Ohio History Journal

ANNUAL MEETING OF THE BOARD OF TRUS-

TEES OF THE OHIO STATE ARCHAEO-

LOGICAL AND HISTORICAL SOCIETY.

Museum and Library Building,

April 25, 1933.

The Board of Trustees of the Ohio State

Archaeo-

logical and Historical Society met in

annual session in

their room in the Museum and Library

Building of the

Society at 2 o'clock p. m., Tuesday,

April 25, 1933. The

meeting was opened by President Arthur

C. Johnson.

The following members were - present:

President

Johnson, Dr. Thompson, Messrs.

Florence, Miller, Spet-

nagel, Goodman, Miss Bareis and Mrs.

Dryer. Director

Shetrone and Secretary Galbreath were

also present.

On motion of Dr. Thompson, seconded by

Mr. Mil-

ler, the reading of the minutes of the

annual meeting of

the previous year was dispensed with,

as that had been

included in the Secretary's report.

The election of officers and members of

the staff

was declared in order. On motion of Dr.

Thompson,

seconded by Mr. Spetnagel, the officers

of the Society

were reelected for the coming year and

the members of

the staff at salaries to be fixed

within appropriations

available by the General Assembly.

The President called for the reports of

two commit-

tees, one the Committee to Consider the

Scope of the

Activities of the Society, of which Mr.

Sater is chair-

man, and the other on Membership and

Dues, of which

(358)

Annual Meeting of the Board of

Trustees 359

Miss Bareis is chairman. Miss Bareis

reported briefly

in favor of postponing the report of

her committee

because of the inability to have the

views of one of the

members. In the absence of Mr. Sater,

both committees

were continued.

Secretary Galbreath drew attention to a

request from

Dr. Carter, Editor of the Territorial

Papers in the De-

partment of State, Washington, D. C.,

asking for an

endorsement of the project in which

that department is

engaged, namely, the publication of the

Territorial Pa-

pers so far as they are available and

unpublished. On

the suggestion of President Johnson,

the preparation of

such a letter was entrusted to the

Secretary of the

Society and he was authorized to write

accordingly.

There being no further business the

Board of Trus-

tees adjourned.

360 Ohio

Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

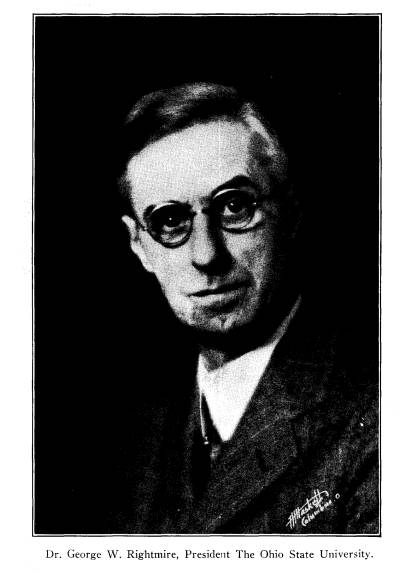

AFTERNOON SESSION

President Johnson called the meeting to

order at

2 o'clock. The audience was

delightfully instructed and

entertained by Dr. George W. Rightmire,

who delivered

the following timely address on the

subject, THE HIS-

TORIAN AND HIS MATERIALS:

I should like to open my remarks with a

quotation from an

Italian historian, Beccari. Long ago he

wrote, "Happy is the

country without a history."

To him history meant military campaigns,

political upheavals,

international intrigue and social

unrest. And generally that is

what it had meant, and if, as he saw it,

a community should have

none of these shaking experiences to

chronicle it would have no

history, and therefore, must be happy.

But that conception of history is

entirely inadequate; history

comprehends those occurrences but it

means much more. Essen-

tially it is an attempt to recreate the

past--the whole past, and it

goes on as a natural human endeavor.

Men in the sundown of life turn aside to

recall and to recite

their own deeds and experiences which

rise up vividly out of the

past; they desire their children to know

what manner of men

they have been and they find a peculiar

satisfaction in their own

achievements which, through the mists of

time, seem imposing

and significant. There is also a

half-expressed desire to instruct

those who come after and furnish them an

example; what other

motive could probably have prompted

Franklin in writing his

intimate biography, or Depew in his My

Memories of Eighty

Years? Some such urge impels men to write also about others;

future generations should know of the

exploits of an Alexander

or a Genghis Khan, the religious

motivation of a Luther or a

Wesley, and the social transformations

activated by a Florence

Nightingale or a Frances

Willard--although the Caesars and the

Napoleons have held most of the stage!

