Ohio History Journal

NORRIS F. SCHNEIDER

The National Road:

Main Street of America

A way to the West-where was the best

route?

George Washington pondered that question

anew in September 1784 as he sat in a

land agent's cabin near present-day

Morgantown, West Virginia. Gathered about

him were settlers from that

near-wilderness area on the Cheat River, who had come

at his request to offer their opinions

on the best route for a portage between the up-

per waters of the Potomac and a

tributary of the Ohio River.

Land speculator and visionary as well as

victorious general, Washington had long

been concerned with easy access to the

trans-Allegheny region. While inspecting

his western Pennsylvania land holdings,

he had decided to traverse northwestern

Virginia (now northern West Virginia) to

find a passage through the mountains that

would join the two river systems.

Now, while interrogating the Cheat River

area settlers on the most satisfactory

land route, Washington was surprised to

hear a bold young surveyor in the group

affirm one suggestion with, "There

is the best crossing!" Washington frowned at

the interruption, but after concluding

the interviews, he responded to the young

man, "You are right, sir."

The young surveyor, Albert Gallatin, was

later to help realize Washington's

dream of a route westward, for, as

Secretary of the Treasury under President

Thomas Jefferson twenty-two years hence,

he administered the congressional legis-

lation for construction of the National

Road, the first highway to the West.

It was Jefferson in 1784 who suggested

that Washington look for a route to the

West, because both Virginians were

apprehensive that New York would forge a link

with the Ohio Valley settlers and pull

trade with them to the north.

Not only did Virginia and other seaboard

states want this trade, but settlers al-

ready living in western Pennsylvania

were demanding access to markets for their

surplus crops. At the same time,

thousands of Revolutionary War veterans, who

had been paid for their military service

partly in land warrants, were loudly implor-

ing the government to open the territory

northwest of the Ohio River to settlement.

Their future produce would also require

a route to reach eastern markets.

Washington, who frequently heard these

complaints, wrote in his diary of the

1784 trip, "The Western

Settlers-from my own observation-stand as it were on a

Mr. Schneider, longtime resident and

teacher in Zanesville, has authored twenty-five books and

pamphlets on Zanesville and Muskingum

County in the past forty years. The article was edited by Mari-

lyn G. Hood, editor of special

publications at The Ohio Historical Society.

|

pivet [sic]-the touch of a feather would almost incline them any way .. ." He feared that they might form commercial and political ties with "the Spaniards on their right or Great Britain on their left." To avoid that danger he suggested that the nation "open a wide door, and make a smooth way for the Produce of that Country to pass to our Markets before the trade may get into another channel...." After the National Road became that door, Washington was called the Father of the National Road. The title has been applied to Gallatin also, and perhaps no one man deserves it. But Washington was intimately involved in four enterprises that were precursors of the National Road before Gallatin and other statesmen in- troduced their plans to Congress. First, in the colonial period, Washington and his half-brother Lawrence were among the members of the Ohio Company of Virginia which, in 1752, engaged Colonel Thomas Cresap to supervise the blazing of a path from Cumberland, Mary- land, to its trading post on the Monongahela River (at present-day Brownsville, Pennsylvania). Since Cresap employed the Delaware Indian Nemacolin to do the work, this narrow predecessor of the National Road was called Nemacolin's Path. Second, as a messenger of Virginia Governor Robert Dinwiddie in late 1753, young Major Washington rode on horseback over the future course of the National Road to order the French at Fort Le Boeuf (Waterford, Pennsylvania) to withdraw immediately from British territory. Since the French felt no obligation to obey the British, they ignored Dinwiddie's warning. On his next two trips over the route of the future National Road, Washington was trying to drive out the French by military force. In 1754 Governor Dinwiddie sent him in command of a small army to expel the French from Fort Duquesne where Pittsburgh now stands. However, Washington was ambushed and forced to retreat to a hastily built Fort Necessity, where he surrendered to the French. A year later Washington was an aide to British General Edward Braddock, who dispatched five hundred axmen to cut a road for the infantry and supply wagons which were en route to capture Fort Duquesne from the French. But Braddock also was ambushed, his army routed, and the general killed. Today's Braddock, Pennsylvania, near Pittsburgh, marks the end of Braddock's Road, which was |

|

merely a slash through the forest, obstructed by stumps, brush, and deep gullies. Without repair and hard surface, it became impassable, so that the indomitable pio- neers who subsequently trekked to western Pennsylvania preferred to depend on packhorse trails. Every year these settlers organized a caravan with a master driver to carry local products to market. The packhorses, loaded with hides, gingseng, snakeroot, bear's grease, and rye, wound slowly around swamps and clambered up steep mountain- sides to reach merchants at Hagerstown or Cumberland. On the return trip to their lonely cabins the pioneers carried salt, nails, iron, and gunpowder. The western settlers complained-and listened to promises for obtaining better methods of transportation. Many of the proposals advocated waterways for travel. Anyone who tramps through entangling briers and mazes of high weeds and spongy swamps and scrambles over rocky slopes will conclude, as the pioneers did, that wa- ter travel is easier. They looked for rivers whose headwaters were close enough for |

|

a portage or "carry." The National Road was conceived as such a portage between the Potomac and branches of the Ohio River. Benjamin Franklin had pointed out that only forty miles separated the streams running into the Atlantic from westward flowing rivers, but the headwaters of some rivers were too shallow for boats. Scouts and traders found two suitable ports on the "western waters"-Redstone Old Fort (now Brownsville) on the Monongahela River about seventy-two miles from Cumberland, and Wheeling on the Ohio River, an estimated 112 miles from the Potomac. Western settlers demanded that a por- tage road be built from the Potomac to the Ohio. No one state could afford to construct such an enterprise alone and the individual states were too jealous of each other to cooperate. While the arguments continued, Washington as President faced one of his most perplexing problems because of the lack of such a road from outlying settlements to eastern markets. Farmers west of the Alleghenies could send to market only four bushels of rye on |

118 OHIO

HISTORY

each horse, but the same animal could

carry the product of twenty-four bushels in

the form of whisky. However, after

Washington's Secretary of the Treasury, Alex-

ander Hamilton, imposed an excise tax on

distilled liquor, taxes siphoned off the

farmers' profit. Irate farmers around

Brownsville, Pennsylvania, molded bullets for

their hunting rifles and grimly dared

the tax collectors to come. Washington had to

send a small army to put down this

Whisky Rebellion.

Washington, who died in 1800, did not

see the beginning of the "smooth way" he

had long advocated. Nevertheless, his

effort to "open a wide door" from the Atlan-

tic Ocean to the Northwest Territory had

far-reaching consequences for the future

of the colonies as well as for

transportation. Out of a 1785 meeting of commission-

ers from Virginia and Maryland, to

discuss making the Potomac River navigable

between the Chesapeake Bay and

Cumberland, Maryland, "sprang the movement

for the Constitution of the United

States," according to Hugh Cleland in George

Washington in the Ohio Valley.

Because some Americans considered

federal financing of internal improvements

to be unconstitutional, congressional

leaders devised a method to circumvent oppo-

sition by means of a compact between

Congress and the states which were to be

carved out of the Northwest Territory.

While Congress was deliberating the admis-

sion of Ohio, first of those states to

be created, the territorial legislature sent its

member, Thomas Worthington, to urge

Congress to admit Ohio and to join it to the

East by a road.

Favoring the road was William B. Giles,

dynamic Congressman from Virginia,

who was chairman of the committee for

admitting the Northwest Territory into the

Union. He was receptive to suggestions

made by Albert Gallatin, Secretary of the

Treasury, in a letter dated February 13,

1802.

In brief, Gallatin proposed that if the

states would exempt the lands sold by Con-

gress from taxation for ten years, ten

(later reduced to five) percent of the net pro-

ceeds from sale of those public lands in

the new states would be used for construc-

tion of roads, "first from the

navigable waters emptying into the Atlantic to the

Ohio, and afterwards continued through

the new State." Gallatin proudly en-

dorsed this letter "Origin of

National Road."

The enabling act, passed in April 1802

for admission of Ohio to the Union in

1803, contained provisions for

construction of such a road linking East and West.

Because these two events were

inseparably related, Judge J. M. Lowe said in 1924,

"All hail the Wonderful State of

Ohio. Her admission to the Union made possible

the construction of the road."

From the 1803 Ohio constitutional

convention came the stipulation, which was

accepted by Congress, that three-fifths

of the five percent fund be used for roads

within the state and two-fifths for roads to and through

the state.

Worthington, as a Senator from Ohio,

helped Senator Uriah Tracy of Connecticut

prepare an 1805 committee report, which

predicted the road's mission: ".. . to make

the crooked ways straight, and the rough

ways smooth, will, in effect, remove the in-

tervening mountains; and, by

facilitating the intercourse of our Western brethren

with those on the Atlantic,

substantially unite them in interest, which, the committee

believe, is the most effectual cement of

union applicable to the human race."

