Ohio History Journal

JOHN PHILLIPS RESCH

Ohio Adult Penal System,

1850-1900: A Study in the

Failure of Institutional Reform

Throughout the latter half of the

nineteenth century Ohio prison reformers tried to

recast the state's penal system so that

it would rehabilitate criminals and restore them

to productive citizenship. By 1884

reformers succeeded in their efforts to secure leg-

islation to rehabilitate adult criminals

through classification, job training, moral and

academic classes, reduction of sentences

for good behavior, parole, and the introduc-

tion of the adult reformatory system.

Despite this impressive legislative

victory, the Ohio penal system was not substan-

tially recast. Prison reform laws were

partly undermined by the unresolved conflict

over the nature of the criminal and the

purposes of prison. Influential Ohio reformers

and some prison officials viewed the

criminal as a depraved social type. From this

perception grew the analogy that prison

should be a moral hospital where various

classes of criminals were treated and

then released when cured. Like hospitals,

prisons should have enough funds to

support curative programs and have an ade-

quate staff of professional attendants.

The money to implement these services was

to come from provisions in the

legislation.

The bulk of the public and most penal

authorities, on the other hand, saw the

criminal as a threat to personal safety

and property and were reluctant to spend

large sums of money on reformatory

programs. They expected the prison to punish

criminals and to act as a deterrent to

potential offenders. Many prison officials, cal-

loused by contact with desperate men,

ridiculed reformist plans as "pampering"

criminals and for turning prisons into

places of leisure and refinement. Efforts at

reform were resisted also by public

officials who wanted an unobtrusive, orderly and

self-supporting prison system and by

politicians who looked upon the penal system

as a source of patronage. The spoils

system resulted in frequent turnovers of per-

sonnel, made the creation of a stable

professional staff impossible, and undermined

enforcement of rehabilitation policies.

Persistent demands that prisons be self-

supporting blocked the construction of

adequate physical facilities and the funding

of expensive reformatory programs

authorized by the General Assembly. These

Mr. Resch is Assistant Professor of

History, University of New Hampshire, Merrimack Valley

Branch in Manchester.

Ohio Penal System

237

diverse views and interests resulted in

vacillating and conflicting policies which buf-

feted prison discipline, made a sham of

legislation aimed at recasting the penal sys-

tem by thwarting implementation, and

demoralized reformers.

In 1850 the Ohio penal system consisted

of the state penitentiary in Columbus,

county jails and scores of municipal

lockups. The penitentiary, completed in 1837,

received all felons--persons sentenced

to imprisonment for two years or more--

regardless of age, sex, or sanity. Its

discipline was modeled after the Auburn, New

York prison system of silent, congregate

labor during the day and separate confine-

ment at night. The avowed purpose of the

penitentiary, as Governor Return Meigs

stated in 1811, was to protect public

safety, rehabilitate criminals, and restore in-

mates to society as useful citizens.1

The governor and General Assembly of Ohio

were responsible for penitentiary

affairs, but supervision of the institution was left to

a board of directors which consisted of

three to five men chosen by the governor. The

duties of the board included an annual

report to the General Assembly, maintenance

of facilities, appointment of all

officers and guards, securing all labor contracts em-

ploying convicts, and enforcing

reformatory programs. County jails and municipal

lockups were controlled by Common Pleas

courts, but administration was usually

left to the sheriff.2 Jails

confined misdemeanants, persons accused of crimes, and

occasionally witnesses. They were

punishment and detention centers where inmates

were indiscriminately mixed under

notoriously inhumane conditions.

By 1860, while conditions in local jails

remained unchanged, the General Assem-

bly had passed two prison reform acts

modeled after New York and Massachusetts

laws. An 1856 act known as the

"good time law" permitted an inmate to reduce

his prison term through good behavior.3

An act passed in 1857 required classifica-

tion and separation of prisoners

according to "age, disposition and moral character."

This law specified that prisoners who

were assigned work with contractors be given

compensation. Inmates under twenty-one

were to be placed "in a shop by them-

selves," when character and conduct

permitted it, and be given employment that

would be beneficial after their

discharge. The law required the warden to send illiter-

ates and poorly educated convicts to

classes for two hours in the evening of each

working day from October to April and

for one and one-half hours each working

day for the remainder of the year.4

Although the intent of these laws was to

strengthen existing correctional programs

and to promote new rehabilitation

measures, prisoners at the penitentiary experi-

enced a decade of neglect and

debasement. Two major epidemics, frequent fires,

deterioration of facilities,

overcrowding, misuse of convict labor, alleged corruption

among officials and political jobbery

undermined reformatory discipline. Between

1850 and 1860 the succession of five

different boards of directors and eight wardens

led to shifting and often conflicting

policies partly because there was no common

standard of professionalism. Officials

were usually hired on the basis of political

partisanship or business

accomplishments, as well as on their social standing, gentle-

1. For a survey of the Ohio penal

system, 1803 to 1850, see Clara Bell Hicks, "The History of

Penal Institutions in Ohio to

1850," Ohio Archaeological and Historical Quarterly, XXXIII

(October 1924), 359-426; Ohio, Senate

Journal, 1812, p. 9.

2. Laws of Ohio, 1843, "An

Act for the Regulation of County Jails," XLI, 74-77.

3. Laws of Ohio, 1856, LIII,

133-134.

