Ohio History Journal

|

|

|

SIMEON PORTER ?? OHIO ARCHITECT

by ERIC JOHANNESEN

Of the many carpenters and master builders who gave the Western Reserve villages in northern Ohio their characteristic look of colonial New Eng- land in the first decades of the nineteenth century, only a handful are known today. Similarly, the architects of the great era of urban growth in the United States during the two decades before the Civil War are largely anonymous. Yet a few known builders belonged to both periods and spanned the transition from the pioneer, post-colonial society to the urban, industrial one. One of these was Simeon C. Porter of Hudson. The work of Simeon Porter has long been appreciated in Hudson, and he is known by name as the partner of Charles W. Heard in Cleveland. But until now there has been no consecutive account of the entire career and

NOTES ARE ON PAGES 210-212 |

170 OHIO HISTORY

work of this remarkable man, who

achieved the distinction of having done

some of the most notable post-colonial

and Greek Revival work in northern

Ohio, and then of going on to create a

body of equally notable Victorian

eclectic work.

Simeon Porter was the son of the famous

master builder Lemuel Porter.

The elder Porter migrated to Ohio from

Waterbury, Connecticut, in 1818

and settled in the town of Tallmadge.1

Having been born in 1807, Simeon

was eleven years old at the time. Lemuel

Porter was past forty, and had

been trained as a woodworker and joiner

in New England. His abilities

were soon in demand in Ohio, and in 1821

he was employed to superintend

the joiner work of the historic

Congregational Church in Tallmadge. This

church has been frequently described

elsewhere, and there seems to be

general agreement that it is the finest

of early Ohio churches. Completed

in 1825, it is nearly identical in

general appearance, proportion, and

details with churches which the

well-known architect David Hoadley was

building at the same time back in

Connecticut.2

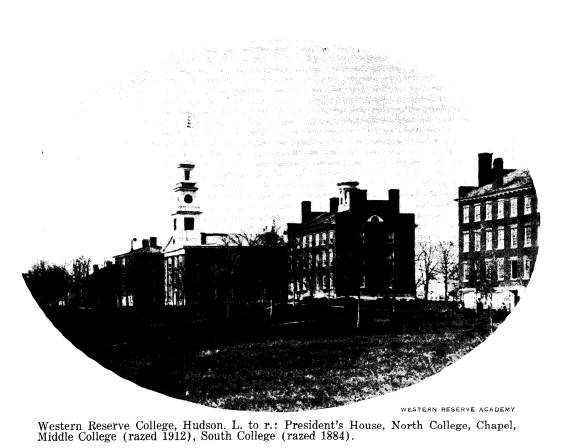

In 1824 Lemuel Porter was appointed to a

committee on location for

a Western Reserve collegiate

institution.3 The town of Hudson, ten miles

north of Tallmadge, was selected, and in

1826 Lemuel Porter was given

the contract for the work on the first

building of the new Western

Reserve College. This building, later

known as Middle College, was com-

pleted in July 1827. Middle College was

a simple rectangular brick block

56 feet by 37 feet, recalling similar

New England buildings of the late

eighteenth and early nineteenth

centuries. Its chief architectural feature

was the cupola, an open cylindrical

belfry with arches and pilasters, sup-

porting a hemispherical dome.4 This

feature appeared again in his son

Simeon's work, even as late as 1861.

In March 1829 Lemuel Porter was given

the contract for two new

buildings for the college, the

"chapel" and the "houses for the professors."5

The "chapel" was actually the

building known as South College, for

the present chapel was not built until

1835. Porter moved to Hudson with

his family in order to superintend the

college work, but he died suddenly

in September 1829. The trustees had such

confidence in the ability of

Simeon, now twenty-two years old, that

he was appointed to fulfill his

father's contract. Accordingly, the

South College building was completed

in 1830. South College was a four-story

multipurpose building measuring

64 feet by 37 feet. The chapel and

theology rooms occupied the first floor,

the preparatory and collegiate

departments the second, and dormitory

suites the third and fourth floors. The

lower story was constructed of

sandstone and the other three stories of

brick. The building was marked

with little of architectural note.

Although of four stories instead of three,

it closely resembled Middle College,

having the same stepped gables

and paired chimneys.

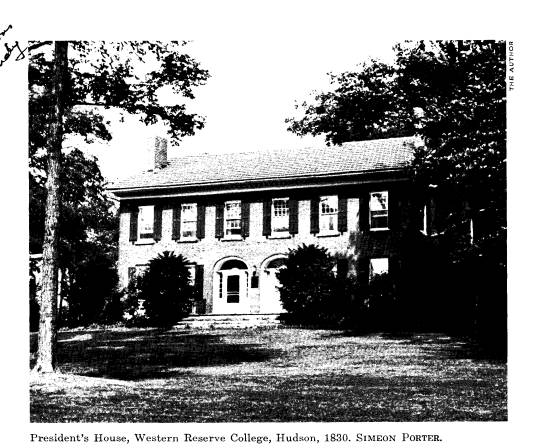

Also in 1830, Simeon Porter erected the

second of the two buildings

which had been contracted for the year

before. This was the double

residence built for the accommodation of

two professors. Later it became

SIMEON PORTER 171

known as the President's House. Since

Middle and South Colleges have

both been demolished, the President's

House is the oldest building now

remaining on the campus, and in the

opinion of many, the most architec-

turally gracious of all. A handsome

brick house, its ornamental details

are in the manner of the post-colonial

Adamesque style of New England,

which suggest that probably it was

designed by Lemuel Porter before his

death. The most important feature of the

design is the pair of identical

central doorways. The delicate

proportions and placing of the sidelights,

elliptical fanlights, and the half

columns on either side of the doorways,

give the entrance, and the house, a

distinction equal to that of any

New England counterpart, and make it a

fitting posthumous tribute to

the life work of Lemuel Porter of

Connecticut.

The independent career of Simeon Porter,

then, actually began in

1830. His younger brother Orrin, also a

builder, was now his partner.

The two brothers worked together on

contracting, which included masonry,

carpentry, and painting.6 In August 1834

the erection of the next college

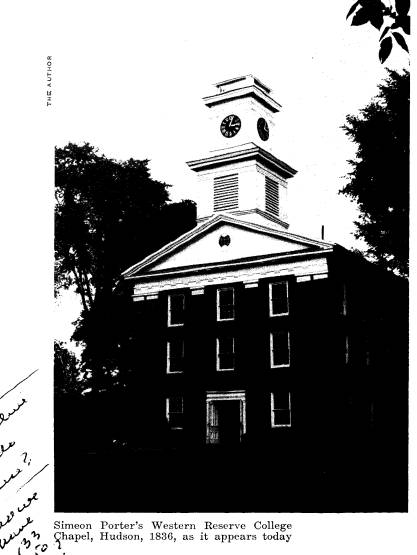

building was authorized by the trustees.

