Ohio History Journal

THE DUNMORE WAR.*

BY E. O. RANDALL.

Secretary Ohio State Archaeological

and Historical Society.

The American colonists had fought the

French and Indian

war1 with the expectation that they were

to be, in the event of

success, the beneficiaries of the result

and be permitted to occupy

the Ohio Valley as a fertile and

valuable addition to their Atlantic

coast lodgments. But the war over and

France vanquished, the

royal greed of Britain asserted itself,

and the London government

most arbitrarily pre-empted the

territory between the Alleghanies

and the Mississippi as the exclusive and

peculiar dominion of the

Crown, directly administered upon from

the provincial seat of

authority at Quebec. The parliamentary

power promulgated the

arbitrary proclamation (1763) declaring

the Ohio Valley and the

* Authorities consulted in preparation

of the article on Dunmore's

War-E. O. R.: Abbott's History of Ohio;

Albach's Western Annals;

American Archives (4th Series, Vol. 1);

Atwater's History of Ohio;

Bancroft's History of the United States;

Black's Story of Ohio; Brow-

nell's Indians of North America; Burk's

History of Virginia; Butler's

History of Kentucky; Butterfield's

History of the Girtys; Campbell's

History of Virginia; Cook's History of

Virginia; Doddridges's Notes

on Indian Wars, etc.; Drake's Indians of

North America; Drake's life

of Tecumseh; Fernow's Ohio Valley in

Colonial Days; Fiske's Ameri-

can Revolution, Vol. II; The Hesperian,

Vol. II., (1839); Hildreth's

Pioneer History of the Ohio Valley;

Hosmer's Short History of the

Mississippi Valley; Howe's Historical

Collections of Ohio; Howe's His-

torical Collections of Virginia; Jacob's

Life of Cresap; Jefferson's Notes

on Virginia; Kercheval's History of the

Valley of Virginia; King's His-

tory of Ohio; Lewis's History of West

Virginia; Mayer's (Brantz)

Logan and Cresap; McDonald's sketches;

McKnight's Our Western Bor-

der; Mitchener's Ohio Annals; Moore's

Northwest Under Three Flags;

Monette's Valley of the Mississippi;

Ohio Archaeological and Historical

Publications; Olden Time (Monthly), Vol.

II; Peter Parley's History

of the Indians; Ryan's History of Ohio;

Roosevelt's Winning of the

West; Stone'sLife of Joseph Brant;

Taylor's (J. W.) History of Ohio;

Thatcher's Indian Biographies;

Thwaites's Afloat on the Ohio; Vir-

ginia Historical Register (Vol. V);

Walker's History of Athens County;

Whittlesey's Fugitive Essays; Winsor's

Western Movement; Withers'

Chronicles of Border Warfare.

11756-1763. (167)

168 Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

Great Northwest territory should

practically be an Indian reserva-

tion, ordering the few straggling

settlers to move therefrom,

forbidding the colonists to move

therein, and even prohibiting

trading with the Indians, save under

licenses and restrictions so

excessive as to amount to exclusion.

On June 22, 1774, Parliament passed the

detestable Quebec

Act which not only affirmed the policy

of the Crown adopted in

the proclamation of 1763, but added many

obnoxious features, by

granting certain religious and civil

rights to the French catholic

Canadians.

This policy of the Crown stultified the

patents and charters

granted the American colonies in which

their proprietary rights

extended to the Mississippi, and beyond,

embracing the very

territory to which they were now denied

admittance2.

The establishment of England's authority

in Canada, with

Quebec as the seat of arbitrary and

direct rule over the colonies,

was a tightening of the fetters that

bound the chafing colonies.

The Quebec Act was one of the irritants

complained of in the

Declaration of Independence "for

abolishing the free system of

English law in a neighboring province,

establishing therein an

arbitrary government and enlarging its

boundaries so as to render

it at once an example and fit instrument

for introducing the same

absolute rule into these colonies."

The French Canadians were

favored by the Quebec Act in their legal

rights and religious

privileges. The untutored savages were

its especial foster chil-

dren. The colonists were flagrantly and

unjustly discriminated

2 "In

1763, at the close of the French and Indian War, the English

Parliament passed an act which

disfranchised the Catholics of Canada,

and cut off the revenues of their

church. This law continued in force

until October, 1774, when Parliament,

having received intelligence of

the "Boston Tea Party," and

fearing that the Canadians would unite

with her now disaffected colonies,

enacted what is known as "The Quebec

Act." By it the boundaries of that

province were extended to the Ohio

and Mississippi rivers; the old French

laws were restored in all judicial

proceedings, and to the Catholics were

secured the enjoyment of all

their lands and revenues. Thus it is

seen that the present State of Ohio

was made a part of Quebec, and the

inhabitants of the District of West

Augusta were correct in their

representations to Congress that the Ohio

was all that separated them from

Quebec."--Lewis, History of West

Virginia, p. 139. This last (1774) act

was especially obnoxious to the

American colonists.

The Dunmore War. 169

against. The restless enterprise and

obstinate opposition of the

frontier settlers led them to encroach

and "poach" upon the "pre-

serves" of the Crown. The fearless

and independent frontiersman

of Pennsylvania and Virginia longed for

the unrestrained oppor-

tunity to cross the Ohio, and pushing

their way into the trackless

wilderness, seek homes upon the banks of

the Tuscarawas, the

Muskingum, the Scioto, the Sandusky and

the Miamis. They

went first as hunters, then as

prospectors, and finally as settlers;

"they purchased lands with bullets,

and surveyed claims with

tomahawks."

Such was the situation until the year

1774 when the smoulder-

ing embers burst into a flame, and

Dunmore's war was the prelude

to the Revolution. The Dunmore war has

been promotive of

much ingenious speculation and curious

guesswork by writers and

historians. An air of semi-mystery

heightens the intense interest

that attaches to this most important and

romantic event in western

American history. John Murray, Earl of

Dunmore, was the royal

governor of Virginia colony. He was a

descendant in the feminine

line from the house of Stuart; the blood

of the luxurious, im-

perious and haughty Charleses ran in his

veins. He was a Tory of

the Tories. He was an aristocratic,

domineering, determined,

diplomatic representative of his

sovereign, King George, but he

was also a tenacious stickler for the

prerogatives of the colony

over which he presided. He held his

allegiance as first due the

Crown, but he also was "eager to

champion the cause of Virginia

as against either the Indians or her

sister colonies." He was

avaricious, energetic and interested in

the frontier land specula-

tions. He had an eye for the main

chance, financial and political.

He could not have looked complacently

upon the Canadian policy

of his government. But he was the center

of opposing influences.

The prescribed limits of the various

colonies, while generally dis-

tinctly defined near the Atlantic coast,

often became indefinite and

conflicting west of the mountains. The

grant to Virginia gave

her a continuation of territory west

across the continent, and

according to her claim took in the

southern half of Ohio, Indiana

and Illinois. The Quebec Act nullified

this claim and incurred the

disfavor of Dunmore, who defiantly

opposed this injustice to his

colony. More than this the Virginians

assumed title to all of the

extreme western Pennsylvania, especially

the forks of the Ohio

170 Ohio Arch. and His.

Society Publications.

river and the valley of the Monongahela.

This, of course, meant

Fort Pitt, which, at this time was

occupied as a Virginian town,

though claimed by the Pennsylvanians as

their territory.

Governor Dunmore appointed as his agent

or deputy at Fort

Pitt one Dr. John Connolly, a man of

reputed violent temper and

bad character. Connolly was named vice

governor and command-

ant of Pittsburg and its dependencies.

Connolly was at best an

impetuous and unscrupulous minion of his

master. He changed

the name of the settlement from Fort

Pitt to Fort Dunmore, and

proceeded to assume jurisdiction in such

an arrogant and merciless

manner in behalf of the Virginians, and

against the peaceable

Pennsylvanians, that a war-like

collision was narrowly averted3.

