Ohio History Journal

|

Governor Rutherford B. Hayes NOTES ON PAGE 191 |

GOVERNOR RUTHERFORD B. HAYES 59

by DANIEL R. PORTER

The spirits of a discontented

Congressman from Cincinnati were decidedly

lifted late in January 1867 by a letter

from William Henry Smith, Ohio's

Secretary of State. The letter sounded

out Representative Rutherford B.

Hayes as a possible gubernatorial

candidate. This was the first indication

Hayes received that he was being

considered instead of incumbent Gover-

nor Jacob D. Cox as the Republican party's

standard bearer in the Ohio

election of 1867. His overly cautious

reply to Smith and to other similar

correspondents belied real interest in,

if not a desire for, the governorship.1

In fact, throughout his political

career, Hayes regularly assumed the pos-

ture of a reluctant candidate.

The Ohio election of 1867 was destined

to be one of the most important

of the period. Basically the national

Republican party's leadership during

the Civil War crisis and the nature of

its Reconstruction program were

under review by the voters, but on the

surface the most publicized issue

was Negro suffrage. Congressional

leaders of the party caucused in May

1866 and decided that the question of

Negro suffrage should be a state

issue.2 Hayes concurred with

this general policy decision but Governor

Cox, who opposed the Radical Republican

wing of the Union party led

by Benjamin F. Wade of Jefferson, Ohio,

took a position against Negro

voting rights. Cox could not keep the

issue off the October ballot where

it appeared in the form of a state

amendment in which the word "white"

would be deleted from the voting

requirement, thereby enabling Negro

males over twenty-one years of age to

vote.3 The Governor, who had once

proposed that a separate Negro state be

carved from the deep South, lacked

the political strength and veto power to

defeat the suffrage proposal in

the legislature, with the result that

its fate was put in the hands of the

people. To help secure passage of the

constitutional amendment, the Radi-

cal Republicans needed a strong

candidate for governor, a man who had

associations outside the Western

Reserve, who was unimpeachable in char-

acter and morals, who had a

distinguished war record, and who was not

too closely identified with the

unpopular views of tile Radicals.4

William Henry Smith of Cincinnati had

emerged as a prominent Ohio

Republican spokesman and manager during

the Civil War years. His in-

fluence secured the nomination and

election of Clevelander John Brough

as governor in 1863. Since it was

generally conceded by party leaders that

the time was right for a candidate from

southwestern Ohio, Smith began

a private canvass for a possible nominee

even before the controversial con-

stitutional amendment resolution had

passed the legislature. Hayes replied

to Smith's letter in February. He coyly

declined to allow his name to go

before the Republican state convention,

but added that he was flattered

by tile offer, would enjoy running, and

was not "indifferent" to the honor.

About the same time Hayes wrote to his

favorite uncle, Sardis Birchard,

at Fremont revealing his innermost

feelings: "This is the truth as I now

see it: I don't particularly enjoy

Congressional life. I have no ambition for

60 OHIO HISTORY

Congressional reputation or

influence--not a particle. I would like to be

out of it creditably. If this nomination

is pretty likely, it would get me

out of the scrape, and after all that I am out of political life decently."5

Hayes publicly refrained from indicating

his desire for the nomination

because his record in Congress was

undistinguished and, besides, it was too

early to know if Governor Cox would

fight for a second term. He hesitated

from January to May before making a

final decision. To his uncle he wrote

again on February 7, "I have

decided not to run. The principle reason is

I do not like in these times to leave a

place [Congress] to which I have been

chosen on my own request."6 In a

letter to Smith, he set down the condi-

tions for his candidacy. He would run

only if tile electorate of the Second

Congressional District [Cincinnati]

approved,7 if the Hamilton County dele-

gation to the nominating convention

supported him, and if no other Ham-

ilton County Union Republican wanted to

run.8

The action in late May of the Ohio

legislature placing the Negro suf-

frage question on the October ballot and

assurances that he was indeed the

leading and logical Cincinnati contender

for tile nomination, finally con-

vinced Hayes that he should run.

Therefore, on May 23 he wrote Smith

that he would throw his hat in the ring

since the legislature "squarely stood

up to the suffrage issue," unless,

he added, General Robert C. Schenck

wanted the honor.9

On June 9 at the Republican state

convention in Columbus, Rutherford

B. Hayes was nominated on the first

ballot. A month later he resigned from

Congress to launch his campaign. His

strategy became apparent in the

opening speech at Lebanon on August 5 in

which he stressed the Negro

suffrage issue.10 He received

strong support from the Western Reserve

newspapers. But outside this loyal

Republican citadel, Hayes could count

only on tle Toledo Blade, the Dayton

Journal, and the Columbus Morning

[Ohio State] Journal, for aid in

passing the amendment. There was ques-

tionable support for his candidacy, and

none for Negro suffrage, from the

three large Cincinnati dailies, the (Gazette,

the Commercial, and the En-

quirer.11 The friendly press

emphasized his war record. The Morning Jour-

nal called him "the gallant standard-bearer of Union

Republicanism in

Ohio . . ." and cooed ". . .

no one of the old Kanawah Division but will

vote for General Hayes with a will,

unless he sympathizes with the guys in

grey."12

The unpopular suffrage issue put the

Republican party on the defen-

sive. "Undoubtedly," a

Missouri correspondent wrote, "the Negro suffrage

issue will lose the party the votes of

many whose Republicanism has not

been based upon reasoning or conviction

of duty." Ratter than say "Negro

suffrage," the Republican press

used the phrase "loyal manhood suffrage,"

following the party belief that a loyal

man of any color was more entitled

to vote than a white Copperhead.

