Ohio History Journal

CINCINNATI AS A FRONTIER PUBLISHING

AND BOOK TRADE CENTER

1796-1830

by WALTER SUTTON

Department of English, University of

Rochester

Cincinnati was a frontier village with

one newspaper and a

population of 500 when the first book

published in the territory

lying north and west of the Ohio River

came from the press of

William Maxwell in 1796. The log-cabin

settlement on a north

bend of the Ohio River was only six

years old. Six more years

were to pass before it would be

incorporated as a town, and seven

before Ohio would be admitted to the

Union as the seventeenth

state. From the time of its founding

through the first decade of

the nineteenth century, Cincinnati had

neither the facilities nor

the market for any extensive publishing

activities although it was

a fast-growing port on the country's

main channel of westward

and southward migration. The steamboat,

which was to perform

miracles in the rapid settlement of the

new lands, had not yet made

its appearance on the western rivers.

Freight and pioneering set-

tlers were carried down the Ohio and

Mississippi in arks, pirogues,

keelboats, flatboats, and rafts. These

craft, particularly the flat-

boats and keelboats manned by the

half-horse and half-alligator

compeers of Mike Fink, carried an

impressive amount of cargo

down the rivers, even in very early

years. In 1798 the boatmen

of the Ohio River alone shipped nearly a

million dollars' worth

of goods down the Mississippi, and by

1807 almost 2,000 flatboats

and keelboats from the Ohio River were

arriving in New Orleans

annually. In that year they carried

cargoes valued at more than

five million dollars.1

1 C. H. Ambler, History of Transportation in the Ohio Valley (Glendale,

Cali-

fornia, 1932), 72.

117

118

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

The beginning of the second decade of

the century saw two

developments of great importance to the

growth of the western

book trade. By 1811, two paper mills were in operation in the

Miami country, and in that year also the

steamboat made its first

appearance on the Ohio and Mississippi

rivers. The two mills.

(the first of which had been built in

the summer of 18102) were

on the Little Miami River not far from

Cincinnati and provided

a greatly-needed local supply of paper

for the printing presses of

the fast-growing town, which by this

time had a population of

about 2,500. Before the Miami mills were

put into operation,

all paper used had to be imported

from the East or from Ken-

tucky, which produced little more than

enough to supply her own

needs.

Of far more significance to the

development of trade in gen-

eral was the debut of the steamboat,

which from 1820 until the

Civil War was the dominant factor in the

industrial life of the

West. Although practical steam

navigation of the rivers was not

assured until after Captain Shreve had

launched the George Wash-

ington in 1816, the influence of steam power upon the develop-

ment of the West was determined when

Nicholas Roosevelt suc-

cessfully brought the New Orleans down

the Ohio and Mississippi

from Pittsburgh to New Orleans at the

end of 1811. The steam-

boat was to settle and supply the new

states and territories of the

Ohio and Mississippi valleys. The great

numbers of new western

Americans were to require among other

goods an ever-increasing

supply of reading material which

Cincinnati, because of her stra-

tegic location, could supply more easily

than the remote East.

Steam power also, utilized in printing

offices and paper mills, was

to make it possible for the new

industrial center of the Ohio Valley

to supply the growing market of the West

with books in un-

dreamed-of quantities. Large-scale

publishing is another story,

2 C. M. Thomas, "Contrasts in

150 Years of Publishing in Ohio," in Ohio State

Archaeological and Historical

Quarterly, LI (1942), 185-186.

I am indebted to Mr. Ernest J. Wessen,

Mansfield, Ohio, for the information

that the first known paper mill in Ohio was erected on

Little Beaver Creek, near what

is now East Liverpool, in

1807-1808. This fact has since been established by Dard

Hunter in

"Ohio's Pioneer Paper Mills," in Antiques, XLIX (January

1946), 36-39, 66,

an article which corrects and

supplements evidence on this subject offered by C. M

Thomas in the article cited above; by Jesse H. Shera, in Ohio State

Archaeological and

Historical Quarterly, XLIV (1935), 103-137; and by W. H. Venable, in Beginnings

of

Literary Culture in the Ohio Valley (Cincinnati, 1891).

CINCINNATI PUBLISHING 119

however. These pages are concerned with

the handcraft begin-

nings through the first three decades of

the nineteenth century.

THE READER AND THE BOOKS

Of the hundreds of thousands of pioneer

settlers who floated

down the Ohio and Mississippi rivers to

new homes in the wilder-

ness, most were literate and many were

well read. Wherever a

small community developed in a clearing,

a pioneer printer usually

appeared to publish a weekly newspaper,

a vital organ of commu-

nication and commerce in the

sparsely-settled country. In Cin-

cinnati, William Maxwell issued the

first number of the Centinel

of the North-Western Territory ("Open to all parties--but influ-

enced by none") on November 9,

1793, three years after the settle-

ment had been laid out and before there

were any political parties

in the territory for him to be

influenced by. Many of these little

sheets folded in a short time for want

of support, but so great was

the expansionist and speculative impulse

of the pioneering move-

ment that a new printer and a new paper

soon took the place of

the failure. Consequently, even though

most of the projects were

foredoomed, the persistence of the

promoters managed to keep the

new country pretty well supplied with

needed newspapers. And

it was the small presses of these

frontier newspapers that provided

the only printing facilities for

whatever books were published

during the early handcraft days.

It is the widespread influence of the

newspaper press tiat has

helped to make America the most literate

and well informed of

English-speaking countries over almost

its whole history. Al-

though the printing press was introduced

into this country nearly

200 years later than into England, so

rapid was the growth of our

newspaper press in the late eighteenth

and in the nineteenth cen-

tury that many new western American

towns were well supplied

with newspapers before the art of

typography was introduced into

such English cities as Rochester and

Manchester.3

During the very early period, before a

local supply of paper

and sizable printing plants made

extensive publishing possible,

most of the books issued in Cincinnati

were of a practical, educa-

3 Interesting statistics on this

subject appear in the introduction to Trubner's

Bibliographical Guide to American Literature (London, 1855).

120 OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL

QUARTERLY

tional, or religious nature and were

made to satisfy a local or at

least regional demand. Such works as

almanacs (which had to be

prepared for the meridian of

Cincinnati), directories, copies of

territorial and state legal codes, and

guides for river men and emi-

grants fall into this

classification. Books of general

interest and

works of literature were for the most

part supplied from Pitts-

-burgh and the East.

The existence of readers of taste who

formed a market for

belletristic works4 is shown by early

advertisements of shipments

of books received and for sale, often by

newspaper offices. The

earliest known public sale of books in

Cincinnati was that an-

nounced by an advertisement in the

columns of the Centinel of the

North-Western Tertitory, June 21, 1794.

Among other goods

listed was the following collection of

books:

Carrs Sermons--2 Vol.

Paradise Lost

Modern Chivalry, by H. H.

Brackenridge--2 Vol.

The Sexator or Parliamentary Chronicle

Senacas Morals

Rollins Belles Letters

Prince of Abyssinia

The Idler, by Dr. Johnston [sic]

Established eighteenth century works

were the largest class

of books advertised through the first

decade of the new century.

