Ohio History Journal

PARTY POLITICS IN OHIO, 1840-1850*

BY EDGAR ALLAN HOLT, B. A., M. A.,

PH. D.

PREFACE

It has been my purpose in this study to

trace the po-

litical history of Ohio during the

'forties in relation to

state and national problems. The period

under investi-

gation affords an interesting cross

section of American

political history, revealing appeals to

party prejudice,

conflicting economic and social

interests, political ma-

nipulations and

"log-rollings," and the emergence of the

Northwest as a powerful section

demanding in vigorous

terms a new consideration in the

councils of the Na-

tional Government. The period also

marks the growing

divergence of northern and southern

interests which

ended in the Civil War, for the

Northwest, like the

South, was developing a peculiar

sectionalism which

threatened the integrity of the Union.

Ohio's economic

interests and the personal ambitions of

her political lead-

ers seemed to be menaced by southern combinations.

The press of both parties breathed open

defiance to the

slaveholder, although the wealthier

classes of southern

Ohio deprecated the agitation of a

question which threat-

ened their commercial connections in

the South. Prob-

ably of greater importance was the

growing conflict be-

* Dissertation presented in partial

fulfillment of the requirements for

the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in

the Graduate School of the Ohio

State University.

(439)

440

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

tween the masses of the people and the

privileged classes.

Although Ohio had lost many of the

characteristics of

a frontier state, the followers of

Jackson still dominated

this commonwealth at the opening of the

decade. This

control was only temporarily challenged

by the fantastic

Whig Log Cabin campaign of 1840 and the

Democracy

reasserted its power within a year

after that episode.

But the growing conservatism among the

professional

classes and men of wealth during this

decade prevented

the Democratic party from advocating

extreme meas-

ures and transformed the Whig party

into a still more

reactionary organization. Throughout

the decade the

struggle of the radicals and conservatives

furnished the

underlying motive on state issues. If

the Liberty and

Free Soil parties aided the forces of

liberalism, this was

not because a majority of those parties

favored a greater

degree of democracy, but because these

minor parties

tended to break up the conservative

Whig party, and thus

enabled the radical elements to realize

their program.

My materials have been drawn from the

Ohio State

University Library, the Library of the

Historical and

Philosophical Society of Ohio, the

Library of the Archae-

ological and Historical Society of

Ohio, the Library of

Congress, and the Library of the

Pennsylvania Histori-

cal Society. The officials of these

institutions have been

most helpful in placing their materials

at my disposal.

I wish to acknowledge my obligations

and express

my deep appreciation for those who have

directed my

studies either in the way of helpful

advice or formal in-

struction. I owe especial obligations

to Professor Carl

Wittke, of the Ohio State University,

who directed the

course of my researches, for his kindly

advice on the

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society

Publications 441

gathering of the materials for this

study and for his

helpful and penetrating criticisms of

the dissertation it-

self.

EDGAR ALLAN HOLT,

Ohio State University,

June, 1928.

CHAPTER I

THE ELECTION OF 1840 IN OHIO

Ohio, the first fruit of the Ordinance

of 1787, en-

tered the Union in 1803. By that

Ordinance, it was de-

termined that Ohio's economic growth

should be based

on free rather than slave labour. This

factor became

the basis of the later alignment of the

State in opposi-

tion to the South. However, the

proximity of Ohio to

slave-holding States forced it to adopt

a conciliatory pol-

icy toward the slave system in order to

retain close com-

mercial relations with the South.

Throughout the early

history of the State, southern Ohio and

particularly Cin-

cinnati, the commercial metropolis of

the State, were

anxious to ally the economic and

political interests of

Ohio with those of the South.

Richly endowed with a fertile soil and

numerous

streams suitable for navigation, Ohio

experienced a

rapid growth in wealth and in

population. Although

this economic development was primarily

agricultural,

thriving factories soon grew up at such

points as Cin-

cinnati, Zanesville, Chillicothe, and

Steubenville. After

the completion of the Erie Canal in

1825, Cleveland

became the entrepot of raw farm

products from north-

ern Ohio destined for New York and the

distribution

point of eastern manufactured products

bound for the

Northwest.

The expansion of the factory system in

Ohio, which

resulted from the federal tariffs of

1816, 1824, and 1828,

led to a demand for an extended market.

The commer-

(442)

Party Politics in Ohio,

1840-1850 443

cial needs of southern Ohio were met by

the southern

slave system which afforded a market

for the food sup-

plies and manufactured products of the

Ohio Valley.

This situation produced an economic

alliance between

southern Ohio and the slave states

which explains much

of the political differences between

the former and

northern Ohio which was bound to New

York by com-

mercial ties.

Up to 1850 the tremendous development

of the

wealth of Ohio was due largely to the

construction of

a network of one thousand miles of

canals through

thirty-seven counties, connecting Lake

Erie and the

Ohio River by two continuous routes,

one with termi-

nals at Cleveland on the Lake and

Portsmouth on the

Ohio and the other joining Toledo and

Cincinnati. By

1850, Ohio ranked third among the

states in the cash

value of her farms, Cincinnati was the

chief packing

center in the West, the annual value of

the products of

the gristmills and sawmills of Ohio was

more than

$9,000,000, and the total capital

investment of the State

in banking institutions and in the

manufacturing of such

articles as hardware, iron, crockery;

and in the packing

of meats, had grown from $4,000,000 in

1822 to $28,-

000,000. At the same time the

population had increased

to 2,000,000, most of whom were located

in counties

served by Lake Erie, the Ohio River,

and the canals.

In 1850, Cincinnati had a population of

115,000 drawn

from all parts of the United States and

Europe, and

Hamilton County held almost one-third

of all the Euro-

pean immigrants who came to the State.

The source of Ohio's population

determined the

political history of the State,

producing sectional lines

444

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

almost as marked as those dividing the

sections from

which each of the elements came. One of

the largest

single elements entering into the

racial composition of

the State's population was the

Scotch-Irish frontiersmen

of Pennsylvania, Virginia, and

Kentucky. The Scotch-

Irish from Pennsylvania overflowed into

central and

eastern Ohio in quest of fertile lands

as soon as the

region was opened to settlement, while

those from Ken-

tucky settled in the southern portion

of the State. The

latter were composed largely of the

poorer, more demo-

cratic and non-slave-holding classes of

the South, many

of whom were opposed to slavery and all

of whom were

anxious to better their economic

situation. Chaddock

asserts that "The influence of

this Scotch-Irish stock in

southern Ohio was very marked. They

brought with

them their religion; they asserted

their ideas of indi-

vidual freedom and economic

independence, and they

supported the political principles of

Jefferson and the

rising democracy."1 Another

element was the Germans,

who came in large numbers both from

Pennsylvania as

a part of the frontier class, and,

during the 'forties, di-

rectly from Germany. Although scattered

over the

State in respectable numbers, a large

proportion of the

Germans settled in Cincinnati. Most of

them formed a

close political alliance with the

Scotch-Irish followers of

Jefferson and Jackson, opposing

corporate interests and

a high protective tariff during the

later 'thirties.

Another, but smaller element, was the

Quakers who

came to Ohio from Virginia and North

Carolina as a

result of their lack of sympathy with

the slave system.

1 Robert E. Chaddock, "Ohio Before

1850," in Columbia University

Studies in History, Economics and

Public Law, v. XXXI, p. 33.

Party Politics in Ohio,

1840-1850 445

Probably the most distinctive

contribution in this mix-

ture of Ohio's population was the

settlement of New

Englanders on the Western Reserve. As a

result, the

Reserve became the backbone of

opposition to Jeffer-

sonian and Jacksonian Democracy until

1848 when the

voters of that section became convinced

that the Whig

party was the tool of the "slave

power."