Besides, the Morning Journal stressed,

Ohio had a voting population of 470,000

while there were estimated to be

only 4,000 Negro males over twenty-one.

The issue was therefore essen-

tially a moral one without too much

political risk.13

|

GOVERNOR RUTHERFORD B. HAYES 61 |

|

|

|

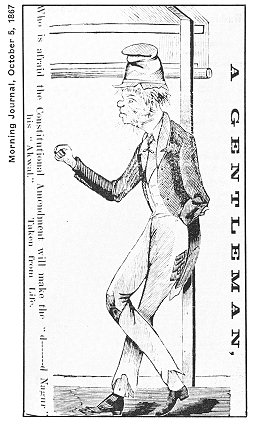

A pro-Negro suffrage cartoon The Democratic nominee was a man to be reckoned with, regardless of the issues and strategy. Allen G. Thurman of Chillicothe and Colum- bus was a southerner married to a Virginian. He had no war service, but was not considered a Copperhead. Former congressman and chief justice of the state supreme court, Thurman was cloaked in statesmanship that won him the nickname "Old Roman." Even though he was a formidable ad- versary, he was saddled with a party slate composed of non-veterans. Thur- man's tactic was to discredit the Re- publican-controlled Congress, particu- larly for the war debt it had amassed and for the harsh Reconstruction measures it had enacted.14 |

Even before Hayes left the halls of Congress, the Republicans began their attack on Thurman. N. A. Gray of Olmsted, former editor of the Cleveland Plain Dealer, opened the campaign on July 17 with a scurrilous diatribe in print against the Democratic candidate and his alleged southern sympathies during the war. Hayes, a relative newcomer in the political arena in the post-war era when a man was judged in terms of his participation for the Union cause, had an advantage over the more experienced "Old Roman" in this respect. Even so, the campaign was fought over issues rather than on a personal basis by the two candidates. Their partisans, however, left no stone unturned. The Democratic papers charged that Hayes, "the mogul candidate," was a large stockholder in a New England woolen mill and had therefore cast his vote in Congress to raise the tariff on wool by one cent a pound.15 The accusation was emphatically denied by Republican support- ers, and the attempt to discredit came to naught. The suffrage issue brought into the battle popular men of letters in Ohio. "Petroleum V. Nasby," the creation of the Toledo newspaperman David Ross Locke, was of incalculable aid to Hayes and his cause. In his widely circulated columns, Locke had Nasby assume the stance of a bigoted Democrat. He then proceeded to reduce his viewpoint, real or assumed, toward race to absurdity. Coates Kinney, bard of Xenia, also took the stump |

|

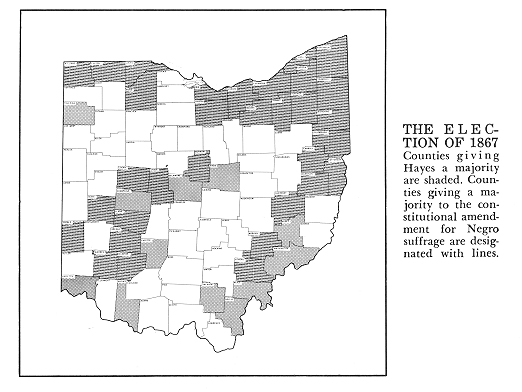

62 OHIO HISTORY in Hayes's behalf. But Donn Piatt, a lawyer and poet, wrote articles for John James Piatt's newspaper at West Liberty in support of Thurman. His political essays were also widely distributed.16 In spite of hard work that included at least eighty-one major speeches by Hayes, the election returns were a keen disappointment to the Republicans. While Hayes won the office of governor by 2,983 votes out of a total of 484,227 cast, the Negro suffrage amendment went down to defeat by 38,227 votes. Even more disappointing, the Democrats also won, by a majority of one in the state senate and seven in the house. Had it not been for the pro-Hayes activity of the newly formed Grand Army of the Republic in crucial counties such as Lucas, Muskingum, and Noble the governor's office might have been lost as well.17 New York newspapers summarized the results with expected partisan viewpoints, for the election had been closely watched nationally--not be- cause Hayes was a candidate, but because of the suffrage amendment. The Times noted that "The elections indicate no increased confidence in the Democratic party, but simply a reaction against extreme acts and measures of the Republican party." The World informed its readers, "The election is an indignant and unanimous veto of the policy of the party in power." The Commercial called the election "a verdict which ends Chief Justice Chase's aspirations for the Presidency and terminates Ben Wade's career."18 For the moment Ohio Republicans took solace in the fact that its staunch candidate would be in the governor's office. |

GOVERNOR RUTHERFORD B. HAYES 63

The Governor-elect busied himself before

his January inauguration in

putting his personal affairs in order

and in finding a Columbus residence

for his family. He rented a house at 51

East State Street.19 Late in Decem-

ber, he began the process of screening

applicants for key appointments.

Power of appointment along with that of

pardon and parole were about

the only executive functions permitted the

state's governor under the Ohio

Constitution of 1851.20 Secretary of

State Smith had indicated his intention

to resign in January, and there were

also a few key staff appointments to be

made at once, including the person to

work as the Governor's private secre-

tary. Unfortunately for Hayes, word of

his activities reached the ears of

William Henry Smith, who, as much as any

other individual, had put him

in the State House. Smith chided Hayes

for making appointments without

consulting him. The Governor replied on

January 7 that he had made but

one appointment and would make no others

until he talked with the Sec-

retary.21 The unpleasant

episode was resolved to the satisfaction of Smith,

but the incident gave Hayes a preview of

trouble to come over patronage

appointments.