Prominent among forty titles of books

offered for sale by a news-

paper office in 1806 were the works of

Addison, Johnson, Collins,

Goldsmith, and Blackstone.5 It

was not long, however, until the

rising favorites of the new age displaced the Augustans. The

physical barriers of the Atlantic Ocean

and the Alleghany Moun-

tains did not prevent the new West from sharing the literary

rages of nineteenth century

England. The widespread American

practice of pirating popular English

works, which until 1891 were

not protected by international

copyright, and of issuing them in

cheap editions permitted the American

reading public to get the

4 The very early establishment of libraries also

testifies to this fact. The Cin-

cinnati Library, with books

purchased at a cost of over $300, was in operation as

early as March 1802. Cooperative investments in reading material were

made in at

least thirty Ohio communities before 1825. See William T. Utter The

Frontier State,

1803-1825, Carl Wittke,, The History

of the State of Ohio (Columbus, 1941-44), TI

(1942), 413-414.

5 Liberty Hall and Cincinnati Mercury, May 19, 1806.

CINCINNATI PUBLISHING 121

latest books of English poets and

novelists nearly as soon as Eng-

lish purchasers, and much more cheaply.

As a result, by 1820

Byron was the most popular writer in the

West. Among novelists,

Scott was the rage in the twenties, and

his vogue was followed by

that of Bulwer and, of course, Dickens.

American authors could

not compete with the involuntarily free

labor of English favorites,

and consequently they were seriously

handicapped in their efforts

to publish. At the same time, English

writers were receiving from

their admiring American readers all the

rewards of fame except

cash remuneration.

The readers of the West did not confine

their purchases to

cheap reprints, however. The following

notice printed in a Cin-

cinnati newspaper shows that as early as

1823 a

market existed for

the sale of really expensive books:

"On Wednesday Evening,

June 18, will be sold by Moses &

Jonas, at their Auction and Com-

mission Rooms, 173 Main street, a large

and valuable collection of

BOOKS, among which are some of the most

valuable and scarce

scientific works ever offered in the

western country." Among the

27 items listed were Donovan's Entomology,

sixteen volumes bound

in ten, with 576 elegantly colored

plates, handsomely bound, for

$130, and William Turton's Linne's System of Nature, London

edition, seven volumes, for $60. The

cheapest book listed was

Schoolcraft's Narrative, which

had just been published in 1821,

and which sold for two dollars.6

Although some literary and popular books

were produced

during the early years of publishing in

Cincinnati; educational,

religious, and practical works far

outnumbered them.

The first book published in Cincinnati

and in the whole

Northwest Territory, was Maxwell's Code,

the official edition of

the laws of the territory, which was

issued by subscription, in

March of 1796. The publisher of the work

was William Maxwell,

proprietor and editor of the Centinel

of the North-Western Terri-

tory and printer for the territorial legislature.7 In

the July 25,

6 Liberty Hall and Cincinnati

Gazette, June 6, 1823.

7 For biographical information about

Maxwell see C. B. Galbreath, "The First

Newspaper of the Northwest Territory. The Editor

and His Wife," in Ohio State

Archaeological and Historical

Quarterly, XIII (1904), 332-349, and D. C. McMurtrie,

"Antecedent Experience of William Maxwell, Ohio's First Printer," in

ib.d., XLI (1932),

98-103.

122 OHIO

ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

1795, issue of his paper, Maxwell

proposed to extend the official

200-copy edition of the Code to 1,000

copies, the additional 800

books to be sold to advance subscribers

at nineteen cents per fifty

pages and to non-subscribers at thirty

cents per fifty pages. Max-

well stuck to his price exactly. An

announcement of March 12,

1796, invited subscribers to pick up their copies of the

225-page

unbound book, for which they had to pay

86 cents.

Schoolbooks were published in the West

from very early

times although established eastern

publishers held the edge until

the McGuffey readers captured the

western market for Truman

and Smith's Eclectic Series in the

1830's. A Cincinnati newspaper

advertisement dated August 17, 1805,

announced a new western

grammar. Although its publishers

probably did not expect to

offer serious competition to Lindley

Murray's English Grammar,

the reigning favorite, their "Note

Below" indicates that they were

pushing it in hopes of a wide

distribution:8

THIS DAY IS PUBLISHED

And for sale at this office

Price 12 1/2 Cents.

AN

INTRODUCTION

TO

ENGLISH GRAMMAR

Designed for the use of Schools

By Dr. Staughton,

Late Principal of the College in

Borden-Town.

N.B. A handsome allowance will be made,

to

those who purchase by the dozen or

hundred.

By the time of the opening of the West,

almanacs had long

been an established American

institution. As a matter of fact, the

first book printed in the British

colonies was An Almanack for

New England for the Year 1639, which came from the press at

Harvard College. Begun originally as

calendars, almanacs grad-

ually accumulated astronomical and

astrological data, farming and

8 Liberty Hall and Cincinnati Mercury, December 16, 1805.

CINCINNATI PUBLISHING 123

domestic hints, chronologies of

important events, proverbs, jests,

and illustrations until they became

practically anthologies of pop-

ular reading. In order to give accurate

information about times

of sunrise and sunset and other

astronomical phenomena, these

works had to be calculated for the

meridians of the localities in

which they were to be used. It is

probably for this reason that

almanacs were published in Cincinnati as

early as 1805. The

Liberty Hall and Cincinnati Mercury for January 27, 1806, ad-

vertised as "For Sale at this

Office, Browne's Cincinnati Almanac,

For the Year of Our Lord, 1806,

Calculated for the meridian of

Cincinnati, by William M'Farland."

John W. Browne & Co.

were the publishers of Liberty Hall, and

their almanac was prob-

ably issued, according to the usual

manner, in the fall preceding

the year which it covered. Other

publishers of almanacs in fol-

lowing years included such familiar

early Cincinnati firm names as

Browne & Looker, in 1813; Looker

& Wallace, in 1814; Williams

& Mason, in 1816; Morgan, Lodge

& Co., in 1817; Ferguson &

Sanxay, in 1818; and Oliver Farnsworth

& Co., in 1822.9

The most interesting of the Cincinnati

almanacs is The Free-

man's Almanack . . . Containing a

great variety of useful selec-

tions; with the maxims and advice of

Solomon Thrifty, first issued

by Oliver Farnsworth in 1822 and published

by him and later by

N. & G. Guilford for more than

twenty years.10 In addition to

the sayings of Solomon Thrifty, a

typical number has end-sections

on such topics as education,

agriculture, gardening, and amuse-

ment, and the whole is illustrated with

crude but charming wood

cuts. "Solomon Thrifty" was

Nathan Guilford, son-in-law of

Oliver Farnsworth and partner with his

brother, George Guilford,

in a bookselling and publishing

business. Nathan Guilford was a

leading figure in the struggle for

common school legislation.

Through the fictional Thrifty, he

advanced practical arguments in

favor of universal education, and the

wide circulation of the al-

manac spread his ideas about free

schools through the backwoods

settlements. He was elected to the state

senate, where he spon-

sored the school bill passed in 1825,11

and, after the public school

9 Venable, Beginnings of Literary

Culture in the Ohio Valley, 50.

10 The Ohio State Archaeological

and Historical Society Library has copies of

this almanac for 1823-26, 1828, 1830-31,

1833-34, 1842, and 1844.

11 Obituary in Cincinnati Gazette,

December 20, 1854.