Many cities hoped to be the starting

point of that "cement of union." Washing-

ton, D.C., leaders expected that the

proposed National Road would begin in the na-

tion's capital. The merchants of

Richmond, Virginia, wanted the produce of the

western settlers to fill their

warehouses. Philadelphia, already a supplier of goods to

|

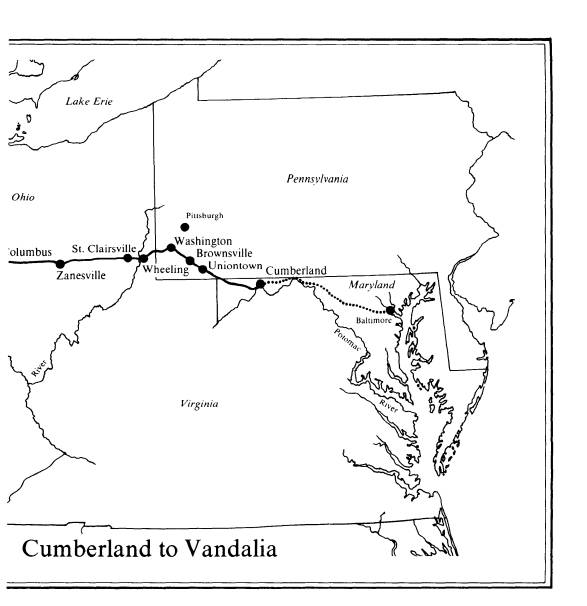

the Ohio Valley through Pittsburgh, took it for granted that the new road would start in front of Independence Hall. But Cumberland, Maryland, had been the starting point for the Nemacolin, Washington, and Braddock expeditions. Originally a fort named for the com- mander in chief of the British army in colonial days, the settlement had grown rap- idly after peace with the Indians was established in 1766. A small but thriving county seat, Cumberland was already the proposed terminus of a road under con- struction from Baltimore westward. Plans for making the Potomac River navigable to Cumberland also favored the choice of that place as the beginning point of the National Road. Statesmen from the rival cities leaned forward in their seats to hear what Senator Tracy would say in his report. The committee proposed "a road from Cumberland, on the northerly bank of the Potomac, and within the State of Maryland, to the river Ohio, at the most convenient place between a point on the easterly bank of said river, opposite to Steubenville, and the mouth of Grave Creek" below Wheeling. By omitting definition of a precise route, the committee left the specifics open to contention by rival factions and cities. But those problems were in the future. The immediate task before Congress was consideration of "An Act to Regulate the Laying Out and Making a Road from Cumberland, in the State of Maryland, to the State of Ohio." The Senate passed the bill December 27, 1805. However, because the road did not cross the South, southern Representatives op- posed the bill. Virginians voted against it 16 to 2 because the road did not originate at Richmond and would not help her seaports. Though the Pennsylvania delega- |

120 OHIO HISTORY

tion knew that the road would cross the

southwestern corner of their state, they op-

posed the act 13 to 4 because it missed

Philadelphia. Nevertheless, the House

passed it 66 to 50 on March 24, 1806,

and it became law five days later.

The law prescribed the method of

construction. Funds were not available for

building an enduring surface like the

Appian Way, and the system developed by the

Scottish expert, John McAdam, had not

yet been tested. The act specified the

methods practiced in 1806: No slope

could be steeper than an angle of five degrees

with the horizon, a right-of-way

sixty-six feet wide was to be cleared of trees and

brush, and along the center a strip twenty

feet wide was to be covered with "stone,

earth, or gravel and sand, or a

combination of some or all of them."

Though the act required that the

President "obtain consent for making the road,

of the State or States through which the

same has been laid out," it did not mention

compensation to the owners of the land.

Congress did not consider it necessary to

secure title to the right-of-way or

condemn by eminent domain because the road

brought "nothing but benefits and

blessings in its train." Not only did land values

along the route increase, but

construction gave work to farmers and their teams.

Every farmer in the nation would have

been happy to see surveyors driving stakes

in front of his cabin. Consequently,

owners of land along the route gladly donated

a strip sixty-six feet wide through

their farms.

One important provision of the act

directed the President "to appoint, by and

with the advice and consent of the

Senate, three discreet and disinterested citizens

... to lay out a road from Cumberland

... to the river Ohio." In compliance with

this provision President Thomas

Jefferson on July 16, 1806, signed a proclamation

which has been called "the

beginning of government participation in road construc-

tion." He named Eli Williams and

Thomas Moore of Maryland and Joseph Kerr of

Ohio as road commissioners.

The first report of the commissioners in

December 1806 proved that they were

"discreet," as well as hardy.

They tramped through underbrush, climbed moun-

tains, and forded streams to find the

best route. In mapping a survey of the esti-

mated 112-mile long route, they were

guided by sound principles: Shortness of dis-

tance between navigable points on the

eastern and western waters, crossing the

Monongahela River at a point convenient

to the area, reaching the Ohio River

where that stream was navigable and

where emigrants could cross, and "diffusing

benefits with least distance of road."

The official name of this "cement

of union," this portage between eastern and

western waters, was the Cumberland Road.

On the reports of David Shriver, first

superintendent of construction, the term

United States Road was written. It was

also called the National Pike and the

Old Pike, but the most popular term was the

National Road, which was in general use

by 1825.

The National Road has been called the

Appian Way of America-with good rea-

son to recall the beginning of that

historic route. When Shriver's surveyor pointed

his transit from the corner of lot No. 1

in Cumberland he was carrying on a tradition

that started when roads were marked from

the golden milestone in the center of the

Roman Forum. From lot No. 1, where a

marker stands today, surveyors trudged

westward, conscientiously hacking their

way through brush and carrying their tran-

sits and chains up steep slopes to

diffuse the "benefits with least distance."

The shortest route did not always meet

with local approval, however. When

Pennsylvania gave permission for the

road to pass through that state, she requested

that it deviate from the most direct

route in order to pass through Uniontown on its

National Road 121

way to Brownsville, and through

Washington before it reached Wheeling.

Brownsville had been specified as the

most favorable place to cross the Mon-

ongahela River because, as Redstone Old

Fort, it had long been the place where

pioneers had embarked on flatboats to

reach Ohio and Kentucky. After President

Jefferson approved the deviation through

Uniontown in February 1808, Washing-

ton area citizens demanded that the

route be altered to include them. Jefferson's

Secretary of the Treasury, Albert

Gallatin, joined the chorus in July 1808, pointing

out that his home county, Washington,

had a majority of two thousand Democratic

votes. He warned that "if this be

thrown, by reason of this road, in a wrong scale,

we will infallibly lose the State of

Pennsylvania at the next election;..."

Jefferson concluded that if

"inconsiderable deflections from this course will ben-

efit particular places, and better

accommodate travelers," the change in route

should be made. Since both deviations

were short and followed already existing

roads, the principle of "diffusing

benefits with least distance of road" was not de-

stroyed. The changes did set precedents,

however, for future requests to satisfy

other "particular places."

When the site of the Ohio River crossing

was to be determined, several places

battled violently to be selected. In the

thirty-five mile stretch delineated by Con-

gress, the topography of the eastern

bank offered eight possible approaches to the

river. Among the area towns, Charlestown

(the former name of present Wellsburg)

waged a full-scale bombardment of public

officials with demands to be designated

as the terminus. Even Ohioans were

concerned about the crossing because of its ef-

fect on future roads through their

state. When Steubenville residents withheld no

verbal artillery that would promote

their interests, a Zanesville editor warned that a

road through Steubenville would extend

through Newark and thus make Zanesville

a ghost town.

In all this maneuvering, Wheeling's

leaders looked out confidently from their po-

sition of superior advantage and

location. Since the days of the Revolution, pack-

horse trails had led overland to their

town. Also, it was a principal crossing of the

Ohio River because Zane's Trace, the

first road in Ohio, started on the west bank of

the river just across from Wheeling, and

threaded its way southwest through the for-

est to the Ohio River opposite

Maysville, Kentucky.

The trace had been blazed by Colonel

Ebenezer Zane, founder of Wheeling, who

had been authorized by Congress in 1796

to cut a bridle path that would be shorter

and less expensive for mail carriers

than the river route to Maysville and would be

passable when the Ohio River was blocked

by ice. As compensation Zane had re-

ceived 640 acres of land wherever his

trace crossed an important river. Zanesville,

Lancaster, and Chillicothe grew up on or

near those tracts.

Because of Wheeling's importance as a

crossroads and the influence of Henry

Clay, the leading advocate of internal

improvements, Congress chose Wheeling as

the terminus of the National Road on the

Ohio River. On March 28, 1816, Wheel-

ing residents appropriately celebrated

their good fortune, and later Clay's apprecia-

tive friends erected a monument in his

honor.

Wagons and emigrants were already on the

way. While the river towns had

wrangled about the crossing point,

contracts for construction of the first ten miles

west of Cumberland had been, signed in

April and May 1811--nine years after pas-

sage of the enabling act which had

contained provisions for construction of the road.

Laborers swung mighty blows with

mattocks and grunted as they struck gashes in

huge tree roots. Farmers along the route

earned a few dollars by hauling earth to fill

|

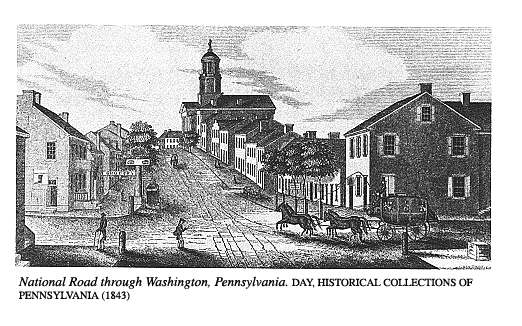

gullies. Stonemasons played a day-long rhythmical tapping of hammer against chisel as they shaped stones for culverts and bridges. On the Allegheny Mountains, rising from seven hundred feet at Cumberland to more than two thousand feet near Keyser's Ridge, the road builders met their greatest challenge. Not only was it nec- essary to fell and grub out towering trees, but sixty-six foot wide passages had to be cut through rock-ribbed ancient precipices. Finally, in 1818, workmen graded and scattered stone on the last foot of the road to the steamboat landing at Wheeling. Washington's dream had been realized-the eastern and western waters were joined. The National Road immediately became a well traveled highway. Stagecoaches carrying passengers and mail ran on schedule between Cumberland and Wheeling and, by branching off, to Washington, D.C., and other cities. Conestoga wagons loaded with freight rumbled over cobblestones to landings to meet steamboats which chugged up and down the Ohio River. From Wheeling, emigrants to the western states also could embark on flatboats down the Ohio or could cross the river by ferry and bump over Zane's Trace or the Ohio state road to new farms. Travelers praised the new road, Uria Brown of Maryland, who rode horseback over the Pennsylvania section in 1816, wrote in his diary:

This great Turnpike road is far superior to any of the Turnpike roads in Baltimore County for Masterly Workmanship, the Bridges & Culverts actually do Credit to the Executors of the same, the Bridge over the Little Crossings of Little Youghegany River is possitively [sic] a Superb Bridge; The goodnes [sic] of God must have been in Congress unknownst to them; when the[y] fell about to & Erected a Lane for the Making of this great Turnpike road which |

National Road

123

is the Salvation of those Mountains or

Western Countrys & more benefit to the human fam-

ily than Congress have any knowledge....