4. Laws of Ohio, 1857, LIV, 127-129.

|

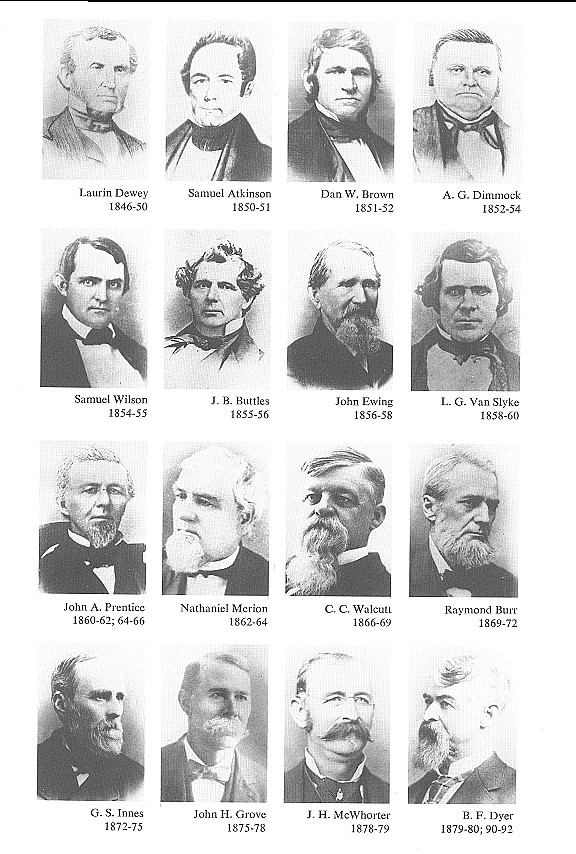

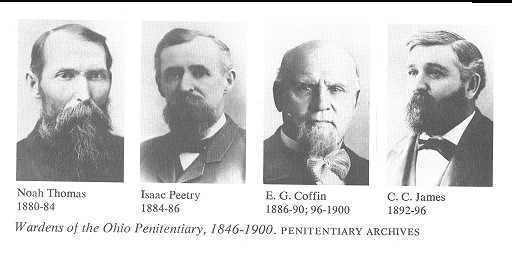

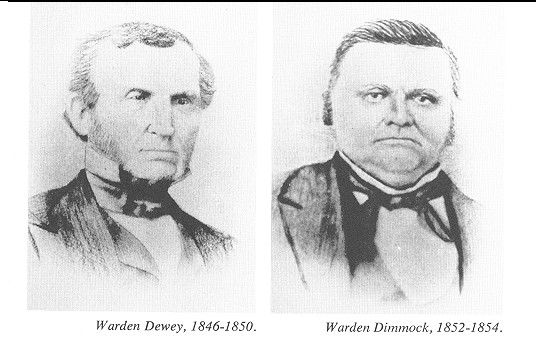

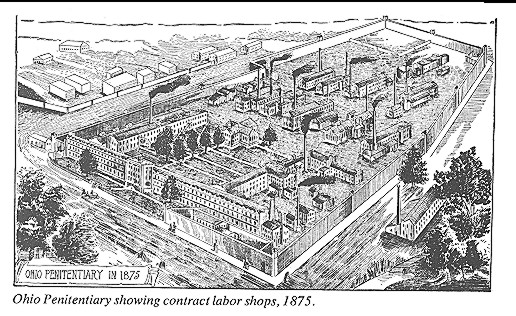

manly conduct and Christian character.5 The extent and effects of this fluctuation and conflict in policy are best illustrated in the administrations of Wardens Laurin Dewey and Asa Dimmock. Warden Dewey (1846-1850) shared many of the attitudes held by philanthropic reformers. He thought public sentiment toward the treatment of prisoners was "too harsh, unyield- ing and unforgiving." Dewey believed that prison discipline should incorporate the Christian spirit of forgiveness which led the fallen "from the bylanes of vice and wickedness ... into the paths of virtue and probity."6 Under his regime prisoners were encouraged to read the Bible, pray before breakfast, go to services conducted by the chaplain and attend Sabbath school led by volunteer teachers. Dewey was particularly proud of the prison's library, singing school and special events such as temperance speeches, a sermon on Thanksgiving Day, songs on July Fourth and the appearance of "distinguished vocalists." He stressed the importance of musical programs because they contributed to that "great end of prison discipline, improvement and reformation" of the inmates. Observing that some prisoners wept during the concerts, Dewey concluded that music had effects which were "good, softening and subduing to their spirits, and filling them with gratitude for the effort to entertain them, and to break the dread and drear monotony of prison life."7 To improve the moral environment Dewey insisted that guards be models of Christian deportment. Guards were not to whistle, shuffle, laugh loudly or act in an undignified manner. When dealing with inmates guards were to show "mutual re- spect and kindliness and endeavor to exact the character and promote the interests of the Institution." For the prisoners Christian deportment meant silence and con-

5. Three examples follow. L. W. Babbitt, who became one of the directors of the Ohio Peni- tentiary in 1856, was recommended because he was "a gentleman of Education & of good busi- ness habits, formily [sic] a democrat but now a strong supporter of the republican cause." Petition to Governor Salmon P. Chase, January 24, 1856, Box 2, Chase Papers, Ohio Historical Society, J. D. Morris was recommended to continue as a director because his qualifications fulfilled the requirements of the office: he was from the right part of the state, had "good moral character," was a businessman who would "likely watch with care the interests of the State" as well as the "wellbeing" of the inmates, and was a "good Republican" whose reappointment would "go far to shut the mouths of the opposition." Elbridge G. Ricker and William West to Salmon P. Chase, April 5, 1856, ibid. In 1854 Colonel Harris was nominated because he was a "thorough going and hard working Democrat" and because his appointment would be "Satisfactory to the party in this County." G. L. Vattier to Governor William Medill, January 13, 1854, Box 1, Medill Papers, Ohio Historical Society. 6. Ohio, Executive Documents, "Annual Report of the Directors and Warden of the Ohio Penitentiary, 1850" (1851), XV, Part I, 128, 129. 7. Ibid., 130-131. |

|

trition. Prisoners were not to communicate with each other, exchange looks or winks. They were to show respect for the guards and visitors. Their discipline also included the lockstep and punishment by solitary confinement, the shower bath and whipping not to exceed ten strokes--for misconduct.8 This policy continued until 1852, when a new board of directors and its warden, Asa G. Dimmock, overturned the system. In his first report Warden Dimmock asserted that he found the prison to be a "bedlam." According to Dimmock, disci- pline and order had broken down and it appeared as though the prisoners had taken over the penitentiary. He reported that instead of silence and Christian deportment, rowdy convicts openly used profane language and sang obscene songs. Dimmock found locked chests in cells where the inmates kept food and "deadly weapons." One convict, he stated, had recently attacked Deputy Warden John Huffman, nearly kill- ing him with a knife he had presumably concealed in a locker. Dimmock concluded that prisons accomplish "more good, in the protection of the rights of person and property, and have a greater moral influence upon society" with rigid discipline, shorter sentences and fewer pardons. He stressed the importance of using the prison as a deterrent to crime by making it a "terror to evil doers." Dimmock argued that "whenever the Penitentiary becomes a pleasant place of residence--when it ceases to be regarded with fear and dread by those disposed to do evil--whenever a relaxa- tion of its discipline, a mitigation of its deprivations, and an extension of its privi- leges, converts it into something like an Asylum for the wicked, then it loses all its influence for good upon the minds of men disposed to do evil, and affords no per- manent security to the lives and property of the people." The warden expressed determination to deprive the inmates of all the luxuries and joys of life to emphasize

8. Ibid., 173, 177. |

Ohio Penal System 241

the "difference between vice and

virtue--honesty and crime."9 For the remainder

of the century, under different wardens,

prison discipline often fluctuated between

the extremes of Dewey's Christian

deportment and Dimmock's deterrence through

deprivation and terror.

Prisoners were subjected not only to

inconsistent disciplinary practices but also

to appalling physical conditions which

made a mockery of rehabilitation. In 1849,

"121 prisoners died largely from a

cholera epidemic," while in 1852 inmates were

described as "neglected and poorly

clad, niggardly fed." Buildings, already dilap-

idated, were permitted to deteriorate

further to reduce maintenance costs. In 1856

the prison directors reported that the

"cells [were] infested with bed-bugs and fleas,

the stoves and heating apparatus broken

up, the fire-engine useless for the want

of repairing, and the hose belonging to

it unfit for use."10 In 1857, however, some

of the wooden beds and floors were

replaced with iron bedsteads and cement floors,

reducing the vermin and packs of rats.

Despite these improvements Warden John

Ewing observed that an inmate was

released after six or ten years "with a constitu-

tion completely broken down, a common

suit of clothes and five dollars in his pocket.

Justice and humanity calls aloud for a

remedy! Will the call be responded to?"11

By the end of the 1850's the

penitentiary was in disarray. A typhoid epidemic in

1858, frequent fires of "unknown

origin" and a rising prison population threatened

order and thwarted rehabilitation. The

chaplain, Lorenzo Warner, who was primar-

ily responsible for reformatory

programs, tried to look at the prison's troubles through

lenses tempered with optimism and pious

hopes. While his report asserted that "prog-

ress" was being made toward convict

reformation through the good time law and

prison school, he also confessed that

the prison was a "failure" as a reformatory

institution. In a moment of candor he

compared his position and that of his fellow

officers to being between Scylla and

Charybdis. The person trying to reform convicts:

Is between the State and the State's

prisoner, and if he shift [sic] to the side of humanity

and reform, citizen bullets whistle all

around him, and if he turn [sic] to protect the State,

poison arrows, dipped in calumny, will

cut the air close to his ear, and stick in his gar-

ment, if not in flesh.12

The following year a nineteen percent

increase in prison population undermined

further Warner's frustrating efforts to

reform criminals. Because the number of

inmates (853) exceeded the number of

available cells (695) officials were forced

to convert the chapel into a dormitory

for an average of 135 men, thus adding to the

breakdown of the Auburn rules of silence

and separation.13

Alleged corruption by guards and prison

officials and state exploitation of convict

9. Ohio, Executive Documents, "Annual

Report of the Directors and Warden of the Ohio

Penitentiary, 1852" (1853), XVII,

Part II, 24-30. For additional evidence of Dimmock's punitive

and "terror" policy, see Ohio,

Executive Documents, "Annual Report of the Directors and

Warden of the Ohio Penitentiary,

1853" (1854), XVIII, Part I, 488-489.

10. Ohio, Executive Documents, "Annual

Report of the Directors and Warden of the Ohio

Penitentiary, 1850" (1851), XV,

Part I, 143, 147-148; ibid., "Annual Report, 1852" (1853),

XVII, Part II, 4; ibid., "Annual

Report, 1856" (1857), XXI, Part I, 73.

11. Ohio, Executive Documents, "Annual

Report of the Directors and Warden of the Ohio

Penitentiary, 1857" (1858), XXIII,

Part I, 201.

12. Ohio, Executive Documents, "Annual

Report of the Directors and Warden of the Ohio

Penitentiary, 1858" (1859), XXIII,

Part I, 195-203.

13. Ohio, Executive Documents, "Governor's

Annual Message, 1859" (1860), XXIV, Part II,

49; ibid., "Annual Report of

the Directors and Warden of the Ohio Penitentiary, 1859," Part I,

335.