124

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

system had been established, he

personally induced many citizens to

send their children to the new

"pauper schools."12

When McFarland's almanac first appeared,

Cincinnati had

less than 1,000 inhabitants, any one of

whom, over ten years of

age, could probably supply a curious

stranger with detailed infor-

mation about any other of the town's

citizens. In 1819, however,

Cincinnati had a population of nearly

10,000 and became a city,

and, appropriately enough, in that year

its first directory appeared.

This was The Cincinnati Directory . .

. by a Citizen, a 155-page

duodecimo published by Oliver Farnsworth

and printed by Mor-

gan, Lodge & Co.13

In any new country or territory one sort

of book which

inevitably appeared was that which

described its geography,

fauna, flora, and social and political

life. Sometimes a book of

this sort was written, like Jefferson's Notes

on the State of Vir-

ginia, to correct misconceptions and to provide foreign

readers

with accurate and complete information

about a part of our coun-

try. Sometimes descriptive books were

written for the express

purpose of attracting settlers to new

regions and providing them

with a guide for their journey. Such works were often entitled

and usually referred to as

"emigrants' guides." They were pro-

vided for every stage of westward

expansion from the opening

of the Northwest Territory through the

Louisiana Purchase and

the settling of Texas, the prairie

states, California, and the Pacific

Northwest. An early guide of this sort

published in Cincinnati

was Edmund Dana's Geographical

Sketches on the Western

Country: Designed for Emigrants and

Settlers . . . , which came

from the press of Looker & Wallace

in 1815.14

12 "Our Early Book Supply,"

in Cincinnati Daily Gazette, June 12, 1880, 6.

13 Copy in Ohio State Archaeological and

Historical Society Library.

14 Throughout this period the new settlers were generally referred

to as "emi-

grants" even in the regions that

received them. Dr. Daniel Drake was scored by a

Philadelphia reviewer of his Natural

and Statistical View for his use of "immigrant" and

"immigration." In

criticizing Drake's diction, the reviewer said, "[The book] contains

several words which are not

recognized by the best lexicographers as legitimate portions

of the English language. Of this

number are freightage, immigrant, immigration, to

waggon, and a few others, most of them verbs, which, without

any competent author-

ity, our author has taken the liberty

to form from nouns, by prefixing the particle "to."

However great may be the advantages

which our country derives from the domestic

manufactures of our mechanics and

artists, we are yet to be convinced that our

language is improved by this copious

manufacture of American words. Although

it does not belong to British writers

to teach us how to think respecting our own

affairs, we must admit that they are

our safest guides in the use of language, and

that we ought, as yet, to be

extremely cautious of rebelling against their authority."

Portfolio, I, Series 5 (1816), 25-38.

CINCINNATI PUBLISHING 125

The most valuable and interesting early

descriptive works on

Cincinnati and the Ohio country were

written by Dr. Daniel Drake,

a pioneer physician, educator, and civic

leader, who founded the

Ohio Medical College in 1819

and who launched and edited the

Western Medical and Physical Journal.

As a tribute to Drake's

unusual talents and versatility, W. H.

Venable, in his literary

history of the Ohio Valley, referred to

him as "the Franklin of

Cincinnati." It would have been

just as fitting if Venable had

compared him to Jefferson, since it is

probable that the Notes on

the State of Virginia inspired Drake to write his Notices Con-

cerning Cincinnati ("Printed for the Author, at the Press of John

W. Browne & Co., 1810") and his

Natural and Statistical View or

Picture of Cincinnati and the Miami

Country ("Printed by Looker

& Wallace, 1815"). These

excellent sources of the natural and

social history of the region were

supplemented by a community

survey made at a slightly later date by

Daniel Drake's brother

Benjamin, in collaboration with Edward

Deering Mansfield. The

result of their efforts was Cincinnati

in 1826, a statistical work of

100 pages printed by Morgan, Lodge &

Fisher and issued in Feb-

ruary 1827. This is the earliest

example, for Cincinnati, of the

sort of municipal reference work

compiled by Charles Cist in his

Cincinnati in 1841 and later

volumes, and, together with the 1810

and 1815 productions of Daniel Drake, it

is an invaluable source

of materials for any study of Cincinnati

and its hinterland during

the first three decades of the

nineteenth century.

Of wider interest were Timothy Flint's

descriptions of the

Ohio and Mississippi valleys during the

second and third decades

of the century. A Massachusetts

missionary and a man of letters,

Flint was one of the multitude who

placed their families in flat-

boats at Pittsburgh and descended the

Ohio and Mississippi rivers.

His Recollections of the Last Ten

Years . . . (1826) describes his

travels and his preaching pilgrimages in

the Mississippi Valley and

contains vivid descriptions of the

details of frontier life in the

towns, in the backwoods settlements, and

on the rivers. Flint

later made Cincinnati his home for a

number of years, and there

he published The Western Monthly

Review, a nativist literary

magazine, from 1827 to 1830. The life of

this magazine is con-

126

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

temporaneous with the sojourn of the

Trollopes in Cincinnati, and

Timothy Flint would deserve a place in

literary history because

Frances Trollope approved of him, if for

no other reason. In

The Domestic Manners of the

Americans, Flint is praised as a

true gentleman of cultivation and

literary taste. One of his im-

portant works on the West was published

in Cincinnati in 1828.

This was A Condensed Geography and

History of the United

States, or the Mississippi Valley, in two volumes totaling over

1,100 pages. E. H. Flint, whom the

title-page imprint designates

as the publisher, was a Cincinnati

bookseller and a son of the

author.

River guides were even more

indispensable to their users than

were the descriptive works furnished for

new settlers. In the

days when the river was the main highway

of commerce and be-

fore channel markings had been provided,

these handbooks, illus-

trated with maps and charts and

providing up-to-date information

about navigation channels and about

various river ports, were used

by keelboatmen and flatboatmen and later

by steamboat pilots.

One of the earliest and most famous

series of guides (they were

revised almost yearly) was Zadok

Cramer's Navigator, the first

edition of which was published in

Pittsburgh in 1801. It was un-

doubtedly Cramer's guide that was

advertised in a Cincinnati

paper in 1806 as the "Ohio and

Mississippi Navigator, with a

number of plates of the

Mississippi."15

As Cincinnati grew and outstripped

Pittsburgh as a publishing

center and river port, most of the

guides came to be published

there. What was originally Samuel

Cumings' Western Navigator

has the longest history of any of the

Cincinnati publications. It

was issued under that title in

Philadelphia as early as 1822,16 and an

1825 Ohio copyright notice shows that

Cumings had transferred the

publication to Cincinnati, where he

issued the book as The Western

Pilot. In the early thirties, N. & G. Guilford published The

Western Pilot, although the copyright was still registered in

Cumings' name. In the late thirties and

during the forties,

George Conclin held the copyright and

issued the book as The

15 Liberty Hall and Cincinnati Mercury, May 19,

1806.

16 Copy in Historical and

Philosophical Society, Cincinnati.

CINCINNATI PUBLISHING 127

Western Pilot and as Conclins' [sic] New River Guide. U. P.

James acquired the rights by the middle

fifties. He revised the

work, entitled it James' River Guide,

and continued to publish it

until the middle seventies, by which

time the guides' long period

of usefulness was drawing to an end.

Such religious works as sermons;

catechisms, and hymnals

were a common feature of Cincinnati

publishing in its early years.

In addition to these standard types,

there were some works issued

from the press which for their

unusualness are worthy of attention.