From the earliest days of its

organization as a State,

Ohio was dominated by the followers of

Jefferson. This

unanimity of sentiment tended to

disappear after 1812,

and crystallized into definite

political parties after 1824,

when the economic needs of the West

enabled Clay and

Adams to unite the East and West in

behalf of a pro-

gram calling for a high protective

tariff and internal im-

provements.2 This coalition

threatened to dominate the

political situation, but the frontier

character of Ohio

made its conquest by the Jacksonian

Democracy a com-

paratively easy task. The masses of the

people, filled

with the frontier dislike for banking

institutions, rallied

behind Jackson in his war on the United

States Bank.

But as Ohio increased in wealth, the

conservative forces

gathered strength and began to oppose

the levelling ten-

dencies of the Democracy with some

degree of success.

Moreover, Jackson's popularity did not

descend to Van

Buren, his designated successor, and

the Panic of 1837

prepared the way for a general debacle

in the ranks of

the Democracy.3 To the Whigs, it

appeared that the

2 Eugene

H. Roseboom, "Ohio in the Presidential Election of 1824,"

in Ohio Archaeological and Historical

Publications, v. XXVI, pp. 153-224.

3 For a resume of the political

situation in Ohio before 1840, I have

relied upon Eugene H. Roseboom's

"Ohio Politics in the 1850's," a doctoral

dissertation in the course of

preparation at Harvard University. See also

Chaddock, op. cit., in Columbia

University Studies in History, Economics

446 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

widespread distress which resulted from

that panic was

caused by the Democratic program of a

"war on the cur-

rency." The Whigs therefore hoped

to appeal for sup-

port to an increasingly large number of

laborers thrown

out of work by the effects of the

financial depression

which continued throughout the

remainder of Van

Buren's term.

The Van Buren administration had

scarcely begun

in 1837 when the opposition party began

to lay plans for

the next campaign.4 The problem for the

Whigs was to

unite under one leader the discontented

Democrats, the

land tenants of New York who were

dissatisfied with

the old patroon system, the

abolitionists, the friends of

Harrison, Clay and Webster; and those

along the north-

ern border who felt that Van Buren was

a tool of the

British because he had not avenged the

burning of the

Caroline.5

This incident grew out of the efforts

of Canadian

revolutionaries in 1837 to obtain

American aid. The

Caroline, an American vessel, which had been engaged

in carrying supplies from Fort

Schlosser, New York, to

the Canadian rebels on Navy Island, was

boarded and

burned on the American side of the

Niagara River by

Canadian military authorities.6 There

was intense ex-

and Public Law, v. XXXI; Homer J. Webster, "History of the Demo-

cratic Party Organization in the

Northwest," in Ohio Archaeological and

Historical Publications, v. XXIV, pp. 1-120; Homer C. Hockett, Western

Influences on Political Parties to

1825.

4 A

convention of the Ohio Whigs as early as 1837 suggested a national

convention for the following year to

select candidates for the campaign of

1840. Niles' Register, v. LII, p.

329.

5 McMaster, John Bach, A History of

the People of the United States,

v. VI, p. 550.

6 Ibid., v. VI, pp. 440-441.

Party Politics in Ohio, 1840-1850 447

citement all along the northern border

over this incident

and because of the arrival of Canadian

political refugees

in the border towns, and the Whigs

seized the oppor-

tunity to charge the Democrats with

being pro-British.

A war with England was happily averted

by Van Buren

who pursued the wise policy of

enforcing strict neutral-

ity along the border. To these

discontented elements

whom the Whigs sought to unite, must be

added large

numbers of voters who blamed the Panic

of 1837 upon

the Van Buren administration. Although

the first po-

litical effects of the panic naturally

were disastrous to

the party in power, a distinct reaction

set in in favor of

the administration as the years passed.

In New York

a Whig majority of 15,000 in 1837 fell

to 10,000 in 1838

and to 5,000 in 1839.7 In Ohio, the

political current was

running in the same direction and the

Democrats won

the state elections of October 1838 and

1839 on a policy

of bank reform.8

Early in 1838, the Ohio Whigs began to

put their

faith in William Henry Harrison as the

one candidate

who could unite under his banner all

the forces in oppo-

sition to the Van Buren administration.

In January,

1839, the Belmont Chronicle put

the slogan, "For Presi-

dent: William H. Harrison, Subject to a

National Con-

vention," at the head of its

editorial column.9 The

Whig State Convention of 1838 also

endorsed Harrison,

subject to the action of a national

convention, but prom-

ised that the Whigs of Ohio would be

satisfied also with

7 Greeley,

Horace, Recollections of a Busy Life, p. 129.

8 Ohio Statesman, October to November, 1838; Ibid., October to

November, 1839.

9 January 1, 1839.

448 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

Clay or Webster.10 The

Cincinnati Republican, a for-

mer Jackson paper edited by James

Allen, came out so

uncompromisingly for Harrison that it

was warned by

the Whig organ of the State to be more

circumspect in

order not to antagonize the Clay Whigs

of the State.11

The Whig program in Ohio was primarily

one of

unification. Availability, not

principle, was the essen-

tial quality sought in prospective

candidates. James

Allen,12 in control of the Ohio State

Journal since April,

1839, deplored the "unfortunate

centrifugal tendency"

in the Whig party. "To be

successful" in 1840, Allen

declared, "nothing must be

hazarded that shall tend,

however remotely, to increase the

dissonance and disaf-

fection that, just now, disturb our

ranks."13 On April

19th, the Ohio State Journal announced

that it would

support William Henry Harrison. The

Whigs were

agreed that it would be wise to

concentrate early on one

candidate, and thus prevent trouble

between the follow-

ers of various rivals.

The friends of Webster were not without

some hope

of securing support in Ohio for their

favorite, but Wil-

liam Greene, a prominent Whig leader of

Cincinnati,

assured them that western sentiment

demanded a west-

ern candidate. In reply to queries as

to what pledges

10 Ohio State Journal (Semi-weekly),

May 10, 1839.

11 Ibid., April 26, 1839.

12 Allen stated that when he was

editor of the Cincinnati Republican

he endorsed Jackson's vetoes and abused

Hammond of the Gazette "with

a political unction that must have been

truly edifying to the enemies of

poor Nick Biddle." When Jackson

removed the deposits from the United

States Bank in 1834, Allen resigned as

editor of the Republican because he

disapproved of the removal. He then

raised Harrison's name over the

editorial columns of the Cincinnati Courier,

the first Harrison paper in

Ohio. Ohio State Journal (Semi-weekly),

April 26, 1839.

13 Ohio State Journal, (Semi-weekly), April 12, 1839.

Party Politics in Ohio,

1840-1850 449

Harrison would make concerning Webster,

Greene skil-

fully replied that "He does not

choose to pledge himself

to any human being . . . nor will he say what he

would probably do. But there are

delicate modes of

intimation which have, if possible, more

than the au-

thority of express terms--and my

opinion is (and I be-

lieve no human has better means of

forming a correct

one upon this particular) that if the

General be elected

to the Presidency, he would not only prefer,

but rely

upon it, that Mr. Webster should hold

the first place in

his cabinet relations."14

Although the Whig State Central

Committee, on

May 21, 1839, in an official call for

delegates to a Na-

tional Convention in Harrisburg six

months later, gave

its support to Harrison,15 the

Clay forces of Ohio, led

by Charles Hammond, were not ready

before October

to admit the defeat of their hero.16 The Cincinnati

Daily Gazette refused to join in the hue and cry for

Harrison, and during Clay's tour in the

Northeast

printed daily accounts of his speeches

and triumphal re-

ceptions.17 Clay's candidacy seemed to gather strength

until he reached Saratoga. Here he met

Thurlow Weed,

who informed him that he could not

carry New York

and that for the good of the party he

should withdraw

from the contest.18 It was impossible

to stem the Har-

14 Greene to

Lovering, May 28, 1839, Greene MSS.

