Ohio History Journal

WILLIAM GIFFIN

Black Insurgency in the Republican

Party of Ohio, 1920-1932

An extraordinary change in Negro voting

patterns has occurred between the post-

Civil War period and the present. The

black vote was remarkably consistent for the

party of Lincoln from the passage of the

Fifteenth Amendment to the New Deal

period, but this solidly Republican bloc

vote was broken during the 1930's. The

black vote became more and more

overwhelmingly Democratic following the New

Deal. A misleading implication of these

facts is that the disaffection of the black

Republicans, which was clearly

manifested in the 1936 election, lacked significant

antecedents in the pre-New Deal period.

A substantial number of historians and

other professionals have implied that

the alienation of Negroes from the Republican

party occurred suddenly after 1932. They

have generally emphasized the high per-

centage of black votes polled by Herbert

Hoover in 1932 and the mass exit of Negro

voters from the Republican party in

1936. Furthermore, their explanations of the

phenomenon have largely involved changes

effected during the New Deal period.

Theodore H. White, for example, wrote:

Time was, forty years ago, when Negroes

voted solidly Republican out of gratitude to

Abraham Lincoln and emancipation.

("I remember," once said Roy Wilkins, Executive

Secretary of the National Association

for the Advancement of Colored People, "when I

was young in Kansas City, the kids threw

rocks at Negroes on our street who dared to

vote Democratic.") But Franklin D.

Roosevelt changed that. Under Roosevelt, govern-

ment came to mean social security,

relief, strong unions, unemployment compensation.

... And, like a heaving-off of ancient

habit, as the Negro moved north he moved to the

Democratic voting rolls.1

1. Theodore H. White, The Making of

the President 1960 (New York, 1961), 232. Others

who have implied, by focusing upon the

black voting record in the context of the New Deal

period, that black Republicans suddenly

became disaffected are John A. Garraty, The American

Nation, A History of the United

States (New York, 1966), 741; T. Harry

Williams, Richard N.

Current, and Frank Freidel, A History

of the United States Since 1865 (New York, 1969), 538;

Richard B. Morris and William Greenleaf,

U.S.A., The History of a Nation (Chicago, 1969),

II, 842; August Meier and Elliott

Rudwick, From Plantation to Ghetto, An Interpretive History

of American Negroes (New York, 1969), 212; Samuel Lubell, White and

Black: Test of a

Nation (New York, 1964), 52-61; Harold F. Gosnell, Negro

Politicians, The Rise of Negro

Politics in Chicago (Chicago, 1966), viii; David Burner, The Politics of

Provincialism, The

Democratic Party in Transition,

1918-1932 (New York, 1968), 237; Henry

Lee Moon, Balance

of Power: The Negro Vote (Garden City, New York, 1948), 17-19; John M. Allswang, A House

for all Peoples, Ethnic Politics in

Chicago, 1890-1936 (Lexington, 1971),

205-206; Louis M.

Killian, The Impossible Revolution?

Black Power and the American Dream (New York, 1969),

37.

Mr. Giffin is Assistant Professor of

History, Indiana State University, Terre Haute.

26 OHIO

HISTORY

Similarly, in relation to the political

realignment of Negroes during the period 1932-

1940, Rita W. Gordon wrote: "This

transfer of Negro voters represents as dramatic

and sudden a change in political

behavior as has ever occurred in American politics

and poses a question about the role that

the New Deal played in causing the shift."2

A study of the record shows that in Ohio

alienation of black Republicans did not

occur abruptly during the 1930's. The

political experience of blacks in this northern

state indicates that the period between

World War I and the New Deal deserves

greater consideration to gain an

understanding of the readiness of blacks in this

state, as well as in much of the North,

to leave the Republican party during the

1930's. Negroes had participated in

World War I to make the world safe for democ-

racy. After the war they insisted that

the promises of democracy in America be

fulfilled in recognition of their

contributions in the war. This attitude was apparent

during the 1920 primary election

campaign in Ohio. Dissatisfied blacks criticized

United States Senator Warren G. Harding,

who was attempting to gain control of the

Ohio delegation to the national

Republican nominating convention. He was accused

of appealing to the white supremacist

faction of the Republican party in Texas and

Oklahoma, and was criticized for not

including a Negro on his slate of convention

delegates. In defending himself, Harding

stated:

I don't believe in preaching democracy

to somebody 5,000 miles away until our own house

has been put in order. What's the use of

fighting for democracy abroad before we have

given democracy to everyone in America?

. . .

I want the colored boys who went to the

front bravely, to have everything that is coming

to them. Don't believe that statement

that I spoke in Texas recently under the auspices of

the lily-whites. I absolutely refused to

enter the state, until the invitation was endorsed,

by both the "lily-white" and

"black and tan" organizations.3

A concession to the demand for the

inclusion of a Negro on Harding's slate of con-

vention delegates was made by including

a black alternate delegate-at-large.4 Through

these and other efforts to gain their

support, Harding won the endorsement of the

key black Republican leaders in the

primary election and in the general election of

1920, even though Cleveland Negroes

remained at home in protest to racial dis-

crimination on Colored Voters Day held

at Harding's Marion home on September

10, 1920.5

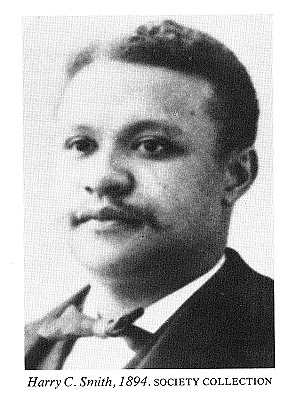

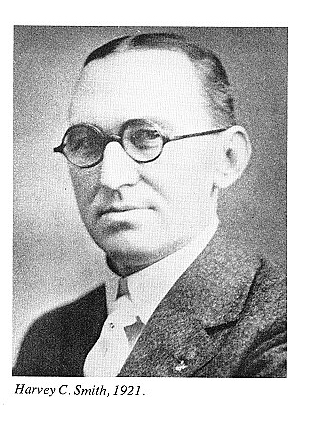

In the political context, some of the

fruits of democracy demanded by black

Republicans in Ohio were party patronage

plums. Thus, incumbent Republican

Secretary of State Harvey C. Smith was

also a target of black Republican opposition

in the primary election of 1920. The

basis of opposition to the secretary of state was

that he had been unfair to black

politicians in distributing the patronage of his office.

The method of opposition to him set a

precedent for independent political activity

later in the decade. Specifically, the

critics of the incumbent supported the candidacy

2. Rita W. Gordon, "The Change in

the Political Alignment of Chicago's Negroes During

the New Deal," Journal of

American History, LVI (December 1969), 584.

3. Gazette (Cleveland), March 20, April 24, 1920; Randolph C.

Downes, "Negro Rights and

White Backlash in the Campaign of

1920," Ohio History, LXXV (Spring-Summer 1966), 86-90,

95-96.

4. Randolph C. Downes, The Rise of

Warren Gamaliel Harding, 1865-1920 (Columbus,

1970) 386-387; Gazette (Cleveland),

March 20, 1920.

5. Ibid., June 19, September 25, 1920; a description of the

Harding strategy of keeping the

Ohio black vote and stilling the critics

is covered in Downes, The Rise of Warren Gamaliel

Harding, 535-561.

Black Insurgency 27

of a black candidate for the Republican

nomination for secretary of state.

Editor Harry C. Smith of the Cleveland Gazette

was the central figure in the black

insurgency movement against the

incumbent Harvey C. Smith. The editor was a well

known black leader who had been a

consistent and outspoken critic of those who

attempted to infringe on the rights of

his people since he had begun editing the

Gazette in 1883. He had sponsored state civil rights and

anti-lynching laws as a

Republican member of the lower house of

the Ohio General Assembly, in which he

had served three terms (1894-1895,

1896-1897, 1900-1901). He had also partici-

pated in the Niagara Movement--the black

protest effort initiated by W. E. B.