In his last message to the newly

convened Fifty-eighth General Assembly,

Governor Cox on January 6, 1868, urged a

broad legislative program: estab-

lishment of an agricultural and

mechanical college, creation of the office

of county superintendent of schools,

distribution of state school funds pro-

portionately according to the number of

pupils in actual attendance, con-

struction of a reform school for girls

as well as an intermediate prison to

separate young offenders from hardened

criminals, revision and codifica-

tion of the criminal laws, display of

the governors' portraits in the State

House, reactivation of the office of

commissioner of immigration to recruit

labor, and the recommendation for a

geological and insect pest survey of

the state.22 The details for

the program were presented by Cox apparently

without consultation with the

Governor-elect.

A few days later, Governor Hayes

delivered his inaugural address in the

State House rotunda in front of the

giant canvas, "Perry's Victory." He

proffered no new or challenging program

to the Democratic legislature

except to endorse Cox's message. Hayes

reviewed the Negro suffrage, bank-

ing and currency issues, which he

dismissed as being of national concern,

but urged that the next constitutional

convention should grant the Negro

the right to vote. He reported that the

state debt was under control, taxes

were in proportion to actual value of

property, and that Ohio need not

concern itself further with public

works. Above all, when it became ap-

parent early in January that the

legislature might withdraw Ohio's 1867

ratification of the Fourteenth

Amendment, Hayes pleaded caution on the

part of the legislature until another

public referendum could be held. To

the General Assembly, he urged the

avoidance of "the evil of too much legis-

lation"; and recommended the

watchwords "economy, wisdom and pru-

dence."23

It was soon apparent to the new Governor

that the Democratic legisla-

ture would not heed his advice. For the

next several months he appeared

to withdraw from the active political

arena. He wrote his Uncle Sardis on

64 OHIO HISTORY

January 17, "I am enjoying the new

office. It strikes me at a guess as the

pleasantest I have ever had. Not too

much hard work, plenty of time to

read, good society, etc., etc." He

assumed the task begun by William Henry

Smith and Governor Cox of commissioning

copies of the portraits of former

governors to be made. The idea had been

authorized by legislative resolu-

tion in 1867 and had been implemented by

Smith. Hayes sat for his own

portrait by Columbus artist John Henry

Witt, who frequently had painted

copies of the portraits of past

governors in his 81 South High Street studio.

The Hayes portrait reflected the

Governor's "easy manner, pleasant hand-

shake, general genialiity."24 Its

whereabouts today is unknown.

Hayes attended the Republican national

convention in May. In June, to

prepare for his first major public

address since the inauguration, he spent

considerable time drafting a Fourth of

July speech for delivery in Youngs-

town. The speech contained a reference

to the need to care for widows and

orphans of Civil War veterans. This

endorsed a pledge that the Ohio Grand

Army of the Republic had made at its

January convention in Cincinnati.25

But Hayes had no specific recommendation

as to how such undertakings

should be financed. He made no reference

to Negro suffrage and had made

none since the legislature had acted to

rescind Ohio's ratification of the

Fourteenth Amendment.26

Hayes resumed active political

leadership in September and October by

campaigning in behalf of the Republican

candidate for secretary of state

in the mid-term election of 1868. Boldly

invading Democratic territory as

well as electioneering in the safe

Republican counties in the northern half

of the state, he spoke often, and on

election eve made his final address in

Cincinnati. Throughout the campaign, a

Hayes program for the state failed

to develop; he kept to the dictum:

"That government is best which governs

least." Yet his exposure to the

problems of the day during the campaign

certainly helped him to shape a program

soon to be announced. When a

Cincinnati riot in October elicited

adverse local reaction because of state

inaction, Hayes stood by his Jeffersonian

principles by privately enunciat-

ing his conviction that "the

governor can [not] nor ought 'to prevent

breaches of the peace . . . .' If there was an insurrection or

mob which civil

authorities could not control, I could

call out the military (if there was

any?) but it is the business of the civil

authorities to take care of 'breaches

of the peace.' The governor has no civil

authority."27

After meeting 134 days during the first

half of 1868, the legislature re-

convened on November 23 for a special

session. Governor Hayes addressed

both houses, presenting for the first

time a modest program. He urged again

the enactment into law of certain

matters which Governor Cox had re-

quested, particularly the creation of

the office of county superintendent of

schools and a geological survey. To

these he added requests of his own for

laws to revise assessment, taxation, and

the state accounting systems; to build

a fireproof lunatic asylum replacing the

Columbus home which had burned

on November 18 with the loss of six

lives; to inspect all state structures

with the view of fire prevention; to

appoint five commissioners to seek

ways to stamp out the Texas cattle fever

which was infecting Ohio herds;

GOVERNOR RUTHERFORD B. HAYES 65

and to prevent election fraud by

insuring minority representation on elec-

tion boards, voter registration, and a

cessation of the practice of "coloniz-

ing" or repeating voters.

This embryonic program composed of

recommendations for immediate

state needs had little effect on the

lawmakers and barely pleased the Gov-

ernor's supporters, not for what he

said, but for what he left out. The

Morning Journal editorialized: he "has narrowly escaped the

opposite ex-

treme [to that of verbosity] by leaving

us too much to our own good devices

in matters we would have been glad to

receive the benefit of suggestion."28

The long and expensive sessions of the

Fifty-eighth General Assembly and

its acts repugnant to Republican policy

provided Hayes with his 1869 cam-

paign strategy. The Democrats, thirsting

for power after a long drouth,

had enacted a large body of law filling

two volumes. Major laws included

the means to maintain and improve rural

roads, new municipal and crim-

inal codes, broader powers for local

subdivisions to issue bonds for public

works, regulation of insurance

companies, railroads and medical practi-

tioners, creation of an Ohio Geological

Survey, the authorization to con-

struct a new Central Ohio Lunatic

Asylum, election reform laws, and a

host of other much-needed domestic

legislation after years of concern for

war measures.29

Governor Hayes, however, singled out

only especially controversial acts

with which to taunt the Democrats in the

forthcoming election. These acts

included the rescinding of an 1867

resolution to ratify the Fourteenth

Amendment; the "Visible

Admixture" law, which prohibited suffrage to

any person having "a distinct and

visible admixture of African blood"; and

acts to "Preserve the Purity of

Elections," which disenfranchised disabled

veterans in the national asylum in

Dayton and prevented college students,

prone to Republicanism in that age, who

were non-residents in tile county or

city of their schooling, from voting.