15 Ohio State Journal (Semi-weekly), May 21, 1839. The members of

the State Central Committee were Alfred

Kelley, chairman; Joseph Ridg-

way, Warren Jenkins, Lewis Heyl, and

Samuel Douglass.

16 Cincinnati Daily Gazette, October 4, 1839.

17 Ibid., August 16, September 3, 1839.

18 McMaster, op. cit., v. VI, p.

555.

Vol. XXXVII--29.

450 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

rison current.19 Clay was not deserted

on account of a

lack of faith in his program but on

grounds of political

expediency. Union was necessary and it

seemed un-

likely that Clay could unite all the

fragments of the

opposition. The Cincinnati Daily

Gazette, moreover,

frankly acknowledged that "Clay is

not popular with the

people, a fact demonstrated twice, in

direct appeals to

their suffrage. Then, as now, his friends

stood stiff in

pertinacity--ought they now after two

signal defeats,

to press their favorite again, without

some tangible, in-

disputable change of position,

favorable to his success."

As a fatal objection to Clay,

especially for the Jackson

men whom it was necessary to

conciliate, was the per-

sistent charge of "the corrupt

bargain" of 1824, when

Clay had turned his strength to Adams

and helped to

defeat Jackson for the presidency.20 Harrison

leaders

paid fulsome compliments to Clay in

order to take away

the sting of defeat and obtain the

support of his follow-

ers.21 The middle ground

taken by the Ohio State Jour-

nal in the interest of a perfect reconciliation of all

fac-

tions was somewhat distasteful to the

Clay papers in

northern Ohio and to the rabid Harrison

papers in the

southern portion of the State;22 but as the

summer wore

on, the former fell into line for

Harrison.23

There was some sentiment in the State

for Winfield

19 The Carroll Free Press in

May declared that Harrison was more

popular with the "bone and

sinew" than any other man whom the Whigs

could name. Carroll Free Press quoted

in Ohio State Journal (Semi-

weekly), May 14, 1839.

20 Cincinnati Daily Gazette, October

4, 1839.

21 Chillicothe Gazette quoted in Ohio

State Journal (Semi-weekly),

May 14, 1839; Circleville Herald quoted

in Ohio State Journal (Semi-

weekly), May 10, 1839.

22 Ohio State Journal (Semi-weekly),

May 31, 1839.

23 Ibid., June 4, 1839.

Party Politics in Ohio,

1840-1850 451

Scott, but the Ohio State Journal shared

the view of the

Baltimore Chronicle that it was

too late to introduce new

and untried champions into the field.24 Oran Follett,25

a Clay Whig, considered Scott a good

candidate to at-

tract former Jackson Democrats, after

he saw that there

was no enthusiasm among the Whigs of Ohio for his

favorite. In September, as a delegate

to a district con-

vention to name representatives to the

Harrisburg Con-

vention, Follett had announced his

preference for Clay

as the most politically available

candidate.26 Hardly

two weeks later, Follett was urging

George H. Flood of

Virginia, a Democrat, and James T.

Morehead, a for-

mer Whig governor of Kentucky, to

support General

Scott, apparently on the ground that

Clay could not win

for the party in 1840, because the

anti-Administration

Democrats would not rally to his

support.27 The Scott

candidacy was never very significant in

this State, and

by November only two papers in Ohio,

the Conneaut

Gazette and the Sandusky Whig (edited by Follett)

were openly in favor of Scott's

nomination.28 The se-

lection of delegates to the Harrisburg

Convention re-

vealed an overwhelming sentiment for

Harrison in Ohio.

By November, 1839, of the one hundred

Whig papers

24 Ohio State Journal (Semi-weekly), April 12, 1839.

25 Follett was a staunch Whig leader in

Ohio throughout the decade.

Originally from New York, he became,

upon removal to Ohio, editor, first

of the Sandusky Whig and then of

the Ohio State Journal, and later a

leader of the Corwin movement for the

presidency.

26 Follett and Camp to the chairman of

the District Whig Convention,

September 30, 1839, quoted in

"Selections from the Follett Papers, IV" in

Quarterly Publications of the

Historical and Philosophical Society of Ohio,

1916, v. XI, No. 1, pp. 15-16.

27 Follett to Morehead, October 18,

1839, quoted in "Selections from

the Follett Papers, IV," loc.

cit., v. XI, No. 1, pp. 18-20.

28 Ohio State Journal (Weekly), November 13, 1839.

452 Ohio Arch. and Hist.

Society Publications

in the State, five supported Clay, two

clung to Scott,

and the rest favored "Harrison and

Reform."29

The defeat of the Whigs on the banking

and currency

issue in the fall elections of 1839

created havoc in the

party in Ohio, and led Follett to

comment bitterly on the

"state of the public morals, the

heresies in government,

and the ignorant prejudices of the

multitude in relation

to the Treasury . . ."30 The chief issue between the two

parties in 1839 had been one of the

extent to which the

government should go in regulating the

banks of the

State, which had undergone a succession

of failures

since 1837. The Democrats favored a

vigorous program

of reform but the Whigs were inclined

to defend the

banks, asserting that their opponents

really intended to

destroy the currency.31 The

defeat of the Whigs was

attributed to various forces. The St.

Clairsville Chron-

icle blamed the supineness of the Whigs,32 and

the Cin-

cinnati Gazette refused to close

its eyes to the fact that

the party was prostrate, and suggested

that the Harris-

burg Convention fold up the Whig

banners forever.33

In spite of such pessimistic

conclusions, delegates

were appointed to the Whig National

Convention at

Harrisburg. Foremost among the

representatives from

Ohio were Jacob Burnet, of Cincinnati;

Reasin Beall,

of Wooster; the sturdy John Johnson, of

Piqua, who

29 Ohio State Journal (Weekly), November 20, 1839.

30 Follett to Morehead, October 18,

1839, quoted in "Selections from

the Follett Papers, IV," loc.

cit., 1916, v. XI., No. 1, p. 19. The Ohio State

Journal exclaimed in despair that "It seems like madness

to contend against

an overwhelming fate--against a force

that is sure to crush us." Ohio

State Journal (Weekly), October 16, 1839.

31 See Chapter II.

32 Ohio State Journal (Weekly), October 16, 1839.

33 Cincinnati Daily Gazette, November

7, 9, 1839.

Party Politics in Ohio,

1840-1850 453

rode to Harrisburg on horseback; and N.

G. Pendleton,

of Cincinnati, who served on the

committee to select

the officials of the Convention. When

the Convention

assembled, Clay had the greatest number

of pledged

delegates, but there were indications

that the political

managers were not willing to have him

lead the party

again in 1840. On the second day of the

balloting,

New York, Michigan, and Vermont

transferred their

support from Scott to Harrison and thus

brought about

his nomination, much to the

satisfaction of the Ohio

delegates, who had voted steadily for

their favorite son.

The Convention then nominated John

Tyler of Virginia

for vice-president.34 The

Convention recommended a

rally of the Whig young men of the

nation at Balti-

more and then adjourned, without

drawing up an

address to the people or framing a

platform.35 This

proved to be good political strategy,

because any pro-

gram would have divided the Whigs and

made defeat

certain. Party leaders in each section

of the country

thus were left free to stress those

political considera-

tions which most appealed to the voters

of their partic-

ular section. To the Whigs of Ohio, the

election of

1840 was a referendum on

"Executive usurpation."

They condemned the frequency with which

Jackson and

Van Buren had resorted to the veto as a

usurpation of

power which belonged only to Congress.