A resolution of their meeting

reads: "Resolved that Messrs.

Pierce, Pitkin, and Bradstreet be a com-

mittee to draw a plan for the

contemplated Chapel."7 It seems certain

that this committee, according to the

general practice of the day, deter-

mined the general plan of the building,

and left the design and details to

the master builder. Colonel S. C. Porter

was the contractor.8 On January

1, 1835, bids for the timber were

solicited, and by November 1 the brick

walls were completed. The Chapel was

dedicated on August 23, 1836,

its total cost having been $6,231.52.

Like South College a multipurpose

building, the Chapel had a library and

two recitation rooms on the

first floor, the auditorium with two

recitation rooms on either side on

the second floor, and the

horseshoe-shaped gallery of the auditorium

occupying the third floor. As originally

built, the Chapel was 40 feet by

60 feet. The bell tower had three square

diminishing stages with balus-

trades. The uppermost tower stage was

removed in 1871, altering the

proportions of the building, and in 1940

the building was extended 22

feet at the rear, still further changing

its original appearance.

For a long time there was a tradition

that the design of the Chapel

was copied from some New England church,

perhaps the chapel at Yale.

This tradition, apparently refuted for

years, was confirmed only recently

with the publication of the description

and pictures of the first chapel

at Yale, built in 1762-63 and razed

toward the end of the nineteenth

century.9 It was a three-story building

with the chapel and the gallery

in the lower two floors, and the library

on the upper one. President

Pierce's committee simply turned the

Yale building upside down! In

design, however, the Yale chapel was a

typical colonial meetinghouse,

with an attached bell tower at the

front. Simeon Porter's design for the

Western Reserve Chapel, on the other

hand, was Greek.

It is important to emphasize that the

Porters were not yet architects

in the modern sense at all. They had no

formal architectural training.

172 OHIO HISTORY

Lemuel Porter, as has been mentioned,

came from the New England

woodworking tradition, and was a builder

and contractor by experience.

The Western Reserve buildings are

essentially the building of master

craftsmen, and whatever architectural

merit they have is due to the

use of details supplied by the builders'

handbooks which were so widely

circulated. The comment of I. T. Frary

on this point is interesting:

The clumsy attempts at classic

pilasters, columns, mouldings, and

cornices often produced curious effects

that would scarcely pass

muster in a school of architecture or a

Beaux-Arts competition. They

were crude, the details often painfully

misunderstood, yet in them

we recognize a sincerity that wins our

admiration. Those pioneer

builders were creating a vernacular in

architecture possessing vital-

ity and spontaneity that is often

missing in highly sophisticated

creations.10

It is also important to ask the extent

to which Simeon Porter was

acquainted with the Greek Revival. The

Greek Revival in the East was

beginning and reached maturity

simultaneously with the migration to

the West. The earliest settlers, the

generation of Lemuel Porter, used

the handbooks of the post-colonial

style, the "Adamesque," which were

rapidly going out of fashion in the

East. By 1830, when Simeon Porter's

independent building career began, the

inhabitants of Ohio were cer-

tainly familiar with the Greek Revival.

In Asher Benjamin's manuals

of the 1830's, the Greek style had won

out completely. A copy of Benjamin's

Practice of Architecture, printed in 1835, may be found in the Hudson

Historical Society, where it is

hopefully believed that it belonged to

Simeon Porter. The preface to this work,

written in 1833, suggests rea-

sons for the appeal of the Greek

Revival:

The text is taken from the Grecian

system, which is now universally

adopted by the first professors of the

art, both in Europe and America;

and whose economical plan, and plain

massive features, are peculiarly

adapted to the republican habits of this

country.11

In addition, the classic style would

certainly have appealed to the trustees

of Western Reserve College as a fitting

embodiment of the scholarly cul-

ture which they were intent upon

establishing at "the Yale of the West."

The Chapel is the first of the college

buildings to use Greek detail,

and could possibly be called the only

fully developed Greek Revival build-

ing on the campus. Daniel Giffen has

made a careful study of many of

the decorative details -- pilasters,

moldings, windows, and doorways--

in the Chapel, North College, the

Observatory, and the Athenaeum.12 Com-

paring these with plates in Benjamin's The

Practical House Carpenter

of 1830, he concludes that this book was

almost certainly a source of

Simeon Porter's details. Instead of the

typical Greek columned portico,

the Chapel facade has three-story brick

pilasters, doubled at the corners,

|

and topped by a Doric entablature and pediment. The entablature does not continue around the sides of the building, but gives way to blind arcades, another feature which reappears in Simeon Porter's work as late as the Civil War years. The tower is of wooden frame construction, and the pilasters on its second stage follow a Benjamin pattern. The next college building to be erected in Hudson was North College. The contracts were made in August 1837, and construction was begun immediately. Designed as a dormitory for theological students, the build- ing was completed in the summer of 1838 and served this purpose until 1853. A simple brick building like the earliest two college buildings, it measured 37 feet by 58 feet, and in the judgment of I. T. Frary had "but little aside from its doorway to claim architectural distinction."13 The wooden door frame is set between heavy stone piers and topped by a heavy stone lintel carved in relief. The college also erected an Observatory in 1838. Notable as the third astronomical observatory established in the United States, and the first west of the Alleghenies, it exists today as the second oldest observatory building in the country. It is named for Professor Elias Loomis, one of the great American mathematicians and astronomers, who worked there. A smaller building, only 16 feet by 37 feet, the Observatory boasted a dome nine feet in diameter. It begins to appear that the 37 foot dimension was a kind of module, being used in four of the six college buildings up to this point. As in the structure of the other buildings, the Observatory |

174 OHIO HISTORY

had foundations, sills, and lintels of

dressed sandstone, and walls of brick.

The telescope was supported by two

monolithic piers of sandstone set six

feet into the ground and independent of

the building structure.

