Ohio History Journal

|

THE OHIO ROAD EXPERIMENT 1913-1916

by WAYNE E. FULLER

In December 1914, the Signal, a Zanesville, Ohio, newspaper, carried a story captioned, "Jacob Johnson of the West Pike Died Thursday." The story was interesting, not because Jacob Johnson was renowned, but be- cause he was, at the time of his death, eighty-seven years old and had lived his entire life west of Zanesville near the famous highway which the Ameri- can people knew as the old National Road, but which the people of Zanes- ville called the West Pike. Born in 1827, more than a year before Andrew Jackson became president, Johnson had lived to see the traffic along the old road west of Zanesville pass from flood stage to a trickle. More than that, his life had spanned a complete cycle in the relationship of the road to the national government.1 What the people of Zanesville called the West Pike was a fifty-two mile link in the National Road, which ran from Cumberland, Maryland, to Illi- nois. Constructed by the national government between 1829 and 1835,

NOTES ARE ON PAGES 70-71 |

14 OHIO HISTORY

the West Pike passed through Muskingum,

Licking, and Franklin counties,

and reached from Zanesville to Columbus;

and if it was not built as elab-

orately as a Roman road, still it was

like the rest of the National Road, the

best built road in the nation.

Altogether it was eighty feet wide, with a

central thirty foot macadamized section

which had been graded and filled

to a depth of almost one foot with three

strata of crushed stone, or "pre-

pared metal," as it was called.

Furthermore, the low places along the way

and the rivers and streams that crossed

the road had been either provided

with culverts or bridged with sturdy

stone bridges that were models

of masonry in their day.2

Once, in the days of Presidents Jackson

and Martin Van Buren, the

West Pike had been a part of the

nation's principal artery connecting

East and West. In those days a great

chain of humanity moved along its

graveled surface, tarried overnight at

the inns and wagon-stations along

the way, and eventually made its way

beyond Zanesville and Columbus as

it moved on to the ever-beckoning West.

Congressmen, senators, even

presidents, mingled with the westering

pioneers as they made their way

to and from the nation's capital. And

over this road, too, in overburdened

stagecoaches, passed the United States

mail, bringing the news of the day

to a great many isolated Americans for

whom it was the only means of

communication with the world east of the

Appalachian Mountains.3

The West Pike had been built by the

national government, it was true,

but the government did not long maintain

it. Indeed, as early as 1831, be-

fore the road was completely built, the

state government of Ohio agreed

to maintain the entire National Road

through Ohio and established a toll

system for that purpose. Eventually,

however, this system too broke down,

and in the years after the Civil War,

the upkeep of the road was left to

the counties, each to care for that

portion of the road within its boundaries.4

By this time, the heyday of the National

Road had passed. Better

methods of transportation west had been

found than the old road with all

its slowness and discomforts could provide.

Even before the Civil War,

men had become interested in other forms

of transportation, first in canals,

and then in railroads; and after the

Civil War, the building of railroads

throughout the Midwest so diminished the

traffic on the road that by 1900

it was scarcely more than another of the

country's poor farm-to-market

country roads.

But even then a new era was opening for

the National Road, and more

particularly for the West Pike. For a

good-roads campaign was under way

in the early 1900's, and congressmen and

their constituents had begun to

talk grandly about securing help from

the national government to build

and maintain their roads.

The idea was net new. In fact,

congressmen and presidents had dis-

cussed it thoroughly at the time the old

National Road was being built,

only to come at last to the conclusion

that for the national government to

build and maintain roads in the states

was unconstitutional. This belief had

somehow become deeply implanted in the

public mind and was not the least

|

of the reasons for the government's turning over to the states the upkeep of the one road it had built. But times had changed. With the manufacture of each new automobile and the development of rural free delivery of mail --a system which could not operate efficiently without decent country roads--good roads became an absolute necessity. Besides, the coming of rural free delivery neatly dispatched the old argument that national aid for roads was unconstitutional. For every road over which the rural mail- man carried the mail was obviously a post road, and congress, so it was argued, assuredly had the right to help in the building and maintenance of post roads.5 And so, with the constitutional argument gone and farmers and auto- mobile enthusiasts writing letters to their friends in Washington, congress- men began introducing good-roads bills in congress, and in the first decade of the new century there seemed to be almost as many road-building schemes as there were congressmen. Finally, in 1912, in order to stall for time, congress appropriated $500,000 to be used in helping states and counties build experimental roads, stipulating two conditions: first, that the national government supervise the road construction, and second, that each state or county participating in the experiment contribute two dollars for every one given by the national government. So began the novel dollar- matching scheme that has played so great a role in the nation's develop- ment in this century.6 At first, during the remainder of President Taft's administration, plans were made to distribute $10,000 of the $500,000 appropriation to each state interested in the experiment. Before this plan could materialize, however, Woodrow Wilson became president, and his administration devised a |

16 OHIO HISTORY

scheme to build a limited number of

roads located in areas of the nation

where climatic and topographic

conditions varied extensively from one

another. In this way, sums larger than

$10,000 of government money might

be spent on each experimental road and a

variety of road materials might

be tested under different kinds of

weather and soil conditions.7

Among the sites chosen for the

experiment was the West Pike. Perhaps

the old road was chosen partly for

sentimental reasons; in any case, it

seemed particularly fitting that here,

where once the government had built

a road, it should undertake to rebuild

it some eighty years later. Accord-

ingly, a contract was drawn in which it

was agreed that the national

government would contribute $120,000 to

the rebuilding of the West Pike

from Zanesville to the South Fork of the

Licking River near the town of

Hebron, a distance of almost twenty-four

miles. This sum was to be matched

by $100,000 from Muskingum County and

$140,000 from Licking County.