The nomination of Harrison and Tyler

was received

with great enthusiasm in Ohio.

"Now is the winter of

34 Niles' Register, v. LXI, p. 232; Tyler, Lyon G., The Letters and

Times of the Tylers, v. I, p. 595.

35 Proceedings in Weekly Ohio State

Journal, December 14, 1839; Mc-

Master, op. cit., v. VI, pp. 556-559.

454

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

our discontent made glorious summer by

the nomina-

tion of this son of a Revolutionary

sire," the Belmont

Chronicle declared. "Now do we breathe freer and

deeper than we have for the last three

years."36 The

Cincinnati Daily Gazette saw in

Harrison's nomination

certain defeat for the "fell

disorganizing spirit" of

"locofocoism" and the

"certain restoration of sound

republican doctrines; the security of

our institutions."37

Spontaneous and enthusiastic gatherings

were held all

over the State to respond to the

nomination. At a

convention in Cincinnati on December

16, speakers

who had supported Clay pledged their

support of the

nominees.38 The earlier

despondency of the Whigs now

turned into confidence and all elements

of the opposition

found it easy to support a candidate

whose principles

no one knew. Reform of the

"aristocratic" government

of Van Buren became the catch-phrase of

the hour, and

in this program State Rights men, led

by John G.

Miller in the Ohio Confederate and

Old School Repub-

lican, as well as Jacksonians, discontented for various

reasons with the Van Buren

administration, and Nation

alist Whigs could join heartily in the

great attempt to

oust the Democrats. The Ohio

Statesman, chief Demo-

cratic organ of the State, pointed out

quite correctly,

that "The Federal party has no

policy of its own--no

principles--no cohesion--no unity of

sentiment upon

which to found a campaign, or

concentrate their forces

for action,"39 and attributed

the nomination of Harrison

36 December 17, 1839.

37 December 14, 1839.

38 Cincinnati Daily Gazette, December

16, 1839.

39 December 10, 1839.

Party Politics in Ohio,

1840-1850 455

to a combination of abolitionism,

"Bankery" and anti-

masonry.40

The Democrats, of course, could do

nothing but re-

nominate Van Buren. Their nominee had

reached the

White House because of the spell of

Jackson's popu-

larity, but he gradually had acquired

an effective fol-

lowing of his own, while his policies

were gradually

accepted by the masses of Democratic

voters in the

North. In Ohio, resolutions of county

and district con-

ventions forecast the renomination of

the Democratic

president.41 The

radical anti-bank faction of the party

was in control of the party machinery

in the State and

was completely satisfied by Van Buren's

policy toward

the banks. The recommendation of an Independent

Treasury, in the president's third

annual message, had

given Ohio Democrats their issue. Van

Buren had

attacked the suspension of specie

payments, and had

charged that it was not due to a lack

of confidence in

the banks, but that it had been brought

about merely

for the convenience of the banks. The

President pointed

to the widely expanded system of bank

credit as evidence

of the unsoundness of those

institutions, and expressed

the fear that capitalists were using

the banking system,

then in vogue, to exert powerful and

insidious influence

over the entire country. As a remedy

for these evils,

Van Buren, as is well known, urged the

creation of

public depositories for the revenues of

the nation in

order to "divorce" the funds

of the government from

the intrigues of bankers and

politicians.42

40 December 11, 1839.

41 Ohio Statesman, August,

December, 1839; January, May, 1840.

42 Richardson, James D., A

Compilation of the Messages and Papers

of the Presidents, 1789-1897, v. III, pp. 540-547.

456 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

The Whig press of Ohio greeted Van

Buren's mes-

sage as another Locofoco attack on

credit and com-

merce. The Cincinnati Daily Gazette (W)

believed that

the President intended to turn over his

party to the

radicals after he saw the burst of

enthusiasm for Har-

rison. "Perish credit, perish

commerce! Down with the

checks and balances, the restraints

imposed and the

rights secured by the

Constitution," commented the

Gazette. "The tyrant

locofocos with the Executive

their instrument, are to administer the

government

under the guidance of party impulse and

party intri-

gue."43 Wilson Shannon

(D), elected governor of Ohio

in 1838 on a policy of bank reform,

had, however, re-

ceded somewhat from his former position;

and his mes-

sage to the General Assembly, in

December, 1839, dif-

fered considerably from the views set

forth in the Presi-

dent's message. The Ohio governor

recommended a

system of independent banks under state

regulation.44

The Whig press commended Shannon's

message, the

Cincinnati Daily Gazette declaring

that there was not

one "Jacobinical feature in the

whole document."45 As

a result of Shannon's new position some

Whigs actually

planned, for a time, to support him for

re-election in

1840. But these plans were abandoned

when the Dem-

ocratic State Convention of January 8,

1840, named

Shannon as candidate for governor on a

platform of

bank reform.46

The same Convention endorsed Van Buren

for the

43 Cincinnati

Daily Gazette, January 6, 1840.

44 See chapter on "Banking and

Currency in Ohio Politics, 1840-1850."

45 December 6, 1839.

46 Ohio Statesman, January 8, 9,

10, 1840.

Party Politics in Ohio,

1840-1850 457

presidency, praising his proposal for

an Independent

Treasury. It also declared its

opposition to a high pro-

tective tariff and a system of internal

improvements.

Van Buren was represented as a follower

of Jefferson

and an advocate of a simple and

economical govern-

ment.47 There were no more

ardent supporters in the

country, of Van Buren's proposal to

separate the public

money from banking corporations, than

Moses Dawson

of the Cincinnati Advertiser; Samuel

Medary of the

Ohio Statesman; John Brough, auditor of state; or

Benjamin Tappan and William Allen, the

two senators

from Ohio. Nearly every Democratic

local convention

in Ohio adopted resolutions commending

Van Buren's

policies and approving the candidacy of

the "Little

Magician."48 Ohio senators and

representatives were

instructed by the Democratic General

Assembly to sup-

port the Independent Treasury Law.49

Its passage was

hailed by the Democrats as a second

declaration of

independence50 and the Ohio

Statesman praised it as the

only constitutional plan ever devised

to care for the

public money. The clause providing for

the payment

of government dues in specie found

especial favor with

Medary, the editor of the Statesman,

because it would

take from the monopolies of the country

much of their

"ill-gotten power of

oppression."51

The Democratic National Convention of

1840 organ-

ized with Governor William Carroll, of

Tennessee, as

47 Proceedings

of the Democratic State Convention in Ohio Statesman,

January 8, 9, 10, 1840.

48 Ohio Statesman, January 8, May 5, 1840.

49 Cincinnati

Daily Gazette, January 16, 1840.

50 McMaster, op. cit., v. VI, p.

547.

51 Ohio Statesman, June 24, July 7, 1840.

458

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

chairman. Among the prominent Ohio

delegates were

Samuel Medary, John B. Weller

(afterwards candidate

for governor and at this time a

representative in Con-

gress), James J. Faran, of Cincinnati,

S. A. Barker,

Peter Kauffman, a prominent German from

Akron, and

C. J. McNulty. In contrast to the

action of the Whig

Convention, the Democrats drew up a

platform, which,

among other things, approved a strict

construction of

the Constitution, to the extent of

condemning a "general

system of internal improvements,"

or the assumption by

the General Government of state debts

"contracted for

local internal improvements or other

State purposes

. . ." Other features included a

declaration against the

fostering of one branch of industry at

the expense of

another, a statement denying the power

of the Federal

Government to establish a national

bank, and a condem-

nation of the efforts of abolitionists

"to induce Congress

to interfere with questions of slavery,

or to take incipient

steps in relation thereto" as

"calculated to lead [to] the

most alarming and dangerous

consequences . . ."