DuBois in 1905--and in the founding of

the National Association for the Advance-

ment of Colored People in 1910. In

deciding to file for the Republican nomination

for secretary of state, Editor Smith did

not consult with the leaders of the various

factions of the Republican party in

Ohio, but only conferred with politically active

Negro citizens of Cleveland and

Columbus. Of those with whom he conferred Editor

Smith wrote:

All feel that the present Secretary of

State Harvey C. Smith's persistent refusal, for nearly

two years, to give my people the

clerical representation in that office they have held under

every other Republican Secretary of

State for many years, except Charles Q. Hildebrant,

makes it absolutely necessary that some

one of my people should enter the contest.

Acquiescing to their view of the matter,

I decided to enter and have done so!6

In reference to the neglect of Negro

Republicans by some of the party's other state

office holders in making appointments,

Editor Smith declared:

Intelligent colored voters of Ohio have

reached the limit of their endurance in this matter,

and in the primary contest propose to

serve notice in a practical way on Secretary of State

Smith and all other neglectful

office-holders and members of the party that there must

come an immediate change for the better

or intelligent colored voters will carry the fight

into the elections.7

The daily presses of the state and

evidently most Ohio Republicans, black as well

as white, failed to recognize the

candidacy of Editor Smith as an independent expres-

sion of black protest on the patronage

issue. Instead, he was believed to be a tool

of a party faction that was opposing the

renomination of the incumbent secretary

of state. A challenge of the editor's

motives was brought into the open by action of

Thomas A. Goode, a black Republican from

Columbus, who was apparently a sup-

porter of the incumbent. Goode filed

with the secretary of state an affidavit charging

that Editor Smith's candidacy "was

not made in good faith" and that it was the con-

sequence of "a collusion and

conspiracy" to confuse voters by entering a candidate

with a name similar to Harvey C. Smith

and thus defeat him. Editor Smith denied

the accusation, held that his candidacy

was purely a " 'race' effort" and asked Goode

to withdraw the affidavit, which he

refused to do. The secretary subsequently held

a hearing on the issue during which the

charge of "bad faith" was repeated by Goode

and denied by the editor and his legal

counsel. The secretary ruled that the name

Harry C. Smith could not appear upon the

primary ballot. Leroy H. Godman and

Henry L. Thomas, Negro attorneys from

Columbus and Cleveland respectively,

6. Gazette (Cleveland), June 19, 1920.

7. Ibid.

|

carried the issue to the Ohio Supreme Court on behalf of Editor Smith. They won their case and the supreme court ordered the secretary of state to place Harry C. Smith's name on the primary ballot.8 Before and after the Ohio Supreme Court ruling, local newspapers implied or stated outright that Editor Smith was a dupe in a ruse to defeat Secretary of State Smith. The Cleveland Plain Dealer proposed this view in an editorial entitled "Smith, Smith, and Smith." A Columbus daily described Editor Smith's candidacy as a "trick." The Negro editor, nevertheless, traveled the state seeking the Republican nomination. His campaign itinerary included speeches in Lorain, Cleveland, Cin- cinnati, Springfield, Dayton, Columbus, Xenia, Toledo, and Oberlin. During the pri- mary campaign Editor Smith received moral and some financial support from the Negro electorate of Ohio. In the primary election itself Harvey C. Smith won renom- ination by a substantial margin. Yet Editor Smith claimed a moral victory in the fact that he received 61,081 votes, indicating that the black independent vote was a political force which should be recognized.9 The political effects of demographic change which would influence black political activity throughout the decade were felt in the insuing general election. During World War I Ohio, as other northern states, had received its first large scale migration of Negroes from the rural south. The overall percentage of blacks in the population of the state rose from only 2.3 percent in 1910 to 3.2 percent in 1920, but some urban

8. Ibid., July 3, 10, 24, 1920; ibid., letter to Thomas A. Goode, June 26, 1920. 9. Cleveland Plain Dealer, June 25, 1920. The third "Smith" was Harold C. Smith of Elyria who had also filed for the office. Columbus Dispatch, August 15, 1920 in August 28, 1920, Gazette (Cleveland); ibid., July 10, August 7, 14, 28, 1920, August 19, 1922. |

|

|

|

|

|

Negro populations had increased remarkably during the period, for example, by 307.8 percent in Cleveland and by 53.2 percent in Cincinnati.10 The Democratic party of Ohio exploited the resulting racial anxieties of whites. During the 1920 campaign the Ohio Democratic state committee issued circulars entitled "A Timely Warning to White Men and Women of Ohio" and "White Folks Don't Forget Your Negro Brothers and Sisters." The circulars, among other things, expressed anxiety about the growing migration of southern Negroes into Ohio, warned that Negroes were seeking social equality, and implied that a vote for the Republican ticket was a vote for "negro domination."11 The "A Timely Warning" circular concluded:

An ominous cloud has risen on the political horizon which should have the attention and consideration of all men and women before casting their ballots. That cloud is the threat of negro domination in Ohio. We see negro newspapers in the State boasting loudly of the increased balance of power held by their race through the enfranchisement of their women. We find them openly predicting that full social equality will be insured them by the election of the Republican candidates. It is a well-known fact that the influx of negroes from the South into the industrial centres of Ohio during the past years has been of such proportions as to give rise to a real race problem. Herded together like cattle and brought here by selfish employers to work

10. Eighteenth Census of the United States, 1960: Characteristics of the Population, Ohio, I, Part 37, p. 54; United States Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, Negroes in the United States, 1920-1932 (Washington, D. C., 1935), 55, Table 10. 11. Gazette (Cleveland), October 23, 1920; Cleveland Branch Bulletin, National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) (November 1920), 1, No. 9, Records of the NAACP, Branch Files, Ohio, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress. |

30 OHIO

HISTORY

in our industrial establishments, their

presence has brought about serious consequences

in many of our cities.

White workingmen in many communities

owning or paying for homes in factory dis-

tricts can testify to the effect which

the importation of these negroes into the community

has had upon the value of their

properties. In many of our cities it is well known that the

best residential districts have not been

free from invasion of negroes. It naturally follows

that the efforts upon the part of the

Republican candidates and leaders to further intensify

negro ambitions can only result in

greatly magnifying the evils we are already facing.

Ohioans should remember that the time

has come when we must handle this problem

in somewhat the same way as the South is

handling it, and in such a way bring greater

contentment to both whites and negroes.

We should remember what history tells us of

the dark days when negroes controlled

the Governments in the South, the enormous

expenditures and debts incurred, the

indignities heaped upon the white women and chil-

dren, the vicious attempts of the South

Carolina negro Legislature to give every negro

forty acres of land and a mule.

Men and women of Ohio, rally to the

ballot box and give such a verdict as will forever

rid Ohio of this menace to yourselves

and your children.12

The Democratic racial propaganda did not

adversely affect white Republican can-

didates; yet it did damage black

Republican candidates. The Republican party won

a landslide victory across the board in

the general election of 1920, resulting from a

number of factors which did not include

the race issue. On the other hand, it was a

bleak election for black Republicans.

Henry M. Higgins, who was a black candidate

for a seat in the State House of

Representatives, was the only Republican General

Assembly candidate from Hamilton County

(Cincinnati) defeated in the general

election.13 Similarly, black

state representative candidates B. F. Hughes and G. L.

Davis of Columbus were the only members

of the Franklin County Republican

ticket defeated in the general election

of 1920. This election proved to be indicative

of Republican reluctance to support

black candidates through most of the decade.

