Ohio History Journal

The Spanish-American War of 1898 was one of the most popular wars in American history. Americans emerged from the war completely victorious, and with few casualties. Images of the "yellow press" coverage of the sinking of the Maine, the hastily organized "army of volunteers," and Teddy Roosevelt's heroic charge up Kettle Hill have made their way into American popular culture. Over the course of the twentieth century, such images also inspired a movement to commemorate and memorialize what John Hay called the "splendid little war" by veterans' groups and women's auxiliaries. One of these groups, the Auxiliary of United Spanish War Veterans (AUSWV), formed shortly after the war's end in order to assist veterans and their families. The women of the AUSWV, working together in a social setting that helped develop true bonds of sisterhood, considered themselves to be guardians of American patriotism. They felt it their duty to convey these patriotic sentiments to others by distributing Americanism cards, donating flags, and acting as model citizens. Through elaborate rituals of commemoration, the AUSWV contributed to the creation of a public memory that helped shape popular conceptions of the Spanish-American War and in a larger sense influenced how we celebrate historical events today.

The development of a veterans' organization and an auxiliary was not unique to the Spanish-American War. Veterans' societies, from the Society of the Cincinnati after the Revolutionary War to the modern Vietnam Veterans of America, were formed after nearly every war in American history.1 During the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, it was

Angela O'Neal is an M.A. Candidate at Miami University of Ohio. This article is based on her honor's thesis at Kent State University. She would like to thank Shirley Wajda, Allan Winkler, and the Kent State University Honors College for their assistance.

1. Although the United States has been involved in Panama, Grenada, and the Persian Gulf since Vietnam, large-scale veterans' organizations have not yet materialized from these

Remembering the Maine

168

common for women's auxiliaries to form in support of these groups. The Women's Relief Corps and the Ladies Aid Society both attached themselves to the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) after the Civil War, and the American Legion (1913) and the Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW) (1919) each had women's auxiliaries. Serving as a bridge between these two distinct eras, the Auxiliary of United Spanish War Veterans was formed in the image of the GAR groups, yet had much in common with its contemporaries in the American Legion and Veterans of Foreign Wars.2 The patriotic organizations that arose after the Spanish-American War were based on their Civil War-era predecessors, but as time went on members of the younger generation created their own rituals, commemorations, and memories. Nonetheless, the United Spanish War Veterans (USWV) and the AUSWV commemorated the birthday of assassinated President William McKinley as the GAR had done with Lincoln years before, and they celebrated Santiago Day and Manila Day just as the victories at Gettysburg and Appomattox were won over again every year in the hearts and minds of Union veterans. The brevity of the war, the relatively small number of veterans, and the lack of good public relations strategies blocked the USWV and the Auxiliary from becoming as strong an influence as the GAR or its other twentieth-century descendants.

Unlike the women's societies formed around later veterans' groups, the AUSWV actually originated before the United Spanish War Veterans. During the Spanish-American War, a group of 125 women in Cleveland, Ohio, called "The Girls in White," served food, coffee, and cigarettes to soldiers on trains passing through to the warfronts in Cuba or the Philippines. When the war ended The Girls in White wished to continue their work by assisting veterans and their families as a way of commemorating the courage and self-sacrifice of the soldiers. The women considered their own role in the Spanish-American War to be equally, if not more, important than that of the soldiers. In the 1927 Ohio Auxiliary publication A Historical Review of the Auxiliaries, the women insisted that the soldiers

were not alone in their sacrifice for Humanity. This army of volunteers was nobly supported at home by another army, the women of our Country, who, though they were not permitted to carry a musket and enter the fight, yet stood shoulder to shoulder in their work of bringing relief and cheer into the various Camps of the Veterans.3

conflicts. However, veterans'

organizations have historically tended to form as veterans get older and seek

pensions benefits. Furthermore, veterans of Panama, Grenada, and the Gulf War

tend to join the VFW rather than form separate organizations.

2. Rodney G. Minott, Peerless Patriots: Organized Veterans and the Spirit

of Americanism (Washington, D.C., 1962), 4 1.

3. United Spanish War Veterans Auxiliary Department of Ohio, Our Ohio Story

1898-1906

Remembering the Maine

169

Women clearly recognized the importance of their work in the Spanish-American War. Like the male veterans, they probably wanted to remember their wartime sacrifices as well as maintain contacts with friends who shared the same experiences. By affiliating themselves with the United Spanish War Veterans, they were able to do more than remember their work: they could continue it. In a way, then, the female "army of volunteers" kept on fighting.

Soon after the war, The Girls in White changed their name to the Ladies' Military Escort. The change signified a shift in the ideology of the group. The title "Girls in White" called upon notions of pure, feminine young women waving their handkerchiefs and crying as their chivalric fathers, husbands, and brothers went off to battle, but the "Ladies' Military Escort," on the other hand, implied action. Women did more than wait for their men to return; they "escorted" them through their trials. The emphasis on military order and tradition may have also taken hold at this time. Curiously, a line in the AUSWV pamphlet "Our Ohio Story" refers to the fact that women were "not permitted to bear arms and fight," suggesting that they would have fought the Spanish themselves if given the opportunity.4

The Ladies' Military Escort was the first group granted a charter from the State of Ohio to organize relief work for the Spanish-American War veterans and their families. Its purpose was to serve the various veterans' organizations, which at that time included The Spanish War Veterans, The Spanish-American War Veterans, Legion of the Spanish War Veterans, and the Veteran Army of the Philippines. These groups formed independently at the end of the war, but all were dedicated to the same principles.5

The Ladies' Military Escort became the Auxiliary Army and Navy Spanish War Veterans in 1901 after joining forces with a similar group from Washington, D.C. This group held its first National Convention in Detroit, Michigan, in 1902. Isabelle Alexander of Cleveland, the founder of the Girls in White, was elected Senior Vice President and the following year she was elected President General. Because the Auxiliary was loosely attached to several veterans' organizations mentioned above, Alexander worked to consolidate them into a single organization. She was successful, and the official amalgamation occurred in 1904. Consequently, the National Auxiliary of United Spanish War Veterans was officially granted a charter by the United Spanish War Veterans on July 20, 1904. By 1905 the Auxiliary consisted of over 1500 members in fifteen states, with ninety-four

(Youngstown, Ohio, 1953),

14.

