Ohio History Journal

WILLIAM E. GIENAPP

Salmon P. Chase, Nativism,

and the Formation of the

Republican Party in Ohio

Accounts of the formation of the

Republican party traditionally

emphasize the political upheaval of

1854. In this year the party first

took shape in Michigan and Wisconsin,

and in several other states fu-

sion anti-Nebraska coalitions, which are

often viewed as proto-

Republican organizations, contested the

fall elections.1 Certainly the

momentous political events of that year

unleashed forces that eventu-

ally culminated in the formation of the

Republican party throughout

the North. Nonetheless, little was

accomplished toward estab-

lishing a permanent party organization,

and at the end of the year few

competent political observers believed

that Republicanism would ei-

ther gain a substantial following in the

free states or become a perma-

nent organization. The events of 1854

gave a boost to the Republican

movement, but the first significant

steps to organize the party in key

northern states occurred the following

year.

Political developments in Ohio in 1855

were particularly significant

in the Republican party's early history.

As the nation's third most

populous state, Ohio exercised

considerable power in national affairs,

and consequently its politics commanded

widespread attention.

Moreover, the drive to launch the party

established Salmon P.

Chase as head of the state organization,

a development which cata-

pulted him to the front ranks of the

Republican national leadership, a

position he occupied for the rest of his

life. Under Chase's guidance,

Ohio Republicans would take the lead to

organize a national party on

William E. Gienapp is Assistant

Professor of History at The University of Wyoming.

Professor Gienapp is grateful to the

Mabelle McLeod Lewis Memorial Fund, Stanford,

California, for financial support that allowed him to

complete much of the research for

this essay. The University of California, Berkeley, and

the University of Wyoming pro-

vided essential computer funds. Finally,

he would like to thank Stephen Maizlish for

many fruitful conversations concerning Ohio politics in

this period.

1. A good example of this emphasis is

Allan Nevins, The Ordeal of the Union (New

York, 8 vols., 1947-1971), v. 2, 316-46.

6 OHIO HISTORY

the same basis as prevailed in the

state. Ultimately, few leaders

would make as significant a contribution

to the creation of a national

Republican party.

Anti-slavery extensionism and

anti-southernism, revitalized by the

passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act in

May, and nativism, repre-

sented by the Know-Nothing order,

combined in 1854 in Ohio to

produce an unprecedented popular revolt

against the old parties.2 In

July various anti-Democratic elements,

including Whigs searching for

a new political home, Free-Soilers eager

to form a more powerful anti-

slavery organization, anti-Nebraska

Democrats angered by their

party's support of the repeal of the

Missouri Compromise, Germans

alienated from their traditional

Democratic allegiance, and Know-

Nothings just beginning to sense their

extraordinary power in the

state, all came together in Columbus to

form a temporary coalition to

meet the present crisis and to nominate

a People's state ticket.3

More a conglomeration of opposition

factions than a tightly knit po-

litical organization, the People's party

scored an astonishing triumph

in October. It swept the state with an

unprecedented majority of al-

most 70,000 votes and won every

congressional contest. The badly

battered Democrats managed to carry only

eleven counties in the en-

tire state.4 Exhilarated by

their triumph, opposition leaders immedi-

ately turned their attention to the 1855

state election when the gov-

ernorship would be at stake. In the

dizzying political atmosphere

that prevailed following the 1854

election, Salmon P. Chase, the most

prominent Free-Soiler in the state,

perceived a glittering opportunity

to recoup his fallen political fortunes

and at the same time realize a

long cherished dream of organizing a

powerful antislavery party.

The sincerity of Chase's hatred of

slavery is beyond challenge. He

had committed himself to the antislavery

movement in the 1830s

when it was not respectable; he had

braved anti-abolitionist mobs;

he had legally fought for black rights

in the face of deeply-rooted

racism; and he had diligently labored

since the early 1840s to pro-

mote political antislavery. As his

commitment to political activity

grew, however, so too did his ambition.

Among the handsomest of

2. Eugene H. Roseboom, The Civil War

Era: 1850-1873 (Columbus, 1944), 277-94.

3. For the 1854 People's movement, see

Stephen E. Maizlish, The Triumph of Sec-

tionalism: The Transformation of Ohio

Politics, 1844-1860 (Kent, Ohio,

1983). 188-93,

197-206. Maizlish's account is weakened

by a failure to perceive the critical role of the

Know-Nothings in the 1854 contest. For

the proceedings of the People's convention,

see the Ohio State Journal, July

14, 1854.

4. The returns are given in the Whig

Almanac, 1855. Democratic congressional cand-

idates fared even worse, winning only

six counties statewide.

Salmon P. Chase 7

American politicians, over six-feet tall

and of sturdy build, he was, in

the words of an Ohio political leader,

"as ambitious as Julius Cae-

sar." Chase was also unbearably

self-righteous and decidedly du-

plicitious in his political dealings-his

enemies called him "a political

vampire" and "a sort of moral

bull-bitch."5 Ceaselessly pontificating

about his disinterested commitment to

the antislavery cause, he dis-

played (like many politicians) an

increasing inability to distinguish

between his own political fortunes and

its advancement.

Chase was by this time a lame duck.

Elected to the Senate in 1849

as the result of a bargain between

Democrats and Free-Soilers, he

was due to retire the following March.

Never very popular in the

state, Chase craved public adoration,

and he found the possibility of

his election as governor particularly

attractive. As was his usual mode

of operation, he commenced actively

lining up support while denying

that he had any interest in the office.6

Despite his eagerness for the

governorship, Chase displayed

considerable ambivalence about the

Republican movement.7 He par-

ticularly feared that his adversaries

would control any fusion organi-

zation. Eventually, however, the Ohio

leader and his advisers con-

cluded that the drive to organize a

Republican party represented the

best chance to unite the opposition

under their guidance. Antislavery

Congressman Joshua R. Giddings was

especially prominent in pro-

moting this view. When some Free-Soilers

proposed beginning anew

in 1855 and holding a separate

convention, James M. Ashley, one of

5. Robert Warden, Private Life and

Public Services of Salmon P. Chase (Cincinnati,

1874), 329, 529; Albert G. Riddle to

Joshua R. Giddings, quoted in David H. Brad-

ford, "The Background and Formation

of the Republican Party in Ohio, 1844-

1861" (unpublished Ph.D.

dissertation, University of Chicago, 1947), 85; Roeliff

Brinkerhoff, Recollections of a

Lifetime (Cincinnati, 1900), 118; James Ford Rhodes,

History of the United Slates from the

Compromise of 1850 (New York, 7 vols.,

1892-

1906), v. 1, 449. Maizlish, Triumph

of Sectionalism, presents considerable evidence of

Chase's duplicity. See in particular his

discussion of Chase's election to the United

States Senate in 1849, 121-43, esp.

131-33, 138-39. Peter F. Walker, Moral Choices:

Memory, Desire, and Imagination in

Nineteenth-Century American Abolition (Baton

Rouge, 1978), 305-29, presents a

stimulating discussion of Chase's character and

thought.

6. Chase to E. S. Hamlin, November 11,

1854, Charles Sumner Papers, Harvard

University; Chase to Hamlin, January 22,

1855, Salmon P. Chase Papers, Library of

Congress; Chase to Oran Follett,

February 14, 1855, L. Belle Hamlin (ed.), "Selections

from the Follett Papers," Ohio

Historical and Philosophical Society Quarterly Publica-

tions, 13 (April-June, 1918), 64; R. P. L. Baber to John

Sherman, October 16, 1854,

Confidential, John Sherman Papers,

Library of Congress.

7. Chase to Julian, January 20, 1855,

Giddings-Julian Papers, Library of Congress;

Austin Willey to Chase, March 26, 1855,

Chase Papers, LC; Chase to Follett, January

1, May 4, 1855, "Follett

Papers," 61, 73.