R. S. Huston, who was defeated in the

election of 1922, was the last black candidate

on the Republican legislative ticket in

Franklin County during the decade.14 Only

Cuyahoga County (Cleveland) elected

black Republicans to the General Assembly

during the 1920's. As a result only one

black Republican served in the legislature

during any one session throughout the

decade.15 This was a clear discontinuity with

the past when black Republicans had

greater success in being elected to the General

Assembly, although there had been fewer

black voters than during the 1920's. Black

Republicans had served in almost every

session of the legislature between 1880 and

1920; they had been elected by several

counties (including Franklin and Hamilton

as well as Cuyahoga); and as many as

three black Republicans had served during

one legislative session.16

Black Republicans quickly noted and

protested the fact that white Republicans

were dissociating themselves from black

candidates. For example, local black

12. New York Times, October 22,

1920.

13. Gazette (Cleveland), November

20, 1920.

14. Richard Clyde Minor, "The Negro

in Columbus, Ohio" (unpublished Ph.D. dissertation,

The Ohio State University, 1936), 180.

15. Harry E. Davis served from 1921-1928

and Perry B. Jackson from 1929-1930. See Ohio,

House Journal for the 1920's and Ohio House of Representatives

Membership Directory, 1803-

1965-66 (Columbus, 1966), 97.

16. List of Negro legislators who served

in the Ohio General Assembly, compiled by Edwin

Brooks, Cleveland Call & Post, February

13, 1960.

Black Insurgency

31

Republican leaders complained

vociferously in 1922 when the Hamilton County

Republican organization failed for the

first time in over two score years to support

a Negro candidate for county office. The

Reverend J. Franklin Walker, speaking

before a meeting of black voters at the

Metropolitan Baptist Church, said:

For 45 years the colored people of

Hamilton County have been accorded a place on the

[county Republican] ticket, but this

year you will look in vain on the ballot for the name

of a colored man or woman! We have never

desired these nominations because of the

job. What we valued in them was the

recognition accorded our race. This year it has

been denied us. We resent this slight,

and what is more we will make our resentment felt

in the election.17

Again Editor Harry C. Smith took the

initiative in protesting Republican policy

by announcing his candidacy for the

Republican gubernatorial nomination in the

primary election of 1922. In his

announcement he stated, "For weeks, yes for

months, from all parts of the state, has

come the call and insistent demand that we

stand as a candidate." Negro

Republicans from Cincinnati, Springfield, Dayton,

Columbus, Xenia, Toledo, Akron,

Youngstown, Sandusky, Zanesville, and smaller

cities had sent Smith letters asking him

to be a candidate for the nomination. He

added:

During that time we canvassed the

situation carefully, considered thoroly [sic] all phases

of the matter and finally decided to

accede to the wishes of the great majority of our people

and enter the race. It is OUR candidacy

pure and simple. . .18

In explaining his candidacy, Smith

complained:

The leaders of our [Republican] party

seem determined to go on ... ignoring our people's

right to representation on the state

ticket. Therefore, it is up to us to get it in any

honorable way we can AND THERE IS SUCH A WAY....

The "way" Smith suggested was

solid Negro support of his candidacy in the primary

election.19

The daily press and white Republicans

took the editor's candidacy of 1922 more

seriously than they had in 1920.

Columbus newspaper correspondent James W.

Faulkner reported that Republican

organization men did not believe that Smith

would be nominated but feared that his

candidacy would promote independent voting

by Negroes. A Cleveland newspaper

reported that the Smith candidacy "HAS CEASED

TO BE

A JOKE AMONG REPUBLICANS" and that "the Negro solidarity is being

shaken."

The view that Smith was a pawn in an intraparty

maneuver was revived. Republican

Governor Harry L. Davis of Cuyahoga

County decided not to run for renomination

in 1922, and Carmi A. Thompson of

Cleveland sought the Republican gubernatorial

nomination. Secretary of State Harvey C.

Smith was also a candidate for the nomi-

nation. Supporters of Harvey C. Smith

believed that the candidacy of Harry C. Smith

had been promoted by the Thompson

faction in order to confuse voters by having

two Smiths on the ballot for the

Republican gubernatorial nomination. However,

Thompson's supporters were fearful of

losing the solid Negro vote in Cleveland and

17. Cincinnati Enquirer, July 20,

1922.

18. Gazette (Cleveland), April 8,

June 17, 1922; Cincinnati Enquirer, March 30, 1922.

19. Gazette (Cleveland), April 8,

1922.

32 OHIO

HISTORY

of the possible sympathy vote Secretary

of State Smith might receive, and subse-

quently declared that "they gladly

would join the forces of Secretary Smith to elimi-

nate the negro [Editor Smith] and

confine the primary election contest to candidates

of the Caucasian race."20

Editor Smith campaigned actively and won

some positive support among the

Negroes. Harry Clay Smith for Governor

clubs were organized in Cleveland, Hills-

boro, Barberton, Akron, Cincinnati, and

Youngstown. He made campaign speeches

in Youngstown, Lorain, Cincinnati,

Elyria, Barberton, Martins Ferry, and other

cities in July and August. In Elyria he

spoke to a large interracial audience in a

public park. He spoke before a meeting

at Cincinnati's Metropolitan Baptist Church,

which was jointly sponsored by the

Universal Negro Improvement Association and

the Hamilton County Negro Republican

League. The standing-room-only audience

responded to his speech

enthusiastically. In northern Ohio, one supporter, The Rev-

erend P. A. Nichols of Toledo, declared:

"Our choice for Governor is the HON. HARRY

CLAY SMITH of Cleveland. 1st, because he

is a Republican; 2nd because he is com-

petent to fill the position; 3rd,

because he is a MEMBER OF THE NEGRO RACE."

In the

primary, Carmi A. Thompson won the

Republican gubernatorial nomination. Editor

Smith obtained a relatively small number

of votes but won the consolation of running

sixth among the nine candidates and

getting more votes than three of his white oppo-

nents for the nomination.21

The motivation behind the support of the

candidacies of Smith and other inde-

pendent black Republicans during the

decade involved more than negative protest

against the failure of their party to

recognize the support given to it by black voters.

These candidacies were conceived also as

positive attempts to force the Republican

party to recognize that the black

electorate was growing more powerful than before

as a consequence of the increasing black

population of the state. Blacks constituted

3.2 percent of the population of Ohio in

1920; that figure would rise to 4.7 percent

by 1930.22 During this time Smith's and

other black candidacies were positive, then,

in the sense that the candidates

conceived of the possibility of victory without the

traditional white support. One of the

objectives of the black independents was to

convince the Afro-American voters that

they could or shortly would be able to elect

independent black candidates and, by

means of that demonstration of power, influ-

ence the Republican party to alter its

policies. As will be seen, this was a more real-

istic goal regarding local elections in

which the black population increase was becom-

ing an important factor than in state

elections. Editor Smith's argument for his

Republican gubernatorial nomination in

the 1922 primary based on Negro support

ran as follows:

Four years ago, the Hon. Frank B. Willis

was nominated as the Republican candidate for

governor of Ohio, receiving but 45,000

votes. Two years ago the editor of The Gazette

received 61,081 votes as [a candidate

for the Republican secretary of state nomination];

over 15,000 MORE VOTES THAN MR. WILLIS RECEIVED IN 1918. Remember there are more

than 125,000 Afro-American voters in

Ohio and then draw your own conclusion.23

20. Cincinnati Enquirer, March

30, April 5, 16, 1922; Cleveland Plain Dealer, April 9, 1922,

in April 15, 1922, Gazette (Cleveland);

Cleveland Plain Dealer, June 9, 1922.

21. Gazette (Cleveland), July 1,

8, 15, 22, 29, August 5, 12, 1922; Warren A.M.E. Church

Bulletin, in ibid., July 29, 1922.

22. Eighteenth Census, 1960:

Characteristics of the Population, Ohio, I, Part 37, p. 54.

23. Gazette (Cleveland), April 1,

1922.