As men have chronicled contemporary

events or have recre-

ated the men and the deeds of a bygone

age, they have, of course,

wanted to leave a personal memorial.

They anticipated a feeling

of satisfaction in the association of

their names with great men

or great movements. Hereafter men may

often speak not of Wash-

ington, but of Weems's Life of Washington!

Not of Lincoln, but

(360)

|

|

|

(361) |

362 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

of Nicolay and Hay's Lincoln! Not

of the development of the

western country, but of Roosevelt's Winning of the

West. Who

thinks of Greece without Grote, or Rome without Gibbon

or

Mommsen, and so on with perhaps some

illustrations closer home?

But writers of history have been chiefly

actuated by these

purposes: they become impressed with the culture of an

age or a

people and want their own and future generations to

have this

inspiration for their guidance and improvement.

Also, they delight in dissecting human

motives, in analyzing

human conduct, in probing the influences which, for one

hundred

fifty years prompted men to venture

their fortunes and their

lives in the Crusades, or for an equal

period of time to push back

with an unbroken advance the line

"Where the West begins" in

these United States!

Also, they have been absorbed in tracing

the course of civili-

zation from its beginnings in the Orient

through its spread over

the western world, and the checkered

experiences which have

marked its development.

Also they have a curiosity about our

status among the na-

tions, and a natural pride in showing

that we are the deserving

beneficiaries of past improvements, are

an outstanding people,

and are with intelligence and confidence

passing on the torch of

human perfection.

These are all worthy purposes; they

enable the present to

utilize the substance and to appropriate

the culture of the past,

to promote confidence and inspire a vision

of the future. As the

historian conducts our steps through

these mazes of human ex-

perience he finds a horrible example of

how it should not be done,

and for our advice he hangs a placard on

Carthage bearing the

warning, "Cave Canem," or in

the more modern fashion of cen-

tral Europe, "Wehrt Euch." On

little Switzerland's career, he will

hang the tag, "Well Done"; on

the Great Wars he will inscribe,

"Never Again"; mankind's

failures and misfits he will decorate

with the wish, "Requiescant in

Pace"; and all genuine efforts to

reach international good will and a

spirit of mutual interest, he

will enthusiastically inscribe in

illuminated letters, "Gloria in

Excelsis"!

How will the historian proceed in

unrolling the past, in analyz-

ing its features and in organizing it

into a truthful and moving

recital? Let the historian himself

answer. Rene Fulop-Miller in

his recent single volume on the history

of The Power and Secret

of the Jesuits uses an appendix of bibliography spread over

twenty-five pages, almost if not

entirely composed of book titles.

Since the order has been in existence

four centuries, and has had

the most profound influence all around

the globe and has always

Annual Meeting of the Board of

Trustees 363

been militant, this array of authorities

is not surprising. That

Miller should have been able to refer to

so many volumes in

diverse languages written in widely

separated periods, shows the

genius, the industry, and the good faith

of the modern historian.

Gibbon in his monumental work cites all

his authorities in his

footnotes, and what a wealth of

historical material he discloses!

Source material consisting of public

documents, official decrees

and communications, correspondence,

speeches, literary works,

manuscripts, books, memorials,

memorabilia brought together

from the countries stretching from the

Indus River to the Atlantic

Ocean, and from the Upper Nile to

Britain, reveal a degree of

scholarliness, industry, and devotion

almost incredible. But in

Gibbon's time it was not fashionable to

add an appendix of

authorities and so we must follow his

search for information

through his six big volumes, page by

page. If he had chosen to

group his materials in one place under

the favorite, present-day

title, "Bibliography," I do

not doubt it would cover fifty pages.

Gibbon devoted twenty years to this

task.

A very modern writer, who deals with

Rome in a manner to

be mentioned later, cites his

authorities in his text and footnotes

but throws out this consoling hint,

"I am aware that the bibliog-

raphy is far from complete. As a rule I

have abstained from

piling up references to antiquated books

and articles, but have

cited only those which I have carefully read and on

which my own

information is based; those which did not help me are

not quoted

as being unlikely to help my readers.