8 OHIO HISTORY

Chase's most trusted lieutenants,

anxiously urged him to put an end

to it; instead, the Chase men should

continue to push fusion "upon

the same plan of last year." Ashley

was confident that the Free-

Soilers could dominate any such fusion

convention, and increasingly

Chase and his circle viewed the 1854

People's party as the spring-

board from which to launch a new

antislavery party. In the first

months of 1855, the notion that a

convention of the anti-Nebraska

forces would be called to organize the

Ohio Republican party crystal-

lized. By spring Chase, recognizing the

importance of Ohio acting in

concert with other states, was

energetically promoting the Republi-

can cause.8

The major obstacle confronting Chase's

blossoming gubernatorial

ambitions was the power of the Ohio

Know-Nothings. So called be-

cause members were instructed to respond

"I know nothing" if ques-

tioned about it, this secret nativist

society had been organized in

New York City in 1850.9

Membership was limited to native-born

males who had no connection with

Catholicism. With the slogan

"Americans should rule

America," it advocated checking the surg-

ing political power of Catholics and the

foreign-born by an extension

of the residency period for

naturalization to as long as twenty-one

years. In 1853 the Order embarked on an

ambitious national expan-

sion program, and the following year its

leaders decided to enter poli-

tics as the independent American

party.10

In general the Order was stronger in the

East, but Ohio was one

western state where it wielded great

power. By the summer of 1854,

despite only a brief existence in the

state, the Know-Nothings consti-

tuted a factor to be reckoned with

politically, and they played a cru-

cial role in the People's party victory

that fall.11 In the three months

8. Ashley to Chase, January 21, 1855,

Chase Papers, LC; Ashtabula Sentinel, Janu-

ary 15, May 24, 1855; Chase to [Joseph

R. Williams?], January 12, 1855, Chase Papers,

LC.

9. For the origins of the Know-Nothings,

see Charles Deshler to R. M. Guilford,

January 20, 1855 (copy), Charles Deshler Papers,

Rutgers University; New York Her-

ald, December

20, 1854; New York Tribune, May 29, 1855; and Thomas R. Whitney, A

Defense of the American Policy (New York, 1856), 280-85.

10. For the Know-Nothings' appeal, see

Michael F. Holt, "The Politics of Impa-

tience: The Origins of Know

Nothingism," Journal of American History, 60 (Septem-

ber, 1973), 309-31.

11. New York Times, October 20,

1854; G. W. Lewis to Cyrus Carpenter, October 1,

1854, Cyrus Carpenter Papers, State

Historical Society of Iowa; Sidney D. Maxwell, Di-

ary, January 10, 1855, Cincinnati

Historical Society. Attributing the 1854 results to

"Anti-Nebraska, Know-Nothings, and

a general disgust with the powers that be," fu-

ture president Rutherford B. Hayes

concluded: "How people do hate Catholics, and

what a happiness it was to thousands to

have a chance to show it in what seemed a

lawful and patriotic manner." Hayes

to Sardis Birchard, October 13, 1854, Charles

Salmon P. Chase

9

following the October election, the

American organization more than

doubled its membership in the state. In

January, 1855, the Order's

national secretary reported that there

were 830 councils in the state,

and a month later reliable sources

placed its strength at 120,000 vot-

ers.12 Membership still had

not peaked. By June, according to the

official report of Thomas Spooner,

president of the Order in Ohio,

there were 1,195 councils in the state

with an aggregate membership

of 130,000.13

Chase was cognizant of the

Know-Nothings' contribution to the

opposition's 1854 triumph. He also

believed that a majority of the Or-

der's members were sincerely

antislavery, and thus he hoped that

the cooperation which the People's party

had brought about be-

tween the nativists and other

anti-Democratic groups would continue.

In the wake of the Order's spectacular

growth, Know-Nothing

leaders, in contrast, increasingly spoke

of nominating an independent

ticket in 1855. Without question, by the

spring of 1855 a majority of

the 1854 anti-Nebraska voters had joined

the American party. "I am

very, very sorry that the K.N. trouble

has come upon us," a worried

Chase told Oran Follett, the editor of

the Ohio State Journal. "But

for this the sky of the future would be

clear." In an editorial directed

to the Chase men, the Cleveland Express,

a Know-Nothing organ,

concisely summarized the situation in

the state: "Why, gentlemen,

you can't select enough prominent

'Republicans' in Ohio to act as

delegates to the [state] convention,

without having in it a majority of

Know Nothings."14

Because he naturally wished to be the

candidate of a united oppo-

sition party, the former Ohio Senator

tried to carve a middle course

between repudiating the Know-Nothings

and joining the nativist Or-

der. He was chagrined when the Ohio

Columbian, the Free Demo-

cratic organ edited by E. S. Hamlin,

launched an attack on the

Know-Nothings after the 1854 election.

Although he contributed

heavily to the paper's finances and

exercised considerable personal

influence over Hamlin, Chase did not

strictly control the Columbian.

Nevertheless, it was widely regarded

throughout the state as his

Richard Williams (ed.), Diary and

Letters of Rutherford B. Haves (Columbus, 5 vols.,

1922), v. 1, 470.

12. Ohio Statesman, March 8, 1855;

Ohio Columbian, June 12, 1855; Deshler to H.

Crane, January 15, 1855 (copy),

Deshler Papers. Hereafter, unless otherwise indicated,

citations to newspapers and manuscripts

are for the year 1855.

13. Spooner's report, dated June 3, is

given in the Cincinnati Commercial, June 8.

14. Chase to Follett, January 1,

"Follett Papers," 62; Cleveland Express, quoted in

Ohio Columbian, May 30.

10 OHIO HISTORY

personal organ, and therefore he was

anxious to disassociate himself

from its assaults on the Know-Nothings.

He tried to moderate its

course in order to promote harmony among

the opposition. In No-

vember he advised Hamlin not to say

anything against the nativist

Order: "Wait until it becomes

necessary & it may never become nec-

essary." Chase repeated this advice

several times during the follow-

ing weeks. "It seems to me you have

said enough agst the Kns, and

had better hold up," he wrote in

February. "My idea is fight no-

body who does not fight us." In

another letter, Chase endorsed

many of his correspondents' criticism of

the Columbian's repeated

denunciations of the Know-Nothings as

proslavery. He feared such

aspersions would weaken the influence of

antislavery men in the or-

ganization and "make the members of

the order less disposed than

they would be otherwise to cooperate

with outsiders on the Slavery

issue." Chase assured Follett that

the attacks on the Know-Nothings

by Hamlin and other associates did not

meet his approval. "My

opinion is that it is best to wait and

see, and not precipitate by cen-

sure in advance, a course which prudence

and conciliation may pre-

vent."15

In addition to urging Hamlin and others

to moderate their criti-

cism, Chase sought to devise a common

set of principles upon which

the two groups could unite. Noting that

the antislavery idea needed

to be kept "paramount," he

urged that "an earnest antislavery tone

should be maintained by our press &

that the fire [?] should be sus-

tained." Still, Chase was willing

to trim on nativism in order to pre-

serve the unity of the People's party.

"It would be better if you ad-

mitted that there was some ground for

the uprising of the people

against papal influences & organized

foreignism," he suggested to

Hamlin, "while you might condemn

the secret organization & indis-

criminate proscription on account of

origin or creed." He was particu-

larly anxious not to alienate the

foreign-born voters "who stood

shoulder to shoulder with us in the Anti

Nebraska struggle of last

fall."16 Chase

was not alone in seeking to conciliate the Know-

15. Chase to E. S. Hamlin, November 21,

1854, Private, February 9, January 22,

Chase to A. M. Gangewer, February 15,

Chase Papers, LC; Chase to Follett, January 1,

February 14, "Follett Papers,"

62, 64.

16. Chase to E. S. Hamlin, January 22, Chase

Papers, LC; Chase to Dr. John Paul,

December 27, 1854, Draft, Chase Papers,

Historical Society of Pennsylvania. In his let-

ter to Hamlin, Chase adopted the

transparent pose that he was merely relaying the

suggestions of friends. He was less

ingenuous in his letter to Dr. Paul, in which he as-

serted that in the activities of some

Catholics and foreigners "there has been some-

thing justly censurable & calculated

to provoke the hostility which has embodied it-

self in the Know Nothing

organization."

