Ohio History Journal

WILLIAM D. ANDREWS

William T Coggeshall:

"Booster"of Western

Literature

Students of nineteenth-century America

have long been familiar with a type of person

that intellectual historian Daniel

Boorstin precisely labeled the "booster."1 Typically

he was a small-town, midwestern

newspaper editor or dry-goods entrepreneur,

anxious to make a killing for himself

and a reputation for his town--the order of

his desires was never clear. Promotion

was his method; the most insignificant occur-

rence in his town could assume, as the

object of his promotion, earthshaking impor-

tance. The arrival in his shop of last

year's best eastern finery or the erection of yet

another Gothic aberration on his town's

main street could be the occasion for inflated

praise intended to prove that

civilization had reached its zenith. Even though the

booster may be something of a bore, he

has not been without his defenders. It has

been argued, for example, that the

development of education, literature, and the

arts--what is commonly called

culture--came largely to America's heartland

through the efforts of promoters of this

type.

The achievements of Dr. Daniel Drake of

Cincinnati, the so-called "Franklin of

the West," have become legendary,

and his encouragement of the arts in early Ohio

is a matter of record. Less well known

than Drake's works are the efforts of a later

but equally dedicated literary booster

of the West, William Turner Coggeshall.2 Like

1. Daniel J. Boorstin, The Americans:

The National Experience (New York, 1965), 113-168.

On American literary boosterism see particularly

Robert E. Spiller, ed., The American Literary

Revolution, 1783-1837 (Garden City, N.Y., 1967) and Benjamin Spencer, The

Quest for Na-

tionality: An American Literary

Campaign (Syracuse, 1957). Two

informative essays on western

literary boosterism are Theodore

Hornberger, "Three Self-Conscious Wests," Southwest Review,

XXVI (1941), 428-448; and David Donald,

"Toward a Western Literature, 1820-60" in his

Lincoln Reconsidered (New York, 1956), 167-186.

2. Published sources of information on

Coggeshall include sketches in William Coyle, ed.,

Ohio Authors and their Books (Cleveland, 1962), 125; and Dictionary of American

Biography,

(New York, 1930), IV, 272-273. Both of

these rely on the information, provided by Coggeshall's

widow, in W. H. Venable, Beginnings

of Literary Culture in the Ohio Valley (Cincinnati, 1891),

109-110, 116-118, a less than reliable

source.

An important biographical source is the

Coggeshall Papers in the Ohio Historical Society.

The eight boxes of Coggeshall

manuscripts in this collection include important letters, drafts of

essays, and diaries for 1861, 1863,

1865, 1866, and 1867. Also, Ralph C. Busbey, son of

Coggeshall's daughter Emancipation

Proclamation Coggeshall Busbey, excerpted material from

his grandfather's diaries for a series

of pieces published in the Columbus Dispatch Magazine,

October 26, 1958, November 9, 1958,

November 23, 1958, November 30, 1958. The first provides

biographical information on Coggeshall,

his wife and their daughter Emmancipation Proclama-

tion, nicknamed "Prockie." The

last three deal with Coggeshall's observation on Abraham

Lincoln's journeys through Columbus,

first on his way to his inaugural and later on the passage

of his body back to Springfield,

Illinois, for burial.

Mr. Andrews is Assistant Professor of

English, The Ohio State University.

William T. Coggeshall 211

Dr. Drake and many other westerners of

his day, Coggeshall engaged in a staggering

variety of activities. He was a

newspaper and magazine editor, writer of novels and

historical sketches, public lecturer of

wide acclaim, politician and political confidant,

secret agent in the Civil War, and, at

the end of his career, a diplomat. But only his

efforts to promote literature in the new

American West (which he identified in 1860

as Ohio, Kentucky, Indiana, Illinois,

Michigan, Missouri, Minnesota, Wisconsin,

Iowa, and Kansas) are the subject of

this essay. Coggeshall was born in Lewistown,

Pennsylvania, on the 6th of September

1824. At age eighteen he moved to north-

eastern Ohio, settling in Akron in 1842.