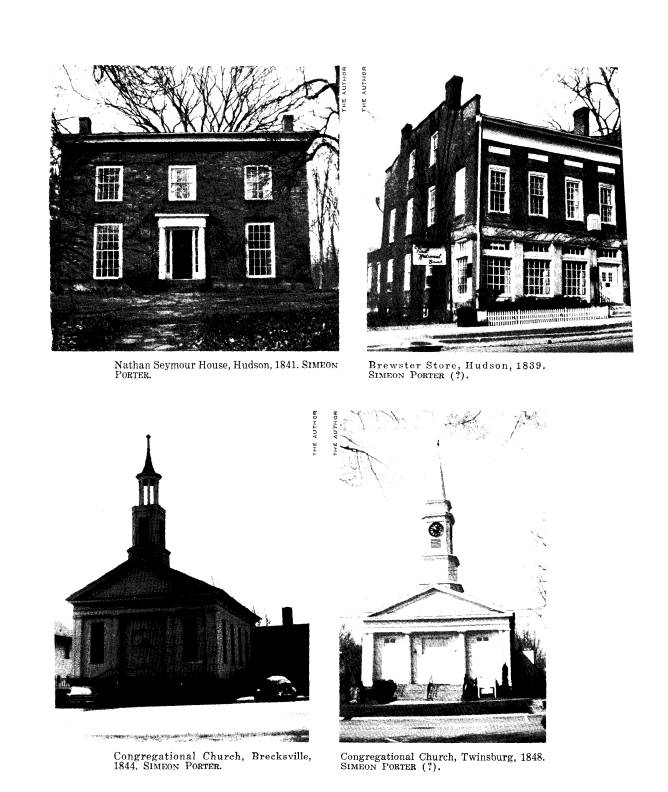

In February of 1840 the last of Porter's

Western Reserve College

buildings was authorized. It was to be a

natural science building, and

has always been called the Athenaeum.

Uncertainty as to its location

delayed construction for over a year.

Meanwhile, in 1841, Nathan Seymour,

professor of Greek at the college, built

himself a house. Helen Kitzmiller,

in a brief paper on the house, says that

"Simeon Porter built Seymour

House, literally under the very eye of

the professor."14 The house is an

imposing rectangular brick structure,

one of the most pleasing in the

village, and its doorway has perhaps the

most handsomely proportioned

Doric portico in Hudson. As Frary says,

"It is quite obvious that a man

of his attainments would have the portal

of his house designed as nearly

as possible in conformity with the

ideals of the Greeks, whose culture

was his life study."15

During the winter of 1841-42, the walls

and roof of the Athenaeum were

completed. In August 1842 the finishing

of the first and second floor

interiors was contracted, and these

floors, containing four large lecture

rooms apiece, were occupied in February

1843. The third floor, finished

later, contained a natural history museum.

This three-story brick building

was the largest of the college

buildings. The front was dominated by a

tower which combined features of the

Chapel tower and the Middle

College belfry, having a square base

surmounted by a cupola. The side

elevations showed the three-story

pilasters and the blind arcades of the

Chapel design. However, the tower was

removed in the 1860's, and a

drastic alteration in 1917-18 converted

the Athenaeum to a dormitory of

four stories, so there is little left of

its original appearance. The comple-

tion of the Athenaeum made a total of

seven college buildings erected

by the Porter family, father and sons,

between 1826 and 1843, and those

still standing remain their most imposing

monument in Hudson.

By now Simeon Porter's reputation had

brought him a contract to

build in Brecksville, fourteen miles

south of Cleveland. There he built

the Brecksville Congregational Church in

1844.16 This church is one of

the purest Greek Revival designs known

to have been done by Simeon

Porter. The front is divided into three

bays by double pilasters at the

corners and fluted half-round Doric

columns flanking the entrance. The

tower is a curious combination of an

octagonal base with a circular open

belfry and a conical spire. It is

difficult to tell whether the uppermost

section is part of Porter's original

design, for the present one is a

recent restoration, but it does recall

vaguely the open belfry and spire

of Lemuel Porter's Tallmadge church.

There remains one more public building

from this early Hudson period

of Simeon Porter's career to be

mentioned, and it will always be a

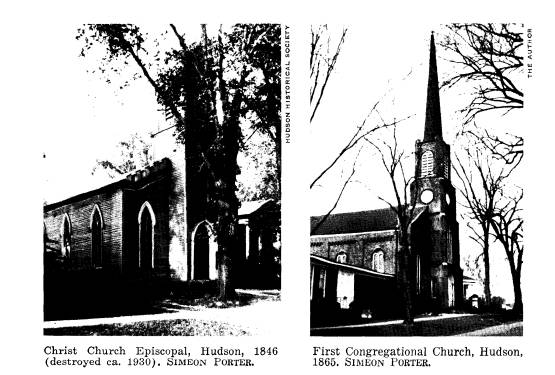

curiosity. The Christ Church Episcopal

of Hudson is the only example

of Porter's work known for certain to

have been done in the pointed

SIMEON PORTER 175

Gothic Revival style. By 1846, the date

of its erection, the Greek Revival

was on the wane. It was rapidly being

replaced by the various medieval

styles, of which the Gothic was to

become a favorite for church edifices.

The Episcopal Church, a wooden frame

building, was authorized in Jan-

uary 1846, its cornerstone laid in

April, and the sanctuary opened for

divine service and consecrated in

September. A historical sketch of 1876

states that "the plan of the church

was furnished by Bp McIlvaine, but

was greatly modified by Mr. Porter, and

produced a church beautiful

in style and proportions."17 Perhaps

this explains Porter's momentary

dabbling in the Gothic fashion. Did

Bishop McIlvaine "furnish" the

Gothic design, or did Porter's

modifications make it Gothic? The fact

that all of Porter's experience so far

was in the classic styles strongly

suggests the former alternative, but we

shall probably never know for

sure. The 1846 building of Hudson Christ

Church Episcopal exists no

longer, having been destroyed by fire

and replaced by the present classically

styled building in 1930.

Sometime in 1848 Simeon Porter moved

from the town of Hudson to

the growing city of Cleveland. Before

leaving the earlier part of his

career, however, it is necessary to

enter the realm of conjecture briefly.

The buildings already described are

those for which there is positive

documentation, but they leave much of

the time between 1830 and 1848

unaccounted for. Frederick C. Waite, the

son of an apprentice and painter

under Porter, and later a professor at

Western Reserve University, makes

the following statement about Simeon and

Orrin Porter: "These two

brothers . . . built not only the

college buildings but all the best residences

in town before the Civil War."18

Unfortunately he does not identify the

specific buildings. Mrs. Henry Farwell,

a niece of Simeon, states in her

biographical sketch of the Porter family

that Simeon "had all the work

he could do and employed apprentices and

journeymen in his mechanical

operations" in Hudson and its

vicinity.19 Furthermore, there were appar-

ently no other men living in Hudson

between 1830 and 1850 capable of

the necessary joinery and masonry

contracting that was done. Since the

town records of Hudson were destroyed by

fire in 1892, we are forced

to rely on clues such as these. If we

take them seriously, what begins to

emerge is the picture of an entire

village, one of the most characteristic

(and best preserved) villages of the New

England type in the Western

Reserve, for which the two brothers,

Simeon and Orrin Porter, were

almost totally responsible.