In addition, the state of Ohio agreed to

give $80,000 toward the work and

also to continue, at its own expense, the

building of the road through

the remaining part of Licking County to

the east line of Franklin County,

where it would connect with a portion of

the old road that had already been

rebuilt by the people of Franklin

County.8

By the spring of 1914, Muskingum and

Licking counties had bonded

themselves to raise the needed money and

were ready to sign the final con-

tract with the secretary of agriculture,

when opposition to the project

arose from the brick manufacturers in

Zanesville.9

The trouble began when it was discovered

that the national government

had specified that the West Pike was to

be rebuilt with cement instead of

brick. As it happened, over a thousand

men were employed in the Zanes-

ville brick factories, and the

revelation of the government's decision to use

cement on the road threw the Zanesville

Chamber of Commerce into a

tizzy. General R. B. Brown, secretary of

the chamber of commerce, de-

clared that "the decision was an

outrage to Zanesville and particularly

Zanesville business interests," and

urged the townspeople to fight the great

injustice. "If there is an ounce of

red blood in our bodies," said he, "we

will protest against this to the bitter

end."10

The reason for the decision to use

cement was, of course, a matter of

dollars and cents. The government was

prepared to support the rebuilding

of the West Pike at a cost up to, but

not exceeding, $16,000 per mile. Cement

could be used for that figure; brick

could not. But this explanation was not

satisfactory to the Zanesville business

interests. R. C. Burton, secretary

and treasurer of the Townshend Brick and

Contracting Company, was

certain the proposal to use cement

instead of brick was a conspiracy be-

tween the government and cement

manufacturers. Claiming that "the

specifications requiring the adoption of

concrete were prepared months

ago at the instigation of the concrete

manufacturers," and "that the brick

manufacturers 'got it in the

neck,'" he prophesied that a delegation of

brick builders from all over the country

would go to Washington to make

an investigation. Moreover, if worse

came to worst, he said, and "there is

THE OHIO ROAD EXPERIMENT 17

to be used concrete or nothing, it will

be nothing, as the brick manufac-

turers will enjoin the work if concrete

is to be used."11

For a time, it appeared the brick

builders would make good their

threat to stop the work. They filed a

strong protest with Governor James

M. Cox and State Highway Commissioner

James R. Marker, and these two

in turn, with the support of the

district's congressman, George White, tried

to get the post office department, one

of the government agencies in charge

of the experiment, to agree to the

demands for brick. But all in vain. In-

deed, it seemed for a moment that the

post office department might cancel

the project entirely and move the Ohio

appropriation elsewhere. Rumors

of this helped induce those who most

wanted the road to raise some nine

petitions urging that the road be build

with concrete if it could not be

built with brick. After this the

opposition to the building of the new road

began to melt, although as late as April

a delegation from the Zanesville

Chamber of Commerce was in Washington

protesting against the use of

cement on the road.12

In the meantime, on March 23, 1914,

while the controversy was still

raging, the final agreement between the

national government, the state of

Ohio, and Muskingum and Licking counties

was reached regarding the im-

provement of the West Pike. The next

month the contract for building the

road was let to the H. E. Culbertson

Company of Cleveland for $436,017.00,

and finally, on May 11, the Signal noted

that the headquarters of the Cul-

bertson Company were being established

near the Talley icehouse and that

some fifty road workers had been brought

to the city and moved to a camp

on the West Pike. Work on the road was

expected to begin within the

week.13

The government's road engineers,

surveyors, and economic statisticians

who swept into Zanesville to plan the

rebuilding of the road and collect

statistical data on the area, found the

West Pike considerably changed from

the way it was in the pre-Civil War days

when the great wagon trains and

stagecoaches had rolled across its macadam

back. The countryside along

the way, with its fields of corn and

wheat and pastures dotted with grazing

sheep and cattle were much the same as

they had been, of course, as were

the rolling hills that ranged from an

elevation of 725 to 1125 feet. Even the

little villages through which the road

passed were not much different in

point of population from what they had

been in the earlier days. Mt.

Sterling, Gratiot, Brownsville, and

Jacksontown each had something more

than two hundred inhabitants in 1913,

while Linnville and Coaltown

claimed seventy-five apiece and

Amsterdam one hundred.14

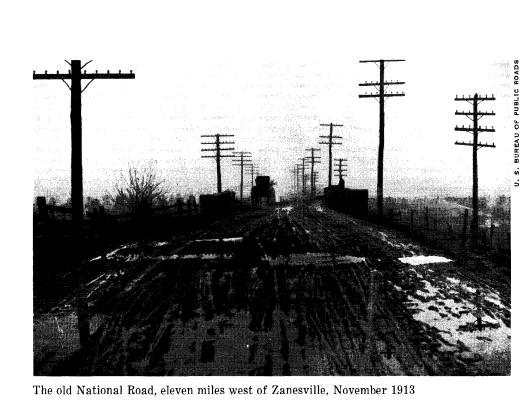

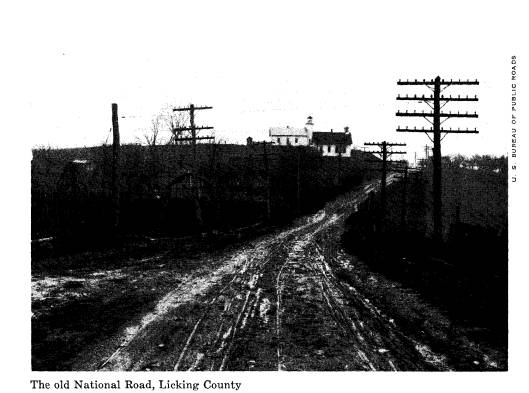

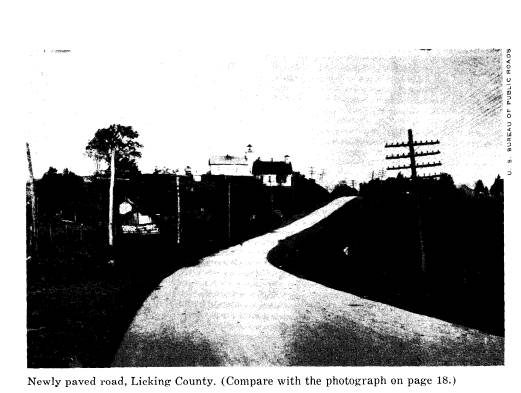

It was in the road itself, showing all

the ravages of time and neglect,

that the changes were most marked. Here

and there the original surfacing

on the West Pike had virtually

disappeared. Chuck-holes and ruts marred

its appearance, water stood in puddles

in its low places, and in one spot

at least, a small stream had washed away

a part of the road. Indicative

of the general status of road maintenance

of the period was a sign

marking the place where a neglected

county road joined the West Pike.

