Ohio History Journal

OHIO

and the

PANAMA CANAL

by CHARLES D. AMERINGER

"Uncle Sam digging under the

influence of the Sons of Ohio at the right

place." So ran a toast proposed at

the twenty-second annual banquet of

the Cincinnati Commercial Club at the

Queen City Club on November 13,

1902. The reference was to the role

Ohioans had played in the decision

of the United States to construct an

interoceanic canal in Panama, and

the man who offered the toast was in a

position to know whereof he spoke.

He was Philippe Bunau-Varilla, a French

engineer who had served the

De Lesseps enterprise in Panama in the

1880's and, when the French ven-

ture failed, had kept faith with the

project and eventually turned to the

United States to rescue it. His

speech-making and lobbying activities in

the United States in 1901 and 1902 were

legend.1 And from that night he

would go on to participate in the Panama

revolution of 1903, become

Panama's first minister to the United

States, and negotiate the treaty

under which the United States secured

the right to construct the Panama

Canal.

Bunau-Varilla's tribute was not limited

to Senator Mark Hanna, who,

everyone knew, had successfully led the

fight for the selection of the

Panama route in the United States Senate

the preceding June, but included

a large number of Ohioans who played

important, though less publicized,

parts in Panama's victory. Moreover,

this was not Bunau-Varilla's first

visit to Cincinnati; he had been there

in January 1901, when, at the invi-

tation of three Cincinnati businessmen,

he launched his crusade in behalf

of the Panama route. It was these

Cincinnatians and the many Ohioans

whom he met between January and April

1901, to whom he directed his

toast, and they included the following:

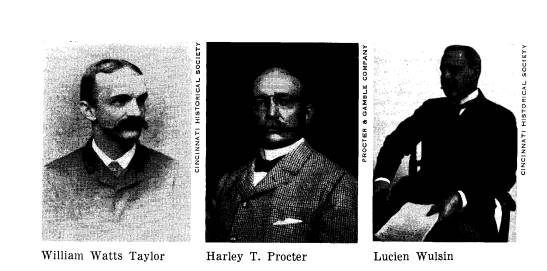

Edward Goepper, Cincinnati in-

dustrialist; Harley T. Procter, of

Procter and Gamble, Cincinnati; Jacob

G. Schmidlapp, president of Cincinnati's

Union Savings Bank and Trust

Company; William Watts Taylor, president

of the Rookwood Pottery

Company of Cincinnati; William

Worthington, Cincinnati attorney; Lucien

Wulsin, president of the Baldwin Piano

Company of Cincinnati and Chi-

cago; Major William Henry Bixby, A. O.

Elzner, and G. W. Kittredge,

engineers and members of the Engineers

Club of Cincinnati; Senator

NOTES ARE ON PAGES 69-70

4 OHIO HISTORY

Hanna; Myron T. Herrick, Cleveland

businessman and "member of Sena-

tor Hanna's machine,"2 who became

governor of Ohio (1903) and United

States ambassador to France (1912);

James Parmelee, president of the

National Carbon Company and the

Cleveland Electric Illuminating Com-

pany; and Francis B. Loomis, career

diplomat from Springfield and Cin-

cinnati, who became United States

minister to Portugal (1902) and as-

sistant secretary of state (1903).

Bunau-Varilla's relationship with these

men and the nature of their influence in

the struggle for the Panama

Canal may be found among the

correspondence, manuscripts, and papers

of Philippe Bunau-Varilla deposited in

the Library of Congress in

Washington, D. C.3

These papers reveal how Bunau-Varilla

met Procter, Taylor, and Wul-

sin in Paris in the summer of 1900 and

how the Cincinnatians came to

invite him to the United States the

following winter. There were many

Americans in Paris in 1900, for that was

the year of the famed Inter-

national Exposition, where visitors

marveled at the exhibits and delighted

in dining at Parisian restaurants.

According to Wulsin, on one occasion

Procter and Taylor were taken to a new

restaurant by Lieutenant Com-

mander Asher Baker, an American naval

officer attached to the United

States Commission to the Paris

Exposition, and there they met Bunau-

Varilla.4 Wulsin described

the meeting as accidental, and there is no

reason to doubt his sincerity, but Baker

had acted as Bunau-Varilla's

paid lobbyist in the United States

during the congressional session of

1898-99,5 and it was possible that

Bunau-Varilla and Baker had set up

the meeting. Nevertheless, Bunau-Varilla

impressed the Cincinnatians

with his knowledge of Panama. They dined

together again the next day,

and several days later they met for

lunch, where, at Taylor's invitation,

Wulsin was also present. Everyone in

America was convinced that the

proposed isthmian canal should go

through Nicaragua, so when Bunau-

Varilla pointed out the disadvantages

and dangers of the Nicaragua route

and extolled the superiority of Panama,

Wulsin asked Bunau-Varilla if

he would come to the United States and

present his arguments, in the

event arrangements could be made.

