Ohio History Journal

DAVID A. GERBER

Lynching and Law and Order:

Origin and Passage of the

Ohio Anti-Lynching Law of 1896

Americans are increasingly discovering

that the United States has had a relatively

lawless and violent history and that the

problem of violent social disorder has con-

tinually plagued the nation. The truth

of this assertion as well as its implication for

a deeper understanding of the country's

social processes have tended to elude lib-

eral scholars bent on tracing the steady

progress of American society toward higher

civilization and on constrasting the

glowing promises of a democratic New World

with the corruption of monarchical

Europe. But the social traumas of the 1960's

have seriously undermined the

possibility of continuing to accept the old synthesis

of our past, with its promise of future

and inevitable glory. By heightening the con-

tradiction between what we have

professed and the way we have actually lived, and

by shaking our once firm confidence in

the liberal values to which traditional histo-

rians have responded, the last decade,

to which the late Richard Hofstader once re-

ferred as an "historical

slum," has forced us to confront the peculiar Americanness

of the Nat Turner Revolt, the Battle of

the Little Big Horn, and the Homestead

Strike. The 1960's have forced us at the

same time to examine the potentials within

our social order for curbing brutal,

anti-social urges.1

Given the long preoccupation of American

society with the problem of black-

white relations in the United States, it

is not surprising that racial violence has been

one of the most persistent of all types

of American social violence. The bitter, irra-

tional prejudices, the deep-seated

fears, the calculated manipulation of racial antag-

onisms for personal or corporate gain,

the cowardliness and evasiveness with which

we have confronted the fundamental

contradiction of our social values which racism

has posed: these have not readily lent

themselves to resolution within the estab-

lished social and political channels for

resolving conflict. At times, therefore, black-

white relations have seemed to take on

characteristics of a social war rather than to

1. For some outstanding reappraisals of

violence in American history, see Hugh David Graham and

Ted Robert Gurr, eds., Violence in

America: Historical and Comparative Perspectives (New York, 1969);

Richard E. Rubenstein, Rebels in

Eden: Mass Political Violence in the United States (Boston, 1970); Rich-

ard Hofstader and Michael Wallace, eds.,

American Violence: A Documentary Record (New York, 1970).

Mr. Gerber is an Assistant Professor in

the Department of History, State University of New York at

Buffalo.

|

|

|

serious attempt to legislate lynching out of existence was made. The product of a collaboration between Harry C. Smith, a black state legislator and editor of the suc- cessful black newspaper, the Cleveland Gazette, and Albion Tourgee, a well-known white proponent of racial equality, the Ohio anti-lynching law of 1896 was a model for anti-lynching legislation in other states for years to come. The origin of the Ohio law, as it developed from state and national events and the milieu in which it was produced, have yet to receive scholarly attention. Nor in fact have the popular attitudes which sustained mob violence and made difficult the curbing of lynching received much treatment by historians. The tendency has been to see lynching as simply one more manifestation of racial intolerance, however lamentable, but almost as immutable as the racial hostility which gave rise to it.7 Though lynching was sustained by racial prejudice and certain cultural attitudes, it was behavior that ran counter to many of the political and social values in which nineteenth century Americans professed belief. Thus lynching and other forms of retributive mob violence presented serious problems of justification for the commu- nities in which they occurred. This was particularly the case for the respectable middle class citizens in smaller northern communities where, according to local newspapers, "the good citizens" and "men of high standing" were often said to be

7. Generally written by those participating in the struggle against lynching on one level or another, the historical literature on the subject has been relatively weak. The two best known works are Walter White, Rope and Faggott, A Biography of Judge Lynch (New York, 1929) and Frank Shay, Judge Lynch, His First Hundred Years (New York, 1938). |

|

|

|

who with the benefit of a just hearing might have been cleared of the charges against them.5 The majority of lynchings, of course, occurred in the rural South where over 90 percent of the black population lived at the turn of the century. Yet, there were lynchings and attempted lynchings in the North as well, particularly in the southern and central counties of Ohio and in neighboring Indiana and Illinois where a rela- tively large (for the North) number of blacks lived, often in an uneasy peace with large numbers of transplanted southern whites and their descendants.6 It was in Ohio, in response to a rash of lynchings in the early 1890's, that the nation's first

5. The N.A.A.C.P.'s investigation of the offenses with which victims of lynching were charged yielded the following for blacks: 35.8% murder; 19% rape; 9.4% attacks upon women; 9.5% "other crimes against persons"; 8.3% crimes against property; 12% miscellaneous crimes; and 5.6% absence of crime." The last category included such causes as "testifying against whites," "suing whites," "race prejudice," "defending himself against attacks," and even "wrong man lynched." "Rape" did not necessarily mean a con- summated sexual assault in the South of that day; entering a woman's room, a vague look of desire, a suggestive remark, or a touch were enough for a lynching to be justified on the basis of "rape." The cat- egory "attacks upon women" differed only in that newspapers, from which the N.A.A.C.P. gathered its evidence on lynching, stated the "rape" had not been committed. See N.A.A.C.P., Thirty Years of Lynch- ing, 9-10, 36. It is a strong comment on the psychodynamics of American racism that though "rape" and "attacks upon women" only constituted some 28.4% of the charges against black victims of lynch mobs, lynching was often defended only on the basis of it being the sole possible deterrent for interracial rape; see Baker, Following the Color Line, 198. At the root of the preoccupation with interracial rape was the belief in the uncontrollable sexual lust of Negroes, a belief which received a great deal of discussion in contemporary publications; see Frederickson, Black Image in the White Mind, 273-288. 6. N.A.A.C.P., Thirty Years of Lynching, 31, 63-64, 85. |

34

OHIO HISTORY

consist of the ordinary give and take of

economic and social competition which have

generally characterized relations among

the various white groups found in Ameri-

can society.2

The late nineteenth and early twentieth

century was a time of increasing racial

tension. Promises of congressional

Reconstruction were being repeatedly broken or

ignored, and the black American was

sinking deeper and deeper into second class

citizenship. With the growing influence

of social Darwinism on racialist thought,

racial attitudes hardened throughout

society; at last intellectual legitimacy seemed

to have been found for the long felt

desire for the subordination of blacks. In the

South, increasingly after 1890,

legislation took the vote from the black man and be-

gan to segregate him in all areas of

social life, while sharecropping and the crop lien

system continued to enmesh him in a

cycle of debt and poverty. In the North, even

without specific legislation, the color

line hardened. Gains that blacks had made in

the twenty-five years since the end of

the Civil War through legislation and enlight-

ened public sentiment which allowed for

freer access to public accommodations and

the public schools were now increasingly

questioned and compromised.3

To a society that took pride in its

commitment to law, order, and justice, one of

the most disturbing manifestations of

the deterioration of race relations was the

growth of mob violence aimed at blacks.