242 OHIO

HISTORY

labor further discredited the

penitentiary. In March 1856 a former clerk at the

penitentiary, R. S. McEwen, was indicted

for embezzlement. In July of that year

McEwen printed a disclaimer in which he

accused former Wardens Dimmock and

Buttles of theft. McEwen quoted an

earlier published rumor that Dimmock had

turned the female wing into a harem for

his own pleasure. Warden Buttles was

called "one of the most consumate [sic]

hypocrites that ever disgraced a tabernacle

of poor frail humanity." McEwen

accused Buttles of seducing a young lady after

promising her that he would use his

influence with the governor to get a pardon for

her cousin.14

The scandal was exploited by the

Republican administration, which had replaced

the Democrats. In its 1856 annual report

the new board of directors charged that

Dimmock and Buttles owed the

penitentiary between $3500 and $4000. In addition

the board accused prison officers and

"outsiders" of using prison workshops to make

personal items for themselves, such as

clothing, shoes, and furniture. The directors

also criticized state use of convict

labor to construct the capitol building. They

charged that this use of convict labor

increased prison costs by inefficient perfor-

mance compared with free labor, by

higher cost of guarding the men outside prison,

and by loss of revenue received from

contract labor performed within the prison.

The construction of the capitol also

disrupted prison discipline because convicts were

smuggling tobacco and liquor and were

arranging escape plans while they were out

on work assignments. The directors'

report concluded with the statement that with

good business management "the

Institution will support itself and yield a small rev-

enue to the State."15

In 1860 Republican Governor Salmon P.

Chase, in an effort to correct the physi-

cal inadequacies and overcrowding at the

penitentiary, appointed a commission, au-

thorized by the legislature, to consider

enlarging the facilities.16 The legislature acted

by passing laws authorizing the

expansion of the penitentiary as well as the construc-

tion of a new 800-man prison.17 These

recommendations were not carried out be-

cause of the disruption caused by the

Civil War and a twenty-eight percent drop in

prison population between 1861 and

1865.18 During the war rehabilitation programs

were all but abandoned as prison

managers became preoccupied with mounting

deficits. In their 1863 annual report

the directors stated that the law requiring class-

ification of offenders and separation of

inmates under twenty-one from the rest of

the population "was totally

impractical under existing circumstances." The chaplain

voiced his disappointment at the low

enrollment--twenty to thirty men--in the

day school. In 1866 Chaplain Albert G.

Byers confessed that "the indiscriminate

association of prisoners, regardless of

age or degree of criminality, renders hopeless

14. R. S. McEwen, The Mysteries,

Miseries, and Rascalities of the Ohio Penitentiary, from

the 18th of May 1852, to the Close of

the Administration of J. B. Buttles (Columbus,

1856),

3-5, 62.

15. Ohio, Executive Documents, "Annual

Report of the Directors and Warden of the Ohio

Penitentiary, 1856" (1857), XXI,

Part I, 75-79.

16. Ohio, Executive Documents, "Governor's

Annual Message, 1859" (1860), XXV, Part II,

49. The address was made on January 2,

1860.

17. Laws of Ohio, 1860, LVII,

57-58; ibid., 1861, LVIII, 62-64.

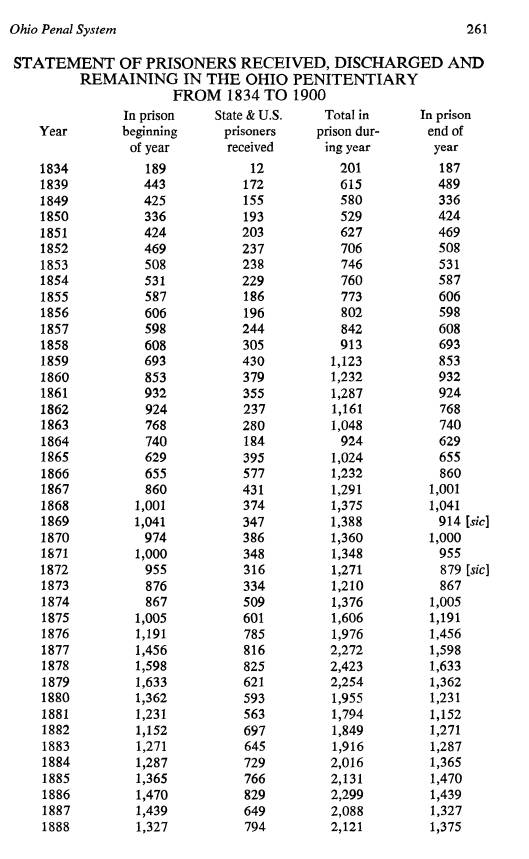

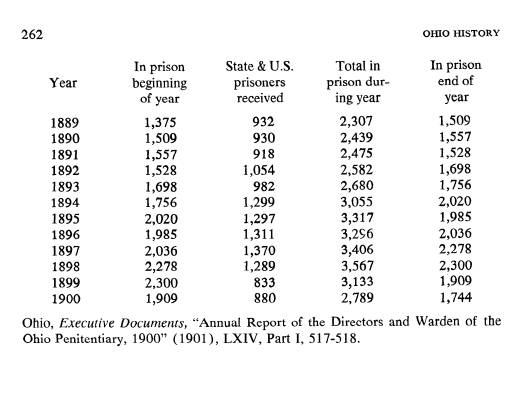

18. Inmate statistics can be found in

each volume of the penitentiary reports. A summary of

reception and population statistics

reproduced at the end of this article (p. 261) appeared in Ohio,

Executive Documents, "Annual Report of the Directors and Warden of the

Ohio Penitentiary,

1900" (1901), LXIV, Part I,

517-518.

Ohio Penal System 243

such efforts at reformation as might

otherwise promise success."19

In January 1867 Republican Governor

Jacob D. Cox and the General Assembly

hoped to end this drift and find new

methods of coping with the alarming increase

in prison population, which jumped

thirty-four percent between 1865 and 1867, by

creating a State Board of Charities.20

The board, which was fashioned after New

York and Massachusetts boards, was

established in 1867 to inspect the penal system

and offer ways and means of improving

it.21 In a series of reports the Board of State

Charities denounced the penitentiary and

condemned the local jails as a "disgrace

to the State and a sin against

humanity." The jails' filth and depressing influences

were "most perfectly adapted to

destroy self-respect--the basis of all manly char-

acter--and to educate and perfect the

younger and less hardened, to the full capac-

ity of their teachers." The jails

were, in short, "little better than seminaries of

crime."22

The board recommended that these

conditions be corrected through classification

and separation of prisoners according to

age and crime, by providing religious and

moral instruction for the young and

useful employment for all. The board's secre-

tary and former penitentiary chaplain,

Albert G. Byers, also suggested that supervi-

sion over Ohio jails be transferred from

local to state officials. Central control was

necessary to enforce uniform discipline

and common hygienic standards because local

officials neglected their duties. He

observed that there was not a "county jail in the

State where the laws can be practically

applied. There is also such diversity of

administration as to render our jail

system one of unmitigated evil." The following

year the board proposed an integrated

state-supervised system of municipal houses

of correction, detention centers for the

accused, and regional workhouses for minor

offenders.23

The State Board of Charities, after

censuring the penitentiary for its failures to

reform criminals, advocated a system of

specialized or "graded" prisons with the

regime of each institution adjusted to

the type of inmate. The board recommended

construction of a prison for adult

offenders of all ages who were not considered

hardened criminals and urged that no

institution exceed 500 to 600 inmates to permit

personalized treatment. The board also

recommended that discipline at the peni-

tentiary be stiffened and that it

"should embrace as much of sternness, not to say se-

verity, as would be consistent with a

highly civilized and Christian State like Ohio."

At the other end of the projected graded

system, men in the proposed intermediate

prison "should be surrounded with

every good influence possible." They were to be

made aware that the "'way of the

transgressor is hard,'" yet they were also to be

given opportunities to improve their

character through religious and educational

programs. The mark system was endorsed

as a means of recording a prisoner's

19. Ohio, Executive Documents, "Annual

Report of the Directors and Warden of the Ohio

Penitentiary, 1863" (1864), XXVIII,

Part II, 10, 17; ibid., "Annual Report, 1866" (1867),

XXXI, Part II, 195.