In view of the fact that such contracts

as are known were made with

Simeon, and in the light of his later

career as partner of one of the

most noted architects of Cleveland, it

seems reasonable to assume that

Simeon was the senior partner and

designer, and the younger brother

Orrin was his assistant in the

contracting and building. Needless to say,

there are varying degrees of probability

for the attribution of certain

buildings to the Porters. It is beyond

the scope of this article to do more

than mention some of the buildings in

which the evidence of the design,

176 OHIO HISTORY

or ownership (as in the case of the

college), or enlightened opinion, sug-

gests attribution of the work to the

Porters.

The old dining hall of the college, or

Nutting House (1831-32), seems

the most nearly certain, inasmuch as

Porter was the college architect.

The house is deservedly famous for its

doorway and "sunburst" fanlight.

The house which now houses the Hudson

Historical Society (1835)

carries an unauthenticated tradition

that it was done by workmen of the

Porters during the times when they were

not occupied on the college

buildings. There are any number of other

houses where a family or verbal

tradition connects their origin with

Simeon Porter. Some of these are

country houses in brick or stone within

a five-mile radius of Hudson. The

Brewster Store, built in 1839 and now

the First National Bank, and another

store built by E. B. Ellsworth on

virtually the same pattern, were worked

on by a carpenter of Porter's.20 If

they were indeed designed by Simeon

Porter, they afford interesting early

examples of commercial buildings

added to his domestic, educational, and

religious work.

The famous Congregational churches at

Twinsburg (1848) and Streets-

boro (1851), each only five miles from

Hudson, are so similar to the

Brecksville church that it is difficult

to suppose that they were not done

by Porter. No less an authority than I.

T. Frary, probably the most noted

historian of Ohio's early architecture,

had this opinion: "[The churches]

at Twinsburg, Brecksville, Streetsboro

and Gates Mills, all [are] located

so closely together and [show] such

similarity of effect, especially the

first three, that it seems quite

probable the same builder may have been

responsible for them all."21 Furthermore,

there is a possibility that a

traveling minister was responsible for

the religious guidance of the

three churches, preaching a Sunday a

month at each of them.22

One more Hudson building must be left

until later. This is the Brewster

house, The Elms, a turreted Gothic

sandstone pile, totally different from

the neighboring Greek Revival work. But

this house must be seen in

the light of later developments. For

Simeon Porter was about to embark

on the second phase of his career, which

would be as notable in its way

as the Hudson phase. His early training

as journeyman and master builder

were to stand him in good stead, so that

the growing mid-century trend

toward eclecticism was always tempered

in him with soundness of pro-

portion and construction.

When Porter arrived in Cleveland, its

population of 17,000 was almost

thirty times that of 1820, when the

Porters were newly arrived in

Ohio. Cleveland at mid-century was fully

aware of its destiny as the

great Metropolis of the Lakes. It was already

a center of shipping, com-

merce, manufacturing, and railroad

transportation. The next decade saw

enormous changes in the architectural

character of the city, and playing

the foremost role in these changes was

the firm in which Simeon Porter

became a partner. Porter first listed

himself in the city directory as

"architectural draftsman and

building engineer."23 Although he did not

yet call himself "architect,"

the decade of the fifties saw the emergence

SIMEON PORTER 177

in the Midwest of the profession of

architecture in the modern sense,

and the transformation of Simeon Porter

from master builder into

architect.

In 1848 Porter joined the workshop of

the master builder Perley Abbey

for a brief time, but there is no record

of work done by them. Sometime

in 1849 or 1850 he joined Charles W.

Heard as master builder.24 Charles

W. Heard, one year older than Simeon

Porter, had worked in Cleveland

since 1833. He was the co-worker and

son-in-law of Jonathan Goldsmith,

whose Greek Revival work in and around

Painesville is well known.

Goldsmith and Heard had been responsible

for some of the best houses

on Euclid Avenue, which was rapidly

becoming the most important

residential street in Cleveland. Heard

took over Goldsmith's practice

upon his death in 1847. In 1849 Heard

built a house for Henry B. Payne

on Euclid and Perry (East 21st) Streets,

in the Gothic style.25 Its details

showed Heard's acquaintance with the

books of Andrew Jackson Downing,

one of the chief promulgators of the

Gothic Revival. Heard's most im-

portant non-residential building in the Gothic

style was St. Paul's

Episcopal Church, located on Euclid and

Sheriff (East 4th).26 It was com-

pleted in 1851 after having been under

construction since 1848 and having

suffered destruction by fire during that

time. The brick structure was a

fairly typical design of the early

Gothic Revival, with a lofty spire,

buttresses, and pinnacles.

Thus Simeon Porter came into an office

where the Gothic Revival had

supplanted the earlier classical styles.

This fact makes it possible to

understand how the design of the

Brewster house in Hudson may have

come about. Mr. Brewster built his home

next door to the store at the

north end of the Hudson green sometime

between 1850 and 1853. It must

have seemed quite anomalous among the

late colonial and Greek Revival

buildings as the large squarish

sandstone front rose into the air, presenting

the villagers with a projecting

two-story portico framed by twin octagonal

towers with ogival turrets. A large

pointed arch framed the upper porch,

a shallow Tudor arch the lower one. This

design bears strong resemblances

to that of the Old Library at Yale by

Henry Austin (1846). It may be

traced further to an Ithiel Town and A.

J. Davis project of 1838 for a

University of Michigan building, and

beyond that to illustrations of King's

College Chapel at Cambridge which were

known from architectural books.

In The Elms this design for a large

public building has been greatly

reduced for a private dwelling. Now

Simeon Porter was in Heard's office

with access to some of the latest architectural

books, he was aware of

the Gothic Revival, and he was now an

"architectural draftsman." It is

also certain that he maintained contact

with Hudson friends and relatives.

If The Elms was the work of Porter, it

was probably his first design done

with the point of view of an

"architect" as opposed to that of the master

builder.

