Ohio History Journal

|

|

|

WILLIAM SANDERS SCARBOROUGH |

|

SCHOLARSHIP, THE NEGRO, RELIGION, AND POLITICS by FRANCIS P. WEISENBURGER During the years in which William Sanders Scarborough was professor and then president at Wilberforce University, his scholarly activities in the field of linguistics, his work and writings in the field of race relations, his con- tributions in the areas of religious journalism and church organization, and his varied public services were significant.* Each of these demands some consideration. As was previously pointed out, his textbook in elementary Greek was pub- lished in 1881. In July of the next year, the American Philological Associa- tion, meeting at Harvard University, elected him to membership.1 The death of his father in October 1883 and his own serious illness, as well as a lack of library facilities, impeded his research activities, but he was enabled to ob- NOTES ARE ON PAGES 85-88 |

26 OHIO HISTORY

tain research materials through the good

will of W. E. A. Axon of England,

one of the editors of the Manchester

Guardian. This enabled him to prepare

his first philological paper, "The

Theory and Function of the Thematic Vowel

in the Greek Verb," presented at

Dartmouth College, July 8, 1884.2 He had

journeyed there from the Cambridge,

Massachusetts, area on a special car

with Professor William W. Goodwin of

Harvard, president of the philo-

logical association; Sir Richard

Claverhouse Jebb of Glasgow University,

who had just given the commencement

address at Harvard; and other classi-

cal scholars.3 At Hanover,

New Hampshire, seat of Dartmouth College, he

was the guest of Henry E. Parker,

professor of Latin languages and litera-

ture, as were professors William Dwight

Whitney of Yale, Thomas D. Sey-

mour of Yale, and Tracy Peck of Yale.

Scarborough was flattered by two

incidents, a call from a Dartmouth

student who told him that he had used

the Scarborough text at Kimball Union

Academy, and an invitation to a

reception for members of the association

at the spacious summer home of

Herman Hitchcock, part owner of the

Fifth Avenue Hotel, New York City.

The meeting closed with a trip over Lake

Memphremagog in Canada. Scar-

borough believed that the meetings had

opened to him "a new world of

thought and endeavor," bringing to

him inspiration and intellectual com-

radeship.

At the meeting of the association at

Yale in July 1885 he read a paper,

"Fatalism in Homer and Virgil."4

In July 1886 he attended the annual

meeting at Cornell University, Ithaca,

New York, and that of July 1887

at the University of Vermont,

Burlington.5

At the time of his election to the

philological association, only two Negroes

had received such recognition--Dr. E. W.

Blyden, an African scholar and

linguist, in 1880, and Professor R. T.

Greener in 1881. During the next

generation few American Negroes were to

pursue advanced classical studies,

much to Scarborough's regret.

In the meantime, Scarborough had been

elected to the Modern Language

Association and to the American Spelling

Reform Association. In 1888 and

1889 he contributed to Education three

discussions of problems arising in

"The Teaching of the Classical

Language." One was based on the interpre-

tation of ancipiti in Caesar's Gallic

Wars.6 Another was "On the Accent and

Meaning of Arbutus."7 The

third was "Observations on the Fourth Eclogue

of Virgil."8 The last of

these had been prepared for presentation to the

American Philological Association

meeting at Amherst College in 1888.

Since Scarborough had been unable to

attend, the paper had been read by

Professor L. H. Elwell, professor of

Greek and Sanscrit at Amherst. In

WILLIAM SANDERS SCARBOROUGH 27

July 1889 Scarborough had journeyed to

Lafayette College to present a

paper on "Notes on Andocides."9

At the American Philological Association

meeting at Norwich Free Acad-

emy, Norwich, Connecticut, in July 1890,

a paper by Scarborough on "The

Negro Element in Fiction" was read

by title only, because of the author's

absence, but a summary was printed in

the Transactions of the association.10

In July 1891, at the meeting of the

association in Princeton, New Jersey, in

a discussion of "Bellerophon's

Letters," he sought to show that the art of

writing was not wholly unknown in

Homeric times, and that the word semata,

in relation to these records, might,

aside from its ordinary meaning (of

signs), also express the idea of written

characters, these epigramma being

real alphabetical characters. Because of

the lateness of the hour at the meet-

ing, his paper was presented by title

only but was printed in the publica-

tion of the association.11 In spite of

the loss of his professorship in 1892, he

and his wife strove to maintain his

professional contacts. Early in that year

he had published an article discussing

aspects of historical interpretation

found in Grote's History of Greece.12 During

the next year a paper on the

"Chronological Order of Plato's

Writings," originally presented to the

American Philological Association

meeting at the University of Virginia in

July, was published in Education.13 At

the meeting of the association in

Chicago in July 1893, he read a paper on

Plautus.14 When he journeyed to

Williams College in Massachusetts in

July 1894, to attend the meeting of

the philological association,

Scarborough arrived at midnight across the

river from the college. His color caused

him to be turned away from hotel

accommodations, so he had to spend the

night in a railroad tool shed. At

the meeting he read a paper showing that

in Greek and Latin the words

conveying the ideas of the three daily

meals, breakfast, dinner, and supper,

had variable meanings under different

circumstances.15

At the meeting of the association in

Cleveland in July 1895, he presented

a paper on "The Languages of

Africa."16 Similarly, at the annual meeting at

Providence, Rhode Island, in July 1896,

he discussed "The Functions of

Modern Languages in Africa."17

Two years later, at the regular meeting of

the association in Hartford,

Connecticut, in July 1898, he offered a paper,

"Iphigenia in Euripides and

Racine." It was read by title only and was

later published in the proceedings of

the organization.18 Afterwards, in ex-

panded form, it was published in Education

as two articles dealing with

"One Heroine--Three Poets:

Iphigenia As She Is Depicted by Euripides,

Racine, and Goethe."19

He also attended the annual meeting of

the association at Union College,

28 OHIO HISTORY

Schenectady, New York, in July 1902, and

read a paper on the use of certain

words in Demosthenes' De Corona.20

Because of his limited financial re-

sources he cut short his stay at the

meeting, but in spite of the drain on his

personal funds, he attended the next

annual meeting at Yale University in

July 1903. There he read a paper

entitled "Notes on Andocides and the

Authorship of the Oration Against

Alcibiades."21

In January 1907 he attended a joint

meeting of the eastern section of the

philological association and the

Archaeological Institute at Washington, D.C.

There he read a paper on "Notes on

Thucydides--Kateklasan," in which he

took exception to the translation made

by an English editor.22 In December

of the same year he offered a paper

which was read by title only at the

annual meeting of the association in

Chicago. It dealt with "The Greeks and

Suicide," and a summary of it was

published.23

He prepared a paper on "Notes on

Disputed Passages in Cicero's Letters"

for the annual association meeting at

Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore,

December 1909.24 The local committee on

arrangements belatedly found

that the headquarters hotel would not serve

dinner to Negro members of the

association, so he did not make the trip

to Baltimore, and his paper was

read by title only.

In December 1911 he attended the annual

meeting of the association at

Pittsburgh.25 There he

stopped at the Schenley House, a hotel which had

previously accepted only one Negro

guest--Booker T. Washington. A year

later he attended the joint meeting of

the association and the Archaeological

Institute at George Washington

University and at the Shoreham Hotel.26 He

was the house guest of friends but

attended a smoker at the hotel and a re-

ception at the home of Mrs. Charles

Foster, widow of an Ohio governor and

cabinet officer under Harrison. He met

Edward Everett Hale, then chaplain

of the United States Senate, who had

been an early trustee of Wilberforce.

In December 1913 he went to Harvard to

the association meeting, but for

some reason the program did not include

the paper on the word semeion

which he had prepared for presentation.27

Duties at Wilberforce commanded

his attention so that he did not attend

the national philological meetings in

1914 and 1915 but went to St. Louis for

the sessions in 1916.28 In 1921 he

journeyed to England and represented the

American Philological Association

at the Classical Association meeting at

Cambridge University.