During the latter part of the

'thirties, an increasing

number of abolition petitions asking

the Federal Gov-

ernment to abolish slavery in the

District of Columbia

led to the adoption of a rule in the

House by which such

petitions were laid on the table

without being read or

printed.52

A resolution professing sympathy for

the immi-

grants was adopted in order to catch

the foreign vote.

Van Buren was nominated for president,

but no one

52 McMaster, op. cit., v. VI, pp. 295-296. The Ohio Democracy de-

nounced abolition petitions as attempts

to disrupt the Union.

Party Politics in Ohio, 1840-1850 459

was named for the vice-presidency,

since the local con-

ventions had not indicated an

outstanding favorite.53

The Democratic national organ described

the contest of

1840 as one "between privileged

orders and the great

mass of the people." "It is,

in fact," the Globe contin-

ued, "only a new, more invidious,

and dangerous modi-

fication of the old feudal system of

the middle ages.

At that period, the great instrument of

oppression was

the sword; now it is the purse. By the

former, the

feudal baron carved out his fortunes;

by the latter, the

rag baron acquires power and influence

through means

of exclusive privileges, from which the

great mass of

the people are forever barred."54

This idea of a class

conflict was mirrored in the Democratic

press of Ohio,

which also represented the issue, as

one between the

rights of the masses, and the

privileges of the few, as

a second contest for first principles

in government, and

as an avowal that the people's money

would never again

be placed at the disposal of a few

swindling bankers.55

The Harrisburg nominations, in

December, 1839,

were followed by enthusiastic

preparations by the Whigs

throughout the State. Victory seemed

imminent since

the campaign for unity had succeeded in

drawing many

of the Jacksonians, who were

dissatisfied with Van

Buren as a party leader, into the ranks

of the Whigs.56

On February 21 and 22, 1840, one of the

most

important and enthusiastic Whig

gatherings ever held

53 Proceedings

of the Convention are taken from the Washington Daily

Globe, May 7, 1840.

54 Washington Daily Globe, May

12, 1840.

55 Ohio Statesman, March 2, 1840.

56 Ohio Whig Standard and Cincinnati Daily Gazette quoted in Ohio

State Journal (Semi-weekly), January 8, 11, 1840.

460 Ohio Arch. and Hist.

Society Publications

in the State assembled at Columbus. The

proposal for

such a mass convention had been opposed

by the staid

Cincinnati Gazette, a reform

paper which opposed horse-

racing and coffee-houses, on the

grounds that a conven-

tion was not conducive to cool

deliberation.57 But the

enthusiasm of the hour was

irresistible, and the Gazette

soon joined the chorus in praise of

Harrison. The Ohio

State Journal claimed that "Men who claimed member-

ship with all the political parties

into which the country

was divided, are around us, resolved to

merge their

differences of opinion on minor topics,

in the one all-

absorbing, paramount question of

Reform; determined

that the reins of government shall no

longer remain

within the grasp of those who are

driving to destruction

every interest and doctrine upon which

the Confederacy

was based and upheld."58 During these

convention days,

glorious for Ohio Whiggery, a

continuous stream of

cheering thousands poured into Columbus

undeterred

by muddy roads and intermittent rain.

"Banners, in-

genious in device, and splendid in

execution," an eye-

witness wrote, "loomed in the air;

flags were streaming,

and all the insignia of Freedom swept

along in glory

and in triumph--canoes planted on

wheels and manned

by the brave and generous friends of

Harrison and

Tyler--square-rigged brigs--log

cabins--even a minia-

ture of old Fort Meigs--all these and

more, made up

the grand sum of excitement and

surprise." The same

eye-witness estimated the crowd at

20,000.

By February, 1840, the Whigs were

thoroughly

intoxicated with their hard cider

campaign, and in a

57 Cincinnati

Daily Gazette, December, 1839; February, 1840.

58 Ohio State Journal (Semi-weekly), February 21, 1840.

Party Politics in Ohio, 1840-1850 461

frenzy over the rather dubious military

glamour which

had grown up around Harrison with the

passing of the

years since Tippecanoe and the War of

1812. Hard

cider and log cabins became the emblems

of the Whig

cause, following an unfortunate remark

of a corre-

spondent of a Baltimore paper to the

effect that if

Harrison were given a pension of two

thousand dollars

a year, plenty of hard cider, and a log

cabin, he would

not concern himself with the

presidency.59 Instantly,

the phrase was seized by Whig

campaigners and turned

to the advantage of the old General.

Through these

emblems of western democracy, Harrison

was identified

with the cause of the common man, and

the campaign

became a kind of frenzied crusade to

render justice to

the old Hero who had long suffered from

popular

neglect. Democratic sneers, that

Harrison was an old

granny, albeit a deserving old

gentleman, who should

remain quietly in his cabin at North

Bend, only served

to stimulate the popular imagination

and to make Har-

rison the hero of the masses. Drunk

with hard cider

and hero worship, the assembled

thousands at the

famous February Convention indulged in

all the fan-

tastic orgies of a revival.

The throng was called to order by Judge

James

Wilson, of Steubenville. Reasin Beall, of Wayne

County, a senatorial delegate to the

National Con-

vention, became permanent chairman.

Amid great en-

thusiasm, Thomas Corwin, the

"Wagon Boy," was

nominated for governor. At the time, he

was a repre-

sentative in Congress where he had

achieved something

59 McMaster,

op. cit., v. VI, p. 562.

462

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

of a national reputation by his

sparkling defense of the

military record of General Harrison.

Previously, he

had served in the General Assembly of

Ohio. The nom-

ination conformed to the specifications

laid down by the

Cincinnati Gazette previous to

the Convention; namely,

that no one should be selected who had

taken a promi-

nent part in the abolition movement.

For this reason,

Charles Anthony, President of the Colonization

Society

of Ohio, and an opponent of

abolitionism, and Judge

James Wilson, identified with the

anti-slavery interests,

had proved unavailable.60

The keynote of the resolutions of the

Convention

was opposition to "executive"

usurpation. It was de-

clared that the power of the president

to appoint

and remove officers should be

restricted within the

"narrowest limits allowed by the

Constitution." Other

resolutions favored a single term for

the president,

condemned the use of the veto

"except to preserve the

Constitution from manifest

violation," and denounced

the "spoils system" as well

as official interference in

elections and the assessment of

office-holders for elec-

tioneering purposes. It is particularly

important to

notice the Whig declaration concerning

a national bank,

because that question became the great

issue during

Tyler's administration. The Columbus

Convention re-

solved "That it is the duty of the

General and State

Governments to secure a safe and

uniform currency, as

well for the use of the people, as for

the use of the

Government, so far as the same can be

done without

transcending the constitutional limits

of their authority

60 Cincinnati Daily Gazette, February

4, 1840.

Party Politics in Ohio, 1840-1850 463

--and that all laws, calculated to

provide for the office-

holders a more safe or valuable

currency than is pro-

vided for the people, tend to invert

the natural order

of things--making the servant superior

to the master,

--and are both oppressive and

unjust." This declara-

tion was at once an effort to salve the

feelings of State

Rights Whigs, like John G. Miller, and

to satisfy the

Nationalist Whigs who wanted something

done to sta-

bilize the currency. It aimed,

moreover, to unite all

elements of the party in behalf of a

system of currency

for all classes of the people. The resolution was a

clever reference to the Democratic

scheme for an Inde-

pendent Treasury which was portrayed as

a plan to pay

the officers of the Government in gold

and silver while

the people were forced to rely upon a

depreciated paper

currency.61 The Convention concluded

its labors by

urging the organization of

"Harrison Reform Clubs"

all over the State, to be composed of

former Jackson and

Van Buren followers.62 The

Democrats described this

enthusiastic assemblage of Whigs as a

"Federal Con-

vention of Abolitionists, Bankers,

Officeholders, Mer-

chants, Lawyers and Doctors," and

a list of delegates

most of whom were bank directors, bank

stock-holders

and lawyers, was drawn up to expose the

nature of the

party.63 Whig pretensions to

love for the common peo-

ple, moreover, were derided by the

Democrats as mere

mockery.