It is now obvious, as Edmund Chapman has

pointed out, that "judging

by the number of important buildings

attributed to this firm in the records,

|

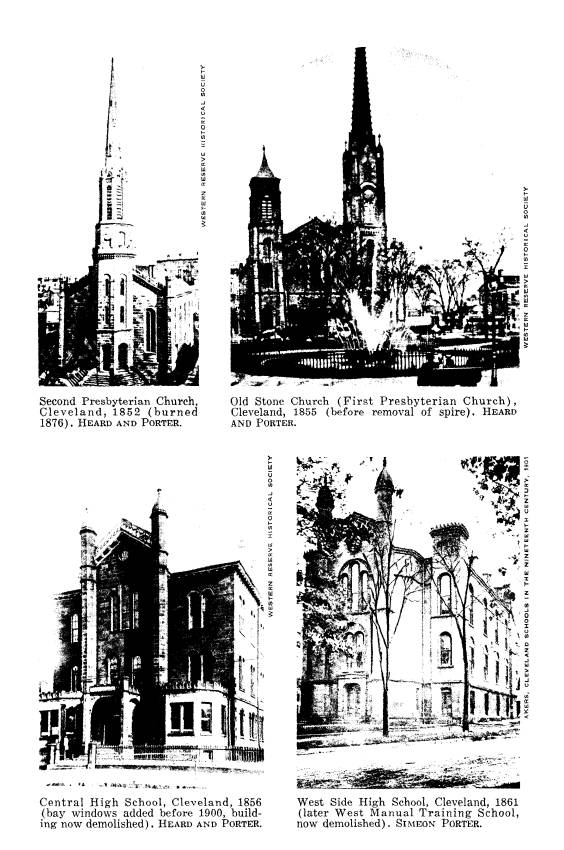

[Heard and Porter] was the leading construction company of the period in the city."27 Within two years after the partnership was formed, they were at work on two important buildings, both churches, which would change the aspect of the Public Square. The first to be completed, the Second Presbyterian Church, was on Superior just east of the square. The other was the second edifice of the First Presbyterian Church, or the "Old Stone Church," located directly on the square. The designs for both churches were neither classic nor Gothic, but Romanesque. We must admit that there is no way of telling the extent to which Heard or Porter was responsible for design and style. Probably Heard was the architectural designer and Porter the master builder in the early years of their relationship, although we know that each designed buildings of his own later. The shift to the Romanesque style can rather be explained by the fact that it was rapidly replacing the popularity of the earlier revivals for a number of reasons. Carroll L. V. Meeks has shown that the round-arched style (called either Romanesque, Renaissance, or Norman, depending on the decorative detail) was the predominant style in America during the decade and a half before the Civil War.28 The Romanesque style was used for all types of buildings. It was justified by apologist Robert Owen on the basis of convenience, economy, beauty, and even morality and democracy.29 Probably the most influential design was that of James Renwick's Smithsonian Institution (1846), chiefly for |

180 OHIO HISTORY

its asymmetrical towers. Churches done

in the Romanesque style displayed

sometimes the asymmetric pair of the

Smithsonian, or a single tower

axially placed. The style gained great

popularity in the late 1840's and

1850's, and spread rapidly and widely

throughout the United States.

Heard and Porter's Second Presbyterian

Church was built in 1851-52,

and opened for services on September 26,

1852. Its general form was

not unlike that of Heard's earlier St.

Paul's, a simple rectangular block

with five windowed bays. The chief

difference was that the central entrance

tower was octagonal instead of square.

The reminiscences of S. J. Kelly

describe the Romanesque detail of the

church:

Its high stone tower at the center, half

imbedded in the church, was

topped by battlements. Above the tower

an octagonal continuation

housed a clock beneath a tall shuttered

belfry, each corner forming

a miniature tower with castle-like tops.

Far above these rose a slender

spire, 185 feet high. . . . Three arched

entrances were at the tower's

base, reached by three radiating flights

of steps. . . . Along the roof's

edge at its sides and front ran

foot-high battlements. The entire front

was of brown sandstone. . . . Completed

and furnished, the structure

cost $70,000 to the credit of the

society; Heard & Porter, who designed

it, and Heard & Warner, who

supervised its erection.30

Inside, the sanctuary, or "main

audience room,"31 was the largest in

the city, 98 feet by 63 feet, and 39

feet high, and had a gallery on three

sides. The principal floor could seat

850. In the basement there were three

meeting rooms, separated by folding

doors, which could be opened into

one room seating 1,000 people. This in

itself was rather remarkable. The

use of folding partitions apparently

developed in the late 1840's. Their

use in this Cleveland church was among

the first, and gives further

evidence of the advanced nature of Heard

and Porter's work. This edifice

of the Second Presbyterian Church served

until 1876, when it was

destroyed by fire.

Discussions had begun as early as

December 1851 on the "expediency"

of tearing down the old structure of the

First Presbyterian Church on

the square.32 Once the

decision had been made to rebuild the "Old Stone

Church" on the same location, plans

were prepared by Heard and Porter,

and the site was cleared. On September

9, 1853, the cornerstone laying

took place.33 By February the

chapel (30 feet by 70 feet) in the new church

was so nearly completed that the first

services were held in it. The church

was finally dedicated on August 12,

1855, having cost $60,000. The spire

on the east tower was carried up after

this date, and finally reached a

height of 228 feet.

In designing the Old Stone Church, it

seems almost as if Heard and

Porter were ringing the changes on the

Romanesque style described

above. Instead of the single central

tower of Second Presbyterian, Old

Stone carried two asymmetric towers.

Whether this scheme can be traced

|

to the design of the Smithsonian building in every case or not, the towers of the Old Stone Church are very similar to those on the Smithsonian. The main portal makes effective use of Norman zigzag molding within the round arch. Of the original interior next to nothing is known, for it was destroyed by fire in 1884. But there may be some justification for considering the exterior design of the Old Stone Church the masterpiece of the Heard and Porter years together. The mid-decade year of 1855 was a most productive and significant year for the firm. In addition to the completion of the Old Stone Church, at least three schools were finished or begun. Several residences by Heard and Porter were planned or abuilding. The firm also did commercial work in the district between the square and the river. And the first plans for the new Federal Post Office building were made in this year. In January 1855 it was announced that Heard had received the con- tract for finishing the Marine Hospital.34 The United States government had planned a marine hospital at Erie (East 9th) and Lake Streets as early as 1837, and although only partly finished, it was opened for service in 1852. This contract is probably another evidence that Heard worked as a building contractor as well as architect as late as 1855. The Eagle Street School was completed in June 1855.35 This was a three-story brick building 50 feet by 72 feet. An engraving of 1876 shows a front with a simple portico of three piers, and four two-story pilasters with a large scroll-bracketed cornice. On the other hand, there is no documentary evidence that the Hicks Street School was done by Heard and Porter, but the date, the style, the structure, and the fact that the |