There he published for two years (1844-45)

a temperance paper called the Cascade

Roarer.3 In 1845 he married Mary Maria

Carpenter, and two years later the

couple moved to Cincinnati, where Coggeshall

later became editor of The Western

Fountain, a newspaper established in 1846.4

Coggeshall's journalism career in

Cincinnati was interrupted in 1851 when he

joined the Hungarian patriot Louis

Kossuth on his tour of America. Serving as guide,

secretary, and reporter, the

enterprising journalist also attempted to write a biography

of Kossuth.5 Later, in the

autumn of 1852, after the manuscript of the biography

was rejected by a New York publisher,

Coggeshall reentered the Cincinnati news-

paper world, becoming the assistant

editor of the year-old Daily Columbian, a news

and business paper with circulation of

5,000 in 1854.6

By August of 1854 Coggeshall became

involved in a more literary enterprise, the

publishing of the Genius of the West,

a Cincinnati magazine that consciously pro-

moted local literature. This publication

had been started in October of 1853 by

Howard Durham, a native of New Jersey

who had settled near Cincinnati in 1847

to conduct business as a shoemaker.

Durham was shortly joined on the Genius by

Coates Kinney, a local poet who had just

left his position as a professor at Judson

College in Mt. Palatine, Illinois.

Apparently Durham and Kinney quarreled over

money, and in the late summer of 1854

Kinney bought out the magazine's founder

and took into partnership William

Coggeshall. Durham then established in January

of 1855 a rival publication, The New

Western, the Original Genius of the West,

but after a few issues he abandoned it.

Coates Kinney also soon sold out his share

in the Genius, leaving Coggeshall

the editor and chief proprietor by June 1855.7

Under his direction the Genius promoted

regional literature, publishing the work

of young western poets like the Cary

sisters, Alice and Phoebe, W. D. Gallagher,

Sarah Bolton, and the Fuller sisters,

Metta and Frances. Orville James Victor, who

later became the publisher of Beadle's

Dime Novels, contributed historical sketches

and book reviews.8 Even

though the magazine achieved genuine literary merit, it was

3. Samuel A. Lane, Fifty Years and

Over of Akron and Summit County (Akron, 1892), 225.

4. Venable's report (pp. 109-110) that

Coggeshall also worked for the Times and the Cincinnati

Gazette cannot be verified from the newspapers themselves. The

details of his journalism career

in Cincinnati are as confused as the

newspaper situation itself there, where papers came into

existence for brief periods and then

disappeared or merged with others. It is at least clear that

Venable's account is not trustworthy.

5. The unpublished manuscript is in Box

6 of the Coggeshall Papers. The title page says,

hopefully, "New York. 1853."

The publisher's letter turning down the piece is dated December 4,

1852.

6. Coggeshall was also probably

associated with a Cincinnati paper called the Commercial

Advertiser, no copies of which still exist. The Daily Columbian was

printed by the firmly

established weekly Columbian and the

Great West, which had a circulation of 75,000 in 1854.

See Columbian and the Great West, November

11, 1854.

7. Venable, Beginnings of Literary

Culture in the Ohio Valley, 109-110.

8. Editor of the Sandusky Daily

Register, Victor was a good friend and frequent correspondent

of Coggeshall. Twenty-eight of

Coggeshall's letters to Victor are in Box 1 of the Coggeshall

Papers.