|

ANY PERSONS TRAVELING 'THIS ROAD, it read, DO SO AT THEIR OWN RISK.15 Nor was the old road eighty feet wide as it once had been. In the course of years, farmers along the way had moved their fences and even their barns onto the right-of-way, narrowing the road in some cases to the very edge of the macadam. Moreover, the marks of the twentieth century were all about. Segments of six different rural mail routes, over which the mail was carried every day except Sunday directly to the farmers, covered all of the twenty-four mile strip to be rebuilt, and some 160 rural mailboxes, unheard of in the old days, stood at farm gates along the road. Remarkable, too, was the fact that when the West Pike had been built, Alexander Gra- ham Bell's famous invention was still more than forty years in the future. Now telephone poles and wires lined both sides of the road.16 Changed as the West Pike was in 1914, the old stage-driver of the 1840's, revisiting the scenes of his triumphs in that year, could still have seen many of the old landmarks. Stone bridges, like the one just outside the Zanesville city limits, over which his stagecoach would have passed many a time, were still standing firm as the day they were built. Familiar too would have been the limestone milestones at the edge of the road. In front of the Townshend school, for example, was one such stone, somewhat askew, to be sure, but still legible, which read: ZANESVILLE 3 MILES, COLUMBUS 50 1/2 MILES, WHEELING 77 MILES, CUMBERLAND 207 MILES. True, the old stage-driver would have had to go to the old records to discover that C. Niswanger, James Hampson, and D. Scott, were the names written on the north wall of the old bridge located nearly six miles west of Zanesville. But the date of the marker, 1830, and the inscription, THE POLICY OF THE NATION, RECIPROCITY AT HOME AND ABROAD, were still plain enough for him to have made out without his glasses.l7 |

THE OHIO ROAD EXPERIMENT 19

And surely most familiar of all to the

old stage-driver had he visited the

West Pike in 1914, would have been the

five-mile tavern some three miles

west of Zanesville. Here was one of the

finest taverns to be found along

the entire length of the National Road.

Made for the most part of dressed

limestone, the larger portion of it had

been built in 1832 and the smaller

in 1860, on the eve of the Civil War.

The accumulation of years, a small

picket fence, the telephone lines

running past the door, and the growth of

trees around it, had somewhat changed

its outward appearance, but any

stagecoach driver who had stayed there

over night would have been un-

likely to mistake this old tavern for

another. Its huge chimneys and mas-

sive, rugged appearance were features

not easily forgotten.18

Neither the government's engineers nor

those of the Culbertson Com-

pany, however, had much time to

contemplate the old landmarks along the

road. Unlike the contract "for

clearing and grubbing" given the contractors

who built the road in the 1830's, the

Culbertson contract called for grading,

paving, and building drainage structures,

and this was a gigantic under-

taking, especially since the making of

cement roads was still in the experi-

mental stage. Indeed, until the work

began on the West Pike, there was only

a handful of cement roads in the nation.

In 1912, a demonstration on the

building of cement roads, which the

Culbertson engineers may have ob-

served, was given in Wayne County,

Michigan, but even here paving had

apparently not reached the proportions

contemplated on the West Pike.19

The first thing that had to be done on

the West Pike was to order the

farmers and telephone companies who had

encroached on the road's right-

of-way, to move their telephone lines,

fences, and even barns back from the

road to give the contractor the needed

clearance. The second problem was

to find some way to move sand and cement

and other materials to places

along the road where they were needed.

The Culbertson Company solved

this by building a narrow-gauge railroad

along the road's right-of-way to

haul the needed materials. The railroad

would have been expensive under

any circumstances, but it was the more

so in this case because the steep

grade between Linnville and Gratiot

necessitated the use of special steam

engines.20

In spite of these difficulties, grading

from both the Hebron and Zanes-

ville ends of the road and construction

of the Culbertson narrow-gauge rail-

road began on May 14, 1914. On June 9,

the building and repair of bridges

and culverts, many of them still in

wonderful condition after eighty some

years, was started. Finally, on June 17,

concreting began with mixer one

at the Zanesville station. One week

later, mixer two at the National Road

station near Hebron went into operation,

and on July 22, mixer three, sta-

tioned some distance east of mixer two,

was set to move west with the ex-

pectation of meeting mixer two in

time.21

Of all the work done on the West Pike,

the most experimental, important,

and demanding was the concreting. The

huge Austin mixers that could lay

down two miles of concrete in a month,

ate up a gargantuan amount of sand

and Portland cement, all of which, of

course, had to be hauled to the paving

20 OHIO HISTORY

site over the Culbertson railroad.

Moreover, great care had to be taken

not only to screen the gravel carefully

but also to get the correct mixture

of sand and cement, and at least once

during the project the bureau of

public roads had to warn the government

people on the job that the cement

samples sent from the Ohio road did not

measure up to the bureau's stand-

ards. Water, too, was a problem and at

one point had to be pumped from

Timber Run near the Talley ice plant to

the job five miles away. But this

was not entirely satisfactory. Because

of a dry summer, Timber Run began

to go dry in August, and new sources of

water had to be found farther out

on the road.22

Nevertheless, once the paving began it

proceeded smoothly and efficiently.

Work was conducted from numbered

stations, beginning at station 0-00 at

Zanesville and station 683-70 near the

National Road station, and the ce-

ment was laid in sections sixteen feet

wide and varying in some instances

as much as thirty to ninety feet in

length. After the cement was poured and

smoothed, it was covered with a canvas,

which was kept wet for about four

days. Then the canvas was removed and

loose dirt thrown over the cement.