Brown called the road

"handsome" and "ellegant."

The cost of construction had exceeded

the estimate of $6,000 a mile. On the high

peaks between Cumberland and Uniontown

the average expenditure was $9,745

per mile. West of the Allegheny

Mountains where less grading was needed, too lib-

eral contracts were awarded to

profiteers. As a result the average cost per mile

from Cumberland to Wheeling was $13,000.

In the years since authorization of the

National Road, settlers had been pouring

into central Ohio, Indiana, and

Illinois. Those who traveled overland found both

Zane's Trace and the Ohio state road to

be inadequate. The latter, which the state

built in 1804 with an appropriation of

$15 per mile provided by the three percent

fund from the sale of public lands,

generally passed through the same towns as the

trace, though it veered from that path

when surveyors found a better route. Speci-

fications permitted contractors to leave

stumps a foot high in the twenty-foot width.

Whenever a vehicle hit such a stump, the

driver longed for a good road. Travelers

besieged Congress with petitions to

extend the National Road directly westward to

the Mississippi River.

That proposal, however, was held up by a

roadblock-interpretation of the Con-

stitution. The most hotly debated

question of the early nineteenth century was

whether the Federal Government had the

authority to appropriate money for inter-

nal improvements. In the early years

when all the states bordered the Atlantic

Ocean, Congress had made appropriations

for piers, lighthouses, beacons, and

buoys. But now that new states in the

West could be reached only by overland

routes, the question arose-could the

Federal Government allocate funds for a road

project?

Senator John C. Calhoun said yes in

1816. "Let us, then," he urged, "bind the

republic together with a perfect system

of roads and canals. Let us conquer space."

He insisted that authority for Congress

to finance roads was implied by the provi-

sion of the Constitution granting power

to establish post offices and post roads.

President James Madison stood on the

other side. When Congress voted to use a

bonus, paid by the Second Bank of the

United States, for internal improvements in-

cluding the National Road, Madison

vetoed it because he considered it uncon-

stitutional.

While Ohio waited for extension of the

road, the 131 mile section east of Wheel-

ing was being ground by the wheels of

heavy wagons into a lane of deep ruts. In

1820 friends of the National Road

introduced into Congress the "gate bill" which

provided for collection of tolls to keep

the road in repair. Two years later both

houses passed the "gate bill,"

but President James Monroe vetoed it because he be-

lieved that Congress did not have the

right of jurisdiction and construction. He

proposed a constitutional amendment to

authorize federally supported internal im-

provements.

This was a period of splitting

constitutional hairs. When President Monroe later

suggested that Congress could

appropriate for internal improvements under the

general welfare clause of the

Constitution, as long as the benefits were of national

dimension, he offered a solution to the

dilemma. In 1824 he signed a bill which

provided funds to repair the road and to

extend it west of the Ohio River. At last

the people of Ohio could expect to see

surveyors with transits and chains marking

124 OHIO

HISTORY

the right-of-way through their farms. In

Indiana, which had been admitted to the

Union in 1816, and Illinois, admitted in

1818, citizens also anxiously awaited the

road crews.

Congressional friends of the road had

not been idle. Although in 1820 they had

appropriated $10,000 to survey a road

from Wheeling to the Mississippi River, that

resulted in only a row of stakes. It was

not until March 3, 1825, that Ohioans could

cheer the news that Congress had

appropriated $150,000 to build the first section of

the road west from the Ohio River to

Zanesville, paralleling the inadequate existing

Ohio state road.

When ground was broken at St.

Clairsville, Ohio, on July 4, 1825, the program in-

cluded reading of the Declaration of

Independence, a volley by the Belmont Light

Cavalry, and an eloquent address by

William B. Hubbard, later a state senator, in

which he prophesied that the road was

destined to reach the Rocky Mountains.

Construction by this time was under the

direction of engineers in the War Depart-

ment, who found that the method of

sprinkling sand or gravel, which had been used

east of Wheeling, did not make a lasting

roadbed. Secretary of War James Barbour

announced, "After the most mature

consideration, I have determined that [we shall

complete the road] on the McAdam plan

...." That Scotsman, John L. McAdam,

opposed the use of gravel because

revolving wheels moved it. By his method the

grade was covered with layers of broken

stone "which shall unite by its own angles

so as to form a solid, hard

surface."

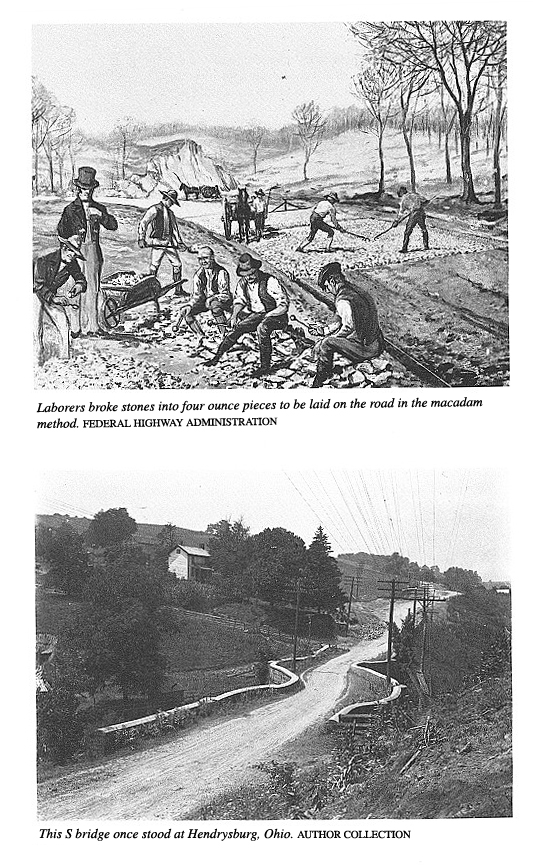

The thirty foot wide roadbed was paved

with layers of broken stone by the maca-

dam method. Gangs of laborers, mostly

Irishmen, were paid $6 a month to break

limestone with round-headed hammers into

pieces that would pass through a three-

inch ring. They wore metal goggles with

slits to protect their eyes. There is a tradi-

tion that some members of farm families

who earned pin money by breaking stone

charged the government twice for the

same stone heap until officials poured white-

wash over stone that had been paid for.

The Corps of Engineers realized that

water rushing down the steep Pennsylvania

mountains and Ohio hills during heavy

rains could erode the stone surface of the

road. They tried to divert the

destructive torrents by building diagonal trenches

called catchwaters across the macadam

paving. Stagecoach passengers, bounced by

the ditches, sardonically named them

"thank-you-marms."

On the eastern Ohio section of the road

the stonemasons built several S-shaped

bridges. According to a folk story, John

McCartney, an Irish stonemason, met the

English architect, Benjamin H. Latrobe,

an engineer for the government, at an inn

one night and solicited the contract for

a bridge. Latrobe quickly drew a sketch

and handed it to McCartney with the

sneering challenge, "Build that if you can."

And McCartney built the S-shaped

structure. Another legend relates that the

bridges were built to stop runaway

horses.

The true explanation is less romantic.

Either the stonemasons did not have the

skill or they did not want to take the

time to cut huge sandstone blocks in the he-

licoidal shape to cross a stream on the

skew. They built an arch at a right angle

with the stream and curved the

approaches into it. The resulting shape resembled

the letter S.

The stonemasons who squared and dressed

the huge blocks in the bridges also

made the milestones in Ohio. A number at

the top of each stone informed the pas-

sengers speeding past at six to twelve

miles an hour how far they were from Cum-

berland. On the angular sides of the

markers were cut the mileages to the towns

126 OHIO HISTORY

east and west. Many of these milestones

still remain on the north side of the road.

When the original milestones in

Pennsylvania disintegrated, they were replaced by

iron mile markers cast at foundries in

Brownsville and Connellsville.

Pennsylvania had set a precedent for

changing the route of the road to satisfy lo-

cal preference. When the layers of

broken stone had been spread as far as Zanes-

ville in 1830, Newark held mass meetings

and petitioned Congress to curve the road

up through its main street, but the

attempt failed.

Then the northern and southern parts of

Columbus competed for the road. By a

compromise it entered that city in 1833

on Friend (now Main) Street, turned north

on High Street, and continued westward

on Broad. West of Columbus, Dayton and

Eaton made desperate efforts to bend the

road southward for their benefit. But the

surveyors followed the order of Congress

to aim their transits directly westward

through the state capitals.

The average cost per mile in eastern

Ohio was much less than the $13,000 per

mile in Pennsylvania. Averaging $3,400

per mile, the eastern Ohio figure included

three inch layers of broken stone,

masonry bridges, and culverts.

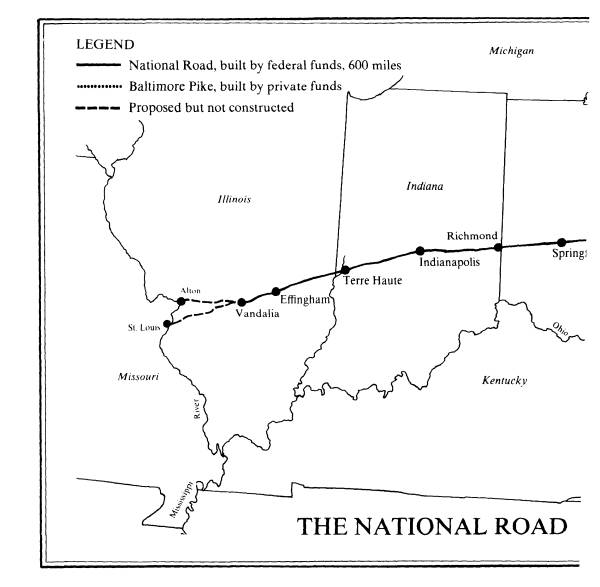

In Indiana the National Road was built

east and west from Indianapolis, capital

of the state. Jonathan Knight, the

surveyor in charge, sent out his crews in 1827.

