Ohio History Journal

OHIO

Archaeological and Historical

PUBLICATIONS.

MONUMENTS TO HISTORICAL INDIAN CHIEFS.

BY EDWARD LIVINGSTON TAYLOR.

[This is the second contribution of Mr.

Taylor upon the subject. The

first will be found on page 1, Volume

IX, O. A. and H. Society Pub-

lication.-E. 0. R.]

In the July number of the Archaeological

and Historical

Quarterly for the year 1900 I gave some

account of the history

of the monuments that have been erected

by white men to com-

memorate the memories of noted men of

the Indian or Red

Race. At that time I had knowledge of

but four of such mon-

uments. First, in order of time, was

that erected to Chief Keokuk,

at Keokuk, Iowa. The next was that of

Leatherlips, near Co-

lumbus, Ohio. The third, was that of Red

Jacket, at Buffalo,

New York; and the fourth, was that of

Chief Cornstalk, at Point

Pleasant, West Virginia.

Soon after that article was published, I

learned of three

monuments which had been omitted and

more recently of one

that is proposed and almost surely will

be erected. The omitted

ones were that of Chiefs Uncas and

Miantonomoh at and near

the town of Norwich, State of

Connecticut, and that of Chief

Sealth (Seattle) at Fort Madison on

Puget Sound, near the

town of Seattle, in the State of

Washington.

The proposed monument is that for

Leopold and Simon Po-

Kagon, father and son, who were the last

and best known chiefs

of the Pottawattamie tribe. Simon died

at Allegan, in the state

2 Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

of Michigan, January 28th, 1899, and was

buried with great

honor in Graceland cemetery, Chicago,

Illinois. These were all

among the remarkable men of their race

and have been given a

prominent place in our history, as well

as monuments erected by

white men to mark their last resting

places, as we shall more

particularly describe.

CHIEFS UNCAS AND MIANTONOMOH.

Uncas was the most noted chief of the

Mohegan tribe and

Miantonomoh of the Narragansetts, of

which the early English

settlers in the region of Connecticut

and Rhode Island had know-

ledge. The Narragansetts occupied the

region of what is now

Rhode Island, and the Mohegans were to

the westward of them,

in what is now the state of Connecticut.

The Mohegans were a

branch of the Pequot tribe. To the west

of the Mohegans

were the Niantics. All of these tribes

were of the Algonquin

linguistic family, and spoke

substantially the same language.

Still further to the westward of these

Algonquins in the state

of New York were the Five Nations of the

Iroquois, who were

of an entirely different linguistic

family. Although the Mohe-

gans, the Narragansetts and the Niantics

were of the same lin-

guistic family, they were often at war

with each other and their

wars were of the most cruel and

relentless character. They

were really wars of extermination and no

quarter was usually

given to fallen foes or expected by

them.

When the white settlers came to that

region they found

among the Indian tribes a most disturbed

condition. The most

bitter hatred and relentless wars

obtained between them and this

caused the ablest and best warriors to

be selected as their re-

spective chiefs. The traditions which

the white people gathered

when they first ventured into that

region indicated that wars

and strifes had long obtained between

the neighboring tribes and

the hatreds and animosities which such

wars necessarily engen-

dered among savage tribes were in bitter

and relentless force.

Early in the fifteenth century Lord Say

and Lord Brook,

with their associates, became patentees

of much of the territory

which is now embraced in the State of

Connecticut. They pur-

Monuments to Historical Indian

Chiefs. 3

chased such rights as an English patent

of those days could

confer from Robert, Earl of Warwick, in

1632. Their rights,

whatever they were, covered the land

westward from "the Nar-

ragansett river one hundred and twenty

miles in latitude and

breadth to the South Sea." The Earl

of Warwick was presi-

dent of the Council of Plymouth

incorporated by King James

I, for the settlement of New England

"and authorized to dis-

pense grants and patents to

others." In so far as the English

government could confer title or patent

to Lord Say and Lord

Brook and their associates, their patent

was valid. In pur-

suance of this grant, John Winthrop, the

younger, acting for

the patentees, in 1635 built a fort at

the mouth of the Connecticut

River and called it Fort Saybrook. The

name is a combination

of the names of these two principal

patentees-Say-Brook. The

place holds its name to this day.

Soon thereafter what is called in

history the "Pequot War"

broke out and the infant settlement of

Saybrook was in danger

of being destroyed. In 1636 and 1637 the

Fort was virtually

besieged by the Pequot Indians, but was

bravely and successfully

defended by Lieutenant Lion Gardner, a

trusted and faithful

agent of Winthrop. This settlement

gradually grew stronger by

accession from the mother country and by

the natural increase

of births until it became a center of

power and a new element

of strength, which forced recognition by

the native tribes in the

surrounding region. The English about or

little before that

time had obtained a foothold to the east

of Saybrook in the

region of Narragansett Bay in the

territory of Rhode Island,

which region was the home of the

powerful Narragansett tribe.

Both Uncas and Miantonomoh soon came to

recognize this

new element of power and influence and

to appreciate the fact

that friendly relations with the new

comers might be to their

advantage and both with some success

established such rela-

tions with their white neighbors. The

English honestly desired

and endeavored to promote peace and

harmony among the war-

ring and hostile tribes and did so far

succeed that in 1638 a

treaty was made at Hartford by which it

was stipulated "that

the hostile Sachems should not make war

on each other without

first making an appeal to the

English."

4 Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

This treaty agreement was not however

long observed by

the Narragansetts and in 1643, a fierce

war broke out between

that tribe and the Mohegans. The

Narragansetts disregarding

the agreement advanced against the

Mohegans with superior

numbers with the purpose and prospect of

overwhelming Uncas

and his tribe. Uncas was not prepared

for this unexpected in-

vasion, but hurriedly gathered his

warriors and prepared as

best he could to resist the invasion.

Miantonomoh, the inveterate

enemy of Uncas, was in command as chief

of the Narragan-

setts. He had under his command near a

thousand warriors

while Uncas could assemble not more than

about four hun-

dred warriors to oppose them, and appreciating

the disadvan-

tage under which he and his warriors

labored, he sought a parley

with the chief of the Narragansetts and

proposed that Mianto-

nomoh and himself should engage in

single combat to decide

the fortunes of battle between the

tribes. The proposition was de-

clined and at a signal from Uncas, which

had been pre-arranged,

his warriors being prepared rushed upon

the Narragansetts, who

were taken by surprise and routed, and

many of them were

slain and their chief was taken

prisoner. Miantonomoh was

kindly treated by Uncas, who

subsequently surrendered him

to the English, by whose decision he

consented to be

governed as to what disposition should

be made of him.