Clearly, Negro suffrage would play a

part in the campaign of 1869 also.

Renominated by acclamation on June 23,

Hayes endorsed the five-plank

Republican state platform to support the

Grant administration: to endorse

Grant's inaugural address; to support

Republican reconstruction policies

and the adoption of the Fifteenth

Amendment; to condemn the Democratic

legislature for reckless expenditures,

failure to enact new assessment and

tax laws, and for its attempts to

disqualify certain voters; and, as the only

positive measure, to establish a

soldiers' orphans' home.30

His campaign for reelection was launched

at Wilmington on August 12

by a long and tedious speech. He

defended the fiscal policies of the new

Grant administration and its efforts to

retire government bonds without

new taxes. He bemoaned the fact that

Ohio tax revenues had doubled be-

tween 1863 ($11,859,573) and 1868

($21,006,322). He reported a reason-

able state debt of ten million dollars,

but lamented the total city and coun-

ty debts of about fifteen million

dollars. He urged lower taxes so that in-

dustry and citizens would not be driven

from the state in time of recession

or high interest rates. "The last

General Assembly," he asserted, "was in

session too long [260 days] and too

often -- that its legislation was exces-

66 OHIO HISTORY

sive, expensive, unnecessary, and in

some instances oppressive. We say

that it authorized expenditures, local

debts, and local taxes, in a manner

and to an extent that endangers the

prosperity of the State. We therefore

maintain that there ought to be a

thorough, and sweeping reform in the

Legislature. . . . long sessions are the

fruitful source of all sorts of abuses."

In conclusion, he urged state

construction and maintenance of an orphans'

home, basing his recommendation upon a

recently published estimate that

there were 150,000 to 200,000 soldiers

orphans as inmates of various county

infirmaries or subsisting on township

charity in 1868. A bill (S.B. 343)

to create the home, in spite of

bipartisan support, had been tabled in the

senate by a single vote.31 At

last, Hayes's philosophy and platform seemed

to be evolving.

To oppose Hayes, the Democrats before

July 7 had wildly considered

nine candidates until General William S.

Rosecrans, then a California resi-

dent, was chosen. A party platform of

thirteen planks praised the previous

legislature, supported greenbacks, urged

workmen's legislation, and damned

Hayes's attacks on the legislature as

"false in fact, malicious in spirit, and

unworthy of gentlemen occupying elevated

positions."32

The campaign pitting two prominent Civil

War generals was viewed by

impartial observers as very close until

Rosecrans unexpectedly withdrew

as the Democratic candidate for governor

on August 7. Four days later, a

reluctant George Pendleton of Cincinnati

accepted the nomination. Re-

publican hopes soared as a result of

Democratic adversity; Hayes now had

a less popular adversary. Although

Pendleton's enemies conceded he was

polished, composed, tactful, and adroit,33

it was possible for Republican

partisans to draw a sharp contrast

between Hayes, the valiant general, and

Pendleton, the Peace Democrat. While

Hayes was "crowning the banners

of Ohio with glory, Pendleton was doing

all he could to drape these ban-

ners in white in token of

surrender," a Republican spokesman claimed.34

Hayes campaigned chiefly in Union and

doubtful counties with a less

strenuous schedule than in 1867. He won

by 7,501 votes. Tile voting pat-

tern was similar to that of 1867 except

Hayes lost his home county, Hamil-

ton, together with Brown and Knox. He

picked up majorities, however, in

Scioto, Lawrence, and Madison counties.35

The Hayes victory speech was delivered

from a balcony of the American

House in Columbus. He termed his

reelection a decision of Ohioans to

stand by the Republican plan for

Reconstruction and to complete it by

ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment.

How the legislature would react

to his leadership remained in doubt.

While Republicans gained a small

majority in the senate, the house

was now composed of 53 Republicans and

54 Democrats, five of whom

might be persuaded to vote for

Republican measures. But a reform ticket

in Hamilton County had elected five

independent Republicans pledged to

neither party. These mavericks

controlled the balance of power, and the

house was organized along bipartisan

lines.36

Early in December 1869, Hayes began to

assemble ideas for his 1870

legislative program. From E. C. Wines,

of the New York State Prison As-

GOVERNOR RUTHERFORD B. HAYES 67

sociation and author of its important

1868 report,37 he solicited further

information on prison reform. Hayes

indicated he would not make any

"sudden or sweeping reform"

but desired to encourage the formation of

"correct opinions and hope that

gradual but steady advance may be made

towards a reformatory system,"

particularly to implement Cox's earlier

request for an intermediate prison.38

The Hayes legislative message of January

3, 1870,39 reported a reduction

in the state debt of nearly a million

dollars to $9,855,938. Since a tax in-

crease of 44% had burdened Ohio

taxpayers since 1867, new laws to pre-

vent increased taxes by implementing

fiscal reforms in accordance with a

March 18, 1867 law were recommended. The

Governor cautioned the leg-

islature about its propensity to hold

long sessions: urged adequate, fixed

salaries for all public employees; and

recommended curbs on the powers

of county commissioners and municipal

officials to levy taxes and contract

debts. "All large expenditures

should meet the approval of those who are

to bear the burden." Let a majority

of the voters approve public levies, or

limit the rate of taxation which may be

levied locally, Hayes pleaded.