20. Ohio, Executive Documents, "Governor's

Annual Message, 1866" (1867), XXXI, Part I,

270.

21. Correspondence from Governor Jacob

D. Cox to prospective members of the board shows

that the legislature conceived the board

to be advisory, and essentially a showcase for reform

rather than an instrument of change. Cox

pointed out that the board's powers had to be grad-

ually increased through hard work and

the prestige of its members. Letterbook February 20,

1867--May 31, 1868, Box 6, Cox Papers,

Ohio Historical Society.

22. Ohio Board of State Charities, Annual

Report for the Year 1867 (1868), 3, 10-11.

23. Ibid., 5, 11, 34; ibid.,

Annual Report for the Year 1868 (1869), 12-15.

244 OHIO

HISTORY

progress toward reformation. The board

suggested that marks be used to determine

the transfer of a prisoner to an

institution within the system which conformed to the

measured change in the inmate's

character. The 1867 report accepted the scheme

presented by Gideon Haynes, warden of

the Massachusetts State Prison, that the

length of a sentence be determined by

the inmate's conduct as measured by the mark

system. According to Haynes, good marks

reduced the prison term and bad marks

lengthened imprisonment.24

These proposals made by the Ohio Board

of State Charities were part of an emerg-

ing reform effort to adapt features of

the Irish prison system for adult felons to

American penal institutions. Between

1854 and 1863 that system was developed

in Ireland by Walter Crofton and was

popularized in America by Enoch Cobb Wines,

Secretary of the New York Prison

Association, and by Franklin B. Sanborn of the

Massachusetts Board of State Charities.

Under the Irish system a convict spent his

first eight months in solitary

confinement followed by a second stage of confinement

where he was employed on public works

during the day and was housed in an indi-

vidual cell at night. No conversations

with other inmates were permitted in the

public works prison. Within this stage

the prisoner's conduct was recorded and

measured by a mark system first devised

in 1840 by Alexander Maconochie when

he served as governor of the Norfolk

Island (Australia) penal colony.

Under Maconochie's plan each convict was

assigned a debt of marks equivalent

to the severity of his crime. The

principle of the scheme was to place the responsi-

bility for parole in the prisoner's

hands by granting early release as soon as the con-

vict paid his debt of marks. In

Maconochie's model the earning columns consisted

of four sub-categories which were

personal deportment, diligent labor, academic

achievements, and religious knowledge. A

prisoner lost credits and increased his

debt through misconduct and for

"indulgences" like extra food. Maconochie argued

that marks should be subtracted for

luxuries "to prove and strengthen character by

exhorting men voluntarily to

reform." Although the deduction of marks did not

add extra years to the term set by law,

deductions did reduce the chance of parole.

Maconochie believed that the mark system

ended monotonous prison life and created

a regimen of incentives and rewards,

particularly through early release, which re-

formed inmate character. Crofton adopted

a variation of Maconochie's plan as an

incentive for Irish inmates to improve

their "grade," enjoy increased privileges, and

"earn" a transfer to an

"intermediate prison." In the intermediate prison an inmate

worked without close supervision and

occasionally was employed outside the prison.

Instead of confinement in separate cells

at night, the convict was housed in a dormi-

tory. Any breach of the rules during the

third stage of confinement meant immediate

reversion to the public works prison.

Upon proof of reformation, however, the pris-

oner was granted a "ticket of

leave," or parole, under police supervision.25

The principles, apparatus, and reported

success of the system in rehabilitating

24. Ibid., Annual Report for the Year

1867 (1868), 5-10.

25. This section on the Irish prison

system is a synthesis of numerous sources. For a descrip-

tion of the four stages of the Irish

system as well as views on penal reform which were adopted

by the Ohio Board of State Charities see

Enoch Cobb Wines and Theodore W. Dwight, Report

on the Prisons and Reformatories of

the United States and Canada (New York,

1867), 62-77.

The mark system was described by

Alexander Maconochie in a series of letters and published

works. Alexander Maconochie, Penal

Discipline: Three Letters (London, 1853) and Alexander

Maconochie, Penal Discipline (London,

1856), 1-5. For general surveys of English prison devel-

opments including the Irish system see

Lionel Fox, English Prisons and Borstal System (London,

1952) and Gordon Rose, The Struggle

for Penal Reform (London, 1961). The popularization

Ohio Penal System 245

criminals appealed to American reformers

such as Wines, Sanborn, and Byers. The

Irish system encouraged the inmate along

a course toward reformation through a

rational and controlled process. The

first part of the process was apparently intended

to break the inmate's will and to induce

contrition through eight months of solitary

confinement. In the second phase the

criminal's character was hopefully reshaped

through a program of public works and

rewards for good conduct which was mea-

sured by a mark system. In the third

step the inmate was prepared for economic

usefulness and social reintegration

under quasi-normal conditions in the intermediate

prison. The success of the reformatory

programs was tested during the subject's

parole. By urging the adaption of this

process to the Ohio penal system in its 1867

report, the Ohio Board of State

Charities rejected the conventional Auburn model

of prison discipline. The board

contributed to a new thrust in American prison

reform which led to the creation of the

National Prison Association in 1870 and

the reformatory movement prominent in

the latter part of the century.26

In the late 1860's, however, the board's

proposals were thwarted by conservative

and skeptical penal officials. In their

1867 report the penitentiary directors referred

to reform plans as "mere

theory." They stated that as yet there was no solution to

the problem of criminal rehabilitation;

that despite existing labor, moral, and reli-

gious programs criminals left prison

"as hardened and as dangerous to the State as

they were when they were

sentenced." While not proposing any changes themselves,

the directors warned that implementing

penal theories "without careful observation

and practical tests, is of little

value." They concluded that more consultation among

prison officials should precede the

introduction of reforms.27 In 1868 the General

Assembly did not adopt the reformatory

concept but passed a joint resolution to

expand the penitentiary, thereby

maintaining the status quo.

The work of an 1869 house committee on

prison reform revealed the continuing

controversy and political mudslinging

generated by proposals to recast the penal

system. That committee introduced

legislation abolishing the prison board of direc-

tors and establishing a Board of

Classification which was to be composed of four

of the Irish system was the major thrust

of post-Civil War prison reform. Franklin B. Sanborn,

"American Prisons," North

American Review, LII (1866), 404-412. In 1870 the first congress

of the National Prison Association

meeting in Cincinnati focused on the Irish system and tried

to popularize it. See pamphlet,

John P. Resch, "The 1870 Cincinnati Prison Congress" (Center

for the Study of Crime, Delinquency, and

Corrections, Southern Illinois University, 1970), 3-22.

For papers on the Irish system given at

the Cincinnati Congress see Enoch Cobb Wines, "The

Present Outlook of Prison Discipline in

the U.S.," The National Prison Congress Transactions,

1870 (Albany, 1870,) 15-20, and Franklin B. Sanborn,

"How Far is the Irish Prison System

Applicable to American Prisons?" ibid.,

406-414. Later support for the Irish system came from

Oliver Wendell Holmes. See Oliver

Wendell Holmes, "Crime and Automatism," Atlantic

Monthly, XXXV (1875), 477-481.

For an early Ohio reference to the

achievements of the Irish prison system see Governor Jacob

Cox's annual message to the General

Assembly in January 1867. In that speech Cox pointed out

the prison experiments being carried on

in other states and noted the success of the Irish system

in Great Britain. Ohio, Executive

Documents, "Governor's Annual Message, 1866" (1867), XXXI,

Part II, 268-269. In its 1869 annual

report the Board of State Charities asserted that the Irish

system was the best it had studied. The

report developed features of that system and urged that

parts of it be applied to the

penitentiary. Ohio Board of State Charities, Annual Report for the

Year 1869 (1870), 18-21.

26. For an overall account of the

movement for adult reformatories and the early experiments

at the Elmira, New York reformatory, see

Blake McKelvey, American Prisons (Chicago, 1936),

107-115, and Louis B. Robinson, Penology

in the United States (Philadelphia, 1923), 125-126.

27. Ohio, Executive Documents, "Annual

Report of the Directors and Warden of the Ohio

Penitentiary, 1867" (1868), XXXII,

Part II, 280; Laws of Ohio, 1868, LXV, 302-303, 305.