The matter was referred to the Commissioners

of the United

Colonies, at Boston, who in doubt as to

what should be done

in the premises, referred the case to

the "Ecclesiastical Counsel-

lors," at Hartford. The five

Ecclesiastical Counsellors consulted,

gave their voice in favor of his

execution, and it was ordered

that Uncas should carry out the

sentence, and a delegation

of white men was appointed to see that

the sentence was carried

out. So Miantonomoh was taken back to

the spot where he

had been captured and was there

executed. The fatal blow

which ended his life was struck with a

hatchet in the hands of

a brother of Uncas. He was buried on the

spot of his capture

and execution, which is about a mile

east from the City of Nor-

wich, to which place members of his

tribe made visits for many

years, and at each visit added to a pile

of stone over his grave,

until a very considerable monument was

in this way raised to

|

Monuments to Historical Indian Chiefs. 5

him by his own tribe. These stones, however, so mournfully and reverently gathered and placed over the remains of their beloved chief, were subsequently irreverently removed by a white land holder and converted to the baser use of making a foun- dation for a barn. The taking off of Miantonomoh in this barbarous manner must always, as stated by the historian Caul- kins, "stand as one of the most flagrant acts of injustice and ingratitude recorded against the English settlers." The reason given by the Ecclesiastical Counsellors for vot- ing for the death of Miantonomoh, was that he had made war upon the Mohegans and invaded their country without first ap- pealing to the English, according to the agreement and they feared if he was spared he might be the cause of trouble in |

|

|

|

the future. But this act of cruelty only tended to greatly inflame the old hatred of the Narragansetts and they determined to avenge the murder of their beloved chief. Conflicts of every kind soon followed until in the spring of 1645, when the Narra- gansetts again invaded the Mohegan's country in strong force under the leadership of Pessacus, the brother of the murdered chief. After creating havoc and devastation they forced Uncas to take refuge in a fort on the bank of the Pequot (now the Thames) River, which the English had helped to construct. This fort was about eight or ten miles up from the mouth of that stream. Uncas and his people were besieged there until on the very verge of starvation, but in this extremity he managed to get word to the English at Fort Saybrook, which was at the mouth of the Connecticut River, some twenty-five or more miles to the westward. |

6 Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

Upon learning of the desperate situation

of Uncas and

his people and knowing that surrender

meant death to all within

the fort, it was determined at all

hazards to attempt to relieve

them; so a canoe was loaded with

provisions and three brave

and hardy young men (Thomas Leffingwell,

Thomas Tracy and

Thomas Minor) volunteered to hazard the

undertaking of reach-

ing the fort with these provisions. They

followed along the

north shore of Long Island Sound some

twenty or more miles

eastward, until they reached the mouth

of the Pequot River

into whose waters they turned their

canoe and under cover of a

dark night they succeeded in reaching

the fort and Uncas and

his people were saved from the

annihilation which awaited them

at the hands of their inveterate and

exasperated foes.

Uncas and his tribe ever afterwards

remembered with grati-

tude this timely deliverance from the

dreadful fate which other-

wise would have befallen them. They

remained friendly to the

white settlers and in 1659 sold and

deeded to the "Town and

Inhabitants of Norwich" nine miles

square of land, near the

center of which tract the City of

Norwich now stands. That

was the beginning of the occupancy and

civilization of that im-

mediate part of Connecticut, which in

the two hundred and fifty

years which have since elapsed, has

developed great and bene-

ficial results. It is within this tract

of land that Uncas and Mian-

tonomoh lie buried and at no great

distance from each other.

The date of the execution of Miantonomoh

is stated, by Gov-

ernor Winthrop, as September 28th, 1643,

and this may be

assumed to be correct and is the date

carved on his monument.

The Colonial Commissioners met in Boston

September 17th

of that year when they affirmed the vote

of the Ecclesiastical

Counsellors, which sealed the fate of

Miantonomoh. Their pro-

ceedings were kept secret until the

members of Hartford and

New Haven returned home. This precaution

was necessary,

as they would have to pass through or

near the territory of

the Narragansetts, who certainly would

have killed them if they

had fallen into their hands. A knowledge

of their action was

soon known to the Narragansetts and on

October 12th, Pessacus

sent a message to the commissioners at

Boston of his intention

to avenge the death of his brother, and

in the spring of 1645,

Monuments to Historical Indian

Chiefs. 7

at the head of the Narragansetts, he

invaded the country of the

Mohegans, as we have before seen.

In the intervening time they had often

in various ways and

by various strategies sought the life of

Uncas, but his caution

and craftiness was such that he was able

to defeat all their

efforts to that end. Miantonomoh was

greatly beloved by his

tribe and also by the white people in

his territory with whom

he came in contact, and it is recorded

of him that "he had shown

many acts of kindness towards the

whites; in all his inter-

course with them he evinced a noble and

magnanimous spirit;

he had been the uniform friend and

assistant of the first white

settlers in Rhode Island; and only seven

years before his death

had received into the bosom of his

country Major Mason and

his little band of soldiers from

Hartford and greatly assisted

them in their conquest of the

Pequots."

In view of these qualities and his

services to the white race,

it is difficult to understand why these

Ecclesiastical Counsellors

voted for his death; but they must be

judged by the hard and

cruel times in which they lived, and the

stern religion by which

their acts were guided.

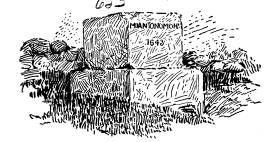

We have before related that the pile of

loose stone which

had been accumulated over the grave of

Miantonomoh by the

people of his tribe, was removed by a

white land owner, who

converted them to his own use. Just when

this was done is

not now definitely known, but it was

long after the execution

and burial.

However, it is gratifying to know that

on July 4th, 1841, this

sacrilege was atoned for by more

enlightened and less selfish

white people residing in Norwich and

vicinity, who placed over

his grave a solid block of granite about

eight feet long and five

feet in height and the same in thickness

with the single word

cut in large and deep letters and

figures thereon:

MIANTONOMOH.

