters, may be caused to vote

against you." W. W. Cowen, of

St. Clairsville, Ohio, reported a story

that "Harding was stopped in Masonry

because he had negro blood."

"If this charge is not true," wrote James Curren

of Cincinnati, "why don't you

protest. If not you will lose quite a lot of

votes." These are only a few of the

many references in the Harding Papers to

the Negro reports. To most of them

Harding's office replied that they were

not true, "baseless lies,"

"mendacious slanders," and so forth.44

Chief villain in the backlash campaign

of anti-Harding genealogical slander

was William Estabrook Chancellor, author

of the previously cited "Harding

Family Tree." This fantastic person

claimed to have the highest credentials

for his "facts" about Harding.

He was Professor of Economics, Politics and

Social Science at Wooster College,

author of several books including Our

Presidents and Their Office, and, apparently, one-time superintendent of

schools in Washington, D. C. Above all

he was an ardent Democrat. Earlier

in the campaign, in a letter to the Plain

Dealer, he had praised Wilson and

the league of Nations and criticized

Harding for his anti-internationality. He

had incidentally shown his anti-Semitic

feelings by claiming that the high

commisars of the Soviet Union were all

Jews seeking revenge for the pogroms

and other discriminations of the past.

Now, as the campaign closed, he

applied his alleged high scientific

qualifications to the production of "proof"

of Harding's Negro ancestry. Chancellor

later denied his authorship, claiming

that a Republican of the same name was

responsible.45

Among the products of Chancellor's

"researches" were posters that certain

Democrats were willing to finance and

release for circulation to help save

the country, as they said, from a Negro

president and his radical pro-Negro

ideas. One of these, dated October 18,

1920, was addressed "To the Men and

Women of America, AN OPEN

LETTER."46 It was said to be the result of

several weeks of touring the country

area of Harding's youth and of Chan-

cellor's interviews with hundreds of

people. The poster stated that the Hard-

104 OHIO HISTORY

ings had never been accepted as white

people. Warren Harding himself

"was not a white man." He was

said to represent "the results of social

equality through free race

relations." Referring to Harding's Central College

days at Iberia, Chancellor wrote,

"Everyone without exception says that

Warren Gamaliel Harding was always

considered a colored boy and nick-

named accordingly."

Chancellor offered in support of these

allegations four notarized affidavits

which he said he collected from former

residents of the Blooming Grove area,

Harding's former home, whom he had

interviewed in Marion and Akron.

These affidavits were printed in full.

From these people he obtained "the

common report" of "lifelong

residents" of the vicinity of Blooming Grove.

He claimed that he, himself, was an

ethnologist trained in scientific methods.

The statements in these affidavits were

amazingly specific. Harding's

father-in-law, Amos H. Kling, was

represented as having stumped the thir-

teenth state senatorial district in

1899, opposing his son-in-law's candidacy

for the senate on the grounds that

Harding was a colored man. Kling was

quoted as having declared on the streets

of Marion, at the time of his

daughter's marriage, that she was

marrying a Negro. Another affidavit raked

up the story of the murder, in 1849, of

Amos D. Smith by David Butler

because Smith called Mrs. Butler a

Negress. Mrs. Butler was a granddaughter

of Amos Harding, and a cousin of Warren

Harding's grandfather.

Suddenly in the last few days of the

campaign the slander stories burst

out on the front pages of some of the

nation's leading Republican newspapers.

The party strategy was to show that the

scurrilous Chancellor and his

Democratic backers had gone too far in

their dirty work.

Leading off was the Republican Dayton Journal.

On October 29, the

Journal in a

frenzy of outrage, blasted forth with full-spread, front-page

headlines five rows deep.

THE VILE SLANDERERS OF SENATOR HARDING

AND HIS FAMILY WILL SEEK THEIR SKUNK

HOLES 'ERE TODAY'S SUN SHALL HAVE SET

THE MOST DAMNABLE CONSPIRACY IN HISTORY

OF AMERICAN POLITICS

Over half of the front page was given to

an open letter "To the Men and

Women of Dayton" by editor E. G.