246 OHIO

HISTORY

unpaid commissioners and the warden. The

creation of a Board of Classification

reflected the house committee's intent

to make the penitentiary more reformatory

by specifically charging its

administration with the duty of classifying convicts "with

respect to age, sex, character, and

probable reformation" and prescribing training

for each criminal class. The bill also

provided for construction of an intermediate

prison in the northern half of the

state. In the hearings on the bill Warden Charles

C. Walcutt argued that there was no need

for a new prison because inmate popula-

tion had peaked and was beginning to

decline. In addition Walcutt alleged that add-

ing another prison would lead to

duplication and failure. The house committee

rejected Walcutt's arguments and

asserted:

Believing, with the worthy warden, that classification,

with a view to the reformatory treat-

ment, is demanded by the best interests of the State and

every consideration of Christian

humanity, we are led to ask, can that

be done by enlarging this prison [the penitentiary]

to a capacity for two thousand to three

thousand convicts [the projected population fig-

ures made by the committee for 1899] as well

as for the convicts and as profitably for the

State, as by having two or more prisons?28

The committee further cited the report

of the Prison Association of New York

which endorsed the construction of small

institutions for 300 to 600 men and an

intermediate prison. "These are the

unanimous convictions," the legislators ob-

served, "of all the prison

managers, of a lifetime's experience. But our worthy

Warden, with his three years'

experience, holds a different opinion." The committee

answered Walcutt's charge that those who

wanted another prison were selfishly dis-

regarding the interests of the state by

accusing the people and representatives of

Columbus and Franklin County of

hypocrisy and duplicity. The committee revealed

that the prices for food and articles

purchased by the prison in central Ohio as well

as maintenance costs were higher than in

the northern part of the state. They

asserted that "the people of

Columbus and Franklin County ... have for forty years

been, and are still, fattening at the

public crib--selling this 'stuff' to the prison

for two, three, and four prices."29

The State Board of Charities joined the

fray by attacking the political contamina-

tion of the penitentiary management.

"Party politics," the board stated in its 1869

annual report, "and, even worse,

party cliques or rings, have too long controlled the

appointments and consequently the

management of the Ohio Penitentiary." The

board asserted that the prison system

was "radically defective" and urged a change

in sentencing to give prison officials

authority to release criminals when they were

judged reformed. "This plan

proposed the treatment of the criminal, rather than

the treatment of his crime. It looks

upon the man as morally and socially disordered.

... Let the criminal be sent to prison;

let him be treated as his case may seem to

require; when he recovers, discharge

him." The board repeated its support of the

Irish system and averred that despite

defects which can be found in any penal system,

28. Ohio, House Journal, 1869, "Reformatory Penitentiary System,"

26-60. Prior to this report

a joint committee of the General

Assembly submitted its findings on the proposal to build a new

prison. That committee recommended that

no further expansion be made at the penitentiary,

which had been enlarged from 700 to 1050

cells between 1860 and 1868. The committee advised

that a smaller institution be built in

the northern part of the state. Unlike the later house

committee report, the joint committee

avoided penal theory by suggesting that the question

whether the new institution should be an

intermediate prison "can best be regulated after the

construction of the new buildings, by a

proper revision of the laws."

29. Ibid., 28-45.

Ohio Penal System 247

it was the best existing prison regime.

Apparently aware of the political obstacles

blocking authorization of an

intermediate prison, the board suggested that the addi-

tions to the penitentiary being

considered by the legislature include "three distinct

and virtually separate prisons"

under a common management. Each unit should

adapt features of the Irish

system--separation in the first unit, congregate labor in

the second, reformatory programs with

progress presumably measured by marks in

the third. The board, however, did not

feel that parole or ticket of leave as it was

known in Great Britain was practical

because of "our vast extent of country and

its many political divisions, each

constituting an independent jurisdiction."30

The failure of the Board of Charities

and its supporters to pass legislation at this

time establishing an intermediate prison

and recasting prison management revealed

the weakness of the penal reform

movement. The appeals for reform were appar-

ently effectively repulsed by

conservative prison officials and their political allies.

In their 1870 annual report the prison

directors accused the reformers of trying to

make the prison a "place of ease

and leisure" and to strip it of "every vestige of ter-

ror or aversion." They rejected the

proposal to permit prison authorities to release

criminals when cured because such

decisions should not be left to the fallible mind

of man and because of inconsistent

management due to the spoils system. They

contended that the existing good time

law was wise, adequate and workable. The

directors continued to defend contract

labor, which the board had questioned, by

arguing that there was no evidence that

contract labor impaired reformation and

that it was profitable. The directors'

support of the status quo and their suspicion

of change was succinctly recorded:

"We prefer our present system, to one which

has failed financially, or to an untried

experiment."31 The inertia of the system and

a decline in prison population at the

turn of the decade to a level well within the

physical limits of the penitentiary

weakened the effort to recast Ohio's penal system,

and in February 1872 the legislature

dissolved the Board of State Charities.

Between 1872 and 1876 prison officials

continued their efforts to make the peni-

tentiary profitable and useful to the

state. In 1873 the directors exclaimed that the

"Penitentiary has not only

maintained itself during the past seven years, but it has

in addition paid into the State Treasury

more than fifty-eight thousand dollars....

With prudence and economy, and in the

absence of an epidemic or other great calam-

ity, it may continue to be self

supporting." The usefulness of the prison was in-

creased by the construction of a gas

works within the walls which was to supply the

penitentiary as well as local public

benevolent institutions. In 1875 the legislature

tried to ensure a profit from the prison

by authorizing the construction of new shops

to lure contractors to hire convict

labor. In their annual report for 1875 the directors

credited these shops for keeping the

prison in the black despite the panic which ad-

versely affected the economy.32

In addition to making money, officials

attempted to improve the hygienic condi-

tions of the prison. In 1873 a cholera

epidemic left twenty-one inmates dead and

aroused efforts to improve the

penitentiary's sanitary system. The following year

30. Ohio Board of State Charities, Annual

Report for the Year 1869 (1870), 14-21.

31. Ohio, Executive Documents, "Annual

Report of the Directors and Warden of the Ohio

Penitentiary, 1870" (1871), XXXV,

Part I, 18, 437-446; Ohio Board of Charities, Annual

Report for the Year 1870 (1871), 18. The Board of State Charities argued that

contracts should

be let which would provide useful job

training for the inmates. This argument challenged a

prison practice of making contracts

which returned the greatest profit to the prison.

32. Annual Report of the Directors

and Warden of the Ohio Penitentiary, 1873 (1874), 29-32;

ibid., 1875 (1876), 6-8.

248 OHIO

HISTORY

Warden G. S. Innis appealed to the

legislature for funds to replace poorly ventilated

cells which he called "abominable,

a disgrace alike to the State and the civilization

of the age." In 1875 Innis repeated

his request and added that many of the old

cells were infested with bedbugs and

other insects which made hygiene impossible,

and overcrowding again strained the

prison's physical facilities. Between 1872 and

1876 the number of commitments increased

135 percent from 334 to 785 while total

prison population rose 68 percent from

867 to 1,456 by 1876. An old shop was

converted into a dormitory for 150 to

200 men, and in 1875 and 1876 new cells were

authorized to accommodate the overflow,

thus delaying the replacement of the older

cells.33

During this period prison officials

looked askance at reformers and showed no

evidence of applying innovative

measures. Referring to the Cincinnati and London

prison congresses of 1870 and 1872, the

prison directors observed in their 1872

report: "We are not aware that any

practical results have been attained by these

meetings, or that any benefit has been

derived from them unless they have aided in

directing public attention to this

subject." They suggested a meeting of wardens

which the directors said "would

proceed from experience and practical knowledge,

and therefore be safe."34

The following year the directors, who

did not acknowledge the existence of the

Irish system, repeated that the prison

reform congresses had had very little impact.

"Many plans which were discussed

have been tried and abandoned, and some were

so crude that no one will attempt them.

The only convention by means of which

good may be accomplished must be

composed of a few men of practical experience,

who can compare views without attempts

at oratorical display, or producing essays

for publication." Prison officials

were content to promote rehabilitation through

a regimen of "Christian

charity" and a discipline described by Warden Innis in his

report of 1873 as "kind and

paternal; strict . . but not tyrannical."35

Between 1872 and 1876 organized efforts

to reform the penal system persisted

despite the inertia of prison officials

and disbandment of the Board of State Charities.