Because he permitted no deviation from a

straight line, the route passed through

few towns.

As workmen began to cut through the

heavy forest in 1829, farmers were em-

ployed at sixty-two and a half cents a

day, blacksmith and wagon shops and taverns

were built to accommodate travelers, and

towns sprang up along the road. Though

Washington Street in Indianapolis was

macadamized, most of the federally-sup-

ported work in Indiana was limited to

cutting timber, grubbing stumps, and digging

ditches, which were completed by 1834.

Federal work was suspended in 1841 be-

cause of lack of congressional appropriations.

After the road was turned over to the

jurisdiction of the state, Indiana

completed its intrastate segment in 1850.

William Greenup, supervisor of

construction in Illinois, let his first contracts in

1830. Progress was slow because of cold

winters and prairie flies that tortured

horses in summer. As in Indiana and

Ohio, trees were felled in a strip eighty feet

wide and the stumps were grubbed out for

a thirty foot roadbed.

The Illinois road surface was dry, hard

clay because stone was not plentiful. The

unfinished eighty-nine mile section from

Indiana to Vandalia, then capital of the

state, was opened in 1839 and federal

work was suspended the next year for lack of

money.

Though Congress considered extending the

National Road from Vandalia across

the Mississippi River into Missouri, the

extension was halted by controversy over

the route. Since the act of 1806

provided for approval by the states through which

the road passed, Illinois and Missouri

were deadlocked-the former demanded a

crossing at Alton, and the latter

insisted that the road enter that state at St. Louis.

Congressional opposition also delayed

action, especially when Henry Clay, former

proponent of the National Road, spoke

against the extension. The issue was

brought up in Congress for the last time

in 1847. Nine years later the Federal Gov-

ernment transferred the road to Illinois

control.

By that time the Illinois Central

Railroad had roared into Vandalia and made

stagecoaches and Conestoga wagons

obsolete. Also, in 1839, with the support of

the young legislator Abraham Lincoln,

the Illinois General Assembly had moved

the capital to Springfield. However, the

western terminus of the National Road re-

|

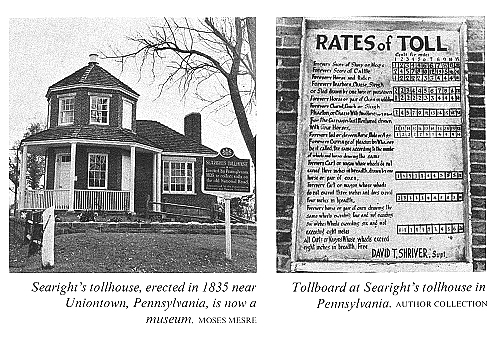

mained Vandalia, where the former state capitol has been restored as a historic mu- seum. Congress made its last appropriation for the road in 1838. The total amount spent on its construction by the Federal Government was $6,824,919.33. Before the stones of the last bridges and culverts in Illinois were laid in place, however, the eastern section had been cut to pieces by thousands of turning wheels. It was generally agreed that the cost of repair should be paid by users of the road in the form of tolls. After years of debate Congress decided that it was uncon- stitutional for the Federal Government to collect toll. Instead, in the 1830's Con- gress began to turn the road over to the states for administration and maintenance, though some of the states required that extensive repairs be made before they would accept ownership. As the states accepted their sections of the National Road, they started to collect toll. Pennsylvania built six tollhouses about fifteen miles apart. The one called Searight's five miles west of Uniontown has been restored as a museum. In that state a horse and rider paid four cents toll; every score of light-footed sheep, six cents; a score of cattle with sharp hooves that cut holes in the road, twelve cents; a stagecoach with two horses, twelve cents; any vehicle with four horses, eighteen cents. Because narrow wagon tires gashed ruts in the road, drivers of those con- veyances paid higher rates. Wagons with tires six or eight inches wide, which acted as rollers, passed the gates free in some states. In Ohio tollhouses stood about ten miles apart. Though rates were slightly higher than in Pennsylvania and the Buckeye state collected nearly a million and a quarter dollars in toll from 1831 to 1877, that amount was insufficient to maintain the road adequately. Travelers reached into the pockets of their jeans to pull out hard money to pay for the cost of riding on a solid road, although some handed over the coins under protest. When clay roads paralleled the National Pike, farmers took the longer route to save the cost of toll. Or, they could "compound"-pay a year's toll in advance and travel for a year and a quarter. Not only did travelers complain about the toll, but some tollkeepers drew their |

National Road 129

ire. A Zanesville man asserted that one

toll collector "feels that because he is

dressed in a little brief authority, he

has a right to insult with impunity; or to shoot

his neighbor's cows if they happen to

pass the gate without paying toll."

Free passage over the National Road was

granted for special uses, depending on

the time and place. Free travel was

frequently permitted for going to or returning

from public worship, military muster,

funerals, mills, voting places, and business

establishments. Although Congress

granted some states the right to make the road

free as early as 1879, tolls remained in

force in certain areas as late as 1910.

A picturesque cavalcade of horse-drawn

vehicles clopped and rumbled over the

six hundred mile length of the road.

Some wagons branched off at the Mon-

ongahela or the Ohio to continue their

journey on flatboats by water. Many kept

their place in the endless caravan that

rolled all the way to Vandalia. Those who

wrote diaries remarked about the

historic and scenic wonders they passed.

Starting from Cumberland, the early

travelers curved down on Green Street

south of Wills Mountain and turned

westward at the Six Mile House. In 1834 the

U. S. Engineers diverted the route

through the nine hundred foot deep Narrows and

across a new stone bridge over Wills

Creek.

Soon after passing St. John's Rock just

west of Frostburg, the horses strained

against the harness to pull one thousand

feet in fourteen miles up Big Savage

Mountain, then caught their breath over

the Long Stretch of undulating straight

road for two and one-half miles before

entering a dark tunnel under the arching

branches of white pine forest called

Shades of Death because of the holdups and

murders there.

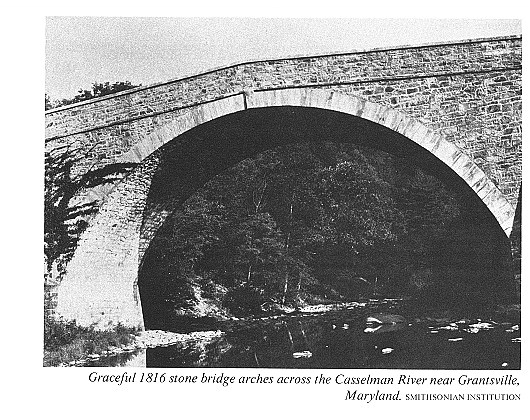

West of these Appalachian heights,

before entering Grantsville, travelers rode

over the picturesque stone bridge across

the Casselman River called Little Crossings

to distinguish it from the Big Crossings

of the Youghiogheny River at Somerfield.

Between those crossings the road passed

the border from Maryland to Pennsyl-

vania.

Immediately beyond Somerfield, Gobbler's

Knob rose abruptly. West of the

knob the road traversed a level stretch

called Jockey Hollow where horse races and

cockfights were held.

In the days before traffic signs and

markers, travelers knew from their school

books when they were passing Fort

Necessity at Great Meadows where Washington

had surrendered to a superior French

force. And west of that historic site they saw

where the brave and obstinate General

Braddock had been buried in the roadbed.

After resting the horses several times

over Laurel Hill, travelers reached Union-

town, midway between Cumberland and

Wheeling. Many guests were entertained

at its famous taverns. It was the home

of Lucius W. Stockton, manager of the Na-

tional Road Stage Company, and Thomas B.

Searight, author of The Old Pike, the

first book about the National Road.

Brownsville, the next town on the

westward journey, was in the area where the

Whisky Rebellion had erupted in pioneer

times. At Brownsville in 1839 the Corps

of Engineers built the first cast-iron

bridge in the nation to carry the National Road

across Dunlap's Creek.