.. Most of my notes are

not of a bibliographical character. In

those sections where I have

found no modern books to help me and

where I have had to

collect and elucidate the evidence myself, I have

generally inserted

some notes which are really short

articles on various special points

and of the nature of excursions or

appendices. Some of these

notes are long and overburdened with

quotations; only specialists

are likely to read them in full."

Let me quote further for our

enlightenment about the his-

torian's method: "The illustrations which I have

added to the

text are not intended to amuse or to please the reader.

They are

an essential part of the book, as

essential, in fact, as the notes

and the quotations from literary or

documentary sources. They

are drawn from the large store of

archaeological evidence, which

for a student of social and economic

life, is as important and as

indispensable as the written evidence.

Some of my inferences and

conclusions are largely based on

archaeological material."

This is an illuminating portrait of the

keen historical student

at work. As we read we recall other historians who do

not seem

to be so discriminating in their array

of sources. One is reminded

364 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

of the maker of law books who states a

principle of law and

refers to a footnote where numerous

cases are cited and, when

they are studied individually, some of them are found

not to touch

the principle, or to deny it. It is a

trick of law writers to pick a

whole block of cases out of a brief in

some Court report and adopt

them all without serious study. Thus

they may make a showing

of profound learning which turns out to

be a thin shadow. Some

of our historians are equally generous

and undiscriminating.

Now, let us turn to a late history of

the early period of our

political life, Jefferson and

Hamilton, by Claude G. Bowers. In

dealing with these characters in a

delightfully refreshing manner,

he finds his way through a six-page

collection of historical ma-

terials including books, pamphlets,

newspapers and magazines

which he says are "cited or

consulted." The pamphlets and news-

papers are contemporary. I should like

to state in his own words

how he uses the newspapers as source

material:

"A liberal use has been made of the

newspapers of the period;

not only the descriptions of actual

events, but of the false rumors

and stories that entered into the

creation of the prejudices that

always play their part in the affairs of

men. In determining why

a given result was forced by public

opinion, it is no more necessary

to know what the truth was than

to know what the people who

formed that opinion thought it to

be."

This statement embodies a great truth

which we must daily

apply if we would understand public

movements in our democracy.

To understand the political scene Bowers

takes the reader into

struggles in Congress, the bickerings in

the streets, coffee-houses

and taverns, mobs and mass-meetings, and

behind the closed

doors and shuttered windows of

"society." He says he is trying

to depict these two men and their

associates as they really were

in the heat of controversy; "to

paint them as men of flesh and

blood with passions, prejudices and

human limitations; to show

them at close quarters wielding their

weapons, and sometimes, in

the heat of the fight, stooping to

conquer; and to uncover their

motives as they are clearly disclosed in

the correspondence of

themselves and their friends. This has

necessitated the abolish-

ment of some fashionable myths, when

myths have obstructed the

view of truth." "The dignified

steel engravings of the participants

with which we are familiar give no

impression of the disheveled

figures seen by their contemporaries on

the battle-field." The pur-

pose of the author is "to make the

men of the steel engravings

flesh and blood."

If this discriminating probing is needed

to present the true

history of men and events only a century

and a quarter away in

a country where the press and the

scholar have been uncensored,

Annual Meeting of the Board of

Trustees 365

the problem undertaken by the historian

of early colonial times,

or the Renaissance, or the late days of

the Roman Republic when

men's passions were inflamed and

intrigue ran riot, or the more

recent happenings in Russia, is almost

bewildering.

The current newspaper is difficult

material for the historian

of military and political events, but

Bowers is a newspaper writer

and is endeavoring to translate familiar

materials into historical

narrative, and no one will deny that he

paints a fascinating picture.

He pursued the same methods with the

same types of materials

in writing The Tragic Era or the Revolution

After Lincoln, in

which he traced the course of reconstruction.

I mention this to introduce another kind

of contemporary

material, in this instance used by no

one before, but of rare value.

This is the diary of Representative

George W. Julian of Indiana

which Bowers used in the unpublished

manuscript. It sheds light

on motives and admits the reader to

private conferences among

the great actors of the times. Generally

though, there is no satis-

factory way of checking on the

reliability of a diary since it is

made up of ex parte statements,

and its use will depend upon the

judicial temper of the writer who

appears somewhat in the role

of a private reporter.