4. Our Ohio Story, 14.

5. Our Ohio Story, 14.

Remembering the Maine

170

Isabelle

Alexander formed The Girls in White, which distributed food and cigarettes

to soldiers on their way to fight in the Spanish-American War. After the war,

Alexander served as President General of the AUSWV from 1903 to 1905.

(Photo courtesy Lorain County Historical Society.)

chapters in Ohio alone.6 The complex relationship between the Auxiliary and the United Spanish War Veterans was formally described in the Constitution and Rules and Regulations of the Auxiliary of United Spanish War Veterans. Article VI stated that even though the Auxiliary was formally subordinate, the United Spanish War Veterans could only intervene in Auxiliary affairs in order to "prevent action . . . which might otherwise injure the good name of the United Spanish War Veterans, Incorporated, or prejudice its interest and activities." Furthermore, the Auxiliary was guaranteed "perfect freedom of action."7

The importance of independence to the Auxiliary seems unusual. By allowing the Auxiliary these freedoms, however, the veterans were able to distinguish between veterans and non-veterans as well as between men and women. Members of the United Spanish War Veterans had to prove that

6. United

Spanish War Veterans Auxiliary, Department of Ohio, A Historical Review of the

Auxiliaries, United Spanish War Veterans, Department of Ohio, 1900-1927 (Cleveland,

1927), 14-17. Our Ohio Story, 15.

7. A Historical Review of the Auxiliaries, 14, "Constitution and Rules and Regulations

of the Auxiliary of United Spanish War Veterans, Revised August 19-21, 1945,"

Major Woodworth Auxiliary of United Spanish War Veterans Papers, Lorain County

Historical Society, Elyria, Ohio (hereafter cited as AUSWV Papers).

Remembering the Maine

171

they served during the conflict, but Auxiliary members only had to show that they were related to a veteran.8 The Auxiliary women may have realized that although they shared many ideals with the veterans, the fundamental purpose of the two organizations differed. For example, the main goal of the veterans, to "unite in fraternal bonds," was not even mentioned in the Auxiliary Constitution. Social functions emerged among the Auxiliary members as well, but in order to legitimize their meetings, the Auxiliary had to meet for other reasons. The service-oriented nature of the AUSWV was obvious in its statement of the group's "Objects":

To extend aid and sympathy to all soldiers, sailors and marines of the Spanish-American War and their dependents; To cooperate with the United Spanish War Veterans, Incorporated, in all their work and social functions and to promote patriotism, humanity and proper reverence for the flag; To teach all love of Country; To promote interest in the National lnstitutions; To encourage observance of all patriotic days, and to inculcate everywhere, and at all times, lessons in good citizenship.9

Although the AUSWV was a national organization, a careful examination of the Major Woodworth Auxiliary Number 23 of Elyria, Ohio, reveals how it operated. Elyria, a small city located forty miles west of Cleveland, was typical of other cities with AUSWV chapters around the country. Drawing on the records of the Major Woodworth Auxiliary, it is possible to understand the interworkings of the organization as well as its change over time. Named after Major Charles Woodworth, an Elyria veteran of both the Civil War and the Spanish-American War, the Elyria chapter was average in both size and activity. Until the late 1940s the Major Woodworth Auxiliary maintained an average membership of fifty women. Meetings were held twice a month but members often met more frequently in each other's homes for card parties, sewing circles, and luncheons. 10

8. Female nurses were admitted

into the USWV. However, Mary J. Allen, the only female member of the Major Woodworth

Camp, tended to associate more with the Auxiliary. She played a marginal role

in the two organizations and never seemed to quite fit in to either one. This

seems to have been the case throughout the AUSWV. At the 1941 Department of

Ohio Convention, for example, the nurses' "headquarters" were in the hotel with

the Auxiliary rather than in the separate hotel for veterans.

9. "Constitution and Rules and Regulations of the Auxiliary of United Spanish

War Veterans, Revised August 19-21, 1945," 3-4, AUSWV Papers.

10. The most valuable primary source material for this study was the United

Spanish War Veterans/Auxiliary of United Spanish War Veterans Collection of

the Lorain County Historical Society in Elyria, Ohio. These documents include

officer and committee reports, minutes, official AUSWV histories, and handbooks.

Although this collection reveals a great deal about the AUSWV and the women

who were involved in the organization, journals and diaries are noticeably absent.

Records such as minutes and officer reports, though, often communicate an abundance

of personal commentary and opinion.

