Ohio History Journal

A HISTORY OF LOCAL AGRICULTURAL

SOCIETIES

IN OHIO TO 1865

BY ROBERT LESLIE JONES

Local agricultural societies are among

the victims of the pres-

ent war. To cooperate in conserving

rubber and in eliminating

unnecessary travel, many of them

cancelled their fairs in 1942, and

doubtless most, if not all, will do so

in 1943. The disappearance

of the fairs, even if it is temporary,

emphasizes their significance

as an institution, and makes it worth

while to trace the early his-

tory of the societies which have

sponsored them.

At the time of the settlement of Ohio,

there were already

agricultural societies in the eastern

states. These were mostly in

the larger towns, and were in practice

restricted to men of capital

and education, that is, to those who

were, or who aspired to be,

gentlemen farmers. They were in general

patterned after British

societies of a little earlier period.

All of them were supported by

fees from their members, which were used

to build up agricultural

libraries and to provide prizes for

essays on various subjects of

farm interest and premiums for the best

crops. They were much

closer in their functions to the learned

associations of the day

than to modern agricultural societies.1

With their New England background, it

was natural for the

Ohio Company pioneers to reproduce in

their new home the

eastern institutions with which they

were acquainted. As early

as they could, which was "soon

after the close of the Indian war

in 1795," they organized an

agricultural society at Marietta. The

members were prominent citizens who

"attempted to aid the com-

munity with their knowledge and

experience." As the society,

1 Rodney H. True. "The

Early Development of Agricultural Societies in the

United States;" Annual Report of

the American Historical Association for the Year

1920

(Washington, 1925), I, 295-9.

(120)

AGRICULTURAL SOCIETIES IN OHIO 121

like its eastern prototypes, made little

appeal to practical farmers,

it did not last long.2

So far as is known, no successor

appeared for more than

twenty years. Then, as in the East,

there was a sudden interest

in agricultural societies, and several

came into existence at ap-

proximately the same time, all modelled

more or less on the Berk-

shire plan of Elkanah Watson. The

Agricultural Society of the

County of Trumbull was organized at

Youngstown in December,

1818. It was dissolved after four years,

owing to a dispute over

changing the place of the annual

meeting. Another was formed

at Marietta early in 1819 by

representative citizens of Washing-

ton County and of Wood County, Virginia.

This had little vitality,

for within two years it was not known

whether it was even in

existence. All that its officers

accomplished was the printing of a

constitution. In July, 1819, a general

meeting of citizens of Cin-

cinnati appointed a committee which drew

up a constitution for

a third society, "The Cincinnati

Society for the Encouragement

of Agriculture and Domestic

Economy," with membership re-

stricted to Hamilton County.3 Other

societies were formed dur-

ing the 1820'S. Their location, their

dates of organization and of

disappearance (when known) and other

remarks in connection

with them will be found in the tabular

summary given later. With-

out state support, and without any

tangible appeal to the rural

population, most of these societies soon

withered away. In October,

1831, it was declared that "we

could have fifty societies where

there are now but five."4

The early societies frequently lacked

even the small amount

of money necessary for printing

announcements or defraying other

incidental expenses. It was therefore

not infrequently suggested

that they should be subsidized by the

State, in imitation of the

practice of Pennsylvania, where, it was

said, a grant of about

2 Julia Perkins Cutler, Life and

Times of Ephraim Cutler prepared from his

Journals and Correspondence (Cincinnati, 1890), 196.

3 Cincinnati Western Spy and

Cincinnati General Advertiser, August 21, 28, 1819;

Marietta American Friend, February

26, 1819; ibid., February 23, 1821; Marietta

American Friend & Marietta

Gazette, August 19, 1825; Ohio State

Board of Agri-

culture, Annaul Report for the Year

1860 (Columbus), Part II, 426-7. Hereafter this

authority is cited as Ohio

Agricultural Report.

4 Farmer's Reporter and United States

Agriculturist; containing Original and

Selected Essays (Cincinnati), October, 1831, 9.