In August 1874 a voluntary organization,

called the Prison Reform and Children's

Association of Ohio, was formed by Byers

and former members of the board. The

purpose of the association was to

improve "the structure, discipline and management

of our penal, correctional and

reformatory institutions whether in cities, counties or

state."36 The members

tried to achieve these objectives by dramatizing the deplor-

able conditions in the institutions and

their failure to rehabilitate criminals and

safeguard society. Most of the effort to

popularize the association's cause and to

generate public pressure on the

legislature to reform the penal system was left to

Byers. In 1875 he traveled throughout

the state collecting contributions for the asso-

ciation, inspecting institutions,

reporting their condition to church gatherings, and

urging his listeners to form local

prison societies to support prison reform.37 By the

33. Annual Report of the Directors and Warden of the Ohio Penitentiary,

1873 (1874), 39;

ibid., 1874 (1875), 14; ibid., 1875 (1876), 15, 16, 18; ibid.,

1876 (1877), 4-6.

34. Ohio Executive Documents, "Annual

Report of the Directors and Warden of the Ohio

Penitentiary, 1872" (1873) XXXVII,

Part I, 553.

35. Annual Report of the Directors

and Warden of the Ohio Penitentiary, 1873 (1874), 26-29,

32: ibid., 1874 (1875), 21.

36. "Proceedings of the Prison

Reform and Children's Aid Association," Collection 142, Box

21, Janney Family Papers, Ohio

Historical Society.

37. Dr. Albert G. Byers, Diaries,

Collection 156, Box 5, Byers Family Papers, Ohio Historical

Society. See also Scrapbook, ibid.,

Box 4.

|

fall of 1875 Byers believed that socially and politically influential persons in the state were embracing the association's cause. The election that year of Rutherford B. Hayes as governor increased Byers' optimism because of Hayes' sympathy with penal reformers. In April 1876 Governor Hayes and the General Assembly responded to the Prison Reform and Children's Association's work by reestablishing the Board of State Char- ities. The new board's powers, like its predecessor's, were limited to inspection of prisons and giving advice on ways and means of reforming the system. In its annual reports between 1877 and 1883 the board renewed demands for state supervision of jails rather than leaving treatment of those guilty of minor offenses to "county authorities who cannot properly discharge such duty." It revived earlier plans for houses of detention for persons awaiting trial, district workhouses for minor of- fenders, adaptation of the Irish system, enforcement of reformatory rather than puni- tive discipline, an end to contract labor, and it recommended construction of a refor- matory for young offenders and the indeterminate sentence. Two new proposals were added to the board's program by Roeliff Brinkerhoff, a lawyer and banker from Mansfield who had joined the board in 1878 and had be- come an active lobbyist for his fellow reformers and a popularizer of a number of English penal innovations. He became familiar with English practices through extensive correspondence with Barwick Baker, a Gloucestershire squire and magis- trate who was one of the founders of the English reformatory system. Between 1880 and 1883 Brinkerhoff became Baker's disciple and advocated adoption of the Glou- cestershire practices of longer sentences for repeating offenders and police supervi- sion of habitual criminals and those on probation. Brinkerhoff assured the Ohio legislature that these proposals which the board included in its 1880 report were not pious theories, but that they had been "tried upon a large scale and found to be of value in the treatment of crime," by reducing recidivism and protecting society.38

38. Ohio Board of State Charities, Annual Report for the Year 1877 (1878), 6-11; ibid., Annual Report for the Year 1879 (1880), 6-9; ibid., Annual Report for the Year 1880 (1881), 8, 16-25; ibid., Annual Report for the Year 1881 (1882), 8; ibid., Annual Report for the Year 1883 (1884), 17-20; Thomas Barwick Lloyd Baker to Roeliff Brinkerhoff, 1880-1885, Baker |

250 OHIO HISTORY

Even though the Board of State

Charities' program had merit, little was achieved

since it did not have the political

leverage necessary to effect reform. The board's

views and influence were only a fraction

of the competing and often conflicting in-

terests affecting the prison system.

Through a series of enfeebling compromises, the

board's demands for state supervision of

jails and construction of district work-

houses were circumvented. An 1880 act

which required local officials to submit

plans for new jails to the board for

suggestions failed to give the board power to

enforce its standards. Instead of

transferring supervision of jails to the state as the

board recommended, an 1882 act

authorized each county Court of Common Pleas

to appoint a board of visitors to

inspect all county charitable and correctional insti-

tutions. The five member board, three of

whom were to be women, was to inspect

the institutions at least once every

three months and "recommend such changes and

additional provision as they may deem

essential for their [the institutions'] economi-

cal and efficient administration."

The county boards' reports were to be submitted

to the clerks of Common Pleas and to the

State Board of Charities. A third act

dealing with local institutions was

passed on March 29, 1883. That act authorized

the commissioners of neighboring

counties jointly to build, manage and maintain

a workhouse for minor offenders. The

cooperative workhouse required the approval

of a majority of voters in the

participating counties. Upon approval by the voters,

county commissioners were to select a

site and levy a tax or issue bonds to build

the facility.39

The Board of State Charities evaluated

these legislative reforms of local penal

institutions in its 1883 annual report.

Referring to the 1882 act, the board pointed

out that only fifty of Ohio's

eighty-eight counties had a board of visitors, and it urged

that the appointment of visiting

committees be made mandatory. The basic weak-

ness of that law was not the optional

appointment of visiting committees; instead,

the act failed to give those committees

any power to enforce their recommendations.

That law like the 1880 act did not

incorporate the board's demand for state super-

vision of local jails. The 1883 law

authorizing district workhouses produced no

immediate results. The board observed

that "the difficulties of combining counties

for the location and government of such

work-houses are so great as to afford but

little prospect of any favorable

outcome." The board repeated its request that the

state build and manage district

workhouses.40 Thus, despite considerable legislation,

control over jails as well as their

deplorable condition remained virtually unchanged.

The board's efforts to recast the penal

system around its plans for rehabilitation

faced the continued resistance of prison

administrators who stressed the importance

of a self-supporting institution. Prison

officials also averred that the existing system

was humane and reformatory.41 In

1883, however, reporters from the Cincinnati

Enquirer disclosed that prisoners lived in a regimented,

monotonous, punitive and

dehumanized system which exploited their

labor to profit contractors and the state.

Papers, Hardwicke Court,

Gloucestershire, England. This correspondence has been microfilmed

and deposited at the Ohio Historical

Society. See also Roeliff Brinkerhoff, Recollection of a

Lifetime (Cincinnati, 1900), 257.

39. Laws of Ohio, 1880, LXXVII,

227-228; ibid., 1882, LXXIX, 107-108; ibid., 1883,

LXXX, 81-84.

40. Ohio Board of State Charities, Annual

Report for the Year 1883 (1884),

19-22.

41. Ohio, Executive Documents, "Annual

Report of the Directors and Warden of the Ohio

Penitentiary, 1880" (1881), XLV,

Part I, 9-21; ibid., "Annual Report, 1881" (1882), XLVI,

Part I, 234, 246-247; ibid., "Annual

Report, 1883" (1884), XLIX, Part I, 20.

Ohio Penal System 251

The reporters described what modem

sociologists call a "total institution" and "pris-

onization." In a total institution

an inmate's independence and identity are eroded

to child-like dependence through long

terms, coercion and punishment. Prisoniza-

tion occurs when the inmate is converted

into an automaton suitable for institutional

manipulation, conformity and control.42

Persons who resisted prisonization were

likely to become hardened inmates whose

bitterness erupted in aggression against

fellow convicts, guards, the institution

and eventually society. For a convict entering

the penitentiary in 1883 the process of

prisonization began with the reception pro-

cedure. After the chaplain recorded the

prisoner's vital statistics, the inmate's hair

was cropped "to the same length all

around," his facial hair shaved, he was given a

striped suit and his name was replaced

by a number. He was examined by a doctor,

bathed, assigned to a cell, and placed

in a work company according to his physical

classification, the requirements of the

contractors and the needs of prison.43

The prisoners' week followed a

meticulous schedule, resulting in a repetitious pat-

tern of controlled behavior. Visitors to

the penitentiary observed that long-term

convicts suffered a malaise, sometimes

referred to as prison sickness, from the

monotony, boredom and control. During

the winter months inmates were awakened

at 6:45 A.M. (5:15 in the summer). The

guards armed themselves with repeating

rifles, revolvers, or clubs shaped like

a walking stick with brass "ferrules" at each

end. At 7:00 the prisoners were counted,

formed into companies and marched lock-

step--a close order step with each

inmate placing his right hand on the right shoul-

der of the man ahead of him--to the bath

house. Following a quick wash the

men lockstepped to the dining hall where

they stood before assigned seats. At the

first bell the men were seated, and

after the second bell their caps were removed,

heads bowed and grace said by the

chaplain. Fifteen minutes later the bell was

rung again signaling the work companies

to lockstep to work.