Remembering the Maine

172

The Creation of a Sisterhood

"Fraternity, Patriotism, and Humanity," the motto of the AUSWV, exemplified the goals of the Major Woodworth Auxiliary. Throughout its forty years of existence, the chapter proved its dedication to humanity by engaging in relief work for veterans, their families, and other people in need. Rooted in the ideology of Progressive reform, the women of the AUSWV sought to instill lessons of history and good citizenship in schoolchildren, immigrants, and each other through education. Over the course of their work, Auxiliary women created a social network in which members shared close ties, often over periods of many years. Social events were an important part of these relationships, but they went much deeper. Women of the Major Woodworth Auxiliary shared marriages, births, and deaths in what could truly be termed a "sisterhood." At the same time, the very actions of these women reinforced masculine ideals of virility, heroicism and superiority. Even the use of the masculine "fraternity" in the motto rather than the feminine "sorority" implied the conservative attitudes of the Auxiliary women.

The Elyria Auxiliary was originally mustered in 1910, but records do not exist for this period and there is no evidence that the group officially convened. In 1922, however, the Auxiliary reorganized. On May 17 of that year the Major Woodworth Auxiliary mustered in fifteen members and was formally granted a charter from the Department of Ohio on August 15.11 The successful passage of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1919 may have played a role in encouraging women to exercise their rights as citizens, thereby allowing women a greater interest in preserving the patriotic ideals of the nation. Furthermore, the Nineteenth Amendment may have convinced the public of the value of women in the public sphere. A simple matter of timing also had something to do with the success of the reorganized Auxiliary. A survey of the chapter's membership applications from the 1920s to 1940s shows that 53 percent of the members of the Major Woodworth Auxiliary were wives of veterans. Assuming that most of these women were in their late teens or early twenties when their husbands or future husbands went off to war, they would have been at least in their forties in 1922. For the most part, their children no longer needed constant attention and some had left home altogether. This left fewer responsibilities and therefore the time to participate in groups like the AUSWV. 12

11. A Historical Review

of the Auxiliaries, 12-204, 122, AUSWV Papers.

12. Since the Elyria AUSWV did not organize until 1922, there

is no evidence concerning their views on the suffrage movement. However, further

study on other auxiliaries may prove useful in determining how auxiliary women

felt on this issue.

Remembering the Maine

173

The twenty-fifth anniversary of the Spanish-American War in 1923 probably stirred up nostalgic feelings for many of the women who felt the need to commemorate the occasion. In addition, another 38 percent of Auxiliary members were daughters or nieces of veterans. For the organization to be viable, it needed as many women as possible, and the addition of daughters and nieces added a significant number of potential members. Since girls could not join the AUSWV until over the age of sixteen, few, if any, would have been eligible in 1910.13 After the reorganization, many women and their daughters joined the Auxiliary at the same time. As late as May 1936, for example, Mrs. Mary McLaughlin and her daughter Louise applied for membership. 14

The patriotic spirit that inspired women to join the AUSWV in the 1920s can be linked to a colonial revival that swept the nation in that decade. Unlike earlier revivals, the 1920s variety was not limited to the social and economic elite. As historian Karal Ann Marling explains, mass-produced "pseudo-antiques," such as Sears & Roebuck's Martha Washington sewing cabinets, flooded the market. Movies and novels based on the colonial era became popular as well as pageants that were commonly performed in towns throughout the nation. According to Marling, Americans looked to the past as a solution to an ever-changing society constantly under attack by "foreigners, strikers, and radicals of all stripes." Between World War I and World War II, Americans were fascinated with historic commemoration and preservation. Community historical societies and museums became popular, and large-scale projects such as the restoration of Colonial Williamsburg were completed. Improved railroads, highways and automobiles also allowed Americans greater accessibility to historic sites and cultural institutions. The past came alive for vacationers as highway markers noted historic sites, and motels, restaurants, and gas stations were built in the colonial revival style. In the words of historian Michael Kammen, the "democratization of tradition" became an important goal of the era. 15

The Major Woodworth Auxiliary was a part of this democratization process. To many women who had experienced the Spanish-American War, it was natural to attempt to recapture and memorialize their own past as evidence of true "Americanism." In The Past is a Foreign Country, historian David Lowenthal identifies certain "benefits" of remembering the

13. Membership Applications,

1922-1966, AUSWV Papers.

14. Minutes, 7 May 1936, AUSWV Papers.

15. Karal Ann Marling, George Washington Slept Here: Colonial Revivals and

American Culture, 1876-1986 (Cambridge, Mass., 1988), 190-97. Michael Kammen,

Mystic Chords of Memory (New York, 1991), 300-05.

Remembering the Maine

174

past that may further explain the need to commemorate the battles and deaths of the Spanish-American War by the AUSWV. First, memories of the past serve to restore "lost or subverted values and institutions." To the women of Elyria, the ideals of patriotism, honor, and self-sacrifice that were so prevalent during the Spanish-American War seemed to have been lost as new immigrants from Eastern and Southern Europe, who were pouring into the United States from the 1890s until the 1920s, were unfamiliar with the events of the war and with American culture itself. By distributing Americanism cards and participating in public ceremonies such as Memorial Day that affirmed loyalty to the flag and the nation, the AUSWV hoped to uphold, or restore, values the organization thought were on the decline. In the words of David Lowenthal, memories of the war era offered guidance to both new and old citizens by teaching lessons in "morals, manners, prudence, patriotism, statecraft, virtue, religion, [and] wisdom." 16

The "splendid little war" also offered an escape from the disturbing events of the day for some Auxiliary women. Nostalgic images of a nation united in support of liberty and justice against the purely evil Spanish were undoubtedly reminiscent of a much simpler time. Lowenthal explains, "in the yesterday we find what we miss today." Many of the women who created the Major Woodworth Auxiliary in 1922 were in their late teens or early twenties during the Spanish-American War. It was natural for these women to be drawn to the era of their youth and the ideals it represented. 17