1643.

On that occasion a Mr. Gillman of

Norwich delivered an

address and the formal laying of the

stone was performed

by Thomas Sterry Hunt, a young man, who

afterwards became

8 Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

one of the most eminent of American

chemists. This was, so

far as we have knowledge, the first

monument actually erected

by white men over the grave of a noted

representative of the

Red Race; and nothing could better

illustrate our advance in

civilization than this act of rescuing

the grave of this noted

chief from neglect and oblivion, who two

hundred years before

had been condemned and executed by the

decree of representatives

of the early English settlers for no

crime or hostile act against

themselves and who was in fact their

friend.

UNCAS.

Although the Miantonomoh monument was

the first actually

erected, it was not the first to be

projected. The people of Nor-

wich had long contemplated a monument to

Uncas, but the pro-

ject did not take active form until the

summer of 1833, when

General Jackson, then President of the

United States, visited

Norwich and other New England cities and

his visit to Norwich

was made the occasion of awakening an

active interest in the

project of erecting a monument for their

"Old Friend," as they

expressed it - the Mohegan Sachem,

Uncas.

The President was accompanied on that

visit by Vice Presi-

dent Van Buren, Governor Edwards of

Connecticut, Major

Donelson, General Lewis Cass, Secretary

of War; Mr. Wood-

bury, Secretary of the Navy; and Mr.

Poinsett, Secretary of

State. This was a very notable party and

their visit naturally

aroused such interest with the citizens

of Norwich and the sur-

rounding country, that there was

gathered a great assembly

of men, women and children, bands and

military and other or-

ganizations. A few Indians were present.

Altogether the visit-

ing party received a great ovation.

Hon. N. L. Shipman delivered an address

narrating the

history of the Uncas family and the then

existing condition of

the Mohegans. President Jackson then

formally "moved the

foundation stone to its place." It

has been described by the his-

torian, Frances Manwaring Caulkins, as

"an interesting, sug-

gestive ceremony; a token of respect

from the modern warrior

to the ancient-from the emigrant race to

the aborigines."

Monuments to Historical Indian

Chiefs. 9

General Cass then delivered an address

in which he observed

that "the earth afforded but few

more striking spectacles than

that of one hero doing homage at the

tomb of another." At the

close of this address the children sang

a hymn and the day's

exercises were closed.

But the worthy project languished most

singularly and it

was seven years before the work so

auspiciously begun received

another impetus. The delay was caused by

want of funds, which

with all their enthusiasm they forgot to

provide for; nor did

they at that time have any plan or

design prepared. It was not

until October 15, 1840, that the next

considerable effort was

made to procure means with which to

carry out the undertaking.

On that date there was to be held at

Norwich a great political

meeting in honor of General Harrison and

John Tyler, then can-

didates respectively for President and

Vice President of the

United States; and for the purpose of

raising funds with which

to complete the monument, the ladies of

Norwich arranged for

a refreshment fair. They made most ample

provision for re-

freshments and themselves served the

customers at the tables

and thus raised the money with which to

complete the monument.

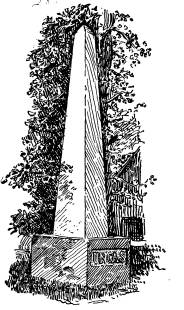

On the 4th day of July, 1842, just one

year after the Mian-

tonomoh monument had been placed over

his grave, the Uncas

monument was erected. It was made a

great occasion. The

Hon. William L. Stone, of New York,

delivered an historic ad-

dress on the life and times of Uncas,

and the monument was

then placed in position. It consisted of

a granite obelisk or shaft

about twenty feet in height supported by

a large granite block,

on which is cut in large letters, the

simple name:

All about the grave of Uncas repose the

ashes of many

chiefs and members of his tribe. The

place had before been

used and has since been used by the

Indians as a burying place,

but little or no evidence now remains to

distinguish their re-

spective graves. The death of Uncas is

fixed as having occurred

in the fall of 1683. His death was the

result of advanced age.

Some harsh reflections have been left by

some of the early

Puritan ministers upon the character of

Uncas. They may all

|

10 Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

be summed up in the notes of Rev. Mr. Fitch, of the date of 1678. He then said of him that he was "the greate opponent of any means of soul's good and concernment to his people and abounding more and more in dancings and all manner of heath- enish impieties since the warrs and vilifying what hath been done by the English and attributing the victory to their Indean helpes." |

|

|

|

It will be observed that dancing and claiming for the Mo- hegans a part of the honors for the victories over the Pequots are the only specific charges. As for dancing, it was an ancient custom among the Indians and still obtains among them and is not now considered even by the most advanced society of our modern civilization as a very "impious" or "heathenish" sin; and as for the claim of Uncas that his tribe was entitled to a part of the honors for the "victories" over the Pequots, it was certainly well founded, as Major John Mason, who commanded the English soldiers against the Pequots while Uncas led the Mohegans, has recorded of him that "he was a great friend and did great service." |

Monuments to Historical Indian Chiefs. 11

It is easy now to understand what the

Rev. Mr. Fitch failed

to appreciate, that his stern and rigid

religion and manner of

life was not suited to the Indian mind

and habit of life and

thought. Mr. Fitch was certainly as much

at fault in not un-

derstanding the Indian mind and

character as Uncas was in not

understanding Mr. Fitch's harsh and

arbitrary religion.

It may be accepted as a just estimate of

both Uncas and

Miantonomoh that they were neither all

good nor all bad; that

they were superior men of their race;

that they were brave and

had many virtues and good qualities of

character; and that they

performed the duties of life which

devolved upon them as best

they could according to their

understandings and the conditions

under which they lived. Both rendered

valuable aid and assist-

ance to the white settlers and the

monuments which the white

race has placed over their graves are

most fitting tributes to their

memories.

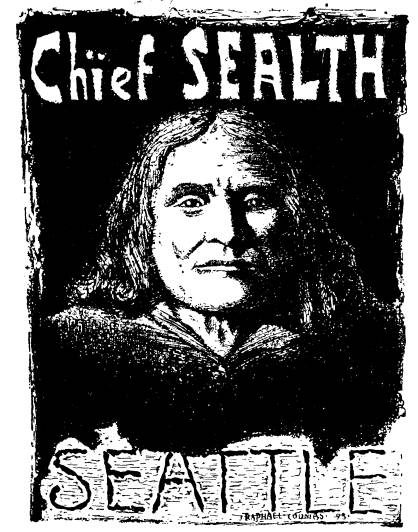

CHIEF SEATTLE (SEALTH).