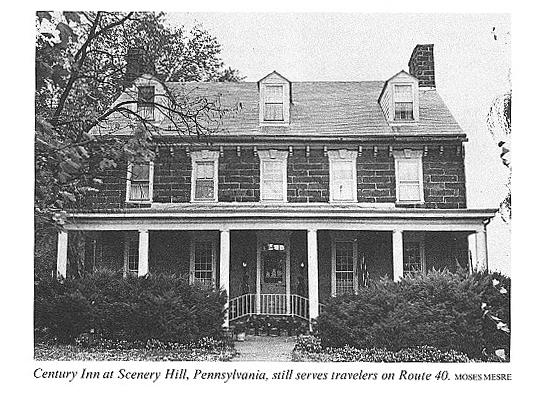

From Scenery Hill, about ten miles west

of Brownsville, travelers gazed at beauti-

ful landscapes. Six miles west of

Washington, the largest city between Cumberland

and Wheeling, they drove on an S bridge

over Buffalo Creek. At Elm Grove, in

present West Virginia, they saw Colonel

Moses Shepherd's monument to Henry

Clay in appreciation for his influence

in routing the National Road to Wheeling.

|

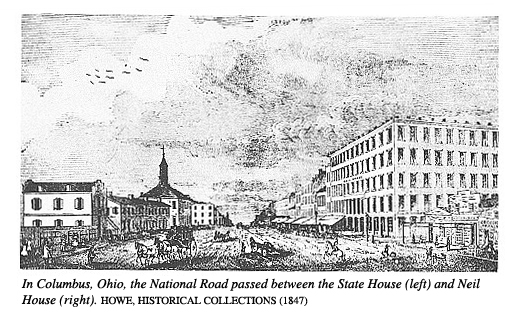

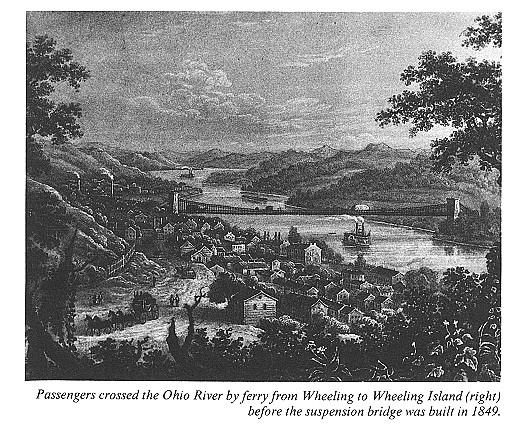

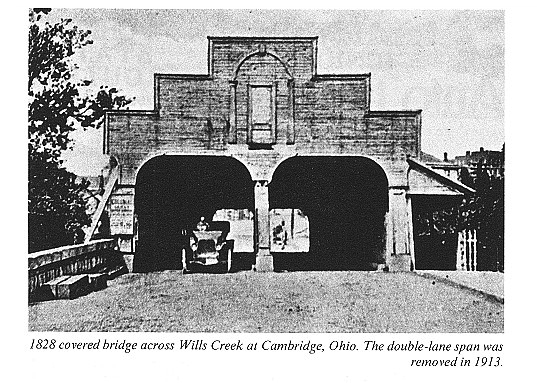

All traffic through Wheeling crossed to Wheeling Island in the Ohio River by ferry until the suspension bridge was completed in 1849. West of Bridgeport on the Ohio side the traveler rode through hilly country. When he was not roller coastering up and down, he was zigging and zagging through S bridges. On the way he passed through St. Clairsville, where work on the road in Ohio had begun in 1825. At Cambridge travelers heard about Joseph C. Dylks, who preached in the surrounding leatherwood shrub country, proclaiming his divinity and earning the sobriquet "Leatherwood God." In Zanesville the road crossed the Muskingum River on a Y bridge that forked in the middle. The National Road traversed the left fork which led through the cen- tral Ohio plains, where glaciers long before had smoothed the land by slicing off the hills and filling up the valleys. Just as travelers had viewed the smoke rising from hundreds of log cabins in the Pennsylvania mountains, here on the level plains from central Ohio to Vandalia, they saw more cabins in vast deadenings. After settlers had killed the trees by girdling, they had planted corn and other crops around them. On farms that had been settled a quarter of a century earlier, stumps still dotted the fields though the trees had been laboriously chopped down and rolled into piles or burned. At Columbus, Ohio, the National Road passed on High Street between the Neil House and other taverns on the west side and the State House on the east. Trav- elers who drove through Springfield after 1845 saw Wittenberg College, and at Richmond, Indiana, after 1847, they passed by Earlham College. Driving along Washington Street in Indianapolis past the state capitol, a visitor could hardly dream that the future Motor Speedway in that city would offer speeds far in excess of his five to ten miles an hour. Before reaching the Illinois border, the traveler drove down the streets of Terre |

|

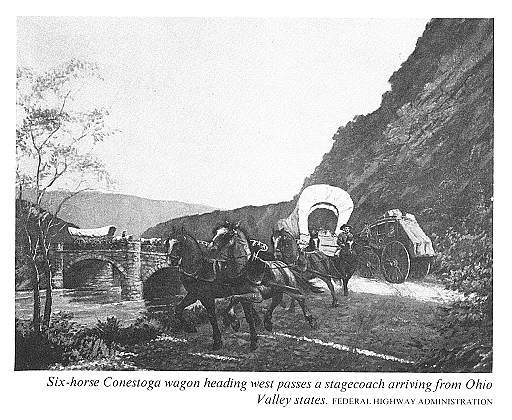

Haute and crossed the Wabash River, which later inspired the state song of Indiana. If stagecoach passengers arrived at Vandalia in 1839, they might have seen Abra- ham Lincoln among the legislators striding across the State House lawn. Over the six hundred mile length of the National Road horses pulled many types of vehicles. Paton Yoder wrote in Taverns and Travelers that "movers" were "the largest single class of travelers." Poor families from the worn-out farms in the east- ern states packed their pots and clothes and blankets in covered wagons and started for the land of promise. At night they pulled off the National Road to camp. While father and sons un- harnessed and fed the horses or oxen, mother and daughters cooked the evening meal in an iron kettle over an open fire. Women and children slept in the wagon and men spread blankets on the ground. Occasionally a family of movers could see down the road the campfire of a man who was transporting his belongings to his new home in a pushcart. Freight was hauled in huge Conestoga wagons, named for the Conestoga River Valley of Pennsylvania where they were first made. With deep wood beds sloping upwards toward the ends to prevent the shifting of loads and with canvas tops drawn tightly over bent wood bows, these wagons could carry from six thousand to ten thousand pounds of freight. They were pulled by six-horse teams controlled by a driver who rode or walked beside the left wheel horse and guided the team by a single line to the left lead horse. Some wagoners painted the wagon body blue and the wheels red. They also hung brass bells from an arch fastened to the hame of the harness over the neck of each horse. Conestoga wagons hauled flour, wool, hemp, and tobacco from the western fron- tier to eastern markets and on the return trip carried calico, sugar, and coffee to fill the shelves of merchants. Hauling freight was a profitable business. Both regular wagoners and "sharpshooters," farmers who made occasional trips, engaged in the trade. One commission house at Wheeling in 1822 received loads from 1,081 wagons, averaging about 3,500 pounds each, and paid out $90,000 in transportation charges. |

|

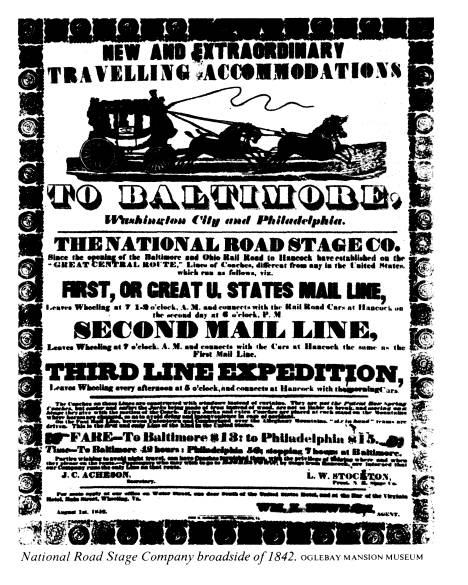

Inasmuch as there were five other commission houses in Wheeling, it has been esti- mated that nearly five thousand wagons were unloaded and that $400,000 was paid to the drivers of Conestogas that year. The drivers considered themselves lords of the road. These stanzas from a poem entitled "The Waggoner" express this pride: The golden sparks, you'd see them spring Beneath my horses' tread; Each tail I'd braid it up with string Of blue or flaunting red; So does, you know, the mountain boy Who drives a dashing team. Wo, hoy! Wo, hoy! I'd cry. Each horse's eye With fire would seem to burn; With lifted head And nostril spread They'd seem the earth to spurn. Freighters made more profit than stagecoaches on the National Road. Although cross-country travel for pleasure was not as popular in the golden age of the Na- tional Road as it is today, stagecoaches ran on regular schedules. Passengers in- cluded merchants on annual visits to eastern markets, legislators shuttling back and forth between their districts and the halls of Congress, foreign visitors, and a few lo- cal travelers. Lucius W. Stockton operated the National Road Stage Company east of Wheel- |

|

National Road 133

ing from headquarters in the National House at Uniontown, Pennsylvania. West of the Ohio River Neil, Moore and Company ran regular schedules until they consoli- dated with the Ohio Stage Company. Neil not only retained a large interest in that company but also started a hotel in Columbus which still bears his name. Small local lines often took the road in competition with the big companies. These competitors called themselves the Good Intent, Defiance, Pilot, or June Bug line. Their rivalry took the form of price cutting and ridicule. J. T. Rowe an- nounced in 1844 that his "sober and attentive drivers" would speed passengers fifty- five miles from Zanesville to Columbus in eight hours for $2. Though fares varied somewhat, they remained rather constant during the stagecoaching heyday, when one could travel from Cumberland to Indianapolis, a distance of about 450 miles, for $18.25. |

|

134 OHIO HISTORY

The drivers circulated sarcastic rhymes about each other, such as: If you take a seat in Stockton's line, You are sure to be passed by Peter Burdine. The early stage wagons with three board seats across the bed were replaced about 1830 by the egg-shaped Troy and Concord coaches, which cost between $400 and $600 each. The driver held the reins on his high front seat, and a leather "boot" at the rear carried luggage. These coaches, brightly painted on the outside, were up- holstered with silk on the inside. Side lamps for night driving avoided collisions but did not illuminate the road. Coaches were identified by names painted in gold letters on the doors. Their names are preserved on bills in the Darius Tallmadge Collection at The Ohio His- torical Society, where are found such notations as: Repairing hind boot, P. Henry, $.50; 2 New front wheels for Boliver, $10.00; Drawing braces for Jefferson, $1.00; Repairing lamp iron, Marion, $.50; Driver's cushion for Elliott, $4.00. When residents in a town on the road heard the driver's horn, they crowded around the stage tavern as the team stopped. They saw many notables step down from the coaches. Sam Houston, Davy Crockett, John C. Calhoun, Daniel Web- ster, John C. Fremont, and James G. Blaine lost no time at every stop in winning political followers. There were no bullet-proof limousines in those days. Ordinary citizens riding in coaches on the National Road literally rubbed elbows with these Presidents before or after their elections-John Quincy Adams, Andrew Jackson, James Polk, Zachary |

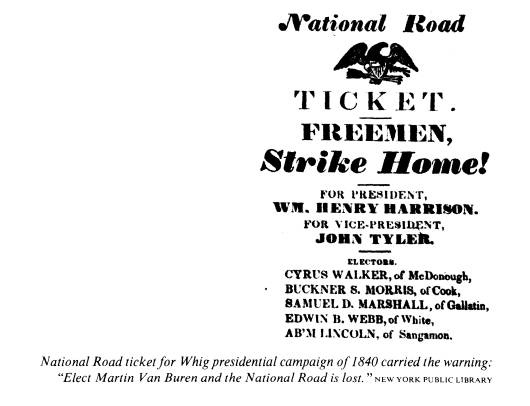

National Road 135

Taylor, Millard Fillmore, William Henry

Harrison, Martin Van Buren, and Abra-

ham Lincoln.