Through their links with the past, the auxiliary women forged a distinct identity. Memories of what has happened before are necessary in contextualizing our existence, and the group environment of the Auxiliary allowed women to confirm their own private memories as well as fit them into the larger spectrum of the collectively remembered history. The notion of a collective memory, that individuals associated with a certain group have memories in common that have been developed over time, is necessary to understanding the development of the Major Woodworth Auxiliary. Sociologist Maurice Halbwachs stresses that it is "individuals who remember, not groups or institutions, but these individuals, being located in a specific group context, remember or recreate the past." Therefore, the organization of the AUSWV served not only as a way for members to recall their own memories of the past, but also allowed for the creation of a collective memory which integrated many ideas from different sources. 18

These ties were reinforced by the numerous rituals adopted by the

16. David Lowenthal, The

Past is a Foreign Country (Cambridge, England, 1985), 1 and 47.

17. Lowenthal, 38-51 and 49.

18. Maurice Halbwachs, On Collective Memory, Lewis A. Coser, ed. (Chicago,

1992), 81-83 and 22.

Remembering the Maine

175

AUSWV for meetings, social gatherings, and commemorations. The ritualistic activity of the Major Woodworth Auxiliary can effectively be termed a "civic religion." According to historian Barbara Truesdell, civic religion consists of two major dimensions: "an affective dimension [that] evokes emotional attachment to integrate individuals into a feeling of community, and a rhetorical dimension [that] directs the individual and the community into action in the service of the state."19 Historical places, rhetorical flourishes, commemorations and ideologies become symbols for civic religion. The Auxiliary, in this regard, recited the Pledge of Allegiance, marched to the "Star-Spangled Banner," celebrated national heroes such as Washington, Lincoln and Roosevelt, and commemorated twelve patriotic days.

The women of the Auxiliary quickly, and ritualistically, memorialized these patriotic days on the calendar. The twelve commemorated days were: William McKinley's Birthday (January 29), Sinking of the Maine (February 15), Muster Day (April 15), Declaration of War with Spain (April 25), Americanism Day (April 27), Manila Day (May 1), Memorial Day (May 30), Flag Day (June 14), Santiago Day (July 3), Independence Day (July 4), Surrender of Santiago Day (July 17), and Theodore Roosevelt's Birthday (October 27).

The events chosen fell in chronological order and the calendar read very much like a medieval book of hours. The "Book of Ceremonies" printed by the National Auxiliary detailed the proper rituals for observing these days. The state and national organizations encouraged local chapters to follow the written rituals, and each year the Department of Ohio held chapter inspections to ensure that local groups could successfully perform the "Book of Ceremonies." The Americanism Committee also organized events in honor of the birthdays of Lincoln, Washington and McKinley, and the Auxiliary often commemorated the birthday of Clara Barton, who had led the relief movement in Cuba. Events usually included speeches by members and veterans extolling the heroic accomplishments of the war, followed by entertainment. A typical celebration was held on February 19, 1926, when the Major Woodworth Auxiliary held a joint meeting with the veterans in observance of the birthdays of Washington, Lincoln and McKinley. Virginia Pope, the Patriotic Instructor, spoke on the life of Lincoln, while members Agnes Kothe and Annette Southam, respectively, spoke on Washington and McKinley. The only veteran to participate in the ceremonies was Comrade Edward Adams, who gave a speech on the twenty

19. Barbara Truesdell, "Exalting 'U.S.Ness': Patriotic Rituals of the Daughters of the American Revolution." In Bonds of Affection: Americans Define Their Patriotism, John Bodnar, ed. (Princeton, N.J., 1996), 274.

Remembering the Maine

176

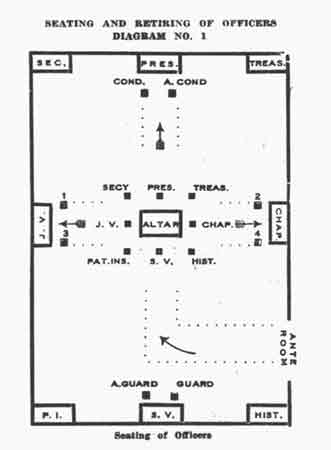

AUSWV meetings

were ritualized and often resembled military drills.

This diagram shows the proper procedures for seating and retiring of officers.

(Photo courtesy Lorain County Historical Society.)

eighth anniversary of the sinking of the Maine in Havana harbor. The program closed with the entire group singing "America" and "Battle Hymn of the Republic."20

The activities of a typical meeting exemplify the religious symbolism and fraternalism of the AUSWV. Meetings were punctuated with patriotic music and historical imagery. An intricate opening ceremony was performed before every meeting, beginning when the officers and color guards entered the room to a patriotic march as members stood at attention. The Color Guards performed a flag salute and the chapter's musician played the "Star-Spangled Banner." The "Ritual" pamphlet instructed members to listen to the music rather than sing the words. Following the recitation of the Americanism slogan in unison, the President announced the beginning

20. Minutes 1926-1927, AUSWV Papers.

Remembering the Maine

177

of the meeting and instructed the guards to close the doors. No one was permitted to enter until after the opening ceremony, and then only with special permission or knowledge of the secret password. The President then announced, "Sisters, we have assembled once more for the transaction of such business as may property come before this Auxiliary. May this meeting be of great good to all, and bind us closer as sisters. Let us again renew our loyalty to our Country, our Comrades, and our Auxiliary." Membership qualifications and goals of the organization were then recited by the Senior and Junior Vice-Presidents. The Auxiliary Chaplain read from the Bible as the Color Team performed a flag salute, and a code based on gavel taps by the President informed members when to sit, stand and salute.21

When required, initiation ceremonies took place approximately midway through the meeting. In order to become a member of the Major Woodworth Auxiliary, candidates filled out an application asking their affiliation with a veteran of the Spanish-American War. The initiation process spanned at least three meetings. First, the application was read and an Investigating Committee was appointed. Once the Committee acknowledged the candidate's qualifications and good character, members of the Auxiliary voted using a system of black and white balls, similar to that of the Masons. If a candidate did not receive any black balls, she would be initiated at the next meeting.