The next monument we have to mention is

that of Chief

Seattle, as named by the whites, or

Sealth, as called by the In-

dians. This monument is at Fort Madison

on the Puget Sound

in the State of Washington, about

fifteen miles north from the

city of Seattle, which important city

bears the name of this

noted chief.

The waters of Puget Sound were visited

by the Spaniards

in 1774. A few years later they were

visited by Captain Cook,

the celebrated English navigator, and he

was followed during the

next few years by several other

navigators under English direc-

tions, and these were soon followed by

the American ship "Co-

lumbia," in command of Captain

Kendrick, of Boston; and he

was followed by other American

navigators. The Columbia

River received its name from the ship

"Columbia," but it was

given to it by Captain Gray, who was in

command of that vessel

on its second voyage to those waters.

The expedition of Lewis and Clark, under

commission from

Thomas Jefferson, then President of the

United States, which

started from St. Louis in March, 1803,

reached the mouth of

the Columbia River on November 15, 1804. This was the

first

overland expedition which ever crossed

the continent. It was

|

12 Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

followed in 1810 by the Astor expedition, which sailed from New York in the ship "Tonquin," which reached the mouth of the |

|

|

|

Columbia River in March, 1811. The overland expedition of Mr. Astor, which started from the city of Montreal in August, |

Monuments to Historical Indian

Chiefs. 13

1810, reached the mouth of the Columbia

River February 15,

1812,

the history of both of which has been

graphically told by

Washington Irving in his narrative

"Astoria." Many other ex-

peditions followed, but it was not until

1845 that any American

citizen made settlement north of the

Columbia River. In August

of that year Colonel M. T. Simmons,

George Wauch and seven

others made the first settlement at or

near Budd's Inlet on Puget

Sound.

In 1849 the lumber trade was first

opened on the shores of

Puget Sound by a single vessel from San

Francisco (the brig

"Orbit"), which obtained a

load of piles at Budd's Inlet. From

that time on the settlements along the

shores and inlet of Puget

Sound rapidly and steadily increased.

The lumber and fur trades

had much to do with inducing these early

settlements.

The early settlers came in contact with

Chief Seattle, who

is described by Samuel F. Coombs, who

knew him intimately,

as "the greatest Indian character

of the country." He was, as

Mr. Coombs says, "a statesman and a

warrior." It was as a

statesman that he ruled his people for

the long period of more

than half a century and always exerted

over them a potent in-

fluence for good.

Mr. Coombs first saw this chief in 1860

at a council of

chiefs at the then village of Seattle.

He was then about seventy

years of age, and was, as Mr. Coombs

describes, "of calm and

dignified manners." The council

over which he was presiding

was composed of all the principal chiefs

of the various tribes

over which he had long ruled, and he

received the greatest rev-

erence and respect from all of them.

In the early part of the century and

perhaps much farther

back wars and conflicts of every kind

obtained between the Moun-

tain Indians from regions about the

headwaters of the Green

and White Rivers, and the Salt Water

tribes, living along the

shores of Puget Sound. The Mountain

tribes were always the

aggressors, and being superior in

numbers and ferocity, the Salt

Water tribes were usually vanquished and

many of them killed

and others captured and carried away to

the mountain regions

and made slaves by their captors.

14 Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

In the early years of the last century

the Salt Water tribes

learned of another war expedition coming

against them from the

mountain country and a council was

called for the purpose of

devising means and plans for resistance.

The plan of Seattle was

adopted, although he had not much more

than arrived at man-

hood. He was put at the head of the

warriors of the Salt Water

tribes and entrusted with the execution

of his plans for resistance.

He conducted his warriors up the White

River, by which they

had learned their enemies were

descending in canoes, to a point

where there is a sharp bend in the

stream and where the water

was very swift. He obstructed the river

below the bend so that

the descending canoes could not observe

these obstructions until

they were near upon them and the strong

current at that point

would prevent them from speedily turning

back. He then am-

bushed his warriors on each side of the

stream, armed with bows

and arrows and other instruments of

Indian warfare and awaited

the coming of the enemy. The advance

guard of the entire force

consisted of five canoes, carrying about

one hundred picked war-

riors. The three canoes most advanced

were caught and swamped

as they swept around the bend on the

swift water, and their

occupants were either killed or drowned.

Two canoes in the

rear got the alarm and retreated up the

river and escaped. The

resistance was so unexpected and

determined and the disaster so

great that the Mountain warriors

abandoned the expedition and

retreated to their own country.

There was great rejoicing among the Salt

Water tribes on

the marked victory over their old

enemies and a great council of

the tribes was called and Seattle was

made chief of them all.

The old chiefs became sub-chiefs under

him. Three of the Lake

tribes, which were numbered with those

of the Salt Water tribes,

at first refused to join in the

consolidation and Seattle made a

visit to each of them well prepared to

subdue them if necessary;

but he managed to win them by persuasion

and without force

and united them firmly with the other

tribes and from that time

until his death (in 1866) he was the

acknowledged head and chief

Sachem of all the tribes living on or

near Puget Sound and they

were never afterwards seriously troubled

by their old enemies

of the mountains.

Monuments to Historical Indian

Chiefs. 15

Seattle welcomed the white settlers to

the Puget Sound and

was always friendly to them and in turn

commanded their respect

and confidence. He was a great

peacemaker among his people

and discouraged in every way vice and

immorality among them.

Seattle died at what has long been known

as the "Old-Man-

House" near Fort Madison, June 7,

1866. He was about eighty

years of age at the time of his death.

Mr. Samuel F. Coombs,

who was a friend of Seattle, gives the

following account of his

death and funeral:

"After a long illness, during which

the old chief was fre-

quently visited by natives and early

white settlers from all over

the sound, he died at the Old-Man-House.

His funeral was at-

tended by several hundred white people

and by more of his own

people. A. G. Meigs, proprietor of the

Fort Madison Mill, shut

down his mill and on his steamer took

all the employes and others

over to the funeral. A great many also

went over from Seattle.

As the old Chief was a Catholic he was

buried with the ceremonies

of that church, mingled with which were

customs peculiar to

the Indians. The ceremonies were

imposing and impressive and

the chanting of the litanies by the

Indian singers was very beau-

tiful."