Black Insurgency 33

The fact that there were nine candidates

for the 1922 gubernatorial nomination

made Smith's argument even more

plausible. His failure to win nominations in 1920

and 1922 primaries did not dispel his

belief in the value of his candidacies nor in

the possibility of victory for a black

candidate. Smith claimed that his campaigns in

1920 and 1922 had achieved a limited

objective. As a result of his achievements

in the two campaigns the Republican

leaders of the state had been warned. He wrote:

Our people of Ohio have tired of being

made political "doormats" and propose . . . to

force proper recognition [of

Negroes].... we are proving to the satisfaction of ALL

something they, both black and white,

would never heretofore admit and that is that the

Afro-American vote of this state is many

thousands larger than they thought it was and

that it is large enough to nominate a

candidate for THE REPUBLICAN STATE TICKET....

Several years ago, we recognized the

fact that it would take at least six years, three

campaigns, like we have twice conducted

. . .

to convince the [Republican] leaders as

well as our own people that what we have

herein stated is true.24

With a growing political consciousness

shared by many thousands of Negro voters,

Smith added:

It will not be long before "the

resentment within the party will be strong enough to result

in the nomination of Harry C.

Smith" for a state office or in the securing to Ohio Afro-

Americans the recognition so long

arbitrarily withheld. THE WORK SHALL GO ON!25

Accordingly, Smith again filed as a

candidate for the Republican nomination for

governor in the primary election of

1924. There was also a black candidate, Spring-

field carpenter-contractor George W.

Shanklin, for the Republican nomination for

lieutenant governor. Shanklin's

political biography stated that he had attended Rio

Grande College, had served in the

Spanish-American War, and had been elected as

tax assessor three times in Gallipolis.

Smith and Shanklin supported each other

during the campaign. Shanklin campaigned

in southwestern Ohio while Smith con-

centrated upon the northeastern section

of the state. Smith continued his primary

election campaign efforts through the

remainder of the decade by filing for the

Republican gubernatorial nomination in

1926 and 1928.26

The same factors which moved Smith to

seek a place on the Republican state

ticket impelled other black Republicans

to run for election to local offices in several

Ohio cities. Generally, the black

candidates filed as independents in the general

elections after having failed to win

Republican endorsement in the primaries. The

number of these independent candidates

increased as the decade passed. The most

sustained and effective insurgent

movements in local politics were carried out in

Cincinnati and Cleveland, the cities

having the largest Negro populations in the

state. In 1921 some blacks protested

when the Republicans refused to endorse a

Negro candidate for the Cincinnati City

Council.27 They charged the Republican

party with being ungrateful for their

votes.28 There were independent black can-

24. Ibid., August 19, 1922.

25. Ibid.

26. Ibid., June 21, 28, August 9,

1924, June 12, 1926, June 30, 1928; Cleveland Plain Dealer,

June 14, 1924.

27. The Union (Cincinnati)

November 19, 1921; Ernest M. Collins, "The Political Behavior

of the Negroes in Cincinnati, Ohio and

Louisville, Kentucky" (unpublished Ph.D. dissertation,

University of Kentucky, 1950), 150.

28. Cincinnati Post, November 8,

1921 in Collins, "Political Behavior of the Negroes in

Cincinnati," 73-74.

34 OHIO

HISTORY

didates for council in 1921,

nevertheless most of the voters in Cincinnati's pre-

dominantly black Ward 18 supported the

white independent candidate for mayor

since Wendell Phillips Dabney, who was

the editor of the Union, while admitting

that grievances existed, had advised

Negroes in Cinncinnati to vote the Republican

ticket rather than to risk identifying

themselves with a new party, as the Negroes

of Louisville, Kentucky had done.29

In 1922 the Hamilton County Republican

organization broke a long tradition

by failing to nominate a black candidate

for any county office. This caused even

greater alienation, which was expressed

in part by enthusiastic support given by

black Republicans in Cincinnati to the

candidacy of Editor Smith for the Repub-

lican gubernatorial nomination in 1922.

Subsequently, the Hamilton County

Republican organization, apparently in

an attempt to mollify the alienated black

Republicans, endorsed the appointment of

A. Lee Beaty as an assistant in the

office of the United States District

Attorney for Southern Ohio. Beaty, who had

been a longtime regular Republican, was

a prominent black attorney of Cincinnati

and former state representative from

Hamilton County. Also, Editor Dabney of

the Union was promoted to

paymaster of Cincinnati after having served as assistant

paymaster since 1907. These appointments

did not satisfy the aggrieved black

Republicans. In fact, Dabney resigned

his post in protest against the fact that his

salary had not been increased to

correspond with his higher rank. During the 1924

election campaign Dabney, who formerly

had been a regular, expressed his political

independence. He advised blacks to

"vote for men rather than party." He added:

"Having only recently become

emancipated from Republican Party serfdom, I

most fully realize the evils that have

resulted to our race from its ownership by

that organization since the day the

ballot was given them. Parties, like people,

never respect their slaves."30

Since the Cincinnati Republicans

continued to refuse to nominate a black Re-

publican for city council, Frank A. B.

Hall, a Negro, became an independent

Republican candidate for city council in

1927. Hall was not elected but a local

daily newspaper observed that "for

the first time the colored voters partly con-

centrated on a member of their own

race." Two years later George W. Conrad

and Hall again sought council seats as

independent Republicans. Hall's campaign

was managed by A. Lee Beaty. At a

campaign meeting for Conrad and Hall,

Beaty condemned the Republicans for

failing to give Negroes proper representation

on the party's governing committees. He

stated:

We represent one-fourth of their vote,

but we are not given one of eight places on their

executive committee. We represent

one-fourth of their vote, but we are not given one of

twenty places on their ways and means

committee, and are not given one of ten places on

their platform committee, or one of ten

places on their nominating committee. Either

George Conrad or Frank Hall must teach

them to respect us.31

Neither Hall nor Conrad was elected, but

Hall received more votes in 1929 than

29. Union (Cincinnati), November

5, 1921; Collins, "Political Behavior of the Negroes in

Cincinnati," 73-74. The new party

was called the "Lincoln Party."

30. Beaty received the appointment. Gazette

(Cleveland), July 1, August 26, 1922, June 23,

1928; The Crisis, XXVII (November

1923), 8; ibid., XXIX (November 1924), 13.

31. Cincinnati Times-Star, November

10, 1927; Gazette (Cleveland), November 2, 1929.

Black Insurgency 35

he had in 1927 and demonstrated that

voter support for this black independent

candidate was growing. The Republican

party of Cincinnati apparently learned

the lesson of Hall's candidacies. In

1931 the local Republican organization backed

Hall for a city council seat and he was

elected.32

In contrast to Cincinnati and Columbus,

independent black Republican activity

was most intense and successful in

Cleveland. Yet the causal factors of this

activity were somewhat atypical. The

Republican party in the Cleveland area had

continued to nominate a black city

council candidate and black candidates for the

state legislature during the 1920's.33

Thus, unlike similar movements in other Ohio

cities, the candidacies of independent

black Republicans in Cleveland were not

protests against the failure of

Republican party to nominate any Negro candidates.

Instead, the grievances of the

independents in Cleveland related in part to dissatis-

faction with the behavior of a black

city councilman who was supported by the

party organization. In addition, the

concentrations of Negroes in three Cleveland

wards made the election of more than one

black councilman possible. This pos-

sibility in combination with the failure

of the GOP to nominate more than one

black council candidate also prompted

independent candidacies, some of which

were successful.

Politically conscious progressive

Negroes in Cleveland were appalled by the

record of Thomas W. Fleming, the black

Republican councilman from predomi-

nantly black Ward 11. A. D. (Starlight)

Boyd, black saloon keeper, headed the

Republican machine in Ward 11 and

faithfully delivered its votes to Fleming and

Maurice Maschke, head of the Cuyahoga

County Republican organization, in elec-

tion after election. As a councilman,

Fleming voted according to the wishes of

Maschke and seemingly took little

interest in the conditions of his ward or the

concerns of Negroes in Cleveland.