The pressures of regimentation and the

climate of debasement permeated the

inmate's day. At 11:45 A.M. the men

lockstepped to the dining hall where they

repeated the morning ritual. Only the

food and presumably the prayer varied. Work

ended at 4:00 P.M. in the winter (6:00

in summer) with the men washing, lock-

stepping to supper, sitting, praying and

eating to the signal of bells. After the con-

victs were locked in their cells at 4:30

the guards made a head count, reported in-

fractions to officers, and inspected

shops for fires--"for convicts are an incendiary

set." At 9:00 trustees were locked

up and all lights extinguished. Night guards

moving "around on noiseless

feet" made periodic inspections. On Sunday mornings

the work regimen was replaced by a

religious one. Prisoners could attend mass at

7:30 A.M., a prayer meeting at 8:30, and

Sunday School at 9:30 which was taught

by volunteers. All prisoners except

those who had attended mass were required to

attend the 10:30 church services

conducted by the chaplain. The men spent the

remainder of the day confined to their

cells. The boredom was broken by requests

for a visit from the chaplain who

conversed "with them on religious topics, encour-

aging them to form good habits and wise

resolves."

42. Erving Goffman, Asylums (New

York, 1961), 3-124; Donald Clemmer, The Prison Com-

munity (Boston, 1940), 294-320.

43. The account of life in the Ohio

Penitentiary was made by two reporters from the Cin-

cinnati Enquirer who spent two

days inspecting the prison. They reported that contractors

paid the state from $.42 per ten-hour

day for "infirm convicts" to 86¢. All wages were turned

over to the state. Cincinnati Enquirer,

January 21, 1883.

|

No talking was permitted at work, at meals, or in the cells. Signals like an "up- lifted finger" were used to communicate the convict's needs. There was no overt evidence of repression or anything done "to injure a man's self respect ... except for the striped clothing of the men, the guards, and the apparent isolation of each man, the shops could not be distinguished from any other shop of the same char- acter." The prison's serenity and similarity to the outside society was a veneer con- cealing intimidation, repression and humiliation which authorities used to control inmates. As one guard put it, "A convict is like a rubber ball. He will stay as long as you press him down, but flies up when the pressure is removed. He must feel the pressure all the time." A scale of punishments was used to ensure conformity to penal authority. Priv- ileges were suspended and "good time" deducted for minor infractions. "Ducking" was used for recalcitrant inmates. The ducked convict was placed in a tub, blind- folded, his hands cuffed behind his back and water forced into his mouth and nose through a hose making breathing impossible. The prisoner was given doses "until his stubborn spirit gives in. Sometimes he loses consciousness and must be brought to." Officials denied any cruelty and stated that ducking "is nothing more than an involuntary bath." Hostile inmates were placed in solitary confinement.44 The expose of the penitentiary supported reformist claims that the prison's regime was not structured to rehabilitate criminals. Prison reformers and the Board of State Charities were, however, too weak by themselves to shake the entrenched penal sys- tem. Between 1877 and 1884 they therefore joined with those assaulting the con- tract labor system. The reformers wished to abolish the practice as well as to use the attack as leverage to recast the whole penal system. Opposition to contract labor had begun in the spring of 1877 when a house committee reported that leading manufacturers in the state objected to it because it crippled business and caused unemployment. The committee concluded that contract prison labor was "directly responsible" for a high percentage of wage reductions among "thousands of our mechanics during the past four years," and that contract labor pauperized "honest labor," thus contributing to an increase in crime. The committee report endorsed

44. Ibid.; a less charitable account of prison punishments was given by a former inmate. Cin- cinnati Enquirer, January 8, 1883. |

Ohio Penal System

253

the view of prison reformers who

testified that contract labor was incompatible with

rehabilitation programs and agreed that

neither profit nor punishment, but reforma-

tion "should be the paramount

aim" of prison discipline. The report urged that con-

tract labor be replaced by a new labor

system designed to train convicts in useful

trades.45

In February 1883 a bill to abolish

contract labor was introduced into the legisla-

ture. The bill was supported by the

Board of State Charities, most Democratic legis-

lators, a few Republicans and the

Knights of Labor. The contract labor question

was soon manipulated for political

advantage in Ohio's election year. Contractors

were reported "flying around in the

lobby, doing all they can to defeat" the bill.

Representative John F. Locke (R)

denounced the bill and alleged that it was

"backed by an inflammatory, a

Communistic movement." The bill was tabled that

winter amid Democratic charges of

Republican deception and betrayal of the work-

ingman. The Republicans tried to sustain

labor support by adding a plank abolish-

ing contract labor to their platform,

but the Democrats pressed their attack with

reports that the Republicans were in

league with the contractors.46 Prison officials

stood firmly by the system with Warden

Noah Thomas warning that the abolition

of contract labor would be

"disastrous to the financial interests of the state, without

affording relief of any kind to any

class of society."47 Before the fall election Roeliff

Brinkerhoff even joined in criticizing

the labor bill because it did not include the

reform package supported by the board.

In a speech before the National Conference

of Charities and Correction, Brinkerhoff

called the agitation for an end to contract

labor "ill-considered clamor"

and useless unless accompanied by implementation

of features from the Irish system.48

The 1883 October election of a

Democratic governor, George Hoadly, and a

Democratic house set the stage for the

debate on contract labor and reorganization of

the penitentiary and the appointment of

a new staff with the present management

"cleaned out from top to

bottom." In early January 1884 Representative Allen 0.

Myers (D) of Franklin County introduced

a bill to abolish contract labor and recast

the penal system to conform with the

recommendation of the special legislative com-

mittee investigating contract labor and

some of the reform programs supported by

the Board of State Charities. The Myers

bill replaced contract labor, which was

scheduled to expire by 1887, with a

state account system. Under the new system,

managers would be empowered to purchase

machinery, tools, and material to pro-

duce convict-made goods for state

institutions and public sale. Prison industries

would be restricted to prevent

"unfair" competition with private manufacturers and

were required to train convicts in

employable skills. The bill proposed to end the

spoils system by requiring popular

election of prison managers. The measure

stressed rehabilitation by authorizing

judges to apply the indeterminate sentence

which set a minimum and maximum term and

permitted prison officials to release

convicts upon proof of reformation any

time after serving the minimum sentence.

45. Ohio, House Journal Appendix,

1877, 3-18.

46. The bill was introduced by

Representative William Peet (R). Cincinnati Enquirer, Feb-

ruary 13, March 5, 22, 30, September 10,

1883; Cleveland Plain Dealer, March 31, 1883. The

Plain Dealer asserted that the Republican strategy was to put off

the bill in the legislature with-

out losing labor votes and then kill it

after the fall elections.

47. Ohio, Executive Documents, "Annual

Report of the Directors and Warden of the Ohio

Penitentiary, 1883" (1884), XLVIII,

Part I, 33.

48. Ohio Board of State Charities, Annual

Report for the Year 1883 (1884), 25-36.