Thus over a period of almost forty years

Scarborough eagerly and even

aggressively pursued his efforts in the

field of classical philology. He, more-

over, was also active both as a writer

and a public speaker in the further-

ance of improved race relations. He had

performed some service in this re-

|

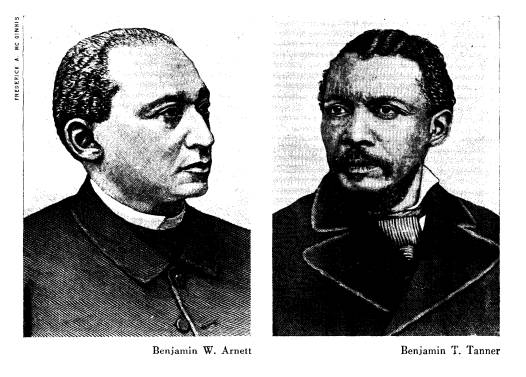

WILLIAM SANDERS SCARBOROUGH 29 spect as a young man teaching in Georgia, but naturally he took more active leadership after joining the faculty of Wilberforce. Some of these efforts will be discussed later as attention is given to his leadership in the Repub- lican party of Ohio. He was an influential figure in securing the elimination of the legal segre- gation of the Negro in the schools of Ohio. The Rev. Benjamin W. Arnett, whose home was at Wilberforce and who in May 1888 was to become a bishop of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, was elected to the Ohio legislature from Greene County in 1886.29 He there became a joint sponsor of the Ely-Arnett bill, which outlawed public school segregation in Ohio.30 The passage of the bill was celebrated with various jubilee meetings, in- cluding one at Springfield, Ohio, February 28, when a crowd of 1,800 at- tended, and Scarborough was seated on the stage.31 Another one in which Scarborough also participated was held at the city hall in Columbus, March 16. The year 1888 marked the centennial of the institution of organized gov- ernment in the Northwest Territory with slavery excluded. Accordingly, a Centennial Jubilee of Freedom was held in Columbus, September 22. There, in the midst of a long oration, Bishop Arnett referred to Scarborough as "one of the most distinguished young men of the race."32 |

|

|

30 OHIO HISTORY

During this period the noted novelist of

Louisiana Creole life, George

W. Cable, became increasingly concerned

to secure a constructive airing of

the Negro problem through articles in

leading American magazines.33 In

1888 he had asked Bishop B. T. Tanner to

recommend the best qualified

persons for such a task. As a result,

Scarborough contributed an article to

the Forum, March 1889, on

"The Future of the Negro." He contended that

the South feared "not condition,

but color; not loss of 'political integrity,'

but of political power" and that,

if the South did not produce a settlement of

these problems, the Negro would have to

leave the South.34 Scarborough also

contributed articles on the Negro

question to the New York Tribune and

other papers.

During these years Booker T. Washington,

with his program of industrial

education at Tuskegee Institute strongly

supported by leading philanthro-

pists, was receiving wide acclaim. Some

earnest advocates of Negro rights

believed that, by his emphasis on the

manual arts, Washington was really

aiding the cause of southern

conservatives. During 1890 various views of

the American Negro's prospects were

aired in another leading periodical,

the Arena. William C. P.

Breckinridge, congressman from Kentucky, de-

nounced outside interference in working

out a solution to the "Race Ques-

tion."35 Senator Wade

Hampton of South Carolina, in another article,36 even

indicated what he thought were the

merits of "revoking Negro citizenship,"

but deeming such a course impracticable,

he contemplated the desirability of

deporting the Negroes by voluntary

consent.37 Scarborough, writing in the

same magazine, contended that the Negro

problem was really the white

man's problem, for the white man, not

the Negro, asserted claims of race

supremacy. Scarborough held that the

solution for North and South, white

and black, was to unite on principles of

justice and humanity.38

During the next year he contributed

another article to the Arena on "The

Negro Question from the Negro's Point of

View." He maintained that the

white man did not understand the Negro

and that some white writers tried

to show the Negro to be incapable of

self-government or advanced education,

a viewpoint which Scarborough deemed

"preposterous."39 Some years later

he developed his views further in an

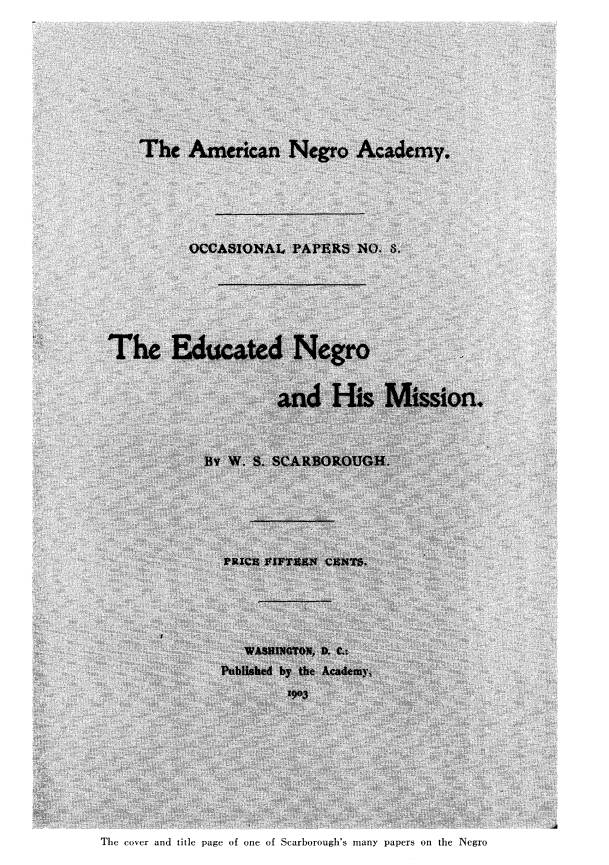

article in the Forum on "The Educated

Negro and Menial Pursuits." He

raised the question why the Negro should

be given "a pick instead of Greek

and Latin." His answer was that life

should be ennobled for the Negro as well

as for the white man, even in

menial positions, hence all avenues of

life's higher activities should be

opened to him.40 He

elaborated further on this viewpoint in an article in

Education in January 1900. Asserting that Booker T. Washington

served

WILLIAM SANDERS SCARBOROUGH 31

as "a needed leader" in Negro

industrial education, he added, "But this

is not saying that because of his

success in this line all the race must run mad

over industrial education."41

Scarborough expressed similar views in a

review of Washington's The

Future of the American Negro (Boston, 1899) for the Annals of the Amer-

ican Academy of Political and Social

Science.42 Thus, at least a

distinct

difference in emphasis between the two

trends of Negro education was indi-

cated.43 Yet Scarborough and

Washington remained good friends, and their

differences may have been in part a

question of the best method of dealing

publicly with the race problem, when any

ideal solution was beyond the

range of immediate fulfilment.44

As we have seen, Scarborough's interests

in race matters were sometimes

closely intertwined with his linguistic

concerns. Another example of this

was when, on his first visit to Hampton

Institute in Virginia, he presented, at

a conference there, a paper on "The

Negro in Fiction as Portrayer and Por-

trayed." In this he took issue with

the way in which the Negro dialect was

being presented in the current books of

the time.45

In May 1891 he had unexpectedly become

the subject of a controversy

over race discrimination when, without

informing him, his Oberlin class-

mate, W. H. Tibbals, then a professor at

Park College, Missouri, presented

his name for membership in the Western

Authors and Artists Club in Kansas

City, Missouri. Tibbals pointed out

Scarborough's contributions to national

magazines and to the field of philology,

but after heated discussion, admis-

sion was denied to Scarborough. Some

believed that the incident was a

scheme to use a prominent Negro to

advertise a little-known organization,

but Tibbals wrote that he did it

"to test the Club."46

Negro leaders wished that their race

might receive proper attention at

various world expositions, including the

World's Columbian Exposition in

Chicago in 1893. Thereupon, a World's

Congress Committee was established,

and eventually an Ethnological Congress

was held in connection with the

exposition. Scarborough was active in

the deliberations which led to the

holding of the congress. Once again his

racial, philological, and ecclesias-

tical interests intertwined, as he was

asked to prepare a paper on the "Func-

tion and Future of Foreign Languages in

Africa," to show what would be

the effect of modern European languages

upon native African tongues. He

consulted competent authorities in the

preparation of the paper, which was

of interest to those concerned with the

missionary movement and which was

later published in the Methodist

Review.47

Scarborough had also participated in the

interfaith parley, the Parlia-

32 OHIO HISTORY

ment of Religions at the Columbian

Exposition.48 There he read a paper

prepared by Bishop Tanner, who was

absent because of illness, on "Afro-

American Journalism." The

exposition brought new opportunities to Scar-

borough, as he became acquainted with

Heli Chatelain, the French explorer,

and Paul Laurence Dunbar, who was then

seeking the publication of his

poems. He also had further contacts with

Frederick Douglass and was once

more impressed by "his massive

frame, leonic head, firm tread."