Bunau-Varilla said he would, but

nothing specific was settled, and

shortly afterwards the Americans left

for home. Bunau-Varilla heard no more

about the matter, and he later

stated he had forgotten about it until

he received an invitation on Decem-

ber 11, 1900, to come to Cincinnati and

address the Commercial Club.6

Bunau-Varilla accepted the invitation on

December 12, but owing to

previous engagements he was unable to

leave before early January.7

Despite the apparent suddenness with

which the invitation was made,

Bunau-Varilla had been contemplating a

trip to the United States in

advocacy of the Panama scheme. Several

other American friends8 had

been urging him to come, because the

time for a decision on the isthmian

canal was approaching. For several years

the representatives of the

French Panama Canal Company--with whom

Bunau-Varilla had no con-

nection--had employed tactics of delay,

that is, they exploited the ob-

|

stacles to any canal construction (namely, the Clayton-Bulwer treaty with Great Britain, which obligated the United States not to act alone in such a venture, and the partisan rivalry in congress over sponsorship of the Nicaragua Canal bill). In order to block action on Nicaragua, they forced the appointment of an isthmian canal commission in March 1899 to under- take surveys of all likely canal routes. However, on November 30, 1900, the commission issued a preliminary report which recommended the Nicaragua route, and negotiations for superseding the Clayton-Bulwer treaty seemed to be proceeding satisfactorily. If Panama was to win, the time had come for a positive promotion of the Panama route. William Watts Taylor seemed to be aware of Bunau-Varilla's possible plans. On December 13, 1900, he expressed his pleasure that Bunau-Varilla was coming to Cincinnati and cabled the following:

We should scarcely have been bold enough to suggest your coming for this special purpose and we still assume, as our cablegram stated, that you would have visited America at any rate in view of the recent report of the Canal Commission and the early discussion of the Nica- ragua Canal Bill in Congress. Otherwise we should feel that we were asking too much of you on the ground of personal friendship.9

The evidence is also strong that Bunau-Varilla paid for his own expenses during his 1901 visit to the United States.10 However, the invitation to come to Cincinnati presented Bunau-Varilla with an excellent opportunity. On January 13, 1901, Bunau-Varilla arrived in New York, where he was met by Harley T. Procter, who came to escort him to Cincinnati. Bunau-Varilla learned that plans were made for him to speak before the Cincinnati Commercial Club on January 16, and before the Commercial Club of Boston on January 25. Commander Baker was also at the dock and he told Bunau-Varilla that arrangements were being made with a Chicago agricultural machinery manufacturer, James Deering, for a speaking engagement in Chicago.11 In Cincinnati the Frenchman was touched by his welcome and he spoke to an assemblage of the city's first citizens in a hall decorated with American and French flags.12 It was his |

6 OHIO HISTORY

first public address in English,13 and

he spoke on "The Comparative Value

of the Nicaragua and Panama Routes of

the Isthmian Canal." While his

comparison of the relative merits of the

two routes concerned technical

features, he excited general interest by

pointing out the danger of vol-

canoes at Nicaragua, and Taylor

afterwards assured him the address "was

in every way a success."14

The people of Cincinnati, Taylor wrote, "felt

at once as we did on our first meeting

in Paris not only your grasp of the

subject but the intensity of conviction

which inspired all your utterance."15

The success of the talk may be measured

by the demand that Bunau-

Varilla repeat it the next day before

the Engineers Club of Cincinnati,

and the intensification of efforts on

the part of Bunau-Varilla's Cincinnati

sponsors to secure additional hearings

for him.

At a small luncheon on January 17, the

discussion concerned the means

by which Bunau-Varilla might take his

case to President William Mc-

Kinley, and it was suggested that it

might be achieved through "the

President's friends in

Cleveland."16 Jacob Schmidlapp telephoned Myron

T. Herrick in Cleveland, and it was

arranged for Bunau-Varilla to talk

to an informal group at Cleveland's

Union League Club the following

day.17 After a twelve-hour train ride,

Bunau-Varilla arrived in Cleveland

on January 18, where he apparently

converted Herrick and began with

him a long and warm friendship.18

Senator Hanna was not in Cleveland

at the time, but Herrick took steps to

arrange an interview.19 Wulsin and

Taylor also took measures to have

Bunau-Varilla meet Hanna.20 But be-

fore Bunau-Varilla went to Washington to

see Hanna, he renewed his

lecture tour.