|

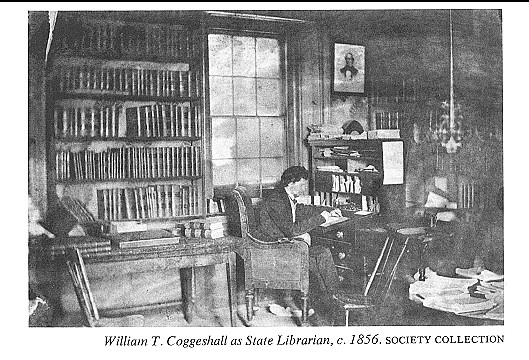

still decidedly not successful in the colder terms of finance since it was not supported by western readers. As early as May of 1855 Coggeshall complained to his friend 0. J. Victor that the publication was in trouble. In October of the same year he wrote to Victor that "sometimes I'm almost discouraged with the Genius in the little interest it awakens among subscribers, but I am determined to hold on this year-- then we shall see what we shall see."9 In need of money to care for his growing family, Coggeshall secured an appointment from Governor Salmon Chase to the post of Librarian of the State of Ohio in May of 1856. The Genius was then sold to George True, who published it only until July of that year.10 Coggeshall continued as State Librarian under Governor William Dennison, making the position an important platform from which to encourage western literature. During this period he was at work on the anthology for which he is best known, The Poets and Poetry of the West. In 1858 and 1859 he also edited the Ohio Journal of Education, later renamed the Ohio Educational Monthly. In 1862 he purchased the Springfield Republic, which he edited until 1865, when he returned to Columbus to become editor of the Ohio State Journal.11 In both papers concerted efforts were continued to promote and publish western literature. Known and respected also in political circles, Coggeshall was asked to serve the Union as a secret agent during the first year of the Civil War. As a newspaper correspondent, he carried orders through enemy lines and performed other unspecified duties, the consequence of

9. Letter to O. J. Victor, October 9, 1855, Coggeshall Papers. See also letters of May 23, and August 20, 1855, which further develop Coggeshall's views about the financial difficulties involved in the publication of the Genius. 10. Venable, Beginnings of Literary Culture in the Ohio Valley, 109-110. 11. As editor of the Republic, Coggeshall was one of a number of Ohio journalists who accom- panied Governor David Tod to the dedication ceremonies of the Gettysburg Soldiers' Cemetery in Pennsylvania on November 19, 1863. His report is in the Republic, November 30, 1863. On Coggeshall's participation see Frank L. Klement, "Ohio and the Dedication of the Soldiers' Cemetery at Gettysburg," Ohio History, LXXIX (Spring 1970), 87, 93. |

|

|

|

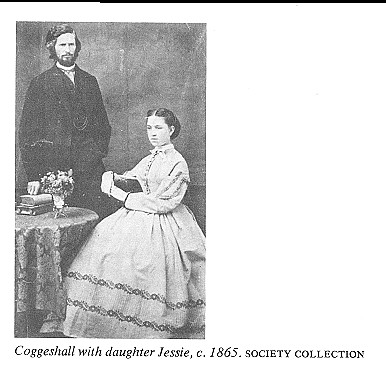

which was the failure of his health. The beginnings of tuberculosis (consumption) forced him to resign from the Journal to seek less taxing employment. He became private secretary to Governor Jacob D. Cox, and through political friends was appointed in 1865 as American minister to Ecuador. Coggeshall, accompanied by his fifteen year old daughter Jessie, arrived in Quito on August 2, 1866, to take up his new position. Before long, the Ohioan became bored and longed for the "Sins of Civilization," such as opera and theatre. Unfor- tunately, he was particularly sensitive to the high altitude and cold nights which aggravated his consumption, and one year to the day after his arrival in South America, Coggeshall died of the disease that had been plaguing him for several years. Because as a non-Catholic he could not be buried in consecrated ground in Quito, his body was stored for a time in a warehouse before being interred in a newly established cemetery in the capital city. Detained by red tape, Jessie was not able to start for home until December, and she died in Quayaquill of yellow fever before she could leave Ecuador. She was interred in the Protestant Cemetery in that coastal city. In the winter of 1869 the United States Congress appropriated funds to bring both bodies back to Ohio for burial. The two were buried in Columbus Green Lawn Cemetery in October 1870, following a funeral procession designed to honor one of Ohio's busiest and most persistent promoters.12 Throughout his career William Turner Coggeshall was a literary booster, devoted to the belief that authors living and working in the newly settled West deserved more attention--and more praise--than they customarily received. The sources of this attitude are not difficult to discover. He, of course, was influenced by the general boosterism of the times, but more precisely he felt a personal responsibility to defend western writers against eastern literary snobbery and to upgrade the literature,

12. Coggeshall to Friedrich Hassaurek, January 27, 1867, Box 2, Hassaurek Papers, Ohio Historical Society. A description of the funeral is in Ohio State Journal (Columbus), October 19, 1870. |