Salmon P. Chase

11

Nothings without endorsing proscription

of all immigrants. Senator

Benjamin F. Wade agreed that

"hostility to slavery" must be kept in

the political forefront, yet he told

William Schouler, the editor of the

Cincinnati Gazette, that

"every intelligent man knows full well that

our country has suffered much from the

too great influence of foreign-

ers, ignorant of our institutions &

that their power for evil ought to be

abridged . . "17

Not all pronounced antislavery men

shared Chase's willingness to

unite with the Know-Nothings. One of

Chase's correspondents, for

example, opposed "going into

partnership" with the Americans in

making nominations. The nativists could

support the ticket if they

wanted, "but let us have no

entangling alliances." Another Chase or-

ganizer regretted that the Know-Nothings

could not be met in an

open fight: "I think there should

eventually be no compromise with

them, until they abandon their

organization, and their bigoted

creed."18 The leading

voice against any union with the Know-

Nothings was Giddings' mouthpiece, the Ashtabula

Sentinel. "We

scorn the idea of a secret political

organization," read one editorial,

for it promoted "deception,"

"false dealing," "trickery and unfair-

ness." Terming nativism

"unjust, illiberal and un-American," the pa-

per announced, "We will never unite

with such a party, in any com-

pact whatever." It called for no

union at the fusion convention unless

the Know-Nothings abandoned their

organization and endorsed Re-

publican doctrines. A communication from

Giddings was equally

hard-nosed. Opposing any compromise, he

called for "a Republican

Convention, a Republican nomination,

without surrender, without

compromise." When Chase upbraided

Giddings for the tone of the

Sentinel, the Ohio congressman rejoined that it was imperative

that

they have a Republican convention that

did not recognize the exis-

tence of the Know-Nothings.19

Most Free-Soilers nevertheless rallied

behind Chase's candidacy.

By January 1, over six months before the

state convention, a number

17. Wade to Schouler, May 3,

Confidential, William Schouler Papers, Massachu-

setts Historical Society. Wade's brother

Edward, an even more zealous antislavery

man, though he criticized Know-Nothing

bigotry, embraced several nativist reforms,

including a church property law, a

literacy test for voting, and "requiring a real renun-

ciation of foreign allegiance." Edward Wade to Albert Riddle, January 18, Janes Col-

lection, Henry E. Huntington Library.

18. Aaron Pardee to Chase, May 17, W. H.

Nichol to Chase, July 7, Chase Papers,

LC; O. White to Oran Follett, May 3,

Chase Papers, HSP.

19. Ashtabula Sentinel, April 26,

May 10, 31, letter signed "G." [Giddings], May 17;

Giddings to Chase, May 1, Chase Papers, HSP. Also see

Giddings to Julian, May 30,

Giddings-Julian Papers.

12 OHIO HISTORY

of newspapers were actively promoting

his candidacy. The most

prominent were the Ohio Columbian and

the Toledo Blade. Gid-

dings, in contrast, initially criticized

the Chase boom; he argued that

there were a number of good men

available and did not want to see

the opposition splinter over the

question of men. By the end of Feb-

ruary, however, as Know-Nothing

hostility to Chase became mani-

fest, the veteran antislavery

congressman threw his support to the

former senator. Wade lent his influence

as well. Chase also had

strength among the Germans, whom he had

long courted and who

were frightened by nativism, and among

antislavery Whigs, particu-

larly on the Western Reserve. Backed by

this coalition, Chase was

by early spring the only serious

candidate of the antislavery forces.20

Other elements of the opposition,

however, were less than ecstatic

at the prospect of Chase heading the

anti-Democratic ticket. Almost

simultaneously with the beginning of the

Chase movement, a group

of opposition leaders promoted another

Free-Soiler, Jacob Brinker-

hoff, as a suitable alternative

candidate. A former Democratic con-

gressman, Brinkerhoff had played a

leading role in the original intro-

duction of the Wilmot Proviso. Whatever

the validity of his later

claim to have been the Proviso's real

author, he enjoyed a reputation

as a notable antislavery leader, and he

had been prominent in the

opposition to the repeal of the Missouri

Compromise.21

Although Brinkerhoff eventually became

popularly identified as

the Know-Nothing candidate, the initial

movement on his behalf be-

gan outside the Order. R. P. L. Baber,

an associate editor of the Ohio

State Journal, the old Whig organ, proposed the idea immediately

after the October 1854 election. He

secured an important ally in

Congressman-elect John Sherman, a

resident of Brinkerhoff's home-

town who, though not a member,

definitely sympathized with the

Order. Follett, while publicly neutral,

privately aided the Brinker-

hoff movement as well. Joseph Medill of

the Cleveland Leader also

extended support, though he was less

desirous of nominating

Brinkerhoff than he was of defeating

Chase, whose selection he be-

lieved would imperil the chances of

victory. Stressing the necessity of

cooperating with the Know-Nothings, he

warned Follett: "We must

20. Chase to [Joseph R. Williams?],

January 12, Chase Papers, LC; Giddings' corre-

spondence to Ashtabula Sentinel, February 1,

March 1; Bradford, "Background and

Formation of the Republican Party in Ohio," 144.

21. For Brinkerhoffs role in the

introduction of the Wilmot Proviso, see Eric Foner,

"The Wilmot Proviso

Revisited," Journal of American History, 56 (September, 1969),

262-65.

Salmon P. Chase

13

check the movement of the Chase clique

or they will get us into a

snarl."22

Despite such support, Brinkerhoffs

candidacy became closely

tied to Know-Nothingism. American

leaders actively pushed his can-

didacy within the Order, in part because

he was a member, and in

part because they recognized the

necessity that the candidate be

satisfactory to antislavery men. Early

in 1855, Congressman Lewis D.

Campbell, the most influential

Know-Nothing in the state, undertook

to marshall support for Brinkerhoff's

nomination, and a subsequent

secret meeting of Know-Nothing leaders

designated the former con-

gressman as the Order's choice.23 Thus,

long before a fusion conven-

tion had even been called, the struggle

for the gubernatorial nomina-

tion had narrowed to Chase and

Brinkerhoff.

The date of this convention became a

point of dispute between the

Chase men and the Know-Nothings. Fearful

of a separate Know-

Nothing nomination before the fusion

convention assembled, a num-

ber of Chase's supporters advocated that

the convention be held

early in the year. The Know-Nothings, on

the other hand, were anx-

ious to delay the convention as long as

possible. Campbell wanted it

held in August, which would give the

Order time to perfect its organ-

ization, recruit more members, and, if

it wanted, make separate nomi-

nations before the fusion meeting.24

Finally in May a majority of the

state committee appointed by the 1854

convention issued a call for a

Republican convention in Columbus on

July 13. The call was worded

to include all opposition elements. It

directed the "independent anti-

Nebraska voters of Ohio, who

participated in the glorious triumph of

last year, and such others as may

sympathize with them," to elect

delegates to a convention to nominate

candidates for governor and

the other state offices to be elected in

the fall.25 A few antislavery

men, who wanted a more exclusive

convention, were unhappy that

the Know-Nothings had been included in

the call, but its publica-

22. R. P. L. Baber to Sherman,

Confidential, October 16, 1854, May 5, June 28,

Sherman Papers; Ohio State Journal, May

10, 18; E. S. Hamlin to Chase, November 10,

1854, Chase Papers, HSP; Joseph Medill

to Follett, December 20, 1854, Confidential,

"Follett Papers," 77-78; J. H.

Coulter to Chase, May 27, Chase Papers, LC.

23. Campbell to Schouler, February 15,

Schouler Papers; Ohio Columbian, May 2,

9; Cincinnati Commercial, May 12.

24. Ashtabula Sentinel, January

18, 25; Chase to Follett, February 14, "Follett Pa-

pers," 65; Giddings to Chase, April

10, Chase Papers, HSP.

25. The call is in the Ohio State

Journal, May 28. It specified the ratio of representa-

tion for the counties and recommended

that delegates be elected in each county on

July 7. No doubt because some members of

the committee refused to sign the call,

only the committee chairman's (who was a

Know-Nothing) and the secretary's names

were affixed to the call.

14 OHIO HISTORY

tion signified the agreement of the

Free-Soilers, under Chase's lead,

to join the Know-Nothings in a fusion

convention.