During the next several weeks

Bunau-Varilla spoke in Boston, Chicago,

Princeton, and New York. His talk in

Boston on January 25, 1901, had

been arranged through William

Worthington of Cincinnati. He was re-

ceived politely there, but apparently

did not excite the kind of interest

he had in Ohio. In Chicago, James

Deering was his host, and Bunau-Varilla

delivered a public lecture under the auspices

of the National Business

League on February 1. Baker accompanied

the Frenchman to Chicago,

where he met Marshall Field, Robert

Lincoln, and Cyrus McCormick.21

An effort to schedule an address before

the Chicago Commercial Club in

mid-February failed, but McCormick was

instrumental in enabling Bunau-

Varilla to speak at Princeton University

on February 28.22 Bunau-Varilla

had difficulty in obtaining a hearing

before the Chamber of Commerce

of the State of New York, but it was

finally arranged through his friend

and attorney, former New York state

senator Frank Pavey, and Gustav

Schwab, the representative in America of

the North German Lloyd Steam-

ship Company.23 Throughout these weeks

Bunau-Varilla was in touch with

his Cincinnati friends, and when he

undertook to publish a pamphlet,

Nicaragua or Panama, which was the substance of his lectures in Amer-

ica, Taylor of the Commercial Club and

A. 0. Elzner of the Engineers

Club supplied him with membership lists

in order to distribute the pam-

phlet. Elzner stated that

Bunau-Varilla's paper was the ablest argument

OHIO AND THE PANAMA CANAL 7

he had seen,24 but when Taylor praised

it, Bunau-Varilla protested, "If

the light is at last thrown on this

question, I may perhaps be credited

for the gas that gave light, but you

with Mr. Proctor [sic] and Mr. Wulsin

have given me the match to burn it, and

it is quite as important as the gas

to have light."25 On March 17,

Taylor informed Bunau-Varilla that the

time looked right for a visit to

Washington to confer with Hanna.26

Bunau-Varilla went to Washington on

March 19, but after waiting six

days to see Hanna, he returned to New

York, where he "bumped into"

the Ohio senator. In Washington on March

20, Bunau-Varilla wrote to

Hanna and requested an interview. He

mentioned his Ohio friends, and

told Hanna, "I came to this country

to expose publicly what I think is the

technical and scientific truth about the

transisthmian canal question, in-

dependently of any material interest

whatever."27 This note brought no

reply from Hanna, but if Bunau-Varilla

was disappointed he did not

waste his time. Friends in Washington

invited him to dine at the Metro-

politan and Cosmos clubs, and

Bunau-Varilla secured the membership lists

to use in distributing his pamphlet. He

also dined with Colonel Oswald

Ernst and George Morison, members of the

isthmian canal commission

and corresponded with Deering in

Chicago, who agreed to mail copies

of his pamphlet to the members of the

National Business League.28 Ar-

rangements were also made for

Bunau-Varilla to deliver his lecture to

the Philadelphia Bourse on April 3.

Delays in additional printings of the

pamphlet Nicaragua or Panama caused

Bunau-Varilla to return to New

York on March 26, but the following day

he received a note from the

banker Isaac Seligman, who told him

Hanna was in New York and was

staying at his same hotel, the Waldorf.

Seligman stated, "Senator Hanna

came in to see me to-day, and I spoke to

him about you. He will be glad

to see you at the hotel (Waldorf) any

time at your convenience. I believe

that he leaves tomorrow night for

Washington."29 That same evening, late,

Bunau-Varilla went down to the Waldorf

lobby for "a breath of air," and

came upon a group of returning

theater-goers. Breaking away from the

party to greet Bunau-Varilla was Myron

T. Herrick, who immediately in-

troduced him to another member of the

group, Senator Mark Hanna.30

Thus, capping months of effort to bring

the engineer and the senator to-

gether, another "chance

meeting" brought the desired result. Hanna

apologized for his failure to answer

Bunau-Varilla's letter and explained

that unexpected business had taken him

from Washington, but he immedi-

ately invited Bunau-Varilla to call upon

him.