122 OHIO

ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

fifty dollars

to each county society had given a great stimulus

to the

organization of such bodies.5 As a result of this agitation,

an act was

passed February 25, 1833, "to authorize and encour-

age the

establishment of agricultural societies in the several coun-

ties of this

state." It provided that the county commissioners

should be

required to call a meeting to organize an agricultural

society for

their county; that an assembly thus called, if exceed-

ing twenty

persons, could elect officers, including a president, a

vice

president, a recording secretary, a corresponding secretary,

a treasurer

and ten directors; that the president, treasurer and

directors

should have power to make all necessary by-laws; that

no member

should be required to pay a fee in excess of five dollars

a year; and

that the county commissioners might, "if they deem

it expedient,

appropriate out of the county funds for the bene-

fit of the

society, a sum not exceeding fifty

dollars in any one

year."6

The law of

1833 proved to be most unsatisfactory. It made

no provision

for a state board to collect information or supervise

or coordinate

the county societies. Moreover, the county commis-

sioners were

not obliged to grant money from the county treas-

ury unless

they chose, and most of them declined to do so. Ac-

cordingly,

after a flurry of interest in creating new societies in

1833,

doubtless largely in anticipation of obtaining county grants,

few more were

organized. The existence of many of these, more-

over, was

almost nominal. It was stated in 1841 that there were

in Ohio only

"some half dozen very efficient, and double the num-

ber very

inefficient county societies."7

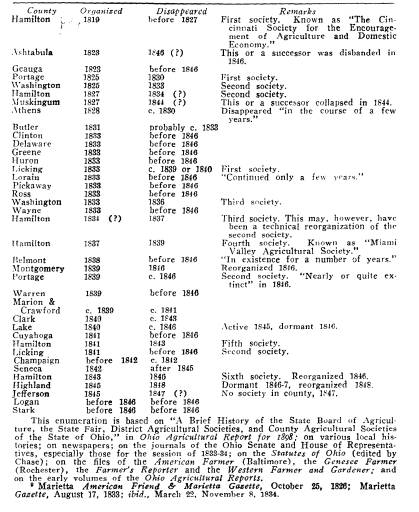

In the table

below, an effort is made to list the county societies

which had an

existence before 1846. It is not claimed that the

enumeration is

complete, but it is hoped that it will be useful.8

5 Cincinnati Commercial

Register, December 27, 1826, quoted in "Old Northwest"

Genealogical

Quarterly (Columbus), X (1907), 315-6.

6 Statutes of Ohio and of the Northwestern Territory,

adopted or enacted from

1788 to

1833 Inclusive . . . (edited by S. P.

Chase, 3 vols., Cincinnati, 1833-5), III,

1943-4.

7 Western Farmer and Gardener (Cincinnati), II

(1840-1), 268; Ohio Cultivator;

a

Semi-Monthly Journal of Agriculture and Horticulture (Columbus), II (1846), 36.

8 County

Agricultural Societies in Ohio before 1846.

County Organized Disappeared Remarks

Trumbull 1818 c. 1822

Washington 1819 c. 1821 First society. With Wood County, Va.

|

AGRICULTURAL SOCIETIES IN OHIO 123 The societies of the period before 1846 had a variety of activities. Those in Washington County, which may be regarded as typical, at different times offered prizes for the best fields of wheat and corn, obtained seed wheat for the use of their mem- bers, and built up a small library of eastern agricultural periodi- cals.9 The most noteworthy object, however, was the holding of exhibitions at which premiums were offered. 9 Marietta American Friend & Marietta Gazette, October 25, 1826; Marietta Gazette, August 17, 1833; ibid., March 22, November 8, 1834. |

|

|

124 OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL

QUARTERLY

When and where the

first fair was held in Ohio is not certain.

All of the early

agricultural societies planned to hold fairs, but

not all of them

managed to do so. The society at Youngstown, for

instance, planned to

have an annual cattle show, though it does not

seem to have ever held

one. Similarly, the first society at Cincin-

nati had a meeting in 1820 at which it agreed to award premiums

at its fair, which was

to be held at a local hotel. In 1823, the

Ashtabula County

society held a cattle show and fair at Austin-

burg, and the Geauga

County society one at Chardon. The first

exhibition in

southeastern Ohio was held at Marietta in 1826.

Other counties in

which fairs were held before 1833 were Portage,

Athens and Butler.10

These early fairs did

not much resemble those of today, for

they were close

imitations of those sponsored by Elkanah Watson

and his followers in

the East. The first fair of the Washington

County society was

thus described:

At 10 o'clock, A. M.

the Society met in the Court Room and received

a handsome accession

in numbers--elected the officers for the ensuing year;

at 11 the procession

was formed under Capt. F. Devol, as marshal of the

day, and with music

preceding, marched to the Church fronting the Com-

mon, where we had

music, prayers, and an address by the President,

Joseph Barker, Jr.,

Esq., which was cordially received.

More time having been

taken up in examining the stock &c. &c. than

was anticipated, the

company sat down to an excellent dinner at 3 P. M.--

At 4, the Society

repaired to the Court Room when the several committees,

by their several

chairmen announced the names of the persons to whom

the premiums had been

awarded, & who were requested by the President to

come forward to the

Treasurer, sitting at the table, and take their cash.11

As the items entered

in competition were few, the societies

needed no special grounds

or even buildings for these exhibitions.

In some places the

exhibition was held on the village square. The

Montgomery County

society held its fairs in the wagon-yard,

stables and sheds of a

hotel at Dayton.l2

Judging was informal and unscientific. Its

defects were

10 American Former,

I (1819-20), 295; Marietta American

Friend & Marietta

Gazette, October 25, 1826; Farmer's Reporter, October,

1831, p. 9; Charles M. Walker,

History of Athens

County, Ohio, and inc dently of the Ohio Laid Company and the

First

Settlement of the State at

Marietta (Cincinnati, 1869),

184; Ohio Agricultural

11 Marietta American Friend & Marietta Gazette, October

25, 1826.

12 Western Farmer and Gardener, III (1841-2), 55.

AGRICULTURAL SOCIETIES IN OHIO 125

clearly revealed by a critic of the

Hamilton County society (which

disappeared about 1837):

We have never been provided with

suitable pens for the domestic animals

--the committees have thus labored under

the greatest disadvantages in

their examination of them. The animals

have been huddled together in a

small circle, surrounded by the

spectators and owners, this one and that

one obtruding their remarks, confusing

and interfering with the judges.

All that they were enabled to do, was to

give the animals a hasty glance

of the eye, a slight handling, and they

are disposed of about as fast as a

Kentuckian would count over a drove of

hogs! This is very unsatisfactory

both to the committee and owners.13

Premiums were small. At the Ashtabula

County exhibition

of 1823, they amounted to only $40. At

Chillicothe in 1833, they

amounted to about $200, mostly in

silver plate. Yet even prizes

like these were a strain on the meagre

financial resources of the

societies. The Pickaway County society

of 1833 had in its treas-

ury only $188, of which $80 came from

membership fees, $58

from voluntary donations by members, and

$50 from the appro-

priation by the county commissioners.14

It will be noticed that it had no

revenue from admissions.