Consequently, progressive Negroes of Ward 11

pressed Editor Smith of the Gazette to

oppose Fleming for a seat on the council

in the local elections of 1921. Smith,

who did decide to run as an independent

Republican, was endorsed by the Civic

League, the Baptist Ministers' Conference,

the Cleveland Council of Colored Women,

the Universal Negro Improvement

Association, and several other Negro

organizations in Ward 11. Fleming, never-

theless, was reelected even though,

according to the Gazette, there probably was

"notorious skullduggery in the

election booths." Yet Smith made a good showing

32. Collins, "Political Behavior of

the Negroes in Cincinnati," 151-153; Cincinnati Post,

November 11, 1931.

33. In the primary election of 1920

William R. Green sought a Republican nomination for

the state senate and Harry E. Davis, Samuel

E. Woods, Sidney B. Thompson, and W. T. Blue each

attempted to secure a Republican

nomination for the state house of representatives. Davis was

elected to the house, after being the

only Negro to win in the primary election. Remaining a

regular Republican, Davis was reelected

in 1922 and 1924. Chester K. Gillespie, William R.

Green, and Davis sought Republican

nominations for the house in the 1926 primary election.

Again only Davis won, and he was

reelected in the autumn. Davis resigned his seat in the

house upon being elected to the

Cleveland Civil Service Commission in 1928. Perry B. Jackson

won a Republican nomination for the

house in 1928, but Peter Boult, chairman of the Cleveland

convention committee of the National

Afro-American Democratic Association, failed that year

to win a Democratic endorsement for the

General Assembly. Jackson won a house seat in the

general election, and thus Cuyahoga

County was represented by a Negro in the house during

every term of the legislature during the

decade. Gazette (Cleveland), August 7, 1920, August

7, 14, 1926, May 12, November 3, 17,

1928; see Ohio, House Journal for the 1920's. Black

candidates for Cleveland City Council

noted in text below.

36 OHIO HISTORY

in the election returns.34

During the second half of the decade

independent black political activity in Cleve-

land became more intense and effective

than before. Meanwhile, as the black

population increased, both the

Republican and Democratic organizations in Cleve-

land became more solicitious of the

black vote than they had been earlier. In 1925

independent black candidates, Dr. E. J.

Gregg and Harry Harper, challenged

Fleming in the Third District for a city

council seat, and attorney Clayborne

George was an independent black council

candidate from the Fourth District. Only

Fleming was elected. But, by 1927 the black

electorate had increased to the point

that it could elect more than one member

of the council. In 1927 George and

Gregg were elected as independent

Republicans, and Fleming was reelected with

the endorsement of the Republican

organization. Councilmen George and Gregg,

although they had been independent

Republican candidates, entered the minority

caucus of the Democratic councilmen.

They were expected to receive the support

of the Democratic minority on most of

the measures which they sponsored. Gregg

had the endorsement of W. B. Gongwer,

chairman of the Cuyahoga County

Democratic organization. This was the

first time in Cleveland councilmanic history

that a Negro had been endorsed by the

Democratic party.35

Subsequently, apparently in an attempt

to appease alienated black voters, the

Republican councilmen backed attorney

Harry E. Davis for election as a member

of the Cleveland Civil Service

Commission. However, charges were made that the

organization's motive in sponsoring

Davis, who represented Cuyahoga County in

the Ohio House of Representatives, was

to rid "itself of the responsibility of back-

ing him for the state senate." In

January 1928, Davis became the first Negro mem-

ber of the Civil Service Commission

after receiving the votes of thirteen of the

twenty-five councilmen for the post.36

In 1929, Maschke and the members of the

Cuyahoga County Republican

organization were embarrassed by the

indictment of Councilman Fleming for

soliciting and accepting a bribe to use

his influence on the council toward the pas-

sage of special legislation. He was

subsequently convicted of the charge and

sentenced to serve two years and nine

months in the Ohio Penitentiary.37 Fleming's

conviction brought Maschke under the

fire of the city's daily newspapers. One

editor wrote:

Maschke made Fleming. In turn, Fleming

has delivered to Maschke. And today, Maschke

stands responsible for the conditions

which have made Tom Fleming what he is.

The conviction of Tom Fleming is the

conviction of the rule of Maurice Maschke.38

Another editor held that Maschke should

not be permitted to name the person to

fill the council vacancy created by

Fleming's resignation. He added:

Many Clevelanders will feel that a

colored man should be named in place of the colored

ex-councilman. There are plenty of

colored residents of the Third District amply qualified

to represent both the district and the

entire city. But there should be no consideration

34. Gazette (Cleveland), March 3,

November 24, 1917 May 14, October 29, November 12,

December 17, 1921, February 4, March 25,

1922.

35. Ibid., October 17, November 7, 1925, November 12, 1927,

January 14, 1928, October

19, 1929.

36. Ibid., January 7, 1928.

37. Ibid., February 9, 16, 1929.

38. Cleveland Press, February 9,

1929.

Black Insurgency 37

whatever of any man, whether white or

colored, who would enter the Council as the

representative. .. of Tom Fleming. There

should be no consideration of any aspirant who

has even identified himself with

Fleming's past political activities.39

The Republican organization subsequently

backed for the vacancy a man of

unquestioned character, Dr. Russell S.

Brown, pastor of the Mt. Zion Congrega-

tional Church, one of the prominent

Negro churches in the city. Dr. Brown was

experienced in welfare work, scholarship

and teaching, and was not identified with

any political faction. He was elected

with the votes of the fourteen white Republi-

cans and two Negroes on the council.

This turn of events apparently reconciled

Councilmen George and Gregg to the

Republican organization. Thereafter, they

began to meet with the Republican

councilmanic caucus.40

The Democratic party in Cleveland began

to make a special appeal to black

voters in the latter part of the 1920's

in recognition of their growing political

power. In the local election of 1927

Democratic county chairman Gongwer en-

dorsed Negro candidates for city council

and municipal court judge. In the summer

of 1928 Gongwer appointed forty-two

Negroes as precinct committeemen in wards

11, 12, and 18. Thus, all the Democratic

precinct committeemen in wards 11 and

12 were black, although some of the

Republican counterparts in the same wards

were white but did not all live in the

wards. Gongwer endorsed Dr. James A. Owen

for a council seat in the election of

1929, marking only the second time the

Democratic organization had backed a

Negro council candidate.41

A considerable amount of independence

continued on the part of black candi-

dates for office in Cleveland, in the

context of the new solicitation of black support

by both parties. There were numerous

Negro councilmanic candidates in addition

to Dr. Owen in the election of 1929.

Attorney Lawrence O. Payne and Dr. Leroy

Bundy ran as independent candidates.

Attorney Chester K. Gillespie and Council-

man Gregg were identified with the

Progressive Government Committee supporting

the city manager plan. Councilman George

was a Republican candidate. Bundy,

George, and Payne were elected. In

addition, Mrs. Mary B. Martin, a local black

educator, was elected to serve a term on

the Cleveland Board of Eduation.42

Independent political activity by black

candidates and their supporters also

occurred in several Ohio cities which

had Negro populations smaller than those in

Cincinnati and Cleveland. For example,

eight black candidates, some of whom

may not have been independents, ran for

public office in Columbus and Franklin

County during the 1920's. In 1920 Dr.

Thomas W. Burton, a Springfield physician,

was a candidate for coroner. Robert W.

Pulley of Oberlin was a candidate for

sheriff in 1922. In 1925 Harry H. Stotts

ran as a candidate for councilman-at-large

in Zanesville and thereby became the

first Negro to seek elective office in that city.

Also in 1925 Wilberforce University

Athletic Director Dean Mohr was a candidate

for clerk of the Springfield municipal

court.43

39. Cleveland Plain Dealer, February

11, 1929.

40. Gazette (Cleveland), February

23, March 9, 1929.

41. Ethel Kennedy to W. B. Gongwer, May

25, 1927, George A. Myers Papers, Ohio Historical

Society; Gazette (Cleveland),

September 1, 1928, October 19, 1929; Cleveland Plain Dealer,

October 15, 1919.