Following the same line of interwoven

interests in 1897, he contributed

an article, "Negro Folk-Lore and

Dialect," to the Arena.49 Dealing with

broader themes in the same journal in

1900, he contended that much of the

lawlessness among Negroes could be

explained by the attitude of whites

toward them. He elaborated:

When the American people, North and

South, come to realize the fact that

violence begets violence, and that no

people can be safe where law is ignored or

disregarded on the merest pretense, then

perhaps we may look for a better state

of things than can possibly exist under

present conditions.50

In 1901 Scarborough made a trip abroad,

and upon his return he hastened

to Ohio, for he was scheduled to attend

a meeting of the Afro-American

League of Ohio, of which he was

president. The organization had been estab-

lished to advance Negro rights. Just

then it was striving to prevent Jim Crow

railroad cars from entering Cincinnati

from Kentucky. The effort was suc-

cessful, with the assistance of legal

advisors, of whom Senator Joseph B.

Foraker was the most influential.

Scarborough contributed to the Manchester

Guardian, the London Times,

and various African publications,

including Izwi-La-bantu, "The Voice of the

People," a Cape Colony paper.

Scarborough joined William E. B. Du Bois,

the aggressive Negro leader, in

presenting arguments in the latter paper that

were at variance with the principles of

Booker T. Washington.

With the expansion of the United States

into Hawaii, Puerto Rico, and

the Philippines, he insisted that new

fields were being opened in those areas,

where, for example, the Negro might be

used as a teacher. He, moreover,

continued to contend that Negro

education should not be limited to industrial

training, for only through higher

education could the Negro achieve the

highest honor and respect.51

He gave talks during this period at

Hampton Institute on "The Negro as

a Factor in Business," "The

Negro's Duty to Himself," and "Co-operative

Essentials to Race Unity." He also

went to Boston to make an address on

"The Negro Scholar and His

Mission." In the summer of 1902 he spoke

34 OHIO HISTORY

before an educational mass meeting in

Columbus, Ohio, on the question,

"What Is the Colored Race Doing to

Advance Itself Educationally and What

Does It Contribute Yearly in a Financial

Way to the School Fund?" In

April 1904 he addressed a meeting in

Baltimore of the presidents and other

representatives of the agricultural and

mechanical schools devoted to Negro

education, speaking on "The Negro

College." In August he spoke before

the Negro Teachers of the United States,

meeting at Nashville. In May 1906

he went to Tuskegee Institute for the

twenty-fifth anniversary celebration of

the founding of the school.52 In

July he gave the commencement address at

Kentucky Normal and Industrial

Institute, and he also went to Detroit to

address the National Afro-American

Council on the subject, "How Shall We

Reach and Improve the Criminal

Classes?"53

In late July and in August he was in the

East, taking part in the program

of the Negro Young People's Christian

and Educational Congress in Wash-

ington, D.C., and speaking before the

Educational and Ministerial Chautau-

qua in Atlantic City, New Jersey, and at

"Mother Bethel" A.M.E. Church in

Philadelphia.

During this period Ray Stannard Baker

visited Wilberforce to gather ma-

terial for a series of articles to

appear in the American Magazine on the race

question in the United States.54 These

were later brought together in the

volume, Following the Color Line. Scarborough

reacted somewhat unfavor-

ably to the author's appraisals, writing

later in his autobiography:

Like many others who seek to know race

life from the inside in a few hours'

visitation, he failed to get fully into

the heart of things, generalizing from too

few particulars, and like many who

interview our people he learned only what

the few interviewed chose that he should

learn. When the Negro chooses he can

be as non-committal as any race.

Scarborough was persuaded to deliver the

commencement address at

Atlanta University, May 28, 1908,

speaking on "The Mission of the Negro

Graduate." As Atlanta University's

first graduate, he indulged in poignant

reminiscences. Then he discussed

"Education and Usefulness," "Acquire-

ments Expected," the "Mission

and Boundless Opportunity for Service," the

"Importance of Versatility,"

and the "Need for Toil and Sacrifice." His

closing remarks included the charge:

Go forth with a fixed determination that

you will make your service tell on

your day and generation. Act wisely,

cultivate tolerance and forebearance, while

not abating your manliness; make

friends, but do your duty regardless of ene-

mies; teach all duties and condemn all

vices.

WILLIAM SANDERS SCARBOROUGH 35

In February 1909 he gave the oration in

Brooklyn, New York, at a celebra-

tion arranged by Negro citizens in honor

of the centennial of the birth of

Abraham Lincoln. Later in the year he

was the orator of the day at the un-

veiling of a monument to Paul Laurence

Dunbar in Woodlawn Cemetery,

Dayton, Ohio.

In March 1910 he went to Nashville for

the inauguration of President

George A. Gates at Fisk University.

After commencement of the next year

his wife and he made their second trip

abroad, this time to attend the First

Universal Races Congress at the

University of London during the last week

of July. The meetings were aimed at

fostering better race relations through-

out the world.55 With various

other delegates they sailed on the Carmania

and were delighted to meet on the boat

Albert Bigelow Paine, Mark Twain's

biographer, and other notables. Leaving

the boat at the new port, Fishguard,

they journeyed to London through Wales

and again stopped at the palatial

St. Ermin's Hotel. At the meetings of

the congress sixty-two nationalities

were represented. Distinguished scholars

took part in emphasizing the unity

of the human race. A former president of

Haiti presided at the session at

which Scarborough addressed the congress

on "The Color Question in the

United States." Receptions in

London, luncheon and tea at Warwick Castle,

and a day at Cambridge University were

followed by a short trip to the

continent. Sightseeing in Paris and a

boat trip from Cologne to Strassburg

brought fearsome impressions of the

extent to which the war spirit was in

the air following the Algeciras

incident.

Returning to London, they found Victoria

Station deserted because of the

great strike. Visiting for some days in

the suburbs and in Manchester, at

last they sailed from Liverpool, once

again on the Carmania. At Halifax,

where recoaling became necessary, some

damage was done to the vessel in

entering the small harbor, but after

several days' delay, the ship proceeded

to New York.

Early in 1912 he contributed an article

to the African Times and Orient

Review. In July he went as a delegate to the Negro National

Educational

Conference in St. Paul by appointment of

Governor Judson Harmon. In

September he attended the congress held

in Philadelphia under the auspices

of the Emancipation Commission of

Pennsylvania. In December he went to

the inauguration of Dr. Stephen Newman

as president of Howard University

and was one of five university

presidents to deliver an address at the trustees'

reception.

In 1914 he lectured in Boston before a

Negro society, the St. Mark

Musical and Literary Union. In August of

that year he gave the address of

36 OHIO HISTORY

welcome to five hundred persons in

attendance at the Colored Women's Fed-

eration at Wilberforce. In September he

went to Passaic, New Jersey, to

lecture on "Education" at the

Bethel A.M.E. Church.

In 1915 he was a delegate from Ohio to a

meeting in Chicago celebrating

the Half Century Anniversary of Freedom.

During the summer he journeyed

to California, where he was given a

rousing reception by the Los Angeles

branch of the National Association for

the Advancement of Colored People.