214 OHIO

HISTORY

reward pioneer writers, and

"encourage thereby strivings of Genius, which shall

accomplish what is worthy of the example

of the past, the inspiration of the present,

and the promise of the future."13

As has been mentioned, Coggeshall's

early contact with boosterism came largely

through his experience in Cincinnati

journalism, and particularly through his friend-

ship with William D. Gallagher, an

important booster himself. In fact, Gallagher's

anthology, Selections from the

Poetical Literature of the West (1841), was the first

collection of western poetry and is also

an important source for western cultural

history.14 By way of

introduction, the anthology began with self-conscious apologies

from the editor, who confessed;

Of the productions generally, which make

up the volume, this remark may be made: they

look not, for their paternity, to men of

either leisure, wealth, or devotion to letters,--but

find it, some amid the din of the

workshop, others at the handle of the plough, a third

class in the ledger-marked

counting-room, and a fourth among the John Doism and Richard

Roism of an attorney's office. For the

most part, they have been mere momentary

outgushings of irrepressible feeling,

proceeding from the hearts of those who were daily

and hourly subjected to the perplexities

and toils of business, and the cares and anxieties

inseparable from the procuring of one's

daily bread by active occupation.--As such, let

them be judged.15

This statement serves two purposes, both

consistent with the western booster spirit.

It acts as defense against possible

attacks on the quality of the verse, since the

writers are shown to be amateurs in

literature who steal time from their professional

pursuits to court the muse. It also is a

kind of a boast, picturing the westerner as

hard working and productive, both on

practical and artistic levels, unlike--the

suggestion seems to be--effete eastern

writers who do not participate in the hustle

and bustle of daily life.

The best work in the collection is

Gallagher's own rather interesting blank-verse

poem "Miami Woods." Most of

the others are occasional pieces, effusions on aspects

of nature or domestic bliss,

topographical poems on landmarks like Indian mounds,

or derivative romantic set pieces.

Thirty-eight poets are included in the anthology,

with a total of 109 poems. Aside from

Gallagher, the only poets whose names carry

literary weight in our day are Otway

Curry and Amelia Welby, who are represented

by eight and seven poems, respectively.

As the major commentator on the volume

has remarked, it is of more historical

than aesthetic interest, and the modern reader

is attracted to it mostly out of

curiosity.16 In its day, though, Gallagher's anthology

was of considerable significance. The

Duyckinck brothers, arbiters of eastern literary

taste, mentioned it with admiration.17

Certainly young poets of the West looked to

it as a standard to guide their own

work. As a literary booster, William T. Coggeshall

must also have been attracted to the

collection for its literary merits as well as for

its potential for further exploitation.

13. William T. Coggeshall, The

Protective Policy in Literature: A Discourse on the Social and

Moral Advantages of the Cultivation

of Local Literature (Columbus, 1859),

16.

14. For comments on Gallagher, see John

T. Flanagan's introduction to the facsimile edition

of Selections from the Poetical

Literature of the West (Gainesville, Fla., 1968).

15. William D. Gallagher, ed., Selections

from the Poetical Literature of the West (Cincinnati,

1841), 8.

16. Flanagan, ed., Selections, xvi.

17. See the comment in Evert A.

and George L. Duyckinck, Cyclopaedia of American Litera-

ture (New York, 1855), II, 471.

William T. Coggeshall

215

It is impossible to fix with precision

the moment of Coggeshall's decision to follow

Gallagher's lead in producing another

anthology of western poetry. We know that

at least as early as 1855, Coggeshall

was thinking about such a project. In a letter

to his friend Orville J. Victor in

October, Coggeshall wrote: "I am now hard at work

upon 'The West and its Literature.' I

shall aim to make some hits which shall seem

as rebukes to a certain class of people

whom you know."18 The last reference is

probably to the New York literary

establishment, particularly to Rufus Wilmot

Griswold and Evert and George Duyckinck,

who were to Coggeshall the arch

enemies of western literature. "The

West and Its Literature" is a major statement

of regionalism in American

literature--and is a key document in Coggeshall's

booster campaign for western writing. It

was first presented as a lecture on June 22,

1858, to the Beta Theta Pi Society of Ohio

University during the school's fifty-fourth

commencement activities, and then in

1859 it was retitled and published by Follett

and Foster of Columbus as The

Protective Policy in Literature: A Discourse on the

Social and Moral Advantages of the

Cultivation of Local Literature.