The Swedenborgian movement, which had

been introduced into

this country by 1785, had a congregation

in Cincinnati even be-

fore 1811, when the first Swedenborgian

society west of the Alle-

ghany Mountains and the second in the

United States was organ-

ized by Adam Hurdus.17 It was

in Cincinnati that two of Sweden-

borg's works were published in their

third American edition in

1820. One of these was The Heavenly Doctrine of the New

Jeru-

salem . . . from the Latin of Emanuel

Swedenborg, the title page

of which carries the imprint,

"Cincinnati: Printed by Benjamin F.

Powers, 1820."18 The other work of Swedenborg, also issued by

Powers, is The Doctrine of the New

Jerusalem Concerning the

Lord.19

Another religions publication possessing

bibliographical inter-

est is The Methodist Magazine for the

Year of Our Lord 1821,

which carries the imprint of Martin

Ruter, the agent of the newly-

established Western Methodist Book

Concern. This volume is

unusual as an early example of a

publication printed in Cincinnati

and displaying a double imprint on its

title page:

"Published by N. Bangs and T.

Mason, New York.

Cincinnati: Published by Martin Ruter .

. . . 1821."

The Cincinnati production of the

magazine is indicated by the

printer's imprint of Morgan, Lodge &

Co.

John Foxe's Book of Martyrs was a

very popular standard

work that accompanied Protestant

American pioneers in their

17 Ophia D. Smith, "Adam

Hurdus and the Swedenborgians in Early Cincinnati;",

in Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Quarterly, LIII (1944), 113.

18 Copy in Ohio State Archaeological and

Historical Society Library.

19 Benjamin Powers was a brother of Hiram Powers, the

sculptor. He was a

lawyer and a journalist; in January 1823 he became

editor of the Liberty Hall and

Cincinnati Gazette. Ophia Smith, op. cit., 128.

128

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

westward march. In the days before

blood-and-thunder romances

were available in cheap paper editions,

this household favorite

supplied sensational reading material

for young and old and no

doubt helped to foster the violent

anti-Catholic feeling which

was common in many parts of the country

during the nineteenth

century. An early foreign language

publication in Cincinnati was

a German edition of the Book of

Martyrs which was issued in 1830,

before the full flood of German

immigration had begun.20 The title

page of this edition supplies

the-following information:

Geschichte der Martyrer, nach dem

Ausfuhrlichen Original des ehrw.

Johann Fox und Anderer. Kurz gefasst

und, besonders fur den gemeinen

Deutschen Mann in den Vereinigten

Staaten von Nordamerica, aus dem

Englischen ubersetzt von I. Daniel

Rupp. . . .

The imprint at the foot of the title

page reads, "Cincinnati: Ge-

druckt und verlegt durch Robinson und

Fairbank, 1830"21 The

fact that the book was copyrighted and

that the copyright was

registered in the name of Robinson &

Fairbank indicates that Rupp,

the translator, was probably living in

or near Cincinnati at the

time, and the English captions on the

cuts suggest that there may

have been a companion edition in English

published in Cincinnati.22

Despite the preponderance of books of a

practical, educational,

and religious nature, the early

Cincinnati press also catered to

literary and popular tastes. Since

western literary efforts at this

time were usually in the form of short

stories, sketches, and poems,

most of these pieces saw print in

periodicals and annuals. Timothy

Flint's Western Monthly Review (1827-30),

which has already

been mentioned, was not the first

Cincinnati literary periodical.

The pioneer in that field had been the Literary

Cadet (1819-20),

which was closely followed by the Olio (1821-22). A little

20 One writer indicates that in 1830 the German

population of Cincinnati was

less than 1,500, or about five per

cent of the total. By 1840, however, the proportion

had increased to 23 per cent. Francis

P. Weisenburger, The Passing

of the Frontier,

1825-1850, Wittke, ed., The History of the State of Ohio, III

(1944), 52. In a city

of over 46,000, this meant a German

element of over 10,500.

21 Copy in Ohio State

Archaeological and Historical Society Library.

22 The translator was undoubtedly the

J. Daniel Rupp whom the American Pub-

lishers' Circular later identified as the publisher of a Collection

of 30,000 Names of

German, Swiss, Dutch, French, Portugese, and Other Immigrants

in Pennsylvania

Chronologically Arranged from 1727 to

1776, which was issued in Harrisburg

in 1856.

American Publishers' Circular, II, June 14, 1856, 352.

CINCINNATI PUBLISHING 129

later came the weekly Cincinnati

Literary Gazette, which was pub-

lished by John P. Foote, the bookseller,

in 1824 and 1825.23

Gift books were popular throughout the

country from about

1825 through the Civil War years. They

were annual miscellanies

of stories, essays, and poems, elegantly

printed and bound, and

garnished with many engravings, or, as

they were called at the

time, "embellishments." Some

of these volumes, such as The

Atlantic Souvenir (1825-32), displayed the best art and literature

of the period before the popular monthly

magazine came into its

own. It is thought that the gift book

represents the evolution of

the almanac into a decorative literary

publication, largely as a re-

sult of the increasing regard for

feminine taste that characterized

the period.24

The first annual published in Cincinnati

and in the whole

West was The Western Souvenir, A Christmas and New Year's

Gift for 1829, edited by James Hall and published by N. & G.

Guilford, probably in the latter part of

1828 because such works

were usually predated and issued before

the Christmas season.

This little volume of 324 pages,

illustrated by engravings and

availablein a satin or tooled leather

binding, compares favorably

with other books in the same class.25

Western American in its

subjects and fresh in its treatment, it

is not so tainted by gentility

as many of the other gift books of the

period. Contributors to the

Western Souvenir included Otway Curry, Timothy Flint, Morgan

Neville, Benjamin Drake, and James Hall,

the editor, Hall, who

later edited the Western Monthly

Magazine, exhibits a style su-

perior to that of most other western

writers of his generation.

The sales value of books that exploit

popular interest in sen-

sational subjects has long been

appreciated by publishers and book-

sellers. (It was, in fact, just this quality that accounted for the

success of such "religious"

works as Foxe's Book of Martyrs.)

23 Information concerning early Ohio

literary periodicals may be found in Lucille

B. Emch, "Ohio in Short

Stories," in Ohio State

Archaeological and Historical Quar-

terly, LIII (1944),

209-250.

24 R. Thompson, American

Literary Annuals & Gift Books,

1825-1865 (New

York, 1936), 3.

25 "Well done for the

backwoods!" was the spirit of the

eastern reviewers'

reception of the Western

Souvenir. Thompson describes the writing

in this annual as

"for the most part

alive with the excitement and color of

frontier life." He further

says that "a rival

gift book issued in Detroit two years

later, The Souvenir of the Lakes,

is relatively immature and

unsatisfactory." Ibid., 95.

130 OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL

QUARTERLY

As early as 1798 a Cincinnati newspaper

carried an advertisement

which was obviously designed to play up

the lurid features of a

book announced as "Just Published

and for Sale." This work,

which in all probability was not a

Cincinnati publication, was intro-

duced as "the CANNIBALS' PROGRESS;

or, The Dreadful

Horrors of FRENCH INVASION, As displayed by the French

Republican Officers and Soldiers, in

their Perfidy, Rapacity, Fero-

ciousness, and Brutality, exercised toward the innocent inhabitants

of Germany."26

One of the earliest books printed in

Cincinnati was a descrip-

tion of a famous local criminal trial to

which was added a bio-

graphical sketch of the culprit. The

book bore the title, The Trial

of Charles Vattier, Convicted of the

Crimes of Burglary and Lar-

ceny, for Stealing from the Office of

the Receiver of Public

Monies for the District of

Cincinnati, large sums in Specie and

Banknotes . .