Between 1889 and 1918, according to sta-

tistics gathered by the National

Association for the Advancement of Colored People

(N.A.A.C.P.), 2,522 blacks were the

victims of lynch mobs nationwide, constituting

over 78 percent of the total number of

victims of lynching. In addition, numerous

urban race riots, which were generally

attacks by white mobs upon black neighbor-

hoods, took place throughout the nation.4

The most common incitant of such mob

violence against blacks was what

contemporaries called "Negro crime," a euphe-

mism which more often than not meant not

actually crimes upon persons or prop-

erty, but rather assaults upon the basic

canons and the daily etiquette of the Ameri-

can racial caste system. Thus, not

stepping out of the way when whites walked

down the sidewalk or the showing of the

least sign of interest in a white woman on

the part of a black man might be

examples of "Negro crime" in the South of that

day. By its very nature lynching denied

its victims the right to their say in court.

We shall never know, therefore, how many

persons suffered violent deaths, labeled

"fiends" or "brutes"

by the press for crimes they were alleged to have committed,

2. The most important recent effort at

providing theoretical perspectives for an understanding of racial

violence in the United States is Allan

Day Grimshaw, ed., Racial Violence in the United States (Chicago,

1960).

3. On the deterioration of race

relations in the South, see C. Vann Woodward, The Strange Career of

Jim Crow (New York, 1955), 11-108; in the North, see Ray

Stannard Baker, Following the Color Line

(New York, 1908), 111; John Daniels, In

Freedom's Birthplace: A Study of Boston Negroes (New York,

1967), 29-49; Gilbert Osofsky, Harlem:

The Making of a Ghetto (New York, 1966), 4-52; Allen Spear,

Black Chicago (Chicago, 1967), 28-49. On the development of

intellectual racism and racialist thought,

see Thomas Gossett, Race: The History of an Idea in America

(New York, 1965), 144-175; George Fred-

erickson, The Black Image in the

White Mind (New York, 1971), 256-282.

4. National Association for the

Advancement of Colored People, Thirty Years of Lynching in the

United States, 1889-1919 (New York, 1919), 7-8, 29-41, 85. These riots bear

greater resemblance in type

to the Russian "pogroms" than

to the urban riots of 1919 in which blacks offered resistance to white in-

vaders or the ghetto insurrections of

the late 1960's. The riots of the late 19th century and the early years

of the 20th found blacks generally not

offering armed resistance to white invasions of their neighbor-

hoods; for a typology of racial

violence, see Grimshaw, Racial Violence in the United States, 105-115.

Ohio Anti-Lynching Law, 1896

37

the leaders and defenders of lynch mobs.8

The primary rationale for lynching was

that certain heinous crimes, especially

rape and murders of unusual brutality

called for setting aside traditional legal proc-

esses and in their place substituting a

"higher law," the force of which was, in the

case of lynching, immediate and final

punishment at the hands of the enraged com-

munity. "Higher law" is and

has been an elusive concept. Commonly the term has

been used to describe an unwritten code

of justice, informed by the deepest human

moral passions, which supposedly lies

buried in the consciousness of all moral indi-

viduals and is ready to manifest itself

when a sense of outrage is quickened. The

written statutes, with their technical

precision, cannot, it has been said by exponents

of "higher law," embody this

profound sense of justice. Also, at times, the statutes

themselves have not been free of error;

they have on occasion committed societies to

unjust laws and untenable legal

processes. Under these circumstances, "higher

law" was used by individuals and

groups to circumvent statutes according to their

conception of justice.

The concept of "higher law"

has tended, therefore, to make strange bedfellows

since acts of cruel vengeance as well as

acts of idealism have been committed in its

name. In the nineteenth century, for

example, we find it was used by the enemies

of the Negro-the lynch mob and its

defenders-and by the allies of the Negro-the

abolitionists. The lynch mob, however,

was not bearing witness against the sub-

stance of unjust laws, as were the

abolitionists. It was, instead, simply impatient

with the slowness of legal processes and

the inability of law enforcement agents,

who were often held in extreme contempt

because of their commitments to such

processes, to exact the bloody and

immediate revenge demanded. Holding agents

of the law in contempt, the mob rejected

incarceration or trial of the accused; only

death would suffice if its conception of

justice was to be satisfied. Neither the mob

nor its defenders sought to explain

their actions by a reasoned statement of purpose,

as was most often the case with

law-breaking abolitionists. Rather, mobs and their

defenders revealed the purely vengeful

and irrational bases of their behavior when

they justified mob violence by employing

excessively passionate rhetoric. This is

evident in the editorials of an Ohio

newspaper which invoked "higher law" to justify

a lynching of an accused rapist in its

community: "There are occasions when statute

law abdicates in favor of higher law. In

dealing with human monsters each com-

munity is and always will be a law unto

itself. . . . Law is a good thing; order is

greatly to be desired. But the holy

rights of humanity and God's eternal justice are

above law and order." Under these

circumstances, the "higher law" is of course no

8. The author's perspective on lynching

is largely the product of a study of incidents related in various

secondary sources and of intensive

research into ten lynchings of blacks which occurred in Ohio during

the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

These took place at Oxford in 1877 and 1892; Sandusky, 1878;

Galion, 1882; Jamestown, 1887;

Winchester, 1894; Rushsylvania, 1894; New Richmond, 1895; Urbana,

1897; and Springfield, 1904. I have also

studied several serious, but unsuccessful attempts at lynching

which took place in Ohio at Washington

Court House, 1894; Akron, 1900; Lorain. 1903; and the well-

known Cincinnati riot of 1884.

On the participation of the "best

people" and the "good citizens" in mob violence, see, for

examples,

West Union People's Defender, January

4, 11, 1894, which said of a local mob that it was "composed of

the best men of the northwestern part of

the county"; Bellefontaine Examiner, May 17, 1894, which

spoke of local mob members as "ordinarily

good citizens." It must not be assumed, however, that par-

ticipation of persons of high status was

always the case. As of now, we know little about the social com-

position of lynch mobs.

38

OHIO HISTORY

law at all but is simply a rationale for

unleashing the passions for vengeance in an

angered mob.9

Also underlying the invoking of the

"higher law" where characteristically Ameri-

can attitudes toward popular

self-government, the evils of political centralism, and

the inefficacy of judicial processes. To

those who argued that the "higher law" was

simply a shameful excuse for lawlessness

and sadistic brutality, defenders of lynch-

ing argued that the ultimate standard of

justice in American democracy was the

people, not the courts and the laws,

though the latter were of course the creation of

the citizenry itself through a political

process which most Americans claimed to re-

spect. "The people rule this

country," said an Ohio newspaper in defense of the

lynching of a black accused of raping a

white woman, "and they have decreed that

in such cases every such monster shall

die."10 At the base of this demand (for the

assertion of unlimited sovereignty by an

enraged people) lay not only a feeling of

the special horror of interracial rape

itself or of other serious, violent crimes, but

also a belief that traditional legal

processes were much too lenient and inefficient,

that the courts could not be trusted to

mete out the people's conception ofjustice.