Connolly's counter plays between the

Virginians, the Penn-

sylvanians, the Indians and the British

authorities are too complex

and contradictory to be unravelled here.

Whatever Lord Dun-

3 In the winter of 1773-4, one Dr. John

Connolly, a nephew of

George Croghan, determined to assert the

claims of Virginia upon Fort

Pitt and its vicinity. He issued a

proclamation to the inhabitants to

meet at Redstone, now Brownsville, on

the 24th and 25th of January,

1774, and organize themselves as a

Virginia militia. Before the time

appointed Connolly was arrested by

Arthur St. Clair, who then repre-

sented the Pennsylvania proprietors at

Pittsburg, and the assemblage

at Redstone dispersed without definite

action. As soon as Connolly was

released from custody, however, he

renewed his efforts to establish the

exclusive authority of Virginia. He came

to Pittsburgh on the 28th

of March, with an armed band of

followers, and in the name and by

the authority of Lord Dunmore,

proclaimed the jurisdiction of Virginia,

rebuilding Fort Pitt, which was called

Fort Dunmore. He was recog-

nized as Captain Commandant of a

district called West Augusta, and

almost immediately exhibited a

tyrannical spirit to all who were in the

Pennsylvania interest, while he seemed

not unwilling to involve the

frontier in an Indian War, one motive

for the latter policy being, as

suggested by Arthur St. Clair and

others, to cloak his extravagant civil

expenditure, with the indefinite item of

frontier defence.-Taylor (J.

W.), History of Ohio, pp. 242-3.

American Archives, 4th Series, Vol. I,

p. 270 et seq. contains

numerous letters and documents revealing

the riotous state of affairs

prevailing at Fort Pitt after the

arrival there of John Connolly, who,

though a native of Lancaster county,

Pennsylvania, was regularly com-

missioned by Lord Dunmore to represent

his lordship's authority as

magistrate for West Augusta, the county

Dunmore had added to Vir-

ginia from Pennsylvania territory.--E.

0. R.

The Dunmore War. 171

more was, this man Connolly was

double-dyed in duplicity. He

pitted one colony against the other, the

Indians against both, and,

so far as he could, doubtless aided the

British to urge on the

Indians. That the British authorities

were, in this whole affair,

the abettors of the savages, is

sufficiently evidenced by the fact

that while the Indians were openly and

unitedly fighting the

colonies who were still British subjects

on the Ohio frontier, they

(the Indians) were receiving arms,

ammunition and provisions

from the English distributing station at

Detroit4.

The Canadian French traders who drove a

thriving business

with the Indians naturally stimulated

them to resist the frontiers-

men's encroachments. The occupation of

the exclusive territory

by the colonists meant the termination

of their traffic. The brunt

of this contention fell upon the Ohio

Indians and the Virginian

backwoodsmen. The six nations as such

took no part in it. The

Pennsylvanians stood aloof. They were

not so aggressive as

their southern neighbors, and their

interest in the Indian was a

commercial and peaceful one. The

Virginians, therefore, were

the only foes the Ohio Indians really

dreaded. The Virginians

were crack fighters in those frontier

days. They were adventur-

ous, courageous, and of hardy stuff. In

the mountain dwellers

of the Monongahela and Kanawha valleys

the red man found a

foeman worthy of his prowess. It was

they the Indians styled

the "long knives," or

"big knife," because of the bravery they

displayed in the use of their long belt

knives, or swords. They

were a match for the deadly tomahawk.

Another reason why

the Virginians were willing and active

aggressors in these border

difficulties was that the royal

authority had promised the Vir-

ginia troops a bounty in these western

lands as reward for their

services in the French and Indian war. A

section had been

allowed them by royal proclamation on

the Ohio and Kanawha

rivers. When in the spring of 1774

Colonel Angus McDonald

4 "For it is well known that the

Indians were influenced by the

British to continue the war to terrify

and confound the people, before

they commenced hostilities themselves

the following year in Lexington.

It was thought by British politicians

that to excite an Indian war would

prevent a combination of the colonies

for opposing parliamentary meas-

ures to tax the Americans." -

Narrative of Capt. John Stuart in the Vir-

ginia Historical Register, Vol. V, p.

188.

172 Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

and party proceeded to survey these

lands they were driven off by

the Indians. Meanwhile, intrusions

across the border, depreda-

tions, conflagrations and massacres were

committed in turn by

either side. Much has been written as to

which was the earlier

or greater aggressor. That discussion is

not pertinent to our

purpose. Many cabins were burned and

many lives brutally de-

stroyed. Havoc and horror were

prevalent.

Most prominent among the leaders of the

whites in this In-

dian warfare was one Captain Michael

Cresap, a Marylander

who removed to the Ohio early in 1774,

and after establishing

himself below the Zane settlement

(Wheeling) organized a com-

pany of pioneers for protection against

the Indians5. He was

appointed by Connolly, a captain of the

militia of the section in

which he resided, and was put in command

of Fort Fincastle3.

Cresap was a fearless and persistent

Indian fighter, and just the

one to lead retalitory parties across

the Ohio into the red men's

country. In April, Connolly, only too

anxious to spring the ex-

plosion, issued an open letter warning

the frontiersmen of the

impending war and commanding them to

prepare to repel the

Indian

attack7. Such a

letter from Dunmore's

lieutenant

amounted to a declaration of war. The

backwoodsmen were at

once in arms and seeking an opportunity

to fight. As soon as

Cresap's band received Connolly's letter

they proceeded to declare

war in regular Indian style, calling a

council, planting the war

post, etc. What is sometimes known as

"Cresap's war" ensued.

Several Indians while descending the

Ohio in their canoes were

killed by Cresap's company. Other

Indians were shot within the

Ohio border by intruding and exasperated

whites. Logan, chief

of the Mingos, established a camp near

the mouth of Yellow

This individual (Captain Michael

Cresap), owing to the beauty

and eloquence of the Logan speech, has

acquired a reputation, certainly

not to be envied, and which we verily

believe he does not merit. He

was an early martyr in the cause of his

country, in the struggle for

independence, and we feel it to be a

duty and a pleasure to do him

justice. That he killed some Indians in

the spring of 1774, seems un-

deniable, but that he was clear of any

connection with the Yellow Creek

outrage is equally certain.-Craig's

Olden Time, Vol. II, p. 65.

6 Monette's

Valley of the Mississippi, Vol. I, p. 370.

7Roosevelt,

Winning of the West, Part I, p. 257.

The Dunmore War. 173

creek, about forty miles above Wheeling.

It was first thought

Logan's camp was a hostile

demonstration, and the camp should

be attacked and destroyed. Cresap and

his party proposed and

started to do this, but finally thought

better and decided Logan's

intentions were peaceful, - for he had

ever been the friend of the

whites, - and the intended attack was

abandoned. But Logan's

people did not escape. Opposite the

mouth of Yellow creek on

the Virginia side of the Ohio resided an

unscrupulous scoundrel

and cut-throat, Daniel Greathouse, and

fellow frontier thugs.

They kept a carousing resort, known as

Baker's Bottom, where

the Indians were supplied with rum, at

Baker's cabin. On the

last day of April, a party of Indians

from Logan's camp, on the

invitation of Greathouse, visited

Baker's place and while plied

with liquor were set upon and massacred.

There were nine, in-

cluding a brother and a sister of Logan,

the latter being the re-

puted squaw of John Gibson, who were

thus foully murdered.