In the summer of the next year,

following the death of William Hayes

Ward, the founding editor of the Independent,

Scarborough was asked by

Hamilton Holt, the editor, to join

Washington Gladden, Bliss Carman, and

others in tributes to Ward. Asked to

give an appreciation of Ward's devotion

to the Negro, Scarborough wrote in part:

Proscription, segregation, mob violence,

lynchings, denial of vote, all race

distinctions, all the thousand and one

indignities, persecutions and cruelties and

crimes against the negro wherever

practised, have found in him one who de-

nounced vigorously and unsparingly all

such as unlawful, unjust, unchristian

and inhuman. His work did not stop with

his strenuous endeavors to right the

wrongs done the negro, but he maintained

that the education of the race should

be of the highest type; . . . and

encouraged all its ambitions and aspirations as

a people.56

Late in the year, Scarborough went to

Durham, North Carolina, to a con-

ference on the "Progress of Negro

Education." Held at Professor W. G.

Pearson's Training School the conference

included in its program an address

by Scarborough on "What Should Be

the Standard of the University, College,

Normal School, Teacher Training and

Secondary Schools?"

As president of Wilberforce, Scarborough

encouraged friendly relations

between the races, so an athletic team

from the Chinese University at Hono-

lulu was invited to play at Wilberforce.

Although having a record of sixty-

five consecutive victories, the Chinese

team was defeated at Wilberforce.

Scarborough later recalled that

Wilberforce teams often played against

white teams "with the best of good

feeling." During this period he accepted

membership on a Provisional Jewish

Committee, concerned with stamping out

racial injustice and persecutions.

Almost on the eve of the entry of the

United States into World War I,

Scarborough journeyed to Washington,

D.C., where he participated in the

fiftieth anniversary celebration of the

founding of Howard University.57

In July 1917 he addressed the

Association of Teachers of Colored Schools

at Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, on

"Negro Colleges and the War," and in

the fall he went as a delegate,

appointed by Governor James M. Cox of Ohio,

WILLIAM SANDERS SCARBOROUGH 37

to the Negro National Educational

Congress in New York City. During the

first half of 1918, as a prominent Negro

leader, he attended a wide variety

of meetings, where he was sometimes the

speaker, in Washington, D.C.,

Philadelphia, and Columbus, and in

Kentucky at Frankfort, Lexington, and

Harrodsburg.

During the war Scarborough was not

inarticulate, as he felt that an injus-

tice had been done to numerous Negro

servicemen in the lamentable delay

in the delivery of officers' commissions

to them. He reacted vigorously also

when, upon demobilization, Negro

soldiers often experienced fresh evidences

of intolerance.

After the war came to an end, a repressive

spirit of nationalism and racism

expressed itself. In Ohio, some had

endeavored to put new restrictive "Black

Laws" on the statute books, and a

revived Ku Klux Klan incited hatred.58

Scarborough, as a noted representative

of Negro Americans, spoke out in

defense of them. He asserted, in part:

There is but one remedy for race riots,

and that is justice--a willingness to

accord to every man his rights--civil

and political.

The Negro is law-abiding and only

occasionally shows a retaliatory spirit....

Negroes are not rioters, but can be made

so. It is a heavy burden they carry.59

As will be discussed later, in the fall

of 1921 Scarborough went to

Europe to the Methodist ecumenical

conference. While in Great Britain

he told a reporter on one occasion:

We [Negroes], like other peoples, have

our radicals. We have those who believe

in force as a means of progress. I am

not among these. Interracial, like interna-

tional, questions, I think, must be

settled, if ever really settled, not by violence,

but by reason....

In the principle of Africa for Africans

I believe, but . . . I am convinced that

any progress toward realization of the

ideal of Africa for the Africans can be

achieved only slowly and by the use of

the weapons of mind and soul.

Later, as will be discussed

subsequently, Scarborough contributed to an

understanding of Negro problems as he

worked in the United States Depart-

ment of Agriculture. Now, however, we

turn our attention to his long and

diversified efforts as a leader in one

of the largest denominations of Negroes

in the United States, the African

Methodist Episcopal Church.

In December 1882 the Sunday School Union

of the African Methodist

Episcopal Church was established, and

Scarborough became a contributing

editor to its publications. In addition

to the denominational paper the Chris-

tian Recorder, the A.M.E. Review was also established in order

to develop

30 OHIO HISTORY

literary expression in the denomination.

Scarborough contributed an article

on "The Greek of the New

Testament" to the first issue.60 Later, he was the

author of several articles--"On

Fatalism in Homer and Virgil" (previously

read at Yale University),61 "The

New College Fetich" (electives as a detri-

ment to the study of the classics),62

and "The Roman Cena"63--and a review

of Bishop Benjamin T. Tanner's Dispensations

in the History of the Church.64

During the 1890's with the establishment

of the Payne Theological Semi-

nary, the faculty of the school was used

to prepare the Sunday School

teachers' guide to the International

Sunday School lessons. Called the A.M.E.

Zion Quarterly and published at Nashville, Tennessee, it was a booklet

of

about thirty-six pages. At first the

work was done by President Samuel T.

Mitchell, Professor C. W. Prioleau, and

Scarborough, but Mitchell soon

turned his part of the work over to

Scarborough, as did Prioleau also when

he resigned from the faculty in 1895

(later becoming a United States Army

chaplain).

As an A.M.E. churchman, Scarborough,

along with Bishop Arnett and

others, was a delegate to the Third

Methodist Ecumenical Conference in

London in 1901.65 Negro transatlantic

travelers then seemed to be something

of a novelty. Sailing from New York,

they landed at Queenstown and pro-

ceeded to Liverpool. There they were assisted

by James Boyle, American

consul, who had been well known to

Scarborough and Arnett when he had

been secretary to President McKinley.

Going on to London, they were met

by Bishop Tanner's son, the artist Henry

Ossawa Tanner, who had come over

from Paris.66

Having decided upon a trip to Rome

before the conference opened, they

crossed the English channel to Dieppe.

Many passengers became seasick,

but Professor and Mrs. Scarborough stood

on the narrow deck passage and

faced the waves throughout the trip.

After a pleasant trip through Normandy

they stopped at the Grand Hotel in

Paris. The younger Tanner conducted

them on a sightseeing tour, and they

visited the Louvre, where one of his

paintings was on exhibition. They visited

Tanner's own studio in the Latin

Quarter. In view of his specilization in

Biblical scenes, Tanner had pur-

chased, at the death of the noted

Hungarian painter Mihaly Munkacsy, all

of his Oriental costumes.67

In Paris and throughout Italy no race

discrimination was noted in the

hotels, cafes, and concert halls.

Scarborough later commented, "Even the

American tourists there took only a

languid interest in our pigmentation, and

a young man from New Hampshire greeted

us in Switzerland as long lost

relatives so happy was he to hear the

sound of our English tongue." From

WILLIAM SANDERS SCARBOROUGH 39

Paris the Scarboroughs with Bishop W. B.

Derrick traveled through southern

France and through the Mont Cenis tunnel

to Turin and Rome. Everywhere

Scarborough's interest in both the

classical and the Christian traditions was

excited by the many monuments of ancient

culture.

When they returned to London they found

that some Americans at their

hotel had demanded that the Negro guests

be ejected, but the manager

refused to comply.

At the ecumenical conference every phase

of the ecclesiastical and social

work of Methodism was discussed. One

morning the delegates heard the

startling news of the assassination of

President McKinley.

After the conference, sightseeing tours

of England and Scotland were fol-

lowed by a journey to Manchester and

Liverpool. Then they sailed for New

York on the Cunard liner Umbria.

Scarborough's relations with the African

Methodist Episcopal Church were

closely associated from 1908 to 1920

with his duties as president of a

church-affiliated university,

Wilberforce. Thus, in January 1912, he jour-

neyed to Atlanta to pay his respects at

the funeral of his lifelong friend

Bishop Wesley J. Gaines. Several years

later he returned to Atlanta for the

inauguration of Dr. Philip M. Watters as

president of Gammon Theological

Seminary. His duties involved attendance

at general conferences of the

African Methodist Episcopal Church,

including that held in Philadelphia

in 1916.