Subsequently in 1890 his friends among the white pioneers

erected a monument to perpetuate his

memory. It is of Italian

marble, seven feet high and consists of

a substantial base and

pedestal surmounted by a cross, bearing

the letters "I. H. S,"

below which appears:

(SEATTLE)

Chief of the

Squamish and Allied

Tribes.

Died June 7, 1866.

On the base in large letters is engraved

the Indian name;

SEALTH.

|

16 Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications. On one side of the monument is the following inscription:

SEATTLE, Chief of the Squamish and Allied Tribes, Died June 7th, 1866, The firm Friend of the Whites, and for Him the City of Seattle was named by its Founders. |

|

|

|

On another side are the words: Baptismal name Moah Sealth, age probably 80 years. This monument of marble may in time disintegrate and dis- appear and the exact spot of the grave of Seattle become un- marked and unknown, but there has within the last half century arisen on the shores of Puget Sound, and in the center of the region in which he was born and where he so long lived and wisely and justly ruled over his people, the splendid city of |

Monuments to Historical Indian

Chiefs. 17

Seattle, which bears his name and will

perpetuate and keep alive

the story of his deeds and virtues

during many future generations.

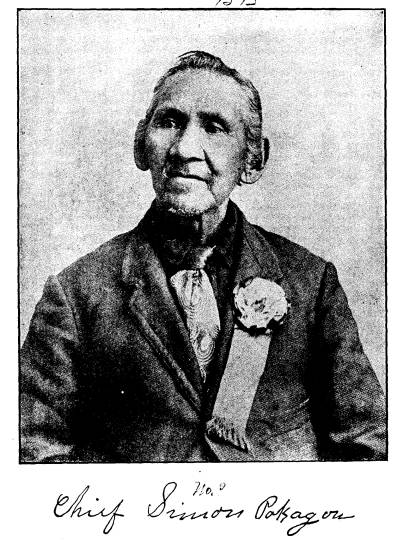

CHIEFS LEOPOLD AND SIMON POKAGON.

We have now in this and a former article

noticed all the

monuments of which we have knowledge,

which have to this

time been erected by white men to

commemorate the memories

of celebrated men of the Indian race.

That there may be others

is quite possible, but if so they have

escaped our research. We

have, however, yet to mention two of the

most remarkable men

that the red race has produced, namely:

Leopold Pokagon and

Simon Pokagon, his son, to whose memory

a monument is soon

to be erected in Jackson Park, Chicago.

Jackson Park embraces

the ground upon which the great

Columbian Exposition was

held in 1893, and has now been restored

to its original park con-

ditions of marvelous beauty.

These were successive chiefs and Sachems

of the once pow-

erful Pottawattamie tribe, which long

occupied the region around

the southern and eastern shores of Lake

Michigan in the center

of which now stands the great city of

Chicago.

Leopold Pokagon is described as a man of

excellent char-

acter and habits, a good warrior and

hunter, and as being pos-

sessed of considerable business

capacity. He was well known to

the early white settlers in the region

about Lake Michigan, and

his people were noted as being the most

advanced in civilization

of any of the neighboring tribes. He

ruled over his people for

a period of forty-three years. In 1833,

he sold for his tribe

to the United States one million acres

of land at three cents per

acre, and on the land so conveyed has

since been built the city

of Chicago. The purchase also included

what is now Jackson

Park, where the wonderful "White

City" stood in 1893, and where

a splendid monument will soon be erected

to the memory of him-

self and his son, Simon, and other

Pottawattamie chiefs.

On the great "Chicago Day" at

the Columbian Fair in Oc-

tober, 1893, where 750,000 people were

assembled, Simon Pa-

kagon, the son and successor of Leopold,

stood at the west plaza

of the Administration building in the

presence of the greatest

Vol. XI-2.

18 Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

audience ever collected in one spot in

the history of the world,

holding in his hand the parchment

duplicate of the deed which

his father, sixty years before, had

signed, transferring the land

on which they then stood to the United

States. With due cere-

mony the chief presented to Mayor

Harrison, then Mayor of

Chicago, the well-worn parchment, the

duplicate of which had

been delivered by his father to the

United States Commissioners

at the time the sale and transfer of the

land was made. On

receiving the parchment, Mayor Harrison

spoke as follows:

"This deed comes from the original

possessors, - the only

people on earth entitled to it. The

Indians had for long ages

come to this place, the portage or

carrying-place between the

great rivers of the west and the great

inland lakes. They pitched

their tents upon these shores of blue

Michigan, and after their

barter was done returned to the Des

Plaines River and on to the

Mississippi and its twelve thousand

miles of tributaries. Chicago

has thrived as no city ever before.

Twenty-two years ago this

city was devastated by a deluge of

flame. The story of its suffer-

ing went to all quarters of the globe,

and the world supposed

that, like Niobe, it was in tears, and

would continue in tears.

But Chicago had Indian blood in its

veins. I say this as a de-

scendant of the Indians; for I stand

here and tell you that Indian

blood courses through my veins. I go

back to Pocahontas, and

Indian blood has wonderfully

recuperative powers."

To the disgrace of the United States,

the purchase price

of three cents an acre for more than a

million acres of land was

not paid according to agreement. The

original purchase price

amounted to more than three hundred

thousand dollars, and it

was not until 1866, during General

Grant's administration, that

Pokagon succeeded in getting by way of

partial payment $39,000;

and after further long and disappointing

and disheartening efforts

he finally secured in 1896 from the

government through the Court

of Claims $150,000 more, which

was about one-half of the origi-

nal purchase price, without interest,

when with interest a vastly

greater sum was due.

Leopold Pokagon died in 1840 in Cass county,

Michigan.

He was a man of noble character and of

pure and upright life,

and always labored to elevate and

improve his people. He was

Monuments to Historical Indian

Chiefs. 19

devoted to the teachings of the Jesuit

Fathers and invited and

encouraged their missionaries (the

Black-Gowns) to come among

them and teach his people to lead

temperate and upright lives.

In his appeal to M. Gabriel Richard,

then Vicar-General of a

Catholic church at Detroit, he plead as

follows: "Father, father,

I come to beg you to send as a

black-gown to teach us the Word

of God. We are ready to give up whisky

and all our barbarous

customs. If thou hast no pity on us take

pity on our poor chil-

dren, who will live as we have lived, in

ignorance and vice."