I am mentioning Bowers at some length

because he makes

conspicuous and, I think, successful use

of voluminous newspaper

files for political history of the most

moving sort. It is refractory

material for this purpose except in the

hands of an expert such

as Bowers; we could cite some rather

conspicuous instances of its

use where the resulting history of the

United States is practically

a compilation of quotations treated as

equally important and trust-

worthy! But for an economic or

commercial or social history,

the newspaper has large possibilities. Professor

Schlesinger cre-

ated a mild sensation among American

historians twenty years

ago by presenting a thesis on the

influence of commercial or busi-

ness relations and practices on the

American Revolution, as shown

in contemporary newspapers. He was

interested in dealing with

social factors as influencing political events and

found them con-

tinuous and powerful.

In recent years there has been a

pronounced trend toward

social history as distinguished from

political or military or con-

stitutional history. This calls for a

searching of all the influences

which make the life of a people what it

is at any given time--the

state of the arts, of business, of

industry, of the amusements and

dissipations of a people, of its luxuries, of its

facilities for trans-

portation and communication--the live historian will

utilize them

all and he must find them in the

schools, in the factories, in the

stores, the libraries, the homes, the

museums, and the archives.

366 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

Verily, to write a good history, the

historian must be a genius as

well as an honest and industrious man!

Every historian should become familiar

with these materials

existing in the period studied, for the sake at least

of perspective;

he should appreciate the influences at

work whether he purposes

writing about them all or not. He may

choose a thesis as Adams

does in The Epic of America and

in The March of Democracy,

and as Parrington does in his unfinished

social history entitled,

Main Currents in American Thought. Adams sets out to show

the effect upon our national development

of the American dream

of equality of individual

opportunity--the doctrine of the equal

chance for all--and in tracing the

fortunes of this philosophy he

finds the existence of the frontier a

dominating physical and social

factor, and its non-existence for the

past third of a century a like-

wise powerful factor in creating the

very different social condi-

tions we are living in today. He must

recognize unlimited freedom

of operation to every social influence

in the community in select-

ing his materials and in grouping them

about his thesis; he be-

comes a philosopher of history, and

therefore, exercises a type of

discrimination in the choosing and

evaluating of materials and a

quality of thought in developing his

thesis not needed by the

narrative historian, or by one who is

attempting to present a gen-

eral outlook. The historian who ventures

into this type of his-

torical writing is dealing with the

composition of forces and is in

grave danger of overstatement.

Now let us glance at some of the reasons

why the history

of a period is written and rewritten.

Historical materials are not

always on tap, sometimes they are by the

will of the owner not

to be opened for a number of years, as

in the case of private let-

ters, documents and diaries. After the

World War an eminent

English actor therein died leaving a

large collection of such

sources of information about his times

and his activities and the

actions of contemporaries, but his will

provided that they should

not be opened for fifty years. Doubtless

other important papers

will not be released for years; and

although we today think we

know all about the Great War, yet of its

real causes and the

significance of many of its movements,

our remote descendants

will know much more than we. Possibly we

do not envy them that

larger information. As the archives are

opened and new letters

and documents are revealed the history

of that cataclysm will be

written and rewritten, each time with a

more complete conception

possible.

We recall Bowers' experience with

Julian's diary sixty years

after the events of reconstruction. I

know some of the diffi-

culties with which earlier students of

this period struggled; the

Annual Meeting of the Board of

Trustees 367

University, thirty-five years ago, very

generously gave me the

Master's degree for studies relating to

the XIVth Amendment.

I had access to the State Library and

the University Library and

exhausted the materials so far as I could locate

them--practically

all in Congressional records and government documents

such as

the investigations and official reports

of Carl Schurz and General

Howard. It was a thorny and

unsatisfactory field. A student of

that subject today would find a wealth

of material made available

all through the South and in newspaper

files and studies and in

released writings and documents. I don't

know that I could do

any better with the subject today, but a

real historian would find

his way made easy by the materials

uncovered since that time!

The American conception of our

Revolutionary War has un-

dergone a radical change in the last

thirty years. I believe the

needed enlightenment came first through

Trevelyan's study of

that era. We know that a dominant

political minority in England

overrode the best thought of the time

about the colonies and

blundered into and through the

Revolution. For a century the

jingo could always get a local response

by twisting the lion's tail

and we passed through a long period of

rabid chauvinism. But

the discovery of much source materials

and its analysis and spread

have removed old misunderstandings. We

have called this opera-

tion "debunking" history and

there is pretty general agreement

that the "debunked" history is

better.