Despite the appearance of this call,

neither side was unqualifiedly

committed to union. Although he agreed

to participate in this con-

vention, Giddings nonetheless asserted

that if the Know-Nothings

managed to control it, the antislavery

men should bolt. Other Free-

Soilers concurred in this strategy. One

of Chase's leading supporters

declared, "We had better have it

known informally to the Conven-

tion or the Members who compose it that

we will not abide its action

unless you are nominated."26 As

a guarantee that the convention

would act properly, several antislavery

men, including Ashley, urged

that a mass meeting also be called to

meet in Columbus on the same

day. If the fusion convention nominated

Chase, this mass meeting

could ratify his selection; if, on the

other hand, the Know-Nothings

controlled matters, then this meeting

could, in the words of one

Free-Soiler, "proceed at once to

an independent organization and ac-

tion." Ashley, who believed that a

mass meeting "can certainly do

no harm & may save us,"

actually preferred that it meet before July

13 and nominate Chase on the 1852

Free-Soil platform. This action

might "compell that Convention to

adopt our men and platform," he

commented, "and if not have our

friends either break up the Con-

vention or withdraw and Resolve to

sustain the Ticket" named by

the mass assembly.27

Several advocates of independent action

contended that a Repub-

lican ticket free of any Know-Nothing

taint would triumph in the fall.

Giddings, for example, argued that such

a move would ensure the

support of 30,000 foreign-born voters

who supported the anti-

Nebraska ticket the previous fall.

Others advanced the even more

far-fetched argument that the

Democratic nominee, William Medill,

who was not a strong Nebraska man,

would withdraw in Chase's fa-

vor if there were a separate

Know-Nothing ticket. The Sentinel pre-

dicted that less than half of the

members of the secret Order would

support a separate American ticket in

any event. Not misled by these

assessments, Chase knew that his best

chance for victory was as

head of a single opposition party and

so, while he was careful not to

pledge in advance to support the ticket

nominated on July 13, he

26. Letter signed "G."

[Giddings], Ashtabula Sentinel, May 17; Giddings to Chase,

May 1, J. H. Coulter to Chase, May 27,

Chase Papers, LC.

27. Ashley to Chase, May 29, June 16, P.

Bliss to Chase, June 6, Chase Papers, LC;

N. S. Townshend to Chase, June 9, Chase

Papers, HSP; Richard Mott to Giddings,

June 2, Joshua R. Giddings Papers, Ohio

Historical Society.

|

Salmon P. Chase 15 |

|

|

|

used his influence to block the plan of Ashley, Hamlin, and others to hold an antislavery convention prior to the Republican convention.28 Chase's support for cooperation with the Know-Nothings was more qualified than he acknowledged. To James Shepherd Pike, an associate editor of the New York Tribune, he specified certain condi- tions required for successful fusion: both sides had to be "fairly rep-

28. Ashtabula Sentinel, May 10, June 7; letter signed "G." [Giddings], Ashtabula Sentinel, May 17; J. H. Coulter to Chase, May 27, Ashley to Chase, May 29, Ralph Leete to Chase, June 18, Chase Papers, LC; Medina Gazette quoted in Ashtabula Sen- tinel, May 10; Toledo Blade, April 23, June 22. |

16 OHIO HISTORY

resented" on the ticket, the

platform had to oppose any more slave

states and slave territory, and the

ticket had to be "nominated by a

peoples Convention fairly

constituted." He was adamant that Know-

Nothing tenets not be made a test of

nomination; the bond of union

must be anti-Nebraska principles, not

nativism. Chase blithely an-

nounced that he was quite willing to

support Brinkerhoff-provided

that he strictly represented "pure

and simple . . . opposition to Slav-

ery extension & slavery

domination." If his triumph would be

viewed as the victory of an element

other than anti-Nebraska senti-

ment, then he could not support him,

Chase declared, secure in the

knowledge that these preconditions could

never be met.29 In es-

sence, Chase stipulated that any result

except his nomination would

be irrefutable evidence of unfair

dealing by the Know-Nothings, and

consequently the antislavery men would

not be bound to support the

ticket.

Chase's opponents perceived the

implications of these terms.

Brinkerhoff, for example, commented that

"the peculiar friends of

Mr. C. have about made up their minds to

'rule or ruin.'" Follett was

equally critical. He warned that the

position of the Free-Soilers, if

persisted in, ended all chance for

fusion, and he condemned the at-

titude of Chase's friends "that any

result contrary to their wishes

must be taken as the secret work

of the order: they object to secret

dictation, and fall into [the] mistake

of open dictation!" Angered by

the threat of the antislavery men to

bolt the convention if Chase were

not nominated, the exasperated Columbus

editor momentarily an-

nounced that he would no longer work for

fusion with "such imprac-

tical materials." The "course

of your friends is open," he repri-

manded Chase, "but it is not free

and fair."30

Chase supporters in turn denounced the

tactics of their opponents,

particularly the threatened nomination

of a Know-Nothing ticket

prior to the Republican convention,

which would end any chance for

a successful fusion. Chase alleged that

the Americans wanted "ex-

clusive selection of the ticket, leaving

to a peoples Convention no

function but that of ratification."

If the July 13 convention endorsed

a ticket already selected by the

Know-Nothings acting independent-

ly, the Republican party would have no

separate identity. With good

reason Chase feared that the Germans

would never support such a

29. Chase to James Shepherd Pike, March

22, James Shepherd Pike Papers, Uni-

versity of Maine; Chase to Campbell May 25, (copy),

June 2, Chase Papers, LC.

30. Brinkerhoff to Follett, May 21,

"Follett Papers," 75; Follett to Chase, May 2, Pri-

vate, Chase Papers, LC.

Salmon P. Chase

17

ticket even with the Republican label,

and a number of longtime po-

litical associates as well warned him

that they personally would never

swallow such a dose. One of Chase's

close advisers commented:

"The K.N.'s must not attempt

to forestal, or dictate to the rest of this

. . party. Such a move would be very

foolish, and fatal to their own

aims and objects."31

While Chase scotched plans for independent

action within the

Free-Soil ranks, he relied on Campbell

to prevent any similar move

by the Know-Nothings. The two men had

never been close personal-

ly. Chase's polished, unemotional, and

indirect approach contrasted

sharply with Campbell's blustering and

agitated manner; whereas

Chase sought to avoid confrontation,

Campbell's soaring vanity and

contentious temperament kept him

embroiled in never-ending feuds

and controversies.32 Both

realized, however, that at this juncture

each was in a position to render

valuable assistance to the other.

Since the fall of 1854, Campbell had

been running for Speaker of the

next House of Representatives, which

would assemble the coming

December. In this crisis Chase

skillfully exploited his fellow Ohio-

an's well-known national ambitions.

Subtly implying that Campbell's

assistance in promoting the Republican

movement in the state would

secure Free-Soil backing in the

Speakership contest, Chase urged

the nativist congressman to exert his

influence to prevent any separate

Know-Nothing nominations.33

Chase was particularly alarmed when word

leaked out that at a se-

cret meeting in the Cincinnati offices

of the Ohio & Mississippi Rail-

road, a group of Know-Nothing leaders

along with some outsiders

agreed on a ticket to be presented at

the July 13 convention. Late in

life Follett claimed that he, along with

Schouler of the Gazette and

George Benedict of the Cleveland Herald,

all of whom were actively

promoting union of the opposition,

attended this conference in an

unsuccessful attempt to prevent any

nominations. As part of the proc-

ess to select a state ticket, the

American State Executive Committee

had already instructed the local

councils to send their nominations

31. Chase to Pike, March 22, Pike

Papers; James T. Worthington to Chase, April 22,

W. H. Nichols to Chase, April 14, Chase

Papers, LC.

32. For Campbell's character, see the

Cincinnati Commercial, April 18, May 3; note

by Schouler, n.d., on the back of

Campbell to Schouler, July 6, 1852, Schouler Papers;

T. M. Tweed to Chase, October 25, Chase

Papers, LC. His career is sketched in

William E. Van Home, "Lewis D.

Campbell and the Know Nothings," Ohio History,

76 (Autumn, 1967), 202-21,

33. Chase to Campbell, May 29, June 2,

Chase to "Gentlemen," Draft, October 23,

Chase Papers, LC; Chase to Campbell,

November 8, Lewis D. Campbell Papers, Ohio

Historical Society.