Burkam. It told of the circulation "in

cowardly secrecy" of "thousands upon

thousands of typewritten mimeo-

graphed and even printed statements

usually under the heading of 'Harding's

Family Tree' . . . These vile circulars

declare that Warren G. Harding has

Negro blood in his veins." These

allegations "ARE A LIE. Warren G. Harding

has the blood of but one race in his veins -- that of

the white race -- the

pure inheritance of a fine line of

ancestors, of good men and women." The

next day the entire front page of the Journal

was again given to statements

of rebuttal under the headlines:

The Whole Vile Structure of the

Slanderers Crumbles

Under the Avalanche of Evidence

NEGRO RIGHTS AND WHITE BACKLASH 105

The Democrats then countered with their

own charges of falsehood saying

that the racial attack on Harding had

originated with the Republicans of

Ohio in their own primary campaign.47

The fat was in the fire. Across the

nation swept the news of the attacks

on Harding's ancestry. Even the stately

New York Times gave the slanders

front-page headlines. It was there

reported that Professor Chancellor had

been dismissed from the Wooster College

faculty for his alleged authorship

of the circulars. Republican press

agents rushed to the defense of their

candidate with reams of genealogical

copy about the Harding family. The

Times called upon genealogist Charles A. Hanna to enter the

lists. Others

traced the name of Harding back to the

Domesday Book of 1086.48 Genea-

logical antiquity momentarily had

front-page billing.

More posters were in the offing. When

Republican reporters besieged

the ousted Professor Chancellor, they

got him so confused that he was

quoted in the Dayton Journal as

having denied that he was the author of

the anti-Harding posters. Thereupon

another set of posters came out, spon-

sored by the Democrats. One of them,

"The Truth Will Out!", was issued

from Columbus "By Order of

Democratic Ex. Com.", and signed by chairman

Ira Andrews and secretary Frank

Lowther.49 In this the professor was quoted

as saying that he had not denied his

authorship of the Negro stories and

that he was suing the Dayton Journal for

saying that he had. Even Repub-

lican national chairman Will Hays was

threatened with a lawsuit if he did

not withdraw his attacks on Chancellor's

genealogical reputability.

Republican posters to counteract

Democratic posters appeared. One of

them, entitled "The Harding

Stock," was issued by the Ohio Republican

State Executive Committee. It contained

a chart of the Harding descent

from the time of Stephen Harding, the

"blacksmith of Providence."50 This

Republican production reeked with

blondness and bravado. Long residence

in America, it said, has not robbed the

Hardings of "the characteristics so

pronounced in the Celt and the German .

. . The blue and gray eyes of the

Hardings of today are a legacy from the

Scotch-Irish blood that entered

the family through the Crawfords."

In Hardings' veins "flow the blood of

English, German, Welsh, Irish, and

Dutch." And this blood "has been spent

on battlefields where the stake was

justice and independence." The Hardings

were represented as the chief victims of

the Wyoming Indian Massacre of

July 3, 1778. "'Remember the Fate

of the Hardings' was the cry which rang

through the Wyoming valley as a party of

settlers sallied forth to wreak

vengeance on the blood thirsty savages."

Lord Hardinge, British Viceroy of

India from 1910-1916, was said to be

"undoubtedly a relative of the Ohio

Senator."

On Marion street corners things got

pretty hot. On November 1, in front

of a cigar store, Harding's father, Dr.

George, approached Democratic Judge

W. S. Spencer and loudly accused him of

responsibility for circulating the

Negro-blood stories. A friend of Dr.

Harding repeated the charges. "You're a

liar," shouted the Judge. The

doctor's friend thereupon punched the Judge

106 OHIO HISTORY

in the face. "Hit him again,"

shouted the crowd, and the Judge was knocked

to the sidewalk. The affair ended with

Dr. Harding assisting the Judge into

the near-by Court House.51

Obviously in the hysteria of the closing

days of the campaign, the discus-

sion of Negro rights had gotten far away

from the merits of the issue.