Possibly the first society to charge

admission was that in Cuya-

hoga County, which in 1841 collected

twelve cents and a half from

non-members who entered the exhibition

room.15

It was doubtless to keep the premiums on

livestock as attrac-

tive as possible that it seems to have

become the practice by the

early 1840's, if not sooner, to award to the

successful competitors

in the class of "domestic

manufactures," which included various

grains, "honey, silk, butter,

&c. &c.," merely medals and cer-

tificates.l6

The show of livestock was ordinarily the

outstanding aspect

of these early fairs. The consequence

was that it became almost

conventional to claim that the local

society, no matter how small or

weak it might be, was doing a great deal

to improve the breed of

13 Ibid., II, 78.

14 "A Brief History &c.," 773; Journal of the Senate of

the State of Ohio,

32 General Assembly, 1 Sess., 1833-4, p.

416; Journal of the House of Representatives

of the State of Ohio, 32 General Assembly, 1 Sess., 1833-4, p. 455.

15 "A Brief History &c.,"

775.

16 Western Farmer and Gardener, III, 245.

126 OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND

HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

cattle, horses, sheep or swine.17 Unfortunately,

the exhibitors

were often altogether professional

breeders or importers. Never-

theless, the mere display of superior

stock was a great advantage,

for ordinary farmers thus became

acquainted with it, and could

compare it mentally with the grade

animals in their own barn-

yards. Sometimes there were only a few

improved Shorthorns or

Devons, or a thoroughbred, or a couple

of Bedford or Big China

hogs. In 1834, however, the Ohio Company

for Importing English

Cattle exhibited at the Ross County fair

nineteen head of purebred

Shorthorns recently selected by its

agents from some of the best

herds in Great Britain.18 This

came to be considered a landmark

in the history of cattle improvement in

the Scioto Valley.

Yet displays of livestock did not

altogether dominate the ex-

hibitions. Occasionally variations were

introduced into the pro-

grams. In 1834, the directors of the

Washington County society

presented a shepherd's crook to Benjamin

Dana of Waterford,

"as the man who, above all others,

has cherished the wool growing

interest of the County."19 Again,

in 1833 Obed Hussey, who had

recently invented a reaper, gave it a

public demonstration at the

Hamilton County exhibition at

Carthage.20 Threshing-machines,

driven by horse-power, were similarly

demonstrated by their

manufacturers.21 Some of the

exhibitions had plowing matches,

but these were usually disappointing. At

Carthage in 1844, it was

stated that "there was but little

spirit manifested at the Ploughing

Match, and hardly any competition, only

two teams entering the

field. The premium was too small to create any emulation."22

Some of the early exhibitions terminated

in a sale of the articles

which were in competition. At Marietta

in 1826 "several articles

were sold at auction, at fair

prices."23 These seem to have been

mostly butter and cheese. At Chillicothe

in 1833, there was "a

general sale," at which "the

articles sold for very high prices, flour

17 Cf. John Delafield, A Brief Topographical Description of

the County of Wash-

ington, in the State of Ohio (New York, 1834), 31.

18 Ohio Agricultural Report for 1857,

301.

19 Marietta Gazette, November 1,

1834.

20 William T. Hutchinson, Cyrus

Hall McCormick; Seed Time, 1809-1856 (New

York and London, 1930), 159-60.

21 Marietta Gazette, November 11,

1836.

22 Western Farmer and Gardener, V

(1844-5), 81. The premium was $3.00.

23 Marietta American Friend &

Marietta Gazette, October 25, 1826.

AGRICULTURAL SOCIETIES IN OHIO 127

(for example) at about $5 and $6 per

barrel, saddles for $30,

leather at an advanced price, jeans and

other woolen manufac-

tures, for more than their intrinsic

value, and hats at the rate of

from $5 to $16."24

The early agricultural societies were at

best small and weak.

The history of any one of them might be

summarized in the

phrases applied by the local historian

to the Licking County so-

ciety of 1833: "Its revenues were

small, exceeding small; the

number of its members was small; . . .

its premiums were small

in amount, and awarded to a small number

of exhibitors; the

attendants at its fairs were small in

number; indeed, it was the

'day of small things' with it from

beginning to end."25

Various explanations were given for

their weakness. A fairly

common one was that the farmers were

apathetic towards the work

of the societies. Thus, the exhibitions

of the Montgomery County

society, organized in 1839, it was

reported,

have been of an interesting character,

but have been sustained by but a

few and have been very slimly attended

by the farmers of the county. To

the disgrace of the farmers, the burden

of the expense of these exhibitions

has been borne by the citizens of the

town, and it becomes more difficult

each year to procure money, as the

argument that "by and by the farmers

will wake up to their interests,"

has grown very threadbare

already.26

The farmers had a reason for this

attitude towards the so-

cieties, as another extract shows.

The farmers say--we know it, for

we have heard it often repeated--

that they were aristocratic affairs, in

which a common, plain farmer had

no voice, and was looked upon as nobody;

that these big-bugs, as they are

termed, did everything their own way;

awarded great premiums, which

they carried themselves, etc., etc.;

that these intruders from the city came

among them to dictate, and to attempt to

teach those who were better

informed than themselves.27

In recognition of the justice of this

assertion, the Montgomery

County society in 1844 decreased the

premiums offered for fine

stock and increased those offered for

grain and farm products.28

24 Ohio Senate Journal, 32

General Assembly, 1 Sess., 1833-4, p. 416.