Further, in the light of rather recent

discoveries and

studies, we wonder how Thaddeus Stevens

rose to the dictator-

ship in post Civil War affairs; we

wonder whether we have ever

understood President Grant; we have

begun to look upon Andrew

Johnson as a capable but much persecuted

and misrepresented

man. It has taken over sixty years to

clear the murky atmos-

phere that hung over the land for a

dozen years after the death

of Lincoln. And the constant search and

probing into historical

materials by historical students hunting

the truth have brought us

into an era of enlightenment about the

rebellion and its terrible

political aftermath.

I want to emphasize the point that the

discovery of new his-

torical materials or the changed

view-points with reference to the

meaning of known materials, concerning a

period of time, pre-

sents the history of that time in new

aspects; indeed it makes it

appear like a different history. But I

do not want to dwell upon

this point unduly. However, some further

illustrations come to

mind which will show how uncertain

historical conclusions must

always be.

Lamb's recent volumes on the Crusades

have brought forward

some Islamic sources of the history of

that prolonged movement

368 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

and we get a different understanding of

some of its later develop-

ments. To go still further back, I

suppose we have generally

thought that the history of the Roman

Empire was completely

told by Gibbon. Not much fault has been

found with this history

in the century and a half since he wrote

it, but in recent times we

have been learning that there were

sources which he did not use

and about which he probably did not

know, and it may be of

whose importance he was not convinced.

But recently the Russian scholar,

Rostovtzeff, professor at

Yale University, has written the Social

and Economic History

of the Roman Empire; he says these phases of Roman life have

not been adequately treated in other

histories which deal pri-

marily with military and political Rome.

There is a good deal

of the economic and social in Gibbon's Rome,

but nothing com-

parable with Rostovtzeff's treatment. He

was impressed with

the knowledge to be gained from the

study of memorials, mosaics,

friezes, stelai, coins, antiquities in

many museums, and the find-

ings in numerous widely separated

excavations. From these

materials, records and manuscripts he

recreated the commerce

of the times, the trade routes, the

industries of many communi-

ties, domestic customs and business

practices. These bear heav-

ily upon political and military events

and international relations,

and at that point he fills the picture

of Roman life. He sheds

a brilliant illumination upon the

character and significance of

antiquities; no age seems too remote for

further study in the

light of museum treasures, excavations,

and manuscripts lately

discovered. We recall distinctly the

significance of the late dis-

coveries in the tomb of Tutankhamen and

the wealth of materials

brought back a few years ago from Egypt

by the exploring

parties from the Metropolitan Museum.

May I give a further illustration

bearing upon this same

thought, that no age can write its own history, and it

may be

many ages before the complete history of any period may

be

written? In 1265 the Englishman,

Bracton, completed a very

great book on the customs and laws of

England written in the

Latin language. Sundry attempts were

made to translate that

work and the one which obtained the

widest circulation was that

by Sir Travers Twiss about 1860. Lawyers

and students felt

that Twiss had made many mistakes

because of misunderstand-

ing Bracton's statements and their

import, yet they were not able

to correct them with any assurance.

About 1885 a young Rus-

sian student, Vinogradoff, came to

England to make a special

study of the feudal age in England. He

was interested in the

system of land-holding and cultivation

there in the twelfth and

thirteenth centuries because he believed

that these might very

Annual Meeting of the Board of

Trustees 369

closely resemble the system of

land-holding in Russia of his

time. He wanted to get the historical background, if

there was

one, and he made some very penetrating studies of land

tenure

in England through the use of the

ancient documents. His

ability to find and translate these

documents was so remarkable

that he attracted the attention of the

preeminent legal scholar,

Maitland, who was devoting himself to a

study of the old year-

books and other early legal documents in

English history.

Through Maitland's influence Vinogradoff

became interested in

these legal documents and one day while

rummaging about in

the British Museum he came upon a bundle

of law cases of the

thirteenth century and at once believed

that he had fallen upon

Bracton's notebook. Nobody had ever seen

this document, at

least had ever identified it, and so

Vinogradoff made a very

remarkable discovery of notes on the

cases which Bracton had

discussed in his monumental law book of

1265, and this threw

a flood of light upon Bracton's text

which had not hitherto been

possible. Thus was a very important

phase of the life of the

thirteenth century revealed six

centuries later, and the legal his-

tory of that time has since been written

with a higher degree of

knowledge and intelligence than was ever

before attainable.