While the old chief lived he would not

allow traders or

others to bring intoxicating liquors

among his people and was

always an advocate of temperance and

religion, and exemplified

his principles by his own life and

conduct. He was present at

Fort Dearborn (Chicago) at the time of

the terrible massacre in

1812. This massacre was an incident of

the war of 1812, in

which the Indians under Tecumseh were

united with the English

under General Proctor, whose united

armies were overthrown

and destroyed at the Battle of the

Thames, October 5, 1813.

In 1838 an order was issued by Governor

David Wallace

(father of General Lew Wallace, author

of "Ben Hur"), then

Governor of Indiana, directing that the

Pottawattamies remain-

ing in Indiana should be removed by

force to lands beyond the

Mississippi, according to treaty

conditions before that time made,

but which had not been fulfilled on the

part of the United States.

This order, however, was most remorsely

carried out by General

Tipton, who, with a military force,

surprised and entrapped the

Indians at their villages in a most

heartless and dishonorable way.

Spies were sent among the unsuspecting

Indians, who informed

them that their Christian priest wished

all the tribes to meet

him at their wigwam church, and when

such as could do so were

assembled in the church, they were

suddenly surrounded by sol-

diers, of whose nearness or approach

they had no knowledge

or suspicion. It is related by an eye

witness that the soldiers

then tied the Indians so entrapped

"together with big strings

like ponies" and detained them as

prisoners and the next day

marched them off to the to them unknown

region beyond the

Mississippi. In the meantime the

military force gathered in many

more men, women and children, which,

with their captives at

20

Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

the church, made up a company of about

one thousand, whom,

with "broken hearts and tearful

eyes" were forced from their

ancient homes and such of their friends

and kindred as had

not been captured. Few of them ever

again returned. Many

women and children, and in some

instances men, escaped into

the woods and swamps and thus avoided

capture. Many families

were thus broken up never again to be

united. On the hard

journey to the West more than a hundred

of them died and a

few escaped into the wilderness, so that

there were more than

one hundred and fifty missing when they

arrived in the new

territory.

A large part of those so cruelly forced

from their homes

and in many instances from their

families were of the Menominee

band, whose chief, old Menominee, had

steadfastly refused to

sign any treaty, or to sell the lands

owned and occupied by his

band, and so had never parted with any

rights, titles or interests

which they had therein. This crime

against these peaceful and

well-disposed people was, as usual in

such cases, the result of

the insidious and nefarious schemes of

white land grabbers and

speculators by whom, it is probable,

Governor Wallace was de-

ceived and misled.

By a special agreement and contract

before that time made,

Leopold Pokagon and his band were to

remain in the State of

Michigan, within the region of St.

Joseph River, but in the in-

discriminate rounding up of the Indians

by the military many of

his band were captured and forced away

with others, regardless

of all rights and agreements, and of all

the dictates of conscience

and humanity. By this merciless crime

Pokagon's band was

much reduced and broken and his spirit

wounded unto death.

Two years later he died, after ruling

wisely and justly over his

people for the long period of

forty-three years, and his son,

Simon, then ten years of age, became the

rightful hereditary

chief of the Pottawattamie tribe.

SIMON POKAGON.

In Simon Pokagon we have one of the most

remarkable

and worthy characters which the red race

has produced. He

was a full-blooded Indian of the

Pottawattamie tribe, which tribe

|

Monuments to Historical Indian Chiefs. 21

was of the great Algonquin family, which when the white ex- |

|

|

|

plorers first came to America occupied the present territory of the New England States and the region of the St. Lawrence |

22 Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

and the Ottawa Rivers, and the vast

territory as far west as

the eastern shores of Lake Huron. As

before stated, he was

but ten years of age when his father,

Leopold Pokagon, died.

His mother survived for many years

thereafter and until he

had grown to manhood and had become the

active chief of the

remnant of his broken band. His fame is

not that of a warrior,

as he never had occasion to lead his

people to battle or go upon

the warpath.

The long and bloody wars and conflicts

between the white

and red race east of the Mississippi

ceased with the Battle of

the Thames, October 5, 1813. That decisive battle closed the

dreadful drama which for half a century

had been enacted upon

the territory of the great Northwest.

The raid of Black Hawk

into northwestern Illinois in 1832

cannot be considered as an

exception, as he and his warriors came

from the Fox and Sac

Nations beyond the Mississippi and was

opposed by the old

Pottawattamie chief, Shabbona, who

assisted the whites against

Black Hawk, and aided greatly in his

defeat and capture.

But it is as a scholar and philosopher

and wise ruler over

his people that Pokagon's fame consists.

Until he was fourteen

years of age he knew not a word of any

language but his mother

tongue. At that age he was sent to a

Notre Dame School, near

South Bend, Indiana, where he remained

for three years. Here

he began to learn the English, Latin and

Greek languages, in

which he ultimately became singularly

proficient. He had a

marvelous aptitude for acquiring

languages. He was especially

zealous in the acquirement of a thorough

knowledge of the Eng-

lish language. After three years he

returned to visit his mother,

who appreciated his high purposes and

added her efforts to his

own to enable him to realize his

ambitious desires. He then

spent one year at Oberlin College, Ohio,

and then went to Twins-

burg, Summit county, in the same state,

where he remained two

years longer. This gave him six years in

English teaching and

speaking schools, and laid the

foundation of his marvelous Eng-

lish education. No full-blooded Indian

ever acquired a more

thorough knowledge of the English

language or wrote or spoke

it with more fluency or accuracy. He,

however, never neglected

his native tongue, and succeeded in

after years in reducing his

Monuments to Historical Indian

Chiefs. 23

native language to considerable

perfection. His writings indi-

cate not only that he had great respect

for his own language, but

in some respects thought it superior to

others.

His life was not eventful in the

ordinary sense of Indian

chieftains, and his fame rests upon the

wonderful example

which he offered of the possibilities of

advancement of the Red

race in the lines of civilization. Born

at a time when all the

Indian habits of mind and thought and

life were still in full

force and vigor, he was able to emerge

from these environ-

ments and to turn his face and influence

towards a different

form of life and destiny. He was enabled

at an early age to

see the great advantage and necessity of

laying aside the imple-

ments of war and the chase to turn to

the cultivation of the

soil and to the procurement of permanent

homes; and it was in

this line that he always directed the

minds of his people. Other-

wise he plainly saw the speedy ending of

his race.