25 N. N. Hill, History of Licking

County, 0.: Its Past and Present (Newark, Ohio,

1881), 266-7.

26 Ohio Cultivator, I (1845), 62.

27 Western Farmer and Gardener, II,

260.

28 Ohio Cultivator, I, 62-3,

128

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

Nevertheless, when every excuse is made

for the resentment

of the farmers towards the patronizing

city-dwellers, the fact

remains that the farmers did little or

nothing towards maintaining

the societies. The passage last quoted

continues:

. . . Did these very farmers, who now

grumble, and throw the blame upon

others, do their duty? We rather

suspect they did not; and it ill becomes

them to find fault with those who did.

Who furnished the greater part of

the funds? Who did the labor--the hard

work, necessary for carrying on

the affairs of such a society? Did these

gratuitous labors result in no

good? Were the laborers ever even

thanked for their toil, or receive aught

but after-complaints? If evils existed,

how did it happen that farmers

took so much less interest in that which

was intended for their improvement

than the residents of the city? Why was

there not a majority of farmers

in an Agricultural Society?

There were other factors in the weakness

of the societies such

as the farmers' contempt for theoretical

agriculture and their belief

that the agricultural associations could

not help them to make more

money. Again, as mentioned earlier, the

societies had little income,

and worked without knowledge of one

another's activities and

problems.

It was recognized that an agency of

supervision and co-

ordination was needed. Proposals were

therefore made from time

to time for the establishment of a state

board of agriculture, to be

financed in whole or in part by grants

from the government.29 In

1838, on the initiative of the Licking

County Society, a meeting

of delegates from different parts of the

State was held at Colum-

bus. The convention proceeded to

organize a state agricultural

society, and to elect officers. It is

quite clear that this society never

accomplished anything of significance,

for in 1841 its activities

seem to have been limited to holding an

exhibition at Chillicothe,

which drew from only Ross and one

adjoining county.30

During the winter of 1845, several

well-known leaders of

agriculture in the State proposed that a

convention should be held

during the summer to discuss a program

which included the pos-

sible establishment of a state board of

agriculture, governmental

or other encouragement to the county

societies, and suggestions

29 Cf. Ohio Senate Journal, 33 General Assembly, 1 Sess., 1834-5, p. 180.

30 Hill, History of Licking

County, 266; Western Farmer and Gardener, II, 268.

AGRICULTURAL SOCIETIES IN OHIO 129

for legislation to be offered to the

General Assembly on such sub-

jects as destruction of sheep by dogs.

The convention accordingly

met at Columbus June 25-26, 1845, and

drew up a series of reso-

lutions. One requested that the next

General Assembly should

make provision for the election of a

State Board of Agriculture.

Another recommended that the General

Assembly should modify

the existing law affecting agricultural

societies, to bring it into har-

mony with the New York law. By this, the

state treasury would

grant a small sum each year to every

county society which raised

an equal amount by fees or

contributions, and complied with what-

ever regulations might be drawn up by

the state board. As the

delegates were of the opinion that a few

thousand dollars of state

money spent for the promotion of

agriculture would be repaid in

greater prosperity and so in more

revenues, they recommended the

appropriation of $2000 to the state

board, and $5000 for distribu-

tion among the county societies.31

On February 28, 1846, the legislature

enacted a law creating

a State Board of Agriculture, consisting

of fifty-two persons, half

to be elected each year. The board was

organized April 1, 1846.32

The act also provided for a fairly

satisfactory arrangement for

financing the county societies. It was

made mandatory, when

thirty or more persons in a county (or

in a district including two

counties) formed an agricultural

society, which then raised $50

or more voluntarily, for the county

auditors to add an equal

amount, this not to exceed $200.33

The effect of the act was to revive a

number of the dormant

county societies and to bring about the

organization of many new

ones. By the end of 1846, there were

nineteen revived or new

county or district societies. Eight more

were added in 1847, nine

in 1848, seven in 1849 and ten in 1850.

By the end of 1852, there

were over seventy in Ohio. In 186O there

were eighty-four county

societies.34

31 Ohio

Cultivator, I, 41, 73, 105.

32 Beginning in 1850, one of the most

important functions of this board was the

holding of the State Fair. Though the

development of this fair falls outside the sub-

ject matter of this article, it is worth

noting that its managers encountered the same

problem as did those of the county

societies.

33 Ohio Agricultural Report for 1846,

71-3.

34 Ibid., 1846-5I, passim; ibid.,

1859, 520; Ohio Cultivator, VIII

(1852), 361.

130 OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND

HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

The societies organized after 1846

benefited from the pre-

vailing prosperity possibly even more

than from improved organi-

zation. Their fairs became larger and

more popular, and under-

went a rapid metamorphosis. Indeed, the purely agricultural

aspects of the exhibitions tended to be

overshadowed in many

instances by other features. These, if

they added nothing to the

educational value of the exhibitions,

did bring the crowds.

To lure farmers to the exhibitions, some

of the societies re-

vived the attractions of the Log Cabin

and Hard Cider political

campaign. At the Mahoning County

exhibition of 1849 "a marked

feature was the township trains of

working oxen. Boardman, Ells-

worth, Green and Canfield, each

furnished a train containing in

the whole, near TWO HUNDRED PAIRS. . . .