61 Ohio Statesman, January

8, 9, 1840.

62 Proceedings

of the Convention are taken from the Ohio State Journal

(Semi-weekly), February 26, 1840. The

State Central Committee for the

ensuing year was to be composed of

Alfred Kelley, Joseph Ridgway, John

W. Andrews, Robert Neil, John L. Miner,

Francis Stewart, Lewis Heyl, Dr.

John G. Miller and Lyne Starling, Jr.

63 Ohio Statesman, February 22, 1840.

464 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

Both parties, in 1840, threw the issues

and principles

to the winds. The lack of a Whig

platform and the am-

biguous character of their candidate

made such cam-

paign strategy easy. The Democrats

challenged both

Harrison's bravery and his genius as a

commander. "If

a great General," wrote the Globe,

"such was the equiv-

ocal character of his exploits that,

whenever a victory

had been gained, it was difficult to tell

whether it was

owing to his fortunate blunders, or won

by others, in

spite of his imbecility."64

As the Democratic Globe

pointed out, Harrison was, without

doubt, "preferred to

his distinguished competitors, on the

score of that ex-

emplary mediocrity for which he is so

singularly illus-

trious." Corwin set out to rebut

these reflections on

Harrison's military successes, in the

halls of Congress,65

and so withering was his reply to

General Isaac Crary,

of Michigan, who had attacked

Harrison's record, that

the venerable John Quincy Adams's

reference to the

"late General Crary" on the

following day convulsed the

House with laughter.66

Giant rallies and conventions, at which

the Whig

emblems of the log cabin and hard cider

were much in

64 Washington Daily Globe, March

16, 1840.

65 Cincinnati Daily Gazette, March

26, 1840; Eaton Register, April 9,

1840.

66 Greeley, op. cit., p. 132; In

the course of his defense of Harrison,

Corwin ridiculed the military qualifications

of Crary declaring that "we all,

in fancy, now see the gentleman from

Michigan in that most dangerous and

glorious event in the life of a militia

general on the peace establishment--

a parade day! The day for which all

other days of his life seem to have

been made. We can see the troops in

motion; umbrellas, hoe- and ax-

handles and other like deadly implements

of war overshadowing all the

field, when lo! the leader of the host

approaches . . . his plume, white, after

the fashion of the great Bourbon, is of

ample length, and reads its doleful

history in the bereaved necks and bosoms

of forty neighboring hen-roosts!"

Josiah Morrow, Life and Speeches of

Thomas Corwin, p. 250.

Party Politics in Ohio,

1840-1850 465

evidence, marked the campaign. One of

the most

notable was at Fort Meigs, a spot

almost sacred to the

Whigs because of the exploits of

Harrison in that vi-

cinity. The old General himself

promised to attend and

for days excited crowds from all over

the State streamed

to that point. Alfred Kelley, one of

the most prominent

Whigs in Ohio, who accompanied Harrison

to the scene

of his earlier triumphs, described the

journey as a "tri-

umphal procession" made so by large

assemblages who

gathered at all the stopping places,

and mingled their

shouts with the booming salutes fired

in honor of "Old

Tip."67 At Fort Meigs,

40,000 milled around endlessly

to get a close view of their Hero.

There was a sham

attack on the old fort by a band of

Indians, a speech by

Thomas Ewing, as chairman of the

Convention, and

some remarks by the old General

himself. An eye-wit-

ness described the appearance of the

mob after Harri-

son came out to speak, as follows:

"What now shall we

say of that multitude? Could the

presence of Van Buren

inspire such a feeling as at that

moment animated every

bosom? Here was no selfish feeling--the

merchant--

the farmer--the mechanic--the rich and

the poor--all

were here united in one thought. They

were here in

their might--and in the venerable form

before them,

they recognized a connecting link in

that great chain of

patriotism, which had bound a Republic

together, from

its birth to the present day. A

chieftain was there who

led their armies on from victory to

victory--one who

had been clothed with trust without

abusing it--whose

fame was written in the crumbling

breastworks, bastions,

batteries and traverses, which

everywhere surrounded

67 Alfred Kelley to Follett, June 14, 1840,

quoted in "Selections from

the Follett Papers, IV," 1916; loc. cit., v. XI, No. 1, p. 21.

Vol. XXXVII--30.

466

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

them. . . And well did they appreciate

his services

--for sure never before, was enthusiasm

greater--never

before was a loftier shout borne upon

the breezes of

heaven."68 The state was

filled with stories of General

Harrison's devotion to the welfare of

the poor.

Conventions of a similar nature were

held at Cin-

cinnati, Columbus, Cleveland, Dayton

and at many other

points. At Cincinnati, the attendance

was estimated at

25,000. Numerous banners proclaimed the

issues of

the campaign and bore inscriptions like

"Farmers, Me-

chanics, Manufacturers, Merchants,

Laborers, against

Locofocism," "Van Caught in a

Whig Trap," (showing

Van Buren caught in a log cabin baited

with hard cider),

"For Jackson we did but for Van we

can't," and "No

Standing Army; Resistance to Tyrants is

Obedience to

God."69 The last evidently referred to the proposal of

the Secretary of War, Joel R. Poinsett,

for a standing

army of two hundred thousand men to be

distributed

over the United States in eight

military districts.70 In

point of numbers, however, the greatest

rally of the

whole campaign was held at Dayton, on

September 1.

The estimate of 100,000 people was

undoubtedly an

over-statement. Thousands gathered

around the Gen-

eral's stand to hear him deny the many

charges which

the Democrats had made against him.

Harrison de-

clared that he was opposed to the use

of the veto except

in extreme cases and that he favored a

single term for

the president. He firmly denied that he

had ever been

68 Perrysburg Whig quoted

in Ohio State Journal (Weekly), June 24,

1840; an account is also given in

Randall and Ryan, History of Ohio,

v. IV, pp. 37-39.

69 Cincinnati

Daily Gazette, October 3, 1840.

70 Cincinnati Daily Gazette, July

22, 1840.

Party Politics in Ohio,

1840-1850 467

a Federalist, but would not commit

himself on the ques-

tion of a national bank. Apparently,

there was no spe-

cific power in the Constitution to

create a bank. Harri-

son asserted that he thought that he

would favor a bank

if the powers granted to Congress could

not be carried

into effect without such an

institution, and if the wishes

of the people were made manifest in

favor of a bank.

The remainder of his speech consisted

of typically dem-

agogic appeals to the provincialism of

the frontiers-

man.71 The Ohio delegation to the Whig

convention of

young men in Baltimore carried the

banner of the State

with the inscription "She offers

her Cincinnatus to re-

deem the Republic."72

Another characteristic feature of the

campaign of

1840 was the effective use that was

made of the "Buck-

eye Blacksmith," a man who, by his

character and meth-

ods, typified the Whig appeal to the

country in 1840.

The "Buckeye Blacksmith,"

John W. Bear of Zanes-

ville, first attracted public attention

by his oratorical

efforts at the Whig State Convention of

February 21-22,

1840. Without the least pretense to an

education, this

natural-born orator appealed to the prejudices

of the

71 Harrison's speech and the account of

the meeting is given in Ohio

State Journal (Weekly), September 23, 1840; account of meeting given

in Cincinnati Daily Gazette, September

12, 1840, and in Randall and Ryan,

op. cit., v. IV, pp. 39-40.