18 OHIO HISTORY

for state candidates to the State

Council, which was to meet in Cleve-

land at the beginning of June.

Apparently one purpose in naming a

ticket at the Cincinnati meeting was to

influence the balloting in the

lodges, for nativist leaders

immediately transmitted this slate to local

officers. In publicizing the action of

the Executive Committee, the

Cleveland Leader predicted that

there would be "a grand smash-up

at Columbus" if the Know-Nothings

persisted in their schemes.34

Attention focused on the upcoming State

Council. One of Camp-

bell's correspondents, with an eye to

promoting harmony, pro-

nounced the call for the Cleveland

meeting "a great mistake" and

urged that it be revoked. In a rather

acrimonious correspondence,

Chase pressed Campbell hard to block

any nominations at Cleve-

land, and the latter finally agreed to

attend the State Council meeting

and work against any independent

action.35 After a long debate, the

State Council made no nominations and

resolved to go into the July

13 convention. The Know-Nothings did

not commit themselves to

support Chase, however, and the

Cincinnati Commercial contended

prior to the State Council meeting that

although no nominations

would be made, the secret ticket

selected earlier in Cincinnati would

be pushed by nativist delegates at the

July convention. The State

Council agreed to reassemble in August,

after the Republican ticket

had been named.36

The State Council also adopted a

platform. The Ohio American

platform contained several cardinal

nativist doctrines. It called for a

twenty-one-year residency requirement

for naturalization, the aboli-

tion of foreign military companies,

lauded the public school system,

and denounced all attempts to exclude

the Bible from the public

schools. At the same time it endorsed

"unlimited Freedom of Reli-

gion disconnected with politics-Hostility to ecclesiastical

influences

upon the affairs of Government,"

and equal rights for all foreign-born

who were thoroughly Americanized and

owed no temporal alle-

giance because of their religion to an

authority higher than the Con-

stitution, an obvious reference to

Catholicism. In a circular to the lo-

34. Chase to Follett, May 4,

"Follett Papers," 74; Follett, "The Coalition of 1855,"

Alfred E. Lee, History of the City of Columbus (New

York, 2 vols., 1892), v. 2, 431-33;

Joseph Medill to Follett, April 18,

"Follett Papers," 71; Cleveland Leader, quoted in

Cincinnati Commercial, May 12.

The ticket named by the Cincinnati meeting is given in

the Cincinnati Commercial, May

12.

35. B. Stanton to Campbell, May 14,

Campbell Papers; Chase to Campbell, May 29,

June 2, Campbell to Chase, May 28, 31,

June 15, Chase Papers, LC.

36. Campbell to Schouler, June 26,

(Private), Schouler Papers; letter signed "AN

AMERICAN," Ohio State Journal, October

5; William Gibson to Samuel Galloway,

April 23, Samuel Galloway Papers, Ohio

Historical Society.

|

Salmon P. Chase 19 |

|

|

|

cal councils before the State Council met, Spooner endorsed the propriety of allowing foreign-born Protestants to join the society. "It is not men of Foreign birth that we war against," the president of the Ohio Order claimed. "Our arms are, and should only be, directed against Foreignism and Romanism-those who should subvert our Institutions, and place our country under the yoke of Rome." The State Council did not adopt this change, although it urged its dele- gates to the National Council to work for this reform. Still, it was ap- parent that anti-Catholicism constituted the main thrust of the Or- der's appeal. The American organization also partially dropped its |

20 OHIO HISTORY

secrecy and substituted an honorary

obligation for its system of

oaths. One plank dealt with the slavery

issue. It declared slavery a

local and not a national institution,

opposed its extension into any ter-

ritory or the admission of any more

slave states, and demanded the

"immediate redress" of the

great wrongs of the repeal of the Missou-

ri Compromise and the election frauds in

Kansas. Despite the ambi-

guity of this last point, the

Know-Nothing platform endorsed the

propositions that Chase specified

earlier in discussing the grounds

for fusion.37

The Ohio State Journal was

delighted with the Know-Nothings'

action, which it hoped would end

"all jealousy and distrust" in the

opposition ranks. "We see no

barrier to a full and cordial union of all

the true anti-Nebraska friends of Reform

in Ohio. The skies are

bright." Giddings was likewise

optimistic following the Cleveland

meeting. In predicting that Chase would

be nominated, he declared,

"I think the K Ns will give us no

more trouble in this State."38

The Cleveland meeting was the critical

turning point in the drive to

unite the opposition in Ohio in a new

party. For several months be-

forehand, each side had attempted to

intimidate the other. Gid-

dings defended the defiant tone of the Sentinel

on the grounds that

if the Know-Nothings felt that they were

strong, they would make

separate nominations. One purpose of the

talk among the Chase fac-

tion of a bolt and a new convention was

to coerce the Know-Nothings

into adopting an acceptable course. This

strategy succeeded bril-

liantly. The Know-Nothings suffered a

failure of nerve. The question

remains why the American party's

leaders, who had been confident

and even arrogant earlier in the year,

abandoned their plan to dictate

the fusion ticket.39

Several factors were critical in the

Know-Nothings' decision at

Cleveland. Undoubtedly important was the

influence of Campbell,

whose personal aspirations led him to

oppose separate nominations.

He probably received valuable aid in his

efforts from Spooner, who,

though not a supporter of Chase, was

personally friendly with the

Free-Soil leader and was overly

susceptible to flattery. Before long,

37. The platform is given in the Ohio

State Journal, June 7, and the Cincinnati Com-

mercial, June 8. For Spooner's address before the State Council,

see the Commercial,

June 8.

38. Ohio State Journal, June 7; Giddings

to John Gorham Palfrey, June 29, John

Gorham Palfrey Papers, Harvard

University.

39. Giddings to Chase, April 10, Chase

Papers, HSP. Another Chase organizer de-

clared, "The course of ... many

Free Soilers for the last few weeks has intimidated

the K. Ns." J. H. Coulter to Chase,

May 27, Chase Papers, LC. Also see Galloway to

Campbell, June 23, Private, Campbell

Papers.

Salmon P. Chase

21

Spooner would become one of Chase's most

faithful adherents. As a

nativist and antislavery man, Spooner

anxiously wanted a united op-

position party established. Before the

State Council met, he warned

his fellow nativists that a split in the

anti-Democratic forces assured a

Democratic victory in the fall.40

But probably the most critical reason

for the change in attitude

among the Know-Nothings was the outcome

of the Cincinnati munici-

pal election in April. With

anti-Catholic feeling rampant in that com-

munity, the Know-Nothings easily

dominated the anti-Democratic

opposition in the Queen City. Confident

of their power, they nomi-

nated a disreputable ticket, headed by

James Taylor, the rabble-

rousing editor of the Cincinnati Times,

for the city election. Taylor's

nomination not only disgusted

conservatives in the city, his strident

and indiscriminate attacks on foreign

influence alienated Protestant

Germans who had cast opposition ballots

in 1854.41 The municipal

campaign, which was one of the most

bitter in the city's history, pit-

ted the foreign-born against militant

nativists and greatly exacer-

bated existing tensions. By election

day, feelings were at a fever

pitch. With imported nativist toughs

roaming the city, fighting even-

tually broke out in the German wards

between immigrants and

Know-Nothings. The violence continued

sporadically for three days,

and a Know-Nothing attempt the night

after the election to storm the

German section of the city left several

members of the mob dead. In

addition, Know-Nothings destroyed the

ballots in two heavily Ger-

man wards to prevent their being

tallied. With both sides claiming

victory and issuing threats, election

officials finally declared the

Democratic mayoral candidate victorious.42

Republican editor Jo-

seph Medill, long an advocate of using

the Catholic issue to gain the

support of Protestant immigrants, looked

on with dismay as Germans

were driven back into the arms of the

Democrats. He bluntly charac-

40. Letter signed "G."

[Giddings], Ashtabula Sentinel, June 21; Follett, "The Coali-

tion of 1855," 431. Medill claimed

that making "such a weak brother as Thos Spooner

at the head of the K.N. order is a

horrible political blunder." Joseph Medill to

Follett, April 18, Oran Follett Papers,

Cincinnati Historical Society.