His suggestions for penal reform were

made for the benefit of young

inmates, as two-thirds of all the

prisoners were under thirty. He reported

that the present system was defective in

that the young mingled with hard-

ened prisoners and the administration

failed to educate convicts in habits

of thrift and self control. His

proposals included a new prisoner classifica-

tion system according to age and the

construction of a new state penitentiary

or the enlargement of the present one.

In education, Hayes again asked for the

office of county superintendent

of schools, a codification of school

laws, and the substitution of township

boards of education for the existing and

overlapping system of township

and subdistrict boards.

He urged increased powers for the Board

of State Charities, but declined

to salary them. He called the housing

and treatment of the insane "atro-

cious," reporting that 900

incurably insane persons were lodged in county

infirmaries and another 100 in county

jails, necessitating more space be

added to existing asylum structures. He

further asked for an appropriation

of the necessary funds to build an

asylum for tile incurable alcoholic to be

administered along the lines of the New

York plan, a provision which Mrs.

Hayes endorsed. Still considering

indigent persons, the governor said that

the state should find the means to

support, house, and educate all orphans

who need this care.

Next, the Governor gave his support to

the establishment of a land grant

agricultural and mechanical college.

This was the first time in his admin-

istration that he had done so. During

the war a fund had been created by

the sale of land script issued to Ohio

by the federal government. On Jan-

uary 1, 1870, the fund totalled

$404,911. Under the provisions of the grant,

the state was bound to provide not less

than one college on or before July

2, 1872. The principal objective of the

institution would be to teach agri-

cultural and mechanical sciences, the pure sciences,

classical studies, and

military tactics. Governor Cox had urged

the legislature to decide on the

68 OHIO HISTORY

use of the fund in his January 1868

message,40 in which lie had reported

that for four years the issue had been

debated only. The problems which

had stood in the way of founding the

college were the selection of a site

and the belief of Republicans in some

quarters that it was ridiculous to

give farmers and mechanics a college

education.41 Hayes realized that now

was the time to act if the fund were to

be utilized.

Finally, he requested the enactment of

voter registry laws to "purify"

elections and minority party

representation laws for election boards. He

offered no method of accomplishing these

goals, however. He stressed the

immediate need to repeal voting

restrictions placed by the last legislature

on students, institutionalized veterans,

and persons of mixed blood. The

Governor also strongly advocated the

ratification of the Fifteenth Amend-

ment to the United States Constitution.

The new Hayes program, the first

he had espoused bearing his own ideas

concerning state needs, fared well

in the legislature.

Hayes took the oath of office for the

second time on January 10, 1870,

once more against the backdrop of

"Perry's Victory." His address was com-

posed almost entirely of words of advice

to the forthcoming state constitu-

tional convention. He suggested that

railroad construction should be speeded

by repeal of the constitutional

provision which prohibited the legislative

branch from authorizing any political

subdivision to give aid to any com-

mercial enterprise. End the spoils

system, he advocated, by making most

state offices non-political; place

appointments and retention in office upon

merit and experience. He expressed his

belief that judges should be ap-

pointed to long terms with adequate

salaries to discourage bribery in urban

centers.42

Thus in a single week, Governor Hayes

enunciated more policy and

political philosophy than he had during

his entire first term. While still

paying lip service to the Jeffersonian

doctrine of that government governs

best which governs least, he was making,

early in 1870, bold and idealistic

long-range proposals in the science of

government, recommendations which

have not been fully attained a century

later. His program was practical

enough, however, to be implemented at

least in part during his second term.

Specifically, the legislature enacted

into law the Hayes recommendations

for a fixed public employee salary

schedule, construction of a Girls' Indus-

trial School at White Sulphur Springs,

an enlargement of the state peni-

tentiary, a graded prison system, an

increase of responsibilities for the State

Board of Charities, a board to select

the site for and create the Ohio Agri-

cultural and Mechanical College, a board

to build and govern a soldiers'

and sailors' orphans' home in Xenia, a

voter registration law, and the re-

peal of voting restrictions he had

requested. But it was Ohio's approval of

the Fifteenth Amendment on January 20

which gave Hayes his greatest

satisfaction. At a celebration in the

Columbus Opera House on April 13

marking the national ratification of the

amendment, Hayes declared: "The

war of races, which it was confidently

predicted would follow the enfran-

chisement of the colored people -- where

was it in the [local] elections of

GOVERNOR RUTHERFORD B. HAYES 69

Ohio last week? . . . There was barely

enough angry dissent to remind us

of the barbarism of slavery which has

passed away forever."43

Only in the making of appointments did

the public and the legislature

harass the Governor. No sooner had Hayes

resolved his difficulty with Wil-

liam Henry Smith on this subject early

in 1868, than still another differ-

ence arose in May between the two friends

concerning the appointment

of a state school commissioner. Hayes

had made a pledge to schoolmen

that lie would appoint their candidate

even if the former Secretary of State

disapproved. Smith then told Hayes to

hereafter "apply elsewhere for infor-

mation."44 Hayes

believed his only course with Smith should be one of

reconciliation.

Hayes's appointment of John S. Newberry

of Cleveland on April 21, 1869,

as the first state geologist won him the

enmity of the powerful Colonel

Charles Whittlesey, the state's leading

man of science. He abused Hayes

"terribly"45 because

Newberry, who had been appointed earlier to the

United States Geological Corps by the

Democratic Buchanan administra-

tion, at the time of his Hayes

appointment was residing outside of Ohio.

Both facts fanned Whittlesey's fire.