Other relatives of Logan had been

previously killed. The Baker

massacre is one of the most awful blots

upon the white man's

record. Michael Cresap was not present

and had nothing

to do with the dastardly deed, and his

innocence in the af-

fair is well established, though many

authorities still couple

his name with the plot, if not the act

itself. Logan be-

lieved Cresap to be the guilty party, as

is evidenced by his using

Cresap's name in the famous speech8.

There were many bloody

enactments. Vengeance and retalition

were resorted to equally

by both sides. The malevolent murder of

Bald Eagle, the Dela-

ware chief, of Silver Heels, the

Shawanee chief, the malignant

massacre of the mother, brother, sister

and daughter of the famous

Mingo chief Logan, were but incidents

among many that aroused

8A vast deal of literature pro and con

is extant concerning Cresap's

relation to the murder of Logan's

family. This subject has been pretty

thoroughly worked over in Jacob's Life

of Cresap; Brantz Mayer's Logan

and Cresap; Jefferson's Notes on

Virginia; American Pioneers, Vol. I

(1842); The Olden Time, Vol. II (edited

by Craig), and many other

publications. The best vindication of

Cresap is the statement of George

Clark as printed in The Hesperian Vol.

2. 309, 1839. The evidence is

conclusively in favor of the innocence

of Cresap in the Baker's Bottom

massacre. Cresap was made captain of a

company in Dunmore's com-

mand.- E. O. R.

174

Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

the hostility of the Indians to a

furious pitch. They thirsted for

the warpath. The white borderers were no

less anxious for the

encounter. Lord Dunmore did not wish to

repress it. While the

solitude of the western forest was

broken by the war whoop, and

the crack of the white man's deadly

rifle, and the midnight sky

was lighted with the flaming cabin, and

the burning ripened crops,

the citizens of the New England colonies

were no less astir with

intense excitement. Freedom was

beginning to breathe. Meet-

ings were being held to protest against

royal tyranny, and com-

mittees of correspondence were sending

forth their missives

laden with the ideas of independence. It

was 1774. The Boston

Port Bill had been passed by parliament

in March, and denounced

in the Boston public meeting in May.

That same month the Vir-

ginia House of Burgesses, of which

George Washington, Patrick

Henry and Thomas Jefferson were members,

assembled at Wil-

liamsburg, the colony capital, and

resolved "with a burst of in-

dignation," to set aside the first

of June, when the Port Bill

should go into operation, "as a day

of fasting and prayer to

implore the divine interposition for

averting the heavy calamity

which threatens the civil rights of

America." The right honor-

able, the Earl of Dunmore, governor of

Virginia, at once dissolved

that highly impertinent king-insulting

assembly. The Virginians

saw the clouds gathering in the east.

But the storm in the west

was howling at their door. They were

prepared to take up arms

for their political rights against the

mother government, while

they hastily made ready to fight for

their proprietary rights

against their hostile neighbors, the

forest savages. The panic

among the inhabitants along the river

banks, and for a distance

inland, had become terrible. The time to

strike could not be de-

layed. Both red men and pale faces were

spoiling for the fray.

When Dunmore learned of the failure of

the surveying

expedition of Colonel Angus McDonald, he

authorized that brave

soldier to raise a regiment and proceed

into the country of the

enemy and punish them. McDonald easily

collected some four

hundred militiamen, and crossing the

mountains moved down the

Ohio to the site of Wheeling, where he

built Fort Fincastle, after-

wards Fort Henry. In June he descended

the Ohio to Captina

creek, the scene of one of the late

massacres, and there the men

The Dunmore War. 175

debarking from their boats and canoes,

made a dashing raid upon

the Shawnee villages as far as

Wappatomica, an Indian town on

the Muskingum, near the present city of

Coshocton.

The little army suffered many hardships,

and encountered

many perils. At times their only

sustenance consisted of weeds

and one ear of corn a day. Many villages

and fields of crops were

destroyed. The soldiers returned in a

few weeks without serious

loss. This forceful invasion of the

Indian country was sufficient

declaration of war, and produced a

general combination of the

various Indian tribes northwest of the

Ohio.

Meanwhile the Virginians were girding up

their loins. Gov-

ernor Dunmore was awake to the

situation. His actions have been

both attacked and applauded. He is

credited with moving

promptly and zealously in defense of his

colony, and in defiance

of the policy and public promulgation of

the sovereign powers

concerning the inhabited Indian

province. He is charged with

using this opportunity, in view of the

coming colonial revolt, to

bring about a clash between the

ferocious Indians and the strength

and flower of Virginian soldiery that

the onslaught might divert

the attention of the colonists from the

threatening rebellion

against the mother country, and through

the inhuman methods of

the savage and the ensuing calamities

and atrocities cause the

Americans to pause in, if not positively

desist from, their further

procedure towards independence. The

proof of his alleged

treachery is not conclusive. His

movements in this war were at

times not above suspicion, and his

subsequent proceedings were

such as to add grave conjectures

concerning his integrity. But

Dunmore thus far seems entitled to the

benefit of a doubt.

9Even

Lord Dunmore, that bitter enemy of the colonies and stead-

fast upholder of the British cause,

ignored the western policy of the home

government. His personal

characteristics, love of money and of power,

contributed to this end. "His

passion for land and fees," says Bancroft,

"outweighing the proclamation of

the king and reiterated most positive

instructions from the Secretary of

State, he supported the claims of

the colony to the West, and was a

partner in two immense purchases

of land from the Indians in southern

Illinois." - Hinsdale's Old North-

west, p. 144. When the Revolutionary War

broke out the Earl not only

fought the revolted colonists with all

legitimate weapons, but tried to in-

cite the blacks to servile insurrection,

and sent agents to bring his old foes,

176 Ohio Arch. and His.

Society Publications.

In August the governor began his

preparations and the

plan for the campaign agreed upon. An

army for offensive

operations was called for. Dunmore

directed this army should

consist of volunteers and militiamen,

chiefly from the countries

west of the Blue Ridge, and be organized

into two divisions. The

northern division, comprehending the

troops collected in Fred-

erick, Dunmore (now Shenandoah), and

adjacent counties, was

to be commanded by Lord Dunmore in

person; the southern di-

vision comprising the different

companies raised in Botetourt,

Augusta and adjoining counties east of

the Blue Ridge, was to be

led by General Andrew Lewis. The two

armies were to number

about fifteen hundred each; were to

proceed by different routes,

unite at the mouth of the Big Kanawha,

and from thence cross

the Ohio and penetrate the northwest

country, defeat the red

men and destroy all the Indian towns

they could reach.

The volunteers who were to form the army

of Lewis began to

gather at Camp Union, the Levels of

Greenbrier (Lewisburg)

before the first of September. It was a

motley gathering. They

were not the king's regulars, nor

trained troops. They were not

knights in burnished steel on prancing

steeds. They were not

cavaliers' sons from luxurious manors.

They were not drilled

martinets. They were, however, determined, dauntless men,

sturdy and weather-beaten as the

mountain sides whence they

the redmen of the forest down on his old

friends, the settlers. He

encouraged piratical and plundering

raids, and on the other hand failed

to show the courage and daring that are

sometimes partial offsets to

ferocity. But in this war, in 1774, he

conducted himself with great

energy in making preparations, and

showed considerable skill as a nego-

tiator in concluding the peace, and

apparently went into the conflict with

hearty zest and good-will. He was

evidently much influenced by Con-

nolly, a very weak adviser, however, and

his whole course betrayed

much vacillation and no generalship.-

Roosevelt's Winning of the West,

Part II; footnote under p. 14. These two

objects (speaking of Dun-

more's ulterior designs) were first,

setting the new settlers on the west

side of the Alleghany by the ears; and

secondly, embroiling the western

people in a war with the

Indians.--Jacob's account of Dunmore's War,

as quoted in Kercheval's Valley of

Virginia, p. 160.