As the centuries pass away documents

become scattered or

destroyed or lost, and this was

especially likely to happen before

the age of printing. From various statements

gleaned here and

there through legal writings, it was

believed that we did not have

all of Bracton's manuscripts and we had

some reasons to be-

lieve also that, as they had become

scattered, the best manu-

scripts of Bracton had not come down to

us. Careful searches

had been made through the British Museum

and through the

private libraries of various members of

the English nobility, but

yet inquiring minds in the twentieth

century were not satisfied

with the results.

Professor George Woodbine of Yale University

became inter-

ested in the sources of Bracton's

materials and for twenty years

he has been going to England to study

available manuscripts

and has unearthed a few in the old

mansion-houses of the an-

cient nobility. Several most important

manuscripts have thus

been brought to light and have been

photographed and brought

back to this country where Woodbine has

given them critical

study. The result is that he has already

issued two volumes of

a proposed six-volume compilation of the

texts of Bracton,

with a reconciliation so far as possible

of the aberrant texts, and

a translation based upon all these

sources of information is

forthcoming--all of which promise to

make Woodbine's work

of the greatest historical value. What

he is doing is, through

Vol. XLII--24

370 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

recent discoveries of ancient documents,

to shed the light of mod-

ern research, scholarship and devotion

upon the legal practices

and conditions of a time six centuries

remote. These illustra-

tions might be repeated almost

indefinitely.

And now let me show how the age in which

the historian

writes and the age about which he writes

are both reflected in

his writing. The historian is always put

to it to determine which

is the best material available, and

usually the materials are in

quantity. Which should he use? This depends upon which ma-

terial he thinks reflects the

life of the times and its political and

military activities most effectively,

and in making this decision

he will operate upon principles of

relativity. He may not know,

there may be nothing to show clearly,

what forces were the

most powerful in shaping the period

about which he is to write,

or what elements entered into the

composition of these influential

forces. He must, therefore, select, and

to do so must put his

own appraisement upon the materials at

hand. His appraisement

will be colored by the thinking of his

times, by his training, by

the evaluation of social and political

forces current in his own

experience. The genius and culture of

his own age, therefore,

enter, and it may be without formal

purpose on his part, into

his study and selection of the materials

of the past age, and it

is easily conceivable that much may be

neglected which a writer

of a different type, or of another age,

might regard as of ex-

treme importance. That is another reason

why history is writ-

ten and re-written. A history of Rome in

1933 would be done

very differently from a history of Rome

in 1774 or any time be-

tween now and then. We are bent now upon

digging into the

social forces and manifestations of a

period, and these are often

hard to come at, but we find them so far

as possible and they

color our historical writings. We may

misconstrue them when

we tinge them with the color of our own

period, its culture and

genius; but willy-nilly they must be

forced into the compass of

our historical perceptions and

conceptions, and the reader, a

hundred years ago, of a history of a

past period, got a very

different picture of that time from one

impressed upon the

reader of today by a writer of today.

Therefore, the elements

of personality, of contemporaneous

cultural ideas and of indi-

vidualism in the choice and

determination of importance of ma-

terials are all in the problem, and we

are never sure that we can

get a correct picture of any past

age. The emphasis will be here

in one age and there in another; it will

be at one point with one

author and at a different point with

another even though they

be contemporary; so we must despair of a

complete picture of

the times as they were seen and appreciated by the

people living

Annual Meeting of the Board of

Trustees 371

in those times. The best we can do is an

approximation; whether

it is close or remote will depend upon

the current conception

of historical writings, the capacity of

the writer to be appreci-

ative and sympathetic, his ability to

select the materials adapted

to his purpose, and his ability to color

with his own personality

and with the culture of his age in a

truly reproductive fashion the

masses of materials which lie at hand

for the study of almost

any past age which has left a large

impress upon the world's

history.

The materials for almost any period of

the world's history

are vast and varied. There is only one

historian who has had the

fortitude to undertake by himself the

whole long history of

English Law, from Anglo-Saxon times down

to George the Fifth.

The writers of the social, or political,

or military history of

England--and it is of course customary

to treat them together--

usually choose a period or a phase. As

Macaulay says in his

Preface, "I purpose to write the

history of England from the

accession of King James the Second down

to a time which is

within the memory of men still

living."