72 The Cincinnati Daily Gazette appealed

to the Whigs of the State,

and particularly of Cincinnati to send a

large delegation to a meeting held

in Nashville, August 17, because of the

close commercial relations existing

between Cincinnati and the South and

West. Bellamy Storer and S. S.

L'Hommedieu of Cincinnati took prominent

parts in the Nashville meeting,

and Senator Hugh L. White of Tennessee

was lauded for his refusal to

follow the Van Buren administration and

for his resignation from the senate

when instructed by the Tennessee

Legislature to support the Independent

Treasury scheme. Daily Gazette, August

8, 1840.

468

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

poor against the rich, and soon won the

name of "rab-

ble-rouser." His mere support of

the Whigs was an

effective argument against the

Democratic claim that

their party represented the "bone

and sinew" of the

land. Bear's fame spread throughout the

State and mul-

titudes flocked to hear him. From Ohio

he was taken to

other states where he continued his

phenomenal suc-

cesses. For his services he later was

appointed by Pres-

iden Harrison to the Wyandot Indian

Agency, only to

be removed by Tyler.73

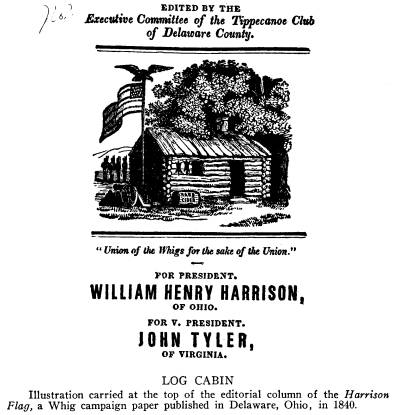

As an aid in the contest to end

"executive usurpa-

tion" the Whigs started many

campaign papers. One

of these, the Harrison Flag, announced

itself as a volun-

teer in the cause of the people in

order to furnish an

"anti-dote" for the

"poisons" spread abroad by Demo-

cratic papers like the Globes and

Statesmans.74 The

Daily Political Tornado declared that its chief purpose

was to expose the greatest liar of the

age, Samuel Med-

ary, editor of the Ohio Statesman.75

Other new Harrison

papers were the Investigator and

Expositor of Troy, the

Calumet and the War-Club of Springfield, the Harrison

Democrat of Hamilton, the Log Cabin Herald of Chilli-

cothe, the Straight-Out Harrisonian of

Columbus, and

the Axe of Cleveland.76 These

new papers, adept as

they were in broadcasting the homely

virtues of their

own candidates and in repeating the

stories of the aristo-

cratic tendencies of Van Buren,

exercised a tremendous

influence over the voters of Ohio.

Their appeals were

the essence of the log cabin arguments.

73 Randall and Ryan, op. cit., v.

IV, pp. 34-37.

74 The Harrison Flag, (Delaware,

Ohio), April 28, 1840.

75 Daily Political Tornado, October 6, 1840.

76 Cincinnati Daily Gazette, May

14, 1840.

Party Politics in Ohio, 1840-1850 469

In Ohio, the Independent Treasury

constituted a con-

venient point of attack for the Whigs

and upon this

measure they poured all the venom of

their denuncia-

tions. It became a definite issue in

Ohio politics when

the General Assembly (D), in January,

1840, adopted

resolutions instructing the Ohio

senators and requesting

the Ohio representatives to vote for

the Independent

Treasury.77 The Ohio Whigs considered it

as little

short of "national suicide to add

the weight of the public

treasury to a power so fearfully vast,

and consign the

entire charge of the National purse to

a band of trained

partisans, who have never been

remarkable for honesty.

. . ."78 They declared that the

Independent Treas-

ury Bill contained no provision for the

benefit of the

people, nothing to restore healthy

exchanges, nothing to

place the people's and the Government's

money on a par,

and nothing to correct a disordered

currency or encour-

age the laboring class. "The money

goes from its iron

cages to pay office-holders and great

contractors, who

are enriching themselves from the

national funds."79

The Eaton Register described the

passage of the Inde-

pendent Treasury as the triumph of

"Vandals" and the

"minions of a contemptuous

Executive."80 The Whigs

argued, furthermore, that the measure

would reduce the

price of labor and lands, and enhance

the value of slave

labor, and predicted the direst

consequences.81 The

77 Cincinnati Daily Gazette, January

16, 1840.

78 Ohio State Journal (Weekly), August 21, 1839.

79 Ibid., September 10, 1839.

80 Eaton Register, July 16, 1840.

81 An editorial in the Albany Daily

Advertiser described the Independ-

ent Treasury as "a moneyed

despotism in its most odious form--the despot-

ism of a central consolidated

government, strengthened by a monster bank,

owned and controlled by the

officeholders . . ." quoted in Eaton Register,

January 16, 1840.

470 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

measure was designed, according to the

Ohio Whigs, to

depress the commercial, industrial, and

agricultural in-

terests of the North in favor of the

"grasping avarice

of the pampered South."82 Most

of all, it involved a

union of the purse and the sword and

endangered the

liberties of the people. In developing

this last point, the

Whigs made a great deal of the

proposals of Van

Buren's Secretary of War, Joel R.

Poinsett, to increase

the size of the army. "The whole

shows plainly, to our

mind," declared the Cincinnati Daily

Gazette, "that the

great thing which Martin Van Buren's

administration

contemplates, and which it is

endeavoring by all means

to bring about, is a full and effective

union of the purse

and sword;"83 and the

Eaton Register saw in this scheme

real danger to the liberties of

citizens and a violation of

the Constitution.84 Samuel Medary

recognized that

Democratic strength was crumbling under

these attacks,

and complained to Van Buren that it was

remarkable

what a "humbug" had been made

out of Poinsett's pro-

posal. "The standing army of

200,000 men is wrung

on every change," he wrote,

"and every attempt to ex-

plain only seemed to give force to

their declarations."85

One of the most damaging charges of the

Democrats

against Harrison was that his ignorance

of public af-

fairs made it necessary that he be

guarded by a com-

mittee from making indiscreet

utterances during the

82 Eaton Register, April 23,

1840.

83 Cincinnati Daily Gazette, April

29, 1840.

84 Eaton Register, April 30,

1840.

85 Medary to Van Buren, August 18, 1840,

Van Buren MSS., v. XL.

The Columbiana County Democrats defended

the Poinsett plan on the

grounds that it was the true English

policy of resistance to tyranny, and

pointed out that in 1817, while a member

of the House, Harrison had urged

a system of general military

instruction. Ohio Statesman, April 17, 1840.

Party Politics in Ohio,

1840-1850 471

campaign. A letter of inquiry from

Niles Hotchkiss of

the Union Association of Oswego, New

York, addressed

to Harrison, seemed to give some

support to this charge.

The reply to Hotchkiss's letter came

from David

Gwynne, John C. Wright, and 0. M.

Spencer of Cincin-

nati, who described themselves as

Harrison's "confiden-

tial committee." This triumvirate,

referred to by the

Democrats as the keepers of the

General's conscience or

the muzzling committee, announced that

it was the pol-

icy of the General to make no more

public declarations

of principles because his views on

present policies might

be judged by his past actions and

utterances.86 The

Globe described the committee as the "mysterious con-

clave that presides over his conscience

and opinions" and

declared that Harrison's public

utterances convicted him

of "Abolitionism, Bankism,

Latitudinarianism,"87 and

the Ohio Statesman ridiculed

Harrison and his commit-

tee of politicians.88 Whig orators

and Harrison him-

self denied these charges vigorously,

declaring that

there was no attempt to conceal the

candidate's views,

but that so many letters of inquiry had

arrived that it

was necessary to establish a committee

to answer them.89

In an effort to counteract the growing

wave of de-

mocracy behind Harrison's candidacy,

the Democrats

dug up a charge that he had voted in

favor of selling

86 Letters

from Hotchkiss to Harrison and from the committee to

Hotchkiss are taken from Washington Daily

Globe, March 25, 1840. The

Globe reprinted them from the Oswego Palladium. Wright

became editor

of the Cincinnati Gazette upon

the death of Hammond in 1840. In 1840,

he ran for the Ohio Senate but was

defeated by Holmes (D) after a

contest which stretched out over a large

part of the legislative session of

1840-1841.