. , and was issued from the press

of David Carney

of The Western Spy. It was

published by subscription in July

1807.27

DEVELOPMENT OF PUBLISHING FACILITIES

For almost twenty years after the issue

of the first book in

Cincinnati, very little publishing was

carried on, both because

facilities were lacking and because the

market had not yet devel-

oped. When Maxwell's Code was

issued in 1796, there was only

one printing press in Cincinnati, that

of the Centinel of the North-

Western Territory. By 1815 there were two newspapers, Liberty

Hall and The Western Spy, and each of these had an

extra press

for book printing.28 The printing plant

of the Liberty Hall at this

time is described by W. T. Coggeshall,

who wrote 35 years later

when the shop of the same newspaper had

five steam presses and

26 Freeman's Journal, October

27, 1798.

27 The proposal for publishing the

book, which appeared in the Liberty

Hall and

Cincinnati Mercury, May 18, 1807, indicated that the price in stitched sheets

would

be 50 cents, in boards, 75 cents.

Much latex than The Trial of Charles

Vattier, but also appealing to popular

interest in crime, was a 128-page

volume, Murder Will Out . .

. The Horrors of the

Queen City, by an "Old Citizen," William L. DeBeck, which was published in Cin-

cinnati in 1867. This work is interesting in that it

presents a chronology of the most

sensational events in the city's

criminal history from early times and thereby provides

a source of information about one phase

of the young river port's culture that is usually

neglected in conventional studies.

Cincinnati did not receive its most distinguished

treatment of local crime, however, until

the early seventies, when Lafcadio Hearn, a

young reporter on one of its daily

papers, wrote up a brutal tanyard murder so effectively

as to exhaust several editions of

the Enquirer within a few hours.

28 Daniel Drake, Natural and Statistical View, 153.

CINCINNATI PUBLISHING 131

four hand job presses. In 1815, however,

the work was all done

by hand. The press was crude and

operated on the principle of

screw pressure, much like a hand cider

press. The pressman

turned a screw to bring the platen down

on the form, which was

inked not by composition rollers but by

a boy who beat it with

inked buckskin balls before the taking

of each impression. A

stalwart pressman, with the aid of an

active boy, could turn out

250 impressions an hour. The Liberty

Hall office housed two

presses of this kind, which, with the

necessary type and other

equipment, represented a

capital investment of about

1,000

dollars.29

George Williamson, who opened his shop

in 1806, was appar-

ently the first bookbinder in

Cincinnati. His first advertisement

suggests a certain diffidence in his

attitude towards his business,

which he subordinates to his concern

over a missing horse:

"Strayed or Stolen . . . A Black

Mare . . . ," for the return of

which a five-dollar reward is offered by

"George Williamson,

Who is now prepared to carry on the

BOOKBINDING BUSI-

NESS . . . in Main street."30 One

of Williamson's earliest jobs

of any consequence was probably the

binding of The Trial of

Charles Vattier.

In the early years, before two mills

were set up on the Little

Miami in 1810 and 1811, one of the chief

hindrances to extensive

publishing was the absence of a local

supply of paper. Although

there had been a mill in Georgetown,

Kentucky, since 1791, its

output was limited, and difficulties of

transportation further in-

creased the problems of supplying the

Cincinnati press. As a

result, frontier newspapers were

frequently required to suspend

publication or to curtail their size.

The 1807 file of the Liberty

Hall and Cincinnati Mercury contains a miniature edition, that for

January 6, printed on writing paper. It

carries the following an-

nouncement:

It is with extreme regret that the

editor is obliged to issue the present

number on a writing-sheet, occasioned by

a disappointment in the receipt

of paper. He hopes it will be the only

instance which will occur, as his

29 W. T. Coggeshall, "A

Printing Office in 1815 and 1850," in History of the

Cincinnati Press and Its Conductors,

1793-1850, scrapbook in Historical and

Philo-

sophical Society, Cincinnati.

30 Liberty Hall and

Cincinnati Mercury, January 27, 1806.

132 OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

son is now in Kentucky for the express

purpose of purchasing a supply of

that necessary article.

When the pioneer editor's paper

problem was complicated by

money troubles, his plight was sorry

indeed, but not at all unusual.

In the July 30, 1808, number of the same

paper, which is also

printed on a small sheet, the editor

voices the hope that some of

his subscribers who have money will

"furnish the Editor with a

little, to send to the Paper-mill; otherwise

he is apprehensive that

Liberty Hall will sink for want of a few dollars to prop it. 'Tis

hard to print and get nothing, and find

paper in the bargain."

It is natural that publishers of

newspapers would not be in-

clined to use their presses for book

work to any great extent when

they had such great difficulty in

getting the paper necessary to

maintain a newspaper. Therefore it is

not surprising to discover

that the building of paper mills near

Cincinnati gave a noticeable

impetus to local book publishing. This

fact was commented upon

by Dr. Drake, who, writing in 1815,

referred to the year 1811 as

a turning point:

Ten years ago, there had not been

printed in this place a single volume;

but since the year 1811, twelve

different books, besides many pamphlets,

have been executed. These works, it is

true, were of moderate size; but

they were bound, and

averaged more than 200 pages each. The paper used

in these offices [Liberty Hall and

Western Spy] was formerly brought from

Pennsylvania, afterwards from Kentucky,

but at present from the new and

valuable mills on the Little Miami.31

While the first part of Drake's

statement is not strictly accurate

(Maxwell's Code had been issued

nineteen years earlier), it is

true if applied to bound books. And

although the progress

acclaimed by Drake seems insignificant

in comparison with Cin-

cinnati's output even ten years later,

he had considerable justifica-

tion for his expansiveness. He was

writing before the day of the

steamboat and at a time when

Cincinnati had only 5,000

inhabitants.

The mills on the Little Miami were

within thirty' miles of

Cincinnati, but it was not long before

the city had an even-closer

supply. Drake and Mansfield's Cincinnati

in 1826 indicates that

31 Daniel Drake, op. cit., 153.

CINCINNATI PUBLISHING 133

by that time the city had two paper

mills in operation and another

one under construction. One was Duval's

Paper Mill, located at

Mill Grove but owned by Cincinnati

citizens and furnishing the

Cincinnati market.32 The

other two mills were both powered by

steam. With this innovation it required

only the introduction of

stereotyping about the turn of the

decade and of power presses

early in the thirties for Cincinnati to

be ready to begin the mass

production of books for the new western

market.