After speaking in Philadelphia on April

3, Bunau-Varilla went to

Washington, where he met with Hanna and

President McKinley. Bunau-

Varilla regarded his interview with

Hanna as the turning point in the

Panama struggle,31 and Taylor reported

that he believed Bunau-Varilla

had made "a most favorable

impression upon Senator Hanna."32 There is

evidence, however, that Hanna was

leaning towards the Panama solution

before he met Bunau-Varilla.33 While

there is some question about who

was responsible for Hanna's conversion

to Panama, the fact is that Hanna

8 OHIO HISTORY

was the key figure in Panama's adoption

by the senate the following year

and, in bringing this about, he relied

greatly upon Bunau-Varilla.34 On

April 7, Bunau-Varilla had a five-minute

audience with President Mc-

Kinley, but Bunau-Varilla considered

this sufficient, since he felt no need

to repeat the lengthy argument he had

presented to Hanna, the president's

friend and advisor.35 On April 9, Bunau-Varilla

returned to New York

and made preparations to sail for France

two days later. In summarizing

his lecture tour, Bunau-Varilla cabled

Ferdinand de Lesseps' son, Charles,

in Paris, "Nicaragua est

mort."36 This was an optimistic appraisal, but

certainly Bunau-Varilla's visit to the

United States initiated by the Cin-

cinnati Commercial Club had gone a long

way towards reversing the

popular feeling that the canal would be

built at Nicaragua. At almost

every milestone in the future struggle

for Panama, Bunau-Varilla would

pause and pay tribute to his friends in

Ohio. Perhaps this phase of the

campaign for Panama was best summed up

by Francis B. Loomis in an

address before the Naval War College in

Newport, Rhode Island, on Sep-

tember 12, 1901, in which he said there

had been "within the last year a

very considerable display of interest in

the Panama route," and much

of it could be attributed to

Bunau-Varilla's addresses before the Commer-

cial Club and the Engineers Club in Cincinnati.37

Things had gone well for Bunau-Varilla,

but why had Ohio's leaders

been so helpful to him? There is not a

shred of evidence that any of them

had a vested interest in the Panama

route, nor did their names come up

later when it was charged that the

Panama Canal affair involved a stock

speculation.38 It appears that they

acted out of a desire to see the United

States build the canal at the best site

and that they were sincerely capti-

vated by the personality of Philippe

Bunau-Varilla. Lucien Wulsin ex-

pressed his feelings to Bunau-Varilla in

February 1902 as follows:

Let me again assure you of the great

interest with which I have

followed your practical yet high-minded

and patriotic course in the

Panama matter. From my first meeting

with you I was convinced

of the soundness and honesty of your

views. I could therefore do no

less than I have done from my own

standpoint as an American.39

And Taylor told Bunau-Varilla, "I

love a man who loves a great cause

--to whom it is in a way a religion, to

which he consecrates without stint

all his devotion and all his finest

powers."40 The numerous letters between

Herrick and Bunau-Varilla reveal their

cordial friendship, and Bunau-

Varilla stated to Herrick's wife that he

was able to secure support for

Panama because Herrick gave him

"the credit of his friendship and of his

confidence."41 There was, however,

one slight shadow that fell across this

picture.

Philippe Bunau-Varilla, through his

brother Maurice, a Paris news-

paper publisher, seemed to have some

influence in the awarding of prizes

and decorations connected with the Paris

Exposition. As a mark of re-

OHIO AND THE PANAMA CANAL 9

spect and appreciation for their

participation in the exposition many

Americans were decorated by the French

government and named to the

Legion of Honor. Herrick, Taylor, and

Wulsin were appointed to the rank

of chevalier in the Legion of Honor, and

Wulsin's Baldwin pianos re-

ceived the "Gran Prix" award

at the fair. There is no evidence that Bunau-

Varilla had anything to do with these honors,

but with reference to awards

received by Chicago manufacturer James

Deering, Bunau-Varilla definitely

had an influential part. With

Bunau-Varilla's help, Deering was decorated

a knight in the Legion of Honor,42 and

his firm received the "Merite

Agricole."43 However, when Deering

wanted Bunau-Varilla to help him

prevent his competitors from obtaining

similar decorations, Bunau-Varilla

indicated that there were limits to what

he was willing to do in this re-

gard. He told Deering that he had been

able to secure the Merite Agri-

cole through his brother, but that his

brother disliked using his "great

political influence" for private

aims and that he had made an exception

because of the excellent reputation of

the Deering firm. Bunau-Varilla

stated it would be useless to convey to

his brother Deering's latest re-

quest, and he concluded as follows:

I appreciated dear friend as a

demonstration of your friendship

to me to make known to me what would

correspond to your desire

and I feel very worried to be incapable

of being of any service to

you, but I hope you will appreciate as

another proof of the friendly

confidence I have in your judgement to

avoid any of these polite lies

people use with strangers to conceal

their unwillingness or their in-

ability of doing what they are asked

for.44

This letter revealed a frank honesty on

the part of Bunau-Varilla, and

Deering was gracious in his response.