In December 1919 he participated in a

meeting of the Interchurch World

Movement in New York City. In 1921 he

was one of a group of Negro Amer-

icans to go to Europe to attend another

Methodist ecumenical conference,

meeting in September. He, however, went

in advance of the rest of the party,

for he was to represent the American

Philological Association at a meeting

in Cambridge, England. At the last

minute Mrs. Scarborough could not ac-

company him, owing to illness in her

family. He sailed July 16, on the

Carmania, on which his wife and he had sailed in 1911. The voyage

was

rather lonely for him this time, but he

found companionship with another

lonely individual, a young Japanese

chemist en route to enter business in

Bombay. Having arrived at Liverpool on

July 23, he took a train for Edin-

burgh. He spent a day in the lovely

highland lake country.

At the end of July he was in London,

stopping at the Hotel Cecil. Then he

went to the meeting at Cambridge, that

of Anglo-American classicists. A wide

variety of scholarly papers, concerts, a

visit to Ely Cathedral, and a number

of receptions occupied his time for some

days. He then revisited Oxford and

went on to Stratford-on-Avon. On August

18, with other delegates, he went to

40 OHIO HISTORY

Southampton and across the channel to

Cherbourg, where he met those who

were arriving to attend the Methodist

conference. Going on to Paris, they

visited Versailles, made a tour of the

war zone, and saw the war-damaged

Rheims Cathedral. Going by train to

Rome, they later visited Florence,

Venice, and Milan. Returning by way of

Switzerland to Paris, they went on

to Brussels and the Waterloo battlefield.

Reaching Ostend, they crossed the

channel and went on to London by rail.

There, on September 6, the ecumenical

conference opened in City Roads

Chapel, with later general sessions in

the new Central Hall. The emphasis

was on brotherhood. One Sunday Scarborough

addressed two church meet-

ings.

After the conference he visited friends

in Paris and returned to London

before sailing from Southampton, October

21, on the Adriatic. The voyage

was without noteworthy incident, and he

proceeded then by rail to his home

in Ohio.

We now turn to a consideration of

Scarborough's influential career in the

field of politics. As a young man he had

been a delegate to the Republican

state convention at Atlanta. As he

settled down at Wilberforce to become an

influential Negro leader, he soon took

an important part in providing guid-

ance for the Negro constituency in the

Republican party in Ohio. In 1879

he had actively sought the gubernatorial

nomination for Alphonso Taft of

Cincinnati when the position had gone to

Charles Foster of Fostoria, who was

elected.68 During this period much

dissatisfaction existed among the Negroes

of Ohio with the attitude of the

Republican party toward Negro rights.69 Scar-

borough made an address on "Our

Political Status" at an interstate Negro

convention in Pittsburgh, decrying the

way in which Negro rights were being

trampled under foot.70 Recalling

the Civil War heroism of the Negro at Fort

Wagner, Milliken's Bend, Port Hudson,

and Fort Pillow, he appealed for

full civil and political rights for the

colored man. He regretted the supine

attitude of conciliation on the part of

the Republican party, but saw no hope

for the Negro in supporting independents

or the Democrats. He called upon

his race to present "a united

front" and urged the presentation of a compre-

hensive petition of its grievances to

the Republican national convention at

Chicago in June 1884. He denounced

prejudice that could not rise above the

"infamous color-line" and

advocated mixed churches and integration in

other phases of American life.71

At the Republican national convention of

1884 the Negro's strength was

recognized by the choice of John R.

Lynch, a prominent Mississippi Negro,

over Senator Powell Clayton, a white man

from Arkansas, as temporary

WILLIAM SANDERS SCARBOROUGH 41

chairman.72 In the

convention Scarborough believed that Foraker was

thoroughly loyal to Senator John

Sherman. Scarborough had written an arti-

cle for the Chicago Tribune favoring

Sherman, but that paper refused to

print it, for it deemed "Sherman

the very man whose nomination would place

the Republicans on the defensive and

keep them there until the election is

over." Whitelaw Reid apparently

held similar views, for he wrote Scar-

borough after Cleveland's election in

1884 that he considered that Blaine

was "our best candidate and had no

doubt that he would have been elected

by a handsome majority, but for the

Burchard Incident. . . . I should have

been perfectly satisfied, however, with

Sherman as a candidate, but would

have expected a harder contest for him

in New York than we had with

Blaine." In this campaign

Scarborough used his utmost efforts for Blaine.73

During the gubernatorial campaign of

1885 in Ohio, the Republicans de-

manded a "free ballot and fair

count." Foraker, again running for the gov-

ernorship (after his defeat of 1883),

spoke in June at Wilberforce, denying

charges that he was unfavorable to the

Negro. Protesting against limiting

the Negro to utilitarian activities, he

asserted that "nothing was so well cal-

culated to strengthen the mind and give

one the power of analysis as a

study of ancient languages."

Scarborough believed that Foraker's election

in 1885 "was a fortunate event for

the race," in spite of the favorable atti-

tude toward the Negro of George Hoadly,

the Democratic nominee.74

On February 13, 1888, Scarborough was

the only Negro among twelve

speakers who responded to toasts at the

first Lincoln Day banquet of the

Ohio Republican League, an occasion

arranged to help create political en-

thusiasm in the state.75 Scarborough

responded to the toast, "Why I am a

Republican." He declared that

among other reasons he adhered to the party

of Lincoln "because to make

political alliance elsewhere would be to prove

myself the veriest ingrate that ever

trod this green earth, the meanest pol-

troon that ever exhibited his moral

weakness to the gaze of the public--

deserved to be hissed and spit upon by

those I had deserted, and treated like

a fawning cur."76

Scarborough's success on this occasion

led to his going to Chicago to

work for the nomination of John Sherman

for the presidency. Scarborough

later asserted that he believed that

Foraker "stood by Sherman loyally and

faithfully as long as possible; and

turned to Harrison only when the use-

lessness of continued support of Ohio's

first choice was plainly evident."

Scarborough felt that his own course

was much the same. Earlier he had

always found Sherman "approachable

and sympathetic," but after the con-

vention he "noticed a perceptible

coolness in his friendship."

42 OHIO HISTORY

Following the nomination of Harrison, it

was widely believed that the

Negro vote might be decisive in the

campaign. At first it was thought that a

Negro convention would best serve to

rally the Negro voters, but finally an

"Address to Colored Citizens,"

signed by well-known Negro citizens was

deemed the best way to influence the

largest number of voters. In response

to a letter from Frederick Douglass,

dated Cedar Hill, Anacostia, D.C.,

September 8, 1888, Scarborough visited

Douglass, and the two prepared a

five-column appeal to Negro voters,

which was signed by prominent Negro

leaders and was widely distributed

before the election.77 Scarborough exerted

strong personal efforts during the

campaign, and after the election received

a personal letter of thanks from

Harrison.78

At the second annual banquet of the Ohio

Republican League in Columbus,

February 12, 1889, Scarborough

substituted for the distinguished John H.

Langston, who had been scheduled to

respond to the toast, "The Colored

Man in Politics."79

Scarborough's political activities had

brought him into close touch with

political leaders of both parties in

Ohio, among them William McKinley,

Benjamin Butterworth, Charles H.

Grosvenor, Joseph Warren Keifer, Asa

Bushnell, Charles Kurtz, and Judson

Harmon. He had been especially close

to Governor Foraker, who believed that

his own defeat for a third term was

due to the fact that "he had gone

to the well once too often." To some extent

Scarborough felt that he had gone down

politically with Foraker's defeat,

and he began to give more time to his

literary work and to the advancement

of Wilberforce.

Yet he had developed a growing ambition

and, to some extent, a desire

for a change and looked to Haiti with

its language and folklore as a field

for the philologist. His Republican

connections prompted him to seek the

post of minister to Haiti, following

Frederick Douglass' retirement in 1891.80

Foraker dispatched highly complimentary

letters of endorsement to Presi-

dent Harrison and to Secretary of State

James G. Blaine. To the latter, he

wrote in part: "Professor

Scarborough is one of the best representatives of

his race in point of ability and

character that I have ever known." Scar-

borough personally called on the new

postmaster general, John Wanamaker

of Philadelphia, who, it was later

revealed, was supporting John S. Dunham,

a Negro of his home city, for the

position. Wanamaker endeavored to dis-

courage Scarborough in his quest by

voicing his belief that the coveted ap-

pointment would offer far less

opportunity than he had as an educator of

youth, a view similar to that taken by

some others. There were, at any rate,

geographical as well as political

impediments to Scarborough's appointment.