Like the canvas, the dirt was kept wet

for as long as two weeks; finally, it

too was removed, to leave, as a reporter

from the Signal wrote, "one of the

smoothest pieces of roadway in

Ohio."23

So well was the work progressing, in

spite of shortages and dry weather,

that on Wednesday, August 26, 1914, some

640 feet of concrete were laid,

and predictions were made that the

entire road of nearly twenty-four miles

would be paved by the middle of November.

As it turned out, this prediction

was overly optimistic. The work had been

somewhat slowed by the dry

weather, it was true, but the scarcity

of gravel proved to be the principal

problem. Partly for experimental

purposes the Culbertson Company was

using ordinary gravel and crushed stone

on the project. Both of these were

apparently somewhat costly to obtain in

the immediate vicinity, and in

August, Culbertson Company officials

began to suggest the impossibility of

securing enough gravel and crushed stone

to complete the job in November.

There was some indication that the

company had not really tried very hard

to obtain the necessary materials in the

nearby area, and intended to delay

the project until the next year in order

to use the winter months to bring

cheaper gravel in from Dresden, some

twenty miles away.24

Whatever the reason, the Culbertson

Company did stop construction in

November 1914. Mixer three had completed

its assignment by October 27,

but mixers one and two shut down

November 14, still far short of their

goals. The work on the drainage

structures, also uncompleted, came to a

halt in Licking County November 13, and

in Muskingum County Novem-

ber 16. Only the grading in Licking

County continued until January 28,

1915.25

Although the concreting had been rigidly

inspected by government in-

spectors, a fact which had caused the

Culbertson Company much concern,

certain flaws which were to appear in

all cement roads began to show up in

the West Pike in the fall and winter of

1914-15. About a month after the

THE OHIO ROAD EXPERIMENT 21

first sections had been scraped free of

dirt, Charles H. Moorefield, the gov-

ernment's engineer in charge of the

work, noticed that the pavement had

begun to spall, or flake off, at the

joints between the sections. Then during

the winter months, probably because of

the contraction of the cement, long-

itudinal cracks appeared.26

It was then generally believed that some

bituminous product could be

used to prevent spalling and to fill in

the cracks, but the building of cement

roads was so new, no one preparation to

correct these problems had been

decided upon. Upon Moorefield's request

for a recommendation, the bureau

of public roads replied that he might

use a light mixture of water, gasoline,

and tar, which had been used on the

government's road experiment at

Chevy Chase, Maryland; or he might

experiment with other preparations,

Tarvia A, Standard Macadam Binder A, or

Trinidad Liquid Asphalt, all of

which, the bureau reminded him, would

have to be heated before using.

Apparently, however, Moorefield came to

the conclusion that no such exotic

preparations were needed, for in the

spring of the year, upon discovering

the longitudinal cracks, he wrote the

bureau recommending that plain tar

be used to correct the damage.27

In spite of the cracks, however, and

overlooking the dismay of the

engineer from the Ohio State Highway

Commission concerning them, the

government inspectors believed that, in

general, the road had weathered

well, and as spring returned, they and

the Culbertson Company prepared

to recommence construction on the West

Pike. Work was delayed in Mus-

kingum County, but grading began in

Licking County on March 15, 1915,

and by the middle of April the company's

stone crushing apparatus there

was turning out eighty yards of crushed

stone a day. On May 5, concreting

began with mixer two, and on May 17,

work began again on the drainage

structures in the county.28

Just as the work on the road was being

renewed, however, a new crisis

threatened to disrupt the project once

more. In November 1914 state elec-

tions had been held, and Governor James

M. Cox had been defeated by Re-

publican Frank B. Willis. Soon after entering

office, the Republican at-

torney general had made a ruling that

the state government could pursue

no road project for which it did not

have the funds in hand, and word leaked

out that because there was no money left

in the treasury for the purpose,

the state government was not going to

complete the West Pike construction

from the South Fork of the Licking River

to the east line of Franklin

County as it had promised to do in the

contract made with the postmaster

general and the secretary of agriculture.29

The prospect of such a possibility

greatly excited and angered the board

of commissioners of Licking County. The

county had, the commissioners

said, incurred an indebtedness of

$140,000 on the assumption that the state

government would complete the road

through the county, and they threat-

ened to withhold the rest of the money

owing the national government

project unless the state government

agreed to fulfill its obligations. More-

over, they wrote Congressman William A.

Ashbrook, a native of Licking

|

County, asking him to do what he could to force the state government to complete the road, and Ashbrook in turn took the matter up with David F. Houston, the secretary of agriculture. "I wish you would wire the State Highway Department," he wrote, "that it must comply with this agree- ment with the Government and with the Commissioners of Licking County as well. I also urge you under no conditions to enter into any agreement changing the terms and stipulations of the contract which you entered into in this matter."30 Houston turned the matter over to L. W. Page, director of the bureau of public roads, and with the whole project in jeopardy because of Licking County's threat to withhold its funds, Page wrote Clinton Cowen, the new Ohio State Highway Commissioner, demanding to know the situation. In a series of letters, Cowen eventually made the state government's posi- tion clear. First, he admitted that the state was having trouble finding money for finishing the road, but it did intend to stand by its agreement. Would the government, he wondered, be willing to accept the completion of the road to the Franklin County border with some material cheaper than cement--asphalt macadam, perhaps, or tar-bound macadam?31 Upon Page's assurances that the government would accept the state's offer to complete the road with some other material of a bituminous type, one more crisis in the construction of the West Pike passed.32 In the meantime, work on the road in Muskingum County was still being delayed, perhaps because construction was farther advanced in this county than it was in Licking County. The grading in Muskingum County had been completed to the county line the previous year, and the pave- ment had been laid from Zanesville through Mt. Sterling, almost seven |

THE OHIO ROAD EXPERIMENT 23

miles away. Even the Mt. Sterling hill

with its famous S curve, often

thought of as the most dangerous place

in the entire road, had been paved.33

In the spring of 1915, this strip of

smooth pavement from Zanesville

to Mt. Sterling was simply irresistible

to the autoists, as they were called,

and as the weather grew warmer, more and

more people had apparently

taken to joy-riding along the West Pike,

particularly at night. On June

14, in the middle of the night, the L.