"I understand perfectly," Deering

wired, "and if possible cherish you

more than before. Don't fail to come

to Chicago again if any way

possible."45 This was probably an isolated

affair, but it has been cited as a

demonstration of the possible practical

value of Bunau-Varilla's friendship. There

was no further mention of

these matters after the spring of 1901.

Bunau-Varilla returned to the United

States in November 1901 in order

to participate in the decisive

congressional session of 1901-2. He now

came as a lobbyist rather than as a

lecturer. For over six months, in alli-

ance with William Nelson Cromwell, the

New York attorney who was

representing the French Panama Canal

Company, Bunau-Varilla worked

closely with Mark Hanna in the senate.

This effort, climaxed by Hanna's

dramatic speech on the senate floor on

June 5 and 6, 1902, resulted in the

adoption of the Panama route.

Bunau-Varilla did not visit Cincinnati

during this time, although Wulsin had

invited him to come.46 However,

Wulsin continued his efforts in

Bunau-Varilla's behalf and to this end he

wrote to Ohio congressman Jacob H.

Bromwell in February 1902.47 Bunau-

Varilla met several of his Ohio friends

on March 1, when, with Hanna,

10 OHIO HISTORY

he attended the sixteenth annual banquet

of the Ohio Society of New

York at the Waldorf-Astoria. During

parts of April and May, Bunau-

Varilla did some sightseeing with his

brother Maurice, who had come

to America for the first time, and one

of the places they visited was Cleve-

land. In Cleveland the brothers were the

guests of Myron T. Herrick,48

and there they also met Liberty Emery Holden,

president of the Cleveland

Plain Dealer, who confessed that he was "a staunch friend of the

Panama

route."49 In late May and June

1902, Bunau-Varilla returned to the con-

gressional battleground and, as one of

his tasks, he revised his pamphlet

Nicaragua or Panama into a shorter version with graphs and drawings.

On June 14, Bunau-Varilla wrote to

Herrick and asked him to forward

the new pamphlet to President Theodore

Roosevelt, because "the only

man who can do it is yourself. . . . You

are the only man whose recom-

mendation will be sufficient to obtain

that the President reads it."50 It

was at this point also that

Bunau-Varilla distributed to each senator his

famous Nicaraguan postage stamp, which

showed a Nicaraguan volcano

in eruption. When the vote finally came

in favor of Panama, Bunau-

Varilla's first step was to wire Wulsin

and Taylor and to state, "I shall

remember forever that the triumph of

Panama is due to the invitation of

the Commercial Club of Cincinnati . . .

which allowed me to begin in your

country the campaign for the

truth."51 Not too many months later, Bunau-

Varilla expressed his feelings in

person, when, in November 1902, he

addressed and toasted the Cincinnati

Commercial Club.

The adoption of the Panama route by the

American congress in June

1902, did not end the Panama affair, and

Bunau-Varilla was destined to

play another and more spectacular role

in the history of the Panama Canal.

In these events an Ohioan also had a key

part. The construction of the

Panama Canal was contingent upon the

satisfactory negotiation of a

treaty with Colombia, the sovereign over

the Panama route. This proved

a futile task, and leading citizens on

the Isthmus of Panama decided that

they would secede from Colombia before

they would risk losing the canal.