Each train

came on to the ground drawing a huge

wagon decorated with

branches of forest trees, evergreens,

flowers, and flags, and filled

with happy, smiling men, women and

children--and in some a

band of the good old continental music

of the drum and fife."35

Within a few years, the exhibitions were

drawing such large

crowds that the directors, not without

trepidation, decided to en-

close their grounds and charge

admission. It was soon shown that

there was no reason for fearing that the

patronage would end

forthwith. The remarkable growth in

popularity of the fairs of

the various societies may be traced in

the expansion in the size of

the crowds and the corresponding

increase in gate receipts of one

of them. In 1846, the newly organized

Washington County so-

ciety was so uncertain of the success of

its coming exhibition, that

it held a special meeting, and "Resolved,

That we will furnish a

free dinner on the day of the fair, and

invite all to come." Ac-

cordingly, on the day of the exhibition,

"the Society and invited

guests" when to a hotel for dinner.

Two years later, the society

collected $52.25 from admission fees, evidently from those who

wished to view the exhibits of

manufactured articles, for the money

was applied to premiums on these. In

1856, at "the best Fair ever

held in Washington County," the

amount received from an esti-

mated 5,500 persons was $1,141. The next

year the receipts were

over $1,300, and in 1860 nearly $1,400. It is

impossible to tell

35 Ohio Cultivator, V (1849), 323.

AGRICULTURAL SOCIETIES

IN OHIO 131

what the attendance

was, for under the "family ticket" system, a

dollar admitted a farmer,

his wife, their children, the hired man

and as many neighbors

as could crowd into a wagon.36

For a few years,

beginning about 1852, the "hen fever" helped

bring crowds to the

fairs.37 The two great drawing cards, begin-

ning about 1850, however, were

sideshows and other amusements

or entertainments, and

horse racing.

As soon as the

exhibitions began to attract even small crowds,

all kinds of parasites

appeared. At the Knox County exhibitions

in 1852, it was stated

that "in the way of 'noise and confusion' we

had any quantity of

catch-pennies, in the shape of peddlers of

soap, toothache drops,

etc."38 Even more of a nuisance than the

medicine-shows were

the refreshment stands located in the vicinity

of the grounds, which

were usually merely "drinking-shanties."

To help eliminate the

latter source of disorder, a law was passed

in 1856 which

prohibited the setting up of shops, booths or tents

within two miles of a

fair ground, and subjected offenders to fines

ranging from $5 to

$50.39

The sideshows proper

were harder to deal with. At first they

were mere

accompaniments of the exhibitions. They came with

their monkeys, fat

women, two-headed calves and other monstrosi-

ties, and their swings

and whirligigs, and established themselves

as near the spectators

as they could. Though the directors of the

societies had no

control over them, they found that they brought

discredit to the

exhibitions. Yet, as the sideshows undeniably

helped to draw crowds,

most of the societies by 1860 were admit-

ting them to the

exhibition grounds for a fee. Sometimes they

became disgusted, and

tried to get rid of them again. One writer,

who had worked for

their elimination from the exhibitions of the

Highland County

society, described the result. He wrote:

I at one time took an

active part in opposition to sideshows, and suc-

ceeded a few years ago

in moving them out; but I now frankly own that

36 Marietta Intelligencer, July 30, October 22,

1846; ibid., November 30, 1848; ibid.,

October 15, 1856; ibid.,

October 14, 1857; ibid. (triweekly edition), October 6, 1860.

37 A report on the

Wayne County exhibition of 1852 asserted that "the hen fever is

raging rather

favorably--some twenty coops of fancy fowls being upon the ground."

Ohio Cultivator, VIII. 315. The rage for "Shanghai" and other

Asiatic fowl had run

its course by 1857. Ohio

Agricultural Report for 1857, 25.

38 Ohio Cultivator, VIII, 309.

39 Ibid., XII (1856), 132.

132

OHIO ARCHEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

I have changed my opinion. I find that

our funds get low, and our crowds

small. And besides, if we don't let them

in, they will fix themselves up

outside.... When we have them inside, we

have them under our control,

and receive a good deal of money from

them. We rented the right for a

swing for $35, which was perhaps too

low. We must resort to some

means to get the people inside, and, as

the church people say, if we once

get them inside, they can't help but

imbibe some good, and we will get their

money.40

The directors as a rule, therefore, to

get the money necessary to

operate their societies, admitted the

sideshows, though it was said

that probably no society in the State

made as much as $200 directly

from them.41 In 1861 a

"law to protect fairs" made it possible for

them to keep such sideshows as did not

pay a fee, or were other-

wise undesirable, at a distance of a

quarter of a mile from the fair

ground.42

Of course, not all the amusements were

provided by fakers

or sideshows. At the Washington County

exhibition of 1856,

there was a brass band on the grounds

all day long, and a local

fire brigade put on a demonstration with

their new engine.43 In

1858, "a band of Callithumpians

afforded a good deal of amuse-

ment by their grotesque costume and

clownish actions. The Dan

Rice of the band was a fellow of

considerable jest and humor, and

at his second apperance in the ring

caused great merriment." Nor

was this all. "In the evening, the

exhibition of Fire Works, by

Mr. Deihl, drew together 500 or 600

people. It was by far the

finest and richest display ...

ever seen."44

It was found that some type of horse

racing attracted crowds

more effectively than any other

inducement that could be afforded.

Horse racing was, of course, of long

standing in Ohio. There

were three-day meetings on the Pickaway

Plains in 181O, 1811 and

1812, with purses ranging up to $80, and

on the common at Mari-

etta in 1814.45 Annual fall

meetings were held about 1825 at Cin-

40 Ohio Agricultural Report for 1865,

Part II, 57-8.