|

firm was employed regularly by the board of education makes it seem likely. The school was described as being in the same style as the Eagle Street School, but was 50 feet by 50 feet.36 Largely rebuilt in 1861 and 1884, it is doubtful whether any of the 1855 work remains in the present building (on West 24th Street), but the interior still has cast-iron struc- tural columns of the same type that were used in other Heard and Porter buildings at the same time. The new Central High School begun that year represents a significant point in the careers of Heard and Porter, chiefly because of its charac- teristic nineteenth century approach to design. The city council on March 9, 1855, ordered the immediate erection of a new high school to replace the temporary building of 1852. It was to cost around $15,000, and Heard and Porter were selected as architects in May. The school was located on Euclid near Erie (East 9th), and by the time the building was dedicated on April 1, 1856, it had cost $20,000. It was hailed as "the finest school in the West," but many taxpayers considered it "a piece of vicious extrava- gance."37 It is not difficult to see why. The front of the 60 by 90 foot brick building was faced in stone. The cornices were battlemented in the Ro- manesque style. The main entrance was framed by two octagonal towers rising three stories, with ogival turrets. The entrance portico was also arched, battlemented, and turreted. This combination of elements is obviously another version of the King's College scheme that has already been seen in connection with The Elms in Hudson. This conclusion would not only link the design of The Elms with that of the high school but also suggest the possibility that Porter was the principal designer of the |

184 OHIO HISTORY

high school. On the interior the Central

High School boasted one of the

earliest uses of cast-iron structural

columns in place of masonry walls.

Architects have always agreed that the

form of a building should be

appropriate to the purpose it serves. To

the nineteenth century mind

this appropriateness was more likely to

be found in symbolic associations,

and a school building might very

logically be medieval. On the other hand,

the nineteenth century builder was an

eminently practical man. The new

invention of cast iron, made available

in structural architectural pieces,

could not be ignored. Men like Heard and

Porter can not be blamed either

for using style as symbolism or for not

being a generation ahead of their

time and suddenly seeing the

possibilities of the all-metal frame. Rather

they must be credited with inventiveness

(or adaptability) in using the

cast-iron column as a space and

material-saving device, even within the

framework of stylistic symbolism. But

this is the point where we can

see the beginning of the breakdown of

the unity of design and structure

which was to afflict the rest of the

nineteenth century. Good brick side

walls, a Romanesque facade for style and

show, interior iron columns

for space and strength--these are

typical of the nineteenth century

approach to design.

The residence which Heard and Porter

built for H. B. Hurlbut was one

of several whose plans were seen by a

reporter visiting their office in

October 1855.38 They included houses for

C. Hickox and a Mr. Mason,

and were in the $11,000 to $16,000 price

range. The Hurlbut House is an

excellent example of the firm's work in

the popular type of so-called

Italianate villa. The Italian, or

Tuscan, villa style was a revival which

had arrived in America in the 1830's and

was extremely popular in the

years before the Civil War. The chief

examples of Richard Upjohn, John

Notman, Henry Austin, and Calvert Vaux

were irregular in plan and

outline.39 But the Hurlbut

House is of the second type of Italian villa, a

large simple cube with a lookout on the

flat roof. It has been suggested that

the "cupola" or

"observatory" was an economical substitute for the more

picturesque tower. The villa also

displayed wide projecting bracketed

eaves. On the Hurlbut House the eaves

were embellished with large

Greek floral ornaments, as was the

cupola and the entrance portico. The

proposed house was to be in

"mastic," evidently a kind of cement for

facing the walls. Apart from the

brackets and the anthemions, the design

was almost austere in its simplicity,

having only the few doors and

windows to break the plane surface.

"Cleveland's residences are the

finest, its business architecture the

shabbiest in the United States."

Thus editorialized the Leader in 1869.40

Certainly the majority of the commercial

and mercantile establishments

thrown up in a boom town were purely

utilitarian, but some of them were

architect-designed. During the summer

months of 1855 three wholesale

houses sprang up on Water Street (West

9th). On the corner of Superior

was Payne and Perry's block (not to be

confused with the million dollar

Perry-Payne Building which was erected

near the same site in 1889),

designed by Heard and Porter. A

Cleveland landmark for many years,

SIMEON PORTER 185

the store was a four-story building 48

1/2 feet high, plus a basement, with

a frontage of 138 feet and a depth of

100 feet. The store was described

as being "constructed of face brick

above the first story, which is supported

by iron columns."41

Probably there were structural iron columns on

the interior throughout the five floors.

In the Central High School and

the Perry store then, Heard and Porter

must have been among the first

in the Midwest to use iron columns as

structural supports in place of

masonry walls--this was only six years

after the iron building of James

Bogardus in New York. They built several

such commercial buildings. In

1859 they designed a business block for

I. S. Converse, at the corner of

Merwin and James. The Converse Block was

a three-story building with

a 66 foot frontage on Merwin and a

depth of 100 feet.42

Toward the end of 1855 the first plans

were drawn for the new Cus-

toms House, Federal Court rooms, and

Post Office building. On January

31, 1856, it was announced that the

building would be begun in early

spring and finished by December.43 However,

a series of delays, including

a disagreement concerning its location,

and a long winter in 1857-58,

made this predicted date two years

premature, and the building was

not opened until December 29, 1858.44

The Heard and Porter design for

the Post Office constituted the central

block of the larger building which

was torn down in 1902. Their section,

110 feet long and 60 feet wide,

was in the more classic, or Italian

Renaissance, phase of the round-arched

styles. The Heard and Porter building

was a three-story block with rusti-

cated stone masonry on the first story.

The colonnade and the massive

wings seen in later photographs were

added after 1876. The whole design

had a monumental simplicity undoubtedly

considered more suitable for

public buildings and closely related to

"government style" buildings

everywhere.

Just across the square from the rising

federal building, fire broke out

in the Old Stone Church on March 7,

1857. The flames spread to the

228 foot steeple, and "like a

flaming torch, it swayed and crashed across

Ontario Street."45 The

main church walls, being of stone lined with brick,

still stood, and rebuilding was begun

immediately. The whole was made

as fire-resistant as possible, and the

restored building was dedicated on

January 17, 1858. After the second fire

of 1884, the present interior was

restored by Charles Schweinfurth, and

the new steeple was later declared

unsafe and taken down. A century after

it was built, the Old Stone Church

was the oldest building still standing

in the center of Cleveland, and

although much modified was still

substantially the original design of

Heard and Porter.

The year 1859 marked the completion of

two institutional buildings

which afford an interesting comparison

in their general plan. In the fall

of 1859 the new Lake Erie Female

Seminary (Lake Erie College) in

Painesville was completed. Charles Heard

had been called back to the

city of his famous father-in-law,

Jonathan Goldsmith, to supervise its

construction.46 The Lake Erie College

building, now known as College Hall,

is the largest existing building from

the Heard and Porter partnership.