The above citations represent the

opposite views taken of Dun-

more's purposes. The better belief now

coincides with such opinions

as are expressed by Roosevelt and

Hinsdale. - E. O. R.

The Dunmore War. 177

came. They were undrilled in the arts of

military movements, but

they were in physique and endurance and

power nature's noble-

men, reared amid the open freedom and

hardihood of rural life.

The army as finally made up consisted of

four main commands,

a body of Augusta troops, under Colonel

Charles Lewis, brother

of the General; a contingent of

Botetourt troops, under Colonel

William Fleming; those commands numbered

four hundred each;

a small independent company, under

Colonel John Field, of Cul-

pepper; a company from Bedford, under

Captain Thomas Buford,

and two from the Holstein settlement

under Captains Evan Shelby

and Harbert. The three latter companies

were part of the force

to be led by Colonel Christian, who was

likewise to join the two

main divisions of the army at Point

Pleasant as soon as the other

companies of his regiment could be

assembled.

The army started on September 8th in

three divisions, the

two under Colonel Charles Lewis and

General Andrew Lewis,

respectively, followed by the rather

irregular and independent

force under Colonel John Field. Colonel

Christian's contingent

left later, and portions of them did not

reach Point Pleasant in

time to engage in the battle, but

Captains Shelby and Russell,

with parts of their companies, hastened

ahead and did valiant

service in the engagement. It was a

distance of one hundred and

sixty miles from Camp Union to their

destination at the mouth

of the Kanawha. The regiments passed

through a trackless forest

so rugged and mountainous as to render

their progress extremely

tedious and laborious. They marched in

long files through "the

deep and gloomy wood" with scouts

or spies thrown out in front

and on the flanks, while axmen went in

advance to clear a trail

over which they would drive the beef

cattle, and the pack-horses,

laden with provisions, blankets and

ammunition. They struck out

straight through the dense wilderness,

making their road as they

went10. On September 21st they reached

the Kanawha at the

mouth of Elk creek (present site of

Charleston). Here they

halted and built dug-out canoes for

baggage transportation upon

the river. A portion of the army

proceeded down the Kanawha,

10 The country at this time, in its

aspect, is one of the most romantic

and wild in the whole Union. Its natural

features are majestic and

grand. Among the lofty summits and deep

ravines, nature operates on

12 Vol. XI.

178 Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

while the other section marched along

the Indian trail, which

followed the base of the hills, instead

of the river bank, as it was

thus easier to cross the heads of the

creeks and ravines. Their

long and weary tramp was ended October

6th, when they camped

on Point Pleasant, the high triangular

point of land jutting out on

the north side of the Kanawha where it

empties into the Ohio11.

General Lewis was disappointed in not

finding Governor Dun-

more at the appointed place of meeting.

Dunmore was far away.

While the backwoods general was

mustering his "unruly and tur-

bulent host of skilled riflemen"

the Earl of Dunmore had led his

own levies12, some fifteen

hundred strong, through the mountains

at the Potomac Gap to Fort Pitt. Here he

changed his plans and

decided not to attempt uniting with

Lewis at Point Pleasant.

Taking as scouts George Rogers Clark,

Michael Cresap, Simon

Kenton12a and Simon Girty, he descended

the Ohio river with a

a scale of grandeur, simplicity and

sublimity scarcely ever equaled in

any other region, and never surpassed in

the world. At the time of this

expedition only one white man had ever

passed along the dangerous

defiles of this route. That man was

Captain Matthew Arbuckle, who was

their pilot on the painful and slow

march. -Atwater's History of Ohio,

p. 112.

11 The site upon which the Virginia army

encamped was one of

awe-inspiring grandeur. Here were seen

hills, valleys, plains and prom-

ontories, all covered with gigantic

forests, the growth of centuries, stand-

ing in their native majesty unsubdued by

the hand of man, wearing the

livery of the season, and raising aloft

in mid-air their venerable trunks

and branches, as if to defy the

lightning of the sky and the fury of the

whirlwind. The broad reach of the Ohio

closely resembled a lake with

the mouth of the Kanawha as an arm or

estuary, and both were, at

that season of the year, so placid as

scarcely to present motion to the

eye. Over all, nature reigned supreme.

There were no marks of in-

dustry, nor of the exercise of those

arts which minister to the comforts

and convenience of man. Here nature had

for ages held undisputed

sway over an empire inhabited only by

the enemies of civilization.-

Lewis's History of West Virginia, p.

121.

12 Dunmore

himself raised about a thousand men among the old

Virginians east of the Blue Ridge for

this expedition. With these men

he marched by the old route in which

Washington and Braddock had

passed the Alleghenies. He marched up

the Potomac to Cumberland,

thence across the remaining mountains to

Fort Pitt. Here procuring

boats, he descended the Ohio river to

Wheeling, where he rested several

days, and concluded to change his

mind.-Atwater's History of Ohio,

p. 114.

12a Known at that time as Simon Butler.

The Dunmore War. 179

flotilla of a hundred canoes, besides

keel boats and pirogues, to the

mouth of the Hockhocking, where he built

and garrisoned a small

stockade, naming it Fort Gower. Thence

he proceeded up the

Hockhocking to the falls, moved overland

to the Scioto, finally

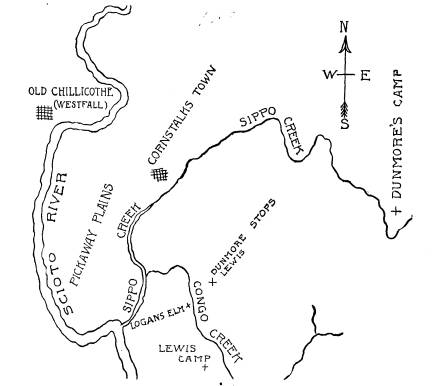

halting on the north bank of the Sippo

creek four miles from its

mouth at the Scioto, and about the same

distance east of Old

Chillicothe, now Westfall, Pickaway

county. He entrenched him-

self in a fortified camp, with

breastworks of fallen trees, so con-

structed as to embrace about twelve

acres of ground. In the center

of this he built a citadel of

entrenchments, in which he and his

chief officers resided for special

protection. This camp Dunmore

named Charlotte, according to most

authorities, in honor of the

handsome queen of George III., but more

likely the gallant gov-

ernor called the camp Charlotte after

his accomplished wife Char-

lotte, who was the daughter of the Earl

of Galloway. While

Governor Dunmore was thus engaged in the

heart of the

Ohio country Lewis was destined to

strike the decisive

blow

on the banks of the Kanawha.

On the ninth of

October Simon Girty and probably two

other messengers13

arrived at Lewis's camp bringing the

message from Lord

Dunmore which bade Lewis join his

lordship at the Indian towns

on the Pickaway plains. General Lewis,

deeply displeased at this

change in the campaign, arranged to

break camp that he might

set out the next morning in accordance

with his superior's orders.

He had with him about eleven hundred

men. His plans were

destined to be rudely forestalled, for

Cornstalk, coming rapidly

through the forest, had reached the

Ohio. The very night that

Girty brought Lewis the message from

Dunmore the Indian chief

ferried his men across the river on

rafts, a few miles above the

13 Captain John Stuart says one of the

governor's express messen-

gers to Lewis at Pt. Pleasant on the 9th

was McCullough.

Dunmore and his weaker force, after

throwing up a fortification

at the mouth of the Hockhocking, were

permitted to march undisturbed

to Sippo Creek, a tributary of the

Scioto (near the line between Ross

and Pickaway counties), and there, at

his fortified camp (Charlotte),

had received the submission of the

Shawnees. Their messengers, suing

for peace, had set out to meet him at

the Hockhocking, whilst Cornstalk

was executing his quick flanking stroke

at the other wing. In skill and

strategy, nothing superior to this had

occurred in Indian warfare.

-King's Ohio, p. 110.