Initiation ceremonies began with candidates signing the Registration Book in the hall of the meeting room. They were then escorted to the altar by the Auxiliary Guard and Assistant Guard, where they took an oath to 11 remain true and constant in this sacred obligation." After a prayer by the Auxiliary Chaplain, the President spoke on the "vital importance of cherishing and cultivating the tic of sisterly love which should exist between yourself and the members of this Auxiliary." New members were given the Major Woodworth membership badge and Instruction Pamphlet and the members formed a greeting line to welcome their new "sister." Finally, the new member was seated among the old members and the meeting continued.22

Closing ceremonies were just as elaborate. With patriotic music playing and members standing at attention, the Patriotic Instructor and Conductors advanced to the altar. The Auxiliary then recited the Pledge of Allegiance

21. "Ritual," 1-12, AUSWV

Papers. Passwords were changed approximately every six months in the Major Woodworth

Auxiliary. To ensure secrecy, none were ever written down, and members appeared

to make a special effort to attend meetings on the day a new password was being

given out.

22. "Ritual," 18, 15-24, AUSWV Papers.

Remembering the Maine

178

to the flag. More music was played and the flag was retired. The Chaplain opened the Bible and read a prayer that invoked divine support for the Auxiliary as guardians of patriotism and protectors of the downtrodden:

Grant, 0 most merciful God, our Father, that the sacred principles of our Organization, which we honor in our thoughts, may be honored in our lives. Let the banner of Thy love be over our Country, that civil and religious liberty may be the inheritance of generations to come. Help us to be constant in our ministrations to all needy Comrades and the widows and orphans of those who fell in our most worthy cause, and let Thy kingdom come in all our hearts and Thy will be done in all our lives, that the name of our Father may be hallowed in all the earth. Amen.23

The meeting officially ended when the Color Guards retired the flags and the officers exited the room.

These rituals became an important part of the Major Woodworth Auxiliary. In 1930 the National AUSWV attempted to shorten the meeting ceremonies by cutting a few parts and modifying the elaborate flag routine, alterations which infuriated many chapters throughout the country. The Elyria Auxiliary appointed a Resolution Committee to draft a statement protesting the change. Since the women had already learned the first ritual, the Committee believed it was unnecessary to change it, especially since this change would lead to needless confusion. According to the Resolution Committee, removal of parts of ceremonies would be dangerous to the organization, causing "sisters to lose interest in their parts, and thereby lose interest in their beloved organization." The outcry against the new ritual was so strong that the National AUSWV began working on changes immediately. A new "Ritual" pamphlet was released in 1932.24

The rituals performed by the AUSWV reinforced social ties by creating shared experiences and thereby fostering a sense of camaraderie among these women. Rituals also reinforced the reasons for membership in the Auxiliary. Anthropologist Clifford Geertz explains rituals as "not only models of what [people] believe, but also models for the believing of it.25 When Auxiliary members recited their goals at the beginning of each meeting, it may have been, at a subconscious level, a way of legitimizing their reasons for gathering as well as a genuine reminder of what the organization hoped to achieve. Commemorations such as Muster Day reinforced the memories of feelings of patriotism, courage, and excitement

23. "Ritual," 18, AUSWV

Papers.

24. Minutes, 5 June 1930, AUSWV Papers. Only the 1925 and 1932 versions of

the "Ritual" pamphlet were found with the Auxiliary's papers, so there

is no evidence of the exact changes the National AUSWV was attempting

to make, It seems likely that the Auxiliary used the 1925 version until the

1932 version was released, since the pamphlets were worn and marked with notes

made during practices.

25. Clifford Geertz, The Interpretation of Cultures (New York, 1974),

114.

Remembering the Maine

179

|

Even the membership badges had militaristic overtones. This one was designed specifically for the Ohio AUSWV. (Photo courtesy Lorain County Historical Society.) |

men and women felt at the opening of the Spanish-American War. Muster Day celebrated these ideals and led to the continuation of support for the organization by reminding its members of their heroic struggle in the Spanish-American War.

The militaristic overtones of the AUSWV ritual certainly reminded the women of the Major Woodworth Auxiliary of the Spanish-American War, yet it was the soldiers' experience upon which the rituals built. The Color Guards in charge of the flag routines were reminiscent of army drills, as well as the actions of standing at attention and saluting officers. Even the Auxiliary membership badge resembled a soldier's medal. The use of military imagery evoked ideas of sacrifice, loyalty, and order that were essential to the belief system of the Auxiliary women and the tenets on which the organization was based. In some respects, the women of the AUSWV truly did consider themselves an "army of volunteers," only they were fighting a moral battle against the public's loss of memory of the Spanish-American War and the ideology for which they believed it was fought. The Major Woodworth's most important influences, however, were probably the members themselves, who by engaging in these elaborate rituals and commemorations created a sense of self-esteem through their relationship with the past. For the first time, many of these women identified themselves as Auxiliary President, Junior Vice-President, Historian, or Guard rather than wife, mother, or sister.26 Over time, rituals contributed to the production of a true sisterhood where members shared personal events of birth, marriage, and death.