Hayes applied a single test in making

most of his appointments: had the

candidate been a loyal Union man during

the war? In his victory speech of

October 14, 1869, he had interpreted his

reelection as a public desire "to

refrain from electing to public office

any person against the country during

war."46 He made certain

to guarantee minority party representation on all

state boards, but he tried to make sure

that he appointed only those Demo-

crats who had actively supported the

Union. The loyalty of the appointees

was not always easy to ascertain, and

the first few months of his third term

were troubled by poor patronage

decisions.

The greatest appointment crises which

Hayes faced occurred in connec-

tion with the ratification by tile

senate of his appointees to the new board

of the Soldiers' and Sailors' Orphans'

Home and the appointment of the

superintendent of the State House.

Senators present at the session of April

16, 1870, were evenly divided seventeen

to seventeen. In secret session,

the senate was deadlocked; Democrats

criticized the Hayes nominees because

they were all former soldiers, too many

belonged to the G.A.R., and not

enough were Democrats [one].47 The Governor and his clerks waited in

their offices throughout tile night for

a decision. At 2:30 A.M., the appoint-

ments to the board of the Orphans' Home

were approved, but the State

House superintendent nominee was

rejected. The Governor immediately

offered a substitute nomination, and at

5:00 A.M., on Sunday, the legisla-

ture adjourned with all appointments

confirmed.48

Much has been made of the Hayes policy

of appointing minority party

representatives to state boards and

commissions. The truth is, tills practice

was born of necessity since Hayes did

not have the opportunity of work-

ing with a clear Republican majority in

both houses until his third term.49

Reviewing the General Assembly of 1870

with its dramatic ending, the

Governor praised the legislature's work

done in a "longer session than was

70 OHIO HISTORY

required, longer than I had hoped."

With legislative matters settled for a

while, Hayes turned his attention to

affairs of a more personal interest.

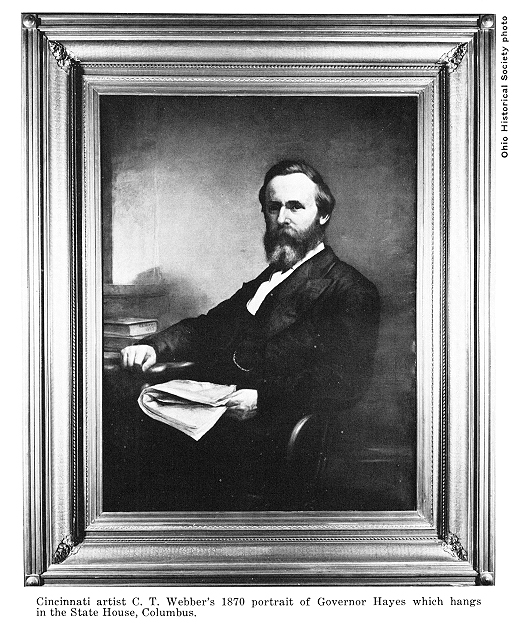

C. T. Webber of Cincinnati painted his

portrait that was to be hung along

side of those of his peers, and he

continued to make additions to the State

House portrait collection. On July 4,

1870, he laid the cornerstone for the

new Central Ohio Lunatic Asylum. The

event was hailed as the beginning

of a new era in the treatment for Ohio's

insane.50

In September, the Governor campaigned

for the party ticket in eastern

and northern Ohio. He closed the canvass

on October 8 with a major ad-

dress in Cincinnati. In it he praised

America's neutral position in the

Franco-Prussian War and the Grant

administration's policy of favoring gold

over paper in the payment of the

national debt. In his first well-reasoned

and erudite explanation of current

Republican fiscal policies, Hayes ex-

plained, "Any man of sense knows

that just in proportion to the gap be-

tween the value of gold and the value of

paper money, in that proportion

is your currency unsound, your business

disturbed, and labor in danger of

not receiving its full reward. Now this

ugly gap that was between the value

of gold and greenbacks before Grant's

election has been partially closed-

is getting a little narrower all the

time--and since the commencement of

the present administration the people

have gained sixty millions of dollars

by the increased value of the

currency."51

Meantime family history became a hobby

of Hayes early in 1870, and he

pursued the search for genealogical

records with increasing interest through-

out his second term. A recurring eye

infection during the last year of office

in the second term offered him an excuse

to travel for rest and relaxation,

to seek further ancestral facts, and to

pursue new business ventures. His in-

terest in contemporary Ohio politics

waned, as he reported to a friend on

March 1, 1870, "I too mean to be

out of politics. The ratification of the

Fifteenth Amendment gives me the boon of

equality before the law, ter-

minates my enlistment, and discharges me

cured."52

Time and again to his political

correspondents or in his Diary, Hayes re-

marked how the great domestic issues of

the day had consumed his energy

--freedom for the slaves, unity of the

nation, Negro suffrage.53 It was almost

as if Hayes as governor served merely to

achieve Negro suffrage and tidy up

Ohio after the war. He seemed totally

uninterested in or unwilling to grap-

ple with the new issues of post-war

Ohio, issues arising from the growth of

cities, the industrial revolution, the

rapid changes in transportation and

communication, and woman suffrage, with

all the attending social, politi-

cal, and economic ills. During the final

year of the second term in office,

Hayes in all respects became backward

looking in politics. His disillusion-

ment with corruption and poor

administration in Washington, his pre-

occupation with family history, and his

desire to improve his personal

finances made him a veritable schoolboy

waiting anxiously for the summer

recess.