An unmistakeable disgust with Ohio's

courts, for example, was present during the

early 1890's, and the state's newspapers

often isolated this as an important casual

factor in several of the attempts of

enraged mobs to take the law into their own

hands. The respected Ohio State

Journal of Columbus stated in 1894 in connection

with a proposal for anti-lynching

legislation: "The leniency of the courts in this

state, the long-drawn-out machinery of

the law, and the ease with which a convict

who has any friends to push his claim

for parole or pardon can secure his early re-

lease from prison, have much to do with

the growing displays of lynch law in Ohio."

Only when a community came to be assured

that murderers and serious offenders

would be executed or receive long prison

sentences after speedy trials, concluded

the Journal, would mob

retribution cease.11

A lack of confidence in the courts and

elected and appointed law enforcement

agents helped to create the phenomenon

of the "law and order" mob: a mob which

rioted against its own legal agents in

the name of the preservation of order and the

substance, rather than the form, of

justice. Such mobs were involved in many of

the more typical lynchings of those

accused of crimes of various kinds. Two of the

most destructive urban riots of the late

nineteenth century were attributable to "law

and order" mobs. At Cincinnati in

the early 1880's anger over the failure of local

law enforcement agencies, which many

felt were the tool of venal politicians, to

prosecute those charged with serious

crimes had been brewing for years. Many of

the city's most respected citizens had

come to feel the need for direct action against

corrupt courts and police, and the

possibility of the formation of vigilante groups

9. Urbana Citizen and Gazette, June

10. 1897. In reference to the same lynching, the Urbana

Champaign Democrat neatly wove the themes of the higher law and the male

responsibility for the pro-

tection of female chastity, saying,

"The people of Urbana . . . have no apology to make for the lynching

of the negro brute .... They did their

duty and they are glad to have the world know that there is

enough of virtue and manhood in this

good city ... to visit the same righteous punishment upon every

such vile monster who invades their

homes and assaults their mothers, wives, and daughters." Ibid.,

June 10, 1897.

10. Urbana Champaign Democrat, June

10, 1897.

11. Ohio State Journal (Columbus),

February 23, 1894. For a protest against the interference of "mere

technicalities," in the words of

the Batavia Clermont Sun, with speedy retributive justice, see ibid.,

August

28, 1895.

Ohio Anti-Lynching Law, 1896

39

was widely discussed. These complaints

crystallized in late March 1884 when a

young white man, a confessed murderer

whose father was thought to have spent

huge sums of money in his defense, was

given a relatively light sentence by a local

court. Charges of "fix" were

in the air as indignation swept the city. Shortly after

a public protest meeting, lynch mobs

attacked the jail where the prisoner was held.

Frustrated there by police resistance,

mobs battled police in the streets for several

days and burned the city's courthouse,

the symbol of their outrage, to the ground.12

Another "law and order" riot

occurred at Akron in 1900 when a mob, frustrated in

its attempt to lynch Lewis Peck, a black

man accused of raping a child, battled po-

lice for several hours and destroyed the

city's courthouse.13

Even though members of the mob were

willing to battle against police corruption

and the courts' failure to be concerned

with retribution, they were not above cor-

rupting the customary legal

investigative procedures, which followed lynchings, for

the sake of protecting their members

from legal prosecution. Thus, the mob's rem-

edy served only to worsen the disease.

Coroners' inquests, mandatory in cases of all

violent deaths, for example, seemed to

almost always, when the victims met their

deaths at the hands of lynch mobs,

result in the typical verdict: "The deceased came

to his death at the hands of persons

unknown."14 Such a verdict was hardly ever

warranted. Most lynchings during the

period took place in or near small towns

where people were generally known to

each other. Even when accomplished at

night, lynchings were rarely intended to

be secret; indeed, the desire to create a pub-

lic example of just punishment was often

present. Even where conspiracies did ex-

ist, they hardly were so closed as to

remain a mystery very long to local residents.

The tumult caused by an attempt to wrest

a prisoner from a jail also often worked

against the possibility of secrecy.

Whether out of sympathy for the mob's

work or in fear of jeopardizing political

careers, public officials often

displayed reticence in pursuing mob members. In the

South, coroners' inquests, when held at

all, usually were the only inquiries made

into lynchings. In the North, however,

investigations beyond the inquest were

more common, whether in deference to

enraged public sentiment against lynching

or to the Negro vote. In Ohio, for

example, investigations by grand juries and spe-

cial state initiated inquiries into the

activities of local officials frequently occurred,

but they usually accomplished nothing,

or at most rendered few indictments. Local

public prosecutors rarely showed much

zeal in seeking indictments against the per-

sons who elected them.15

Black responses to lynchings were a

complex mixture of anger and resentment

and fear and shame. Many, of course,

felt that the race, so recently admitted to full

citizen's status, was on trial in the

nation, and the blacks accused of crimes hurt the

image of the Afro-American. A common

immediate response, especially among

blacks of higher status was to lament

the shame the accused had brought upon the

12. Laird Kleine, "Anatomy of a

Riot, " Historical and Philosophical Society of Ohio, Bulletin, XX

(1962), 234-244.

13. Akron Democrat, August 23,

1900.

14. J. E. Cutler, "Proposed

Remedies for Lynching," Yale Review, XIII (May 1904-February 1905),

209.

15. Ibid.; Sandusky Register, September

17, 1878; West Union People's Defender, January 18, 1894;

Bellefontaine Weekly Examiner, June

7, 1894; Columbus Dispatch, August 9, 10, 11, 1897; Cleveland Ga-

zette, August

14, 1897; Baker, Following the Color Line, 208-209.

40 OHIO

HISTORY

race. Soon after the lynching of a young

man, thought to have raped a prominent

newspaper woman, at Urbana, Ohio, in

1897, Ralph W. Tyler, a Columbus black

newspaperman and political operative,

wrote to a friend of his frustration over the

defense of the young man by many blacks,

"I have no sympathy for the brute that

committed the rape .... There is always

a class of our people who are ever ready to

rush to the defense of some damned

brute, even at the expense of bringing disaster

to themselves, their families, and their

race, to say nothing of the general public at

large."16 Similarly, an

Akron black stated after the 1900 riot and attempted lynch-

ing in that city, "It is hard to

think that one wretch has made it so that I cannot walk

down the street and look a white man in

the face. I have lived here for 30 years,

have never been in any trouble, and am a

taxpayer. A scoundrel who has resided

in Akron less than a year commits a

crime that throws disgrace on every member of

his race. There is not a negro in the

city, who is not severe in his denunciation of

the ravisher Peck. There are many of

them who say that they would have been

glad to have had a hand in lynching him.