But in these times no one really feels

sufficiently familiar

with the great store of historical materials

to venture on the

writing of England's entire history.

When this is desired a

number of historical students

collaborate, each taking the period

with which he is most familiar.

Accordingly a few years ago

a seven-volume history came out. Oman,

the well-known Ox-

ford professor, brought it down to the

Norman Conquest; Davis

took it through the Normans and Angevins

down to Edward

First, the English Justinian in 1272;

Vickers went on through

the late Middle Ages ending where

Richard the Third ended--

at Bosworth Field in 1485; Innes then

carried on through the

Tudors ending with Queen Elizabeth who,

as everybody remem-

bers, died in 1603; the famous

Trevelyan then went on through

the Stuarts, which dynasty ended with

Queen Anne in 1714;

Robertson picked up the thread at that

point and traced the

fortunes of the German kings from

Hanover up to Waterloo,

while Marriott brought it from there on.

A rather remarkable

history of England, the materials--and

they are voluminous--

in each period being treated by the

expert according to his best

judgment. But, you will say, here are

really seven histories, not

one; and the answer must be that if you

want a continuous his-

tory of England from Caesar to McDonald

that is the only way

to get it!

We have several times pursued the same

plan in producing

a History of the United States; we turn

loose the expert on his

372 Ohio Arch. and Hist.

Society Publications

period. The Yale History, the

Schlesinger Social History, and

others, are examples of this type of

history making.

We are going in that direction rapidly

in some of our states,

although Ohio will not need that plan

for some years; with the

fine volumes of Randall and Ryan and the

able and sympathetic

writing of Galbreath, we shall be able

to get the history of Ohio

from a single historian's viewpoint for

many years, and no

tandem series on the mound builders will

be needed so long as

Shetrone's volume endures!

As we stand in the presence of the many

volumes of a sin-

gle historian, like George Bancroft, or

Von I lost, or Lamartine,

or Hume, or the magnificently written

volumes of Green, we are

filled with an immense respect and

appreciation, especially if we

have tried to write some small volumes

ourselves! This respect

rises to praise and almost to wonder in

the case of an English-

speaking historian who ventures into

foreign fields where he

faces the language difficulty in the use

of sources--such as

Motley with his Rise of the Dutch

Republic, Irving with his

Conquest of Granada, Prescott with his Conquest of Mexico, and

Gibbon with his Decline and Fall of

the Roman Empire.

Finally, why should we be busy in our

time in accumulating

materials which a historian of some

future time may utilize in

portraying our lives and civilization to

his people? Of what

importance is it to us whether we

accumulate any historical

material or not? Merely this: we know

our intense curiosity

about the peoples of the past, our

ancestors, or at least our pre-

decessors; we deplore the fact that

printing was not always

known and could not, therefore, always

have left publications

which would be the foundation of our

studies today to satisfy

our historical curiosity. We are

prompted to write, to print, to

accumulate, by something which is a

distinct attribute of the

human being. We preserve our records in

many ways; we want

to pass ourselves on to posterity in the

most complete and fa-

vorable light possible. We cannot escape

these emotions, these

attitudes, these driving

tendencies. Somehow we want to be

understood by the people who come after.

Therefore, we are

willing to spend money and time and the

highest intelligence upon

the accumulation, the organization, the

preservation of all types

of materials which show the character

and quality of our time.

We do this sometimes at enormous personal inconvenience

and

personal efforts but it is well that we do so. We are

merely

satisfying one of the most powerful

innate characteristics of the

human being.

We are enthusiastic about our historical

monuments; we are

solicitous about our historical

manuscripts, and records and me-

|

Annual Meeting of the Board of Trustees 373 morials; we study, almost with bated breath, the relics of a bygone people turned up in our field excavations, and we bring all these materials together in an orderly exhibit completely cata- logued and identified in our museums. We carefully preserve also the evidences of our own domestic life, our industrial pro- cesses and our culture. We organize historical societies to pro- mote and to perpetuate our historical collections and monuments and to enrich the treasures by which a future generation may judge us sympathetically. Financial support for the societies and the museums will wax and wane but it will always be forth- coming. The archives which we build and the antiquities which we store will be in the workshop of the future historian. We trust that the high character of our records may have a shaping and invigorating effect upon the life, and above all upon the thought of future generations. Dr. Rightmire's address was heard with unusual interest and appreciation and heartily applauded at its conclusion. |

|

|