41 Ibid., Part II, 60.

42 Ohio Cultivator, XVII (186l),

180.

43 Marietta Intelligencer, October

15, 1856.

44 Ibid., October 27, 1858.

45 Chillicothe

Supporter, April 7, 1810; ibid., November 2, 1811; Marietta American

Friend, October 22, 1814. It is worth noting that even the

latter was conducted

"agreeably to the rule of racing in

Virginia."

AGRICULTURAL SOCIETIES IN OHIO 133

cinnati, Chillicothe, Dayton and

Hamilton. About 1838 or 1839,

there were fifteen regular race-courses

in Ohio. Most of these

disappeared in the middle 1840's.46

These races were all of the running

type. Those which came

to flourish at the fairs were trotting

races, or "trials of speed."

These, however, did not obtrude

themselves on the fairs fully

developed. In Ohio at least, they were

preceded by what was

referred to as "female

equestrianism."

In 1851 the Licking County society

offered three premiums

"for ladies' riding horses."

Evidently the intention was that each

rider should put her horse through a few

conventional paces in the

ring, displaying as she did so the

latest in riding habits. The

directors were as much astonished as any

of the spectators when

a country tomboy (who had probably never

heard of Godey's

Lady's Book) upset their program.

Three horses were entered, and made

their debut within the ring at

an easy pace. Misses Seymour, of

Madison, and Marple, of Newton, at

first led the ring with decided

advantage. Miss Hollinbeck, of Hanover,

followed riding the horse of N. B. Hogg,

in walking dress, but being a

girl of true knightly grit, soon

dexterously reined in her horse, and by a

few well applied blows from her riding

whip, brought up his mettle to the

guage of her own, then giving him rein,

dashed forward, and taking the

"inside," such a wild Arab

flight sober Buckeyes never saw before. On,

on flew the beautiful steed, and the

thousands cheered heartily--the winds

played the mischief with her petticoats,

but her victory was complete. Then

a series of evolutions, curvettings and contra

pas, showed what country

girls can do when they get the reins

into their own hands.47

The next year, as one would expect, many

societies offered

prizes for ladies' saddle-horses, that

is, for displays of riding.48 At

the Columbiana County exhibition in 1854

it was announced that

"the steed with his fair rider will

grace the ring and draw thou-

sands to the exhibition, notwithstanding

some considerate people

have voted ladies riding a very

indelicate business. . . . The first

premium is to be a splendid horse! and

the second a gold watch."49

The exhibitions by the equestriennes in

some instances,

46 Ohio Agricultural Report for 1857,

356; Hill, History of Licking

County, 155.

47 Ohio Cultivator, VII (1851), 331.

48 Ibid., VIII, 329.

49 Ibid., X (1854), 161. About 1854, "female equestrianism"

became a popular fea-

ture of fairs in other parts of the

country. Wayne C. Neely, The Agricultural Fair

(New York, 1935), 193-4: Blanche H.

Clark, The Tennessee Yeomen, 1840-1860 (Nash-

ville, 1942), 88-9.

134 OHIO ARCHEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL

QUARTERLY

strange to relate, became very partisan

in character. At the Wash-

ington County exhibition in 1855, a girl

from Wood County, Vir-

ginia, won the first prize, a $50 gold

watch, one from Athens

County the second prize, a $40 gold

watch, and one from Wash-

ington County the third, a gold chain

and locket. The spectators

were much displeased by the award of the

first prize to the Vir-

ginia girl, claiming that it should have

gone to the Ohioan from

Athens County, and made remarks

"calculated to wound the com-

petitors, and judges."50 The

following year, evidently as a con-

sequence of the hard feelings thus

engendered, only two ladies

appeared in competition, both from

outside the county. "If the

'Lady Equestrian Performances'

degenerate as rapidly the year to

come as they have the last twelve

months," the local editor wrote,

"they must be given up entirely at

our next Fair."51 Though as

late as 1859, the equestriennes

"proved to be the great attraction

of the day" at the Franklin County

fair,52 they had, for the most

part, lost their popularity throughout

the State. It would seem

that few of them revealed the

unconventional enterprise of the

spunky Miss Hollinbeck.

Men regarded the best performances of

the equestriennes with

an amused condescension, but they became

passionately excited

over the trotting matches which

displaced them. At the Washing-

ton County exhibition of 1856, there

was, for the first time, a

trotting match with four horses entered.

Though one of the horses

proved to be "a wheezy old fellow,

[who] lost his wind after two

or three rounds, and 'give out',"

the competition seemed to please

the spectators. The only drawback was

"a trifling disturbance in

the trotting ring" of a nature not

specified, but presumably con-

sisting of somewhat drunken fisticuffs

among the supporters of the

different horses.53 In 1857,

the "Trotting Match was the most

exciting exhibition of the

afternoon." It was so exciting, in fact,

that before the next year's exhibition

was held, the directors of

the society enlarged the ring.54

50 Marietta Intelligencer, October

17, 1855.

51 Ibid., October 15, 1856.

52 Ohio Agricultural Report for 1859, 157.

53 Marietta Intelligencer, October

15, 1856.

54 Ibid., October 14, 1857:

ibid., October 27, 1858.

AGRICULTURAL SOCIETIES IN OHIO 135

Why did there thus come to be such an

emphasis on horse

racing? Some of the agricultural society

directors rationalized an

explanation.