87 Washington Daily Globe, March

25, 1840.

88 Ohio Statesman, June 9, 1840.

89 Cincinnati

Daily Gazette, April 6, June 30, 1840.

472 Ohio Arch. and Hist.

Society Publications

poor white men into slavery.90 So

damaging was this

accusation that the Whigs found it

advisable to conduct

a minute investigation into the records

of the General

Assembly of Ohio. This brought to light

that Harrison,

in 1820-1821, had voted against an

amendment to abol-

ish that feature of a law authorizing

the sheriff to

sell offenders to those persons who

would pay the fine

and costs of his prisoners. The Whigs defended

Har-

rison's position by pointing out that

the prisoner, dur-

ing his period of service, was

protected from abuse in

the same manner as apprentices; that if

the offender

were willing, he could work out his

fine on the public

highways; that if he were unable to pay

the fine and

physically unable to work he might be

discharged from

prison; and that only convicted

offenders of the penal

laws of the State could be sold into

service.91 Repre-

sentative Mason of Ohio undertook to

defend Harrison

from this charge in Congress.92

In spite of the efforts of the leaders

of both parties

to keep it out, the anti-slavery

question was injected into

the campaign of 1840. Chiefly as the

result of a strug-

gle in Congress over the right of

petition in which Cal-

houn and Adams represented the extreme

viewpoints of

the South and the North on the slavery

question, the

one favoring the right, the other

opposing it, the right

of petition had become a burning issue

all over the coun-

try after 1837. In reality, the

Congressional contest

was a struggle for the constitutional

right of petition

which was assailed by the friends of

slavery because it

endangered the security of slave

property and even the

90 Ohio Statesman, April 7, 1840.

91 Ohio State Journal (Weekly), April 22, 1840.

92 Cincinnati Daily Gazette, April

30, 1840.

Party Politics in Ohio,

1840-1850 473

existence of the Union. Calhoun had

stated his position

in the form of six resolutions designed

to protect slavery

against further attack from

abolitionist petitions. He

was answered by Thomas Morris of Ohio

in a set of

resolutions asserting that slavery was

sinful and im-

moral, and that Congress had a

constitutional right to

abolish slavery in the District of

Columbia and in the

Territories.93 The result of this debate was the passage,

by the House of Representatives, of the

Patton "gag"

resolutions by which that body refused

to print or read

abolition petitions.94 The immediate

effect of this ef-

fort at repression was an increase in

the number of such

petitions. Protests against the gag

resolution as a vio-

lation of the Constitution poured into

Congress, Ohio

alone sending thirty,95 but the House

adhered to its res-

olution.96 Anti-slavery sentiment increased as a conse-

quence throughout the free states. The

issue now in-

volved a struggle for the right of

petition. Many who

scorned connections with the

abolitionists, were alarmed

by the constitutional issues raised by

the struggle in

Congress.

The Ohio Whigs insisted that the gag

resolutions

were violations of the sacred right of

petition, and

pointed out that the six Ohio votes

cast in its favor were

the votes of Democrats.97 The Ohio

Statesman, how-

ever, declared that the controversy

over the reception

of abolition petitions was merely a

"humbug branch of

93 McMaster, op. cit., v. VI, pp.

482-484.

94 Ibid., op. cit., v. VI, p. 489.

95 Ibid., v. VI, p. 490.

96 Ibid., v. VI, pp. 510-511.

97 Cincinnati Daily Gazette, February

13, 1840. The Ohio Democrats

who voted for the gag resolution were

John B. Weller, Isaac Parrish,

D. P. Leadbetter, William Medill,

Jonathan Taylor, and George Sweeney.

474

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

Harrison Whiggery," and maintained

that by "putting

this federal firebrand to rest Congress

[had] saved the

nation a million a year."98 All the

rioting over the slav-

ery issue during the past few years,

was attributed by

the St. Clairsville Gazette (D),

to abolitionists whose

"spurious" martyrdom failed

to aid the slave and only

served to alienate one portion of the

country from

another.99 Clay's opposition to the

abolitionist petitions

was strongly condemned by the

Cincinnati Daily Ga-

zette, a Clay paper. On the 25th of May, 1839, Clay

wrote a letter to a Whig county

committee in Kentucky

justifying his position. He argued that

"In the Consti-

tution of the Union there is not a

solitary provision,

fairly interpreted and fairly

administered, which au-

thorizes any interference of Congress

with Domestic

Slavery, as it exists in the United

States." To this as-

sertion the Gazette took

exception, and pointed to in-

stances where the Government had aided

in the return

of slaves.100 Partly

in consequence of this issue, the

abolition press hailed the selection of

Harrison over Clay

as a victory for their cause. This was

especially true of

the Emancipator, the Liberator

and the Philanthropist,

which chose to interpret the nomination

of Harrison as

a concession to the anti-slavery

sentiment of the coun-

try; and the Oberlin Evangelist argued

that no slave-

holder could ever again be president of

the United

States.101 The Democratic Ohio

Statesman, anxious to

fasten the taint of abolitionism on the

Whigs, told its

readers that Harrison, if elected,

would use the surplus

98 Ohio Statesman, February

3, 1840.

99 St. Clairsville Gazette quoted

in Ohio Statesman, February 6, 1840.

100 Cincinnati Daily Gazette, August

26, 1839.

101 McMaster, op. cit., v. VI, pp. 560-561.

Party Politics in Ohio,

1840-1850 475

revenue of the Government to buy

negroes "to be set

free to overrun our country,"102 and the

Democrats ap-

pealed to the economic interests of

northern white la-

bourers by the argument that the

abolitionists would fill

the towns and villages of the North

with blacks, thus

"degrading labor where they could

get it, and stealing

and robbing where they could not."103

The position of the anti-slavery men in

Ohio was not

as yet sharply defined. To 1839, they

had generally

repudiated separate political action

and had resorted

to questioning the candidates of both

parties on the

slavery issue in order to throw their

votes to those who

gave the most favorable replies. In this

manner, for

example, they had aided in the election

of Joshua R.

Giddings to Congress in 1838. But this

method proved

disappointing in 1839 when several men

supported by

the Anti-Slavery Society voted for a

Fugitive Slave

Law at the request of Kentucky

slaveholders. As a

result, the anti-slavery men in the

Western Reserve

forced the Whigs to repudiate some of

the men who had

voted for the Fugitive Slave Law, and

to accept other

candidates, notably Benjamin F. Wade.

But Wade was

defeated because of Whig antipathy to

his strong anti-

slavery position.104 Although

the American Anti-

Slavery Society in July, 1839, resolved

to support no

one who was not an abolitionist, the

Ohio branch, meet-

ing at Massillon, June 10, 1840,

decided that it was

102

Ohio Statesman quoted in Washington Daily Globe, January 13,

1840.

103 Ohio Statesman, January

17, 1840.

104 T. C. Smith, Liberty and Free

Soil Parties in the Northwest (Har-

vard Historical Studies, v. VI, pp.

30-32.) I have relied upon this study

to a large extent for the history of the

Liberty party but I have supple-