Social events were key activities of the Major Woodworth Auxiliary. At the first meeting on September 20, 1922, the group decided to hold a social gathering "with cards, music, and dancing" at the next meeting in order "to boost membership." The Auxiliary offered women a chance to escape from the house and enjoy some leisure time two or three evenings a month.

26. Truesdell, 277.

Remembering the Maine

180

Women created a system of bonds that went far beyond the role of acquaintanceship and lasted a lifetime. For example, upon the marriage of member Freda Kothe, the Major Woodworth Auxiliary held a meeting resembling a bridal shower where the women had dinner and played games. Kothe received "a nice mirror" from the organization in addition to gifts from individual members. After her wedding the next day, the entire Auxiliary went to her mother's house to "see the wedding gifts" and visit.27

When Freda Kothe Bruck had a son in 1934, Auxiliary Secretary Sylvia Pope reported giving the baby a silver spoon, "as is customary ... for each new baby born to an auxiliary member."28 Members visited those who were ill, and elaborate rituals were held when a member died. Upon the death of Myrtle Wratton, the Auxiliary left her position as Conductor vacant for a month and "draped the charter" with an American flag in her honor. The Auxiliary also dedicated a poem to her memory.29

The Auxiliary Minutes record the death of charter member Anna Haake in 1947 along with the note, "an impressive memorial service was held at the Carl Taylor funeral home . . . by the ladies of the Auxiliary." What kind of service was it? How involved with the funeral arrangements were the women of the Auxiliary? The details are lost in the reporting of the Minutes, yet it is clear that the women were important to each other at all stages of life. In a way, the Major Woodworth Auxiliary served as a surrogate family for many of its members. It became a network of support for these women to lean on in times of crisis as well as an opportunity to socialize with people of similar backgrounds and beliefs.30

Americanism

The women of the AUSWV believed it was their duty to instruct others in the ideals of patriotism through their own experience during and after the Spanish-American War. The Americanism [Americanization] Committee was only one of the ways the Elyria Auxiliary achieved its goals. The chairman of the Americanism Committee was appointed by the President, but its members volunteered. Although it was important throughout the history of the organization, the Committee appeared to be most active during the trying times of 1936 to 1945 in which the Great Depression was followed by the Second World War. During that time, it ensured that local schools and libraries displayed the flag and contained books on American

27. Minutes, June, July,

and August 1925, AUSWV Papers.

28. Minutes, 6 December 1934, AUSWV Papers.

29. Minutes, March-September 1934, AUSWV Papers.

30. Minutes, 19 March 1926; AUSWV Papers, Minutes, 3 April 1947, AUSWV Papers.

Remembering the Maine

181

government. On several occasions, members passed out "Americanism cards" to men and women enrolled in naturalization classes. The cards were inscribed with the passage:

AMERICANISM

Americanism is an unfailing love of country; loyalty to its institutions and ideals; eagerness

to defend it against all enemies; undivided allegiance to the flag and a desire to secure the blessings

of liberty to ourselves and our posterity.31

In 1941, the Americanism Committee presented 100 Americanism cards to members of a local citizenship class that had "received their final papers and are being honored on Flag Day June 14 at a public ceremony given by the Elks order."32 The American Legion held citizenship classes for immigrants in Elyria, and the AUSWV Americanism Committee usually visited one or two classes per year in order to observe, serve refreshments, and pass out Americanism cards. It is doubtful that the distribution of Americanism cards played an important role in the assimilation of new citizens, but it is important that the Auxiliary women even made contact with immigrants in the 1930s and 1940s.

The Auxiliary also appointed a Patriotic Instructor to assist with education. She worked closely with the Americanism Committee to ensure that the Auxiliary commemorated important days. At the end of her one-year term, the Patriotic Instructor filed a report in which she was asked if the Patriotic Days had been observed. The Patriotic Instructor was also expected to be a model auxiliary woman for other members, and often enlightened other members by reading excerpts from the "Rules and Regulations and Rituals" and "Book of Ceremonies." In 1937, for example, Patriotic Instructor Annette Meinke read from the Rules and Regulations at ten out of twelve meetings in which her name was mentioned. At another meeting she read an article on Flag Day to the Auxiliary. In her annual report, Meinke was able to answer in the affirmative that all of the required patriotic days had been commemorated. She also proudly recorded the donation of four framed "Americanism slogans" to local schools. Meinke concluded her report with the remarks, "I have enjoyed my year's work as patriotic instructor and have tried to help and do my bit in every way."33

Annette Meinke was also an exemplary member of the Major Woodworth Auxiliary. During her term as Patriotic Instructor, she sponsored a Bingo fundraiser at her home, donated a pair of pillow slips that were sold to benefit the organization, sewed several changes of doll clothes

31. "Ceremonies," front

inside cover, AUSWV Papers.

32. Americanism Committee Report, 1941, AUSWV Papers.

33. Patriotic Instructor Reports, 16 December 1937, AUSWV Papers.

Remembering the Maine

182

for the Xenia Orphans' Home, and assisted with planning Memorial Day festivities. The significance of these duties is important. They are all consistent with the Republican Mother role in which women were expected to guide their husbands and children in the virtues of good citizenship. Annette Meinke's duties as Patriotic Instructor of the Major Woodworth Auxiliary, however, were all performed for the good of the organization and the community, rather than for the specific benefit of her family.