186 OHIO HISTORY

Measuring 180 feet by 60 feet, the red

brick structure rises four stories

above a basement. A central tower in

turn rises above the main block,

which connects two wings. Connecting the

tower to the wings, and forming

porches in front of the main block, are

two charming wooden arcades

topped by balustrades. College Hall

contained the living rooms for the

instructors and students, the

classrooms, library, gymnasium, dining hall,

and social hall.

In March 1859 it was announced at a

meeting of the Cleveland Orphan

Asylum that a contract had been made

with Messrs. Heard and Porter

"for the speedy completion of the

asylum building."47 The building had

been occupied since 1855. An old

photograph shows a three-story building

with a central tower and block connected

to two side wings. There was

a dome-shaped cupola above. The wings

were connected by a balustraded

and arcaded portico. These similarities

between the two buildings suggest

that this arrangement was considered

appropriate for the institutional

type of building which included the

provision of dormitory space among

its various functions.

But the end of the Heard and Porter

partnership was soon in sight.

In February 1859 the Leader announced

that "an unpretending structure

has recently sprung up in the midst of

that populous portion of the city

[St. Clair below Erie], which must

please the eye of every citizen, and

especially of the Christian."48

The Cottage Chapel was a small house of

worship dedicated to the Sabbath school.

No picture or complete descrip-

tion has been found. But the interesting

fact is that the chapel was planned

by Porter alone, and his builder was G.

H. Kidney. This was the first

indication that Charles Heard and Simeon

Porter were going their separate

ways, and by the next year the firm of

Heard and Porter was no longer

in existence.

Heard and Porter were listed separately

in the city directory of 1859-60.

The reason for the separation is

unknown. Before looking at the final

phase of Simeon Porter's career, it

should be pointed out that Charles

Heard's later career was quite different

from Porter's. Little building

was done during the Civil War. After the

war Heard maintained his

reputation as one of Cleveland's

foremost architects, and he worked in

the latest style, the French Renaissance

revival. The most important of

his buildings were Case Hall, the music

hall and cultural center begun

in 1859 and finally completed in 1867,

the Case Block, a giant five-story

mansarded structure which was leased for

use as the city hall upon its

completion in 1875, and the Euclid

Avenue Opera House (1875). Also in

1875 Heard was chosen as the architect

of the building to represent

Ohio at the 1876 Centennial Exposition

in Philadelphia. The Ohio House

is the only state building from the

exposition still standing on its original

site in Fairmount Park. In the

centennial year, Charles W. Heard died,

on August 29, 1876.

Simeon Porter, on the other hand,

continued to do some work for the

Cleveland public schools, but his most

important buildings after 1860

were done outside of Cleveland. The

Civil War was a time of testing for

SIMEON PORTER 187

the builder as well as for the Union.

Just before the opening of the

conflict, Simeon Porter, perhaps to

dramatize his independence as an

architect, took his first (and only)

advertisement in the city directory of

1861. It simply said: "S. C.

Porter, ARCHITECT, No. 7 Perkins' Building,

Cleveland, Ohio." On the same day

that Fort Sumter was bombarded by

the Confederates, the Leader carried

a small story to the effect that the

carpentry work was finished on the new

West Side High School, designed

by S. C. Porter.49 The building on

State and Clinton Streets was occupied

in the fall, and was described as being

a two-story brick building with a

nine-foot basement of stone. Its

dimensions were50 feet by 96 feet, and

the total height was 51 feet. An old

photograph shows that the West Side

High School was a smaller (but still

"elegant")50 version of the 1856

Central High School, and hence another

reference to the King's College

type. An important difference, however,

was the addition of four battle-

mented corner towers to the Romanesque

theme.

When construction in Cleveland nearly

reached a standstill, fortunately

two or three jobs came to Porter from

outside Cleveland. One of these

was his brother Orrin's house in Hudson.

It is not known for certain

where the complete responsibility lies

for its plan, but in all probability

Orrin and Simeon worked on it together,

taking advantage of Simeon's

experience in Cleveland. The Porter

House seems to be an amalgamation

of elements from both the early Hudson

era and the later Cleveland one.

The house has the square, symmetrical

simplicity of houses of the Hurlbut

type. The bracketed eaves certainly show

the knowledge of the Italianate

style of the fifties. But in spite of

its obviously Civil War character, the

Porter House lives very harmoniously

with its neighbors from the earlier

Western Reserve period. The cornice

return is a reminder of the earlier

classical houses, and the most

recognizable Romanesque element is the

pair of round-arched second-story

windows together with a circular attic

window, translated of course from

masonry into wood.

In December 1861 the president of Mount

Union College near Alliance,

some sixty miles southeast of Cleveland,

procured the services of Simeon

Porter to build its College Hall. On

December 27 the building specifications

and contract were signed by the

architect and the building committee

of the college. The cornerstone laying

ceremony was held on July 4, 1862.

After several delays due to the

unavailability of labor during the war,

College Hall was completed and dedicated

on December 1, 1864.51 By a

remarkable circumstance the manuscript

specifications by Porter are still

in existence, and give unusual insight

into the building practices of the

day.52 The specifications contain

twenty-one paragraphs which give specific

details on all parts of the building. On

the other hand, such general terms

as "suitable," "the most

thorough and approved workman-ship," and "in

the strongest and best manner"

appear over and over again in the specifi-

cations. These are obviously the specifications

of an architect who fully

intended to oversee the construction

himself, and did not need to spell

out what they meant. The basic

construction of College Hall (later named

Chapman Hall) was unvaried from his

standard practice since the earliest

188 OHIO HISTORY

buildings at Hudson, that is, a wooden

frame with outer walls of brick,

and foundations and trim of sandstone.

Although he originally specified the

use of cast-iron columns in the first

and second stories of Chapman Hall,

it was only in a supplement to the

specifications, dated some three weeks

later, that they were also specified in

the interior foundations. This sug-

gests that even after the modern usages

practiced with Heard, Porter

wrote the original specifications from

years of habit in the carpenter-mason

tradition.

What Porter seems to have done with

Chapman Hall was to take the

basic block of the Cleveland Central and

West High Schools, and add

a few touches of Hudson reminiscence on

top. This is not to suggest that

the final result is frivolous. It is

eclectic, it is bold, it perhaps shows a

certain lack of discrimination, but the

result has much dignity. The

main mass of the building is basically

that of the Romanesque high

schools, including the corner towers of

the West Side school. Its overall

length (120 feet by 64 feet) is somewhat

greater. The additions which

recall the classic details of the Hudson

period are the cupolas on either

end of the building. The south cupola is

octagonal and supports a dome

which served as an astronomical

observatory. On the north there is a

square clock tower with shuttered

openings. As a combination of elements

from several periods of Porter's past,

Chapman Hall almost seems to

be a conscious stylistic summary of his

career.