The first of the steam-powered mills

mentioned by Drake and

Mansfield was the Cincinnati Steam Paper

Mill, which was owned

by Phillips and Spear. It was located on

the bank of the river in

the western part of the city and was

housed in a building 140 by

130 feet. Drake and Mansfield stated

that the "establishment em-

ploys about forty hands, and produces

annually a large quantity

of excellent paper."33 The other

Cincinnati plant, the Phoenix

Paper Mill, received the following

notice:

During the past summer, a fine

establishment for the manufacture

of paper was erected under the

superintendence of the Messrs. Grahams, on

the river bank, in the western part of

the city. When about to go into

operation, in the month of December, it

was entirely consumed by fire. The

owners of it are now erecting upon its

ruins another, to be called the

Phoenix Paper Mill, which is 132 by 36

feet, exclusive of the wings. Its

machinery will be worked by a substantial

steam engine, and probably go

into operation by the first of June.34

During the second decade of the century,

Cincinnati more

than quadrupled in population, so that

in 1820 it was a city of

10,000. Its printing facilities

increased too, both by the establish-

ment of new presses and by the

manufacturing of type and

printers' supplies. The first Cincinnati

directory indicated that in

1819 there were three newspapers, each

of which had book and

job offices, and two other independent

book and job. offices as

well.35

Type was first cast in Cincinnati about

1820, when the Cin-

cinnati Type Foundry was established by

Oliver Wells and John

32 Benjamin Drake and E. D.

Mansfield, Cincinnati in 1826 (Cincinnati, 1827),

33 Ibid., 62.

34 Ibid.

35 Cincinnati Directory for 1819 (Cincinnati, 1819), 152.

134 OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND

HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

P. Foote, the bookseller,36 and the

manufacture of printing presses

and equipment was soon an important

branch of the same business.

By 1823 a newspaper article.plumping for

western self-sufficiency

in book-publishing stated that

"type of great variety and of excel-

lent quality--printing presses of new

and improved structure, and

all the necessary apparatus for neat and

expeditious printing, are

already manufactured in this city."

The writer said that for too

long the West had been paying tribute to

the East in the same way

that all the states formerly had to the

mother country. Now it

was time for the West to supply her own

needs: "We wish all

our printing to be done in the Western

Country."37 For the book

trade this was an early expression of

the theme of self-sufficiency

that obsessed westerners throughout the

nineteenth century period

of industrial expansion. There was in

fact considerable justifica-

tion for this attitude because, with the

scarcity of money in fron-

tier communities and the high discount

rates on western money in

the East, any money sent to purchase

goods in the East involved a

personal loss to the buyer and also

handicapped Western business

by removing a portion of its

badly-needed medium of exchange.

A description of the Wells Type Foundry

by Drake and

Mansfield indicates its products and

also makes a point of the fact

that printing materials no longer had to

be imported:

THE MESSRS. WELLS' TYPE FOUNDRY AND

PRINTERS'

WAREHOUSE, is situated on Walnut street,

between Third and Fourth,

where they manufacture, in a superior

manner, all kinds of type, presses,

chases, composing sticks, proof gallies,

brass rule, &c., &c., at the eastern

prices. They employ about 23 hands. This

valuable establishment has

entirely superseded the importation of

type and other printing materials

from the eastern states.38

"With the exception of ink,"

the authors might have added. De-

spite the hopeful strivings of many

manufacturers, a number of

years were to pass before an entirely

satisfactory printing ink was

manufactured in Cincinnati. A

contemporary review of Drake

and Mansfield's book adds the

information that many of the Wells

printing presses were actually shipped

"to the East and South:

36 "Our Early Book Supply,"

loc. cit., 6.

37 Liberty Hall and Cincinnati Gazette, June 6, 1823.

38 Drake and Mansfield, op. cit., 63.

CINCINNATI PUBLISHING 135

where the demand, as well as in the

West, is constantly in-

creasing."39

By the end of 1826 Cincinnati had a

population of over 16,000,

its first daily newspaper had been

established, the steamboat pro-

vided quick transportation to any part

of the Mississippi and Ohio

valleys, and the printing presses of the

city were already beginning

to turn out books in impressive numbers.

During the year 1826

the city's nine printing establishments

produced the following

books, in addition to more than 7,000

newspapers a week;

61,000 Almanacs

55,000 Spelling Books

30,000 Primers

3,000 Bible News

3,000 American Preceptors

3,000 American Readers

3,000 Introduction to the English Reader

500 Hammond's Ohio Reports

500 Symmes' Theory

3,000 Kirkham's Grammar

1,000 Vine-Dresser's Guide

14,000 Pamphlets

5,000 Table Arithmetics

2,000 Murray's Grammar

1,500 Family Physician

14,200 Testaments, Hymn, and Music

Books40

This list accounts for more than 85,000

copies exclusive of the

pamphlets and provides quite a contrast

with the situation ten

years earlier when Dr. Drake was elated

over twelve books pro-

duced in a four-year period. Of the

books produced during 1826

about a third were the popular and

useful almanacs; nearly a tenth

were religious works, and over half were

schoolbooks. The great

and sudden increase in the output of

schoolbooks can be explained

largely by the fact that the first state

public school system had just

40 Drake and Mansfield, op. cit., 64.

One of the works mentioned in this list,

Symmes's Theory, is a curious volume which elaborates the theory

propounded by a

somewhat eccentric philosopher, Captain J. C. Symmes, a

nephew of the John Cleves

Symmes who was the Cincinnati founder.

The full title of this book is Symmes's The-

ory of Concentric Spheres;

Demonstrating that the Earth is Hollow, Habitable Within,

and Widely Open About the Poles.

By a Citizen of the United

States [James McBride].

A possibly tongue-in-cheek

advertisement by the publishers, Morgan, Lodge & Fisher,

explains that "Some errors of the press will

doubtless be discovered; as (in the absence

of both Compiler and Theorist), there

was no proof-reader at hand, sufficiently versed

in the New Theory, at all times, to

detect them."

39 Western Monthly Review, I (1827), 61.

CINCINNATI PUBLISHING 137

been established in 1825 with the

passage of the legislation fostered

by Nathan Guilford.

A clearer idea of the printing activity

in Cincinnati at this

time may be gained by considering the

output of a single shop. At

the establishment of Oliver and William

Farnsworth, printers of

the Western Monthly Review, three

presses were constantly em-

ployed, and there issued from them,

within the space of six or

seven months, "at least 9,000

spelling books--7,000 Murray's

introduction and English reader--6,000

English grammars--2,000

arithmeticks--15,000 primers and chap

books for children--and

60,000 almanacks; all of which have a

ready and rapid sale."41

In the closing years of the third decade

of the century, Cin-

cinnati, with a population of between

25,000 and 30,000, was the

largest city in the West. Her printers

and bookmen were sup-

plied with a rapidly growing market, and

it needed only the intro-

duction of stereotyping and power

presses to enable them to de-

velop the industry which during the

1830's made Cincinnati the

acknowledged publishing center for the

whole West.

EARLY BOOKSELLERS AND PUBLISHERS

Henry Howe spoke truly when he said that

the regular book

merchant, the trader in ideas, was the

very last business man to

be established in a young community.42

In Cincinnati, a successful

and well-established bookstore did not

exist for more than twenty

years after the publication of Maxwell's

Code. The reason is

that during the early years a market did

not exist which would

support and profit a man who dealt in

books exclusively. To gain

41 Western Monthly Review

I (1827), 62.

42 Preface to Travels and Adventures

(Cincinnati, 1853).