Akron negroes, as a whole are law abid-

ing citizens."17

Ironically, this statement revealed the

same willingness to break the law in order

to preserve the integrity of the law, as

demanded by the white "law and order" mob.

Fortunately, other blacks-no matter how

angered they were by lynching or the

crimes that were reputed to bring it

about-were more circumspect, realizing that in

the deteriorating racial climate of that

time blacks had nothing to gain from sanc-

tioning, let alone participating in, mob

violence. While many felt the situation of

the early 1890's to be desperate, few

spoke publicly of the possibility of retaliatory

violence. Though a national race

conference held at Cincinnati in July 1892 to dis-

cuss the alarming rise in lynching did

pass a resolution suggesting that black troops

and officers be trained at a proposed

Afro-American military academy supported by

the Federal Government and stationed at

"colored centers of population" for the

stated purpose of aggrandizing "the

colored factor in national glory," even this

veiled proposal for the establishment of

a black deterrent seems never again to have

been seriously discussed.18 Most

race leaders of the time would probably have

agreed with black Cleveland attorney and

political leader John P. Green who stated

in a newspaper article sometime later

that violence as a tactic for dealing with the

race's deteriorating status "is

utterly impractical and entirely out of the question,

not to be considered for a moment....

Even dynamite, that all potent leveler of

the weak and the strong ... is mewed up

in the custody of the [white] majority."19

While eschewing retaliatory violence,

blacks and their allies did not stop the

search for methods to put an end to

lynching. Not only were the number of lynch-

ings dangerously high, but lynching was

increasingly becoming a racial phenome-

non. While the number of lynchings in

the United States from 1884 through 1886

had been 533, of which 199 (37%) had

been of blacks, and from 1887 through 1889

had been 427, of which 233 (54%) had

been of blacks, by 1890-1892 blacks had

come to constitute 370 of the 511

persons lynched, a full 72 percent of the total.

16. Ralph W. Tyler to George Myers, June

5, 1897. George Myers Papers, Ohio Historical Society.

17. Akron Democrat, August 23,

1900.

18. Cleveland Gazette, July 9,

1892.

19. Ibid., October 6, 1906.

Ohio Anti-Lynching Law, 1896

41

Lynching reached a peak in 1892. In that

year alone 226 persons (155 blacks,

68.5%) met death at the hands of lynch

mobs, an average of over four persons per

week.20

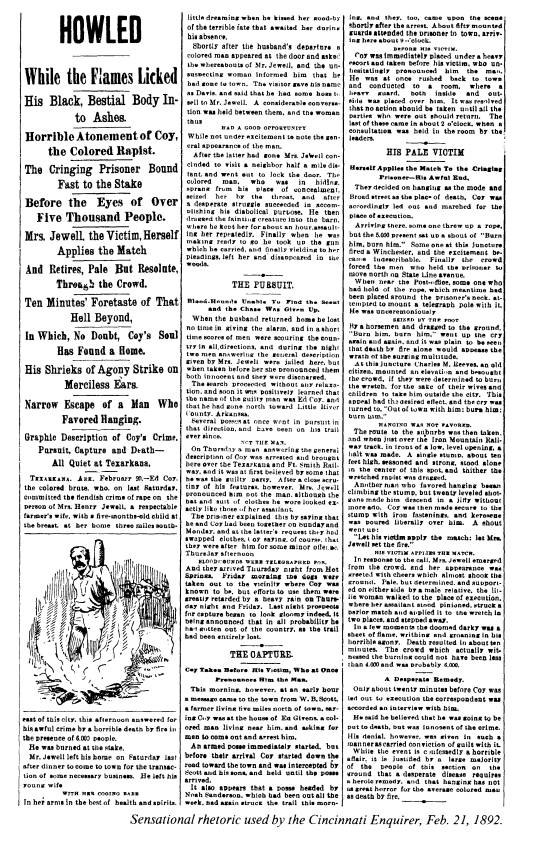

Fueling the fire of violent racial

hatred, the daily press increasingly utilized a sen-

sationalistic treatment of lynching

which irresponsibly exploited the existing shock

value of assaults upon racial and sexual

codes in order to attract and then hold a

mass readership. Typical of many

newspapers of the time were such headlines as:

"HE MUST DIE, IF NOT IN THE LEGAL

STYLE THEN BY THE LYNCH

ROUTE" and "OUGHT TO BE

LYNCHED." These accompanied articles that

spoke of the "lecherous

negro," the "colored brute," and the "colored

fiend."21

Some papers, perhaps unwilling to sell

newspapers by the intentional use of such

techniques, nevertheless, showed a

considerable lapse of professionalism in their de-

pendence on rumor and their uncritical

acceptance of local opinion in reporting

lynchings. Those papers dependent on the

national wire services, particularly the

Associated Press, simply printed stories

as they received them. The Associated

Press, especially, was criticized by

Negroes for its prejudicial, sensationalistic treat-

ment of the lynching of blacks and for

its employment of all the code words and

catch phrases of the day in discussing

the crimes which were reputed to result in

lynching. A black anti-lynching tract

published in 1892 singled out the AP for its

role in making lynching respectable:

The Associated Press, that agent so

powerful for the enlightenment of the public and the for-

mation of public opinion, gives its

assent to murder by branding the victims [of lynching]

with vile epithets, and many sleep in

bloody graves, stigmatized as "black fiends," "negro

monsters" and the like, who with

fair trials might have gone free.22

Through these terrifying, bloody days of

the early 1890's, Ohio blacks held prayer

meetings and passed resolutions, often

demanding that federal and state authorities

involve themselves in the struggle

against mob violence, particularly in the South.

But it was the lynching of a black

teenager closer to home in Adams County, Ohio,

in January 1894 which prompted black

leaders in the state to begin a serious search

for a legislative remedy for lynching in

Ohio. The boy had been taken into custody

in the first week of December by local

officials and charged with complicity in the

brutal murder of an aged farm couple

living in a remote section of the county.

Amidst threats of lynching, local

officials had taken him to jail in the next county.

When these threats subsided early in

January, he was returned to face trial only to

be seized quickly by a mob, said by a

local newspaper to be composed of the "best

men" of the community, and lynched.

No indictments were made in the case, how-

ever, because public sentiment,

including members of the grand jury, in the county

20. N.A.A.C.P., Thirty Years of

Lynching, 29: Grimshaw, Racial Violence in the United States, 58.

21. The headlines and racial epithets

quoted here are from the Cincinnati Enquirer, which was typical

of those papers which treated lynching

in a sensationalist manner. Cincinnati Enquirer, November 9,

1890, August 17, 1891, January 15,

February 21, 1892. On the paper's treatment of lynching, see two un-

published Howard University M.A. theses:

Shirley M. Smith, "The Negro 1877-1898, as Portrayed in the

Cincinnati Enquirer " (1948),

and Sebron Billingslea, "The Negro as Portrayed in the Cincinnati Exqui-

rer, 1901-1920" (1950). Billingslea has characterized

the Enquirer's position on mob violence as "a full

adherence to lynch law in so far as

Negroes were concerned." Ibid., 80-81.