180 Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

Kanawha, and by dawn was on the point of

hurling his whole

force of savage braves on the camp of

the slumbering Virginians.

The great Shawnee chief, Cornstalk, was

as wary and able as he

was brave. He was chief of the Shawnees,

and the head of the

Indian tribes of Ohio now united against

the whites. The Shaw-

nees were a very extensive and warlike

tribe. They were the

proudest and the richest of Indian

nations. They were the most

populous of any of the tribes in Ohio,

and they had, in the main,

ever been the fierce foe of the whites,

first against the French, then

with the French against the British, and

now goaded on by the

late depredations upon their land and

homes, and the recent massa-

cre of members of their own and fellow

tribes, they were aroused

to the greatest warlike ferocity14. Cornstalk's army numbered

about eleven hundred, practically the

same as that of Lewis, and

was composed of the flower of the

Shawnee, Delaware, Mingo,

Wyandot and Cayuga and minor tribes. The

great General Corn-

stalk, sachem of the Shawnee and king of

the northern confed-

eracy, though in chief command, was

aided by some of the most

famous and skilled warriors of his race.

Logan15, Elenipsico, son

of Cornstalk; Red Hawk, the Delaware

chief; Scrappathus, a

Mingo; Chiyawee, the Wyandot; Red Eagle,

Blue Jacket, Pack-

ishenoah, the Shawnee chief and father

of Tecumseh; his son

Cheesekau, elder brother of Tecumseh. In

no battle were there

ever so many bold and distinguished

braves. They were unaided

14 It was chiefly the Shawnees that cut

off the British army under

General Braddock, in the year 1755, only

nineteen years before our

battle (Pt. Pleasant), when the General

himself, and Sir Peter Hackett,

second in command, were both slain and a

mere remnant of the whole

army only escaped. It was they, too, who

defeated Major Grant and

his Scotch Highlanders at Fort Pitt in

1758, where the whole of the

troops were killed and taken prisoners.

After our battle they

defeated all the flower of the first

bold and intrepid settlers of Ken-

tucky at the Blue Licks. There fell

Colonel John Todd and Colonel Ste-

phen Trigg. "The whole of their men

were almost cut to pieces. After-

wards they defeated the United States

army over the Ohio commanded by

General Harmar. And lastly, they

defeated General Arthur St. Clair's

great army with prodigious

slaughter." - Narrative of Captain John Stuart

in the Virginia Historical Register,

Vol. V, p. 187.

15 Brantz Mayer, Cresap and Logan, p.

120, says Logan was not in

the battle.

The Dunmore War. 181

by French or English allies. Cornstalk

had the craft of his race

and the tact of a Napoleon. He saw his

enemy divided. Lewis

was at Kanawha; Dunmore on the Pickaway

Plains. If Lewis's

army could be surprised and overwhelmed,

the fate of Lord Dun-

more would be merely a question of days15.

So Cornstalk, "mighty

in battle and swift to carry out what he

had planned, led his long

file of warriors with noiseless speed,

through leagues of trackless

woodland to the banks of the Ohio."

Stealthily and unannounced

had Cornstalk arrived on the Virginia

side of the Ohio banks

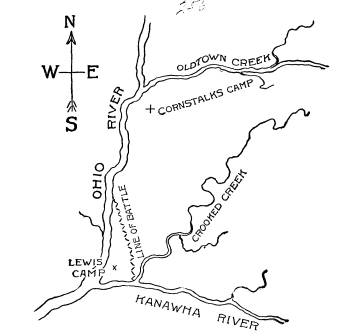

below

the mouth of Oldtown creek, which, parallel to the

Kanawha, pours into the Ohio some three

miles above the Kan-

awha point. Early on the morning of the

tenth, just as the sun

was peeping over the Virginia hills, two

soldiers (Robertson and

Hickman) left the camp and proceeded up

the Ohio river in quest

of game. When they had progressed about

two miles they un-

expectedly came in sight of a large

number of Indians, just rising

from their encampment, and who

discovering the two hunters,

fired upon them and killed one

(Hickman); the other escaped

unhurt and fled back to communicate the

intelligence "that he had

seen a body of the enemy covering four

acres of ground as closely

as they could stand by the side of each

other."

General Andrew Lewis was a well seasoned

soldier, alert and

self-possessed in every emergency and an

Irishman, quick-witted

and full of fight. He had been schooled

in Indian warfare for

twenty years. He was major of a Virginia

regiment at Brad-

dock's defeat. He had served with

Washington, who held him in

the highest esteem. General Lewis

"lighting a pipe," it is re-

ported, coolly ordered the troops in

battle array in the grey of

early dawn. Colonel Charles Lewis with

several companies was

directed to move toward the right in the

direction of Crooked

creek. Colonel Fleming, with other

companies, was instructed to

proceed to the left up the Ohio. Lewis's

force met the left of

Cornstalk's column about a half mile

from the Virginians' camp.

15 But the earl was not quite so rapid

in his movements, which

circumstance the eagle eye of old

Cornstalk, the general of the Indian

army, saw, and was determined to avail

himself of, foreseeing that it

would be much easier to destroy two

separate columns of an invading

army before than after their junction

and consolidation.--Kercheval,

p. 172.

|

182 Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

Fleming's command found the Indian right flank at a greater distance up the Ohio bank. Cornstalk's line of advance was more than a mile in front stretch, so drawn as to cut diagonally across the river point. By this tactic he had calculated upon pocketing General Lewis on the corner of the bluff between the Ohio and the Kanawha. The first shock of the onslaught was favorable to the foe. |

|

|

|

Colonel Charles Lewis made a gallant advance that was met by a furious response. The colonel was mortally wounded at almost the first fire of the enemy. He calmly marched back to the camp and died. His men, many of whom were killed, unable to with- stand the superior numbers of the Indians at this point, began to waver and fall back. Colonel Fleming was equally hard pressed in his encounter. He received two balls through his left arm and one through his breast, urging his men on to victorious action he re- tired to the camp, the main portion of his line giving way. |

The Dunmore War. 183

General Lewis now began to fortify his

position by felling

timber and forming a breastwork before

his camp. The fight was

soon general, and extended the full

front of the opposing armies.

What a strange and awful scene was

presented, one of mingled

picturesque beauty and ghastly carnage

on that October Monday

morning. A host of forest savages,

"a thousand painted and

plumed warriors, the pick of the young

men of the western tribes,

the most daring braves between the Ohio

and the great lakes"

their brown athletic and agile bodies

decked in the gay and rich

trappings of war; their raven black hair

tossed like netted manes in

the fray as with glowering eyes and

tense muscles they leaped

through the brush and stood face to face

with the white foe, the

latter rigid with firm resolution and

unwincing courage, fighters

typical of the frontier; a primitive

army equal in numbers to their

assailants, heroes in homespun, and

backwoodsmen in buckskin,

clothed in fringed leather hunting

shirts and coarse woollen leg-

gings of every color; they wore skin and

fur caps, and slung over

their shoulders were the straps of the

shot-bag and the strings of

the powder-horn. Each, like his barbaric

antagonist, carried his

flint-lock, his tomahawk and his

gleaming scalp-knife. For that

tragic tableau, quaint and dramatic,

nature never made a more

magnificent or peaceful setting. The two

lines grappled in deadly

conflict on the peak of land elevated by

precipitate banks high

above the Ohio, which swept by in

majestic width, joined by the

Kanawha that noiselessly crept its way

amid a forest and hill-

framed valley. The Ohio heights fretted

the sky to the west, and

the Virginia mountains in the near

eastern background were re-

splendent in the gorgeous drapery of

early autumn. It was a

landscape upon which nature had lavished

her most luxuriant

charms. It was a picture for the painter

and the poet rather than

the cold chronicler of history. No event

in American annals sur-

passes this in the mingling of natural

beauty and human violence.