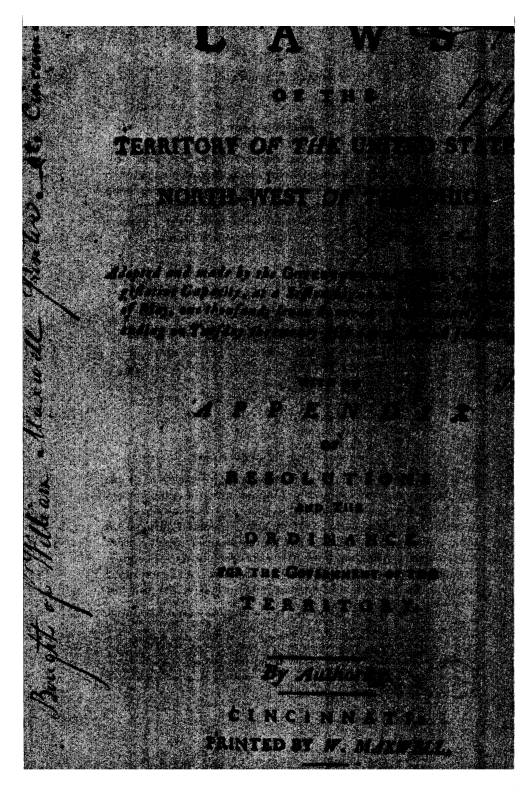

THE MAXWELL CODE. The first book

published in the Northwest

Territory was a volume of the Laws of

the Territory passed in 1795,

printed in Cincinnati by William Maxwell

in 1796. The photograph is of a

copy in the Rutherford B. Hayes Library

at the Hayes Memorial, Fremont.

This book was a subscription copy,

purchased by Daniel Symmes at

Maxwell's print shop. Unfortunately it

was placed in a fancy binding many

years later, and the binder trimmed part

of the title page.

138

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

recognition for useful service in a

pioneer community, a man

might better be a specialist in milling,

harness-making, or tanning.

Books were of course sold during the

early period, but the

transactions were usually conducted by

auction or as a side line

to general storekeeping or newspaper

publishing. By 1810 books

were regularly offered for sale by

Carpenter and Findley, pub-

lishers of the Western Spy, and

by J. W. Browne & Co., publishers

of the Liberty Hall, who

established a bookstore next door to. their

printing office. At about the same time

the drugstore of D. Drake

& Co. carried a line of books at its

stand in Main Street, opposite

Lower Market.43

Until recently, much confusion existed

about the identity of

the first bookstore in Cincinnati to

rely entirely on the sale of

books and stationery for its existence.

W. T. Coggeshall, who

in the mid-nineteenth century explored

the history of the Ohio

press, said that the first store

"which did a regular book business

and met with liberal encouragement was

established by Phillips and

Coleman in 1815."44 W. H. Venable

made two choices. In a

newspaper article published in 1886, 'he

said, "The first bookstore

in the city was opened in 1819, by

Phillips and Spear."45 By

1891,

when Beginnings of Literary Culture

in the Ohio Valley appeared,

Venable had apparently changed his mind,

for in that work he

said, "So far as I have been able

to ascertain, John P. Foote was

the proprietor of the first regular

bookstore in Cincinnati";46

Foote's store was established about

1820.

Although Venable's second choice is

probably the more ac-

curate if the question is limited to

permanent establishments, the

whole matter has since been cleared up,

so far as it can be, by

Edward A. Henry, who closely combed all

the early Cincinnati

newspapers for that purpose.47 His

findings establish the fact

that the words book-store and bookseller

were first used in Cincin-

43 "Our Early Book Supply,"

loc. cit.

44 Coggeshall, "The Origin and

Progress of Printing," loc. cit.

45 Cincinnati Commercial Gazette, December 11, 1886.

46 Pages 53-54.

47 E. A. Henry, "Cincinnati as a

Literary and Publishing Center, 1793-1880," a

paper presented at the 1937 meeting

of the American Library Association. References

made here are to the 15-page

typewritten manuscript in the Historical and Philosophical

Society, Cincinnati, although the

paper has been printed in Publishers' Weekly,

CXXXII (July 3-10, 1937), 22-24,

110-112.

CINCINNATI PUBLISHING 139

nati advertising in the columns of Liberty.

Hall in April 1812, in

reference to the bookstore which its

publishers, J. W. Browne

& Co. maintained next door to the

printing office. The first book-

seller to stake his success on the sales

of books and paper alone,

however, was John Corson, whose June 6,

1812, advertisement

in the Western Spy was headed

"JOHN CORSON'S, BOOKS &

STATIONERY ONLY." The only referred

to the fact that

J. W. Browne's bookstore also handled

drugs and patent medi-

cines. But Corson evidently was not able

to get along by book-

selling alone because during the next

year he added other lines

until his Main Street establishment

became a general store. His

chief interest seems to have been in his

original specialty, however,

because he opened a circulating library

in his store in August

1813, and over two-thirds of his

advertising continued to be de-

voted to books.48

John P. Foote was probably the earliest

successful bookseller

who remained in business for any length

of time. In about 1820

he opened a store at No. 14 Lower Market

Street which he main-

tained until 1828, when he sold out to

N. & G. Guilford. Foote,

an organizer of the Cincinnati Type

Foundry and publisher and

editor of the Cincinnati Literary

Gazette, was a man of unusual

talents. He was a member of the

Semi-colon Club, the exclusive

little literary group to which Harriet

Beecher later belonged; and

Morgan Neville, E. D. Mansfield, Nathan

Guilford, and Benjamin

Drake were among the book-minded men who

made his store a

gathering place. In a book which he

later wrote, Foote mentioned

the fact that he was older than the city

of Cincinnati. Although

he retired from the book business in

1828, when he was 45 years

old, he lived until 1865 and during his

later years wrote two books,

The Schools of Cincinnati and

Vicinity and A Memoir of Samuel

E. Foote, a biography of his brother.49

Other booksellers of the twenties

included Drake & Conclin,

Foote's chief competitors, who kept shop

at 43 Main Street until

48 Ibid., 11.

49 "Our Early Book Supply," loc. cit.

140 OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

1829;50 George Charters, who as early as

1819 had a small book-

store on East Fifth Street in connection

with a circulating library

and a piano business;51 Thomas

Reddish, a native of England, who

also maintained the Sun Circulating

Library and a loan office at

53 Broadway;52 William Hill

Woodward, who sold coffee as well

as books in his store at the corner of

Fifth and Main streets;53

and E. H. Flint, the son of Timothy

Flint, who opened a book-

store at the corner of Fifth and Walnut

streets in 1827. Ac-

cording to his statement in an

advertisement he kept standing in

the Western Monthly Review in 1827, Flint had ambitious plans

for expanding his market: "Having

recently commenced the busi-

ness of sending books to all the chief

towns and villages in the

valley of the Mississippi, he will be

able to make up packages with

neatness, and transmit them with safety

and dispatch to any town

in the Western and Southwestern country.

Being determined to

devote himself to that business, and to

make annual visits to those

towns and villages, he solicits orders

of this kind, for which he

will charge very moderate

commissions."

In a young community like Cincinnati,

where professional

booksellers were relatively slow in

establishing themselves, one

would hardly expect to find men who made

the publishing of books

their entire business. In fact, during

the greater part of the nine-

teenth century, most houses maintained a

retail bookselling depart-

ment and did not depend entirely upon

their publishing activities

for their existence. In Cincinnati, most of the early publishing

was done by booksellers and printers. It

will be recalled that

E. H. Flint, the bookseller, published

his father's Geography and

History of the Western States, while Oliver Farnsworth, a printer,

published the Freeman's Almanack and

the first Cincinnati direc-

tory.

50 These were John T. Drake of

Massachusetts and William Conclin of New York.