22. A public letter: "To the

Colored People of the United States," March 1892. Item 6156, Albion W.

Tourgee Papers, Chautauqua County

Historical Society, Westfield, New York.

Ohio Anti-Lynching Law, 1896

43

was in agreement with the mob, according

to newspaper reports.23

Immediately after the knowledge of the

lynching reached Columbus, Ohio's three

black state legislators, William H.

Clifford and Harry C. Smith of Cleveland and

Samuel B. Hill of Cincinnati, met with

Governor William McKinley in the hope

that he might be persuaded to use his

influence to pressure county officials to take

legal action against the mob. Strongly

motivating the three was, according to

Smith, the knowledge that though

lynching was fostered in the South, it-as well as

other forms of contemporary racial

discrimination-were "spreading north and

westward entirely too fast." The

three also called for petitions to the state legisla-

ture demanding an investigation of the

Adams County affair. Some weeks later,

Hill introduced a resolution denouncing

the lack of action by county officials and

appealing to "the law-abiding

citizens of Adams County to use their utmost endeav-

ors to ascertain the perpetrators of

this foul crime... ."24

Such efforts, while doubtless well

intentioned, availed little. Though the gover-

nor denounced lynching strongly, as

"murder-pure and simple," both he and the

legislature had few precedents upon

which to base the intervention into local affairs

that the black legislators requested. It

remained for Harry C. Smith and his long-

time friend and colleague in the

struggle for black rights, Albion Tourgee, to pro-

pose a law which would deal

comprehensively with lynching.

Though many years separated the

thirty-one year old Smith, then serving the first

of three terms he would have in the Ohio

House of Representatives, from the

middle-aged, Ohio-bred Tourgee, who had

been a Radical Republican official in

North Carolina during Reconstruction,

the two were united in what, to contempo-

raries, was a radical stand on the

southern question. Both urged the necessity of a

continuing commitment of both the

Federal Government and the Republican party

to the maintenance of the rights of the

southern freedmen at a time when such a

commitment was quickly fading. In their

pursuit of public support for racial equal-

ity and full citizenship for blacks,

both Smith and Tourgee through their writings,

speeches, and organizational activities

sought to mobilize public opinion against dis-

franchisement, segregation, and

anti-black mob violence. When Tourgee founded

a National Citizens' Equal Rights League

in 1890 to bring together all organizations

working for black rights around a common

program, Smith was an enthusiastic sup-

porter. During the early 1890's Smith's

Cleveland Gazette was always open to re-

prints of Tourgee's

"Bystander" column, which appeared regularly in the Chicago

Inter-Ocean. Later in the decade articles from Tourgee's own Basis:

A Journal of

Citizenship also appeared in the Gazette.25

Tourgee was no stranger to the fight for

a legislative response to lynching. For

several years, as director of his

citizens' league, he had campaigned actively for the

passage of federal anti-lynching

legislation which would establish the principle of

23. West Union People's Defender, December

21, 28, 1893; January 4, 11, 18, 25, February 15, 1894;

Cincinnati Enquirer, January 13,

1894; Cleveland Gazette, January 20, 27, February 3, 1894. On the first

black anti-lynching activities during

the 1890's, see Cleveland Gazette, May 7, 14, 28, June 4, 11,

July 9,

1892.

24. Ohio State Journal (Columbus),

January 18, 26, 1894; Cleveland Gazette, February 10, 17, March

10, 1894.

25. On Harry C. Smith, see William

J. Simmons, Men of Mark: Eminent, Progressive and Rising (New

York, 1968), 194-198; Cleveland Gazette,

December 13, 20, 1941. On Albion W. Tourgee, see Otto H.

Olsen, Carpetbagger's Crusade: The

Life of Albion W. Tourgee (Baltimore. 1965). On the cooperation

between Smith and Tourgee, see ibid.,

310-313, 333.

44 OHIO

HISTORY

community responsibility and liability

for mob violence. The Harrison adminis-

tration, however, had proved itself

unwilling to make lynching a national issue.

Though Republicans had controlled both

houses of Congress during 1889-1893,

Harrison said and did little for most of

his presidency in response to the lynching

epidemic of the early 1890's. Indeed the

President waited until his last annual mes-

sage in December 1892, only three months

before a Democratic administration and

Congress were to take office, to

recommend passage of legislation to protect citizens

from lynching. The sole legislative

achievement on the subject during the Harrison

years was a federal law to protect

foreign nationals in the United States from mob

violence, prompted by the mob execution

of eleven Italian citizens at New Orleans

in 1890.26

Frustrated in attempts to win the

interest of the administration and unlikely to

find a sympathetic ear in Democratic

President-elect Cleveland, beholden to a sol-

idly Democratic South, Tourgee was

prompted by the Adams County lynching and

presumably by the presence of Smith in

the legislature to turn his efforts toward ob-

taining anti-lynching legislation in

Ohio. Shortly after the lynching, Tourgee ad-

dressed a public letter to Governor

William McKinley in which he outlined a plan

for a comprehensive anti-lynching law.

Pointing to the spread of violent crime in

America, not only lynching but also

homocide and armed robbery, he stated that

the nation was in a state of "near

anarchy" comparable only to Russia (then at-

tempting to confront revolutionary

radicalism under repressive, heavy-handed

Czarist rule). Tourgee also discussed the

fears of labor and farmer radicalism

which haunted contemporary political

conservatives. The year 1894 was after all

one of the worst years of a very severe

depression, the consequences of which were

manifesting themselves everywhere, much

to the horror of entrenched interests and

those of conservative temperament.

Agrarian radicalism in the South and West

had already given rise to the Populist

party, which now posed a threat to the bal-

ance of existing economic and political

forces in the nation. In the North, a large

number of bitterly discontended,

unemployed workers were organizing armies of

the jobless with the intention of

marching on the national capital. Pointing to the

participation of Adams County's

"best people" in the recent lynching, Tourgee, who

himself feared class as well as racial

violence, warned, "If the present financial con-

dition continues . . . we shall see

within a very brief time the same anarchistic spirit

displaying itself in the destruction of

property. The hungry and destitute will argue

that if the rich and respectable are not

punished for openly taking life they will be

equally exempt from punishment for

destroying the property which a large portion

of our people already believe has been

taken from them by legalized wrong."27

The law which Tourgee proposed was based

on the belief that because lynchings

"never occur except in a community whose citizens favor and approve

such out-

rage," the most efficient means to

check them was to make the entire community re-

sponsible before the law for mob

violence. This was to be accomplished, in his

words, by "touching the

pocket-nerve": establishing community financial responsi-

bility for lynching in the same manner

in which railroads were required to make fi-

nancial restitution to the legal

representatives of victims of railroad accidents in

which the operators were found

negligent.