WILLIAM SANDERS SCARBOROUGH 43

At first, Blaine, who wanted a white man

in the position, objected to Dunham

as too young and too inexperienced, but

eventually he came to believe that

the appointment would save Harrison

"the annoyance of a half hundred

colored men" in an enraged quarrel

for the place.81 Dunham received the

position. Charles Foster, now secretary

of the treasury, suggested that Scar-

borough take the post of Liberian

minister or consul general in Santo

Domingo. Scarborough thought these would

not contribute to his literary

advancement, as the mission to Haiti

would have done, and he declined to

be considered for them.

In the summer of 1892 James S. Clarkson

of the Republican national

committee wrote to Scarborough

indicating that he was recommending that

he be employed to make ten campaign

speeches. Scarborough later asserted

that he had charged $700 for these

oratorical efforts.82

In 1897 Scarborough once again sought

the Haitian post in the diplomatic

service. In February he went to a

Lincoln Day banquet at Zanesville that

was addressed by Booker T. Washington.

After it a pilgrimage was made to

call on President-elect McKinley. Washington

took the opportunity to urge

the appointment of Scarborough to Haiti.

Afterwards, the president-elect

detained Scarborough for a private talk,

emphasizing his desire to see Mark

Hanna chosen to Sherman's senatorial

seat. But Scarborough did not re-

ceive the Haitian post.83

In the meantime he had taken some part

in Republican politics, but was

distressed by the bitter factionalism in

the party. He manifested great inter-

est in advancing the political fortunes

of Warren C. Harding, who was

elected state senator in 1899, and he

campaigned actively for Myron T.

Herrick, who was elected governor in

1903.

In February 1904 he attended the annual

Republican Lincoln Day banquet

at the Hotel Hollenden in Cleveland.

This being a presidential year, politics

demanded his attention, as his services

were again sought by Republican

leaders. By request, in October he sent

out "An Appeal to the Colored

Voters," in a circular in which he

asserted that the "election was to be by

all odds the most important since the Rebellion."

There had been much ado

North and South over the fact that

President Roosevelt had entertained

Booker T. Washington at dinner in the

White House, October 16, 1901.84

Scarborough now called on his fellow

Negroes to vote for Roosevelt, "who

had the courage to recognize merit and

manhood irrespective of class or con-

dition," and to vote against such

men as Congressman J. Thomas Heflin of

Alabama, who allegedly had declared that

Roosevelt "should have had a

bomb thrown under his table."

44 OHIO HISTORY

In 1905 he campaigned actively for the

reelection of the Republican gov-

ernor, Myron T. Herrick. He told the

colored voters that the issue was "not

a local one, not merely a state one, but

to all intents and purpose, national

in its scope." But Herrick was

defeated by the Democratic candidate, John

M. Pattison.85

In January 1907 Scarborough attended a

joint meeting of philologists and

archaeologists in Washington, D.C. At

this time members of the association

were received by President Roosevelt in

the Blue Room of the White House.

Scarborough later recalled:

I was midway in the line. When President

Roosevelt saw me his eyes twinkled.

He showed both surprise and delight at

my presence in such a body. He greeted

me heartily and asked me to remain,

saying he desired to speak with me when

the others had withdrawn. I did so and

he asked me to call the following day as

he had something of importance to say to

me in regard to the position he had

in mind.

Scarborough later learned that the

president had been so impressed by the

Ohioan's presence in such a

distinguished body that he sensed the possibility

of appointing him to a high place so as

to mollify Negro opinion.

Scarborough, like other Negroes, had

recently been most resentful of

Roosevelt's action in dismissing

"without honor" 270 Negro infantrymen

because of the so-called Brownsville

affair in Texas. But Scarborough did

not have the further interview with the

president, for the next morning he

received a letter from Roosevelt's

secretary saying that the president would

not take up the matter with Scarborough

at least for the time being. Scar-

borough afterwards believed that another

Ohioan had indicated that Scar-

borough was an "out and out Foraker

man," a fact which would have made

him persona non grata at the

time, for Roosevelt and Foraker had contended

violently over the Brownsville affair.86

Scarborough later asserted that his

relations with Foraker were closer than

with any other public man of the

time, except Warren C. Harding, and many

letters were exchanged between

them on political matters.

Scarborough had been consulted on

numerous occasions regarding the

appointment of Negroes by governors of

Ohio to positions of responsibility.

Following the death of Governor John M.

Pattison in 1905, Lieutenant

Governor Andrew L. Harris succeeded to

the post of chief executive. At one

time, Harris sent for Scarborough to

help him select a Democrat for the

state board at Wilberforce University.

Scarborough suggested Common

Pleas Judge Madison W. Beacom of

Cleveland, an Oberlin graduate of the

WILLIAM SANDERS SCARBOROUGH 45

class of 1879. Harris asked Scarborough

to go to Cleveland to see whether

Beacom would accept, and the result was

Beacom's appointment.87

In general in Ohio the Republican party

was more closely associated with

the prohibition movement than the

Democrats, so in the spring of 1908,

both as a churchman and a Republican,

Scarborough was glad to issue an

appeal to Negro citizens of Ohio to vote

against home rule on the liquor

question--desired by the saloon

interests--and in favor of statewide prohi-

bition. Similarly, in 1916, when Myron

T. Herrick, former Republican

governor, sought a senate seat from

Ohio, Scarborough issued a special

appeal to the Negro voters in his

behalf.

In the meantime, in 1908, when the

Republican national campaign opened

in Youngstown, Ohio, Scarborough

accepted an invitation to be present.

There he found that the program listed

him not only as president of Wilber-

force but with "Reverend"

before his name. He was scheduled to give the

invocation and did so, even though he

was a layman. Subsequently, he

exerted his best efforts to

advance the presidential candidacy of Taft in

that year.

Scarborough was especially active in

Republican politics during 1920.

At the Republican national convention in

Chicago in June, Frank B. Willis

had made the speech which had placed

Harding in nomination. After

Harding's selection as the party

standard-bearer, Willis became a candidate

for the senatorial seat occupied by

Harding, but Walter F. Brown of Toledo

and R. M. Wanamaker also entered the

contest.88 Brown was a former "Bull

Mooser" of 1912 and did not have

the support of various leaders of the

Republican machine. Maurice Maschke of

Cleveland wrote Scarborough in

July, urging him to work in Clark,

Creene, and Madison counties "and a

little in Highland," and offering

him fifty dollars a week and traveling ex-

penses until the close of the primaries

in August.89 Willis won the contest.

Scarborough had worked so effectively

that Willis wrote him, "You and

your friends certainly rallied to my

support in great shape."90

In the subsequent race between Willis

and the Democratic candidate,

W. A. Julian of Cincinnati, Scarborough

again worked vigorously for Willis,

and once again received profuse thanks

when Willis won the election.91 Scar-

borough had campaigned for the

Republican ticket as a whole and received

a letter of appreciation from Harry S.

New of the Republican national com-

mittee after the close of the

campaign.92

Because of his efforts in the campaign

and in view of his loss of the

position of president of Wilberforce,

Scarborough eagerly sought a govern-

ment appointment in Washington. He was

summoned to Washington to report

46 OHIO HISTORY

to the veterans' bureau, but an

appointment in that bureau did not material-

ize. Apparently at that time the

appointment of a Negro to a responsible

position was fraught with difficulties.

Finally, a position at $250 a month

as assistant in farm studies in the

department of agriculture was secured

beginning November 1, 1921, and was

continued on a three-months basis,

the appointment being renewed at the end

of the period.93 His task was to

assist in providing information which,

published in bulletins, might aid

Negro farmers. He expressed to President

Harding a wish to broaden the

work of the bureau of agricultural

economics among Negro farmers of the

country, and the president gave him

encouragement.94

Henry C. Wallace, secretary of

agriculture, was interested in having Scar-

borough's office give a few

scientifically trained Negroes positions to enable

them to assist the Negro farmer of the

South and to gather scientific data

touching Negro farm life and problems.