The Major Woodworth Auxiliary also held an annual essay contest for high school students on themes of patriotism, Americanism, and the Spanish-American War. In 1945, for example, students answered the question, "In what way did the Spanish-American War help to make World War II a success in the Pacific?" The contest was popular among Elyria schoolchildren during the 1930s and early 1940s. Twenty-seven essays were received in 1936 and prizes of five dollars and two dollars and fifty cents were awarded to the first- and second-place winners. Young Bruce McKinley McWilliams, son of an Elyria veteran and Auxiliary member, won the Major Woodworth Auxiliary's first prize as well as the Department of Ohio's award of ten dollars for 1935. His entry was then submitted to the national contest and considered for the grand prize of $100.34

The Historian also contributed to the educational goals of the Auxiliary. She was concerned with recording the Auxiliary's events and activities as well as monitoring membership roles, working with the Patriotic Instructor and Americanism Committee to observe patriotic days, and instructing members on the history of the Spanish-American War. Like the Patriotic Instructor, the Historian read articles and speeches at meetings. Again, the women who served in these offices fulfilled the instructive and educational goals of Republican Motherhood; yet instead of teaching their male children, they were teaching their auxiliary "sisters."

Beyond education, providing relief for veterans and their families was one of the primary activities of the Elyria chapter. The Auxiliary women sent cards, flowers, and fruit baskets to members and their families when they were ill. When a cold or flu outbreak hit Elyria in the winter of 1923, the Auxiliary President appointed "every member on sick committee." Women sent thousands of cards to hospitalized veterans and auxiliary members. In 1941 alone the Major Woodworth Auxiliary sent over 100 cards and letters to veterans and 200 to members. The women also donated money, clothes and supplies to hospitalized members and their families who needed them. In one case, the family of an Auxiliary member could not afford to pay her hospital bills, so the Major Woodworth Auxiliary arranged to have the hospital bill "canceled." Whether the Auxiliary paid the bill or

34. Department of Ohio General Orders, 22 May 1946, AUSWV Papers.

Remembering the Maine

183

persuaded the hospital to forfeit is unknown.35 For nearly every year in its history, the Major Woodworth donated money and supplies to the Ohio Soldiers' and Sailors' Orphans Home in Sandusky, Ohio. Women made dolls to send to the girls at Christmas time and several other times during the year, and they periodically sent skates, books, and other toys. For larger relief or charity projects, the Auxiliary usually donated money to the Department of Ohio, the regional level of the AUSWV organization, where it was pooled together with contributions from other Ohio Auxiliaries.

The Depression years were the most active for the AUSWV in terms of relief work, due both to necessity and large membership. While fifty Elyria women were AUSWV members in 1928, the number jumped to sixty-eight after the stock market crash of 1929. The Major Woodworth Auxiliary averaged sixty-eight members from 1929 to 1939, and it peaked at seventy-six members in 1935, the depth of the Great Depression. It is surprising to note the popularity of club membership at a time when money was scarce, but on average club dues were much cheaper than movies and other popular pastimes. The Auxiliary women, who often met in each other's homes for sewing circles, card parties, and luncheons, probably sympathized with Fern Yowell of Kansas, the founder of a relief organization called the Community Helpers, who wrote, "When you had the club in your house it was just the biggest thing that happened to you all year." Furthermore, Auxiliary membership could have been seen as an economic and emotional insurance policy that became even more important in the unstable decade of the 1930s.36

Child Welfare Committee Chairman Anna P. Kothe recorded that in 1932 alone the Auxiliary supported thirteen children in three local families. Women made clothes for the children while proceeds from bake sales, cards, parties, and raffles bought milk and food. At another point, the Auxiliary made baby clothes and supplied milk to a downtrodden family for two months. Between 1932 and 1934 the women of the Major Woodworth Auxiliary sewed over 200 children's garments for the poor. The December 6, 1934, Minutes described a typical family receiving relief from the Auxiliary. The father had been confined to bed due to injuries received

35. Minutes, 21 February

1923, Hospitalization and Soldiers Home Report, 15 May 1941, Hospitalization

Report, 6 June 1935, AUSWV Papers.

36. Studs Terkel, Hard Times: An Oral History of the Great Depression (New

York, 1970), 346. Inspection Reports, 1928-1941, AUSWV Papers. An initiation

fee of $1.50 was charged to all new members. Throughout the 1930s, dues were

one dollar per year. Members' could be suspended for not paying their dues,

and there are reports of such occurrences in the Minutes. The National AUSWV

often held "membership drives" at which women who had failed to pay their dues

could be readmitted into the organization without having to pay the delinquent

dues. This practice was especially common in the 1950s and 1960s when the AUSWV

seriously began to lose members. The Major Woodworth Auxiliary periodically

waived dues for members who were having serious financial difficulties.