26. Olsen, Carpetbagger's Crusade, 325;

Cleveland Gazette, June 4, 1892; Rayford W. Logan, The Be-

trayal of the Negro (New York, 1954), 85-86.

27. Tourgee's letter to the governor is

reprinted in the Cleveland Gazette, March 3, 1894.

Ohio Anti-Lynching Law, 1896 45

Specifically, Tourgee suggested that the

legal representatives of victims of lynch-

ing in Ohio be allowed to sue the county

in which violence occurred for $10,000. If

the victim of the mob was not killed but

seriously injured, he might sue for not less

than $1,000, and if not seriously hurt,

for no less than $200. The money was to be

raised by a general tax levy in the

offending county. To counteract the possibility

of local intimidation of those seeking

redress under the law in the county where the

crime was committed, suits for damages

might be instituted in any adjoining county.

To check the possibility of relatives or

victims compromising or agreeing to take less

than the full amount of the claim, the

proposal carried with it the penalty of mis-

demeanor for such a settlement. Finally,

Tourgee's proposal did not exempt mem-

bers of lynch mobs from prosecution on

criminal charges.28

The Tourgee plan was founded upon certain

problematic assumptions about hu-

man motivation, violence, and interclass

relations. He assumed that the principle

of community liability in touching the

"pocket nerve" of the community's higher

status persons would move them to become

the most effective opponents of lynch-

ing. Also, as heavier taxpayers, they

would be discouraged from participating in

lynch mobs and would be forced to use

their power and prestige to restrain mobs

and bolster the efforts of local law

enforcement agents. To the extent that persons

of high status were members of mobs, it

was possible that the law might cause them

circumspection, though the size of their

loss in a heavily populated area would be

minimal-especially given the fixed

penalty advocated. Another weakness of the

law was that it considered the

composition of lynch mobs to be socially constant,

when in fact each mob might well be

different, depending on the size of the commu-

nity, the nature of the crime, and the

social class of its victim, and doubtless many

other variables. The proposal also may

well have overestimated the influence "best

people" had on those beneath them

on the social scale and the extent to which the

former would deign to involve themselves

in checking the violent behavior of the

latter. But perhaps the most fundamental

problem with the law was its dependence

on a calculation of rational

self-interest to dissuade a violent mob profoundly en-

raged by the occurrence-or rumored

occurrence-of a brutal crime, especially when

that rage was heightened by racial

prejudice and definite notions of the "place" of

blacks in society. Ultimately, while

such a law might be helpful to some extent, the

effort to eradicate lynching required as

its first prerequisite the most determined and

unyielding law enforcement by local

officials, perhaps supplemented when neces-

sary by the presence of the state

militia.

Yet, the Tourgee proposal was innovative

and certainly more comprehensive than

any other piece of legislation against

lynching enacted up to that time. In fact by

1894 only two states in the entire

nation, Georgia and North Carolina, had any anti-

lynching legislation at all. Both states

had passed laws in 1893 in response to the

outbreak of lynching in the South. The

Georgia law simply penalized sheriffs

found negligent in the protection of

prisoners threatened by mob violence and al-

lowed law enforcement agents to deputize

local citizens for the purpose of obtaining

aid in the protection of jails and

persons in custody. No penalty defined by the law

was greater than a misdeameanor, no

doubt offering little incentive for the sheriff to

become involved in a bloody struggle

against a mob. The North Carolina law was

even weaker. It simply made counties in

which lynchings occurred liable for the

28. Ibid.

46

OHIO HISTORY

costs of the investigation and

prosecution of persons involved in a mob.29

The need for anti-lynching legislation

in Ohio was again highlighted during the

legislative session in the spring of

1894 by the lynching of a black man accused of

raping an eighty-year old woman at

Rushsylvania in rural Logan County. The

woman identified her assailant just

hours after the supposed crime, but shortly after

the lynching she was not as sure as she

had been. As usual, though a grand jury in-

vestigation of the affair was held, the

refusal to indict known mob members closed

the affair forever.30

But pressing as the need for legislative

action appeared, Ohio's black legislators

were not united on a single approach to

an anti-lynching bill. Though Smith had

declared his intention to offer a bill

embodying Tourgee's proposal, his Cleveland

political rival and personal enemy,

William Clifford, took the opportunity presented

by a delay in Smith's plan to introduce

his own bill on April 18. The Clifford bill,

no doubt at least in part motivated by a

desire to upstage Smith, was hastily drawn

and unworkable. It defined as a

participant in lynching every person present at the

scene of mob violence, providing

sentences of five to twenty years for each. Not

only therefore might the Clifford

proposal have sent whole towns to prison (not to

mention uninvolved bystanders), but also

it nullified the possibility of there being

any witnesses by making everyone a

defendant!31

Smith's more comprehensive and viable

plan was in accordance with a revised

Tourgee proposal which reduced the

amount paid to victims of lynching or their

representatives, and was introduced a

short time later. It was doubtful, however,

that the General Assembly would act on

either bill that session since it was the cus-

tom of the legislature at that time,

when hearing matters relating to the interest of

Ohio's blacks, to wait until the blacks

had resolved the differences among them-

selves before proceeding. Thus, the only

anti-lynching measure passed that session

was Representative Samuel Hill's

resolution condemning the lynching at Adams

County. An opportunity had been lost,

and, since the state legislature was to begin

meeting biennially rather than yearly

after the 1894 session, action was postponed

until 1896.32

Events between the end of the 1894

session and the next legislature caused many

to lament the delay. Particularly tragic

was the violence at Washington Court

House. Attempts in that town to lynch a

Negro recently convicted for raping a

white woman, led to clashes between mobs

and state militia units which had been

rushed to the scene by Governor

McKinley. When the mob attempted to seize the

prisoner, the militia fired. As a

result, five youths in the crowd were killed and

29. Code of the State of Georgia,

Adopted August ... 1910 (Atlanta, 1911), II, 74-75; Thomas Womack,

etal., Revisal of 1905 of North

Carolina (Raleigh, 1905), 363. During

Reconstruction, in a minority of

southern states, there had been anti-mob

violence legislation, but in only South Carolina and Alabama

had the principle of community liability

been established. An Alabama law passed in 1868 to counter

violence against Radical Republicans

came closest to the Tourgee proposal, providing for the widow or

next of kin of murdered victims of mob

violence to recover $5,000 from the county where the violence

occurred. The South Carolina law allowed

for payment in the case of survivors of persons killed for

their political opinions. It is possible

that Tourgee, who served as a Republican judge during Recon-

struction in North Carolina, had been

influenced by these earlier, ephemeral measures, which are men-

tioned by Lerone Bennett, Jr., Black

Power U.S.A.: The Human Side of Reconstruction, 1867-1877 (Balti-

more, 1969), 376.