41. Hayes to Sardis Birchard, April 8, Diary

and Letters of Rutherford B. Hayes, v.

1, 481-82; Gazette and Commercial,

quoted in the Cincinnati Enquirer, March 24;

Cincinnati Enquirer, March 27,

28, 29, 31; letters signed "Foreign Protestant" and

"German Protestant," in the Enquirer,

March 29, 31.

42. The riot is fully covered in the

Cincinnati Gazette, Commercial, and Enquirer,

April 3-6. Also see William Baughin,

"Bullets and Ballots: The Election Day Riots of

1855," Bulletin of the

Historical and Philosophical Society of Ohio, 21 (October, 1963),

267-73.

22 OHIO HISTORY

terized the Cincinnati Know-Nothing

leaders as "knaves and ass-

es."43

The rioting was an even more serious

blow to the state American

party than Taylor's defeat. It made a

mockery of the party's image as

a reform party and discredited it with

a sizable segment of the pub-

lic. Campbell tried to minimize the

importance of the Cincinnati re-

sult, but its damage was obvious.

Know-Nothing leaders' confidence

in their ability to carry the state

without antislavery allies suddenly

evaporated. Giddings' informants

reported that the Order's state

leaders viewed the Cincinnati election

as a disaster to the nativist

cause, and that in its wake they had

abandoned the idea of making

separate nominations.44

Hard on the heels of the Cleveland

meeting came the National

Council in Philadelphia. When the

Council took up the question of a

national platform, an acrimonious

debate ensued between Southern-

ers and a group of northern antislavery

men. After eight days of futile

wrangling, the delegates adopted a

southern-inspired statement

which upheld the Kansas-Nebraska Act. A

majority of northern del-

egates, including a unanimous Ohio

delegation, voted against the

slavery plank. The next morning, these

northern delegates approved

an address condemning the action of the

National Council. Every

Ohio delegate signed the protest. Some

of those present openly

called for the formation of a new

party. In accord with this sentiment,

one of the seceding Ohio Americans sent

a telegram to an anti-

Democratic convention then assembled in

Cleveland which closed:

"May God eternally d- -n slavery

and Doughfaceism."45

The national schism further sapped the

Ohio Know-Nothings'

confidence, while simultaneously it

engendered a more favorable

attitude toward reaching agreement with

the antislavery forces.

Chase's optimism soared in the

aftermath of the Cleveland and

Philadelphia meetings. He told Pike

that "the political atmosphere

has cleared somewhat," and went on

to predict that Know-

Nothingism in Ohio would

"gracefully give itself up to die." Believ-

ing that victory was within his grasp,

the former Senator adopted a

conciliatory tone toward the

Know-Nothings. Most members were

43. Joseph Medill to Follett, April 18,

Follett Papers.

44. Campbell to Isaac Strohm, April 21,

Isaac Strohm Papers, Ohio Historical Socie-

ty; letter signed "G."

[Giddings], Ashtabula Sentinel, June 21; Ashtabula Sentinel,

June 7.

45. For the proceedings of the National

Council, see Samuel Bowles' reports in the

New York Tribune, June 6-16, and

his account published in the same paper, October

31.

Salmon P. Chase 23

"honest men . . . sincerely opposed

to slavery," he asserted, who

"adhere but slightly to their

order," especially since the adoption of

the Philadelphia platform. Chase was

certain that the platform of the

July 13 convention would not

"contain a squint towards Knism." By

the end of June, he predicted to James

Grimes that he would be

elected by a majority of at least

20,000.46

Nevertheless, the results of the

election of delegates in the first

week of July disquieted the

Free-Soilers. In spite of all the difficulties

the American party had recently

experienced, it displayed remarka-

ble strength in the voting for county

delegates. When the July 13 con-

vention assembled in Columbus, all sides

agreed that a majority of

the delegates were Know-Nothings.47

Any triumph by Chase and

the antislavery forces could be achieved

only with nativist votes.

Although the Free-Soilers did not

control a majority of the dele-

gates, the Chase forces had several

advantages. One was their un-

shakable commitment to Chase's

candidacy. Led by Giddings, anti-

slavery men argued that Chase's

nomination would make an "issue of

Slavery and freedom more distinctly the

question" in the upcoming

election than would any other choice. In

their eyes, Chase's selec-

tion would assure that antislavery was

the party's paramount princi-

ple. They refused to consider

suggestions that Chase and Brinker-

hoff both yield to another individual.

The Know-Nothings' resolve,

on the other hand, was weakened by the

defection of some of the

northern delegates to Chase and by the

eagerness of their leaders,

particularly Spooner and Campbell, to

promote harmony in the con-

vention.48

The composition of the Cincinnati

delegation also gave Chase's

prospects an unexpected boost.

Politicians were especially sensitive

to the situation in Hamilton County, the

state's most heavily popu-

lated county. The opposition was badly

factionalized in the county,

however, as divisions between the

Know-Nothings and Whigs on

the one hand, and Germans and old

Liberty party men on the other,

threatened to send rival delegations to

Columbus. After what Ruth-

erford B. Hayes described as some

"very squally times," negotia-

46. Chase to Pike, June 20, Pike Papers;

Chase to Grimes, June 27, Chase to [N.S.

Townshend?], June 21, Chase Papers, HSP;

C. K. Watson to Chase, June 25, Chase

Papers, LC.

47. Ohio State Journal, July 13,

14; R. B. Pullan, Origins of the Republican Party,

Ohio Historical Society; letter signed

"AN AMERICAN," Ohio State Journal, Octo-

ber 5; Address of Thomas Spooner, July

23, Cincinnati Commercial, July 24.

48. Ashtabula Sentinel, April 19;

Campbell to Schouler, May 22 (Strictly Confiden-

tial), Schouler Papers; Follett,

"The Coalition of 1855," 432-33; Spooner to Editor of

the Cincinnati Times, quoted in Ohio

State Journal, July 12.

24 OHIO HISTORY

tions among the various factions led to

acceptance of a single delega-

tion which represented a wide variety

of political viewpoints yet

was largely composed of moderates.

Chase had disproportionate

strength among these delegates, as

supporters of two local candidates

who were seeking nominations for lesser

state offices agreed to vote

for Chase in exchange for support in

these other races.49

The greatest advantage of the Chase

forces at Columbus, however,

was the determination of his more ultra

supporters to bolt if their fa-

vorite were rejected. To reinforce this

threat, the old Independent

Democrat State Central Committee, which

had been moribund since

1853, issued a call for a mass

convention on July 13 to ratify the nomi-

nations or take appropriate action. On

the day of the fusion Republi-

can convention, perhaps as many as 400

outsiders were present, ready

to give Chase an independent nomination

if he failed to receive the

Republican designation.50 Opposition

leaders, aware that Chase and

his followers had bolted parties

several times in the past, knew that

this was no idle threat.

As the date of the convention neared,

Columbus overflowed with

visitors. Giddings journeyed to the

capital several days early for con-

sultations, and Chase was also present

beforehand. In hotel rooms,

parlors, and on the streets men

exchanged opinions about the proba-

ble course of the convention. One

moment Chase's stock seemed up,

the next moment down. The Know-Nothing

delegates caucused sep-

arately Thursday night, but failed to

reach any agreement; those

from the southern counties, in

particular, voiced a strong desire that

Chase be defeated. By the time the

convention assembled, excite-

ment was intense.51

On Friday the thirteenth, at 10:30 in

the morning, the first Ohio

Republican state convention convened in

the Town Street Methodist

Church. The morning session was devoted

to the appointment of

49. Hayes to William H. Gibson, June 18,

23, 25 (copies), Hayes to Lucy Webb

Hayes, June 24, Rutherford B. Hayes

Papers, Hayes Memorial Library; Pullan, Origins

of the Republican Party; Chase to [?], June 23, Salmon P. Chase Papers,

Cincinnati His-

torical Society. Because Chase was a

resident of Cincinnati, overwhelming opposition

to his nomination among the Hamilton

County delegates would have hurt his chances.