In September 1903, Bunau-Varilla was

drawn into this conspiracy and

he became the movement's principal

contact man in the United States. It

was hoped he could secure assurances

that the United States would pre-

vent Colombia from retaliating against

the rebels. Fortunately for Bunau-

Varilla, Francis B. Loomis was the

assistant secretary of state. On October

10, Bunau-Varilla called at the state

department to see Loomis, who took

him to the White House to meet President

Roosevelt. On October 16,

Bunau-Varilla visited Loomis again and

on this occasion he was intro-

duced to Secretary of State John Hay. In

these meetings Bunau-Varilla was

completely open about the possibility of

a Panama Revolution and he

expressed the need for the United States

to fulfill its treaty obligations

to prevent bloodshed. The American

leaders denied that any pledges of

assistance were given Bunau-Varilla, but

as early as October 15, 1903,

United States naval vessels began to

move towards the Isthmus.52 Bunau-

Varilla later avowed that he guessed the

intentions of the United States,53

OHIO AND THE PANAMA CANAL 11

but said his fellow conspirators in

Panama wanted tangible evidence that

the United States would intervene in

their behalf and they demanded on

October 29 the sending of an American

warship to Colon harbor. This

caused Bunau-Varilla to rush to

Washington, where on October 29 and 30

he saw Loomis and warned him of the

seriousness of the situation in

Panama. Loomis made no promises,

Bunau-Varilla stated, but his show

of concern convinced the Frenchman the

United States had formulated

a plan of action. Bunau-Varilla asserted

he was able to infer that this

action involved the American cruiser U.

S. S. Nashville when he read a

news dispatch of October 20 that the Nashville

had departed Kingston,

Jamaica, for an undisclosed destination.

Bunau-Varilla cabled the Isthmus

that a United States warship was on the

way, and, as he predicted, the

Nashville arrived at Colon on November 2. The Panama Revolution

took

place the next day.54 Bunau-Varilla's

version of the Panama secession

movement has never been disproved, but

Loomis raised certain questions

by cabling the Isthmus at 3:40 P.M. on November

3, "Uprising on Isthmus

reported. Keep department promptly and

fully informed."55 The over-

anxious Loomis, who on that day was the

acting secretary of state, had

anticipated the movement by slightly

over two hours. Panama became an

independent nation on November 3, 1903;

on that same day Myron T.

Herrick was elected governor of Ohio.

Perhaps it was no coincidence that

the Panama Revolution occurred on

election day in the United States,

because the election returns almost

pushed events at Panama off the front

page.56

Only three days after Panama's birth,

Bunau-Varilla was named the

new republic's minister to the United

States. In this capacity he nego-

tiated the Hay-Bunau-Varilla treaty and

assured the construction of the

Panama Canal. There was criticism of the

hasty manner in which Bunau-

Varilla negotiated this treaty, as well

as the role the United States played

in the Panama Revolution. Loomis

defended the actions of both Bunau-

Varilla and the United States in an

address before the Quill Club of New

York on December 15, 1903, and he

collaborated closely with Bunau-

Varilla during the latter's tenure as

minister.57 On February 26, 1904,

Bunau-Varilla and John Hay exchanged

ratifications for the canal treaty;

Bunau-Varilla's long fight for the

Panama Canal was over, but even in

this final phase he did not fail to

acknowledge the assistance of his Cin-

cinnati friends. On November 9, 1903, he

telegraphed Taylor and Goepper,

"The center of the storm which you

started three years ago in Cincinnati

with Wulsin and Proctor [sic] has

traveled since to Washington and on

to Panama, where it just died after

violent explosion [sic]. Fair weather

sure now."58 And on New Year's Day,

1904, he asked Wulsin and Taylor,

"Do you recollect about three years

ago who could foresee what would

grow of the seed you planted there with

Procter?"59 Thus, there was an

uninterrupted history of interest and

participation on the part of Ohioans

in the Panama Canal affair. It started

with the promotion by a group

of Cincinnatians of Bunau-Varilla's

lecture tour in the United States in

12 OHIO HISTORY

1901, continued with Hanna's advocacy of

the Panama route in the United

States Senate in 1902, and culminated

with the action of Loomis in the

Panama Revolution of 1903. As

Bunau-Varilla expressed it, thanks to these

men the "beautiful Ohio" could

trace its course to the Pacific.60

THE AUTHOR: Charles D. Ameringer

is an associate professor of history at

Pennsylvania State University and a spe-

cialist in Latin American history. He

for-

merly was a member of the history

faculty

at Bowling Green State University,

Bowling Green, Ohio.

NOTES

OHIO AND THE

PANAMA CANAL

1. See the author's "The Panama

Canal Lobby of Philippe Bunau-Varilla and Wil-

liam Nelson Cromwell," American Historical

Review, LXVIII (1963), 346-363.

2. Henry F. Pringle, Theodore

Roosevelt: A Biography (New York, 1931), 305.