42. Gazette (Cleveland), October

19, November 2, 9, 1929.

43. J. S. Himes, Jr., "Forty Years

of Negro Life in Columbus, Ohio," Journal of Negro

History, XXVII (April 1942), 145; letter of Thomas W. Burton to

Harry C. Smith, November

8, 1920, in November 20, 1920, Gazette

(Cleveland); ibid., July 29, August 5, 1922, September

19, 1925.

38 OHIO

HISTORY

The black Republican insurgency of the

1920's involved even more than the

patronage dispute, promotion of black

candidates, and the wooing of the growing

black electorate. Insurgents also

directed attention of the black electorate to white

Republican nominees' records on the Klan

issue or on broader civil rights issues.

Candidates on Republican state,

congressional, and presidential tickets were sub-

jected to scrutiny in these areas. In

1924, former governor and Republican

nominee, Harry L. Davis, was criticized

because he had been endorsed by the

Ku Klux Klan and because he had not

denied that he was a Klan member. Black

critics of the Republicans at the state

level were better organized in 1926 than they

had been before. In the autumn of 1926 a

non-partisan league of Negro voters

was formed at a meeting in Columbus. The

league elected Dr. E. J. Gregg of

Cleveland, president, and attorney Sully

Jaymes of Springfield, vice president. It

claimed representation from thirty-four

counties. Myers Y. Cooper and James O.

Mills, respectively the Republican

nominees for governor and lieutenant governor in

1926, were the chief targets of the

critics. Both men were charged with discrimina-

tion against blacks in their businesses

and with not denying that they were members

of the Ku Klux Klan or that they were

endorsed by it. In a letter to G. H. Townsley,

publicity director in the Republican

state committee, Editor Smith of the Gazette

wrote:

Permit me to assure you that a denial of

civil rights in public places of entertainment as

is said to be the case in... James 0.

Mills' chain of restaurants throughout Ohio is not

atoned for by the employment of 227, or

227 million "colored" people.

The same is true in the case of Myers Y.

Cooper... ; it is not how many "colored"

men he employs but whether or not he is

a member of the Ku Klux Klan and endorsed

by that lawless organization, as

repeatedly stated by the daily press of the state. . . and

never to my knowledge, at least, denied

by him. The statement has also been made and

not contradicted that Mr. Cooper draws a

color-line in his real estate dealings in

Cincinnati.

Under the circumstances, it is simply

ridiculous to expect self and race respecting

"colored" men and women ... to

cast their votes for either of these two men....44

Smith was subsequently informed that the

state Democratic campaign committee

had circulated one hundred thousand

copies of his Townsley letter throughout the

state prior to the election in which

Cooper lost to incumbent Democrat Victor

Donahey.45 Criticism of

Cooper was revived when he was renominated for gover-

nor by the Republicans in 1928. For

example, a letter, written by a Negro teacher

at Douglass School of Cincinnati and

widely circulated before the election, charged

Cooper with using pressure tactics and

harassment to drive her and her sister out

of a house which they had purchased in

an area in which Cooper's real estate firm

owned much property.46

A similar aspect of the insurgency had

manifested itself in presidential elections

beginning in 1924. A vigorous attempt

was made to win representation for Ohio

Negro Republicans at the 1924 Republican

National Convention which was to be

44. Gazette (Cleveland), November 1, 1924, October 9, 1926; letter,

October 21, 1926, in

ibid., October 30, 1926.

45. Letter of Harry C. Smith to Governor

A. V. Donahey, November 6, 1926, in ibid.,

November 20, 1926. In the November 20th

letter Editor Smith stated that the Negroes had "un-

doubtedly furnished ... the balance

of votes necessary to insure your [Donahey's] re-election...."

46. Letter of Hettie G. Taylor, To Whom It

May Concern, October 15, 1928, in ibid., Octo-

ber 20, 1928.

Black Insurgency 39

held in Cleveland. The Abraham Lincoln

Republican Club of Dayton took the lead

in the campaign to obtain such

representation. In a memorandum addressed to the

state party leaders the Dayton

organization held that one of the delegates-at-large

from Ohio should be a Negro on the

grounds that the increasing number of Negro

voters in the state had been loyal to

the party over the years and thus deserved

representation at the convention.47

The adviser of the Dayton Negro club stated

that his organization's campaign was

given editorial support by the Negro press and

encouragement by Negro organizations.

The campaign included the circulation of

petitions in support of a Negro

delegate-at-large. Some of those who were chagrined

by the failure of the state party to

back a Negro delegate-at-large began a move-

ment to create an organization which

would apparently promote independent voting

by Afro-Americans in the fall election

in the event that Negroes should not be

represented among the

delegates-at-large.48 Subsequently, leading Negro Republi-

cans of the state met in Columbus to

discuss the subject at the request of the

Dayton Abraham Lincoln Republican Club.

The conferees resolved to ask for a

conference with the state Republican

executive committee and for a Negro

delegate-at-large, but both requests

were denied by the executive committee. In

response to the denial of a black

delegate-at-large Editor Smith wrote: "This time,

they [Afro-Americans] do not intend to

be shunted aside without making those

responsible for it pay in the loss of

thousands of votes on election day in Novem-

ber, 1924."49

Independent Republicans were appalled by

the record of the Republican con-

vention in Cleveland. The convention did

not condemn the Ku Klux Klan and

nominated Calvin Coolidge, who had

continued the racial segregation of federal

employees which had been initiated by

the Democratic administration of Woodrow

Wilson.50 As a result, the

insurgents supported either Robert M. LaFollette or

John W. Davis, presidential candidates

of the Progressive and Democratic parties

respectively. The Independent Colored

Voters League of Cuyahoga County

(Cleveland) was organized by The

Reverend Horace C. Bailey, Peter Boult,

Walter Brown, and other Clevelanders.

The league decided to send LaFollette

campaign material throughout the state.

Rev. Bailey toured Negro communities

in many towns and cities of northeastern

Ohio speaking for LaFollette at the

request of local and state LaFollette

campaign committees. Oswald Garrison

Villard, editor of the Nation and

vice president of the National Association for the

Advancement of Colored People, and old

Cleveland progressive Peter Witt, then a

47. To the State Executive Committee of

the Republican Party at Columbus

Assembled,

November 22, 1923, in ibid., December

1, 1923.

48. Letter of E. T. Banks to Harry C.

Smith, January 21, 1924, in ibid., January 26, February

9, 1924.

49. Ibid., February 16, 23, 1924.

50. Ibid., May 24, June 14, 21,

28, July 5, 19, 1924. During the 1920's the national Republican

party's policies in relation to Negroes

tended to be regressive. During the decade the national

party: 1) adopted platform planks on

civil and political rights that were more vague and inex-

plicit than before; 2) attempted to

reduce the participation of blacks in the affairs of the national

party; 3) failed to cause the enactment

of a federal anti-lynching law; 4) was generally indiffer-

ent to the issue of federal protection

of the right to vote; 5) did not discontinue racial segregation

of federal employees; and 6) gave fewer

federal appointments to Negroes than it had before the

1920's. The national Republican party's

relationship to blacks during the decade is discussed by

Richard B. Sherman, "Republicans

and Negroes: The Lessons of Normalcy," Phylon, XXVII

(Spring 1966), 63-79; Richard B.

Sherman, "The Harding Administration and the Negro: An

Opportunity Lost," Journal of

Negro History, XLIX (July 1964), 151-168.