30. Bellefontaine Weekly Examiner, April

19, May 17, June 7, 1894.

31. Cleveland Gazette, May 12,

1894.

32. Ohio State Journal (Columbus),

May 9, 1984; Cleveland Gazette, May 12, 19, 1894; Ohio, House

Journal, 1894, p. 1007, 1098.

Ohio Anti-Lynching Law, 1896

47

some twenty persons wounded. On the

heels of the nationally publicized Washing-

ton Court House riot came threats of

lynching at Newark and Hicksville, and sev-

eral weeks later at Springfield. More

violence occurred in 1895. At New Rich-

mond in August, a black man accused of

the murder of an aged banker, whom he

claimed had cheated him of a large sum

of money, was lynched. In October two

men were killed in clashes with

militiamen at Tiffin, to which the militia had been

called when a mob attempted to seize a

white prisoner who was being held for mur-

der of a popular local marshal.33

Such events no doubt helped to emphasize

the immediate need for anti-lynching

legislation when the newly elected,

overwhelmingly Republican state legislature

convened in January 1896. Harry C.

Smith, who would also obtain an important

revision of the state civil rights law

during the session, had been reelected promising

to pursue an anti-lynching bill.

Governor McKinley lent the prestige of a possible

presidential candidate to the cause in

his last annual message, making a strong plea

for anti-lynching legislation and

pointing to the tragic consequences of mob vio-

lence at Washington Court House and

Tiffin.

Smith introduced his anti-lynching bill

on January 20 and was optimistic regard-

ing passage. Allied with him were

several of the most prestigious newspapers in the

state, including the Ohio State

Journal (Columbus) and the Cleveland Plain Dealer.

Furthermore, unlike the 1894 session, he

enjoyed the full cooperation of his two

Afro-American colleagues in the House of

Representatives, William Stewart of

Youngstown and William Parham of

Cincinnati. Adding to Smith's optimism was

Tourgee's promise that he would appear

on February 5 before the house judiciary

committee.34

The bill, however, was soon in trouble.

Though the judiciary committee recom-

mended passage on February 20, a group

of house members of both parties led by

Representative Aquila Wiley, a Wayne

County Democrat, opposed not only the

principle of community liability but

indeed the very idea that anti-lynching legisla-

tion was needed in a northern state. In

forceful speeches Wiley called the bill a

"revolution of all laws and rules

of criminal jurisprudence." Assuming the guilt of

all victims of mob violence, Wiley

contended that the bill placed a premium on

crime by granting to the target of mob

retribution a large sum of money which, he

said, was in effect "a pension for

the worst criminals in the state." Wiley was also

something less than sensitive to

constitutional guarantees of a fair trial. Countering

Smith's claim that several southern

states were then discussing legislation modeled

after his bill, Wiley stated that such a

law was only needed in the South where

blacks were lynched for attempting to

exercise constitutional rights such as voting.

In the North, he stated, "Nobody is

lynched here except those who have been guilty

of so heinous crime that the indignation

of citizens arises in an uncontrollable

frenzy."35

The bill reached a vote on February 26

and was defeated. Though it received 50

votes, to the 34 cast against it, it

lacked a necessary constitutional majority of 57.

33. Cyclone and Fayette Republican (Washington

Court House), October 11, 18, 25, 1894; Batavia Cler-

mont Sun, August 28, 1895; Tiffin Seneca Advertiser, October

25, 29, November 1, 5, 1895; Cleveland Ga-

zette, October 20, 27, December 22, 1894, August 31, November

23, 1895.

34. Ohio State Journal (Columbus),

January 21, February 6, 1896; Cleveland Gazette, January 25,

1896; Harry C. Smith to Albion W.

Tourgee, January 27, 1896, item 8948, Tourgee Papers.

35. Dayton Daily Journal, February

28, 1896; Ohio State Journal (Columbus), February 27, 1896;

Smith to Tourgee, February 20, 1896,

item 9084, Tourgee Papers.

48 OHIO HISTORY

Voting against the bill were 12 of the

23 Democrats present and 22 of 89 Republi-

cans, while 28 members-most of them

Republicans-chose to absent themselves

from the floor. In general,

representatives from southern and central counties, where

almost all of the recent manifestations

of lynch law had occurred, failed to support

the bill. After several weeks of

intensive campaigning among house Republicans

the bill did pass on March 24 by a vote

of 61 to 22, but by only 4 votes more than a

constitutional majority. While a

relatively large number of southern Ohio Republi-

cans still continued to vote against the

bill or not at all, a change of 4 votes in the

Hamilton and Montgomery County

Republican delegations provided the margin of

victory. With a minor amendment, which

the house later approved, the bill then

passed the senate on April 8 by an

almost unanimous vote of 22 to 2. In its final

form, the Smith bill embodied all the

major provisions of the Tourgee revised pro-

posal with the compensation for the

relatives of those killed by mob violence cut in

half.36

The law soon became a model for

anti-lynching legislation in other states. South

Carolina in 1896 and Kentucky in 1897

passed laws directly patterned after the

Ohio law, while Illinois, Minnesota,

Nebraska, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, West Vir-

ginia, and Wisconsin all approved

legislation after 1900 embodying the major provi-

sions of the law. When the N.A.A.C.P.

carried on a campaign for anti-lynching leg-

islation in Pennsylvania during

1912-1913, the Ohio law served as a model for its

efforts.37

Praised as it was elsewhere, the Smith

Law had to weather several serious chal-

lenges in the next few years, both in

and out of the legislature. Unfortunately, in

spite of the law, it was not long before

another lynching occurred in the state. At Ur-

bana in early June 1897 a young black

was brutally mobbed and lynched after

being charged with the rape of a wealthy

widow. Evidence reported in Harry

Smith's Cleveland Gazette in the

weeks following the lynching suggested not only

that there had been glaring cowardice

and remarkably poor judgment displayed by

local officials in guarding their black

prisoner and in their unsuccessful attempts to

quell the mob gathered outside the

Urbana jail, but also that very probably there

had been neither rape nor assault of any

type. As usual, however, neither local in-

quiries nor grand jury hearings nor

state-initiated investigations yielded punish-

ments for the mob and its supporters.38

The Urbana affair helped to provide an

excellent court test of the new law.

Shortly after the lynching, the

relatives of the victim instituted a suit for maximum

damages against Champaign County. At the

same time, a suit under the law was

pending in the Common Pleas Court of

Cuyahoga County, filed by three whites

36. Cleveland Gazette, February

29, March 7, 28, April 11, 1896; Ohio, House Journal, 1896, pp.

313-314, 320, 699-700; Ohio, Senate

Journal, 1896, pp. 602-603: Smith to Tourgee, April 8, 1896, item

9084, Tourgee Papers; Laws of Ohio,

1896, pp. 136-138.