The brutal savage and the implacable

Anglo-Saxon were to ex-

change lives by gory combat in the

irrepressible conflict between

their races.

It was nearly noon and the action was

"extremely hot," says

a participant. The Indians, who had

pushed within the right line

of the Virginians, were gradually forced

to give way; the dense

184 Ohio Arch. and His.

Society Publications.

underwood, many steep banks and fallen

timber favored their

gradual retreat. They were stubbornly

but slowly yielding their

ground, concealing their losses as best

they could by throwing

their dead in the Ohio, and carrying off

their wounded. The in-

cessant rattle of the rifles; the shouts

of the Virginians, and the

war whoops of the red men made the woods

resound with the

"blast of war." The groans of

the wounded and the moans of the

dying added sad cadence to the clash of

arms. At intervals, amid

the din, Cornstalk's stentorian voice

could be heard as in his native

tongue he shouted cheer and courage to

his faltering men, and

bade them "be strong, be

strong." But their desperate effort did

not avail, though exerted to the

utmost16. No more bitter or

fierce contest in Indian warfare is

recorded. The hostile lines

though a mile and a quarter in length

were so close together, being

at no point more than twenty yards

apart, that many of the com-

batants grappled in hand-to-hand

fighting, and tomahawked or

stabbed each other to death. The battle

was a succession of single

combats, each man sheltering himself

behind a stump or rock, or

tree-trunk. The superiority of the

backwoodsmen in the use of

rifles - they were dead shots, those

Virginia mountaineers -

was offset by the agility of the Indians

in the art of hiding and

dodging from harm. After noon the action

in a small degree

abated. The slow retreat of the Indians

gave them an advan-

tageous resting spot from whence it

appeared difficult to dislodge

them. They sustained an "equal

weight of action from wing to

wing." Seeing the unremitting

obstinacy of the foe, and fearing

the final result if they were not beaten

before night, General

Lewis, late in the afternoon, directed

Captains Shelby, Mathews

and Stuart with their companies to steal

their way under cover

of the thick and high growth of weeds

and bushes up the bank

16 "I could hear him (Cornstalk)

the whole day speaking very loud

to his men, and one of my company, who had been a prisoner, told

me what he was saying, encouraging the

Indians, telling them to 'Be

strong, be strong.'"--Stuart's

Narrative, p 187.

Cornstalk and Blue Jacket, the two

Indian captains, it is said,

performed prodigies of valor; but

finding at length all their efforts un-

availing, drew off their men in good

order, and with the determination

to fight no more, if peace could be

obtained upon reasonable terms.-

Kercheval, p. 172.

The Dunmore War. 185

of the Kanawha and along the edge of

Crooked creek until they

should get behind the flank of the

enemy, when they were to

emerge from their covert, move downward

towards the river

point, and attack the Indians in the

rear. The strategic manoeuver

thus planned was promptly and adroitly

executed and turned the

tide in favor of the colonial soldiers.

The Indians finding them-

selves suddenly and unexpectedly

encompassed between two

armies and believing that the force

appearing in the rear was the

reinforcement from Colonel Christian's

delayed troops, they were

discouraged and dismayed, and began to

give way. The appear-

ance of troops in the rear of the

Indians at once prevented the con-

tinuance of Cornstalk's scheme of

fighting, namely, that of alter-

nately attacking and retreating,

particularly with his center, thus

often exposing the advancing front of

the Virginians to the mercy

of the Indian flanks17. The

skirmishing continued during the

afternoon, the Indians though at bay

making a show at bravado.

But their strength was spent, and at the

close of the day under the

veil of darkness they noiselessly and

precipitately retreated across

the Ohio and started for the Scioto

towns18.

The battle of Point Pleasant was won.

"Such a battle with

the Indians, it is imagined, was never

heard of before," says the

writer of a letter printed in the

government reports. But the day

17 Those acquainted with Indian tactics

inform us that it is the

great point of his generalship to

preserve his flanks and overreach those

of his enemy. They continued, therefore,

contrary to their usual prac-

tice, to dispute the ground with the

pertinacity of veterans along the

whole line, retreating slowly from tree

to tree, till one o'clock p. m.,

when they reached a strong position.

Here both parties rested, within

rifle range of each other, and continued

a desultory fire along a front

of a mile and a quarter until after

sunset. - Chas. Whittlesey's Address

on Dunmore War (1850).

18 In the battle of the great Kanawha

the Indians, though hardly

defeated, were somewhat cowed by the

prowess of the frontiersmen,

which was now shown for the first time

on a considerable scale.-

Hosmer's Mississippi Valley, p. 71.

The Indians marched 80 miles through an

untrodden wilderness,

and on October 24 encamped on the banks

of the Congo (Pickaway

township, Pickaway county), near the

chief Shawnee village of Old

Chillicothe-now Westfall-on the Scioto, the headquarters of

the

Confederate tribes.-Howe's Ohio, Vol.

III, p. 64.

186 Ohio Arch. and His.

Society Publications.

was dearly bought. The Americans lost a

fifth of their number,

some seventy-five being killed or

fatally wounded, and one hun-

dred and forty-seven severely or

slightly wounded. Among the

slain were some of the bravest Virginian

officers, including Col-

onels Charles Lewis, Major John Field,

Captains Thomas Buford,

John Murray, James Ward, Samuel Wilson,

Robert McClanna-

han; and Lieutenants Allen, Goldsby and

Dillon. The Indian loss

was never definitely known19. They

cunningly carried off or con-

cealed most of their killed, and

secretly cared for their wounded.

They lost probably only half as many as

the whites. About forty

warriors were known to be killed

outright, or to have died of their

wounds. Of the number of wounded no

estimate could be made.

While the Virginians lost many officers,

strangely enough among

the Indians no chief of importance was

slain, except Packishenoah,

the Shawnee chief, and father of

Tecumseh20. No "official report"

of this battle was made, or if so,

probably not preserved. The

battle of Point Pleasant was the most

extensive, the most bitterly

contested, and fraught with the most

significance of any Indian

battle in American history21.

It was purely a frontier encounter.

The whites were colonial volunteers. The

red men, the choice of

their tribes, led by their greatest

warriors. The significance of

that battle was manyfold and

far-reaching. It was the last battle

fought by the colonists while subjects

to British rule. It was the

first battle of the Revolution. Whatever

the exact understanding

may have been between Lord Dunmore and

the royal authorities,

or between the Indians and the British

powers, or whether there

was any explicit understanding at all,

that battle represented the

19 "I believe it was never known

that so many Indians were ever

killed in any engagement with the white

people as fell by the army of

General Lewis at Point Pleasant." -Narrative of

Captain John Stuart.

It is fair to assume that the loss of

the Indians was not far short

of that sustained by the

whites.--Drake's Tecumseh, p. 33.

20 Drake's

Life of Tecumseh, p. 33.

21All

circumstances considered, this battle may be ranked among

the most memorable and well-contested

that has been fought on this

continent. The leaders on either side

were experienced and able, the

soldiers skillful and brave. The

victorious party, if either could be

so called, had as little to boast of as

the vanquished. It was alike credit-

able to the Anglo-Saxon and to the

aboriginal arms.- Drake's Tecumseh,

p. 33.

The Dunmore War. 187

opening bloodshed between the allies of

the British and the colon-

ial dependents. Had Cornstalk been the

conqueror of that contest

the whole course of American events

would doubtless have been

otherwise than history records. The

colonists would have been

stunned to inaction by the blow of

defeat, the fear of an extended

and horrible Indian warfare on their

western borders would have

deterred them from entering upon a

revolt against England's

power. At any rate the Ohio and

Mississippi valleys would most

certainly have remained the great

western province of the royal

power, and the United States be but a

strip east of the Alleghenies.