L. Hazlitt family, living just west of

Mt. Sterling and about three hundred

yards beyond the end of the paving,

was awakened by the sound of an

automobile turning around in front of

their home. The car pulled away and

headed for the village, where it

aroused Emery Pange, who rushed from his

bed to the window just in

time to see a large touring car roaring

through the town, headed for

Zanesville. "The cut-out was

'wide-open,'" he told a reporter next day,

"and the machine was going about as

fast as I ever saw one go."34

How fast the car was going when it began

the steep descent of the Mt.

Sterling hill was uncertain, but

probably too fast. It was raining and the

road was slippery, and at the S turn,

Henry A. Buerhaus, the driver of

the car and a former county auditor, who

had been involved in the first

negotiations with the government concerning

the rebuilding of the road,

lost control of his machine. The

automobile left the road, rolled over a steep

embankment, and was prevented from

falling fifty feet to the stone bridge

at the floor of the valley only by the

timely intervention of a telephone pole.

Buerhaus, and his companion on the trip,

Guy Longley, a former hackdriver

and active Republican in Zanesville,

were pinned beneath the car, and it

was not until about 4:30 in the morning

that the overturned automobile was

discovered. By that time, Buerhaus had

managed to crawl from under it

and was stretched out along the

Culbertson Company's railroad, while Guy

Longley lay dead underneath the wreck.35

Zanesville was startled by the accident.

In a land just emerging from the

horse and buggy era, before slaughter on

the highways had been accepted

as the normal course of events, an

automobile accident of such proportions

was a major catastrophe. With the

exception of some boys who had gone

off the road on a bobsled near the same

place during the winter, this was

the first major accident to occur along

the new West Pike, and, according

to the Signal, "hundreds of

automobiles containing sightseers made the trip

out the pike to the scene of the

accident," in spite of the rain and the slip-

pery road.36

All that day and the next and for a week

or more, people talked about the

tragedy and the terrible S curve and

wondered what to do about it. "The

Mt. Sterling hill, where the tragedy

occurred," ran an editorial in the

Signal, "is a treacherous descent under normal conditions and

normal speed

and all drivers should not attempt the

descent unless sure that their ma-

chine is under full control." But

for many in the town, the Signal's advice

was insufficient. They demanded that

something be done to prevent cars

from slipping off the road at that

point. A cement wall, three feet high, or

a fence painted white, they said, should

be erected around the curve in the

road where the Buerhaus car

overturned.37

24 OHIO HISTORY

But it would take time and money to

build a fence, and a number of

prominent Zanesville citizens did not

want to wait. The result was that

a group of autoists, apparently led by

Chester A. Baird, a local druggist,

got permission from the county

commissioners to erect a large sign at the

top of the hill warning drivers of the

curve ahead. And in a short time

a sign that could be seen for a half

mile was built and erected some three

hundred feet from the place where the

tragic accident had occurred. It

was six feet high and five feet wide,

with huge letters spelling out the

words DANCER, DOUBLE CURVE--DRIVE SLOW, SOUND

KLAXON.38

The accident, however, apparently never

diminished the appeal the

smooth, new pavement had for the

autoists of Zanesville. Scarcely a month

following the Buerhaus accident, two

young men from the city borrowed,

without permission, a Ford touring car

from the H. J. Baker grocery com-

pany, and accompanied by two of the

town's young women, went for a ride

on the pike. Leaving Zanesville about

eleven at night they had apparently

driven until about midnight, when for an

unexplained reason, their car

struck the ties of the Culbertson

Company's railroad and upset. Strangely,

the two men were found lying near the

car unconscious, according to the

Signal's account, but their women companions had disappeared.

The men

were not seriously injured, but they

were brought to the city and placed

in the Good Samaritan Hospital for

treatment.39

This second automobile accident on the

West Pike occurred July 13, just

one day after the Culbertson Company had

resumed concreting in Mus-

kingum County and one day before work on

the drainage structures there

had begun, and with the resumption of

construction it was predicted that

the concreting of the National Road

would be completed in two months.