Scarborough submitted a plan for

carrying out this intention.95 In

executing the proposal, Scarborough per-

sonally went among the Negro farmers of

rich Southampton County, Vir-

ginia, to aid them to secure help from

the Federal Farm Loan Bank. He

now became an authority on the Negro

farmer in the South. He was the

author of a brief United States

Department of Agriculture monograph, Ten-

ancy and Ownership Among Negro

Farmers in Southampton, Virginia.96

In a practical way he was instrumental

in securing the admission of Negro

farmers to the Farm Loan Association,

from which they had previously been

excluded. He also contributed an article

to Current History on "The Negro

Farmer in the South," acknowledging

the discouraging situation for the

Negro there but declining to accept

Negro migration from the South as an

answer to the problem. He asserted:

The more I visit the congested parts of

cities like Cleveland, Chicago, Phila-

delphia, and New York, the more I am

convinced that the best place for the

average Negro, if he is a farmer and if

he is in any degree successful as such, is

in the farming districts of the

south....

The Virginia Negro farmers may be said

to belong to a thrifty group. Virtu-

ally all are members of a church and of

one or another of the many fraternal

groups among them; and seldom are any of

these affiliations neglected. Most of

the Negroes have automobiles and many

own victrolas. So the home conditions

improve.97

Shortly after his death, his article on

"The Negro Farmer's Progress

in Virginia" was published in Current

History. It presented numerous in-

stances and statistics to show their

increased wealth, cooperative marketing,

and educational progress, with the

conclusion: "These are most encouraging

WILLIAM SANDERS SCARBOROUGH 47

examples to set before the rising

generation, showing the possibilities resid.

ing in farm ownership and the worth of

farm life generally."98

Scarborough came to feel that the

failure of officials in Washington to

move further ahead in service to Negro

farmers was due to a fear of inte-

gration problems in Washington

government offices. Bills in which he was

interested that were intended to create

a Negro industrial commission, more-

over, were never reported out of

congressional committee.

During his work in Washington he was a

regular attendant at Sunday

church services, and occasionally he

left the city to make an address at

Tuskegee, Baltimore, or New York. At a

meeting of the Republican State

Voters' Association, on the occasion of

the "Ohio Night" ceremonies at the

Willard Hotel, he was directed to take

the freight elevator but refused to

do so. Later, Republican leaders assured

him that a change of location

was being made for other meetings and

that there would be "no repetition

of the unfortunate occurrence."

Needing rest, he took a month's vacation

at his Ohio home in July

1923. The death of Harding during the

next month was a great loss to

Scarborough, who recalled how he had

always been warmly welcomed at

the White House. On one occasion he had

been ushered into the cabinet room,

where a few members were lingering after

a meeting. Harding greeted him

cordially, threw his arm over the

visitor's shoulder, and turning to the mem-

bers, said: "I want to introduce

Dr. Scarborough to you. Here is a 100 per

cent American."

Scarborough was present when the Harding

funeral train reached Wash-

ington from San Francisco and paid a

condolence call at the White House.

Not long afterwards he paid his respects

to the new president, Calvin

Coolidge. Harding had definitely been

Scarborough's patron, and although

Attorney General Harry M. Daugherty,

Register of the Treasury H. H.

Speelman, and Senators Fess and Willis

were interested in his continued

government service, his work in the

capital ended, December 31, 1923.99

Returning to Ohio in December, he

gradually adjusted himself to

retirement at home, although he was

discouraged about the Wilberforce

situation. Governor Vic Donahey tried to

console him, writing in July 1924:

"I hope that things at Wilberforce

are not as bad as you think. I have

always tried to do what I could to aid

the institution."100 By this time the

campaign of 1924 was getting under way

and Scarborough worked ener-

getically for Coolidge's success.

In 1925 he was among those protesting

against the exhibition of the

movie The Birth of a Nation, which

many deemed an incitement to racial

48 OHIO HISTORY

prejudices, and Governor Vic Donahey of

Ohio wrote him, declaring his

determination to prevent the showing of

the picture.

In June of that year he went to Oberlin

to the fiftieth anniversary of

the graduation of his class (1875).

There, President Henry C. King gave

the baccalaureate sermon on

"Patience" and Newton D. Baker delivered the

commencement address, "Education in

Action." Scarborough enjoyed the

alumni dinner in Warner Gymnasium, and

the festive moments and the

joyous renewal of old friendships.

In November he went East to make his

annual address before the

Y.M.C.A., speaking on "Social Near

East Problems." But he realized that

his vigorous days were over, and now he

was in a time of life for reminiscing.

As he had grown older he grew more

conservative, more tolerant, less

aggressive. He believed that the Negro

had made "unparalleled progress"

in every line of endeavor, but that the

Negro churches had not kept pace with

the advance in home life and educational

efforts. He explained: "There has

grown to be too much of church politics,

too much greed on the part of

some high in its offices--a greed for

office, power, and money which has

dragged in the mire the robes of some in

ecclesiastical positions."

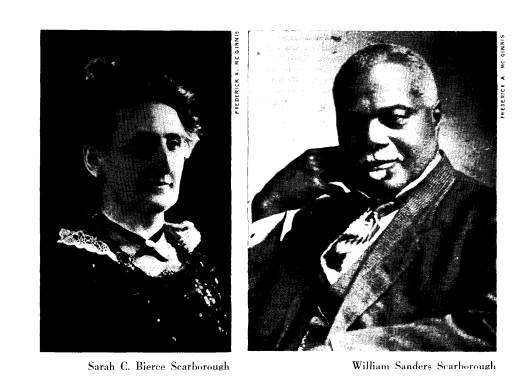

He had been associated with the

Wilberforce community for more than

forty years. There, in 1890, his wife

and he had occupied a new home,

named Tretton Place after the residence

of the Scarborough family in

Anthony Trollope's novel. This was their

home during the rest of their life

together. At times vicissitudes of

health had overtaken him. Under the

strain of efforts to secure

philanthropic aid for Wilberforce he had suffered

a temporary nervous breakdown in 1910.

On New Year's night 1915 he

had slipped on the ice on the university

campus, breaking two ribs and

fracturing a third. This necessitated

confinement to his home for many

weeks followed by a period of

recuperation in Florida.

He had vivid memories of inspiring

incidents over many years in the

classroom and of happy social occasions

with students and colleagues. In

his autobiography he recalled

the many pleasant hours when they were

gathered under our roof or on our

lawn for an evening or afternoon of

jollity, and I can see in memory the long

line passing at ten o'clock down the

stairway and through the long hall, a happy

throng, grasping our hands with an

appreciative word as they said goodbye--

each made happier by bearing away from

the large basket at the door an apple,

an orange, a huge popcorn ball as they

left us, an uplifted company to live on

higher planes and eagerly look forward

to another gathering.

Among all of his friends he felt that

Professor Richard T. Greener

|

|

|

had had the most salutary influence upon his career. He had known inti- mately the leading Negro leaders of his generation. Among them were Frederick Douglass, Booker T. Washington, and William E. B. Du Bois. After the death of Douglass at his home in Anacostia, February 20, 1895, Scarborough had gone there to serve as an honorary pallbearer. Booker T. Washington, as we have seen, had crossed his path many times and had at one time been his house guest at Wilberforce. In the small Wilberforce community he had known Du Bois well, for the latter had taught Latin and Greek there from 1894 to 1896.101 Scarborough never used tobacco and was a strong advocate of temper- ance, his glass always being turned down at banquets. He did not play cards and was never known to have danced, even in his younger days. Croquet games on the lawn, checkers as an indoor pastime, the companion- ship of his books, pleasant occasions with friends, travel, and the inspira- tion of music--these brought him relaxation. In June 1926 he attended commencement at Wilberforce for the first time in the six years since his retirement. He was persuaded to sit upon the stage, and thus witnessed the annual exercises for the last time. Now he gradually grew thin and became increasingly languorous. Rheumatic trouble crept upon him, and his enthusiasm for life was on the wane. A few days after the commencement exercises, he attempted to remove a broken limb from a cherry tree but had a fainting spell. He recovered, but a few |

50 OHIO HISTORY

days thereafter when a severe wind

leveled a giant oak on his lawn, he

faintly smiled as he observed,

"That is myself." On another occasion, in

his restlessness he insisted on working

on a grape arbor which had been

damaged by the storm. The next day an

increasing lameness and an attack

of nausea necessitated the calling of a

physician. On August 5 he was com-

pelled to go to bed for rest. Only once

thereafter did he leave the room,

then to creep painfully into the library

to take a last look at his books.