Like most boosters, Coggeshall began his

speech with the statement that the

character of westerners, formed partly

by a distinctive natural environment, is so

unlike that of easterners that only

local literature can properly express it. Since similar

arguments about regional peculiarities

were already in use in 1858 by southerners

bent on separating themselves from the

Union which Coggeshall so firmly supported,

he was forced to defend his "sectionalism."

"Literature which lives," Coggeshall

said, "represents the spirit of a

people. In that sense it must be 'sectional,' or local;

in a word, native."

But Coggeshall was aware that this

"spirit of a people" was not always evident in

the writings of westerners--and that

works which did express it were only infre-

quently monetary or critical successes.

Remembering the financial troubles with his

Genius of the West, he felt some measure of blame must be shared by

westerners

themselves. To account for early

failures of the region's literary endeavors, par-

ticularly magazines, Coggeshall pointed

to the West's "servile dependence upon the

Atlantic States, and in ungenerous

distrust of home energy, home honesty, and home

capacity." He then endeavored to

show what would happen if this spirit of indiffer-

ence were allowed to chill the

development of "an individual literature." The West

would become as barren of local talent

as the land cleared of its virgin forests by

foolish but ambitious pioneers, and

quick growing replacements (eastern literary

works) would be poor substitutes for the

native monarch oak, beech, or elm.

Even if recognized at home, Coggeshall

thought that western writers who en-

deavored to express the true character

of their region might still not fare well. The

reason, which is the main target of his

wrath in the lecture, was the deliberate

neglect of western writing by eastern

critics, particularly by Rufus Griswold and the

Duyckincks. Coggeshall complained that The

Prose Writers of America, one of

Griswold's anthologies, recognized with

biographical notices only two westerners,

Timothy Flint and James Hall; this was

serious enough, but it became even more

serious when one realized both of these

"westerners" were born in the East. "The

student of Literature," Coggeshall

declared, "could never ascertain, from 'standard

authority,' that there had been prose

writers in Ohio, or Indiana, or Kentucky, or

Illinois, or Michigan."

Although Coggeshall admitted that

Griswold's attitude toward western poets, as

18. Coggeshall to O. J. Victor, October

9, 1855, Coggeshall Papers, Box 1.

216 OHIO

HISTORY

manifested by their inclusion in The

Poets and Poetry of America, was somewhat

more liberal, he still complained that

most who appeared were eastern-born. If one

were not by birth an easterner, only one

route to inclusion in Griswold's anthology

existed: "Only those men who,

writing prose in the West, published it in the East,

have been considered by Mr. Griswold

worthy of notice; consequently, a large

number, whom the people of the West

should honor and respect, and who deserve

to be introduced to every student of

American literature, are grossly slighted."

Toward the Duyckincks Coggeshall's

attitude was equally vituperative: "[with only

a few exceptions] the world is left in

ignorance, so far as the Cyclopedia of American

Literature can leave it, of native

talent for authorship in any Western State." In

neither the Cyclopaedia nor

Griswold's anthologies did Coggeshall see much hope

for the encouragement of western literature:

Without fear of successful

contradiction, I affirm that neither Griswold's Survey of Amer-

ican Literature, in three volumes, nor

Ducykink's [sic] Cyclopedia, in two volumes, nor

both together, can be given credit for

due respect to western authorship, while they exhibit

active diligence in 'making a good show'

for all the giants and many of the dwarfs of

eastern authordom:

After this dismal review of the past

fortunes of western literature, Coggeshall con-

cluded his discourse on "The West

and its Literature" with a paean to western

character and the writing that expressed

it. The future, he prophesied, would be

much brighter.19

This optimistic prediction is in reality

an announcement--the West's answer to

Griswold's Poets and Poetry of

America. Since western writing fared so miserably

at the hands of eastern critics, the

solution to neglect was obvious: what the West

needed was its own anthology, a thorough

compendium of the accomplishments of

native writers which would prove to

easterners and westerners alike that the muses

of literature were well established in

the Ohio Valley. Advance sheets of Coggeshall's

Poets and Poetry of the West--the only one of the three intended volumes that was

published, probably because of the

intervention of the Civil War--were apparently

ready by the spring of 1860.