The victory of General Lewis destroyed

the danger in the west,

and gave nerve and courage to the

Virginians, who were the

strength and sinew of the Revolutionary

movement. England's

fate lay in the balance in the battle of

Point Pleasant, though no

British soldier participated therein.

America has no more historic

soil than the ground of the Kanawha and

Ohio point - reddened

that October day by the blood of savage

warriors and frontier

woodsmen22.

The Virginian victors buried their dead,

and left the bodies

of the vanquished to the decay of

uncovered graves. General

Lewis, leaving his sick and wounded in

the camp at the Point,

protected by rude breastworks, and with

an adequate guard,

crossed the Ohio (October 18) and began

his march by way of the

Salt Licks and Jackson to join Dunmore

on the Pickaway Plains.

When but a few miles from Dunmore's camp

Lewis was met by a

messenger from the earl informing him

that a treaty of peace was

22 Very

many survivors of the battle of Point Pleasant became

famous soldiers in the American

Revolution and distinguished civilians

in the United States Nation. We note a

few by illustration: General

Isaac Shelby, Governor of Kentucky, aid

to General Harrison in War of

1812; Colonel William Fleming, Acting

Governor of Virginia; General

Andrew Moore, Senator from Virginia;

Colonel John Steele, Com-

mander of Washington's lifeguard in

1780; General George Matthews,

Governor of Georgia and Senator from

that state; and so through a long

list of distinguished officials and

heroes who were either officers or pri-

vates in the battle of Point Pleasant.

Hale, in his Trans-Alleghany Pio-

neers, devotes a chapter to this

subject, entitled, "Point Pleasant (battle)

as a Developing Military High

School." He gives a long list with brief

biographies of those who fought in that

contest, and were subsequently

conspicuous for distinguished services

to their country. - E. 0. R.

|

188 Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

being negotiated with the Indians and ordering him (Lewis) to return immediately to the mouth of the Big Kanawha. Lewis's men were flushed with success, and exasperated at their losses in the late battle and eager for revenge upon the red men, and the opportunity to crush their power and destroy their homes. Lewis |

|

|

|

shared the feelings of his soldiers and refused to obey the order of Dunmore. He continued to advance until when on the east bank of the Congo near its juncture with the Sippo, he was met by the earl himself and the Indian chief White Eyes23. The earl

23"Captain Arbuckle was our guide. When we came to the prairie on Killicanic Creek we saw the smoke of a small Indian town, which was deserted and set on fire upon our approach. Here we met an express from the Governor's camp, who had arrived near the nation and pro- |

The Dunmore War. 189

explained the situation to Lewis,

complimented his generalship,

and the bravery of his men, stating

there was no further need of

advancement by his (Lewis's) division of

the army. General

Lewis, recrossing the Congo, encamped

for the day, and then re-

luctantly commenced his return march to

the Ohio, proceeding

posed peace to the Indians. Some of the

chiefs with the Grenadier

Squaw (sister of Cornstalk) on the

return of the Indians after their

defeat, had repaired to the Governor's

army to solicit terms of peace

for the Indians, which I apprehend they

had no doubt of obtaining. The

Governor promised them the war should be

no further prosecuted, and

that he would stop the march of Lewis's

army before any more hostili-

ties should be committed upon them.

However, the Indians, finding we

were rapidly approaching, began to

suspect that the Governor did not

possess the power of stopping us, whom

they designated by the name

of the Big Knife men; the Governor,

therefore, with White Fish (Capt.

Stuart must mean White Eyes-E. O. R.)

warrior set off and met us

at Killicanic Creek and there General

Lewis received his orders to return

with his army, as he (Dunmore) had

proposed terms of peace with the

Indians, which he assured should be

accomplished."-Narrative of Capt.

John Stuart, as printed in Virginia

Historical Register, Vol. V, p. 189.

The two divisions were now within a few

miles of each other; for

Lewis, disregarding the commands of his

lordship, continued to advance

until the Indians, fearful of the

destruction of their towns and crops

by the enraged men under his command,

again applied to Dunmore,

who went in person to Lewis's command,

and persuaded him to halt

his men and retire. To this, with great

reluctance, he finally consented,

as it was an abandonment of the sole

object of the campaign-the de-

struction of the crops and towns of the

Indians.-Hildreth, Pioneer

History, p. 89.

The Ohio campaign of Dunmore brought

upon him much angry

criticism. Many of the border men felt

as did Lewis, who was for

carrying out the original revengeful

program, regardless of Indian sur-

render or repentance. Dunmore's official

conduct in connection with the

colonial revolt made it easy in

the.earlier days to misconstrue his mo-

tives under circumstances calling for no

such suspicion. That he had

no other than humane and honorable

designs in accepting the Indians'

plea for peace, no longer appears

probable.-Black's Story of Ohio,

footnote under p. 70.

Before Dunmore reached the vicinity of

the Indian towns he was

met by a flag of truce and a deputy from

the Indians, requesting for

the chiefs an interpreter with whom they

could communicate. He moved

on to Camp Charlotte. Lewis marched on

and encamped on the west

side of the Congo Creek, about a mile

and a half below where it enters

into the Sippo. Dunmore, on the approach

of Lewis and his army, sent

190 Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

by the route he had come, to Point

Pleasant. Meanwhile Corn-

stalk and his crestfallen warriors had

reached the Pickaway

Plains. The spirit of the Indians had

been broken by their defeat;

but the stern old chief, their

commander, Cornstalk, remained

with unshaken heart. He was still

prepared to fight to the bitter

word to him to return, as he would

settle the result with the Indians.

Lewis refused to obey this order.

Dunmore then went in person to

enforce his orders. It is said Dunmore

drew his sword upon Colonel

Lewis. -Howe's Ohio Collections. This

incident is another of the

alleged suspicious movements of Dunmore,

it even being charged that

Dunmore wanted to keep the armies

divided that they might fall a prey

to the Indian attacks if renewed. Again,

that he did not wish to over-

awe the Indians by the presence of the

united forces, as he wished to

conciliate the Indians and incur their

favor with a view to their friend-

ship in the coming revolution.- E. O. R.

Lewis encamped that night on the west

side of Congo Creek, two

miles above its mouth, and five and a

quarter miles from old Chillicothe,

with the Indian town half way between.

The Shawnees were now

greatly alarmed and angered, and Dunmore

himself, accompanied by

the Delaware chief, White Eyes, a

trader, John Gibson, and fifty vol-

unteers, rode over in hot haste that

evening to stop Lewis and repri-

mand him. His lordship was mollified by

Lewis's explanations, but

the latter's men, and indeed Dunmore's,

were furious over being stopped

when within sight of their hated quarry;

and tradition has it that it

was necessary to treble the guards

during the night to prevent Dunmore

and White Eyes from being killed. The

following morning (the 25th)

his lordship met and courteously thanked

Lewis's men for their valiant

service; but said, that now the Shawnese

had acceded to his wishes,

the further presence of the southern division might

engender bad blood.

Thus dismissed, Lewis led his army back

to Point Pleasant.-Thwaite's

Note in Border Warfare, pp. 176-8,

quoted by Safford in Ohio Arch.

Hist. Pub., Vol. VII, p. 353.

That Earl Dunmore, the last royal

Governor of Virginia, rendered

himself excessively unpopular by

ordering Lewis back is certain, and

it hastened his final abandonment of the

colony, when he fled to a

British fleet for protection from his

not very loving people. Whether

his object, while at Camp Charlotte, was

to make the Indians friendly

to the British crown, and unfriendly to

the colonists, in case of war

between the two countries, which so soon

followed this campaign, we

can never know with absolute certainty.