Whether Harding gained or lost in the

blood melee cannot be decided. It

was said that the mixed-blood charges hurt

him most in the border states,

costing him votes that might have gone

into the Republican column. Possibly

so. His segregation comments at Oklahoma

City, however, probably helped

counteract this loss. It is impossible

statistically to measure the effect of the

many factors influencing the voters'

choices.

As has been stated, the 1920

presidential election statistics show a definite

gain in the border states for the

Republican party over the returns for 1916.

Assuming the border states to be Arkansas,

Delaware, Kentucky, Missouri,

North Carolina, Tennessee, Maryland,

Virginia, and West Virginia, five of

them went Republican in 1920 (Delaware,

Maryland, Missouri, Tennessee,

and West Virginia); whereas only two of

them went Republican in 1916

(Delaware and West Virginia). Of the

total votes cast by the border states

awarded to the Republican and Democratic

candidates, 51% went for the

Republicans in 1920 as against 45% in

1916. In southern states the same

trend in favor of the Republicans is to

be observed. For one thing, Oklahoma

voted for Harding 243,415 to 215,521 as

against 148,113 to 97,233 for Wilson

in 1916. Taking the South as a whole

(including the border states) the figures

are: 46.5% Republican in 1920 as against

41.5% in 1916.52

It is to be pointed out that we have not

analyzed all the reasons for

Republican gains in the South in 1920,

since a general analysis of the election

is omitted in this paper. We have merely

pointed out that the Harding-

Republican Negro policy did not offset

other factors that may have caused

an increase in the number of Republican

votes in the South.

Moreover, it is evident that to some

degree the injection of the mixed-

blood issue softened the backlash

against Harding. An example of this is

shown by his ever-loyal brother in

Moosedom, James J. Davis. "It's very

seldom," wrote the enraged director

general of the Loyal Order of the Moose,

"I go off on a tangent, but if I

could have gotten a hold of that professor

that's circulating that stuff on you,

I'm sure I'd have punched his snout and

punched it hard, but I guess it's best

that we never met."53 Equally indignant,

but more restrained were the dignified

publishers of the Cincinnati Times-

Star, Charles P. Taft and Hulbert Taft. These gentlemen made

a front-page

news item out of "The Truth About

Harding's Ancestry." The Democratic

charges were headlined as falsehoods and

"Sneaking Propaganda." In a

signed editorial, they declared that the

Democratic tactics had "turned the

clock back fifty years."54 In

Tennessee, the Democratic Chattanooga Times

not only refused to print the Chancellor

material but gave strong support to

the Taft handling of the charges against

Harding.55 And there was the ever-

critical journalist, Robert Scripps,

who, according to Samuel Hopkins Adams,

wrote, "Tell him we don't care

whether it is true or not. We won't touch it."56

|

NEGRO RIGHTS AND WHITE BACKLASH 107 |

|

In conclusion, in terms of the Negro civil rights problems, Harding made little progress during the campaign of 1920. As with so many other problems, he was able to do more for the party -- there was a Republican victory in 1920 -- than for the people. In the North, as we have seen, he talked Negro rights but avoided specifics, taking advantage of the non-militancy of the Negro religious leaders, the anti-race riot feeling and the Red-scare mood of the general public, and the willingness of the NAACP to be satisfied with proposed reforms on the lynching question and on United States-Haitian policy. In the South, he soft-pedalled the race question and gave specific assurances of continued segregation. Nevertheless, he did prepare the way for two specific reforms, minimal though they were: anti-lynching legislation and withdrawal of the Marines from Haiti. In return for his efforts he received praise from some Negro leaders but was severely attacked by whites of the backlash persuasion.

THE AUTHOR: Randolph C. Downes is Professor of History at the University of Toledo. |