50. Ashtabula Sentinel, June 28,

July 12; Giddings to Chase, May 1, Chase Papers,

HSP; R. P. L. Baber to Sherman, June 28,

Sherman Papers. Chase was secretly in-

volved in preparing plans for

independent action if the July 13 convention did not nom-

inate him. See J. H. Coulter to Chase,

June 1, Chase Papers, LC. The Ohio State Jour-

nal, June 29, censured this action by the antislavery

element as "calculated to repel

instead of inspiring confidence."

51. See Giddings' history in the Ashtabula

Sentinel, July 19, and the account of the

Cincinnati Commercial's reporter

(probably Murat Halstead), July 14. A number of

Know-Nothing delegates, especially from

the northern counties, were for Chase.

Salmon P. Chase

25

committees and listening to speeches.52

Behind the scenes, howev-

er, party managers frantically labored

to preserve the fragile spirit of

goodwill which existed on the convention

floor. Follett, in particular,

sought an acceptable compromise. Prior

to the convention, the Ohio

State Journal sounded the theme of "union, harmony, every thing

for the cause." Follett had been

lukewarm toward Chase's candida-

cy, but he realized that the

Free-Soilers were unbending. Believing

that Chase's rejection would precipitate

the nomination of a third

ticket and thus rupture the

anti-Democratic coalition and ensure de-

feat, the Columbus editor urged Brinkerhoff

to withdraw from the

gubernatorial contest and accept instead

the nomination for Supreme

Court judge. Several weeks earlier, the

idea of running for the judge-

ship had been broached to Chase, but the

antislavery leader had

flatly rejected the proposition.53 An

earlier attempt to get Brinkerhoff

to retire had also failed, but now, with

the battle at hand, he agreed

to Follett's proposal, declaring that he

was not rich enough to be

governor and that the judgeship was more

in line with his talents.

How sincere Brinkerhoff was in this

explanation is unclear, but he

probably recognized that his position

was untenable.54 A week

earlier, Michigan Governor Kinsley

Bingham concluded after an in-

terview that the former congressman expected

to be defeated at the

Columbus convention.55

Brinkerhoffs acceptance of Follett's

offer climaxed the sharp

struggle between the Americans and the

Free-Soilers for control of

the Republican party. With this

stumbling block eliminated, the pro-

ceedings were remarkably harmonious. The

Committee on Resolu-

tions reported a platform that opposed

the further extension of slav-

ery, came out against the admission of

any new slave states, and

condemned the violence in Kansas.

Another plank made a vague ref-

erence to states' rights and a section

on state issues called for re-

trenchment, a just taxation system, and

the election of legislators

from single districts. The platform

passed over nativism in complete

silence. Giddings was the only committee

member to criticize the res-

olutions. He labeled them "milk for

babes," but somewhat incon-

52. The convention proceedings are in

the Ohio State Journal, July 13, 14. Also see

the accounts cited in the previous note.

53. Ohio State Journal, July 12;

Edward Wade to Chase, April 14, Chase Papers,

HSP; James A. Briggs to Chase, May 5,

Pike Papers; letter from Campbell, dated Octo-

ber 1, in the Ohio State Journal, October

2.

54. C. K. Watson to Chase, June 25,

Chase Papers, LC; Follett, "The Coalition of

1855," 431-33; Brinkerhoff, Recollections

of a Lifetime, 92.

55. Bingham to Chase, July 7, Chase

Papers, LC.

26 OHIO HISTORY

gruously admitted that they might be

sufficient and called for their

adoption.56 Campbell spoke in

their favor, and the delegates unani-

mously approved them.

Once the platform had been adopted, the

anti-Chase forces made

one last attempt to prevent his

nomination by proposing that both

Chase and Brinkerhoff be withdrawn.

Chase's supporters shouted

their disapproval, and some threatened

to retire from the hall. Final-

ly the delegates laid the motion on the

table. At this point Campbell

withdrew Brinkerhoffs name as per

arrangement, and Chase was

nominated with 225 votes to 144 for two

last-minute stand-in candi-

dates. In a speech to the delegates

following his nomination, Chase

declared that "there is nothing

before the people but the vital ques-

tion of freedom versus slavery.

..." Know-Nothings received all of

the eight remaining positions on the

state ticket. Most prominent of

these nominees were Brinkerhoff, who was

unanimously selected for

Supreme Court judge, and Thomas Ford,

whose widely publicized

speech at the recent Philadelphia

convention in opposition to the ma-

jority platform helped him win the

nomination for lieutenant gover-

nor. When the nominations were

completed, Spooner urged support

for the entire ticket, and the

convention adjourned. Afterwards

Chase praised his fellow nominees, but

more perceptive was the

comment of one observer that other than

Chase the ticket was a

group of mediocrities and "very

weak."57

Predictably, reaction to the outcome of

the convention varied. The

Ashtabula Sentinel admitted that "the platform might have been

more strongly worded for our

taste," but it pronounced Chase's nom-

ination as "itself a platform that

will not be mistaken by the South."

Chase, too, professed pleasure and

minimized the importance that all

of his running mates were nativists.58

Moderates and old-line Whigs,

56. Giddings wanted stronger resolutions

condemning Pierce for the situation in

Kansas, presumably similar to the

resolutions he drafted which were adopted by a

Republican meeting in Ashtabula County.

Those resolutions declared that, if necessa-

ry, force should be used to defend the

free state men in Kansas, condemned Pierce's

treasonable failure to use the army to

provide such protection, and called on the free

states to protect Kansas emigrants. Ashtabula

Sentinel, June 14.

57. Chase to Kinsley S. Bingham, October

19 (copy), Chase Papers, HSP; William

B. Fairchild to Isaac Strohm, October

12, Isaac Strohm Papers, Cincinnati Historical

Society. One exception to this analysis

might be Brinkerhoff, who had political ability

though his legal attainments were modest.

58. Ashtabula Sentinel, July 19; Chase to Kinsley S. Bingham, October 19

(copy),

Chase Papers, HSP. Favorable comments in

the Ohio press on Chase's nomination are

given in the Ashtabula Sentinel, August

2. The conservative Cleveland Herald hesi-

tated for some time before endorsing

Chase. See Maizlish, Triumph of Sectionalism,

217.

Salmon P. Chase

27

on the other hand, were sorely

disappointed, for Chase was, in the

words of one, "an awfully bitter

pill." Admitting that it had hoped

to avert Chase's selection, the

Cincinnati Gazette frankly com-

mented, "Few of our public men

could have so many bitter preju-

dices to contend with."59

Nor were die-hard

Know-Nothings

pleased with the results. After the

convention adjourned, the Execu-

tive Council met in a room above the

office of the Ohio State Journal

until six in the morning considering a

motion to expel Spooner for not

resisting Chase's selection more

vigorously. The American president

claimed that he loyally supported

Brinkerhoff, but others accused

him of double-dealing. In the end, the

motion lost and Spooner, now

solidly in Chase's camp, remained the

president of the Order in

Ohio.60

Historians have traditionally cited

Chase's nomination as a great

victory over nativism.61 In one sense,

of course, it was. Chase was not

a member of the Order, and the

Know-Nothings had devoted con-

siderable energy during the past months

in a vain effort to prevent his

nomination. But the results of the

convention hardly represented an

unbroken defeat for the Americans. If

the Republican platform con-

tained no nativist planks, it raised

not even a whisper of condemna-

tion of the Know-Nothings either, and

the demands of German

leaders for an endorsement of the

existing naturalization laws were

completely ignored. Moreover, the

Republican and American state

platforms exhibited no significant

differences on the slavery issue. In-

deed, the most radical proposition in

the Republican platform-

opposition to the admission of any more

slave states-had previously

been endorsed by the American party in

Ohio. Nor did the call for

the repeal of the Fugitive Slave Law,

long a key issue among Free

Soilers, find a place in the Republican

platform.62 In addition, the

convention paid no heed to the proposal

of some anti-Know-Nothing

leaders to place a foreigner on the

ticket, while the Americans gar-

59. William B. Fairchild to Isaac

Strohm, September 6, Strohm Papers, CinHS;

Cincinnati Gazette, July 14.

60. Pullan, Origins of the Republican

Party; Circular of Thomas Spooner, July 23, in

Ohio State Journal, July 25.