On January 4, 1872, Hayes placed a statement

in the Ohio State Journal

to the effect he would not be a

candidate for Senator, "either in or out of

caucus." To a friend he wrote in

March, "I go out of politics with tile end

?? of the colored people -- where was it

in the [local] elections of

?? of the ?? people -- where was it in the [local] elections of

GOVERNOR RUTHERFORD B. HAYES 71

of this term. The old questions interest

me so much that the new ones

seem small." But during the last

few weeks of his second term Hayes was

disturbed by nocturnal visitors sounding

him out as a senatorial candidate.

Privately, he may have desired the

attention and the office, but publicly he

would not declare for it in deference to

the incumbent, John Sherman.

Again, his reticence would in the future

stand him in good stead. Sherman

would have occasion to repay the debt.54

Ensconced as a country squire at Spiegel

Grove in Fremont, the estate

he had inherited from his uncle, former

Governor Hayes enjoyed life to the

fullest until early in 1875. Then an

Ohio Republican party caucus unani-

mously agreed to boost Hayes for a third

term, "a feather," he allowed,

"I would like to wear." Yet to

all correspondents, he typically refused to

entertain the idea of his candidacy

publicly. Tile next few months Hayes

weighed in his mind and recorded in his Diary

the reasons for and against

acceptance. On the negative side, he

continued to be interested in provid-

ing a substantial estate for himself and

his family. His personal debts had

approximated two years before $46,000,

which, when paid, would give him

a net worth of about a half million

dollars. He had also become concerned

about his health, having coughed up

blood on occasion and having fre-

quently been bothered by summer colds, perhaps

an allergy. He was dis-

turbed, too, by the corruption, unwise

appointments, and "ultra measures"

directed toward the South by the Grant

administration. More importantly,

there was talk about a third term for

Grant--all liabilities for any Repub-

lican gubernatorial candidate of Ohio.

On the positive side, however, was the

enticing possibility, which friends

were prone to remind him and which some

party leaders firmly believed,

that if Hayes could win a third term as

governor, he would then be prime

presidential timber.55

The Republican state convention met in

Columbus on June 2 and nom-

inated Hayes over Judge Alfonso Taft of

Cincinnati, 396 to 151. Taft

then withdrew, making the Republican

choice unanimous. Hayes at first

declined the nomination, but later,

lured as any man might be by the pros-

pect of the presidency, accepted "to

rebuke the Democracy by a defeat for

subserviency to Roman Catholic

demands."56

The question of separation of church and

state along with the then in-

famous Geghan bill, which had passed the

1874 session of the legislature,

was to be the dramatic issue of the

Hayes campaign against incumbent Dem-

ocratic Governor William Allen. Tile

Geghan bill merely permitted equal

opportunity for religious worship for

persons of all denominations in public

jails and asylums, but it was considered

to be a sinister plot on the part of

Irish and German Catholics in the

Democratic party to secure state spon-

sorship of sectarian religious education

in the public schools, to win public

support for parochial schools, and to

take over the Democratic party in Ohio.

Early in 1870, while Governor, Hayes had

stated his general position con-

cerning religion in the schools. In a

letter to a Cincinnati correspondent,

he said, "We must not let them push

religion out of the schools, but we

72 OHIO HISTORY

must avoid forcing it on anybody.

You may ask, How are these two things

accomplished? Well, it is easier to do

the thing than tell how to do it."57

With the heated discussion among

Protestants over religious questions

in 1875, Hayes was quick to take another

tact. He now made the complete

separation of church and state his major

issue. The nominating convention

inserted such a plank in the platform:

"Free education, our public school

system, the taxation of all for its

support, and 'no division of the school

fund.' " Religion in the schools

and institutions of the state had always been

accepted if Protestant in form and

content; Catholic observances or public

support, direct or indirect, for

Catholic education was unthinkable to the

Republicans. Repeatedly, at the

beginning of the campaign, Hayes had in-

structed A. T. Xikoff, his campaign

manager, to prepare a pamphlet on

the Geghan bill and the school question

which he believed would have an

impact on Protestant voters.)58

Hayes opened his campaign in Marion,

Lawrence County on July 31 with

a major speech which he would reuse in

other numerous appearances until

election day. He first argued against

the Democratic plank to abandon the

gold standard in favor of greenbacks

which to Hayes was the second most

important issue of the campaign. Sound

money principles remained a na-

tional Republican objective, and Hayes

and his supporters simply reaffirmed

the policy. He then traced in great

detail the dangers inherent in the

Geghan bill by showing the threat it

posed to the constitutional doctrine

of the separation of church and state, a

doctrine he claimed was being chal-

lenged by the Catholic Democrats. His

appeal was intended to arouse

Protestant prejudice and win

non-Catholic Democratic votes. "Government

nor political parties ought to interfere

with religious sects,"59 he exclaimed.

A. T. Wikoff over-scheduled the Hayes

party. Often, Hayes, suffering

from summer colds, was forced to give

two to three major addresses a day,

an effort he deemed injurious to health.

Ohio was deluged by rain during

August causing floods that resulted in poor

attendance at political rallies.

Hayes pleaded with Wikoff to reduce his

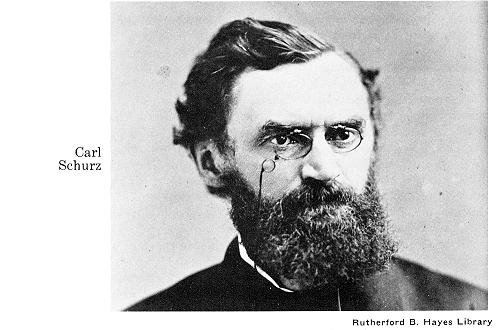

schedule. The colorful Carl Schurz

came to Ohio to aid the Republican

campaign on September 27. The Cin-

cinnati Euquirer charged that the

Republican state committee was paying

the speaker $10,000 to woo the German

vote. Schurz stressed tile danger of

inflation if the nation's monetary

system were taken off the gold standard.