When Henry Clay, champion of the road in

its early years, stumbled and fell

from a stagecoach at Uniontown, he

remarked as he brushed his clothes, "This is

mixing the Clay of Kentucky with the

limestone of Pennsylvania."

Joseph Jefferson, famous actor, and many

other stage celebrities traveled along

the National Road. The "Swedish

nightingale" Jenny Lind and her impresario

Phineas T. Barnum hired ten coaches to

haul them, their entourage, and costumes

to the East after a southern tour.

Less famous travelers also patronized

the National Road. Among them was J. S.

Buckingham, an Englishman, who wrote of

his travels in Ohio in 1840:

In the course of our journey from

Wheeling to Zanesville, we found the road admirable all

the way, as good indeed as the road from

London to Bath.... it was no ordinary luxury to

travel on this smooth and equable

National Road, where we were driven at an uniform rate

of about seven miles an hour.... and I

must say, a better road than the one on which we

were now travelling, could not be found

in England.

Versifiers romanticized the

stagecoaches. When passengers switched their prefer-

ence to the new railroad cars at

mid-century, people like Sidney Dyer looked back

longingly at the old vehicles:

The old stage coach in its golden day

Rolled proudly on with its cheerful

load,

And claimed from all the full right of

way,

A monarch then of the turnpike road.

But now the day of its pride is o'er;

It yields the palm to the railway train;

The dear old friend so loved of yore,

We ne'er shall look on its like again.

Then, ho! for the days of the turnpike

road,

The prancing steeds and the brisk

approach,

The mellow horn, and the merry load

That used to ride in the old stage

coach.

Stagecoaches carried the U. S. mail,

which provided a great temptation for rob-

bers to waylay the coach at a dark and

lonely spot. Newspapers frequently re-

ported such robberies. In one case,

however, it was the general agent of the Ohio

Stage Company who stealthily robbed the

mailbags for years. After his discovery

and forfeiture of $10,000 bond, the

accused moved to the distant shores of Australia.

To speed important mail Postmaster

General Amos Kendall started operation of

a pony express on the National Road in

1836. His riders, boys fifteen to seventeen

years of age, whipped their horses to a

gallop and changed mounts every six miles.

The time for the fifty-five mile trip

between Zanesville and Columbus was cut from

nine to five hours. But the pony express

ran for only two years.

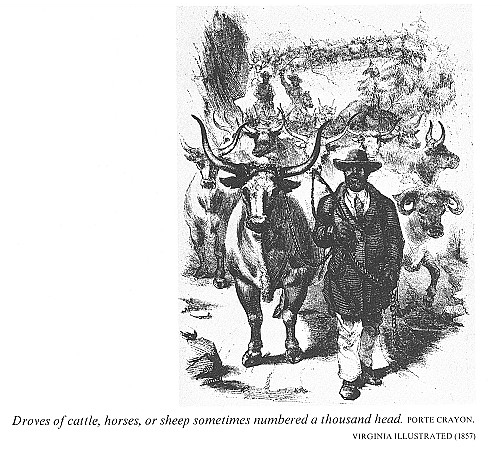

The express riders and all vehicles were

slowed frequently by droves of livestock.

When stagecoach passengers saw a cloud

of dust in the distance, they knew they

were approaching a drove. Although

farmers salted part of their surplus meat and

sent it to New Orleans by flatboat, freight

rates were too high and progress too slow

to haul it to eastern cities by wagon.

Therefore, western farmers delivered meat to

Baltimore on the hoof. They drove herds

of a thousand hogs, cattle, sheep, and

|

even turkeys over the National Road. The drivers spent several weeks heading off the stragglers that strayed into the woods. At night they stopped at drovers' stands where the stock was fed and the drivers slept on blankets in front of the fireplace. Stagecoach passengers "fed" and "slept" at taverns. In Pennsylvania Searight counted enough of these hostelries to locate an average of one for each mile of road. West of the Ohio River they stood about five miles apart in the country, and several genial hosts welcomed travelers in each town. The tavern on the National Road was a popular and romantic institution. Local residents visited its public rooms for news and gossip and crowded those halls for court sessions, dances, theatrical per- formances, lodge meetings, and even church services. Artistic signboards invited travelers to the taverns. Many of the hosts used their own names, such as Uzal Headley west of Zanesville or Huddleston west of Cam- bridge City, Indiana. Others displayed their patriotism by calling their taverns American, National, or Constitution. Travelers saw signs picturing a Swan, White Goose, Sheep's Ear, and Bull's Head. A portrait gallery lined the road with like- nesses of Franklin, General Washington, Indian Queen, Mermaid, and The Jolly Irishman. The driver's horn brought the tavern host to his door. He knew that the ap- proaching stagecoach would stop to "water the horses and brandy the gentlemen," as Basil Hall wrote, and patronize his dining room. The menu varied from ham and eggs at country taverns to apple rolls, custard pie, sherry, claret, and cham- |

National Road 137

pagne at the Neil House in Columbus,

Ohio, the largest city on the road.

Nostalgia saddened the hearts of

visitors to the inns after the railroads robbed

them of patronage. Only verse could

express their feelings:

It stands alone like a goblin gray,

The old-fashioned inn of the pioneer

day,

In a land so forlorn and forgotten, it

seems

Like a wraith of the past rising into

our dreams;

Its glories have vanished, and only the

ghost

Of a sign-board now creaks on its

desolate post,

Recalling a time when all hearts were

akin

As they rested at night in that

welcoming inn.

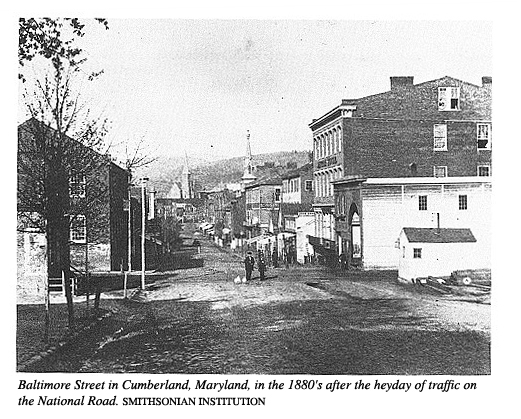

When the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad

steamed westward from Baltimore,

Lucius W. Stockton resented and

belittled the competition to his coaches. He de-

cided to prove that the horse was faster

than the locomotive. With his favorite gray

horse he raced a train and won.

Eventually, however, the train proved to

be successful, reaching Cumberland

from Baltimore in 1842. As the rails

were laid farther west, passengers preferred to

ride behind locomotives rather than slow

horses. Friends of the National Road bit-

terly opposed the extension of the

railroad west of Cumberland.

Congressman Henry W. Beeson of

Uniontown, Pennsylvania, delivered an ad-

dress on the widespread unemployment the

railroad would cause. He enumerated

the number of horseshoes the blacksmiths

made annually, the amount of grain and

hay the farmers sold to drovers,

freighters, and stagecoach teams, and the number

of chickens, turkeys, and eggs eaten at

taverns. His arguments failed to stop prog-

ress of railroad construction, however,

and the line reached Wheeling in 1853.

Within ten years the railroads had

captured all the cross-country passenger and

freight traffic to the Mississippi

River. No longer did the National Road echo with

the shouts of drovers, the clatter of

six-horse teams hitched to Conestoga wagons, or

the shrill notes of the stagecoach

driver's horn. Instead, the silence of the road that

had been called the Appian Way of

America was broken only by the wagon of a lo-

cal farmer driving to market with no

other vehicle in sight.

Harper's magazine in November 1879 commented that "The

national turnpike

that led over the Alleghanies [sic] from

the East to the West is a glory departed, .. ."

though "octogenarians who

participated in the traffic will tell an inquirer that never

before were there such landlords, such taverns,

such dinners, such whiskey, such

bustle, or such endless cavalcades of

coaches and wagons ...."

Sentimental friends of the National Road

poured out their feelings in poems like

"The Old Pike":

We hear no more the clanging hoof,

And the stagecoach rattling by,

For the Steam King rules the traveled

world

And the Old Pike's left to die.

The grass creeps o'er the flinty path

And the stealthy daisies steal

Where once the stage horse day by day

Lifted his iron heel.