On May 5, 1860, in an unsigned review in

the Ohio State Journal, William Dean

Howells commented on the anthology which

was originally scheduled for publication

that June. A contributor to the volume

himself, Howells welcomed it as a much-

needed work but was hesitant in his

praise. He said that Coggeshall's editorial policy

seemed to favor quantity over quality,

"so that while every poem of positive merit

which the west has produced, will be

included in the book, the work will be made

representative of what is respectable in

our poetical literature, and no writer of

reputation will be passed over, because

his verse cannot be tried by the highest

[eastern] criticism."20 When

The Poets and Poetry of the West was finally published,

probably in the autumn of 1860, by

Follet, Foster and Company of Columbus, the

fruits of Coggeshall's labor--and the

wisdom of his policy of liberal inclusion--

19. Coggeshall, Protective Policy in

Literature, 3, 17-24.

20. Ohio State Journal (Columbus), May 5, 1860. For a fuller review of the

published

anthology, see Ohio State Journal, September

1, 1860. Also the work of Howells, this review is

somewhat hesitant but generally more

favorable than the first. Of Coggeshall himself Howells

remarks: "Few men in the country

could have brought so much patience and ardor to the work-

no other man in the West could have done

so. Eager to render justice--perhaps too eager to

encourage--yet keeping the endurance of

the reader in view, he has made a book entirely

creditable to himself. - And we think it

creditable to the West, too."

William T. Coggeshall

217

were ready to be judged by all. Sold by

subscription only, the anthology was a

handsome octavo volume of 688 pages as

well printed and bound as its publishers

had earlier advertised.21

In his brief and business-like preface,

Coggeshall echoed William D. Gallagher's

statement from the 1841 anthology to the

effect that few of the authors represented

were professional writers. Only ten

devoted themselves full time to the profession

of authorship. The rest snatched time

for art from their daily pursuits of law, medi-

cine, politics, teaching, preaching,

farming, laboring, editing, printing, and house-

keeping. To counter the eastern

influence in Griswold's anthologies, Coggeshall

took pains to point out, statistically,

the western origins of the writers he included.

By birth many of the 159 writers

(ninety-eight men and sixty-one women)22 were,

of course, easterners, fifteen from New

York, twelve from Pennsylvania, thirty-one

from New England; but seventy-five were

natives of the Ohio Valley, thirty-nine

from Ohio itself. Over a third resided

in Ohio (60 by Coggeshall's count, really 61);

the next best represented states, in

order, are Indiana (23, in fact 25); Kentucky (14,

in fact 16); Illinois (13); Michigan

(5); Wisconsin (4, in fact 5); Missouri (3, in

fact 5); Iowa (2); Minnesota (2); Kansas

(1). By the numbers alone it is clear

that the anthology is a western

product, an answer to the East, and a monument to

the literary work of native sons of the

Ohio-Mississippi Valley.

Each poet in the volume is introduced in

a biographical notice supplied by

Coggeshall or by one of his associates,

Gallagher, Coates Kinney, O. J. Victor,

Benjamin St. James Fry, and William Dean

Howells, among others. Howells wrote

four of the notices, all relatively

short and on minor Ohio poets: John H. A. Bone,

an Englishman involved in Cleveland

journalism; Gordon A. Stewart, a former

journalist and Kenton lawyer; Helen L.

Bostwick, a Ravenna poetess and writer of

children's stories; and Mary R.

Whittlesey, a Cleveland poetess. All of the notes,

although not always accurate, are a

valuable source of information about the writers

and constituted a sort of biographical

cyclopaedia along the same lines as the

Duyckincks' work.