In the August number of "The

Forum," 1897, appeared

an article written by Pokagon, entitled,

"The Future of the Red

Man," which for lofty expressions

and profound reflections and

sentiments can scarcely be surpassed.

The first few sentences

will give an idea of his deep

reflections and his lofty plane of

thought. He says:

"Often in the stillness of the

night, when all nature seems

asleep about me, there comes a gentle

rapping at the door of my

heart. I open it; and a voice inquires,

'Pokagon, what of your

people? What will be their future?' My

answer is, 'Mortal

man has not the power to draw aside the

veil of unborn time

to tell the future of his race. That

gift belongs to the Divine

alone. But it is given to him to closely

judge the future by

the present and the past.' "

The article is full of wise and

philosophical thoughts and

reflections on the future of his race

and concludes as follows:

"The index-finger of the past and

present is pointing to

the future, showing most conclusively

that by the middle of the

next century all Indian reservations and

tribal relations will

have passed away. Then our people will

begin to scatter; and

the result will be a general mixing up

of the races. Through

intermarriage the blood of our people,

like the waters that flow

24 Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

into the great ocean, will be forever

lost in the dominant race;

and generations yet unborn will read in

history of the red men

of the forest, and inquire, 'Where are

they?' "

During the later years of his life, he

wrote for many maga-

zines, among them "The Forum,"

"The Arena," "Harper's,"

"The Chautauquan" and

"The American Review of Reviews."

He also made many speeches and

addresses, a most notable one

of which was on January 7th,

1898, at the Gem Opera House,

at Liberty, Indiana, under the auspices

of the Orinoco Tribe of

the Independent Order of Red Men. A few

extracts from that

address will show his elevation of mind

and nobility of soul.

He said:

"My heart is always made glad when

I read of the Daughters

of Pocahontas kindling their council

fires. * * * The names

of Pocahontas and Pokagon (my own name)

were derived from

the same Algonquin word-Po-ka-meaning a

"shield" or "pro-

tector." And again we are highly

complimented by the Order

of Red Men in dating their official

business from the time of

the discovery of America. I suppose the

reason for fixing that

date was because our forefathers had

held for untold ages

before that time the American continent

a profound secret from

the white man. Again, the Red Men's

Order highly compli-

ments our race by dividing time into

suns and moons, as our

forefathers did, all of which goes to

show that they under-

stood the fact that we lived close to

the Great Heart of Nature,

and that we believed in one Great Spirit

who created all things,

and governs all."

"Hence that noble motto, born with

our race,-Freedom,

Friendship and Charity,-was wisely

chosen for their guiding

star. Yes, Freedom, Friendship, Charity!

Those heaven-born

principles shall never, never die! It

was by those principles

our fathers cared for the orphan and the

unfortunate, without

books, without laws, without judges; for

the Great Spirit had

written his law in their hearts, which

they obeyed." * * *

"But our camp-fires have all gone

out. Our council fires

blaze no more. Our wigwams and they who

built them, with

their children, have forever disappeared

from this beautiful land,

and I alone of all the chiefs am

permitted to behold it again.

Monuments to Historical Indian

Chiefs. 25

"But what a change! Where cabins

and wigwams once

stood, now stand churches, schoolhouses,

cottages and castles.

And where we walked or rode in single

file along our winding

trails, now locomotives scream like some

beast of prey, rushing

along their iron tracks, drawing after

them long rows of palaces

with travelers therein, outstripping the

flight of eagles in their

course.

"As I behold this mighty change all

over the face of this

broad land, I feel about my heart as I

did in childhood when I

saw for the first time the rainbow

spanning the cloud of the

departed storm. * * *

"In conclusion, permit me to say, I

rejoice with the joy of

childhood that you have granted 'a son

of the forest' a right

to speak to you; and the prayer of my

heart, as long as I live,

shall ever be that the Great Spirit will

bless you and your

children, and that the generations yet

unborn may learn to know

that we are all brothers, and that there

is but one fold, under

one Shepherd, and the great God is the

Father of all."

At the opening of the great World's Fair

at Chicago, May

1st, 1893,

the old chief was present with other educated repre-

sentatives of his tribe and race, but

the occurrences of the

day deeply wounded and humiliated him.

There had been great

preparations made for this event. The

ceremonies were held

under the dome of the great

Administration Building. Presi-

dent Cleveland was to respond to the address

of welcome, and

there were present the representatives

of many nations. The

Duke of Veragua was there with his

suite, especially invited

as the lineal representative of

Columbus, usually accredited as

the first discoverer of America. All of

these numerous foreign

representatives were provided with seats

upon the great plat-

form, where they could observe the

ceremonies, while Pokagon

and his Indian associates, who alone

represented the original

Americans, were forgotten and compelled

to look silently on

from the background, while the

representatives of foreign na-

tions took their provided places to

participate in the glittering

pageant. This occurrence, on the very

ground which his tribe

only a few years before had owned and

occupied for centuries,

and where in his youth he had encamped

and hunted with his

26 Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

father, and where he had roamed and

played with other children

of the forest, wounded his very soul and

made a deep and un-

fortunate impression upon his mind.

However, this unintentional

neglect was productive of great good,

and subsequently most

amply and notably atoned for. It

inspired him to write "The

Red Man's Greeting." It was

published in booklet form made

from the bark of the white birch tree

and was widely circu-

lated and read, and created a marked

impression on the public

mind. It was fitly termed by Prof.

Swing, "The Red Man's

Book of Lamentations."

The managers of the fair and the people

of Chicago soon

took steps to atone for this

unintentional but seeming neglect and

arranged so that the old chief should be

the central figure of

attraction on the great "Chicago

Day," which was appointed

for October 9th, 1893. This was carried

out in form and spirit

and no King or Potentate was ever the

center of attraction of

so vast an assemblage of people. The

pertinent features of this

occasion, as relates to Pokagon, have

already been mentioned

and need not here be repeated.

Subsequent to that time he engaged much

in literary labors

more or less of a historical character,

but in the meantime wrote

the charming story, "Queen of the

Woods," founded upon his

own life's experiences. He had finished

the work but died sud-

denly before its publication. It is a

simple, natural, pure and

pleasing narrative, and has a charm

something akin to that

which is experienced in reading

"The Vicar of Wakefield." There

is in its pages nothing less pure than

the song of birds, the

blooming of wild flowers and the

divinely fresh fragrance of the

forest.