40 OHIO HISTORY

city councilman, were among the

prominent men who addressed the league meet-

ings in September and October. League

members spoke for LaFollette in Paines-

ville, Akron, and Springfield in late

October. Among those who campaigned for

the Democratic presidential ticket were

black students at Ohio University who

formed a Davis Club. Lawrence T. Young,

who headed the group, stated:

There is just a nice little group of us

and we often discuss the political situation as best

we know it, and we talk about how we

intend to exercise our right of franchise. During

the summer, we have been condemning

Coolidge because of his insulting segregation and

his silence attitude in reference to the

Ku Klux Klan, and we decided to help Davis as

much as in our power and to exert

whatever influence we could in his behalf. We, too,

although young in politics, have come to

. . . sense that we owe no allegiance to any

party and that what we want are men and

not parties.51

It should also be noted that the

national organization of the NAACP, in reaction

against the negative record of the

Coolidge administration on racial issues, en-

couraged its members across the country

to vote for candidates on the basis of

their merits rather than on their party

affiliation. The Crisis took an independent

stance by publishing a symposium on the

relative merits of the presidential candi-

dates. Speakers representing the NAACP

were sent to various parts of the nation

to promote this view. For example, at

the September Emancipation Day cere-

monies in Springfield, Ohio, James

Weldon Johnson, Secretary of the NAACP,

urged Negroes to vote independently and

vote against any candidate who was a

member of or was supported by the Ku

Klux Klan. The tendency toward black

independence in presidential politics in

Ohio was continued in the 1928 election.

The Al Smith League of Colored Voters of

Ohio was formed in the summer of the

election year. The league was an

independent organization rather than a Demo-

cratic one, although it did campaign for

the Democratic presidential candidate. The

stated purpose of the league was to

promote Al Smith's candidacy and those of any

"such other officials as may be

considered favorable to the progress and advance-

ment of our people." Dr. Joseph L.

Johnson, former United States Minister to

Liberia, was elected president of the

organization. Other leaders of the league

represented Cincinnati, Cleveland,

Columbus, Dayton, Rendville, Springfield, and

Toledo.52

The most publicized and thorough

campaign against an Ohio Republican nomi-

nee was launched in 1930. United States

Senator Roscoe C. McCulloch became

the target of the campaign because he

had voted for confirmation of the appoint-

ment of Judge John J. Parker of North

Carolina as an Associate Justice of the

United States Supreme Court. The NAACP

and others charged that Judge Parker

had exhibited anti-black behavior

earlier in his career and thus opposed his

appointment to the court by President

Herbert Hoover. Senator McCulloch

received "an avalanche of pleas

from his Negro and white constituents" asking

that he vote against Judge Parker's

confirmation, but he voted for confirmation

anyway.53 Consequently,

leaders of the NAACP in Ohio and others began an

51. Gazette (Cleveland), August 30, September 13, 27, October 4,

18, 25, 1924.

52. "How Shall We Vote?" "The

Crisis, XXIX (November 1924), 12-15; Gazette (Cleve-

land), September 27, 1924, September 1,

1928.

53. Walter White, "The Test in

Ohio," The Crisis, XXXVI (November 1930), 373. See also

telegram of Charles W. White to Senator

Roscoe McCulloch (copy) enclosed in letter of

Charles W. White to Walter White, April

5, 1930, NAACP Records.

Black Insurgency 41

effort to prevent Senator McCulloch from

continuing to serve in the Senate. The

president of the Cleveland NAACP branch

wrote; ". .. I am utilizing every

opportunity here to have Negro

organizations go on record as being opposed to

the candidacy of Senator McCulloch, both

for nomination and election" in the

1930 elections.

Among the Cleveland organizations that

came out early against Senator

McCulloch were the East End Political

Club, St. James Forum, and the Harlan

Club.54 McCulloch's critics

had little opportunity to prevent his nomination

because he had no opponent in the

Republican party, but an attack was escalated

after the primaries. For example, The Reverend

D. O. Walker of St. James

African Methodist Episcopal Church in

Cleveland urged his audience to vote for

Robert J. Bulkley, the Democratic

senatorial nominee, and to defeat Senator

McCulloch. Walker also stated: "It

is singular that, although colored people

throughout Ohio urged the rejection of

the appointment [of Judge Parker] both

Ohio Senators voted for it. Either the

Republican Party feels we will give it our

support no matter what it does, or it

thinks our memories are so short that we

can be slapped in the face and forget

before election."55

The national leaders of the NAACP,

apparently sensing a Negro revolt in Ohio,

decided to make the defeat of Senator

McCulloch a test of Negro political power.

A state conference of local NAACP branches

was established with the political

efficacy of the organization in mind.

The long range purpose of the conference

was to coordinate the general activities

of the local branches, but it was understood

that in the short run the conference

could promote the defeat of Senator

McCulloch. Prior to its creation, NAACP

Secretary Robert W. Bagnall observed:

"One special feature of the Ohio

Conference is that it is to serve as an attempt to

organize the state to seek the defeat of

Senator McCulloch ...."56 The Conference

of the Ohio Branches of the NAACP took

the lead in the anti-McCulloch fight.

Branch delegates, meeting in Columbus,

voted unanimously to oppose his election.

They decided to carry out an

anti-McCulloch rather than a pro-Bulkley campaign,

although there was some strong sentiment

for the Democrat.57 The delegates

stated:

In taking this action the N.A.A.C.P. is

not affiliating or co-operating with any political

party. Its action is wholly an

independent one, planned, financed and carried to con-

summation by the organization itself.

The issue is clearly drawn.

Senator McCulloch chose to override the

protests of his Afro-American constituents

and of liberal Americans throughout the

country who were against placing upon the

Supreme Court a man who had urged,

through motives of political selfishness, that parts

of the Constitution and rights of

Afro-Americans be disregarded.58

The anti-McCulloch campaign was headed

by C. E. Dickinson, president of the

conference of Ohio NAACP branches.59

The state NAACP conference made over

54. Letter of Charles W. White to Walter

White, May 28, 1930, ibid.

55. Gazette (Cleveland), September 20, 1930.

56. Memorandum to the Board of

Directors, July 14, 1930 (copy), NAACP Records. See

also The Crisis, XXXVII (December

1930), 418.

57. Minutes of the Second Conference of

the Ohio Branches of the National Association for

the Advancement of Colored People,

Columbus, Ohio, October 5, 1930, NAACP Records.

58. Gazette (Cleveland), October 11, 1930.

59. The Crisis, XXXVII (December 1930), 418.

42 OHIO HISTORY

19,000 communications with Ohio Negro

voters on the McCulloch issue. The

anti-McCulloch literature mailed by the

state organization between October 3 and

November 3 included small printed cards,

window cards, postal cards, letters,

sample ballots with McCulloch's name

crossed out, press notices, and copies of the

Democratic party platform.60 The

national organization of the NAACP also

played a noteworthy role in the campaign

against McCulloch. The progress of the

efforts against McCulloch were reported

in the Crisis. Walter White, acting secre-

tary of the NAACP, in a Crisis article

described the Negro political revolt in

Ohio. As examples of those who were fighting

McCulloch, White mentioned "a

Negro of influence [in Cincinnati] who

had been a life-long Republican," "one of

the leading ministers of

Cleveland," "one of the leading women social workers of

the state," "a prominent Negro

lawyer of Ohio and the dean of Negro novelists."

White also wrote:

The revolt is especially to be seen

among the younger and more progressive Negroes of

Ohio. One of these, a lawyer, who is

working actively against the Republican nominee,

has declared that "the minds of

Ohio Negroes are set against McCulloch. Approximate

solidarity of Negro voters against him

may spell the difference between victory and

defeat."61

National leaders of the association

visited Ohio to speak against the Republican

senatorial nominee. Both Walter White

and W. E. B. DuBois, editor of the Crisis,

addressed Ohio audiences during the days

before the election.62 The campaign

effectively aroused interest in the

issue. In Columbus, for example, "meeting after

meeting, rally after rally" were

held in opposition to the election of Senator

McCulloch, and the Columbus NAACP

membership increased to over one thousand

during the anti-McCulloch campaign.63

The results of the election were gratifying

to the Ohio NAACP organizations and

others who had engaged in the massive

anti-McCulloch effort. Robert J. Bulkley

was elected to the United States Senate.