In the stagecoach and Conestoga wagon

period of rapid national expansion, rich

|

and poor had streamed westward along the road. "Indiana and Ohio received more than ninety thousand inhabitants a year for a generation and at least ninety per cent of them came by way of the Pike," according to Mrs. Carroll Miller in "The Romance of the National Pike" (Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine, 1927). She estimated that "the average number traversing the Cumberland Road every year was close to two hundred thousand." During those years the National Road served the nation effectively in other ways also. As a wilderness was transformed into populous states, the road made it pos- sible for commercial and political ties to be maintained with the United States as a whole. Stagecoaches carried statesmen to the halls of Congress and sped the deliv- ery of mail and newspapers. Exchange of agricultural surplus from the Ohio Valley for the manufactured goods of cities in the East increased the prosperity of both sec- tions. And, as George R. Stewart observed in U. S. 40, "Constitutionally, it set a precedent for the use of national funds for internal improvement." After the National Road had deteriorated under a generation of local use and neglect by the states, some writers penned mournful encomiums of that highway in the belief that it was dead. Searight in 1894 wrote, "The glory of the old road has departed." In 1907 W. J. Massey told a Zanesville audience, "Its life was short; its work is done; its greatness is of the past." They could not foresee that the greatest period of the road was yet to come. To Searight and Massey, the two inventions that were destined to restore its greatness- the bicycle and the automobile-were only frivolous novelties. In the late 1870's courageous riders began mounting the pennyfarthing or "ordi- |

National Road 139

nary" bicycle to prove that

"walking is on its last legs." Perched on a seat above a

front wheel five feet high, a rider

pumped pedals attached to the axle, and "traveled

while sitting" over smooth city

streets. To take a header from one of these vehicles

without broken bones and a mashed face

required the skill of an acrobat.

By 1880 the safety bicycle was being

developed, with a pedal-operated sprocket

and chain system. The diamond frame and

pneumatic tires added comfort to

safety. On this machine cyclists rode

out of the cities and along the old National

Road and other highways. Though these

contraptions frightened horses and

threatened the lives of pedestrians,

owners of the safeties were making "century"

rides of one hundred miles and traveling

the entire length of the National Road by

1885. In 1897 Sherman Granger rode his

wheel, and walked; from Zanesville to

Cumberland in four and one-half days.

Women found knee-length knickerbocker

trousers were appropriate attire for cy-

cling, but still, riding outside the

cities was not a comfortable venture. Cyclists jol-

ted over ruts and crashed into

chuckholes because the National Road and other

roads were in deplorable condition.

Though cyclists demanded better roads, farm-

ers objected violently to being taxed

for the riders' convenience. Why pay taxes for

the passing fad of citified dandies?

The dandies, whose ranks included

engineers and lawyers, organized the League

of American Wheelmen in 1880 for unified

effort to reform the American road sys-

tem. With their magazines L.A.W.

Bulletin and Good Roads, a National Com-

mittee on Highway Improvement, and

allocation of funds to the Good Roads

Movement, the Wheelmen became the first

ongoing organization to advocate im-

proved highways and methods of

construction. L.A.W. members fought for the

right to ride on public thoroughfares

and against the requirement that they dis-

mount when meeting horses. Their persistent

and organized efforts inspired a na-

tional crusade for better roads.

In response to this effort, Congress

created the Office of Road Inquiry in the De-

partment of Agriculture in 1893. With a

budget of only $10,000, it was charged

with gathering and circulating

information on road construction and maintenance.

Devotees of a second invention

collaborated with the cyclists in the crusade for

good roads. They clattered, vibrated,

and roared in four-wheeled "horseless car-

riages" over city streets and

country roads. However, these proponents of good

roads had to fight for federal help much

as their ancestors had done earlier in the

century because constitutional barriers

again stood in the way. It was a long

struggle before income from gasoline

taxes and licenses at last provided funds that

could be used for road construction.

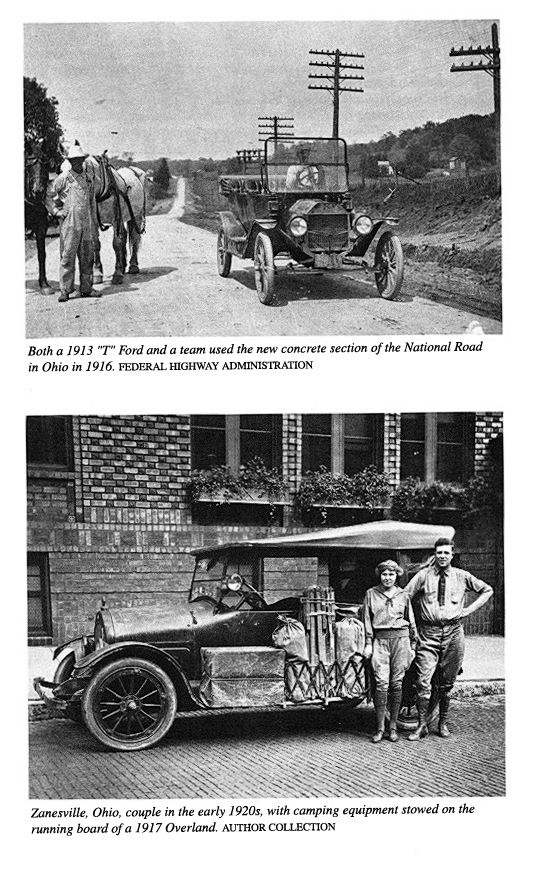

New methods had to be devised since the

macadam surface was no longer satis-

factory. The faster autos fanned the

dust binder from crushed stone surfaces and

blew it away. Some pioneering efforts in

the use of other materials took place in

Ohio. In 1893 the first brick surface on

a rural road was laid on four miles of the

Wooster Pike in Cuyahoga County. That

same year the first Portland cement con-

crete pavement was applied to four

Bellefontaine streets, after a two-year-old test

strip had proved durable. When Congress

appropriated a half million dollars in

1912 for the improvement of mail routes,

$120,000 was allotted for construction of a

sixteen foot wide concrete experimental

pavement on the National Road from

Zanesville westward twenty-four miles to

Hebron.

Neglect of the road by the states had

permitted farmers to encroach on the right-

of-way. Fences, chicken coops, and barns

had been built on the eighty foot width.

140 OHIO

HISTORY

To handle the growing automobile

traffic, engineers needed the entire right-of-way.

Some farmers protested giving up the

land their predecessors had gladly donated

when the road was built.

Since new methods of paving were adopted

slowly, tourists in the early 1900's

prepared for a hazardous adventure over

bad roads. In their Maxwells or Model T

Fords they stowed extra gasoline and a

kit of tools wrapped in a canvas roll.

Donning a long linen duster, a driver

vigorously turned a crank at the front of the

machine, sometimes breaking an arm if

the engine backfired. When the motor

coughed, he ran to the dashboard and

advanced the spark. Climbing into the seat,

he pulled goggles over his eyes,

squeezed a large rubber ball that honked a horn to

clear the track, and lurched forward.

Such brave adventurers roared boldly

into the wild rough yonder without road

signs or maps. They chugged through

flocks of squawking chickens and they terri-

fied horses to bolt, wild-eyed and

snorting, while angry farmers pulled desperately

on the reins. Farmers were again

infuriated when auto drivers helped themselves

to rails from fences to pry their cars

out of ruts. They got even by charging high

prices when autoists knocked on their

doors and begged for a team of horses to pull

their machines out of mudholes.

In the towns pioneer motorists faced

ridicule rather than anger. Boys yelled,

"Get a horse!" A popular song

urged drivers to "get out and get under" when the

engine stopped. Another song title said,

"I'd rather go walking," to an invitation

for an auto ride.

Almost every horse-drawn vehicle of the

early period of the National Road had

its counterpart in the automobile era.

Public transportation was provided at first by

jitney buses. They were touring cars

that waited at public squares for passengers

who sometimes overflowed the seats to

the hood. Later, large buses ran on sched-

ule from city to city and from coast to

coast.

Freight that had been hauled in

cumbersome six-horse Conestoga wagons filled

huge trucks in the automobile age. The

drivers, with headlights that illuminated

the road, drove both day and night.

Instead of the wagon stands of 1840, truck

stops provided lunches and parking space

where drivers could sleep in their cabs.

With faster speeds and heavier loads,

these drivers of Brobdingnagian semis needed

more skill than the wagoners that

Searight praised in The Old Pike. They also pro-

vided a temptation to hijackers. Most

states organized highway patrols to make

roads safer for truckers, family cars,

and tourists.

In response to the demands of auto

owners, roads were gradually improved. In

1916 Congress passed the federal aid

road act and the Bureau of Public Roads was

activated. Of this period Albert C.

Rose, senior highway engineer of that bureau,

later wrote, "The Old Cumberland

Road before long was to be restored to more

than its earlier prestige."

That prestige soon came. More people

traveled on the National Road in au-

tomobiles than by stagecoach in the

earlier period. Then, when few persons had

been able to afford private vehicles,

most travelers had patronized coaches. In the

automobile age, a car usually carried a

single family, or perhaps only the driver.

No road signs directed the early auto

tourists. A copy of The Official Automobile

Blue Book, published by the American Automobile Association

beginning in 1901,

was almost as indispensable as gasoline.

Roadside landmarks guided the tourists.

In the 1910 edition the driver was

informed that 2.2 miles west of Effingham, Il-

linois, he would come to "prominent

crossroads-2 mail boxes on left." At 0.7 miles

142 OHIO

HISTORY

west of Springfield, Ohio, he would

arrive at "Diagonal crossroads, cement works on

left; turn left with telephone poles;

cross trolley." At Hebron, Ohio, "Trolley ends

(1909); continue straight ahead through

covered wooden bridge."

East from Zanesville at 0.4 miles:

"Left-hand branch road, church in center, bear

left with trolley, curving right past

cemetery." When he arrived 9.7 miles east of

Cambridge, Ohio, he found: "Toll-gate,

25�; follow main travel all the way, curving

right and left across stone

bridge." This was an S bridge.

Though rich people patronized city

hotels, most travelers strapped tent, folding

cots, blankets, and food on the running

boards. They camped at night in a school

yard or in a grove near a farmhouse. As

the number of cars increased, the National

Road was paved with a patchwork of dirt,

brick, concrete, and asphalt. Blacksmiths

learned to make repairs on cars, and

country stores sold gasoline.

As the paving improved and the number of

cars increased, gasoline companies is-

sued maps and guides. The 1924 Mohawk

Guide listed campsites, prices, and loca-

btions of stores and garages that sold

gas-at Cambridge City, Indiana: "City camp

free; 50� after third day; cook house;

good grass." In Ohio, where the National

Road had been designated State Road No.