The design was to afford an opportunity

of introducing horses of great

speed to the notice of the public. For

fast trotters there is high market

value. In the eastern, and in all our

city markets, they sell for great, and

sometimes enormous prices; for hundreds,

and sometimes for thousands

of dollars. Even horses of quite rough

and common appearance, with this

one recommendation, sell at high rates.

This quality is property, and when

known, may be a source of income to the

individual owner, and wealth to

the county. It is an appropriate part of

our Fair to develop it, and likely

to result more in the pecuniary benefit

of those taking part in it, than

anything connected with the Society. A

common work horse, worth prob-

ably $90 or $100, was exhibited at our

last Fair. His speed as a trotter

was there made known. This one quality

got him into notice, and he has

since been sold for $300, simply because

he would trot fast.55

But no matter what was claimed, the

truth was that the horse

races with their attendant excitement

brought the crowds, and

nothing else would.

By the late 1850's, there was a real

danger that horse racing

would ruin the exhibitions. In 1857 and

1858, the independent

agricultural society in Scioto County held

fairs, which were "uni-

versally acknowledged to have been

decided failures--the fast

horse mania having destroyed all of

their interest, excepting in

the one article of horse flesh."56

That there was a horse-racing

mania at this time there is no doubt. In

1858 and 1859 there were

several exclusive

"horse-shows," nominally exhibitions, but actually

nothing but horse races, and those often

of a discreditable kind.57

The editor of the Ohio Cultivator, after

attending one of them,

held at Orwell in Ashtabula County,

remarked that "we never can

help laughing under our beard to see the

comical juxtaposition of

the deacon managers about the stand, and

the devil jockeys in the

ring, thus mutually engaged in

'improving the breed of horses'."58

The situation was such that the friends

of agriculture all over the

State were alarmed. Accordingly, in 1858 the State

Board of

Agriculture decided to offer no premiums

at the State Fair for

55 Ibid. (triweekly

edition), August 27, 1859.

56 Ohio Agricultural Report for 1858, 235.

57 Ohio Cultivator, XIV (1858),

344; ibid., XV (1859), 209.

58 Ibid., XV, 209.

136 OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND

HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

trials of speed, and recommended that

the county and district

societies should follow its example.59

In spite of this recommenda-

tion, horse racing was not eliminated

from the exhibitions.

The directors had problems in addition

to those created by

sideshows and horse racing. One problem

was the tendency on the

part of a certain class of members to

take no responsibility in the

affairs of the society or in its

exhibitions, except to pay their

membership fee, and endeavor to get it

back, and more with it, in

premiums.60 Another was in

connection with the judging of the

exhibits or races. Sometimes the judges,

however competent,

could scarcely manage to give

satisfaction, owing to the difficulties

under which they worked. Thus at

Marietta in 1853, nearly 100

cattle were turned into an open lot, and

the judges had to go about

finding the animals before they could

come to any decision on

their merits.61 Sometimes,

unfortunately, the judges were chosen

for their personal popularity, without

regard to their qualifications

as experts. An inhabitant of Butler

County showed the rather

ludicrous results.

Several years since, at our county fair,

a three year old colt received

the premium as the best yearling--a stallion

was awarded the ribbon as

the best draft stallion, when at

the same time he would not, to my certain

knowledge, draw his day's rations! At

our last county fair, a stallion that

ran at least one mile of the three, in a trotting race, was

awarded the first

premium over a stallion that trotted the

entire three miles within 8 seconds

of his running competitor.62

Though the accommodations provided for

the patrons of the fairs

were primitive enough, there were few

complaints about them.

Little would have been expected at a

picnic, which the fairs in

some ways resembled, with groups of

friends and relatives sitting

on the grass eating their lunches and

visiting.

As the societies grew in resources and

experience, their direc-

tors were able to avoid many of the

mistakes they had made

earlier. Moreover, by 1860 most of them

found it possible to

acquire permanent fair grounds. That of

the Medina County

society in 1864 had sixteen acres of

land, partly covered with

59 Ohio Agricultural Report for 1858,

176-7.

60 Ibid., 1860, Part II, 3-4.

61 Marietta Intelligencer, October

26, 1853.

62 Ohio Cultivator, XIV (1858), 6.

AGRICULTURAL SOCIETIES IN OHIO 137

woods, a race-track a third of a mile in

circumference, a large

exhibition hall, a dining hall, an

oyster saloon and a grocery.63

In addition to the county agricultural

societies, there were

sometimes local ones, which drew their

members from a few town-

ships at most. One of the first of these

was established at Oberlin

in 1835, under the name of the Oberlin

Agricultural and Horticul-

tural Society. It was evidently very

short-lived. Another came

into existence at South Charleston in

1837, and was still in exis-

tence in 1845. In 1845 several

others appeared, in Licking,

Muskingum, Franklin, Washington and

Lawrence counties, at

least, and possibly elsewhere. These

local societies, often called

"farmers' clubs," began to be

fairly numerous throughout the State

during the late 1850's.64

These clubs owed their formation to

varied factors. Some of

them were evidently the outgrowth of a

suggestion made by Mor-

ton Townshend of Elyria in a letter to

the Ohio Cultivator. In

this he proposed that farmers should

meet once a month or oftener

to discuss the merits of different

practices, describe experiments,

and, in general, stimulate one another

to improvement. If possible,

they should obtain lecturers to give a

course of instruction, as was

later to be done by the farmers'

institutes.65 One such club was in

operation in Lawrence County in 1846.