The verse in The Poets and Poetry of

the West was as western as its contributors,

at least in the way Coggeshall

understood that adjective. Much of it had western

themes: Indians, the difficulties of

settlement, the beauty of the Ohio Valley, local

legends and myths. But a considerable

number of the poems could just as well have

been written in the East, or in any

other part of America. Many poems deal with

domesticity, love, issues of philosophy

and religion. Such were not excluded since

Coggeshall intended to produce an

anthology that would also demonstrate that the

West could write poetry quite as

copiously as did the East. Certainly the anthology

achieved this goal, since it included a

great quantity of verse. Much of it, however,

is mediocre--not really dull but not

distinguished either, and again is of more

interest to the historian than to the

connoisseur of literary art. The same can be said

for the poetry in Griswold's anthology

and for much of mid-nineteenth-century

American verse, for that matter.23

21. In a lettter to O. J. Victor, August 1, 1860, Coggeshall noted: "We are

not going to finish

the Poetry till late in the fall. The

prospect is good." Coggeshall Papers, Box 1.

22. In his preface Coggeshall says there

are 152 writers, 97 men and 55 women. This minor

error, explicable only by poor editing,

has been repeated by all commentators on the volume.

23. Poets of historical interest in the

anthology include Salmon P. Chase, Sarah T. Bolton,

Alice and Phoebe Cary, Otway Curry, Anna

P. Dinnies, Julia Dumont, William D. Gallagher,

Coates Kinney, John J. Piatt, George D.

Prentice, Sarah L. P. Smith, Laura M. Thurston,

William R. Ross, Amelia B. Welby, and

the Fuller sisters, Frances (Barritt) and Metta (Victor).

The only poet who later became famous is

William Dean Howells, an Ohioan, who is represented

by six poems from his very early

literary career.

|

218 OHIO HISTORY An example of the verse in the anthology illustrates the literary

standards of Coggeshall's time and shows the western nature of the works he

included. "To the Ohio River," a paean to the natural beauty of the West, was

written by William Dana Emerson. A native of Marietta, Ohio, Emerson practiced law in

Cincinnati and contributed to literary periodicals there in the late 1840's. The poem

was first printed in Occasional Thoughts in Verse, a collection of thirty-nine of

the lawyer's poems, printed for private circulation in Springfield, Ohio, in 1850. |

|

TO THE OHIO RIVER. |

|

Flow on, majestic River! A mightier bids thee come, And join him on his radiant way, To seek an ocean home; Flow on amid the vale and hill, And the wide West with beauty fill. I have seen thee in the sunlight, With the summer breeze at play, When a million sparkling jewels shone Upon thy rippled way; How fine a picture of the strife Between the smiles and tears of life! I have seen thee when the storm cloud Was mirrored in thy face, And the tempest started thy white waves On a merry, merry race; And I've thought how little sorrow's wind Can stir the deeply flowing mind. I have seen thee when the morning Hath tinged with lovely bloom Thy features, waking tranquilly From night's romantic gloom; If every life had such a morn, It were a blessing to be born! And when the evening heavens Were on thy canvas spread, And wrapt in golden splendor, Day Lay beautiful and dead; Thus sweet were man's expiring breath, Oh, who would fear the embrace of death! |

|

And when old Winter paves thee For the fiery foot of youth; And thy soft waters underneath Were gliding, clear as truth; So oft an honest heart we trace, Beneath a sorrow-frozen face. And when thou wert a chaos Of crystals thronging on, Till melted by the breath of Spring, Thou bidst the steamers run; Then thousands of the fair and free Were swiftly borne along on thee. But now the Sun of summer Hath left the sand-bars bright, And the steamer's thunder, and his fires No more disturb the night; Thou seemest like those fairy streams We sometimes meet with in our dreams. How Spring has decked the forest! That forest kneels to thee; And the long canoe and the croaking skiff, Are stemming thy current free; Thy placid marge is fringed with green, Save where the villas intervene. Again the rush of waters Unfurls the flag of steam, And the river palace in its pomp, Divides the trembling stream; Thy angry surges lash the shore, Then sleep as sweetly as before. |