61. Eugene H. Roseboom, "Salmon P.

Chase and the Know Nothings," Mississippi

Valley Historical Review, 25 (December, 1938), 349-50. This idea is also implicit

in

Maizlish's analysis, though he views

nativism as ultimately untenable in any event be-

cause of America's liberal tradition. Triumph

of Sectionalism, 214-17.

62. The doctrine of barring any more

slave states might be considered radical, al-

though it enjoyed considerable support

in the North and was becoming standard Re-

publican dogma in many states. The

address of the bolters at Philadelphia did not en-

dorse this principle, but the Ohio

American platform did.

28 OHIO HISTORY

nered eight out of nine nominations,

certainly a significant accom-

plishment.63 If Chase could

go before the electorate unhindered by

a nativist platform, he also was running

on a preponderately Know-

Nothing ticket. As the extensive

nativist participation at Columbus

dramatized, the Republican party in Ohio

rested on a substantial

Know-Nothing foundation.

Much the more numerous faction in the

new party, the Know-

Nothings were confident after the

convention that they would domi-

nate the Republican party. Time

revealed, however, how serious was

their miscalculation. Support for Chase

and the Republican platform

made it impossible for the Know-Nothings

to maintain their distinc-

tive political identity. At its August

meeting the State Council freed

individual members to decide how to

vote; with this decision it was

inevitable that most nativists would be

absorbed into the Republi-

can ranks.64 The intimidation tactics of

the Chase forces, who were

willing to see the Democrats triumph

rather than tolerate Know-

Nothing control of the Republican party,

reaped handsome divi-

dends. Failure to defy the Free-Soilers

doomed the American party

in Ohio to a rapid death. In the final

analysis, the Know-Nothing

leaders sacrificed the party's future

for entirely modest immediate

gains. Their ineptness contrasted

sharply with the brilliance of the

Chase managers, who, by a dazzling

mixture of conciliation and in-

timidation, forced the nativist majority

to abandon their organization

and accept the nomination of one of the

least popular politicians in the

state.

Not all conservatives, either inside or

outside the American Order,

were willing to acquiesce in Chase's

nomination. Discontent was espe-

cially strong in Cincinnati. The

frequently heard prediction before

the convention that Chase's selection

would produce a third ticket

was soon fulfilled. Anti-Chase

dissidents made overtures to J. Scott

Harrison, the Whig-Know-Nothing

congressman from Cincinnati, but

he had no interest in being a

third-party candidate; he contended

that this would only reelect Governor

Medill, the Democratic nomi-

nee. Eventually a small convention of

dissatisfied Whigs and Ameri-

cans nominated former Governor Allen

Trimble, who was over seven-

ty and obviously could not actively run.

The participants approved a

platform that denounced sectional

parties, called for restoration of

63. Letter signed, "JUSTICE," Ashtabula

Sentinel, May 10; Ashley to Chase, May

29, Chase Papers, LC; Richard Mott to

Giddings, June 2, Giddings Papers.

64. The proceedings of the State Council

are given in the Ohio State Journal, August

9.

Salmon P. Chase

29

the Missouri Compromise, upheld

unspecified American principles,

and endorsed reform of the state's

banking and tax systems. Al-

though the meeting designated itself

the American party in Ohio, in

truth it represented only a small

fraction of the Know-Nothings, and

furthermore many present were not even

affiliated with the Order. In

fact, Trimble himself had never been a

member of the Order.65 That

the intent of this group was solely to

defeat Chase was transparent as

the convention made no other

nominations. Thus, of the Republican

nominees only Chase faced a third-party

challenge. Gleeful Demo-

crats secretly funded the Trimble campaign.66

From the start Chase was the central

issue of the campaign. Sens-

ing Chase's vulnerability, Democrats

concentrated on his alleged

abolitionism and on nativist influence

in the Republican party. The

Republican standard-bearer found himself

damned from both

sides: Germans denounced his

association with Know-Nothings on

the state ticket, while ardent

nativists refused to support him be-

cause of his tempered opposition to

Know-Nothingism. With Trimble

now in the field and the charge that he

was a Know-Nothing widely

circulated among Germans, the contest

proved much more difficult

than Chase had originally anticipated.67

The center of the great dis-

affection against Chase was Cincinnati.

Here conservative business-

men fearful of Chase's radicalism,

Americans angry over what they

believed to be the sellout of the Order

in Columbus, and old-line

Whigs still indignant about the 1849

senatorial election unleashed

their hostility on the Republican

nominee.68 Assailed from all direc-

65. William B. Thrall to Strohm, July 8,

Strohm Papers, CinHS; Ohio State Journal,

August 9; J. Scott Harrison to Benjamin

Harrison, July 28, August 2, Benjamin Harrison

Papers, Library of Congress. For Whig

opposition to Chase, see William Johnson to A.

Banning Norton and others, August 18

(copy), Abraham Lincoln Papers, Library of

Congress; Ohio State Journal, quoted

in Ashtabula Sentinel, August 2; T. G. Jones to

Ewing, July 28, R. P. L. Baber to Ewing,

August 16, Thomas Ewing Family Papers, Li-

brary of Congress; letter signed

"FEDERALIST," Cincinnati Commercial, July 27.

66. Newton Schleick to William Medill,

August 14, William Medill Papers, Library

of Congress; David Chambers to Allen

Trimble, September 26, Allen Trimble Papers,

Western Reserve Historical Society; Ashtabula

Sentinel, August 9; Ohio State Journal,

October 1. At the beginning of the year

a Democrat told Medill that things looked

bleak in the state, and "the only

hope we have, is in the bust up and division of the

incongruous mass which was united

against us last election." Matthews Martin to

Medill, January 10, William Medill

Papers.

67. Follett to Chase, September 9, Chase

Papers, LC; Herman Kreismann to Sum-

ner, September 18, Sumner Papers.

Republican strategists felt it necessary to publish a

letter from Chase declaring that he was

not a Know-Nothing. In this letter Chase also

denied that his fellow Republican

nominees were hostile to the foreign-born. See

Chase to Homer Goodwin, August 24,

Cincinnati Commercial, September 12.

68. Free Soilers held the balance of

power in the 1849 state legislature. After a

30 OHIO HISTORY

tions, Chase took to the stump and

waged a strenuous campaign,

delivering 57 major addresses in 49

counties. Although his lead-

ing theme was always Kansas, in

Cincinnati and other conservative

strongholds he was also careful to

identify himself with preservation

of the Union. He received loyal support

from Campbell, Ford,

Spooner, and other Know-Nothing

leaders. Campbell, in particular,

threw himself into the contest with

unusual vigor and labored to

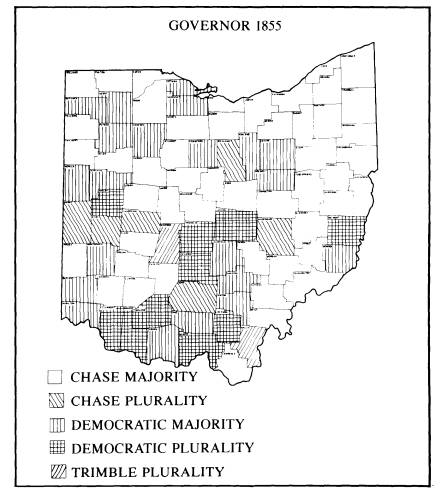

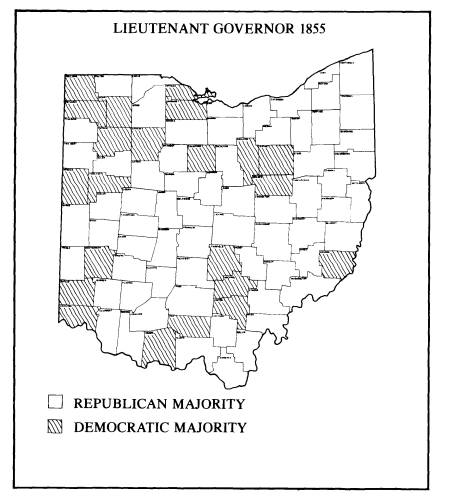

keep the Know-Nothings and former Whigs