3. Philippe Bunau-Varilla Papers,

Library of Congress, Washington, D. C., Manu-

scripts Division. The author has made

extensive use of these papers in the preparation

of this article. All references to manuscripts in the

notes are to this collection.

4. Lucien Wulsin to Robert Batcheller,

May 28, 1906. This is a copy of a letter

written to the secretary of the

Commercial Club of Boston, in which Wulsin described

his association with Bunau-Varilla.

Another copy of this letter was recently found

among the papers of the son of Lucien

Wulsin. With annotations and an introduction

by Professor George B. Engberg of the

University of Cincinnati, it was published

in the Bulletin of the Cincinnati

Historical Society, XXII (1964), 186-192.

5. This fact is revealed in a series of

letters exchanged between Baker and Bunau-

Varilla in 1898 and 1899.

6. Philippe Bunau-Varilla, Panama:

The Creation, Destruction, and Resurrection

(New York, 1914), 174.

7. Bunau-Varilla to Wulsin and William

Watts Taylor, December 12, 1900. There

is no record of any correspondence in

the Bunau-Varilla Papers between Bunau-

Varilla and the Cincinnatians before

December 11, 1900.

8. These included Baker, John Bigelow,

former American minister to France,

who met Bunau-Varilla in Panama and

became a close friend, and Frank Pavey, a

New York attorney.

9. Taylor to Bunau-Varilla, December 13,

1900.

10. Professor Engberg reaches the same

conclusion from a study of the minute

books and correspondence files of the

Cincinnati Commercial Club. Bunau-Varilla

was a man of some means, and, although

he was a stockholder in the French Panama

Canal Company and profited from its sale

to the United States, the author is convinced

that money was not the primary concern

in Bunau-Varilla's campaign for the Panama

route.

11. Asher C. Baker to Percy Peixotto,

February 7, 1901. Peixotto was a mutual friend

in Paris to whom Baker described these

events.

12. Bunau-Varilla, Panama, 179.

13. Bunau-Varilla to Sir Edwyn Dawes,

December 24, 1900. Bunau-Varilla lamented

that he would have to express his ideas

in a foreign tongue, but, in fact, his English

was quite good.

14. Taylor to Bunau-Varilla, January 28,

1901.

15. Ibid.

16. Wulsin to Batcheller, May 28, 1906.

17. Ibid.; Bunau-Varilla to John

Bigelow, January 17, 1901.

18. Several mutual friends noted

Bunau-Varilla's success: Wulsin to Bunau-Varilla,

January 25, 1901, and Bigelow to

Bunau-Varilla, April 25, 1901.

19. Wulsin to Batcheller, May 28, 1906;

Bunau-Varilla, Panama, 181.

20. Wulsin to Bunau-Varilla, March 15,

1901.

21. Baker to Peixotto, February 7, 1901.

22. Cyrus McCormick to Bunau-Varilla,

February 14, 1901.

23. Gustav Schwab to Bunau-Varilla,

February 28, 1901.

24. A. O. Elzner to Bunau-Varilla, April

14, 1901.

25. Bunau-Varilla to Taylor, March 20,

1901.

26. Taylor to Bunau-Varilla, March 17,

1901.

27. Bunau-Varilla to Hanna, March 20,

1901.

28. James Deering to Bunau-Varilla,

March 23, 1901.

29. Isaac Seligman to Bunau-Varilla,

March 27, 1901.

30. Bunau-Varilla, Panama, 184.

31. Ibid., 187.

32. Taylor to Bunau-Varilla, July 25,

1901.

33. U. S. House of Representatives, 62

cong., 1 sess., Committee on Foreign Affairs,

The Story of Panama: Hearings on the

Rainey Resolution (Washington, 1913),

150-157;

Thomas Beer, Hanna, Crane, and The

Mauve Decade (New York, 1941), 596-600.

34. Ameringer, "The Panama Canal

Lobby," passim.

35. Bunau-Varilla, Panama, 187.

36. Bunau-Varilla to Charles de Lesseps,

April 9, 1901.

37. Cincinnati Commercial Tribune, September

13, 1901.

38. On October 3, 1908, the New York World

published a story which said that a

"Wall Street syndicate" was

behind the United States acquisition of the Panama

70 OHIO

HISTORY

Canal, and one of the alleged

participants in the syndicate was Charles P. Taft, the

brother of William Howard Taft. These allegations were

never satisfactorily proven

and they were regarded by some as a

maneuver to embarrass Taft's candidacy for

president. Concerning Bunau-Varilla's

activities in Cincinnati, the author has not found

any mention of a member of the Taft

family.