The factors causing McCulloch's defeat

included the prohibition issue and the

general economic conditions, but the

black vote was influential. One scholar

reported: "The colored districts of

Cleveland, Toledo, Akron, Columbus, and

Canton went to McCulloch's Democratic

opponent by margins of from 50 to 86

per cent, while many voters in these

districts refrained from voting for United

States Senator."64

The anti-McCulloch campaign was a climax

of the insurgent activity which had

expanded during the 1920's. Yet the

independence movement had no substantial

effect upon the general black voting

patterns through the 1932 elections. There

were politically active members of the

black business and professional community

who remained regular Republicans and

tried to maintain the black vote for the

Republican party during the years of

growing dissent. These persons campaigned

for white Republican candidates and in

some instances campaigned against inde-

60. Letter of Geraldyne R. Freeland,

Secretary to the President of the State Conference, to

Walter White, November 4, 1930, NAACP

Records.

61. White, "The Test in Ohio,"

374.

62. Letter of Geraldyne Freeland to

Walter White, November 4, 1930, NAACP Records.

63. Minor, "The Negro in

Columbus," 188.

64. John G. Van Deusen, "The Negro

in Politics," Journal of Negro History, XXI (July

1936), 271.

Black Insurgency 43

pendent black candidates. For example,

Editor Smith estimated that about fifty

Negroes were in the employ of his white

opponents for the Republican guber-

natorial nomination in 1922. Carmi A.

Thompson was endorsed by Mrs. Harry E.

Davis, the wife of a black state

legislator, and by Miss Hallie Q. Brown, instructor

at Wilberforce University and prominent

official in the National Association of

Colored Women. Some of Editor Smith's

black opponents argued that his candi-

dacy made "enemies for the

race" and that a vote for him would be wasted

because a Negro had no chance of

winning. He was also a victim of smears

designed to curtail his popularity among

Negroes. It was alleged that he employed

only white people in his newspaper

office and that he was living with a white

woman.65

Even so, the Democratic party, because

of its identification with the racial

policies of the white South, had more

influence than the black regular Republican

campaign workers on the continuance of

the black voting pattern during this

period. The Democratic party was not

regarded as a viable alternative by most

black voters, whether or not they were

disenchanted with the Republican party,

until the Democrats' anti-black image

was altered by the inclusion of blacks in the

New Deal programs. Thus, in the

presidential election of 1932 Herbert Hoover

received 72 percent of the black vote in

Cleveland and 71.2 percent in Cincinnati.

In the election of 1928 Hoover had

obtained smaller percentages of the black vote

in these cities. Al Smith had won 30

percent of the black votes in four predominantly

Negro wards in Cleveland, and Hoover

gathered only 59.5 percent in Cincinnati in

1928.66 In the context of the

deteriorating economic situation of blacks and the

regressive racial policies of the

Republican party during the Hoover administration

it is not likely that more black voters

supported Hoover in 1932 than in 1928 because

of increasing popularity of the

President and the Republican party. A more credible

interpretation of the increased black

vote for Hoover would be that the black voters

who had expressed protest against the

Republican party by supporting the Democratic

ticket in 1928 voted Republican in 1932

because a Democratic victory was much

more probable in 1932 than in 1928.

The black independence movement of the

1920's and its attendant causes pre-

pared the black electorate for the

political realignment which occurred during the

New Deal. The independence movement and

the social and political situations out

of which it arose in effect constituted

a course in political reeducation for black

voters and white politicians. One of the

lessons directed at black voters was that

the Republican party was not sacrosanct

and that opposition to it was respectable.

A new generation of black voters grew to

maturity while the Grand Old Party's

image as a hallowed institution was

being eroded by harsh criticism of it in every

election from 1920 to 1932. The critics

were respected members of the black

middle class. The leadership of the

independent movement was derived largely

from the black professional class, which

included lawyers, newspaper editors,

clergymen, teachers, and physicians. Yet

it should be noted that the insurgency was

65. Gazette (Cleveland), July 8, 22, 29, August 5, 12, 1922. See

also Mrs. Karl F. Ritter,

"Teacher-Elocutionist-Writer,

Hallie Q. Brown," Women of Ohio (Martha Kinney Cooper

Ohioana Library Year Book 1973), 26.

66. Moon, Balance of Power, 18;

Ernest M. Collins, "Cincinnati Negroes and Presidential

Politics," Journal of Negro

History, XLI (April 1956), 132.

44 OHIO

HISTORY

not entirely a middle class phenomenon.

The fact that the Universal Negro Im-

provement Association (UNIA) sometimes

participated in the movement indicated

that blacks of the lower economic class

were also involved in it. Membership of

the UNIA, the black nationalist

organization founded by Marcus Garvey in 1914,

was drawn largely from the masses of

economically deprived blacks. Local and

state units of the UNIA in Ohio

criticized and opposed regular Republicans during

the 1920's. William Ware, president of

the Cincinnati division of the UNIA stated:

The Negroes' lamentable condition

here [Cincinnati] is largely caused

by sticking to

preachers and the Republican

party.... Many of them go to the

Republican campaign

managers, get about fifty dollars or a

suit of clothes and solemnly say, my church is with

you.... Our white speakers are always

talking about Abraham Lincoln, and their black

mammies. We are tired of that stuff.67

The Cleveland division of the UNIA

endorsed Harry C. Smith as an independent

black city council candidate in 1921.68

The Cincinnati UNIA division supported

the ticket of the Charter Party, a local

third party, in 1927.69 A state convention

of UNIA delegates backed the Democratic

candidate for President in 1928.70 The

growing number of independent precedents

set by the black insurgents prior to the

New Deal made opposition to Republican

candidates or affiliation with the

Democratic party a less difficult step

than it would have been in 1920 when it was

taboo to ally with the Democrats. The

change of attitude in relation to party

affiliation was apparent in Cleveland in

1930 when a young men's Democratic club

was founded there. In a report about the

club, a local black newspaper stated that

although in earlier years it had been

"a disgrace to be a Democrat. . ., colored

Democrats have become popular, and even

prominent Republicans are talking of

joining the ranks."71

There is also some empirical evidence,

derived from election statistics in pre-

dominantly Negro wards, which indicates

that the political realignment during the

New Deal was facilitated by earlier

political circumstances. Proportionately more

black voters left the Republican party

in cities which had experienced vigorous and

successful black political independence

movements during the 1920's than in cities

that had not had this experience. Black

political insurgents had been very active

and relatively effective in Cleveland

and Cincinnati. Black independents had

operated in Columbus but their

effectiveness had been severely limited by the

absence of a political ward system in

Ohio's capital city. Black political indepen-

dence in Chicago had apparently been

minimized by the exceptional efforts made

by the Chicago Republican machine in the

person of Mayor William Hale Thompson

to maintain the loyalty of black voters

to the party.72 During the 1930's higher per-

centages of black voters broke with the

Republican party in Cleveland and Cincinnati

than in Columbus and Chicago. In the

1936 presidential election 66.4 percent of the

voters in Cleveland's Ward 17 and 62.8

percent of the voters in Cincinnati's Ward

67. Wendell Phillips Dabney, Chisum's

Pilgrimage and Others (Cincinnati, 1927), 21-22.

68. Gazette (Cleveland), October

29, 1921.

69. The Union (Cincinnati),

October 1927, in Dabney, Chisum's Pilgrimage and Others, 21.

70. Gazette (Cleveland),

September 29, 1928.

71. Cleveland Call & Post, April

12, 1930, in April 26, 1930, Gazette (Cleveland).

72. Gordon, "The Change in the

Political Alignment of Chicago's Negroes During the New

Deal," 587-588.

Black Insurgency 45

16 were Democratic while only 42.6

percent of the voters in Columbus' Ward 7

and an estimated 49 percent of Chicago's

black voters were Democratic.3 True,