In 1829 John Drake formed a business

connection with Phillips & Spear, paper makers.

In 1830 he died, and his brother

Josiah succeeded him in the firm. In 1831 Josiah es-

tablished a bookstore at 14 Main

Street, where he prospered greatly, employing about

twenty clerks and salesmen and

grossing about $80,000 a year; he retired from business

in 1839. William Conclin continued the bookstore at 43 Main Street

for thirteen years

after the partnership with John T.

Drake was dissolved. He was succeeded at the same

address by his brother George Conclin,

bookseller and publisher; upon his death Apple-

gate and Co. took the location, and

they were succeeded by A. P. Pounsford & Co. Ibid.

51 Ibid.

52 Ibid. Reddish was a Swedenborgian and

published The Dagon of Calvinism

in 1822. Ophia Smith, op. cit.,

130.

53 W. H. Venable, in Cincinnati Commercial Gazette, December

11, 1886.

CINCINNATI PUBLISHING 141

The most important and active publishers

of the early period

were N. & G. Guilford and Ephraim

Morgan. Morgan began his

long career as early as 1805 as a

printer's devil in the Western Spy

office, where he probably belabored many

forms with inky buck-

skin balls with no way of imagining a

future in which his printing

plant, the largest in the Queen City,

would be filled with the roar

of automatically inked power presses.

Nathan Guilford was born in Spencer,

Massachusetts, in

1876. After his graduation from Yale in 1812, he read law and

shortly moved west to Kentucky, where he

settled for a few years.

In 1816 he moved to Ohio, took the state

bar examination, and

began the practice of law in Cincinnati.

He soon espoused the

cause of free schools and as

"Solomon Thrifty" and a state senator

supported.common school legislation.54

In 1828 he and his brother

George purchased the business of John P.

Foote at No. 14 Lower

Market Street and began an active career

of publishing and book-

selling.55 It is quite possible that

George was most concerned with

the mechanical details of the business

because little information

about him is available, aside from the

fact that he advertised in

Cist's Cincinnati in 1841 a

printing ink of his own manufacture.

By 1830 this enterprising new firm,

which had been in business a

scant two years, had already published

the Freeman's Almanack,

James Hall's Western Souvenir, and

schoolbooks including Lind-

ley Murray's English Reader.

The Guilfords continued active into the

thirties. One of their

western schoolbooks was The Juvenile

Arithmetick and Scholar's

Guide (1831), by Martin Ruter, then president of Augusta Col-

lege and before that the first agent of

the Western Methodist Book

Concern. They also published a

stereotype edition of J. E. Wor-

cester's Comprehensive Pronouncing

and Explanatory Dictionary

of the English Language (1834), which was for many years the

chief competitor of Webster's

dictionary. Their edition of Tim-

othy Flint's Life and Adventures of

Col. Daniel Boone (1833)

proved popular. The same biography was

later successfully issued

by George Conclin, by Applegate &

Co., and by U. P. James, who

54 Obituary of Nathan Guilford, in Cincinnati

Gazette, December 20, 1854.

55 "Our Early Book

Supply," loc. cit.

142

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

brought out an edition as late as 1868.

Another long-lived work

published by the Guilfords in the early

thirties was Samuel Cum-

ings' river guide, The Western Pilot.

Both Nathan Guilford and Ephraim Morgan

were typical

Cincinnatians of the first generation in

that they were natives of

eastern states. Morgan was born in

Brimfield, Massachusetts, in

1790. While he was still a small boy,

his family joined in the

westering movement, and settled in Ohio.

At the age of fourteen,

Ephraim Morgan was an apprentice in the Western

Spy office.

He became a Quaker convert and in 1814

married Charlotte An-

thony, a Quakeress of Virginia stock.

Morgan rose in his trade

and in 1826 was the senior partner in

the firm of Morgan, Lodge

& Fisher when that company

established the Cincinnati Daily

Gazette with Charles Hammond as editor.56 In 1828 Morgan

withdrew from this company because of

his opposition to the

paper's policy of running advertisements

for the return of fugitive

slaves, and set up in the book printing

and publishing business at

131 Main Street.57 For

several years John Sanxay was his asso-

ciate in publishing here, and the house

of Morgan & Sanxay pub-

lished many books, the majority of which

were standard religious

and educational works. Morgan also

sponsored local belletristic ef-

orts, however, as when he published

Benjamin Drake's Tales and

Sketches from the Queen City (1838).

While continuing his

publishing activities, he also built up

in partnership with his sons

the largest printing office in the West,

with stereotyping and bind-

ing as important departments. Morgan's

power presses accounted

for a good share of Cincinnati's

importance as a publishing

center.58

Ephraim Morgan continued. publishing, in

partnership with.

his sons, into the middle years of the

century. In 1851, Charles

Cist described E. Morgan and Co. as

"one of our oldest as well as

most extensive houses in the publishing

line" and added,

56 Biographical Cyclopaedia . . . of Ohio (Cincinnati, 1895), VI,

1427-1428.

57 "Our Early Book Supply," loc. cit.

58 W. H. Venable stated that in the year

1830, Morgan had "five power presses,

propelled by water, each of which could throw off 5,000

impressions daily." Beginnings

of Literary Culture in the Ohio

Valley, 51-52. Venable's date is

ten years too early.

The figures which he gives here

correspond exactly with the statistics on Morgan in

Charles Cist's Cincinnati in 1841 (Cincinnati, 1841). The

first power press was not

brought to Cincinnati until 1834.

CINCINNATI PUBLISHING 143

Within the last twelve months they have

issued from the press 20,000

Family Bibles; 15,000 Josephus's Works;

5,000 each, Pilgrim's Progress

and Hervey's Meditations; 10,000 Life of

Tecumseh; 10,000 Psalms of

David; 10,000 Talbott's Arithmetic;

10,000 Walker's School Dictionary;

1,000 Macaulay's History of England, and

100,000 Webster's Spelling

Books, with various other publications

in smaller editions. Total value,

$54,000.59

The Life of Tecumseh mentioned here

was one of the pro-

ductions of Benjamin Drake, the brother

of Dr. Daniel Drake.

The book was first published in 1841,

and a run of 10,000 ten years

later indicates a substantial success

for a publication written, pro-

duced, and circulated "at the

West." Morgan seems to have done

his share in supporting western literary

ventures. As late as

1854 his imprint as publisher appeared

on the title page of the

Poems, third edition, of Mrs. Helen Truesdell, an Ohio

poetess.60

Between 1796 and 1830 the population of

Cincinnati increased

fifty-fold. The log cabin village grew

to a city of nearly 30,000,

the largest in the West, and its growth

and development were

representative of the change that was

taking place throughout the

regions drained by the great rivers. And

still the country was

just on the threshold of its period of

greatest expansion. For

the western book trade, the vast numbers

of literate Americans

peopling the new states and territories

comprised a market which

challenged Cincinnati paper makers,

publishers, pressmen, stereo-

typers, binders, booksellers, and book

agents to provide needed

volumes in such quantities as to leave

no doubt of the city's right

to its title as the "Literary

Emporium of the West" during the

expansive decades before the Civil War.

59 Charles Cist, Cincinnati in 1851 (Cincinnati,

1851), 233-234.

60 During the nineteenth century the

word "edition" was used loosely by Amer-

ican publishers. In this case the

term "third edition" may refer simply to the third lot

received from the binder.