39. Wulsin to Bunau-Varilla, February 3,

1902.

40. Taylor to Bunau-Varilla, January 28,

1901.

41. Bunau-Varilla to Mrs. Myron T.

Herrick, June 14, 1902.

42. Philippe Bunau-Varilla to Maurice

Bunau-Varilla, March 15, 1901.

43. Deering to Bunau-Varilla, March 30,

1901.

44. Bunau-Varilla to Deering, March 30,

1901.

45. Deering to Bunau-Varilla, April 1,

1901.

46. Wulsin to Bunau-Varilla, February

25, 1902.

47. Jacob H. Bromwell to Wulsin,

February 26, 1902.

48. Bunau-Varilla to Myron T. Herrick,

June 2, 1902.

49. Liberty E. Holden to Bunau-Varilla,

June 6, 1902.

50. Bunau-Varilla to Herrick, June 14,

1902.

51. Bunau-Varilla to Wulsin and Taylor,

June 21, 1902.

52. Miles P. DuVal, Cadiz to Cathay (Stanford,

Calif., 1940), 303.

53. Bunau-Varilla, Panama, 318-319.

54. Ibid., 329-336.

55. DuVal, Cadiz to Cathay, 327.

56. Ibid., 310, 332.

57. Bunau-Varilla to Loomis, December

31, 1903. Loomis was particularly helpful

in Bunau-Varilla's efforts to secure the

recognition of Panama by the nations of the

world.

58. Bunau-Varilla to Taylor and Edward

Goepper, November 9, 1903.

59. Bunau-Varilla to Wulsin and Taylor,

January 1, 1904.

60. Bunau-Varilla to Taylor, June 11,

1901.

THE OHIO ROAD

EXPERIMENT

1. The Signal, December 17, 1914. The bulk of the material for this

article was taken

from the National Archives, Washington,

D. C. I should like to thank the College Research

Institute of Texas Western College for

making my research in Washington, D. C., pos-

sible. Microfilm of the Signal, one

of Zanesville's daily newspapers, was made available

to me by the Ohio Historical Society,

for which I wish to express my appreciation.

2. Work on the "West Pike" was

begun in August 1829. The first section of twenty-one

miles west of Zanesville was

substantially finished and opened to regular travel in 1831.

By 1833 work on the remainder was

sufficiently advanced to permit mail service over the

whole length of the road, though it was

not fully completed until late in 1835. Reports of

the Secretary of War, Senate

Executive Documents, 21 cong., 2 sess., No. 17, p. 16; 22

cong., 1 sess., No. 58, p. 2; 23 cong.,

1 sess., No. 1, p. 81; 24 cong., 1 sess., No. 1, p. 194.

For vivid descriptions of the old

National Road, see the following: Thomas B. Searight,

The Old Pike: A History of the

National Road, with Incidents, Accidents, and Anecdotes

Thereon (Uniontown, Pa., 1894); Archer Butler Hulbert, The

Cumberland Road (Historic

Highways of America, X, Cleveland, 1904); R. Carlyle Buley, The Old

Northwest: Pio-

neer Period, 1815-1840 (Indianapolis, 1950); Philip D. Jordan, The National

Road (In-

dianapolis, 1948).

3. Hulbert, The Cumberland Road, 123,

174-187.

4. Jordan, The National Road, 169,

175; see also Senate Executive Documents, 23

cong., 1 sess., No. 1, p. 170.

5. Wayne E. Fuller, "Good Roads and

Rural Free Delivery of Mail," Mississippi

Valley Historical Review, XLII (1955), 67-83.

6. Ibid., 81-82; United States Statutes at Large, XXXVII,

551-552.

7. Joint Report of the Progress of Post

Road Improvement, no date, Records Relating

to Federal Aid Road Acts, Records of the

Post Office Department, Record Group 28,

National Archives (hereafter referred to

as Postal Records).

8. State of Ohio certification of money

available for post-road improvement, March

20, 1914; Muskingum County certification

of money available for post-road improvement,

March 13, 1914; Licking County

certification of money available for post-road improve-

ment, March 13, 1914; Second Economic

Study, Ohio Post Road, 2 (the date this report

was written is unknown, but the study

was made May 11-22, 1916); Clinton Cowen to

L. W. Page, June 5, 1915, all in

Correspondence, Reports, and Studies Relating to Post

Roads, Records of the Bureau of Public

Roads, Record Group 30, National Archives (all