254

OHIO HISTORY

To symbolize the transformation of the

prison from a punitive, custodial, profit

making institution to a reformatory,

Myers proposed that the penitentiary's name

be changed to the "Ohio House of

Detention for the Reformation of Criminals."49

The fusion of Democrats, Republican

reformers, workingmen's representatives

joined by the governor and the Board of

State Charities faced a dwindling opposi-

tion of contractors, prison officials

and their political allies. Supporters of the Myers

bill praised it as a non-partisan

measure which incorporated the best features of

several penal systems and provided the

"most practical civil service reform." Ac-

cording to the Cleveland Plain

Dealer, the bill correctly recognized that crime must

be treated "as a disease." The

state must be permitted through the indeterminate

sentence to hold a criminal until the

"disease is cured." The bill "goes a great way,

if not the entire distance to a solution

of the problem as to what is necessary to pun-

ish and reform criminals, protect

society and lessen crime."50

Reformers discredited the opposition by

exposing abuses in the penal system

and the obstructionist policies of

prison officials. Official reports from the peniten-

tiary were ridiculed for trying to make

the prison appear "only a step removed from

heaven itself." Published testimony

by a former inmate, given before a legislative

investigating committee in January,

asserted that the prison's management "could

not possibly be worse"; that

officials were only interested in profit; that the prison

was under the "absolute

control" of the contractors; and, that inmates were "tor-

tured" if they did not meet

production quotas. The witness concluded that morals,

health and rehabilitation were

sacrificed for profits, and that the prison was causing

pauperism among free laborers. Warden

Noah Thomas subsequently refused to

permit a legislative investigating

committee to interview inmates unless he were

present and determined the questions to

be asked and answered. Thomas' obstruc-

tion raised a howl of indignant protests

among reformers and further eroded support

for the existing system.51

The most difficult obstacle facing

reformers was the accusation that their intent

was to coddle inmates. In an attempt to

arouse retributive passions in the public,

opponents of the Myers' bill charged

that the measure made prison a "desirable"

place and eliminated it as a

"terror to evil doers." Reformers conceded that the

public refused to accept the proposed

change in the name of the prison, but assured

the bill's supporters that "there

was nothing in the bill to warrant the rumor that the

author [Myers] would array the prisoners

in purple and fine linens, or feed them on

chicken pies."52

On February 27, 1884, debate on the

Myers bill "packed the hall with visitors,

brought out strong speeches. . . and

caused a general field day of excitement."

Although the name of the penitentiary

and the method of selecting the new govern-

ing board were not changed, amendments

to weaken the bill were defeated as the

measure passed the house by a party

vote.53 The bill, which passed the senate on

March 24, abolished contract labor,

authorized the state account plan, required all

49. Cincinnati Enquirer, October

15, 1883, January 9, 10, 1884. The legislative committee

investigating contract labor was

established in 1883 after the Peet bill was tabled. Allen O.

Myers served as chairman of the

legislative committee on prison reform. His interest in reform

resulted from his experience as a

convict. Brinkerhoff, Recollections of a Lifetime, 274.

50. Cleveland Plain Dealer, February

19, 26, 1884.

51. Cincinnati Enquirer, January

28, 29, 1884. The Cincinnati Enquirer alleged that the legis-

lature had been obstructed by penal

officials. In addition, the officials, contractors, and their

political allies subsidized press

attacks on the prison reformers. The legislature responded to the

obstructions by passing a resolution

empowering its committee to make investigations.

52. Ohio State Journal (Columbus), January 29, 1884; Cincinnati Enquirer, January

28, 1884.

Ohio Penal System 255

prisoners under age twenty-two to be

"employed at handwork exclusively, for the

purpose of acquiring a trade," and

provided that inmates keep up to twenty percent

of their earnings. The prison act

removed the spoils system through the appoint-

ment of five prison managers whose terms

of office ranged from one to five years,

a four year term for the warden

"during good behavior," and a provision that "no

office or employee shall be appointed or

removed for political or partisan reasons."

The law authorized the Board of Managers

to grant parole to reformed inmates and

set the regulations for conditional

release. Parolees remained under the legal cus-

tody and control of the board.54

Additional legislation passed in April

incorporated more reforms advocated by

the Board of State Charities. The

criminal justice system was made a part of penal

rehabilitation programs by authorizing

the indeterminate or reformatory sentence.

The law was necessary to implement the

parole provisions of the March act. The

Board of Managers at the penitentiary

was empowered to "make such rules and

regulations for the government of the

prisoners as shall best promote their reforma-

tion" by establishing a program of

classification, grades and marks like those applied

in the Irish system to measure and guide

rehabilitation. The legislature also author-

ized the construction of an intermediate

prison funded by a ten percent appropria-

tion--or an estimated $200,000 per

year--from the revenues from the Scott tax

on the liquor traffic. The Board of

State Charities had warned that unless an inter-

mediate prison for young offenders was

built penitentiary rehabilitation programs

would fail.55

The reform legislation adapted certain

features of the Irish system which had

long been urged by the board. Within the

penitentiary three grades were created

by the Board of Managers. All prisoners

entered at the second level and were pro-

moted or demoted according to their

conduct. Prisoners within the grades were

distinguished in appearance and pay. The

men in the first grade wore blue suits.

Convicts in the second grade wore gray

suits, and the traditional striped suit was

worn in the third grade. Inmates in the

first and second grades moved about in a

military march, while the lockstep was

used in the third grade "as a matter of pun-

ishment." Prisoners in the first

grade were paid eighty cents per day, while second

and third grade convicts received sixty

and forty cents per day respectively.56 While

53. The vote was 57 yea, 39 nay.

Cincinnati Enquirer, February 27, 28, 1884; Ohio State

Journal (Columbus), February 28, 1884. Representative Peet (R)

reintroduced his bill to

abolish contract labor. The bill was

ruled out of order. Peet then voted against the Myers bill.

Peet's vote is further indication of the

partisanship involved in the measure.

54. Laws of Ohio, 1884, LXXXI, 72-76. This legislation can also be found in

Ohio, Executive

Documents "Annual Report of the Directors and Warden of the

Ohio Penitentiary, 1884"

(1885), XLIX, Part I, 335-341.

55. Ibid. Although the prison reform acts were passed at

different dates in the spring of 1884,

they were all classed under the same act

in Laws of Ohio. The Scott law provided for an annual

tax of $200 on all places where liquor

was sold at retail. Philip Jordan, Ohio Comes of Age

(Carl Wittke, ed., The History of the

State of Ohio, V, Columbus, 1943), 177. The Cincinnati

Enquirer estimated

that the Scott law would yield $2,000,000 in revenues per year. The penal

system's share of that income would have

been $200,000 per year according to the revenue

formula worked out in the March 27, 1884

law. Cincinnati Enquirer, February 5, 1884, June

12, 1885.

56. Ohio, Executive Documents, "Annual

Report of the Directors and Warden of the Ohio

Penitentiary, 1884" (1885), XLIX, Part I, 193-194;

Directors Journal (The Ohio Penitentiary),

494, Ohio Historical Society Archives.

This journal, December 3, 1878 to May 6, 1886, is the

only surviving record of the penitentiary's directors

meetings. The journal contains financial

accounts, reviews of appealed

infractions, lists of visitors, appointments, resignations, and imple-

mentation of legislative acts dealing

with the prison. For sections dealing with the implementa-

tion of the 1884 prison acts, see pp.

465-502.

256 OHIO

HISTORY

the number of grades and the principle

underlying the system were borrowed from

the Irish system, the Ohio adaptation

omitted the initial phase of eight months in

solitary confinement. The Ohio version

placed all grades in one penitentiary rather

than using separate and specialized

institutions for each grade of prisoner as in Ire-

land. A mark system borrowed from the

Elmira, New York, Reformatory, but also

based on the experiences of the Irish

system, was applied to measure conduct and

to determine promotion or demotion in

grade. Each prisoner was given a ledger

where his marks were recorded each

month. Under this system each prisoner could

receive a maximum of nine marks per

month--three for demeanor, three for labor

and three for study. "Good

time" deductions and parole of prisoners confined under

the indeterminate sentence were gauged

by the graded and mark systems.57

One major part of the Irish system that

was not adopted was the intermediate

prison concept. Within the Irish system

the intermediate prison was to serve as a

kind of halfway house for inmates in the

highest grade who were ready for release.

The Ohio legislation called for an

intermediate prison, but the purpose of this new

prison was to incarcerate young adult

first offenders, as recommended by the State

Board of Charities which followed the

example set by Zebulon Reed Brockway

at the Elmira Reformatory.58

The legislative successes in 1884 were

followed by a reevaluation of the entire

penal question in 1885 because much of

the reform package failed to materialize.

The state's meagre allocation of $10,000

was inadequate to finance the new con-

vict labor programs which required an

estimated $250,000 to $700,000 to imple-

ment. In addition, legislators were

turning to retrenchment policies because of a

drop in the economy.59 A

further blow was delivered to the reforms when the Scott

tax on the liquor traffic, part of which