Pokagon died on the 28th day of January,

1899, at his old

home in Allegan County, Michigan, at the

age of seventy years,

and thus passed away the last and most

noted chief of the

once powerful Pottawattamie tribe. As a

separately organized

tribe they no longer exist. At the time

of his death all the

leading papers of Chicago published

notices of the event with

sketches of his life and character and

these were widely copied

throughout the press of the country. At

once steps were taken

to have his remains buried in Graceland

Cemetery, Chicago.

Monuments to Historical Indian

Chiefs. 27

That organization donated a lot for that

purpose, located near

the grave of John Kinzie, the first

white resident of Chicago,

and his remains were there laid to rest.

As to the proposed monument the Chicago

Inter-Ocean,

under date of March 16th, 1899, says:

THE POKAGON MONUMENT.

"The last hereditary chief of the

Pottawattamies having

died a few weeks ago, an organization

has been formed in

Chicago to erect a monument to his

memory and to that of

his father, Pokagon I, who was the great

chief of the Potta-

wattamies during the days of the second

Fort Dearborn and

early Chicago.

The only memory left for coming

generations of this race

is the beautiful monument erected by the

late Mr. George Pull-

man on the site of the massacre of the

first fort's days.

The new Indian monument will be erected

in Jackson Park,

where throngs of visitors may become as

familiar with its story

as they are with that of the Massacre

Monument.

The new monument will be erected in

memory of the late

Simon Pokagon, and will have inscribed

upon it his own beau-

tiful words to the children of Chicago,

that "the red man and

white man are brothers, and God is the

Father of all."

Surmounting the pedestal will be a

superb statue of the

regal figure of Pokagon I in full

chieftain's attire. The four

bas-reliefs on the pedestal will

represent events in the history

of Chicago's Indian days, which will be

decided upon by a com-

mittee of pioneers. The names, also, of

noted Pottawattamie

chiefs who were at the head of bands

under Pokagon will be

inscribed upon the base of the

monument."

It is not known, and probably never can

be definitely known,

what period has elapsed between the

passing of the Mound

Builders and the coming of the white

man; but it must have

covered several centuries of time.

During that period the oc-

cupants of the land left no substantial

or material monuments

or marks to indicate their burial places

or to evidence an in-

tention to perpetuate the fact of their

occupancy of the country.

The continent has now been explored from

ocean to ocean

and from the gulf to the Arctic seas,

and practically all that

28 Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

we accurately know of the Indian race is

what has been learned

of them from contact with them by the

white race.

It is true that they have many

traditions concerning their

origin and history, but they are too

vague and uncertain to be

accepted as in any way reliable, or as

shedding any certain light

upon their past history. Through what

ages human beings have

lived and roamed and energized over this

continent can never

be accurately determined, but enough is

known to make it cer-

tain that human life has existed here

where we are now for

many thousands of years. All that

preceded the period of the

Mound Builders is wrapped in oblivion

and can now be only

a matter of speculation or conjecture.

But with the Mound

Builders came a race, who marked the

surface of the earth

with countless evidences of their once

energetic existence, which

are now being industriously examined by

scientists to discover

what secrets they may reveal.

Following the Mound Builders came what

we know as the

Indian race, who, like the ancient

occupants of the country, failed

to leave any records or testimonials

concerning themselves from

which we might determine something of

their history. They

have now practically passed away as a

separate and distinct race,

and within a few years, as suggested by

Simon Pokagon, the

remnant which is left will be absorbed

and swallowed up in the

blood of the dominant race. That the

tincture of their blood

will flow on in that of the white race

and possibly for its bet-

terment is reasonably certain; but as a

distinct race their end is

comparatively near at hand.

These considerations make it all

important that in so far

as possible the history of the Red race

should be preserved for

the benefit and study of future

generations. The interest in their

history is gradually growing and will

ever be increasing. The

number of white men now living, who came

in personal contact

with and have had personal knowledge of

the Indians of various

tribes east of the Mississippi, is now

very small and soon will

have passed away. With them will have

passed those who

can testify from personal knowledge as

to the nobility and

worth of individual representatives of

the Red Race, with whom

they have had contact and companionship.

When they are gone,

we will be remitted to the doubtful

narratives and incidental

Monuments to Historical Indian

Chiefs. 29

references to be found in our histories

to form and estimate

of the Red Race and its leading

characters. At least most of

our narratives concerning the Indian

race and tribes as also of

their individual chiefs, were written at

or near the times when

wars and conflicts and race hatreds

prevailed and so are strongly

tinctured by prejudices and often

narrated without regard to

substantial facts or truths. A new and

better era has dawned

upon us, when we can hope to feel the

force of the lofty senti-

ments expressed by Simon Pokagon in his

address before quoted,

"That we are all brothers and that

there is but one fold, under

one Shepherd, and the great God is the

Father of all."

The few monuments that have been erected

by white men

to commemorate and perpetuate the names

and virtues of worthy

representatives of the Red race do not

at all satisfy the obli-

gations which rest upon us in that

behalf. There are in so far

as we know, but seven such monuments

which have been erected

up to the present time, but one of which

is on the soil of Ohio

-that of Leatherlips-while the wise and

good Chief Crane

of the Wyandots; the great war chief

Pontiac of the Ottawas;

Logan of the Mingos; Tecumseh, Black

Hoof and Blue Jacket

of the Shawnees; Little Turtle of the

Miamies; all of whom

at times lived and energized on the soil

of Ohio, remain monu-

mentless and the exact places of their

burials unknown.

It would seem not only fitting but just

that these chiefs

and tribes, who were the original

occupants and possessors of

the soil, should have suitable and

enduring monuments to com-

memorate their names placed in public

parks, or on grounds

owned and cared for by the State of

Ohio, so that our children

and our children's children may have

kept before them a recol-

lection of a race of men who contended

with us for more than

two centuries for the possession of the

country, but who have

been vanquished and almost exterminated

by our superior force.

That our government is now using its

best endeavors to care for,

educate and elevate the remnant of the

Red race is all to our

credit, but this does not lesson the

obligation to care for and

keep alive the memories of their great

men of the past. It will

be a discredit to our own civilization

to neglect this obvious duty.