Its activities were de-

scribed as follows:

The meetings are held monthly--one at

the house of each member of

the "Club" in rotation. The

member at whose house the meeting occurs,

is required to furnish the company with

"a substantial farmer's dinner," and

to exhibit to them such improvements as

he may have made on his farm

during the year, and give a statement of

any experiments that he may

have tried, etc. Others may entertain

the company with short addresses,

discussions or remarks on matters

relating to the objects of the Society.

In this way the meetings never fail to

be highly interesting and profitable,

and greatly conducive to improvement in

agriculture, as well as to friend-

ship and good will among the members and

their friends. We were told

that the meetings are fully attended, in

all seasons of the year, and are

looked forward to by all as occasions of

much social enjoyment as well as

63 Ohio Agricultural Report for 1864, 173.

64 "A Brief History &c.," 774, 781; Ohio Cultivator, I,

42; Ohio Agricultural Re-

port for 1846, 47-8, 57, 111; ibid., 1859, xiv.

65 Ohio Cultivator, 1, 31.

138 OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL

QUARTERLY

instruction. The ladies, too,

have of late participated quite generally in

these social meetings.66

Another of these discussion clubs,

located in Montgomery County,

had a library of forty-two books, and

met once a month to hear a

lecture from one of the thirty-nine

members, and to discuss reports

from the standing committees. These

committees were supposed

to collect information on such subjects

as farm conveniences,

implements, horticulture, and farm stock

from the library, and to

embody their findings in an essay.67

Other clubs were formed because the

farmers felt the need of

improving their agriculture, and yet did

not think that they would

derive much benefit from the county

society. Thus one in Wash-

ington County, in giving its reasons for

continuing a career inde-

pendent of that of the county society,

stated that the benefits of the

county society "would only be

realized in this part of the County

by a few of the more opulent men, while

the common farmer, the

class who most need information, will be

but little benefitted. They

will not be willing to spend two or

three days, and as many dollars,

to attend the meetings and exhibitions

of the society, and even

that would be inadequate to take stock

to the county seat for

exhibitions."68

These clubs were in most respects like

the county societies.

The South Charleston society, for

example, held exhibitions every

year from 1837 to 1845. One in Muskingum

County had exhibi-

tions in 1845 and 1846, and that in

Washington County in 1845

and later. In 1851, other clubs

in Cuyahoga and Summit counties

were said to "hold their annual

fairs."69

Occasionally the clubs considered

branching out into sub-

sidiary activities. The Madison Township

Club in Licking County,

for instance, proposed to buy a

threshing-machine, as well as some

other implements, to be used by the

members in rotation. As the

editor of the Ohio Cultivator pointed

out the difficulty of assur-

66 Ibid., II. 114.

67 Ibid., IX

(1855), 84.

68 Marietta Intelligencer. July

2, 1846.

69 "A Brief History

&c.," 774; Ohio Agricultural Report for 1846, 57;

Marietta

Intelligencer, November 2, 1848; Western Agriculturist (Columbus),

1 (1851), 339.

AGRICULTURAL SOCIETIES IN OHIO 139

ing agreement in the use of these

machines, it is possible that the

experiment was not made.70

The Civil War tested the quality of the

societies, large and

small, especially in the southern part

of the State. As soon as the

war broke out, many societies found

themselves in doubt whether

to proceed with their arrangements or to

abandon their exhibitions

temporarily. For some of them, the

problem disappeared when

their grounds were taken over by the

military authorities. This

was the case in Washington, Muskingum,

Ross, Lawrence,

Hamilton and other counties.

Unfortunately for these societies,

the soldiers felt themselves under no

obligation to preserve the

property they were using. In Lawrence

County they destroyed

everything that would burn, except the

buildings they used for

shelter, and in Ross County, through

carelessness, they even burned

the sheds and other structures.71

The other societies found that their

patrons were too much

affected by the war to be interested in

exhibitions. The low prices

of produce in 1861 had a depressing

influence, with farmers exer-

cising as much economy as they could.

People were in an unsettled

state, "with a disposition to

congregate where the latest news was

to be had, there to discuss the affairs

of the country."72 Many of

the societies therefore did not hold

exhibitions, and those that did

found the attendance limited, and the

receipts correspondingly

small. In 1862, the

exhibitions were still further handicapped. In

Clermont County, for example, the

exhibition was almost a failure,

because a rebel raid was expected at any

hour. Elsewhere in the

State, the military draft came at about

the same time as most of

the fairs, with the result that there

was a feeling of depression, as

well as difficulty in getting in the

crops. In 1863, except where

the grounds were occupied by the troops,

and along the Ohio

River, the exhibitions showed signs of

revival. They were held

in more counties than in 1862, and had a

larger attendance.73

With the advent of peace in 1865, almost

all the societies

70 Ohio Cultivator, III (1847), 49.

71 Ohio Agricultural Report for 1862, 171; ibid., 1865, Part II, 228.

72 Ibid., 1861, 148-9.

73 Ibid., 1862, 142, 158-8, 174; ibid., 1863, vii.

140

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL

QUARTERLY

revived. Once more farmers loaded their

families into wagons

and drove off to the exhibitions, where

the children could drink

pink lemonade and ride on the

merry-go-round, the women could

gossip and the men could wrangle with

one another over the trials

of speed. The difficulties incident to

the war had proved the vital-

ity of the fairs. Working solutions had

been found for most of

their problems. In the future there

would be many variations and

some improvements, but their essential

character would be little

changed.