Hayes was jubilant over the naturalized

German's participation which gave

the campaign national attention. But the

practical, vote-getting effect of

Schurz's intellectual speeches upon the

German laborer, shopkeeper, and

farmer was dubious except in Hamilton

County where Hayes received a

majority of 1.00 votes. Hayes won the

election by a mere 5,544 votes, even

less than his small margin in tile 1869

election. As soon as the results

were known, however, the loyal

Republican press touted him as a presi-

dential possibility."60

The inauguration on January 10, 1876,

was a grand affair marked by

cordiality between outgoing Governor

Allen and Hayes, both of whom had

not let the campaign destroy their

personal friendship. In his inaugural ad-

|

GOVERNOR RUTHERFORD B. HAYES 73 dress, Hayes directed his remarks almost exclusively to the legislature which was composed of a safe Republican majority of three in the senate and nineteen in the house. For the first time Hayes had some assurance that his recommendations would be heeded. |

|

His first concern was "profligate expenditure" by large cities and "munic- ipal misgovernment." He bemoaned the fact that the average city tax rate had risen 25% in the last four years and city indebtedness was up 190% in the same period. Without a keen awareness of what was happening to the rapidly growing urban areas, e asked the legislature to apply the same laws pertaining to state indebtedness to local political subdivisions. He asked for sinking funds for the cities by which they could pay off their debts in a planned and orderly fashion, and a tax rate limit, especially for large cities. The "cash system" he believed should be applied to local af- fairs. Hayes urged the reestablishment of his favorite agency, the Board of Charities, with unsalaried commissioners serving as watchdogs over penal, reform, and charitable institutions of the state. Yet he found no fault with the existing mode of operating these facilities. He joined ex-Governor Allen in recommending state participation in the national centennial celebration. Finally, he exhorted tile legislature: "Let your session be short."61 Hayes's wishes were respected only in part by the General Assembly. Its session was short; it repealed the Geghan bill; it abolished the office of comptroller of the treasury as a gesture to economy; it passed some laws limiting the taxing powers of municipalities. Otherwise it was generally an unproductive session.62 |

74 OHIO HISTORY

In the quiet period between the time of

his inauguration and his nom-

ination for President, Hayes gave

serious thought to the two most important

administrative powers given Ohio

governors: appointments and pardons.

He had experienced repeated rebuffs for

his bi-partisan appointments, a

practice deemed necessary in an effort

to secure both senate and party ap-

proval. Also, his party expected him to

appoint only staunch Union men

to state posts. Early in April 1876, his

appointment of a Democrat and a

Republican to the Dayton State Hospital

board caused a major flurry, and

a private apology from the Governor was

necessary. One of the men had

been a Copperhead, the other was a

libertine. In his Diary on April 11,

Hayes confided, "Some mistakes have

been made, but, on the whole, I have

been fortunate. One or two things I must

bear in mind. No man should be

finally determined on until the people

where he resides have been heard

from, after he is seriously talked

of, or nominated for the place."

Of all interests and responsibilities,

Hayes took the power of pardon

most seriously. His official

correspondence throughout his three administra-

tions concerned pardon cases more than

anything else. In April 1870, the

Cincinnati Gazette had severely

criticized Governor Hayes for commuting

the sentence of one Steinmetz, a Toledo

murderer. This event, his ex-

perience as a defense lawyer in

Cincinnati before the war, and his concern

for penal reform, prompted him to list

on April 11, 1876, his "rules" for

the "perplexing" task of

pardon-granting. He reminded himself to take time

to consider each case, to consider group

pardons as a unit, to pardon no

man not provided with employment or an

income, to release no man with

out a home or one of a friend who will

welcome him, and to listen to the

advice of the legal authorities on the

case.63 Rarely, in the past, had Gover-

nor Hayes applied all of these

considerations in granting pardons, perhaps

fortunately.

The origin of Hayes's concern for prison

administration and reform

stemmed from reading the first annual

report of the Board of State Chari-

ties of 1868 and the reports of E. C.

Wines, New York State correctional

officer. As governor, however, Hayes

evolved no comprehensive prison re-

form policies which might cost the

taxpayers sizeable sums of money. He

did continue to support the State Board

of Charities, but insisted it be un-

salaried and advisory only. His specific

recommendations concerning the

classification and separation of

prisoners at the Ohio Penitentiary had been

recommended earlier by the Board in

1868. His greatest contributions to

penal reform would come after his

retirement from public life.64

Upon leaving office in 1872, Hayes

listed in his Diary twenty-two contri-

butions he felt he had made to the state

during his first two terms. Among

these were seven which actually had been

proposals of his predecessor and

of William Henry Smith when Secretary of

State. Of these twenty-two con-

tributions, five were historical

projects designed to preserve, perpetuate,

and promote a knowledge of the past. But

of them all, both lasting and in-

consequential, only one action tested

his courage and convictions, demon-

strated his political fortitude. He won

against great odds, prejudice, and

GOVERNOR RUTHERFORD B. HAYES 75

popular disapproval tile right of Negro

suffrage in Ohio. He did it through

his personal popularity which in turn

affected the composition of the Ohio

General Assembly; and he did it at a

time when only a minority of Ohioans

approved.

The second major Hayes achievement was

the sum total of his enlight-

ened stand to transform penal

institutions into true reformatories and to

improve the care of mental patients and orphans--an equally

unpopular

position with that of Negro suffrage.

His success was not complete in this

respect, but he did help create a more

favorable climate of opinion upon

which his successors might build.

Rutherford B. Hayes earned tile sobriquet:

"The Good Governor."65

THE AUTHOR: Daniel R.

Porter is

Director, The Ohio Historical Society.