Remembering the Maine

184

when he "was thrown from a machine" and the mother was unable to find work. The youngest of the family's four children was disabled. Income from the older children's jobs and the father's slim compensation amounted to only six dollars per week. When Richard Moffet, the son of an Elyria World War I veteran, was unable to return to classes at Athens College (later Ohio University) due to his family's circumstances, the Major Woodworth Auxiliary joined forces with the Veterans' Camp and the American Legion to raise the money the boy needed.37

After World War II, however, participation in the Elyria AUSWV began to decline. Bloody images of combat in places like Normandy and Guadalcanal, not to mention the dropping of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, left Americans fully aware of the brutality of war and made it much more difficult for the members of the AUSWV to glorify the seemingly innocent Spanish-American War. The declining trend of the Elyria Auxiliary reflected that of the National AUSWV as it began to lose members by death and simply lack of interest. By 1956, the Major Woodworth Auxiliary had changed dramatically. Dues-paying membership declined to twenty-eight, and the organization held only one meeting per year. The Americanism Committee and the Legislation Committee, which primarily served to inform members of new pension legislation, were the only two committees formed. The question concerning the recitation of the ritual was left blank on the Inspection Report, implying that attempts were not even made to follow it. The following year the auxiliary ceased holding meetings entirely. In addition, the officers remained virtually unchanged for the next ten years. Although the auxiliary averaged fourteen members from 1957 to 1966, only five people were "elected" officers. 38

Scott Hinman, the last member of Major Woodworth Camp Number 62, died in 1966. A carpenter from Rochester, Ohio, Hinman had served in the Spanish-American War in Tampa, Florida. His death was recorded in the minutes of the Auxiliary of United Spanish War Veterans, which read: "July 1966—Flowers were sent to the Funeral Home for Scott Hinman—86 years old and the last member of Major Woodworth Camp No. 62—also was a charter member."39

Both the Camp and the Auxiliary disbanded upon Hinman's death. It appears, however, that the Major Woodworth Auxiliary ceased to be a viable organization in 1956, ten years before it was officially disbanded. These women knew that the organization was defunct, yet they continued to pay

37. Minutes, 19 December

1924, Child Welfare Reports, 1932-1935, Minutes, 6 December 1934, Minutes, 20

June 1935, AUSWV Papers.

38. AUSWV Inspection Reports, 1925-1960, AUSWV Papers.

39. Minutes 1947-1966, AUSWV Papers.

Remembering the Maine

185

dues to the National Auxiliary and promote patriotism by placing "Americanism plaques" in schools and government buildings. The remaining members also provided a valuable service by ensuring that deceased veterans received proper recognition at their burial and assisting widows with pension benefits. Ironically, this may have been the most significant work accomplished by the Major Woodworth chapter. To the end, the women of the Major Woodworth Auxiliary exemplified their own ideals of patriotism, loyalty, and benevolence that superseded the formal structure of the organization.

Conclusion

Throughout its forty-four-year history, the United Spanish War Veterans Auxiliary was devoted to preserving the memory of the Spanish-American War and the men who fought in it. Its members were active in the organization throughout their lives and tended to be extremely loyal. Sylvia Pope, who joined the AUSWV in 1924 and served as Historian, Patriotic Instructor, Secretary, and President during her lifetime, is a prime example. After her husband's death in 1964, she took over as the Adjunct General of the United Spanish War Veterans Camp and, in 1966, eighty-two years old and confined to her room at Oak Hills Nursing Home, she wrote to the Department of Ohio informing them of Hinman's death and the impending disbandment of the organization. Pope died less than a year later. To keep Auxiliary proceedings secret, the AUSWV Constitution stipulated that Auxiliary documents should be destroyed after a chapter disbands, but Sylvia Pope's records survived and were placed in the Lorain County Historical Society.

Memories of the Spanish-American War sustained these women throughout their lives. Sensationalist newspaper reports of the war were ingrained in their minds. They remembered the intense wave of patriotism inspired by the war in their collective memory, and they attempted to recreate their wartime feelings through patriotic rituals and commemorations. As guardians of American patriotism, the women of the Major Woodworth Auxiliary believed it was their duty to preserve the memory of the war and inculcate patriotism in others. Americanism cards represented these ideals and were therefore distributed to immigrants, schoolchildren, and the lower classes in an attempt to instill in them feelings of patriotism, loyalty, and unity. In doing so, the AUSWV played a role in the creation of public memory. Although the Spanish-American War itself may not have been remembered, many of the patriotic rituals certainly were.

The Major Woodworth Auxiliary is representative of the many national

Remembering the Maine

186

patriotic organizations that have formed in the United States. The story of this organization is important to the study of memory, patriotic groups, and women in the twentieth century. The colonial revival spirit, nostalgia concerning the twenty-fifth anniversary of the war, and the existence of leisure time led to the creation of the Major Woodworth Auxiliary in 1922. The formation of a collective memory was visible in the early years of the organization and played a major role throughout its existence. Because of their experiences during the Spanish-American War, the Auxiliary women considered themselves to be curators of American ideology and therefore placed themselves in charge of promoting "Americanism" to immigrants, schoolchildren, and the poor. While the national impact of the AUSWV's Americanization program was muted, it is certain that the Auxiliary deeply affected the women who were members. The Major Woodworth Auxiliary provided women with a sense of purpose and self-esteem in addition to a close-knit network of support. The women of the Auxiliary represented a conservative element essentially rooted in nineteenth-century ideals, despite the fact that the women of the Major Woodworth Auxiliary organized soon after the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment. Their role as "auxiliary" to the male veterans ironically placed them in the position of upholding the patriarchal society that many Progressive-era women hoped to eliminate.

The Major Woodworth chapter of the AUSWV provides a way to explore issues of gender, commemoration, and leisure. These issues are crucial to our historical understanding, not only of patriotic organizations such as the AUSWV but of the cultural system of the first half of the twentieth century and its implications for the present. For the women who were members of the AUSWV, the organization provided friendship, purpose, and security that sustained them over the forty years the organization existed. Even though the AUSWV has long since disbanded, its legacy lives on in the women's auxiliary groups that still exist today, in the popular images of the Spanish-American War, and in patriotic commemorations of Memorial Day and the Fourth of July.