Yet hardly had construction started and

the prediction been made, than

trouble once more struck the project

causing more delays and threatening

to upset time schedules.40

In the 1830's it had been the wet

weather and the cholera that had de-

layed construction on the West Pike, and

an exasperated superintendent of

construction had had to write back to

his superior in Washington that

"cholera made its appearance on a

portion of this district of the road, which

rendered it necessary to suspend

operations for about two weeks, at a time

most favorable for the advancement of

the work." But in the summer of

1915 it was weather and accidents that

upset time tables. Only the day

after work had recommenced on the

drainage structures in Muskingum

County, five supply cars were being

towed up the Mt. Sterling hill on the

Culbertson railroad when the coupling

between the engine and the first

car broke, releasing all five. The

unleashed cars sped down the hill and

over the embankment at the S curve, and

came to rest beside the remains

of the Buerhaus automobile, which had

crashed at that very spot.41

The supply cars were demolished, and so,

too, was the big danger sign

so recently placed there. Smashed by the

runaway cars, it was so utterly

destroyed that no piece of it larger

than eighteen inches square could be

THE OHIO ROAD EXPERIMENT 25

found. "A sight which would make

the strongest hearted shudder met the

gaze of those going to the scene Friday

morning," wrote the Signal reporter

of the accident. "Side by side lay

the five wrecked cars of the Culbertson

company and the body of the Buerhaus

machine which went over at this

danger point. Both are monuments to the

most dangerous curve on the

pike and one which should undoubtedly be

safeguarded and will some day

unquestionably." Fortunately, no

one was on the road at the time of the

accident; however, only a few minutes

before the cars broke loose, an auto-

mobile and a farmer with a wagon load of

hay had both passed by.42

As if this were not enough trouble, that

evening, July 15, Zanesville

was deluged with a one-inch rain. The

Muskingum and Licking rivers were

booming the next morning, and out at the

Culbertson Company's gravel

plant just west of Gant Park, the rain

had fallen on a filled gravel bin,

making it so heavy it collapsed and fell

upon a nearby crane. Damage to

bin and crane was estimated at $300, in

addition to the time taken to

build a new gravel bin.43

In spite of breakdowns and poor weather

that continued to hamper

progress, work on the road continued. By

August, the cement mixers in

both counties were going full blast, and

on September 1, mixer one crossed

the line from Muskingum into Licking

County. Two months later the

paving was all but completed. "With

good weather Saturday," the Signal

announced on November 12, "150 feet

of concrete which remains to be

poured to complete the paving of the

West Pike from Zanesville to Hebron,

Licking county, will be poured and the

longest stretch of road work and

the biggest road contract ever completed

in Ohio will be practically ready

to turn over to the state highway

department." And at last one of the

Signal's prophecies did come true. The next day, mixers one and

two met

at station 152-40, and the pavement was

completed.44

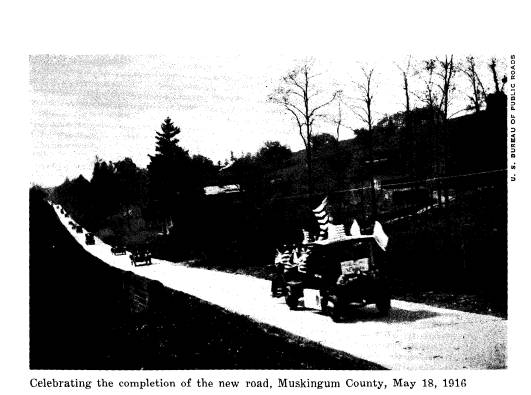

To celebrate the completion of the road

construction, the Zanesville

Chamber of Commerce announced on

November 22 that a trade excursion

would be made over the West Pike to

Jacksontown and then north to the

city of Newark thirty-five miles away.

All autoists were asked to make

the trip and form their own parties. The

cars, it was said, would leave

the courthouse at 1 P.M., November 26.45

At 12:30 on the appointed day, a fleet

of machines, gaily decorated

with bunting and streamers flying

expressions of friendship for Newark,

had assembled on Fourth, Fifth, Sixth,

and Seventh streets, and, though

somewhat late in starting, the

procession was soon under way with

Charles Baird, enthusiastic autoist, in

the pathfinder car. Following

closely behind the pathfinder car was a

truck, borrowed from the Wedge

garage, to which a trailer carrying the

United Commercial Travelers'

Boosters Band was attached.46

The trip was made almost without

incident. The pike was wonderfully

smooth, and to avoid trouble no one was

allowed to pass Baird's pathfinder

car, which maintained a steady speed of

fifteen to twenty miles per hour

throughout the trip. And because there

was always some uncertainty about

|

the performance of a machine, an auxiliary car containing "repair men," as the newspaper called them, was put in line, and all those who experi- enced mechanical troubles simply pulled to the side of the road and had their car repaired.47 At Newark, Zanesville's eleven hundred enthusiasts were welcomed effusively, and the Newark Advocate was loud in its praise of the expedi- tion. "The trip by automobile over the old National Road," ran the paper's editorial, "is indeed delightful and will be enjoyed by residents of both Muskingum and Licking counties to the fullest extent. One may now jump into a machine and drive to Zanesville as quickly as he could go from Newark to Granville [about seven miles] with a horse and buggy."48 Indeed, so enthusiastic were the citizens of Newark about the linking of the two cities and the motorcar expedition from Zanesville that the following spring they organized their own excursion of some fifteen hun- dred people and five hundred autos and motored to Zanesville. Wearing badges made of white paper showing clasped hands and in blue lettering the words "Zanesville and Newark," the Newark autoists arrived in Zanesville promptly on schedule, to the delight and awe of the Signal. From the city limits a Zanesville delegation escorted them into town, and here they were entertained with sight-seeing tours, dancing, refreshments, vocal music at Gold Hall, and with visits to open houses held by many of the clubs throughout the city.49 Years before, when Newark lay on the old route between Zanesville and Columbus, it had attempted to have the National Road built through its boundaries; but because it was too far north for the straight line the government surveyors wanted to follow, the road had gone over the route they laid out, and since that time, the two cities had been rivals. |

THE OHIO ROAD EXPERIMENT 27

But the improvement of the West Pike had

helped wipe out the old dif-

ferences. "There was a time,"

editorialized the Signal, "happily buried in

the distant past, when Zanesville and

Newark were 'hated rivals.' . . .

However, the rivalry of today is a

friendly one and ties of an enduring

friendship have been cemented. Within

the past year the two cities have

been linked together by an improved highway

and the occasion of Zanes-

ville's first visit to Newark was in

celebration of the opening of the new

road. That visit was returned by Newark

Thursday, and now that 'the ice

has been broken' it is sincerely hoped

that there will be many other inter-

city celebrations of a similar

nature."50

But what did the road experiment prove

beyond the bettering of

relations between two old enemies? And

what did the government have

to show to congress for all the money

expended and time spent?

Government experts made two studies of

the economic life along the

West Pike, one before the road was paved

and one afterwards, and the

differences the new road made were

impressive even when allowance is

made for the desire of the statisticians

to cast the experiment in as favor-

able a light as possible. Because of the

easier pull along the paved road,

for example, the average horse-drawn

load increased from 2,324 to 3,290

pounds, and the annual traffic volume

from 21,347 tons to 24,245. The

speed of travel also increased some 25

percent, and most significantly, the

cost of hauling was reduced from 28 to

19 cents per ton mile. Moreover,

it was estimated, possibly with some

exaggeration, that the value of the

land along the road had increased as

much as $7.50 an acre because of the

new road.51

Even more dramatic than these

statistics, however, were those col-

lected on the use of motorcars on the

new road. In 1915, there were 1,557

automobiles in Muskingum County, 900 of

them in Zanesville, and on

almost any Sunday afternoon after the

pavement was finished, nearly all

of them seemed to be on the pike.

Recording the Sunday drive, a phenom-

enon no longer of special importance in

America, the second economic

study revealed that "Sunday traffic

on a clear summer day is a steady run

of automobiles in each direction."