|

William T. Coggeshall 219 |

|

Then Autumn pours her plenty, And makes thee all alive, With floating barks that show how well Thy cultured valleys thrive; The undressing fields yield up their grain, To dress in richer robes again. Too soon thy brimming channel Has widened to the hill, As if the lap of wealthy plain With deeper wealth to fill; Oh! take not more than thou dost give, But let the toil-worn cotter live. Oh! could I see thee slumber, As thou wast wont of yore, When the Indian in his birchen bark, Sped lightly from the shore; Then fiery eyes gleamed through the wood, And thou wast often tinged with blood. The tomahawk and arrow, The wigwam and the deer, Made up the red man's little world, Unknown to smile or tear; The spire, the turret and the tree, Then mingled not their shades on thee. |

|

Now an hundred youthful cities Are gladdened by thy smile, And thy breezes sweetened through the fields, The husbandman beguile; Those fields were planted by the brave,-- Oh! let not fraud come near their grave. Roll on, my own bright River, In loveliness sublime; Through every season, every age, The favorite of Time! Would that my soul could with thee roam, Through the long centuries to come! I have gazed upon thy beauty, Till my heart is wed to thee; Teach it to flow o'er life's long plain, In tranquil majesty; Its channel growing deep and wide-- May Heaven's own sea receive its tide!24 |

|

If the quality of the poetry is debatable, the achievement of William

T. Coggeshall in collecting and presenting it is not. In The Poets and Poetry of

the West Coggeshall proved the fertility of western writers; he knew their limitations,

but he knew, too, that they had been neglected. His anthology helped to redress the

grievance and to show that western literature was no longer going to be ignored.

Later critics, particularly those interested in "local color" writing,

became familiar with the accomplishments of western literature precisely because men like

Coggeshall had promoted it so vigorously. It is perhaps fitting that William Dean Howells, an associate of

Coggeshall's and contributor of four biographical sketches and six poems to the

anthology, came, in time, to replace Griswold and the Duyckincks as the chief arbiter of

eastern literary taste. As editor-in-chief from 1871-1881 of Atlantic Monthly, the

proper Boston magazine that set the tone for eastern writing, Howells helped to

educate the East to understand new writers, many of them westerners. At Atlantic

Monthly and later 24. William T. Coggeshall, ed., The Poets and Poetry of the West (Columbus,

1860), 285-286. |

220

OHIO HISTORY

when he conducted the "Easy

Chair" column of Harper's Monthly in New York, the

Ohioan promoted such western writers as

Hamlin Garland and Frank Norris. In

some respects, then, Howell's literary

career may be seen as a direct product of

western boosterism and a triumph of

Coggeshall's aspirations.25

25. Coggeshall's boosterism was

continued also by William Henry Venable (1836-1920), an

Ohioan whose energies were directed

toward promoting the work of writers of his native state.

Venable, educator, historian, poet, and

novelist, was a devoted student of the early literature of

Ohio. He contributed important notes on

Ohio authors and their work to the first volumes of

Ohio Archaeological and Historical

Quarterly: "Literary Periodicals

of the Ohio Valley," I

(1888), 201-205; "Some Early

Travelers and Annalists of the Ohio Valley," ibid., 230-242;

"William Davis Gallagher," ibid., 358-375;

and ibid., II (1889), 309-326.

Venable's most important booster project

is his Beginnings of Literary Culture in the Ohio

Valley (1891), still the standard source for much information

about the early literature of the

Ohio Valley West. In 1931 W. H.

Venable's son, Emerson, and Emerson's daughter, Mrs.

Evelyn Venable Mohr (Mrs. Hall Mohr),

presented to the Ohio Historical Society the Dolores

Cameron Venable Memorial Collection in

honor of Emerson's deceased wife (Dolores Cameron

Venable, Evelyn's mother). This

collection of books, letters, manuscripts, and photographs deal-

ing with nineteenth-century Ohio authors

(most notably W. H. Venable and Coates Kinney)

includes many important letters and

other documents assembled by William Henry Venable in

his "booster" campaign to

promote the literature of Ohio. The Venables obviously followed the

same honorable tradition as did William

T. Coggeshall.