The nausea rapidly increased, so that he

was unable to take nourish-

ment or medicine. At first he was

rebellious, but then he manifested an

acceptance of the inevitable. The

constant solicitude of his wife, the visits

and prayers of his pastor, and the

faithfulness of friends and of his physician

were evident. At sunset on the evening

of September 9, he peacefully passed

away.102

Scarborough had preferred very simple

funeral services, but an ade-

quate recognition of his accomplishments

seemed necessary to his friends

and the university authorities. On the

morning of September 12 the casket

was taken to Galloway Hall, so that the

body might lie in state before the

platform on which he had appeared on

countless occasions. At the head and

foot of the casket stood a university

cadet. The services were held at one-

thirty in the afternoon. Dean George F.

Woodson of Payne Seminary

preached the sermon, emphasizing

Scarborough's religious faith. Bishop

Reverdy Ransom of the A.M.E. Church

delivered the eulogy. Dr. W. A.

Anderson, one of his early pupils and a

member of the university board of

trustees, read the biographical sketch

and a tribute prepared by Dr. W. A.

Galloway, Scarborough's co-worker for

many years on the state board of

trustees and his personal physician and

friend. Miss Hallie Q. Brown,

long-time neighbor and friend, read two

of his favorite poems, "Emanicipa-

tion" and "The Upper

Room." The choir then sang his favorite hymns, "In

the Cross of Christ I Glory" and

"Jesus, Lover of My Soul," and "There Is

No Death," was sung as a solo.

Numerous were the tributes of love and

appreciation that were received

at this time emphasizing his sterling

and gracious personal character. In

the field of leadership he had done much

for the Negro, for the Republican

party, and for Wilberforce, and in the

field of scholarship, the historian

of Wilberforce tells us, he was

"the greatest scholar to be connected with

the institution for nearly half a

century."103

NOTES

85

84 Official Records, VII, 23.

85 See petition of Ohio Senate to

President Lincoln [copy], February 3, 1862, in Garfield

Papers, Library of Congress.

86 Cleveland Herald, January 16,

1862.

87 Newspaper comments collected by J. H.

Rhodes from the New York Post and other papers

and quoted in a letter to Garfield,

January 20, 1862. Garfield Papers, Library of Congress.

88 Official Records, VII, 56. See

also ibid., 46-48, 55-57; Johnson and Buel, Battles and

Leaders, I, 396.

89 Official Records, VII, 48.

90 Ibid., 48-50.

91 Humphrey Marshall to Alexander

Stephens, February 22, 1862.

92 Official Records, VII, 57-58.

WILLIAM SANDERS

SCARBOROUGH

* This is the second and final part of

an article on William Sanders Scarborough, the first

part of which appeared in the October

1962 issue (v. 71, pp. 203-226).

1 Transactions of the American

Philological Association, 1882, XIII

(Cambridge, Mass., 1882),

iv. The Transactions of the American

Philological Association will be referred to hereafter as

Transactions only.

2 Ibid., 1884. XV (Cambridge, Mass., 1885), vi.

3 At this commencement Jebb had received

an honorary LL.D. Dictionary of National Biography,

1901-1911 (Oxford, 1912), 367-369.

4 Transactions, 1885, XVI (Cambridge, Mass., 1886), xxxvi.

Ibid., 1886, XVII (Boston, 1887), ii; ibid., 1887, XVIII

(Boston, 1888), ii.

6 Education, IX (1888-89),

263-269.

7 Ibid., 396-399.

8 Ibid., X (1889-90), 28-33.

9 Transactions, 1888, XIX (Boston, 1889), xxxvi-xxxviii; ibid., 1889, XX

(Boston, 1889), v-vi.

10 Ibid., 1890, XXI (Boston, n.d.), xlii-xliv. Later, he read a paper

with the same title before

the National Educational Association.

11 Ibid., 1891, XXII (Boston, n.d.), 1-lii.

12 Education, XII (1891-92), 286-293. The paper was based largely on

Grote's History, VII,

154.

13 Education, XIV (1893-94), 213-218. It was also summarized in Transactions,

1892, XXIII

(Boston, n.d.), vi-viii.

14 "Hunc Inventum Inveni," Transactions,

1893, XXIV (Boston, n.d.), xvi-xix.

15 Ibid., 1894, XXV (Boston,

n.d.), xxiii-xxv.

16 Ibid., 1895, XXVI (Boston,

n.d.), xi.

17 Ibid., 1896, XXVII (Boston,

n.d.), xlvi-xlviii.

18 Ibid., 1898, XXIX (Boston, n.d.), lviii-lx.

19 Education, XIX (1898-99), 213-221, 285-293.

20 Transactions, 1902, XXXIII

(Boston, n.d.), xx.

21 Ibid., 1903, XXXIV (Boston,

n.d.), xli.

22 Ibid., 1906, XXXVII (Boston,

n.d.), ii, xxx-xxxi.

23 Ibid., 1907, XXXVIII (Boston,

n.d.), ii, xxii-xxiii.

24 Ibid., 1908, XXXIX (Boston, n.d.), v.

25 Ibid., 1911, XLII (Boston,

n.d.), ii.

26 Ibid., 1912, XLIII (Boston, n.d.), ix-xvii.

27 Ibid., 1913, XLIV (Boston,

n.d.), iii.

28 Ibid., 1916, XLVII

(Boston, n.d.), ii.

29 Arnett was born at Brownsville,

Pennsylvania, March 16, 1838, and died at Wilberforce,

Ohio, October 7, 1906. For a listing of

a collection of his papers, see The Benjamin William

Arnett Papers at Carnegie Library,

Wilberforce University, Wilberforce, Ohio, compiled by

Casper L. Jordan (Wilberforce, Ohio,

1958).

30 Leonard E. Erickson, "The Color

Line in Ohio Public Schools, 1829-1890" (unpublished

Ph.D. dissertation, Ohio State

University, 1959), 333-339.

31 Champion City Times (Springfield,

Ohio), March 1, 1887.

32 The Centennial Jubilee of Freedom

at Columbus, Ohio (Xenia, Ohio, 1888), 67.

86

OHIO HISTORY

33 Arlin Turner, George W. Cable (Durham,

N. C., 1956), 241-262.

34 The Forum, VII (1889), 80-89.

35 The Arena, II

(1890), 39-56. For Breckinridge's important political, legal, and journalistic

career, see Dictionary of American

Biography, III, 11-12.

36 Wade Hampton, "The Race

Problem," The Arena, II (1890), 132-138.

37 Yet Hampton was relatively a moderate

and was defeated for reelection to the senate by

the demagogic Ben Tillman. Hampton M.

Jarrell, Wade Hampton and the Negro: The Road

Not Taken (Columbia, S. C., 1949).

38 The Arena, II (1890), 560-567.

39 Ibid., IV

(1891), 219-222.

40 The Forum, XXV1 (1898-99), 434-440.

41 Education, XX (1899-1900), 270-276.

42 Annals of the American Academy of

Political and Social Science, XVI

(1900), 145-147.

43 See also Daniel Walden, "The

Contemporary Opposition to the Political and Educational

Ideas of Booker T. Washington," Journal

of Negro History, XLV (1960), 103-115.

44 After careful study of the Booker T.

Washington papers a recent student concludes: "It is

clear, then, that in spite of his

placatory tone and his outward emphasis upon economic develop-

ment as the solution to the race

problem, Washington was surreptitiously engaged in undermining

the American race system by a direct

attack upon disfranchisement and segregation; that in spite

of his strictures against political

activity, he was a powerful politician in his own right." August

Meier, "Toward a Reinterpretation

of Booker T. Washington," Journal of Southern History,

XXIII (1957), 220-227.

45 Various papers from his pen were published during this period in the Southern

Workman

and Hampton School Record.

46 The Kansas City Star declared

that this discriminatory action was wholly "at variance with