1, the Neil House charged $3 to $6 for a

room and $1.25 for dinner. East of

Columbus thirty-six miles was "Majestic camp,

50�; tables under roof and shower;

cabins." Star Camp two miles east of Zanesville

charged 50�; "shower bath,

10�." Many families added to their income by accom-

modating travelers in tourist homes.

Motel luxuries came later.

More cars and faster speeds created a

demand for highway signs. Drivers did not

always have beside them a navigator to

read The Blue Book, and it was dangerous

to read directions and watch the road at

the same time. Long before the speed of

cars reached seventy miles an hour,

there were wrecks. Governor Vic Donahey of

Ohio ordered white crosses erected on

the sites of fatal accidents in the hope of mak-

ing drivers more cautious. Maps of

highway routes and road signs became neces-

sary, though road atlases of the entire

country were not generally available until the

1920's.

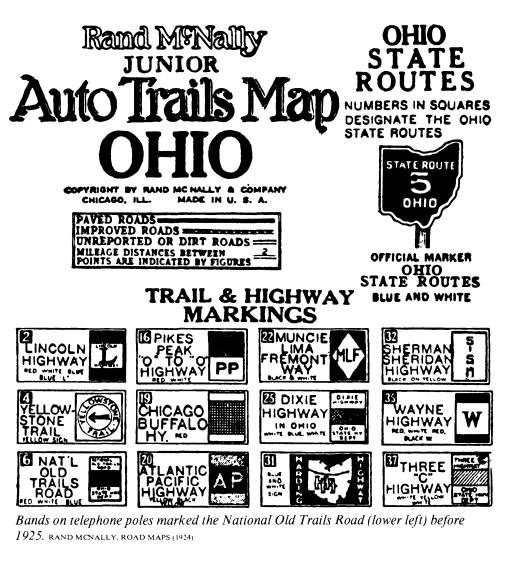

In the absence of any governmental

action, private commercial promoters linked

together strings of existing roads and

gave them names. The routes were marked

by bands of different colors on

telephone poles. George R. Stewart stated in U. S.

40 that there were at least 250 of these routes. Among them were the

Lincoln High-

way, Old Spanish Trail, and Dixie

Highway. Merchants, restaurants, and hotels

paid the promoters to route these

highways past their places of business.

In 1907 the Missouri Old Trails Road

Association advocated restoration of the

National Road and its extension from

coast to coast. At Kansas City in 1912, under

the inspiration of Judge J. M. Lowe, the

association included the National Road as

part of its designation of the National

Old Trails Road. That route, which extended

3,096 miles from Washington, D.C., to

Los Angeles, was identified by red, white,

and blue bands on telephone poles. With

a few changes, such as the dip through

Dayton, Ohio, the old National Road was

the main segment of the National Old

Trails Road.

Pages of verse have been written about

the romantic old stagecoaches-which had

some charm when viewed at a distance. In

reality, the passengers were bumped up

and down and jolted right and left. How

much more comfort and freedom the

drivers of autos enjoyed on the Old

Trails Road!

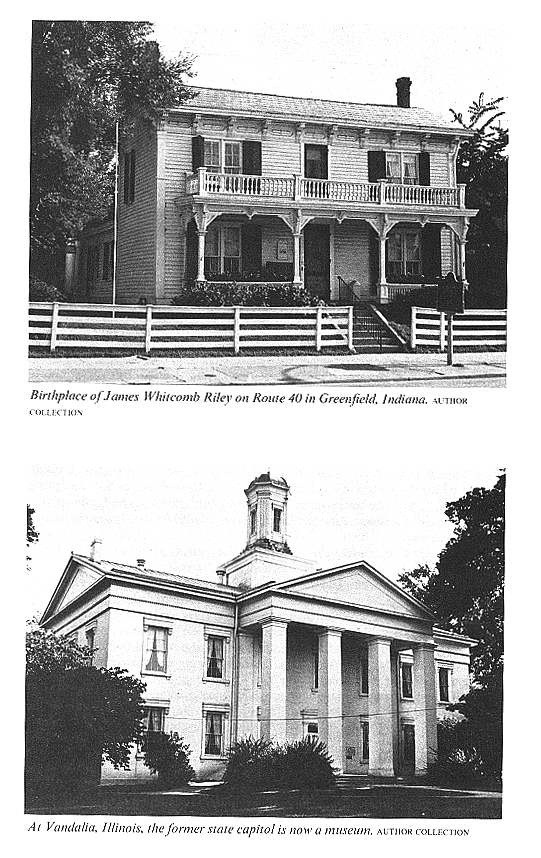

They could stop for sightseeing at Fort

Necessity and Braddock's tomb in Penn-

sylvania, at the Zanesville art

potteries in Ohio, and at James Whitcomb Riley's old

|

swimmin' hole in Greenfield, Indiana. If an antique shop or roadside stand ap- pealed to them, they pulled to the side of the road to browse. At mealtime they could eat a picnic lunch in an oak grove or dine at a nearby restaurant. The National Road did not quite lose its identity in the National Old Trails Road, which was one of the better commercially promoted highways. Because these roads were linked together by private effort, they lacked coordination and official sponsor- ship. In 1925 a Joint Board on Interstate Highways recommended a national grid system for numbering east-west routes with even numbers by tens and north-south highways with numbers ending in one or five. Thus, in 1926, the old National Road became part of U. S. 40. Ohio can claim several "firsts" in highway progress. Considering these records and the original enabling act which contained the provision for a highway con- necting the Northwest Territory with the eastern states, it is appropriate that a Na- tional Road Museum to memorialize the historic importance of the famous highway should be located in Ohio. The museum ten miles east of Zanesville on Route 40 |

|

portrays the history of what for more than a century was the Main Street of Amer- ica, "the first major road-building venture of the Federal Government." Today Interstate 70 parallels the old National Road. For speeding over the most miles in the shortest time, I-70 offers the best route. But to enjoy the scenery, meas- ure the distance by old milestones, browse in antique shops, dine at picturesque roadside inns, and enjoy leisurely travel over historic ground, the six hundred mile stretch of Route 40 between Cumberland, Maryland, and Vandalia, Illinois, is the best choice. You will be following in the stagecoach tracks of the pioneers. James Ball Naylor celebrated the route in his poem, "The Old National Road": From the sweet-smelling Maryland meadows it crawled, Through the forest primeval, o'er hills granite-walled; On and up, up and on, 'till it conquered the crest Of the mountains-and wound away to the West. 'Twas the Highway of Hope! And the pilgrims who trod It were Lords of the Woodland and Sons of the Sod; And the hope of their hearts was to win an abode At the end-the far end of the National Road. |

National Road 145

BIBLIOGRAPHY OF NATIONAL ROAD SOURCES

Bailey, Kenneth P., The Ohio Company

of Virginia and the Westward Movement 1748-1792.

Glendale, Arthur H. Clark Company, 1939.

Bruce, Robert, The Old National Road.

Washington, D.C., American Automobile Associ-

ation, 1915.

Burns, Lee, "The National Road in

Indiana," Indiana Historical Society Publications, VII

(1919), 209-37.

Cleland, Hugh, George Washington in

the Ohio Valley. Pittsburgh, University of Pittsburgh

Press, 1955.

Davis, Charles Henry, National Old

Trails Road, Ocean to Ocean Highway. Boston, Everett

Press, 1914.

Freeman, Douglas Southall, George

Washington, Vol. VI. New York, Charles Scribner's

Sons, 1954.

Fuller, Wayne E., "The Ohio Road

Experiment 1913-1916," Ohio History, LXXIV (1965),

13-28.

Gallatin, Albert, The Writings of

Albert Gallatin, edited by Henry Adams, Vol. I. New

York, Antiquarian Press Ltd., 1960.

Gray, Ralph, "From Sea to Shining

Sea," National Geographic, 120 (1961), 1-61.

Hardin, Thomas L., "The National

Road in Illinois," Illinois State Historical Society Jour-

nal, LX (1967), 5-22.

Hatcher, Harlan, The Buckeye Country.

New York, H. C. Kinsey & Company, 1940.

Hulbert, Archer Butler, The Cumberland

Road, Vol. X, Historic Highways of America.

Cleveland, Arthur H. Clark Company,

1904.

---"The Old National Road-The

Historic Highway of America," Ohio Archaeological

and Historical Quarterly, IX (1901), 405-519.

---Washington's Road (Nemacolin's

Path), Vol. III, Historic Highways

of America. Cleve-

land, Arthur H. Clark Company, 1903.

Hunt, John Clark, "Over the

Alleghenies into History," American History Illustrated, V

(1970), 24-33.

Jefferson, Thomas, The Works of

Thomas Jefferson, collected and edited by Paul Leicester

Ford, Vols. II, III, X, XI, XII. New

York, G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1904-05.

Jordan, Philip D., The National Road.

Indianapolis, Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1948.

Lowdermilk, Will H., History of Cumberland,

Maryland. Washington, D.C., James Anglim,

1878.

Lowe, J. M., The National Old Trails

Road. Kansas City, Mo., the author, 1924.

Mason, Philip P., The League of

American Wheelmen and the Good-Roads Movement,

1880-1905. Ann Arbor, University Microfilms, 1957.

McKee, Harley J., "Original Bridges

on the National Road in Eastern Ohio, Ohio History, 81

(1972), 131-44.

Miller, Mrs. Carroll, "The Romance

of the National Pike," Western Pennsylvania Historical

Magazine, X (1927), 1-37.

Ristow, Walter W., "A Half Century

of Oil-Company Road Maps," Surveying and Mapping,

XXIV (1964), 617-37.

Searight, Thomas B., The Old Pike. Uniontown,

Pa., the author, 1894.

Searight, Thomas B., The Old Pike; An