We are well aware, though,

that General George Washington always

did believe that Dunmore's

object was to engage the Indians to take

up the tomahawk against the

colonists as soon as war existed between

the colonies and England. So

believed Chief Justice Marshall, as we

know from his own lips.-

Atwater's History of Ohio. p. 118.

The Dunmore War. 191

end. He summoned a council over the

situation, and in an elo-

quent address strove to goad on the

braves to another campaign.

They listened in sullen silence.

Finally, finding himself unable

to stir his braves to further battle, he

struck his tomahawk into

the war post and peremptorily declared,

"I will go and make

peace." He was as good as his word.

With his retinue of fellow

chiefs, some eight in number, Cornstalk

proceeded to Dunmore's

quarters within the entrenchments of

Camp Charlotte. Here he

made a prolonged and passionate plea for

his people, reciting the

wrongs inflicted by the whites, and the

rights denied the red men24.

Various parleyings ensued, the net

conclusion of which was, the

Indians agreed to give up all white

prisoners and stolen horses in

their possession, cease from further

hostilities, and molestation

of travelers down the Ohio and

"surrender all claim to the lands

south of the Ohio25."

24 The

conference was commenced by Cornstalk in a long, bold,

and spirited speech, in which the whites

were charged with being the

authors of the war by their aggressions

on the Indians at Captina and

Yellow Creeks-Drake, Tecumseh, p. 35.

Cornstalk was a truly great man. Colonel

Wilson, who was pres-

ent at the interview between the chief

and Lord Dunmore, thus speaks

of the chieftain's bearing on the

occasion: "When he arose he was

in nowise confused or daunted, but spoke

in a distinct and audible

voice, without stammering or repetition,

and with peculiar emphasis.

His looks while addressing Dunmore were

truly grand and majestic, yet

graceful and attractive. I have heard

the best orators in Virginia--

Patrick Henry and Richard Lee--but never

have I heard one whose

powers of delivery surpassed those of

Cornstalk." - Stone's Life of Joseph

Brant, Vol. I, p. 45.

25

What the exact terms of that treaty were is not now fully known.

No copy of the treaty can be

found.-Drake's Tecumseh, p. 35. Both

Burk and Campbell, in their respective

Histories of Virginia, say peace

was secured on condition that the lands

"on this side of the Ohio"-

meaning the south side-"should be

forever ceded to the whites," etc.

Butler (History of Kentucky), quoting

the above terms, remarks (p. 10),

"Such a treaty appears at this day

(1834) to be utterly beyond the ad-

vantages which could have been claimed

from Dunmore's expedition."

Doddridge, in his notes, p. 237, says:

"On our part we obtained at the

treaty a cessation of hostilities and a

surrender of prisoners, and nothing

more." Whatever the terms of the

treaty may have been, the results

of the Dunmore war were most important.

"It kept the northwestern

tribes quiet for the first two years of

the Revolutionary struggle; and

192 Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

This agreement whatever its explicit

text, was another step

in the westward progress of the white

invader. Cornstalk haught-

ily and disdainfully acceded to the

terms of the whites. But there

was one distinguished chief who was not

at that council, and who

had refused to be present. It was Logan.

He declared that he

was a "warrior, not a councillor,

and he would not come." Logan

was a splendid specimen of his race. He

was chief of the Mingo

tribe and his father, whom he succeeded,

had been chief of the

Cayugas. Up to the time of the Dunmore

war Logan had been

the friend of the white man. He took no

part in the French and

Indian war, except that of peacemaker.

But when in the border

troubles between the Indians and whites

in the spring of 1774,

Logan's relatives were massacred at the

Yellow creek, as he sup-

posed, by Cresap and party, Logan's rage

became terrible. His

character changed into all the

revengeful and distorted hate and

unrelenting ferocity of which the Indian

nature is capable. From

that moment for the rest of his life he

was the inveterate and

implacable foe of the white. He would

not attend the peace coun-

cil with Cornstalk. His influence with

the Indians made it impor-

tant that his concurrence be secured.

Lord Dunmore, desiring

his presence, sent John Gibson,

afterwards general, a frontier

veteran and one familiar with the Indian

language, to urge the

attendance of Logan. Taking Gibson

aside, under the shade of a

neighboring tree, Logan suddenly

addressed him that famous

speech which immortalized the chief and

furnished a model of

oratory for thousands of American school

boys26. The speech is

popularly supposed to have been

delivered in Logan's native In-

above all, it rendered possible the

settlement of Kentucky, and therefore

the winning of the West. Had it not been

for Lord Dunmore's war

it is more than likely that when the

colonies achieved their freedom they

would have found their western boundary

fixed at the Allegheny Moun-

tains.-Roosevelt, Winning of the West,

Part II, p. 33.

26 "Gibson found Logan some miles

off at a hut with several Indians,

with whom he (Logan) talked and drank a

while, and then touching

Gibson's coat, stealthily beckoned him

out of the house, led him to a

solitary thicket, when, sitting on a

log, he burst into tears and uttered

some sentences of impassioned eloquence,

which Gibson immediately

committed to paper. As soon as the envoy

(Gibson) had reduced the

message to writing, it was read aloud in

the council and heard by the

soldiers."-Brantz Mayer's Cresap

and Logan, p. 122.

The Dunmore War. 193

dian tongue, and have been literally

translated and written down

in English by John Gibson, and so

delivered to Lord Dunmore,

who read it in open council to the

Virginian army. However it

may have been that speech is one of the

great Indian classics. It

has a wierd, pathetic strain, and is a

poetic recital with a rhetorical

charm not unlike the Greek chorus.

"I appeal to any white man to say

if ever he entered Logan's

cabin hungry and he gave him not meat;

if ever he came cold and

naked and he clothed him not? During the

course of the last long

and bloody war, Logan remained idle in

his camp, an advocate for

There is much dispute, of course, about

the details of this historic

incident. Some authorities assert Logan

spoke fluently in English, which

Gibson either wrote down on the spot or

subsequently at Dunmore's camp.

Again, it is related Logan could not

speak English and delivered his "say"

to Gibson in his native tongue, and that

Gibson, who understood the

Indian language, either took it down in

translation or put it into English

after returning to the camp of Dunmore.

Jefferson's report of the speech

in his Virginia notes created considerable

controversy and led to the

affidavit of John Gibson, which we give

in the appendix. This affidavit

does not show what language Logan used.

Even if he could speak

English, which is most probable, it is

doubtful if he used such rhetoric

as the "report" gives him. The

English phraseology of the speech as

read to Dunmore's army is most likely

partially due to Gibson, the senti-

ment and thought without question are

Logan's. - E. O. R. On this

question see American Pioneer for

January, 1842, and Jefferson's Notes

on Virginia, Jefferson's Works, Vol.

VIII, p. 309.

"While negotiations were going

forward, the Mingo chief, Logan,

held himself aloof. 'Two or three days

before the treaty,' says an

eye witness, 'when I was on the

outguard, Simon Girty, who was

passing by, stopped with me and

conversed. He said he was going after

Logan, but he did not like his business,

for he was a surly fellow. He,

however, proceeded on, and I saw him

return on the day of the treaty,

and Logan was not with him. At this time

a circle was formed and

the treaty begun. I saw John Gibson, on

Girty's arrival, get up and

go out of the circle and talk with

Girty, after which he (Gibson) went

into a tent, and soon after returning

into the circle, drew out of his

pocket a piece of clean, new paper, on

which was written, in his own

handwriting, a speech for and in the

name of Logan.' This was the

famous 'speech' about which there has

been so much controversy. It

is now well established that the version

as first printed was substantially

the word of Logan, but it is equally

certain that he (Logan), in attrib-

uting the murder of his relatives to

Colonel Cresap, was mistaken. Girty

from recollection, translated the

'speech' to Gibson, and the latter put

13-Vol. XI.

194 Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.