While Porter was supervising the

erection of the Mount Union College

building, Professor Ira O. Chapman (for

whom Chapman Hall was later

named) built a house for himself in

Mount Union village. This was in

1863. The last owner of the house before

it was demolished in the 1950's

reported that it was built "by the

same man who built Chapman Hall."53

A photograph of 1880 shows a brick house

which was almost certainly

not merely contractor-built. It seems

likely that the Chapman House was

one of the last examples of Simeon

Porter's domestic work. The general

form of this house is related to the

Hurlbut and Orrin Porter Italianate

type. It is basically a simple cube with

wide bracketed eaves. Instead of

the crowning observatory, there is

simply a railed platform on the roof.

An unusual note is the third floor

dormer which takes the form of a

curved pediment inserted into the main

cornice. These details show the

continuing freedom with which the early

Victorian architect was able

to rearrange details on a basically

standard plan.

Porter also had another building under

way in Hudson now, the new

brick edifice of the First

Congregational Church. The cornerstone of the

church was laid on July 21, 1863, and

the building dedicated on March 1,

1865.54 The First Congregational Church

is also Romanesque, with a

single, symmetrically placed tower,

buttresses, arcaded corbeling, and

round-arched windows. The entrance door

is an interesting translation

into wood of the slender columns,

foliated capitals, and zigzag molding

of the Old Stone Church. The basic form

of the church, however, probably

gives the best possible indication of

what Heard's Gothic St. Paul's looked

like. Still standing in 1863, that

church must have provided the pattern

SIMEON PORTER 189

for Porter. The Hudson Congregational

Church is essentially a late

example of the early Gothic Revival,

with Romanesque details.

During these war years Porter maintained

his residence in Cleveland.

He had been living at the same address

on Huron Street since first settling

there. In 1865 and 1866 Porter had a new

young draftsman and junior

partner, Charles T. Roesling. During

these two years they did two buildings

which may be compared, the Brownell

Street School in Cleveland, completed

in September 1865,55 and

another building for Mount Union College,

finished in August 1866. Both buildings

were simple rectangular blocks

of three stories with a series of rooms

along a central corridor. The school

had ten windows on a side, with slightly

projecting end blocks grouping

them into a two-six-two division. At

Mount Union the new building was

a boarding hall (later called Miller

Hall). Here there were likewise ten

windows on a side, but they were divided

into vertical ranks by three-story

pilasters and corbeling, like Chapman

Hall and the Western Reserve

buildings.

As Miller Hall was nearing completion,

Porter, as college architect,

was appointed a member of a committee to

prepare a history of Mount

Union College. It contained Porter's own

description of the boarding hall:

Its dimensions are 134 1/2 feet long, by

46 1/2 feet wide, having three

ten feet stories above its basement

story, which contain sixty good

rooms that measure each 12 by 15 feet,

and having proper arrange-

ments in each room for light, heating,

ventilation and furniture, with

roofs of slate, and the interior neatly

and thoroughly finished, and

plastered with hard-finish, and

skillfully constructed throughout, with

reference to health, convenience,

permanence, and architectural taste.56

The interior of Miller Hall was rebuilt

with fire-resistant construction

early in this century, but the outer

walls are those of 1866. Later the

building was marred by a new entrance on

the south side, placed directly

beneath a brick pier and ignoring

completely the structural logic of that

form.

Miller Hall is the last building by

Simeon Porter of which there is a

positive record. Mrs. Farwell states

that "his very active life in overseeing

the buildings he was erecting in various

parts of the country undermined

his health and the last years of his

life [he] was an invalid and slowly

declined until his death."57 By

1870 he no longer listed a business address

in the directory. The next year he died

in Cleveland, on May 6, 1871, and

was buried in the new Lakeview Cemetery.

It was a singular circumstance

that Orrin Porter died in Hudson about

the same hour in the morning

of the same day.

Simeon Porter was a New England pioneer

of the Western Reserve, a

master builder of integrity, and a

fairly typical Victorian architect. He

was not an original genius. His sources

were clear. As an apprentice to

his father and as a master builder, he

learned a solid trade in carpentry

and masonry. As a designer he

undoubtedly relied heavily on the wide-

190 OHIO HISTORY

spread pattern books of the day. But

while using them for decorative

details, he does not seem to have copied

buildings intact from any source.

This freedom was characteristic of the

early Victorian architect. It was

not until the late nineteenth and

twentieth centuries that designers copied

buildings whole. The mid-century

eclectic was an unscholarly one who

assembled details from various sources

with boldness and zest, but always

with freedom and originality. As a

builder, Porter was always conscious

of high standards, to which we can

ascribe the fact that so many of his

buildings are standing and in use today.

But once he set upon the path

of designing, he does not seem to have

returned to the actual building

trades himself. He did indeed

superintend construction, seeing that ma-

terials were sound and specifications

followed, but this was part of the

job of the architect.

Simeon Porter could probably be said to

have worked chiefly in three

styles. His early post-colonial work

before 1835 was of course the heritage

of his father, simply continued until he

became aware of any other

possibility. His Greek Revival work in

Hudson is typical of the provincial

simplification with which that style was

treated all over the Midwest.

His arrival in Cleveland just as the

Romanesque style was taking hold

seems to have set his preference for the

rest of his building career.

The work of Heard and Porter was among

the most advanced in the

Midwest. Their use of the Romanesque, of

cast-iron columns as soon as

they were available, and of folding

partitions, was among the earliest.

Perhaps more important, Heard and Porter

helped to change the face

of Cleveland. The dozen-odd buildings

that are known must be assumed

to be only a portion of their actual

work. If one considers as a sample

one or two masterpieces of Romanesque

church architecture, a half dozen

schools and residences, several important

public buildings, and commer-

cial stores in which the new structural

system was eagerly tried, this is

an impressive record, and the other jobs

coming to such an important firm

can be readily imagined. The work that

Porter did alone in the last decade

of his life completed his development as

a Victorian architect, and might

be seen, in one sense, as a

recapitulation of the various stylistic elements

of his earlier career.

Simeon Porter developed from a master

craftsman into a Victorian

architect as the Western Reserve was

developing from a pioneer, agrarian

society into a mercantile, industrial

one. It has frequently been observed

that the evolution of architecture not

only parallels but even embodies

the growth and development of a region,

and for this reason alone the

career of Simeon Porter is an invaluable

chapter in the story of the

Western Reserve of Ohio.

THE AUTHOR: Eric Johannesen is the

chairman of the art department at Mount

Union College.