37. James H. Chadbourn, Lynching and

the Law (Chapel Hill, 1933), 149-213; J. E. Cutler, "Proposed

Remedies for Lynching," 194-212;

Edward Pell, "The Prevention of Lynching Epidemics," Review of Re-

views, XVII (March 1898), 321-325; Charles Flint Kellogg, NAACP,

A History of the National Associ-

ation for the Advancement of Colored

People (Baltimore, 1967), Vol I,

1909-1920, p. 214. Yet the Smith

Law has been neglected in the historical

literature on lynching. White's Rope and Faggott, Shay's Judge

Lynch, His First Hundred Years, and Chadborn's Lynching and the Law either fail

to make mention of

the law or simply list it along with

other state anti-lynching laws without discussing its influential and in-

novational character.

38. Urbana Citizen and Gazette, June

7, 1897; Urbana Champaign Democrat, June 3, 10, 1897; Cleve-

land Gazette, July 10, 17, 24,

August 7, 14, 21, 1897.

Ohio Anti-Lynching Law, 1896 49

who had been mobbed during labor

violence at Cleveland in 1896. In late July,

only three weeks after the Urbana

lynching, a Cuyahoga County judge rendered the

opinion that the Smith Law was

unconstitutional because it levied a tax for private

purposes and established fixed

penalties. In the Urbana case, a Champaign County

Common Pleas Court judge ruled the law

unconstitutional only to be overruled by

the county Circuit Court in October

1898. Both the Cleveland and Urbana cases

reached the State Supreme Court in 1900

on appeal, and the court sustained the

law's constitutionality. While the issue

was being fought in the courts, efforts to re-

peal the law in the General Assembly in

1898 proved unsuccessful. During the

1898 session, the law and the general

cause of anti-lynching were actually strength-

ened when Representative William Steward

of Youngstown, reelected for a second

term, obtained the removal of a section

of the Smith Law which it was feared would

be offensive to the courts. Furthermore,

a white legislator, Representative Chase

Stewart, successfully sponsored a bill

providing that persons breaking into jails and

attacking law officers in order to seize

prisoners for the purpose of lynching were to

be sentenced to terms of between one

year and ten years in the penitentiary.39

By the first decade of the twentieth

century Ohio, with the approval of her highest

court, had created a legal bulwark

necessary to protect a civilized community

against lynching. There is no way to

determine how many incipient mobs were dis-

suaded from forming by a knowledge of

the consequences for their communities

which the law now held, but the effects

of this legal bulwark appeared to be mixed

during the first decade of the new

century. While the number of lynchings declined

from five during the 1890's to two

during the first decade of the twentieth century,

the scale of violence in those attempts

at lynching and those anti-black riots which

did occur actually grew.

At Akron in August 1900 a mob led by,

among others, a prominent member of

the city council, became so enraged over

the rumor that a black man had raped a

white six year old that it fought for

ten hours with police for custody of the accused,

who had been spirited away to Cleveland

for safekeeping by an alert sheriff. Frus-

trated in its attempts at lynching and

spurred on by a newspaper which printed sen-

sational stories about the incident in

red ink, the mob ultimately dynamited the

city's government building-courthouse

complex and fired several nearby stores.40 It

was at Springfield, however, that the

most serious incidents of the early years of the

century occurred. There in 1904,

following the murder of a policeman by a Ken-

tucky Negro recently settled in the

city, a mob broke into the city jail, seized the

prisoner, and lynched him in a downtown

square. The lynching was followed by a

riot in which a white law and order mob

sought to uproot from the city a slum like

area of interracial vice and crime. Many

citizens of Springfield blamed the saloons,

brothels, and gambling dens found there

for the contempt for the law and its offi-

cers that was said to be so pronounced

in the city at the time among both blacks and

whites. The mob succeeded only in

burning down the tenements in which many im-

proverished blacks lived. The official

response to its violent deeds was predictably

ineffective and did little to strengthen

the forces of law and justice in the city. Only

a minority of those charged before a

grand jury were indicted, and little in the way

of punishment was meted out to those

forced to stand trial. Indeed, the only de-

39. Cleveland Leader, March 12,

1897; Cleveland Gazette, February 5, April 23, October 22, 1898,

March 25, May 6, 13, 1899, April 21,

1900.

40. Akron Democrat, August 24,

25, 1900.

50 OHIO

HISTORY

fendant actually charged with complicity

in homocide for his participation in the

lynch mob was acquitted.41

Springfield remained ripe for another

round of violence, and it came almost two

years to the day after the first riot.

The immediate reasons were attacks upon sev-

eral whites by blacks, whom the whites

were said to have taunted with racial slurs,

and by the shooting of a white railroad

worker by a black man. All the blacks in-

volved were quickly apprehended and sent

to the Dayton workhouse in order that

the scenes of 1904 might not be

repeated. But an enraged mob again attacked the

slums where vice and crime festered,

burning down a number of saloons and tene-

ments, dispossessing more of the

hapless, innocent black poor who were forced to

live amidst squalor and vice. Though few

mob members were jailed, the official re-

sponse was not without some merit: an

effort was made to regulate saloons and

close vice operations, and a civic

league of prominent white citizens was formed to

help combat vice and crime.42 The

rest of the decade in Ohio was quiet as far as ra-

cial violence was concerned, though the

lynching of a white man at Newark in 1910

at the hands of a white mob demonstrated

that the spirit of bloodlust which sus-

tained lynching was still capable of

inciting riot.43

While Ohio had actually witnessed relatively

few lynchings during the 1890-1910

period, the pattern of violence within

the state was broadly similar to that in the na-

tion at large. Following the peak of

lynching in the early 1890's, the incidence of

lynching began to decline after the turn

of the century. Never again, according to

available data, did the extent of

lynching ever reach its earlier very high levels. Ex-

planations of the peaks and ebbs in the

appearance of lynch mobs await a general

historical treatment of racial violence

in the United States. Perhaps as blacks be-

came increasingly mired in second class

citizenship in the first decades of the

twentieth century, trapped by poverty,

disfranchisement, and segregation in un-

questionable and unambiguous

socioeconomic and political inferiority, in the South

especially and to some extent in Ohio

and the North, the need to reinforce their

status through violent intimidation

declined. Perhaps law enforcement agents be-

came more conscious of their duty to

resist lawless mobs bent on lynching. What-

ever the explanation, there is certainly

a great need for historians to attempt to

come to terms with this bloody and too

easily neglected chapter of our violent na-

tional past.

41. Baker, Following the Color Line, 201-208;

Springfield Press-Republic, March 8, 9, 10, 11, 1904;

Cleveland Gazette, March 12,

April 2, 9, May 7, 1904.

42. Baker, Following the Color Line, 210;

Springfield Daily News, February 26, 28, March 1, 2. 3. 1906;

Cleveland Gazette, March 3, 10,

17, 31, April 7, 14. 1906.

43. N.A.A.C.P., Thirty Years of

Lynching, 85.