On one Sunday afternoon, for example,

May 21, 1916, eighty-eight machines

passed the village of Amsterdam in

one hour, and this was considered one of

the most lightly traveled sections

of the entire road! On such days

"old Dobbin," averaging less than five

percent of the traffic, was virtually

driven off the road.52

The full meaning of this report,

however, can be but dimly appreci-

ated by generations of Americans to whom

the automobile has become the

second self. The sheer joy of speeding

along a smooth highway at twenty-

five, or possibly thirty, miles an hour,

the feel of the wind rushing by and

through the open car, the swift passing

of a horse and buggy, and the

trip of perhaps as much as thirty or

forty miles from home in one after-

noon can be fully understood only by

those Americans who can remember

their first automobile ride and the time

when they had never been more

than ten miles away from home before.

28 OHIO HISTORY

But the motor-powered vehicles were

being put to important economic

as well as aesthetic uses. Before the

West Pike was paved, the villages of

Gratiot and Brownsville were virtually

isolated. Gratiot was ten and

Brownsville twelve miles from the

Zanesville trade center, a six to

seven hour round trip for the two-horse

hack that had been making the

trip three times a week for thirteen

years. This was more time than many

farmers could spend away from home and

still get back in time to milk

the cows; besides it cost fifty cents

each way.53

With the paving of the West Pike,

however, an auto truck replaced

the hack. It made two round trips every

day, required only one hour each

way, and reduced the price of the trip

to forty cents one way and sixty-

five cents round trip. Moreover, a large

motor bus was put on the road to

run from Hebron to Zanesville, 26.1

miles, and one could go the entire

distance for seventy-five cents; it made

one round a day between Hebron

and Brownsville, and two a day between

Zanesville and Brownsville. So

instead of three hack trips a week,

Brownsville was connected with Zanes-

ville by four motor trips a day, besides

being connected by bus with

Newark.54

The experiment proved one thing more.

From it the postmaster gen-

eral and the secretary of agriculture

learned that if the federal govern-

ment was to make large contributions for

road building within the states,

it must deal only with some state

agency, such as a state highway com-

mission. The conflict between Licking

County and the state government,

and similar more difficult problems

experienced by the government on

other projects, had convinced them that

local governments were uncertain

agencies to do business with. "From

correspondence and from the atti-

tude of local officials in many

places," read a joint report of the post-

master general and the secretary of

agriculture, "it appears that there

is a disposition frequently to avoid the

obvious requirement of the present

act . . . . The allotments have been

looked upon . . . in the light of a

gratuity, and the question has been

frequently raised . . . as to why the

government would not give the money to

the counties and let them spend

it."55

And so, when the famous federal highway

act of 1916 was enacted,

providing money for road building within

the states on a dollar matching

basis, it specified that the secretary of

agriculture was authorized "to

cooperate with the States, through their

respective State highway depart-

ments, in the construction of rural post

roads."56

THE AUTHOR: Wayne E. Fuller is a

professor of history at Texas Western

College of the University of Texas, and

the author of the recently published

book

RFD: The Changing Face of Rural

America.

70 OHIO

HISTORY

Canal, and one of the alleged

participants in the syndicate was Charles P. Taft, the

brother of William Howard Taft. These allegations were

never satisfactorily proven

and they were regarded by some as a

maneuver to embarrass Taft's candidacy for

president. Concerning Bunau-Varilla's

activities in Cincinnati, the author has not found

any mention of a member of the Taft

family.

39. Wulsin to Bunau-Varilla, February 3,

1902.

40. Taylor to Bunau-Varilla, January 28,

1901.

41. Bunau-Varilla to Mrs. Myron T.

Herrick, June 14, 1902.

42. Philippe Bunau-Varilla to Maurice

Bunau-Varilla, March 15, 1901.

43. Deering to Bunau-Varilla, March 30,

1901.

44. Bunau-Varilla to Deering, March 30,

1901.

45. Deering to Bunau-Varilla, April 1,

1901.

46. Wulsin to Bunau-Varilla, February

25, 1902.

47. Jacob H. Bromwell to Wulsin,

February 26, 1902.

48. Bunau-Varilla to Myron T. Herrick,

June 2, 1902.

49. Liberty E. Holden to Bunau-Varilla,

June 6, 1902.

50. Bunau-Varilla to Herrick, June 14,

1902.

51. Bunau-Varilla to Wulsin and Taylor,

June 21, 1902.

52. Miles P. DuVal, Cadiz to Cathay (Stanford,

Calif., 1940), 303.

53. Bunau-Varilla, Panama, 318-319.

54. Ibid., 329-336.

55. DuVal, Cadiz to Cathay, 327.

56. Ibid., 310, 332.

57. Bunau-Varilla to Loomis, December

31, 1903. Loomis was particularly helpful

in Bunau-Varilla's efforts to secure the

recognition of Panama by the nations of the

world.

58. Bunau-Varilla to Taylor and Edward

Goepper, November 9, 1903.

59. Bunau-Varilla to Wulsin and Taylor,

January 1, 1904.

60. Bunau-Varilla to Taylor, June 11,

1901.

THE OHIO ROAD

EXPERIMENT

1. The Signal, December 17, 1914. The bulk of the material for this

article was taken

from the National Archives, Washington,

D. C. I should like to thank the College Research

Institute of Texas Western College for

making my research in Washington, D. C., pos-

sible. Microfilm of the Signal, one

of Zanesville's daily newspapers, was made available

to me by the Ohio Historical Society,

for which I wish to express my appreciation.

2. Work on the "West Pike" was

begun in August 1829. The first section of twenty-one

miles west of Zanesville was

substantially finished and opened to regular travel in 1831.

By 1833 work on the remainder was

sufficiently advanced to permit mail service over the

whole length of the road, though it was

not fully completed until late in 1835. Reports of

the Secretary of War, Senate

Executive Documents, 21 cong., 2 sess., No. 17, p. 16; 22

cong., 1 sess., No. 58, p. 2; 23 cong.,

1 sess., No. 1, p. 81; 24 cong., 1 sess., No. 1, p. 194.

For vivid descriptions of the old

National Road, see the following: Thomas B. Searight,

The Old Pike: A History of the

National Road, with Incidents, Accidents, and Anecdotes

Thereon (Uniontown, Pa., 1894); Archer Butler Hulbert, The

Cumberland Road (Historic

Highways of America, X, Cleveland, 1904); R. Carlyle Buley, The Old

Northwest: Pio-

neer Period, 1815-1840 (Indianapolis, 1950); Philip D. Jordan, The National

Road (In-

dianapolis, 1948).

3. Hulbert, The Cumberland Road, 123,

174-187.

4. Jordan, The National Road, 169,

175; see also Senate Executive Documents, 23

cong., 1 sess., No. 1, p. 170.

5. Wayne E. Fuller, "Good Roads and

Rural Free Delivery of Mail," Mississippi

Valley Historical Review, XLII (1955), 67-83.

6. Ibid., 81-82; United States Statutes at Large, XXXVII,

551-552.

7. Joint Report of the Progress of Post

Road Improvement, no date, Records Relating

to Federal Aid Road Acts, Records of the

Post Office Department, Record Group 28,

National Archives (hereafter referred to

as Postal Records).

8. State of Ohio certification of money

available for post-road improvement, March

20, 1914; Muskingum County certification

of money available for post-road improvement,

March 13, 1914; Licking County

certification of money available for post-road improve-

ment, March 13, 1914; Second Economic

Study, Ohio Post Road, 2 (the date this report

was written is unknown, but the study

was made May 11-22, 1916); Clinton Cowen to

L. W. Page, June 5, 1915, all in

Correspondence, Reports, and Studies Relating to Post

Roads, Records of the Bureau of Public

Roads, Record Group 30, National Archives (all

NOTES

71

correspondence, reports, and studies

referred to hereafter are in these records unless

otherwise noted); see also The

Signal, March 18, 1916.

9. The Signal, March 24, 1914.

10. Ibid., March 18, 1914.

11. Ibid., March 20, 1914.

12. Ibid., March 23, 26, April 1,

1914.

13. Cowen to Page, June 5, 1915;

Memorandum on the H. E. Culbertson bid; The

Signal, May 11, 1914.

14. Warren Jenkins, The Ohio

Gazetteer (Columbus, 1841); First Economic Investiga-

tion, Ohio Post Road, 1-2 (the date this

report was written is unknown, but the study was

made November 22-December 4, 1913).

15. From a series of photographs taken

of the road in 1913 located in Audio-Visual

Branch, National Achives.

16. Ibid.; First Economic Investigation, Ohio Post Road, 4-5.

17. From photographs in Audio-Visual

Branch, National Archives. Christopher Nis-

wanger, whose name appeared on the north

wall of the bridge, was the contractor who

built the bridge; James Hampson and

David Scott were the road superintendents. See

Senate Executive Documents, 21 cong., 2 sess., No. 17, p. 14, and House Reports,

23 cong.,

1 sess., No. 455, p. 17.

18. From photographs in Audio-Visual

Branch, National Archives; see also Jordan,

The National Road, 123, and Hulbert, The Cumberland Road, 162.

19. Senate Executive Documents, 21

cong., 2 sess., No. 17, p. 7; Hulbert, The Cumber-

land Road, 81-82; Charles E. Foote, "The Use of Concrete in

the Construction of Roads,"

Scientific American Supplement, No.

1995, LXXVII (1914), 200-201.

20. The Signal, June 1, July 1,

1914.

21. Order and Progress of the Work, no

date, 1-3. The date of the beginning of grad-

ing at the Hebron end in this report is May 14, 1915,

obviously an error.

22. The Signal, August 4, 27,

1914; Vernon M. Pierce to W. E. Rosengarten, Novem-

ber 19, 1914.

23. Order and Progress of the Work, 1-3;

The Signal, August 27, 1914.

24. The Signal, August 27, 1914;

Charles C. Moorefield to Pierce, September 5, 1914;

Moorefield to Pierce, August 24, 1914.

25. Order and Progress of the Work.

26. Moorefield to Pierce, October 2,

1914; J. T. Pauls to Moorefield, April 20, 1915.

27. P. J. Wilson to Moorefield, October

10, 1914; Moorefield to Pierce, May 11, 1915.

28. Pauls to Moorefield, April 20, 1915;

Robert M. Waid to Moorefield, April 6, 1915;

Order and Progress of the Work.

29. The Signal, April 30, 1915,

March 18, 1916; Moorefield to Pierce, no date.

30. William A. Ashbrook to David F.

Houston, April 15, 1915.

31. Page to Cowen, May 10, 1915; Cowen

to Page, May 12, 1915; Cowen to Page, June

5, 1915.

32. Page to Cowen, June 9, 1915.

33. The Signal, June 15, 1915.

34. Ibid.

35. Ibid.

36. Ibid.

37. Ibid., and June 16, 1915.

38. Ibid., June 17, 18, 19, 1915.

39. Ibid., July 14, 1915.

40. Order and Progress of the Work.

41. Senate Executive Documents, 23

cong., 2 sess., No. 1, p. 171; The Signal, July 16,

1915.

42. The Signal, July 16, 1915.

43. Ibid.

44. Order and Progress of the Work; The

Signal, November 12, 1915.

45. The Signal, November 22,

1915.

46. Ibid., November 26, 1915.

47. Ibid.

48. As quoted in The Signal, November

29, 1915.

49. The Signal, May 18, 1916.

50. Ibid.; and Hulbert, The

Cumberland Road, 75-77.

51. Second Economic Study, Ohio Post

Road, 11-19.

52. Ibid., 8-10.

53. Ibid.

54. Ibid.

55. Joint Report of the Progress of Post

Road Improvement, Postal Records.

56. United States Statutes at Large, XXXIX

(1916), 355. For the interpretation of

this act, see David F. Houston,

"The Government and Good Roads," Review of Reviews,

LIV (1916), 277-280.